Highlights

What GAO Found

The data that banks report to regulators have characteristics that make determining how community banks' small business lending changed since 2010 difficult. However, GAO's analysis found that the regulatory environment likely had a generally modest effect on various aspects of community banks and their small business lending.

Regulators data on small business lending. The data community banks report to regulators do not accurately capture lending to small businesses because the data exclude some loans to small businesses. Specifically, the definition of small business loans used for banks' reporting excludes loans greater than $1 million and has not been adjusted for inflation since 1992. In addition, the data capture loans by their size rather than the size of the borrowing entity, and therefore could include small loans to large businesses. These limitations hamper regulators' and policymakers' ability to assess actual changes in banks' small business lending, including any effect of regulation.

Amount of lending . GAO's analysis used alternative measures of small business lending and found that community banks' lending likely declined following the financial crisis but then increased from 2013 through 2017. After adjusting regulators' data to account for community bank mergers and other exits, remaining banks' small business lending increased by 5 percent from 2013 through 2017, and total business lending by all community banks grew to exceed 2010 levels. GAO's econometric models also found that community banks' small business lending since 2010 can be explained largely by macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics, and that the potential effect of regulatory changes was likely modest.

Lending processes. Based on our nationally representative survey of community banks, GAO estimates that most community banks made changes to their small business lending processes since 2010. Most banks cited the regulatory environment as the primary reason for these changes, which included seeking more documentation from borrowers and taking longer to make loans. Representatives of entities that assist small businesses were mixed on whether these changes affected small businesses’ ability to obtain loans.

Number of community banks. From 2010 through 2017, the population of community banks decreased by about 24 percent, largely due to mergers among community banks and a decline in the rate of new bank formations. However, GAO's econometric model found that macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics explained the majority of these trends, but changes in the regulatory environment and other factors may have also played a small role.

Community bank financial performance. Although many institutions reported increasing or reallocating staff and other resources to assist with regulatory compliance since 2010, GAO's analysis suggests that the effect of these changes on profitability and customer service were likely modest.

As regulatory changes do not occur in isolation and their cumulative effect cannot be easily quantified, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Why GAO Did This Study

Community banks—generally small and locally focused institutions—are important sources of credit to small businesses. Since the 2007–2009 financial crisis, regulators have made significant changes to the regulatory environment. While intended to increase institution soundness and better protect consumers, regulations and supervision can also have effects that Congress or regulators may not have intended. In particular, questions arose as to whether regulatory changes reduced community banks’ ability to make small business loans.

GAO was asked to assess the effect of regulatory changes since 2010 on community banks and small business lending. GAO examined the data regulators use to measure small business lending, as well as the extent of any regulatory effects on the amount of community banks’ small business lending and their lending processes, changes in bank populations, and financial performance. GAO analyzed community bank lending and financial data from 2001 through 2017, built econometric models using these and other data, and surveyed a nationally representative sample of over 450 community banks. GAO also interviewed staff from community banks (selected to ensure a range of sizes and geographic regions), small business advisers, banking and consumer advocacy groups, and financial regulators.

What GAO Recommends

GAO makes three recommendations to banking regulators to reevaluate and modify, as needed, the data they collect to measure small business lending. They agreed to the recommendations.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of three recommendations, one each to the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC.

| Number | Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Federal Reserve System: Board of Governors | The Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System should collaborate with FDIC and OCC to reevaluate, and modify as needed, the requirements for the data banks report in the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Incomes to better reflect lending to small businesses. (Recommendation 1) |

| 2 | Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation | The Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation should collaborate with the Federal Reserve and OCC to reevaluate, and modify as needed, the requirements for the data banks report in the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Incomes to better reflect lending to small businesses. (Recommendation 2) |

| 3 | Department of the Treasury: Office of the Comptroller of the Currency | The Comptroller of the Currency should collaborate with the Federal Reserve and FDIC to reevaluate, and modify as needed, the requirements for the data banks report in the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Incomes to better reflect lending to small businesses. (Recommendation 3) |

Introduction

August 6, 2018

Dear Mr. Chairman:

Financial regulators have implemented many new regulations in the aftermath of the 2007–2009 financial crisis. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) of 2010 included numerous reforms to strengthen practices and oversight of financial institutions.[1] Although community banks and credit unions were exempt from several provisions of this act, they have had to respond to additional regulatory requirements as a result of it and other regulatory efforts. These institutions have historically played an important role in serving their local customers, including providing credit to small businesses. Because small businesses are important to the economic well-being of the United States, questions have been raised about the effect of regulations on their ability to access credit from smaller depository institutions. According to Census Bureau data, businesses with less than 500 employees accounted for about 48 percent of U.S. total employment in 2015. A 2017 Small Business Administration (SBA) report indicated that small businesses annually contribute almost 40 percent of the U.S. private nonfarm output, but noted that these businesses typically faced challenges accessing credit, a key element of small business survival and growth.[2]

You asked us to examine the effects of changes in the regulatory environment on community banks and credit unions and their ability to meet the needs of small businesses. Changes in the regulatory environment encompass changes to specific laws and regulations as well as changes in how existing requirements are implemented and enforced. This report examines, for the period 2010 through 2017, the effect of the regulatory environment on community banks and credit unions, including (1) the data regulators use to measure the volume of small business lending and how and why small business lending volumes changed, (2) how and why small business lending processes changed among these institutions, and (3) how and why the number of institutions and their financial performance changed, as well as (4) actions regulators took to identify and mitigate the effects of changes in the regulatory environment on these institutions and their small business customers.[3] In response to your request, we also provided you with a report in February 2018 that addressed which regulations institutions viewed as most burdensome and what actions financial regulators had been taking to reduce this burden.[4]

To identify how and why community banks' and credit unions' small business lending, number of institutions, and financial performance changed, we took the following steps:

- Analyzing available data. We analyzed bank and credit union regulatory data on the level of small business lending; mergers, failures, and new institution formation; and the market shares, resource costs, profitability, and operational efficiency of these institutions from 2001 through 2017.[5] Because of limitations with regulators' data, we also used two alternative measures—(1) business loans of $1 million or less made by survivor community banks (that is, community banks that did not become or merge with a large bank, voluntarily exit the market, or fail during the period we examined) and (2) community banks' total business loans—as proxy measures of small business lending. We believe that these measures, identified through our internal analyses and our conversations with bank regulators, were suitable as alternative measures of small business lending.

- Econometric modeling. We developed econometric models to better understand how many of the changes in community bank trends (such as small business lending, mergers, and new bank formations) could potentially be attributable to changes in the regulatory environment since 2010. Because measuring the cumulative effect of changes in the regulatory environment is difficult, we used a two-stage approach that did not involve estimating regulatory effects directly. First, we developed models that used data on macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics (factors represented by variables we could measure) from 2003 through 2009 to forecast community bank trends from 2010 through 2016. Second, by comparing the observed trends that actually occurred during the period to the trends forecasted by the models, we drew conclusions about the influence of "other factors," which could include the influence of changes in the regulatory environment since 2010, changes in demand for small business loans, technological advancements, and incentives for banks to achieve economies of scale, among other things. However, because we cannot distinguish the components of the "other factors" category from one another, we cannot know with certainty the effect of changes in the regulatory environment on community bank trends.

- Surveying community banks and credit unions. We surveyed generalizable samples of more than 450 community banks and 450 credit unions (selected to represent urban and rural areas, geographic regions, and a range of size categories) to identify why they may have made changes to their operations from January 2010 through August 2017.[6]

- Interviewing key stakeholders. We interviewed 18 banks and credit unions, selected to represent a range of asset sizes and geographic regions; consumer groups and financial services advocacy groups chosen because of their familiarity with community banks and credit unions and changes in the regulatory environment; and entities that advocate on business issues or that provide advice to businesses on lending issues.

To determine how regulators identified the effects of regulatory changes, we interviewed staff from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve), the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (BCFP), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).[7] We also analyzed studies by these entities and other researchers and academics on trends in banking and lending. In addition, we interviewed staff from SBA. Appendix I provides more detail on our scope and methodology, and appendix II provides the structure and specifications of the econometric modeling and the data we used as inputs.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2016 to August 2018 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Community banks are generally smaller banks that provide relationship banking services to local communities and have management and board members who reside in the communities they serve. Regulators and others have observed that community banks tend to differ from larger banks in their relationships with customers. Large banks are more likely to engage in transactional banking, which focuses on highly standardized products that require little human input and are underwritten using statistical information. In contrast, community banks are more likely to engage in what is known as relationship banking, in which banks consider not only data and statistics but also nonquantifiable information acquired primarily by working with the banking customer over time. Using this banking model, community banks may be able to extend credit to customers, such as small business owners, who might not be considered for a loan from a larger bank that engages in transactional banking.

