Highlights

What GAO Found

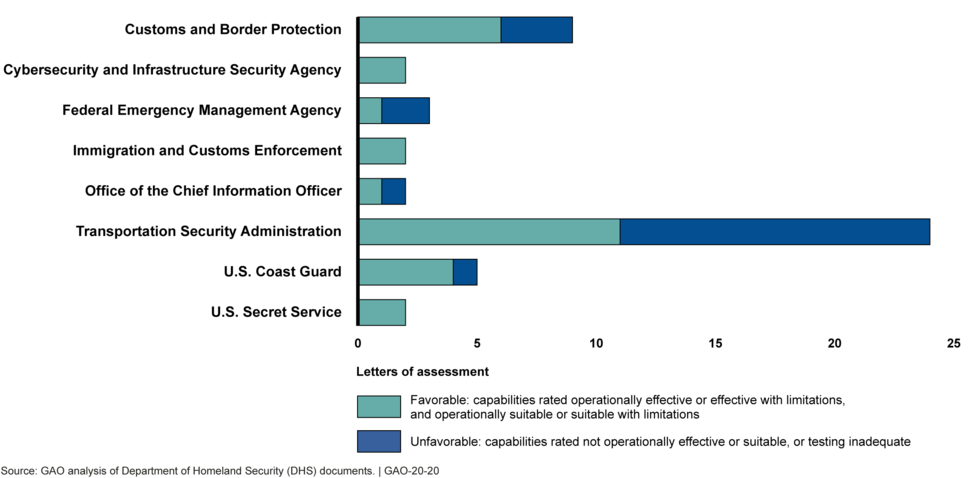

Since August 2010, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office of Test and Evaluation (OTE) has assessed major acquisition programs’ test results and DHS leadership has used OTE’s assessments to make informed acquisition decisions. Programs generally received approval to progress through the acquisition life cycle, but DHS placed conditions on its approvals in more than half the cases GAO reviewed.

Since May 2017, OTE has updated its policies and released new guidance that met nearly all of the key test and evaluation (T&E) practices GAO identified as contributing to successful acquisition outcomes. For example, OTE’s policy directs program managers to designate a T&E manager who is required to be certified to the highest level in the T&E career field—level III. This met the key practice that programs establish an appropriately trained test team. However, OTE’s guidance partially met the key practice to demonstrate that subsystems work together prior to finalizing a system’s design. Specifically, the guidance instructs programs to conduct integration testing, but not until after the design is finalized. GAO’s past work has shown that changes after finalizing design can increase costs or delay schedules.

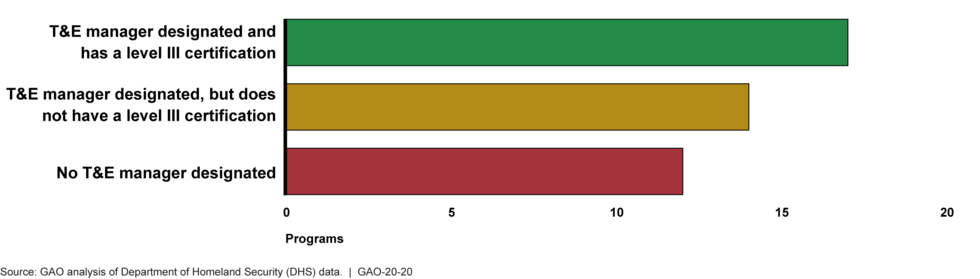

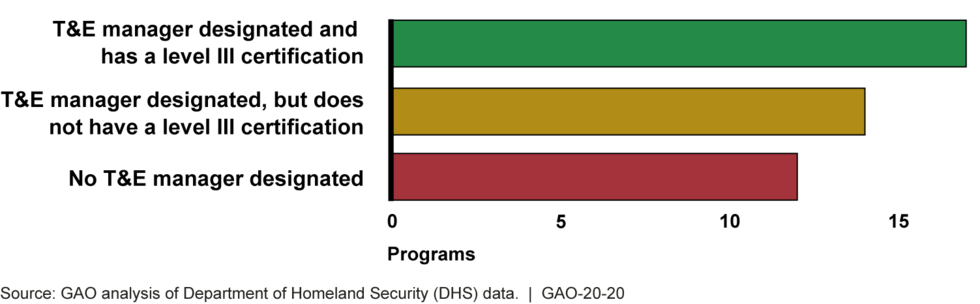

DHS faces challenges with its T&E workforce to effectively provide oversight. As shown in the figure, GAO determined that most programs do not have a level III certified T&E manager.

Status of Certified Test and Evaluation (T&E) Manager Designations Reported by DHS Major Acquisition Programs GAO Reviewed, as of March 2019

OTE also compiles data to monitor programs and the status of T&E managers, but GAO found that OTE’s data were unreliable. Specifically, OTE had inaccurate data for about half of the programs reviewed. Establishing a process for collecting and maintaining reliable data can improve OTE’s ability to accurately track programs’ T&E managers. Further, DHS has expanded OTE’s responsibilities for T&E oversight in recent years. However, OTE officials said executing these responsibilities has been difficult because DHS has not authorized changes to its federal workforce since 2014. These officials added that they have had to prioritize their oversight efforts to programs actively engaged in testing and, as such, are unable to assist programs that are early in the acquisition life cycle. By assessing OTE’s workforce, DHS can take steps to ascertain the extent to which OTE has the number of staff with the necessary skills to fulfill the full scope of its oversight responsibilities.

Why GAO Did This Study

DHS invests several billion dollars in major acquisition programs each year to support its many missions. Conducting T&E of program capabilities is a critical aspect of DHS’s acquisition process to ensure systems work as intended before being delivered to end users, such as Border Patrol agents.

GAO was asked to review DHS’s T&E activities for major acquisition programs. This report examines, among other objectives, the extent to which DHS has (1) assessed programs’ test results and used this information to make acquisition decisions; (2) policies and guidance that reflect key T&E practices; and (3) a workforce to effectively oversee programs’ T&E activities.

GAO reviewed OTE’s assessments of program test results and acquisition decision memorandums. GAO assessed DHS’s policies and guidance against key T&E practices developed by GAO for the purpose of this report. GAO also reviewed data on the T&E workforce that provides oversight at the program and headquarters levels, as well as met with OTE and other relevant DHS officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations, including that DHS revise its guidance to fully meet GAO’s key T&E practice to demonstrate that subsystems work together prior to finalizing a system’s design; establish a process for collecting and maintaining reliable data on programs’ T&E managers; and assess OTE’s workforce. DHS concurred with GAO’s recommendations.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Executive Action

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following five recommendations to DHS. Specifically, that the Secretary for Homeland Security should direct:

| Number | Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Homeland Security | The Director of OTE to revise T&E policy or guidance as necessary to fully meet the key practice for programs to test that components and subsystems work together as a system in a controlled setting before finalizing a system’s design. (Recommendation 1) |

| 2 | Department of Homeland Security | The Director of OTE, in coordination with OCPO, to develop an assessment process—including establishing performance measures—to help ensure T&E training achieves desired results. (Recommendation 2) |

| 3 | Department of Homeland Security | The Director of OTE to revise T&E policy or guidance as necessary to specify when in the acquisition life cycle a major acquisition program manager should designate a level III certified T&E manager. (Recommendation 3) |

| 4 | Department of Homeland Security | The Director of OTE to establish an internal control process to ensure that data collected and maintained on major acquisition programs’ T&E managers are reliable. (Recommendation 4) |

| 5 | Department of Homeland Security | The Under Secretary for Science and Technology to assess OTE’s workforce to ascertain the extent to which it has the appropriate number of staff with the necessary skills to fulfill its responsibilities. (Recommendation 5) |

Introduction

Congressional Requesters

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) plans to invest more than $7 billion in major acquisition programs each year from fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to develop capabilities in support of its many missions, including securing the nation’s borders and screening airline passengers and baggage. A critical aspect of DHS’s acquisition process is conducting test and evaluation (T&E) of these capabilities to ensure they meet technical specifications and performance requirements before being handed over to end users, such as Border Patrol agents and transportation security officers.

