COVID-19 RELIEF

SBA and DOL Should Improve Processes to Identify and Recover Overpayments

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106199

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106199. For more information, contact M. Hannah Padilla at (202) 512-5683 or padillah@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106199, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

COVID-19 RELIEF

SBA and DOL Should Improve Processes to Identify and Recover Overpayments

Why GAO Did This Study

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress provided funding to assist small businesses through SBA’s PPP and COVID-19 EIDL programs. Congress also created four temporary DOL UI programs to support workers adversely affected by the pandemic. The demand for these programs and the need to deliver aid quickly increased the risk of improper payments, including overpayments. Effective post-payment control processes help agencies to identify and recover overpayments after they have occurred.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor COVID-19 pandemic relief funds. This report (1) examines the extent to which SBA and DOL have developed processes for identifying and recovering COVID-19 overpayments and (2) analyzes the success of agency efforts in recovering COVID-19 overpayments.

GAO analyzed SBA and DOL documentation regarding overpayment identification and recovery efforts, reviewed relevant laws and guidance, analyzed public datasets, and interviewed federal officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations. Three are to SBA, including that it expand and document overpayment review procedures and expand its tracking process; two are to DOL to update its recovery rate reporting and guidance. SBA partially agreed to all recommendations, and DOL disagreed with both recommendations. GAO continues to believe all recommendations are warranted.

What GAO Found

Early in the pandemic, federal agencies prioritized swiftly distributing funds and implementing new programs to help businesses and individuals adversely affected by COVID-19. While this swift response helped meet urgent needs, it involved trade-offs that put billions of dollars at increased risk for improper payments, including overpayments.

Small Business Administration (SBA) and Department of Labor (DOL) programs accounted for a large portion of COVID-19 relief funding and experienced heightened improper payment risks. SBA provided more than $1 trillion in loans and grants, primarily through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL). DOL’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program expenditures totaled about $900 billion. For fiscal year 2023, SBA reported an estimated 40.5 percent of PPP loan forgiveness and 49.2 percent of PPP guarantee purchase payments were improper. DOL estimated 35.9 percent of Pandemic Unemployment Assistance payments were improper.

SBA loan review processes. For both the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL, SBA loan review processes are not effectively identifying overpayments. Further, SBA could not demonstrate how it accounted for overpayment risks associated with new PPP lenders in its review processes. Including lenders in the financial technology sector helped the PPP reach borrowers. However, it also increased the risk of overpayments as SBA relied on these lenders’ processes and controls as part of review and approval of borrower loan applications.

DOL guidance and procedures. Pandemic-related UI programs generally follow guidance in DOL’s regular UI program letters. This guidance lists three administrative functions to help ensure UI program integrity. States must (1) detect benefits paid through error, (2) deter claimants from obtaining benefits through willful misrepresentation, and (3) recover overpaid benefits under certain circumstances. DOL provides resources to states to assist with recoveries of pandemic-related UI overpayments. This includes training on updated guidance and procedures, funding opportunities to help states ensure timely benefit payments, and tools to facilitate more effective identity verification processes.

Overpayment recovery efforts. SBA tracks certain data related to PPP and COVID-EIDL improper payments, but it does not have a sufficient process for tracking identified overpayments and subsequent recoveries. Without these data, SBA cannot ensure that it is maximizing the potential of certain recovery methods, which may limit recoveries. DOL’s UI recovery rate calculation does not include all identified overpayments. DOL subtracts waived overpayments from its calculation, which may inflate the recovery rate. States have had little success in recovering overpayments. As of April 2024, states recovered approximately $3.7 billion of the $55.2 billion overpayments identified in the pandemic-related UI programs from March 2020 through September 2023. Further, DOL did not set an overpayment recovery rate baseline for states to meet. Including a measurement of success in guidance to State Workforce Agencies could better position DOL to monitor states’ efforts to recover overpayments from future temporary programs.

|

Abbreviations

|

|

|

ALP |

acceptable levels of performance |

|

ARPA |

American Rescue Plan Act |

|

BSA |

Bank Secrecy Act |

|

DOL |

Department of Labor |

|

EIDL |

Economic Injury Disaster Loan |

|

ETA |

Employment and Training Administration |

|

fintech |

financial technology |

|

FPUC |

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation |

|

IPA |

independent public accountant |

|

LSP |

lender service provider |

|

MEUC |

Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PEUC |

Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation |

|

PIIA |

Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 |

|

PPP |

Paycheck Protection Program |

|

PUA |

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

SWA |

State Workforce Agencies |

|

Treasury |

Department of the Treasury |

|

UI |

unemployment insurance |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 13, 2024

Congressional Committees

As of April 2024, the federal government has spent $4.4 trillion in funding related to COVID-19 response and recovery. Early in the pandemic, agencies prioritized swiftly distributing funds and implementing new programs to help businesses and individuals adversely affected by COVID-19. This urgency involved trade-offs that put billions of taxpayer dollars at increased risk for improper payments, including overpayments.[1] Two agencies, the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the Department of Labor (DOL), were charged with overseeing certain pandemic programs to help small businesses and individuals, respectively.

As noted in Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance, it is preferable that agencies focus efforts toward preventing overpayments from occurring; however, it is important for agencies to have cost-effective means to both identify and recover overpayments if they do occur.[2] According to PaymentAccuracy.gov reporting, for fiscal years 2021 through 2023, SBA reported recovering $19 million of $1 billion in overpayments identified for recovery, and DOL reported recovering $4 billion of $23 billion in overpayments identified for recovery.[3] Across the federal government—including SBA and DOL—agencies reported recovering a total $71 billion of the $142 billion in overpayments identified for recovery for this period, according to PaymentAccuracy.gov.

Following the enactment of legislation that among other things provided assistance to businesses negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, SBA quickly set up the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program, and other relief programs.[4] Since spring 2020, SBA has provided significant assistance to small businesses adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

SBA administered programs providing more than $1 trillion in loans and grants. This funding assisted more than 10 million small businesses, primarily through the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL program.[5] However, concerns about SBA’s implementation of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL led us to include Emergency Loans for Small Businesses on our High Risk List in March 2021.[6] We identified significant program integrity risks, including potential for fraud, and the need for improved SBA management and oversight. SBA estimated 40.5 percent of PPP loan forgiveness and 49.1 percent of PPP guarantee purchase payments were improper, according to agency reporting on PaymentAccuracy.gov for fiscal year 2023.

The CARES Act created three federally funded temporary DOL unemployment insurance (UI) programs—Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, and Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation.[7] These programs expanded UI benefit eligibility, enhanced benefits, and extended benefit duration. In addition, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, created the Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation program. This program, which was voluntary for states, authorized an additional $100 weekly benefit for certain UI claimants.[8] DOL’s UI program expenditures totaled about $900 billion from April 1, 2020, through May 31, 2023, according to DOL data.[9]

The UI program is overseen by DOL and administered by the states, as a federal-state partnership that provides temporary financial assistance to eligible workers who become unemployed through no fault of their own. The UI program has also faced long-standing challenges with program integrity, which increased dramatically during the pandemic. Due to these challenges and others, we added the overarching Unemployment Insurance System to our High Risk List in June 2022.[10] DOL estimated that 35.9 percent of Pandemic Unemployment Assistance payments were improper, according to agency reporting on PaymentAccuracy.gov for fiscal year 2023.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to report on our ongoing monitoring and oversight efforts related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[11] For this report, we (1) examined the extent to which SBA and DOL have developed effective processes for identifying and recovering overpayments of COVID-19 relief funds and (2) analyzed the extent to which SBA and DOL efforts to recover overpayments of COVID-19 relief funds have been successful.

To determine which agencies and programs to include in our review, we reviewed program outlays for the top five COVID-19 spending areas as of June 30, 2022. Due to the amount of COVID-19 outlays in SBA’s PPP and COVID-19 EIDL program and the DOL UI programs, in addition to the reported concerns that resulted in these programs being placed on our High Risk List, we selected these programs for our review.