Small business lending is a significant activity by community banks. As of June 2017, community banks had over $292 billion outstanding in business loans with original principal balances under $1 million (which is how small business loans are defined in regulatory reports), which represented about 19 percent of these institutions’ total lending. In that same month, large banks held about $390 billion outstanding in business loans with original principal balances under $1 million, representing 5 percent of their total lending.

Credit unions are nonprofit, member-owned institutions that take deposits and make loans. Unlike banks, credit unions are subject to limits on their membership because members must share a “common bond”—for example, working for the same employer or living in the same community. In addition to providing consumer products to their members, credit unions are also allowed to make loans for business activities subject to certain restrictions. These "member business loans" are defined as a loan, line of credit, or letter of credit that a credit union extends to a borrower for a commercial, industrial, agricultural, or professional purpose.[8]

Regulators Overseeing Community Banks and Credit Unions

The regulator responsible for overseeing a community bank or credit union varies depending on how the institution has been chartered and whether it is federally insured (see table 1). Federal depository institution regulators are responsible for ensuring the safety and soundness of the institutions they oversee, protecting federal deposit insurance funds, promoting stability in financial markets, and enforcing compliance with applicable consumer protection laws. All depository institutions that are covered by federal deposit insurance have a federal prudential regulator that oversees the safety and soundness of the institution and may issue regulations and take enforcement actions against institutions within its jurisdiction.

Other federal agencies also impose regulatory requirements on banks and credit unions. These include rules issued by BCFP, which was created by the Dodd-Frank Act and implements and, where applicable, enforces federal consumer financial laws.[9] BCFP has supervisory and enforcement authority for federal consumer financial laws for insured depository institutions with more than $10 billion in assets and their affiliates. The federal depository institution regulators—FDIC, the Federal Reserve, OCC, and NCUA—examine how federally insured institutions with $10 billion or less in assets comply with consumer protection requirements. Although community banks and credit unions with less than $10 billion in assets would not typically be subject to examinations by BCFP, they are generally required to comply with the rules related to consumer protection issued by this agency.

In addition, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issues regulations that financial institutions, including banks and credit unions, must follow. FinCEN is a component of the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, and it supports government agencies by collecting, analyzing, and disseminating financial intelligence information to combat money laundering. It is responsible for administering the Bank Secrecy Act, which, with its implementing regulations, generally requires banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions, among others, to collect and retain various records of customer transactions, verify customers’ identities in certain situations, maintain anti-money laundering programs, and report suspicious and large cash transactions.[10] FinCEN relies on financial regulators and other entities to conduct examinations of U.S. financial institutions across a variety of financial sectors to determine compliance with these regulations.

Impact of the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis

Assessing the effect of changes in the regulatory environment in the period following the 2007–2009 crisis is complicated by the severity of the crisis’s economic impact on the United States. In a January 2013 report, we reviewed academic and other sources and found that the 2007–2009 financial crisis, like past financial crises, was associated with a steep decline in output and the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s.[11] The U.S. economy entered a recession in December 2007 that lasted until June 2009, with U.S. real gross domestic product falling by nearly 5 percent and not regaining its pre-recession level until the third quarter of 2011. Some studies noted that the impacts of the crisis could persist beyond 2018 or be permanent.

The 2007–2009 crisis was also associated with large declines in employment, household wealth, and other economic indicators that could have affected the rate of new business formations and demand for small business loans. The monthly unemployment rate peaked at around 10 percent in October 2009 and remained above 8 percent for over 3 years, the longest such stretch since the Great Depression. Between 2005 and 2011, households collectively lost about $9.1 trillion (in constant 2011 dollars) in national home equity in part because of the decline in home prices. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances found that median household net worth fell by $49,100 per family, nearly 39 percent, from 2007 through 2010. Such dramatic declines in net worth, combined with an uncertain economic outlook and reduced job security, can cause consumers to reduce spending, and lower the financial health of businesses and their willingness to seek credit. Reduced consumption, all else being equal, further reduces aggregate demand and real gross domestic product. However, our 2013 report noted that analyzing the peak-to-trough changes in certain measures, such as home prices, can overstate the impacts associated with the crisis, as valuations before the crisis may have been inflated and unsustainable.[12]

Changes to Financial Regulations since 2010

In response to the 2007–2009 financial crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, which became law on July 21, 2010. The act included numerous reforms to strengthen oversight of financial services firms, including consolidating consumer protection responsibilities within BCFP, which the act created. The Dodd-Frank Act also directed or granted authority to federal financial regulatory agencies to issue hundreds of regulations to implement the act’s reforms. Many of the act's provisions target the largest and most complex financial institutions, and regulators have noted that much of the act is not meant to apply to community banks or credit unions.

Although the Dodd-Frank Act exempts small institutions, such as community banks and credit unions, from several of its provisions and authorizes federal regulators to provide small institutions with relief from certain regulations, it also contains provisions that impose additional restrictions and compliance costs on these institutions. As we reported in 2012, federal regulators, state regulatory associations, and industry associations collectively identified provisions within 7 of the act’s 16 titles that they expected to affect community banks and credit unions.[13]

In addition to regulations resulting from the Dodd-Frank Act, other regulations have created potential burdens for community banks. For example, depository institution regulators also revised the capital requirements applicable to banking organizations, including community banks. These requirements were to implement the Basel III framework, a comprehensive set of reforms to strengthen global capital and liquidity standards issued by an international body consisting of representatives of various countries’ central banks and regulators. These new requirements significantly changed the risk-based capital standards for banks and bank holding companies and introduced new leverage and liquidity standards. As we reported in November 2014, officials interviewed from community banks did not anticipate any difficulties in meeting the new U.S. capital requirements but expected to incur additional compliance costs.[14]

Although a number of provisions may ultimately affect lending by smaller institutions, we noted in our 2012 report that officials from federal agencies, state regulatory associations, and industry associations identified only one provision in the Dodd-Frank Act that was directly related to small business lending.[15] This provision was section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which amended the Equal Credit Opportunity Act to require financial institutions to compile, maintain, and report information concerning credit applications made by women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses in accordance with regulations issued by BCFP. The purpose of the provision was to facilitate the enforcement of fair lending laws and enable communities, governmental entities, and creditors to identify the business and community development needs and opportunities of women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses. In May 2017, BCFP issued a request for information to seek public comments to inform its efforts to implement this additional reporting.[16]

However, some Dodd-Frank Act provisions have also likely resulted in reduced costs for community banks. For example, revisions to how deposit insurance premiums are calculated reduced premiums by 33 percent for banks with less than $10 billion in assets between the first and second quarters of 2011. Another change reduced the audit-related costs that some banks were incurring in complying with provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

Potential Benefits of Financial Regulation

Financial regulations can also provide significant benefits. For example, a primary objective of banking regulations is to promote the safety and soundness of banks and the banking system.[17] Effective regulation and supervision can safeguard against future financial crises and provide an important source of confidence to the market about the general health and resiliency of the banking sector. Past banking-related crises have demonstrated the need for federal banking regulators to respond proactively to problems developing in the banking system. In February 2018, we reported that staff of federal regulators and consumer groups noted various benefits of regulations related to mortgage activities and requirements to report suspicious banking activities.[18] For example, they said that collecting data on a mortgage applicant’s demographic characteristics (such as an applicant's race, ethnicity, and sex) has helped address discriminatory lending practices and are essential for the enforcement of fair lending laws and regulations.[19] Similarly, regulators have reported that requirements for institutions to report large cash deposits help ensure that the U.S. financial sector is not used to aid illicit activity, including the sale of illegal narcotics, terrorism, and human trafficking.[20]

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

- Small Business Lending Data Have Substantial Limitations, but the Effect of the Regulatory Environment on Lending Volumes Appears Modest

- Community Banks Reported That the Regulatory Environment Was a Primary Reason for Changing Lending Processes

- Factors Other Than Regulatory Environment Explain Most Changes in the Number and Financial Performance of Community Banks

- Regulators Have Taken Steps to Analyze and Mitigate the Effects of Regulatory Changes on Small Business Lending

Small Business Lending Data Have Substantial Limitations, but the Effect of the Regulatory Environment on Lending Volumes Appears Modest

Limitations in the data banks report to bank regulators make it difficult to determine how small business lending by community banks changed after 2010. However, alternative proxies that partially address these limitations suggest that such lending has increased since the financial crisis. In addition, our econometric analysis indicates that changes in the regulatory environment likely had a modest effect on community banks' small business lending volumes from 2010 through 2016.[21] Further, small business lending by credit unions, which accounts for a small share of total small business lending, increased considerably from 2010 through 2017.[22]

Measuring Small Business Lending Using Call Report Data Poses Challenges

The data banks report to bank regulators on their lending do not provide a fully accurate measure of loans to small businesses. Specifically, in Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports)—financial reports that banks provide to regulators—banks are required to report any loans they make to businesses with original principal balances of $1 million or less.[23] These data, which bank regulators use as a proxy to measure small business lending, appear to show that community bank lending to small businesses declined after the financial crisis. Specifically, community banks' total business loans with original principal balances of $1 million or less decreased by 16 percent from 2010 through 2017, from $347 billion in outstanding loans to $292 billion.

