Highlights

What GAO Found

GAO’s 15 covert tests at a nongeneralizable selection of Head Start grantee centers found vulnerabilities in centers’ controls for eligibility screening and detecting potential fraud. Posing as fictitious families, GAO attempted to enroll children at selected Head Start centers in metropolitan areas (e.g., Los Angeles and Boston). For each test, GAO provided incomplete or potentially disqualifying information during the enrollment process, such as pay stubs that exceeded income requirements.

- In 7 of 15 covert tests, the Head Start centers correctly determined GAO’s fictitious families were not eligible.

- In another 3 of 15 covert tests, GAO identified control vulnerabilities, as Head Start center staff encouraged GAO’s fictitious families to attend without following all eligibility-verification requirements.

- In the remaining 5 of 15 covert tests, GAO found potential fraud. In 3 cases, documents GAO later retrieved from the Head Start centers showed that GAO’s applications had been doctored to exclude income information GAO provided, which would have shown the fictitious family to be over-income. In 2 cases, Head Start center staff dismissed eligibility documentation GAO’s fictitious family offered during the enrollment interview.

The Office of Head Start (OHS), within the Department of Health and Human Services, has not conducted a comprehensive fraud risk assessment of the Head Start program in accordance with leading practices. Such an assessment could help OHS better identify and address the fraud risk vulnerabilities GAO identified.

OHS has not always provided timely monitoring of grantees, leading to delays in ensuring grantee deficiencies are resolved. In the period GAO examined, OHS did not consistently meet each of its three timeliness goals for (1) notifying grantees of deficiencies identified during its monitoring reviews, (2) confirming grantee deficiencies were resolved, and (3) issuing a final follow-up report to the grantee. In October 2018, OHS implemented new guidance (called “workflows”) that documents its process for notifying, following up, and issuing final reports on deficiencies identified by its monitoring reviews. However, OHS has not established a means to measure performance or evaluate the results of its new workflows to determine their effectiveness.

Vulnerabilities exist for ensuring grantees provide services to all children and pregnant women they are funded to serve. For example, OHS officials said grantees have the discretion to allow children with extended absences—sometimes of a month or more, according to GAO’s analysis—to remain counted as enrolled. OHS officials told GAO that a child’s slot should be considered vacant after 30 days of consecutive absences, but OHS has not provided that guidance to grantees. Without communicating such guidance to grantees, OHS may not be able to ensure slots that should be considered vacant are made available to children in need. Further, OHS risks paying grantees for services not actually delivered.

Why GAO Did This Study

The Head Start program, overseen by OHS, seeks to promote school readiness by supporting comprehensive development of low-income children. In fiscal year 2019, Congress appropriated over $10 billion for programs under the Head Start Act, to serve approximately 1 million children through about 1,600 Head Start grantees and their centers nationwide. This report discusses (1) what vulnerabilities GAO’s covert tests identified in selected Head Start grantees’ controls for program eligibility screening; (2) the extent to which OHS provides timely monitoring of grantees; and (3) what control vulnerabilities exist in OHS’s methods for ensuring grantees provide services for all children and pregnant women they are funded to serve. GAO conducted 15 nongeneralizable covert tests at Head Start centers in metropolitan areas. GAO selected only centers that were underenrolled to be sure we did not displace any actual, eligible children. GAO also reviewed OHS timeliness goals and data for the period October 2015 through March 2018, and used attendance data to verify enrollment data reported for early 2018 for a nongeneralizable sample of nine grantees.

What GAO Recommends

GAO makes six recommendations, including that OHS perform a fraud risk assessment, develop a system to evaluate the effectiveness of its new workflows, and communicate guidance on when a student’s slot should be considered vacant due to absenteeism. OHS concurred with four recommendations, but did not concur with two. GAO believes the recommendations remain valid.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Executive Action

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following six recommendations to the Director of OHS:

| Number | Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Children and Families: Office of Head Start | The Director of OHS should perform a fraud risk assessment for the Head Start program, to include assessing the likelihood and impact of fraud risks it faces. (Recommendation 1) |

| 2 | Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Children and Families: Office of Head Start | As part of the fraud risk assessment for the Head Start program, the Director of OHS should explore options for additional risk-based monitoring of the program, including covert testing. (Recommendation 2) |

| 3 | Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Children and Families: Office of Head Start | The Director of OHS should establish procedures to monitor and evaluate OHS’s new internal workflows for monitoring reviews, to include establishing a baseline to measure the effect of these workflows and identify and address any problems impeding the effective implementation of new workflows to ensure timeliness goals for monitoring reviews are met. (Recommendation 3) |

| 4 | Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Children and Families: Office of Head Start | The Director of OHS should adopt a risk-based approach for using attendance records to verify the reliability of the enrollment data OHS uses to ensure grantees serve the number of families for which they are funded, such as during OHS’s monitoring reviews. (Recommendation 4) |

| 5 | Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Children and Families: Office of Head Start | The Director of OHS should provide program-wide guidance on when a student’s slot should be considered vacant due to absenteeism. (Recommendation 5) |

| 6 | Department of Health and Human Services: Administration for Children and Families: Office of Head Start | The Director of OHS should develop and implement a method for grantees to document attendance and services under EHS pregnancy programs. (Recommendation 6) |

Introduction

The Head Start program, overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration for Children and Families (ACF) and administered by its Office of Head Start (OHS), is one of the largest federal early childhood programs. It gives grants to local organizations to provide early learning, health, and family well-being services to low-income children and pregnant women in centers, family homes, and other settings. Head Start seeks to promote school readiness by supporting comprehensive development of low-income children. In fiscal year 2019, Congress appropriated over $10 billion for programs under the Head Start Act, to serve approximately 1 million children through approximately 1,600 Head Start grantees nationwide.[1]

In September 2010, we reported on the results of our undercover tests of two Head Start grantees.[2] Those undercover tests revealed instances in which grantees did not follow regulations regarding eligibility verification and enrollment. For example, we found that staff at Head Start centers intentionally disregarded disqualifying income in order to enroll our undercover applicants. We also found for two grantees that the average number of students who attended class was significantly lower than the number of students the grantees reported as enrolled in class, suggesting these grantees were not meeting their Funded Enrollment.[3] As described in greater detail later in this report, OHS took several steps in the years following our September 2010 report, such as requiring all grantees to establish policies and procedures describing actions to be taken against staff who intentionally violate federal and program eligibility-determination regulations.

You asked us to review the Head Start program to see whether the internal control vulnerabilities we identified in 2010 persist. This report discusses (1) what vulnerabilities our covert tests identified in selected Head Start grantees’ controls for program-eligibility screening; (2) the extent to which OHS provides timely monitoring of grantees’ adherence to performance standards, laws, and regulations; and (3) what control vulnerabilities exist in OHS’s methods for ensuring grantees provide services for all children and pregnant women they are funded to serve.

To answer the first objective, we performed covert controls testing at selected Head Start grantee centers. To conduct covert testing, we created fictitious identities and bogus documents, including pay stubs and birth certificates, in order to attempt to enroll fictitious ineligible children at 15 Head Start centers. To ensure we did not displace actual, eligible children seeking enrollment into the Head Start program, we selected five metropolitan areas with high concentrations of grantees with underenrollment to perform covert tests, specifically the Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, New York, and Boston metropolitan areas. We used data from ACF to select a nongeneralizable sample of centers associated with grantees that had reported underenrollment to increase our chances of locating Head Start centers that were taking applications and to better ensure we were not taking the place of an eligible child. Subsequent to the submission of our applications, we overtly requested, as GAO, that the centers provide us information on the applications that were accepted, so we could confirm how they categorized our applications as meeting eligibility requirements.

In addition to covert tests, we reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of eligibility files for real children. We traveled onsite to five additional grantees’ locations to examine whether grantees sufficiently documented each child’s eligibility determination as required by agency standards. These five additional grantees were randomly selected within groups designed to include variation in program size, program type (Early Head Start [EHS], Head Start, or both), geographic area, and whether grantees had delegates.[4] We also interviewed OHS officials about the extent to which they had assessed fraud risks in the Head Start program and compared this information to applicable leading practices for managing fraud risks described in GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework).[5] The covert testing and file reviews we conducted were for illustrative purposes to highlight any potential internal control vulnerabilities and are not generalizable.

To determine the extent to which OHS provides timely monitoring of grantees, we examined OHS’s monitoring guidance and met with senior OHS officials to understand the monitoring process used for the Head Start program. We also met with the vice president of the private contractor primarily responsible for conducting monitoring reviews on behalf of OHS. We compared aspects of OHS’s monitoring process to GAO’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government (The Green Book).[6] As part of this work, we also reviewed all monitoring reports that found a deficiency from October 2015 through March 2018, as well as related follow-up reports. We compared aspects of these monitoring reports to OHS’s internal goals for timeliness in relevant areas.