To address our first objective, we reviewed SBA and DOL documentation regarding overpayment identification and recovery efforts. We met with agency officials to discuss the processes and procedures involved in these efforts. In addition, we reviewed federal laws along with federal regulations and standards. We compared the agencies’ overpayment recovery processes and procedures to the relevant laws and guidance.

To address our second objective, we reviewed and analyzed public datasets to assess the extent of agencies’ success in the recovery of overpayments. However, overpayments are not always recoverable and unclear or nonreported data make the full extent of identified and recovered overpayments unknown. See appendix I for more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2022 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

SBA’s COVID-19 Programs

In March 2020, Congress passed and the President signed into law the CARES Act. The act provided funds for a new SBA pandemic relief program, the PPP, which was authorized under SBA’s existing 7(a) small business lending program.[12] It also expanded eligibility for SBA’s EIDL program to make loans (known as COVID-19 EIDL loans) available to businesses experiencing economic injury caused by COVID-19.[13] Both PPP and COVID-19 EIDL contained programmatic elements that were new compared to the pre-pandemic programs. The number of loan applications SBA received for these selected programs was significantly greater than the number it generally receives for its traditional guaranteed loan and disaster loan programs.[14]

Paycheck Protection Program

Under PPP, SBA guaranteed over $800 billion in loans to small businesses and nonprofits, referred to collectively in this report as small businesses. The loans were to be used for payroll costs, rent, utilities, and other eligible operating costs during the pandemic.

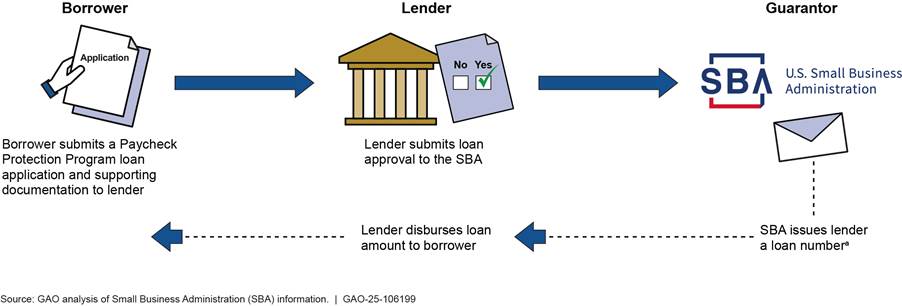

PPP low-interest loans were fully guaranteed by SBA. The loans were made to recipients through a network of participating lenders under program rules set by the Department of the Treasury and SBA’s Office of Capital Access. PPP loans were designed for SBA to offer full forgiveness to eligible borrowers, under certain conditions. For example, to be eligible for full forgiveness, at least 60 percent of the loan had to be used for payroll costs, with the remaining amount used for eligible nonpayroll costs, such as covered mortgage interest, rent, and utility payments.[15] See figure 1 for more information on the PPP application process.

aIf a loan application was denied by the lender, SBA directed applicants to contact the lender directly. However, if SBA denied a loan as a result of a Paycheck Protection Program final loan review it conducted, the borrower could appeal the decision with SBA’s Office of Hearings and Appeals within 30 calendar days after receipt of the decision.

In accordance with the CARES Act, PPP loans required no collateral or personal guarantees. Borrowers were not required to make loan repayments until their forgiveness application was processed or 10 months after the covered period ended (from 8 to 24 weeks), if the borrower failed to apply for forgiveness within that time.[16] Once loan funds were used, borrowers could apply for forgiveness at any point on or before the maturity date of the loan (up to 5 years).

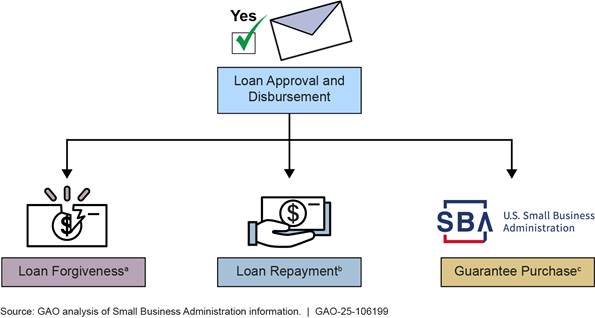

Once a PPP application was approved and the loan disbursed, borrowers had two options to satisfy the loan. They could either apply for loan forgiveness, whether in whole or in part, or repay the loan. If a borrower was determined ineligible for loan forgiveness, whether in whole or in part, they were responsible for repaying the unforgiven portion of the loan. If a borrower became more than 60 days past due in their repayments, lenders were able to submit a request for a guarantee purchase from SBA.[17] This loan guarantee acted as collateral to provide lenders with satisfactory security to support a loan. Under the rules of PPP, SBA’s guarantee purchase for PPP loans was 100 percent of the loan amount if the lender complied with all applicable PPP requirements. However, defaulted borrowers were still responsible for repaying their loans.[18] See figure 2 for more information.

aLoans could be forgiven if the funds were used for eligible expenses. Borrowers could apply for forgiveness once all loan proceeds for which the borrower is requesting forgiveness have been used. Forgiveness applications could be approved in full, in part, or denied.

bIf a borrower has not applied for forgiveness or did not receive full forgiveness, they must make standard repayments on the loan.

cIn instances where a borrower becomes more than 60 days past due, lenders may submit a guarantee purchase request to the Small Business Administration to recoup the outstanding balance of the loan.

The PPP application process operated in two stages referred to as Round 1 and Round 2. Applicants could apply for first draw loans in PPP Round 1 from April through August 2020, and first or second draw loans in PPP Round 2 from January through May 2021.[19] The PPP closed to new applications following May 2021, but parts of the PPP are still operating. For example, existing borrowers may apply for forgiveness up to the maturity date of their loans, and PPP lenders may continue to request a guarantee purchase from SBA for defaulted loans.

To assist with the review process for PPP, SBA used a contractor to facilitate the automated and—if necessary—manual reviews of PPP loan applications to assess borrower eligibility and determine if a loan warranted further review by an SBA official. This review process was revised a few times throughout the course of the program to increase its effectiveness.

Over the program’s application period—which ran from April 2020 to May 2021—SBA guaranteed more than 11 million PPP applications, totaling more than $799 billion in loans. As of July 2024, borrowers submitted over 10 million forgiveness applications, with SBA forgiving approximately $760 billion.[20]

COVID-19 EIDL

SBA directly managed the COVID-19 EIDL program through its Office of Disaster Assistance and later through its Office of Capital Access. The program included two types of assistance: loans and grants, the latter of which were otherwise known as advances. Advances were a new programmatic element available to COVID-19 EIDL applicants, as well as targeted and supplemental targeted advances that were available to applicants meeting certain criteria.[21] While advances were a part of the COVID-19 EIDL program, we did not include them in the scope of our review.

COVID-19 EIDL loans were meant to be used for working capital and other normal operating expenses and were not forgivable, with loan increases being available until the funds were exhausted.[22] Additionally, SBA required collateral for COVID-19 EIDL loans greater than $25,000, and personal guarantees were required for loans greater than $200,000.

In January 2022, SBA stopped accepting applications for new COVID-19 EIDL loans and advances, and by April 2022, SBA approved almost 4 million COVID-19 EIDL loans totaling nearly $378 billion.

