Highlights

What GAO Found

Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit entitles children to a comprehensive set of screening, diagnostic, and treatment services. Managed care plans, which can administer the benefit, may require providers to request and receive approval before providing some diagnostic and treatment services, a process known as prior authorization.

Five selected plans GAO reviewed generally had similar processes for reviewing prior authorization requests for EPSDT services. For instance, the plans reviewed requests against medical necessity criteria and conducted a second review before denying a request. However, the plans required prior authorization for different services. For example, some selected plans required prior authorization for neuropsychological testing, speech therapy, or radiology services, while other selected plans did not.

Selected states’ oversight of managed care plans’ prior authorizations, including for EPSDT services, generally fell into the following categories:

- Review of plans’ processes: This could include reviewing plans’ policies related to time frames for notifying beneficiaries of prior authorization decisions and reviewing some of the medical necessity criteria plans used to make authorization decisions for certain services.

- Data collection: All five selected states collected data from plans on either prior authorization approvals and denials, or appeals of decisions. Three states used these data to identify trends, such as the services being denied.

- Review of a subset of denied authorizations: Two of the five selected states reviewed the appropriateness of a small subset of denials for which a state fair hearing was requested. These hearings can be requested if the plan upholds a denial on appeal, among other circumstances.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) oversight focuses on ensuring that states evaluated plans’ prior authorization policies for compliance with requirements. CMS requires states to monitor how plans manage utilization, which includes prior authorization. However, CMS has not specified how states should monitor prior authorization decisions or assessed if states are sufficiently monitoring plans to ensure they are making appropriate prior authorization decisions. Although two of five selected states reviewed a subset of service denials, GAO found that none of the selected states reviewed a representative sample of denials or used data to assess the appropriateness of the full scope of plans’ prior authorization decisions.

CMS also has not clearly defined whether plans can require prior authorization for EPSDT diagnostic and treatment services when the state Medicaid program does not have such requirements. CMS requires states' contracts with plans to define medically necessary services in a manner that is no more restrictive than the definition used by the state, but has not clearly defined whether this prohibits plans from requiring prior authorization for services when the state does not do so. Without efforts to help ensure that plans’ prior authorization decisions are appropriate and that requirements are clear, plans may deny children access to medically necessary EPSDT services to which they are entitled.

Why GAO Did This Study

The EPSDT benefit is key to ensuring that the millions of children covered by Medicaid have access to services necessary to improve or maintain their health. Most of these children receive services under this benefit through managed care plans, which may have a financial incentive to limit services. Recent reviews from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General identified concerns with plans’ decisions to deny services that were medically necessary.

GAO was asked to review children's access to EPSDT services under managed care. This report describes (1) how selected managed care plans authorize services, and (2) how selected states oversee plans’ service authorization; as well as examines (3) CMS’s oversight of states’ efforts to monitor plans’ service authorization. GAO reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from five selected states, one plan per state, and CMS. Selected states varied in geography, number of plans, and other factors. Selected plans varied in ownership and populations served.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to CMS: (1) communicate expectations for how states are to monitor the appropriateness of plans’ prior authorization decisions and confirm that states meet these expectations, and (2) clarify whether managed care plans can require prior authorization for EPSDT services when the state does not have such requirements. The agency partially concurred with each recommendation. GAO maintains that these actions are needed to help ensure adequate oversight.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to CMS:

| Number | Agency | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Health and Human Services : Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

The Administrator of CMS should communicate in writing expectations for how states are to monitor the appropriateness of managed care plans’ prior authorization decisions and take steps to confirm whether states are meeting those expectations. Such communication should include expectations related to monitoring prior authorization decisions of EPSDT services for children. (Recommendation 1) |

| 2 | Department of Health and Human Services : Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

The Administrator of CMS should clearly define whether managed care plans can require prior authorization for EPSDT services when the state does not have such requirements. This should include defining the term “non-quantitative treatment limits” as it relates to managed care plans providing medically necessary services to children in a manner no more restrictive than that used in the state Medicaid program. (Recommendation 2) |

Introduction

Dear Mr. Pallone:

Medicaid—a joint federal-state health care financing program for certain low-income and medically needy individuals—is a major source of health care coverage for children across the United States. In fiscal year 2021, the most recent data available, more than 32 million children were covered by Medicaid and about 85 percent of them were enrolled in managed care plans. [1] States contract with these plans to provide Medicaid services in return for periodic payments—typically a fixed monthly payment per beneficiary. Plans can place limits on certain Medicaid services, such as prior authorization requirements that allow plans to decide whether services are medically necessary before they are delivered. Plans can use these requirements to prevent the provision of unnecessary care. At the same time, plans may have a financial incentive to limit services because plans are paid based on the number of enrollees and not the amount of services provided. Recent reviews by the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified concerns with plans’ decisions to deny services that may be medically necessary. [2]

Medicaid beneficiaries aged 20 and under (children) are entitled to a comprehensive set of services covered by the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit. [3] Services covered under the EPSDT benefit include periodic screenings, such as physical exams, and medically necessary diagnostic and treatment services, such as laboratory tests and medical care. The EPSDT benefit generally provides children with more comprehensive coverage than Medicaid provides to adults, because states can restrict certain services for adults that must be available for children, such as dental services. As a result, the benefit can help ensure that a broad range of children’s health problems are treated as early as possible before they progress, when treatment becomes more difficult and costly.

States and the federal government share responsibility for overseeing children’s access to the EPSDT benefit, including when provided through managed care. States are responsible for ensuring that the full EPSDT benefit is available to all children covered by Medicaid, even if states contract with one or more plans to deliver some or all of those services. As such, states must ensure that their managed care contracts clearly define plans’ responsibility for covering and providing EPSDT services, and states must monitor managed care plans’ performance. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), an agency within HHS, is responsible for overseeing states’ compliance with Medicaid requirements, including those related to the EPSDT benefit and managed care. In addition, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act requires the Secretary of Health and Human Services to review states’ implementation of the requirements for providing EPSDT services and take additional steps to address any identified deficiencies. [4]

You asked us to review children’s access to EPSDT services under Medicaid managed care. This report

- describes the processes selected managed care plans use to authorize EPSDT services for children;

- describes how selected states oversee managed care plans’ authorization of EPSDT services; and

- examines CMS’s oversight of state efforts to oversee managed care plans’ authorization of EPSDT services.

To describe the processes that selected managed care plans use to authorize EPSDT services, we reviewed documentation from selected plans in five states. We first selected a nongeneralizable sample of five states that enroll children in Medicaid managed care. [5] The five selected states—the District of Columbia, Florida, Massachusetts, Missouri, and Utah—were selected to provide variation in geography, number of plans in operation, and type of managed care contracts used. [6] Within each state, we then selected one managed care plan that had been operating in the state since at least 2019 for review. This selection of plans included both for-profit and non-profit plans, and plans that serve the general Medicaid population, as well as some plans that target children with special health care needs.

