EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

USDA Could Strengthen Efforts to Address Workplace Discrimination Complaints

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-105804. For more information, contact Steve Morris at (202) 512-3841 or MorrisS@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑105804, a report to congressional committees

USDA Could Strengthen Efforts to Address Workplace Discrimination Complaints

Why GAO Did This Study

USDA made a commitment to ensuring compliance with EEO requirements and best practices. OASCR leads USDA’s efforts to respond to EEO complaints and coordinate department-wide EEO efforts for nearly 100,000 employees across 29 USDA agencies and offices.

The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 includes a provision for GAO to study, among other things, USDA’s actions to decrease discrimination and civil rights complaints. This report (1) describes the nature of USDA employee discrimination complaints in fiscal years 2015 through 2023, (2) examines USDA’s efforts to address EEO complaints, and (3) examines USDA’s efforts to address discrimination in the workplace.

GAO reviewed USDA’s reports to Congress and EEOC, agency self-assessments, and strategic plans. GAO interviewed USDA and EEOC officials and representatives from 14 USDA employee groups. GAO compared USDA actions with federal and USDA regulations, EEOC management directives, and GAO’s guide on effective training in the federal government.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations for USDA to consistently monitor and report annually on agencies’ ADR programs; update its policy and resume its review of agency civil rights training program plans; and collect anonymous employee perspectives on workplace discrimination. USDA agreed with all three recommendations.

What GAO Found

U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) formal equal employment opportunity (EEO) complaints have decreased from 506 in fiscal year 2015 to 306 in fiscal year 2023. USDA attributes fewer complaints to a range of factors, such as its use of mediation and other conflict resolution efforts. However, a decrease in complaints may not always indicate improvement. For example, fear of retaliation could prevent complaint filing. Of the formal complaints filed, on average, retaliation was the most frequent basis for these complaints. USDA agencies primarily use Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), which uses mediation and facilitation techniques, to address discrimination complaints according to officials from USDA’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights (OASCR).

OASCR has not consistently monitored agencies’ use of ADR, since a 2018 reorganization eliminated its monitoring staff and realigned responsibilities to the agencies, according to OASCR officials. USDA has more than doubled its EEO staff since fiscal year 2022 according to a USDA 2023 report but has not resumed monitoring. By resuming monitoring, OASCR could better ensure these programs are meeting departmental standards such as using ADR at the first sign of conflict.

USDA’s efforts to address discrimination in the workplace include mandatory civil rights training. USDA agencies also develop civil rights training plans, which departmental regulation requires OASCR to review. Prior GAO work found an agency’s evaluation of its training program is important in demonstrating how its efforts are improving agency performance. However, OASCR does not review training plans, according to OASCR officials, who said they are updating a policy to provide criteria for these reviews. By updating its policy and resuming the reviews, OASCR could better assist agencies with their efforts to increase awareness of discrimination and employee rights.

OASCR officials were not aware of USDA having a method for consistently collecting anonymous employee perspectives on discrimination—an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) promising practice. USDA uses an Office of Personnel Management survey. However, the survey’s questions are not specific to USDA’s or any other agency’s workplace environment. By developing a department-wide tool to collect anonymous employee perspectives, USDA management could better understand where to target its efforts to help create a workplace free of discrimination for all employees.

Abbreviations

ADR alternative dispute resolution

CDIO Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer

DEIA diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility

EEO equal employment opportunity

EEOC Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

FEVS Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey

FY fiscal year

No FEAR Act Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act

OASCR Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 21, 2025

The Honorable John Boozman

Chairman

The Honorable Amy Klobuchar

Ranking Member

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

United States Senate

The Honorable Glenn “GT” Thompson

Chairman

The Honorable Angie Craig

Ranking Member

Committee on Agriculture

House of Representatives

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), one of the federal government’s largest employers, has expressed a commitment to ensuring compliance with equal employment opportunity (EEO) requirements and best practices. Federal EEO laws make it illegal for employers, including federal agencies, to discriminate against a job applicant or employee on the basis of certain characteristics, such as race, sex, and disability.[1] These laws also protect applicants and current and former employees from retaliation for filing a discrimination complaint, among other protected activities. USDA’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights (OASCR) leads the department’s efforts to respond to EEO complaints and coordinate department-wide civil rights and EEO efforts for nearly 100,000 employees across 29 USDA agencies and offices.

The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (2018 Farm Bill) includes a provision for us to study USDA’s actions to decrease discrimination and civil rights complaints, its efforts to identify actions or activities that may adversely affect employees, and any negative implications of a 2018 reorganization of USDA’s civil rights functions.[2] This report (1) describes the nature of discrimination complaints by USDA employees from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2023, (2) examines USDA’s efforts to address EEO complaints, and (3) examines USDA’s other efforts to address discrimination in the workplace. Appendix I summarizes changes that USDA made in reorganizing its civil rights functions in 2018 and provides information on the effect of those changes through fiscal year 2024.

