Highlights

What GAO Found

GAO’s 2019 annual report identifies 98 new actions that Congress or executive branch agencies can take to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government in 28 new areas and 11 existing areas. For example:

- The Department of Energy could potentially avoid spending billions of dollars by developing a program-wide strategy to improve decision-making on cleaning up radioactive and hazardous waste to address the greatest human health and environmental risks.

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services could also potentially save hundreds of millions of dollars by improving how it identifies and targets risk in overseeing Medicaid expenditures to identify and resolve errors.

- Congress could enhance federal revenue by at least tens of millions of dollars annually through expanding the definition of allowable expenses authorized to be covered by the Foreign Military Sales administrative account, thereby likely reducing the need to cover these expenses with other appropriated funds.

- The Department of Defense could expand its use of intergovernmental agreements to obtain military installation support services—such as waste management and snow removal—and potentially save millions of dollars annually.

- The Department of Defense could also potentially save millions of dollars in its administration of military treatment facilities—such as hospitals and dental clinics—by analyzing medical functions for duplication, validating headquarters-level personnel requirements, and identifying the least costly mix of personnel.

- The Department of Homeland Security should develop a strategy and implementation plan to help guide, support, integrate, and coordinate its multiple chemical defense programs and activities to better manage these fragmented efforts.

- The federal agencies that coordinate research on quantum computing and synthetic biology could better manage fragmentation by agreeing on roles and responsibilities and identifying outcomes to help agencies improve their research efforts to maintain U.S. competitiveness in these areas.

GAO identified 33 new actions related to 11 existing areas presented in its 2011 to 2018 annual reports. For example:

- Congress could provide the Internal Revenue Service the authority to require scannable codes on tax returns prepared electronically, but filed on paper, to improve its ability to combat tax fraud and noncompliance and save tens of millions of dollars annually.

- The U.S. Mint could potentially reduce the cost of coin production by millions of dollars annually by changing the metal content of currency.

- The Department of Defense could collect cost and technical data and lessons learned to make more informed decisions on using commercial spacecraft to host government sensors and communications packages, which could lead to considerable cost savings.

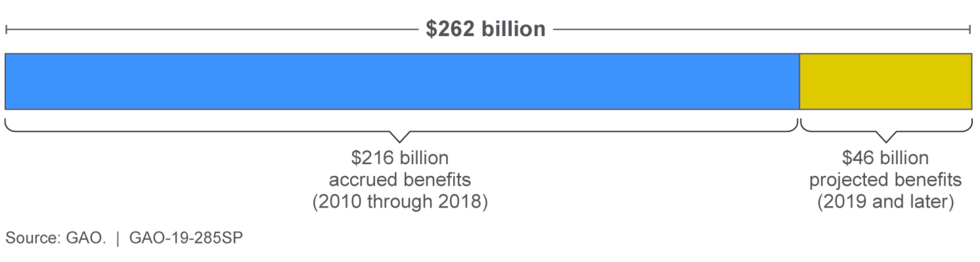

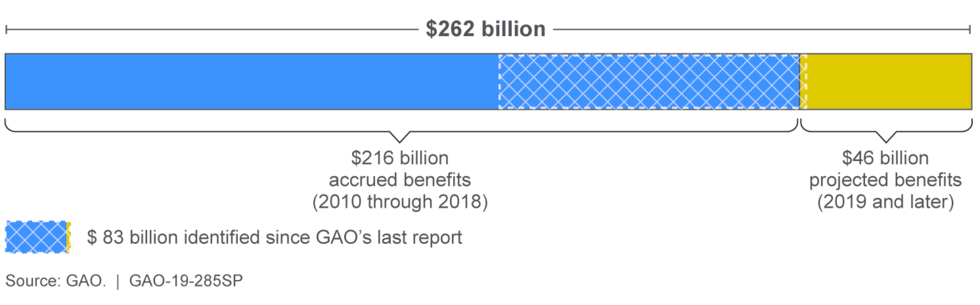

Significant progress has been made in addressing many of the 805 actions that GAO identified from 2011 to 2018 to reduce costs, increase revenues, and improve agencies’ operating effectiveness. As of March 2019, Congress and executive branch agencies have fully addressed 436 actions (54 percent) and partially addressed 185 actions (23 percent). This has resulted in approximately $262 billion in financial benefits. About $216 billion of these benefits accrued between 2010 and 2018 and $46 billion are projected to accrue in future years. These are rough estimates based on a variety of sources that considered different time periods and utilized different data sources, assumptions, and methodologies.

While Congress and executive branch agencies have made progress toward addressing actions that GAO has identified since 2011, further steps are needed. GAO estimates that tens of billions of additional dollars could be saved should Congress and executive branch agencies fully address the remaining 396 open actions, including the new ones identified in 2019. Addressing the remaining actions could lead to other benefits as well, such as increased public safety, better homeland and national security, and more effective delivery of services. For example:

| Area name and description (year-number links to Action Tracker) | Mission | Potential benefits (source when financial) |

| DOE’s Treatment of Hanford’s Low Activity Waste (2018-17): The Department of Energy may be able to reduce certain risks by adopting alternative approaches to treating a portion of its low-activity radioactive waste. | Energy | Tens of billions (GAO) |

| Defense Headquarters (2012-34): The Department of Defense could review and identify further opportunities for consolidating or reducing the size of headquarters organizations. | Defense | $9.4 billion (National Defense Authorization Act) |

| Disability and Unemployment Benefits (2014-08): Congress should consider passing legislation to prevent individuals from collecting both full Disability Insurance benefits and Unemployment Insurance benefits that cover the same period. | Income security | $2.5 billion over 10 years (Office of Management and Budget) |

| Medicare Payments by Place of Service (2016-30): Medicare could have cost savings if Congress were to equalize the rates Medicare pays for certain health care services, which often vary depending on where the service is performed. | Health | Billions annually (GAO) |

| IRS Strategic Workforce Planning (2019-07): The Internal Revenue Service should address its fragmented human capital activities to improve its strategic workforce planning so it can better meet challenges to achieving its mission. | General government | Identify and address skills gaps in mission critical occupations |

| Military and Veterans Health Care (2012-15): The Departments of Defense (DOD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) need to improve integration across care coordination and case management programs to reduce duplication and better assist servicemembers, veterans, and their families. | Health | Better care from and management of DOD and VA Healthcare programs |

Note: All estimates of potential savings are dependent on various factors, such as whether action is taken and how it is taken. Actual savings may be less, depending on costs associated with implementing the action, unintended consequences, and the impact of other factors that could/should be controlled for. For estimates of potential financial benefits, GAO developed the notional estimates, which are intended to provide a sense of potential magnitude of savings. Notional estimates have been developed using broad assumptions about potential savings which are rooted in previously identified losses, the overall size of the program, previous experience with similar reforms, and similar rough indicators of potential savings.

Why GAO Did This Study?

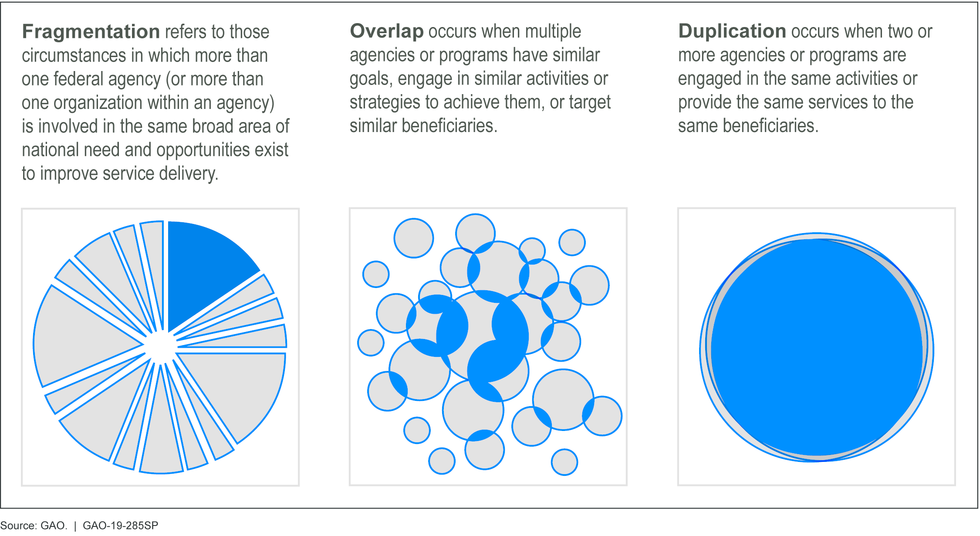

The federal government continues to face an unsustainable long-term fiscal path caused by an imbalance between federal revenue and spending. While addressing this imbalance will require difficult policy decisions, opportunities exist in a number of areas to improve this situation, including where federal programs or activities are fragmented, overlapping, or duplicative.

