DOD FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

Action Needed to Enhance Workforce Planning

Report to Congressional Committees

October 2024

GAO-25-105286

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-105286. For more information, contact Asif A. Khan at (202) 512-9869 or khana@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-105286, a report to congressional committees

October 2024

DOD FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

Action Needed to Enhance Workforce Planning

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD financial management has been on GAO’s High Risk List since 1995. Achieving a clean audit opinion on its department-wide financial statements remains a goal that DOD has not yet attained. DOD’s audit readiness depends on ensuring that its financial management workforce has the needed skills.

In connection with the Government Management Reform Act of 1994 provision for us to audit the U.S. government’s consolidated financial statements, GAO compared DOD’s financial management workforce planning activities to five principles for effective strategic workforce planning. GAO’s work was performed at the key DOD components responsible for financial management: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), military departments, and Defense Finance and Accounting Service. GAO also interviewed DOD officials and analyzed workforce data.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to DOD to (1) develop a strategy to identify functions performed by contractors to help identify workforce needs and to help inform competency and capability assessments and (2) develop procedures requiring documented succession plans. DOD did not concur with the contractor workforce recommendation, stating that specific skillsets are determined by contractors. GAO maintains that to conduct effective department-wide financial management workforce planning, DOD needs to identify functions performed by contractors. DOD concurred with GAO’s succession planning recommendation.

What GAO Found

Strategic workforce planning focuses on using long-term strategies to acquire, develop, and retain an organization’s total workforce to meet the needs of the future. When done effectively, strategic workforce planning can help the Department of Defense (DOD) determine its financial management needs, deploy strategies to address skill gaps, and contribute to results.

|

Strategic workforce planning key principle |

Evaluation |

|

Involve top management, employees, and stakeholders in workforce planning |

● |

|

Determine needed critical skills |

◒ |

|

Develop strategies to address gaps in critical skills |

◒ |

|

Support workforce planning strategies that use existing human capital flexibilities |

● |

|

Monitor and evaluate progress toward human capital and programmatic goals |

● |

Legend: Generally consistent = ●; Partially consistent = ◒; Not consistent = ●

Source: GAO analysis of DOD documents and interviews. | GAO-25-105286

DOD’s financial management workforce planning policies and associated processes, practices, and activities were generally consistent with three of the five principles: (1) involving top management, staff members, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan; (2) supporting workforce planning strategies that use existing human capital flexibilities; and (3) monitoring and evaluating progress toward human capital goals. For example, to support workforce planning strategies, DOD uses incentives, recruitment initiatives, hiring flexibilities, and a financial management certification program.

DOD was partially consistent with principles on determining critical skills needed and developing strategies to address skill gaps.

· DOD has policies and procedures in place to identify the competencies needed for its civilian and military financial management workforce. For example, DOD has about 43,000 civilian employees within the Office of Personnel Management’s Accounting, Auditing, and Budget Group, 0500, as of fiscal year 2021. By contrast, DOD does not know how many financial management contractor staff it has or what functions they collectively perform. This presents a major challenge in determining workforce needs.

· DOD has developed a wide range of hiring and training strategies for its financial management staff. However, DOD has not developed and implemented documented succession policies and plans. As a result, DOD increases the risk that it will be unable to quickly fill expected gaps in positions.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AFR |

agency financial report |

|

ASI |

Agency Staffing Initiative |

|

BSO |

budget submitting office |

|

DCAT |

Defense Competency Assessment Tool |

|

DCPAS |

Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service |

|

DFAS |

Defense Finance and Accounting Service |

|

DHA |

direct-hire authority |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FIAR |

Financial Improvement and Audit Remediation |

|

FTE |

full-time equivalent |

|

GS |

General Schedule |

|

HR |

human resources |

|

LOE |

line of effort |

|

OFCM |

Office of the Secretary of Defense Functional Community Manager |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

OUSD(C) |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 10, 2024

Congressional Committees

The mission of the Department of Defense’s (DOD) financial management workforce is to ensure that DOD’s budget and expenditures support the national security objectives of the United States. In fiscal year 2023, DOD received total appropriations of about $1.1 trillion, an increase of about $74 billion from fiscal year 2022. The department reported approximately $3.8 trillion in assets as of September 30, 2023, an increase of approximately $253 billion from fiscal year 2022. DOD’s spending makes up about half of the federal government’s discretionary spending.

Sound financial management practices and reliable, timely financial information are important to ensuring accountability over DOD’s extensive resources. Achieving this goal is a significant challenge, given the worldwide scope of DOD’s mission and operations; the diversity, size, and culture of the organization; and the magnitude of its reported assets, liabilities, and annual appropriations.

In confronting this challenge, serious and continuing financial management problems have adversely affected the economy, efficiency, and effectiveness of DOD’s operations. Accordingly, DOD financial management has been on our High Risk List since 1995. DOD remains the only major federal agency that has been unable to receive a clean audit opinion on its department-wide financial statements.

As of fiscal year 2021, the DOD financial management workforce consists of approximately 60,000 federal civilian and military personnel and is supported by an unknown number of contractor personnel who perform financial management-related functions.[1] Appendix II provides further data, based on our analysis, of the approximately 43,000 federal employees who make up DOD’s federal civilian financial management workforce, as of fiscal year 2021. According to a congressional panel on Defense Financial Management and Auditability Reform, ensuring that the workforce is adequately staffed, skilled, and well-trained is crucial to DOD’s ability to improve financial management and audit readiness. Appendix II also includes information on operations research personnel, who provide support for DOD’s financial management workforce and business operations.

In GAO’s 2021 High Risk Update, we reported that DOD continued to face financial management personnel capacity challenges.[2] We also reported that DOD acknowledged that its succession planning was inconsistent and that it had difficulty retaining millennials.[3] In our 2023 High-Risk List update, we reported that the DOD Financial Management Strategy for Fiscal Years 2022-2026 continues to focus on the need to build and maintain a premier financial management workforce.[4]

We performed this work in connection with the statutory requirement for GAO to audit the U.S. government’s consolidated financial statements, which cover all accounts and associated activities of executive branch agencies, including DOD. This includes efforts and activities that are needed to support and maintain a financial management workforce, which is needed to support and sustain sound financial management.[5]

We compared DOD’s financial management workforce planning policies and associated procedures, practices, and activities to principles of effective strategic workforce planning.[6] Our work was performed at the key DOD components responsible for financial management: the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) (OUSD(C)), the military departments,[7] and the Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS).[8]

At each of these DOD components, we analyzed financial management and workforce planning documentation. We compared our analyses to five principles for workforce planning.[9] These principles are highly relevant to DOD’s efforts in workforce planning.[10] For each principle, we assessed DOD’s financial management workforce planning policies and associated procedures, practices, and activities to determine the extent to which DOD’s guidance included key supporting actions that constitute the key principle.