We reviewed documentation from each selected plan, including utilization management program descriptions, policies and procedures related to the EPSDT benefit and prior authorization, and provider and enrollee manuals, among other documents. We focused our review on plans’ processes for authorizing diagnostic and treatment services, as CMS guidance does not allow states to require prior authorization for screening services. [7] Additionally, we interviewed plan officials about their processes for authorizing EPSDT services, including how they monitor these processes. The documents reviewed and information discussed covered 2019 through 2023 to include at least 1 year of information from before the COVID-19 pandemic. To obtain other perspectives on plans’ processes, we interviewed representatives from at least one stakeholder organization representing beneficiaries, such as legal advocates and ombudsmen, and one stakeholder organization representing providers, such as provider and primary care associations, in each selected state.

To describe how selected states oversee managed care plans’ authorization of EPSDT services, we interviewed Medicaid officials and reviewed documents from the five selected states. Documents reviewed included external quality review reports, state reviews of plans’ prior authorization processes; states’ analyses of data on approvals, denials, and appeals of prior authorization requests; and standards used by a plan accrediting entity. [8]

To examine CMS’s oversight of state efforts to oversee managed care plans’ authorization of EPSDT services, we reviewed CMS regulations and guidance related to managed care and the EPSDT benefit. We examined documentation of CMS’s oversight efforts, focusing on relevant oversight the agency conducted in our selected states. We also reviewed EPSDT research and related reports from the HHS Office of Inspector General. Further, we interviewed CMS officials about agency regulations, guidance, oversight, and research. We assessed CMS’s efforts within the context of the agency’s goals for EPSDT services and federal internal control standards—specifically, the internal control principles regarding how agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks. [9]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2023 to April 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

EPSDT Benefit

The EPSDT benefit entitles eligible children in Medicaid to a comprehensive set of medical, vision, dental, and hearing screenings, as well as any other Medicaid coverable service they may need that is identified in section 1905(a) of the Social Security Act. [10] The benefit is designed to facilitate the early detection of health problems so that children can receive diagnostic and treatment services promptly, and is generally more comprehensive than the Medicaid benefit states are required to offer adults.

Children are entitled to treatment services under the EPSDT benefit when services are determined to be medically necessary to “correct or ameliorate defects and physical and mental illnesses and conditions.” [11] According to CMS, this means that children are entitled to treatment services even if they do not cure a condition, such as when services would maintain or improve a condition, prevent it from worsening, or prevent development of additional health problems. [12] Because of this statutory language, state Medicaid programs may define medical necessity more broadly for children than for adults, as no provision requiring such coverage for adults exists in statute.

Under the EPSDT benefit, states must provide all medically necessary diagnostic and treatment services for children that can be covered by Medicaid, including those services that are optional for states to cover for adults receiving Medicaid. For example, under the EPSDT benefit, children would be covered for eyeglasses; dental services; and physical, occupational, and speech therapies if medically necessary, regardless of whether those services are covered for other populations under the state Medicaid plan.

According to CMS, services for children generally should not be subject to hard limits that may apply to services for adults under a state’s Medicaid program, such as service caps based on budgetary constraints. For example, a state may set a limitation on the number of eyeglasses or physical therapy sessions covered for adults. However, if an assessment of a child’s needs determines that services in excess of that limitation are medically necessary, then they must be covered under the EPSDT benefit.

Finally, states must act to ensure children have access to the necessary screening, diagnostic, and treatment services covered by the EPSDT benefit. In its guidance to states, CMS has emphasized that this obligation is a crucial component of the Medicaid benefit for children and makes the EPSDT benefit different from the Medicaid benefits available to adults. [13]

Medicaid Managed Care and Prior Authorization

According to analysis from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, as of fiscal year 2021, 40 states used managed care plans to provide Medicaid benefits to children. [14] Under managed care, the state Medicaid agency contracts with managed care plans and pays a set amount for each enrollee. The state makes these payments regardless of how much the plan then pays providers or the number of services enrollees use. This is in contrast to a fee-for-service delivery system in which the state pays providers for each service delivered. In a managed care arrangement, the managed care plan assumes the financial risk if its spending exceeds the state payments; however, if its spending is less than the state payment, the plan is generally permitted to retain some or all of the balance. This can create a financial incentive for plans to limit or inappropriately deny coverage or payment for necessary services.

Managed care plans generally cover all or most Medicaid-covered services, including EPSDT; however, some services may be delivered separately. [15] For instance, some states elect to deliver dental or behavioral health services on a fee-for-service basis or through a different managed care plan. Additionally, some states exempt certain populations of children from enrollment in managed care, such as children with special health care needs or children in foster care, while some states may enroll these populations in specialized managed care plans. According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, as of 2023, 12 states contract with specialized plans to cover children with special health care needs. [16]

States must permit plans to place appropriate limits on services based on medical necessity, including for some EPSDT services. [17] Plans typically do this through utilization management, a process that helps ensure that the use of services is based on medical necessity, cost efficiency, and appropriateness. One type of utilization management is prior authorization, which requires a provider to request and receive approval from an enrollee’s plan before providing a specific service. This process allows the plan to verify that the service requested is covered and medically necessary. If a plan determines that the service requested is not covered or is not medically necessary, it issues a denial to the enrollee and the provider, which indicates that it will not cover this service. [18]

Upon receiving a denial, the enrollee can appeal the decision to the plan. If the plan upholds the initial decision, then the enrollee has the right to elevate the appeal to a state fair hearing, in which a state hearing officer hears evidence about whether to uphold or overturn the plan’s decision. [19] States are required to have a fair hearing process to review denials made by plans, though states have flexibility, within certain parameters, to establish their own processes. [20]

While prior authorization can help control costs and reduce unnecessary utilization and improper payments, it can also cause enrollees to experience delays in receiving needed care. [21] CMS has recently finalized a rule that acknowledges and aims to reduce the burden associated with prior authorization. [22]

Current CMS regulations include requirements for states’ contracts with plans that are related to prior authorization processes. For example, these contracts must include provisions on the following:

- Plan policies and procedures. Contracts must include a requirement that plans and their subcontractors have in place, and follow, written policies and procedures for service authorizations, which would include prior authorizations. These policies and procedures must contain mechanisms for ensuring consistent application of review criteria for authorization decisions. [23]

- Time frames for decisions. Contracts must include state-established time frames for prior authorization decisions not to exceed 14 days—and a possible 14-day extension—for standard decisions, and 72 hours with a possible 14-day extension for expedited decisions. [24]

- Adequate notice of denials. Contracts must require plans to provide notices to enrollees regarding denials and other adverse benefit determinations. Such notices must contain certain content, including the reasons for the denial and the right to request an appeal. [25]

- Medically necessary services. Contracts must specify what constitutes “medically necessary services” in a manner that is no more restrictive than that used in the state Medicaid program. [26]

Oversight of Medicaid Managed Care Prior Authorization

Both CMS and states have oversight and monitoring responsibilities related to the EPSDT benefit and managed care plans. In 2014, CMS published a guide for states about the EPSDT benefit that compiled previously issued guidance into one document. [27] This guide addressed access to EPSDT services through managed care, noting the potential benefits of providing EPSDT services this way while emphasizing the need for a strong oversight framework to ensure compliance with federal requirements.

In 2017, CMS issued an informational bulletin that reiterated this point, stating that states using managed care to deliver the EPSDT benefit should include specifics about the benefit in their contracts to ensure children have access to the full range of covered services. [28] In addition, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act requires that, among other things, by June 2024 the Secretary of Health and Human Services issue guidance to states on Medicaid coverage requirements for EPSDT services that includes best practices for ensuring children have access to comprehensive health care services. [29]

CMS and states’ oversight and monitoring responsibilities include reviews of plans’ utilization management, such as prior authorization for EPSDT and other services. These reviews include the following:

- Contract reviews. CMS reviews and approves states’ managed care contracts. [30] CMS uses this review to ensure that contracts include required provisions related to prior authorization.