In June 2011, we reported on the department’s oversight of T&E activities after identifying that several programs had deployed capabilities before appropriate testing was completed.[1] Specifically, DHS had begun initiatives to address some long-standing issues. For example, DHS established T&E policies and created a T&E Council to disseminate best practices to the department’s components—such as the U.S. Coast Guard and Transportation Security Administration—and program managers who are responsible for leading individual acquisitions. However, we subsequently found that the department continued to encounter challenges. For example, through our ongoing assessments of major acquisition programs, we determined that programs deployed capabilities prior to meeting key performance requirements and that it wasn’t always clear whether programs had met key performance requirements when they were tested.[2] As a result, we recommended that DHS strengthen its T&E policies and oversight, such as by ensuring that independent assessments of programs’ test results include an evaluation of key performance requirements to better inform decisions to deploy capabilities to end users.[3] DHS concurred with our recommendations and took actions to address them. For example, DHS updated its process for assessing test results in June 2015 to require that assessments indicate whether or not programs met key performance requirements.

You requested that we review DHS’s T&E activities for major acquisition programs. This report addresses the extent to which DHS has (1) assessed programs’ test results and used this information to make acquisition decisions, such as whether to move forward with the program; (2) policies and guidance that reflect key T&E practices; (3) T&E training that reflects attributes of an effective training program; and (4) a workforce to effectively oversee programs’ T&E activities.

To determine the extent to which DHS has assessed programs’ test results and used this information to make acquisition decisions, we reviewed the letters of assessment the Director of the Office of Test and Evaluation (OTE) issued from August 2010—when the first letter was issued—through December 2018. We analyzed these documents to determine whether the assessments were favorable or unfavorable based on the Director’s ratings of programs’ test results. We also reviewed acquisition decision memorandums issued after the test events to determine the extent to which the Director of OTE’s letters of assessment factored into DHS leadership’s acquisition decisions, such as whether to let the program continue as planned, to direct a change, or to require any further action items (such as additional testing).

To determine the extent to which DHS has policies and guidance that reflect key T&E practices, we compared OTE’s policies and guidance to key practices we developed for the purpose of this report. To develop our list of T&E practices, we (1) reviewed relevant reports previously issued by GAO and other entities, including other government agencies and third-party organizations; (2) developed a list of key practices based on common themes we identified across the reports we reviewed; and (3) shared the list with internal subject matter experts and OTE to obtain their input. We then reviewed the policies and guidance developed by OTE that were issued between May 2017 and January 2019 to assess the extent to which they reflected the T&E practices.

To determine the extent to which DHS has T&E training that reflects attributes of an effective training program, we evaluated materials related to the training and certification for the T&E career field—such as the curricula, guidance, and course catalogs—and met with OTE and DHS officials responsible for implementing the materials. We also attended several training courses to improve our understanding of the material and observe how it was presented to students. We then compared the training and certification materials against GAO’s 2004 guide for assessing federal government training efforts to assess the extent to which they reflected attributes of effective training and development programs.[4]

To determine the extent to which DHS has a workforce to effectively oversee programs’ T&E activities, we reviewed information on T&E personnel at both the program and headquarters levels. At the program level, we reviewed data related to T&E managers. These managers are the only testing position prescribed across all major acquisition programs by OTE policy. The acquisition programs in our review reflect all active major acquisition programs that were subject to OTE oversight on DHS’s April 2018 Major Acquisition Oversight List, which was the most current list at the time we scoped our review. We developed a questionnaire to collect data from programs on their T&E managers, such as names and certification levels, and used these data to (1) determine how many programs had a certified T&E manager, and (2) verify similar data collected and maintained by OTE. We identified weaknesses with OTE’s data that affected the data’s reliability, which we discuss in the report. At the headquarters level, we reviewed documents related to OTE’s workforce—such as the office’s delegation of responsibilities from DHS leadership, organizational charts, and contracts for technical support and other services—and spoke with OTE officials. Appendix I provides detailed information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2018 to October 2019 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DHS Acquisition Life Cycle and Purpose of T&E

DHS policies for managing its major acquisition programs are primarily set forth in its Acquisition Management Directive 102-01 and Acquisition Management Instruction 102-01-001.[5] These policies outline an acquisition life cycle that includes a series of predetermined milestones—known as acquisition decision events (ADE)—at which the acquisition decision authority reviews a program to assess whether it is ready to proceed to the next phase of the acquisition life cycle (see figure 1 below). DHS’s Under Secretary for Management serves as the acquisition decision authority for the department’s major acquisition programs, those with life-cycle cost estimates of $300 million or greater.

The primary purpose of T&E is to provide timely, accurate information to managers, decision makers, and other stakeholders to reduce programmatic, financial, schedule, and performance risks. DHS programs conduct T&E as they proceed through the acquisition life cycle by gradually moving from developmental testing to operational testing, as described below.

- Developmental testing is used to assist systems engineering design and the maturation of products and manufacturing processes, among other things.[6] This type of testing is typically conducted by contractors in controlled environments, such as laboratories, and includes engineering-type tests used to verify that design risks are minimized and substantiate achievement of contract technical performance. Program managers are primarily responsible for planning and monitoring developmental testing.

- Operational testing is a field test used to identify whether a system can perform as required in a realistic environment against realistic threats.[7] This type of testing must be conducted by actual users and is typically planned and managed by an operational test agent. Operational test agents may be another government agency, a contractor, or within the DHS component developing the capability, but must be independent of the developer to present credible, objective, and unbiased conclusions. For example, the Navy’s Operational Test and Evaluation Force serves as the operational test agent for several Coast Guard programs.

Figure 2 depicts the progression of T&E activities within DHS’s acquisition life cycle.

While developmental and operational testing are often viewed as separate and distinct phases, our work has shown that T&E of major acquisition programs should be conducted on a continuum in which the realism of test objects and environments mature with the pace of product development.[8] For example, DHS programs may conduct operational assessments as they transition from developmental testing to operational testing. According to DHS, operational assessments focus on developmental efforts because they test systems that are not production representative. However, these assessments are conducted by the operational test agent and may involve end users. The results of operational assessments help to identify programmatic voids, risk areas, and the adequacy of requirements, as well as whether the system is ready for operational testing.

If programs execute T&E across the continuum as our work suggests, and use test results to inform subsequent activities, programs increase the likelihood of demonstrating system capabilities as development progresses. For example, failures during developmental testing may not be considered negative, since results can help identify problems early when they are less expensive and easier to fix. If problems are addressed, programs should have a high degree of confidence that they will successfully achieve key performance requirements during operational tests.

T&E Oversight

Within the Science and Technology Directorate, OTE has primary responsibility for T&E across DHS.[9] The office is led by a Director and organized into portfolios that align with its role and DHS’s missions. Each portfolio is led by a Deputy Director whose staff includes Test Area Managers who are assigned to specific major acquisition programs. Figure 3 depicts OTE’s structure and describes each portfolio.