Regarding the composition of DOD’s federal civilian financial management workforce, we obtained DOD data from the Defense Manpower Data Center for all appropriated-fund DOD federal civilian financial management employees categorized in the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) 0500 job series from fiscal year 2012 through fiscal year 2021. These were the data that were the most recent available at the time of our data request. We also obtained data for the 1515 job series (operations research), which, according to DOD documentation, helps facilitate DOD’s business transformation and management innovation efforts. We summarized the data by military department or workforce size, job series, race or ethnicity, gender, and age (see app. II). To assess the reliability of the DOD workforce data, we reviewed documentation associated with the collection, structure, and elements of the DOD data and conducted electronic testing of the data for completeness and consistency. We also interviewed DOD officials who were knowledgeable about the management and uses of the data. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes.[11]

We also interviewed cognizant senior officials at OUSD(C), the military departments, and DFAS. In addition, we reviewed OPM policies, which require agencies to monitor and address skill gaps. See appendix I for additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2021 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

As stated in the DOD Financial Management Strategy for Fiscal Years 2022-2026, the financial management workforce’s responsibility is defined as supporting commanders, program managers, and procurement professionals, among many other stakeholders, to deliver essential defense mission capabilities.

DOD has been working toward a clean audit opinion on its department-wide financial statements for more than 30 years and estimates that it will not obtain a clean opinion, at least until near the end of the current decade.[12] According to the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, DOD shall ensure that it has received an unqualified opinion on its financial statements by not later than December 31, 2028.[13]

Prior Reports Address DOD’s Financial Management Workforce

As discussed below, the department’s and the services’ fiscal year 2023 agency financial reports (AFR), along with other reports, provide further details on the workforce-related challenges that they face:

In June 2024, DOD’s Inspector General reported that DOD components did not effectively manage Financial Improvement and Audit Remediation (FIAR) contracts or report accurate information.[14] Also, DOD did not use FIAR contract resources efficiently to meet FIAR goals.[15] Instead, DOD components used FIAR contracts to support non-remediation efforts and tasks unrelated to the full financial statement audits. According to the report, this occurred because the DOD components used their FIAR contracts to overcome staffing shortfalls. Additionally, OUSD(C) did not provide clear guidance on what tasks were appropriate under FIAR efforts and allowed the DOD components to decide which tasks they deemed necessary to support FIAR efforts.

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) recommended that DOD (1) strengthen guidance by defining FIAR tasks for DOD components, (2) develop and implement a process to ensure the accuracy and completeness of information reported in budget submissions, and (3) monitor for conflicting audit remediation tasks and verify the appropriateness of the tasks and funds spent for FIAR contracts. In addition, the OIG also recommend that the Army and Navy develop and implement a centralized process to monitor their FIAR efforts, develop and implement a strategy to align FIAR contracts to DOD audit priorities and goals, and develop a plan to reduce the use of contractors as components transition from remediation efforts to sustaining an unmodified audit opinion.[16]

For DOD’s AFR for 2023, the DOD OIG noted the following department-wide material weaknesses in the area of personnel and organizational management: (1) DOD’s average civilian time to hire may negatively affect the department’s ability to attract quality candidates to fill open resource needs on a timely basis; (2) the large number of personnel systems, pay systems, and special human resources (HR) authorities and flexibilities used to manage the civilian workforce has caused excessive complexity and variability in HR processes; and (3) DOD has not implemented a centralized personnel accountability system and standardized reporting formats to enable consistent management of military personnel HR processes across the geographical combatant commands.[17]

In the Army’s AFR for fiscal year 2023, the independent auditor reported deficiencies related to training within the financial management workforce. The auditor noted that the Army should (1) ensure that personnel are adequately trained in their areas of responsibilities and understand and comply with existing policies, (2) perform monitoring of whether controls are implemented and operating as designed, and (3) train personnel to recognize and accurately record transactions.[18]

In the Air Force’s fiscal year 2023 report, the independent auditor stated that the Air Force lacked sufficiently trained resources within its financial management workforce.[19] The auditor recommended that the Air Force (1) continue to develop training to enhance competencies in internal control concepts and accounting topics; (2) clarify the competencies, roles, responsibilities, and expectations of employees in relation to internal control over financial reporting; and (3) develop appropriate succession and contingency plans for key roles.[20]

Regarding the Navy’s fiscal year 2023 audit, the independent auditor noted that the Navy lacked oversight of the financial reporting service provider. The auditor recommended that the Navy provide training to individuals responsible for reviewing and approving journal vouchers. The auditor also noted inadequate documentation of budget execution policies and procedures, including controls. The auditor recommended that the Navy provide training to all Budget Submitting Office (BSO) personnel on how to (1) appropriately implement the policy for bulk obligations and (2) design and implement monitoring procedures to ensure compliance with the policy.[21]

We reported in March 2023 that DOD officials stated they did not have a strategic approach for workforce planning for all staff who support financial management systems.[22] We recommended that DOD establish a mechanism for ensuring that it takes a strategic approach to workforce planning for the government and contractor staff who develop and maintain its financial management systems. DOD partially concurred with the recommendation and cited existing workforce planning and oversight activities that are underway.

In 2018, we reported that long-standing, uncorrected deficiencies within DOD’s financial management systems, including those related to financial manager qualifications, continued to negatively affect the department’s ability to manage and make sound decisions on missions and operations. For example, we noted that DOD’s decentralized management environment may affect financial management personnel’s ability to gain the requisite expertise to develop and implement needed corrective action plans.[23]

In June 2017, we reported that current budget and long-term fiscal pressures on the department increased the importance of strategically managing DOD’s human capital.[24] We found that DOD had taken steps to develop better information about the skill sets possessed and needed within the department’s federal civilian, military, and contractor workforces, but needed to take further actions to complete a workforce mix assessment, improve the methodology for estimating workforce costs, and address skill gaps in critical workforces. Specifically, we noted that DOD should determine the appropriate mix of the military and civilian and contractor workforce in its strategic workforce plan.

In addition, we reported that DOD established financial improvement and audit readiness guidance, implemented training programs to help build a skilled financial management workforce, and developed corrective action plans to track the remediation of audit issues.[25] However, we also stated that DOD continued to identify the need for enough qualified and experienced personnel as a challenge to achieving its goals of financial improvement and audit readiness. We noted that DOD made progress in these areas, but substantial work remained for DOD to further control costs and manage its finances.[26] Lastly, we reported that the changing nature of federal work and a potential wave of employee retirements could produce gaps in leadership and institutional knowledge, which may aggravate the problems created by existing skill gaps.[27]

Key Principles for Strategic Workforce Planning

We previously reported on the importance of strategic workforce planning. Such planning focuses on developing long-term strategies for acquiring, developing, and retaining an organization’s total workforce (including full- and part-time federal staff and contractor personnel) to meet the needs of the future.[28] When done effectively, strategic workforce planning can help DOD determine its financial management needs, deploy strategies to address skill gaps, and contribute to results.

Developing and implementing a workforce plan can assist agencies in achieving their missions and strategic goals. We previously identified five key principles for effective strategic workforce planning.[29]

1. Involve top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan.

2. Determine the critical skills needed to achieve current and future programmatic results.[30]

3. Develop strategies that are tailored to address gaps in number, deployment, and alignment of human capital approaches for enabling and sustaining the contributions of all critical skills.

4. Support workforce planning strategies that use existing human capital flexibilities.

5. Monitor and evaluate the agency’s progress toward its human capital goals and the contribution that human capital results have made toward achieving programmatic goals.