To address all three objectives, we reviewed USDA reports and other documentation. Specifically, we reviewed USDA’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Strategic Plan for fiscal years 2022–2026, OASCR’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2025–2029, and USDA’s policies on processing EEO complaints, promoting civil rights, and addressing harassment. We also reviewed Civil Rights Impact Analyses and USDA management directives on training and use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR). In addition, we interviewed agency officials and staff. Specifically, we interviewed:

· officials from USDA’s OASCR, Office of Human Resource Management, and Office of the Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer;

· officials from six USDA agencies or mission areas—four with the highest total number of EEO complaints and two that are among the USDA agencies or mission areas with the lowest per capita number of complaints;[3]

· representatives of 14 USDA employee resource groups to obtain their perspectives about the workplace environment;[4] and

· officials from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

To describe the nature of USDA’s EEO complaints by employees and to examine USDA’s efforts to address complaints, we also reviewed a range of USDA reports for fiscal years 2015 through 2023. These reports were: USDA’s Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act (No FEAR Act) reports; the employee civil rights sections of Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (Farm Bill) reports and EEOC Form 462 reports on EEO data.[5]

To examine USDA’s other efforts to address discrimination in the workplace, we also reviewed the annual self-assessment reports that USDA agencies submitted to EEOC (MD-715 reports) for fiscal years 2015 through 2023, EEOC’s responses to these self-assessments, and other related documents.

To understand the effect of the reorganization, we analyzed documentation from OASCR and interviewed OASCR officials about the status of the 2018 reorganization, any additional changes since 2018, and effects of the reorganization on staffing and operations.

We compared the actions USDA and its agencies and offices took to address EEO complaints and discrimination in the workplace with federal regulations, USDA departmental policies, EEOC management directives and reports, and GAO guidance on effective training in the federal government.[6]

We conducted this audit from February 2022 through January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Within USDA, OASCR provides leadership and direction for the department’s efforts to ensure compliance with applicable civil rights-related laws, regulations, and policies. OASCR also leads the department’s efforts to promote actions aimed at preventing discrimination, reducing complaints, and using best practices in the administration of civil rights programs involving diversity and compliance. OASCR coordinates with other USDA offices, such as the Office of Human Resources Management. OASCR also coordinates with and provides oversight of the civil rights activities of USDA’s eight mission areas and individual USDA agencies.

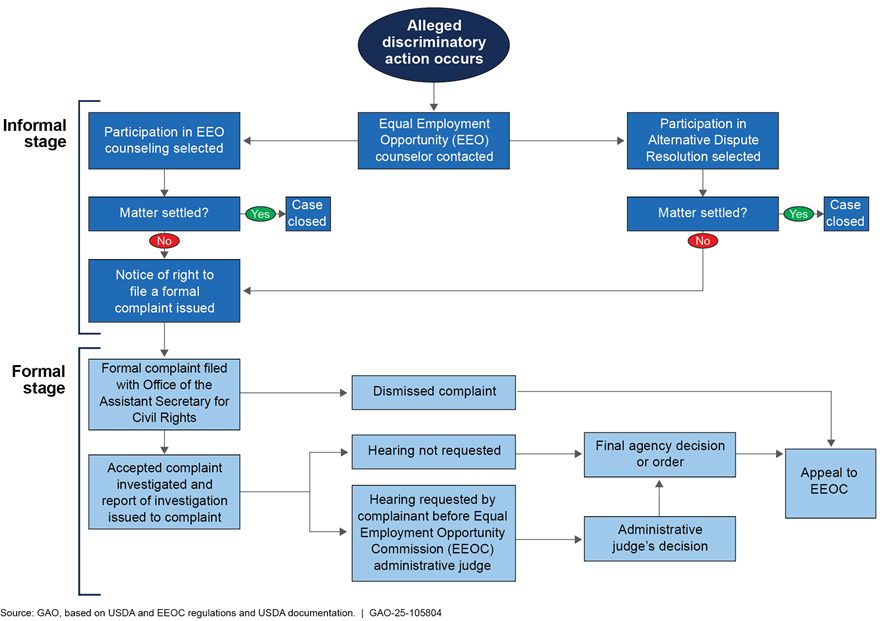

When USDA employees allege discrimination, they must first attempt to resolve the complaint informally (e.g., through mediation) within their agency. If the complaint is not resolved to their satisfaction through the informal process, the employee can file a formal complaint with OASCR.[7] Figure 1 summarizes the steps in the complaint process for employees who allege they have been discriminated against on the basis of race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, childbirth, or related conditions, sexual orientation, and gender identity), national origin, age (40 or over), disability, genetic information, or retaliation for engaging in a protected activity, such as filing an EEO complaint.

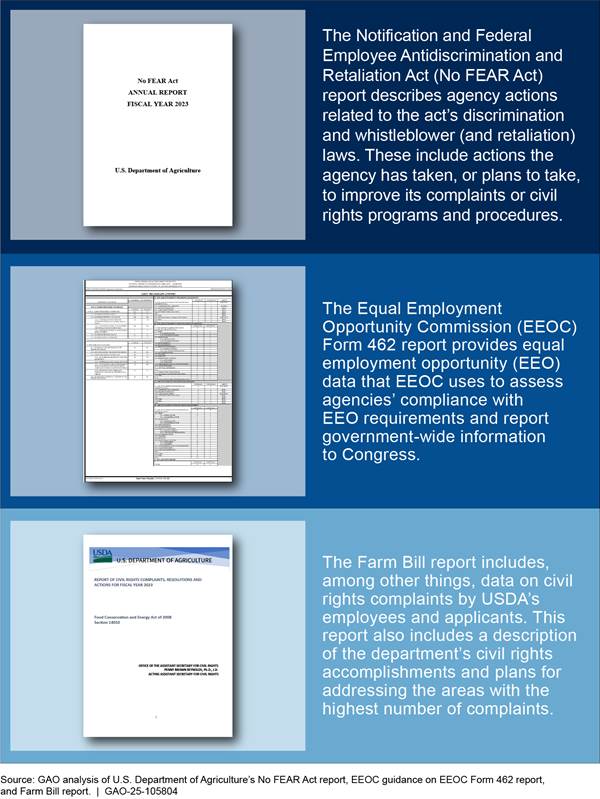

OASCR collects a range of complaint data from 29 USDA agencies and offices for required external reporting to Congress and EEOC, and for internal decision-making. USDA submits two reports to Congress annually, both of which are publicly available: the No FEAR Act reports and the Farm Bill reports. In addition, OASCR annually certifies a nonpublic EEOC Form 462 report with EEOC. These three reports provide information on the number and nature of employee EEO complaints, but each report has a different purpose and format. (See fig. 2.) As previously stated, the MD-715 reports are annual self-assessment reports that USDA agencies submit to EEOC; USDA management uses these reports for internal oversight.