The office’s primary duties include developing policies and guidance that describe T&E processes for the department’s major acquisition programs, overseeing major acquisition programs’ T&E activities, and advising on certification standards for the department’s T&E workforce. These duties include:

- Reviewing and approving test plans. The Director of OTE reviews and approves T&E master plans, which document the overarching T&E approach for the acquisition program and describes the developmental and operational testing needed to assess a system’s performance. Under DHS’s May 2019 update to its acquisition management instruction, programs are now required to submit an initial T&E master plan at ADE 2A compared to ADE 2B under the prior instruction. The Director of OTE also reviews and approves programs’ plans for individual operational test events.

- Approving operational test agents. The Director of OTE approves the operational test agent for major acquisition programs based on a set of criteria, which includes an evaluation of the operational test agent’s independence and experience, among other things.

- Providing an independent assessment of test results. The Director of OTE issues a letter of assessment that communicates an appraisal of the adequacy of an operational test prior to ADE 2C, ADE 3, and other major acquisition decisions as appropriate. The letter provides an assessment of operational effectiveness, suitability, and cyber resiliency, as well as any further independent analysis.[10]

- Determining certification standards. The Director of OTE advises DHS leadership on certification requirements for the department’s T&E career field, which consists of three levels that account for education, training, and experience: level I (basic), level II (intermediate), and level III (advanced). Each level requires students to complete a certain set of training courses, including at least one core T&E course, as well as courses related to other relevant disciplines, such as systems engineering.

- Advising DHS leadership. The Director of OTE serves as a member of the Acquisition Review Board, which reviews major acquisition programs for proper management, oversight, and accountability at ADEs and other meetings, as needed. The board is chaired by the acquisition decision authority or a designee, and consists of individuals who manage DHS’s missions, objectives, resources, and contracts, among other things. The Director of OTE is the principal adviser on major acquisition programs’ T&E progress and system performance.

Other bodies and senior officials that support OTE in carrying out its responsibilities, include:

- The Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management (PARM) is responsible for DHS’s overall acquisition governance process and supports the Acquisition Review Board. The Executive Director of PARM reports directly to the Under Secretary for Management. PARM develops and updates program management policies and practices, reviews major programs, provides guidance for workforce planning activities, supports program managers, and collects program performance data.

- The Office of Chief Procurement Officer (OCPO) and Homeland Security Acquisition Institute (HSAI) have primary responsibility within the department for the training and certification of all acquisition workforce disciplines, including T&E. OCPO establishes policies and procedures for the effective management (including accession, education, training, career development, and performance incentives) of the department’s acquisition workforce. HSAI develops and delivers training to the acquisition workforce, and oversees certification requirements, among other things.

- The T&E Council is co-chaired by the Director of OTE and the Executive Director of PARM. The council is intended to promote T&E best practices, lessons learned, and consistent T&E policy, processes, and guidance to support DHS acquisition programs. Membership includes personnel from across the DHS components and other offices, such as the Joint Requirements Council.[11]

- T&E Working Integrated Product Team supports the T&E Council. It serves as a forum and clearinghouse for crosscutting joint component initiatives, lessons learned, and issues of mutual interest and concern. This team provides recommendations to the council to guide decisions related to T&E initiatives and workforce, among other topics.

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

- DHS Has Assessed Programs’ Test Results and Used This Information to Approve Acquisition Decisions

- DHS’s Test and Evaluation Policies and Guidance Generally Reflect Key Practices

- DHS’s Test and Evaluation Training Reflects Most Attributes of an Effective Training Program but DHS Has Not Fully Assessed Its Benefits

- Most Programs Do Not Have a Certified Test and Evaluation Manager and Headquarters’ Workforce Unable to Fully Meet Oversight Responsibilities

DHS Has Assessed Programs’ Test Results and Used This Information to Approve Acquisition Decisions

Consistent with DHS’s acquisition policy, the Director of OTE has independently assessed major acquisition programs’ operational test results to inform acquisition decisions. Of the 49 independent assessments issued from August 2010 through December 2018, 29 were favorable and 20 were unfavorable. The proportion of favorable assessments has changed over time, in part, because programs have retested to verify corrections of previously identified deficiencies. Although the Director of OTE began assessing programs’ cyber resiliency in July 2014, few programs had conducted such testing as of December 2018, thereby limiting DHS’s insight into system vulnerabilities. OTE is taking steps to enhance programs’ capacity to conduct cyber resilience testing. DHS leadership generally used the Director of OTE’s assessments in making acquisition decisions. Programs were usually approved to progress through the acquisition life cycle, but DHS leadership frequently placed conditions on these approvals.

Assessments Provide Ratings on Effectiveness and Suitability, but Few Provide Ratings on Cyber Resiliency

Effectiveness and Suitability

From August 2010 through December 2018, the Director of OTE issued 49 letters of assessment that rated programs’ operational effectiveness and suitability.[12] We found that 29 of these assessments were favorable—meaning the Director of OTE rated program capabilities as (a) operationally effective or effective with limitations and (b) operationally suitable or suitable with limitations. The remaining 20 assessments were unfavorable—meaning the Director of OTE rated program capabilities as not operationally effective or suitable, or testing was inadequate. Figure 4 summarizes the Director of OTE’s ratings by component and appendix II provides more details on each letter of assessment.

| Director of OTE Operational Effectiveness and Suitability Ratings

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security documents. | GAO-20-20 |

Programs received unfavorable ratings for various reasons. In some cases, all requirements were not tested, either due to test circumstances or because they were intentionally deferred to later testing. In other cases, testing revealed that the programs did not meet requirements. Programs most frequently failed to meet the requirement for whether the system was operational when needed (known as operational availability) or it experienced critical failures more frequently than anticipated, or both.

The causes of these failures varied by program and were not always attributable to the system itself. For example, the Coast Guard’s Fast Response Cutter failed to meet its operational availability requirement in August 2013 because of issues with its main diesel engine. In contrast, deficiencies found with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Integrated Public Alert and Warning System in July 2014 were traced to infrastructure support issues with DHS and FEMA’s information technology that were external to the program.[13] Regardless of the cause, these types of failures affect when and how long a system can be reliably used by end users to complete their mission. They also require more frequent maintenance to diagnose and correct system issues, which increases program costs.

In April 2017, we reported that another reason programs failed to meet requirements during testing was because the requirements were either not written in a way that they could be tested or the desired threshold level was unachievable.[14] For example, the Director of OTE rated one of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) passenger screening technologies as not effective in December 2016 because it failed to meet the requirement for how many passengers it could screen in an hour. The program subsequently revised the requirement to focus on the number of items screened per hour rather than passengers. In September 2018, the Director of OTE issued a memorandum confirming that the technology met the revised requirement based on a reassessment of the test data against the new definition.

Almost half (22 of 49) of the letters of assessment with ratings issued by the Director of OTE from August 2010 through December 2018 were for TSA’s passenger and baggage screening programs. These programs acquire multiple types of technologies from various vendors and each vendor’s technology must demonstrate it meets defined requirements before deployment. Of the 22 screening technologies that were operationally tested and assessed by the Director of OTE, only 10 received favorable ratings. In December 2015, we reported that immature technologies submitted by vendors was a key driver of testing failures for TSA screening equipment.[15] This was because immature technologies often experience multiple failures during testing and require multiple retests, which also leads to increased testing costs and program schedule delays since vendors need time to fix deficiencies between tests. TSA primarily planned to address this challenge by instituting a third-party testing strategy through which a third-party tester would help ensure systems are mature prior to entering TSA’s T&E process. We found that TSA had begun implementing its third-party testing strategy despite not finalizing key aspects, such as a process for approving or monitoring third-party testers or how often they would need to be recertified. We recommended TSA finalize all aspects of its strategy before implementing further third-party testing requirements for vendors to enter testing. TSA concurred with the recommendation and updated its guidance in January 2018 to ensure vendor-provided information (such as third-party test data) is sufficient to demonstrate system readiness to enter the TSA T&E process.