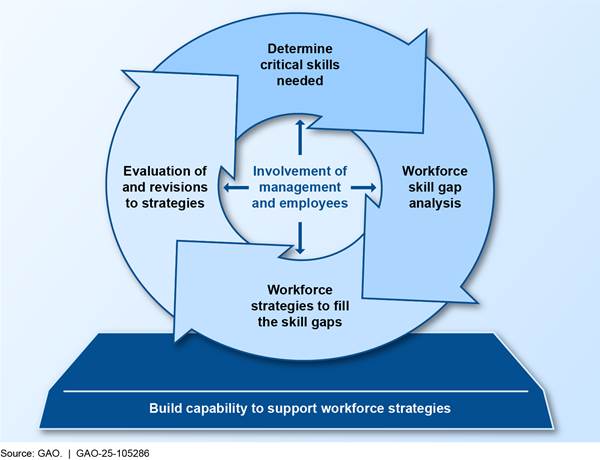

As shown in figure 1, workforce planning is a continuous process whereby agencies reevaluate and assess workforce needs on an ongoing basis.

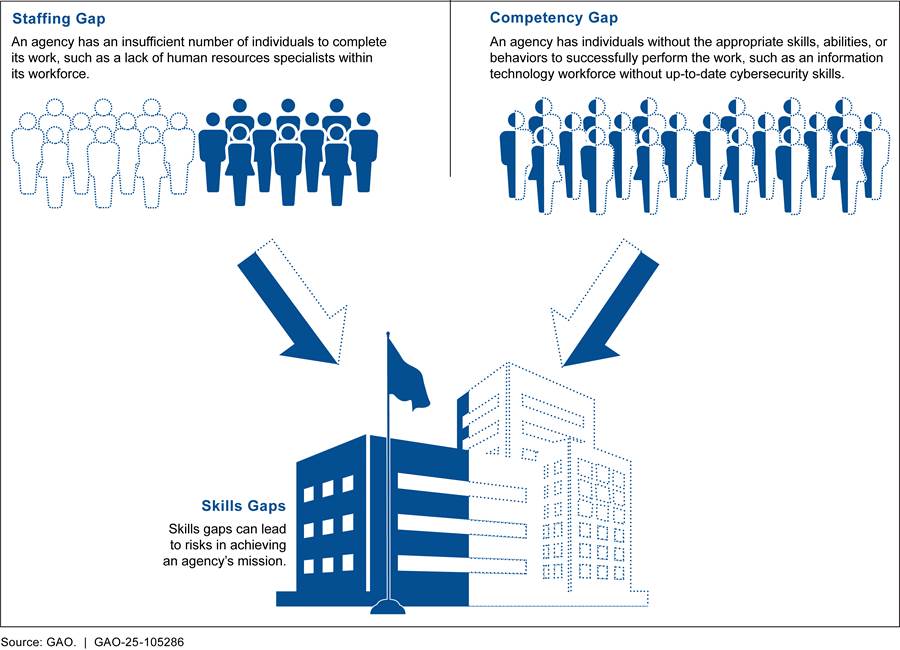

As part of the human capital management process, agencies assess skill gaps within the workforce. A skills gap may consist of (1) a vacancy gap (also known as a staffing gap), in which an agency has an insufficient number of individuals to complete its work, or (2) a competency gap, in which an agency has individuals without the appropriate competencies, abilities, or behaviors to successfully perform the work.[31] Figure 2 shows how staffing and competency gaps can lead to skills gaps in the workforce.

DOD Is Generally Consistent with Most Strategic Workforce Key Principles, but Additional Actions Are Needed

DOD’s financial management workforce planning policies and associated processes, practices, and activities were generally consistent with the principles of (1) involving all levels of staff in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan; (2) supporting workforce planning strategies that use existing human capital flexibilities; and (3) monitoring and evaluating progress toward human capital goals. For example, to support workforce planning strategies, DOD uses incentives, recruitment initiatives, hiring flexibilities, and a financial management certification program.

DOD’s financial management workforce planning policies associated procedures, practices, and activities were partially consistent with key principles related to (1) determining critical skills needed and (2) developing strategies to address skills gaps. Specifically, DOD does not have policies and procedures for including contractors in its needs assessment process. Also, as it relates to the collective competencies and capabilities of contractors, DOD does not know how many contractors it has or what functions they collectively perform. This presents a major challenge in determining workforce needs. In addition, although DOD has developed a wide range of hiring and training strategies for its financial management workforce, DOD has not developed and implemented documented succession policies and plans. As a result, DOD increases the risk that it will be unable to quickly fill expected gaps in positions. See table 1 for a summary of our assessment.

|

Strategic workforce planning key principle |

Evaluation |

|

Involve top management, employees, and stakeholders in workforce planning |

● |

|

Determine needed critical skills |

◒ |

|

Develop strategies to address gaps in critical skills |

◒ |

|

Support workforce planning strategies that use existing human capital flexibilities |

● |

|

Monitor and evaluate progress toward human capital and programmatic goals |

● |

Legend: Generally consistent = ●; Partially consistent = ◒; Not consistent = ●

Source: GAO analysis of DOD documents and interviews. | GAO‑25‑105286

DOD Involved All Workforce Levels and Communicated Its Workforce Plans across the Department

Based on our analysis of DOD financial management workforce planning information and interviews with officials, we determined that DOD was generally consistent with the key principle of involving top management, employees, and other stakeholders in strategic workforce planning. Key supporting actions that assist in the implementation of this key principle are (1) ensuring that top management sets the overall direction and goals of workforce planning; (2) involving employees and stakeholders in developing and implementing future workforce strategies; and (3) establishing a communication strategy to create shared expectations, promote transparency, and report progress.[32]

Ensure That Top Management Sets the Overall Direction and Goals of Workforce Planning

To demonstrate top management’s involvement in the strategic workforce planning process, the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer and the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) published the DOD Financial Management Strategy for Fiscal Years 2022-2026. The document outlines DOD’s mission, vision, and strategic goals and objectives for its financial management workforce. The Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service’s (DCPAS) Strategic Workforce Planning Guide for 2019 provides the process for how top management in DOD assists in workforce action planning. For example, the guide states that Office of the Secretary of Defense functional community managers assist in identifying available authorities, flexibilities, and training tools for workforce action planning. Top management also assists in vetting strategies and identifying availability of funding, other constraints, and risks.

According to 10 U.S.C. 135 and DOD Directive 5118.03, the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) is the principal advisor to the Secretary of Defense for budgetary and fiscal matters, including financial management, accounting policy and systems, financial systems, budget formulation and execution, contract audit, audit administration, and general management improvement programs.

OUSD(C)’s Strategic Workforce Plan for 2019 through 2023 states that OUSD(C)’s community manager for the Financial Management Functional Community partners with community managers from the military departments on financial management workforce development across the department.[33] According to OUSD(C) officials, OUSD(C) shares best practices with the military departments, but the military departments manage their own financial management workforce requirements. These officials stated that they encourage the military departments to adopt these best practices, but OUSD(C) does not make any formal directives to the military departments.

In addition to the strategic workforce planning policies and processes cited above, the following are examples of how DOD involves top management in its workforce planning efforts:

· OUSD(C). In coordination with financial management personnel from across the department, including financial management and human capital subject matter experts across DOD, OUSD(C) develops multiyear financial management strategic workforce plans. The plans are approved by the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Meeting minutes OUSD(C) provided show that the office hosted meetings for top leadership of the military departments and DFAS, during which the military departments’ top leaders participated directly in workforce planning activities.