To determine what control vulnerabilities exist in OHS’s methods for ensuring grantees provide services for all children and pregnant women they are funded to serve, we spoke with OHS officials; communicated with grantees; and reviewed the Head Start Act , agency standards, and grantee policies and procedures. We analyzed attendance and enrollment data for a nongeneralizable sample of nine grantees. We selected these nine grantees by starting with the five grantees we selected for our onsite eligibility file reviews and adding four more grantees using a similar selection methodology that ensured variation in program size, program type, and delegate status. We determined the reliability of enrollment data that grantees reported to OHS for March 2018 by analyzing attendance data for the 60 days leading up to each grantee’s last operating day in March 2018.[7] We selected March 2018 based on discussions with senior OHS officials who identified March as 1 of 2 months that usually have the highest levels of attendance.[8] We calculated enrollment for each grantee and compared our calculations to what the grantees reported to OHS. We also compared our calculations to the levels of enrollment they were required to meet in accordance with their grants, OHS policy, and the Head Start Act. To assess the reliability of selected grantees’ attendance data, we reviewed relevant documentation, interviewed knowledgeable agency officials, and performed electronic testing to determine the validity of specific data elements in the databases. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives. Additional details on our scope and methodology appear in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2017 to July 2019 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We conducted our related investigative work in accordance with investigative standards prescribed by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency.

Background

Head Start Program Overview and Structure

The Head Start program was established in 1965 to deliver comprehensive educational, social, health, nutritional, and psychological services to low-income families and their children. These services include preschool education, family support, health screenings, and dental care. OHS administers grant funding and oversight to the approximately 1,600 public and private nonprofit and for-profit organizations (grantees) that provide Head Start services in local communities. Head Start services are delivered nationwide through these grantees that tailor the federal program to the local needs of families in their service area. For example, grantees may provide one or more of the following program types:

- Head Start services to preschool children ages 3 to the age of compulsory school attendance;

- Early Head Start (EHS) services to infants and toddlers under the age of 3, as well as pregnant women;

- services to families through American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) programs; and

- services to families through Migrant and Seasonal Head Start (MSHS) programs.

Throughout this report, we use the term “Head Start” to refer to both Head Start and EHS, unless otherwise specified, as we did not review the AIAN and MSHS program types as part of this audit. Under the Head Start and EHS program types, grantees must choose to deliver services through one or more program options to meet the needs of children and families in their communities. Grantees most commonly provide services under these program types through the center-based and home-based program options, which deliver services in a classroom setting or via home visits, respectively.[9] Grantees may also deliver services through one or multiple centers. Grantees are required to operate their programs based on the statutory requirements associated with each program option, such as the setting in which services are provided, frequency of services, and staff–child ratios.

Head Start Eligibility Requirements

To enroll in the Head Start program, children and families must generally meet one of several eligibility criteria that are established in relevant statutes and regulations.[10] These criteria include

- the child’s family earns income equal to or below the federal poverty line;[11]

- the child’s family is eligible, or in the absence of child care would potentially be eligible, for public assistance;

- the child is in foster care; or

- the child is homeless.

However, Head Start grantees may also fill up to 10 percent of their slots with children from families who do not meet any of the above criteria, but who would benefit from participation in the program. In this report, we refer to these children and their families as “over-income.” There is no cap on the income level for the over-income families. If the Head Start grantee has implemented policies and procedures that ensure the program is meeting the needs of children eligible under the criteria and prioritizes their enrollment in the program, then the program may also fill up to 35 percent of its slots with children from families with income between the federal poverty level and 130 percent of the poverty level. Children from families with incomes below 130 percent of the poverty level, and children who qualify under one of the eligibility criteria, are referred to as “under-income” for the purposes of this report.

OHS Monitoring Reviews of Grantees’ Performance

OHS’s primary mechanism for monitoring grantee performance is the Head Start Monitoring System. According to OHS, the Head Start Monitoring System assesses grantee compliance with the Head Start Act, the Head Start Program Performance Standards (HSPPS), and other regulations.[12] The Head Start Monitoring System consists of monitoring reviews, which are divided into two focus areas.[13] The purpose of Focus Area One is to conduct an off-site review of each grantee’s program design, management, and governance structure. Specifically, these reviews consist of off-site reviews of grantee data and reports to learn the needs of children and families, as well as the grantee’s program design. Next, reviewers conduct a 1-week period of telephone interviews, during which grantees discuss their program’s design and plans for implementing and ensuring comprehensive, high-quality services. These Focus Area One reviews are supposed to occur in the 1st or 2nd year of the grantee’s 5-year grant cycle.

The purpose of Focus Area Two is to assess each grantee’s performance and to determine whether grantees are meeting the requirements of the HSPPS, Uniform Guidance, and Head Start Act. These reviews begin with preplanning telephone calls with the grantee’s regional fiscal and program specialists, followed by an on-site visit conducted by fiscal and program reviewers. On-site visits typically last 1 week and include discussions, classroom explorations, and reviews of the data grantees collect, analyze, use, and share for decision-making. During these on-site visits, the review team also samples eligibility files from the grantee to ensure the grantee is determining, verifying, and documenting eligibility in accordance with federal requirements. These Focus Area Two reviews are generally supposed to be conducted between the end of the 2nd year and 3rd year of the grantee’s grant cycle.

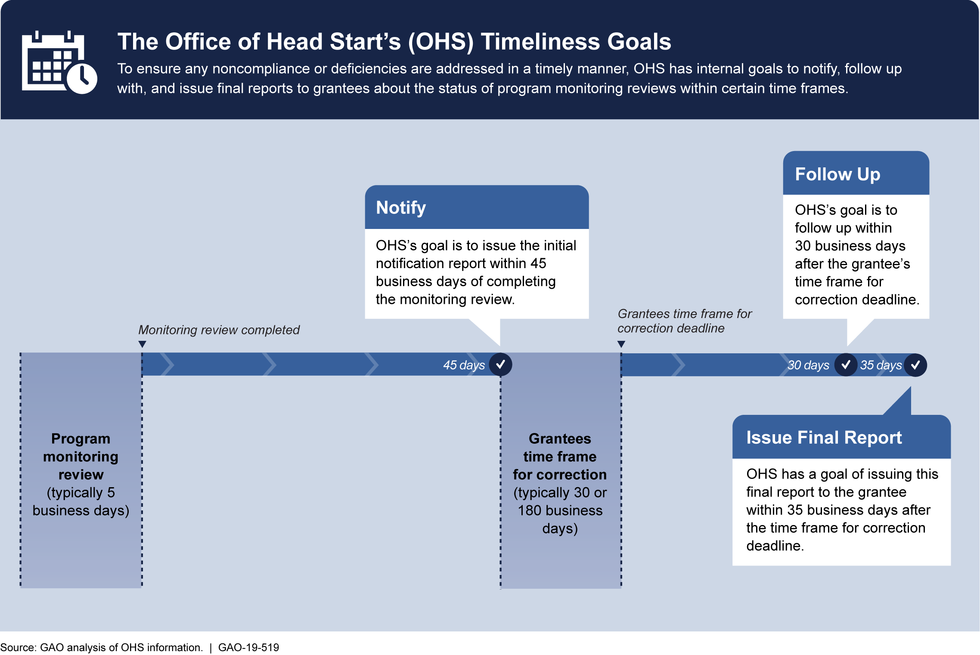

OHS performs Focus Area Two monitoring reviews on many grantees every year. For example, according to OHS officials, OHS performed 406 Focus Area Two monitoring reviews in fiscal year 2018 covering approximately 25 percent of existing grantees. After a monitoring review is performed, OHS reviews the results and determines whether the grantee needs to take steps to correct any problems identified. If OHS determines that the grantee is noncompliant with federal requirements (including, but not limited to, the Head Start Act or one or more of the performance standards), OHS gives the grantee a time frame for correction to resolve the problem. If a grantee does not correct an area of noncompliance within the specified timeline, or if the finding is more severe—such as issues concerning a threat to the health and safety of children, or the misuse of grant funds, among other things—the issue area is considered deficient. Deficiencies have a time frame for correction that is typically 30 or 180 business days. To ensure that any noncompliance or deficiencies are addressed in a timely manner, OHS has internal timeliness goals to notify, follow up with, and issue final reports to grantees about the status of program monitoring reviews, as shown in figure 1.