The proportion of favorable assessments issued by the Director of OTE has changed over time (see figure 5). For example, the proportion of favorable assessments is higher from fiscal year 2016 to 2019 (15 of 18) than from fiscal year 2012 to 2015 (10 of 25).

This change is, in part, because programs conducted follow-on operational testing to verify deferred requirements or corrections of previously identified deficiencies. Specifically, about half of the assessments (7 of 15) with favorable ratings in fiscal year 2016 or later were for programs that had previously received unfavorable ratings. For example, the Director of OTE rated the Fast Response Cutter as operationally effective and suitable in February 2017 after the program conducted additional operational testing to verify it had resolved the severe deficiency related to its main diesel engines, among other things. In addition, the Director of OTE rated a release of the Homeland Security Information Network as not suitable in December 2014 because of increased data transfer delays and unplanned outages during high system use. The Director of OTE subsequently rated the system operationally suitable in January 2016 after operational testing of the program’s full capabilities.

Retesting is not unusual, even when programs receive favorable ratings, because T&E inevitably leads to learning about system risks and areas for improvement. However, as previously discussed, the evolutionary nature of T&E encourages developmental testing to reduce risk so that programs have a higher degree of confidence that they will successfully achieve key performance requirements before initiating operational testing.

The ratings of DHS’s operational test results discussed above are comparable to those experienced by the Department of Defense (DOD) in the early 2000s. For example, the Defense Science Board initiated a study in 2007 after identifying a dramatic increase in the number of DOD systems being rated not operationally suitable from 2001 to 2006.[16] The study primarily attributed these ratings to shortfalls with system reliability and a reduction of experienced T&E personnel to perform oversight of developmental testing performed by contractors, among other things. For its part, OTE has initiated efforts to address similar issues and increase the emphasis of T&E earlier in the DHS acquisition life cycle by updating its policies and guidance and improving training for test personnel in calendar year 2017—efforts that we assess later in this report.

Cyber Resilience

While it is important that systems work when needed, cyberattacks have the potential to prevent them from doing so. Cyberattacks can target any system that is dependent on software, potentially leading to an inability for end users to complete missions or even loss of life.

The Director of OTE began assessing programs’ operational resilience to cyberattacks in July 2014, but few programs have conducted cyber resilience testing. As of December 2018, only five programs had conducted this testing to support an assessment by the Director of OTE and only two of these programs were rated as operationally cyber resilient. The remaining three programs were rated not operationally cyber resilient because system security tools did not detect intrusions and testers found significant system or network vulnerabilities, among other reasons. Appendix II provides more details on each letter of assessment.

| Director of OTE Cyber Resilience Ratings

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security documents. | GAO-20-20 |

Programs that did not conduct cyber resilience testing to support a rating by the Director of OTE have not done so primarily because it was not a consideration at the time that they initiated development, some as early as fiscal year 2002. As a result, these programs did not have operational requirements to guide the design, development, and testing of cyber resiliency into systems. In October 2015, the Director of OTE issued a memorandum that established an expectation that all operational testing include an assessment of cybersecurity since real-world events demonstrated that end users would be using systems in an environment where cyber threats would attempt to deny or disrupt their ability to carry out missions. The memorandum included procedures for planning and reporting on cyber resilience testing. For example, it directed programs to conduct a threat assessment to identify current cyber threats and testers to work with user representatives as needed to develop cybersecurity measures.

Programs’ compliance with this guidance has been slow, in part, because of the time needed to adequately plan and coordinate testing. For example, in August 2018, the Coast Guard completed a nearly 3-year effort to conduct cyber resilience testing on the National Security Cutter—the first Coast Guard asset to undergo this type of testing—as a part of follow-on operational testing.[17] The Coast Guard initially planned to conduct cyber resilience testing in fiscal year 2017, but these plans were delayed by a year because of a change in operational schedules for fielded cutters, among other things. Testing was conducted by the Navy with support from the Sandia National Lab and other DOD entities, and consisted of cooperative and adversarial assessments. The Director of OTE identified the effort as setting a standard for assessing DHS’s major acquisition programs’ cyber resilience.[18]

Although we and others have warned of cyber risks since the 1990s, determining how to build, test, and maintain cyber resilient systems is a government-wide challenge that is not unique to DHS.[19] In October 2018, we reported that DOD was just beginning to grapple with the scale of its cyber vulnerabilities because, until recently, it did not prioritize weapon systems cybersecurity.[20] We found that DOD routinely identified mission-critical cyber vulnerabilities through operational testing, but that these likely represent a fraction of the total vulnerabilities because testing did not reflect the full range of threats and not all programs have conducted cyber resilience testing.

Since few DHS major acquisition programs have conducted cyber resilience testing, the department also has limited insight into the cyber vulnerabilities of its acquired systems. Although programs are beginning to take steps to conduct cyber resilience testing, we reported in October 2018 that doing so late in the development cycle or after a system has been deployed is more costly and difficult than designing cyber resilience testing into development of the system from the beginning.[21] For example, Navy testers conducting the cyber resilience testing on the National Security Cutter after it was already operational told us there were certain aspects of the ship they could not test because it could compromise the safety of the crew or cause irreparable damage.

Some programs—including ones initiated after the Director of OTE’s 2015 memorandum—continue to defer cyber resilience testing. This approach limits DHS’s ability to understand and mitigate vulnerabilities that could be exploited by cyber threats. For example, officials from Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Biometric Entry-Exit Program, which was initiated in June 2017, told us that they plan to conduct cyber resilience testing after achieving ADE 3 because they needed additional time to develop a more rigorous test plan in coordination with OTE.[22] The program plans to conduct its ADE 3 review in September 2019, but had already deployed capabilities to airports by December 2018.

OTE is taking additional steps to enhance programs’ capacity to conduct cyber resilience testing. For example, in fiscal year 2018, OTE developed a training course and released supplemental guidance focused on planning and performing cyber resilience testing. OTE also awarded a contract to the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory for support, which included performing cyber resiliency testing on DHS major acquisition information technology programs. The results of this testing are intended to further OTE’s ability to develop comprehensive, department-wide policy and procedures. Since DHS is still implementing cyber resilience testing and developing appropriate policies and procedures, we will continue to track the department’s progress through our ongoing assessments of major acquisition programs.[23]

DHS Leadership Generally Used Assessments to Make Informed Acquisition Decisions

Consistent with DHS’s acquisition policy, the Director of OTE’s letters of assessment informed DHS leadership’s acquisition decisions. We reviewed the 38 acquisition decision memorandums issued after the 49 operational test events for which the Director of OTE provided a letter of assessment with ratings.[24] Programs generally received approval to progress through the acquisition life cycle based on the Director of OTE’s ratings as one of the factors considered in decision-making. In more than half of the cases we reviewed (26 of 38), DHS leadership placed conditions on its approval or directed programs to address issues discovered during testing. For example:

- In March 2011, DHS leadership granted ADE 2C approval with conditions for an explosives detection system acquired by TSA’s Electronic Baggage Screening Program. This system received an unfavorable assessment from the Director of OTE primarily because it had not been used enough during operational testing to support a rating of operational effectiveness or suitability. DHS leadership limited TSA’s procurement to 28 systems and required the program to conduct additional operational testing and receive another letter of assessment from the Director of OTE before it could procure more systems. The program completed follow-on operational testing of the system and, in September 2011, the Director of OTE rated it operationally effective and suitable with limitations.