· Army. According to minutes from OUSD(C)’s senior leadership group meetings, senior officials from the Army’s financial management workforce were part of discussions concerning updates to the Financial Management Certification Program, strategic workforce planning, and financial management training.[34] Army officials stated that the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Financial Management and Comptroller has increased senior leadership presence at the Army commands by visiting monthly to meet and greet the financial management civilian and military workforce. Army officials provided the agenda for one of these meetings, where concepts related to strategic workforce planning, as part of the financial management strategy, and the fiscal year 2024 audit were discussed.

· Air Force. Air Force officials stated that its Functional Advisory Council composed of military general officers and civilian executives provides strategic-level direction and oversight of development programs and activities for the workforce. According to the Charter of the Air Force Financial Management Development Team, the Air Force Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary is the civilian functional manager and co-chairs the officer and civilian development teams. Additionally, the Deputy Assistant Secretary, Budget, is the officer functional manager and acts as co-chair for the officer and civilian development teams. The Executive for Enlisted Matters is the chair for the enlisted development team.

· Navy. Navy Instruction 7000.27D governs the Navy’s financial management comptroller organizations.[35] The Navy’s BSOs approve subordinate commands’ comptroller organizations.[36] The Navy’s February 2022 workforce synchronization presentation states that the Navy’s executive governance board and an oversight committee oversee operations of three working groups that address developing workforce competencies, revamping the internship program, and improving hiring and retention.

· DFAS. According to the DFAS fiscal years 2022-2026 strategic plan, the DFAS Strategic Council, the oversight body for strategy execution, monitors and receives reports on DFAS’s portfolio of initiatives. DFAS officials told us, and the DFAS fiscal years 2017-2021 written strategic plan confirmed, that DFAS senior executives act as both priority outcome leaders, who are responsible for direct oversight for execution of strategic initiatives that fall within their focus areas, and priority champions, who oversee the actions of the priority outcome leaders. According to the fiscal years 2017-2021 written strategic plan, DFAS senior executives provide guidance and direction to ensure that the stated focus area results and priority outcomes are achieved.

Involve Employees and Other Stakeholders in Developing and Implementing Future Workforce Strategies

The DCPAS Strategic Workforce Planning Guide for 2019 provides guidance to DOD on the development of the strategic workforce plan and outlines how all levels of the workforce are involved in developing the plan and creating a communication strategy. DCPAS develops and oversees human resources programs for the DOD workforce.

The DOD Financial Management Strategy for Fiscal Years 2022-2026 notes that measuring employee engagement and satisfaction can be an opportunity to implement data-driven change. Employee satisfaction is an important factor in an organization’s workforce awareness and retention efforts. As we previously reported, an annual survey can help ensure that newly appointed agency officials maintain momentum for organizational change.[37] Another benefit is that if agencies, managers, and supervisors know that their employees will have the opportunity to provide feedback each year, they are more likely to take responsibility for influencing positive change.[38] Officials at OUSD(C), the Air Force, the Navy, and DFAS reported that they conduct employee satisfaction surveys.

In addition to the policies mentioned above, the following are examples of how DOD involves employees and other stakeholders in its workforce planning efforts:

· OUSD(C). OUSD(C)’s financial management strategy for 2022 through 2026 incorporates input from across DOD, including budget analysts, data analysts, accountants, and auditors. Additionally, OUSD(C) officials told us that employee input is factored into year-to-year implementation plans through feedback on training and forums and through the OPM Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey.[39] As part of involving other stakeholders in developing the strategic workforce plan, OUSD(C) officials provided us meeting minutes from their quarterly Financial Management Functional Community manager meetings. At these meetings, DOD gathers stakeholder input from the military departments to provide more transparency.

· Army. As previously stated above, Army senior leadership held monthly visits at the commands to meet and greet the financial management workforce. Army officials stated that they gather employee feedback through the OPM Federal Employment Viewpoint Survey. Also, the Army’s website provides a summary of notable Federal Employment Viewpoint Survey results for 2022 and 2023. The Army published an announcement for the 2024 Federal Employment Viewpoint Survey, which indicated that the survey would launch in May 2024.

· Air Force. The Air Force’s previous strategic workforce plan, the fiscal years 2019 through 2023 Human Capital Strategy, states that development teams meet twice annually to provide strategic-level direction, orchestrate personnel developmental opportunities, develop policies, and provide senior-level succession planning. The Air Force conducts workforce development surveys for the civilian and military financial management workforce. According to Air Force officials, surveys are conducted electronically, and the information received is used to inform and develop executive-level action plans, as appropriate. The Air Force published an announcement regarding the 2024 Federal Employment Viewpoint Survey, which indicated that the survey would launch in June 2024.

· Navy. The Navy conducted its Workforce Readiness Initiative, a multi-month project starting in the spring of 2021 that consisted of numerous workshops to gather feedback on various topics affecting the BSOs. These topics included the Financial Management Certification Program, upskilling the workforce, automation and outsourcing of activities, and adopting best practices from other commands. In May 2024, Navy officials stated that the Workforce Readiness Initiative has been superseded by the Navy Financial Management Strategy and Fiscal Year 2024 Implementation Plan. The implementation plan summarizes the Navy’s fiscal year 2023 accomplishments for the financial management workforce and describes its strategic goals and objectives for fiscal year 2024, including timelines for completion.

Beginning in June 2022, the Navy implemented a quarterly financial management employee satisfaction survey, which is called the Pulse Survey. As evidence of these efforts, the Navy provided workforce metrics containing the results of this survey. The latest Pulse Survey conducted was in April 2024. The survey called for employee feedback on a variety of topics, including job satisfaction, available training opportunities, and whether personnel have sufficient resources to perform their jobs effectively.

· DFAS. DFAS officials noted that the organization uses the Organizational Assessment Survey, administered by OPM, as a tool to assess the agency’s overall organizational climate. DFAS’s survey results show that areas measured include leadership, employee engagement and recognition, inclusion, and communication.

DFAS officials described the survey as a tool for employees to share their perceptions in many critical areas, including their work experiences, their agency, and its leadership. According to DFAS officials, the results provide agency leaders insight into areas where improvements have been made as well as areas where improvements are needed. In response to the employee feedback results from that survey, DFAS stated that it developed action plans to address identified issues.

Establish a Communication Strategy to Create Shared Expectations, Promote Transparency, and Report Progress

The military departments and DFAS have established communication strategies that create shared expectations, promote transparency, and report progress to their respective financial management workforces and stakeholders by publishing strategic workforce plans. DCPAS’s Strategic Workforce Planning Guide for 2019 provides a template for developing DOD’s strategic workforce plans, which provide core requirements and activities that are essential in workforce planning. The template includes the following sections: executive summary, introduction, strategic planning alignment, current workforce analysis, future workforce analysis, gap analysis, workforce action planning, and execution and monitoring. The guide also includes a cross-functional map showing that communication should take place at various levels of the organization.

As part of the strategic workforce plan development process cited above, the following are examples of communication strategies OUSD(C), the military departments, and DFAS used to create shared expectations, promote transparency, and report progress:

· OUSD(C). OUSD(C) used its fiscal years 2022 through 2026 financial management strategy and the DOD Financial Management Functional Community Implementation Plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2026 to communicate with its financial management workforce and stakeholders. For example, OUSD(C) set a goal of cultivating a skilled and inspired financial management workforce. The Financial Management Strategy states that some of the objectives established to meet this goal include building and maintaining a premier financial management workforce, optimizing and evolving financial management training solutions, and fostering a financial management community of practice.