To call attention to these opportunities, Congress included a provision in statute for GAO to identify and report on federal programs, agencies, offices, and initiatives—either within departments or government-wide—that have duplicative goals or activities. GAO also identifies areas that are fragmented or overlapping and additional opportunities to achieve cost savings or enhance revenue collection.

This report discusses the new areas identified in GAO’s 2019 annual report; the progress made in addressing actions GAO identified in its 2011 to 2018 reports; and examples of open actions directed to Congress or executive branch agencies.

To identify what actions exist to address these issues, GAO reviewed and updated prior work, including recommendations for executive action and matters for congressional consideration.

Introduction

May 21, 2019

Congressional Addressees

The federal government continues to face an unsustainable long-term fiscal path caused by an imbalance between federal revenue and spending, primarily driven by health care spending and interest on debt held by the public (net interest).[1] Addressing this imbalance will require difficult policy decisions about long-term changes to both spending and revenue. Acting soon to mitigate this imbalance would help to minimize the disruption to individuals and the economy.

Meanwhile, Congress and executive branch agencies have opportunities to contribute toward fiscal sustainability and act as stewards of federal resources. One way is to take action to reduce, eliminate, or better manage fragmentation, overlap, or duplication; achieve cost savings; or enhance revenues. To call attention to these opportunities, Congress included a provision in statute for us to identify and report to Congress on federal programs, agencies, offices, and initiatives—either within departments or government-wide—that have duplicative goals or activities.[2] As part of this work, we also identify additional opportunities to achieve greater efficiency and effectiveness that result in cost savings or enhanced revenue collection.

In eight annual reports issued from 2011 to 2018, we presented more than 300 areas and more than 800 actions for Congress or executive branch agencies to reduce, eliminate, or better manage fragmentation, overlap, or duplication; achieve cost savings; or enhance revenues.[3] Congress and executive branch agencies have partially or fully addressed 621 (77 percent) of the actions we identified from 2011 to 2018, resulting in about $262 billion in financial benefits. We estimate tens of billions more dollars could be saved by fully implementing our open actions.[4]

Figure 1 defines the terms we use in this work.

This report is our ninth in the series, and it identifies 28 new areas where a broad range of federal agencies may be able to achieve greater efficiency or effectiveness.

For each area, we suggest actions that Congress or executive branch agencies could take to reduce, eliminate, or better manage fragmentation, overlap, or duplication, or achieve other financial benefits. In addition to identifying new areas and actions, we continue to monitor the progress Congress and executive branch agencies have made in addressing actions we previously identified (see text box).

This report is based upon work we previously conducted in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards or our quality assurance framework. See appendix I for more information on our scope and methodology.

| GAO's online Action Tracker GAO's Action Tracker, a publicly accessible website, allows Congress, executive branch agencies, and the public to track the government's progress in addressing the issues we have identified. GAO's Action Tracker includes a downloadable spreadsheet containing all actions. Areas and actions in the spreadsheet can be sorted and filtered by the year identified, mission, area name, implementation status, and implementing entities (Congress or executive branch agencies). The spreadsheet additionally notes which actions are also GAO priority recommendations--those recommendations GAO believes warrant priority attention from the heads of departments or agencies. With the release of this report, GAO is concurrently releasing the latest updates to these resources. |

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

New Opportunities Exist to Improve Efficiency and Effectiveness across the Federal Government

This report presents 98 new actions that Congress or executive branch agencies could take across 28 new areas.[5] Of these 28 new areas, 17 concern fragmentation, overlap, or duplication in government missions and functions (see table 1). Appendix II provides more detailed information about the 17 new areas.

We also present 11 areas where Congress or executive branch agencies could take action to reduce the cost of government operations or enhance revenue collections for the U.S. Treasury (see table 2). Appendix III provides more detailed information about these new areas.

In addition to these 28 new areas, we identified 33 new actions related to 11 existing areas presented in our 2011 to 2018 annual reports (see table 3).[6] Appendix IV provides more detailed information about these new actions.

| Mission | New action (area name links to Action Tracker) | Year introduced (year links to report) |

| Defense | 1. Prepositioning Programs: In January 2019, GAO identified two new actions to help fully implement joint oversight of the Department of Defense’s prepositioned stocks programs and to reduce fragmentation. | |

| Energy | 2. Strategic Petroleum Reserve: In May 2018, GAO identified two new actions to help the federal government potentially realize savings by examining the optimal size of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. | |

| General government | 3. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Facility Construction: In July 2018, GAO identified three new actions to improve the accuracy of project budgets and better manage project delays and cost increases. | |

| 4. Financial Regulatory Structure: In March 2018, GAO identified five new actions to help reduce fragmentation and improve collaboration among federal financial regulators. | ||

| 5. Identity Theft Refund Fraud: In June 2018, GAO identified four new actions to help the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) prevent refund fraud associated with identity theft. | ||

| 6. Government-wide Improper Payments: In May 2018, GAO identified two new actions to help the federal government address the long-standing problem of improper payments. | ||

| 7. Government Satellite Program Costs: In July 2018, GAO identified a new action to help the Department of Defense make more informed decisions on using commercial spacecraft to host government sensors and communications packages, which could lead to considerable cost savings. | ||

| 8. U.S. Currency: In March 2019, GAO identified a new action to potentially reduce the cost of coin production by millions of dollars annually. | ||

| 9. Tax Fraud and Noncompliance: In July 2018, GAO identified six new actions to help IRS combat tax fraud and noncompliance and save tens of millions of dollars annually. | ||

| Training, employment, and education | 10. Employment and Training Programs: In March 2019, GAO identified a new action to help the Department of Labor evaluate whether actions to manage fragmentation and overlap among employment and training programs are working. | |

| 11. Higher Education Assistance: In November 2016, GAO identified six new actions to help the Department of Education improve its income-driven repayment plan budget estimates. |

Congress and Executive Branch Agencies Continue to Address Actions across the Federal Government

Congress and executive branch agencies have made consistent progress in addressing many of the actions we have identified since 2011, as shown in table 4. As of March 2019, they had fully addressed 436 (54 percent) of the actions we identified from 2011 to 2018. See GAO’s online Action Tracker for the status of all actions.

aIn assessing actions suggested for Congress, GAO applied the following criteria: “addressed” means relevant legislation has been enacted and addresses all aspects of the action needed; “partially addressed” means a relevant bill has passed a committee, the House of Representatives, or the Senate during the current congressional session, or relevant legislation has been enacted but only addressed part of the action needed; and “not addressed” means a bill may have been introduced but did not pass out of a committee, or no relevant legislation has been introduced. Actions suggested for Congress may also move to “addressed” or “partially addressed,” with or without relevant legislation, if an executive branch agency takes steps that address all or part of the action needed. At the beginning of a new congressional session, GAO reapplies the criteria. As a result, the status of an action may move from partially addressed to not addressed if relevant legislation is not reintroduced from the prior congressional session.

bIn assessing actions suggested for the executive branch, GAO applied the following criteria: “addressed” means implementation of the action needed has been completed; “partially addressed” means the action needed is in development or started but not yet completed; and “not addressed” means the administration, the agencies, or both have made minimal or no progress toward implementing the action needed.

cOf the 69 “other” actions, GAO categorized 42 as “consolidated or other” and 27 as “closed-not addressed.” GAO no longer assesses actions categorized as “consolidated or other” and “closed-not addressed.” In most cases, “consolidated or other” actions were replaced or subsumed by new actions based on additional audit work or other relevant information. GAO generally categorizes actions as “closed-not addressed” when the action is no longer relevant due to changing circumstances.