- In January 2015, DHS leadership granted CBP’s Multi-role Enforcement Aircraft program conditional approval to acquire two aircraft. The Director of OTE could not assess operational suitability because testing was limited and did not include testing of availability, reliability, and maintainability, among other things. Leadership’s approval was contingent on the program completing a number of actions, including preparing a plan to correct issues identified during the operational test and providing a status of corrections to the Director of OTE. The program conducted additional operational testing in July 2015, which received favorable results. Although test data showed the aircraft’s availability was lower than required, the Director of OTE rated the aircraft as suitable with limitations because the availability rating had improved after testing concluded.

In our review of acquisition decision memorandums, we found a case where a program received an unfavorable assessment from the Director of OTE and DHS leadership did not let the program proceed as planned. The FEMA Logistics Supply Chain Management System conducted initial operational testing in calendar year 2013, which the Director of OTE determined was inadequate to support ratings for operational effectiveness and suitability.[25] In response to this and other factors, DHS leadership paused the program in April 2014 and directed officials to re-evaluate its development strategy. For example, the program was directed to (1) revisit its requirements and identify capability gaps based on the operational test results and the Director of OTE’s letter of assessment; and (2) conduct an analysis of alternatives for addressing identified capability gaps.

In March 2016, DHS leadership approved this program to resume development after completing these actions, but also required the program to take additional steps to address recommendations made by the Director of OTE. For example, the program was required to select a new operational test agent and update its T&E master plan to address issues identified in the letter of assessment before conducting additional operational testing. The program completed follow-on operational testing in June 2018, which the Director of OTE rated as operationally effective and suitable with limitations because the system did not have an off-site backup server to quickly restore operations in the event of a catastrophic failure of the primary server. Based on these results, DHS leadership did not approve the program’s ADE 3 or acknowledgement of full operational capability in February 2019, and directed the program to implement a backup server solution by the end of August 2019.

DHS’s Test and Evaluation Policies and Guidance Generally Reflect Key Practices

We assessed the T&E policies and guidance DHS issued between May 2017 and January 2019 and found that they generally reflect key practices. For almost two decades, we have reported that successful acquisitions engage in a continuous cycle of improvement by conducting T&E throughout development and incorporating lessons learned. For example, in July 2000, we examined the practices that private sector entities used to validate that a product works as intended and determined that leading commercial firms viewed T&E as a constructive tool throughout product development.[26] Specifically, we found that leading firms ensure that (1) the right validation events—tests, simulations, and other means for demonstrating product maturity—occur at the right times; (2) each validation event produces quality results; and (3) the knowledge gained from an event is used to improve the product. By holding challenging tests early, firms exposed weaknesses in a product’s design and limited design changes late in the development process when it is harder and more expensive to address issues.

Based on this and our other work, as well as a review of related third-party and other government entities’ reports, we developed a list of key T&E practices that consist of 17 elements that contribute to successful acquisition outcomes.[27] The list of practices we developed is not exhaustive and is intended to be at a level high enough so that they may be applied to assess various types of acquisitions—including both hardware and software—regardless of the developer or development approach.

We used these key practices to assess DHS’s T&E policies and guidance since they similarly provide a high-level framework for outlining what is expected of major programs throughout the acquisition life cycle. In May 2009, DHS issued its first directive requiring major acquisition programs to ensure adequate and timely T&E is performed to support informed acquisition decision-making and outlining oversight of those activities. OTE has since updated the directive and developed additional guidance to increase the emphasis of T&E earlier in the acquisition life cycle and to address issues programs have encountered during operational testing, among other things. For example, OTE updated the directive in May 2017 and developed an accompanying instruction in July 2017 that clarified the roles and responsibilities for certain T&E activities within the department and at certain acquisition milestones. OTE also released supplemental guidance on more detailed topics, such as incorporating T&E into programs’ contracts and evaluating threats to ensure testing reflects realistic scenarios.

Table 1 summarizes our assessment of OTE’s policies and guidance against our key T&E practice areas and elements.

Note: Appendix I presents a detailed description of how we developed our key practices and how we assessed DHS’s policies.

As reflected in the table, OTE’s policies and guidance met the elements of our key T&E practice areas in nearly all cases. For example:

- Develop a test strategy to demonstrate program requirements. OTE’s policies require programs to document a test strategy for verifying program requirements in a T&E master plan, which supplemental guidance indicates should outline opportunities for integrated testing, incorporate measures of success, and identify any potential limitations, among other things. Integrated testing is intended to increase efficiencies by collecting data through one test event that supports the evaluation needs of multiple stakeholders, such as developmental testers and operational testers. OTE also enhanced its guidance on how programs should plan for early reliability testing because it considers this metric to have the greatest effect on system performance, which includes how frequently the system fails. This may help programs address reliability problems before initiating operational testing which, as we previously mentioned, is a reason DHS’s major acquisition programs frequently received unfavorable test ratings from the Director of OTE. OTE’s guidance also states that a program’s T&E master plan should be based on credible threat information to ensure testing is conducted under realistic scenarios. In July 2018, OTE released additional guidance focused on cyber threats that provides information on how programs can identify potential threats, evaluate their impact, and document these threats.

- Identify and secure resources to conduct testing. OTE’s July 2017 instruction directs program managers of major acquisitions to designate a T&E manager who is required to be level III certified in the T&E career field. The T&E manager is to coordinate the planning, management, and oversight of all T&E activities; lead the development of a program’s T&E master plan; and coordinate test resources, among other duties. We assess DHS’s implementation of the certified T&E manager requirement later in this report.

- Conduct testing throughout the acquisition life cycle. OTE’s guidance states that programs generally should conduct a review to assess component or subsystem test results prior to beginning system integration and comprehensive developmental testing. In addition, prior to full deployment (e.g., ADE 3), OTE’s instruction directs programs to conduct operational testing of the complete system in a realistic environment.

- Use test results to inform decisions. OTE’s updated directive added a phase of independent testing for any program that has a limited production decision (e.g., ADE 2C). This decision is optional depending on the program’s development approach. But, if conducted, the Director of OTE now issues a letter of assessment prior to ADE 2C to inform the acquisition decision authority about the program’s performance. Previously, the directive only called for the Director of OTE to issue a letter of assessment prior to ADE 3 decisions.

We found that OTE’s guidance only partially met the key practice element to test that components and subsystems work together as a system in a controlled setting before finalizing a system’s design. OTE’s guidance instructs programs to conduct integration testing on components and subsystems. However, it calls for this type of testing to occur after the critical design review, which is when the design is finalized. This increases the risk that programs will need to make changes to system components after the critical design review, which our past work has shown can cause cost increases or schedule delays.[28] OTE officials acknowledged that the current T&E guidance could be clearer on when integration testing should occur in the development process. These officials told us that they intend to adjust their policies and guidance, which they are updating to align with the May 2019 acquisition management instruction. Until OTE updates this guidance, programs could experience costly design changes resulting from conducting integration testing late in the acquisition life cycle.