· Army. The Army used its 2028 Financial Management Strategy and the 2024 Campaign Plan for the Financial Management Strategy to communicate with its financial management workforce and noted the importance of working with external and internal stakeholders and organizational partners across the Army. The 2028 Financial Management Strategy identifies the Army’s strategic goals, the objectives that will be used to reach those goals, how progress will be measured, and what success looks like. For each strategic goal, the campaign plan highlights the progress made in 2023 toward that goal and what further actions are planned for 2024.

· Air Force. The Air Force used its fiscal years 2022 through 2026 Financial Management Strategic Plan to communicate with its financial management workforce and highlighted the importance of strengthening partnerships with stakeholders across the enterprise. The document describes the Air Force’s goals for its financial management workforce, defines objectives for reaching these goals, and explains the desired outcomes.

· Navy. The Navy used the fiscal years 2022 through 2026 Financial Management Strategy to communicate with its financial management workforce and stated that achieving its goals requires collaboration with stakeholders across the department. The Financial Management Strategy outlines the Navy’s goals and objectives, the steps needed to achieve them, and ways to measure outcomes.

· DFAS. DFAS used its fiscal years 2022 through 2026 Strategic Plan and the fiscal years 2022 through 2026 Human Capital Strategic Plan to communicate with its financial management workforce and describes the importance of collaborating with stakeholders and strengthening partnerships with customers. The Strategic Plan and the Human Capital Strategic Plan highlight DFAS’s strategic goals and desired outcomes.

In addition, DFAS provided a document entitled DFAS Human Capital Framework Communication Plan. It lists planned communications that take place within the agency and the method of delivery (e.g., meeting, email, newsletter, etc.). The list also includes the target audience for which the message will be tailored and the frequency of communications (e.g., annually, semiannually, quarterly, monthly, biweekly, weekly, etc.). According to the document, DFAS has established a centralized direct line to its Accountability Team, which allows any member of any planned communication to offer feedback or ask questions.

DOD Determined the Competencies Needed for Civilian and Military Personnel but Lacks Data on Contractor Personnel

Based on our analysis of DOD financial management workforce planning information and interviews with officials, we determined that DOD was partially consistent with the key principle of determining critical competencies that will be needed to achieve current and future programmatic results. The key supporting action that assists in the implementation of this key principle is to ensure the critical competencies and staffing needs are identified and clearly linked to the agency’s mission and long-term goals. As part of this process, agencies should conduct needs assessments to determine the number of employees needed with specific competencies and roles within the financial management workforce. This is especially important as changes in national security, technology, budget constraints, and other factors change the environment within which federal agencies operate.

Competency development involves determining the competencies that are required for specific financial management roles. This creates a foundation for the workforce to be able to perform the functions needed to support financial management. Competency assessments or needs assessments, on the other hand, focus on the existing abilities that employees possess and additional competencies that the workforce needs to achieve the mission. These are important because it allows DOD to periodically check with its financial management workforce and gauge how work is changing and what additional competencies, if any, are needed to meet the workforce’s needs.

While DOD has processes in place to identify the competencies needed for its federal civilian and military financial management workforce, DOD lacks data about the contractor personnel who support financial management functions across the department. Without documented needs assessment processes in place that account for collective competencies and capabilities and the functions performed by contractor personnel, the department is challenged to conduct comprehensive strategic planning for its financial management workforce. For example, DOD has about 43,000 civilian employees who have positions within the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) “Accounting, Auditing and Budget Group, 0500.” By contrast, DOD does not know how many financial management contractor staff it has or what functions they collectively perform. This presents a major challenge in determining workforce needs.

DOD Developed Competencies and Needs Assessment Processes for Its Civilian and Military Financial Management Workforce

OUSD(C)’s Administrative and Personnel Policies to Enhance Readiness and Lethality Final Report for 2018 states that the Financial Management Functional Community developed a list of 24 competencies, which were adopted by the Federal Chief Financial Officer Council in 2015 for use across the federal government. The policies state that these competencies serve as more specific and quantifiable job qualifications in place of traditional statements of knowledge, competencies, and abilities.

OUSD(C), the military departments, and DFAS took various actions to develop competencies for the civilian and military workforce and conduct needs assessments. OUSD(C) officials stated that the departments manage their own respective needs assessments, as they are best equipped to determine their individual unit needs. The following are examples of DOD’s processes and efforts regarding the development of needs assessments and competencies for civilian and military personnel:

· OUSD(C). OUSD(C) officials provided a list of financial management competencies that were developed for the civilian workforce. DOD officials stated, and officials from the military departments confirmed, that OUSD(C) determines and validates competencies for the federal civilian financial management workforce across the department. DOD officials also told us that the Financial Management Functional Community spent years developing competencies for the federal civilian financial management workforce. DOD officials stated that subject matter experts within the Financial Management Functional Community developed certification levels and, within these levels, identified the specific competencies that would be needed. DOD developed and issued its department-wide financial management competencies for its civilian workforce in December 2011.[40]

DOD officials previously stated in a February 2022 information request that the competency models are processed by the DOD competency team using the Defense Competency Assessment Tool (DCAT). DCAT tracks and manages employee and supervisory competency assessments and provides a gap analysis of current competencies against target-level proficiency.

According to DCPAS’s website, as part of the competency development process, DOD identifies tasks that need to be completed and drafts competencies that are needed for these tasks. From there, the department conducts panels by subject matter experts to refine the draft competencies and proficiency-level statements for those competencies.

DOD’s DCAT Competency Assessment Report Interpretation Guide for Employees states that DCAT is a tool for validating DOD occupational series competency models and assessing competency gaps across the civilian workforce. According to the guide, DOD civilian employees are invited to self-assess their proficiency levels in their occupational competencies through DCAT, and participation in DCAT is voluntary. From there, supervisors assess each employee’s proficiency level for the each of the competencies required for the employee’s position. The variance between the employee’s rating and the supervisor’s rating is then measured, as well as the target proficiency rating. Competency gaps are identified by differences between the supervisor’s rating and the target proficiency rating.

In a March 2024 information request, DOD officials stated that the department was migrating to DCAT Cloud, which would be used as a competency development tool rather than an employee validation tool. According to DOD officials, all formal and written guidance on the newly deployed system is being developed for official integration through fiscal year 2025. DOD officials stated that the new system will be used for competency evaluations, climate assessments, and trend analysis.

· Army. Related to competency development, Army officials provided documentation of the positions in its military financial management workforce and the competencies needed for each position. Also, the Army’s personnel development guide for commissioned officers identified the competencies they need to possess as military financial management personnel. For determining competencies for military personnel, Army officials stated that the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Financial Management and Comptroller provides the direction, approves guidance for workforce criteria, and approves workforce structure.

For needs assessments, Army Regulation 690-950, Career Program Management, states that the Army Civilian Career Program Proponency System continually monitors and assesses the current capabilities of the Army’s civilian workforce and program requirements. The system (1) supports civilian functional manpower requirements for total force planning and the strategies needed to build the Army civilian workforce to meet those requirements, (2) identifies required competencies and competency proficiency levels for employees to meet current and future missions and communicates those requirements to appropriate stakeholders, (3) compares the current competency level requirements to the current proficiency levels to determine current competency gaps and gap closure methodologies, and (4) identifies career paths to provide a competency-based career map for Army civilians to enhance their career planning and development.