- Readiness reviews. CMS requires states to review the operational readiness of any new plans or plans enrolling new populations. [31] These reviews are intended to ensure that plans are prepared, before the contract goes into effect, to comply with all program and contract requirements, including those related to prior authorization. They are also intended to ensure the plans are prepared for the delivery of services. CMS requires states to submit the results of these reviews to the agency as part of the contract review process.

- Compliance reviews. States must have reviews conducted by an external quality review organization that assess each plan’s compliance with contract requirements and federal regulations, including those related to prior authorization, at least once every 3 years. These reviews are to be made publicly available. [32]

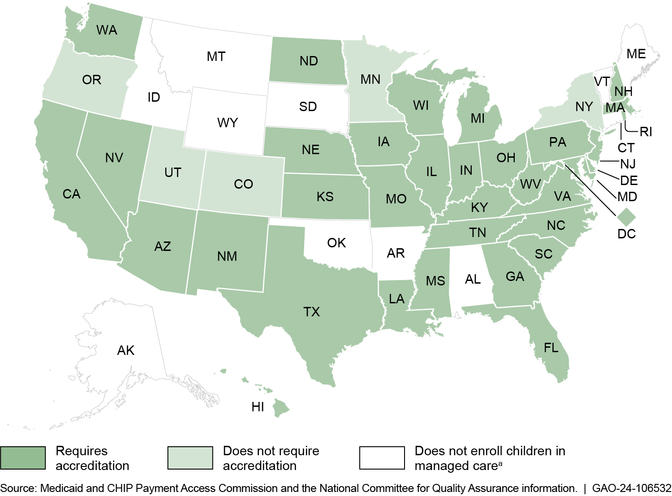

In addition, some states require plans to be accredited by a private accreditation organization, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance. (See fig. 1.) The accreditation process evaluates plans’ compliance with certain standards, which can include standards related to prior authorization. Accreditation standards can include federal Medicaid requirements and additional expectations that are not federal Medicaid requirements.

(Image title.)Figure 1: Accreditation Requirements Among States that Enroll Children in Medicaid Managed Care as of Fiscal Year 2021

(Figure note:) Note: Information on which states enrolled children in managed care is based on fiscal year 2021 data from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission. Information on states’ accreditation requirements is as of September 2022 and is from the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

(Figure note:) aWe use the term managed care to refer to comprehensive, risk-based managed care, which is the most common managed care arrangement, in which states contract with managed care plans to provide an array of services under a risk-based per person payment model. Other forms of managed care may have a limited benefit package or do not involve plans that assume financial risk for the services provided.

(Exit figure group.)Major Findings

Selected Managed Care Plans Had Similar Processes, but Differed in the Services Requiring Authorization

Selected managed care plans had similar overall processes for authorizing services for their enrollees, including for children. These similarities included their processes for reviewing prior authorization requests and appeals, as well as monitoring their processes and decisions. However, the selected plans differed in the services for which they require prior authorization, the medical necessity criteria used, and the extent to which they delegate prior authorization for certain services.

Selected Managed Care Plans Had Similar Processes for Reviewing Prior Authorization Requests and Appeals

The five selected managed care plans we examined generally had similar processes for reviewing prior authorization requests for services covered by the EPSDT benefit, including any appeals of plan decisions, and for internal monitoring of these processes and decisions. [33] We found that these processes generally applied to all services requiring authorization; that is, the processes were not specific to services covered by the EPSDT benefit. Selected plans’ policies did not require prior authorization for EPSDT screenings. However, they did require prior authorization for some diagnostic and treatment services, such as elective inpatient procedures and home health services, among others. Selected plans’ member handbooks provided information about prior authorization, such as a general description of the process and a list of what services may require prior authorization. Providers had access to more detailed information through the selected plans’ provider manuals and web-based tools.

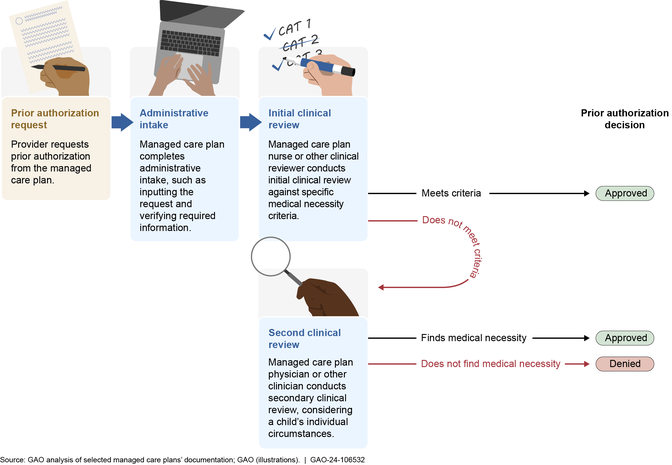

Reviewing prior authorization requests. Our review of information from the five selected plans found that the plans had similar processes for receiving and reviewing prior authorization requests, including for services under the EPSDT benefit. (See fig. 2.)

(Image title.)Figure 2: Selected Medicaid Managed Care Plans’ Processes for Reviewing Prior Authorization Requests, including for EPSDT Services

(Figure note:) Note: The process depicted above generally applied to all Medicaid managed care services requiring authorization at the five selected plans in our review, including those services covered by the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit. As of 2024, states are required to establish a time frame in their contracts with managed care plans for standard prior authorization decisions not to exceed 14 days, with a possible 14-day extension. For expedited reviews, states must establish a time frame not to exceed 72 hours for plans to review and decide on the request, with a possible 14-day extension. Beginning in 2026, states are required to reduce the time frame in their contracts with managed care plans to generally not exceed 7 days for non-expedited prior authorization decisions.

(Exit figure group.)First, a child’s provider submits a prior authorization request to the plan, often through a web-based provider portal. The selected plans we reviewed generally require that prior authorization requests include basic patient information, as well as diagnosis and proposed treatment codes and supporting medical documentation, such as medical records, test results, and provider notes.

Upon receiving a request, staff at the selected plans complete administrative intake, which can include inputting the request into an electronic records system and collecting or verifying required information. Next, a clinical reviewer—generally a licensed nurse or social worker—conducts the initial clinical review of the provider’s request. During this review, the clinical reviewer compares the child’s condition and the prior authorization request to medical necessity criteria used by the plan to determine if the requested service is appropriate. If the request meets the criteria, then the clinical reviewer approves the request.

