Highlights

What GAO Found

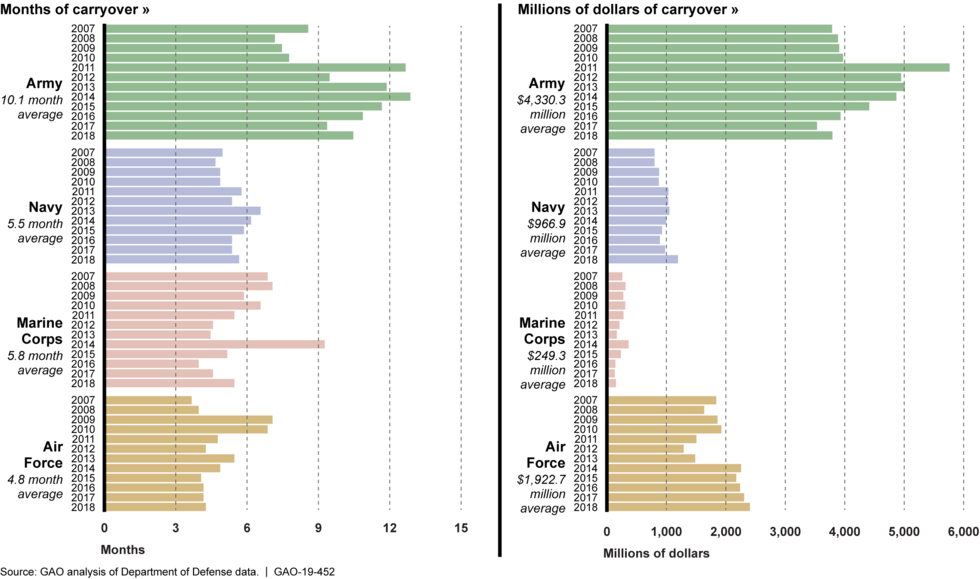

Each year, billions of dollars of work is ordered from maintenance depots that cannot be completed by the end of the fiscal year. The Department of Defense (DOD) refers to this funded but unfinished work as carryover. For fiscal years 2007 through 2018, the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force depots averaged less than 6 months of annual carryover worth $1.0 billion, $0.2 billion, and $1.9 billion, respectively. The Army depots averaged 10 months of annual carryover worth $4.3 billion. Reasons for unplanned carryover include issues with parts management, scope of work, and changing customer requirements.

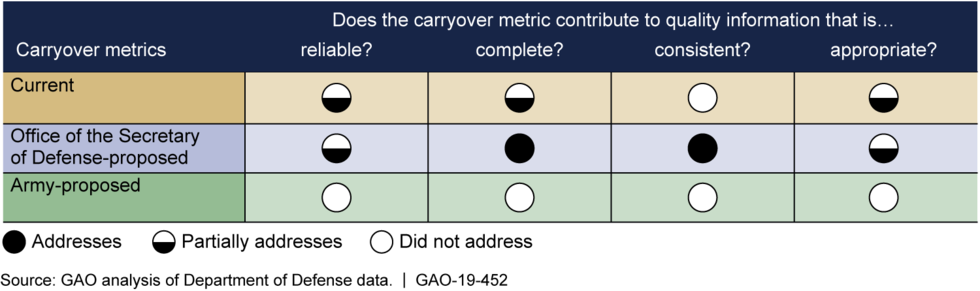

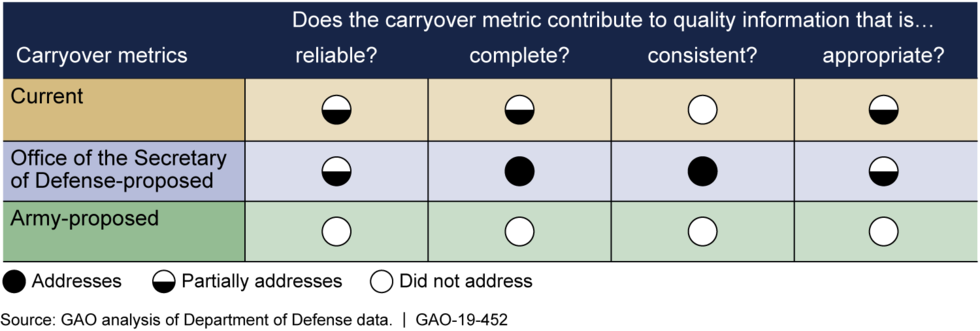

DOD identified three metrics for calculating allowable carryover in its report to Congress. However, the three metrics identified do not fully meet all key attributes—reliability, completeness, consistency, and appropriateness—for providing quality information to decision makers, although the Office of the Secretary of Defense-proposed carryover metric meets the most attributes.

Assessment of Carryover Metrics Identified by the Department of Defense

The three metrics are based on different calculations and would have different implications for depot maintenance management. Specifically,

-

The current carryover metric allows for exemptions worth tens of millions of dollars that reduce incentives to improve the effectiveness of depot management.

-

The Office of the Secretary of Defense-proposed metric could provide incentives to improve workload planning and the effectiveness of depot management, but uses a ratio instead of dollars to measure carryover.

-

The Army-proposed carryover metric is based on labor used to complete depot work, does not include depot maintenance costs such as parts, and carryover amounts are unlikely to exceed the ceiling. This metric is not likely to provide an incentive to improve depot management.

Unless DOD develops and adopts a carryover metric for depots that meets the key attributes of quality information, decisionmakers may not be able to help ensure funds are directed to the highest priority and depots are managed as effectively as possible.

Officials of private industry companies and foreign militaries GAO met with stated they do not have a policy to limit carryover. According to private sector officials, there is no incentive to limit workload if customers’ needs can be met within the terms of the contract and the work is likely to be profitable. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization and seven foreign militaries GAO interviewed generally use contractors, not depots, to meet most of their depot maintenance requirements and they do not have a carryover policy similar to DOD's.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD allows carryover from one fiscal year to the next to ensure the smooth flow of maintenance work performed at depots. DOD has reported that approximately 6 months of carryover is optimal. Excess carryover (i.e., more unfinished work than allowed) may reflect an inefficient use of resources and tie up funds that could be used for other priorities. Congress directed DOD to report on its current DOD carryover metric and consider alternatives. DOD’s report discussed three carryover metrics: the current DOD carryover metric, an Office of the Secretary of Defense-proposed carryover metric, and an Army-proposed carryover metric.

Congress asked GAO to review DOD’s historical carryover and the metrics presented by DOD. This report, among other things, (1) describes the total carryover for fiscal years 2007 through 2018, and the reasons for it; (2) evaluates the carryover metrics DOD presented in its report to Congress and whether they would provide quality information; and (3) describes private industry and foreign military policies for determining allowable carryover, if any. GAO reviewed DOD budget submissions to identify depot carryover and prior GAO reports to identify reasons for carryover; evaluated carryover metrics against criteria for quality information; and discussed carryover with DOD, private industry, and foreign military officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that DOD develop and adopt a carryover metric for depot maintenance that provides reliable, complete, consistent, and appropriate information. DOD concurred with the recommendation.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Executive Action

| Number | Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Defense | The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Undersecretary of Defense (Acquisition and Sustainment) develop and adopt a depot maintenance carryover metric that provides reliable, complete, consistent, and appropriate information. (Recommendation 1) |

Introduction

The Department of Defense (DOD) operates depots to maintain complex weapons systems and equipment through overhauls, upgrades, and rebuilding.[1] Each fiscal year, the military services order billions of dollars of depot maintenance work, some of which cannot be completed by the depots before the fiscal year ends.[2] DOD allows funded unfinished work at depots to be completed in the next fiscal year and refers to the unfinished work as carryover.[3] Carryover is measured as the dollar value of work ordered and funded by customers, but not completed at the end of a fiscal year.[4] Carryover can also be expressed as the amount of time (e.g., months) needed to complete this work. Some amount of carryover is appropriate to facilitate a smooth flow of work during the transition from one fiscal year to the next.[5] However, excessive carryover may reflect an inefficient use of resources and may tie up funds appropriated by Congress that could be used for other priorities.