OHS Process for Monitoring Grantee Enrollment

Grantees must report monthly enrollment data to OHS, and OHS uses these data to monitor whether grantees are meeting their funded enrollment requirements. Specifically, grantees are required to maintain full enrollment, meaning the total number of students that each grantee was funded to serve.[14] Each grantee is also required to report its actual enrollment to HHS on a monthly basis. Within HHS, OHS instructs grantees that “actual enrollment” numbers they report should reflect the total number of children and pregnant women enrolled on the grantees’ last operating day of the month.[15] OHS further instructs grantees to self-report their actual enrollment basis by uploading totals into the Head Start Enterprise System.[16]

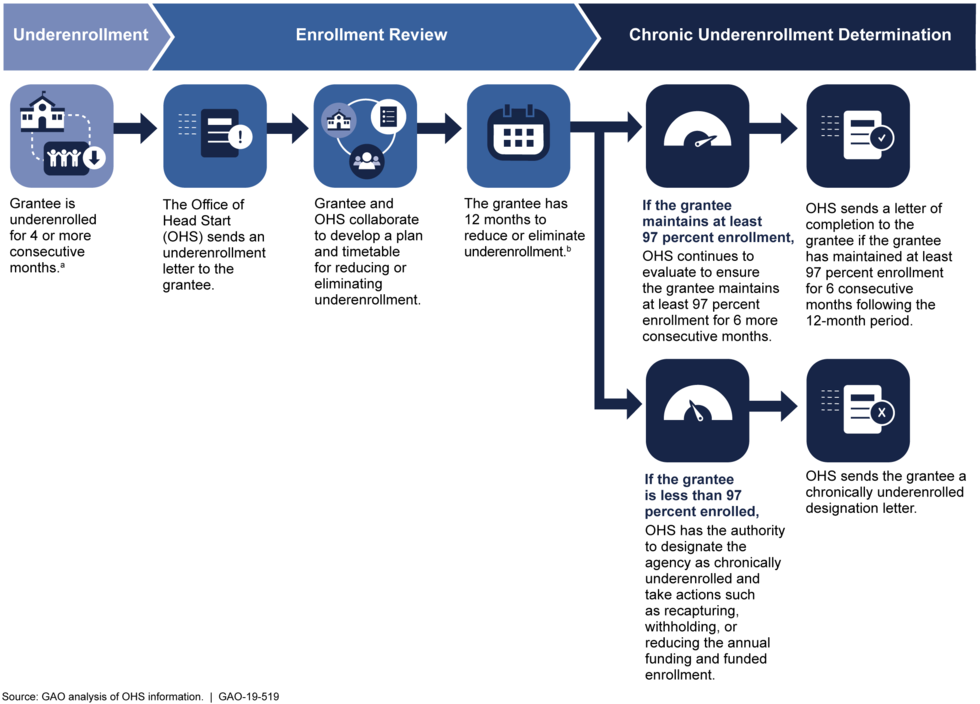

If a grantee’s actual enrollment is less than its funded enrollment, the grantee is considered to be underenrolled, and the grantee must report any apparent reason for this shortfall.[17] If a grantee is underenrolled for 4 or more consecutive months, OHS puts that grantee under enrollment review. During enrollment reviews, grantees must collaborate with OHS officials to develop and implement a plan and timetable for reducing or eliminating underenrollment. If, 12 months after the development and implementation of the plan, the grantee still has an actual enrollment level below 97 percent of funded enrollment, OHS can designate the grantee as chronically underenrolled and may take actions such as recapturing, withholding, or reducing annual funding and funded enrollment. Figure 2 below provides additional details about OHS’s enrollment review process and potential outcomes for grantees.

Figure 2: OHS Enrollment Review Process and Potential Grantee Outcomes

Improper Payments in the Head Start Program

The Improper Payments Information Act of 2002 (IPIA), as amended, defines an improper payment as any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount (including overpayments and underpayments) under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirements.[18] Among other types of payments, improper payments include any payment made to an ineligible recipient and any payment for a good or service not received (except for such payments where authorized by law). The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has also issued guidance stating that when an agency’s review is unable to determine whether a payment was proper as a result of insufficient or lack of documentation, this payment must also be considered an improper payment.[19] OHS officials told us they would consider improper payments in the Head Start program to include (1) services provided to ineligible families (such as to more over-income families than allowed), (2) excess funds distributed to grantees for services not delivered and then used for unallowable purposes, and (3) funding for services to families whose eligibility is insufficiently documented.

Fraud Risk Management and Related Guidance

Fraud and “fraud risk” are distinct concepts. Fraud—obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation—is challenging to detect because of its deceptive nature.[20] Fraud risk (which is a function of likelihood and impact) exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity, have an incentive or are under pressure to commit fraud, or are able to rationalize committing fraud. When fraud risks can be identified and mitigated, fraud may be less likely to occur. Although the occurrence of fraud indicates there is a fraud risk, a fraud risk can exist even if actual fraud has not yet been identified or occurred.[21]

According to federal standards and guidance, executive-branch agency managers, including those at HHS, ACF, and OHS, are responsible for managing fraud risks and implementing practices for combating those risks. Federal internal control standards call for agency management officials to assess the internal and external risks their entities face as they seek to achieve their objectives. The standards state that as part of this overall assessment, management should consider the potential for fraud when identifying, analyzing, and responding to risks.[22] Risk management is a formal and disciplined practice for addressing risk and reducing it to an acceptable level.[23]

We issued our Fraud Risk Framework in July 2015. The Fraud Risk Framework provides a comprehensive set of leading practices, arranged in four components, which serve as a guide for agency managers developing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner. The Fraud Risk Framework is also aligned with Principle 8 (“Assess Fraud Risk”) of the Green Book. The Fraud Risk Framework describes leading practices in four components: commit, assess, design and implement, and evaluate and adapt, as depicted in figure 3.

The Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 requires OMB to establish guidelines that incorporate the leading practices of GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework. The act also requires federal agencies—including HHS—to submit to Congress a progress report each year, for 3 consecutive years, on implementation of the risk management and internal controls established under the OMB guidelines.[24] OMB published guidance under OMB Circular A-123 in 2016 affirming that federal managers should adhere to the leading practices identified in the Fraud Risk Framework.[25]

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

- Covert Tests and Eligibility File Reviews for Selected Head Start Grantees Identified Control Vulnerabilities, Revealing Fraud and Improper Payment Risks That OHS Has Not Fully Assessed

- OHS Has Not Ensured Timely Monitoring of Grantees, but Has Recently Taken Steps to Improve Timeliness

- Vulnerabilities Exist in OHS’s Method for Ensuring Grantees Provide Services to All Children and Pregnant Women They Are Funded to Serve, Heightening Risk of Fraud and Improper Payments

Covert Tests and Eligibility File Reviews for Selected Head Start Grantees Identified Control Vulnerabilities, Revealing Fraud and Improper Payment Risks That OHS Has Not Fully Assessed

Our covert tests and eligibility file reviews for selected Head Start grantees found control vulnerabilities and potential fraud and improper payment risks that OHS has not fully assessed. While our covert tests and eligibility file reviews are nongeneralizable, they nonetheless illustrate that Head Start center staff do not always properly verify eligibility and exemplify control vulnerabilities that present fraud and improper payment risks to the Head Start program. Leading practices for managing fraud risks state that agencies should assess fraud risks as part of a strategy to mitigate the likelihood and effect of fraud. During this review, OHS officials told us they did not believe the program was at risk of fraud or improper payments. However, OHS has not performed a comprehensive fraud risk assessment to support this determination. Performing a comprehensive fraud risk assessment, consistent with leading practices, could help OHS fully assess the likelihood and effect of fraud risk it faces and ensure the Head Start program does not have more fraud risk than the agency is willing to tolerate. Once such a risk assessment is conducted, OHS can use the results to inform the design and implementation of antifraud controls. Consistent with leading practices for managing fraud risks, such controls could include covert tests similar to those we performed for this review, as a way to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of eligibility-verification controls.

Covert Tests at Selected Centers Identified Control Vulnerabilities and Potential Fraud

We performed 15 covert control tests at selected grantees’ Head Start centers and found staff did not always verify eligibility as required, and in some cases may have engaged in fraud to bypass eligibility requirements altogether.[26] Posing as fictitious families, we attempted to enroll children at Head Start centers in the Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, New York City, and Boston metropolitan areas using fictitious eligibility documentation. For each of our 15 tests, we provided incomplete or potentially disqualifying information during the enrollment process, such as pay stubs that exceeded income requirements. As previously discussed, Head Start grantees may fill up to 10 percent of their slots with children from families who do not meet any of the eligibility criteria, but who “would benefit” from participation in the program, commonly referred to as over-income slots. For those tests where it was unclear as to whether the Head Start center processed our application as an over-income slot, we followed up to review the eligibility documentation and see whether it was categorized correctly.