As we have reported, it frequently takes multiple years for actions to be fully addressed, in part because many of the actions involve significant issues that require action from multiple agencies. Thus, more recommendations are implemented over time. For example, as of March 2019 executive branch agencies had addressed 88 percent of the actions introduced in the 2013 report, compared to 20 percent of the actions introduced in the 2018 report.[7]

Actions Taken by Congress and Executive Branch Agencies Led to Billions in Financial Benefits

As a result of steps Congress and executive branch agencies have taken to address our open actions, we have identified approximately $262 billion in total financial benefits, including $83 billion identified since our last report. About $216 billion of the total benefits accrued between 2010 and 2018, while approximately $46 billion are projected to accrue in 2019 or later, as shown in figure 2.[8]

Figure 2: Total Reported Financial Benefits of $262 Billion, as of March 2019

Table 5 highlights examples of these results.

| Area name (year-number links to Action Tracker) | Actions taken | Financial benefit |

| Congress passed the Agricultural Act of 2014, which eliminated direct payments to farmers.a | Savings of approximately $44.5 billion from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2023, of which $19.8 billion has accrued and $24.7 billion is expected to accrue in fiscal year 2019 or later, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). | |

| Congress passed the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009, which implemented a number of GAO’s recommendations for how the Department of Defense (DOD) develops and acquires weapon systems. GAO highlighted the need for additional action in this area in its 2011 report. Since then, DOD has followed more best practices for these acquisitions.b | Savings of approximately $43.8 billion from 2011 through 2017, according to GAO analysis. | |

| The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) changed processes to curtail some problematic methods used to determine spending limits for Medicaid Demonstrations, restricted the amount of unspent funds states can accrue and carry forward to expand demonstrations, and could further reduce federal spending by addressing other problematic methods. | Savings of approximately $36.8 billion in 2016 and 2017, and tens of billions of additional savings could potentially accrue in the future according to agency estimates. | |

| Congress allowed the Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit to expire at the end of 2011, which eliminated duplicative federal efforts directed at increasing domestic ethanol production.c | Reduced revenue losses by $29 billion from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2016, according to GAO analysis. | |

| The Department of Education changed its estimation approach for calculating the cost of Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans, allowing the agency to transfer unused funds to the Treasury. | Financial benefits of approximately $24.2 billion during fiscal year 2018, according to agency estimates. | |

| Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, which modified the passenger security fee from its current per enplanement structure ($2.50 per enplanement with a maximum one-way-trip fee of $5.00) to a structure that increases the passenger security fee to a flat $5.60 per one-way-trip.d | Increased revenue of about $12.9 billion in fee collections over a 10-year period beginning in fiscal year 2014 and continuing through fiscal year 2023, according to CBO and other estimates. | |

| The Department of Veterans Affairs evaluated strategic sourcing opportunities, set goals, tracked metrics, and ultimately procured a larger share of goods and services–including information technology (IT)–using contracts aligned with strategic sourcing principles. | Cost avoidance of about $10.6 billion from fiscal years 2013 through 2017, according to GAO estimates. | |

| Congress amended the audit procedures applicable to certain large partnerships to require that they pay audit adjustments at the partnership level.e | Increased revenue of $9.3 billion from fiscal years 2019 to 2025, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. | |

| The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) updated its analysis of estimated future expenditures for the Making Home Affordable program, reducing the estimated lifetime cost of the program. | Savings of $6 billion as a result of deobligating funds in December 2016, according to agency estimates. | |

| The Department of Housing and Urban Development made improvements to increase the recoveries from disposing of properties it receives when loans default, such as by selling these loans and increasing property inspections and oversight of contractors disposing of these properties. | Savings of as much as $5.4 billion from July 2013 through June 2018, according to GAO estimates. | |

| The 24 federal agencies participating in the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) data center consolidation and optimization efforts have taken steps to consolidate over 6,200 data centers as of August 2018. | Cost savings and avoidances of $4.2 billion from fiscal years 2011 through 2019, based on GAO analysis of agency reported data. This includes about $468 million expected to accrue in fiscal year 2019, according to agency plans. | |

| United States Forces Korea conducted a series of consultations with the military services to evaluate the costs and benefits associated with tour normalization, and DOD decided not to move forward with the full tour normalization initiative because it was not affordable. | Savings of an estimated $3.1 billion from fiscal years 2012 through 2016, according to agency estimates. | |

| Congress limited preparedness grant funding until the Federal Emergency Management Agency completes a national preparedness assessment of capability gaps.f | Savings of $2.6 billion from fiscal years 2011 through 2013, according to GAO estimates. | |

| Congress has taken steps to increase the minimum adjustment made for differences in diagnostic coding patterns between Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare providers. | Savings of approximately $2.5 billion from fiscal years 2013 through 2022, of which $1.5 billion has accrued and $1 billion is expected to accrue in fiscal year 2019 or later according to CBO. | |

| Information Technology Investment Portfolio Management (2014‑24) | Nine agencies migrated commodity IT areas to shared services in response to OMB’s 2012 guidance to review their portfolios and identify duplicative, low-value, and wasteful investments, contributing to savings. | Savings of an estimated $2.5 billion from fiscal years 2012 through 2017, and billions in additional savings could potentially accrue in the future according to agency estimates. |

| DOD canceled the Air Force’s Expeditionary Combat Support System because of significant cost and schedule overages. | Savings of about $1.6 billion from fiscal years 2013 through 2025, according to GAO analysis of agency estimates. This includes about $862 million expected to accrue in fiscal year 2019 or later. | |

| The Department of Energy (DOE) completed a long-term strategic review of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve in August 2016, as Congress required in 2015. | DOE reported savings of $1.2 billion from selling crude oil from the reserve in fiscal years 2017 and 2018, with potential for over $8.4 billion in total sales through 2025 according to CBO. |

Note: The estimates in this report are from a range of sources, including GAO, executive branch agencies, CBO, and the Joint Committee on Taxation. Some estimates have been updated since GAO’s 2018 report to reflect more recent analysis.

aPub. L. No. 113-79, § 1101, 128 Stat. 649, 658 (2014).

bPub. L. No. 111-23, 123 Stat. 1704 (2009).

c26 U.S.C. § 6426(b)(6).

dPub. L. No. 113-67, § 601(b), 127 Stat. 1165, 1187 (2013).

eBipartisan Budget Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-74, § 1101, 129 Stat. 584, 625–638 (2015).

fPub. L. No. 112-10, § 1632, 125 Stat. 38, 143 (2011); Pub. L. No. 112-74, 125 Stat. 786, 960–962 (2011); Pub. L. No. 113-6, 127 Stat. 198, 358–360 (2013); Pub. L. No. 113-76, 118 Stat. 5, 261–262 (2014).

Other Benefits Resulting from Actions Taken by Congress and Executive Branch Agencies

Our suggested actions, when implemented, often result in benefits—for instance, more effective and equitable government; improvements in major government programs or agencies; and increased assurance that programs comply with laws and that funds are legally spent. The following examples illustrate these types of benefits.

- Defense Weather Satellites (2017-04): DOD’s weather satellites have provided data to support both military and civilian operations for more than 50 years. As these weather satellites aged, DOD faced potential gaps in its ability to monitor the weather. In 2016, we found that DOD had not effectively collaborated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to assess the availability of data for some of its highest priorities.

- We recommended that DOD establish formal mechanisms to work with NOAA. DOD agreed, and in late 2017, NOAA signed a memorandum of agreement with the Air Force and the Navy regarding exchanging information, collaboration, and interagency acquisitions. These actions will help NOAA and DOD update weather satellite capabilities. Because of this progress and other actions, in 2019 we removed the Mitigating Gaps in Weather Satellite Data area from our High-Risk List.[9]

- Medicare Postpayment Claims Review (2015-07): Several types of Medicare contractors conduct postpayment claims reviews to help reduce improper payments. In 2014, we found that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) did not have reliable data and did not provide sufficient oversight and guidance to measure and fully prevent duplicative claims reviews among Medicare contractors.

- We recommended that CMS monitor the Recovery Audit Data Warehouse to ensure that all postpayment review contractors are submitting required data and that the data the database contains are accurate and complete. CMS took several steps between 2015 and 2017, including developing complete guidance to define contractors’ responsibilities regarding duplicative claims reviews, implementing a new process to monitor the data that contractors enter into the Recovery Audit Data Warehouse, and periodically verifying that contractors submit all required data to the Warehouse. As a result, CMS has helped ensure that Medicare contractors conduct efficient postpayment claims reviews and avoid inappropriate duplication.

- Use of the Do Not Pay Working System (2017-11): The Office of Management and Budget (OMB), in coordination with the Department of the Treasury (Treasury), developed the Do Not Pay working system as a data matching service for agencies to use in preventing improper payments. In 2016, we reported that the 10 agencies we reviewed used the working system in limited ways, in part because of a lack of clear OMB strategy and guidance.

- We recommended that the Director of OMB develop a strategy and clarifying guidance for how agencies should use the Do Not Pay working system to complement and streamline existing data matching processes. In June 2018, OMB issued a revised Circular A-123 Appendix C that discusses in detail how agencies should effectively use the working system and clarifies requirements about use of the working system’s payment integration functionality and how to obtain a waiver. It includes a section on streamlining existing data-matching processes, screening payees before a payment is made, assessing data quality, tailoring the results of matching to program requirements, and using analytics services to develop solutions for program-specific improper payment challenges. As a result of these actions, OMB’s revised appendix should help ensure that agencies use the Do Not Pay working system effectively, which could contribute to reductions in improper payments.

