401(k) PLANS

Industry Data Show Low Participant Use of Crypto Assets Although DOL’s Data Limitations Persist

Report to the Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

November 2024

GAO-25-106161

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106161. For more information, contact Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen at (202) 512-7215 or nguyentt@gao.gov, or Michael E. Clements at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106161, a report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives

November 2024

401(k) PLANS

Industry Data Show Low Participant Use of Crypto Assets Although DOL’s Data Limitations Persist

Why GAO Did This Study

Retirement savings in 401(k) plans totaling more than $6.7 trillion in 2022 are a key component of the U.S. retirement system. Since 2022, some investment firms have offered options for participants to invest in crypto assets, raising questions among regulators and some in industry. GAO was asked to review crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans.

This report examines (1) the presence of crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans, (2) the potential effects of crypto assets on participant savings, (3) how fiduciaries meet ERISA responsibilities when offering crypto assets in 401(k) plans, and (4) the extent of federal oversight of crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans.

GAO reviewed data from firms that serve 401(k) plans, forms filed by 401(k) plans, and relevant federal statutes, regulations, and guidance. GAO conducted 28 interviews with government officials, researchers, and associations of plan fiduciaries, participants, service providers, and crypto asset companies. GAO also performed a simulation analysis to estimate potential retirement savings.

What GAO Recommends

In prior work, GAO recommended DOL improve the form for fiduciary reporting on 401(k) plans (GAO-14-441). DOL improved some aspects of the form but has yet to determine what additional actions it will take. GAO also reported that Congress should consider legislation to fill federal regulatory gaps over crypto assets (GAO-23-105346). Legislation has been introduced but no bill has become law as of October 2024.

What GAO Found

Available industry data and stakeholder interviews suggest crypto assets are a small part of the 401(k) market. Crypto assets are generally private-sector digital instruments that depend primarily on encryption and distributed ledger or similar technology to conduct transactions without a central authority, such as a bank. Limited Department of Labor (DOL) data prevent systematic measurement of crypto assets in 401(k) plans. Based on available information, crypto assets are a small part of the 401(k) market. GAO identified 69 crypto asset investment options available to 401(k) participants. Participants may have multiple ways to access these options. Some may have access through their 401(k) plans’ core investment options. Participants may also have access to crypto assets outside these core options, through arrangements like self-directed brokerage windows.

GAO’s analysis of investment returns indicates crypto assets have uniquely high volatility—a measure of their riskiness to participants—and their returns can come with considerable risk. GAO’s simulation found a high allocation (20 percent) to bitcoin, the crypto asset with the longest price history, can lead to higher volatility than smaller allocations (1 and 5 percent). Further, GAO’s interviews with researchers and firms that develop crypto asset investment options indicate there is no standard approach for projecting the potential future returns of crypto assets.

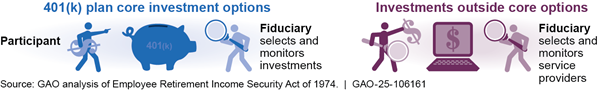

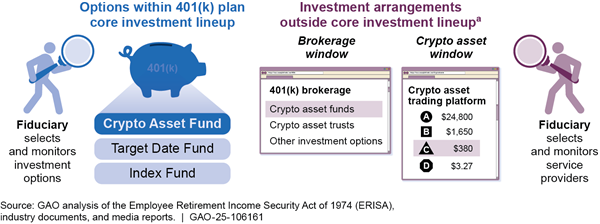

DOL guidance states that 401(k) fiduciary responsibility does not change when crypto assets are offered as investment options. ERISA requires fiduciaries to be prudent in selecting and monitoring their 401(k) plans’ core investment options, including any crypto asset investment options. DOL officials told GAO they generally had not required fiduciaries to select and monitor all options offered outside this core—for example, through self-directed brokerage windows—in accordance with ERISA’s fiduciary standards. Thus, participants who invest outside their plan’s core may have to take primary responsibility for selecting and monitoring crypto asset investment options (see figure).

401(k) Participants May Assume Greater Responsibility When Investing outside Core Investment Options

Lack of comprehensive data, along with regulatory uncertainty GAO has previously identified, limits federal oversight of participant investment in crypto assets in 401(k) plans. DOL does not have comprehensive data to identify 401(k) plans that give participants access to crypto assets. For example, the forms 401(k) plan fiduciaries file to meet federal reporting requirements do not identify crypto asset investment options in plans with fewer than 100 participants. Plans with 100 or more participants aggregate self-directed brokerage window investments, hindering DOL’s ability to isolate investments in crypto assets. Additionally, federal regulatory gaps GAO identified in June 2023 remain unaddressed. As a result, certain crypto assets continue to trade in markets that do not have investor protections or comprehensive oversight.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ATS |

Alternative Trading Systems |

|

CFTC |

Commodity Futures Trading Commission |

|

DC |

Defined Contribution |

|

DOL |

Department of Labor |

|

EBSA |

Employee Benefits Security Administration |

|

ERISA |

Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 |

|

ETP |

exchange-traded product |

|

FINRA |

Financial Industry Regulatory Authority |

|

Form 5500 Form 5500-SF |

Annual Return/Report of Employee Benefit Plan Short Form Annual Return/Report of Small Employee Benefit Plan |

|

IRR |

internal rate of return |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

OTC |

over-the-counter |

|

S&P 500 |

Standard and Poor’s 500 |

|

SEC |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

|

TDF |

target date fund |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 19, 2024

The Honorable Richard E. Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Neal:

Employer-sponsored retirement plans, such as 401(k) plans overseen by the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA), are a key source of retirement savings for older Americans.[1] DOL reported that in 2022 nearly 686,000 401(k) plans held over $6.7 trillion in total assets for more than 102 million participants.[2]

Since 2022, some firms that provide services to retirement plans have been offering options to invest in crypto assets through 401(k) plans.[3] However, EBSA and some in industry have raised concerns about risks when investing in crypto assets. In March 2022, EBSA cautioned, among other things, that crypto assets’ extreme price volatility could have a potentially devastating impact on 401(k) participants, particularly those approaching retirement and those who allocate a substantial portion of their portfolio to crypto assets.[4] EBSA cautioned fiduciaries of 401(k) plans to exercise extreme care before they consider adding crypto asset investment options.[5] Further, one of the largest providers of recordkeeping services to 401(k) plans does not offer crypto asset investment options, citing crypto assets’ speculative nature and research indicating that even a small allocation to crypto assets can substantially raise the risk profile of participants’ investment portfolios.[6] We previously reported that crypto assets and related products present significant risks and challenges—including volatility, cybersecurity, and theft risk—that may limit their potential benefits to consumers and investors.[7]

You requested that we study the prevalence, administration, and oversight of crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans. This report examines (1) the presence of crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans, (2) the potential effects of crypto asset investment options on 401(k) participant savings, (3) how fiduciaries meet their responsibilities under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) when offering crypto asset investment options to 401(k) participants, and (4) the extent to which crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans are overseen by federal regulators.