· Air Force. Related to competency development, Air Force officials provided documentation of the positions in the Air Force military financial management workforce and the competencies identified for each position. The Air Force created development roadmaps for enlisted and officer personnel in the military financial management workforce. These roadmaps provide leadership, experience, and education expectations for military personnel over the course of 20 years. The roadmaps also detail institutional and occupational competencies these personnel are expected to acquire, such as financial operations, accounting, and financial analysis. Air Force officials stated that the major commands and field commands decide the competencies needed for military financial managers.

Regarding needs assessments, the Air Force’s 2015 Guide for Civilian Workforce Planning provides the steps for conducting these. The guide states that the Air Force should determine and analyze workforce supply, demand, and discrepancies. This includes workforce changes such as attrition rates, anticipated mission changes, and labor market forecasts. The guide also states that the Air Force should consider what competencies will be needed to complete specialized, unique, and noncomplex tasks and how to recruit employees with needed competencies.

· Navy. For competency development, the Navy provided documentation of the positions in its military financial management workforce and the competencies identified for each position. Also, Navy officials stated that competencies from DOD’s Financial Management Certification Program are used for the civilian and military financial management workforces. They also stated that any competencies that are needed beyond what is established in the certification program are determined by the BSOs. Navy officials stated that the Navy’s military workforce uses DOD-set competencies.

As it pertains to needs assessments, the Navy worked with a consultant in 2021 and 2022 to assess its financial management workforce. The consultant worked with the Navy to identify the competency capability of the financial management workforce as well as strategies that can be used to help retain personnel. Navy officials stated that this is the first time such an assessment was conducted; moving forward, the Navy plans to conduct it every 3 to 4 years to assess how actions the department took have affected the workforce. Navy officials also provided us with the 2020 Secretary of the Navy Instruction 7000.27D, which requires that commands support training and development opportunities for comptroller staff.

· DFAS. Regarding competency development, DFAS officials stated that they follow DOD policy related to decisions on competencies for the financial management workforce. DFAS officials stated that they do not recruit military personnel from the Financial Management Functional Community, and they do not determine the number of military personnel in their financial management workforce. According to DFAS officials, military personnel are sent to DFAS’s financial management workforce by orders from their respective military departments. In January 2022, DFAS officials stated that they had 13 military personnel from the Navy and three military personnel from the Marine Corps in their financial management workforce.

For needs assessments, DFAS officials stated that they did not publish a DFAS instruction implementing DOD Instruction 1400.25, volume 431, because they believed there were sufficient details, guidance, and information in the DOD Instruction. These officials provided documentation showing that they conduct yearly centralized training needs assessments. The officials added that they survey the leadership of each organization within DFAS, spanning from first-line supervision to the senior leaders. The survey solicits information on competencies, skill sets, and proficiency levels as well as emerging developmental requirements, priorities, and future needs. Officials stated that the Learning and Development Division will then perform quarterly check-ins with organizational leaders to see if needs are being met and if any new training needs have emerged.

DOD Has Limited Information on Specific Financial Management Functions Contractor Personnel Are Performing

To conduct a comprehensive needs assessment, OUSD(C), the military departments, and DFAS need to know what specific functions contractor personnel are performing and what skills are associated with performing those functions. With this information, DOD would be better positioned to determine if competencies exist or could be developed within the civilian and military financial management workforce and whether DOD financial management personnel could perform these functions instead of contractors.

OUSD(C), the military departments, and DFAS do not have policies and procedures for including contractors in its needs assessment process. Also, OUSD(C), the military departments, and DFAS could only tell us what general areas contractor personnel work in, but not the numbers of contractors nor the specific functions that they collectively perform. Without knowing the collective competencies and capabilities of contractors and what functions contractors are performing, DOD cannot identify the competencies associated with these functions and if these competencies can be factored into the needs assessments process. As a result, DOD’s needs assessment process is incomplete.

DOD Instruction 1400.25, volume 250, DOD Civilian Personnel Management System: Civilian Strategic Human Capital Planning, states that DOD needs to identify current and projected civilian manpower requirements, including expeditionary requirements within the context of total force planning, needed to meet DOD’s mission. Volume 250 defines total force as all active and reserve military, civilian, and contractor employees of DOD. According to volume 250, the Strategic Human Capital Management Executive Steering Committee will review and recommend appropriate functional community structure, mission-critical occupations, and resources for functional community planning to better manage the total force.

However, officials across the DOD Financial Management Functional Community stated that they have limited information about contractor personnel supporting their respective financial management workforces because they do not track this information. Federal law and DOD policy requires DOD officials to implement guidelines and procedures to ensure that consideration is given to using DOD civilian and military personnel to perform functions that contractor personnel perform.[41]

As part of the workforce mix decision process, DOD Instruction 1100.22, Policy and Procedures for Determining Workforce Mix, states the following:

if a DOD Component has a military or DOD civilian personnel shortfall, the shortfall is not sufficient justification for contracting an inherently governmental function. Likewise, a personnel shortfall is not sufficient justification for contracting activities that are closely associated with inherently governmental functions if contracting the activity would result in an inappropriate risk. Personnel shortfalls shall be addressed by hiring, recruiting, reassigning military or DOD civilian personnel; authorizing overtime or compensatory time; mobilizing all or part of the Reserve Component (when appropriate); or other similar actions.

The following are examples of challenges DOD faces regarding data collection for contractor personnel:

· OUSD(C). OUSD(C) officials stated that it is difficult to determine what financial management work is being performed by contractor personnel. OUSD(C) officials stated that this is because there are many different types of contracts that have financial management components but are not purely financial management contracts. OUSD(C) officials stated that DOD would have to parse out all the roles on the contract to find the financial management positions and that they do not know if there is a way to track all financial management-related contracts across the department.

· Army. Army officials stated that contractor support is used differently across its financial management workforce depending on the needs of the organization acquiring the support. Officials noted that these needs can vary from conducting audit remediation activities to performing data analytics.

· Air Force. Air Force officials told us they do not know exactly how many contractor personnel there are but that contractor personnel work within the following areas: budget, financial analysis, audit, accounting, cost, and information technology. Air Force officials stated that while they can track the federal civilian and military financial management workforces’ responsibilities regarding financial statements and their preparation, a contractor’s work depends on what is in their performance work statement. Air Force officials stated that the challenge with determining the work of contractors is that their performance work statements could include also administrative work, which is difficult to parse out.

· Navy. Navy officials told us that the department does not track its contractor personnel, but that contractor personnel fulfill positions in support of audit and financial management, including systems support, implementation, migration, and sustainment.

· DFAS. DFAS officials told us that they use the Contract Services directorate to oversee all the contracts within DFAS. DFAS officials noted that mission areas and corporate organizations can request services contracts to fulfill needed support, if required and appropriate. However, these officials noted that functions that are inherently governmental cannot be legally contracted out. DFAS officials did not provide information on what general areas in the financial management workforce contractor personnel are working in.