Action on Remaining and New Areas Could Yield Significant Additional Benefits

Congress and executive branch agencies have made progress toward addressing the 903 total actions we have identified since 2011. However, further steps are needed to fully address the 396 actions that are partially addressed, not addressed, or new.[10] We estimate that tens of billions of dollars in additional financial benefits could be realized should Congress and executive branch agencies fully address open actions, and other improvements can be achieved as well.[11]

Open Areas Directed to Congress and Executive Branch Agencies with Potential Financial Benefits

Congress has used our work to identify legislative solutions to achieve cost savings, address emerging problems, and find efficiencies in federal agencies and programs. Our work has contributed to a number of key authorizations and appropriations. In addition, congressional oversight of agencies’ efforts has been critical in realizing the full benefits of our suggested actions addressed to the executive branch, and it will continue to be critical.

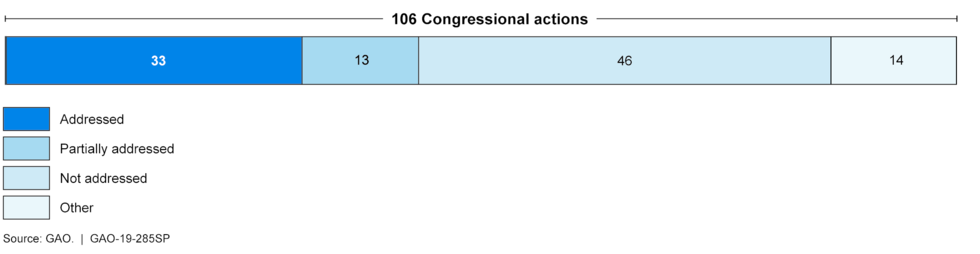

In our 2011 to 2019 annual reports, we directed 106 actions to Congress, including the six new congressional actions we identified in 2019. Of the 106 actions, 59 (56 percent) remained open as of March 2019. Appendix V has a full list of all open congressional actions.

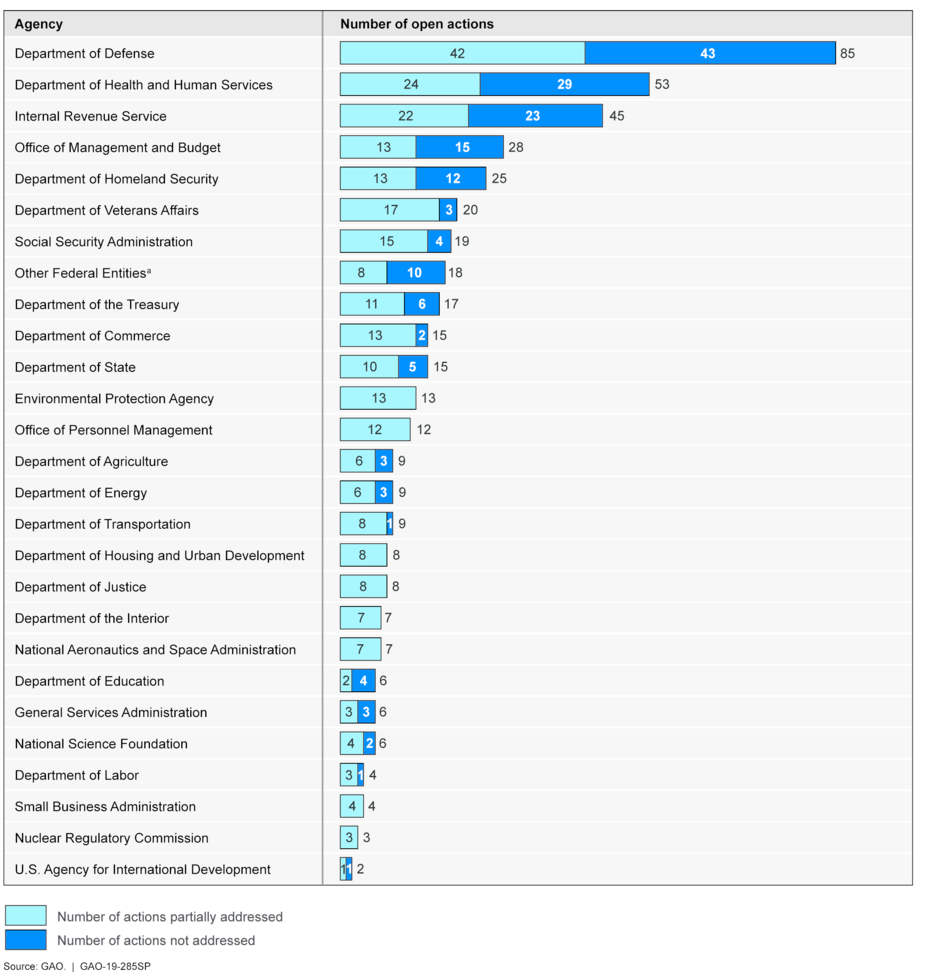

We also directed 797 actions to executive branch agencies, including 92 new actions identified in 2019. As shown in figure 3, these actions span the government and are directed to dozens of federal agencies. Five of these agencies, DOD, HHS, IRS, OMB, and DHS, have at least 25 open actions. Of the 797 actions, 337 (42 percent) remained open as of March 2019.

Figure 3: Number of Partially Addressed and Not Addressed Actions since 2011, by Agency

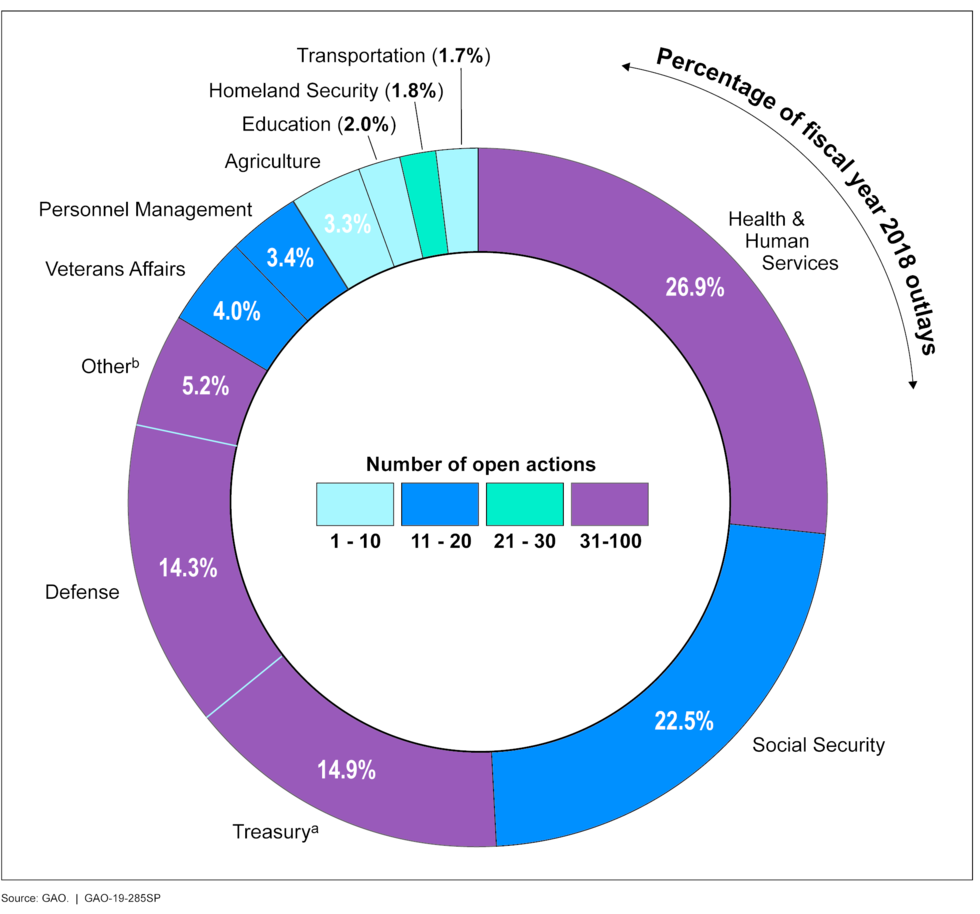

A significant number of open actions are directed to 10 agencies that made up about 95 percent of federal outlays in fiscal year 2018. Figure 4 highlights agencies with open actions as well as their fiscal year 2018 share of federal outlays.