If the initial clinical review determines the provider’s request does not meet the standard criteria, the request is elevated for a second clinical review, usually by a physician. The physician will consider the request taking into consideration other factors, such as the individual child’s needs, continuity of care, and clinical judgment, to determine if the request is medically necessary. According to selected plan officials, at this review level, the physician also considers whether the request should be covered for a child under the comprehensive EPSDT benefit. If the physician finds that the request is medically necessary, such as under the more robust EPSDT benefit definition, then the request is approved. If the physician finds that the request is not medically necessary even after applying the EPSDT benefit definition, then the plan issues a denial to the enrollee and provider. (See text box for a description of one prior authorization request reviewed by a selected plan.)

|

Example Review of an Authorization Request for Speech Therapy for a Child The managed care plan received a prior authorization request for ongoing speech therapy for a 12-year-old child with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and challenges with speech intelligibility. The child had received speech therapy for several years and the child’s provider demonstrated that the child was continuing to make progress. The standard medical necessity criteria the plan used indicates that speech therapy is generally not to exceed 24 weeks of treatment for children. However, a plan physician conducted the second clinical review of the request and decided to approve continued weekly speech therapy under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment benefit, which covers medically necessary services that maintain or improve a condition or prevent it from worsening, and under which hard limits on services are generally not allowed. |

(Table source:)Source: GAO summary of interview with selected managed care plan. | GAO-24-106532

(Exit table group.)When asked about any challenges related to the prior authorization process, officials from all five selected plans noted that they do not always receive sufficient information from requesting providers to evaluate prior authorization requests, which can make it challenging to determine medical necessity. For example, officials from two selected plans said they sometimes receive requests with missing medical documentation, and such omissions can lead to denials.

Representatives from stakeholder organizations in selected states also described challenges with the process. Representatives from provider organizations in three selected states said that the differences in prior authorization requirements among the different plans that operate within a state, such as the way requests are submitted, the information required, and the criteria against which requests are evaluated, can be difficult for providers to manage. Representatives from beneficiary organizations in two selected states also cited challenges related to the criteria used for initial clinical reviews. One of these representatives noted that these criteria are based on commercial insurance standards and may be stricter than state Medicaid standards.

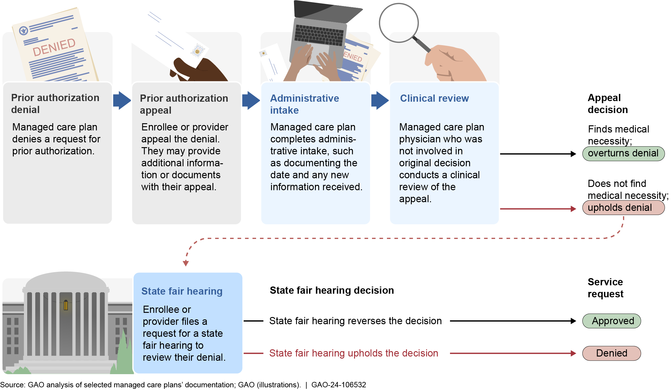

Reviewing appeals. Our review of information from five selected plans found that the selected plans also generally had similar processes for reviewing appeals of prior authorization decisions. (See fig. 3.) If a plan denies a prior authorization request, the enrollee has 60 days to appeal the denial. [34]

(Image title.)Figure 3: Selected Medicaid Managed Care Plan Processes for Appeals of Denials, including for EPSDT Services

(Figure note:) Note: The process depicted above generally applied to all Medicaid managed care appeals of prior authorization denials at the five selected managed care plans in our review, including those appeals involving the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit. Plans generally must resolve appeals and provide notice to the enrollee within a state-specified time frame not to exceed 30 days. An enrollee has no less than 90 days and up to 120 days to request a state fair hearing if the plan upholds a denial or fails to adhere to the state’s notice and timing requirements for resolving the appeal. If state law permits, and with the written consent of the enrollee, a provider or authorized representative may request an appeal or state fair hearing on behalf of an enrollee.

(Exit figure group.)When filing an appeal, an enrollee or provider submits additional information or documentation to the plan to support the medical necessity of the service requested. Appeals are reviewed by physicians who were not involved in the initial denial decision and who have the same or similar specialty as the requesting providers. To meet this standard, some selected plans use external reviewers.

During the appeal process, a physician reviews the original prior authorization request along with any additional information that was received to determine if the denial should be overturned or upheld. If the denial is upheld, the enrollee, provider, or authorized representative has up to 120 days to request a state fair hearing to review the decision. [35] If the state reverses the plan’s denial, then the plan must authorize the requested service as quickly as possible and no later than 72 hours after being notified of the hearing decision.

In addition to the appeal process, all five selected plans offer peer-to-peer reviews. [36] According to our selected plans, a peer-to-peer review takes place when the child’s provider requests a conversation with the plan about the denial, generally within 2 to 5 business days of its issuance. Officials at three selected plans said that these conversations can lead to reversing the denial, for example, if additional information is provided.

When asked about any challenges related to appeals, officials from our selected plans, as well as representatives from stakeholder organizations, described challenges related to the language and information required in denial notices. [37] Officials from three selected plans reported challenges balancing the need for language that can be easily understood with providing specific clinical information supporting the rationale for the denial. Representatives from stakeholder organizations in four selected states said that the language used in these notices to describe the rationale for the denial can be unclear and confusing, which can make filing an appeal difficult. One representative described seeing notices with a rationale for denial that appeared unrelated to the rationale submitted with the prior authorization request, causing confusion.

Stakeholders in selected states also identified other challenges with the appeal process. Representatives from stakeholder organizations in three selected states said that they have seen delays in denial notifications that are sent by mail. According to one representative, these delays can make it hard to file appeals within the required 60-day time frame. Additionally, representatives from beneficiary organizations in three selected states observed challenges with the appeal process; for example, families may not understand, or become overwhelmed by, the process and may be discouraged from going through with their appeal. A provider representative in another state expressed discouragement with the process, noting that providers request services for children because they think the services are medically necessary and put a lot of effort into the appeal process, yet in this representative’s experience the majority of denials are upheld.

Internal monitoring of prior authorization. Selected plans we reviewed used several methods to monitor prior authorization decisions and processes, including those for services under the EPSDT benefit. These methods were generally overseen by committees at the selected plans and aligned with accreditation standards. They included the following:

- Regular audits, including of denials. All selected plans conducted regular audits of decisions made by plan staff. For example, one selected plan reviewed all denials monthly, checking that the clinical information in the file was sufficient and supported the decision made. Another plan conducted a monthly review of a set number of cases from each clinical reviewer to examine documentation and the application of the appropriate criteria. Additionally, all selected plans used audits to monitor other elements of the prior authorization process, such as the timeliness and communication of decisions.

- Annual reviews. All five selected plans conducted annual utilization management evaluations, which were reviewed and approved by the plans’ quality management committees. These evaluations included review of program components, such as policies and procedures, medical necessity criteria, and oversight of decision-making.

- Subcontractor oversight, including initial and annual audits. The selected plans that delegate prior authorization of certain services to subcontractors each had policies in place to evaluate subcontractors’ policies and processes in this area. These evaluations included reviews, such as audits, before the subcontractor began its work and at least annually thereafter. Such activities were generally used to monitor compliance with contractual requirements.

Selected Managed Care Plans Differed in Services Requiring Prior Authorization and Criteria Used to Review Requests

We found three key differences in selected managed care plans’ processes for authorizing services for children: the services that require prior authorization, the medical necessity criteria that are used, and the entities that are involved in the processes. As previously discussed, CMS regulations include certain requirements for states’ contracts with managed care plans regarding prior authorization, but states have flexibility within those parameters, which may lead to such variation among states and plans. [38]

Services requiring prior authorization. The services for which selected plans required prior authorization varied, both among selected plans and compared to their states’ fee-for-service delivery systems. Among the five selected plans, we found variation in prior authorization requirements for services including speech therapy, radiology, and neuropsychological testing, among others. For example, three selected plans required prior authorization for any speech therapy visits, one required prior authorization for any additional speech therapy after four visits, and one had no prior authorization requirements for speech therapy.