However, using business loans with original principal balances of $1 million or less is not an accurate measure of small business lending for two reasons:[24]

- The measure is based on loan size rather than size of the business obtaining the loan. As a result, a loan for more than $1 million obtained by a small company is not reported as a small business loan. In November 2017, FDIC presented preliminary results of a survey indicating that banks with less than $1 billion in total assets (a population that includes most community banks) made about $93 million in commercial and industrial loans—one type of business loan included in the Call Report data on small business lending—as of December 31, 2015, that were not counted under this measure because the loans to small businesses exceeded the $1 million threshold.[25] In addition, banks would also report as part of this measure loans obtained by a large company for less than $1 million, which further distorts its use as a measure of lending to small businesses.

- Inflation distorts the accuracy of the measure over time. The loan thresholds for Call Report data on small business lending—$1 million for businesses and $500,000 for loans to farms—are not adjusted for inflation and have not changed since 1992. As a result, the number of loans that fall under these thresholds decreases over time due to inflation alone, which averaged about 2 percent annually from 1992 through 2017.[26] Therefore, the data this measure captures have likely significantly underestimated banks' lending to small businesses since 1992. As shown in figure 1, if the measure's $1 million threshold had been indexed to inflation, banks would have reported loans with original principal balances under around $1.6 million as small business loans in 2017. A $1 million loan in 2017 was equivalent to a loan of about $625,000 in 1992 terms.

Figure 1: Effect of Inflation on Bank Regulators' $1 Million Threshold for Small Business Lending, 1992–2017

Another factor affecting the use of these data for assessing community banks' lending to small businesses is that the population of these banks changes over time. Thus, the amount of lending captured by the data can decline as a result of banks exiting the population, rather than as a result of banks decreasing their lending. A bank exits the population of community banks when the bank:

- no longer meets the definition of a community bank (for example, by merging or growing to become a large bank),

- voluntarily exits (for example, by becoming a credit union), or

- fails without being acquired by another community bank.[27]

As a result, these exits can overstate the extent to which small business lending as captured in the Call Report data appear to decrease over time.

Alternative Measures Addressing Some Small Business Lending Data Limitations Suggest That Lending May Have Increased in Recent Years

To address some of the limitations of the Call Report data on small business lending, we examined two alternative measures of community bank small business lending. These alternative measures suggest that community banks' small business lending likely increased from 2013 through 2017 after decreasing from 2010 through 2012 following the financial crisis. Our first alternative measure adjusted the Call Report data to account for exits by banks leaving the population of community banks. To account for the effect of these departures, we identified as "survivor" community banks those community banks that existed or formed since 2001 and remained in existence through 2017, and we excluded banks that exited the population of community banks at any time from 2001 through 2017.[28] Analyzing the lending by these survivor community banks allowed us to capture changes in bank lending levels rather than changes resulting from banks leaving the population of community banks.

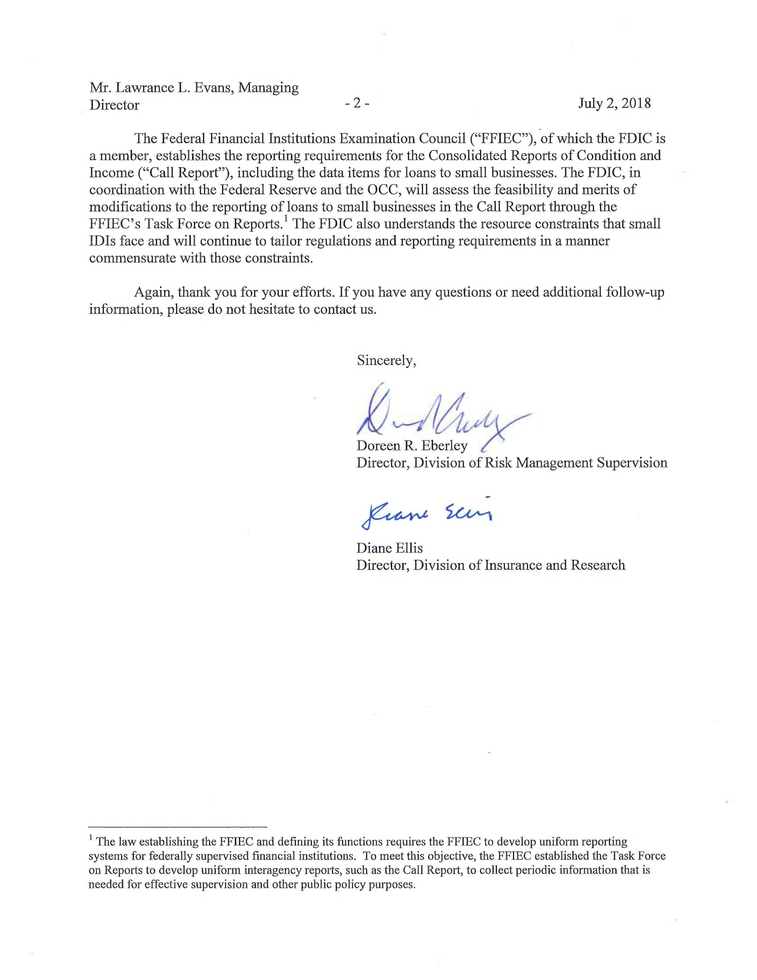

When we adjusted the Call Report data on small business lending to account for exits from the community bank population, we found that survivor community banks' volume of loans outstanding decreased by 6 percent from 2010 through 2012, but increased by 5 percent from 2013 through 2017 (see fig. 2).[29] This analysis suggests that exits explain some portion of the 16 percent decline shown by the Call Report data on small business lending from 2010 through 2017.

Figure 2: Volume of Community Banks' Outstanding Business Loans with Original Principal Balances of $1 Million or Less, 2001–2017, by Bank Population

Adjusting the Call Report data for exits from the community bank population does not address all the limitations of these data discussed above. Specifically, examining Call Report data for survivor community banks also does not capture small business loans larger than $1 million, and they may include loans under $1 million made to large businesses. In addition, this analysis does not overcome the limitation of the $1 million small business loan threshold not being adjusted for inflation. Finally, restricting the population of banks for analysis may also introduce some bias by excluding information on changes in small business lending by the institutions that exited.

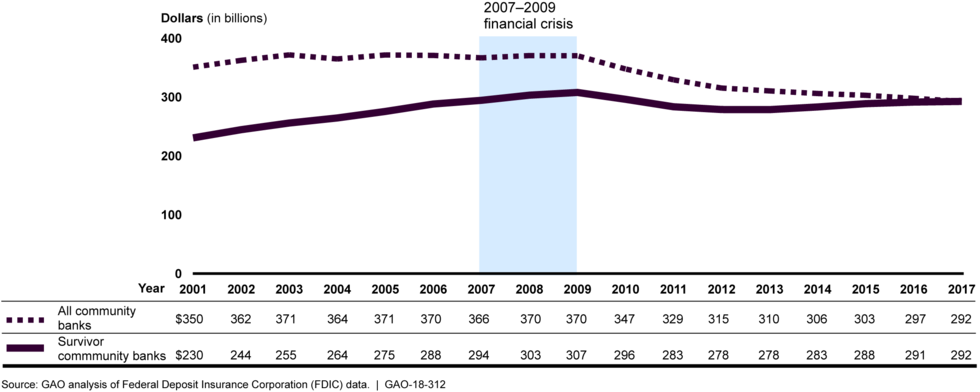

A second alternative measure we used to try to overcome the limitations of the Call Report data on small business lending was to examine community banks' total loans to businesses, which banks also report to regulators and includes business loans of all sizes. Because data on total business lending includes loans of any size, inflation does not cause a growing proportion of small business loans to be excluded from the data over time. FDIC officials said they typically use the Call Report total business lending measure as a proxy measure for community banks' small business lending activity. FDIC officials noted that the preliminary results of their recent small business lending survey confirm that many community bank business loans are small business loans. According to this survey, 86 percent of banks with assets less than $250 million and 77 percent of banks with assets between $250 million and $1 billion said that "largely all" of their commercial and industrial lending is to small businesses.[30] However, measuring community banks' small business lending using data on these institutions' total business lending overestimates these institutions' small business lending by including loans to large businesses.

