Highlights

What GAO Found

- The Department of Energy could pursue less expensive disposal options of nuclear and hazardous waste, such as immobilizing waste in grout, which could help save tens of billions of dollars.

- Contracting leaders at federal agencies should use metrics measuring cost reduction or avoidance to improve the performance of their procurement organizations and potentially save billions of dollars annually.

- Congress should consider directing the Department of Health and Human Services to implement additional payment reductions for Skilled Nursing Facilities with high rates of potentially preventable hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, potentially saving hundreds of millions of dollars in Medicare costs.

- The Internal Revenue Service could improve taxpayer service and better manage refund interest payments, potentially saving $20 million or more annually, by establishing a mechanism to identify, monitor, and mitigate issues contributing to refund interest payments.

- The Social Security Administration could potentially save millions of dollars by identifying and addressing the causes for overpayments to disability beneficiaries in its Ticket to Work program.

- The Department of Defense could improve various administrative services, such as by better managing fragmentation in its food program and strengthening ongoing initiatives to reduce improper defense travel payments, potentially saving millions of dollars in those programs.

- The Department of Health and Human Services changed processes to curtail some problematic methods of determining budget neutrality and restricted the amount of unspent funds states can accrue and carry forward to expand Medicaid demonstrations, which resulted in more than $140 billion in federal savings.

- In support of the Office of Management and Budget’s Data Center Optimization Initiative, 22 federal agencies have been consolidating their data centers to improve government efficiency with related cost savings of approximately $5.7 billion.

Area name and description (Year-number links to Action Tracker) | Mission | Potential benefits (Source when financial) |

|---|---|---|

Medicare Payments by Place of Service (2016-30): Congress should consider directing the Secretary of Health and Human Services to equalize payment rates between settings for evaluation and management office visits and other services that the Secretary deems appropriate and return the associated savings to the Medicare program. | Health | Billions of dollars annually (MedPAC and Bipartisan Policy Center) |

Category Management (2021-06): The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should further its Category Management initiative to improve how agencies buy common goods and services by taking such actions as addressing agencies’ data management challenges and establishing additional performance metrics to help the federal government achieve cost savings, as well as potentially eliminate duplicative contracts. | General Government | Billions of dollars over the next 5 years (OMB and GAO) |

Disability and Unemployment Benefits (2014-08): Congress should consider passing legislation to require the Social Security Administration to offset Disability Insurance benefits for any Unemployment Insurance benefits received in the same period. | Income Security | $2.2 billion over 10 years (OMB) |

Navy Shipbuilding (2017-18): The U.S. Navy could achieve cost savings by improving its acquisition practices and ensuring that ships can be efficiently sustained. | Defense | Billions of dollars (GAO) |

SBA’s Microloan Program (2020-03): The Small Business Administration’s Microloan Program should enhance its collaboration with other federal agencies that engage in microlending activities to better manage fragmentation. | Economic Development | Improved coordination and collaboration in microlending activities |

Consumer Product Safety Oversight (2015‑04): Congress should consider establishing a formal comprehensive oversight mechanism for consumer product safety agencies to address crosscutting issues as well as inefficiencies related to fragmentation and overlap such as communication and coordination challenges and jurisdictional questions between agencies. | General Government | Increased efficiency and effectiveness of consumer product oversight |

Federal Research (2019-15): Federal agencies could improve their research efforts to maintain U.S. competitiveness in quantum computing and synthetic biology by implementing leading practices for collaboration to better manage fragmentation. | Science and the Environment | Maintain U.S. competitiveness in the global economy |

Note: All estimates of potential financial benefits are dependent on various factors, such as whether action is taken and how it is taken. For estimates of potential financial benefits where outside estimates of potential financial benefits were not available, GAO developed the notional estimates, which are intended to provide a sense of the potential magnitude of benefits. Notional estimates have been developed using broad assumptions about potential financial benefits which are rooted in previously identified losses, the overall size of the program, previous experience with similar reforms, and similar rough indicators of potential financial benefits.

Why GAO Did This Study

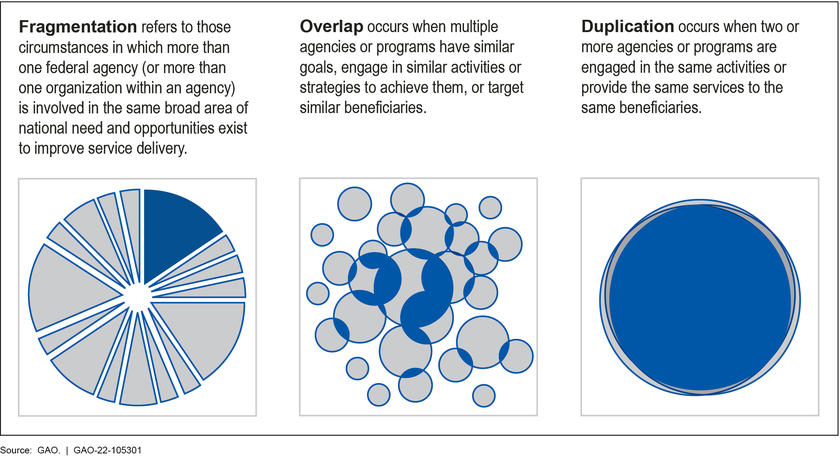

Introduction

| GAO’s online Action Tracker GAO’s Action Tracker, a publicly accessible website, allows Congress, executive branch agencies, and the public to track the federal government’s progress in addressing the issues we have identified. GAO’s Action Tracker includes a downloadable spreadsheet containing all actions. Areas and actions in the spreadsheet can be sorted and filtered by the year identified, mission, area name, implementation status, and implementing entities (Congress or executive branch agencies). The spreadsheet additionally notes which actions are also GAO priority recommendations—those recommendations GAO believes warrant priority attention from the heads of departments or agencies. |

Major Findings

IN THIS SECTION

- New Opportunities Exist to Improve Efficiency and Effectiveness across the Federal Government

- Congress and Executive Branch Agencies Continue to Address Actions Identified over the Last 12 Years across the Federal Government, Resulting in Significant Benefits

- Action on Remaining Open Areas and New Areas Could Yield Significant Additional Benefits

New Opportunities Exist to Improve Efficiency and Effectiveness across the Federal Government

| Mission | New area (area name links to appendix II) |

|---|---|

| Defense | 1. DOD’s Congressional Reporting Process: The Department of Defense’s Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Legislative Affairs should consult with internal stakeholders and identify opportunities to better manage duplication and fragmentation in its congressional reporting process. |

| 2. DOD Food Program Costs: The Department of Defense should assess the effectiveness and efficiency of its food program, as well as identify and define specific categories of costs for use in developing common measures to better manage fragmentation in its food program and potentially save millions of dollars annually. | |

| 3. DOD Nuclear Enterprise Oversight: The Department of Defense should clearly identify roles and responsibilities, among other steps, to improve coordination and better manage fragmentation among its new nuclear oversight organization and other nuclear oversight groups and stakeholders. | |

| Energy | 4. DOI’s Oil and Gas Data Systems: The Department of the Interior could better manage fragmentation and potential duplication by implementing a plan to address challenges with the key data systems it uses to manage oil and gas development, resulting in improved oversight and saved staff time. |

| General Government | 5. Drug Control Grant Tracking: The Office of National Drug Control Policy should document its process for identifying duplication, overlap, and fragmentation among drug control grants to better manage fragmented grant efforts, retain organizational knowledge, and demonstrate its internal control system’s effectiveness. |

| 6. Trade-Based Money Laundering: The Departments of the Treasury and Homeland Security could better manage fragmentation among their departments and other agencies with trade enforcement responsibilities and better detect illicit financial and trade activity by taking actions to enhance information sharing. | |

| Health | 7. Diet-Related Chronic Health Conditions: Congress should consider identifying and directing a federal entity to lead a federal strategy for reducing diet-related chronic health conditions, which could help manage fragmentation and overlap across 200 federal programs and activities. |

| 8. Medicaid Behavioral Health Demonstration: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should issue clear and consistent guidance to states participating in the certified community behavioral health clinics demonstration to help avoid potential duplication between demonstration payments and other Medicaid payments. | |