In seven of 15 covert tests, the Head Start centers correctly determined we were not eligible. In these seven tests, staff at the Head Start centers categorized our applications as over-income. In some cases, the staff recommended other child-care services or placed us on a waitlist as an over-income applicant, as permitted by program rules.

In three of 15 covert tests, we identified control vulnerabilities, as Head Start Center staff encouraged us to attend without following all eligibility-verification requirements.

- In one of these three cases, we did not provide any documentation to support claims of receiving public assistance and earned wages, as required by program regulations, but we were still accepted into the program.

- In the second of these three cases, we did not provide any documentation to support claims of receiving cash income from a third-party source, as required by program regulations, but Head Start staff encouraged us to attend nonetheless.

- In the third of these three cases, center staff emphasized we would need to indicate income below a specific amount (the federal poverty level) so that we would qualify. We later retrieved our eligibility documents from this center’s files and found that some documents in the file noted the grantee had reviewed our income information—though we had provided none—and other documents in the file noted the grantee was still waiting on our income documentation. We were eventually contacted by Head Start center personnel and told we were accepted into the program and asked to provide income documentation, though our income had not yet been verified.

While these three cases showed several vulnerabilities, such as instructions regarding income limit and approval without the documentation, we did not categorize these three cases as potential fraud because we did not have evidence of staff knowingly and willfully making false statements or encouraging our applicant to make a statement they knew to be false. Also, in each of these three cases, we were told we could bring the missing documentation when the child began attendance or at orientation.

In the remaining five of 15 covert tests, we found indicators of potential fraud, as described in greater detail below. We plan to refer these five cases of potential fraud to the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) for further action as appropriate.

- In three of these five potential fraud cases, documents we later retrieved from the Head Start centers’ files showed that our applications were fabricated to exclude income information we provided, which would have shown the family to be over-income. For example, in one case the Form 1040 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax form we submitted as proof of income was replaced with another fabricated 1040 tax form. The fabricated 1040 tax form showed a lowered qualifying income amount, and the applicant signature was forged.

- In two of the five potential fraud cases, Head Start center staff dismissed eligibility documentation we offered during the enrollment interview. For example, in one case we explained we had two different jobs and offered an IRS W-2 Wage and Tax Statement (W-2) for one job and an employment letter from a separate employer. The combined income for these jobs would have shown the family to be over-income. However, the Head Start center only accepted income documentation from one job and told us we did not need to provide documentation of income from the second job—actions which made our applicant erroneously appear to be below the federal poverty level.

See appendix II for more details on the results of our 15 covert tests. We withdrew our fictitious families from the programs after each test was completed to ensure we did not take the slot of an eligible child. To view selected video clips of these undercover enrollments, go to https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-19-519.

While the results of our covert tests cannot be generalized to all Head Start centers or applications submitted, these results illustrate how Head Start staff at the selected grantees did not always properly verify eligibility and exemplify control vulnerabilities that present fraud and improper payments risks to the Head Start program.[27] Moreover, the results of our tests are similar to what we found in our 2010 covert testing of the Head Start program. Specifically, in September 2010 we reported that for eight of 13 covert eligibility tests, Head Start center staff actively encouraged our fictitious families to misrepresent their eligibility for the program, and, in at least four cases, documents we later retrieved from centers found our applications were doctored to exclude income information for which we provided documentation.[28] OHS officials told us that they had not implemented covert testing as a management oversight function, which is an action we suggested OHS consider following our covert testing in 2010. Specifically, in our September 2010 report, we suggested several potential actions for OHS management to consider when attempting to minimize Head Start fraud and abuse and improve program oversight, including conducting undercover tests, such as the ones we describe in this report. OHS officials told us that the agency has not conducted such covert tests as part of its monitoring and oversight of the program. These officials explained that they had not done so in part because they believed grantees may react to such testing by taking an overly strict approach to reviewing eligibility that could jeopardize program access for families in legitimate need. OHS officials also noted that they did not have expertise in covert testing and would need to consult with their OIG or others in establishing such a program.

Leading practices for fraud risk management include conducting risk-based monitoring of the program, which can include activities such as covert testing and unannounced examinations, among other activities.[29] During this review, OHS officials also acknowledged that the results of our more-recent undercover tests suggest they may need to explore options for additional risk-based monitoring of the program, including covert testing. For example, OHS officials acknowledged that their current monitoring reviews of eligibility files cannot detect the type of fraud identified by our covert tests, such as when a grantee alters eligibility documents or deliberately fails to collect all income information available from the family, as required. Enhancing its risk-based monitoring of the program through covert testing could help OHS better ensure it better detects and addresses potential fraud and abuse in the Head Start program.

While OHS did not implement covert testing following our 2010 report, OHS has taken several other steps to improve program controls related to eligibility verification and fraud risk management. For example, since March 2015, OHS has required all grantees to retain source documentation used to determine eligibility. Grantees must maintain this eligibility documentation while the child is enrolled in the program and for at least 1 year after the child exits the program to facilitate on-site monitoring reviews to ensure grantees are meeting eligibility requirements. Moreover, to help promote accountability for those making eligibility determinations, in March 2015 OHS started requiring all grantees to establish policies and procedures describing actions to be taken against staff who intentionally violate federal and program eligibility-determination regulations.

However, while OHS has taken steps since our 2010 report to better ensure eligibility verification, our testing shows that vulnerabilities in program controls for verifying eligibility and the related risk of fraud and improper payments persist. For example, our testing demonstrates that vulnerabilities in program controls could allow grantees to fraudulently make it appear that ineligible children are actually eligible—such as by doctoring income documents or purposefully dismissing part of a family’s income to make over-income families appear to have income under the federal poverty level. These vulnerabilities pose the risk that ineligible children will receive Head Start program services through fraud perpetuated by grantees, while eligible children are put on wait lists or otherwise do not receive services. At the same time, as a result of these control vulnerabilities, OHS risks improperly paying grantees to provide services to ineligible families, resulting in potential improper payments. As described in greater detail below, fully assessing the risks of fraud and improper payments in the Head Start program could help OHS better manage these risks.

Case File Reviews for Five Selected Head Start Grantees Identified Control Vulnerabilities and Improper Payment Risks

Case file reviews we conducted for five selected Head Start grantees found eligibility documentation consistently identified the qualifying factors used to determine eligibility as required by program rules. However, we found that files did not always include sufficient documentation to support the enrollment, demonstrating control vulnerabilities and improper-payment risks.[30] Among other things, Head Start eligibility screening requires staff to include the following in each child’s file:

- a statement that staff identified a child’s eligibility through a specific criterion, such as low income, homelessness, or beneficiary of certain public-assistance programs;

- copies of any documents or statements, such as income documentation, that were used to verify eligibility as specified in program regulations; and

- a statement that the intake staffer made reasonable efforts to verify eligibility information through an interview (in person or via phone) and a description of the staffer's efforts to verify eligibility if the applicant submits self-attestation for income.[31]

We reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 256 eligibility files by selecting about 50 files from each of the five selected Head Start grantees to ensure the child’s eligibility determination was sufficiently supported as required by HSPPS.[32] As mentioned, these five grantees were randomly selected within groups designed to include variation in program size, program type (Early Head Start and Head Start), geographic area, and grantees that outsource program administration to third-party delegates.[33]

We found all five selected grantees were compliant in documenting how the child qualified for the program by including a statement in the file that identified a child’s eligibility through a specific criterion, such as homelessness, income, or qualifying public-assistance program for the files we reviewed. Specifically, each of the grantees we reviewed utilized a standard form to capture this information.

However, for all five Head Start centers we reviewed, we identified at least one instance in which grantees did not include sufficient documentation to support the enrollment, such as incomplete or incorrect income documentation. Instances of noncompliance at each Head Start center ranged from one to 15 files. For example, in some instances the application indicated both spouses were employed at the time of the application, but income from only one spouse was included in the file. These examples are not compliant with regulations as total family income is required to determine eligibility. As another example, in one case we reviewed, the supporting income documentation was dated after the application and enrollment dates, meaning that the grantees accepted the child into the program before obtaining documentation to verify the family’s income. While grantee staff said that the pay stubs indicated the family was eligible based on income, the staff acknowledged the information in the file was irreconcilable given the income documentation was dated after the application and enrollment dates.