DHS’s Test and Evaluation Training Reflects Most Attributes of an Effective Training Program but DHS Has Not Fully Assessed Its Benefits

We found that DHS’s T&E training reflects most attributes of an effective federal training program, but does not fully reflect attributes pertaining to assessing the benefits of training. In March 2004, we issued a guide for assessing federal training programs that breaks the training and development process into four broad, interrelated components—(1) planning and front-end analysis, (2) design and development, (3) implementation, and (4) evaluation—and identifies attributes of effective training and development programs that should be present in each of the components.[29] These components are not mutually exclusive and encompass attributes that may be related. For example, each component includes attributes related to assessing training and development benefits rather than these attributes being confined solely to the evaluation component.

OTE officials told us they assumed responsibility for providing instructors and for updating the T&E training materials from the Office of Chief Procurement Officer (OCPO) and Homeland Security Acquisition Institute (HSAI) in 2017. OTE worked with OCPO and HSAI to implement changes intended to ensure the training met workforce needs and reflected current policies and guidance. For example, OTE updated the content for each of the certification level core T&E courses—which were originally based on DOD’s T&E training—to reflect DHS’s acquisition process, among other things.

As summarized in figure 6, OTE’s T&E training, particularly the core T&E courses, either met or partially met the relevant attributes from our guide. A more detailed description of our assessment methodology is presented in appendix I.

OTE’s T&E training reflects attributes of effective training in each of the four components of the training and development process, such as:

- OTE coordinated with OCPO and HSAI to determine the skills and competencies needed for an effective T&E workforce, which served as the foundation for developing the learning objectives and content for the core T&E courses.

- OTE partners with HSAI to provide formal instruction for in-person courses at HSAI’s training facility or online courses through the Defense Acquisition University. OTE supplements these courses with informal training opportunities, such as seminars and workshops that are tailored to meet component and program needs or focus on specific subject areas. For example, OTE has sponsored seminars dedicated to writing an effective test strategy and facilitating a table-top exercise to inform a program’s cyber resilience testing. OTE also hosts an annual symposium for T&E managers to facilitate knowledge sharing across the department.

- OTE solicits and incorporates stakeholder feedback from the T&E Council and T&E Working Integrated Product Team into the planning, design, and implementation of its training efforts to ensure that the training addresses DHS’s workforce needs. Primarily, OTE uses these groups to review existing course content, determine the frequency of course offerings, and identify topics for new courses. For example, OTE developed a course specifically for operational test agent leads after the T&E Working Integrated Product Team identified a gap in training for those who plan and conduct operational testing for DHS’s major acquisition programs. As of August 2018, the Director of OTE requires the operational test agent lead for major acquisition programs to complete this course prior to commencing operational testing.

- OTE uses a service contract to fulfill its need for classroom instructors for the core T&E courses. According to OTE officials, this allows them to provide full-time instructors with T&E experience, which provides consistency across the trainings. OTE’s Deputy Directors and Test Area Managers also present on certain topics during the core T&E courses to provide knowledgeable expertise. In addition, OTE has secured other experts to serve as guest speakers at various trainings, seminars, and workshops, as well as to assist programs with specific needs. For example, OTE partnered with the Air Force Institute of Technology to establish the DHS Scientific Test and Analysis Techniques Center of Excellence to sponsor workshops and a module in the intermediate core T&E course dedicated to increasing the use of statistics and other tools to support T&E, and to provide select acquisition programs assistance with developing an analytical approach and test design.

The six attributes that OTE’s T&E training partially reflects are all related to assessing the benefits of the training. OTE uses stakeholder feedback from the T&E Working Integrated Product Team and student feedback from course evaluations to improve training content and delivery. However, OTE has not yet taken steps to assess whether the training offered has led to improved organizational results. For example, OTE has identified better test documentation and more favorable operational test results as desired outcomes. But it has not established performance measures to determine how the training may contribute to achieving these outcomes. According to officials, OTE has not yet assessed its training because it prioritized developing and delivering courses since assuming responsibility in 2017. Additionally, OTE has spent approximately 30 percent of its annual budget on training since 2017 and reviews its proposed training expenses annually, but has not evaluated its return on this investment. OTE officials acknowledged that establishing performance measures would be beneficial, but said it would be challenging to reliably assess against those measures. Nevertheless, by developing an assessment process that includes performance measures for T&E training, OTE can better ensure that it is offering effective training that addresses training objectives and achieves desired results.

Most Programs Do Not Have a Certified Test and Evaluation Manager and Headquarters’ Workforce Unable to Fully Meet Oversight Responsibilities

We found that DHS faces challenges with its T&E workforce to effectively provide oversight at the program and headquarters levels. Specifically, most programs do not have a level III certified T&E manager, despite the requirement for program managers to designate one for major programs. Additionally, OTE’s data for monitoring whether programs have a certified T&E manager are unreliable. Finally, DHS has expanded OTE’s responsibilities for T&E oversight in recent years, but has not assessed whether OTE has the workforce needed to fully execute these responsibilities. OTE officials said they have had to prioritize their oversight efforts, making it difficult for the office to fully execute its responsibilities across the range of DHS major acquisition programs.

Most Programs Lack a Certified Test and Evaluation Manager and DHS Policy Unclear

As previously mentioned, OTE’s July 2017 instruction directs program managers of major acquisitions to designate a T&E manager who is required to be level III certified in the T&E career field. As of March 2019, only 17 of 43 major acquisition programs we reviewed reported to us that they have a level III certified T&E manager (see figure 7).

Officials from select programs that have designated a T&E manager who does not yet meet the certification requirement indicated they are working toward achieving level III certification. For example, officials from the CBP Non-Intrusive Inspection Systems program reported that the designated T&E manager was unable to complete his final course to achieve level III certification because it was cancelled as a result of the partial government shutdown in January 2019.

Officials from the 12 programs without a designated T&E manager provided various reasons for not having one, including:

- The position is vacant because the program office reorganized or the designated T&E manager left the agency. For example, officials from FEMA’s Grants Management Modernization program reported that the designated T&E manager moved to another agency so the role is being temporarily filled by service contractor personnel with prior T&E experience until they can hire a qualified, permanent replacement.

- The program manager determined the program did not need a T&E manager based on its development approach. For example, officials from CBP’s Automated Commercial Environment program reported that the program manager did not designate a T&E manager because of the program’s shift to agile software development.[30]

- The program manager determined the program was exempt from the certified T&E manager requirement based on where the program was in the acquisition life cycle. For example, officials from Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s U.S. Code, Title 8, Aliens and Nationality program said they were too early in the acquisition life cycle to designate a T&E manager. On the other hand, officials from the Coast Guard’s Nationwide Automatic Identification System program said they did not need one because they were later in the acquisition cycle, past ADE 3.

As of April 2019, OTE officials confirmed they had not exempted any program from designating a certified T&E manager.[31] OTE officials acknowledged that some programs that are past ADE 3 may not need a T&E manager depending on the program’s acquisition strategy and whether it had successfully completed testing. However, they cautioned that programs may continue to need T&E support late in the acquisition life cycle since many add capabilities after deployment and assessments against emerging cyber threats should be ongoing.

OTE officials told us they expect programs to designate a T&E manager early in the acquisition life cycle—no later than ADE 2A—to assist with developing system requirements that are measurable, testable, and achievable and establish a sound test strategy. This expectation is consistent with DHS’s May 2019 update to its acquisition management instruction, which requires programs to submit an initial T&E master plan earlier in the life cycle—at ADE 2A compared to ADE 2B under the prior instruction. OTE officials emphasized this early designation is critical for programs using agile software development because testing is conducted early and often by the various development teams. OTE officials said they communicate their expectation through direct interaction with programs and during Acquisition Review Board meetings and other forums.

