DOD REAL PROPERTY

Actions Needed to Improve Oversight of Underutilized and Excess Facilities

|

Revised March 11, 2025 to correct page 25. The corrected text should read: The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary of the Navy, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment and the Commandant of the Marine Corps, issues detailed guidance to the Marine Corps on how to assess and manage risks associated with real property, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property. (Recommendation 4) |

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106132. For more information, contact Alissa H. Czyz at (202) 512-4300 or CzyzA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106132, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate

Actions Needed to Improve Oversight of Underutilized and Excess Facilities

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD manages one of the largest real property portfolios within the federal government. This includes over 700,000 facilities with a replacement value of about $2.2 trillion, as of fiscal year 2023. DOD has faced long-standing challenges in optimizing its use of this property. GAO continues to monitor DOD’s efforts in improving the reliability of government-wide real property information as part of the Managing Federal Real Property high-risk area. The cost to build and maintain real property represents a significant financial commitment.

Senate Report 117-39, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, includes a provision for GAO to review DOD’s approach to reducing excess real property, including facility disposal.

This report examines the extent to which the military services (1) consistently and accurately report the use of their facilities, and (2) face challenges in managing and, when appropriate, disposing of facilities at selected installations. GAO reviewed guidance and documents, analyzed real property data, evaluated information from a non-generalizable sample of 19 installations that we based on the data of excess, surplus, and low utilization rates, and visited eight of these installations. GAO also interviewed relevant officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations to DOD, including to hold military services accountable for implementing utilization guidance and to assess and manage real property risks. DOD generally concurred with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

In order for the Department of Defense (DOD) to optimize its use of real property, it seeks to periodically review its inventory to identify unneeded or underused facilities. In support of this effort, DOD provided guidance to its components to ensure consistency of utilization measurement and reporting across the department. However, GAO found that the military services have not fully followed this guidance and are reporting inconsistent and inaccurate real property data. For example, the Air Force uses a standard methodology to calculate utilization rates for each facility, but the Navy and Marine Corps report average utilization rates across a set of similar facilities. Without taking actions to hold the military services accountable for following its utilization guidance, DOD will continue to lack a clear picture of the department’s portfolio of real property.

The military services have taken steps to improve efficiency in managing space utilization within DOD real property. For example, the Army is piloting a tool to improve visibility of space utilization in properties measured by square footage. However, the services continue to face challenges in optimizing space given the need to support unexpected requirements and maintain temporary facilities. For example, some installations are using relocatable structures, such as trailers, to fulfill immediate needs until permanent facility space is identified.

Other installations are maintaining older buildings at increased costs because replacement or demolition funds are insufficient, or because the buildings are historic and are required to be preserved. The services have not assessed and managed the risks associated with their management of real property because they have not issued guidance addressing these areas. If the services were to issue such guidance, they could better meet requirements for quality facilities, complete the demolition of old and unneeded facilities in a timely manner, and avoid costly partial renovations that do not adequately meet mission needs.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

ASD EI&E Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense

for Energy, Installations, and Environment

DAIS Data Analytics and Integration Support

DOD Department of Defense

ePRISMS enterprise Proactive Real-Property Interactive

Space Management System

FSRM Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, and

Modernization

MILCON military construction

O&M operation and maintenance

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense

RPAD Real Property Asset Database

RPAO Real Property Accountability Officer

RPSA Real Property Space Availability

USD A&S Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition

and Sustainment

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

March 3, 2025

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Department of Defense (DOD) manages one of the largest real property portfolios within the federal government and has faced long-standing challenges in fully using, or reducing, real property that exceeds its needs.[1] DOD’s real property includes land and facilities such as training areas, administrative buildings, hospitals, housing and dormitories, utility systems, and roadways. These properties require ongoing maintenance and repair to keep them in good working order.[2] Inadequate sustainment results in deferred maintenance and can lead to deterioration, potentially affecting DOD’s ability to support missions.[3]

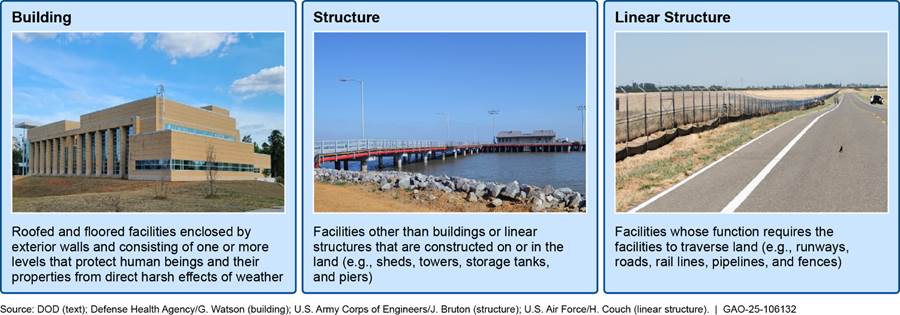

Operating and maintaining excess and underused properties consumes resources that could be eliminated from DOD’s budget or used for other purposes. In fiscal year 2023, DOD’s portfolio of real property included over 700,000 facilities (buildings, structures, and linear structures, such as roads and fences) with a combined replacement value of about $2.2 trillion. The cost to DOD to build and maintain real property represents a significant financial commitment. Over the past 5 years, DOD reported investing an average of $14.6 billion a year to build new facilities and $15.3 billion a year to maintain and repair already built facilities. However, DOD also reported a $181.1 billion deferred-maintenance backlog, suggesting it may be unable to effectively prevent its already-built real property from deteriorating.[4]

Retaining excess and underutilized space is one of the reasons federal real property management has been on GAO’s High-Risk List since 2003.[5] Due to challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic, DOD, along with other federal agencies, have had to continually adapt their use of property and reconsider how much and what type of space they need. To this end, in February 2024, the Deputy Secretary of Defense stated that, among other goals, installation managers and DOD senior leadership should have a common method to determine the quality of real property to guide timely decision and resource allocations.[6]