Figure 2: Purposes of the Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act (No FEAR Act); Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) Form 462; and Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (Farm Bill) Reports

EEO Complaints by USDA Employees Have Generally Declined since 2015, and Retaliation Has Been the Most Frequent Basis of Formal Complaints

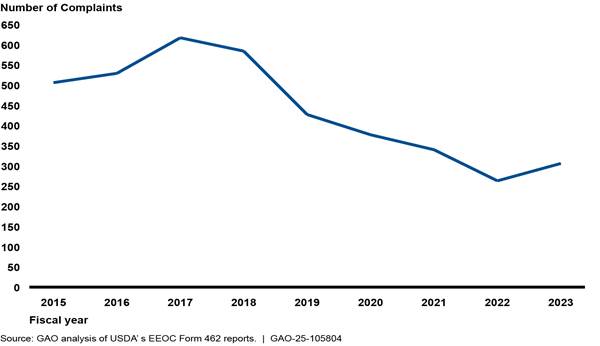

The number of formal EEO complaints filed by USDA employees generally decreased from 2015 through 2023, with retaliation, on average, the most frequent basis of complaints filed.[8] Overall, the total annual number of complaints decreased by almost 40 percent, from 506 in fiscal year 2015 to 306 in fiscal year 2023, according to data from USDA’s EEOC Form 462 reports. (See fig. 3.)

Figure 3: U.S. Department of Agriculture Equal Employment Opportunity Formal Complaints, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

OASCR officials provided perspectives on what may have contributed to the decrease in formal complaints since 2015. Officials said that a range of factors contributes to changes in complaint trends, but a key factor was the department’s use of mediation and other conflict resolution efforts, which we discuss in this report. These officials also noted that an increase in telework, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, generally contributed to a reduction in workforce conflict for some of the years.[9] In addition, several agency officials attributed a lower number of formal complaints within their agencies to managers’ proactive approach to communicating with employees about their concerns and addressing conflicts early.

In its recent No FEAR Act reports, USDA is neutral in its discussion about the meaning of trends in formal EEO complaints. Although USDA’s decline in formal complaints may be viewed as a positive trend for its EEO program, analyzing trends in complaint data has limitations. An increase may not always indicate a worsening workplace or environment, and a decrease in the number of complaints may not always indicate an improved program. For example, an employee’s concern about potential retaliation could prevent them from filing a complaint. In such cases, the absence of a complaint would not necessarily indicate the absence of discrimination or workplace conflict. We have previously reported that members of marginalized groups can be afraid to raise discrimination issues because of possible retaliation.[10]

|

Retaliation: Retaliation can include such actions as a poor performance appraisal, denial of promotion, assignment to less desirable or less important duties, or discharge. A complaint may include information about the reason (e.g., participating in the complaint process, complaining about discrimination, or requesting a reasonable accommodation) for which retaliation is alleged. Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑105804 |

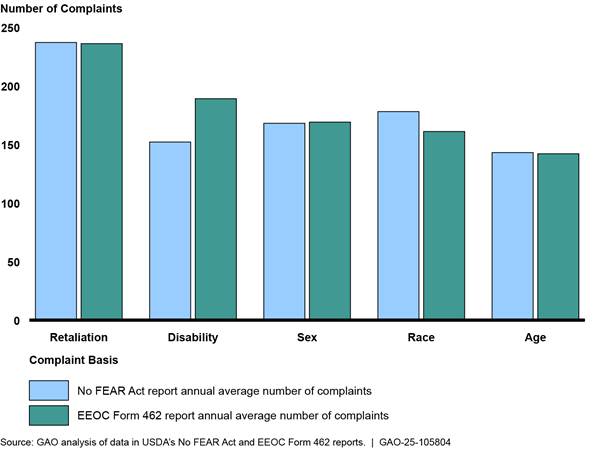

During this time frame, on average, retaliation was the most frequent basis of formal EEO complaints at USDA. This trend was consistent across the federal government.[11] Disability, sex, race, and age were the other top five bases at USDA, and their ranking varied by year and type of report (i.e., No FEAR Act and EEOC Form 462).[12] In fiscal years 2015 through 2023, USDA averaged 236 complaints per year on the basis of retaliation, compared with 189 on the basis of disability, 169 on the basis of sex, 161 on the basis of race, and 142 on the basis of age, according to data from USDA’s EEOC Form 462 reports.[13] Figure 4 shows the average annual number of complaints by basis, according to data from USDA’s No FEAR Act and EEOC Form 462 reports.

Figure 4: Average Annual Number of Equal Employment Opportunity Formal Complaints by Complaint Basis at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, According to Two Types of Reports, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Note: This figure presents data from two types of reports—USDA’s Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act (No FEAR Act) reports and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) Form 462 reports—because certain data differ in each type of report. The reports count complaints based on disability and race differently because of a database error in some No FEAR Act reports that we identified in our prior report, Equal Employment Opportunity: Additional Actions Would Improve USDA’s Collection and Reporting of Key Data, GAO‑24‑106791 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 2, 2023). Complaints can be filed alleging multiple bases. The sum of the bases may not equal total complaints filed.

