DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY CONTRACTING

Actions Needed to Strengthen Certain Acquisition Planning Processes

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106207

United States Government Accountability Office.

View GAO‑25‑106207. For more information, contact Allison Bawden at (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106207, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY CONTRACTING

Actions Needed to Strengthen Certain Acquisition Planning Processes

Why GAO Did This Study

DOE obligates tens of billions of dollars annually on contracts to support critical missions and the management and operation of its laboratories and production facilities. Aspects of DOE’s acquisition process have been on GAO’s High Risk List since 1990. Congressional committees and industry have raised questions about the prolonged nature of some DOE acquisitions and abrupt cancellations of multibillion-dollar contract awards.

Several congressional committee reports include provisions for GAO to review aspects of DOE’s acquisition planning. GAO examined the extent to which DOE (1) implemented selected acquisition planning practices and (2) has readily available information about solicitation cancellations and contract award terminations and delays.

GAO reviewed federal procurement data as of January 2023, along with relevant contract files, for selected contracts awarded in fiscal years 2017 through 2022 (the most recent at the time of review). GAO identified contracts for review based on criteria such as potential total contract value and having a written acquisition plan. GAO also interviewed DOE officials and representatives from 10 selected industry entities.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations, including that DOE revise its acquisition lessons learned process, implement procedures to improve how certain data are collected, and assess the role of requirements setting in causing solicitations to be canceled or awards to be terminated. DOE and NNSA agreed with the 12 recommendations.

What GAO Found

Offices in the Department of Energy (DOE), including the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), implemented eight of 10 selected acquisition planning practices for 20 contracts GAO reviewed. For example, DOE offices conducted market research and created written acquisition plans and milestones for all 20 contracts. However, independent government cost estimates, important for estimating potential contract costs, were not always developed, even though DOE guidance directs officials to perform them. Instead, DOE offices sometimes obtained waivers of office-specific direction to conduct such estimates or used a budget-based model that is typically based on current budget forecasts.

DOE offices also did not always include evidence indicating that contracting officers reviewed lessons learned from prior acquisitions or followed a lessons learned process for acquisitions that employs all leading practices. Consistently reviewing and leveraging knowledge gained from prior acquisitions, as well as using a process that follows all lessons learned leading practices, can help ensure that past mistakes are not repeated and opportunities to improve acquisition planning are not lost.

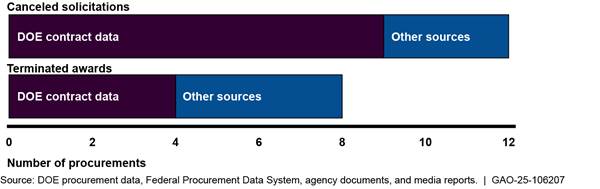

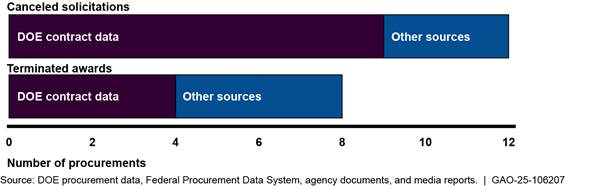

DOE does not have readily available procurement data on the number of canceled solicitations and terminated awards for fiscal years 2017 through 2022 in its contract database. Reviewing other data sources, GAO identified canceled solicitations and terminated awards that were not captured in DOE’s contract data (see figure).

Number of Department of Energy (DOE) Canceled Solicitations and Terminated Awards, by Data Source, Fiscal Years 2017–2022

DOE and office requirements and guidance provided limited instruction about how to record and report cancellations and terminations. DOE officials reported that cancellations and terminations are infrequent, but GAO found that such actions can have considerable negative effects on industry and DOE, including financial losses. By providing clearer guidance to contracting officials on how to properly record and report data on these actions, DOE could improve the reliability of information to better understand the frequency with which they occur, and any underlying causes and necessary corrective actions. Changes to requirements contributed to the majority of canceled solicitations and terminated contracts, but DOE officials told GAO they had not assessed this issue. Doing so would better position DOE to determine any root causes or potential improvements to requirements setting.

Abbreviations

|

DEAR |

Department of Energy Acquisition Regulation |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

EM |

Office of Environmental Management |

|

ESCM |

End State Contracting Model |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FPDS |

Federal Procurement Data System |

|

IDIQ |

indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity |

|

IGCE |

independent government cost estimate |

|

M&O |

management and operating |

|

NNSA |

National Nuclear Security Administration |

|

PALT |

procurement administrative lead time |

|

RFP |

request for proposals |

|

SAM |

System for Award Management |

|

SEB |

source evaluation board |

|

STRIPES |

Strategic Integrated Procurement Enterprise System |

|

WAPA |

Western Area Power Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 21, 2024

Congressional Committees

In fiscal year 2023, the Department of Energy (DOE) obligated $46.3 billion for contracts to support critical missions such as modernizing the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile and cleaning up radioactive and hazardous waste. Approximately 79 percent (about $36.7 billion) of these obligations were for management and operating (M&O) contracts, including multibillion-dollar contracts supporting the department’s scientific laboratories and engineering and production facilities.[1]

DOE has also awarded thousands of smaller contracts supporting its diverse missions. Aspects of DOE’s acquisition processes have been on our High-Risk List since 1990, with DOE’s record of inadequate contract management and contractor oversight leaving the department vulnerable to fraud, waste, and abuse.[2] Congressional committees and industry have highlighted ongoing challenges with DOE acquisitions, raising questions about the prolonged nature of the process and abrupt cancellations of multibillion-dollar contracts.