| Homeland Security/Law Enforcement | 9. Alternative Technologies for Radioactive Materials: Congress could help better manage fragmentation between the relevant agencies and mitigate potential fiscal exposure to the federal government from accidental or intentional incidents by directing the establishment of a national strategy for replacing technologies that use high-risk radioactive materials with alternatives. |

| 10. Biodefense Preparedness and Response: Federal and non-federal entities have opportunities to better prepare for and respond to significant biological incidents, including to better manage fragmented federal efforts. | |

| 11. Law Enforcement’s Use of Force: The Department of Justice should analyze use of force data collection efforts to identify the extent of potential overlap, validate these findings using relevant information, and identify options to better manage any existing overlap. | |

| Information Technology | 12. Digital Service Guidance: The Office of Management and Budget and General Services Administration could better manage fragmentation and reduce the risk of overlapping and duplicating efforts in developing information technology guidance for federal agencies by improving coordination between their U.S. Digital Service and 18F programs. |

| 13. Farm Production and Conservation IT Duplication and Overlap: By developing a strategic plan with performance goals and measures, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Farm Production and Conservation mission area could maximize efficiencies and reduce IT duplication and overlap. | |

| Science and the Environment | 14. Emergency Watershed Protection: The U.S. Department of Agriculture should clarify and document roles and responsibilities for Emergency Watershed Protection projects on National Forest System lands to help address fragmentation and ensure sponsors design the most effective projects. |

| 15. High-Performance Computing: The Office of Science and Technology Policy could better manage fragmentation in federal efforts to advance high-performance computing by fully incorporating desirable characteristics of a national strategy. | |

| 16. Nuclear Waste Cleanup Research and Development Efforts: By following leading practices for collaboration, the Department of Energy could better manage fragmentation and reduce potential duplication and overlap in its research and development to address its nuclear waste cleanup mission. |

| Mission | New area (area name links to appendix III) |

|---|---|

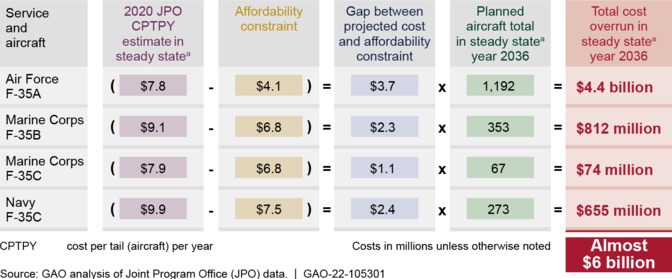

| Defense | 17. F-35 Lightning II Sustainment: The Department of Defense could reduce F-35 sustainment costs by hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars over several years by developing a strategic approach to ensure that the services can afford to operate and support the F-35. |

| General Government | 18. Federal Contracting Metrics: Contracting leaders at federal agencies should use metrics measuring cost reduction or avoidance to improve the performance of their procurement organizations and potentially save billions of dollars annually. |

| Health | 19. Staffing and Critical Incidents in Medicare Skilled Nursing Facilities: Congress should consider directing the Department of Health and Human Services to implement additional payment reductions for Skilled Nursing Facilities with high rates of potentially preventable hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, potentially saving hundreds of millions of dollars to Medicare. |

| Homeland Security/Law Enforcement | 20. BOP Emergency Preparedness and Response: The Bureau of Prisons should take steps to establish and incorporate cost-effective and feasible analytic features into its data systems and use these features to regularly conduct an analysis of its maintenance and repair project trends, which could save hundreds of thousands of dollars. |

| Social Services | 21. Social Security Disability Payments: The Social Security Administration could potentially save millions of dollars by identifying and addressing the causes for overpayments to Ticket to Work participants. |

| Mission | Existing area with new action(s) (area name links to Action Tracker) | Year introduced (year links to report) |

|---|---|---|

| Defense |

| |

| ||

| Economic Development |

| |

| Energy |

| |

| ||

| General Government |

| |

| ||

| ||

| Social Services |

|

aThe area name Department of Defense Commissaries and Exchanges was formerly named Department of Defense Commissaries. The area name is being changed to fully reflect the one new action that is being added in 2022.

b One of the new actions being added to this area replaces one of the existing actions. The current potential financial benefits from these actions remain consistent with prior reporting.

Congress and Executive Branch Agencies Continue to Address Actions Identified over the Last 12 Years across the Federal Government, Resulting in Significant Benefits

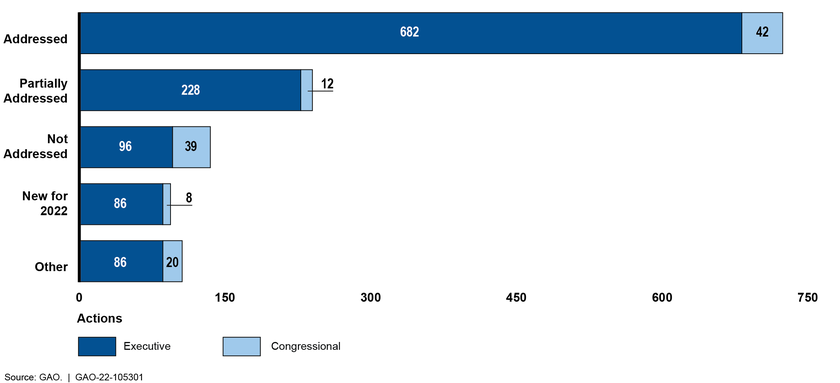

Figure 2: Status of 2011 to 2022 Actions Directed to Congress and the Executive Branch, as of March 2022

Note: Due to rounding, the total percentages may not add up to exactly 100 percent.

aIn assessing actions suggested for Congress, GAO applied the following criteria: “addressed” means relevant legislation has been enacted and addresses all aspects of the action needed; “partially addressed” means a relevant bill has passed a committee, the House of Representatives, or the Senate during the current congressional session, or relevant legislation has been enacted but only addressed part of the action needed; and “not addressed” means a bill may have been introduced but did not pass out of a committee, or no relevant legislation has been introduced. Actions suggested for Congress may also move to “addressed” or “partially addressed,” with or without relevant legislation, if an executive branch agency takes steps that address all or part of the action needed. At the beginning of a new congressional session, GAO reapplies the criteria. As a result, the status of an action may move from partially addressed to not addressed if relevant legislation is not reintroduced from the prior congressional session.

bIn assessing actions suggested for the executive branch, GAO applied the following criteria: “addressed” means implementation of the action needed has been completed; “partially addressed” means the action needed is in development or started but not yet completed; and “not addressed” means the administration, the agencies, or both have made minimal or no progress toward implementing the action needed.

cOf the 106 “other” actions, 51 are categorized as “consolidated or other” and 55 as “closed-not addressed.” GAO no longer assesses actions categorized as “closed-not addressed” or “consolidated or other.” In most cases, “consolidated or other” actions were replaced or subsumed by new actions based on additional audit work or other relevant information. An action is categorized as “closed-not addressed” when the action is no longer relevant due to changing circumstances.