We found that community banks' total business lending increased from 2010 through 2017 (see fig. 3).[31] Specifically, we found that community banks' total business lending dipped slightly after the financial crisis, but exceeded precrisis levels by 2017 (similar to lending by survivor community banks, which also began to increase in the years following the financial crisis). Without accounting for exits from the community bank population, community banks' total business loans outstanding increased from about $689 billion 2010 to about $765 billion in 2017, or approximately 11 percent.[32] When we accounted for exits from the community bank population, the increase was even larger. Specifically, survivor community banks’ total business lending increased by about 36 percent, from $563 billion in outstanding loans in 2010 to $765 billion in 2017. These results again suggest that some portion of the decline shown by the Call Report data on small business lending for the full population of community banks from 2010 through 2017 is likely due to the limitations of that measure rather than actual changes in banks' lending activities.

Figure 3: Volume of Community Banks' Outstanding Business Loans with Original Principal Balances of $1 Million or Less and Total Business Loans, 2001–2017

Regulators Have Not Taken Steps to Address the Limitations in the Call Report Measure of Small Business Lending

As previously discussed, the data that banks report to regulators do not reflect the full range of their lending to small businesses because they are based on loan rather than firm size and have not been adjusted for inflation. The use of Call Report data on business loans with original principal balances of $1 million or less as a measure of small business lending was established as a result of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 (FDIC Improvement Act). The act requires FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC to collect information from insured depository institutions that is sufficient to assess the availability of credit to small businesses and small farms.[33]

FDIC officials said they recognize that the data they use for community banks' small business lending have some flaws, but they define small business loans as they do to minimize the reporting burden for banks. When establishing the reporting requirements in 1992, bank regulators considered categorizing loans as small business loans based on the total sales volume of borrowing businesses and farms. However, they did not adopt that definition after receiving a large number of comments that it would be burdensome to implement.[34] FDIC officials also said that banks would likely find continually adjusting the loan threshold in their reporting systems for inflation to be difficult and potentially burdensome. In addition, Federal Reserve officials told us that bankers and other stakeholders often express concerns about the burden of collecting data on small business lending, noting that community banks often use basic systems and sometimes rely on paper record keeping.[35]

Officials from FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC told us their agencies have not reevaluated the reporting requirements since they were established in 1992, except for mandated reviews in which bank regulators must determine whether each Call Report item should remain in place.[36] FDIC and OCC officials also said they were not aware of their agencies making or considering any formal proposals to alter the requirements, but officials from the Federal Reserve said they have proposed changing the definition so that it is based on the size of the borrowing firm. When bank regulators established the existing requirements for reporting on small business loans, they cited a 1989 survey that found a correlation between business size and loan size, but bank regulators told us they have not reexamined this correlation because they have no reason to believe it does not still hold true.

Some evidence suggests that basing the reporting requirements for small business lending on firm size and adjusting them for inflation may not be as burdensome as bank regulators and others once thought. For example, a 2016 survey found that community banks already use a borrowing firm's total revenue as the top factor in defining small business loans.[37] In addition, technological changes since 1992 may facilitate banks' ability to collect these data without creating additional undue burden on banks.

Because the reporting requirements for small business loans likely exclude a significant portion of loans to small businesses, bank regulators are hindered in their ability to assess the availability of credit to small businesses and small farms, as required by the FDIC Improvement Act. Moreover, the Federal Reserve recently began a new survey on small business lending because, officials told us, existing data are not sufficient for understanding and addressing related policy issues, which further underscores the limitations of available data.[38] Federal internal control standards also state that entities should obtain relevant data from reliable internal and external sources to achieve their objectives.[39] Without reporting requirements that better reflect banks' lending to small businesses, bank regulators and policymakers may be limited in their ability to assess the effects of regulation and other factors on the availability of credit to these firms.

Macroeconomic, Local Market, and Bank Characteristics Largely Explain Community Bank Small Business Lending since 2010, but the Regulatory Environment Also May Have Played a Small Role

Our econometric analysis suggests that the effect of changes in the regulatory environment on small business lending, if any, was relatively small from 2010 through 2016. To examine influences on community banks' small business lending from 2010 through 2016, we developed econometric models of each of our two alternative measures of small business lending—survivor community banks' business loans of $1 million or less and all community banks' total business lending. Because measuring the cumulative effect of changes in the regulatory environment is difficult, each model attempts to determine the extent to which macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics—factors we can measure—explained community banks' small business lending compared to all other factors:[40]

- Macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics. Macroeconomic conditions include growth in gross state product and interest rates. Local market demographics and competition include unemployment rates, population density and growth, changes in house prices, and the extent of market competition among all banks and credit unions. Bank characteristics include bank size, whether a bank is geographically diversified, the extent of performing and nonperforming loans, and the level of equity capital.

- Other factors. This category includes all factors that may have affected small business lending volumes other than those listed above. We did not include data for these factors directly in our model. These factors may include changes in the regulatory environment after 2010, changes in demand for small business loans, technological changes, and lending by nonbank competitors, among others.[41]

To examine the cumulative effect of the regulatory environment on small business lending, we estimated each model using data on macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics from 2003 through 2009. We then used these results to forecast the small business lending trends that would have occurred from 2010 through 2016 given the macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics that prevailed during this later period.[42] We then compared the lending levels our model forecasted to those that actually occurred. To the extent these differed, a greater difference between actual and forecasted lending indicates a greater influence by the set of factors that includes the regulatory environment.[43]

Our models found that macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics explained the majority of community banks’ outstanding small business lending from 2010 through 2016, leaving a relatively small portion of lending volumes that could potentially be explained by changes in the regulatory environment.[44] Because macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics forecasted small business lending trends that closely resembled the actual trends, we were able to conclude that the influence of other factors, such as changes in the regulatory environment after 2010 and changes in demand for small business loans, was likely relatively small. Because the extent to which any of these other factors actually influenced lending levels is unknown, our analysis does not provide definitive conclusions about the effect of changes in the regulatory environment on small business lending. Rather, it provides reasonable information on the potential role of regulation (see app. II for a more complete discussion of our model's approach and limitations).

Specifically, as shown in figure 4, we found the following:

- Survivor community banks' business loans of $1 million or less. Our model of survivor community banks' outstanding business loans with original principal balances of $1 million or less found that the actual volume of these loans was on average 2 percent less than forecasted from 2010 through 2016, based on the macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics in place during this period.[45] Although the difference between the forecasted and actual volume of business loans with original principal balances of $1 million or less these banks made was relatively small throughout the period, this difference peaked a few years after the financial crisis (our model forecasted that the volume of outstanding business loans with original principal balances of $1 million or less would be 11 percent higher in 2013 than it actually was) before returning to a difference of 3 percent or less in 2014.

- All community banks' total loans to businesses. Our model of community banks' total outstanding business loans found that the actual volume of these loans was on average 16 percent more than our model forecasted from 2010 through 2016 given the macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics that prevailed during that period. Specifically, actual lending levels consistently exceeded the levels our model forecasted each year during this period, with actual loan balances ranging from 6 percent to 23 percent higher than forecasted from 2010 through 2016.