Our prior work on issues related to acquisition planning across parts of the federal government has found that inadequate acquisition planning can increase the risk that the government may receive services that cost more than anticipated, are delivered late, and are of unacceptable quality.[3] Inadequate acquisition planning may result from poorly defined requirements and not incorporating prior lessons learned. Moreover, in June 2006, we reported on aspects of DOE’s acquisition process. We found that delays in awarding contracts occurred in most of the contracts we reviewed and noted that such delays can increase costs to the companies competing for DOE contracts and may affect their willingness to compete for such contracts in the future. In 2006, we recommended that DOE better address delays in awarding contracts by tracking and monitoring the timeliness of the department’s contract award process from planning to contract award.[4] At the time, DOE stated that, to implement the recommendation, the department planned to review certain performance measures and consider benchmarking them against other federal agencies. Based on this information, we closed the recommendation, as discussed later in the report.

Several congressional committee reports and joint explanatory statement language include provisions for GAO to review various aspects of, or related to, DOE’s acquisition planning, including for M&O contracts.[5] This report examines the extent to which DOE (1) implemented selected acquisition planning practices for contracts we reviewed and (2) has readily available information about the number and value of solicitation cancellations and contract award terminations and delays.

To address our objectives, we developed four groups of DOE solicitations and contracts. To do so, we used contract award data reported as of January 2023 from the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS), which is the system of record for federal procurement data.[6] We also obtained data on canceled solicitations and terminated contracts reported as of March 2023 from DOE’s Strategic Integrated Procurement Enterprise System (STRIPES), which is DOE’s primary repository for contract information. Specifically,

· For our first objective—whether DOE implemented selected acquisition planning practices for contracts—we reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 20 DOE contracts awarded from fiscal years 2017 through 2022.[7] Each contract had a potential value of at least $100 million at the time of award, which ensured that we included M&O contracts.[8] We also selected these contracts to ensure that we included a range of dollar values, different contracting offices, and a variety of the types of goods and services being acquired.

· For our second objective—whether DOE has readily available information about the number and value of solicitation cancellations and contract award terminations and delays—we reviewed three groups of contracts and solicitations, all valued at least at $5.5 million. These groups included (1) a nongeneralizable sample of 12 canceled solicitations from fiscal years 2017 through 2022, (2) all contract awards terminated for convenience from fiscal years 2017 through 2022 for which termination was not related to contractor performance, and (3) all fiscal year 2022 contracts awarded later than planned.[9]

· We assessed the reliability of DOE’s FPDS and STRIPES data by (1) performing electronic testing, (2) reviewing existing information about the data and systems that produced them, and (3) interviewing agency officials knowledgeable about the data. We determined the data, despite some limitations that we describe in our report, were sufficiently reliable for identifying contracts awarded from fiscal years 2017 through 2022 and reporting on issues related to canceled solicitations, terminated contracts, and delayed contract awards.

For our first objective, we compared DOE’s implementation of its acquisition planning process for the 20 selected contracts to 10 selected practices. We selected these 10 practices because either they are requirements from the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR); they are emphasized in DOE policies and guidance, including DOE’s Acquisition Guide; or our prior work identified them as important to successful acquisition outcomes.[10] We assessed the contract files for the presence of evidence that the selected practices had been followed. We did not assess the quality of the identified documentation because the FAR provides acquisition professionals with the flexibility to take actions to ensure their decisions are in the best interest of the government.

For objective two, we reviewed requirements in the FAR related to canceled solicitations and terminated awards.[11] We also reviewed department-wide policies and guidance and office-specific supplementary documentation. We also compared DOE’s management and use of available data on canceled solicitations and terminated and delayed awards with related principles in the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and the Framework for Assessing the Acquisition Function at Federal Agencies.[12] We examined available documentation for the solicitations and awards, such as in the acquisition plan; milestone schedule; and, if applicable, the solicitation cancellation determinations. In some cases, we also reviewed GAO bid protest decisions and related media reports.