To answer all four of our objectives, we conducted 28 interviews with a range of stakeholders, including officials from DOL, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), academic and industry researchers, associations that represent 401(k) plan sponsors, participants, and industry, and individual service providers to 401(k) plans—including record keepers, investment consultants, asset managers, and attorneys. We selected interviewees to obtain a variety of perspectives on the 401(k) market. Appendix I provides more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

To address our first objective, we reviewed public, private, and proprietary sources of data on 401(k) plan investment, primary among them DOL’s Form 5500 Series.[8] To assess the reliability of DOL’s Form 5500 Series data we reviewed related documentation, obtained written responses from DOL officials about the data, and analyzed selected filings for plan year 2022.[9] We concluded these data were sufficiently reliable to report on the size of the 401(k) market, through counts of 401(k) participants, plans, and assets, but insufficiently reliable to meet our other reporting objectives.[10] We surveyed members of an industry association and obtained responses from 13 record keepers who together served a majority of 401(k) plans, participants, and assets.[11] Additionally, we obtained data from two providers of self-directed brokerage windows to 401(k) plans.[12]

To address our second objective, we performed a historical analysis and a forward-looking simulation. For our historical analysis, we obtained monthly price data from Yahoo! Finance and Investing.com for the five crypto assets identified as available for direct investment in 401(k) plans at the time of analysis: ada, bitcoin, DOT, ether, and SOL.[13] For each crypto asset, we calculated and reported performance statistics including return, volatility, and risk-adjusted return.

Next, to provide an illustrative example of the potential effects of adding various allocations of bitcoin to a standard 401(k) portfolio consisting of a target date fund (TDF), we conducted a forward-looking simulation.[14] The simulation required a variety of assumptions, including but not limited to starting account balances, annual contributions, and future bitcoin risk and return. We performed a historical analysis of bitcoin and interviewed industry and academic researchers and firms that developed crypto asset investment options to inform our simulation assumptions.[15] We included several sensitivity tests for our model assumptions including one for the TDFs used, one for the distribution of bitcoin and TDF returns, and one for rebalancing. Appendix III provides more information on our simulation analysis.

To address our third objective, we reviewed relevant federal laws and regulations. We also reviewed EBSA guidance to fiduciaries and a report to the Secretary of Labor on self-directed brokerage windows by the Advisory Council on Employee Welfare and Pension Benefit Plans, also known as the ERISA Advisory Council.[16]

To address our fourth objective, we reviewed EBSA, SEC, and CFTC guidance, EBSA enforcement priorities pertaining to crypto assets, relevant federal laws and regulations, enforcement actions, and previous GAO reports on federal enforcement efforts.[17]

We conducted this performance audit from August 2022 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

ERISA and 401(k) Plans

ERISA establishes minimum standards and requirements for most voluntarily established private employer-sponsored retirement plans, including DC plans, which allow workers to save for retirement by diverting a portion of their wages, and sometimes employer contributions, into investment accounts on which taxes are deferred.[18]

ERISA sets standards of conduct, or fiduciary responsibilities, for those who perform certain functions with respect to 401(k) plans and their assets to, among other things, act solely in the interest of plan participants and beneficiaries. Among their responsibilities, fiduciaries must act prudently in selecting and monitoring plan investment options.[19] Fiduciaries must also act prudently in selecting and monitoring service providers to the plan, including those that offer self-directed brokerage windows or similar plan arrangements enabling participants to select investments other than those in a plan’s core investment lineup.[20] Self-directed brokerage windows offer individual securities, mutual funds, exchange-traded products (ETP), grantor trusts, and other investment options.[21]

Employers that sponsor 401(k) plans for their employees typically serve as their plans’ named fiduciaries. Plan sponsors can also designate one or more people, or an office within the company, as named fiduciaries to a plan. For example, a plan sponsor could designate a company’s board of directors as a plan’s named fiduciaries.

Plan sponsors may also hire third-party service providers to help with their 401(k) plans. Some of these service providers may act in a fiduciary capacity when they make investment decisions, give advice on which investment options to offer participants, or assist with plan operations.[22] Service providers include:

· Asset managers that offer investment options. These options may be designed specifically for use in 401(k) plans’ core investment lineups, or for investors generally and offered to participants through self-directed brokerage windows.

· Record keepers that manage data on participant accounts and transactions through their administrative recordkeeping platform.

· Investment consultants that recommend or select investment options for plans.[23]

· Custodians that hold plan assets on behalf of participants, but in contrast to fiduciaries, generally do not exercise discretionary authority over these assets.

· Attorneys that advise plan fiduciaries on compliance with applicable laws, such as those under ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code, as well as with investigations and audits conducted by EBSA and IRS, respectively. They may also review contracts with service providers, assist with plan design, represent fiduciaries in connection with EBSA audits or investigations, and resolve administrative questions, such as the disposition of assets fiduciaries conclude should not be held in the plan.

Participants in 401(k) plans are often responsible for choosing how to invest contributions to their plan accounts.[24] This includes periodically rebalancing their accounts to maintain an allocation that aligns with their retirement goals and risk tolerance. For example, participants commonly invest in TDFs, which allocate assets over time based on participants’ targeted retirement dates.[25]

DOL data indicate that the market for 401(k) plans is highly concentrated, with most participants and assets concentrated in a relatively small number of larger plans. According to DOL data for 2022, 11 percent of 401(k) plans had 100 or more participants yet accounted for 88 percent of both 401(k) assets and participants, respectively. Alongside these large plans exist a greater number of smaller plans, each with fewer participants. In 2022, 89 percent of 401(k) plans had fewer than 100 participants.[26]

EBSA Oversight of 401(k) Plans

EBSA is responsible for, among other things, administering and enforcing the fiduciary and reporting and disclosure provisions of Title I of ERISA. EBSA’s national and regional office staff work together to ensure plan participants receive the health and retirement benefits to which they are entitled. The national office develops enforcement guidance regional office staff use to conduct investigations, identifies national priorities, and issues guidance to fiduciaries. Regional offices may develop their own regional projects and areas of expertise based, in part, on issues or practices prevalent in that region and the results of previous investigations.

EBSA uses the Form 5500 Series for plans to fulfill statutory duties under ERISA, as well as a primary tool to monitor and enforce plan fiduciaries’ and service providers’ ERISA responsibilities.[27] With limited exceptions, employee benefit plans subject to ERISA, including 401(k) plans, must report detailed information about the plan annually by filing Form 5500 or Form 5500-SF, as applicable.[28] The most recent versions of the forms contain multiple schedules and attachments that collect information on, among other things, plans’ investments and service provider fees.[29]

In March 2022, EBSA released guidance to plan fiduciaries that outlined the risks and challenges that investments in crypto assets pose to 401(k) accounts, such as volatility, valuation concerns, and crypto assets’ evolving regulatory environment.[30] The guidance also noted that EBSA expected to conduct an investigative program aimed at plans that offer participants crypto asset investment options.

Crypto Asset Investment Options

Crypto assets are generally private-sector digital instruments that depend primarily on encryption and distributed ledger or similar technology to conduct and record transfers of value without a central authority, such as a bank.[31] Crypto assets take a variety of forms and in some cases are referred to by the functions they are designed or intended to serve, such as:

· Cryptocurrency: generally, a digital representation of value protected through cryptographic mechanisms (instead of a central repository or authority), and typically not government-issued legal tender. Bitcoin, which emerged in 2009, is the first and most widely circulated cryptocurrency.[32]

· Stablecoin: a type of crypto asset designed with the intent to maintain a stable value, typically with reference to a fiat currency (government-issued legal tender such as the U.S. dollar) or other reference asset or assets.

Investors have multiple options for gaining exposure to crypto assets through investment, which may include:

· Direct investment in crypto assets. This refers to the purchase of crypto assets in spot (cash) markets, where financial instruments such as commodities and securities are traded for immediate exchange of another crypto asset, cash, or other financial instrument. Crypto asset trading platforms facilitate transactions in crypto assets, for example allowing users to trade one crypto asset for another, or for fiat currency. These platforms may combine the services offered by separate intermediaries in traditional financial markets, such as brokers that place orders on behalf of investors, exchanges that bring together buyers and sellers, and clearing agencies that assist in the clearing and settlement of transactions, or act as custodians that safekeep assets.