Figure 4: Actual Outstanding Amounts of Survivor Community Banks' Business Loans with Original Principal Balances of $1 Million or Less and All Community Banks' Total Business Loans Compared to Amounts Expected Based on Macroeconomic, Local Market, and Bank Characteristics, 2003–2016

Although our models found that the influence of factors other than macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics on small business lending was small, the direction of this influence (i.e., the extent to which these other factors contributed to actual lending that was higher or lower than what our models forecasted) varied.[46] Specifically, our model of survivor community banks' business loans of $1 million or less found that the actual volume of outstanding lending was lower in some years than our model forecasted. This difference in small business lending volumes was attributable to factors we did not include directly in our model, which may include the effect of post-2010 regulatory changes. However, lower-than-forecasted lending could also have been the result of changes in the demand for small business loans, or it could have been affected by some other factor for which we did not include data in our model.

In contrast, our model of community banks' total loans to businesses found that the actual volume of outstanding business loans was consistently higher than what our model forecasted given the macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics in place from 2010 through 2016. This difference may be the result of increasing demand for loans over $1 million (which were excluded from the Call Report data on small business lending) as compared to demand for loans under that amount. However, because the data banks report on their lending do not include information on specific loans or average loan amounts, the extent to which increased demand for larger loans affected our results is unknown.

Credit Unions Have Increased Small Business Lending since 2010

Although credit unions account for a small share of total bank and credit union small business lending, their lending to small businesses increased considerably from 2010 through 2017.[47] Our analysis of NCUA data found the following:

- Dollar amount of small business lending. Small business lending by credit unions increased by 109 percent from 2010 through 2017, from $12 billion in outstanding loans in 2010 to $25 billion in 2017.

- Number of small business loans. The number of small business loans by credit unions increased by about 85 percent, from about 79,000 outstanding loans in 2010 to about 146,000 outstanding loans in 2017.

As shown in figure 5, small business lending by credit unions increased each year from 2002 through 2017, indicating sustained growth. However, we cannot conclude that changes in the regulatory environment had no effect on credit union small business lending, because we do not know how credit union small business lending would have trended in the absence of such changes.[48]

Figure 5: Dollar Amount of Credit Union Small Business Loans Outstanding, 2001–2017

Community Banks Reported That the Regulatory Environment Was a Primary Reason for Changing Lending Processes

We found, based on our generalizable survey, that the majority of community banks changed their small business lending processes from January 2010 through August 2017, including increasing documentation requirements and processing time, and most cited the regulatory environment as the primary reason for these changes. A smaller proportion of credit unions also changed their small business lending processes, and the regulatory environment was the reason they cited most frequently.

Community Banks

We estimated, based on our survey results, that 79 percent of community banks increased documentation requirements for small business borrowers from January 2010 through August 2017.[49] As shown in figure 6, the regulatory environment was the top factor community bank representatives cited as the reason for this increase. Specifically, according to our survey, an estimated 97 percent of the community banks that reported increasing the amount of documentation they required borrowers to provide as part of obtaining a loan cited the regulatory environment as a factor that affected the increase to a moderate or great extent.[50] However, we estimated that about 50 percent of the community banks that increased documentation requirements also indicated that economic conditions affected this increase to a moderate or great extent.[51]

Figure 6: Survey Estimates of Factors Affecting the Increase in Documentation Required for Community Bank Small Business Loans, January 2010–August 2017

To obtain perspectives on the potential effect of changes to bank lending processes, we interviewed a judgmentally selected sample of small business advisers from six states' Small Business Development Centers as well as representatives of six small business advocacy groups.[52] A few of these small business advisers agreed that the amount of required documentation for obtaining loans had increased after the financial crisis, but the types of additional documentation sought by banks varied. One adviser said banks sought documentation they had not previously required, such as student loan information, appraisals, and personal asset verification. Representatives of one community bank also said they had introduced additional documentation requirements for small business loans beyond what was required by regulation—such as additional years of financial statements—to preempt any questions from bank examiners about borrowers' creditworthiness.

We also estimated, based on our survey results, that 69 percent of community banks increased the time they took to process small business loans from January 2010 through August 2017.[53] As shown in figure 7, almost all community banks that reported an increase in processing time attributed the increase to changes in the regulatory environment, among other factors. Community banks we interviewed also discussed reasons that processing time had increased. For example, one community bank said that the TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure, a requirement related to residential mortgage lending, increased the time needed to close loans that use residential real estate as collateral, which may include small business loans.[54] Although, according to FDIC officials, the TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure rule would likely not apply to these loans, as we have previously reported some compliance burdens arose from misunderstandings of the requirements.[55]

Figure 7: Survey Estimates of Factors Affecting the Increase in Time Needed to Make Community Bank Small Business Loans, January 2010–August 2017

Our survey also found that community banks changed their lending processes in other ways, including increasing fees, raising minimum credit criteria, or making other changes, and a majority of banks attributed these actions to changes in the regulatory environment (see table 2). However, as previously discussed, we found that the effect of the regulatory environment on the volume of community banks' small business lending appeared to be relatively modest, which suggests that changes to community banks' lending processes may not have significantly affected small business' ability to obtain loans.

Notes: We defined community banks using the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's definition, which takes into account institutions’ assets, foreign interests, specializations, and geographic characteristics. Community banks include banks with up to $39.5 billion in assets in 2017. We conducted a survey of the chief executive officers of 466 community banks from July 10, 2017 through August 25, 2017. Survey results are generalizable to the population of community banks. Confidence intervals are given at the 95 percent level of confidence.

Representatives of some community banks told us that they perceived a generally stricter regulatory environment, which could explain the decisions to make changes to their lending processes. A few community bank representatives we spoke with said their small business lending processes were affected by increased scrutiny of their lending activities during examinations, and several community bank representatives said they changed their processes in anticipation of increased scrutiny. For example, representatives of one community bank reported testing all potential commercial customers—including small businesses—to assess how they would react to different financial situations, although no regulation requires them to do so. In addition, some institutions could perceive a stricter regulatory environment because of fines imposed for regulatory infractions. Although not specifically related to small business lending, since 2010 federal agencies have collected billions of dollars in settlement payments and penalties from financial institutions for alleged violations of regulations related to mortgage loan origination and servicing and Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money laundering activities.[56]

Small business advisers had mixed views on the extent to which changes to banks' lending processes affected small businesses' ability to obtain loans. According to several advisers we interviewed, tightened credit standards since 2010 have made obtaining small business loans more difficult, and a few advisers said that meeting documentation requirements and higher credit standards was harder for newer small businesses. As a result, some advisers said small businesses were increasingly turning to alternative lenders for their credit needs. In contrast, other advisers said they did not think changes to lending processes affected the availability of credit for small businesses. For example, one small business adviser said he did not think increased fees would discourage small businesses from applying for loans.

Although few of the regulatory changes that have taken effect since 2010 directly relate to small business lending, community banks' small business lending processes may have been affected by regulatory changes in other areas. For example, a few community bank representatives we interviewed said that increased regulation related to residential mortgage lending had spillover effects into their small business lending activities, such as when a customer seeking a business loan used personal real estate as collateral.[57]

However, regulatory changes since 2010 may have also benefited community banks' small business lending and consumers. For example, FDIC officials told us that because regulatory changes have required community banks to hold more capital their safety and soundness has improved. In addition, some changes community banks made to their documentation requirements may have improved bank institution's safety and soundness. For example, as we reported in August 2010, origination features such as low or no documentation of income or assets may be associated with an increased likelihood of default.[58] Similarly, a few community bank representatives we interviewed said regulatory changes have helped community banks return to good business practices, and representatives from one small business advocacy group stated that regulatory changes have helped protect consumers.

Credit Unions

Our survey found that the majority of credit unions increased documentation requirements for small business loans from January 2010 through August 2017, and some credit unions also made other changes to their small business lending processes (see table 3).[59] Representatives of credit unions that changed their lending processes often cited changes in the regulatory environment as the reason, although few of the regulatory changes since 2010 directly relate to small business lending by credit unions.[60] In written comments provided in response to our survey, some credit union representatives cited increased regulatory scrutiny of their lending decisions, including examiners' requests for additional documentation of lending decisions, as affecting their small business lending.

Notes: We conducted a generalizable survey of 470 credit union chief executive officers of credit unions from July 17, 2017 through August 25, 2017. Our analysis considered only small and medium credit unions, which accounted for about 95 percent of all credit unions as of June 2017. We excluded large credit unions with total assets above an annual threshold (equal to $201 million in 2001 and $994 million in 2017). Confidence intervals are given at the 95 percent confidence level.