In May 2022, SBA stopped processing COVID-19 EIDL loan increase requests or requests for reconsideration of previously declined applications. According to SBA, as of June 2024, it continues to service more than 2.25 million COVID-19 EIDL loans—the vast majority of which have entered into active repayment, and there are approximately 277,000 loans that are more than 30 days delinquent and 1.11 million loans in charge-off status.[23]

DOL’s Unemployment Insurance Programs

The federal government and states coordinate to administer UI programs. States design and administer their own UI programs within federal parameters, while DOL monitors states’ compliance with federal requirements. According to DOL, state statutes establish specific benefit structures, eligibility provisions, benefit amounts, and other program aspects. Regular UI benefits—those provided by state UI programs before the CARES Act was enacted—are funded primarily through state taxes levied on employers and are intended to replace a portion of a claimant’s previous employment earnings, according to DOL.[24]

The CARES Act created the following three federally funded temporary UI programs that expanded benefit eligibility and enhanced benefit amounts, which were amended by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA):[25]

1. Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) was generally available from March 2020 through September 6, 2021, and authorized UI benefits for individuals not otherwise eligible for UI benefits, such as the self-employed and certain contingent workers,[26] who were unable to work because of specified COVID-19 reasons.[27] The total federal expenditure for PUA program benefits was $138 billion through May 31, 2023.[28]

2. Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) generally authorized an additional $600 weekly benefit through July 2020 and a $300 weekly benefit for weeks beginning after December 26, 2020, and ending on, or before, September 6, 2021, for individuals eligible for UI benefits available under the regular UI program and the CARES Act UI programs.[29] The total federal expenditure for FPUC program benefits was $442 billion through May 31, 2023.

3. Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) was generally available through September 6, 2021, and authorized additional weeks of UI benefits for those who had exhausted their regular UI benefits.[30] The total federal expenditure for PEUC program benefits was $90 billion through May 31, 2023.

In addition, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, created the Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation (MEUC) program, which was extended by ARPA and expired in September 2021.[31] According to DOL, the MEUC program was intended to supplement regular UI claimants whose benefits did not account for a significant self-employment income. Consequently, these claimants may have received a lower UI benefit than they would have received had they been eligible for PUA. The total federal expenditure for MEUC program benefits was $78 million through May 31, 2023.

State Workforce Agencies (SWA) implemented temporary UI programs and processed unprecedented claims volumes during the pandemic. A key challenge facing those SWAs was simultaneously ensuring that UI benefits were paid solely to eligible applicants and in the correct amounts—including ensuring that program monitoring over the use of funds was sufficiently designed and accurately reported at the state and federal level. The CARES Act and ARPA contained provisions to assist SWAs—in detecting and preventing fraud, promoting equitable access, and ensuring timely payment of benefits to eligible workers—and starting in March 2021, also provided additional funding for DOL to provide financial and technical assistance to states to improve UI systems and processes.[32]

High-Risk Programs

From March 2020 through March 2022, SBA made or guaranteed more than 15 million loans through the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL programs. SBA quickly set up these programs to respond to the adverse economic conditions small businesses faced. This quick implementation left SBA susceptible to improper payments, including overpayments, resulting in SBA’s Emergency Loans for Small Businesses being added to our High Risk List in 2021.[33] In November 2023, SBA’s financial statement auditor reported (for the fourth consecutive year) material weaknesses in controls associated with the two programs that led to loans going to potentially ineligible borrowers.[34] These weaknesses limit the reliability of SBA’s financial reporting, and they contributed to SBA’s inability to obtain an opinion on its fiscal years 2020 to 2023 financial statements.

Further, in June 2022, we added the UI system to our High Risk List because we found that UI’s administrative and program integrity challenges posed significant risks to service delivery and exposed the system to significant financial losses.[35] Long-standing challenges with UI administration and outdated IT systems have affected states’ ability to meet the needs of unemployed workers, especially during economic downturns. Such challenges have also contributed to impaired service, barriers to equitable access, and disparities in benefit distribution. The unprecedented demand for UI benefits and the need to quickly implement the new programs during the pandemic increased the risk of improper payments, specifically overpayments. In addition, DOL received a qualified opinion on its fiscal years 2021 through 2023 financial statements from its independent auditor. DOL was unable to adequately support assumptions used for estimating remaining obligations and benefit overpayments related to UI.[36]

Recovering Overpayments

The federal government has several legal mechanisms in place to recover overpayments. For example, Chapter 37 of Title 31 of the United States Code gives federal agencies the authority to recover debts owed to the government. Certain programs operate under a structure that may result in the recovery of overpayments. For example, in a lending program, if a borrower has agreed to repay a loan in full, the amount repaid will include any amount received as an overpayment (i.e., any portion of the loan in excess of what the borrower was eligible to receive under program rules).

Additionally, the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 (PIIA) requires agencies to perform recovery audits on each program or activity with expenditures of $1 million or more per year if conducting such audits would be cost-effective.[37] OMB has issued guidance—in Appendix C to OMB Circular A-123 (OMB M-21-19)—to agencies on the identification and recovery of overpayments.[38]

Agencies may waive recovery of overpayments under certain conditions. Further, since fiscal year 1997, we noted in our audit reports on the U.S. government’s consolidated financial statements that the federal government is unable to determine the full extent of its improper payments, including overpayments. It is important for agencies to have cost-effective procedures to both identify and recover overpayments if they do occur. If agencies take prompt action, they may increase their ability to recover identified overpayments.

SBA and DOL Have Review and Recovery Processes, but SBA’s Processes Do Not Effectively Identify Overpayments

SBA Is Not Effectively Identifying Overpayments in Selected Programs

SBA’s PPP Loan Review Processes

Throughout the course of the PPP, SBA developed and implemented multiple review processes that continued to evolve as the program was administered. The review processes helped detect loan applications with potential fraud or errors that would have resulted in an overpayment once disbursed. However, both the independent public accounting firm (IPA) serving as SBA’s financial statement auditor and SBA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) have reported concerns pertaining to the review processes’ effectiveness that could also affect their ability to identify overpayments. In addition, these review processes were not designed to specifically identify overpayments within the selected program, and the current processes do not appear to be designed to sufficiently identify erroneous or potentially fraudulent loans in the selected programs that would result in overpayments.

To implement the PPP, the CARES Act provided SBA and Treasury joint authority to permit new lenders to participate in the PPP to aid in the processing and approval of a significant amount of PPP loan applications (almost 12 million approved applications in total). Ultimately participating PPP lenders included depository institutions (for example, banks and credit unions) and nondepository lending institutions (for example, SBA-certified development companies and state-regulated financial companies). Existing 7(a) lenders were automatically allowed to participate in PPP.

SBA relied on lenders with delegated authority under the CARES Act to make and approve covered PPP loans. Due to the unique, emergency nature of the program, the processing requirements for PPP loans differed significantly from the traditional 7(a) loan program requirements. Generally, SBA’s 7(a) program lender criteria and underwriting are based on the borrower’s creditworthiness and ability to repay the loan, among other things. In contrast, the PPP did not include a creditworthiness check. Instead, it required that lenders perform reviews of loan applications that could help identify applications for potential fraud or errors, as applications with errors or potential fraud may have resulted in overpayments if funds were disbursed.[39] Moreover, all PPP lenders had to demonstrate the ability to comply with applicable Bank Secrecy Act requirements.[40]

During PPP Round 1, SBA did not conduct any review of loan or borrower information beyond looking for duplicate applications before issuing an SBA loan number to the lender. Issuing a loan number enabled the lender to proceed with the loan—meaning SBA did not review the loan applications before the lenders disbursed funds. However, SBA and its contractor began conducting automated loan eligibility and forgiveness reviews for Round 1 applications in August 2020 and manual reviews in October 2020—after the Round 1 loans had been approved and disbursed.

During PPP Round 2, SBA added front-end compliance checks to the loan application process via an automated screening process. Specifically, SBA started using an automated screening system to identify anomalies or attributes that may indicate noncompliance with eligibility requirements or potential fraud after the lender requested a loan number but before the lender disbursed the loan.[41] If the system identified a potential issue, a compliance check error message or hold code identifying the issue would be placed on the loan application until the issue was resolved.[42]

When borrowers first began applying for and receiving PPP loans, SBA had yet to design and implement the forgiveness and guarantee purchase elements of the program. As a result, review processes evolved as SBA implemented the forgiveness and guarantee purchase steps. There are various types of review processes for the PPP, including eligibility reviews, forgiveness reviews, and guarantee purchase reviews. These processes were performed by a mix of contractor and SBA staff and generally occurred after disbursement. However, Round 2 loans did undergo certain checks that could flag potential noncompliance with eligibility.