Surveys and other information, such as information from employee resource groups, can complement complaint data from USDA’s reports. These include independent government surveys, which can provide some insight into USDA employees’ views about retaliation in the workplace. For example:

· 2023 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS). Of the USDA employees who responded to a question about retaliation, 15 percent had negative associations with disclosing suspected violation of any law, rule, or regulation without fear of retaliation.

· U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board’s 2021 Merit Principles Survey. Of the USDA employees who responded to the survey question, about 6 percent had or were aware of an experience within the prior 2 years where an agency official in their work unit took or threatened to take retaliatory personnel action against a USDA employee for filing a grievance of an appeal.

In addition, representatives from six of the 14 USDA employee resource groups we interviewed said that they believed fear of retaliation discourages employees from filing formal complaints. For example, one representative expressed concern that filing a complaint could hurt their career at USDA. Another representative commented that employees were hesitant to file complaints for fear that they would need to continue to report to the person they filed a complaint against.

USDA Relies on Alternative Dispute Resolution to Address EEO Complaints but Does Not Monitor Agencies’ Use of This Method

USDA agencies primarily use ADR to address discrimination complaints, according to OASCR officials, but OASCR does not conduct the required monitoring of the agencies’ use of this method. As required by EEOC, USDA agencies use ADR in both the informal and formal stages of the complaint process to address employee complaints, according to OASCR officials. The agencies use this method with the goal of reducing the number of formal complaints that employees file, according to these officials. OASCR officials said that USDA agencies’ use of ADR contributed to the decrease in formal employee complaints from fiscal year 2017 through 2023 and based this assertion on ADR participation data from EEOC Form 462 reports.[14] In our review of EEOC Form 462 reports, we also found that the percentage of USDA employees with informal complaints who participated in ADR increased between FY 2017 to FY 2023, but the total number of ADR settlements decreased slightly from 62 in FY 2017 to 47 in FY 2023.

|

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR): Since 2000, EEOC has required all federal agencies to establish or make available an ADR program during the informal and formal complaint stages of the EEO complaint process. ADR generally refers to processes and approaches to resolve disputes in a manner that avoids the associated costs of delay and unpredictability of more traditional adversarial and adjudicatory processes such as litigation, hearings, and appeals, according to an EEOC fact sheet on ADR. ADR techniques include mediation, facilitation, and settlement conferences. Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑105804 |

Federal regulations and guidance direct federal agencies to review and monitor their ADR programs to specifically:

1. evaluate its ADR program to help determine whether the program has achieved its goals and provide feedback to agency program administrators on how it could become more efficient and achieve better results;[15]

2. identify EEO deficiencies in the workplace and self-assess its EEO program’s compliance, including the ADR program;[16] and

3. report information to EEOC about pre-complaint counseling, including ADR program activities.[17]

In addition, a federal regulation authorizes USDA’s Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights to monitor agencies’ ADR programs and report at least annually to the Secretary on the department’s ADR activities.[18]

To address these ADR program and other requirements, USDA agencies, offices, and mission areas submit an MD-715 self-assessment and EEOC Form 462 report containing complaint and ADR usage data to EEOC annually. The agencies also provide the ADR usage data to OASCR, which consolidates these data for inclusion in the department’s EEOC Form 462 report. OASCR then submits an MD-715 self-assessment and EEOC Form 462 for all of USDA to EEOC each year. In the MD-715 assessment that OASCR submitted to EEOC for fiscal year 2023, USDA reported that its agencies were offering ADR to employees and evaluating their ADR programs, as directed by EEOC.[19] EEOC’s 2023 feedback letter to USDA did not list evaluation of ADR programs as an area of concern.[20]

As previously mentioned, OASCR collects ADR information from MD-715 reports and provides aggregate information to EEOC from these reports. OASCR officials also said that they review data on whether the department has met EEOC’s 50 percent threshold for the number of EEO informal complaints for which ADR was offered. However, OASCR does not consistently monitor USDA agencies’ use of ADR. Under federal regulation, OASCR has authority for monitoring agency ADR programs and reporting at least annually to the Secretary on the Department’s ADR activities.[21] Monitoring could help determine whether the agencies’ ADR programs are meeting USDA’s departmental standards, which include providing training and educational services designed to promote effective conflict management. The standards also state that the goal of ADR at USDA is to achieve effective and mutually satisfactory conflict resolutions to foster a culture of respect and trust.[22]

We analyzed the responses in 12 MD-715 reports representing eight USDA agencies, two USDA mission areas (which oversee multiple agencies), and two USDA offices for fiscal year 2023. We found that all reported evaluating the effectiveness of their own ADR programs, as shown in table 1.

Table 1: U.S. Department of Agriculture Management Directive 715 Reports on Evaluating Alternative Dispute Resolution Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

|

Agencies, mission areas, and offices reported evaluating effectiveness of ADR program |

12 |

|

Agencies, mission areas, and offices provided information about the evaluation results |

6 |

|

Agencies, mission areas, and offices did not provide information about the evaluation results |

6 |

Source: GAO analysis of 12 USDA MD-715 reports. | GAO‑25‑105804

Six agencies, mission areas, and offices provided information about the results of their evaluations. For example, Farm Production and Conservation, a mission area representing three agencies, reported that ADR was offered to 96 percent of its employees with complaints during the informal stage. Of those employees offered ADR, about half elected to participate. Of the employees who participated, most (60 percent) resolved their issue through ADR. However, as shown in table 1, six of the 12 agencies, mission areas, and offices did not include information about their ADR evaluations. As a result, these reports do not clearly convey whether the ADR programs are meeting USDA’s departmental standards and goal for ADR. EEOC officials agreed that having specific information about evaluations of ADR programs could help USDA determine whether its agency, mission area, and office-level ADR programs are meeting its standards.