While we removed DOD support infrastructure from GAO’s High-Risk List, we continue to monitor DOD’s efforts in improving the reliability of real property information as part of the government-wide Managing Federal Real Property high-risk area.[7] Specifically, we have reported on DOD’s management of its infrastructure including issues with data reliability. For example, in 2014, we recommended that DOD could better track and consolidate underutilized property—potentially to identify and dispose of additional excess facilities.[8] We have also recommended several actions for DOD over the years to improve its management of its excess real property. DOD has implemented our recommendations by, among other things, issuing guidance intended to improve its data collection for real property utilization and condition, its planning for the demolition program, and its analysis of excess capacity.[9]

Senate Report 117-39, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, includes a provision for us to review DOD’s approach to reducing excess real property, including disposing of facilities.[10] In this report, we examine the extent to which the military services (1) consistently and accurately report the use of their facilities; and (2) face challenges in managing and, when appropriate, disposing of facilities at selected installations.

The scope of our review was limited to DOD facilities and did not include land. To address each of our objectives, we assessed DOD and military service guidance for managing real property. We obtained information from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment (ASD (EI&E)) and military services including annual reported data from DOD’s Real Property Asset Database (RPAD) and the military services’ systems of record to account for property.[11] Additionally, we analyzed information from a nongeneralizable sample of 19 installations that we selected based on their data on excess and surplus property and utilization rates. We visited and interviewed relevant officials at eight of these installations and we obtained documentation from the other 11 installations. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the site selection. For our complete scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2022 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of DOD Real Property

DOD real property consists of land and three types of facilities: buildings, structures, and linear structures (see fig. 1).

Responsibilities for Managing DOD’s Real Property

The Secretary of Defense is required to have inventory and financial records of DOD’s military installations.[12] Each service maintains data about their facilities in an inventory system. Each system populates into the DOD inventory system to help ensure efficient property management and identify potential consolidation opportunities.

DOD component heads, which include the heads of the military services, are assigned responsibilities related to managing their real property inventory.[13] The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD (A&S)) exercises overall policymaking and oversight responsibility of DOD real property.[14] The ASD (EI&E) provides additional guidance and procedures for implementing real property management and serves as DOD’s Senior Real Property Officer.[15]

Each military service issued guidance to manage its real property.[16] In managing its real property, each military service holds or makes plans to obtain and sustain the facilities needed for its missions and serves as the real property agent for the missions of other DOD components that its real property supports.[17] Specifically, each military service must:

· budget and financially manage for the acquisition and sustainment of real property needed to meet its mission;

· monitor the use of real property to ensure all holdings under its control are used to the maximum extent possible consistent with peacetime and mobilization requirements; and

· maintain an accurate and current inventory of those real property facilities in which it is the sole user or over which it exercises management responsibility.

The military services’ processes for managing and monitoring real property occurs at the installation level through the appointment of a real property accountable officer (RPAO).[18] Each RPAO is responsible for ensuring that formal property records, systems, and financial information are established and maintained. Physical inventories of each real property asset are required every 5 years, except for those real property assets designated as historic, which must be reviewed and physically inventoried every 3 years.

Service inventories of real property include current counts and information regarding status, condition, utilization, and remaining useful life, among other elements.[19] Inventory counts and information must be current as of the last day of each fiscal year. Military services are required to periodically review real property holdings to identify unneeded and underused property.

When real property is no longer needed for current or projected defense requirements, it is DOD’s policy to dispose of it.[20] The military services use several means to dispose of excess real property, such as change of ownership or demolition. Facility demolition is typically undertaken when the extent of deterioration is such that the facility can no longer be economically maintained or is a health and safety hazard. The overall intent is to reduce unnecessary infrastructure and optimize limited maintenance funding. In fiscal year 2022, we found that DOD reported the total amount of disposal for all services was 2,170 facilities.

DOD’s disposal process begins with the periodic review of its real property holdings to identify unneeded and underused property.[21] The military departments must notify other military departments, the combatant commands, DOD agencies, and field activities of the availability of unneeded property. If a firm commitment is not received within 60 days of notification, the military department holding the property may proceed with disposal. In fiscal year 2022, DOD reported that the total amount of excess for all services was 2,283 facilities, which included buildings and structures as well as linear structures such as roads, fences, and wires.[22]

Real Property Accounting and Reporting

All DOD components submit current and forecasted data from their real property inventory systems to the DOD enterprise inventory system. The Business Systems and Information Directorate in ASD (EI&E) issues policy and user guides for DOD’s IT architecture and is responsible for ensuring common business processes and data interoperability between inventory systems. This directorate also facilitates analysis of DOD’s real property portfolio and reporting through its Data Analytics and Integration Support (DAIS) system. This system supplies a common platform for DOD’s real property inventory and is an official repository for real property data, real-time queries, and requests for current asset information.

ASD (EI&E) produces the annual Base Structure Report, which is a snapshot of DOD real property inventory as of September 30 of each fiscal year.[23] DAIS provides real property asset information used to create the data set that is the basis of the Base Structure Report. ASD (EI&E) uses the annual report to develop responses to queries from other government entities like the Office of Management and Budget and the Congress. The Secretaries of the military departments are to maintain accuracy of their current real property inventory within DAIS with near real-time data updates.