Eligibility reviews. SBA and its contractor conducted eligibility reviews post-disbursement for Round 1 loans and pre-disbursement for Round 2 loans. These reviews were not designed specifically to identify overpayments or potential overpayments, but they could aid in doing so. This process consisted of three steps that used an automated screening process to flag loans for manual reviews by the contractor and then SBA, if necessary. See appendix II for more details on the steps of the SBA review process. As of July 2024, SBA had manually reviewed 431,891 PPP loans—around 3.7 percent of the loans made.

Throughout the course of the PPP, SBA and its contractor worked to refine the manual review process. In its February 2022 report, the SBA OIG discussed the potential effect of changes that were subsequently made to SBA’s loan review process.[43] Prior to June 2021, SBA reviewed a loan once the borrower submitted a forgiveness application. However, in June 2021, SBA updated this process to prioritize reviews based on fraud risk rather than forgiveness status.

While this change meant that SBA would be able to review loans with a high risk of fraud that had not yet filed for forgiveness, it also meant that a certain number of loans would be manually reviewed after the loan had already been forgiven. OMB states that agencies should prioritize efforts toward preventing improper payments from occurring to avoid operating in a pay-and-chase environment.[44] Although this update prioritized reviews for loans with a higher risk of fraud, it also increased the difficulty of recovering loans that were ultimately found ineligible for forgiveness by creating a pay-and-chase environment.[45]

Additionally, the SBA OIG previously reported that SBA’s manual loan reviews were not always sufficient to ensure borrowers’ eligibility. Specifically, the SBA OIG statistically sampled 176 of the 25,634 loans with matches from Treasury’s Do Not Pay system and concluded that SBA inappropriately resolved 92 of the loans, despite the Do Not Pay match. By projection, the SBA OIG estimated that lenders disbursed, and SBA forgave, 12,234 of 25,634 loans (or 48 percent) totaling over $1.4 billion without verifying the borrowers’ eligibility, which the SBA OIG concluded further exposed the program to financial losses and improper payments.[46]

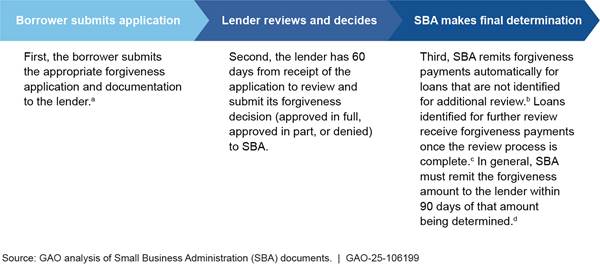

Forgiveness reviews. Under SBA rules and guidance, the loan forgiveness process has three steps. While these steps may help SBA to identify overpayments in some cases, they were not designed for that purpose. See figure 3 for more details.

aGenerally, a borrower is eligible for forgiveness any time on or before the loan maturity date if the borrower has used all the loan funds for which the borrower requests forgiveness. Additionally, in July 2021, SBA announced the availability of a forgiveness platform that provided a single location for borrowers to apply for forgiveness online. While this platform was previously limited to certain borrowers, in February 2024, SBA announced the expansion of the platform to allow borrowers that have not yet received forgiveness to submit their applications through the platform.

bIn October 2020, SBA issued an interim final rule generally allowing borrowers of a Paycheck Protection Program loan of $50,000 or less to use a simplified loan forgiveness process and application form. In addition, we previously reported that SBA expedited the review process by, where appropriate, removing low-risk alerts connected to loans under $150,000 that may have delayed loan forgiveness processing.

cIf the loan is identified for further review, SBA conducts a manual review. SBA will notify the lender that it is beginning a review and will request that the lender provide certain documentation for the review process. At the end of the review, SBA will remit the appropriate forgiveness amount to the lender or notify the lender that the forgiveness request has been denied.

dIn its interim final rule on loan forgiveness published in June 2020, SBA stated that it will extend this time frame if the loan or forgiveness application is under SBA review. 85 Fed. Reg. 33,004, 33,005 (June 1, 2020). SBA and Treasury officials previously told us that they interpreted the CARES Act requirement to remit funds within 90 days to be subject to SBA’s review of loans.

In October 2020, as part of the PPP loan forgiveness application process, SBA required that any borrower that received PPP loans of $2 million or greater submit a loan necessity questionnaire. SBA used the questionnaires to determine whether borrowers met the good-faith requirements that they certified to in their loan applications.[47] However, in July 2021, SBA stopped requiring submissions of the questionnaire as it determined that the loan necessity reviews were lengthy and caused delays beyond the 90-day statutory timeline for forgiveness.[48] SBA told us that before halting this requirement, its contractor completed 2,161 loan necessity reviews and recommended that 2,117 of the borrowers made the certification in good faith and should have their loans forgiven. The remaining 44 loans were referred to SBA’s Office of Capital Access with a recommendation for further review. However, it appears these loans did not undergo additional review, as SBA informed us that the loan necessity reviews were discontinued following approval from OMB to discontinue the questionnaires.

While this questionnaire was no longer required after July 2021, applicants were still required to self-certify on their PPP loan application that the loan was necessary due to current economic conditions. However, we have previously reported that relying on applicant self-certifications can leave a program vulnerable to exploitation by those who wish to circumvent eligibility requirements or pursue criminal activities.[49]

In addition, SBA’s IPA identified concerns with SBA’s forgiveness review process related to monitoring controls and the control environment around the automated screening process in its report on SBA’s fiscal year 2023 financial statements.[50]

This finding, along with the discontinuance of loan necessity questionnaires for loans of $2 million or more, raises concerns that SBA may have increased the likelihood that forgiveness applications for potentially fraudulent or erroneous PPP loans were inadvertently approved, potentially resulting in overpayments.

Guarantee purchase reviews. In July 2021, SBA began allowing lenders to submit PPP guarantee purchase requests if a borrower became more than 60 days late in their payments. This obligated SBA to purchase 100 percent of the loan from the lender if the lender complied with all applicable PPP requirements. After receiving a guarantee purchase request from a lender, SBA could approve the request and charge off the loan—including loans with unresolved hold codes or loans that had previously been referred to the SBA OIG for potential fraud—if SBA determined the lender met its obligations.

However, SBA had the authority to reject the request if a review indicated that the loan was approved due to a lack of lender due diligence. If lenders were not in compliance with programmatic requirements during the loan processing and approval phases, the loan could be ineligible for guarantee purchase, whether in whole or in part.[51] As of March 2024, SBA has manually reviewed 82,764 guarantee purchase requests—around 10.4 percent of the guarantee purchase requests received at the time.[52]

SBA’s IPA also identified concerns with SBA’s guarantee purchase process in its November 2023 report.[53] Specifically, the IPA identified concerns with SBA’s controls around the completeness and accuracy of alerts used in the guarantee purchase review process.

While the review processes described above—related to eligibility, forgiveness, and the guarantee purchase process—helped identify PPP loans that may have been ineligible or fraudulent, thus identifying potential overpayments, the SBA OIG and SBA’s IPA have reported various concerns related to these processes. These findings add to concerns that SBA’s current PPP review processes may not be effectively identifying overpayments, as certain erroneous or potentially fraudulent PPP loans may not be flagged and reviewed at all.

SBA’s COVID-19 EIDL Review Processes

The review process for COVID-19 EIDL loans consisted of certain reviews occurring pre-disbursement and a separate review process that was mostly conducted post-disbursement. Although these reviews could help to identify overpayments or potential overpayments, reported concerns related to the reviews indicate they are not effective for identifying overpayments.