OASCR has not consistently monitored USDA agencies’ ADR programs since 2018, when a reorganization of civil rights functions at USDA eliminated the ADR division staff that led the monitoring and realigned responsibilities to the agencies and mission areas, according to OASCR officials (see app. I for more information about the reorganization). OASCR officials said that they do not believe that OASCR is directly responsible for the oversight of the agencies’ use of ADR. However, they said, the office internally determined that USDA should reestablish the division that provided oversight of ADR activities and included this as a goal in OASCR’s 2025–2029 Strategic Plan. They estimated needing eight full-time-equivalent employees.

USDA documents we reviewed indicate some resources may be available to OASCR for this effort. For example, in its 2023 Response to the USDA Equity Commission Interim Report, USDA stated its commitment to fully funding and staffing OASCR and agency-level civil rights offices. In addition, USDA has more than doubled its EEO staff since fiscal year 2022, according to its 2023 No FEAR Act report.[23] In addition, OASCR officials told us that they hired an ADR Program Manager in October 2024. However, at that time, OASCR was not consistently monitoring agencies’ ADR programs. In its December 2024 technical comments on our draft report, OASCR officials stated that they developed but had not yet implemented a process to evaluate the ADR program through surveys of participants. This process, according to officials, is intended to assist OASCR in enhancing its mechanisms for regular monitoring. By consistently monitoring USDA agencies’ ADR programs, OASCR could better ensure these programs are meeting departmental standards such as making ADR available at the first sign of a conflict to promote effective conflict management approaches.

USDA Has Taken Steps to Address Discrimination but Does Not Assess Its Training or Collect Anonymous Employee Views

USDA has taken steps to enhance its efforts to address discrimination in the workplace. However, OASCR has not reviewed USDA agencies’ civil rights training plans to ensure they met USDA’s standards. USDA also does not have a method to consistently collect anonymous employee perspectives on and experiences with discrimination across the department.

USDA Has Undertaken Several Efforts to Address Discrimination, but OASCR Does Not Assess Agency-Specific Training Plans

USDA has undertaken a range of recent and ongoing efforts across the department to address discrimination in the workplace. Recent department-wide efforts include establishing offices, policies, and guidance (see table 2 for examples).

Table 2: Examples of Recent U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Efforts to Address Discrimination in the Workplace

|

Published the first departmental Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Strategic Plan (Fiscal Years 2022—2026). |

|

Established its first Office of the Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer to lead USDA’s DEIA Strategic Plan and advance DEIA efforts department wide. |

|

Updated its anti-harassment policy statement in 2021 and again in 2024 to address harassing behavior early to avoid or limit potential harm to any employee before it rises to the level of unlawful harassment. |

|

Established an Anti-Harassment Program through Departmental Regulation 4200-003. |

|

Issued USDA equal employment opportunity policy statements. |

|

Formed an Equity Commission, which in February 2024 issued a final report with recommendations on advancing equity at USDA. |

|

Developed and implemented its first Inclusive Hiring Practices Toolkit, guidance to help hiring managers and others mitigate bias in the hiring process. |

|

Created its first DEIA Data Analytics Dashboard to provide USDA employees access to current USDA data on hiring, separations, promotions, award distribution, and workforce breakdowns. |

|

Developed and offered an optional department-wide learning series for employees on a variety of DEIA-related topics. |

Source: GAO analysis of USDA documents and program information provided by USDA. | GAO‑25‑105804

Mandatory civil rights training is central to USDA’s ongoing efforts to address discrimination, according to OASCR officials. These officials said training is a key tool for the department to raise awareness about and address discrimination by helping employees understand their rights and understand what types of behavior are inappropriate in the workplace. They also said that, similarly to other federal agencies, USDA employees take training on the No FEAR Act and USDA Whistleblower Rights and Remedies. In addition, each year, OASCR provides training on a specific topic related to employee rights or issues of discrimination.

OASCR officials said they decide what training to provide partly based on recent complaint data. For example, OASCR officials said that in fiscal year 2020, they developed department-wide training on reasonable accommodation and personal assistance services because complaint data showed that disability was among the top four bases for employee complaints in fiscal years 2018 and 2019. As of August 2024, OASCR had also developed content for a new course on reasonable accommodations and personal assistance services.[24] OASCR officials also said that in 2022, it implemented an unconscious bias training program and in 2023, it offered USDA’s first anti-harassment training program.[25]

In addition to the department-wide civil rights training, USDA agencies develop agency-specific civil rights training plans. However, OASCAR is not reviewing these training plans as required, according to OASCR officials. USDA departmental regulation 4120-001 (June 2016) directs OASCR to provide notice to agencies of the standards for preparing proposed civil rights training plans. This departmental regulation also directs OASCR to approve or disprove those training plans. In addition, our prior work has found that an agency’s evaluation of its training program is important in demonstrating how its efforts are improving agency performance.[26] OASCR is not reviewing the plans because its primary focus since the 2018 reorganization has been on processing EEO complaints, according to OASCR officials.