We also found that all five selected plans required prior authorization for some services for which the selected states’ fee-for-service Medicaid delivery systems did not. For example, the selected plan from Missouri required prior authorization for certain physical therapy services that the state’s fee-for-service delivery system did not. Similarly, the selected plan in the District of Columbia had prior authorization requirements for psychological and neuropsychological testing, whereas the fee-for-service system did not.

Medical necessity criteria. Selected plans varied in the source of medical necessity criteria they used in reviewing prior authorization requests, such as whether they primarily used criteria developed by the plan, or criteria purchased from a third-party vendor. [39] Two of the selected plans used internally developed criteria, and the three other selected plans primarily used criteria purchased from third parties. All selected plans reported also using state criteria when available. Officials gave several reasons for why plans might develop and use their own criteria, even if they also have purchased third-party criteria, such as for prior authorization of new treatments or when third-party criteria are more restrictive than the state’s fee-for-service criteria.

Selected plans also varied in how available their criteria are to providers and enrollees. The two selected plans that use internally developed criteria post their criteria online for public access. In contrast, the three selected plans that primarily use purchased criteria said that they can only share criteria in certain circumstances, such as upon member request when a denial has been issued. [40] Representatives from stakeholder organizations in two selected states said that with limited access to criteria, they lacked the information needed to determine if denials are appropriate.

Prior authorization delegation and automation. Finally, selected plans also differed in what entities are involved in approving and denying prior authorization requests, such as subcontractors and parent companies, and in their use of software programs to grant authorizations.

- Subcontractors. Four of the selected plans used subcontractors to provide coverage of certain EPSDT services, such as dental services; these subcontractors were responsible for the prior authorization of services they covered. Some of these plans also used subcontractors for prior authorization of certain EPSDT services covered by the plan. For example, officials at one selected plan described how they used a subcontractor to review prior authorization requests for genetic testing because the plan did not have the internal expertise to stay up to date with the rapid developments in this field. Some selected plans also subcontracted prior authorization for the same types of services. For instance, both selected plans that included dental services subcontracted the coverage of those services, including prior authorization. Three selected plans subcontracted utilization management, including prior authorization, of behavioral health services, though the plans differed in whether they subcontracted only utilization management or other elements of their behavioral health coverage as well. Some selected plans subcontracted utilization management, including prior authorization, for other services, such as durable medical equipment; certain radiology services; and physical, speech, and occupational therapies. Representatives from stakeholder organizations in two selected states described challenges with managed care subcontractors not always understanding the breadth of the EPSDT benefit as compared to other coverage.

- Parent companies. Officials from all three selected plans owned by a national parent company said that the parent company was involved in their prior authorization processes, though the role that the parent company played varied. For example, at one selected plan, officials said that the department responsible for conducting initial clinical reviews was part of the parent company, not the local plan. At the two other selected plans, some authorization requests were reviewed at the parent company and others were reviewed by local plan staff.

- Software programs. Two selected plans used software programs to grant prior authorization requests for certain services, such as some advanced imaging services, and two selected plans delegated prior authorization of certain services to a subcontractor who used such software. According to officials from the selected plans, providers use an electronic system to submit their authorization requests and answer certain questions about the request that align with the medical necessity criteria used by the plan. If the request meets criteria, then it is automatically approved. Officials said that these programs are generally used for services that either have often been approved in the past or those with straightforward medical necessity criteria. While these software programs can be used to approve requests, officials reported that a request would not be denied based solely on the software. Rather, any requests that do not meet the criteria specified in the software are reviewed by plan staff to determine whether they should be approved.

Additionally, while we found that all selected plans audited prior authorization decisions, selected plans varied in whether they looked at these decisions by age. Such analysis could allow for specific review of denials and appeals among children. Of the three selected plans that serve both adults and children, only one reported conducting age-specific analysis. Officials at this selected plan noted that they used such analyses to review denial rates for certain services by age and that this review had resulted in a decision to remove the prior authorization requirement for some services covered under the EPSDT benefit that had a high approval rate.

Selected States’ Oversight of Managed Care Plans’ Prior Authorizations Included Reviewing Processes and Collecting Data

Selected states’ oversight of managed care plans’ prior authorizations, including for EPSDT services for children, generally fell into three categories: (1) reviewing plans’ processes; (2) collecting data from plans on approvals, denials, and appeals; and (3) reviewing a small subset of denied authorizations. Not all of the selected states conducted oversight activities in each of these categories.

Selected States’ Review of Managed Care Plans’ Processes

All of the five selected states (District of Columbia, Florida, Massachusetts, Missouri, and Utah) took steps to review managed care plans’ prior authorization processes, including for EPSDT services for children, to ensure they complied with requirements. These steps could include conducting applicable readiness reviews for new plans, compliance reviews, and reviews of plans’ medical necessity criteria. Most of the states also required plans to be accredited; accrediting entities review plans’ processes, including those for conducting prior authorizations.

Readiness reviews. Both of the selected states that added new plans or populations to their managed care programs between January 2019 and July 2023 (District of Columbia and Missouri) conducted readiness reviews and initially found that plans’ policies and procedures were incomplete. [41] For example, the District of Columbia’s readiness review of a new plan initially found that the plan’s policies and procedures documents related to prior authorization had not been finalized. Specifically, the documents contained comments and changes that had not been accepted and were missing signatures from the plan’s executives. The plan responded by submitting finalized policies and procedures, according to the state’s review documentation.

Compliance reviews. Most of the selected states had compliance reviews conducted for their managed care plans to assess the plans’ compliance with contract requirements and federal regulations. These reviews were conducted by the states’ external quality review organizations and the results were included as part of the states’ external quality review reports. Specifically, from January 2019 to August 2023, four of the five selected states (District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Missouri, and Utah) published a compliance review as part of their external quality reviews. [42] Although compliance reviews are required at least every 3 years, Florida did not conduct or publish a compliance review during this time. According to documents submitted by the state to CMS, Florida has developed a proposal to conduct compliance reviews and report results by April 2024.

The compliance reviews conducted on our selected plans varied in terms of how the selected states assessed compliance with requirements related to prior authorization processes. For example:

- In two of the four states (District of Columbia and Utah), the reviews assessed examples of plans’ correspondence with enrollees for compliance with time frames for notifying enrollees about prior authorization decisions. [43] These two reviews found that the plans we selected from those states did not always notify enrollees within the required time frames.

- In contrast, in the other two states (Massachusetts and Missouri), the reviews only looked at whether plans’ policies were consistent with the required time frames and found that the policies of the plans we selected from those states fully complied. Reviewing a plan’s policies alone would not indicate whether the plan adheres to its policies, but these two states also used other methods of monitoring whether plans met required time frames for notifying enrollees of prior authorization decisions. [44]

The selected states’ external quality reviews included recommendations to address instances when compliance reviews found that plans did not fully comply with requirements related to prior authorization processes. These reviews also tracked plans’ progress in implementing these recommendations over time. However, according to the external quality review reports, our selected plans did not always fully address recommendations included in their reviews to achieve compliance. For example, annual compliance reviews conducted by the District of Columbia’s contractor from 2019 through 2022, the most recent information available, found a lack of full compliance with requirements related to the resolution of expedited appeals for our selected plan.