For fiscal year 2022 contract award delays, we compared the planned award date specified in the contract files for awarding the contract, typically found in the acquisition plan, with the date the contract was actually awarded. Because the planned award date is developed early in the acquisition process and before the issuance of a solicitation, we did not examine procurement administrative lead time (PALT) data, which is the amount of time from solicitation to contract award.[13]

We also obtained written responses and interviewed officials from across DOE about acquisition planning and the practices we selected for review and data and issues related to canceled solicitations, terminated contracts, and delayed contract awards. These offices included the Office of Environmental Management (EM) Consolidated Business Center, Office of Science, Office of the Chief Information Officer, Office of Nuclear Energy, Western Area Power Administration (WAPA), and the National Energy Technology Laboratory, as well as DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management and the National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) Office of Partnership and Acquisition Services.

To obtain industry perspectives for our second objective, we also interviewed representatives from 10 industry entities, which can include individual companies, organizations, or universities that are, or have expressed interest in, contracting with DOE. The views of the industry representatives interviewed cannot be generalized to all industry entities, but they provided valuable insights to our work. Appendix I presents a more detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2022 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Acquisition Roles and Responsibilities at DOE

Acquisition authority at DOE flows from the Secretary of Energy to two Senior Procurement Executives responsible for management direction of the acquisition systems of the department, including implementing the department’s acquisition policies, regulations, and standards.[14] Specifically,

· DOE’s Senior Procurement Executive also serves as the Director of the Office of Acquisition Management. This office is responsible for (1) establishing acquisition-related policies and guidance for the department and (2) managing DOE’s acquisition process. In fulfilling these responsibilities, the Office of Acquisition Management develops, issues, maintains, and interprets acquisition regulations, policies, and guidance. The office also provides assistance and oversight for acquisition activities within the Office of Science, EM, and other DOE offices, exclusive of NNSA; and provides operational acquisition services to DOE Headquarters and staff organizations.

· NNSA’s Senior Procurement Executive also serves as the Deputy Associate Administrator for the Office of Partnership and Acquisition Services. This office is responsible for ensuring that NNSA implements DOE’s acquisition policies and regulations as well as NNSA’s own supplemental directives and procedures. NNSA, which possesses authority to deviate from DOE policies and procedures,[15] generally follows all DOE acquisition management policy, according to DOE documentation.

Because of the decentralized nature of the department, there are also many offices within DOE and NNSA that are critical to the acquisition planning process. These offices include DOE program offices, such as EM and the Office of Science; functional offices, like the Office of Management, that provide management and other support functions to the program offices and the department as a whole; and field and site offices, which provide federal oversight of the day-to-day activities of contractors. Key staff involved in the acquisition process include contracting officers who enter into, administer, modify, or terminate contracts on behalf of the government; contracting officers’ representatives who perform specific technical or administrative functions as designated by a contracting officer; and program and project managers who help develop accurate requirements, define performance standards, and manage contractor activities to ensure intended outcomes are achieved.[16]

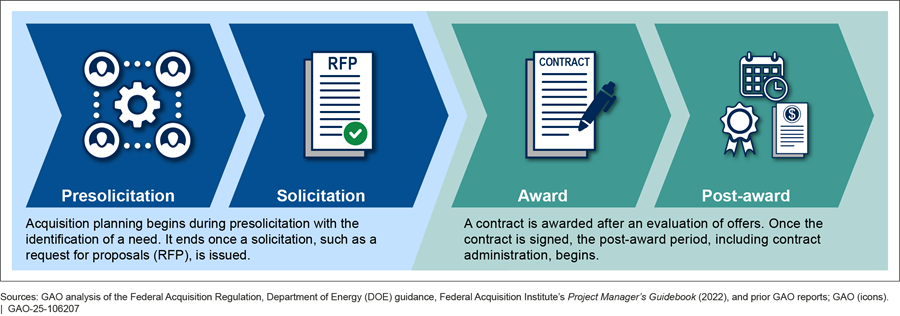

DOE’s Acquisition Process for Contracts

DOE’s acquisition process is governed by the FAR, which is the primary regulation used by all executive agencies in their acquisition of supplies and services with appropriated funds.[17] DOE supplements the FAR with the Department of Energy Acquisition Regulation (DEAR)[18] and other internal policies and procedures, such as the department’s Acquisition Guide and acquisition letters issued by the Senior Procurement Executive. Generally, program and contracting officials share responsibility for the majority of acquisition planning activities. Although there can be variation, the acquisition process at DOE typically occurs in four phases: presolicitation, solicitation, award, and post-award (see fig. 1).

1. Acquisition planning begins at presolicitation. During this phase, a need for products or services is identified and requirements for meeting that need are defined. Once requirements are determined, the contracting officer is responsible for reviewing knowledge gained from prior acquisitions, or lessons learned, to further refine requirements and inform acquisition strategies. Officials from both the program and contracting offices are to conduct market research to gain an understanding of current market conditions and available solutions. DOE’s Acquisition Guide also directs procurement officials to produce an independent government cost estimate (IGCE) for every acquisition with an estimated value that exceeds the simplified acquisition threshold.[19] IGCEs help project the costs a contractor may incur in the performance of a contract and can be used by contracting officers to compare offerors’ proposed prices and determine whether proposed contract prices are reasonable.