House Report 115-200 accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 expressed concerns that DOD’s calculation of allowable carryover has indirectly affected military readiness and the ability of the depots to sustain core workload.[6] The House Committee on Armed Services directed the Secretary of Defense to submit a report providing information on the existing carryover calculation,and recommendations for modifying the current carryover metric, among other issues.[7] In response, DOD issued a report to Congress in April 2018 that explained DOD’s current carryover metric and an alternative metric proposed by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD).[8] The Army did not concur with the proposed new metric and developed its own proposed metric, which was discussed in DOD’s report. According to the DOD report to Congress, the Army’s position was fully considered but not adopted and unless Congress objects, DOD plans to implement the OSD-proposed carryover metric for future budget cycles.

You asked us to review DOD’s historical carryover and the metrics presented by DOD. This report (1) describes carryover for fiscal years 2007 through 2018, and the reasons for it; (2) evaluates the carryover metric options DOD considered, whether they address the attributes of quality information, and the implications associated with each option; and (3) describes private industry and foreign military policies for determining allowable carryover, if any.

To address the first objective, we compiled information from DOD budget submissions and our prior reports. We reviewed fiscal years 2007 through 2017, and added information for fiscal year 2018, which became available during the course of our review. We included in our scope the 21 depots that are managed with working capital funds[9] and are subjected to carryover calculations guidance.[10] Working capital funds allow depots to function in a business-like capacity generating sufficient revenue to cover the full cost of operations on a break-even basis over time- that is, neither make a gain nor incur a loss. We did not include the U.S. Naval Shipyards which are generally not managed with working capital funds, but are managed through direct funding.[11] To determine carryover for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 we reviewed Army, Navy, and Air Force Working Capital Fund budget submissions to identify military service depot carryover and revenue for this time period, and converted reported carryover amounts into months of carryover for each military service to present comparable data.[12] We assessed the reliability of the data by (1) interviewing Army, Navy, and Air Force officials to gain their opinions on the quality and accuracy of the data presented in the Army, Navy, and Air Force Working Capital Fund budgets,[13] and (2) reviewing our prior work to determine if there were reported concerns with Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps budgetary data.[14] We determined these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. We also analyzed our prior reports to determine the reasons for carryover, and we discussed the reasons with military service officials to determine whether these continue to be reasons for carryover or if any new reasons exist that were not identified in our prior reports. We did not conduct additional analysis beyond these interviews to identify reasons for carryover in the fiscal years since issuance of our prior reports.

To address the second objective, we reviewed documents related to DOD’s current metric, the OSD-proposed metric, and the Army-proposed metric and determined how the calculations are performed using each proposed metric. We applied the metrics to budget data presented for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 to support comparison of results using historic data. Additionally, we interviewed agency officials and reviewed the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government,[15] our prior reports related to measuring and managing DOD performance,[16] and DOD’s report to Congress on carryover. Based on these documents and interviews, we identified four attributes of quality information related to carryover (i.e., reliable, complete, consistent, and appropriate). We confirmed the appropriateness of these attributes for evaluating the carryover measure with DOD officials. We then compared these attributes to the current and proposed carryover metrics. Multiple analysts independently assessed the extent to which each metric incorporates the attributes and verified the results.

To address the third objective, we interviewed officials from nine private industry companies and officials from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and seven foreign militaries, and reviewed related documents.[17] We selected companies that performed work we deemed to be similar to work performed at depots. We selected foreign militaries that maintain weapon systems similar to those used by DOD, and that have diplomatic ties to the United States. Our findings from our interviews with companies and foreign militaries cannot be generalized, but do provide illustrative examples about how they handle allowable carryover. For more detail regarding our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2018 through July 2019 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Purpose of Depots

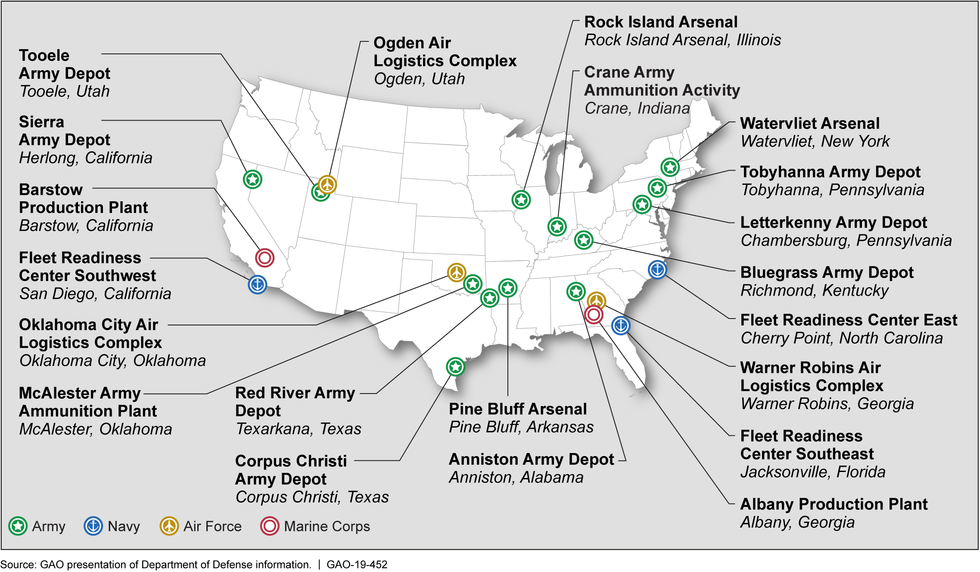

DOD uses government-owned and government-operated depots to perform key roles in sustaining complex weapon systems and equipment.[18] Depots are required to maintain surge capacity, support readiness requirements, and are essential to ensure effective and timely responses to mobilization, national defense contingency situations, and other emergency requirements. With the exception of the Naval shipyards, depot activities are managed through working capital funds.[19] Working capital funds facilitate the business-like operation of depots that generates sufficient revenue to cover the full cost of operations on a break-even basis over time-that is, neither make a gain nor incur a loss. The 21 depots managed with working capital funds and which calculate allowable carryover are depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1: Department of Defense Depot Maintenance Installations Operated Using Working Capital Funds

Depots provide material maintenance or repair requiring the overhaul, upgrading, or rebuilding of parts, assemblies or subassemblies, and the testing and reclamation of equipment as necessary on end item orders placed by the military services. The maintenance process across the services and depots generally involves three primary steps: planning, disassembly, and rebuilding, as illustrated in figure 2 below.

Planning. The depot maintenance process begins by planning the maintenance to be conducted on an end item, which could be a weapon system or depot-level reparable (e.g., an aircraft engine or brake assembly).[20] Proactive and accurate planning is necessary to ensure the timely availability of spare parts for the maintenance process, especially since the acquisition lead time for spare parts can range from days to years. In addition, depots consider the likely timing of orders, customer requirements, the accuracy of estimated order projections based on demand forecasting, and whether the resources necessary to perform the work are available. Mismatches between planned workload and actual workload may result in carryover.

Disassembly. Once the end item is inducted into the maintenance process it is disassembled and inspected to determine the type and degree of repair required or whether the parts need to be replaced. Repairs vary by the time and type of use since the last overhaul. Because usage differs from end item to end item, demands on the supply chain for new and repaired items, varies. Unanticipated requirements that emerge during disassembly, such as those associated with aging airframes or battle or crash damage may result in carryover.

Rebuilding. Following disassembly, the end item is rebuilt with new or repaired parts. In general, the rebuilding of the end item follows a sequential process. Once the end item is rebuilt, it is tested and validated for sale to or use by the customer (e.g., a military unit). Customer changes to the terms of work during the rebuilding process, if allowed, may increase the amount of work and result in delays that contribute to carryover. For example, if a customer changes the rebuilding of end items to include unplanned modernization efforts, the change may alter requirements related to the production lines needed to perform the work, and parts requirements. These altered requirements may in turn cause a change in the industrial facilities, specialized tools and equipment, or experienced and trained personnel needed to complete the work, which may result in carryover.