Medical necessity criteria. Three of the five selected states (Massachusetts, Missouri, and Utah) conducted ad hoc reviews of medical necessity criteria that plans use to make prior authorization decisions. Specifically, the selected states reviewed plans’ medical necessity criteria for specific services as the need arose, according to officials from these states. The states did not, however, routinely review plans’ medical necessity criteria for all services.

For example, Utah conducted a review of all plans’ medical necessity criteria for Hepatitis C drugs to reduce provider burden and help ensure patient continuity of care when switching plans. This review identified the similarities and differences across plans and the state’s fee-for-service delivery system regarding the type of clinical information that had to be submitted for a beneficiary to be eligible for coverage. Utah’s review found that plans required certain clinical documentation that was not required under fee-for-service. Utah officials noted that the state did not identify a need to take any action in response to the review.

Accreditation. Four of the five selected states (District of Columbia, Florida, Massachusetts, and Missouri) required plans to be accredited, which can include assessments of plans’ prior authorization processes. Three of these states required plans to obtain accreditation from the National Committee for Quality Assurance, and the fourth required accreditation from this accrediting entity or others.

As part of the accreditation process, the National Committee for Quality Assurance reviews plans’ prior authorization processes for compliance with its standards. This includes assessing plans’ policies and procedures and, for some standards, assessing documentation for a random sample of prior authorization decisions for compliance. For example, documentation is reviewed to assess compliance with standards on the collection of relevant clinical information for making prior authorization decisions, timeliness of decisions, and denial notices.

Selected States’ Collection of Data on Approvals, Denials, and Appeals

All of the five selected states collected some data from managed care plans on either approvals and denials, or appeals of prior authorization decisions, for all types of services, including EPSDT services.

- Approvals and denials data. Three of the selected states (Florida, Massachusetts, and Missouri) collected data from plans on approvals and denials of prior authorization requests. Florida and Missouri collect data on each prior authorization request, such as type of service, outcome, date of outcome decision, and enrollee information such as member identification number. Missouri’s data identified the specific service requested, while Florida’s data identified the broader service category requested, such as home health services or physical therapy, among others. In contrast, Massachusetts collects aggregate data including the number of requests and the number and rate of approvals, modifications to requests, and denials. [45]

- Appeals data. Four of the selected states (District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Missouri, and Utah) collect data from plans on each appeal of denied prior authorization requests. These data include the type of service of the appeal, appeal decision (such as if the denial was upheld or overturned), amount of time taken to resolve the appeal, and enrollee information such as member identification number.

Three of the selected states (Florida, Massachusetts, and Missouri) reviewed the data they collected to identify trends over time, such as trends in the types of services being denied or appealed, or whether plans were meeting prior authorization procedural requirements, such as those pertaining to timeliness of decisions, according to officials from those states. Officials from two of the selected states (Missouri and Utah) identified potential data reliability issues, which may limit the usefulness of their data to identify potential issues with the authorization of EPSDT services. For example, Missouri officials found that the data may contain duplicate records of prior authorization requests. An official also noted that the state should work with plans on data validation in the future.

Selected States’ Review of a Subset of Denied Authorizations

Two of the five selected states (Massachusetts and Utah) had processes for reviewing the appropriateness of some prior authorization decisions by managed care plans, specifically for the small subset of prior authorization denials for which a state fair hearing was requested. Such hearings can be requested after an enrollee exhausts a plan’s internal appeals process. [46] States’ reviews of these fair hearing requests were not limited to cases related to children and EPSDT; rather, states reviewed cases related to any managed care enrollees or benefits.

Massachusetts officials reported that the state Medicaid agency’s medical directors try to review all of plans’ prior authorization denials scheduled for a fair hearing to better understand why the plan initially denied the service. If the state Medicaid agency’s medical directors disagree with a plan’s denial, they inform the plan and attempt to achieve a resolution to avoid the need for a fair hearing. Following these communications, in many instances the cases are resolved with the plan overturning its initial denial, which results in the fair hearing being cancelled, Massachusetts officials said. If the hearing proceeds and a medical director is available to attend, the medical director will voice the state’s opinion to the hearing officer, who will take it into consideration when deciding whether to overturn the denial.

Utah has a structured process in which a hearing officer can request that state Medicaid officials review a plan’s prior authorization denial before the fair hearing to determine if the requested service would have been approved under the state’s fee-for-service delivery system. The hearing officer can factor this review into their decision. For example, in 2023, Utah’s Medicaid officials identified that plans denied services to treat a skin condition that the state would have approved under fee-for-service. According to state officials, the plans ultimately approved the services. (See fig. 4 for a description of those services.)

(Image title.)Figure 4: Vitiligo Treatment Denied by Medicaid Managed Care Plans, but Would Have Been Approved by the State

(Exit figure group.)

(Exit figure group.)In general, only a small number of denials are appealed or result in a request for a state fair hearing. According to a 2023 report from the HHS Office of Inspector General that examined 2019 data from 115 plans, enrollees appealed 11 percent of prior authorization denials. Of the denials that were upheld by plans, 2 percent were appealed to a state fair hearing. [47] In addition, in a March 2024 report that examined 33 states’ reported data on fair hearings from 2022, we found that 2 percent of managed care appeals were taken to a state fair hearing. [48] Among our selected states, for example, officials from the District of Columbia noted that there are generally few fair hearings related to prior authorization denials for children. According to the state’s data reported in its 2022 Managed Care Program Annual Report, the selected plan we reviewed had 66 appeals and five fair hearing requests for enrollees aged 26 and under.

CMS Oversight of Managed Care Prior Authorizations Focuses on Processes, but Not the Appropriateness of Decisions

CMS checks states’ contracts with managed care plans and states’ oversight of plans’ processes for authorizing EPSDT services, such as assessing whether states evaluated plans’ prior authorization policies and procedures for compliance with requirements. CMS does not assess whether states review the appropriateness of plan’s prior authorization decisions. Furthermore, CMS has not clearly defined whether plans can require prior authorization for EPSDT services when the state does not have such requirements.

CMS Checks States’ Managed Care Contracts for Required Provisions and States’ Reviews of Plans’ Prior Authorization Processes

According to CMS officials, the agency assesses states’ oversight of managed care plans’ authorization of services by reviewing the contracts states have with plans, as well as states’ reviews of plans’ prior authorization processes, including through readiness and compliance reviews. CMS uses these assessments to help ensure states conduct oversight of plans’ prior authorization processes for EPSDT services, as well as other Medicaid covered services.

Contract review. CMS reviews states’ contracts with plans to check that they include required provisions, including provisions related to prior authorization. For example, as part of the review, CMS checks to see if contracts include a requirement that plans have in place and follow written policies and procedures for processing prior authorization requests. [49] From January 2019 through January 2024, CMS reviewed contracts in four of five selected states and confirmed they included these provisions, according to our review of CMS documents. As of January 2024, CMS officials said they had a pending review of contracts for the fifth selected state.