One of the 256 files we reviewed contained an indication of potential fraud. Specifically, the file indicated the applicant was homeless and had moved from Southeast Texas to North Texas as a result of Hurricane Harvey. However, the file also included a residential rental agreement in North Texas that was signed a month prior to Hurricane Harvey's making landfall in Southeast Texas.

We also found instances in which grantees did not document how intake staff verified eligibility information, as required by relevant regulations, for all five grantees we reviewed.[34] Specifically, we found instances of noncompliance with requirements that grantees document how intake staff made reasonable efforts to verify eligibility information through an interview; or of failure to describe their efforts to verify eligibility if the applicant submits self-attestation for income. A single grantee accounted for 54 of these 87 noncompliances. A senior official from this grantee acknowledged that the files should have included that information and, according to that official, the grantee had since made efforts to correct the noncompliance by using a standard form that captures that information. See table 1 for details and counts on the instances of noncompliance we found among the 256 grantee eligibility files we reviewed.

aThere was one additional file for which we could not determine compliance for this requirement, and it is not counted as noncompliant with this requirement.

bThe total number of files sampled at this grantee was 56, whereas for all other grantees the total was 50.

While our file reviews cannot be generalized to all Head Start centers or applications submitted, these results suggest that Head Start center staff did not always properly verify eligibility, thereby exemplifying control vulnerabilities that pose fraud and improper payments risks to the Head Start program. For example, the results of our file reviews demonstrate that vulnerabilities in program controls could allow grantees to enroll children without documenting all family income, thus making over-income children appear to be from families with income under the poverty level. These vulnerabilities pose the risk of children from over-income families who are ineligible receiving Head Start program services while eligible children from families with income below the poverty level are put on wait lists or otherwise do not receive services. At the same time, OHS risks improperly paying grantees to provide services to ineligible families as a result of these control vulnerabilities. As described in greater detail below, fully assessing the risks of fraud and improper payments in the Head Start program could help OHS better manage these risks.

OHS Has Not Fully Assessed Fraud Risk

OHS has not conducted a comprehensive fraud risk assessment or created a fraud risk profile in accordance with leading practices for fraud risk management, which could allow the type of vulnerabilities we identified in our covert testing and file reviews to persist.[35] For example, without having performed a fraud risk assessment, OHS has not examined the suitability of its existing antifraud controls for mitigating the types of fraud risks we identified in our current work, as well as our previous 2010 work and work by the HHS OIG, suggesting these vulnerabilities are a long-standing issue.

There is no universally accepted approach for conducting fraud risk assessments, since circumstances between programs vary. However, assessing fraud risks generally involves five actions:[36]

- identifying inherent fraud risks affecting the program—that is, determining where fraud can occur and the types of both internal and external fraud risks the program faces;

- assessing the likelihood and impact of inherent fraud risks;

- determining fraud risk tolerance;

- examining the suitability of existing fraud controls and prioritizing risk that remains after application of the existing fraud controls; and

- documenting the program’s risk profile.

According to OHS officials, they have not performed a fraud risk assessment because they do not believe the Head Start program is at significant risk of fraud and improper payments. However, our prior and current work suggests OHS cannot support these assertions. Specifically, during this review, OHS officials told us they reached the conclusion that the Head Start program was not at risk of significant fraud and improper payments in fiscal year 2012 due to low rates or erroneous payments found in their monitoring reviews, as well as an improper-payment risk assessment of the program, utilizing HHS’s standard risk assessment template, which found the program was at low risk for improper payments.[37] In fiscal year 2016 OHS performed another improper-payment risk assessment of the program and determined that Head Start continued to not be susceptible to significant improper payments. However, conducting an improper-payment risk assessment would not necessarily provide OHS insight into fraud risks facing the program and therefore would not support the conclusion that Head Start is not at significant risk of fraud. Further, in January 2019, we reported that we could not determine whether OHS had a reasonable basis for its conclusion that Head Start is at low risk for significant improper payments.[38] Our January 2019 report noted that OHS did not consider the effect of grantees making eligibility determinations in its improper payment risk assessment, and that the inability to authenticate eligibility was one of the largest root causes of improper payments in the government for the period we reviewed.[39] We recommended, and HHS agreed, to revise the process for conducting improper-payment risk assessments, to include preparing sufficient documentation to support its risk assessments. We are continuing to monitor HHS’s efforts in this area.

While OHS has agreed to improve how it documents its risk of improper payments in response to our January 2019 recommendation, OHS could also benefit from taking necessary steps to fully assess the risk of fraud in the Head Start program. As mentioned earlier, our covert tests and file reviews illustrate program control vulnerabilities that present fraud and improper payment risks to the Head Start program. They also demonstrate potential risks inherent in the structure of the program given that grantees are charged with both making eligibility determinations and maintaining full enrollment to meet grant requirements, which is a potential conflict of interest.

Further, according to federal standards for internal control, management should consider the potential for fraud when identifying, analyzing, and responding to risks. As part of these standards, management should use fraud risk factors (including incentives, opportunity, and rationalization) to identify fraud risks.[40] During this review, OHS officials acknowledged the presence of these fraud risk factors in the Head Start program. These fraud risk factors and how they relate to the Head Start program are described in greater detail below:

- Incentives/pressure: Management or other personnel have an incentive or are under pressure, which provides a motive to commit fraud. In the Head Start program, grantees are required to maintain full enrollment and may risk losing some of or their entire grant funding if they do not maintain full enrollment; consequently, grantees may have a financial incentive or may feel pressure to skirt eligibility requirements or to misreport enrollment figures, so that their grant funds are not reduced or jeopardized. OHS senior officials acknowledged that grantees may feel pressure to maintain full enrollment and noted that recent OHS enforcement actions taken against underenrolled grantees may have inadvertently added increased pressure on grantees to demonstrate full enrollment.

- Opportunity: Circumstances exist, such as the absence of controls, ineffective controls, or the ability of management to override controls, that provide an opportunity to commit fraud. In the Head Start program, grantees have the opportunity to commit fraud during the eligibility-determination process by making ineligible families appear to qualify for services, and OHS’s current control activities—its monitoring review process—cannot identify these fraudulent actions. For example, as we found in our covert testing, a grantee could alter eligibility documents or deliberately fail to collect all income information available from applicants, thus making ineligible applicants appear to qualify for the program. Similarly, grantee staff can commit fraud by encouraging an applicant to misreport income, such as by having the applicant self-attest to earning no income, or reporting incorrect income amounts on self-prepared tax documents, giving the appearance that the applicant qualifies for the program. OHS officials acknowledged that its current process for reviewing eligibility files to determine compliance with program rules cannot detect this type of fraud, which heightens the risk that staff at some Head Start centers would take advantage of this opportunity to commit fraud.

- Rationalization: Individuals involved are able to rationalize committing fraud. According to senior Head Start officials, grantee staff’s desire to help families receive services might lead them to rationalize skirting eligibility requirements. For example, OHS officials noted that grantee personnel who work in areas with a high cost of living may encounter families who make too much money to qualify for Head Start, but still cannot afford child care. As a result, OHS officials speculated that grantee staff may rationalize their actions to skirt eligibility requirements in an effort to help families in need of child care.

Taking all of these factors into account and incorporating the fraud risks we identified as part of a comprehensive fraud risk assessment could help OHS fully assess the likelihood and impact of fraud risk it faces and help ensure that the Head Start program does not pose a higher level of fraud risk than the agency is willing to tolerate. Once such a risk assessment is conducted, the results can inform the design and implementation of antifraud controls. Consistent with leading practices of the fraud risk management framework, such controls could include covert tests similar to those we performed for this review, as a way to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of eligibility verification controls.