Initially, SBA used a subcontractor’s electronic validation system to review loan applications. This system used public information and certain fraud indicators to assess and verify loan application information. The system would also attempt to verify an applicant’s bank account. However, this process depended on the banks’ customer identification program, and the subcontractor estimated that 40 percent of banks did not collect enough information for its system to verify a bank account.[54] The main reasons the automated validation system would deem an application ineligible were (1) insufficient economic injury; (2) ineligible business type; or (3) ineligible answers to other application questions, such as felony convictions.

SBA made changes over the course of the program to enhance the controls in its application review process and to identify potential fraud that could result in subsequent overpayments. For example, in May 2020, SBA updated its front-end controls on the application to include the validation of bank account routing numbers, which helped ensure that funds were being sent to the correct borrower’s bank account. In addition, in July 2020, SBA began validating the types of tax identification numbers associated with the types of entity (e.g., validating that an entity applied using an employer identification number and not a Social Security number) to help mitigate and identify potential fraud. If the automated system flagged a potential eligibility, fraud, or credit issue associated with a loan, the loan was then passed on to an SBA loan officer to review and attempt to mitigate the issue(s). If the loan officer was unable to do so, the loan was referred to the SBA team leader for review. If the issue was resolved, the applicant received an approval letter. If the team leader rejected the application, the applicant was notified that the application was declined.

However, the SBA OIG found that until August 2020, applications that did not contain certain fraud alerts flagged by the automated validation system were being approved by team leaders in batches with little to no additional review by others.[55] According to the SBA OIG report, these applications contained other issues that SBA did not review at the time, such as the inability to confirm business registrations. The report also stated that, after August 2020, SBA stopped approving loans in batches and began requiring SBA staff to review all applications prior to approval and to mitigate all system alerts. SBA data showed that from April through August 2020, SBA approved about 3.2 million applications.

Further, in April 2021, SBA started incorporating tax information as part of its review process to confirm that businesses existed on or before January 31, 2020—a requirement for program eligibility—and to verify business revenue.[56] However, SBA continued to rely on applicant self-certification for certain eligibility criteria, as allowed by the CARES Act. This included, but is not limited to, applicants self-certifying that they met employee size limits; they were a U.S. citizen, noncitizen national, or qualified alien; and they were not debarred from contracting with the federal government or receiving federal grants or loans. In addition, the COVID-19 EIDL application informed applicants that they were self-certifying under penalty of perjury. However, as discussed above, reliance on applicant self-certifications can leave a program vulnerable to exploitation and result in potential fraud and subsequent overpayments.

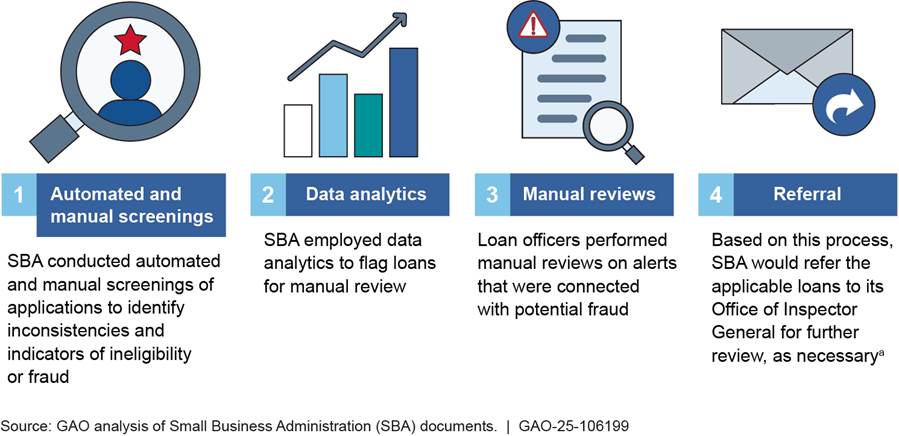

In addition, SBA used a review process for COVID-19 EIDL loans to help identify and refer potentially fraudulent loans to the SBA OIG. This review process consisted of four parts, including automated and manual screenings, data analytics, manual reviews, and referrals to the SBA OIG as necessary. See figure 4 for additional information on SBA’s review process for COVID-19 EIDL loans.

Figure 4: COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan Review Process for Referral to the Office of Inspector General

aLoans not referred to the SBA Office of Inspector General were determined to be free of potential fraud risk.

Similar to the PPP review processes discussed above, we also identified concerns in SBA’s review process for COVID-19 EIDL loans and its ability to identify overpayments within the program. For example, in November 2023, SBA’s IPA reported concerns with the COVID-19 EIDL loan manual review process and its ability to effectively identify loans with eligibility concerns.[57]

In addition, the IPA found that SBA’s controls over loans with existing hold codes were not properly designed and there was not sufficient evidence to support management’s reliance on the controls.[58] These findings, in addition to the reliance on self-certification for certain eligibility criteria, add to concerns that SBA’s review process for COVID-19 EIDL loans may not be designed to sufficiently identify loans with potential fraud or errors, which may result in overpayments remaining unidentified.

While the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL review processes aided in identifying some overpayments, SBA has not sufficiently documented its processes to demonstrate how it identifies overpayments resulting from potential errors or fraud, as its current processes do not appear to be designed to effectively identify erroneous or potentially fraudulent loans.

Further, without a process in place to effectively identify overpayments, SBA is not able to provide reasonable assurance that previously approved PPP guarantee purchase requests met eligibility requirements prior to the purchase, as there is a risk that some potential overpayments may have been issued due to a lender’s lack of due diligence in the loan origination process.

Federal internal control standards state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to significant changes that could impact the internal control system.[59] They further state that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks, and that management should implement control activities through policies. Without an expanded and documented process in place to ensure that SBA is identifying overpayments in the selected programs, SBA cannot provide reasonable assurance that it is effectively identifying overpayments for potential recovery. Additionally, there is an increased risk that SBA may inadvertently purchase PPP loans that could be ineligible for guarantee purchase, which potentially limits SBA’s ability to recover overpayments.

SBA’s PPP Guarantee Purchase Process

While the inclusion of new lenders helped the PPP reach more borrowers, it also increased the risks of overpayments. However, SBA did not take sufficient steps to mitigate this risk in its guarantee purchase process.

The CARES Act authorized SBA to use lenders already approved to participate in SBA’s 7(a) program to make and approve PPP loans. It also permitted SBA and Treasury to authorize new lenders, provided they met certain requirements.[60] Lenders were paid a processing fee from SBA to encourage them to participate in the PPP. Under the initial guidelines, lenders earned a 5 percent fee on loans of $350,000 or less; a 3 percent fee on loans of more than $350,000 and less than $2 million; and a 1 percent fee on loans of $2 million or more.[61] This arrangement enabled lenders to earn billions of dollars in fees for processing PPP loan applications.[62]

A large group of new lenders in the PPP were those in the financial technology (fintech) sector. Fintech lenders are generally defined as online, nonbank lenders that leverage financial technology to provide consumers and small businesses with loans.[63] When the PPP was created, fintech lenders advocated for the ability to assist with the program. According to a fintech trade association, fintech lenders believed they could facilitate small business lending as their technology could handle a large amount of data and processing quickly.

We previously reported that program changes to PPP—such as allowing new lenders (including fintech lenders) to participate in the program—helped increase lending to the smallest businesses and in underserved locations.[64] However, we have also reported that there may have been vulnerabilities in some fintech lenders’ loan origination and verification processes, specifically those related to fraud prevention.

For example, in May 2023, we reported that certain lenders originated a disproportionate share of fraudulent and potentially fraudulent loans when compared to the share of all PPP loans.[65] We found that lenders with the top five highest rates of loans associated with PPP fraud cases tended to use fintech lenders to automate loan origination as lender service providers (LSP).[66]

While opening the PPP to fintech lenders may have helped the program reach new borrowers and process more applications, it also placed a reliance on the fintech lenders’ internal controls to perform reviews of borrower loan applications—whether as direct lenders or as LSPs. However, these controls may not have been sufficient to ensure that there were no obvious signs of error or potential fraud in the applications, increasing the risk of approving loans for and making overpayments to ineligible borrowers.