Figure 4: Fiscal Year 2018 Outlays and Number of Open Actions since 2011, by Agency

We identified potential financial benefits associated with many open areas with actions directed to Congress and the executive branch. These benefits range from millions of dollars to tens of billions of dollars. For example, DOD could help achieve its initial cost savings target of $2 billion by managing its commissaries better, potentially saving millions of dollars. In another example, IRS could collect over a million dollars annually in additional tax revenues by clarifying whether transfers of unclaimed savings from employer-based plans to states are distributions and should be subject to tax withholding. Table 6 highlights examples of areas where additional action could potentially result in financial benefits of $1 billion or more.

| Area name and description (year-number links to Action Tracker) | Mission | Potential financial benefitsa (source) |

| *DOE’s Treatment of Hanford’s Low-Activity Waste (2018‑17): The Department of Energy (DOE) may be able to reduce certain risks by adopting alternative approaches to treating a portion of its low-activity radioactive waste. (GAO-17-306) | Energy | Tens of billions (GAO) |

| Defense Headquarters (2012‑34): The Department of Defense could review and identify further opportunities for consolidating or reducing the size of headquarters organizations. (GAO-12-345, GAO-13-293, GAO-14-439, GAO-15-10) | Defense | $9.4 billion (National Defense Authorization Act) |

| *Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program (2014‑13): Unless the Department of Energy can demonstrate demand for new Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing loans and viable applications, Congress may wish to consider rescinding all or part of the remaining credit subsidy appropriations. (GAO-14-343SP) | Energy | Up to $4.3 billion (DOE) |

| *Disability and Unemployment Benefits (2014‑08): Congress should consider passing legislation to prevent individuals from collecting both full Disability Insurance benefits and Unemployment Insurance benefits that cover the same period. (GAO-12-764) | Income security | $2.5 billion over 10 years (Office of Management and Budget) |

| *Social Security Offsets (2011‑80): The Social Security Administration (SSA) needs data on pensions from noncovered earnings to better enforce offsets and ensure benefit fairness, which could result in cost savings if enforced both retrospectively and prospectively, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and SSA. Congress could consider giving the Internal Revenue Service the authority to collect the necessary information. Estimated savings would be less if SSA only enforced the offsets prospectively as it would not reduce benefits already received. (GAO-05-786T) | Income security | $2.4 to $7.9 billion over 10 years (CBO and SSA) |

| *Crop Insurance (2013‑19): Congress could consider limiting the subsidy for premiums that an individual farmer can receive each year from the Federal Crop Insurance program, reducing the subsidy, or some combination of limiting and reducing these subsidies and making changes to the program to reduce its delivery costs. (GAO-17-501, GAO-12-256) | Agriculture | Up to $1.4 billion annually (GAO) |

| Medicare Clinical Laboratory Payments (2019‑25): The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should take steps to avoid paying more than necessary for clinical laboratory tests. (GAO-19-67) | Health | Over $1 billion, or billions (GAO) |

| *Medicare Payments by Place of Service (2016‑30): Medicare could have cost savings if Congress were to equalize the rates Medicare pays for certain health care services, which often vary depending on where the service is performed. (GAO-16-189) | Health | Billions annually (GAO) |

| Department of Energy Environmental Liability (2019‑20): DOE could develop a program-wide strategy to improve decision-making on cleaning up radioactive and hazardous waste. (GAO-19-28) | Energy | Billions (GAO) |

| *Identity Theft Refund Fraud (2016‑22): The Internal Revenue Service and Congress could improve the agency’s efforts to prevent refund fraud associated with identity theft. (GAO-18-418, GAO-16-508) | General government | Billions (GAO) |

| Tax Expenditures (2011‑17): Periodic reviews could help identify ineffective tax expenditures and redundancies in related tax and spending programs, potentially reducing revenue losses. (GAO-16-622, GAO-15-83) | General government | Billions (GAO) |

Note: All estimates of potential financial benefits are dependent on various factors, such as whether action is taken and how it is taken. Actual benefits may be less, depending on costs associated with implementing the action, unintended consequences, and the impact of other factors that could and should be controlled for. The individual estimates in this table should be compared with caution, as they come from a variety of sources, which consider different time periods and utilize different data sources, assumptions, and methodologies.

aGAO developed the notional estimates, which are intended to provide a sense of potential magnitude of financial benefits. Notional estimates have been developed using broad assumptions about potential benefits which are rooted in previously identified losses, the overall size of the program, previous experience with similar reforms, and similar rough indicators of potential benefits. GAO generally determines the notional label (“millions” vs. “tens of millions” vs. “hundreds of millions”) using a risk-based approach that takes into account such factors as the possible minimum and maximum values of the financial benefits estimate (where available), the quality of the data underlying those values, the certainty of those values, and/or the rigor of the estimation method used.

Open Areas with Other Benefits

Table 7 shows selected areas where Congress and executive branch agencies can take action to achieve other benefits, such as increased public safety, better homeland and national security, and more effective delivery of services.

| Area name and description (year-number links to Action Tracker) | Mission | Potential benefit |

| GPS Modernization (2018-03): The Department of Defense should assign a single organization responsibility for ensuring that common solutions for Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver card modernization efforts are collected and shared among hundreds of programs. (GAO-18-74) | Defense | Save time on GPS modernization and enable anti-jamming capabilities |

| Graduate Medical Education Funding (2018-05): The Department of Health and Human Services should coordinate with federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans Affairs, to improve the effectiveness and oversight of fragmented federal funding for physician graduate medical education, which cost the federal government $14.5 billion in 2015. (GAO-18-240) | Health | Better data quality for examining graduate medical education programs |

| Supplemental Security Income (2018-10): To better manage fragmentation in service delivery, the Social Security Administration should explore options for better connecting transition-age youth receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) to vocational rehabilitation services. (GAO-17-485) | Income security | Improved service delivery for SSI recipients |

| Military and Veterans Health Care (2012-15): The Departments of Defense (DOD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) need to improve integration across care coordination and case management programs to reduce duplication and better assist servicemembers, veterans, and their families. (GAO-12-129T) | Health | Better care from and management of DOD and VA healthcare programs |

| Biological Threats (2011-21): The Homeland Security Council could develop and implement strategic oversight mechanisms to help integrate fragmented interagency efforts to defend against biological threats. (GAO-11-318SP) | Homeland security/law enforcement | Ensure biodefense plans are cohesive, compatible, and mutually reinforcing |

| *Food Safety (2011-01): The Office of Management and Budget, relevant agencies, and Congress can address inconsistent oversight, ineffective coordination, and inefficient use of resources caused by the fragmented federal approach to food safety. (GAO-17-74, GAO-15-180) | Agriculture | Reduced fragmentation for federal food safety oversight efforts |

This report was prepared under the coordination of Jessica Lucas-Judy, Director, Strategic Issues, who may be reached at (202) 512-9110 or lucasjudyj@gao.gov, and J. Christopher Mihm, Managing Director, Strategic Issues, who may be reached at (202) 512-6806 or mihmj@gao.gov. Specific questions about individual issues may be directed to the area contact listed at the end of each summary.

Gene L. Dodaro

Comptroller General of the United States

Congressional Addressees

The Honorable Richard Shelby

Chairman

The Honorable Patrick Leahy

Vice Chairman

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Enzi

Chairman

The Honorable Bernie Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on the Budget

United States Senate

The Honorable Ron Johnson

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Nita Lowey

Chairwoman

The Honorable Kay Granger

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Yarmuth

Chairman

The Honorable Steve Womack

Ranking Member

Committee on the Budget

House of Representatives

The Honorable Elijah Cummings

Chairman

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mark Warner

United States Senate

Appendixes

IN THIS SECTION

- Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

- Appendix II: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Fragmentation, Overlap, or Duplication

- 1. Arsenic in Rice

- 2. Defense Agency Human Resources Services

- 3. DOD Document Services

- 4. Defense Health Care Reform

- 5. Federal Shared Services

- 6. Foreign Asset Reporting

- 7. IRS Strategic Workforce Planning

- 8. DOD Adverse Medical Events

- 9. Chemical Terrorism

- 10. Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans

- 11. Alignment of Foreign Assistance Strategies

- 12. Coordination of Overseas Stabilization Efforts

- 13. State’s Internal Communication Regarding Cuba Incidents

- 14. U.S. Security Assistance to the Caribbean

- 15. Federal Research

- 16. Patent Licensing at Federal Labs

- 17. SNAP Employment and Training

- Appendix III: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Other Cost Savings or Revenue Enhancement Opportunities

- 18. DOD Installation Support Services

- 19. Foreign Military Sales Administrative Account

- 20. Department of Energy Environmental Liability

- 21. Disaster Response Contracting

- 22. Inland Waterways Construction

- 23. Tax Treatment of 401(k) Transfers

- 24. Medicaid Spending Oversight

- 25. Medicare Clinical Laboratory Payments

- 26. Prior Authorization in Medicare

- 27. Coast Guard Shore Infrastructure

- 28. Federal Student Loan Default Rates

- Appendix IV: New Actions Added to Existing Areas in 2019

- Appendix V: Open Congressional Actions, by Mission

- Appendix VI: Additional Information on Programs Identified

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

Section 21 of Public Law 111-139, enacted in February 2010, requires us to conduct routine investigations to identify federal programs, agencies, offices, and initiatives with duplicative goals and activities within departments and government-wide.[12] This provision also requires us to report annually to Congress on our findings, including the cost of such duplication, with recommendations for consolidation and elimination to reduce duplication and specific rescissions (legislation canceling previously enacted budget authority) that Congress may wish to consider. Our objectives in this report are to (1) identify potentially significant areas of fragmentation, overlap, and duplication and opportunities for cost savings and enhanced revenues that exist across the federal government; (2) assess to what extent have Congress and executive branch agencies addressed actions in our 2011 to 2018 annual reports; and (3) highlight examples of open actions directed to Congress or key executive branch agencies.