Readiness review. CMS takes steps to ensure that states are assessing the readiness of their plans to serve Medicaid enrollees. As noted earlier, CMS requires states to conduct readiness reviews of new plans or plans enrolling new beneficiary populations to help ensure that plans are prepared to comply with all program and contract requirements, including those related to prior authorization. To assist with these reviews, CMS developed a list of activities that states and plans should take to demonstrate this readiness. For example, plans should have developed policies and procedures for utilization management and provided staff with appropriate training. States must submit documentation of their readiness reviews to CMS. CMS reviews this documentation as part of its contract review and may follow up with the state. As previously noted, two of our selected states (District of Columbia and Missouri) conducted required readiness reviews between January 2019 and January 2024. After reviewing the results of the two states’ readiness reviews, CMS requested that Missouri provide additional information, although that information was not specific to prior authorization, according to our review of CMS documents.

CMS has developed a readiness review tool that it is piloting with states that includes additional requirements related to prior authorization. For example, the tool requires states to review plans’ prior authorization policies and procedures, medical necessity criteria, and related documents. As of January 2024, CMS officials said this tool was not yet finalized and for this reason they could not confirm how CMS may use the tool for oversight of plans’ prior authorization. As such, it is not yet clear if, or how, this tool will affect CMS’s oversight moving forward.

Compliance review. CMS conducted oversight of states’ external quality reviews of plans, including oversight of the states’ compliance reviews, which are used to evaluate if plans’ policies and procedures meet federal requirements related to prior authorization and other topics. CMS has assessed whether states evaluate each plan’s compliance and include relevant information on the extent to which each plan complies with requirements in external quality review reports. This information must be included in external quality review reports at least once every 3 years.

According to CMS documentation, the agency found two of our five selected states (Florida and Massachusetts) had not fully met the compliance review requirement. Specifically, CMS found the following:

- Florida did not include a compliance review in at least one external quality review from the three reporting cycles spanning 2018 through 2021, as required. CMS directed the state to meet this requirement, but found in 2023 that Florida had not yet included a compliance review in its external quality review. In response, CMS held a call with Florida officials and reviewed the state’s proposal to conduct the review and publish results by April 2024.

- Massachusetts reported on compliance review results for some, but not all, plans during reporting cycles from 2018 through 2020. After CMS directed the state to meet the requirement, Massachusetts’ included the information in its 2021 external quality review. CMS found no deficiencies with this review.

According to agency officials, as states have increasingly met requirements for reporting results from compliance reviews, CMS has begun to focus on improving states’ managed care programs. Specifically, CMS has begun to follow up with states on gaps that are reported in the results of compliance reviews. For example, in 2021, CMS found that the District of Columbia fully met requirements for conducting compliance reviews and reporting results. However, these results showed that multiple plans’ compliance with a standard on the availability of services was lower than their compliance with other standards. CMS requested that the District of Columbia propose steps to address this lower level of compliance.

In addition to the reviews conducted by CMS, in 2022, the agency contracted with NORC at the University of Chicago to research the EPSDT benefit. [50] During a webinar that CMS held for states in December 2023, NORC discussed strengths and areas for improvement it identified based on its review of states’ and plans’ written materials on the EPSDT benefit. For example, NORC researchers identified that most of the plans’ provider and enrollee handbooks they reviewed contain information on how to access dental care covered by EPSDT, something it noted was a strength. However, they found that some of these handbooks specified limits on dental services—such as on fluoride varnish, orthodontia, oral examinations, and cleanings—without acknowledging CMS’s prohibition on hard limits on EPSDT services that are medically necessary.

During the webinar, CMS encouraged states to use information from NORC’s review to assess the compliance of relevant policies and materials. CMS also offered to provide states with technical assistance on EPSDT in the form of quarterly state webinars, one-on-one state-specific assistance, peer workgroups, learning collaboratives, and other resources. CMS officials told us they planned to follow up with states that NORC identified as having potential areas of non-compliance. In addition, the contracted EPSDT research is to include assessments of 30 states’ policies and procedures related to access to EPSDT services and other topics. These assessments are scheduled to take place over 3 years, beginning in the fall of 2024.

CMS Oversight Does Not Ensure that States Review the Appropriateness of Managed Care Plans’ Prior Authorization Decisions

CMS requires states to monitor all aspects of managed care, including plans’ utilization management, which would include prior authorization decisions for EPSDT services. [51] However, CMS has not taken steps to ensure that states review whether managed care plans are consistently making appropriate prior authorization decisions by approving requests for medically necessary EPSDT or other services. Specifically, CMS has not communicated in writing its expectations for states’ monitoring of the appropriateness of plans’ prior authorization decisions, including decisions related to the denial of services under the EPSDT benefit. CMS officials explained they had focused their EPSDT guidance on other topics instead of prior authorization decisions. As a result, CMS is not able to confirm whether states’ monitoring is meeting expectations. [52]

Reviewing plans’ prior authorization decisions to ensure that medically necessary services are approved is important because plans may have financial incentives that could lead them to inappropriately limit access to services, including EPSDT services. CMS officials acknowledged that this incentive may exist and that oversight should address this risk. Oversight of plans' prior authorization decisions would be consistent with CMS’s stated goal of the EPSDT benefit, which is to ensure that individual children get the health care they need when they need it. [53] Furthermore, the importance of such oversight has grown as managed care enrollment has expanded. In fiscal year 2021, over 85 percent of children covered by Medicaid were enrolled in comprehensive managed care. [54]

The HHS Office of Inspector General has audited plans’ denials and found instances in which plans incorrectly denied requested services—such as pediatric skilled nursing for overnight care—or had justified denials by citing incorrect information in denial notices, which may indicate the denials were inappropriate. [55] The HHS Office of Inspector General also found three reasons for concern that some Medicaid managed care enrollees may not be receiving all medically necessary health care services intended to be covered: (1) the high number and rates of denied prior authorization requests by some plans, (2) the limited oversight of prior authorization denials in most states, and (3) the limited access to external medical reviews. [56]

Similarly, we found that selected states’ monitoring of plans’ prior authorization decisions for EPSDT services was limited and does not address all aspects of managed care, as required. Two selected states had processes to review a small subset of denials that had been appealed to state fair hearings, but none of the selected states reviewed all decisions or a representative sample of service denials, which could allow states to estimate the accuracy of all decisions. [57] Although all five selected states collected data from plans either on all prior authorization approvals and denials, or on all appeals of denials, they did not use these data to assess the plans’ prior authorization decisions either overall or for EPSDT services specifically, according to state officials. Furthermore, none of the selected states reviewed data for children separately from data for other managed care enrollees, such as adults, which would be necessary to review prior authorization decisions specific to EPSDT.

In the absence of actions by CMS to ensure state oversight of plans’ prior authorization decisions, CMS may not achieve its goal of ensuring that individual children get the health care they need when they need it. In addition, the absence of such actions is inconsistent with federal internal control standards that state that agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving program objectives. [58] As a result, CMS does not know whether states are taking the necessary steps to help ensure that plans approve medically necessary EPSDT services.