Depot Funding and Workload Carryover

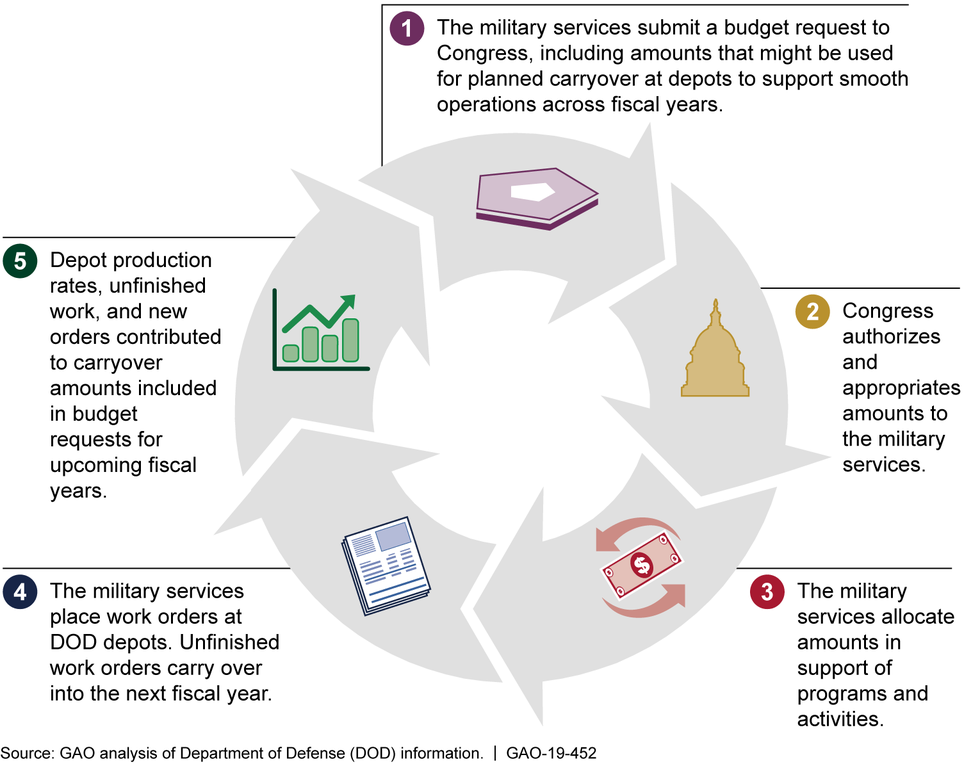

As part of the annual DOD budget submission for each upcoming fiscal year, the military services develop projected depot maintenance requirements, including depot orders anticipated to cross fiscal years, and present those amounts in their appropriations request. Working capital fund activities, such as the depots, also identify and report existing carryover amounts as unfilled customer orders as part of the budget submission.[21] The budget and funding process related to depots supported through working capital funds is depicted in figure 3.

Figure 3: Budget and Funding Process Related to Depots Reporting Workload Carryover

After DOD submits its budget request, Congress authorizes and appropriates funds for use by the military services for orders placed at depots. The amount of carryover at the end of the fiscal year is considered by DOD when preparing the next DOD budget request. Carryover may increase or decrease depending on the rate at which orders are completed by the depots and the amount of new orders accepted by the end of a fiscal year.

Carryover is measured as the dollar value of ordered, funded unfinished work at the end of the fiscal year. Carryover may also be expressed as the amount of time, generally in months, needed to complete the unfinished work. Expressing carryover in months allows the magnitude of carryover to be put in perspective when the scale of operations differs. For example, if a depot performs $100 million of work in a year and has $100 million in carryover at year-end, it would have 12 months of carryover.[22] However, if another depot performs $400 million of work in a year and has $100 million in carryover at year-end, that depot would have 3 months of carryover. According to DOD, approximately 6 months of carryover is optimal.[23] Too much carryover could result in the depot's working capital fund receiving amounts from customers in one fiscal year but not performing the work until well into the next fiscal year or later. Further, excessive amounts of carryover may result in future appropriations or budget requests being subject to reductions by DOD or the congressional defense committees during the budget review process. For example, for fiscal year 2013 congressional conferees recommended reducing Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force operation and maintenance appropriations request by a total of $332.3 million to account for what was termed as "excess working capital fund carryover."[24]

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

- The Military Services Averaged 5 to 10 Months of Carryover Worth Billions of Dollars per Year for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018, Primarily Due to Planning Issues

- DOD Considered Three Carryover Metrics That Do Not Fully Address All Key Attributes of Quality Information and Could Have Varied Depot Management Implications

- Officials of Selected Private Industry Companies and Foreign Militaries Stated They Do Not Have Policies for Determining an Allowable Amount of Carryover

The Military Services Averaged 5 to 10 Months of Carryover Worth Billions of Dollars per Year for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018, Primarily Due to Planning Issues

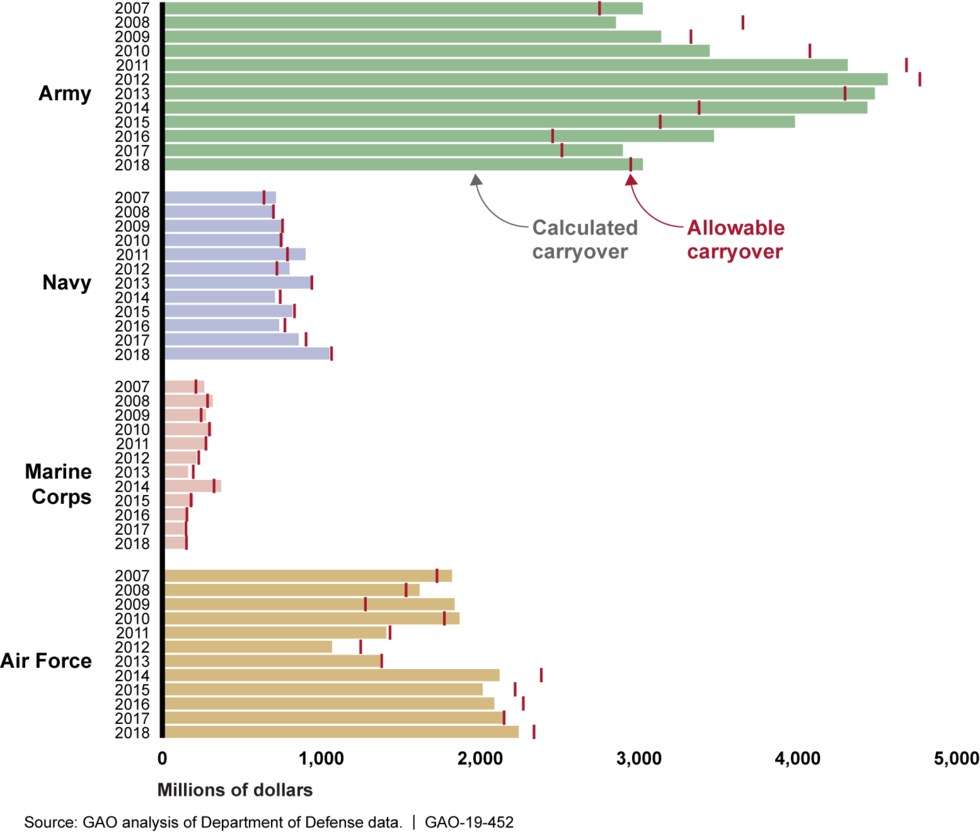

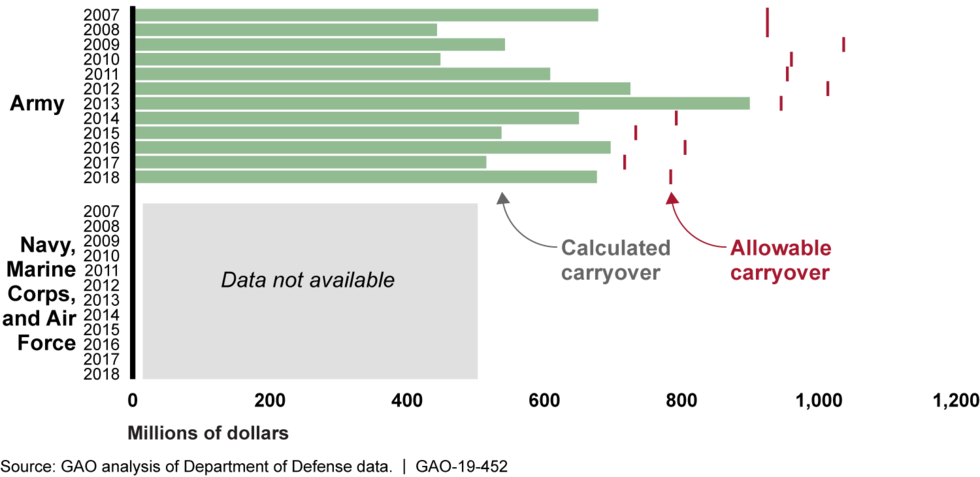

The military services' depots averaged 5 to 10 months of carryover worth an average of $0.2 billion to $4.3 billion per year for fiscal years 2007 through 2018. Specifically, the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force averaged less than six months of carryover worth $1.0 billion, $0.2 billion, and $1.9 billion per year, respectively, during this period. The Army averaged 10 months of carryover per year for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 worth an average of $4.3 billion. The months and dollars of carryover by military service depots for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 are presented in figure 4.