DOD is required by law to prepare an inventory of contracted services for certain contract actions exceeding $3 million and then submit to Congress a summary of the inventory, including contracts where contractor personnel will augment DOD’s workforce and contracts closely associated with inherently governmental functions.[42] The statute states that the Secretary of Defense must submit the inventory summary to Congress no later than the end of the third quarter of each fiscal year. The statute also states that the inventory summary should contain information such as the functions and missions performed by the contractor personnel and the number of contractor personnel being used, expressed as full-time equivalents (FTE).[43] We reported that DOD estimated it spent $184 billion to $226 billion on contractor services from fiscal year 2017 through fiscal year 2020.[44]

Our past work on DOD’s inventory of contracted services found that data collection issues were hindering the department’s efforts to use contractor workforce data to inform management decisions, including strategic workforce planning, workforce mix and in-sourcing determinations, and budget decisions.[45]

We also reported that DOD components were to use inventories of contracted services to estimate contractor FTEs for workforce planning and budget submissions, but we found in 2013 that the contractor FTE estimates had significant limitations and did not accurately reflect the number of contractor personnel providing services to DOD. At that time, we recommended that DOD include an explanation in annual budget exhibits of the methodology used to project contractor FTE estimates and any limitations of that methodology or the underlying information to which the methodology is applied. DOD has not implemented this recommendation.

DOD continues to face challenges with collecting data on contractor personnel. In October 2020, DOD issued a report to Congress that, among other things, described continued limitations with inventory of contracted services data. The DOD report discussed the department’s recent transition to the government-wide system that other federal agencies use to collect data for inventories of contracted services and explained that this transition is intended to reduce the burden of data collection for defense contractors and improve compliance. However, as we reported in February 2021, DOD’s report did not discuss how it plans to use these data to inform decision-making and workforce planning, key issues our work has identified in the past.[46]

As stated above, the DOD Financial Management Functional Community does not currently have policies and procedures for including contractors in its needs assessment process. Also, DOD does not have a process for gathering information on what specific functions contractor personnel are performing. Officials from the military departments and DFAS did, however, provide information on the general areas that contractor personnel are working in. Also, in OUSD(C)’s Administrative and Personnel Policies to Enhance Readiness and Lethality Final Report, the Civilian Personnel Policies Working Group states that civilian staffing gaps often result in misallocation of resources. As a result of this misallocation of resources, organizations may substitute higher-cost contractors or military personnel to perform work that would be performed more efficiently by civilian federal employees.

DOD Has Strategies to Address Workforce Skills Gaps but Faces Challenges with Succession Planning

Based on our analysis of DOD’s financial management workforce planning information and interviews with officials, we determined that DOD was partially consistent with the key principle of developing strategies that are tailored to address gaps in the human capital approaches for enabling and sustaining critical competencies. Key supporting actions that assist in the implementation of this key principle are (1) developing strategies related to hiring, retention, training, and succession planning and (2) considering how these strategies can be aligned to eliminate gaps and improve the contribution of critical competencies needed for mission success.[47] Since these two supporting actions are closely intertwined, they are discussed concurrently.

Agencies should consider how their strategies can be aligned to eliminate gaps and improve the critical competencies needed for mission success.[48] For example, to help address skills gaps, DOD has made use of recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives for hard-to-fill positions. Succession planning is also important for addressing skills gaps, as the departure of senior staff can leave critical gaps in knowledge and personnel if there are not staff who are prepared to fill those employees’ roles.

DOD Employs Recruitment, Retention, and Training Strategies to Address Workforce Gaps

DOD uses a variety of recruitment and retention strategies, incentives, and training to address skills gaps. The following sections describe how DOD uses these strategies and incentives and how COVID-19 affected DOD’s employee retention.

Recruitment. According to DOD Directive 5118.03, the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer shall provide guidance and oversight with regard to the recruiting, retention, training, and professional development of the DOD financial management workforce. This includes establishing a Functional Community Management Office headed by a senior executive to be responsible for this function. DOD’s Administrative and Personnel Policies to Enhance Readiness and Lethality Final Report – Summary Actions states that the roles of the functional communities include overseeing programs to address gaps through recruitment, training, and development programs targeted at mission needs.

DCPAS developed guidance entitled DOD Hiring Assessment and Selection Guide: Guide for DOD Human Resources Professionals and Hiring Managers. In addition to assisting hiring managers with hiring assessments, the guidance was also designed to aid human resources professionals who assist hiring managers in determining the most effective recruitment strategies to meet the unique mission and workforce needs in DOD. The guidance states that agencies should identify barriers to recruiting a well-qualified and diverse candidate pool as part of DOD’s recruiting efforts.

The guidance provides strategies agencies can employ to enhance recruiting strategies, including the following: (1) establishing relationships with a broad variety of colleges and universities to develop diverse talent pipelines and increase interest in careers with the federal government; (2) reaching out to qualified individuals from appropriate sources to achieve a workforce from all segments of society based solely on fair and open competition and merit that assures that all receive equal opportunity; (3) using technology, including social media, to seek diverse pools of qualified candidates; (4) marketing very competitive federal employee benefits and programs to attract new people to federal employment; and (5) using recruitment flexibilities (e.g., recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives, leave and work schedule incentives, etc.) to attract high-quality candidates.

DOD officials stated that recruiting qualified individuals is a challenge for the department. The military departments and DFAS largely manage their own recruiting, recruiting goals, and position postings, but OUSD(C) supports recruiting efforts across the DOD Financial Management Functional Community.

OUSD(C) officials told us that the COVID-19 pandemic limited the ability to recruit in person at career fairs and conferences and through university campus visits. However, officials at the Army, the Air Force, and DFAS stated that COVID-19 did not present major challenges with recruiting financial management personnel.

The following are examples of some of DOD’s recruitment activities and efforts:

· OUSD(C). OUSD(C) officials told us that they use strategic communication campaigns to promote DOD and post DOD financial management job openings for the military departments on social media. According to DOD officials, the Secretary of Defense has prioritized increasing the diversity of both DOD’s overall workforce and financial management workforce. OUSD(C) officials also told us that the Financial Management Functional Community is exploring outreach to Historically Black Colleges and Universities and minority-serving institutions to enhance the workforce and support the Secretary’s priorities.

According to OUSD(C)’s 2022 year-in-review report, OUSD(C) established a New Hire Program, which is a workforce planning initiative designed to recruit top talent. The New Hire Program leverages existing hiring authorities (e.g., the direct-hire authority) and special employment programs to attract top talent from a wide range of diverse and inclusive sources. After completion of the 2-year program, successful candidates are matched to permanent positions that both optimize Comptroller financial management mission execution and set the new hires up for professional growth and success in the DOD financial management community.

In addition to the New Hire Program, the 2022 year-in-review report states that OUSD(C) expanded its recruitment efforts in several ways, such as (1) focusing on local and national financial management events to identify and recruit prospects proficient in Comptroller skill sets; (2) adapting human capital policies and strategies to maximize telework, remote work, and other workplace flexibilities to both retain talent and remain a competitive option for external candidates; (3) leveraging special employment programs, such as the John S. McCain Strategic Defense Fellows Program, Presidential Management Fellows, and Volunteer Student Intern Program; and (4) maximizing communication strategies to advertise open vacancy announcements across multiple and various platforms, including FM Online and LinkedIn.

· Army. Army Regulation 690-950, Career Program Management, establishes that the Army Civilian Training, Education, and Development System Recruitment Cell is responsible for recruiting interns worldwide and extending job offers to selectees. According to the Army’s Career Program Management regulation, the Army Recruitment Cell will clear special placement programs, review transcripts, verify appointment eligibility, and issue referrals of eligible candidates. To address potential vacancy gaps, officials told us the department established several pathways into the civilian workforce. For example, the Army Civilian Career Management Activity is used to recruit candidates to occupations and hard-to-fill locations—including financial management roles.