OHS Has Not Ensured Timely Monitoring of Grantees, but Has Recently Taken Steps to Improve Timeliness

OHS Has Not Ensured Timely Oversight and Monitoring of Grantee Compliance with Federal Requirements, Leading to Delays in Determining That Deficiencies Are Resolved

As part of the monitoring reviews conducted under OHS’s Head Start monitoring system, OHS has internal goals to notify, follow up with, and issue final reports to grantees about the status of program monitoring reviews but has not consistently ensured deficiencies are resolved by grantees in a timely manner. A deficiency is an area of performance in which a grantee is not in compliance with state or federal requirements. Deficiencies may involve a threat to the health and safety of children, the misuse of Head Start grant funds, or other issues.[41]

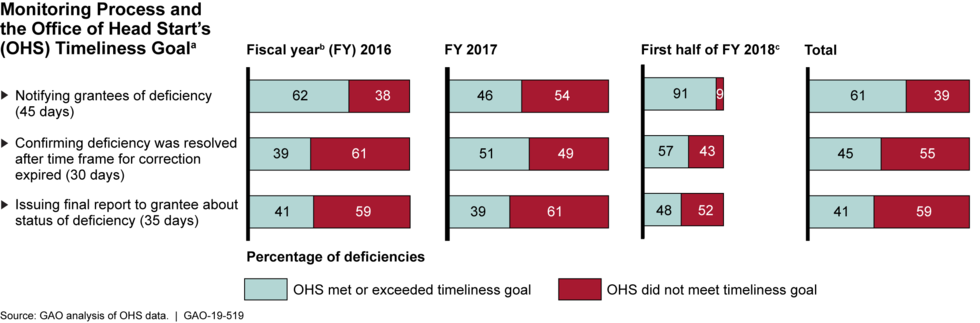

OHS officials told us that, for the period we reviewed, the agency had informal timeliness goals of its monitoring review system. We reviewed all monitoring reviews (242 total) conducted from October 2015 through March 2018 that identified the grantee had a deficiency. OHS officials told us that during this period, the agency had informal timeliness goals for notifying grantees of deficiencies, confirming deficiencies are resolved, and issuing final follow-up reports. According to OHS officials, these informal goals were expectations for OHS staff, but not documented. Specifically, the officials stated that these timeliness goals included

- notifying the grantees that a deficiency was identified within 45 business days of completing the monitoring review,

- confirming the deficiency was resolved within 30 days after the grantees’ time frame for correction expires, and

- issuing a final follow-up report to the grantee about the status of the deficiency within 35 days after the grantees’ time frame for correction expires.

For October 2015 through March 2018, we found OHS did not consistently meet each of its three timeliness goals. Specifically, during this time frame, OHS did not meet its timeliness goal for notifying grantees when a deficiency was identified for 39 percent of deficiencies. Also, OHS did not meet its timeliness goal for confirming the deficiency was resolved after the time frame for correction expired for 55 percent of deficiencies. Further, OHS did not meet its timeliness goal for issuing a final follow-up report to the grantee about the status of the deficiency for 59 percent of deficiencies. Figure 4 below provides additional details on OHS’s timeliness goals and its performance toward meeting these goals from October 2015 through March 2018 (the period covered by our file review).

Figure 4: OHS Time Frames for Notifying Grantees of Deficiencies, Confirming Deficiencies Are Resolved, and Issuing Final Reports from October 2015 through March 2018

OHS officials acknowledged that these monitoring reviews fell short of OHS’s informal timeliness goals during the time frame of our review, and explained that a variety of factors may have contributed to these delays. For example, OHS officials told us that difficult cases that involve OHS’s legal team can absorb staff time and delay the monitoring review process. OHS officials also stated that unclear roles and responsibilities for ensuring the review process was implemented effectively, and higher agency priorities, also contributed to these delays.

Without confirming deficiencies are resolved and issuing final reports on these deficiencies in a timely manner, OHS may allow unresolved deficiencies to linger and pose significant risks to children in the Head Start program. For example, in two monitoring reviews we reviewed, OHS identified instances of child abuse, but OHS did not follow up in a timely manner to ensure the deficiencies were resolved. In the intervening time, according to the monitoring reports, additional instances of child abuse were reported, illustrating the risk of not following up on and ensuring audit findings are resolved in a timely manner.

OHS Has Taken Steps to Improve Timelines for Oversight and Monitoring of Grantees but Has Not Established a Process for Evaluating Its Progress

In October 2018, OHS put in place the first formal guidance that documents its process—including staff roles and timelines—for notifying, following up, and issuing final reports on deficiencies identified by its monitoring reviews. OHS refers to the new guidance as its “workflows.” OHS officials noted the timeliness goals in its new workflows are the same as the informal guidelines previously in place, but the new workflows assign specific responsibilities and timelines for staff to implement. OHS officials told us the new guidance was disseminated throughout the agency and to all relevant parties upon its issuance, and that OHS has provided training to all regional offices, including in-person training to senior staff and review leads. Given that the workflows are new, OHS officials told us that the specific effect of the new workflows remains to be seen.

OHS officials also told us they plan to monitor the success of the new workflows by tracking the timeliness with which they notify grantees of deficiencies; confirm deficiencies have been resolved; and issue final reports of deficiencies. However, OHS officials told us they have not yet developed a method to assess or evaluate the new workflows to ensure timeliness goals are met. According to OHS officials, OHS has assigned a monitoring lead who is responsible for ensuring that the workflows are adhered to as outlined and has weekly meetings with the requisite parties to ensure reports are moving forward in a timely fashion. However, it is not clear what steps OHS will take when time frames are exceeded, and how any monitoring efforts will be evaluated and used to inform the monitoring review process to ensure the timeliness goals are met.

According to federal standards for internal control, management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results. The standards further note that establishing a baseline to monitor the internal control system contributes to the evaluation of results.[42] Specifically, the baseline serves as the current state of the internal control system compared against management’s design of the internal control system. Once established, management can use the baseline as a criterion in evaluating the internal control system and make changes to reduce the difference between the criteria and condition to contribute to the operational effectiveness of internal controls.

Separately, as part of federal standards for internal control, management should evaluate and document the results of ongoing monitoring to identify internal control issues. Management uses this evaluation to determine the effectiveness of the internal control system. Differences between the results of monitoring activities and the previously established baseline may indicate internal control issues, including undocumented changes in the internal control system or potential internal control deficiencies.

According to OHS officials, OHS has assigned a person to perform ongoing monitoring of the new workflows and their effect, but OHS has not defined a baseline to better measure the effectiveness of the workflows and has no plans to evaluate and document the results of these monitoring activities. Specifically, as of February 2019, OHS officials told us that, of the 104 monitoring reports completed since the inception of the new workflows, 90 (87 percent) have moved forward in the appropriate time frame, and follow-up reviews are following a similar process. However, according to OHS officials, there have been no plans to develop a baseline and perform periodic evaluations as the workflows are so new and still in the early phases of implementation. By establishing a baseline to help measure performance and evaluating and documenting the results of this monitoring to determine the effectiveness of its new workflows, OHS would be better positioned to ensure it meets its new timeliness goals and can identify and address any problems impeding the effective implementation of its new workflows.

Vulnerabilities Exist in OHS’s Method for Ensuring Grantees Provide Services to All Children and Pregnant Women They Are Funded to Serve, Heightening Risk of Fraud and Improper Payments

OHS seeks to ensure that grantees provide services to all the children and pregnant women they are funded to serve, but vulnerabilities exist in OHS’s method for monitoring grantees’ service levels. Specifically, OHS relies on enrollment data that may be unreliable for determining the number of children and pregnant women grantees serve, and OHS has not adopted a risk-based approach to verifying grantees’ enrollment data with daily attendance data that may be more reliable for this purpose. Further, OHS does not provide program-wide guidance on when grantees should consider slots vacant after long-term absences, nor does OHS require grantees to document Early Head Start (EHS) pregnancy services. Without addressing these vulnerabilities, the program will remain at risk of fraud and improper payments to grantees for services that are not actually delivered to children and pregnant women in need.

OHS Uses Potentially Unreliable Data to Monitor Grantees’ Service Levels, and Its Recent Efforts Do Not Effectively Verify Data Quality

OHS relies on enrollment data that may be unreliable for monitoring the number of students (children and pregnant women) grantees serve, and OHS’s recent efforts to verify the quality of these data lack consistency and effectiveness. The Head Start Act requires grantees to maintain full enrollment, meaning the total number of students that each grantee was funded to serve.[43] In June 2018, OHS emphasized this requirement by issuing program instructions to grantees stating that they must provide services to 100 percent of the children and pregnant women they are funded to serve.

OHS monitors grantees’ service levels by collecting “actual enrollment” data from grantees each month,[44] and putting grantees under enrollment review after 4 or more consecutive months of underenrollment. However, OHS does not effectively determine the reliability of grantees’ self-reported actual enrollment data by reviewing attendance records to verify the accuracy of the enrollment data grantees submit. Unlike actual enrollment numbers, daily attendance records more accurately represent grantees’ service levels because they demonstrate the extent to which students receive services on a daily basis.[45] Thus, grantees’ attendance records could be used to trace their self-reported actual enrollment numbers to source documents and verify their accuracy.