However, OTE’s policy only indicates program managers should designate a T&E manager “as early as practicable.” Specifying in policy when programs should designate a T&E manager would make OTE’s expectation clear that program managers are to identify knowledgeable T&E personnel no later than ADE 2A, which is where important decisions about the program’s requirements and test strategy are now made.

Data for Monitoring Program Test and Evaluation Managers Are Unreliable

OTE internally tracks data on programs’ T&E managers, but we found the data to be unreliable. In comparing the information we compiled on T&E managers (as discussed above) against OTE’s internal data, we found that OTE had inaccurate information for about half (19 of 40) of the programs.[32] In most cases, OTE either identified a T&E manager when a program reported not having one, identified the wrong individual in the position, or identified the wrong certification level. For example, OTE identified that CBP’s Integrated Fixed Tower program had a T&E manager as of December 2018, but the program reported that the position was vacated in October 2018 and remained unfilled as of February 2019. Moreover, the individual identified by OTE as the T&E manager did not match the former T&E manager identified by the program.

OTE officials said the Deputy Directors and Test Area Managers are responsible for inputting and maintaining the data for their assigned programs in the OTE internal tracker at least quarterly or as changes occur (e.g., following an ADE or test plan approval). Service contractor personnel for OTE then perform a quarterly review for missing information and to verify the T&E manager certification levels against a list provided by HSAI.

However, OTE has not established an internal control process for ensuring the accuracy of all the data in its internal tracker. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government advises management to obtain relevant data—and evaluate the reliability of the data—in a timely manner so that the data can be used for effective monitoring.[33] By establishing an internal control process for collecting and maintaining its data, OTE can improve its ability to accurately track programs’ T&E managers.

Full Scope of Test and Evaluation Oversight Responsibilities Not Being Executed with Current Workforce

DHS has expanded OTE’s responsibilities for T&E oversight in recent years. Specifically:

- The Deputy Secretary of DHS updated the department’s delegation of authorities to the Director of OTE in June 2016. This delegation extended the Director’s oversight to include developmental testing as reflected in major acquisition programs’ T&E master plans.

- OTE officials told us in February 2019 that the senior official performing the duties of the Under Secretary for Science and Technology requested that OTE begin providing oversight of T&E activities conducted by the directorate’s research and development projects. This effort is to include developing T&E policies and procedures for research and development, as well as providing formal support to specific projects that is similar to that provided to major acquisition programs.

- As previously noted, the May 2019 update to DHS’s acquisition management instruction requires programs to submit an initial T&E master plan earlier in the life cycle. This will require OTE staff to begin engaging with programs earlier to support development and approval of this plan. ecifically, ated duties with respect to

OTE officials stated that executing the office’s expanded oversight responsibilities is difficult because the Science and Technology Directorate has not authorized changes to OTE’s federal workforce since 2014. OTE has awarded contracts for support in developing policy and guidance, facilitating trainings, and providing technical expertise in key areas—such as reliability and cybersecurity—among other things. While this expanded the capacity of the office, it also added responsibilities on OTE’s staff since it must oversee work completed by contractors.

Despite these efforts, OTE officials told us they have to prioritize support to those major acquisition programs that are of high importance to the department and actively engaged in planning or conducting operational testing. As a result, OTE is unable to fully meet the additional delegated duties for developmental testing oversight. Specifically, in April 2019, officials stated that they did not have the capacity to help shape developmental test plans, observe testing, or provide feedback on test results in the same manner that they do for operational tests. While OTE officials plan to award a service contract for conducting activities in support of research and development T&E, the management and oversight of these contracted activities will increase the administrative duties on OTE’s existing federal staff.

Workforce planning helps an organization align its human capital, both federal and contracted, with its current and emerging mission and programmatic goals. In December 2003, we identified several key principles for effective strategic workforce planning.[34] These principles include:

- Determining the critical skills and number of employees needed to achieve programmatic results;

- Identifying and developing strategies to address staffing and skills gaps; and

- Monitoring and evaluating progress toward human capital goals.

DHS did not assess OTE’s human capital before expanding the office’s oversight responsibilities. By assessing OTE’s workforce, the Science and Technology Directorate can take an important step to ensure that OTE has the appropriate number of staff with the necessary skills to fulfill the full scope of its expanded oversight responsibilities.

Conclusions

Results from the T&E of major acquisition programs provide DHS leadership with valuable information to make risk-based decisions about the development and deployment of capabilities needed to execute the department’s many missions. OTE has taken steps to increase the emphasis of T&E earlier in the acquisition life cycle by establishing policies and guidance that generally reflect key practices. However, programs are at risk of making changes late in the development process if they conduct integration testing of components and subsystems after a system’s design is finalized as OTE’s current guidance instructs.

OTE has also taken steps to build a knowledgeable workforce by updating the training for DHS’s test personnel and requiring major acquisition program managers to designate a level III certified T&E manager. However, until OTE assesses the benefits of the training, it cannot ensure it is achieving desired results. Additionally, opportunities exist for OTE to increase the number of programs that have a certified T&E manager by specifying in policy when program managers should designate a T&E manager and by collecting more reliable data.

The department has also recognized the importance of emphasizing T&E earlier in the acquisition process, as evidenced by the expansion of OTE’s role to include oversight of developmental testing and establishing T&E policies and processes for research and development. However, the Science and Technology Directorate has not assessed OTE’s workforce to understand whether the office has the human capital needed to fulfill all of its oversight responsibilities. Until it does, there is a risk that the department will not realize the benefits of OTE’s expanded oversight role.

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this product to DHS for comment. DHS’s written comments are reproduced in appendix IV. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In its comments, DHS concurred with all five recommendations and identified actions it planned to take to address them.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Acting Secretary of Homeland Security. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-4841 or makm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Marie A. Mak

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Congressional Addressees

The Honorable Cedric L. Richmond

Chairman

Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection, and Innovation

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Donald M. Payne

Chairman

Subcommittee on Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Recovery

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable J. Luis Correa

House of Representatives

The Honorable Scott Perry

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Ratcliffe

House of Representatives

Appendixes

IN THIS SECTION

- Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

- Appendix II: DHS’s Director, Office of Test and Evaluation Letters of Assessment

- Appendix III: Reports and Studies Related to Test and Evaluation

- Appendix IV: Comments from the Department of Homeland Security

- Appendix V: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

Our objectives were to determine the extent to which the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has (1) assessed programs’ test results and used this information to make acquisition decisions; (2) policies and guidance that reflect key test and evaluation (T&E) practices; (3) T&E training that reflects attributes of an effective training program; and (4) a workforce to effectively oversee programs’ T&E activities.

To determine the extent to which DHS has assessed programs’ test results and used this information to make acquisition decisions, we reviewed the letters of assessment the Director of the Office of Test and Evaluation (OTE) issued from August 2010—when the first letter was issued—through December 2018 and available acquisition decision memorandums. These memorandums are the department’s official record of acquisition management decisions made by DHS leadership. Specifically, we reviewed the letters of assessment to ascertain the Director of OTE’s ratings on programs’ operational effectiveness and suitability. We determined whether the ratings were favorable or unfavorable using the following criteria:

- Favorable—the Director of OTE rated program capabilities as (a) operationally effective or effective with limitations and (b) operationally suitable or suitable with limitations.

- Unfavorable—the Director of OTE rated program capabilities as (a) not operationally effective or suitable or (b) testing was inadequate.