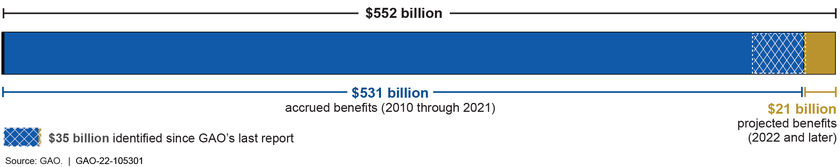

Actions Taken By Congress and Executive Branch Agencies Led to Hundreds of Billions in Financial Benefits

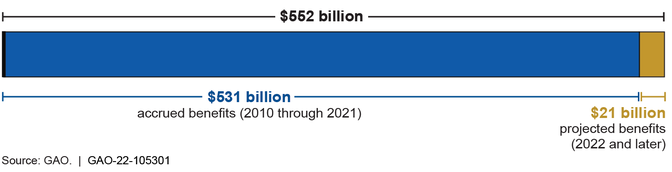

Figure 3: Total Reported Financial Benefits of $552 Billion, as of March 2022

Figure 4: Summary of 12 Years of Benefits Achieved by Mission, as of March 2022

Area name (annual report year/area number links to Action Tracker) | Actions taken | Financial benefit |

|---|---|---|

Weapon Systems Acquisition Programs (2011‑38) | Congress passed the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009, which implemented a number of GAO’s recommendations for how the Department of Defense (DOD) develops and acquires weapon systems. GAO highlighted the need for additional action in this area in its 2011 report. In 2017 and 2019, GAO reported that DOD had followed more best practices for these acquisitions, which greatly reduced cost growth for weapons systems over time.a | Savings of approximately $180.0 billion from 2011 through 2017, according to GAO analysis. DOD concurred with GAO’s methodology. |

Medicaid Demonstration Waivers (2014‑21) | The Department of Health and Human Services changed processes to curtail some problematic methods of determining budget neutrality and restricted the amount of unspent funds states can accrue and carry forward to expand demonstrations. The department could further reduce federal spending by addressing other problematic methods. | Federal savings of approximately $140.6 billion from 2016 through 2021, and tens of billions of additional savings could potentially accrue in 2022, according to agency and GAO estimates. |

Higher Education Assistance (2013‑16) | The Department of Education adjusted borrower incomes for inflation in its Direct Loan program reestimates for the fiscal year 2017 Agency Financial Report. GAO previously reported that this step resulted in a downward reestimate of income-driven repayment plan costs for loans issued through the 2016 cohort totaling $17.5 billion. Education modified its estimation approach to produce separate cost estimates for each type of loan eligible for IDR plans, resulting in a downward reestimate of plan cost totaling $6.7 billion for loans issued through the 2016 cohort and also estimated that Direct Loan subsidy costs for new loans issued from the fiscal year 2017 through 2020 cohorts were a net present value of $15.4 billion lower than they would have been without this correction. | Savings of approximately $43 billion through 2020, according to agency estimates. |

Agencies’ Use of Strategic Sourcing (2013‑23) | The Department of Veterans Affairs evaluated strategic sourcing opportunities, set goals, tracked metrics, and ultimately procured a larger share of goods and services—including information technology (IT)—using contracts aligned with strategic sourcing principles. | The Department of Veterans Affairs realized cost avoidance of about $10.8 billion from fiscal years 2013 through 2017, according to GAO estimates. Veterans Affairs concurred with GAO’s methodology. Billions more of savings are possible across the federal government, according to OMB estimates based on 2017 to 2020 data. |

Virtual Currency Tax Information Reporting (2020‑23) | Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, section 80603 of which requires third-party reporting on digital assets, such as virtual currency. This provision that takes effect beginning with the 2023 tax year increases third-party reporting and could improve tax compliance by providing IRS with better information about virtual currency transactions.b | $10 billion or more could potentially accrue from 2024 to 2031, according to estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation. |

Children’s Disability Reviews (2015‑21) | The Social Security Administration conducted additional continuing disability reviews in fiscal years 2013 through 2016 to ensure that only child Supplemental Security Income recipients who are eligible for benefits receive them, thereby preventing potentially costly overpayments. | Savings of approximately $9.6 billion from fiscal year 2013 through fiscal year 2016, according to agency estimates. Billions in additional savings could potentially accrue, according to agency estimates. |

Federal Payments for Hospital Uncompensated Care (2017‑25) | The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in a final rule that the agency would begin basing Medicare Uncompensated Care payments on hospital uncompensated care costs.c | Savings of about $9.4 billion in fiscal years 2018 through 2022. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services concurred with GAO’s estimates. Billions in potential savings could accrue by addressing an additional action in this area, according to GAO estimates. |

Tax Policies and Enforcement (2015‑17) | Congress amended the audit procedures applicable to certain large partnerships to require that they pay audit adjustments at the partnership level.d | Increased revenue of about $9.3 billion from fiscal years 2019 to 2025, of which about $3.3 billion has accrued and about $6 billion is expected to accrue in fiscal year 2022 or later, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. Billions in additional savings could potentially accrue by addressing other actions in this area, according to Joint Committee on Taxation estimates. |

Federal Data Centers (2011‑15) | Twenty-two federal agencies have been consolidating their data centers to improve government efficiency and supporting the Office of Management and Budget’s Data Center Optimization Initiative. For example, the Department of Defense has closed 46 data centers and also identified additional data center-related cost savings of $178.5 million in fiscal year 2020 alone. | Savings of approximately $5.7 billion from fiscal years 2011 to 2021, according to quarterly cost savings report from agencies. Tens of millions in additional savings could potentially accrue, according to estimates from federal agencies. |

Note: The estimates in this report are from a range of sources, including GAO, executive branch agencies, CBO, and the Joint Committee on Taxation. Some estimates have been updated since GAO’s 2021 report to reflect more recent analysis.

aPub. L. No. 111-23, 123 Stat. 1704 (2009).

bPub. L. No. 117-58, § 80603, 135 Stat. 429, 1339 (2021).

c82 Fed. Reg. 37990, 38000 (2017).

dBipartisan Budget Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-74, § 1101, 129 Stat. 584, 625–638 (2015).

Other Benefits Resulting from Actions Taken by Congress and Executive Branch Agencies

- Arctic Maritime Infrastructure (2021‑05). Arctic sea ice has diminished, lengthening the navigation season and increasing opportunities for maritime shipping. However, the U.S. Arctic lacks maritime infrastructure, exacerbating risks inherent to shipping in the Arctic, such as vast distances and dangerous weather.In 2020, we found that existing U.S. Arctic interagency groups do not reflect leading collaboration practices, such as sustained leadership, and the White House had not designated which entity is to lead U.S. Artic maritime infrastructure efforts. We recommended that the appropriate entities within the Executive Office of the President, including the Office of Science and Technology Policy, should designate the interagency group responsible for leading and coordinating federal efforts to address maritime infrastructure in the U.S. Arctic.In response, the Office of Science and Technology Policy has taken multiple actions, such as (1) reactivating the Arctic Executive Steering Committee to advance U.S. interests and coordinate federal actions in the Arctic; (2) developing a proposal for an interagency team to collaborate on research used for federal investment in the Arctic to reduce duplicative efforts; and (3) working with the Office of Management and Budget on a process to convene interested federal agencies to review current infrastructure needs in the U.S. Arctic recommended for federal spending. As a result of these actions, the Office of Science and Technology Policy has interagency leadership and coordination efforts in place to help leverage federal resources to address maritime infrastructure and achieve government-wide priorities in the complex and changing U.S. Arctic.

- Chemical Terrorism (2019‑09). The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) manages several programs and activities designed to prevent and protect against domestic attacks using chemical agents.In 2018, we found that DHS had not fully integrated and coordinated its chemical defense programs and activities, with several components having already conducted similar activities without DHS-wide direction and coordination. We recommended that DHS develop a strategy and implementation plan to help guide, support, integrate, and coordinate its chemical defense programs and activities; leverage resources and capabilities; and provide a roadmap for addressing any identified gaps to help address fragmentation and coordination issues.In response, DHS issued a Chemical Defense Strategy in December 2019 and an implementation plan in September 2021. These efforts included overarching goals to combat chemical threats and incidents along with identified roles and responsibilities to address these goals, which are essential to helping guide DHS’s efforts to address fragmentation and coordination issues.

- STEM Education Programs (2018‑13). Education programs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields are intended to enhance the nation’s global competitiveness.In 2018, we reported that the Committee on STEM Education, an interagency body responsible for implementing the federal STEM education strategic plan, reported it managed STEM education program overlap through coordination with agencies administering these programs. However, we found that the Committee had not fully met its responsibilities to assess the federal STEM education portfolio. Specifically, the Committee had not reviewed programs’ performance assessments, as required by its authorizing charter. We recommended that the leadership of the Committee review performance assessments of federal STEM education programs and take appropriate steps to enhance effectiveness of the portfolio.In response, the Committee issued a 5-year STEM education strategic plan to enhance the effectiveness of the STEM education portfolio, which required federal agencies that comprise the Committee to perform a systematic review of evidence from current programs. According to the Committee’s December 2021 Annual Report, Committee agencies shared how they assessed the impact of their STEM education programs. The report specified the number of programs that had been evaluated, the number of evaluations underway, and links to recently issued performance reports for individual programs. By sharing recent performance reports, the Committee has taken steps to foster interagency learning, which could enhance the portfolio’s effectiveness.