For the purposes of our analysis, we used the term “fragmentation” to refer to circumstances in which more than one federal agency (or more than one organization within an agency) is involved in the same broad area of national need and there may be opportunities to improve how the government delivers these services. We used the term “overlap” when multiple agencies or programs have similar goals, engage in similar activities or strategies to achieve them, or target similar beneficiaries. We considered “duplication” to occur when two or more agencies or programs are engaged in the same activities or provide the same services to the same beneficiaries.[13]

This report presents 17 new areas of fragmentation, overlap, or duplication where greater efficiencies or effectiveness in providing government services may be achievable. The report also highlights 11 other new opportunities for potential cost savings or revenue enhancements.

To identify what actions, if any, exist to address fragmentation, overlap, and duplication and take advantage of opportunities for cost savings and enhanced revenues, we reviewed and updated our prior work and recommendations to identify what additional actions Congress may wish to consider and agencies may need to take. For example, we used our prior work identifying leading practices that could help agencies address challenges associated with interagency coordination and collaboration and with evaluating performance and results in achieving efficiencies.[14]

To identify the potential financial and other benefits that might result from actions addressing fragmentation, overlap, or duplication, or taking advantage of other opportunities for cost savings and enhanced revenues, we collected and analyzed data on costs and potential savings to the extent they were available. Estimating the benefits that could result from addressing these actions was not possible in some cases because information about the extent and impact of fragmentation, overlap, and duplication among certain programs was not available. Further, the financial benefits that can be achieved from addressing fragmentation, overlap, or duplication or taking advantage of other opportunities for cost savings and enhanced revenues were not always quantifiable in advance of congressional and executive branch decision-making. In addition, the needed information was not readily available on, among other things, program performance, the level of funding devoted to duplicative programs, or the implementation costs and time frames that might be associated with program consolidations or terminations.

Appendix VI provides additional information on the federal programs or other activities related to the new areas of fragmentation, overlap, duplication, and cost savings or revenue enhancement discussed in this report, including budgetary information when available.

We assessed the reliability of any computer-processed data that materially affected our findings, including cost savings and revenue enhancement estimates. The steps that we take to assess the reliability of data vary but are chosen to accomplish the auditing requirement that the data be sufficiently reliable given the purposes for which it is used in our products. We review published documentation about the data system and inspector general or other reviews of the data. We may interview agency or outside officials to better understand system controls and to assure ourselves that we understand how the data are produced and any limitations associated with the data. We may also electronically test the data to see whether values in the data conform to agency testimony and documentation regarding valid values, or we may compare data to source documents. In addition to these steps, we often compare data with other sources as a way to corroborate our findings. For each new area in this report, specific information on data reliability is located in the related products.

We provided drafts of our new area summaries to the relevant agencies for their review and incorporated these comments as appropriate.

Assessing the Status of Previously Identified Actions

To examine the extent to which Congress and executive branch agencies have made progress in implementing the 805 actions in the approximately 300 areas we have reported on in previous annual reports on fragmentation, overlap, and duplication, we reviewed relevant legislation and agency documents such as budgets, policies, strategic and implementation plans, guidance, and other information between April 2018 and March 2019. We also analyzed, to the extent possible, whether financial or other benefits have been attained, and included this information as appropriate. (See discussion below on the methodology we used to estimate financial benefits.) In addition, we discussed the implementation status of the actions with officials at the relevant agencies. Throughout this report, we present our counts as of March 2019 because that is when we received our last updates. The progress statements and updates are published on GAO’s Action Tracker.

We used the following criteria in assessing the status of actions:

- In assessing actions suggested for Congress, we applied the following criteria: “addressed” means relevant legislation has been enacted and addresses all aspects of the action needed; “partially addressed” means a relevant bill has passed a committee, the House of Representatives, or the Senate during the current congressional session, or relevant legislation has been enacted but only addressed part of the action needed; and “not addressed” means a bill may have been introduced but did not pass out of a committee, or no relevant legislation has been introduced. Actions suggested for Congress may also move to “addressed” or “partially addressed” with or without relevant legislation if an executive branch agency takes steps that address all or part of the action needed. At the beginning of a new congressional session, we reapply the criteria. As a result, the status of an action may move from partially addressed to not addressed if relevant legislation is not reintroduced from the prior congressional session.

- In assessing actions suggested for the executive branch, we applied the following criteria: “addressed” means implementation of the action needed has been completed; “partially addressed” means the action needed is in development or started but not yet completed; and “not addressed” means the administration, the agencies, or both have made minimal or no progress toward implementing the action needed.

Since 2011, we have categorized 69 actions as “other” and are no longer assessing these actions. We categorized 42 “other” actions as “consolidated or other.” In most cases, “consolidated or other” actions were replaced or subsumed by new actions based on additional audit work or other relevant information. We also categorized 27 of the “other” actions as “closed-not addressed.” Actions are generally “closed-not addressed” when the action is no longer relevant because of changing circumstances.

Methodology for Generating Total Financial Benefits Estimates

In order to calculate the total financial benefits resulting from actions already taken (addressed or partially addressed) and potential financial benefits from actions that are not fully addressed, we compiled available estimates for all of the actions from GAO’s Action Tracker, from 2011 through 2018, and from reports identified for inclusion in the 2019 annual report, and linked supporting documentation to those estimates. Each estimate was reviewed by one of our technical specialists to ensure that estimates were based on reasonably sound methodologies. The financial benefits estimates came from a variety of sources, including our analysis, Congressional Budget Office estimates, individual agencies, the Joint Committee on Taxation, and others. Because of differences in time frames, underlying assumptions, quality of data and methodologies among these individual estimates, any attempt to generate a total will be associated with uncertainty that limits the precision of this calculation. As a result, our totals represent a rough estimate of financial benefits, rather than an exact total.

For actions that have already been taken, individual estimates of realized financial benefits covered a range of time periods stretching from 2010 through 2025. In order to calculate the total amount of realized financial benefits that have already accrued and those that are expected to accrue, we separated those that accrued from 2010 through 2018 and those expected to accrue between 2019 and 2025. For individual estimates that span both periods, we assumed that financial benefits were distributed evenly over the period of the estimate.[15] For each category, we summed the individual estimates in order to generate a total. To account for uncertainty and imprecision resulting from the differences in individual estimates, we present these realized savings to the nearest billion dollars, rounded down.

There is a higher level of uncertainty for estimates of potential financial benefits that could accrue from actions not yet taken because these estimates are dependent on whether, how, and when agencies and Congress take our recommended actions. As a result, many estimates of potential savings are notionally stated using terms like millions, tens of millions, or billions, to demonstrate a magnitude without providing a more precise estimate.

Further, many of these estimates are not tied to specific time frames for the same reason. In order to calculate a total for potential savings, with a conservative approach, we used the minimum number associated with each term.[16] To account for the increased uncertainty of potential estimates and the imprecision resulting from differences among individual estimates, we calculated potential financial benefits to the nearest $10 billion, rounded down, and presented our results using a notional term.

This report is based upon work GAO previously conducted in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Generally accepted government auditing standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Fragmentation, Overlap, or Duplication

This appendix presents 17 new areas in which we found evidence of fragmentation, overlap, or duplication among federal government programs.

1. Arsenic in Rice

To avoid unnecessary and potentially inefficient duplicative efforts, the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture should improve coordination of their efforts to develop methods for detecting contaminants in food, including arsenic in rice.

| Quick Look Potential Benefit Improved management of resources Implementing Entity Food and Drug Administration and U.S. Department of Agriculture Link to Actions GAO identified one action each for FDA and USDA to improve coordination on methods to detect contaminants in food. See GAO’s Action Tracker. Related GAO Product Contact Information Steve Morris at (202) 512-3841 or morriss@gao.gov |

Arsenic, an element in the earth’s crust, can be harmful to human health and may be present in water and certain foods. The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) work to address food safety risks. FDA’s responsibilities for rice include regulatory and research programs; USDA’s include research programs.