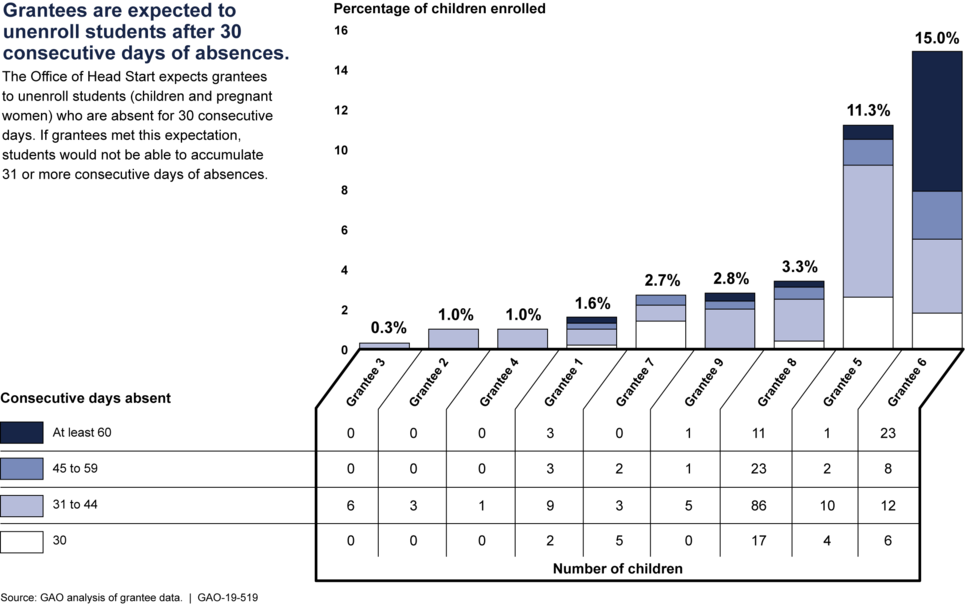

We analyzed attendance records for a nongeneralizable sample of nine grantees to verify the accuracy of enrollment numbers they reported for March 2018. As part of this work, senior officials explained that they expect grantees to unenroll students who have not received services (or were absent) for 30 consecutive days. As described in greater detail below, OHS has not communicated this expectation to grantees.

Applying this expectation, we found that the enrollment numbers reported to OHS for March 2018 would be considered accurate when considering OHS’s expectation for serving students for six of the nine grantees we reviewed.[46] However, the enrollment numbers reported by 3 of the 9 grantees would not be considered accurate . For example, by applying OHS’s expectation, we found one grantee that reported full enrollment would be 91 percent enrolled, and at least 395 slots that were reported as enrolled that month would not be considered enrolled. We found the other two grantees would be just below full enrollment, falling short of OHS’s requirement to serve 100 percent of funded enrollment. Without using attendance data to verify the accuracy of grantees’ self-reported enrollment data, OHS would not be aware that these three grantees would be considered underenrolled in March 2018. Figure 5 provides additional details on our analysis of the reliability of these selected grantees’ self-reported enrollment numbers.

Figure 5: Reliability of Selected Grantees’ Self-Reported Enrollment Numbers Varied for March 2018

In response to our review, OHS officials began taking steps to assess the reliability of grantees’ enrollment data, but OHS does not consistently use attendance data as part of this new process, making it less effective. Initially, OHS officials told us the agency did not use attendance records to verify grantees’ enrollment data because doing so would be too time-consuming. Subsequently, OHS officials told us that, in response to our review, the agency began requiring reviewers to verify the accuracy of grantees’ self-reported actual enrollment data during OHS monitoring reviews in fiscal year 2019. Specifically, reviewers are now required to review grantees’ supporting documentation on-site during OHS’s Focus Area Two monitoring reviews, which occur once during each grantee’s 5-year grant cycle.

While OHS took steps to verify grantees’ self-reported enrollment data, OHS does not consistently require reviewers to consider attendance data as part of its review. Instead, the supporting documentation that reviewers consider depends on grantees’ individual processes and whichever data grantees use to calculate and self-report enrollment. OHS officials said reviewers sometimes use attendance data to verify the enrollment numbers reported to OHS, but the officials were unsure of how often this occurred. In contrast, reviewers often rely on enrollment records that grantees maintain on students’ enrollment dates and drop dates.[47] However, as previously discussed, daily attendance data are a more accurate measure of grantees’ service levels, whereas the students’ enrollment dates and drop dates do not demonstrate the extent to which grantees provided services to the students on a daily basis.

OHS officials expressed confidence in the agency’s new process for assessing the reliability of grantee enrollment data. Specifically, OHS officials told us that its new process of verifying the enrollment reported by the grantee through the grantees’ documentation has provided the agency with evidence of grantees that have overreported enrollment numbers. According to OHS officials, as of early April 2019, 155 grantees had been reviewed using OHS’s new process, and OHS confirmed that three of those grantees had an issue with accurately reporting enrollment. For example, reviewers found that one grantee’s reported enrollment numbers did not match its supporting documentation for 8 of 12 months from November 2017 to November 2018. Specifically, reviewers found that the grantee reported higher enrollment numbers than what was found in enrollment data that the grantee used to calculate monthly enrollment. Based on the results of such reviews, OHS officials believe that their methods appropriately identify misreporting of enrollment by grantees.[48]

While OHS’s methods are a step in the right direction, we note that OHS’s new process may not appropriately identify misreporting of enrollment by grantees when (1) grantee records on enrollment dates and drop dates do not accurately reflect whether the student is actually enrolled and receiving services, and (2) OHS reviewers do not consistently examine attendance records to verify the enrollment numbers reported to OHS. For example, a grantee that uses enrollment records as supporting documentation could intentionally or unintentionally fail to record an enrollment drop date for a student who is no longer enrolled, such as a student who ceased to attend several months in the past, making it appear that the student was enrolled and attending classes even though the student is not. This grantee could then misreport to OHS that the student was enrolled and receiving services. Under OHS’s new process, OHS reviewers may erroneously conclude that the student was enrolled and receiving services if they examine the student’s enrollment date and drop date in the grantee’s documentation, because no drop date would be present in that documentation. Thus, under OHS's new process for verifying enrollment numbers that grantees report, OHS reviewers may not appropriately identify that the grantee misreported enrollment in this and similar scenarios. In contrast, if the OHS reviewers in this scenario examined grantee attendance records, the reviewers may identify that the student had not received services for several months, and therefore could identify that the grantee misreported enrollment.

Prior studies on the Head Start program have similarly shown that enrollment data reported by grantees may be unreliable, suggesting that OHS’s use of potentially unreliable data may be a long-standing issue. For example, in April 2007, HHS OIG reported that some grantees overreported their enrollment data for monitoring purposes.[49] In February 2017, HHS OIG also reported that a grantee significantly overreported enrollment numbers to OHS. Specifically, a grantee reported being an average of 96.6 percent of its funded enrollment over the course of its grant period, but HHS OIG determined the grantee’s average enrollment was 65 percent (or about 868 empty slots per month) of funded enrollment for that same period.[50] Further, GAO found in December 2003 that some grantees reported inaccurate enrollment data.[51] In each of these reports, HHS OIG and GAO made recommendations related to grantee enrollment, and OHS made some changes in response to these recommendations. These actions led to some improvements in OHS’s oversight of grantee enrollment, but our current work suggests that issues with the reliability of the data persist.

Federal standards for internal control call for agency managers to use quality information to achieve objectives.[52] Such practices may include using reliable sources of data that are reasonably free from error and bias and represent what they purport to represent, as well as evaluating both internal and external sources of data for their reliability. Further, leading practices for fraud risk management include employing a risk-based approach to monitoring program controls by taking into account identified risks. In this context, taking a risk-based approach would mean OHS taking into account the risk of grantees intentionally or unintentionally reporting unreliable enrollment, as well as the related fraud and improper payment risks, when determining whether to use grantees’ attendance data to verify the enrollment data that grantees report.

OHS has not adopted a risk-based approach to verifying grantees’ enrollment data with attendance data. Instead, OHS officials told us that their current approach depends on factors other than risk. Specifically, OHS’s current approach depends on grantees’ individual processes and whichever supporting documentation grantees use to calculate and self-report enrollment. This approach does not mitigate the risk that grantees’ individual processes may involve the use of unreliable enrollment records or result in misreporting of enrollment, among other risks.

Without taking a risk-based approach to using attendance records to verify grantees’ enrollment data, OHS risks jeopardizing its ability to ensure enrollment data are accurate and thus risks using unreliable data to monitor grantees’ service levels. Without reliable data, OHS will be unaware of empty slots that may not be accessible to families in need. Further, the Head Start program would remain vulnerable to improper payments made to grantees for services not actually delivered to families, as well as potential fraud when grantees intentionally overreport their monthly enrollment numbers.[53]

OHS Lacks Guidance for Grantees on Creating Vacancies and Documenting Pregnancy Services

OHS does not provide guidance to grantees on when a student’s slot should be considered vacant after long-term absences (such as 30 consecutive days or more). It also does not require grantees to document attendance for EHS pregnancy services. Without such guidance or requirements, OHS further limits its ability to monitor the extent to which grantees actually provide services to children and pregnant women.