Sources of Funding for Real Property

Operation and maintenance (O&M) is DOD’s largest single category of appropriations, and is used to support day-to-day programs, projects, and activities, including real property operations and maintenance. Each service receives its own O&M appropriation that it uses for base operations, facilities, sustainment, restoration, and modernization out of program from subaccounts, such as Base Operations Support and the Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, and Modernization program (FSRM). Amounts allocated to FSRM support activities necessary to keep facilities in good working order, including regularly scheduled maintenance and major repairs or replacements of facility components. DOD uses a statistical model to estimate how much it should budget for FSRM each fiscal year based on facility size, average annual unit sustainment cost, location costs for labor and materials, and inflation.[24] DOD and the military services also receive a military construction (MILCON) appropriation that supports construction projects over $4 million. Amounts for individual MILCON projects are authorized and appropriated after DOD provides a project justification and cost estimate as part of the annual budget process.

Facility Utilization Data Are Inconsistent Across Military Services and Are Inaccurate

It is DOD policy to optimize use of its real property to minimize expenditures for new real property and the maintenance of unneeded property. DOD guidance requires the military services to periodically review their real property to identify and report unneeded and underused facilities and include utilization data in real property inventories.[25] In 2016, ASD (EI&E) provided guidance intended to ensure consistency of utilization measurement and reporting within DOD, and to expand and clarify the requirements of DOD Instruction 4165.70.[26] The guidance established specific methods of measurement and reporting of utilization based on asset type and operational status. According to officials from ASD (EI&E), supplementary guidance is issued annually during DOD’s RPAD data collection process.

Among other things, DOD utilization rate guidance provides that utilization rates be calculated for buildings, structures, and linear structures.[27] Additionally, for buildings in active or semi-active operational status—and those structures and linear structures that have an associated basic facility requirement—installation officials use the basic facility requirement in calculating the utilization rate. The basic facility requirement refers to space needed to support the mission. DOD calculates the utilization rate by dividing the basic facility requirement by the space available for the main function of the building. Additionally, the utilization rate guidance requires DOD components to physically validate variables used in the calculation of utilization rates—specifically, real property operational status and key data in basic facility requirements.

Each military service uses its own methodologies and processes to collect, report, and calculate utilization data for its facilities, but they have not addressed some data challenges associated with these efforts.

Air Force. According to Air Force guidance, each installation’s Real Property Accountable Officer (RPAO) is responsible for completing an accurate and complete real property inventory that reflects all facilities, assigned occupants and users, and excess property.[28] Air Force officials said the RPAOs use a standard methodology for calculating utilization rates and manually enter these rates into the Air Force’s real property information system. Each RPAO submits annual certification of inventory accuracy to the Air Force Civil Engineer Center, which validates the accuracy of all real property inventory data.

Air Force Installation and Mission Support Center and Air Force Civil Engineer Center officials told us that this process was established to align with requirements set forth in ASD (EI&E)’s 2016 policy update on utilization reporting.[29] However, these officials noted that the Air Force implemented these changes in December 2020, rather than August 2018, when DODI 4165.70 was revised to integrate the contents of ASD (EI&E)’s 2016 policy update. As a result, although Air Force officials stated they have made progress in capturing utilization, they stated some of their data may not reflect current Air Force standards because they were entered prior to 2020 using an old methodology.

Navy and Marine Corps. Both the Navy and Marine Corps calculate an average utilization rate across a set of similar facilities rather than calculate utilization of individual facilities. The Navy’s real property information system, used by both services, automatically calculates utilization rates for similar facilities within a defined geographic area.[30] Navy and Marine Corps installation officials told us that use of average utilization rates can limit their understanding of the utilization of any individual facility, and sometimes make it difficult to determine the exact cause of inaccurate data. Additionally, Navy and Marine Corps installation officials noted that data on basic facility requirements were less frequently updated than some other real property data, and this could affect utilization rate accuracy. For example, at Naval Base Kitsap, officials explained that a pier showing a 3-percent utilization rate in RPAD was not actually underutilized because it was regularly used by the Coast Guard, which was not reflected in the system. Similarly, during a visit to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, we observed a headquarters building with a utilization rate of 28 percent in RPAD, but the building appeared to be nearly fully occupied. In both cases, installation officials believed that incorrect basic facility requirements may have affected the accuracy of utilization rates, despite DOD’s utilization guidance requiring that the services physically validate requirements data.[31]

Army. Army officials stated the service directly inputs facility utilization rates into its real property information system. However, we found since fiscal year 2020 that the Army has not reported any underutilized property in active operational status. For example, in the fiscal year 2022 RPAD data, the Army reported 5,521 underutilized facilities, all of which showed 0-percent utilization. All facilities were in an inactive status (e.g., closed). Further, officials at White Sands Missile Range and Joint Base Lewis-McChord told us that the Army’s Installation Management Command instructed installations to enter either 100 percent (fully used) or 0 percent (not used) for their property. According to officials from White Sands Missile Range, a 100-percent utilization rate means one or more people used the facility. This practice of entering either 100 percent or 0 percent utilization rates for property utilization is contrary to DOD’s utilization guidance, which specifies that buildings should have their utilization rates calculated by dividing facility requirements by space available.

We found that the services have made limited progress in implementing DOD’s 2016 policy and annual guidance and have not established processes that enable them to consistently and accurately collect and report utilization rate data. Further, military service officials said that they are aware they are not following ASD (EI&E) guidance and that they expect utilization data are inaccurate. Since ensuring the accuracy of utilization rates is not a priority, DOD has not held them accountable for following its guidance and improving data quality.

Consistent utilization measurement and reporting supports agency- and government-wide oversight, efficient use, and management of DOD’s real property. If DOD took actions to hold military services accountable for following its utilization guidance for the collection of quality data on utilization rates for facilities, DOD could have a clearer picture of the department’s portfolio of real property and provide more accurate utilization information to congressional decision-makers.

Installations Have Taken Steps to More Efficiently Manage and Dispose of Facilities but Face Challenges

Military Services and Installations Have Taken Steps to Manage Space Utilization

The military services have sought to improve the efficiency of space utilization and have implemented initiatives to limit growth of their real property footprints by having new construction offset by disposal of a similar amount of square footage. For example, they established “demolition banks,” which means that increased space needs on installations with mission growth can be offset by disposal of space on other installations.[32] Additionally, the Navy has established goals to reduce administrative and warehouse space.