· Indirect investment in crypto asset funds, grantor trusts, and ETPs.[33] In contrast to the direct purchase of crypto assets, this refers to the purchase of units or shares of investment options that, in turn, invest in crypto assets. Alternately, these investment options may invest in crypto asset derivatives to track the price of one or more crypto assets.[34]

Oversight of Crypto Assets

CFTC and SEC have the authority to oversee certain transactions involving crypto assets, crypto asset markets, and crypto asset intermediaries.[35] However, as we have previously reported, there are gaps in the federal oversight of certain crypto assets, including stablecoin arrangements.[36]

· CFTC. CFTC has regulatory and enforcement jurisdiction over markets for commodity (nonsecurity) derivatives.[37] CFTC also has enforcement jurisdiction over spot commodities, including nonsecurity crypto assets. [38] As such, CFTC oversees crypto asset investments that involve commodity derivatives. CFTC regulation of derivatives markets focuses on protecting price and market integrity. CFTC requires registration of and regulates:

· Certain market participants who transact derivatives and intermediaries, including futures commission merchants that buy and sell them on behalf of clients.[39]

· Derivatives exchanges that provide participants in the derivatives markets the ability to execute or trade derivatives with one another.

· Derivatives clearing organizations that provide clearing services for agreements, contracts, and transactions, and act as a third party between market participants.

CFTC uses its enforcement authority to take action for apparent violations of the Commodity Exchange Act, which include, among others, fraud, market manipulation and disruption, and violations of registration and regulatory requirements.

CFTC does not directly regulate the markets for commodities underlying derivatives contracts (commodity spot markets) in the same manner that it regulates derivatives markets.[40] However, CFTC has anti-fraud and anti-manipulation enforcement authority over transactions in commodities in interstate commerce, including transactions in commodity spot markets. CFTC exercises that authority through enforcement actions.[41]

· SEC. SEC has jurisdiction over entities, persons, transactions, and other activities that involve securities, including crypto assets that are offered and sold as securities, under federal securities laws.[42] When assets, including crypto assets, meet the definition of securities under federal securities laws, their offer and sale must be registered with SEC before they can be offered and sold in interstate commerce, unless there is an applicable exemption. Additionally, federal securities laws require registration of intermediaries and market participants involved in crypto asset securities unless an exception or exemption applies. These intermediaries include, for example, broker-dealers, investment companies, certain investment advisers, clearing agencies, and national securities exchanges.

To determine whether an activity is subject to federal securities laws and SEC jurisdiction, there must be a determination of whether the activity involves an asset that was offered and sold as a security. Federal securities laws define the term security to include an investment contract, among other instruments.[43] The U.S. Supreme Court’s Howey test, along with subsequent case law, is used to determine if the offer and sale of an asset is the offer and sale of an investment contract.[44]

States may also play a role in oversight of crypto assets and custody, but laws vary significantly across states. For instance, some states that require licensure or registration as a money transmitter or money services business extend these requirements to entities conducting crypto asset transactions in certain circumstances. On the other hand, some states may require a virtual currency license or similar licensure that directly regulates delineated crypto asset–related activities. Furthermore, other states may not require any sort of licensure or registration for crypto asset market participants. In addition, entities providing custodial services for crypto assets, among other services, may apply to be chartered in a state that allows nonbanks to provide these services without federal deposit insurance.

Available Industry Data and Stakeholder Interviews Suggest Crypto Assets Are a Small Part of the 401(k) Market

Our review indicates that crypto asset investment options are a small part of the 401(k) market. However, we could not systematically measure their prevalence in 401(k) plans due to limitations we identified in the Form 5500 Series, some of which we previously recommended DOL address.[45] Appendix II provides details on these limitations.

Despite limitations in Form 5500 Series data, industry data we were able to obtain indicate investment in crypto assets and their derivatives has been minimal, relative to the overall market for 401(k) plans. For example, our survey of 401(k) plan record keepers, while not generalizable, showed minimal participant investment in crypto assets and their derivatives (see table 1). Record keepers who responded to our survey with data on use of crypto asset investment options by plans and participants reported that none of the plans they served offered crypto asset investment options on their core investment lineups. Nor did the plans they served offer participants direct investment in crypto assets through links, or windows, to crypto asset trading platforms. Record keepers reported minimal participant investment in crypto asset investment options purchased through self-directed brokerage windows. This investment amounted to substantially less than 1 percent of the 401(k) market, whether measured by plans, participants, or assets.[46]

Table 1: Selected Results from Survey of Record Keepers about 401(k) Crypto Asset Investment Options

|

|

Core investment lineupa |

Window to crypto asset trading platformb |

Self-directed brokerage windowc |

|

Use of crypto asset investment options as measured in: Number of plans/percent of total 401(k) plans in 2022 Number of participants/percent of total 401(k) participants in 2022 Amount invested ($, millions)/percent of total 401(k) assets in 2022 |

0/0% 0/0% $0/0% |

0/0% 0/0% $0/0% |

375/0.055% 3,418/0.003% $66.3/0.001% |

Source: Survey of Society of Professional Asset Managers and Recordkeepers Institute members and DOL documents. | GAO‑25‑106161

Note: Record keepers manage data on participant accounts and transactions for 401(k) plans. GAO and the Society of Professional Asset Managers and Recordkeepers Institute fielded the survey between July 20 and September 13, 2023. The results of the survey cannot be generalized to the whole 401(k) market. This is in part because we did not receive responses from all 28 record keepers that could have responded. Further, we did not determine how representative the surveyed record keepers were of all record keepers serving 401(k) plans. Thirteen record keepers provided at least one response to the survey. In combination, the thirteen record keepers reported serving 55 percent of all 401(k) plans, 52 percent of all 401(k) participants, and 65 percent of all 401(k) assets, based on totals the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) reported for 2022. See U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration, Private Pension Plan Bulletin, Abstract of 2022 Form 5500 Annual Reports, Data Extracted on 7/8/2024, Version 1.0 (Sept. 2024).

aTwelve record keepers responded with data on core investment lineups. The record keepers’ combined market share was commensurate with approximately 51 percent of plans, 29 percent of participants, and 27 percent of assets EBSA reported for the total 401(k) market in 2022.

bTwelve record keepers responded with data on links, or windows, to crypto asset trading platforms. The record keepers’ combined market share was commensurate with approximately 54 percent of plans, 49 percent of participants, and 62 percent of assets EBSA reported for the total 401(k) market in 2022.

cEight record keepers responded with data on self-directed brokerage windows. The record keepers’ combined market share was commensurate with approximately 36 percent of plans, 20 percent of participants, and 16 percent of assets EBSA reported for the total 401(k) market in 2022.

In addition to our nongeneralizable survey of record keepers, providers of self-directed brokerage windows to most 401(k) and other retirement plans with whom we spoke confirmed that investment in crypto asset investment options on their platforms was minimal. For example, in February 2024, representatives of one provider told us that combined investment in 53 crypto asset investment options we identified represented less than 0.1 percent of total assets in the plans in which these investments were made.[47] Representatives of another provider told us investment in these options totaled less than 1 percent of total retirement plan assets invested through their self-directed brokerage window.

Corroborating our review of industry data, a range of agency officials, industry representatives, and other stakeholders indicated that use of crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans was minimal.

· EBSA officials told us that based on their investigations and interactions with industry and plan stakeholders, 401(k) plans had generally not adopted crypto asset investment options. Officials observed that overall plan exposure to these investments had been minimal.

· Leaders of associations that represent 401(k) plans and their service providers—including asset managers, record keepers, investment consultants, and attorneys, as well as plan sponsors and other fiduciaries—told us that the majority of their members were not currently providing or interested in providing crypto asset investment options.

· Representatives of individual service providers we spoke with—including investment consultants, attorneys, self-directed brokerage window providers, record keepers, and a representative of a firm that interacts with an array of providers to analyze retirement markets—told us they had seen little interest in crypto asset investment options for 401(k) plans.