Figure 4: Months and Dollars of Maintenance Carryover by Military Service Depots for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

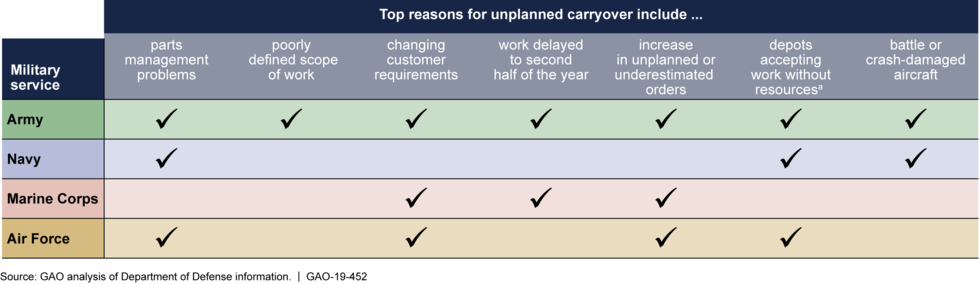

Our prior work on DOD’s depot maintenance since fiscal year 2007 indicates that the top reasons for carryover was primarily due to planning issues.[25] Some carryover is acceptable to facilitate a smooth flow of work from one fiscal year to the next, and the depots may have planned carryover. However, since fiscal year 2007 we have reported seven reasons that contributed to unplanned carryover. The reasons for unplanned carryover may be related to one another or may overlap. For example, depots may accept work without the resources necessary to perform the work, and parts are listed as a resource within that category. At the same time, parts management is cited as a separate reason for unplanned carryover. According to the military service officials, the reasons for unplanned carryover that we have identified in our prior work remain valid. Figure 5 below lists the top reasons for unplanned carryover since fiscal year 2007.

Figure 5: Top Reasons for Unplanned Carryover at Military Service Depots Since Fiscal Year 2007

- Parts management problems. We have reported on parts management issues at depots for many years, and it is a long-standing problem.[26] For example, we found in 2016 that part shortages occurring in 2011, 2013, and 2015 were a factor affecting the depots’ ability to complete maintenance and contributed to carryover.[27] In 2017, we found that DOD has made progress in forecasting for spare parts.[28] Specifically, the Defense Logistics Agency partnered with the military services to improve collaborative forecasting efforts through an analytical, results-oriented approach, such as regularly monitoring key performance metrics. The Air Force Air Logistics Complexes and the Navy Fleet Readiness Centers have transferred all retail supply, storage, and distribution functions to the Defense Logistics Agency, and integrated the Defense Logistics Agency into their parts management processes. The Marine Corps is taking steps to do so, and according to Army officials, the Army has collaborated with the Defense Logistics Agency on several projects to improve parts management performance.[29]

- Poorly defined scope of work. We found in 2013 that the lack of a well-defined scope of work was one of the causes contributing to carryover at Army depots.[30] For example, we found in 2013 that delays associated with poorly defined scope of work resulted in a depot experiencing problems with vehicle designs, reaching agreement with customers on the work to be performed, and performing tests on vehicles. In addition, we found in 2016 that the lack of a well-defined scope of work for 19 Army depot orders placed in fiscal years 2014 and 2015 resulted in $698 million of carryover.[31] The scope of work is a detailed statement of the specific work to be performed for the end item that helps determine the resources needed to perform the work including materials and spare parts, technical data, engineering drawings, equipment, facilities, and personnel.

- Changing customer requirements. In 2016, we found that the mix of customer orders at Army depots tends to change during the year as work is being performed because of operational decisions and changing customer requirements that can increase carryover at fiscal year-end.[32] For example, we found that in fiscal years 2014 and 2015 there were a total of 1,167 program changes to ordered work at Anniston Army Depot valued at $212.1 million and requiring about an additional 1.5 million work hours.[33] In addition, in 2012 we found that 25 of 60 orders contributing to Marine Corps carryover for fiscal years 2010 and 2011 involved amendments to orders accepted in the last quarter of the fiscal year that either increased order quantities or expanded the scope of work to be completed in the subsequent fiscal year.[34] According to Marine Corps officials, some of these orders or amendments to these orders were planned and funded in the fourth quarter of the fiscal year, and work could not start until it was funded according to DOD regulations.

- Work delayed until second half of the year. Since 2007, we found that the Army and Marine Corps started work on new orders later in the fiscal year because they were already performing work on other orders, which contributed to carryover.[35] For example, our analysis of Army depot carryover showed that two of the five Army depots we reviewed accepted more than 20 percent of their new orders in the last 3 months of the fiscal year, which contributed to carryover in fiscal year 2006.[36] Carryover is greatly affected by orders accepted late in the fiscal year that generally cannot be completed, and in some cases cannot even be started, prior to the end of the fiscal year.

- Increase in unplanned or underestimated orders. Accurately forecasting work is essential for ensuring that depots operate efficiently and complete work on orders as scheduled. However, we found that unplanned or underestimated orders contributed to carryover for the Army,[37] the Air Force,[38] and the Marine Corps.[39] For example, in 2011 we found that the Air Force depots received more work from the Air Force than planned. Further, the Air Force depots did not keep pace with the increase in new work orders received from year to year. In 2012, we found that Marine Corps officials cited unplanned workload as a primary driver for carryover, and that for 45 of the 60 orders for fiscal years 2010 and 2011 that we reviewed, customers increased quantities or added unanticipated workload requirements throughout the fiscal year that delayed completing work on existing orders.

- Depots accepting orders without resources. The Army, Navy, and Air Force contributed to carryover by accepting new orders without the resources available to perform the work, such as personnel, technical data, parts, or equipment. For example, in 2015 we found that the Navy accepted work on F/A-18 Hornet aircraft without enough engineers, depot artisans, support equipment, and facilities to perform the work, and additional work was needed for structural repairs with a high number of flying hours.[40] In addition, we found in 2011 that Air Force depot workforce reductions in fiscal year 2008 and during the first 4 months of fiscal year 2009 contributed to growth in carryover amounts for fiscal years 2008, 2009, and 2010.[41] Further, we found in 2008 that the Army depot maintenance budget had significantly underestimated the amount of new orders actually received from customers. Although the depots had increased the number of employees in the past to meet customer demands, the number of employees did not increase at the pace of the new orders actually received from customers, resulting in the large growth of carryover.[42]

- Battle or crash-damaged aircraft. The Army and Navy accepted orders involving work on aircraft with battle or crash damage that was difficult to predict, required nonstandard repairs, and necessitated long lead-time parts. For example, we found in 2016 that Corpus Christi Army Depot had $105 million and $71 million in carryover for fiscal years 2014 and 2015, respectively, on orders to repair crash-damaged aircraft.[43] In fiscal years 2013 and 2014, the Navy depots had $82.8 million and $81.1 million, respectively, in carryover on orders to repair crash-damaged aircraft.[44] According to Army officials, it is difficult to plan for battle and crash-damaged aircraft because the amount and precise type of work required cannot be predicted.

During the course of our review, officials stated that these reasons continue to affect the depots. They did not identify any additional reasons for carryover unrelated to those above. Since 2007, we have made 59 recommendations to address the reasons for carryover, including planning issues. At the time of our review, 46 of these recommendations have been implemented but further action is necessary to implement the remaining 13 recommendations. For example, in 2016 we recommended that the Army incorporate in its regulation provisions to improve communications and coordination with customers to address scope of work and parts issues to reduce carryover.[45] The Army has drafted a regulation to address our recommendation, but it has not been finalized.

DOD Considered Three Carryover Metrics That Do Not Fully Address All Key Attributes of Quality Information and Could Have Varied Depot Management Implications

DOD Considered Three Carryover Metrics in Its Report to Congress

DOD considered the following three options for calculating and determining allowable carryover in its report to the House Committee on Armed Services: the current metric, the OSD-proposed metric, and the Army-proposed metric.[46] Each carryover metric option and related results associated with applying them to depot data for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 are summarized below.