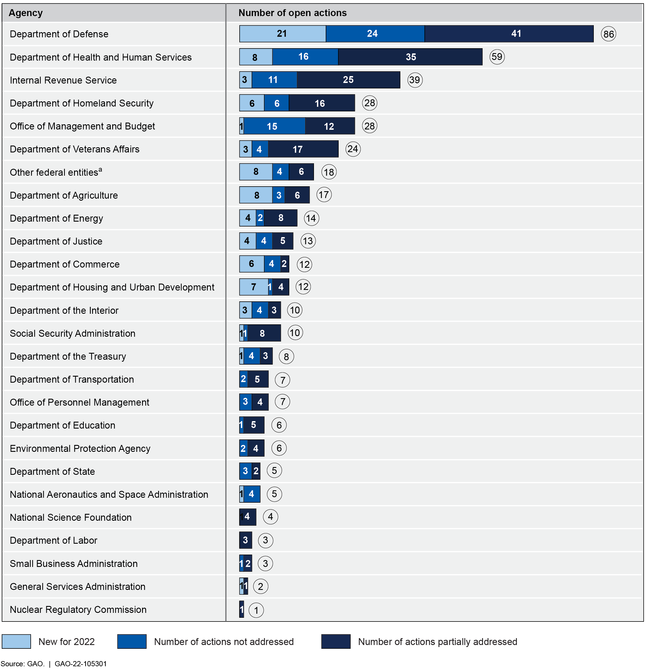

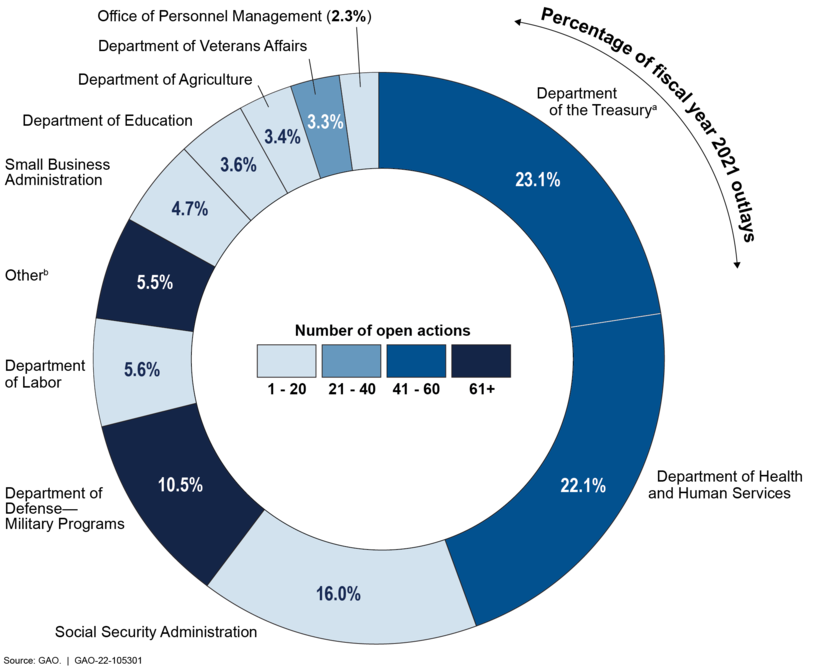

Action on Remaining Open Areas and New Areas Could Yield Significant Additional Benefits

Open Areas Directed to Congress and Executive Branch Agencies with Potential Financial Benefits

Figure 5: Number of Partially Addressed and Not Addressed Actions Since 2011 by Agency, as of March 2022

Figure 6: Fiscal Year 2021 Outlays and Number of Open Actions Since 2011, by Agency

| Area name and description (Year-number links to Action Tracker) | Mission | Potential financial benefitsa (Source) |

|---|---|---|

| *Medicare Payments by Place of Service (2016‑30): Congress should consider directing the Secretary of Health and Human Services to equalize payment rates between settings for evaluation and management office visits and other services that the Secretary deems appropriate and return the associated savings to the Medicare program. (GAO‑16‑189) | Health | Billions of dollars annually (MedPAC and Bipartisan Policy Center) |

| Category Management (2021‑06): The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should further its Category Management initiative to improve how agencies buy common goods and services by taking such actions as addressing agencies’ data management challenges and establishing additional performance metrics to help the federal government achieve cost savings, as well as potentially eliminate duplicative contracts. (GAO‑21‑40) | General Government | Billions of dollars over the next 5 years (OMB and GAO) |

| *Disability and Unemployment Benefits (2014‑08): Congress should consider passing legislation to require the Social Security Administration to offset Disability Insurance benefits for any Unemployment Insurance benefits received in the same period. (GAO‑12‑764) | Income Security | $2.2 billion over 10 years (OMB) |

| Student Loan Income-Driven Repayment Plans (2020‑29): The Department of Education should obtain data in order to verify income information for borrowers reporting zero income on Income-Driven Repayment applications. (GAO‑19‑347) | Training, Employment, and Education | More than $2 billion over 10 years (Congressional Budget Office) |

| Navy Shipbuilding (2017‑18): The U.S. Navy could achieve cost savings by improving its acquisition practices and ensuring that ships can be efficiently sustained. (GAO‑20‑2, GAO‑17‑211,GAO‑16‑71) | Defense | Billions of dollars (GAO) |

| *Internal Revenue Service Enforcement Efforts (2012‑44): Enhancing the Internal Revenue Service enforcement and service capabilities can help reduce the gap between taxes owed and paid by collecting tax revenue and facilitating voluntary compliance. This could include expanding third-party information reporting. For example, reporting could be required for certain payments that rental real estate owners make to service providers, such as contractors who perform repairs on their rental properties, and for payments that businesses make to corporations for services. (GAO‑12‑176, GAO‑11‑493, GAO‑09‑238, GAO‑08‑956) | General Government | Billions of dollars (GAO) |

Note: The potential financial benefits shown in this table represent estimates of amounts GAO or others believe could accrue if steps are taken to implement the actions described. All estimates of potential savings are dependent on various factors, such as whether action is taken and how it is taken. Actual savings may be less, depending on costs associated with implementing the action, unintended consequences, and the effect of controlling for other factors. The individual estimates in this table should be compared with caution, as they come from a variety of sources, which consider different time periods and use different data sources, assumptions, and methodologies.

aGAO developed the notional estimates, which are intended to provide a sense of the potential magnitude of savings. Notional estimates have been developed using broad assumptions about potential savings, which are rooted in previously identified losses, the overall size of the program, previous experience with similar reforms, and similar rough indicators of potential savings. GAO generally determines the notional labels (millions, tens of millions, hundreds of millions, etc.) using a risk-based approach that takes into account factors such as the possible minimum and maximum values of the cost savings estimate (where available), the quality of the data underlying those values, the certainty of those values, and the rigor of the estimation method used.