Creating Vacancies

OHS does not provide program-wide guidance on its expectations for when grantees should create new vacancies due to long-term student absences. According to OHS officials, once a grantee chooses to unenroll a student, a new vacancy is created. Then, according to OHS’s program instructions, the grantee has a 30-day grace period before the grantee must reflect that new vacancy in the monthly enrollment data it reports to OHS. However, OHS does not provide program-wide guidance to grantees on the extent to which a student can be absent before the grantee should consider the student’s slot to be vacant. Specifically, the HSPPS allows grantees to count a student as enrolled after the student is accepted into a program and attends at least once, but neither the HSPPS nor OHS specify when a student should no longer be counted as enrolled when the student stops attending.[54] For example, under current program rules, a child could hypothetically attend 1 day, then be absent for several months and still be counted as enrolled.

OHS officials told us that grantees have the discretion to determine when a slot should be considered vacant due to absenteeism, which is determined by grantees’ individual policies.[55] However, senior OHS officials also said they believe it is reasonable to vacate an enrollment slot after 30 days of consecutive absences, and these officials told us they further believe this 30-day threshold is likely applied by grantees.[56] However, our analysis of grantees’ attendance records suggests that some grantees may not be applying the 30-day threshold as OHS believes.

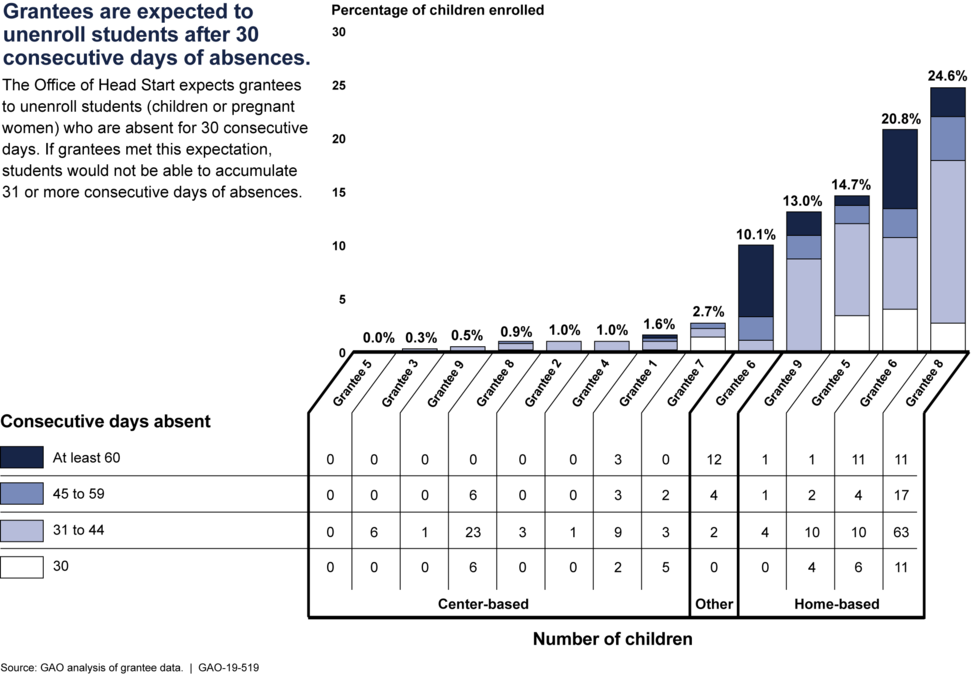

We examined daily attendance records and vacancy policies for a nongeneralizable sample of nine grantees and found children with long-term absences whose slots were considered as enrolled rather than vacant. For example, we found that, from January to March 2018, all nine grantees had at least one child who was absent for 30 consecutive days or more and was still considered enrolled in the grantees’ enrollment records.[57] Further, five grantees allowed at least one child to remain enrolled long enough to accumulate at least 60 consecutive days of absences, as shown in figure 6.[58] As such, these absences suggest that grantees may not be applying the standard that OHS stated it believes to be reasonable by considering these slots to be vacant after 30 consecutive days of absences.

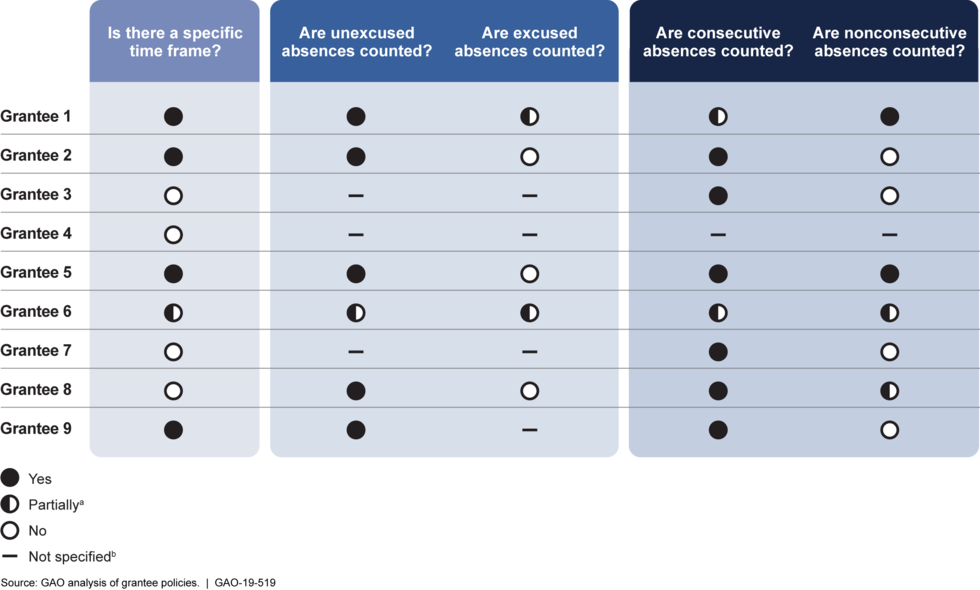

Figure 6: Some Selected Grantees Had Children Enrolled with Long-Term Absences More Often Than Others as of March 2018

We also found that all nine grantees we reviewed documented a policy on circumstances when to consider slots vacant due to absenteeism, and the factors considered in those policies varied. These factors included specific amounts of time after which a slot should be considered vacant, and whether to count unexcused, excused, consecutive, or nonconsecutive absences when deciding to unenroll a student.[59] While most of the grantees counted consecutive absences, about half did not specify the amount of time after which these absences should result in vacancies.[60] Also, some grantees’ policies clarified whether unexcused or excused absences were counted, whereas other grantees’ policies did not. For example, one policy said a child’s slot may be considered vacant if that child (1) falls below 70 percent attendance over a 30-day period, (2) has 50 percent unexcused absences during the past 20 days, or (3) has 50 percent excused absences during the past 30 days. In contrast, another grantee’s policy indicated that families may be unenrolled due to absenteeism and if not responsive to the grantee’s efforts to reengage, but the policy did not specify what type or extent of absenteeism should result in a vacancy. Figure 7 presents additional information on various factors considered in selected grantees’ policies for determining when to vacate enrollment slots due to absenteeism.

Figure 7: Factors Varied in Selected Grantees’ Policies for Determining When to Vacate Enrollment Slots Due to Absenteeism

Federal internal control standards call for agency managers to internally communicate quality information necessary to achieve program objectives.[61] Without communicating guidance to grantees stipulating when a slot should become vacant, OHS lacks assurance that grantees will unenroll students who have stopped receiving services, thus limiting OHS’s ability to monitor grantees’ service levels through grantees’ enrollment data. Consequently, OHS’s lack of guidance to grantees may limit its ability to ensure slots that should be considered vacant are made available to children and pregnant women in need.

Documenting Attendance for Pregnancy Services

OHS also does not require grantees to document attendance for EHS pregnancy services. As mentioned, grantees may also enroll pregnant women into EHS slots to receive pregnancy services, such as prenatal support and facilitated access to medical care. These services represented about 5,720 pregnant women (about 3.5 percent of EHS funded enrollment and 0.7 percent of funded enrollment for Head Start and EHS combined) during the 2018 program year. OHS officials told us there is no requirement for grantees to track attendance data for the pregnancy services that grantees provide. Rather, OHS officials said that reviewers interview grantees during Focus Area Two monitoring reviews to assess the quality of this program, which occur once during grantees’ 5-year grant cycle between year 2 and 3.