The services have also increased installations’ access to tools for space utilization management. For example, the Navy has a Shore Facilities Planning System as part of its real property database. This system is a tool that is used to develop and implement site-specific solutions to acquire, maintain, optimally utilize, and dispose of assets by analyzing the facilities’ missions, conditions, uses, and utilization. Additionally, Navy officials stated they use the Facility Investment Model to determine if facilities are economical to repair and to select facilities for demolition.

Officials stated that the Army is piloting an online Real Property Space Availability (RPSA) tool as part of its enterprise Proactive Real-Property Interactive Space Management System (ePRISMS) to improve visibility of space utilization in properties measured by square footage.[33] We observed one Army installation using this tool, but we observed other Army installations using their own internal systems of record to manage the occupants and space availability. Additionally, at a Marine Corps installation we visited, one official maintained a spreadsheet of occupants and available spaces, and this designated official who managed the space utilization of the installation was personally visiting each facility to verify the accuracy of that spreadsheet.

Installations Face Challenges Optimizing Space to Meet Current Needs and Unexpected Requirements

Officials at multiple installations told us that optimizing space at facilities is a challenge given their need to support unexpected requirements, maintain facilities intended to be temporary, and accommodate changes to DOD’s telework policies.

· At

selected installations, we identified instances where the services had

insufficient facilities to meet their needs. Officials from five of eight

installations we visited told us their installations did not have significant

numbers of underutilized facilities and noted it was more common for them to

encounter challenges finding the space needed to meet unanticipated mission

requirements. For example, officials at Joint Base Lewis-McChord told us there

were 22 buildings that were in poor condition that they deemed as excess and

placed on the disposal list. However, they were later notified of a requirement

to station units at the installation. Consequently, they removed the buildings

from the disposal list and sought additional funding to renovate and maintain

the buildings.

In another instance, officials at Fort Bliss told us they were directed by the

Army, and promised funding, to build centers near barracks and dorms that

provide programs to improve service member physical fitness, sleep, nutrition,

and mental and spiritual readiness. However, they said the Army did not provide

the funding and Fort Bliss does not have facilities that can be renovated to

serve as these centers within the required walking distance from the barracks.

As a result, officials used an open area rather than a building to provide some

of these programs.

· Officials at five installations we visited said they often use relocatable facilities, such as trailers, to temporarily meet space requirements.[34] According to officials, often these requirements identify a need to upgrade permanent facilities that can lead them to use relocatable facilities for a longer period of time than originally anticipated. For instance, at Naval Base Kitsap, officials told us that they had to use relocatable facilities for temporary administrative space (see fig. 2). However, they needed the space longer than anticipated, and eventually incorporated maintenance for these temporary facilities into their current and future budgets.

· When

we visited the installations, officials at multiple locations told us they were

unsure how to address underused space resulting from changes in telework policies.

For example, officials at White Sands Missile Range and Marine Corps Air

Station Cherry Point stated that there were spaces in the administrative

buildings that were not occupied during business hours because employees were teleworking.

One official told us that sometimes tenants seeking office space assume the

empty areas are available, but, at times, those unoccupied spaces are reserved

for those who use it on a part-time basis.

In January 2025, DOD provided guidance on returning employees to in-person

work.[35]

We have an ongoing review examining DOD’s telework and remote work practices,

and plan to report on these issues later in 2025.

Installations Face Challenges Prioritizing Resources When Maintaining, Demolishing, or Building Facilities

In addition to challenges related to optimizing the use of space at installations, we found that the military services encounter challenges identifying excess facilities and determining whether to demolish or maintain them. We found that officials at multiple installations were limited in their ability to identify excess facilities because of (1) inconsistent use of facility labels, (2) maintenance at older facilities increasing costs, and (3) prioritization for sustainment funding over demolition.

We also found that the installations we visited did not always reliably identify facilities that were excess. Officials at installations have assumed risks by not identifying and disposing of properties in a timely manner, such as paying to renovate or mothball properties that could be disposed of.[36] However, officials stated that sometimes facilities in poor condition are renovated because there are insufficient funds to replace them.

Inconsistent use of facility labels. At five of the installations we visited, we found that officials do not label facilities as excess when they first identified them as such. For example, instead of identifying property as excess, military installation officials stated they identified property with other labels such as “closed,” “nonfunctional,” or “caretaker,” even if they believed the property was excess. The officials’ definition of “excess” is not needed for their mission or should be demolished. Guidance provides definitions for the use of these other designations for facilities that are not excess. However, we found that officials were designating a facility as being excess only when it was being prepared for disposal. For example, at Fort Bliss, we observed facilities designated as “closed” although they were not needed for a mission. Because the facilities were adjacent to a school outside the installation, officials explained that the buildings could pose a safety hazard because students could explore these abandoned facilities and get hurt. However, the buildings were not yet funded or designated for disposal.

Maintaining older facilities at increased costs. Some military installations have older buildings—including historic buildings— that require specific maintenance and are costly to keep in good condition. For example, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Installations, Energy and Environment stated that the Navy and Marine Corps infrastructure portfolio as a whole continued to age, with the portfolio containing numerous facilities that were: beyond their service life, in poor condition, inefficient, and were not resilient to certain threats and hazards.[37] Navy officials stated that installations are often driven to maintaining these facilities because there are insufficient funds to replace the buildings, but mission requirements remain. However, these older buildings may require additional upgrades if any refurbishment work is done to them.[38]

For example, officials at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point explained that when a natural disaster hits and damages buildings, the buildings must be repaired and restored to their previous condition, even though they are not being used. Specifically, one unaccompanied housing building was closed and not used for safety reasons. Installation officials determined it was not cost-effective to fix recurring flooding and water damage to the basement. However, officials were still required to fund repairs to the windows and roof after a hurricane (see fig. 3).