Open Areas with Other Benefits Directed to Congress and Executive Branch Agencies

Area name and description (Year-number links to Action Tracker) | Mission | Potential benefit |

|---|---|---|

Economic Development | Improved coordination and collaboration in microlending activities. | |

VA Long-Term Care Fragmentation (2020‑11): The Department of Veterans Affairs should implement a consistent approach to better manage long-term care programs at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center level and improve access to the right care for veterans. (GAO‑20‑284) | Health | Improved ability to provide consistent care and access to long-term care for veterans. |

Federal Research (2019‑15): Federal agencies could improve their research efforts to maintain U.S. competitiveness in quantum computing and synthetic biology by implementing leading practices for collaboration to better manage fragmentation. (GAO‑18‑656) | Science and the environment | Improved federal research efforts to maintain U.S. competitiveness in the global economy. |

Imported Seafood Oversight (2018‑01): Improved coordination between the Food and Drug Administration and the Food Safety and Inspection Service on the oversight of imported seafood would help the agencies better manage fragmentation and more consistently protect consumers from unsafe drug residues. (GAO‑17‑443) | Agriculture | More effective oversight of imported seafood. |

Graduate Medical Education Funding (2018‑05): The Department of Health and Human Services should coordinate with federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans Affairs, to improve the effectiveness and oversight of fragmented federal funding for physician graduate medical education, which cost the federal government $14.5 billion in 2015. (GAO‑18‑240) | Health | Better data quality for examining graduate medical education programs. |

*Consumer Product Safety Oversight (2015‑04): Congress should consider establishing a formal comprehensive oversight mechanism for consumer product safety agencies to address crosscutting issues as well as inefficiencies related to fragmentation and overlap such as communication and coordination challenges and jurisdictional questions between agencies. (GAO‑15‑52) | General Government | Increased efficiency and effectiveness of consumer product oversight |

Closing

Comptroller General of the United States

Congressional Addressees

The Honorable Patrick Leahy

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Shelby

Vice Chairman

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Bernie Sanders

Chairman

The Honorable Lindsey Graham

Ranking Member

Committee on the Budget

United States Senate

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

The Honorable Rob Portman

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro

Chair

The Honorable Kay Granger

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Yarmuth

Chairman

The Honorable Jason Smith

Republican Leader

Committee on the Budget

House of Representatives

The Honorable Carolyn B. Maloney

Chairwoman

The Honorable James Comer

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mark R. Warner

United States Senate

Appendixes

IN THIS SECTION

- Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

- Appendix II: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Fragmentation, Overlap, or Duplication

- 1. DOD’s Congressional Reporting Process

- 2. DOD Food Program Costs

- 3. DOD Nuclear Enterprise Oversight

- 4. DOI’s Oil and Gas Data Systems

- 5. Drug Control Grant Tracking

- 6. Trade-Based Money Laundering

- 7. Diet-Related Chronic Health Conditions

- 8. Medicaid Behavioral Health Demonstration

- 9. Alternative Technologies for Radioactive Materials

- 10. Biodefense Preparedness and Response

- 11. Law Enforcement’s Use of Force

- 12. Digital Service Guidance

- 13. Farm Production and Conservation IT Duplication and Overlap

- 14. Emergency Watershed Protection

- 15. High-Performance Computing

- 16. Nuclear Waste Cleanup Research and Development Efforts

- Appendix III: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Other Cost Savings or Revenue Enhancement Opportunities

- 17. F-35 Lightning II Sustainment

- 18. Federal Contracting Metrics

- 19. Staffing and Critical Incidents in Medicare Skilled Nursing Facilities

- 20. BOP Emergency Preparedness and Response

- 21. Social Security Disability Payments

- Appendix IV: New Actions Added to Existing Areas in 2022

- Appendix V: Open Congressional Actions, by Mission

- Appendix VI: Additional Information on Programs Identified

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

Bookmark:Assessing the Status of Selected Previously Identified Actions

- In assessing actions suggested for Congress, we applied the following criteria: “addressed” means relevant legislation has been enacted and addresses all aspects of the action needed; “partially addressed” means a relevant bill has passed a committee, the House of Representatives, or the Senate during the current congressional session, or relevant legislation has been enacted but only addressed part of the action needed; and “not addressed” means a bill may have been introduced but did not pass out of a committee, or no relevant legislation has been introduced.

- Actions suggested for Congress may also move to “addressed” or “partially addressed” with or without relevant legislation if an executive branch agency takes steps that address all or part of the action needed. At the beginning of a new congressional session, we reapply the criteria. As a result, the status of an action may move from partially addressed to not addressed if relevant legislation is not reintroduced from the prior congressional session.

Methodology for Generating Financial Benefits Estimates

Appendix II: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Fragmentation, Overlap, or Duplication

Bookmark:1. DOD’s Congressional Reporting Process

Bookmark:The Department of Defense’s Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Legislative Affairs should consult with internal stakeholders and identify opportunities to better manage duplication and fragmentation in its congressional reporting process. | ||

| Implementing Entity Department of Defense | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for DOD to better manage duplication and fragmentation in its congressional reporting process. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

2. DOD Food Program Costs

Bookmark:The Department of Defense should assess the effectiveness and efficiency of its food program, as well as identify and define specific categories of costs for use in developing common measures to better manage fragmentation in its food program and potentially save millions of dollars annually. | ||

Implementing Entity The Departments of Defense, Army, Air Force, and Navy, and the U.S. Marine Corps | Link to Actions GAO identified five actions to improve information for assessing DOD’s food program use and costs. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

3. DOD Nuclear Enterprise Oversight

Bookmark:The Department of Defense should clearly identify roles and responsibilities, among other steps, to improve coordination and better manage fragmentation among its new nuclear oversight organization and other nuclear oversight groups and stakeholders. | ||

Implementing Entity Department of Defense | Link to Actions GAO identified three actions to DOD to improve oversight of the nuclear enterprise. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

4. DOI’s Oil and Gas Data Systems

Bookmark:The Department of the Interior could better manage fragmentation and potential duplication by implementing a plan to address challenges with the key data systems it uses to manage oil and gas development, resulting in improved oversight and saved staff time. | ||

Implementing Entity Department of the Interior | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for Interior to develop a plan to address data-sharing challenges to better manage fragmentation and potential duplication. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

5. Drug Control Grant Tracking

Bookmark:The Office of National Drug Control Policy should document its process for identifying duplication, overlap, and fragmentation among drug control grants to better manage fragmented grant efforts, retain organizational knowledge, and demonstrate its internal control system’s effectiveness. | ||

Implementing Entity Office of National Drug Control Policy | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for ONDCP to document its process for identifying duplication, overlap, and fragmentation among its drug control grants. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

6. Trade-Based Money Laundering

Bookmark:The Departments of the Treasury and Homeland Security could better manage fragmentation among their departments and other agencies with trade enforcement responsibilities and better detect illicit financial and trade activity by taking actions to enhance information sharing. | ||

Implementing Entity Department of the Treasury and Department of Homeland Security | Link to Actions GAO identified two actions for Treasury and DHS to better share information to combat illicit financial and trade activity. See GAO’s Action Tracker. Contact Information Michael Clements at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov or Rebecca Shea at (202) 512-6722 or shear@gao.gov | |

7. Diet-Related Chronic Health Conditions

Bookmark:Congress should consider identifying and directing a federal entity to lead a federal strategy for reducing diet-related chronic health conditions, which could help manage fragmentation and overlap across 200 federal programs and activities. | ||

Implementing Entity Congress | Link to Actions GAO identified one matter for Congress to consider identifying and directing a federal entity to lead a strategy. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

8. Medicaid Behavioral Health Demonstration

Bookmark:The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should issue clear and consistent guidance to states participating in the certified community behavioral health clinics demonstration to help avoid potential duplication between demonstration payments and other Medicaid payments. | ||

Implementing Entity Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for CMS to improve demonstration guidance for states. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

9. Alternative Technologies for Radioactive Materials

Bookmark:Congress could help better manage fragmentation between the relevant agencies and mitigate potential fiscal exposure to the federal government from accidental or intentional incidents by directing the establishment of a national strategy for replacing technologies that use high-risk radioactive materials with alternatives. | ||

Implementing Entity Congress | Link to Actions GAO identified three matters for Congress to promote alternative technologies that replace high-risk radioactive materials in medical and industrial applications. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

10. Biodefense Preparedness and Response

Bookmark:Federal and non-federal entities have opportunities to better prepare for and respond to significant biological incidents, including to better manage fragmented federal efforts. | ||

Implementing Entity Departments of Homeland Security, Defense, Health and Human Services, and Agriculture | Link to Actions GAO identified 16 actions—four actions each for DHS, DOD, HHS, and USDA—to work through the Biodefense Steering Committee in order to better prepare for the next biological threat. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

- Define a set of capabilities for responding to nationally significant biological incidents;

- Establish a process at the interagency level for agencies to assess and communicate priorities for exercising biodefense capabilities;

- Provide guidance for federal and nonfederal partners on how to report on biodefense capabilities in after-action reports for exercises and real-world incidents in a consistent manner; and

- Routinely monitor the results of interagency biological exercises and real-world incidents to identify and report patterns of challenges, potential root causes, and recommendations for addressing them, including the responsible agencies, to the Biodefense Steering Committee.