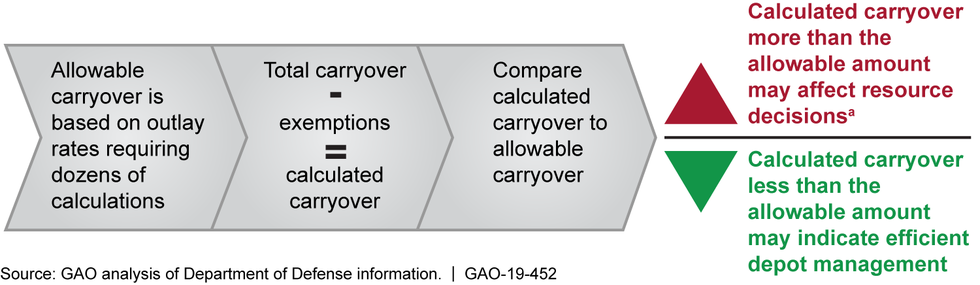

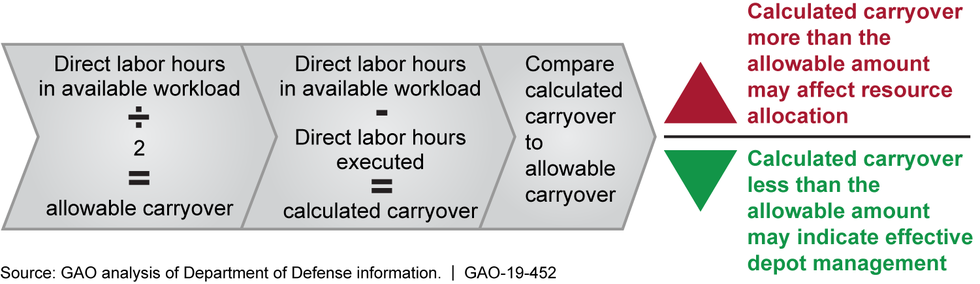

Current carryover metric. The current carryover metric determines allowable carryover based on multiple ways in which appropriations may be spent over time (i.e., outlay rates) requiring dozens of calculations.[47] DOD guidance allows workload to be exempted from carryover calculations if a written request is submitted and approved, and some workload is exempted from the carryover calculation on a regular basis, such as fourth quarter orders and crash-damaged aircraft. One military service may be granted exemptions that differ from exemptions granted to the other military services.[48] These exemptions can result in tens of millions of dollars of workload being excluded from the carryover calculation each year. The current metric for calculating carryover and comparing it to the allowable amount is depicted in figure 6.

Figure 6: Department of Defense’s (DOD) Current Carryover Metric

Under DOD’s current carryover metric, the Army’s calculated carryover has consistently exceeded the allowable amount of carryover from fiscal year 2013 through fiscal year 2018, with calculated carryover for the other military services generally remaining within the allowable amount of carryover for the same period. DOD's current carryover metric results when applied to depot data for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 is depicted in figure 7.

Figure 7: Department of Defense’s (DOD) Current Carryover Metric Results When Applied to Depot Data for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

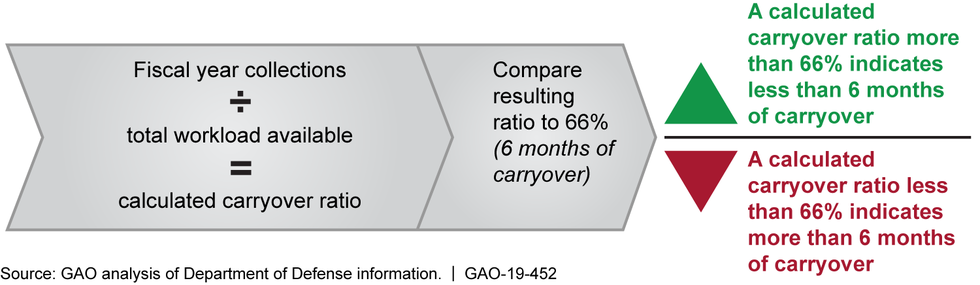

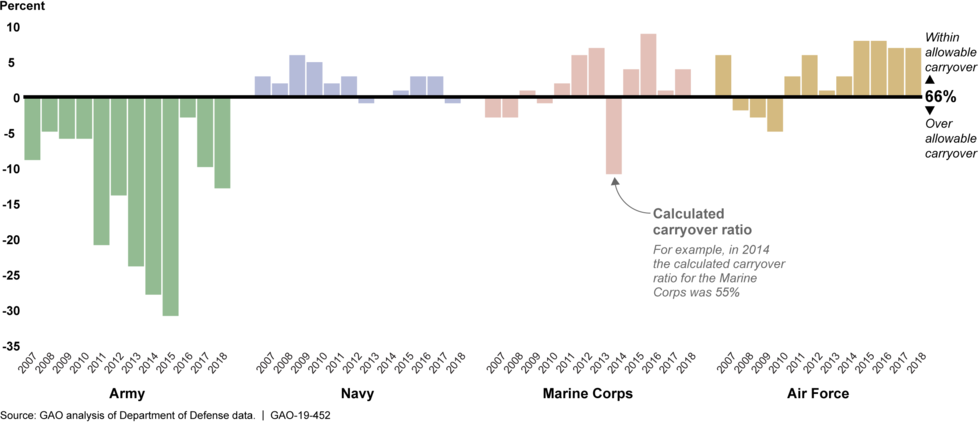

OSD-proposed carryover metric. The OSD-proposed carryover metric compares a calculated carryover ratio with an allowable carryover ratio of 66 percent, which OSD states will allow for 6 months of carryover.[49] The calculated carryover ratio includes all available workload and is calculated by dividing the amount of money collected (collections) in the current year by the combined amount of the monies collected and not yet collected (available workload). Collections during the current fiscal year can be from depot work orders completed during the current or prior fiscal years. The OSD-proposed metric for calculating carryover and comparing it to the allowable amount is depicted in figure 8.

Figure 8: Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)-Proposed Carryover Metric

Our calculations indicate that under the OSD-proposed carryover metric the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force would have been within the allowable carryover amount more often than not for fiscal years 2007 through 2018, but the Army would have consistently exceeded the allowable amount. Results of applying the OSD-proposed carryover metric to budget data for fiscal years 2007 through 2018 are shown in figure 9.

Figure 9: Office of the Secretary of Defense-Proposed Carryover Metric Results When Applied to Depot Data for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

Army-proposed carryover metric. The Army-proposed carryover metric is based on estimates of direct labor hours in available workload. DOD defines a direct labor hour as a common metric for measuring depot maintenance capability, workload, or capacity, representing 1 hour of direct work. The Army-proposed carryover metric includes direct labor hours for orders accepted by the depots along with projected workload to determine the total available workload, and then divides that figure by two to determine allowable carryover. The number of labor hours executed to generate revenue during the fiscal year is then subtracted from available workload to determine calculated carryover, which is then compared to allowable carryover. This approach’s focus on direct labor hours fundamentally differs from the current metric and the OSD-proposed metric. The Army-proposed metric for calculating carryover and comparing it to allowable carryover is depicted in figure 10.

Our calculations indicate that under the Army-proposed metric the Army would have been under the allowable amount of carryover consistently for fiscal years 2007 through 2018, as shown below in figure 11. However, we were unable to calculate carryover or determine the allowable amount for the other military services using the Army-proposed carryover metric because the calculations rely, in part, on projections that are not available to the other military services as well as data that has not been required under DOD regulations since December 2014 and is not produced by the other military services according to Navy and Air Force officials.[50]

Figure 11: Army-Proposed Carryover Metric Results When Applied to Depot Data for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

The Metrics Considered by DOD Do Not Fully Address All Key Attributes of Quality Information

Based on our assessment, the metrics considered by DOD for calculating carryover do not fully address all key attributes of quality information—reliability, completeness, consistency, and appropriateness—although the Office of the Secretary of Defense-proposed carryover metric meets the most attributes as shown in figure 12.

Figure 12: Assessment of Key Attributes of Quality Information in the Department of Defense's Current and Proposed Carryover Metrics

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives and to inform decision making.[51] According to our analysis of those standards, leading practices in results-oriented management, and discussions with DOD officials, we determined that key attributes for providing quality information related to a carryover metric would incorporate reliable data and complete, consistent, and appropriate information, as highlighted below.