Other service officials stated that some other older buildings are designated as historic and are required to remain in acceptable condition, which can put a strain on sustainment resources. For example, officials at Fort Bliss explained that they have some historic buildings that are not in use because of their poor condition and age. However, they noted that Fort Bliss is still required to do certain types of maintenance on these buildings, such as replacement of their roofs. For instance, officials stated that the building in figure 4 is designated as historic and must be maintained (see fig. 4).

Military installations can also mothball facilities by removing them from active use but maintaining them in their inventories with the intention of using them later. However, the practice of mothballing facilities can further put a strain on sustainment funding because some sustainment is required based on the condition of mothballed buildings to avoid progressive deterioration.[39] For example, officials at Fort Bliss stated that they created and awarded a contract to restore the installation’s mothballed facilities that was to be supported with sustainment funding. However, according to officials, there were so many maintenance requests for these older facilities that the contractor could not fulfill all of them with available funding.

Priority for sustainment funding over demolition. The military services primarily use their O&M appropriations to fund facility sustainment and restoration. However, as we reported in 2022, DOD did not meet its annual funding goal of 90 percent or higher of its facility sustainment requirements and funded only about 80 percent of its needs.[40]

Amounts allotted for sustainment may be used to pay for demolition of excess facilities. However, installation officials told us they were faced with difficult choices as to whether to take the risk to prioritize maintenance or demolition. Officials told us that facility sustainment requirements were not fully funded each year, so they preferred to not use sustainment funding to pay for demolition.

· Navy officials stated that since mission requirements, life, health, safety, and preventative maintenance for the preservation of existing facilities are the main priorities, there was generally little to no funding available for demolition. Instead, they may submit a proposal for specific demolition funds or link the proposed demolition to a new construction project.

· The military services generally allot specific amounts for demolition, such as the Army’s Facility Reduction Program funding, but installations are required to submit requests to obtain this highly competitive funding.[41] In some instances, the lack of available funding can lead to delays in demolition. For example, the Navy typically sets aside eligible money for demolition regionally, as mentioned above, but not all requests are fulfilled. Navy headquarters officials stated they had paused designating specific amounts for demolition to address other Navy sustainment priorities. They estimated the Navy’s backlog of demolition projects would cost about $700 million to address; about $229 million was funded in fiscal year 2024 and $170 million in fiscal year 2025.

Installation officials told us that even when they identify property as excess because it is in bad condition or badly configured to meet mission needs, they still sometimes need the space, but do not have funding to demolish the facility and construct a new one. As a result, they try to take cost-efficient, short-term measures to meet needs, sometimes without success. For example, at Fort Bliss, officials told us that to meet a requirement, they removed a mothballed facility that had been on the demolition list for 8 years and renovated it for $2.3 million. However, the renovations were not sufficient to bring the facility up to standards and, after complaints from users of the facility, the Army directed officials at that installation to discontinue its use. Officials ultimately obtained $19 million to renovate another facility to replace it.

To enhance management of installation readiness, DOD has taken steps to increase funding for demolition. For example, the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Energy, Installations, and Environment stated that the Air Force plans to increase its demolition program almost fivefold to $136 million over the next 5 years.[42]

Installations Face Challenges in Executing Demolition

Military installations face challenges in executing demolition of excess facilities. According to officials, installations often wait to demolish excess property until there is new construction in close proximity. However, there may be other instances where installations may not be able to find a way to include a building identified for demolition in a nearby new construction project. In these instances, the building may have to remain on the installation’s inventory. For example, officials at White Sands Missile Range explained that the building shown below was not adjacent to or nearby a new project and was not a priority to allocate sustainment amounts for demolition (see fig. 5).

Further, a building may be declared as excess and placed on an installation’s demolition list but may not be demolished immediately based on project priority and available funding. For example, a building at Joint Base Lewis-McChord was declared excess in 2017 and was placed on the demolition list (see fig. 6). However, the building was still in place during our visit.

Additionally, there have been instances where the timing of facility disposal does not fit into the timeline of the new construction project. For example, at Fort Bliss, installation officials proposed a MILCON project to build a new hospital and demolish the one already at the installation. However, the MILCON project was delayed and was not finished until 10 years after it was approved due to design errors, and increased costs.

Further, officials stated that the old facility could not be demolished because an adjacent Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) building shares utilities that could not be separated or destroyed. The VA had planned a MILCON project for a new building that would have separated utilities from the old hospital, but its construction was also delayed. Since DOD and VA ultimately expended the MILCON funding to complete the delayed projects, the MILCON amounts designated for demolition were no longer available. Installation officials were unsure how they would fund the $14-million disposal of the older hospital (see fig. 7).

The Military Services Have Not Evaluated Risk When Managing Real Property

The military services have experienced challenges optimizing their federal property portfolio and assessing and managing risks associated with their real property inventory. It is a broad goal of the U.S. government to, among other things, optimize the federal real property portfolio to support agency mission needs and manage costs through strategic planning.[43] Further, ASD (EI&E) guidance states that facility renewal should include improving estimates of renewal costs through a risk-management framework that ensures requirements are weighted against all other urgent and compelling needs of the federal agency to meet its mission.

According to OSD officials, the department has delegated responsibility for optimizing real property and managing risks associated with renewal costs to the military services. Military service officials said that they rely on individual installations to optimize use of real property in their locations. However, installation officials told us that they are limited in their ability to optimize their facilities because the military services have not issued detailed guidance specifying how they should assess and manage risks associated with their real property inventory, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property.

Officials at six installations we visited stated there are opportunities to reduce their office space or to find more efficient use of the space. They also said that the military services have established general goals for space reduction but have not issued detailed guidance on how to achieve these goals, how they fit with other mission initiatives and requirements, or how to assess and manage risks. If the military services issued such guidance, installations would be better positioned to meet service requirements for quality facilities and avoid costly, partial renovations that do not adequately meet mission needs.