This extension of control, and the CARES Act’s hold harmless provision, introduced inherent risks to the PPP as a wave of new lenders (including fintech lenders) joined the program.[67] According to SBA, Treasury and SBA jointly reviewed and approved 848 new lenders to participate in the PPP, in addition to the 4,837 lenders already authorized to participate in SBA’s programs. These lenders were able to collect a processing fee for each disbursed PPP loan while facing minimal risk if potentially fraudulent or erroneous PPP applications were not identified prior to approving the loan.

In July 2021, SBA released guidance that stated SBA would review a lender’s request for guarantee purchase and charge-off in accordance with PPP loan program requirements.[68] According to the notice, SBA would honor its guarantee and purchase 100 percent of the outstanding balance of the loan provided that the lender had complied with all PPP loan program requirements, including the lender’s underwriting requirements and document collection and retention requirements. However, we found that SBA lacks sufficient documentation to demonstrate that its process for verifying lender compliance ensures that lenders met these requirements and performed an appropriate level of due diligence.

In addition, in its September 2022 report, the SBA OIG stated it found no evidence that SBA had a formal process to review lender compliance with debt collection activities in its PPP loan guarantee purchase process, including ensuring lenders sent out 60-day demand letters to borrowers in default.[69] Further, in November 2023, SBA’s IPA reported that SBA management did not have adequate or effective monitoring controls related to its PPP lenders.[70] This finding aligns with our concern that SBA may be missing out on potential overpayment recoveries through the guarantee purchase process, as there may be lenders that approved loans without performing sufficient good-faith reviews, making the loan guarantees potentially ineligible for purchase.

Federal internal control standards state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to significant changes that could impact the internal control system, and that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[71] Although SBA has published guidance and notices related to the PPP, without sufficient documented procedures in place, SBA cannot demonstrate how, as part of its guarantee purchase process, it considered and mitigated potential new risks that were introduced into the PPP by allowing fintech lenders to participate in the program. Further, SBA cannot demonstrate how its review process considered the increased risk that lenders or their LSPs did not comply with programmatic requirements prior to approving and purchasing PPP guarantees from lenders. Therefore, there is an increased risk that overpayments resulting from loans disbursed in excess of what a borrower was eligible for during the loan origination and approval process were not identified prior to SBA approving a purchase guarantee request, which may affect SBA’s ability to recover the overpayments.

SBA Recovers Overpayments Using Regular Loan Servicing and Recently Updated Efforts to Recover Certain Defaulted Loans

SBA has various methods in place to recover an outstanding loan balance in the event of default, which would include the recovery of any associated overpayments. These methods include, but are not limited to, relying on the borrower to repay the loan, sending demand letters, or referring the loans to Treasury for collection.

In April 2022, SBA adopted a policy to end collection on defaulted loans in the selected programs that had outstanding balances of $100,000 or less and did not refer the loans to Treasury for collections.[72] Federal law allows agencies to suspend or end collections on claims of $100,000 or less when certain conditions are met, including when it appears that the cost of collecting the claim is likely to be more than the amount recovered.[73] According to the SBA OIG, absent such conditions, before making a referral to Treasury, SBA must send a letter to the borrower giving them 60 days to either pay the loan in full or negotiate an acceptable payment plan.[74] Loans that are referred to Treasury go through its two delinquent debt collection programs, the Treasury Offset Program and the Cross-Servicing program.[75] Both SBA and Treasury also take action to prevent such borrowers from receiving additional federal financial assistance.

In January 2024, SBA reversed this policy and stated it would begin referring loans of $100,000 or less to Treasury for collection beginning in March 2024, including any loans previously charged off without referral. Prior to this reversal, SBA had taken steps to try and determine whether collections on subject loans in its selected programs would be cost-effective.

PPP: In April 2022, SBA performed a cost-benefit analysis on PPP loans to support its decision to end collections on loans valued at $100,000 or less. In September 2022, the SBA OIG argued that this analysis was not comprehensive enough to support this decision and recommended that SBA conduct a new cost-benefit analysis on purchase guarantees to determine if the cost of collecting on the subject loans was more than the expected recovery amount. SBA agreed to conduct a new analysis using a third-party. In announcing its policy reversal in January 2024, SBA stated that an updated cost-benefit analysis showed collection attempts, including referrals to Treasury, would be cost beneficial.

According to SBA, prior to January 2024, there were multiple factors that affected its ability to attempt overpayment recoveries, such as (1) the improbability that recovery amounts would outweigh the cost of collection efforts and (2) collection on loans with a balance of $100,000 or less would be inequitable.[76] Further, SBA believed ending collections on subject loans would eliminate the labor-intensive process of making referrals to Treasury and SBA’s estimated multimillion-dollar monthly cost of sending 60-day notification letters. However, as discussed above, the SBA OIG previously investigated SBA’s decision to end collections on purchased PPP loan guarantees with a balance of $100,000 or less—including its decision to not refer the loans to Treasury—and determined that SBA’s April 2022 analysis was not comprehensive enough to sufficiently support this decision.[77]

COVID-19 EIDL: In May 2021, SBA contracted a third party to assess the COVID-19 EIDL portfolio, which was about $226 billion of loan commitments at the time.[78] The third party ultimately recommended that SBA sell the debt to ensure a strategy that would maximize the value of the portfolio, but SBA decided to not pursue this recommendation and did not provide an explanation as to how it made that decision at the time.[79] SBA officials later informed us that they believed the recommendation was flawed due to various concerns with the cost assessment’s design.[80]

According to SBA, agency officials believed various factors would affect its ability to attempt overpayment recoveries at the time. For example, based on the cost assessment, SBA officials decided it was improbable that recovery amounts would outweigh collection efforts and that using current disaster staff to collect on COVID-19 EIDL loans would distract from SBA’s core mission.

As a result, based on the cost assessment, SBA management originally determined it would not be cost-effective to pursue collections, including referral to Treasury, on the loans of $100,000 and below for the program. Although, according to the SBA OIG, SBA planned to continue providing past due notices, due process letters, and demand letters to delinquent COVID-19 EIDL borrowers with loan balances of $100,000 or less. For delinquent borrowers, SBA also planned to refer borrowers to credit bureaus and ensure borrowers are included on Treasury’s Do Not Pay system.[81]

However, in this same report, the SBA OIG noted several concerns with the cost assessment SBA used to support its decision to end active collections on COVID-19 EIDL loans and noted the estimates were unreliable. Specifically, the SBA OIG stated that prematurely ending active collection activities on delinquent COVID-19 EIDL loans with balances of $100,000 or less put SBA at risk of violating federal law, given that the full extent of fraudulent loans in the COVID-19 EIDL portfolio is unknown. The SBA OIG stated that agencies have an affirmative responsibility to try to collect delinquent debts owed to them and that agencies can only suspend or end collections on claims when certain criteria are met. The SBA OIG also cited 31 U.S.C. 3711(b)(1), which prohibits agencies from ending collections on claims that appear to be fraudulent, false, or misrepresented claims by a party with an interest in the claims.

The SBA OIG also believed that prematurely ending active collections on delinquent COVID-19 EIDL loans would inhibit the additional fraud detection that could be attained through collections efforts. In addition, the SBA OIG stated that by foregoing referral to Treasury and ending active collections earlier, SBA was limiting the time available for oversight entities to identify additional fraudulent loans through ongoing or future reviews.[82]

In November 2023, the SBA’s IPA reiterated the concern that SBA was not fully complying with federal debt collection requirements due to its delays and absence of referrals of delinquent borrowers and guarantors to Treasury.[83]

As mentioned above, in January 2024 SBA announced it would begin referring charged-off loans in selected programs with a balance of $100,000 or less to Treasury for collection, including any loans that were previously charged off without referral to Treasury. According to SBA, it started referring subject loans to Treasury in March 2024, following a 60-day grace period. During this grace period, SBA communicated this change in policy to borrowers and helped ensure they understood the effect of default and the available paths back to compliance, in addition to making internal technology and process updates at SBA to handle this change.