- Reliable. The metric uses reliable data if the data is readily available, is reasonably free from error or bias, and represents what it purports to represent. Data obtained through efforts that cannot be easily verified or based on estimates or projected amounts can be subject to inaccuracies.

- Complete. The metric uses complete information if it includes all relevant data needed by decision makers to assess the depot’s performance or make resource allocation decisions. Relevant data has a logical connection with, or bearing upon, the identified information requirements.

- Consistent. The metric is consistent if the military services use the same metric to calculate carryover from year-to-year.

- Appropriate. The metric is appropriate if it is communicated both internally and externally to support decisions related to depot operations and the allocation of resources. When selecting the appropriate metric, management considers the audience (intended recipients of the communication), nature of information (the purpose and type of information being communicated), and availability (information readily available when needed).

Below is a detailed comparison of each metric against the four attributes of quality information.

Current carryover metric. We found that the current carryover metric:

- partially addresses the attribute for providing reliable information. According to DOD officials, the inputs for the calculation for this metric come directly from verified data (e.g., new orders and revenue). However, if the military services do not compute carryover correctly (a process that requires dozens of calculations using rates that can change from year to year) it can lead to errors in budget materials. For example, according to DOD documents the Army had an error in its most recent budget materials because it failed to include updated fiscal year 2018 allowable carryover amounts, an error that resulted in understating Army’s allowable carryover by $48 million.[52] In addition, according to DOD’s carryover report to Congress, some of the inputs used to determine allowable carryover included financial data unrelated to depots.[53] Specifically, the outlay rates associated with different appropriations are unreliable for carryover calculations because they include expenditure information unrelated to depot maintenance.

- partially addresses the attribute for being complete. The information used includes all aspects of depot maintenance operations, such as labor and materials, in the carryover calculation. However, the current carryover metric allows some workload to be exempted, and removing any workload from the carryover calculation prevents it from being complete. Therefore, decision makers do not have all relevant data needed to assess depot performance or make resource allocation decisions.

- does not address the attribute for providing consistent information. The military services use the same methodology and reporting format, but exemptions are not applied to all military services in the same way and vary from year to year. For example, we previously reported that OSD approved three exemptions that allowed the Army to report carryover $363 million below the allowable amount at the end of fiscal year 2011 when the Army’s actual carryover was about $1 billion over the allowable amount without these exemptions.[54] These exemptions were not provided to the other services for the same fiscal year. Therefore decision makers lack consistent information on carryover to support comparison across military services.

- partially addresses the attribute for providing appropriate information. The metric expresses carryover in dollars, but it does not express carryover in months, nor does it clearly define workload exemptions and outlay rate exemptions in budget materials provided to Congress. Therefore, decision makers are not provided with sufficient disclosure about the nature of the information being presented.

According to OSD officials, they rejected the current carryover metric because, even if all exemptions were eliminated, outlay rates presented in DOD financial summary tables may not represent how funds are expended at the depots. The outlay rates provide a profile of how money appropriated for a program is expected to be spent over time according to the type of program, but according to DOD’s carryover report to Congress, the use of outlay rates is the chief weakness in the current carryover metric.[55]

OSD-proposed carryover metric. We found that the OSD-proposed metric:

- partially addresses the attribute for reliable data. The metric uses data that is readily available and is reasonably free from error or bias.[56] However, according to DOD officials, the metric does not represent actual production at the depots in a given fiscal year. Instead, the metric depends on collected amounts based on work depots may have completed in the current or prior fiscal years and the timing of payments made by the military services. Furthermore, collected amounts can be affected by transfers between funds, and accounting corrections and adjustments. On the other hand, revenue directly represents the dollar amount of work performed by depots in a single fiscal year. We found that the timing of collections may affect the carryover metric in a way that does not accurately represent carryover. For example, the Army depot collections increased by more than $3 billion from fiscal year 2015 to 2016, but revenue decreased by $0.2 billion during the same period. As a result, the OSD-proposed carryover metric would not have reflected the Army’s actual depot production if it were in use for fiscal year 2016. DOD officials agreed that basing a carryover calculation on revenue generated by the depots rather than collections would provide a more reliable approach for measuring carryover and that doing so would be supported by data provided under current DOD regulations.

- addresses the attribute for providing complete information. The metric includes all aspects of depot workload without exemptions.

- addresses the attribute for providing consistent information. The metric eliminates the exemptions that result in carryover calculation variations across the military services and allows for valid year-to-year comparisons of carryover across the military services.

- partially addresses the attribute for providing appropriate information. The metric shows whether the actual carryover ratio at depots exceeds the 66 percent benchmark, but does not provide a carryover dollar amount. The OSD-proposed carryover metric also uses an inverse ratio relationship that allows a higher amount of carryover to be expressed by a lower carryover ratio, which makes the concept of the ratio difficult to understand given that it is counter-intuitive. OSD officials acknowledged that using a 66 percent benchmark ratio that represents 6 months of carryover and having a higher ratio represent lower carryover might be confusing to decision makers, and therefore inappropriate. DOD officials also agreed that reporting carryover in terms of months and dollars with a direct relationship to actual amounts of carryover would provide the most appropriate information to support depot management and the allocation of scarce resources.

According to OSD officials, making adjustments to the OSD-proposed carryover metric may allow them to more fully address the key attributes for providing quality information on depot maintenance carryover. OSD, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force officials stated that this metric, by including all workload (without exemptions), provides the most complete view of carryover, and that establishing the same 66 percent benchmark for allowable carryover of 6 months across all military services is equitable and logical. OSD officials acknowledge that it may be difficult for the Army to comply with this benchmark and would plan to provide interim targets until the Army can reasonably reduce carryover to address it.

Army-proposed carryover metric. We found that the Army-proposed carryover metric:

- does not address the attribute for reliable data. Rather than basing the Army-proposed carryover metric on actual results, it is based on estimates and projections that are subject to inaccuracies and data that is not easily verifiable.

- does not address the attribute for providing complete information. The metric focuses on direct labor hours and does not include other aspects of depot maintenance carryover such as parts and materials. Therefore, the Army-proposed carryover metric does not include all relevant data needed to assess depot performance.

- does not address the attribute for consistent information. The metric is based on information that the other military services do not collect. Specifically, some of the information related to direct labor hours the Army used to perform its calculations is not required in DOD’s Financial Management Regulation, and the other military services do not collect or retain the data necessary to complete the Army-proposed metric calculations. Therefore, comparisons cannot be made across military services.

- does not address the attribute for appropriate information. The metric relies on direct labor costs and does not measure other aspects of carryover such as parts and material. Furthermore, the metric does not provide meaningful information to support decisions related to the allocation of resources.

According to Army officials, there are two key reasons they put forward an alternative carryover metric. First, having a metric that is based on direct labor hours provides a more relevant measure for what the depots can and have produced. According to the Army officials, direct labor hours are an input to the depot maintenance process that depots can readily influence, whereas the timing of customer orders and changes in customer requirements are beyond the control of depot management. However, the other services face these same conditions and have repeatedly been able to keep their carryover to around 6 months or less over much of the last 12 years. Moreover, direct labor hours are only one of many inputs of the depot maintenance process. Focusing solely on direct labor hours as an input is contrary to best practices for outcome-oriented performance metrics.[57] Specifically, outcomes are related to the extent to which a program achieves its objectives, but inefficiencies such as re-work can increase the number of labor hours expended without improving results.

Second, Army officials stated the Army recognizes revenue related to parts differently from the other military services. The Army recognizes revenue when a depot uses a part whereas the other military services recognize revenue from parts much earlier in the process and without regard for when they are used. Army officials stated this practice allows the other military services to artificially reduce reported carryover simply by receiving parts that were ordered. However, the portion of other military service’s carryover attributed to parts does not differ significantly from the Army, and any differences in the timing of revenue recognition for parts are not likely to be a principle reason the Army averages approximately 4 months more carryover than the other military services.

Congress and DOD decision makers need quality information about the amount of carryover that is acceptable to adequately address performance at depots and ensure that resources are being allocated appropriately. In developing a proposed metric, DOD’s carryover working group—comprised of representation from OSD and each of the military services—focused on addressing Congressional requirements, simplifying the carryover metric, and avoiding the need for additional resources to calculate carryover amounts.[58] However, according to DOD officials, DOD did not develop a systematic approach at the outset for evaluating a carryover metric for depot maintenance. For example, DOD did not identify key attributes, such as reliability, completeness, consistency and appropriateness, desired in its carryover metric. As a result, the working group developed the proposed carryover metric without determining if it would yield quality information. DOD officials stated that they did not discuss all the attributes of quality information appropriate for a carryover measure in their report to Congress because there was no requirement to do so. When we identified and discussed key attributes of quality information and performance measures with OSD officials, they agreed that the key attributes we identified should be considered when developing and adopting a carryover metric.