· Asset managers that offer crypto asset investment options to 401(k) plans and representatives of crypto asset associations we spoke with cited interest in these investment options, generally among younger participants who worked with or were familiar with crypto assets and other emerging technologies. However, representatives of both crypto asset associations and others we interviewed pointed to regulatory uncertainty as potentially affecting demand for crypto asset investment options in 401(k) plans. Relatedly, interviewees cited fiduciaries’ concerns about participant lawsuits as potentially limiting use.

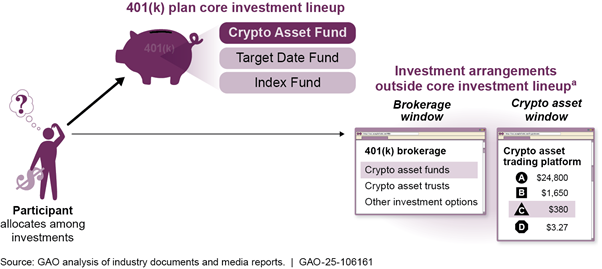

While our review showed low use in 401(k) plans, we identified 69 crypto asset investment options available to 401(k) plans. In marketing to 401(k) plans, service providers identified multiple ways for fiduciaries to offer various options to participants (see fig. 1). EBSA officials told us that despite how crypto asset investment options were marketed, fiduciaries were responsible for determining whether such options should have been included in their plan’s core investment lineup or offered through an investment arrangement apart from the lineup.

Note: Target Date Funds allocate assets over time based on participants’ targeted retirement dates. Index funds are passive funds that seek to replicate the performance of a market index instead of outperform it. Self-directed brokerage windows, referred to by a variety of names, including brokerage accounts and brokerage windows, are arrangements under which 401(k) participants may select investments beyond those designated by plan fiduciaries. Crypto assets are generally private-sector digital instruments that depend primarily on encryption and distributed ledger or similar technology to conduct and record transfers of value without a central authority, such as a bank. Crypto asset trading platforms facilitate transactions and allow users to trade one crypto asset for another, or for fiat currency (government-issued legal tender such as the U.S. dollar). Trusts are entities that create a fiduciary relationship between grantors, who generally own the assets initially contributed to the trust, and investors, who are entitled to receive benefits from the trust, such as investment returns.

aService providers described self-directed brokerage windows and crypto asset windows as offering investment arrangements apart from 401(k) plans’ core investment lineups. However, officials from the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefits Security Administration told GAO that fiduciaries are responsible for deciding whether features such as self-directed brokerage windows and crypto asset windows, or any of the crypto asset investment options they offer, should be included in plans’ core investment lineups.

Available only on the core investment lineup. We identified one crypto asset investment option that is available solely for use in 401(k) plan core investment lineups.[48] This option is a unitized fund that primarily holds bitcoin along with other short-term investments for liquidity.[49] The provider establishes a separate account within each 401(k) plan that adopts this option. Participants invest in units of their plans’ separate accounts. The provider of this option told us plan fiduciaries are responsible for setting limits on the proportion of contributions and savings participants can allocate to this option, up to 20 percent of their account balance.

One of the larger 401(k) service providers supports this crypto asset unitized fund by providing recordkeeping, trading, and custodial support through affiliates. The provider incorporates features common to other investment options in 401(k) plans. For example, although bitcoin trades continuously, participant orders to buy or sell units of this option are processed once daily, based on a closing price referred to as the net asset value. This is similar to the way other assets commonly offered in 401(k) plans, such as shares of mutual funds, are priced. To do this, each business day the net asset value is generally calculated based on the value of the bitcoin (using a publicly available bitcoin index as reference) and the short-term investments held in the account.[50]

Available through windows to crypto asset trading platforms. We identified another, substantially smaller, 401(k) service provider that offers a window to a crypto asset trading platform.[51] In contrast to the other options we identified, the crypto asset window gives participants access to spot markets for crypto assets in which participants invest directly in crypto assets, as opposed to in units or shares of funds or trusts. The crypto asset window offers direct investment in six crypto assets, including one stablecoin.[52]

The provider of this crypto asset window described it as an arrangement selected by plan fiduciaries that enables participants to invest outside a 401(k) plan’s core investment lineup. According to the provider, this has the benefit of emphasizing that investments made through the crypto asset window are voluntary, which participants acknowledge when they take the extra step of signing up for the window.[53] The provider contrasted this with including crypto asset investment options in a 401(k) plan’s core investment lineup, which the provider said could expose fiduciaries to the risk of liability in the event an investment option is determined to be imprudent. The provider also cited the imposition of limits on allocations and contributions made through the crypto asset window as a tool fiduciaries could use to reduce risks to participants. Fiduciaries that adopt this option are responsible for setting limits of up to 5 percent on allocations and contributions made through the window.[54]

As noted previously, EBSA officials told us fiduciaries were responsible for determining whether features such as crypto asset windows were most prudently adopted for their plans’ core investment lineups or as investment arrangements apart from their core lineups. In its guidance to fiduciaries on crypto assets, EBSA said fiduciaries should be prepared to support how their decision to adopt such features, either as part of the lineup or apart from it, met fiduciary requirements under ERISA.[55] We discuss these requirements later in the report.

Available through self-directed brokerage windows. We identified 62 crypto asset investment options that provided indirect exposure to crypto assets and could be made available to participants through self-directed brokerage windows as of October 2024. In January 2024, SEC approved applications for spot bitcoin ETPs to trade on U.S. exchanges. SEC subsequently approved applications for spot ether ETPs, which began trading in July 2024.[56] Executives from two asset managers that offer crypto asset investment options told us these approvals would lead to lower fees for investment options that provide indirect exposure to crypto assets. As table 2 shows, ETPs that invest directly in bitcoin and ether through spot markets had lower median annual fees than other types of crypto asset investment options, including ETPs that invest in crypto asset derivatives, such as futures contracts.

Table 2: Crypto Asset Investment Options Available from Providers of 401(k) Self-Directed Brokerage Windows That GAO Identified

|

Investment type |

Number of options |

Invests in |

Exchange(s)a |

Annual fees |

|

Exchange-Traded products (ETP) |

21 |

bitcoin or ether |

Cboe BZX Exchange, Inc. The Nasdaq Stock Market NYSE Arca, Inc. |

0.15–2.5 percent, 0.25 percentc |

|

20 |

Derivatives of bitcoin, ether, or both |

0.65–1.85, 0.95 |

||

|

Mutual funds |

3 |

Derivatives of bitcoin |

N/Ad |

1.15–2.5, 1.26 |

|

Index funds |

2 |

Multiple crypto assetse |

OTC Markets Group |

2.5, 2.5 |

|

Trusts |

16 |

Multiple crypto assetsf |

OTC Markets Group |

0.49–2.5, 2.5g |

Source: Filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), documents from the Department of Labor, media reports, and industry documents. | GAO‑25‑106161

Note: GAO previously analyzed Morningstar fee data for Target Date Funds (TDF), the most popular investment option used by 401(k) participants. As compared to the crypto asset investment options we identified, TDF mutual funds had annual net expense ratios ranging from 0.08 to 0.78 percent, with a 2022 average asset-weighted net expense ratio of 0.32 percent. Expense ratios are a measure of fees, showing an investment’s total operating expenses as a percentage of its assets. GAO, 401(k) Plans: Department of Labor Should Update Reporting Requirements and Guidance on Target Date Funds, GAO‑24‑105364 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2024). Our prior work also shows that even seemingly small differences in fees, such as an annual 1 percent charge, can significantly reduce the amount of money saved for retirement. GAO, Private Pensions: Changes Needed to Provide 401(k) Plan Participants and the Department of Labor Better Information on Fees, GAO‑07‑21 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2006).