According to SBA, it based this decision on the results of a third-party cost analysis that was completed in December 2023 on the PPP. The updated analysis showed that referral to Treasury would likely yield a positive return for taxpayers. According to the analysis, estimated net recoveries fall between $104 million and $223 million.[84] Due to the expected recovery amount, the third party advised SBA that it would be cost-effective to pursue collections through Treasury referral. Although this policy change appears to be an improvement in SBA’s collection efforts for loans in the selected programs with a balance of $100,000 or less, more time is needed before the effect of these changes can be fully assessed.

DOL Generally Follows Its Regular UI Processes to Identify and Recover Overpayments of COVID-19 Relief Funds

DOL’s Processes

The pandemic-related UI programs generally follow DOL’s Unemployment Insurance Program Letters guidance and procedures for overpayment recovery established for regular UI.[85] UI is a federal-state partnership, and according to DOL, states are required to perform the following three administrative functions to help ensure UI program integrity at the state level: (1) detect benefits paid through error by the SWA or through willful misrepresentation or error by the claimant or others; (2) deter claimants from obtaining benefits through willful misrepresentation; and (3) recover overpaid benefits, under certain circumstances.[86]

According to DOL guidance, the department partnered with states to implement a wide array of national integrity strategies and to develop tools and share best practices to prevent improper payments and recover overpayments. The three required functions listed above are accomplished by SWA staff, who are responsible for promoting and maintaining the integrity of the UI program through overpayment prevention, detection, investigation, establishment, and recovery. SWA staff also prepare cases for prosecution, as necessary. SWAs generally implemented these functions for the pandemic-related UI programs in the same manner as for the regular UI programs using DOL’s mandatory and recommended processes, such as

· National and State Directory of New Hires Cross-match,[87]

· Quarterly Wage Records Cross-match,[88]

· Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlement,[89]

· Social Security Administration Cross-match,[90]

· Interstate Benefits Cross-match,[91] and

· UI Integrity Center’s Integrity Data Hub tools.[92]

According to DOL, as part of these program integrity functions, states are required to report various UI data to DOL through online submissions to a DOL database. This information includes overpayments, recoveries, write-offs, and waivers. An overpayment occurs when claimants receive UI benefits to which they are not entitled.

After a state identifies an overpayment, the state must take actions to recover the overpayment. The state informs the claimant of the potential overpayment and gathers information from the claimant and other parties in order to reach a conclusion on the overpayment. If the state establishes an overpayment against the claimant, a determination letter is sent and the claimant has the option to appeal the overpayment, accept the SWA’s decision and repay the overpayment, or to request that the state waive recovery of the overpayment. For states to approve a pandemic-related overpayment waiver request, the claimant cannot be at fault and the recovery must be contrary to equity and good conscience. If the claimant does not respond to the state notice, states can collect overpayments through recovery activities.[93]

According to DOL officials, states are required to use the following as part of their recovery activities: benefits offsets, the Treasury Offset Program, the Cross Program Offset Recovery Agreement, and the Interstate Reciprocal Overpayment Recovery Arrangement.[94]

· Benefits offsets. Using benefits offsets allow states to recover non-fraud and fraud overpayments by deducting from future benefits payments. Generally, state law determines the time frame for benefits offset; however, for pandemic-related UI programs, apart from PUA, the CARES Act, as amended, set this time frame to 3 years from the date the original payment was made to the claimant.[95]

· Treasury Offset Program. Under this program, recoveries of UI certain overpayments are offset against an individual’s federal income tax refund or other federal payments due to the individual.[96]

· Cross Program Offset Recovery Agreement. States that have signed this agreement with the Secretary of Labor are allowed to offset federal benefits to recover state UI overpayments and to offset state UI benefits to recover federal benefit overpayments.[97]

· Interstate Reciprocal Overpayment Recovery Agreement. Using this arrangement allows states to offset overpayments of unemployment compensation paid under other states’ unemployment compensation laws.[98] For example, if a claimant received an overpayment in one state but has also worked in another state and is now collecting unemployment benefits in the new state, the prior state can collect overpayments by offsetting the new state’s unemployment compensation under this arrangement.

The CARES Act, as amended, does not specify a time restriction for other UI recovery methods beyond the benefits offsets option. However, the act does state that determinations of fraud and overpayments by state agencies are subject to review in the same manner and to the same extent as regular UI and only in that manner and to that extent. Therefore, states follow the time frames in their own laws and guidance for these other methods.

In addition to the above activities, DOL encourages states to perform further recovery procedures such as: offsets via state income tax offset programs, wage garnishments, civil actions, property liens, collection agency referrals, credit bureau referrals, and other recovery methods as determined by state law or policy. According to DOL guidance, some state laws also include provisions for denying or suspending professional licenses of persons who owe repayments of UI overpayments.[99] For fraudulent overpayments, states may bring criminal charges, which can lead to fines and prison sentences.[100]

The unprecedented demand for UI benefits and the need to quickly implement the new programs during the pandemic increased the risk of improper payments and overpayments in particular. Because of this increased risk, the CARES Act provides authority for states to waive recovery of identified overpayments in the pandemic-related UI programs.[101] DOL’s Unemployment Insurance Program Letters provide states further guidance on waiving recovery of an overpayment if the individual is not at fault and if the recovery would be contrary to equity and good conscience.

States waive recovery of regular UI overpayments slightly differently than for pandemic-related UI overpayments. According to DOL, for regular UI programs, states waive recovery of overpayments based on their state laws. Some examples of when these waivers are generally granted include when overpayments are the result of agency error or employer error, or when recovery would be against equity or good conscience, cause financial hardship, or for other reasons.

For pandemic-related UI programs, DOL has approved seven scenarios under which states may automatically apply blanket waivers of overpayments for cases where claimants are not at fault and recovery is against equity and good conscience. If a waiver situation does not fall under any of the seven scenarios, the state may waive overpayments on a case-by-case basis, without needing to submit additional documentation to DOL. DOL helps ensure that each state is applying waivers properly through monitoring conducted by DOL’s Employment and Training Administration’s regional offices. This process involves the regional offices selecting a sample of cases involving the use of waivers and reviewing to ensure that waivers were properly applied.

The seven blanket waiver scenarios are as follows:

1. The individual answered “no” to being able to work and available for work, and the state paid PUA or PEUC without adjudicating the eligibility issue. Upon requesting additional information from the individual, the individual either did not respond or the individual confirmed being unable to work or unavailable for work for the week in question, resulting in an overpayment for that week.[102]

2. When an individual is eligible for payment under an unemployment benefit program for a given week, but through no fault of the individual, was instead incorrectly paid under either the PUA or PEUC program at a higher weekly benefit amount.[103]

3. The state paid the wrong amount on a PUA or PEUC claim because the state, through no fault of the individual, used the wrong amount when calculating the allowance, resulting in an overpayment equal to a minimal difference in dependents’ allowance for each paid week.

4. The individual answered “no” to being unemployed, partially unemployed, or unable or unavailable to work because of COVID-19 and the state paid PUA anyway. Upon requesting a new self-certification, the individual either did not respond or the individual confirmed that none of the approved COVID-19-related reasons were applicable, and the state’s payment resulted in an overpayment for that week.[104]

5. Through no fault of the individual, the state paid the individual a minimum PUA weekly benefit amount based on Disaster Unemployment Assistance guidance that was higher than the state’s minimum PUA weekly benefit amount, which resulted in an overpayment.[105]

6. The individual complied with instructions from the state to submit proof of earnings to be used in calculating the individual’s PUA weekly benefit amount. However, through no fault of the individual, the state’s instructions were either inadequate or the state incorrectly processed this calculation using self-employment gross income instead of net income or documents from an inapplicable tax year, resulting in an incorrect higher PUA weekly benefit amount.