In addition, DOE typically requires a written acquisition plan for acquisitions that will use certain contract types. According to the FAR, the specific content of acquisition plans will vary, in part depending on the nature and circumstances of the acquisition, though some information is required.[20] For example, milestones for completing the acquisition must be identified. These milestones can also serve as a consistent measure of contract award timeliness and indicator of whether the acquisition process was managed well.[21] The acquisition plans also provide the rationale for selecting a contract type.[22] There are two broad categories of contracts: cost reimbursement and fixed price.[23] In some instances, the use of certain types of contracts, such as M&O contracts, requires additional approval by senior officials.

2. The proposed acquisition is publicized through the issuance of a solicitation. The contracting officer, in consultation with the agency’s legal team and other stakeholders, is responsible for finalizing and issuing a solicitation. The solicitation identifies what DOE wants to acquire, provides instructions to prospective contractors on how to submit offers, and specifies the evaluation factors that will be used to evaluate submitted offers. One type of solicitation is a request for proposals (RFP).[24] Acquisition planning ends once a solicitation is issued.

3. The evaluation of proposals results in a contract award. For contracts like most of those in our scope, technical experts are responsible for evaluating submitted proposals based on the evaluation factors specified in the solicitation.[25] This includes evaluating proposals, then reaching consensus on and documenting each proposal’s strengths, weaknesses, and deficiencies, as well as assessing the reasonableness of the price or cost proposals. Based on the input from the technical experts, the source selection authority, normally a senior program official at Headquarters or a field office, makes a final selection and the contracting officer awards the contract.[26]

4. The post-award period, which includes contract administration, begins following the signing of a contract. The successful offeror begins the day-to-day execution of the contract’s requirements, sometimes following a period of transition from an incumbent contractor. Agency staff are responsible for monitoring the contractor’s performance and compliance with the terms of the contract to ensure that the government gets what it paid for in terms of cost, quality, and timeliness. If necessary, the contracting officer may seek to modify the contract, such as by making changes to the scope of work or period of performance.[27]

Canceled Solicitations, Terminated Contracts, and Delayed Contract Awards

In most cases, a planned acquisition will proceed through all four phases of the acquisition process and result in an award and administration of a contract. However, in certain circumstances, the contracting officer may cancel, terminate, or delay a solicitation or award.

· Cancellation: A solicitation may be canceled when there are substantial changes in requirements and funding, there is no longer a requirement for the supply or service, or it is in the best interest of the government.[28] Agencies, however, are not permitted to cancel a solicitation as a pretext for improper motives or reasons, such as to avoid awarding a contract on a competitive basis or to avoid resolving a bid protest.[29] If a solicitation is canceled, the contracting officer may also publish a notice of solicitation cancellation in the System for Award Management (SAM), a data system that allows government agencies and contractors to search for companies based on ability, size, location, experience, ownership, and more.[30]

· Termination: A contract may be terminated for convenience, such as in the event that a program’s requirements have changed, rendering continued performance unnecessary. A contract can also be terminated, either completely or partially, for default as a result of the contractor’s actual or anticipated failure to perform its contractual obligations.[31] Agencies typically have wide latitude in terminating contracts for convenience. However, the contracting officer is permitted to do so only when the termination is determined to be in the best interest of the government. Once the decision is made to terminate the contract, the contracting officer must send a written termination notice to the contractor. In a complete termination for convenience, the contract ends on the date specified in the notice of termination.[32]

· Delay: There can be delays throughout the contract award process for various reasons. For example, a bid protest of a solicitation may lead an agency to take corrective actions, which could result in revising and reissuing the solicitation. In addition, a delay may occur if an agency decides to enter into discussions with industry after the receipt of proposals, even though no time for this activity was allotted in the acquisition schedule for carrying out the contract award.

In some cases, a planned acquisition may experience all three of these actions. For example, an award can be made, but after certain events result in a substantial delay to the finalization of the award, the requirements of the original solicitation may change substantially. In such a scenario, the agency may elect to terminate the contract and cancel the solicitation in favor of a new solicitation.

DOE Generally Implemented All but Two Selected Acquisition Planning Practices for Contracts We Reviewed

DOE offices generally implemented eight of the 10 selected acquisition planning practices for the 20 contracts we reviewed. The two practices DOE did not always implement were developing an IGCE and implementing lessons learned requirements.

DOE Offices Generally Implemented Eight of the 10 Selected Practices

From our analysis of contract files, including acquisition plans, we determined that DOE offices implemented eight of 10 selected acquisition planning practices. Seven of the 10 practices are applicable to all 20 contracts we reviewed, and the two practices DOE did not always implement—developing an IGCE and implementing lessons learned requirements—were among these seven. The remaining three practices we selected are applicable to some of the 20 contracts we reviewed, depending on the type of contract. Table 1 lists the seven acquisition practices and the extent that DOE offices implemented them for the 20 contracts we reviewed.