OASCR officials said they plan to assess the agencies’ civil rights training plans, as directed by departmental policy. The officials also said they are currently making significant revisions to a departmental policy that would provide criteria for OASCR’s review, and subsequent approval or disapproval, of agency-specific civil rights training plans. However, as of October 2024, they had not done so. By developing its policy to guide its reviews of agency civil rights training programs, and resuming those reviews as required by departmental policy, OASCR could be better prepared to assist agencies with their efforts to increase awareness of discrimination and employee rights through training.

USDA Does Not Consistently Collect Anonymous Employee Views

While OASCR uses the results of employee surveys to help identify training or management needs, OASCR officials were not aware of USDA having a method for consistently collecting anonymous employee perspectives on discrimination. OASCR officials said USDA uses the following methods to collect information:

· OPM’s Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS), for information on USDA employees’ viewpoints to identify potential areas of training;

· USDA agencies’ MD 715 self-assessments, to identify additional analyses that agencies may need to conduct for oversight;

· Employee climate or satisfaction surveys from individual USDA agencies; and

· Employee feedback during focus group meetings, roundtables, and listening sessions held by USDA leadership.

USDA’s Office of the Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer reviews FEVS data for information about whether employees believe that they are treated fairly and have opportunities to advance, including promotions and awards, according to the Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer (CDIO). In addition, the CDIO has met with several employee resource group representatives to hear their concerns and identify ways to address them.

Although OASCR and the CDIO collect some employee viewpoints, FEVS survey questions are written for the federal government and are not specific to USDA’s or any other agency’s workplace environment. Furthermore, agencies’ MD-715 self-assessments provide agency management’s perspectives on their efforts to address workplace issues and does not require employee perspectives on their workplace experiences. Employee feedback USDA receives during focus group meetings, roundtables, and listening sessions does not provide opportunities for anonymity. As discussed earlier, almost half of the employee groups we interviewed expressed concerns about retaliation.

Various USDA and federal reports encourage the collection of information from employees to inform agency efforts to address discrimination. USDA’s 2022 Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Strategic Plan suggests using surveys to help monitor employee experiences to foster a workplace that is physically, mentally, and emotionally safe. EEOC’s 2017 “Promising Practices for Preventing Harassment” encourages management to consider conducting anonymous employee surveys on a regular basis to assess whether harassment occurred or is perceived to be tolerated. We have also previously found that surveying the workforce can be an important tool to identify employment issues.[27] We reported that one agency plans to assure employees of the confidentiality of the survey to help improve accuracy of the survey results. Confidential, anonymous surveys can help agencies identify actions or activities that may be adversely affecting their employees.

When we discussed the possibility of an agency-wide survey with OASCR officials, they said they have made efforts to collect employee feedback and OASCR was open to considering an agency-wide survey. Because USDA comprises 29 agencies and offices across eight different mission areas, an agency-wide survey would involve coordination with all relevant USDA component agencies, offices, and mission areas. By developing a tool to consistently collect, on a department-wide level, anonymous information on employees’ perspectives on and experiences with discrimination, USDA management would be better able to understand where and how to target its efforts to create a workplace free of discrimination for all employees.

Conclusions

USDA, one of the federal government’s largest employers, has expressed a commitment to not only ensuring compliance with EEO requirements and best practices; but also promoting diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility. USDA primarily uses ADR at the agency level to address discrimination complaints and has taken other steps at the departmental and agency levels to address employee complaints and, more broadly, discrimination in the workplace. Recent actions include the appointment of the department’s first Chief Diversity Inclusion Officer and development of a department-wide DEIA strategic plan.

We identified additional actions USDA could take to strengthen its efforts to address discrimination in the workplace. Specifically, by ensuring OASCR monitors agencies’ ADR programs and reviews agencies’ civil rights training plans, USDA will better position itself to ensure its agencies are meeting departmental standards and goals to mediate conflict and increase awareness of employee rights. Additionally, by consistently obtaining, on a department-wide level, anonymous employee views on workplace discrimination, USDA management would better understand where and how to target its efforts to address discrimination in the workplace.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to USDA:

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure OASCR consistently monitors and reports annually to the Secretary on agency ADR programs, as authorized by federal regulation. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure OASCR updates its policy, as planned, and resumes its reviews of agency civil rights training program plans, as directed by departmental policy. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure OASCR develops and administers a department-wide tool for obtaining anonymous information from employees about their experiences with workplace discrimination. This effort should be in coordination with all relevant USDA agencies, offices, and mission areas. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to USDA and EEOC for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix II, USDA agreed with all three recommendations, stating that it welcomes GAO’s recommendations for improving and strengthening efforts to address workplace discrimination complaints. USDA provided a description of actions the department plans to take in response to our recommendations, and we believe these actions, once implemented, will address the issues we identified. USDA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate. EEOC also reviewed the draft and provided one technical comment, which we incorporated.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Chair of EEOC, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or MorrisS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff members who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Steve D. Morris

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

Appendix I: Status and Effects of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2018 Reorganization of Civil Rights

In 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reorganized civil rights functions across the department. The reorganization included a range of changes that, according to USDA at the time, would improve customer service, better align functions within the department, and ensure improved consistency and resource management, among other things.[28] USDA consolidated the civil rights offices functions in each of the department’s 29 agencies and offices under each of its eight mission areas.[29] USDA also consolidated civil rights functions within its Office for the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights (OASCR).