11. Law Enforcement’s Use of Force

Bookmark:The Department of Justice should analyze use of force data collection efforts to identify the extent of potential overlap, validate these findings using relevant information, and identify options to better manage any existing overlap. | ||

Implementing Entity Department of Justice | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for DOJ to take to analyze potential overlap among its data collection efforts related to law enforcement’s use of force. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

12. Digital Service Guidance

Bookmark:The Office of Management and Budget and General Services Administration could better manage fragmentation and reduce the risk of overlapping and duplicating efforts in developing information technology guidance for federal agencies by improving coordination between their U.S. Digital Service and 18F programs. | ||

Implementing Entity Office of Management and Budget and General Services Administration | Link to Actions GAO identified two actions, one each for OMB and GSA to improve coordination on the planning and development of IT guidance. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

13. Farm Production and Conservation IT Duplication and Overlap

Bookmark:By developing a strategic plan with performance goals and measures, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Farm Production and Conservation mission area could maximize efficiencies and reduce IT duplication and overlap. | ||

Implementing Entity United States Department of Agriculture | Link to Actions GAO identified two actions for USDA to maximize efficiencies, reduce IT duplication and overlap, and monitor program performance. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

14. Emergency Watershed Protection

Bookmark:The U.S. Department of Agriculture should clarify and document roles and responsibilities for Emergency Watershed Protection projects on National Forest System lands to help address fragmentation and ensure sponsors design the most effective projects. | ||

Implementing Entity U.S. Department of Agriculture | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for USDA to clarify roles and responsibilities for how and when emergency watershed protection projects can be done on National Forest System lands. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

15. High-Performance Computing

Bookmark:The Office of Science and Technology Policy could better manage fragmentation in federal efforts to advance high-performance computing by fully incorporating desirable characteristics of a national strategy. | ||

Implementing Entity Office of Science and Technology Policy | Link to Actions GAO identified two actions for OSTP to better achieve the objectives of the national strategy for high-performance computing. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

16. Nuclear Waste Cleanup Research and Development Efforts

Bookmark:By following leading practices for collaboration, the Department of Energy could better manage fragmentation and reduce potential duplication and overlap in its research and development to address its nuclear waste cleanup mission. | ||

Implementing Entity Department of Energy | Link to Actions GAO identified three actions for DOE to better manage fragmentation and reduce potentially duplicative and overlapping research and development to address its nuclear cleanup mission. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

Appendix III: New Areas in Which GAO Has Identified Other Cost Savings or Revenue Enhancement Opportunities

Bookmark:17. F-35 Lightning II Sustainment

Bookmark:The Department of Defense could reduce F-35 sustainment costs by hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars over several years by developing a strategic approach to ensure that the services can afford to operate and support the F-35. | ||

Implementing Entity Congress and the Department of Defense | Link to Actions GAO identified one matter for Congress and four actions to DOD to improve the affordability of the F-35 program. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

Figure 8: Gap between F-35 Affordability Constraints and Estimated Sustainment Costs in 2036

18. Federal Contracting Metrics

Bookmark:Contracting leaders at federal agencies should use metrics measuring cost reduction or avoidance to improve the performance of their procurement organizations and potentially save billions of dollars annually. | ||

Implementing Entity Departments of the Army, the Navy, Homeland Security, and Veterans Affairs, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration | Link to Actions GAO identified five actions for federal agencies to improve the performance of their procurement organizations. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

19. Staffing and Critical Incidents in Medicare Skilled Nursing Facilities

Bookmark:Congress should consider directing the Department of Health and Human Services to implement additional payment reductions for Skilled Nursing Facilities with high rates of potentially preventable hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, potentially saving hundreds of millions of dollars to Medicare. | ||

Implementing Entity Congress | Link to Actions GAO identified a matter for Congress to help reduce unnecessary spending in Medicare. See GAO's Action Tracker. | |

20. BOP Emergency Preparedness and Response

Bookmark:The Bureau of Prisons should take steps to establish and incorporate cost-effective and feasible analytic features into its data systems and use these features to regularly conduct an analysis of its maintenance and repair project trends, which could save hundreds of thousands of dollars. | ||

Implementing Entity Bureau of Prisons | Link to Actions GAO identified three actions for the Bureau of Prisons to better monitor its maintenance and repair projects for possible project delays and cost escalation. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

21. Social Security Disability Payments

Bookmark:The Social Security Administration could potentially save millions of dollars by identifying and addressing the causes for overpayments to Ticket to Work participants. | ||

Implementing Entity Social Security Administration | Link to Actions GAO identified one action for SSA to identify and address the causes of Ticket to Work overpayments. See GAO’s Action Tracker. | |

Appendix IV: New Actions Added to Existing Areas in 2022

Bookmark:| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Department of Defense Commissaries and Exchanges In February 2022, GAO identified one new action to help the Department of Defense better manage fragmentation among its commissaries and exchanges by establishing an overarching policy and more consistent processes to provide reasonable assurance that its resale goods are not produced by forced labor. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-22-105056 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| The Department of Defense (DOD) has established a common goal of seeking to prevent human trafficking, which can include forced labor. However, DOD has not taken steps to ensure collaboration across the commissaries and exchanges, including establishing an overarching policy and consistent processes to prevent the resale of goods produced by forced labor. The Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA) and the military exchanges have collaborated on some efforts, such as purchasing resale goods, although their collaboration has not focused on addressing forced labor. Further, DeCA and the exchanges have their own policies and processes to prevent the resale of goods produced by forced labor, which have resulted in inconsistencies. For example, DeCA and the exchanges have varying levels of requirements for their suppliers to provide information about their supply chains and the possible use of forced labor to produce goods for resale. With better collaboration and an overarching policy and processes to guide the efforts of the commissaries and exchanges, DOD can better manage fragmentation across DeCA and the exchanges and have more reasonable assurance that its resale goods are not produced by forced labor. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended in February 2022 that the Secretary of Defense ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, in collaboration with the military departments, DeCA, and the military exchanges, establishes an overarching policy and consistent processes to provide reasonable assurance that the goods sold in the commissaries and exchanges are not produced by forced labor, including—for each type of resale good—consistent minimum requirements for that type of good and the supplier information that is to be collected for that type. DOD agreed with this recommendation. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to DOD for review and comment. DOD stated that it did not have comments on this report section. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Defense Travel In June 2021, GAO identified one new action to help the Department of Defense strengthen its ongoing initiatives to reduce improper travel payments, potentially saving millions of dollars over 5 years. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-21-214 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| GAO reported in June 2021 that many Department of Defense (DOD) travelers do not stay in on-base lodging and are at times inappropriately reimbursed for off-base stays, despite established policy that requires travelers to use available on-base lodging facilities when traveling. Reimbursement of travelers for stays in off-base lodging when policy directed them to stay in on-base lodging is an improper payment and a monetary loss to the government. In a 2019 report, DOD estimated that $13.7 million in travel costs could have been avoided in fiscal year 2016 if the requirement to stay on base had been properly enforced. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended that the Secretary of Defense ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, in collaboration with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment, assesses by military service the extent to which DOD servicemembers and civilian employees are inappropriately using off-base lodging for official travel and why it is occurring, and develop a plan to address any issues identified. DOD agreed and said it would address this recommendation. While GAO cannot precisely estimate the potential savings from this action, if DOD implemented this action, DOD could potentially save millions of dollars over 5 years. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to DOD for review and comment. DOD said it did not have comments on this report section. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Economic Development Programs In July 2021, GAO identified five new actions to help the Departments of Commerce, Housing and Urban Development, and Agriculture incorporate further collaboration to help grantees and local communities better manage fragmented efforts related to federal economic development. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-21-579 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| Federal agencies administer economic development programs that support state and local communities’ efforts to develop strategic plans and encourage the leveraging of federal and state resources. However, GAO reported in July 2021 that the Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA) and the Departments of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Agriculture (USDA) had not incorporated leading practices for effective interagency collaboration in select economic development programs. By incorporating these practices, such as updating written agreements and monitoring progress towards outcomes, these agencies could help their grantees and local communities manage fragmented efforts, such as better addressing economic development needs. | ||