Conclusions

DOD manages one of the largest real property portfolios within the federal government and has faced long-time challenges in meeting the needs of the military services to maintain, renovate, expand, reduce, or demolish facilities as needs change.

The military services have collected and reported selected data about their underused property but have not maintained consistent or accurate information on facility utilization rates. A result, decision-makers have limited information to enable them to make timely decisions about how to optimize the military services’ use of space. Officials could take advantage of opportunities to optimize their space utilization and provide accurate information to DOD decision-makers who are looking for spare capacity for basing decisions or who are working to develop budget requests related to real property management. Specifically, if DOD developed actions to hold the services accountable for implementing DOD’s utilization rate guidance, military service officials could more fully inform DOD and congressional decision-makers of the services’ portfolios of real property. As a result, this would better support efforts to make timely decisions about how to resource DOD’s ever-changing property needs.

Additionally, the military services have taken steps to increase efficiency in managing real property and have considered how to improve the timeliness of demolition of unneeded facilities. However, they continue to face challenges in determining priorities for real property management and demolition in the absence of having assessed and managed risks associated with their real property inventory or having direction of the military services’ priorities for facility renewal. If the military services issued detailed guidance specifying how to assess and manage risks and competing priorities associated with real property, they could have greater assurance that they will be able to make timely progress in meeting requirements for quality facilities. They would also be better positioned to avoid costly projects that do not adequately meet the military services’ needs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment, in coordination with the military services, holds DOD’s components and personnel accountable for implementing utilization rate guidance and developing actions to enforce that guidance consistently and accurately for all facilities across the military services. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary of the Army, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment, issues detailed guidance on how to assess and manage risks associated with real property, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary of the Navy, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment, issues detailed guidance to the Navy on how to assess and manage risks associated with real property, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary of the Navy, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment and the Commandant of the Marine Corps, issues detailed guidance to the Marine Corps on how to assess and manage risks associated with real property, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary of the Air Force, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment, issues detailed guidance on how to assess and manage risks associated with real property, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, DOD concurred with three of our recommendations. DOD partially concurred with two other recommendations to issue detailed guidance to the Navy and the Marine Corps on how to assess and manage risks associated with real property, including determining how to weigh competing priorities relating to sustainment, use, and disposal of property. Regarding the entity addressed in these recommendations, DOD suggested combining them into one recommendation under the Secretary of the Navy because the recommended action more appropriately aligns with the authority and responsibility of the Navy and Marine Corps as a single military department. GAO amended the recommendations and clarified the responsible designee but kept them as separate recommendations in keeping with GAO’s practice of presenting a separate recommendation to each entity. DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy, and the Department of the Air Force. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-4300 or CzyzA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Alissa H. Czyz

Director

Defense Capabilities and Management

This report provides information on DOD’s processes for identifying, managing, and reducing excess and underutilized facilities.[44] Specifically, it examines the extent to which the military services (1) consistently and accurately report the use of their facilities; and (2) face challenges in managing and, when appropriate, disposing of facilities at selected installations. In conducting our work, we obtained and examined documents from DOD and the military services, including departmental and service guidance for managing real property. We collected information on key information systems used in managing DOD real property, including DOD’s Real Property Asset Database (RPAD) and the military services’ systems of record to account for property. We also obtained and analyzed information from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and military services, including data on excess, surplus, and underutilized property for fiscal years 2018 through 2022.[45]

We also used RPAD data from fiscal year 2022 to select a nonprobability sample of 19 installations to contact based primarily on the following factors: (1) the amount of property in an excess status as reflected in DOD’s RPAD data; (2) the amount of property with a low Real Property Asset Utilization Rate below 60 percent as reflected in DOD’s RPAD data; and (3) a ranking among the top five installations in terms of excess, surplus, and low utilization rates per military service.[46] We determined that the data were sufficient to help identify sites.

We also considered the following as secondary factors in site selection: (a) higher plant replacement values and annual operating costs; (b) the presence of real property in excess status or surplus status for 10 years; the presence of leased property on or near those locations; (c) locations that DOD officials recommended for us to visit—or not visit—depending on the rationale for their recommendations; and (d) locations with known efforts to address the disposition, or more efficient management of real property, based on our research and information provided by DOD and military service officials.

We conducted visits to eight of the installations included in our sample. In selecting installations to visit, we chose at least one per military service (with the exception of the Space Force because of the limited amount of data and real property the branch is responsible for). We selected installations to visit to proportionally reflect the distribution of excess or “underutilization” rates rather than selecting an equal number of installations per service.

Based on these factors, we chose to visit:

· Fort Bliss, Texas;

· Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington;

· White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico;

· Naval Base Kitsap, Washington;

· Naval Support Activity South Potomac, Virginia;

· Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, District of Columbia;

· Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina; and

· Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

We sent questionnaires to the remaining 11 installations:

· U.S. Army Garrison Hawaii, Hawaii;

· Fort Huachuca, Arizona;

· Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii;

· Naval Base Coronado, California;

· Naval Station Newport, Rhode Island;

· Air Combat Command Acquisition Management and Integration Center, Virginia;

· Joint Base Charleston, South Carolina;

· Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, New Jersey;

· Hanscom Air Force Base, Massachusetts;

· Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, California; and

· Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina.