Unless DOD adopts a carryover metric for depot maintenance that results in reliable, complete, consistent, and appropriate information, decision makers may not have the quality information they need to make decisions. Specifically, DOD and Congressional leadership would not be well positioned to determine whether funds are directed to the highest priority while simultaneously assuring depots are managed as efficiently and effectively as possible.

The Metrics Considered by DOD Could Have Varied Depot Management Implications

The metrics considered by DOD could have varied depot management implications. DOD’s three carryover metric options—the current, OSD-proposed, and Army-proposed—measure carryover workload differently, with a variety of depot management implications and different results from each carryover metric.

Current carryover metric implications. Using DOD’s current metric, depot management lacks incentives to correct long-standing problems because exemptions may prevent the level of scrutiny and possible corrective actions if problem areas were more transparently reflected in higher carryover amounts. Allowing exemptions also undermines workload planning by eliminating incentives to engage in comprehensive workload planning. The reasons for carryover discussed in our prior reports since fiscal year 2007 often relate to workload uncertainties, such as changes to customer requirements and unplanned or underestimated workload. These issues occurred while the current metric for calculating carryover was in use by DOD.

OSD-proposed carryover metric implications. First, using the OSD-proposed metric sets the same benchmark for all of the military services, but Army depots are unlikely to achieve the OSD-proposed benchmark of representing 6 months of carryover in the near term based on our analysis of historical data. On the other hand, Navy and Marine Corps officials stated that a benchmark of 6 months of carryover may not provide a “stretch goal” and allowing 6 month of carryover may result in decreased management attention to depot operations and how it contribute to carryover. Second, including all workload in the calculation of carryover without exemptions under the OSD-proposed metric could provide incentives to improve workload planning, increase the level of scrutiny to workload previously excluded from calculated carryover, and prompt corrective actions to be developed. For example, including late-year workload from other military services in the carryover calculation (exempted under the current metric) may provide an incentive to improve planning for this type of work.

Army-proposed carryover metric implications. Carryover is expressed in direct labor hour dollars using the Army-proposed carryover metric, but allowable carryover amounts are not meaningful, in part, because carryover amounts are unlikely to exceed the ceiling according to our assessment of Army data. As a result, the Army-proposed carryover metric is not likely to provide an incentive to improve depot management. For example, as previously discussed, the Army had more than a year’s worth of actual carryover in 2011 and 2014 (see figure 4 above), but if this metric were in use, the Army would have remained within the allowable amount every year since 2007.

Officials of Selected Private Industry Companies and Foreign Militaries Stated They Do Not Have Policies for Determining an Allowable Amount of Carryover

Officials of selected private industry companies and foreign militaries we met with stated they have workload that carries over across fiscal years, but they do not have a policy for determining an allowable amount of carryover. First, officials of the nine private companies we interviewed told us that their companies do not have a policy for determining an allowable amount of carryover. Officials also stated that there is no parallel to the role of carryover in the U.S. government budget process in the private sector. In the private sector, officials stated that companies generally perform work and customers pay for work according to the terms of a contract. Although not all work may be complete at the end of a year, there is no policy limiting the amount of work allowed to carry over from year to year. According to generally accepted accounting principles, funded orders or orders related to a binding agreement or contract for work not completed at year-end, can be accounted for as unearned (deferred) revenue and recorded as a liability on the entity's balance sheet. Private sector officials told us that there is no incentive to limit workload accepted if the customers’ needs can be met within the terms of the contract and the work is likely to be profitable. If private companies are not equipped to provide needed workload, they include the cost of additional resources in a business case analysis before accepting the work. Officials stated it is unlikely their customer’s resources would in any way be affected by the amount of work remaining to be completed at the end of a fiscal year.

Second, officials of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and seven foreign militaries we interviewed told us that their organizations do not have a policy for determining an allowable amount of carryover, and their approach to depot maintenance and any carryover that may result differs in a variety of ways.

- Reliance on private industry or DOD. Officials from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and five of the seven foreign militaries we interviewed told us that they do not have their own facilities to perform depot maintenance. Instead, weapon systems sustainment and overhaul work is outsourced (contracted out) to private industry or DOD depots.[59] French and Canadian officials stated that their militaries perform a limited amount of depot maintenance in government-owned facilities when compared to DOD depots. In addition, United Kingdom officials stated that their militaries have capabilities to manufacture and repair munitions and missiles but relies in most instances on contract support for depot-level maintenance and overhauls of ground vehicles, heavy equipment, or aircraft.

- Budgeting for depot maintenance. According to foreign military officials, other nations use a variety of different approaches to budgeting for depot maintenance workload based on their form of government. For example, all of the foreign militaries we interviewed have their defense budgets approved on a multi-year basis and most foreign militaries have limited latitude for spending outside the approved budget for each fiscal year.

- Approach. According to foreign military officials, they use approaches to depot maintenance that fundamentally differ from the approach used by U.S. military services. For example, Germany sets levels for overall weapon systems readiness and availability in the terms of a contract with a private sector provider according to the usage needs of the military, and then holds the provider accountable for addressing the terms of the contract. In contrast, the U.S. military services place orders to complete work on specific items that may or may not insure DOD’s weapon systems readiness and availability requirements are met. In other words, the U.S. military services purchase work from the depots in a batch or individual fashion to repair, overhaul, or modernize specific items, while Germany pays contractors to achieve a desired outcome.

Conclusions

DOD allows depots to carry over billions of dollars of funded unfinished work from one fiscal year to the next to facilitate the smooth flow of work. While some carryover of work is appropriate, excessive carryover may reflect an inefficient use of resources that otherwise might be redirected to other priorities. DOD considered three metric options for calculating depot maintenance carryover; however, the metrics do not fully address key attributes of providing quality information that is reliable, complete, consistent, and appropriate and have varied depot management implications. Ensuring that the carryover metric meets key attributes for providing quality information would improve decision-makers' ability to assess whether depots are managed as efficiently and effectively as possible, and determine the amount of carryover sufficient to support smooth operations from year to year. Until DOD adopts a carryover metric that addresses the attributes for providing quality information, decision makers may not know if the billions of dollars invested for work performed at depots are being used efficiently or might be redirected for other purposes.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In written comments on a draft of this report, DOD concurred with the recommendation. DOD’s comments are reprinted in their entirety in appendix II. DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Acting Secretary of Defense, the Secretaries of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff has any questions about this report, please contact Diana Maurer at (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov, or Asif Khan at (202) 512-9869, or khana@gao.gov. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff that made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Diana Maurer

Director,

Defense Capabilities and Management

Asif A. Khan

Director,

Financial Management and Assurance

Congressional Addressees

The Honorable John Garamendi

Chairman

Subcommittee on Readiness

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Doug Lamborn

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Readiness

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Joe Wilson

House of Representatives

Appendixes

IN THIS SECTION

Appendix I: Scope and Methodology

To determine how much carryover the military services had in months and dollars for fiscal years 2007 through 2018, and the reasons for carryover, we compiled information from Department of Defense (DOD) budget submissions and our prior reports. We included in our scope only those depots managed with working capital funds and therefore subject to the carryover calculation guidance.[60] We excluded the U.S. Naval Shipyards which generally are not managed with working capital funds, but are managed through direct funding.[61] To determine the carryover for fiscal years 2007 through 2018, we analyzed Army, Navy, and Air Force Working Capital Fund budget submissions to identify military service depot carryover and revenue for this time period.[62] We converted reported carryover amounts into months of carryover for each military service to present comparable data.[63]

We assessed the reliability of the data by (1) interviewing Army, Navy, and Air Force officials to gain their opinions on the quality and accuracy of the data presented in the Army, Navy, and Air Force Working Capital Fund budgets, and (2) reviewing our prior work to determine if there were reported concerns with Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps budgetary data.[64] Based on our assessment, we determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

Next, we analyzed our prior reports to determine the reasons for carryover.[65] In those reports, we met with responsible officials from the military service headquarters and depots to identify contributing factors that led to carryover. We performed walk-throughs of selected depot maintenance operations to observe the work being performed and discussed with officials the reasons for workload carrying over from one fiscal year to the next. To corroborate the information provided by the officials, we obtained and analyzed orders that had the largest amounts of carryover for selected years. Because we selected orders for review based on dollar size of carryover each year for the depots we visited previously, the results of these nonprobability samples are not generalizable to all orders under review at that time. In addition, our prior reports do not identify every reason for carryover. In this audit, we discussed the reasons for carryover we identified in our prior reports with military service officials to determine whether these continue to be reasons for carryover, and whether any new causes exist that were not identified in our prior reports. We did not conduct additional analysis to identify reasons for carryover in the fiscal years not covered in our prior reports for each military service since 2007. We analyzed the reasons for carryover presented in our prior reports to determine whether the reasons were related to planning issues, and whether the recommendations made in these reports were implemented.