We did not include the ratings on cyber resiliency in our analysis of favorable or unfavorable because the Director of OTE did not begin including these ratings in the letters of assessment until July 2014. However, we identify any cyber resiliency ratings in appendix II and present observations in the report for completeness.

We also reviewed acquisition decision memorandums issued after programs’ operational test events to determine (a) if the Director of OTE’s letters of assessment were mentioned as a factor considered in DHS leadership’s decision-making, (b) whether the memorandums directed programs to take specific actions related to T&E issues, and (c) the extent to which the decisions or assigned actions aligned with the Director of OTE’s letter of assessment ratings or recommendations. We reviewed acquisition decision memorandums issued for 38 of the 49 letters of assessment in which the Director of OTE provided ratings (78 percent), which we determined provided a reasonable basis for the findings presented in this report.[35]

To determine the extent to which DHS has policies and guidance that reflect key T&E practices, we compared OTE’s policies and guidance to key practices we developed for this purpose of this report. To develop our list of T&E practices, we reviewed our prior reports related to developing and testing major acquisitions, requirements setting, and software development. We also reviewed similar reports issued by other government agencies, as well as third-party studies on T&E processes and relevant standards. A list of the reports and studies we reviewed is provided in appendix III. We then developed a list of practices based on common themes we identified across these sources that contribute to successful acquisition outcomes. The list of T&E practices is not exhaustive and is intended to be at a level high enough so that they may be applied to assess various types of acquisitions—including both hardware and software—regardless of the developer or development approach. We shared a preliminary list of our practices with internal subject matter experts in T&E, acquisition, cybersecurity, and information technology to incorporate their input. We also discussed the list with OTE to obtain its insight.

We then reviewed the policies and guidance OTE developed that were issued between May 2017 and January 2019 to assess the extent to which they reflected our T&E practices using the following ratings:

- Met—the documents fully reflected the key practice.

- Partially met—the documents reflected some, but not all parts of the key practice.

- Not met—the documents did not reflect the key practice.

We shared our preliminary analysis of the policies and guidance with the OTE officials responsible for implementing them to discuss our findings and solicit their feedback on those key practices that were not fully reflected in the policies.

To determine the extent to which DHS has T&E training that reflects attributes of an effective training program, we evaluated materials related to the training and certification for DHS’s T&E career field against criteria we previously developed. Specifically, we reviewed the T&E career field training and certification curricula, guidance, and course catalogs, among other materials, and met with officials from OTE and the Homeland Security Acquisition Institute (HSAI) responsible for implementing the materials. We also attended several different trainings, including the intermediate and advanced core T&E courses, to improve our understanding of the material and observe how it was presented to students. We then compared the training and certification materials against our 2004 guide for assessing federal government training efforts.[36] This guide outlines four broad, interrelated components—(1) planning and front-end analysis, (2) design and development, (3) implementation, and (4) evaluation—and identifies attributes of effective training and development programs that should be present in each of the components. The guide also includes supporting characteristics to look for related to each attribute. First, we assessed the training and certification materials against the supporting characteristics for each attribute using the following ratings:

- Met—the training fully reflected the characteristic.

- Partially met—the training reflected some, but not all parts of the characteristic.

- Not met—the training did not reflect the characteristic.[37]

Second, we consolidated the ratings for all the supporting characteristics of an attribute to establish a rating for each applicable attribute. We concluded that an attribute was met if all ratings for the supporting characteristics for that attribute were met; partially met if one or more of the supporting characteristics for an attribute were partially met or a mix of met and not met; or not met if the characteristics for an attribute were all not met. For the purposes of this report, we included only those attributes we found to be applicable to the scope of our review in our overall analysis. We shared our preliminary analysis with OTE and HSAI officials to discuss our findings, identify relevant materials we had not yet accounted for, and solicit their feedback. We did not examine the appropriateness of the T&E certification itself or the content of training courses required for the T&E career field certification.

To determine the extent to which DHS has a workforce to effectively oversee programs’ T&E activities, we analyzed data on program T&E personnel collected from various sources and reviewed information related to OTE’s workforce, as described in more detail below.

- Analysis of program T&E personnel data. We reviewed data related to T&E managers, which is the only testing position prescribed across all major acquisition programs by OTE policy. We reviewed these data for all major acquisition programs that were subject to OTE oversight and between Acquisition Decision Event 1 and full operational capability on DHS’s April 2018 Major Acquisition Oversight List, which was the most current list at the time we scoped our review. We developed a questionnaire to collect data from programs on their T&E managers, including the names and certification levels of T&E managers, appointment dates, and any challenges with filing this role. We also spoke with officials from several programs during interviews conducted in coordination with our ongoing assessment of select major acquisition programs to get more clarity on program’s T&E managers, planning and execution of T&E activities, and coordination with OTE, among other things. We verified the certification levels provided to us in the questionnaires against a list provided by HSAI and determined the information reported by programs was sufficiently reliable for the purposes of identifying the number of programs that met OTE’s certified T&E manager requirement. We also compared the program questionnaire responses to OTE’s internal acquisition program trackers that include data related to programs’ T&E activities—including the names and certification levels of T&E managers—to identify discrepancies or missing data between the two sources. We also interviewed OTE officials to discuss how they collect and maintain the data in their tracker, as well as the discrepancies we identified. We identified weaknesses with OTE’s data that affected the data’s reliability, as discussed in this report.

- Review of OTE workforce information. We reviewed documents related to OTE’s workforce, including the office’s delegation of responsibilities from DHS leadership, organizational charts, and current task order issued pursuant to an indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contract for systems engineering and technical assistance. We also spoke with OTE officials about changes to—and any potential challenges in executing—the office’s role and responsibilities.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2018 to October 2019 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: DHS’s Director, Office of Test and Evaluation Letters of Assessment

◒ = operationally effective, suitable, or cyber resilient with limitations

○ = not operationally effective, suitable, or cyber resilient

— = Director was unable to rate based on the test results

n/a = not applicable

Note: The Director of OTE provides observations on programs’ progress in the letters of assessment issued for operational assessments and other developmental tests, but defers ratings until after formal operational testing is conducted.

aThe Director of OTE did not begin rating programs on cyber resiliency until July 2014.

bPrior to November 2018, CISA was known as the National Protection and Programs Directorate. We use CISA in this table to reflect the component’s current name.

cFollowing the test, the program revised the definition for the system’s throughput requirement that contributed to its effectiveness rating. On September 6, 2018, the Director of OTE issued a memorandum confirming that the system met the revised requirement based on a re-assessment of the test data against the new definition.

Appendix III: Reports and Studies Related to Test and Evaluation

Below are the reports and studies we reviewed to develop the list of key test and evaluation practices identified in this report.

CMMI Product Team. Improving Processes for Acquiring Better Products and Services. CMMI-ACQ, V1.3. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University, 2010.

Defense Business Board. Best Practices for the Business of Test and Evaluation, a report for the Secretary of Defense, DBB FY17-01. October 20, 2016.

GAO, Technology Readiness Assessment Guide, GAO-16-410G. Washington, D.C.: August 2016.

GAO, Immigration Benefits System: US Citizenship and Immigration Services Can Improve Program Management, GAO-16-467. Washington, D.C.: July 7, 2016.

GAO, Schedule Assessment Guide, GAO-16-89G. Washington, D.C.: December 2015.

GAO, Advanced Imaging Technology: TSA Needs to Assess Technical Risk Before Acquiring Enhanced Capability, GAO-14-98SU. Washington, D.C.: June 10, 2014.