| New action(s): In July 2021, GAO recommended that EDA and HUD should review their community and economic development interagency agreement to align with current priorities, determine to what extent to include USDA, and monitor progress toward achieving outcomes of their interagency agreement. Additionally, USDA should work with EDA and HUD to identify opportunities to be included in their strategic planning for community and economic development. All three agencies generally agreed with GAO’s recommendations. As of March 2022, EDA stated that its existing agreement was limited to a specific task and therefore EDA may address the recommendations through a different interagency agreement or other document, action, or policy. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to EDA, HUD, and USDA for review and comment. USDA and HUD stated they had no comments on this report section and EDA provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| DOE's Treatment of Hanford's Low-Activity Waste In December 2021, GAO identified three new actions to help save tens of billions of dollars by allowing the Department of Energy to pursue less expensive disposal options. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-22-104365 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| The Department of Energy (DOE) oversees the treatment and disposal of 54 million gallons of nuclear and hazardous waste at the Hanford site in the state of Washington. DOE plans to vitrify (immobilize in glass) a portion of the waste, but it has not made a decision on how to treat and dispose of the rest (roughly 40 percent) referred to as supplemental low-activity waste. In December 2021, GAO found that without clear congressional authority, DOE faces legal challenges with its plans to immobilize its waste in grout (which is less expensive than using glass), transport it outside of Washington, and continue with its Test Bed Initiative, a scale test of an approach to demonstrate the feasibility of grouting, transporting, and disposing of certain waste offsite. These clarifications could help DOE save tens of billions of dollars. The lack of clarity regarding its authority may result in additional delays in treating and disposing of supplemental low-activity waste. GAO also found that DOE had not followed the best practice of analyzing a full range of disposal options. As a result, DOE is likely missing opportunities to reduce risks in waste treatment. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended in December 2021 that Congress should consider (1) clarifying, in a manner that does not impair the regulatory authorities of the Environmental Protection Agency and any state, DOE's authority to determine, in consultation with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, whether portions of the tank waste can be managed as a waste type other than high-level waste and can be disposed of outside Washington, and (2) specifying that Resource Conservation and Recovery Act’s high-level waste vitrification standard does not apply to the volume of waste from the second phase of the Test Bed Initiative. GAO also recommended that DOE expand future analyses of disposal options to include all federal and commercial facilities that could potentially receive grouted supplemental low-activity waste from the Hanford site. DOE agreed with this recommendation. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to DOE for review and comment. DOE said it had no comments on this report section. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Oil and Gas Resources In November 2021, GAO identified two new actions to help the Bureau of Land Management improve its oil and gas leasing process, which could potentially result in millions of dollars in additional revenues over the next decade. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-22-103968 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| The Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) process for leasing federal lands for oil and gas development has changed in recent years due to technology developments. However, in November 2021 GAO found that BLM has not fully reviewed the application fees for leases since 2005. BLM’s biennial reviews of its application fees do not currently consider all of the costs involved. A full review could help BLM determine if these fees cover costs as intended, including a likely increase in cost to the government associated with changes to the process. Further, BLM could consider charging a fee to nominate lands for leasing. BLM has not re-examined whether to charge such a fee since 2014, despite expending resources to process nominations that do not result in leases. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended in November 2021 that BLM should revise its approach to conducting biennial fee reviews to ensure that future reviews examine all costs BLM intended to recover and, where appropriate, adjust application fees accordingly. GAO also recommended that BLM re-examine whether to charge a fee for nominating lands for oil and gas development. BLM agreed with the recommendations. As of February 2022, the Department of the Interior reported that it plans to take steps that would address each action. GAO cannot estimate precisely the revenues generated from these actions because they will depend on whether BLM changes the fees, by how much, and any associated changes in potential lease behaviors, but if BLM adjusted fees to recapture even 10 percent of currently uncovered administrative costs, it could amount to millions of dollars in new revenues over the next decade. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation:GAO provided a draft of this report section to Interior for review and comment. Interior provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Facility Construction In October 2021, GAO identified two new actions to help the Department of Veterans Affairs avoid schedule delays and better manage medical facility construction projects by improving communication between offices. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-22-103962 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| In providing health care to over 9 million enrolled veterans, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) manages a portfolio that includes 5,625 owned and 1,690 leased buildings as of fiscal year 2020. GAO found instances of insufficient communication between (1) local offices and the Office of Construction and Facilities Management (CFM), and (2) local construction offices and the Office of Information and Technology (OIT). For example, CFM officials said that earlier involvement in projects could help avoid delays and ensure cost and schedule changes are properly documented. Improved communication would help ensure all parties are aware of project status at the appropriate time to avoid scheduling delays. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended in October 2021 that the Secretary of VA should (1) ensure that CFM and the regions and medical centers follow key practices for communication during projects, and (2) clearly define OIT’s role in developing and executing construction projects. VA agreed with these recommendations. As of February 2022, VA officials said that CFM has drafted a project planning communication template to communicate project status and that VA has also established a working group that includes both CFM and OIT to coordinate project communication. The target date for completion of these efforts is April 30, 2022. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to VA for review and comment.VA provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| IRS Taxpayer Service In April 2022, GAO identified three new actions to help IRS improve taxpayer service and better manage refund interest payments, potentially saving $20 million or more annually. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-22-104938 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| GAO reported in April 2022 that IRS experienced challenges during the 2021 tax filing season, including a backlog of 8 million prior year returns and 35 million returns requiring review due to errors, which contributed to delayed refunds. IRS has paid almost $14 billion in refund interest since 2015. Refund interest may occur due to factors within IRS’s control (such as processing time) or outside of IRS’s control (such as legislation with retroactive tax benefits). IRS has not established a mechanism to determine why it pays refund interest and how to reduce this amount. If the last 7 years’ average interest paid annually by IRS could be reduced by 1 percent, IRS could save $20 million per year. Taxpayers also struggled to get help from IRS and its “Where’s My Refund” tool. Modernizing that tool would help IRS better serve taxpayers and could reduce telephone assistance costs, although GAO cannot estimate associated savings. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended that IRS work with the Department of the Treasury to modernize “Where’s My Refund” to better address taxpayer needs, and IRS agreed. GAO also recommended that IRS determine why it pays interest to taxpayers, report this information to the public and Congress, and take steps to reduce interest payments within IRS’s control. IRS agreed to look for ways to reduce refund interest payments related to the return backlog but disagreed with tracking and reporting why it pays interest. IRS stated that interest is prescribed by statute, and it does not consider interest paid a reliable or meaningful business measure. GAO maintains that interest payments are an expense to the U.S. government, and monitoring them could help IRS know how, if at all, the expense could be reduced. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to IRS for review and comment. IRS provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spectrum Management In June 2021, GAO identified eight new actions to enhance coordination between the two agencies that manage radio-frequency spectrum–a scarce natural resource–to better manage fragmentation. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-21-474 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) regulate and manage nonfederal and federal use of spectrum, respectively. When there could be interference among proposed uses, FCC and NTIA coordinate with other federal agencies using various collaborative mechanisms, such as interagency agreements and groups. In June 2021, GAO reported that these mechanisms did not fully reflect leading collaboration practices. For example, the agreements had not been updated and there were no clear processes for resolving agency disagreements. Due to FCC’s and NTIA’s respective roles, as well as the involvement of other agencies, fragmentation in managing spectrum exists. Following these practices to strengthen their collaborative mechanisms may better manage fragmentation, including agency disagreements. | ||

| New action(s): In June 2021, GAO made eight recommendations to FCC and NTIA that they should work collaboratively to update or clarify various documents and processes related to spectrum-management activities. FCC and NTIA generally agreed to implement the recommendations and, as of February 2022, had begun taking steps to address them. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to FCC and NTIA for review and comment. FCC provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate. NTIA did not provide comments on this report section. | ||