Finally, we interviewed officials from DOD, the General Services Administration, and the Congressional Budget Office. In addition to officials from the installations named above, we spoke with DOD officials from the following organizations:

|

Component |

· Organization |

|

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment |

|

Department of the Army |

· Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G9 (Installations) · U.S. Army Installation Management Command |

|

U.S. Navy |

· Commander, Navy Installations Command · Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command |

|

Department of the Air Force |

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Energy, Installations, and Environment · Headquarters, Air Force Office of Logistics, Engineering and Force Protection · Air Force Installation and Mission Support Center · Air Force Civil Engineer Center |

|

U.S. Marine Corps |

· Marine Corps Installations Command |

Source: GAO. | GAO 25-106132

We conducted this performance audit from June 2022 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Alissa Czyz, (202) 512-4300, CzyzA@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, GAO staff who made key contributions to this report include Gina Hoffman (Assistant Director); Natasha Wilder (Analyst in Charge); Ed Yuen. Other contributors were: Chanée Gaskin, Christopher Gezon, Chad Hinsch, Phoebe Iguchi, David Jones, Felicia Lopez, Richard Powelson, and Steve Pruitt.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Excess real property is real property that a federal agency no longer needs to carry out its program responsibilities. If there is no further need for the real property within the federal government, the agency determines that real property is “surplus” and may be made available for other uses outside of the federal government. In this report, we refer to both excess and surplus real property as “excess.” Underused real property is not fully used or underutilized real property, which is separate from excess and surplus.

[2]Facility sustainment includes regularly scheduled adjustments and inspections, preventive maintenance tasks, and emergency response and service calls for minor repairs. Sustainment also includes major repairs or replacement of facility components that are expected to occur periodically throughout the life cycle of facilities. This includes regular roof replacement, refinishing of wall surfaces, repairing and replacement of heating and cooling systems, replacing tile and carpeting, and similar types of work.

[3]Federal financial accounting standards define deferred maintenance and repairs as maintenance and repairs that were not performed when they should have been or were scheduled to be, and which are put off or delayed for a future period. Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board, Definitional Changes Related to Deferred Maintenance and Repairs: Amending Statement of Federal Financial Accounts Standards 6, Accounting for Property, Plant and Equipment (May 11, 2011).

[4]DOD, Department of Defense Agency Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2023, Table RSI-1, “Real Property Deferred Maintenance and Repair (Excluding Military Family Housing)” (Nov. 15, 2023).

[5]GAO, Federal Real Property: Preliminary Results Show Federal Buildings Remain Underutilized Due to Longstanding Challenges and Increased Telework, GAO‑23‑106200 (Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2023).

[6]Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Resilient and Healthy Communities (Feb. 14, 2024).

[7]GAO, High-Risk Series, Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021).

[8]GAO, Defense Infrastructure: DOD Needs to Improve Its Efforts to Identify Unutilized and Underutilized Facilities, GAO‑14‑538 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 8, 2014).

[9]GAO, Defense Real Property: DOD Needs to Take Action to Improve Management of Its Inventory Data, GAO‑19‑73 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 13, 2018).

[10]S. Rep. No. 117-39, at 337-38 (2021).

[11]The services we included were the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force, but excluded the Space Force because of the limited amount of data and real property the branch is responsible for.

[12]10 U.S.C. § 2721. The Secretary of Defense is required to prescribe guidance on the maintenance of the records.

[13]Department of Defense Directive (DODD) 4165.06, Real Property (July 19, 2022); Department of Defense Instruction (DODI) 4165.14, Real Property Inventory and Reporting (Sept. 8, 2023); and DODI 4165.70, Real Property Management (Apr. 6, 2005) (incorporating Change 1; Aug. 31, 2018).

[14]DODI 4165.06.

[15]DODI 4165.70.

[16]For example, see Army Regulation (AR) 405-70, Utilization of Real Property (May 12, 2006); Commander, Navy Installations Command (CNIC) Instruction 11011.1, Utilization of Real Property on CNIC Installations (Oct. 29, 2018); Marine Corps Order 11000.12, Real Property Facilities Manual, Facilities Planning and Programming (Sept. 8, 2014); Air Force Policy Directive 32-10, Installations and Facilities (July 20, 2020).

[17]A real property agent is the military department responsible for performing all real property functions for a DOD component as assigned by the Secretary of Defense, Deputy Secretary of Defense, or the February 22, 2021, Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum.

[18]DODI 4165.14.

[19]DODI 4165.70.

[20]Real property that is identified as excess to the programs of a military department may be transferred, at no cost, among the armed forces or offered to other DOD components. Real property for which there is no foreseeable military requirement, either in peacetime or for mobilization, must be promptly reported for disposal to the General Services Administration or the Department of the Interior in the case of land withdrawals.

[21]DODI 4165.70.

[22]The amount of excess identified in fiscal year 2022 was carried over from the prior year and may have been identified in the same year, but not yet reported as disposed of.

[23]The senior property officer of each agency is required, on an annual basis, to provide to the Director of the Office of Management Budget and the Administrator of General Services Administration (GSA), information that lists and describes assets under their jurisdiction, custody, or control. The GSA, in consultation with the Federal Real Property Council, maintains a single, comprehensive, and descriptive database of all real property under the custody and control of all executive branch agencies. Exec. Order No. 13327, Federal Real Property Asset Management, 69 Fed. Reg. 5897 (Feb. 6, 2004) (signed Feb. 4, 2004).

[24]DOD 7000.14-R, Financial Management Regulation, vol. 2B, chap. 8, “Facilities Sustainment and Restoration/Modernization” (December 2016).

[25]DODI 4165.70.

[26]ASD (EI&E) Memorandum, Real Property Update for Reporting Utilization of Real Property Assets (Dec. 19, 2016). DODI 4165.70 requires the military departments to maintain a current inventory count and current information regarding the cost, functional use, status, condition, utilization, present value, maintenance, and management, recapitalization investments, and remaining useful life of each individual real property in their inventory. Service department inventory counts and associated information must be current as of September 30 of each fiscal year.

[27]ASD (EI&E) Memorandum, Real Property Update for Reporting Utilization of Real Property Assets.