Table 1: DOE Offices’ Implementation of Seven Selected Acquisition Planning Practices Applicable to All 20 Reviewed Contracts

|

Practice |

Description |

Extent implemented (number of contracts) |

|

Requirements documentation |

Program offices develop documentation, such as a statement of work, statement of objectives, or performance work statement, to define requirements clearly and concisely, identifying specific work to be accomplished, the responsibilities of the government, and the objective measures that will be used to monitor the work performed. Among other things, FAR Part 11 prescribes policies and procedures for describing agency needs. This includes stating requirements with respect to an acquisition of supplies or services in terms of functions to be performed, performance required, or essential physical characteristics. |

20 of 20 |

|

Market research |

Market research, which is typically started by the program office once a need is identified, is the process used to collect and analyze information about capabilities in the market to satisfy agency needs. Under FAR Part 10, agencies are required to conduct market research to arrive at the most suitable approach to acquiring, distributing, and supporting supplies and services. |

20 of 20 |

|

Written acquisition plan |

The acquisition plan communicates the program office’s approach to senior management and provides the overall strategy for accomplishing and managing an acquisition by documenting the approach to fill the need, optimize resources, and satisfy policy requirements for a proposed acquisition. Close coordination with the contracting officer is important when developing the contracting strategy and business approach. Under FAR Part 7, a written plan shall be prepared for cost reimbursement and other high-risk contracts other than firm-fixed-price contracts (written plans may be required for firm-fixed-price contracts, as appropriate). |

20 of 20 |

|

Acquisition milestones |

Acquisition milestones are the points during the acquisition process at which decisions should be made to facilitate attainment of the acquisition objectives. DOE’s Acquisition Guide explains that milestones must be identified as early as possible. Under FAR Part 7, acquisition milestones must be identified in acquisition plans. |

20 of 20 |

|

Contract type selection |

The process of choosing a contract type entails selecting the most appropriate type of contract based on a variety of factors that meets the needs of the acquisition, protects the government’s interest, and properly allocates risk between the government and contractor. FAR Part 16 describes types of contracts that may be used in acquisitions. Moreover, it prescribes policies and procedures and provides guidance for selecting a contract type appropriate to the circumstances of the acquisition. |

20 of 20 |

|

Practice |

Description |

Extent implemented (number of contracts) |

|

Independent government cost estimate (IGCE) |

An IGCE is an important tool for both program and contracting officials and represents the government’s estimate of the resources and the projected costs of the resources a contractor will incur in the performance of a contract. These costs include direct costs, such as labor, material, supplies, equipment, or transportation; indirect costs, such as overhead, general, and administrative expenses, and fringe benefits; and profit or fee. Although the FAR does not require IGCEs in most cases, DOE’s Acquisition Guide states that an IGCE is required for every procurement action in excess of the simplified acquisition threshold and is usually developed by the program office during acquisition planning.a |

9 of 20 |

|

Lessons learned |

A lesson learned can be defined as knowledge or understanding gained by experience, either positive or negative, that results in a measurable change in behavior (e.g., leads to improvement). There are two components to this practice: (1) identifying and incorporating lessons learned from prior acquisitions, and (2) identifying and documenting potential lessons learned during or after planning. FAR Part 7 describes two elements for which agency heads shall prescribe procedures: (1) assuring that the contracting officer, prior to contracting, reviews the acquisition history of the supplies and services, and (2) ensuring that knowledge gained from prior acquisitions is used to further refine requirements and acquisition strategies. |

12b of 20 14c of 20 |

Source: GAO analysis of a nongeneralizable sample of acquisition planning practices selected from Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) requirements; Department of Energy (DOE) policy and guidance, including the Acquisition Guide; prior GAO reports; and documentation from the General Services Administration and Center for Army Lessons Learned. | GAO‑25‑106207

aAt the time of our review, the typical simplified acquisition threshold was generally $250,000, although simplified acquisition procedures can be used for procurements up to $15 million in certain cases, such as when the contract is for contingency operations or defense against or recovery from cyber, nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological attacks. 48 C.F.R. 2.101, 13.500(c)(1).

bWe found evidence in the contract files for 12 of the 20 selected contracts that indicated that prior lessons learned were reviewed and, as appropriate, incorporated during the acquisition planning process for the current acquisition.

cWe found evidence in the contract files for 14 of the 20 selected contracts that indicated that potential lessons learned identified during acquisition planning were documented for the current acquisition.

We identified some variation in the implementation of the five practices that were generally implemented by DOE offices for all 20 contracts we reviewed. For example, when developing requirements documentation, we found that the DOE offices developed either a performance work statement (13 contracts) or a statement of work (seven contracts). The contract files also included varying lists of acquisition milestones, but for each contract we reviewed, we at least identified planned dates for issuing the solicitation and awarding the contract. Such variation is allowed by the FAR and can be dependent upon the scope and complexity of the acquisition.

Table 2 lists the remaining three acquisition planning practices that applied to certain types of contracts in our scope, all of which DOE offices implemented when required.