This appendix summarizes the changes and describes the effects, since 2018 and through fiscal year 2024, as identified by USDA.[30]

Key Changes Made during the 2018 Reorganization

USDA reorganized OASCR to focus its resources on processing discrimination complaints (and save resources spent on duplicative functions) in response to Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) sanctions, according to a USDA document.[31] Key changes within OASCR included the elimination or reclassification of leadership positions and division offices. As a result, OASCR ended all activities related to cultural transformation, and those related to monitoring agency-specific and mission-area civil rights training program plans and of alternative dispute resolution programs. Table 3 provides a list of key changes and their status as of September 2024.

Table 3: Key Changes Made during the 2018 Reorganization of Civil Rights Functions Performed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights

|

|

Change |

Status as of September 2024 |

|

|

|

OASCR Policy Division eliminated |

Complete |

|

|

|

OASCR Training and Cultural Transformation Division eliminated |

Complete |

|

|

|

Early Resolution and Conciliation Division eliminated |

Complete |

|

|

|

SES Director for the Office of Adjudication reclassified to Executive Director for Civil Rights Enforcement |

Complete |

|

|

|

SES Director for the Office of Compliance, Policy, Training, and Cultural Transformation reclassified to Executive Director for Civil Rights Operations |

Complete |

|

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by USDA. | GAO‑25‑105804

OASCR moved many of the responsibilities that the three eliminated divisions performed to four divisions, two of which were newly created:

· Center for Civil Rights Operations (created in 2018)

· Center for Civil Rights Enforcement (created in 2018)

· Conflict Complaints Division

· Program Planning and Accountability Division

These divisions were still in place as of October 2024. Below, we describe in more detail the changes and their effects.

Elimination of the Policy Division

According to a 2018 Federal Register publication, OASCR’s Policy Division was eliminated because it was no longer necessary in an era of decreased regulations. The Policy Division’s responsibilities included:

· agency compliance reviews and reporting to oversight entities;

· evaluations of agency progress in meeting equal employment opportunity (EEO) and affirmative employment objectives; and

· evaluation to identify systemic discrimination and agency civil rights performance, and management of the MD-715 model EEO program.

The Policy Division’s functions were distributed to OASCR’s Center for Civil Rights Operation’s Compliance Division.

Effect. The Center for Civil Rights Operation’s Compliance Division assumed responsibility for preparing and providing mandatory reports to oversight entities. As we reported in November 2023, OASCR officials attributed inconsistencies and other issues related to several of USDA’s Farm Bill reports to its prioritization of processing complaints, and the loss of the staff it had for developing various reports.[32]

Elimination of the Training and Cultural Transformation Division

USDA eliminated the Training and Cultural Transformation division because it chose to use training resources in other areas of the department, according to a 2018 Secretary’s Memo. This division was responsible for activities such as

· developing the OASCR cultural transformation annual plan,

· conducting studies for program and policy changes,[33] and

· delivering USDA-wide civil rights training.

Some of the Training and Cultural Transformation Division’s functions, such as serving as the liaison for external entities, were moved to other OASCR divisions.

Effect. OASCR officials said that as of 2018, OASCR had ended all activities related to cultural transformation. In addition, OASCR-led activities and oversight of the agency-specific training and mission-area training also ended. OASCR officials noted that the office continued to require that agencies submit training plans but did not review them. In 2023, USDA hired its first permanent Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer to lead its Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) strategic plan, which includes the goal of building a culture of trust, belonging, transparency, accountability, and employee empathy. This position reports directly to the Office of the Secretary.

Elimination of the Early Resolution and Conciliation Division

USDA moved the responsibilities of the Early Resolution and Conciliation Division from OASCR to mission-area management. According to OASCR officials, OASCR staff coordinated with mission area staff to resolve employment or program complaints of discrimination using alternative dispute resolution (ADR) on an as needed basis. These officials said that was not a new structure, as ADR or Conflict Resolution Specialists in the mission areas also had responsibility for using ADR techniques to resolve complaints.

Effect. OASCR’s elimination of the Early Resolution and Conciliation Division also ended the office’s annual reviews of USDA agencies’ use of ADR and the coordination of ADR training opportunities for USDA employees and managers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) considers agencies’ establishment of (or making available) an ADR program to be a federal requirement.[34]

In 2023, USDA officials told us that OASCR leadership had assessed the structure of and operations within the office. Subsequently, in October 2024, OASCR hired an ADR Program Manager, to provide oversight and reestablish OASCR’s ADR program, according to OASCR officials. This position is responsible for the establishment of reporting requirements for USDA agencies related to conflict prevention and resolution programs.

GAO Contact

Steve D. Morris, (202) 512-3841 or morriss@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

Major contributors to this report were Tahra Edwards Nichols (Assistant Director), Allen Chan (Analyst in Charge), Betsy Morris, and Brianna Taylor. Other key contributors were Adrian Apodaca, Carl Barden, Kevin Bray, Mikaela Chandler, Tara Congdon, Shirley Hwang, Melissa Lefkowitz, Katherine Lenane, Serena Lo, Michael Murray, Keith O’Brien, Jerome Sandau, and Kayla Smith.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission enforces federal laws that make it unlawful to discriminate against a job applicant or employee based on race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, childbirth, or related conditions, sexual orientation, and gender identity), national origin, age (40 or older), disability, or genetic information; or to retaliate against a job applicant or employee for engaging in protected activity.

[2]Pub. L. No. 115-334, § 12403(b), 132 Stat. 4490, 4974. We previously addressed other aspects of this provision from the 2018 Farm Bill through an oral briefing to congressional staff from the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee and House Agriculture Committee on April 11, 2022, and in GAO, Equal Employment Opportunity: Additional Actions Would Improve USDA’s Collection and Reporting of Key Data, GAO‑24‑106791 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 2, 2023). This product addresses the remaining aspects of the provision.