aCboe BZX Exchange, Inc., the Nasdaq Stock Market, and NYSE Arca, Inc. are national securities exchanges. Over-the-counter (OTC) markets operated by OTC Markets Group are networks of broker-dealers where securities that often do not meet the requirements to be listed on a national exchange can trade.

bExcept as noted below with respect to temporary fee waivers, we report net fees when asset managers listed both gross and net fees for investment options. Net fees may be contingent on the asset manager applying fee waivers.

cIn January 2024, SEC approved 10 ETPs that invest in bitcoin. One of these options was previously available through OTC Markets Group. The annual fee for this option decreased from 2 percent to 1.5 percent when its asset manager received approval to list shares of their crypto asset trust on an exchange as an ETP. The other nine options had lower annual fees, ranging from 0.19 to 0.39 percent. Asset managers for eight of the nine bitcoin ETPs further offered temporary waivers of any annual fees in marketing these options. SEC subsequently approved nine ether ETPs, which began trading in July 2024. As with the bitcoin ETPs, one of the ether ETPs had higher annual fees than the others. The asset manager similarly received approval to list shares of this previously available option that invested in ether as an ETP on NYSE Arca, Inc. The asset manager for this option retained its 2.5 percent annual fee. The other eight ether ETPs had comparatively lower annual fees, ranging from 0.15 to 0.25 percent.

dShares of mutual funds do not trade on exchanges. Instead, investors purchase and redeem shares through the funds directly, or an intermediary such as a broker-dealer.

eIn SEC filings, the asset manager of these two options described them as Limited Liability Companies incorporated in the Cayman Islands. The asset manager also stated that these two options were not registered investment companies under the Investment Company Act of 1940. Between them, the two index funds invested in 11 crypto assets.

fFifteen of the trusts invest in a single crypto asset each. In SEC filings, asset managers described these options as grantor trusts, which are entities established and governed under state law. Grantor trusts create a fiduciary relationship between asset managers, who serve as grantors, and investors, who serve as beneficiaries. The other trust invested in multiple crypto assets to track the performance of an index. In SEC filings, the asset manager described this option as a statutory trust organized under Delaware law and anticipated that for federal tax purposes it would not be classified as a grantor trust, because it would not hold a fixed pool of assets. Between them, the trusts invested in 17 crypto assets.

gAll but one of the crypto asset trusts had annual fees of 2.5 percent.

Asset managers we spoke with cited further advantages of ETPs that invested in crypto assets over the crypto asset investment options available prior to January 2024. Specifically, although the crypto asset trusts we identified as available through OTC markets invest directly in crypto assets, they have limited redemption features. This means that although investors are allowed to sell their shares on OTC markets, they cannot redeem shares with the asset manager in exchange for the underlying crypto asset. Asset managers told us this limitation could contribute to premiums or discounts between market price and net asset value—meaning the unit price of the investment option would diverge from the price of the underlying crypto asset. Further, they told us investment options that tracked the price of crypto assets by purchasing futures contracts based on them might experience increased or decreased returns, caused by differences between the value of the crypto assets and their futures contracts, as well as the need to purchase new futures contracts as the old ones expire.[57]

Fiduciaries of 401(k) plans can and do limit the offerings available through self-directed brokerage windows but may face challenges limiting participant access to crypto asset investment options. For example, industry data from a 2021 report on self-directed brokerage windows indicate that between 15 and 20 percent of DC retirement plans restrict self-directed brokerage window offerings to mutual funds.[58] However, this broad limitation would not fully restrict access to the crypto asset investment options we identified, three of which were mutual funds. Further, representatives of a self-directed brokerage window provider for 401(k) plans told us they did not offer plans a categorical restriction on crypto asset investment options available on their platform. The representatives told us this is because they could not be sure what investments did or did not qualify under EBSA’s guidance as crypto asset investment options. They said fiduciaries could, however, further restrict specific investment options from a self-directed brokerage window if the fiduciaries identified options that invested in crypto assets or their derivatives.

Future Crypto Asset Investment Returns are Highly Uncertain and Could Have Significant Wide-Ranging Effects on 401(k) Participant Savings

Crypto Assets Available to 401(k) Participants Are an Emerging Group of Assets with No Standard for Long-Run Evaluation

|

What does standard deviation mean for investments? Standard deviation is a measure of volatility. Volatility is the uncertainty or risk related to an investment’s return. A higher standard deviation means higher riskiness because there could be large upward or downward swings in investment return. For example, an investment with a lower standard deviation, or risk, could have a positive return of 5 percent or a negative return of 5 percent in an average year. On the other hand, an investment with a higher standard deviation could have a positive return of 20 percent or a negative return of 20 percent in an average year. Among two investments with the same expected return, the investment with the lower standard deviation (risk) is generally preferred by investors. Source: Industry documentation. | GAO‑25‑106161 |

A primary risk of crypto assets we reviewed is that they mainly derive their value from investor sentiment rather than through tangible company assets or cash flows. Officials from DOL pointed out that unlike traditional stocks, investors in crypto assets typically do not own blockchain technology and generally do not have an entitlement to income streams from investment in the same way that holders of stocks have rights to dividends from an operating company. Additionally, some industry stakeholders and researchers we interviewed told us that, unlike traditional commodities, crypto assets do not have a well defined use case or a fundamental driver of value beyond supply and demand.[59] For example, while individuals value gold as jewelry and as a store of value, gold is also used for its conductive and corrosion resistant properties in other industries. If market sentiment shifts to a new crypto asset, older crypto assets could become obsolete and lose their value.

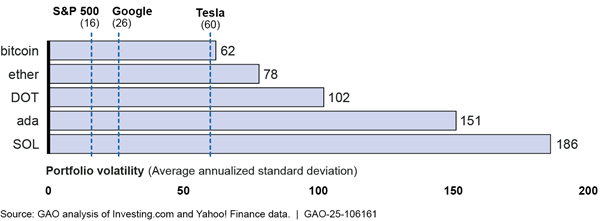

Another risk of crypto assets available for direct investment in 401(k) plans is their uniquely high volatility.[60] Volatility is a measure of riskiness, and high volatility means there could be large upward or downward swings in investment returns.[61] Figure 2 displays the volatility, as measured by the standard deviation of returns, for five crypto assets available for investment in 401(k) plans for the years 2021 to 2023.[62] Volatility for these crypto assets ranged from four times to 12 times greater than the volatility of the Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500), which tracks the performance of the 500 largest publicly traded companies in the United States.[63] Compared to individual stocks, crypto asset volatility ranged from around two to seven times greater than the volatility of Google or Apple stock.[64] Crypto asset volatility ranged from around the same to approximately three times larger than Tesla, a newer company that is also among the top equity holdings of retirement plan participants.

Figure 2: Average Annualized Standard Deviation of Crypto Asset Returns Currently Available for Investment in 401(k) Plans from 2021 to 2023

Note: Standard deviation is a measure of volatility, and a higher standard deviation means more volatility in portfolio returns. Standard deviations are given as a return percentage. A portfolio with a high standard deviation means there could be large upward or downward swings in investment returns. The Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) tracks the performance of the 500 largest publicly traded companies in the United States. Ada, bitcoin, DOT, ether, and SOL are crypto assets that were available for direct investment in 401(k) plans at the time of analysis.

For the crypto assets we analyzed from 2011 to 2023, volatility has generally been higher earlier in these crypto assets’ lifetimes. For example, from 2021 to 2023, the three newest crypto assets experienced the highest volatility and bitcoin had the lowest volatility, as shown in figure 2. In bitcoin’s early years, it had volatility even greater than that of the newer crypto assets, at 26 times greater than that of the S&P 500.[65] Bitcoin is the first-developed crypto asset with the longest history, but it still had volatility four times greater than the S&P 500 more than a decade after its inception.