Factors Other Than Regulatory Environment Explain Most Changes in the Number and Financial Performance of Community Banks

Long-term community bank trends and macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics—rather than changes in the regulatory environment—appeared to explain most changes in the number of community banks and their market shares since 2010. In addition, although many institutions reported in our survey that they increased or reallocated staff and other resources to assist with regulatory compliance from 2010 through 2017, our analysis suggests that the effect of these changes on community banks' financial performance, if any, was minimal.

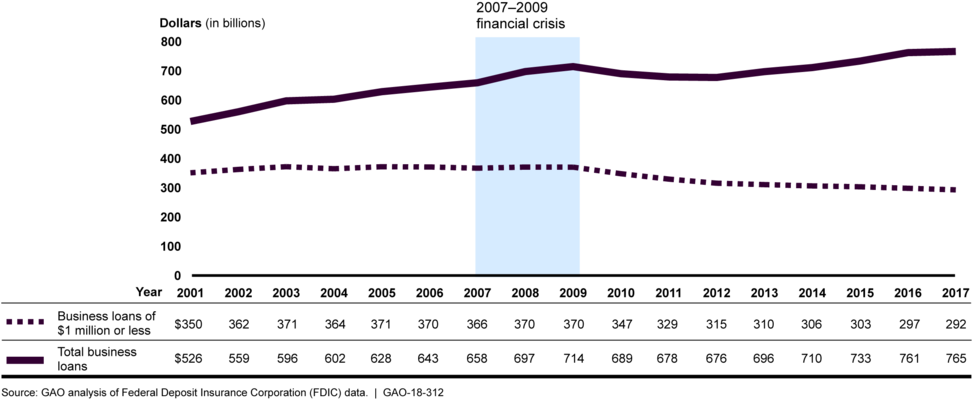

Regulatory Environment Likely Had a Relatively Small Effect on the Decline in Community Bank Numbers

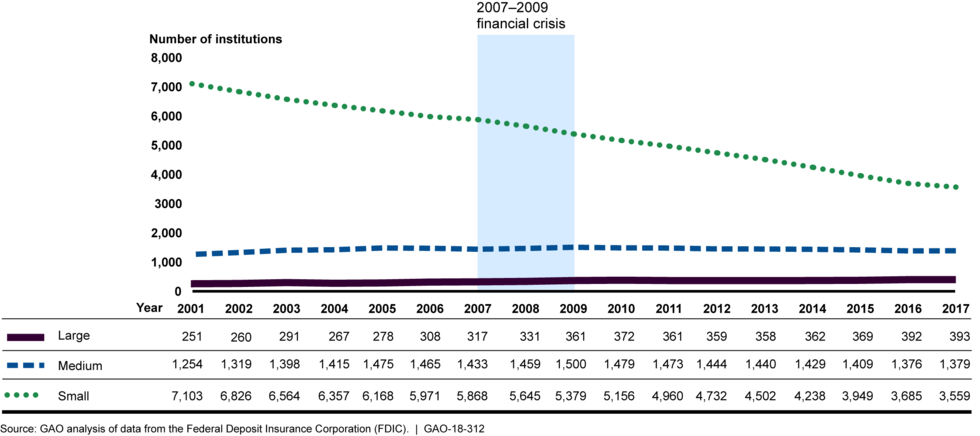

The number of community banks declined by about 24 percent from 2010 through 2017, from about 7,000 to about 5,300.[61] Similarly, the number of credit unions declined by 22 percent during this period. However, these declines are similar to those that occurred prior to 2010: from 2001 through 2009, the number of community banks declined by 16 percent, while the number of credit unions declined 24 percent.

Figure 8: Number of Community Banks, Credit Unions, and Large Banks, 2001–2017

The decline in the total number of community banks since 2010 has been most pronounced among small community banks—those with less than $300 million in assets in 2016 dollars—which declined by 31 percent from 2010 through 2017 (see fig. 9). These banks made up the majority—approximately 74 percent (about 5,200 banks)—of all community banks in 2010, but by 2017 their proportion of the total community bank population had declined to 67 percent. Conversely, the number of larger community banks—those with $1 billion or more in assets in 2016 dollars—increased by 6 percent during this period.[62]

Figure 9: Number of Community Banks, 2001–2017, by Community Bank Size Category

Our analysis indicates that from 2010 through 2017, approximately 1,800 community banks exited the population by merging, consolidating, or failing (see table 4):[63]

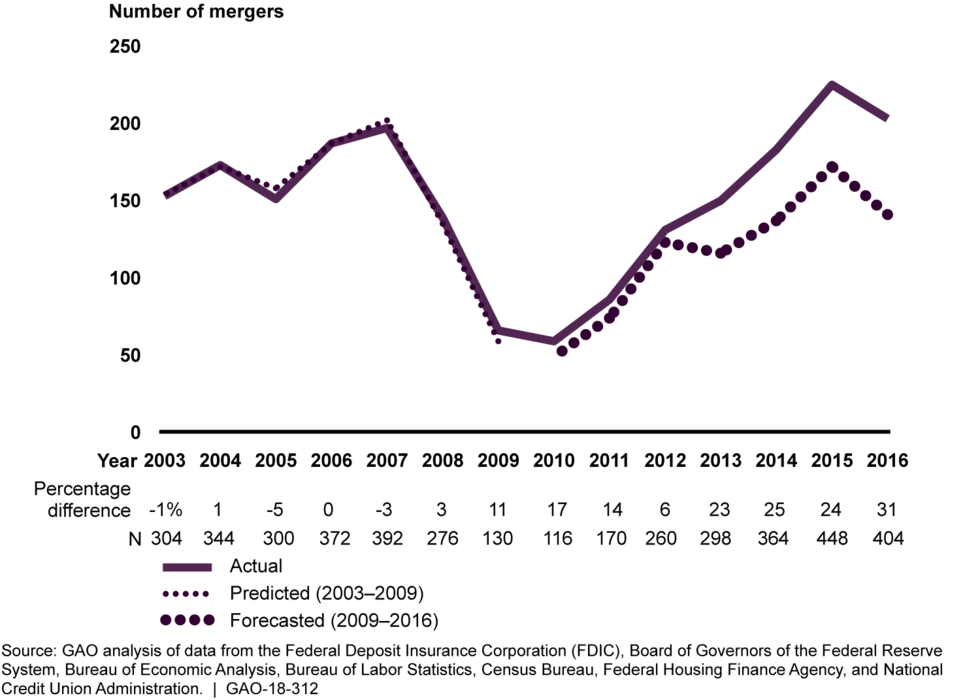

- Mergers. The majority of the exits from the community bank population—approximately 64 percent (1,181)—resulted from mergers and about 72 percent of these mergers were between community banks. A similar portion of exits—about 66 percent—resulted from mergers from 2001 through 2009, the period before and during the financial crisis. The majority of credit union exits from 2010 through 2017 were also due to mergers.

- Consolidations. Consolidations of related banks under one charter accounted for about 14 percent of community bank exits from 2010 through 2017.[64]

- Failures. Failures represented about 18 percent of community bank exits from 2010 through 2017.[65] Over two-thirds of these failures were in 2010 and 2011, the 2 years immediately after the 2007–2009 financial crisis.

Notes: We defined community banks using FDIC's definition, which takes into account institutions’ assets, foreign interests, specializations, and geographic characteristics. Community banks include banks with up to $39.5 billion in assets in 2017. We excluded large credit unions (those with total assets above an annual threshold equal to $201 million in 2001 and $994 million in 2017) from this analysis. Mergers are generally a means by which banks or credit unions can expand their size and geographic reach by combining with or acquiring other institutions that previously had different owners. Consolidations occur when an existing bank holding company combines related institutions holding separate charters. According to NCUA officials, no legal provision allows credit unions to consolidate. Institutions generally fail when their financial conditions have deteriorated to the point that they are unable to meet their obligations to depositors and others and they are closed by a federal or state regulator. Other exits include voluntary liquidations and unexplained closings. Percentages may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

Our econometric model estimated that macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics explained the majority of community bank mergers from 2010 through 2016. However, other factors—which could include changes in the regulatory environment, the availability of banks for mergers, and incentives to achieve economies of scale, among other things—likely had some effect.[66] The actual numbers of mergers for this period were, on average, 20 percent higher than our model forecasted, based on macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics at the time (see fig. 10).[67] This difference between actual and forecasted mergers indicates that other factors likely had some effect, although the effect was relatively small. This effect was most pronounced from 2013 through 2016 where the difference ranged from 23 to 31 percent.