[3]The U.S. Forest Service, Farm Production and Conservation, Food Safety and Inspection Service, and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service were among the USDA agencies or mission areas with the largest total number of EEO complaints. Agriculture Research Service and National Agricultural Statistics Service were among the agencies or mission areas with the lowest number of per capita EEO complaints.

[4]We selected 24 USDA employee resource groups that represented employees with characteristics that federal EEO laws indicate are illegal to discriminate against, such as disability, race, religion, and sex. Among these 24 groups, 14 agreed to meet with us.

[5]Employee complaints include complaints from current employees, past employees, and applicants for employment. For the purposes of this report, we refer to these groups collectively as “employees.”

[6]GAO, Human Capital: A Guide for Assessing Strategic Training and Development Efforts in the Federal Government, GAO‑04‑546G (Washington, D.C.: March 2004).

[7]OASCR’s Conflict Complaints Division manages and administers the EEO complaint process.

[8]The No FEAR Act and Farm Bill reports use the term “retaliation,” while the EEOC Form 462 report uses the term “reprisal.” For the purposes of this report, we use the term “retaliation.”

[9]According to USDA’s fiscal year (FY) 2023 No FEAR Act report, during FY 2023, USDA issued return to workplace guidance for all Senior Executives and Supervisory personnel.

[10]GAO, Federal Workforce: Leading Practices Related to Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility, GAO‑24‑106684 (Washington, D.C.: May 23, 2024).

[11]According to data from EEOC’s Report on the Federal Workforce for fiscal years 2015 to 2023, on average, retaliation has also been the most frequent basis for formal EEO complaints by federal government employees.

[12]In November 2023, we reported that USDA’s No FEAR Act reports for 2015 through 2022 differed from its EEOC Form 462 report for 2015 through 2022 in complaint figures for race and disability because of a database error in the No FEAR Act report for race and because the two reports count complaints based on disability differently. See GAO‑24‑106791.

[13]We used complaint figures from the EEOC Form 462 report instead of USDA’s No FEAR Act report because, as we reported in November 2023, the No FEAR Act report has a database error for race complaint figures. See GAO‑24‑106791.

[14]Employee complaints increased from 2015 through 2017.

[15]EEOC’s Management Directive 110 directs federal agencies to establish an evaluation component as part of an effective ADR program. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Equal Employment Opportunity Management Directive for 29 C.F.R. Part 1614, EEO-MD-110 (revised Aug. 5, 2015).

[16]According to EEOC, its Management Directive-715 (MD-715) provides policy, guidance, and standards to establish and maintain model EEO programs government-wide. MD-715 requires, among other things, that agencies identify EEO deficiencies in the workplace, develop and execute plans to eliminate those deficiencies, and report them annually to EEOC.

[17]29 C.F.R. § 1614.602(a).

[18]7 C.F.R § 2.25(a)(21)(vi).

[19]According to EEOC, MD-715 provides policy, guidance, and standards to establish and maintain model EEO programs government-wide. MD-715 requires, among other things, that agencies identify EEO deficiencies in the workplace, develop and execute plans to eliminate those deficiencies, and report them annually to EEOC.

[20]EEOC’s feedback letter summarized its findings on USDA’s compliance with EEOC regulations and directives, and key aspects of USDA’s EEO program.

[21]7 C.F.R § 2.25(a)(21)(vi). The Secretary delegated this authority to the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights.

[22]USDA departmental regulation 4710-001 (April 2006) describes USDA’s policy on the use of ADR and states that OASCR is to issue policies, regulations, and guidance on the use of ADR and the evaluation of programs.

[23]Specifically, USDA increased the number of EEO staff by 114 percent in FY2023.

[24]Federal agencies are required by regulation to provide personal assistance services, unless doing so would impose an undue hardship on the agency. 29 C.F.R. § 1614.203(d)(5). These are services that help individuals who, because of targeted disabilities, require assistance to perform basic activities of daily living, like eating and using the restroom. 29 C.F.R. § 1614.203(a)(5). These services differ from reasonable accommodations that help individuals perform job-related tasks (e.g., sign language interpreters for deaf and hard of hearing employees and readers for employees who are blind or have low vision or learning disabilities). See 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(o).

[25]OASCR officials cited staffing constraints and policy updates influenced FY 2022 and FY 2023 training oversight activities.

[27]GAO, Disability Employment: Further Action Needed to Oversee Efforts to Meet Federal Government Hiring Goals, GAO‑12‑568 (Washington, D.C.: May 25, 2012) and Federal Workforce: Practices to Increase the Employment of Individuals with Disabilities, GAO‑11‑351T (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 16, 2011).

[28]In a 2018 Request for Information published in the Federal Register, 83 Fed. Reg. 10825 (Mar. 13, 2018), USDA describes the changes it intended to make in its reorganization of civil rights functions.

[29]This was a part of a wider effort by USDA to consolidate all administrative functions, including civil rights, at the department level within USDA.

[30]There may be other effects of the reorganization that we do not identify in this report.

[31]According to the 2018 Civil Rights Impact Analysis for OASCR, the office failed to meet statutory and regulatory requirements for timely case processing of discrimination complaints, which caused the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to issue sanctions and the department to lose appropriated funding.

[33]As noted previously, MD-715 provides policy, guidance, and standards to establish and maintain model EEO programs government-wide. MD-715 requires, among other things, that agencies identify EEO deficiencies in the workplace, develop and execute plans to eliminate those deficiencies, and report them annually to EEOC.

[34]29 C.F.R. § 1614.102(b)(2).