· Air Force. According to its 2015 Guide to Civilian Workforce Planning, the Air Force uses a single staffing tool to fill both internal and external position vacancies. It also has an enterprise recruiting team that offers recruiting advice and assistance for civilian hiring needs. According to the guide, the recruiters can help develop recruiting strategies for mission-critical and hard-to-fill positions; provide data-mining services; use social media to solicit qualified candidates; and provide support for career fairs, virtual fairs, and other employment conferences. They can also assist in strategizing for improvement in areas with diversity and disability shortfalls. Air Force officials stated that they have a force renewal program and intern program.

· Navy. According to the Navy’s 2019 through 2030 Civilian Human Capital Strategy, the Navy planned to develop a proactive and streamlined approach to talent acquisition by using smart technologies and social media platforms to access and engage top-tier talent and enhance the candidate experience. According to Navy officials, the department formed a Navy-wide financial management working group to specifically address recruiting and retention.

· DFAS. According to OUSD(C)’s 2022 year-in-review report, DFAS’s Agency Staffing Initiative (ASI) allows the agency to mass hire individuals into commonly filled occupational series and grades at major geographical locations in the agency. Targeted candidates include recent graduates and entry-level talent for job openings, primarily in the 0500 occupational series. The goal of ASI is to increase the hiring of external candidates, reduce hire lag, and maximize the use of budgeted labor dollars for the financial management occupational series. ASI uses an attrition-based model to establish onboard targets. ASI allows the agency to fill positions efficiently by staging recruitment activities before a vacancy exists. In addition to ASI, DFAS uses an internship program to find quality candidates.

DFAS provided a white paper on mass hiring in January 2021, which highlighted recruitment strategies that have worked for the department in the past. Some of these strategies include the use of executive support, marketing and outreach, and dedicated resourcing. Additionally, the white paper highlighted the need to develop a hiring action plan, containing a demand analysis, gap analysis, and action plan development. DFAS officials noted that virtual recruitment had been beneficial to the agency and had reduced the personnel and costs needed to support recruitment activities.

Employee retention. Employee retention is critical for creating a stable workforce and preventing gaps in competencies and personnel. COVID-19 affected the military departments and DFAS in different ways, and the military departments and DFAS took different approaches to retaining financial management personnel.

· Army. Army officials noted that they did not experience any significant civilian retention issues related to COVID-19. However, officials told us that the Army is developing and implementing programs, policies, and systems to reduce attrition.

· Air Force. Air Force officials stated that they did not experience significant civilian retention issues associated with COVID-19. According to Air Force officials, financial management personnel remain at the department because internal candidates fill many of its mission-critical occupations.

· Navy. According to Navy officials, in response to higher-than-expected attrition, steps were being put in place to address this challenge. As part of the Navy Financial Management Workforce Readiness Initiative, the Navy reported that retention concerns consisted of

· the number of financial management manpower spaces at some commands were not consistent with high workloads,

· some financial management personnel were shifting to other financial management organizations where workloads were perceived to be lower, and

· there were limited opportunities within the BSOs for individuals to advance to higher pay grades.

According to the Navy’s Workforce Readiness Initiative May 2021 Workshop Interview Takeaways, identified potential solutions to personnel retention challenges consisted of a baseline BSO manpower space count against expected workloads, advocacy for additional manpower spaces with commanders as required, assurance that hiring pipelines and priorities match future state competencies and current gaps, and optimization of contractor deployments. Officials also stated that the Navy was is in the process of obtaining access to historical data, which will allow it to identify trends and conduct data analysis.

· DFAS. Officials told us that DFAS has a stable workforce and experienced higher retention rates during COVID-19.

Recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives. For some hard-to-fill positions, the military departments, and agencies like DFAS use monetary incentives to recruit and retain certain personnel, including individuals in the federal civilian financial management workforce. Policies and procedures established in DOD Financial Management Regulation 7000.14-R, volume 8, “Civilian Pay Policy,” state that in relation to recruitment incentives, an agency may pay a recruitment incentive to an eligible newly appointed employee, under the conditions specified in the regulations, provided the agency has determined that the employee’s position is likely to be difficult to fill in the absence of an incentive. The total amount of recruitment incentive payments paid to an employee in a service period may not exceed 25 percent of the annual rate of basic pay of the employee at the beginning of the service period multiplied by the number of years (including fractions of a year) in the service period, not to exceed 4 years.

According to the Civilian Pay Policy regulation, in relation to retention incentives, an agency may offer a retention incentive of up to 25 percent of basic pay to a current eligible employee who has unusually high or unique qualifications or when the agency has a special need for the employee’s services, making it essential to retain the employee. Additionally, an agency may pay a relocation incentive to a current eligible employee who must relocate, without a break in service, to accept a position in a different geographic area that is likely to be difficult to fill in the absence of an incentive.

According to OPM’s human resources guidance, recruitment and relocation incentives may be used if an agency has determined that a position is likely to be difficult to fill in the absence of an incentive.[49] In addition, retention bonuses may be used if an agency has found that a special agency need makes it essential to retain an employee and the employee would be likely to leave federal service, or leave for a different position in federal service, without the incentive. These bonuses are limited to maximums that OPM determines.

Per DOD financial management regulations, recruitment, relocation, and retention incentives are compensation flexibilities available to help its agencies recruit and retain civilian employees. Incentives also include student loan repayment assistance.[50] The following are examples of DOD’s activities and efforts as it relates to incentives:

· OUSD(C). OUSD(C) provided documentation showing that it has tracked the number of times recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives have been used from 2017 through 2022. For each year, the tracker identifies which type of incentive was used, the amount awarded, and which military department and functional community used the incentive. The tracker contains total dollar amounts allocated for each incentive by year along with a grand total for all incentives used.

· Army. The Army posted a vacancy for a resource management position in financial administration in June 2024. To incentivize applications for this position, the Army advertised that recruitment, relocation, and student loan incentives may be authorized. The Army also posted a vacancy for an accountant position in May 2024. To incentivize applications for this position, the Army advertised that recruitment and relocation incentives may be authorized.

· Air Force. The Air Force posted a vacancy for a supervisory financial management specialist position in June 2024. To incentivize applications for this position, the Air Force advertised that relocation incentives may be authorized. In addition, the Air Force posted a vacancy for an accountant position in October 2023. To incentivize applications for this position, the Air Force advertised that recruitment and relocation incentives may be authorized.

Also, the Air Force provided documentation in August 2022 showing its retention tracking dashboard from 2017 through 2022. The dashboards provided information on retention rates for the overall Air Force financial management workforce, with individual dashboards presented for each mission-critical occupation. The dashboards show, for each year, what percentage of the workforce was retained and how much money was spent on retention incentives.

· Navy. The Navy posted a vacancy for a financial management analyst position in May 2024. To incentivize applications for this position, the Navy advertised that recruitment and relocation incentives may be authorized. The Navy also posted a vacancy for a deputy director position for financial systems. The advertisement stated that relocation expenses will be paid and that applicants may also qualify for recruitment and student loan incentives.

· DFAS. DFAS posted vacancies for a supervisory financial management specialist position and a supervisory accountant position in June 2024. To incentivize applications for these positions, DFAS advertised that relocation incentives may be authorized for the positions.