Figure 10: Actual Number of Community Bank Mergers Compared to Number Expected Based on Macroeconomic, Local Market, and Bank Characteristics, 2003–2016

Banks may choose to merge in order to achieve economies of scale—that is, to increase their size to generate additional revenues at lower costs.[68] Although the existence of economies of scale in banking has been the subject of debate, some research suggests that banks can lower their costs by expanding.[69] Some community bank representatives we spoke with said banks consider merging to increase profitability and operational efficiency by becoming larger institutions. In response to changes in the regulatory environment since 2010, representatives of one community bank told us that their bank merged as a way to increase resources and staff, while maintaining profitability. In addition, FDIC analysis found that the number of banks, including community banks, has been declining since the 1980s, when federal and state legislative changes began relaxing geographic restrictions on banking activities and allowed banks to operate across multiple states under a single charter, resulting in mergers that reduced the number of banks.[70] For example, FDIC researchers found that bank numbers were steady for several decades prior to the 1980s, but declined by around 66 percent from 1980 through 2013.

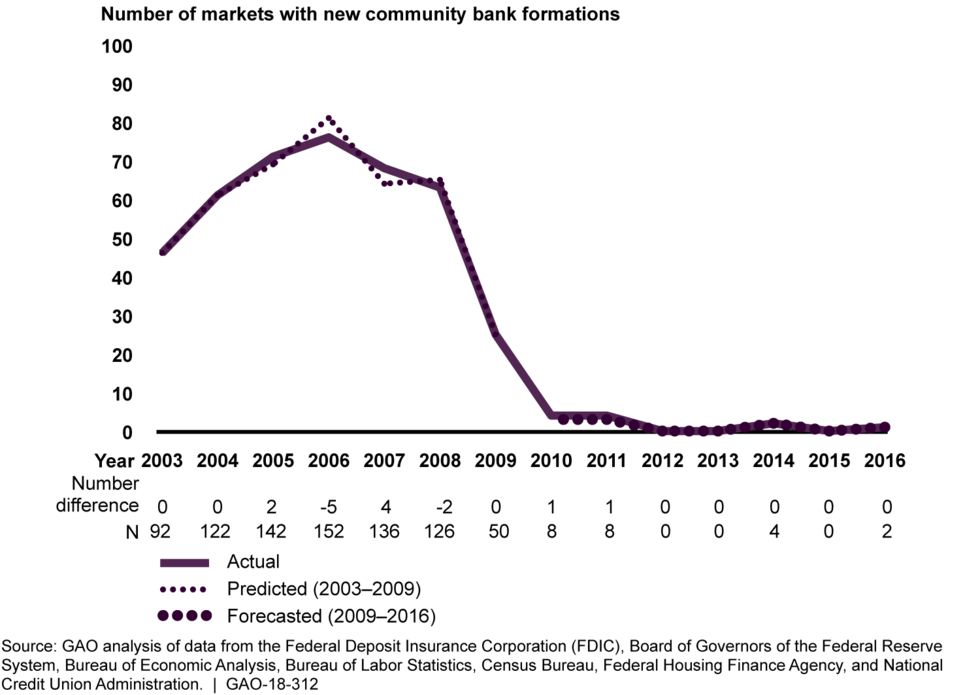

The overall decline in the number of community banks and credit unions is also related to the rate at which new institutions form, which was lower from 2010 through 2017 than in prior periods.[71] According to bank regulator data, only 10 new community banks formed during this period—a rate of approximately one new community bank per year (see fig. 11). In contrast, 814 new community banks formed from 2001 through 2009—a rate of 90 per year. Similarly, according to our analysis of NCUA data, 19 new credit unions formed from 2010 through 2017 (a rate of about 2 per year), while 62 new credit unions formed from 2001 through 2009 (about 7 per year).

Figure 11: Number of New Community Banks and Credit Unions, 2001–2017, by Type of Institution

Our econometric analysis found that macroeconomic and local market characteristics were the primary factors affecting the rate of new community bank formations from 2010 through 2016. Specifically, our model forecast that the prevailing macroeconomic and local market characteristics would result in relatively few new community bank formations (no more than three markets with new bank formations in any one year) from 2010 through 2016; the actual number of new community bank formations that did occur exceeded this model's forecast, but only slightly (see fig. 12).[72] The similarity between the actual and forecasted numbers of new bank formations suggests that the effect of changes in the regulatory environment on new community bank formation was relatively small. This result was similar to a 2014 Federal Reserve study that found that economic conditions explained the majority of the decline in new banks.[73]

Figure 12: Actual Number of Markets with New Community Bank Formations Compared to Number Expected Based on Macroeconomic and Local Market Characteristics, 2003–2016

Number and Geographic Location of Community Bank Branches

From 2010 through 2017, the number of community bank branches—which are defined as all locations that accept deposits—declined, and our survey results and interviews suggest that these changes were due to various factors. According to our analysis of FDIC data, the number of community bank branches decreased by 15 percent from 2010 through 2017, from about 35,000 to about 30,000. This decrease reversed the previous trend of increasing numbers of branches leading up to the 2007–2009 financial crisis: according to FDIC data, from 2001 through 2009, the number of branches increased 6 percent, from about 33,000 to about 35,000.

Based on our survey results, we estimated that 20 percent of community banks closed one or more branches from January 2010 through August 2017.[74] Our survey results suggest that multiple factors, including changes in the regulatory environment, economic conditions, and technological advances, influenced these closures.[75] Representatives from some community banks we interviewed said branch opening and closing decisions are often based on branch profitability and growth opportunities, which stem from economic conditions, and that closures did not have major effects on customers. In contrast, our prior work found that compliance with Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money laundering regulations along with other factors, including demographic factors, contributed to bank branch closures.[76]

The number of community bank branches in about half of U.S. counties increased or remained the same in 2010 and 2017, while the number decreased in the other half of counties (see fig. 13). Additionally, although small, the percentage of counties with no community bank branches increased slightly in 2017 as compared with 2010.[77]

Figure 13: Changes in the Number of Community Bank Branches at the County Level, in 2010 and 2017

The distribution of community bank branches between urban and rural areas appears to have remained largely unchanged from 2010 through 2017. The majority of community bank branches are located in urban areas—about 70 percent in 2017—and declines in the number of branches were largest in urban areas (see table 5).[78]

Notes: We defined community banks using FDIC's definition, which takes into account institutions’ assets, foreign interests, specializations, and geographic characteristics. Community banks include banks with up to $39.5 billion in assets in 2017. We define "urban" and "rural" areas using the Department of Agriculture's Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes. These codes classify all census tracts in the United Sates on a 10-tier continuum from rural to urban based on daily commuting patterns, urbanization, and population density. For our analysis, we collapsed the 10 tiers into 4, where 2 tiers are considered rural and the other 2 are considered urban. The totals in this table exclude 15 community bank branches in 2010 and 9 in 2017, because we were unable to classify the branch locations as urban or rural.

Our analysis of NCUA data shows that from 2012 (the first year for which reliable data are available) through 2017, the number of credit union branches decreased by 5 percent, from about 16,000 to about 15,000. Based on our survey results, we estimated that 22 percent of credit unions closed one or more branches from January 2010 through August 2017 or were in the process of closing a branch. [79] Some credit union representatives we interviewed said credit unions make decisions about branch openings and closings based on the profitability of individual branches or member needs.

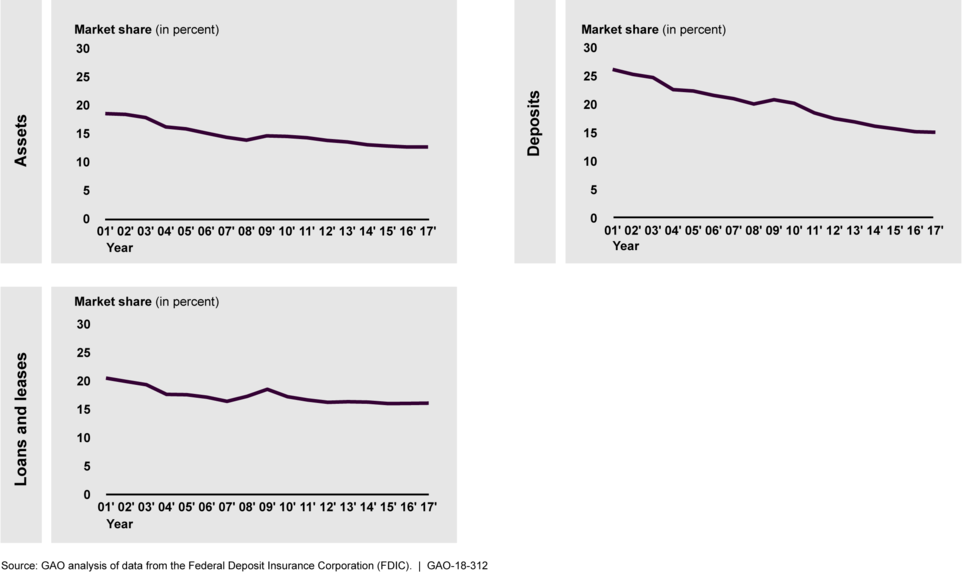

Market Share of Bank Activities

Along with decreases in the number of community banks, their market shares of banking activities—total banking assets, deposits, and loans and leases—decreased from 2010 through 2017.[80] For example, their share of total assets declined from 15 percent in 2010 to 13 percent in 2017, and their share of total deposits declined from 20 percent in 2010 to 15 percent in 2017.