Table 2: DOE Offices Implemented Three Selected Acquisition Planning Practices Applicable Only to Certain Contracts We Reviewed

|

Practice |

Description |

Extent implemented (number of contracts) |

|

Authorization to use a management and operating (M&O) contract |

Under FAR Part 17, heads of agencies, with requisite statutory authority, may determine in writing to authorize contracting officers to enter into or renew any M&O contract in accordance with the agency’s statutory authority, or 41 U.S.C. chapter 33, and the agency’s regulations governing such contracts. |

6 of 6 |

|

Authorization to use the End State Contracting Model (ESCM) approacha |

According to the Office of Environmental Management’s (EM) End State Contracting Model Program Plan, the ESCM is generally appropriate for cleanup and closure requirements at EM sites, and conversely may not be appropriate for operational and mission support requirements. The plan states that a determination to use this approach should be made through the acquisition planning process for each individual requirement. |

5 of 5 |

|

Approval to use a single-award indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contractb |

FAR Part 16 prohibits single-award contracts for task or delivery order contracts in an amount estimated to exceed a certain threshold—$112 million (including all options) for the contracts we reviewed—to be awarded to a single source unless the head of the agency makes a determination in writing allowing a single award.c |

6 of 6 |

Source: GAO analysis of a nongeneralizable sample of acquisition planning practices selected from Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) requirements and Department of Energy (DOE) policy and guidance, including the Acquisition Guide. | GAO‑25‑106207

aAccording to EM documentation, the ESCM is not a contract type, but an approach to creating meaningful and visible progress through defined end-states, even at sites with completion dates far into the future. The approach relies on single-award IDIQ contracts with associated task orders issued for defined scopes of work; such contract types are typically used when the exact quantities and timing for products or services are not known at the time of contract award.

bIDIQ contracts can be awarded to one or more contractors for the same or similar products or services and are used when the exact quantities and timing for products or services are not known at the time of award.

cOn October 1, 2020, the dollar threshold for single-award IDIQ contracts changed from $112 million to $100 million. Federal Acquisition Regulation: Inflation Adjustment of Acquisition-Related Thresholds, 85 Fed. Reg. 62485, 62488 (Oct. 2, 2020).

Eleven of the 20 Contracts We Reviewed Did Not Have an IGCE Due to Waivers or Use of Other Methods

For 11 of the 20 contracts we reviewed, DOE offices either did not develop an IGCE or developed an IGCE that addressed some, but not all, potential contract costs. DOE’s Acquisition Guide directs procurement officials to conduct an IGCE for procurements with potential contract values above the simplified acquisition threshold, but an IGCE is not generally required by the FAR. Seven contracts we reviewed did not have IGCEs for the following reasons:

· Officials obtained a waiver of the IGCE direction for three contracts. EM obtained approval to waive the IGCE direction for two contracts using the End State Contracting Model (ESCM) approach and one M&O contract. According to an EM directive from August 2023, the IGCE direction may be waived under certain circumstances, such as when a cost realism and reasonableness evaluation can be made using alternative cost and pricing evaluation techniques.[33]

We found that each approved waiver stated that the direction to complete an IGCE could be waived because the solicitations required prospective contractors to propose certain costs, such as estimated costs for the contract transition period and key personnel for the first full year of the contract base period. In addition, the acquisition plans for the two contracts using the ESCM approach state that the total estimated cost of the contract was based on the federal lifecycle baseline for the relevant scope of work to be completed under the contract over 15 years at each respective site.[34] Moreover, EM documentation states that post-award contract activities for ESCM contracts include completing IGCEs for task orders placed under the contracts to ensure that prices are reasonable.[35]

· Officials used a budget-based model for four M&O contracts. Four NNSA M&O contracts in our scope did not develop IGCEs because NNSA used a budget-based model to estimate the contracts’ potential total cost in lieu of an IGCE. Under this budget-based model, NNSA uses planned funding profiles, which are typically based on current budget forecasts and may include historical data, to estimate the contracts’ potential total value for the planned period of performance, inclusive of all options. As a result, an overall estimated total contract value is not determined, with the cost information included in the solicitations serving only as an estimate to be used by prospective contractors in the development of their proposed fees.

For the remaining four of 11 contracts, we found that DOE offices used, or planned to use, other means to estimate costs and price reasonableness. Specifically, we found that:

· Three of the four contracts used EM’s ESCM approach. Similar to the two ESCM contracts previously discussed, under this approach, IGCEs will be completed for specific task orders during the post-award period. Nonetheless, in two cases, DOE developed IGCEs that estimated the costs of the contract transition period and two initial task orders, while in the third case, the IGCE estimated costs only for the contract transition period. Additionally, all three acquisition plans referenced the use of federal site lifecycle baselines to estimate the total cost of each contract.

· For the fourth contract, an EM M&O contract, we found that an IGCE was developed to estimate the costs of the contract transition period. Like the other M&O contracts in our scope, the contract’s potential total cost was budget-based and used historical and forecasted budget data to estimate an annual funding amount for a 10-year period of performance.

