Highlights

What GAO Found

Why GAO Did This Study

What GAO Recommends

Recommendations

Recommendations for Executive Action

| Number | Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Justice | The Director of BOP should update its program evaluation plan to set a new timeline for conducting an evaluation of FPI. (Recommendation 1) |

| 2 | Department of Justice | In order to help promote a meaningful program assessment, the Director of BOP should develop a goal for FPI related to recidivism reduction and measure progress toward meeting that goal. (Recommendation 2) |

Introduction

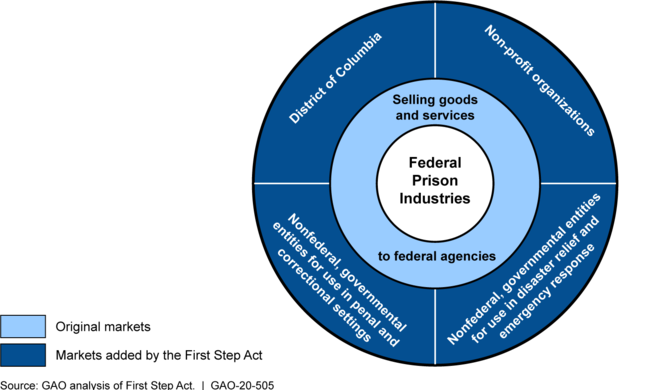

- public entities, such as states,[5] for use in penal or correctional institutions;

- public entities for use in disaster relief or emergency response;

- the government of the District of Columbia; and

- certain tax-exempt (or “nonprofit”) organizations.[6]

- The potential size and scope of the additional markets made available to FPI under the First Step Act;

- The similarities and differences in selected requirements and business practices of FPI and private sector sellers of products and services;

- The extent to which FPI customers are satisfied with the quality, price, and timely delivery of its products and services; and

- The extent to which BOP has evaluated the effectiveness of FPI and other vocational programs in reducing recidivism.

Background

Overview of Federal Prison Industries

Note: For fiscal year 2017 and beyond, the number of inmates employed reflects the total number of inmates who worked in FPI at any point and for any length over the course of the fiscal year. Prior to fiscal year 2017, the numbers reflected only those inmates employed by FPI at the end of the fiscal year.

Laws, Regulations, and Practices Governing FPI Products and Services

- FPI sells inmate-furnished services to the private sector, including the staffing of call centers and computer-aided design services. FPI sold approximately $8.7 million in commercial market services in fiscal year 2019.

- FPI sells goods to private-sector firms if FPI repatriates the production from overseas. Specifically, FPI may manufacture goods currently made, or that otherwise would be made, outside of the United States for private sector firms. According to officials, FPI performs this work under a contract whereby FPI produces goods under the label or brand of a private firm. FPI’s board of directors must approve any product offered under this authority. FPI has approved 32 of these arrangements as of fiscal year 2019, including for the production of surgical appliances. FPI sold approximately $2.5 million in goods to the private sector under this arrangement in fiscal year 2019.

- FPI participates in the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP). Under this program, federal prisoners work at the direction of private sector firms to produce items if they are paid prevailing wages for their work, among other requirements. Overall, FPI generated $2.8 million in sales under the program in fiscal year 2019.

- FPI acts as a subcontractor to private firms that provide goods or services to the federal government as a prime contractor. FPI sold approximately $12 million from such activities in 2019. For example, a company that manufacturers uniforms for DHS subcontracted some of this work to FPI to manufacture a portion of the order.

- FPI operates two farms in California and Oklahoma BOP facilities, which produce commodities such as cheese. FPI sold over $6 million worth of agricultural products in fiscal year 2019, primarily to BOP.

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

- Estimating Size of New Markets Is Challenging and FPI Is Taking Steps to Help Address Potential Limits to Expansion

- FPI and Private Companies Face Different Legal Frameworks, Security Environments, and Costs

- Feedback Mechanisms Suggest Customers Are Generally Satisfied with FPI’s Performance

- BOP Lacks Program Evaluation Timeline and a Recidivism Goal for FPI

Estimating Size of New Markets Is Challenging and FPI Is Taking Steps to Help Address Potential Limits to Expansion

Data on the D.C. Government Market Are Available, but Data to Estimate the Size of the Other New Markets Are Limited

Various Challenges May Affect FPI’s Ability to Expand into New Markets and FPI Has Efforts Underway to Help Address Them

FPI and Private Companies Face Different Legal Frameworks, Security Environments, and Costs

FPI and the Private Sector Operate Within Different Legal Frameworks

FPI Operates in a Unique Security Environment

FPI and Private Sector Have Different Cost Challenges

Feedback Mechanisms Suggest Customers Are Generally Satisfied with FPI’s Performance

Mechanisms Exist to Obtain Customer Feedback

Available Data Indicate Customers Are Generally Satisfied with FPI Performance in Quality and Delivery, but Satisfaction with Cost Is Largely Unknown

Note: The information outlined in this table is based on our review of all 231 performance reports available as of August 21, 2019. The percentages shown represent the number of times, out of 231 reports, Federal Prison Industries received a certain rating in the chosen categories. Rows may not equal 100 percent due to rounding.

BOP Lacks Program Evaluation Timeline and a Recidivism Goal for FPI

BOP’s Program Evaluation Plan Is Outdated and Lacks a Timeline for Conducting an FPI Evaluation

BOP Has Not Developed a Recidivism Goal for FPI

Studies Show FPI and Other Vocational Programs Generally Reduce Recidivism

Conclusions

Agency Comments

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Congressional Addressees

The Honorable Lindsey Graham

Chairman

The Honorable Dianne Feinstein

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Jerrold Nadler

Chairman

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

Appendixes

IN THIS SECTION

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope and Methodology

Bookmark:Appendix II: Market Research for Federal Prison Industries (FPI) Products and Services

Bookmark:Department of Defense

Bureau of Prisons

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix III: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

Bookmark:GAO Contact

Staff Acknowledgments

References

Tables

- Table 1: Federal Prison Industries (FPI) Sales and Number of Inmates Employed, Fiscal Years 2013-2019

- Table 2: Federal Prison Industries (FPI) New Markets Authorized under the First Step Act

- Table 3: Comparison of Federal Prison Industries (FPI) and Private Sector Costs

- Table 4: Federal Prison Industries’ Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System Ratings

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| BOP | Bureau of Prisons |

| CBP | U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CPARS | Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System |

| D.C. | District of Columbia |

| DHS | Department of Homeland Security |

| DLA | Defense Logistics Agency |

| DOD | Department of Defense |

| DOJ | Department of Justice |

| FAR | Federal Acquisition Regulation |

| FEMA | Federal Emergency Management Agency |

| FPI | Federal Prison Industries |

| GPRAMA | Government Performance and Results Modernization Act of 2010 |

| IRS | Internal Revenue Service |

| OCP | District of Columbia (D.C.) Office of Contracting and Procurement (OCP) |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| PATTERN | Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risks and Needs |

| PIECP | Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program |

| TSA | Transportation Security Administration |

End Notes

Contacts

Gretta L. Goodwin

Director, Homeland Security and Justice, goodwing@gao.gov, (202) 512-8777William T. Woods

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions, woodsw@gao.gov, (202) 512-4841Congressional Relations

U.S. Government Accountability Office

441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

U.S. Government Accountability Office

441 G Street NW, Room 7149, Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

U.S. Government Accountability Office

441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington, DC 20548

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

Order by Phone

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7470

Connect with GAO

GAO’s Mission

Copyright

(103393)