7. The individual complied with instructions from the state to submit proof of self-employment earnings to be used in establishing eligibility for MEUC. However, through no fault of the individual, the state’s instructions were either inadequate or the state incorrectly processed this calculation using the incorrect self-employment income or based on documents from an inapplicable tax year, resulting in the individual incorrectly being determined eligible for MEUC.[106]

According to DOL, if a state has exhausted efforts to collect an overpayment, it may remove the amount for accounting purposes (also known as a write-off) if state law permits it to do so. A write-off does not limit a state’s legal authority to collect the overpayment, should the opportunity arise. States write off regular UI overpayments and pandemic-related UI overpayments similarly. Generally, states write off regular UI and pandemic program UI overpayments when the statute of limitations expires, bankruptcy is approved by a court, or the claimant is deceased.[107]

DOL’s Resources and Guidance

Since the beginning of the pandemic, DOL published over 60 Unemployment Insurance Program Letters to help states administer the pandemic-related UI programs, which address various issues, including reporting instructions and recovery of pandemic-related UI overpayments. The instructions require states to report UI program integrity activities (for both regular UI and the pandemic-related UI programs) on a quarterly basis for all programs except PUA, which is reported monthly through the UI Database Management System.[108] DOL’s instructions note that states should maintain adequate program records of all their activities in identifying overpayments, which should also draw a clear distinction between fraudulent or erroneous overpayments.[109]

According to DOL, the DOL data reporting system has built-in edit checks to help ensure that required fields are not blank and do not contain incompatible data. Once submitted, these data are publicly available on the Employment and Training Administration data downloads website.[110]

DOL has provided SWAs various resources to improve their UI systems. Some examples include allocating ARPA funding, IT modernization funding, and other grant funding to states.[111] Through September 2023, DOL had awarded a total of $783 million in grant funding to 52 of the 53 UI SWAs for states’ investigative and overpayment recovery efforts. According to DOL, states are using grant funds for investigations and overpayment recoveries among other things. Along with grant funds, DOL provided states resources such as

· sending expert “Tiger Teams” directly to states to help identify process improvements that can speed benefit delivery, address equity concerns, and fight fraud;

· additional integrity-specific funding for pandemic-related UI programs;[112]

· providing tools to help address immediate fraud concerns by facilitating more effective identification verification processes;

· developing IT solutions that states can adopt to modernize antiquated state technology;[113]

· announcing funding opportunities to help states ensure timely payment of benefits, promote equitable access, and combat fraud; and

· providing states additional resources such as training sessions to help clarify and update Unemployment Insurance Program Letters and handbooks for new procedures to address SWA concerns.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 rescinded $1 billion of unobligated amounts from the ARPA funds available for the UI program.[114] This recission, according to DOL officials, caused DOL to cancel previously issued grant opportunities, and also resulted in a reduction in the amount of fraud prevention and integrity grants, which states could have used to support overpayment recovery efforts.

SBA and DOL Have Not Sufficiently Tracked Progress of Overpayment Recovery Efforts in Selected Programs

SBA Has Insufficient Tracking Processes for Identified Overpayment and Recoveries

SBA does not have clear, documented procedures for tracking identified overpayments in the selected programs. While SBA tracked certain PPP loans where the funds had been identified for return to SBA that may result in the recovery of an overpayment, this process was not designed specifically to track identified overpayments for recovery. Additionally, SBA tracks certain data related to improper payments in its PPP and COVID-19 EIDL programs; however, it does not have sufficient data to determine how effective its overpayment recovery methods are. Although SBA provided us with data regarding recovery amounts for both programs, we were unable to determine an overpayment recovery rate for either program or assess the effectiveness of SBA’s recovery methods.

SBA’s process tracked PPP loans identified for the return of funds to SBA for various reasons, including

· loans where a lender suspected fraudulent activity;

· loans where a borrower accidentally paid SBA, who is then required to return funds to the borrower and direct them to repay the lender; or

· circumstances where a borrower received duplicate loans (due to the nature of the PPP application process) and the borrower was attempting to pay back the duplicate loan.[115]

To track these loans, SBA used a spreadsheet on an informal, ad-hoc basis with referrals from lenders, SBA personnel, and the SBA OIG.

Additionally, SBA did not have a tracking process in place for identified overpayments in the COVID-19 EIDL program. Based on our communication with SBA, a primary reason for this was that SBA anticipated capturing any overpayments through its standard repayment process, as borrowers were required to repay the total loan amount in the COVID-19 EIDL program, including any overpayments associated with the loan.

Further, while SBA tracked recoveries for charged-off loans in the selected programs, it did not separate out whether those recoveries were associated with an overpayment or whether the recoveries were from a properly paid loan. This is because SBA has not identified what portion of the delinquent loan population was properly paid and what portion was an overpayment (e.g., the portion of a loan made in excess of eligibility). While SBA reviews loans for certain fraud risks that would result in an overpayment if disbursed, there are concerns around the overall review process and its ability to detect loan amounts in excess of borrower eligibility, as we discussed above. As a result, it is not possible to determine what percentage of these recovery amounts are from overpayments being recovered.

In its most recent report on SBA’s compliance with PIIA requirements, SBA’s IPA identified several concerns with SBA’s PPP and COVID-19 EIDL improper payment estimates due to inadequate sample review processes and incomplete populations.[116]

SBA’s insufficient overpayment identification and tracking process affected its ability to produce the accurate and reliable sample results needed to develop statistically valid improper payment and unknown payment rate estimates for the selected programs because its sample population was not complete. If SBA improved its overpayment tracking process, it could help provide reasonable assurance that its sampling and review processes include complete populations which may be used to produce statistically valid estimates, as required by PIIA.[117]

Federal internal control standards state that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks, management should implement control activities through policies, and management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[118] Without effectively identifying overpayments and developing a formal tracking process to record overpayments identified for recovery, SBA could be both unaware of and missing out on potential recoveries, as potential overpayments would not be flagged for recovery. Therefore, SBA’s identified overpayment population for both programs may be incomplete. As a result, SBA cannot provide reasonable assurance that the data it uses to calculate estimates of overpayments and subsequent recovery amounts and rates are accurate for the two programs, and it risks not maximizing its recovery efforts.

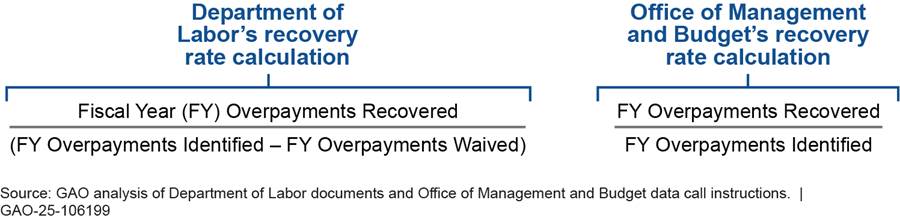

DOL’s UI Recovery Rate Calculation Does Not Include All Identified Overpayments

DOL does not include all identified overpayments when calculating its recovery rate for regular and pandemic-related UI programs, contrary to OMB instructions. OMB provides instructions to agencies for use in preparing annual improper payments data submissions for PaymentAccuracy.gov.

OMB’s fiscal year 2023 data call instructions tell agencies to calculate recovery rates using overpayments identified and overpayments recovered. Overpayments identified is equal to the sum of overpayments identified through recovery activities and overpayments identified through recovery audits. OMB does not instruct agencies to exclude overpayments for which they are not pursuing recovery (i.e., waived overpayments) from the recovery rate calculation. While agencies with appropriate legal authority may waive the recovery of certain overpayments, waived overpayments are still considered to be monetary loss improper payments and should be reflected in agency recovery rates.