In March 2018, GAO found that FDA and USDA’s Federal Grain Inspection Service (FGIS) and Agricultural Research Service (ARS) coordinated on the development of detection methods for arsenic in rice to a limited extent. Officials from FDA and FGIS told GAO that they began to coordinate in March 2016, when they discovered they were each working independently to adapt a digital test kit used for detecting arsenic in drinking water so that it can be used to detect arsenic in rice. FGIS suspended work on the effort after about nine months. ARS researched a different method to detect arsenic in rice, and ARS did not coordinate with FDA to develop this method because, according to ARS officials, the agencies are trying to meet different needs with their research.

The strategic plans of FDA and of USDA’s ARS and FGIS show a shared interest in developing detection methods for foodborne contaminants, including arsenic in rice. However, neither FDA nor USDA has a mechanism to coordinate this work. Instead, according to FDA and USDA officials, they coordinate on an informal basis.

GAO has shown in prior work that many of the meaningful results that the federal government seeks to achieve, such as those related to protecting food and agriculture, require the coordinated efforts of more than one federal agency. Because of risks to the economy and to public health and safety, GAO has identified transforming federal oversight of food safety as a high-risk area. GAO has also noted in prior work that interagency mechanisms to coordinate programs that address crosscutting issues may reduce potentially inefficient duplicative efforts.

GAO recommended in 2018 that FDA and USDA develop a mechanism to coordinate the development of methods to detect contaminants in food, including arsenic in rice. In its comments, HHS generally agreed with the recommendation and stated that FDA agreed that such a mechanism would be worthwhile. USDA also generally agreed with the recommendation and stated that the USDA Office of the Chief Scientist will facilitate this effort.

Better coordinating methods to detect contaminants in food, including arsenic in rice, could help FDA and USDA better manage their resources and avoid engaging in unnecessary and potentially inefficient duplicative efforts. During the course of the engagement, GAO found that FDA and USDA avoided duplicating their efforts to develop detection methods for arsenic in rice through informal discussions once their research efforts were underway. However, FDA and USDA do not proactively plan their shared research interest in developing such methods; therefore, the potential exists for engaging in potentially inefficient duplicative efforts in the future. Because the risk of duplication—and potential inefficiencies—is dependent on the specifics of future projects, GAO cannot develop an estimate of savings that would result from taking this action.

Table 21 in appendix VI provides additional program information related to this issue area.

Agency Comments and GAO’s Evaluation

GAO provided a draft of this report to HHS and USDA for review and comment. HHS had no comments. USDA noted, among other actions, that ARS would discuss common research needs with FDA and FGIS at the beginning of the 2021-2025 ARS food safety research program cycle. Such action may be responsive to GAO’s recommendation if it includes discussions about the development of methods to detect contaminants in food. GAO will continue to monitor USDA’s and FDA’s activities to determine whether the planned discussions lead to improved coordination in this area.

Related GAO Product

Food Safety: Federal Efforts to Manage the Risk of Arsenic in Rice. GAO-18-199. Washington, D.C.: March 16, 2018.

2. Defense Agency Human Resources Services

The Department of Defense should address fragmentation and overlap among providers of human resources services to increase effectiveness and efficiency and potentially save millions of dollars.

| Quick Look Potential Benefit Millions of dollars and more effective and efficient delivery of human resources services Implementing Entity Department of Defense Link to Actions GAO identified three actions to DOD to address inefficiencies related to human resources services provided by defense agencies. See GAO’s Action Tracker. Related GAO Product Contact Information Elizabeth Field at (202) 512-2775 or fielde1@gao.gov |

The Department of Defense (DOD) relies on six providers for human resources (HR) services—three military departments, the Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS), the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), and the Washington Headquarters Service (WHS). These providers develop vacancy announcements, screen potential candidates, and process personnel actions, among many other services.

In September 2018, GAO found that these entities provided fragmented and overlapping services to customers. For example, DOD officials reported that all six provide some similar HR services to personnel employed by one customer, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency, depending on the location, rank, or other characteristics of the staff.

GAO identified negative effects of these issues. First, defense organizations that use more than one HR services provider pay overhead costs for each provider, resulting in unnecessary expenses and inefficiencies. Second, DOD officials stated that over 800 fragmented learning management information technology (IT) systems store and record training records across the department, which are costly to maintain. Third, the HR services providers use inconsistent performance information regarding hiring, thereby limiting DOD’s ability to assess what changes, if any, need to be made to hiring practices. Specifically, DFAS, DLA, and WHS differed in how they measure and report performance data, such as time-to-hire measures, which limits customers’ ability to make informed choices about selecting a HR services provider.

In January 2018, DOD established the Human Resources Management Reform Team to initiate key reform efforts within the department. According to the team’s charter, the team will work to modify HR processes and move toward enterprise service delivery of HR services, which DOD expects to reduce costs. Team members said they would initially focus on high-priority challenges, such as pursuing the optimal IT systems, such as learning management systems, for DOD HR services department-wide and identifying legislative and regulatory changes needed to streamline processes and procedures.

After making progress in these areas, the team plans to review service delivery across the department and determine the most effective and efficient system. However, GAO identified limitations in how the team was planning and managing its work. Specifically, the reform team had not required the use of consistent performance measures and had not set clear time frames for some of its work. Further, the reform team lacked key pieces of information, such as data on overhead costs.

GAO recommended that DOD (1) collect information on the overhead costs charged by all DOD HR services providers, (2) identify time frames and deliverables for adopting optimal IT solutions for HR and implementing the most effective and efficient means of HR service delivery, and (3) require that all DOD HR providers adopt consistent time-to-hire measures. DOD concurred, stating that the department is on track to achieve substantial savings through its reform team efforts.

Addressing these issues could help DOD provide a more effective, economical, and efficient HR service delivery model. DOD could not provide a cost savings estimate for learning management system reform or a comprehensive list of related IT systems. GAO identified 100 IT systems that DOD could consider. The total cost of these systems in fiscal year 2017 exceeded $300 million, and about half of the systems cost over $1 million. By eliminating even one of these more costly systems, DOD could reasonably be expected to save $1 million or more, depending on DOD’s analysis and subsequent actions.

Table 22 in appendix VI provides additional program information related to this issue area.

Agency Comments and GAO’s Evaluation

GAO provided a draft of this report section to DOD for review and comment. DOD officials stated that the department would continue to review the most effective and efficient means of HR service delivery. DOD officials also provided GAO an update on these recommendations, including estimated milestones through fiscal year 2020.

Related GAO Product

Defense Management: DOD Needs to Address Inefficiencies and Implement Reform across Its Defense Agencies and DOD Field Activities. GAO-18-592. Washington, D.C.: September 6, 2018

3. DOD Document Services

The Department of Defense should take actions to better manage fragmentation in its document services functions to potentially save millions of dollars annually.

| Quick Look Potential Benefit Millions of dollars annually Implementing Entity Department of Defense Link to Actions GAO identified five actions to address fragmentation and overlap. See GAO’s Action Tracker. Related GAO Product Contact Information Elizabeth Field at (202) 512-2775 or fielde1@gao.gov |

During fiscal years 2010 through 2015, the Department of Defense (DOD) reported spending an annual average of $608 million on document services, which include printing, copying, and related activities. Multiple DOD components have a role in providing document services. The Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) is DOD’s single manager for printing and high-speed, high-volume duplicating and the preferred provider for document conversion and automation services. Other components, including the military services, also maintain some of these capabilities.

In October 2018, GAO found that DOD had taken some steps to achieve efficiencies in its document services, but identified four areas where gains may be possible. First, DOD customers were obtaining printing and duplicating services from DLA, as required by DOD policy, but were also obtaining services directly from the Government Publishing Office and from in-house print facilities, citing concerns about DLA’s quality, cost, and timeliness. DOD had not assessed whether DLA’s single manager role was the most effective and efficient model for providing the services.

Second, DOD had not developed a department-wide approach to acquiring print devices, and DOD components used at least four different contract sources to acquire print devices, with costs that varied widely for similar devices. GAO analyzed a selection of standard print device pricing and vendor quotes for similar devices across the contracts and found that consolidating procurements of print devices could potentially reduce DOD’s costs. However, DOD had not assessed which acquisition approach represented the best value.

Third, DOD could not demonstrate that it had achieved its goals for reducing the number of print devices, which it had estimated would result in savings of millions of dollars annually. DOD lacked adequate internal controls, such as reporting procedures, and it did not assign responsibility for monitoring the department’s progress in meeting these goals.