Outside of crypto assets’ risks, our interviews with stakeholders, including industry and academic researchers, and our quantitative analysis did not find any one group of assets as being directly comparable to crypto assets.[66] For example, nine of 17 interviewees stated crypto assets were not directly comparable to any other group of assets, while 10 interviewees listed assets that had some traits similar to crypto assets, including commodities, venture capital, and emerging markets, among others. Commodities follow a shortage cycle, venture capital funds have high volatility and the potential for high returns, and emerging market investments have a significant potential to lose their value, as one interviewee described. Crypto assets are further distinguished from other assets because their treatment under existing law varies depending on their unique facts and circumstances and will differ depending on, for example, if they are offered and sold as commodities, securities, or something else.

Crypto assets’ role in retirement portfolios and impact on portfolio diversification is also unclear, according to our interviews with industry stakeholders and researchers. A portfolio diversifier is an asset that is not strongly positively correlated with the other assets in a portfolio.[67] Portfolio diversification is a key risk mitigation practice in managing investment portfolios, including retirement portfolios. Portfolio diversification seeks to minimize risk while also maximizing return on the entire portfolio. Over crypto assets’ brief history, their correlation with traditional financial markets (stock and bonds) has been low. However, our interviews with industry stakeholders, researchers, and firms that develop crypto asset investment options indicate that the correlations have risen over time, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.[68]

When compared to gold—an asset sometimes used to diversify investment portfolios—all five crypto assets we reviewed had higher correlations with the S&P 500 than gold did in most years since their inception. Correlations with traditional financial markets that are higher than those of other portfolio diversifiers potentially reduce the role of crypto assets as portfolio diversifiers. Additionally, since crypto assets present volatile returns, a higher correlation between crypto assets and traditional investments could introduce larger losses to a portfolio during market downturns.

Our analysis indicates crypto assets’ high potential returns can come with considerable risks. Specifically, our historical analysis covering five crypto assets available for direct investment in 401(k) plans for the years 2011 to 2023, indicated that most of these crypto assets experienced much higher returns for most of their lifetime relative to the S&P 500, gold, Apple, Google (Alphabet), and Amazon. However, to understand the trade-off between the risk and return of an investment in these five crypto assets, we calculated risk-adjusted returns. Risk-adjusted returns compare the return of an investment with the additional risk that investment brings.[69] Over each of these crypto assets’ brief history, the risk-adjusted returns have been negative in a few years, but have been generally higher than the S&P 500.[70] Risk-adjusted returns provide a convenient way to capture both risk and return in one number, but they are not a one-size-fits-all performance measure. A participant’s actual risk tolerance may be higher or lower than what is implicit in risk-adjusted return metrics.

Further, through our interviews with industry and academic researchers and firms that develop crypto asset investment options among others, we found there is no standard approach for projecting potential future returns of crypto assets as long-term investments.[71] Interviewees listed some mathematical and statistical models as potential options but cite crypto assets’ short and volatile history relative to traditional assets and uncertain regulatory environment as challenges for these approaches.

Short term historical analyses have been another common approach for evaluating the potential effects of crypto assets’ future investment performance on investment portfolios, according to our interviews with industry researchers and firms that develop crypto asset investment options, among others. In some of these analyses, researchers compare a portfolio’s historical performance to what the portfolio’s performance would have been if it had an investment in a crypto asset. However, past performance and risk cannot consistently predict future performance and risk, especially among novel assets like crypto assets. As a result, these analyses may have limitations for evaluating the potential effect of crypto assets in the long run.

Our findings cover five crypto assets available for direct investment in 401(k) plans at the time of analysis, but there is wide variability across crypto assets in their performance, purpose, and other characteristics. For example, out of the estimated 24,000 crypto assets listed on an independent crypto asset data aggregator since 2014, more than half no longer existed in 2023.[72] In addition, our historical analysis evaluates the performance and risk of crypto assets until 2023, the latest complete year of data available at the time of our analysis. However, the crypto asset landscape is ever changing, including the collapse of certain crypto asset trading platforms, SEC’s 2024 approval of the listing and trading of spot bitcoin ETPs, and ongoing litigation brought by SEC alleging certain offers and sales of crypto assets were not registered under federal securities law or made pursuant to a valid exemption, and certain crypto asset intermediaries are operating in an unregistered capacity.[73]

Bitcoin Investment in a 401(k) Plan Could Lead to Significant Variability in Investment Returns

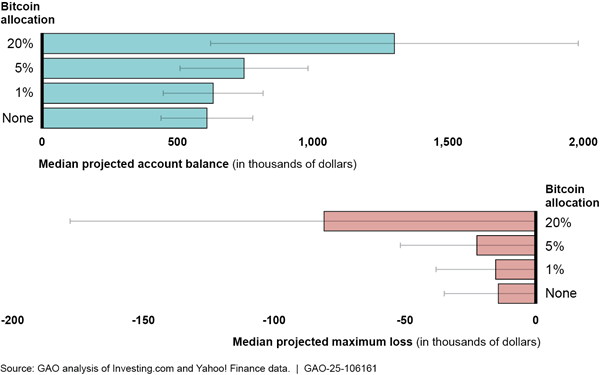

Using a simulation technique to estimate the potential effects of adding varying amounts of bitcoin to an illustrative 401(k) portfolio, we found high portfolio allocations to bitcoin lead to lower projected risk-adjusted returns and potentially higher losses compared to little or no allocation to bitcoin.[74] The simulation enables us to describe a range of potential outcomes that can occur under different assumptions and scenarios.[75] This is particularly useful when there is a high degree of uncertainty, as is the case with bitcoin. However, simulation results rely heavily on the characteristics of the underlying assumptions.[76]

Our simulation assumptions are based on historical risk and returns as well as the potential risks and returns of bitcoin, informed by opinions from industry and academic researchers and firms that develop crypto asset investment options. We used bitcoin for the simulation because as the first crypto asset, it had the longest price history. For a risky and novel asset like bitcoin, historical risks and returns alone will not provide a complete picture of potential future risks and returns. For example, from 2011 to 2023, bitcoin annual returns ranged from -73 percent to 5,870 percent compared with -50 percent to 118 percent for Amazon.[77] Our simulation of 401(k) balances requires us to make various model assumptions, such as mean returns, volatilities, correlations, starting account balances, and cash flows into and out of the account.[78] One such assumption for the portfolio we report on is that bitcoin would have near-term returns and volatility similar to its recent history, but long-run returns and volatility similar to that of gold.[79]

Our primary finding, that large allocations of bitcoin lead to significant variability in risk and return, is not sensitive to changes in our assumptions. We report our findings for a mid-career participant relative to an illustrative 401(k) portfolio with no investment in bitcoin and refer to this portfolio as our baseline portfolio. For more information about the simulation assumptions and sensitivity analyses, see appendix III.

In our simulation, any allocation to bitcoin increases portfolio risk, but risk-adjusted returns can be marginally higher than the baseline portfolio for lower allocations to bitcoin. The projected volatility and maximum loss are worse with any allocation to bitcoin relative to the baseline portfolio.[80] However, even small allocations to bitcoin increase the projected median annual return, as measured by the internal rate of return of the portfolio.[81]

To aid in understanding how the added risk relates to the added return, we calculate risk-adjusted returns.[82] In our simulation, the risk-adjusted return for a mid-career participant is marginally better for low allocations to bitcoin and worse for high allocations to bitcoin relative to the baseline portfolio. That is, our simulation indicates the return gained from a small investment in bitcoin provides some compensation for the additional volatility, but this is not the case for high allocations. While small allocations of bitcoin yield marginally better risk-adjusted returns, the simulation assumes the portfolio’s bitcoin allocation is held, and annually rebalanced, consistently for 20 years. However, holding a volatile asset like bitcoin during downturns may be difficult for investors.[83] Additionally, as investors approach retirement, holding a large allocation of bitcoin puts them at a higher risk of losing savings without much time to recover.