To determine the implications associated with using current or proposed carryover metrics, and whether the metrics provide quality information, we reviewed documents related to the current metric, the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)-proposed metric, and the Army-proposed metric. We determined how the calculations are performed for each metric.

- For the current metric, we analyzed budgetary data contained in Army, Navy, and Air Force Working Capital fund budgets to determine the amounts of Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps allowable and calculated carryover for fiscal years 2007 through 2018.

- For the OSD-proposed metric, we analyzed financial data presented in the Report on Budget Execution and Budgetary Resources (SF-133) to develop a carryover ratio for each of the military services to compare to the allowable ratio for the same fiscal years.

- For the Army-proposed metric, we analyzed Army Working Capital Fund budgets and supporting documentation to determine the allowable and actual carryover amounts based on direct labor hours for those same fiscal years. The information used to perform the calculation was a combination of actual and estimated or projected amounts. We could not calculate the Army-proposed metric for the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps because the requirement to collect direct labor hour data necessary for the Army-proposed carryover metric was eliminated under the current carryover metric, and the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps did not retain this data.

We then evaluated the results of these three carryover metrics to determine the implications on depot management. Additionally, we interviewed agency officials and reviewed Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government,[66] our prior reports related to measuring and managing DOD performance, and the OSD report on carryover to identify key attributes of quality information related to carryover (i.e., data from reliable sources and provision of complete, consistent, and appropriate information). We then confirmed the appropriateness of attributes for evaluating the carryover measure with agency officials. We compared these attributes to each of the carryover metric options and had multiple analysts independently assess the extent to which each metric incorporates the attributes and verified the results.

To determine whether selected private industry companies and foreign militaries have a policy to limit allowable carryover, we interviewed officials from nine private industry companies that do work comparable to DOD depots and officials from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and seven foreign militaries, and reviewed related documents. Specifically, we interviewed officials from nine private industry companies including (1) AM General, (2) BNSF Railway, (3) Boeing, (4) Caterpillar, (5) General Dynamics, (6) John Deere, (7) Lockheed Martin, (8) Raytheon, and (9) United Airlines. In addition, we interviewed officials representing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and seven foreign militaries including (1) Australia, (2) Canada, (3) France, (4) Germany, (5) Japan, (6) Netherlands, and (7) the United Kingdom, and visited selected Embassies located in Washington, D.C. We selected companies and foreign militaries because they perform work on weapon systems similar to those used by the United States military or maintain systems-of-systems sufficiently similar in complexity and scale to those used by the United States military. The companies we selected may also perform work at DOD depots, and the foreign militaries we selected have diplomatic ties to the United States. Our findings are based on interviews with companies and foreign militaries may not be representative of all relevant companies and militaries, but provide examples regarding how they approach allowable carryover.

Finally, we interviewed officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition and Sustainment), the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) and Chief Financial Officer, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Financial Management and Comptroller), the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Financial Management and Comptroller), the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Financial Management and Comptroller), Washington, D.C. and conducted a site visit to the Army Materiel Command, Huntsville, Alabama.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2018 through July 2019 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix III: GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

GAO Contacts

Diana Maurer, (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov, or Asif A. Khan, at (202) 512-9869, or khana@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts named above, Jodie Sandel (Assistant Director), Roger Stoltz (Assistant Director), John E. “Jet” Trubey (Analyst In Charge), John Craig, Amie Lesser, Felicia Lopez, Keith E. McDaniel, Carol Petersen, Clarice Ransom, and Mike Silver made key contributions to this report.

Related GAO Products

Military Readiness: Analysis of Maintenance Delays Needed to Improve Availability of Patriot Equipment for Training. GAO-18-447. Washington D.C.: June 20, 2018.

Army Working Capital Fund: Army Industrial Operations Could Improve Budgeting and Management of Carryover. GAO-16-543. Washington, D.C.: June 23, 2016.

Defense Inventory: Further Analysis and Enhanced Metrics Could Improve Service Supply and Depot Operations. GAO-16-450. Washington, D.C.: June 9, 2016.

Navy Working Capital Fund: Budgeting for Carryover at Fleet Readiness Centers Could Be Improved. GAO-15-462. Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2015.

Defense Inventory: Services Generally Have Reduced Excess Inventory, but Additional Actions Are Needed. GAO-15-350. Washington, D.C.: April 20, 2015.

Weapon Systems Management: DOD Has Taken Steps to Implement Product Support Managers but Needs to Evaluate Their Effects. GAO-14-326. Washington, D.C.: April 29, 2014.

Army Industrial Operations: Budgeting and Management of Carryover Could Be Improved. GAO-13-499. Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2013.

Marine Corps Depot Maintenance: Budgeting and Management of Carryover Could Be Improved. GAO-12-539. Washington, D.C.: June 19, 2012.

Defense Logistics: DOD Needs to Take Additional Actions to Address Challenges in Supply Chain Management. GAO-11-569. Washington, D.C.: July 28, 2011.

Air Force Working Capital Fund: Budgeting and Management of Carryover Work and Funding Could Be Improved. GAO-11-539. Washington, D.C.: July 7, 2011.

Defense Inventory: Defense Logistics Agency Needs to Expand on Efforts to More Effectively Manage Spare Parts. GAO-10-469. Washington D.C.: May 11, 2010.

Depot Maintenance: Improved Strategic Planning Needed to Ensure That Army and Marine Corps Depots Can Meet Future Maintenance Requirements. GAO-09-865. Washington D.C.: September 17, 2009.

Army Working Capital Fund: Actions Needed to Improve Budgeting for Carryover at Army Ordnance Activities. GAO-09-415. Washington, D.C.: June 10, 2009.

Army Working Capital Fund: Actions Needed to Reduce Carryover at Army Depots. GAO-08-714. Washington, D.C.: July 8, 2008.

References

Figures

- Assessment of Carryover Metrics Identified by the Department of Defense

- Figure 1: Department of Defense Depot Maintenance Installations Operated Using Working Capital Funds

- Figure 2: The Depot Maintenance Process

- Figure 3: Budget and Funding Process Related to Depots Reporting Workload Carryover

- Figure 4: Months and Dollars of Maintenance Carryover by Military Service Depots for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

- Figure 5: Top Reasons for Unplanned Carryover at Military Service Depots Since Fiscal Year 2007

- Figure 6: Department of Defense’s (DOD) Current Carryover Metric

- Figure 7: Department of Defense’s (DOD) Current Carryover Metric Results When Applied to Depot Data for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

- Figure 8: Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)-Proposed Carryover Metric

- Figure 9: Office of the Secretary of Defense-Proposed Carryover Metric Results When Applied to Depot Data for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

- Figure 10: Army-Proposed Carryover Metric

- Figure 11: Army-Proposed Carryover Metric Results When Applied to Depot Data for Fiscal Years 2007 through 2018

- Figure 12: Assessment of Key Attributes of Quality Information in the Department of Defense's Current and Proposed Carryover Metrics

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| DOD | Department of Defense |

| OSD | Office of the Secretary of Defense |

End Notes

Contacts

Diana C. Maurer

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management , maurerd@gao.gov, (202) 512-9627Asif A. Khan

Director, Financial Management and Assurance, khana@gao.gov, (202) 512-9869Congressional Relations

U.S. Government Accountability Office

441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

U.S. Government Accountability Office

441 G Street NW, Room 7149, Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

U.S. Government Accountability Office

441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington, DC 20548

Download a PDF Copy of This Report

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

Order by Phone

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7470

Connect with GAO

GAO’s Mission

Copyright

(103009)