DOE Offices Did Not Always Implement Lessons Learned Requirements or Follow a Process That Employs Leading Practices for the Contracts We Reviewed

Our analysis found that DOE offices did not always implement lessons learned requirements that are important to acquisition planning. In particular, we found that DOE offices did not always implement two components of lessons learned leading practices—reviewing prior lessons learned at the start of acquisition planning and documenting potential lessons learned during the planning process.

Requirement to Review and Incorporate Prior Lessons Learned When Planning an Acquisition Was Not Always Implemented

Eight of the 20 contracts we reviewed did not include evidence in the contract files indicating that prior lessons learned were reviewed and, as appropriate, incorporated during the planning phase for these acquisitions. The FAR states that agency heads shall prescribe procedures for ensuring that (1) the contracting officer, prior to contracting, reviews the acquisition history of the supplies and services; and (2) knowledge gained from prior acquisitions is used to further refine requirements and acquisition strategies.[36] The FAR and DOE’s Acquisition Guide direct those preparing an acquisition plan to summarize the technical and contractual history of the acquisition. In addition, for FAR Part 15 acquisitions, which made up most of the contracts in our scope, the guide identifies potential sources of prior lessons learned that could be leveraged during acquisition planning.[37] Specifically, the guide references how lessons learned are to be documented by source evaluation boards (SEB) following the completion of the source selection process and award of a contract for FAR Part 15 acquisitions.[38] The guide also notes that lessons learned for M&O contracts should be documented when acquisition practices that are substantively different from previous practices are used and could potentially be considered for future acquisitions.[39]

DOE’s Acquisition Guide, however, does not provide direction to contracting officials on how or where to document whether lessons learned gained from prior acquisitions affected the requirements or proposed acquisition strategy of the current acquisition, especially for non-M&O acquisitions.[40] In particular, we found that the portion of the guide applicable to all acquisitions, including the non-M&O acquisitions we reviewed, included language from the FAR about using knowledge gained from prior acquisitions when performing market research.[41] However, the guide contains no direction for how or where in the contract files contracting officials should document which prior lessons learned were identified and leveraged when performing market research or other actions for the current acquisition. DOE revised the Acquisition Guide in December 2023, but it does not provide clear direction for what should be included to document which prior lessons learned are relevant and ensure that such institutional knowledge is not lost.[42]

We have previously highlighted how other federal agencies have used acquisition plans as one means to document the review and use of prior lessons learned, even if not required.[43] In particular, our August 2011 report noted that acquisition plans can be used by contracting officials to document lessons learned from previous contracts that affect the current acquisition and ensure that institutional knowledge is not lost. For example, we described in our 2011 report how one agency revised its acquisition planning guidance to direct that acquisition plans document lessons learned from previous acquisitions that impact the current acquisition. Alternatively, the agency may provide a rationale in the acquisition plan for why historical information was not reviewed to obtain lessons learned. However, the practice of using an acquisition plan to document the review of prior lessons learned was not always performed, with half of the acquisition plans we reviewed containing such information. By ensuring that prior lessons learned are reviewed and, as appropriate, incorporated during acquisition planning, some DOE offices may be able to better plan and avoid pitfalls previously experienced throughout the acquisition planning process.

Potential Lessons Learned Identified during Acquisition Planning Were Not Always Documented

The contract files for six of the 20 contracts we reviewed did not include evidence of the documentation of potential lessons learned identified during acquisition planning.[44] Of these six contracts, NNSA awarded three, and the National Energy Technology Laboratory, Office of the Chief Information Officer, and EM each awarded one.

As previously discussed, DOE’s Acquisition Guide outlines a process for collecting and disseminating lessons learned by the SEB after completing the source selection process.[45] In particular, the guide states that the SEB shall document lessons learned for acquisitions whose dollar value exceeds $25 million using a standard template and submit them to DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management.[46] However, we did not locate such documentation in the contract files for six contracts. We made additional requests for such documentation to NNSA and each DOE office and found the following:

· In four cases, officials from NNSA and the DOE offices either affirmed the absence of documentation related to lessons learned or did not provide additional documentation. In one case, DOE did not identify and document any potential lessons learned for an acquisition for work with the Office of the Chief Information Officer, though the award was subsequently terminated after a sustained bid protest. The bid protest decision found that DOE’s award was improper because the agency’s evaluation of the offers resulted in selecting a company that failed to meet the minimum requirements detailed in the solicitation. In another case, officials from the National Energy Technology Laboratory, which awarded one of the four contracts, acknowledged that opportunities exist to improve how lessons learned are being captured. They told us that steps are being taken to ensure the capturing of lessons learned for ongoing and future acquisitions but did not provide any examples.

· In the fifth case, NNSA officials pointed to material related to market research and information that was obtained from industry that we determined to pertain to a preceding acquisition. We did not receive any lessons learned documentation specific to the acquisition included in our scope.