In the long term, our simulation indicates large portfolio allocations to bitcoin are associated with better median internal rates of return and account balances, but also higher risk. The simulation projects low allocations of bitcoin could lead to median account balances and internal rates of return that are marginally higher than a 401(k) portfolio without bitcoin, after 20 years.[84] Meanwhile, a portfolio with a 20 percent allocation to bitcoin could significantly increase the projected median account balance (see fig. 3) and almost doubles the median internal rate of return.[85] Additionally, higher projected median account balances for high allocations of bitcoin come with additional risks. Portfolios with a 20 percent allocation to bitcoin are projected to have maximum losses over five times as high as the baseline portfolio (see fig. 3), have volatility over twice as high as the baseline portfolio, and have risk-adjusted returns 28 percent lower than the baseline portfolio.

Figure 3: Projected Median Account Balance and Projected Median Maximum Loss of a Simulated Illustrative 401(k) Portfolio with Different Allocations to Bitcoin after 20 Years

Note: Figure represents the median of 10,000 projected portfolio returns for a mid-career participant after a 20-year investment, assuming bitcoin returns have long run return and volatility similar to gold. Maximum loss, also known as maximum drawdown, is a measure of downside risk, and a high maximum loss means a larger down movement. The lines represent the standard deviations of the simulated results. Our analysis does not constitute and should not be viewed as a definitive method of evaluating the long-term effect of crypto assets.

Risks of investing in crypto assets are exacerbated without annual portfolio rebalancing, especially for large allocations to bitcoin. Rebalancing is the practice of periodically adjusting your asset allocation to maintain your target asset allocation. Rebalancing may reduce risk exposure, particularly for portfolios that include volatile assets. Our simulation assumes the portfolio is rebalanced annually.[86] To investigate the influence that annual rebalancing has on our findings, we performed a sensitivity check with no rebalancing. Not rebalancing a portfolio can lead to very large projected ending account balances compared to annual rebalancing. However, not rebalancing can reduce the median projected internal rate of return and risk-adjusted returns.

The risks of not rebalancing are particularly acute for large allocations to bitcoin. For example, for large allocations to bitcoin with no portfolio rebalancing, the median projected internal rate of return is almost half as high as a portfolio with annual rebalancing. Further, a portfolio without rebalancing has nearly double the projected median volatility and over triple the projected maximum loss for large allocations of bitcoin. Importantly, for most investments, rebalancing relies on investor action and is uncommon among most investors in nonmanaged accounts.[87]

Our analysis does not constitute, nor should it be viewed as, a definitive method of evaluating the long-term effect of crypto assets. The simulation should be interpreted carefully, as our approach was not designed to provide precise predictions. Our simulation is based on the historical and potential risks and returns of bitcoin and therefore does not apply to crypto assets generally. Crypto asset returns in general will be lower than crypto asset returns of surviving assets. Many elements can influence the future return of bitcoin, including but not limited to the regulatory environment, investor sentiment, and technological advancement. This analysis assumes these current market conditions will continue in the future and bitcoin is readily available for trading. We previously reported crypto assets and related products presented significant risks and challenges—including volatility, cybersecurity, and theft risk—that might limit their potential benefits to investors.[88] The simulation does not attempt to model the risk of a complete loss in bitcoin investment resulting from these potential risks. Returns would likely be lower if these risks were included in the model. Additionally, this analysis does not take into account externalities of crypto assets, such as strains to the electric grid, which could lower the social benefit of owning bitcoin.[89] See appendix III for more information regarding the analysis.

Fiduciaries Offering Crypto Assets Must Meet ERISA Requirements with Respect to 401(k) Investment Options, Providers, and Transactions

ERISA Requires Fiduciaries to Select and Monitor the Investment Options Offered in a 401(k) Plan Core Investment Lineup

When selecting 401(k) plan core investment options, ERISA requires fiduciaries to consider whether a particular investment in the plan’s lineup is reasonably designed with respect to the risk of loss versus the opportunity for gain.[90] In its Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01, EBSA stated that a 401(k) fiduciary’s consideration of whether to include an option for participants to invest in crypto assets remained subject to ERISA’s exacting fiduciary responsibilities. EBSA officials told us the agency did not maintain separate regulatory regimes for different types of assets. Fiduciaries are responsible for overseeing the selection and monitoring of each option within the lineup, with appropriate considerations regarding, among other things, risk, potential returns, and reasonableness of fees for each option. In addition, ERISA requires fiduciaries to avoid prohibited transactions associated with assets in 401(k) plans, regardless of whether crypto assets are offered as investment options.[91]

Also in its Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01, EBSA cautioned plan fiduciaries to exercise extreme care before adding a crypto asset option to a 401(k) plan’s core investment lineup. Reasons for caution included investment volatility, custodian and recordkeeping concerns, and valuation concerns. Several of the stakeholders we interviewed told us that EBSA’s caution was appropriate given that crypto assets were an emerging asset type. For instance, a lead executive of a national association of investment consultants to retirement plans said EBSA’s guidance was well timed and effectively informed fiduciaries about the potential risks associated with crypto asset investment. Representatives of a plan sponsor association told us Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01 did not set a higher fiduciary responsibility threshold for crypto assets versus other investment options. They found the release appropriate and compared it to when EBSA published guidance in the past when mutual funds were being introduced as 401(k) investment options under ERISA.

The simulation we presented earlier demonstrates that investment return for crypto asset investment options may be volatile and that there can be tradeoffs between risk and return. Balancing the two may be difficult for fiduciaries, in part, because, as EBSA states in Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01, there exist many uncertainties associated with valuing crypto assets. This lack of clarity could add to the complexity of decisions fiduciaries need to make to meet ERISA requirements when offering crypto asset investment options. For example:

· Fiduciaries who add a crypto asset investment option might consider how it adheres to provisions under ERISA that allow fiduciaries to limit their liabilities if their core investment lineup meets certain conditions.[92] Officials of an organization that represents large 401(k) plans told us this could be a particular challenge for fiduciaries since they would need to justify that a single-asset investment option met these ERISA provisions.[93]

· Additionally, as we reported earlier, although crypto assets could be seen as potential portfolio diversifiers, their rising correlation with traditional financial market assets potentially reduced their benefit as diversifiers. An attorney we interviewed said plan sponsors should educate themselves on any new asset type they wanted to add to a 401(k) lineup if they did not already have expertise on that asset type. In its Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01, EBSA stated that “it can be extraordinarily difficult, even for expert investors,” to evaluate crypto assets, underscoring the need for sponsors to become educated on crypto assets, as well as the markets and intermediaries involved in trading those assets, prior to adding them to their core lineup.

· Finally, ERISA requires fiduciaries to consider the appropriateness of crypto asset trading platforms as service providers to crypto asset investment options included in 401(k) plan core investment lineups. For example, the crypto asset investment option we identified as designed solely for core investment lineups makes use of multiple crypto asset trading platforms to seek best pricing, among other things.