Fourth, DOD may be able to realize additional savings from further consolidating DLA facilities beyond those already identified, but DLA did not have the complete data it would need to do so. As of October 2018, DLA planned to close 74 of 112 printing facilities in the United States. DLA generally consolidated or retained facilities based on whether they provided mission specialty services that could not be easily outsourced. GAO analysis found that DLA planned to retain facilities that were responsible for less than 5 percent of the total revenue for certain types of mission specialties, which suggests that further consolidations may be possible. GAO also found that DLA did not have revenue data on all of its mission specialties to inform any future consolidation decisions.

GAO made five recommendations, including that DOD assess whether DLA’s single manager role for printing and duplication services and its current approach to obtaining print devices provides the best value; implement controls and assign responsibility to monitor actions to reduce the number of print devices; and evaluate opportunities to further consolidate DLA facilities. DOD concurred with the recommendations and identified specific actions to address them.

DOD could potentially achieve cost savings and gain other efficiencies by implementing GAO’s recommendations, which would help manage fragmentation in its document services. For example, DOD estimated that reducing the number of its print devices would save millions of dollars annually. Implementing additional controls and assigning oversight responsibilities to monitor progress on reducing the number of print devices would better enable DOD to achieve its cost savings goals.

Table 23 in appendix VI provides additional program information related to this issue area.

Agency Comments and GAO’s Evaluation

GAO provided a draft of this report section to DOD for review and comment. DOD agreed with the accuracy of the information presented in this section. DOD also provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate.

Related GAO Product

Document Services: DOD Should Take Actions to Achieve Further Efficiencies. GAO-19-71. Washington, D.C.: October 11, 2018.

4. Defense Health Care Reform

The Department of Defense could potentially save millions of dollars by resolving weaknesses in its planning efforts to reform the administration of military treatment facilities.

| Quick Look Potential Benefit Millions of dollars Implementing Entity Department of Defense Link to Actions GAO identified three actions to reduce or better manage duplicative functions and improve efficiencies in the administration of the military treatment facilities. See GAO’s Action Tracker. Related GAO Product Contact Information Brenda S. Farrell at (202) 512-3604 or farrellb@gao.gov |

In fiscal year 2017, the Department of Defense (DOD) provided health care to 9.4 million beneficiaries, including servicemembers, retirees, and their families. In September 2013, DOD established the Defense Health Agency (DHA) to create a more integrated Military Health System and achieve cost savings at headquarters-level organizations. These organizations have responsibilities that generally involve oversight, direction, and control of subordinate organizations or other units. According to DOD, there are approximately 679 military treatment facilities (MTFs) including military hospitals, ambulatory care clinics, and dental clinics.

In fiscal year 2017, Congress directed that the administrative responsibility for the MTFs transfer from the military departments to the Director of the DHA. This transfer will include management responsibilities, among other things, and shall be completed no later than September 30, 2021. Congress also directed that the Secretary of Defense develop an implementation plan for the transfer of administration of the MTFs that includes certain elements, such as DOD’s efforts to eliminate duplicative activities and reduce headquarters-level military, civilian, and contractor personnel of the headquarters activities within the Military Health System.

In October 2018, GAO found that DOD excluded 16 operational readiness and installation-specific medical functions, including dental care and substance abuse programs, from the planned transfer to DHA. DOD did not provide any analysis or documentation regarding the decision to exclude these 16 functions. However, senior-level officials from the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs and DHA acknowledged that transferring the dental care function, for example, from the military departments to DHA could potentially reduce duplicative activities and result in more efficiencies.

DOD also has not conducted a comprehensive review to validate headquarters-level personnel requirements needed to accomplish its mission and performance objectives, including the least costly mix of personnel (i.e., military, civilian, and contract). DOD policy states that personnel requirements are driven by workload and shall be established at the minimum levels necessary to accomplish mission and performance objectives.

GAO recommended that DOD (1) define and analyze the 16 operational readiness and installation-specific medical functions not included in the planned transfer to the DHA for duplication; (2) validate headquarters-level personnel requirements; and (3) identify the least costly mix of personnel. DOD concurred and stated it was assessing the 16 functions previously identified for exclusion from transfer to DHA and personnel requirements, including an extensive review of the personnel requirements for the management structure of the DHA. In March 2019, DOD officials stated that DOD continues to take action to address GAO’s recommendations, to include implementing congressional direction to address specific medical functions and addressing personnel requirements and mix. However, as GAO previously stated in the report, DOD needs to identify the least costly mix of military, civilian, and contractors once it has validated requirements for DHA. GAO will continue to monitor DOD’s progress for addressing these recommendations.

Taking these actions should help DOD and congressional decision makers understand how this significant reform effort will improve effectiveness and efficiency in the administration of the MTFs. Taking these actions could also potentially achieve millions of dollars in savings. For example, GAO calculated that for one of the functions not being considered, a savings of even 1 percent could amount to millions of dollars in savings in the administration of the MTFs.

Table 24 in appendix VI provides additional program and budgetary information related to this issue area.

Agency Comments and GAO’s Evaluation

GAO provided a draft of this report section to DOD for review and comment. DOD officials provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate.

Related GAO Product

Defense Health Care: DOD Should Demonstrate How Its Plan to Transfer the Administration of Military Treatment Facilities Will Improve Efficiency. GAO-19-53. Washington, D.C.: October 30, 2018.

5. Federal Shared Services

The Office of Management and Budget and the General Services Administration could better position themselves to achieve their cost savings goal of $2 billion over 10 years and reduce inefficient overlap and duplication by strengthening their implementation of selected federal shared services reform efforts.

| Quick Look Potential Benefit Reduce duplicative efforts, cut costs, and modernize aging IT systems Implementing Entity Office of Management and Budget Link to Actions GAO identified four actions to improve OMB implementation of shared services initiatives with GSA. See GAO’s Action Tracker. Related GAO Product Contact Information Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen at (202) 512-2660 or nguyentt@gao.gov |

The federal government can reduce duplicative efforts and free up resources for mission-critical activities by consolidating mission-support services that multiple agencies need—such as payroll or travel—with a smaller number of providers so they can be shared among agencies.

According to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the federal government spends more than $25 billion annually on core mission-support services that are common across agencies, such as human resources (HR) and financial management. OMB and the General Services Administration (GSA) are responsible for overseeing a strategic, government-wide framework for improving the effectiveness and efficiency of shared services. The Office of Personnel Management estimated that implementation of shared services for HR, including payroll, resulted in more than $1 billion in government-wide cost savings and cost avoidance between fiscal years 2002 and 2015. However, these results have not been consistent across shared services migration efforts, according to OMB and others who have observed these migrations.

In 2018, OMB and GSA introduced a new marketplace model meant to better meet the needs of customers and service providers by offering more choices for purchasing shared services. In March 2019, GAO identified weaknesses with the implementation of the new marketplace that may limit its success. For example, OMB and GSA designed a payroll initiative called NewPay to determine how well the new marketplace model works. However, GAO found that they do not have a plan to monitor NewPay’s implementation. OMB and GSA also did not identify or document some key roles and responsibilities. A monitoring plan which includes performance goals and milestones and a process for documenting key roles could help OMB and GSA avoid gaps in service or costly delays as agencies transition to the new model for obtaining shared services.

GAO also found that OMB and GSA have not updated provider information for prospective customers on available shared services, pricing, and performance. Without up-to-date information on providers, it will be time consuming and difficult for potential customers to compare providers. Finally, GAO found that OMB and GSA set a cost-savings goal of $2 billion over 10 years based on reforms to the shared services governance structure and marketplace for federal agencies. However, they do not have a process for collecting and tracking data to assess their progress toward that goal. This information is necessary for OMB and GSA to determine progress and help identify areas for improvement.

GAO recommended that OMB’s Shared Services Policy Officer should work with GSA to (1) finalize a monitoring plan for the implementation of NewPay, (2) document key decision-making roles and responsibilities, (3) develop a process to provide information to customers on services, pricing, and performance to help minimize the challenges of transitioning to shared services on key stakeholders, and (4) implement a process for collecting and tracking cost-savings data that would allow them to assess progress toward their cost-savings goal. As of March 2019, OMB staff did not comment on GAO’s recommendations, but noted that OMB may update its shared services policy in the future.

Taking these steps should help OMB and GSA strengthen their approach to implementing shared services reform so that they are better positioned to achieve cost savings and reduce inefficient overlap and duplication.

Table 25 in appendix VI provides additional program and budgetary information related to this issue area.

Agency Comments and GAO’s Evaluation