Figure 14: Community Banks' Market Share of Total Assets, Deposits, and Loans and Leases, 2001–2017

These declines appear to be part of longer-term trends to some degree. As figure 14 shows, although community banks’ market shares rose during the 2007–2009 financial crisis, their slight declines since then continued an overall downward trend in community bank market shares from at least 2001. According to FDIC officials, the loss of market shares by community banks may, in part, be the result of the Federal Reserve expanding its balance sheet and providing hundreds of billions in additional balances into the banking system in response to the financial crisis.

Credit unions' market shares of total assets, deposits, and loans and leases were largely unchanged.[81] From 2010 through 2017, their market shares of total assets, deposits, and loans and leases each changed by less than 1 percentage point.

The Effect of Regulatory Changes on Community Bank Financial Performance Is Likely Modest

In response to changes in the regulatory environment, community banks and credit unions may hire additional staff or outside consultants, invest in new software, or take other actions to help comply with new requirements. As a result, the number of employees and the administrative and personnel costs are likely to increase, and profits and performance are likely to decrease, all else being equal. However, while our survey results suggest many community banks and credit unions made such changes in response to regulations, these changes appear to have had minimal effects on community banks' and credit unions' total employment levels, expenses, and financial performance. Additionally, our econometric analysis suggests that the effects of changes in the regulatory environment on community bank profitability were likely small.

Changes in Employment

Our survey results indicated that most community banks and credit unions increased or reallocated staff from January 2010 through August 2017 to assist with changes in the regulatory environment, but FDIC and NCUA data for banks and credit unions showed no increases in total employment for these institutions.[82] Based on our survey, an estimated 73 percent of community banks hired additional staff and 86 percent reallocated existing staff to assist with changes in the regulatory environment.[83] However, our analysis of FDIC data found that total employment levels at these institutions decreased slightly from 2010 through 2017 (see fig. 15).[84] Based on our survey of credit unions, we estimated that most credit unions (61 percent) did not hire additional staff from January 2010 through August 2017, but that 61 percent of credit unions reallocated existing staff to assist with changes in the regulatory environment.[85] Similarly, our analysis of NCUA data shows that the median numbers of full-time and part-time credit union employees decreased during this period.

Figure 15: Median Number of Employees per $1 Million in Assets, 2001–2017 for Community Banks and Credit Unions, by Type of Institution

Our survey results suggest that institutions’ decisions to reallocate existing staff to assist with changes in the regulatory environment were driven or offset by other changes. For example, to help mitigate the negative effects of changes in staffing, institutions may have made greater use of technology. Of the community banks that decreased the time staff spend engaging directly with individual customers (an estimated 18 percent of community banks overall), an estimated 87 percent attribute that decision to technological advances.[86] Furthermore, an estimated 89 percent of community banks and 92 percent of credit unions increased their investments in customer-facing technologies, such as online or mobile banking.[87] Shifts in staffing allocations may also have resulted in decreased availability of products and services; however, our survey results found that most community banks and credit unions did not decrease the time staff spend engaging with customers or identifying new and innovative products. Based on our survey, we estimated that 83 percent of community banks and 82 percent of credit unions increased or did not change the time staff spend engaging directly with individual customers during this period.[88] Similarly, an estimated 91 percent of community banks and 97 percent of credit unions increased or did not change the time staff spend identifying new or innovative products.[89]

Changes in Operating Expenses

Many survey respondents reported spending on outside services to help assist with changes in the regulatory environment, but our analysis found that noninterest expenses—a measure that includes these and other regulatory compliance costs, as well as salaries, employee benefits, and consulting and advisory expenses—decreased overall. According to our survey results, an estimated 96 percent of community banks and 78 percent of credit unions hired a third party or purchased additional software or automated systems to assist with changes in the regulatory environment from January 2010 through August 2017.[90] As figure 16 shows, median noninterest expenses as a percentage of assets for community banks increased prior to and during the 2007–2009 financial crisis but then declined through 2017.[91] Similarly, credit unions' median noninterest expenses as a percentage of assets increased leading up to the financial crisis but have since declined to below precrisis levels.

Figure 16: Median Noninterest Expenses, 2001–2017 for Community Banks and Credit Unions, by Type of Institution

Community bank and credit union financial performance also improved from 2010 through 2017. In the prior period from 2001 through 2009, community banks' median efficiency ratio—a measure of operating expenses as a proportion of income—increased from 66 percent to 74 percent (see fig. 17), suggesting a decline in efficiency.[92] However, the ratio for these institutions has since decreased to 69 percent in 2017, indicating slightly greater efficiency. Similarly, from 2001 through 2009, credit unions' median efficiency ratio increased from about 85 percent to about 92 percent; however, it then improved to about 90 percent in 2017.

Figure 17: Median Efficiency Ratio, 2001–2017 for Community Banks and Credit Unions, by Type of Institution

Changes in Profitability

Our analysis of FDIC data suggests that community bank profitability is increasing and that regulatory environment has likely not negatively affected profitability significantly. Specifically, the median pretax return on assets—a measure of profitability—for the population of all community banks decreased leading up to and during the 2007–2009 financial crisis (see fig. 18).[93] From 2010 through 2017, however, the median return on assets for the population increased, although it remains below precrisis levels.[94] Similarly, credit unions’ median return on assets decreased during the financial crisis but increased from 2010 through 2017.

Figure 18: Median Return on Assets, 2001–2017 for Community Banks and Credit Unions, by Type of Institution

Our econometric analysis found that community bank profitability was higher from 2010 through 2016 than would have been expected based on macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics at the time.[95] Specifically, our model found that, on average, community banks’ actual return on assets was 40 basis points higher than our model forecasted given the macroeconomic, local market, and bank characteristics in place during the post-crisis period from 2010 through 2016 and despite any change in the regulatory environment.[96] This effect was most pronounced in 2010 (immediately after the crisis), when the actual return on assets did not dip as low as our model forecasted, and in 2012 and 2013—community banks’ return on assets was 70 basis points higher than would have been expected. From 2014 through 2016, actual return on assets continued to be higher than our model forecasted, but the difference was smaller.

Figure 19: Actual Community Bank Pretax Return on Assets Compared to Returns Expected Based on Macroeconomic, Local Market, and Bank Characteristics, 2003–2016

The difference between actual community bank return on assets and what the model forecasted is attributable to the influence of the “other factors” category, which could include the influence of weaker banks exiting from the population. For example, FDIC reported that from 2009 through 2012 (during and following the crisis), many weaker banks exited, which may have contributed to an upturn in overall community bank profitability.[97] In addition, FDIC found that banks acquired during a merger from 2010 through 2016 had lower profitability than their peers—removing these weaker institutions from the population of community banks could also explain the higher-than-forecasted return on assets.[98] However, the individual influence of the other factors is unknown, which limits our ability to determine the cumulative effect of these other factors on community bank return on assets.

Finally, the influence of changes in the regulatory environment on the number and financial performance of community banks and credit unions is not necessarily an indication of undue burden; such changes could also result in benefits to individual institutions and the overall financial system. A change in a bank's or credit union's behavior may be the appropriate result of the regulators addressing weak business practices, and federal oversight serves, in part, to help ensure that these institutions do not take excessive risks that could undermine their safety and soundness.

Regulators Have Taken Steps to Analyze and Mitigate the Effects of Regulatory Changes on Small Business Lending