[28]Department of the Air Force Instruction (DAFI) 32-9005/AFGM 2020-01, Air Force Guidance Memorandum to AFI 32-9005, Real Property Accountability, § 2.8.7 (Dec. 23, 2020). AFI 32-9005 was most recently updated in July 2024. We did not include the updated guidance in this report, as the update occurred outside of our reporting time frame.

[29]In 2016 DOD issued guidance addressing this issue in response to our prior work noting the problems in this area. In the guidance, ASD (EI&E) established policy to ensure consistency of utilization measurement and reporting within DOD, and to expand and clarify the requirements of DOD Instruction 4165.70 to maintain current and up-to-date information regarding real property utilization. The guidance established specific methods of measurement and reporting of utilization based on asset type such as structures, linear structures, and buildings. The utilization rate for buildings is to be calculated, in part based on a facility’s operational status, such as active, semiactive, or caretaker. Buildings in active or semiactive operational status, specifically, should calculate their utilization rates by using the basic facility requirement, and dividing by the space available for the main function of the building. Based in part on this action, we removed this area from GAO’s High-Risk List in March 2021. ASD (EI&E) Memorandum, Real Property Update for Reporting Utilization of Real Property Assets (Dec. 19, 2016).

[30]The Marine Corps is an independent component of the Department of the Navy.

[31]DODI 4165.14 requires that each real property asset record is reviewed every 3 to 5 years based on property type designations, and that such a review include a physical inventory of each asset. ASD (EI&E) Memorandum, Real Property Policy Update for Reporting Utilization of Real Property Assets, requires that basic facilities requirements—which are used in calculating some utilization rates—are validated on the same schedule as physical inventories.

[32]Demolition is one method of disposal available to DOD components.

[33]The Army is piloting an online real estate tool called the Real Property Space Availability (RPSA) at 10 installations, and is required to evaluate and report to Congress by February 15, 2025, on whether the program achieved efficiencies in real property management, provided a better marketing tool regarding available space at Army installations to better utilize space, and a better means of quantifying existing space and how it is utilized. William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 2866 (2021). According to the DOD Inspector General, the Army completed the initial steps of the pilot as of December 2022. DODIG-2023-055, Evaluation of the Army’s Online Real Property Space Availability Application (Mar. 8, 2023).

[34]A relocatable facility is specially designed and constructed to be readily erected, disassembled, transported, stored, and reused. Examples of relocatable facilities include, but are not limited to, trailers, container express boxes, sheds on skids, tension fabric structures, and air-supported domes. DODI 4165.56, Relocatable Facilities (June 23, 2022). According to installation officials, relocatable facilities are generally not real property, but when used for an extended period, maintenance needs have been incorporated into budgeting and planning and may have been converted into real property.

[35] Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Guidance on Presidential Memorandum, "Return to In-Person Work" (Jan. 24, 2025); Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Implementation of Presidential Memorandum, "Return to In-Person Work"” (Jan. 24, 2025); Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Initial Department of Defense Implementation Guidance, Return to In-Person Work” (Jan. 31, 2025).

[36]Mothballing is a temporary closure of a building when all means of finding a productive use for the building have been exhausted or when funds are not currently available to put a deteriorating structure into a useable condition. This process can be a necessary and effective means of protecting the building while planning the property’s future, or raising money for a preservation, rehabilitation, or restoration project.

[37]State of DOD Housing and Aging Infrastructure; Hearing Before the House Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Readiness, 118th Cong. 1 (2024) (statement by Meredith Berger, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Installations, Energy, and Environment).

[38]DOD manages and maintains cultural resources, including facilities, under its control through a program that considers preservation, mission support, and responsible stewardship. It is the department’s goal that historic buildings and structures are maintained in good condition and be used to support mission needs. DODI 4715.16, Cultural Resources Management (Sept. 18, 2008) (incorporating Change 2, Aug. 31, 2018). For older buildings, including historic facilities, compliance with current structural regulations is required when certain triggering actions occur, such as replacement or change of occupancy level from low to high. For example, window replacement in an existing building requires that the new windows be able to withstand certain blast environments.

[39]Navy officials stated that Commander, Navy Installations Command, has issued direction that no funds be spent on facilities designated for demolition.

[40]GAO, Defense Infrastructure: DOD Should Better Manage Risks Posed by Deferred Facility Maintenance, GAO‑22‑104481 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 31, 2022).

[41]The Army Corps of Engineers’ Facility Reduction Program provides a fast-track, efficient method for demolition of excess facilities. The program provides demolition support for multiple DOD installations and assists with project development and validation of requirements among other services.

[42]State of DOD Housing and Aging Infrastructure; Hearing Before the House Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Readiness, 118th Cong. 1 (2024) (statement by Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Energy, Installations and Environment) Ravi Chaudhary).

[43]To “optimize” the real property portfolio is to ensure that government entities have the right type of property, in the right amount, at the right location, at the right cost, and in the right condition to support mission requirements. OMB Memorandum M-20-10, Addendum to the National Strategy for the Efficient Use of Real Property (March 6, 2020).

[44]Excess real property is real property that a federal agency no longer needs to carry out its program responsibilities. If there is no further need for the excess property within the federal government, the property is determined to be “surplus” and may be made available for other uses outside of the federal government. In this report, we generally refer to both excess and surplus real property as “excess” to the Department of Defense (DOD).

[45]To determine what property was underutilized, we looked at DOD real property that had a utilization rate in DOD’s Real Property Asset Database of 60 percent or less. According to officials from the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment (ASD (EI&E)), DOD uses this rate to determine which property to report as underutilized to the Federal Real Property Council, which no longer uses utilization rates. DOD provided data that included underutilized properties along with excess, surplus, and disposed properties. We excluded excess, surplus, and disposed properties when measuring properties with a utilization rate of 60 percent or less.

[46]We analyzed data from fiscal year 2022 as it was the most current data available at the time that we conducted our site visit selection.