| New Action Added to Existing Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| Homelessness Programs In September 2021, GAO identified nine new actions for federal agencies to coordinate youth homelessness information and programs in order to manage fragmented services to better support communities. GAO product with new action(s): GAO-21-540 | Updates on prior actions:

| |

| Youth homelessness is a widespread problem, with one recent study estimating that one in 10 young adults experience some form of homelessness over the course of a year—such as living on the streets or temporarily staying with others. GAO identified that services supporting homeless youth are fragmented across several agencies and additional coordination among the Departments of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Health and Human Services (HHS) and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) could help improve local delivery of housing and homelessness services to young adults and minors. | ||

| New action(s): GAO recommended in September 2021 that HUD, HHS, and USICH better manage fragmented services for youth experiencing homelessness, including that HUD work with HHS to provide additional information or examples to local communities in the following areas: serving young adults through coordinated entry processes, coordinating to serve unaccompanied minors, and coordinating their programs. HUD agreed with four recommendations and neither agreed nor disagreed with two recommendations. HHS and USICH agreed with GAO’s recommendations. As of February 2022, HHS stated that USICH plans to convene an interagency working group in 2022 and that HHS would develop an action plan later in the spring. USICH suggested that HUD and HHS consider aligning their federal funding and pair services and housing resources directly to help address funding fragmentation for youth experiencing homelessness. | ||

| Agency comments and GAO’s evaluation: GAO provided a draft of this report section to HUD, HHS, and USICH for review and comment. HUD said it had no comments on this report section. HHS and USICH provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate. | ||

Appendix V: Open Congressional Actions, by Mission

Bookmark:Figure 9: Status of Congressional Actions from 2011 to 2022, as of March 2022

| Area name (links to Action Tracker) | Underlying report (links to report) | Potential benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Quarantine Inspection Fees (2013‑18) | Save tens of millions of dollars annually | ||

| Crop Insurance (2013‑19) | Save hundreds of millions annually, potentially up to $1.4 billion | ||

| Food Safety (2011‑01) | Strengthen oversight of food safety and address fragmentation | ||

| Area name (links to Action Tracker) | Action summary and status, when partially addressed | ||

| Agricultural Quarantine Inspection Fees (2013‑18) | Congress should consider taking steps to allow the Secretary of Agriculture to set fee rates to recover the full costs of the Agricultural Quarantine Inspection program. | ||

| Crop Insurance (2013‑19) | Congress should consider either limiting the amount of premium subsidies that an individual farmer can receive each year or reducing premium subsidy rates, or both limiting premium subsidies and reducing premium subsidy rates. | ||

| Congress should consider repealing the 2014 farm bill requirement that any revision to the standard reinsurance agreement not reduce insurance companies’ expected underwriting gains and direct the Risk Management Agency to (1) adjust the participating insurance companies’ target rate of return to reflect market conditions and (2) assess the portion of premiums that participating insurance companies retain and, if warranted, adjust it. | |||

| Food Safety (2011‑01) | Congress should consider commissioning the National Academy of Sciences or a blue ribbon panel to conduct a detailed analysis of alternative food safety organizational structures. | ||

| Congress should consider formalizing the Food Safety Working Group through statute to help ensure sustained leadership across food safety agencies over time. | |||

| Congress should consider directing the Office of Management and Budget to develop a government-wide performance plan for food safety that includes results oriented goals and performance measures and a discussion of strategies and resources. | |||

| Area name (links to Action Tracker) | Underlying report (links to report) | Potential benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-35 Lightning II Sustainment (2022-17) | Save hundreds of millions of dollars over several years | ||

| Foreign Military Sales Administrative Account (2019‑19) | Save tens of millions of dollars annually | ||

| Area name (links to Action Tracker) | Action summary and status, when partially addressed | ||

| F-35 Lightning II Sustainment (2022-17) | Congress should consider requiring the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, in consultation with the services and the F-35 Joint Program Office, to report annually on progress in achieving the services’ affordability constraints, including the actions taken and planned to reduce sustainment costs. | ||

| Foreign Military Sales Administrative Account (2019‑19) | Congress should consider amending the legislation that supports the Overseas Humanitarian, Disaster, and Civic Aid-funded humanitarian assistance program—DOD’s largest humanitarian assistance program—to more specifically define DOD’s role in humanitarian assistance, taking into account the roles and similar types of efforts performed by the civilian agencies. Partially Addressed: While some legislative action has been taken toward redefining what can be charged from the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) administrative account, as GAO recommended in May 2018, no related legislation had been enacted as of March 2022. In July 2019, the House passed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (H.R. 2500, 116th Cong. (2019)), which in Sections 1282(e) and 1283(a)-(b) included provisions responsive to this recommendation. Specifically, Section 1282(e) would have amended the Arms Export Control Act to remove an exclusion from the definition of administrative expenses related to military pay and unfunded civilian retirement and other benefits. Sections 1283(a) and (b) would have required DOD to review and report to Congress on options for expanding the use of FMS administrative fees. However, the Senate version of this legislation was enacted without these provisions included. Two additional bills that would have addressed this recommendation were referred to committee during the 116th Congress and did not pass before the end of the session, while one of these bills has been re-introduced during the 117th Congress. The Return Expenses Paid and Yielded Act, which was introduced in the House in February 2019, included the same provisions as H.R. 2500 (H.R. 1033, 116th Cong. (2019)). Also, in July 2019, the Acting on the Annual Duplication Report Act of 2019 was introduced in the Senate, which would have required DOD to assess and report on (1) any expenses incurred by the U.S. government in operating the FMS program that are not paid for by the administrative fee, (2) their estimated annual cost, (3) the costs and benefits of funding such expenses, and (4) any legislative changes needed to allow the FMS administrative fee to pay for such expenses (S. 2175, 116th Cong. (2019)). In September 2021, the Acting on the Annual Duplication Report Act of 2021 was re-introduced with these same provisions related to the FMS administrative account (S. 2782, 117th Cong. (2021)). GAO cannot predict the exact value of the additional expenses that would be covered through any such provisions because it is unclear how Congress may redefine what is considered an administrative expense. However, GAO estimates redefining such expenses could enhance federal revenue by at least tens of millions of dollars annually. | ||

| Area name (links to Action Tracker) | Underlying report (links to report) | Potential benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treasury’s Foreclosure Prevention Efforts (2016‑17) | Make $6 billion in previously deobligated Treasury funds available for other use | ||

| Area (links to Action Tracker) | Action summary and status, when partially addressed | ||

| Treasury’s Foreclosure Prevention Efforts (2016‑17) | Congress should consider rescinding any excess Making Home Affordable balances that the Department of the Treasury deobligates and does not move into the Housing Finance Agency Innovation Fund for the Hardest Hit Housing Markets. | ||

| Area name (links to Action Tracker) | Underlying report (links to report) | Potential benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOE’s Treatment of Hanford’s Low-Activity Waste (2018‑17) | Save tens of billions of dollars over next 2 decades | ||

| Strategic Petroleum Reserve (2015‑15) | Enhance revenue by better managing potentially excessive reserve assets | ||

| U.S. Enrichment Corporation Fund (2015‑16) | Save $600 million | ||

| Oil and Gas Resources (2011‑45) | Addressing actions in this area could result in more than $1.7 billion in additional revenues over 10 years | ||

| Area (links to Action Tracker) | Action summary and status, when partially addressed | ||

| DOE’s Treatment of Hanford’s Low-Activity Waste (2018‑17) | Congress should consider clarifying, in a manner that does not impair the regulatory authorities of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and any state, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) authority to determine, in consultation with Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), whether portions of the tank waste that can be managed as a waste type other than high-level waste and can be disposed of outside the state of Washington. | ||

| In support of the Test Bed Initiative and in a manner that does not impair any state’s authority to determine whether to accept waste for disposal, Congress should consider (i) authorizing the Department of Energy (DOE) to classify the volumes of waste corresponding to the second phase of the Test Bed Initiative for out-of-state disposal as something other than high-level waste and (ii) specifying that Resource Conservation and Recovery Act’s high-level waste vitrification standard does not apply to this volume of waste. | |||