CMS officials said they had focused their EPSDT guidance on topics other than oversight of prior authorization decisions, but added that the agency potentially could review information related to plans’ prior authorization that states are now reporting to CMS in their Managed Care Program Annual Reports. These reports include data on the number of appeals and fair hearings, and CMS officials said they could follow up with states to discuss these data as appropriate. However, in a recent report on Medicaid managed care, we found that the data in these reports have limited usefulness for this purpose. [59] For example, we found that CMS does not require states to report the number of denials or the extent to which appeals of plans’ denials are overturned. Furthermore, the information reported is for all enrollees—it is not reported separately for children, limiting its usefulness for oversight of EPSDT services.

In addition, the number of appeals and fair hearings may not provide a complete picture of the appropriateness of plans’ authorizations, as enrollees and providers may not appeal denials of services they consider to be necessary. For example, a beneficiary stakeholder group told us that families are often overwhelmed or discouraged by the appeals process and may opt to pay out-of-pocket for services rather than appeal a denial. Also, a representative from a pediatric clinic we spoke to told us that the clinic providers generally did not request state fair hearings after beneficiaries’ initial denials were upheld by plans on appeal, even when the providers believed the requested services were medically necessary.

CMS officials also said they respond to complaints they receive about plans not authorizing EPSDT benefits. According to agency officials, they have not received any such complaints in our selected states during our review period. However, this absence of complaints does not necessarily indicate that plans’ prior authorization decisions are appropriate. We found that the two selected states that reviewed fair hearing requests identified instances in which plans denied services that would be approved under Medicaid fee-for-service or state officials reported disagreeing with some plan denials. This indicates plans’ denials were not always consistent with states’ contracts with plans, which must include a requirement for plans to furnish services in an amount, duration, and scope that is not less than what is furnished under Medicaid fee-for-service, according to CMS regulations. [60]

CMS Has Not Clearly Defined What Treatment Limits Managed Care Plans Can Apply for EPSDT Services for Children

As part of CMS’s requirement that states monitor all aspects of managed care, states must oversee the prior authorization requirements managed care plans place on EPSDT services. However, CMS has not clearly defined for states whether plans may require prior authorization for EPSDT-related diagnostic and treatment services for which the state’s fee-for-service delivery system does not require prior authorization. As a result, states may lack the clarity needed to conduct sufficient oversight to ensure that managed care plans are not delaying or denying access to EPSDT services.

Specifically, CMS regulations require that states’ contracts with plans specify what constitutes “medically necessary services” in a manner that is no more restrictive than that used in the state program, but CMS has not clearly defined how this requirement applies to children enrolled in managed care. [61] This medically necessary services requirement, which applies to EPSDT services—as well as all other Medicaid managed care services—notes that “non-quantitative treatment limits” on medically necessary services must be no more restrictive than in the state’s program. In addition, CMS’s EPSDT guidance summarizes this requirement. [62]

However, neither CMS regulations related to the medically necessary services requirement, nor the agency’s EPSDT guidance defines the term “non-quantitative treatment limits.” This term is defined in other CMS regulations and guidance that address parity for mental health and substance use disorder benefits. [63] As it relates to parity, CMS specifies that the term “non-quantitative treatment limits” includes prior authorization requirements. [64] Furthermore, we found that CMS’s Managed Care Contract Review Tool refers to the definition in the parity regulations when describing the medically necessary services requirement, which indicates the definition is relevant in this context.

If this definition of “non-quantitative treatment limits” applied to the medically necessary services requirement, it would appear to prohibit plans from requiring prior authorization for services when the states they operate in do not have a prior authorization requirement for the same services, such as in the states’ fee-for-service delivery system. However, CMS officials told us the parity regulations and guidance do not apply to the medically necessary services requirement and that the agency had not defined the term “non-quantitative treatment limits” in the context of this requirement. [65]

As we noted earlier, CMS’s goal for the EPSDT benefit is to ensure that individual children get the health care they need when they need it, and CMS requires that plans provide enrollees, including children, with access to medically necessary services in a manner that is no more restrictive than that used in the state program. In the absence of clear CMS regulations and guidance on how “non-quantitative treatment limits” apply to medically necessary services under EPSDT, states may not exercise sufficient oversight to ensure plans cover medically necessary services in a manner that is no more restrictive than states’ programs. As noted earlier in this report, we found that each of the five plans we reviewed required prior authorization for some EPSDT services that did not have such a requirement under the states’ fee-for-service delivery system. However, officials in selected states varied in their views as to whether plans were allowed to have prior authorization requirements for services that do not have such requirements under the state’s fee-for-service delivery system. For example, Missouri and Utah officials told us they were allowed, but Massachusetts officials said they were not and the state would follow up on our finding to ensure alignment between managed care and fee-for-service prior authorization requirements. While additional prior authorization requirements that are not present under states’ fee-for-service delivery system can prevent unnecessary care, they also can result in delaying or denying access to EPSDT services that are medically necessary to correct or ameliorate children’s physical and behavioral health conditions.

Conclusions

Prior authorization can be a valuable tool for preventing the provision of unnecessary services and avoiding unwarranted costs. However, given the potential financial incentive for managed care plans to limit expenditures on care, it is essential that state Medicaid programs and CMS ensure that plans make appropriate authorization decisions and avoid inappropriately denying covered services that are medically necessary. This is even more important as it relates to services for children given the more comprehensive set of Medicaid services they are entitled to through the EPSDT benefit.

Existing oversight by CMS and selected states focus on the processes plans use to make prior authorization decisions. Helping ensure that plans have the required or needed processes in place is a good first step. However, it is also essential to ensure that plans are implementing those processes in a way that results in the appropriate approval of medically necessary services. Furthermore, in order to ensure that plans make appropriate decisions, states and plans must clearly understand whether plans can require prior authorization for EPSDT services when the state program does not have such requirements.

Absent systematic efforts to monitor whether plans’ prior authorization decisions are appropriate for EPSDT services and clarity on what services can have prior authorization requirements, CMS and states cannot know whether children receive the health care services they need and to which they are entitled.

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix I, HHS partially concurred with both of our recommendations and described activities under way that would inform future actions related to our recommendations. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In regard to our first recommendation that CMS should communicate in writing expectations for how states are to monitor the appropriateness of managed care plans’ prior authorization decisions and take steps to confirm whether states are meeting those expectations, HHS noted the agency has begun gathering information on states’ current practices for reviewing prior authorization denials. HHS indicated that it plans to use this information to assess whether there is a need to adopt additional monitoring and oversight requirements. Adequate state monitoring is essential to ensure that plans approve medically necessary services for children. However, we found that selected states’ monitoring of plans’ prior authorization decisions for EPSDT services was limited. As such, we maintain that it is important for CMS to communicate how states are expected to monitor the appropriateness of plans’ prior authorization decisions and work to confirm whether states are meeting those expectations. This would help CMS ensure that states effectively oversee plans and thereby help to ensure individual children get the health care they need.

Regarding our second recommendation that CMS should clearly define whether managed care plans can require prior authorization for EPSDT services when the state does not have such requirements, HHS recognized the need for additional clarity on this issue. In addition, HHS recognized the need to clearly define the term “non-quantitative treatment limits,” which was also part of our second recommendation. HHS indicated that it plans to use information it has begun gathering to inform these needed clarifications. We appreciate that CMS acknowledges the need for clarification and maintain that the clarifications we recommend are necessary to ensure plans meet the existing requirement to cover medically necessary services in a manner that is no more restrictive than states’ Medicaid programs.