We have previously reported that crypto asset trading platforms have yet to realize their potential to produce cost savings and other financial benefits, and they have also negatively affected consumers and investors.[94]

We have also reported that some platforms might be susceptible to illicit trading practices.[95] Several federal government agencies, international bodies, and researchers, have expressed similar concerns about vulnerabilities associated with the trading of crypto assets.[96] In June, 2023, SEC filed an enforcement action against a platform that acts as a service provider to crypto asset investment options we identified for, among other alleged activity, carrying out the functions of a broker, exchange, and clearing agency without registering each with SEC.[97]

ERISA Requires Fiduciaries to Select and Monitor Providers Who Offer Investment Options outside of 401(k) Plan Core Investment Lineups

Unlike for investment options within a core lineup where fiduciaries are required to select and monitor the options, for investment options outside a core lineup, plans select service providers to make investment options available to participants, through investment arrangements such as self-directed brokerage windows. ERISA requires fiduciaries to prudently select and monitor 401(k) plan providers, including those who provide services associated with self-directed brokerage windows or similar plan arrangements, before selecting a provider (see fig. 4).[98] Many of the crypto asset investment options we identified are offered on at least one of two prominent self-directed brokerage window platforms available to 401(k) plans.[99] In addition, as with options offered within a plan’s core investment lineup, fiduciaries must avoid prohibited transactions with respect to service providers when offering when offering self-directed brokerage windows or similar plan arrangements.

Figure 4: Fiduciary Responsibilities under ERISA for 401(k) Investment Options within and outside a Core Investment Lineup

Note: Target Date Funds allocate assets over time based on participants’ targeted retirement dates. Index funds are passive funds that seek to replicate the performance of a market index instead of outperform it. Self-directed brokerage windows, referred to by a variety of names, including brokerage accounts and brokerage windows, are arrangements under which 401(k) participants may select investments beyond those designated by plan fiduciaries. Crypto assets are generally private-sector digital instruments that depend primarily on encryption and distributed ledger or similar technology to conduct and record transfers of value without a central authority, such as a bank. Crypto asset trading platforms facilitate transactions and allow users to trade one crypto asset for another, or for fiat currency (government-issued legal tender such as the U.S. dollar). Trusts are entities that create a fiduciary relationship between grantors, who generally own the assets initially contributed to the trust, and investors, who are entitled to receive benefits from the trust, such as investment returns.

aService providers described self-directed brokerage windows and crypto asset windows as offering investment arrangements apart from 401(k) plans’ core investment lineups. However, officials from the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefits Security Administration told GAO that fiduciaries were responsible for deciding whether features such as self-directed brokerage windows and crypto asset windows, or any of the crypto asset investment options they offer, should be included in their plans’ core investment lineups.

In 2010, EBSA issued regulations that required the disclosure of certain plan and investment-related information, including fee and expense information, to participants and beneficiaries in 401(k) plans, including those that offer self-directed brokerage windows.[100] The final rule reiterated that nothing in the regulation would relieve a fiduciary of its responsibilities to prudently select and monitor providers of services to the plan or designated investment alternatives offered under the plan. In 2012, EBSA published a bulletin that stated fiduciaries of plans with self-directed brokerage windows or similar plan arrangements that enabled participants and beneficiaries to select investment beyond those designated by the plan were still bound by ERISA statutory duties of prudence and loyalty to participants. These include taking into account the nature and quality of services provided in connection with the window or arrangement.[101] In 2021, EBSA issued a publication outlining the steps fiduciaries should take to monitor service providers, including reviewing performance, policies, and practices. This 2021 publication further stated that fiduciaries should also check the fees being charged to participants and follow up on participant complaints.[102]

EBSA officials told us that, unlike requirements for core investment lineups, EBSA generally had not required fiduciaries to evaluate each investment option available to participants through self-directed brokerage windows. However, in Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01, EBSA cautioned that plan fiduciaries allowing investments through brokerage windows “should expect to be questioned about how they can square their actions with their duties of prudence and loyalty in light of the risks,” described in the compliance assistance release. Some stakeholders we interviewed told us EBSA’s guidance had been interpreted by some fiduciaries as a warning that EBSA had changed fiduciary requirements under ERISA with respect to arrangements for investing outside core 401(k) investment lineups. Industry stakeholders and associations representing service providers sent letters to EBSA expressing concerns that Compliance Assistance Release 2022-01 could potentially change fiduciary responsibilities. However, a 2023 court decision subsequently noted that the release left responsibilities under ERISA unchanged.[103]

EBSA cautioned fiduciaries to consider the extent to which crypto asset providers might be operating outside of existing regulatory frameworks or not complying with such frameworks. It cited concerns raised by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) that crypto assets had “been used in illegal activity, including drug dealing, money laundering, and other forms of illegal commerce.”[104] Agency officials and stakeholders we interviewed noted that regulation was evolving and that participants needed to use caution if they invested outside of a 401(k) plan’s core investment lineup without the fiduciary protections afforded to core lineup options. In these instances, participants could bear losses if nefarious activity negatively affects their assets.

Further, if fiduciaries typically do not evaluate each option offered through a brokerage window, participants assume greater risk for such options. For example, while fiduciaries must monitor the fees charged by a self-directed brokerage window provider (e.g., a maintenance fee or trading fees), they may not necessarily evaluate the fees charged by asset managers of investment options offered though brokerage windows.[105] As noted earlier, fees for crypto asset investment options vary widely, ranging from 0.19 to 2.50 percent annually. Also, as presented earlier, participants will need to distinguish between different types of investment options, some of which involve features that can cause price distortions. In 2024, FINRA published results of a targeted exam of crypto asset investment option disclosures. Its review of disclosures revealed instances of false and misleading statements or claims regarding crypto assets including unclear explanations of how they work and their core features and risks to participants.[106]

Data Availability and Regulatory Uncertainty Have Limited Federal Oversight of Crypto Asset Investment Options in 401(k) Plans

EBSA Lacks Data to Identify Crypto Asset Investments in 401(k) Plans and Assess Their Effects on Participant Savings

EBSA does not collect comprehensive data that would enable the agency to easily identify 401(k) plans that may offer participants access to crypto assets. Officials told us that they periodically analyzed Form 5500 filings to find plans that had crypto asset exposure. Specifically, officials told us they searched filings of larger 401(k) plans’ financial information on Form 5500 Schedule H and its attached schedule of assets for certain names of investments related to crypto assets.[107] However, as previously mentioned, there are limitations to using these filings to identify plans that invest in crypto assets. For instance, according to EBSA officials, 401(k) plans that file schedule H are not required to identify investments in assets made through self-directed brokerage windows.[108]

Furthermore, in 2014, we found limitations with the Form 5500 Series that made it difficult to gain insights into plan investments, their structure, and their level of associated risk.[109] Appendix II provides additional detail on these limitations. Our prior report recommended DOL consider revisions to the Form 5500 Series that would provide more transparency and detail into plan investments, among other things.[110] DOL has taken steps to improve Form 5500 Series reporting, but the recommendation has not been fully implemented.[111] DOL has yet to address these deficiencies, for example by revising Schedule H plan asset categories to better match current investment vehicles or creating a standard, searchable format for schedules of assets attached to filings.

DOL’s Spring 2024 semi-annual regulatory agenda includes an effort to modernize reporting requirements on the Form 5500 Series and make investment information more data minable to meet the needs of changing compliance projects, programs, and activities. This effort could address the limitations we identified in previous work.[112] As part of this effort, EBSA officials noted that they were considering previous proposals to improve the form, public comments received as part of those proposals, and other potential improvements.[113] DOL officials noted that as of May 2024, a draft notice of forms revision was under development, but a final decision had not been made on what financial transparency and data usability elements would be included. This means the rulemaking process could result in updates to the Form 5500 Series that could address limitations we have identified, such as exploring whether crypto asset investment options should be included in a list of investments that must be reported separately on attachments to Schedule H even if made through self-directed brokerage windows.[114] Officials also indicated that EBSA had been focusing its regulatory resources on the multiple regulatory, guidance, and report projects it was assigned under the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022.[115]