· In the sixth case, EM officials acknowledged that they did not document any lessons learned. They explained that the solicitation for this acquisition was canceled, and the scope of work incorporated into a new acquisition. As a result, the EM officials said that relevant lessons learned identified as part of the canceled acquisition were leveraged in real time during acquisition planning. For example, they said that EM contracting officials made changes when drafting language for the new solicitation for the purposes of minimizing any potential conflicts of interest. The EM officials also noted that lessons learned from the canceled acquisition would be consolidated with lessons identified from the ongoing acquisition.

In cases such as these where potential lessons learned identified during acquisition planning were not documented, DOE and NNSA offices may have missed opportunities to improve acquisition planning based on previously acquired knowledge and experience.

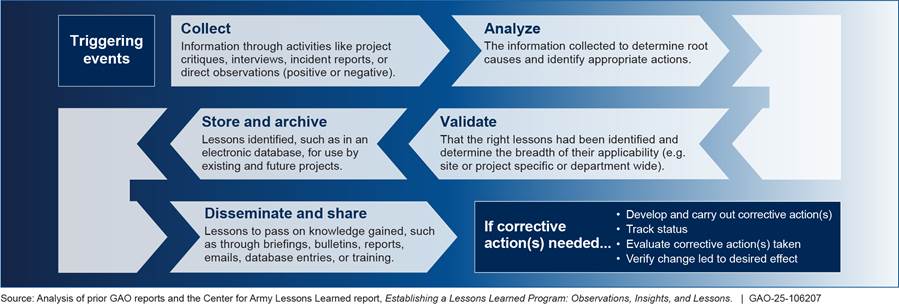

Process Used by Some DOE Offices When Documenting Potential Lessons Learned Identified during Acquisition Planning Does Not Follow Leading Practices

From our review of the lessons learned documentation for the 14 contracts in our scope that implemented the lessons learned practice, we found that DOE’s Acquisition Guide does not fully employ leading practices. Through our body of work, we have found that leading practices for lessons learned are a principal component of an organizational culture committed to continuous improvement.[47] The leading practices include collecting, analyzing, validating, storing and archiving, and disseminating and sharing knowledge gained on positive and negative experiences (see fig. 2). In circumstances where the lessons learned warrant taking a corrective action, the process can also include evaluating and verifying that the corrective action resulted in the desired change in behavior and the lesson was learned.

As previously discussed, the SEB lessons learned process outlined in DOE’s Acquisition Guide focuses on collecting and disseminating lessons learned. The guide also states that DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management maintains a database of submitted SEB lessons learned that is monitored for trends. According to the guide, SEB lessons learned and any trend analysis that exists are to be shared with newly established SEBs. However, the Acquisition Guide’s SEB lessons learned process does not include steps that would align with leading practices for how potential lessons learned identified during the acquisition process are analyzed or validated to ensure that root causes are understood and that the right lessons have been identified. The process also does not address how any corrective actions taken are to be evaluated to verify that the changes have resulted in the desired effects.

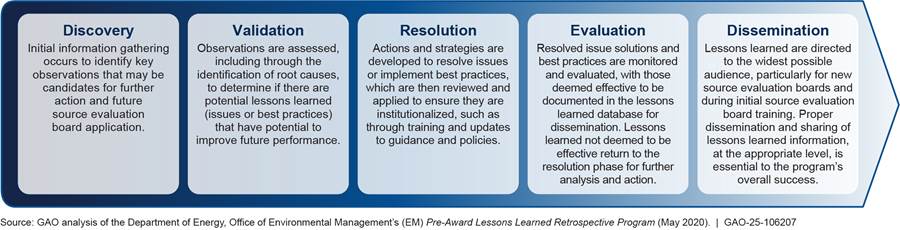

Among the 14 contracts we reviewed for which lessons learned were identified, three followed the process outlined in the Acquisition Guide, while 11 used other approaches. Among these other approaches was EM’s, which we found better aligns with leading practices for lessons learned, more so than the process described by the Acquisition Guide. In particular, we found that:

· DOE offices documented SEB lessons learned for three contracts. For two EM contracts and one Office of Legacy Management contract in our scope, we found that the SEBs followed the Acquisition Guide and developed reports that identified and documented lessons learned from throughout the acquisition process. Some of the identified lessons included ensuring that adequate time is built into the acquisition schedule to allow for sufficient focus on acquisition plan development and adopting a schedule that allows for the tracking of performance against the original schedule.

· NNSA documented lessons learned for three M&O contracts in separate files. We found that NNSA consolidated lessons learned for two M&O acquisitions in a high-level summary document, not the SEB lessons learned template, that focused on presolicitation and solicitations activities. One identified lesson highlighted the need for a strategy improvement to allow for sufficient time to develop a realistic acquisition schedule. Potential lessons learned for a third M&O contract were also documented, but in a less formal manner than the SEB lessons learned template. Some of the lessons recommended simplifying aspects of the proposal and reducing the number of people involved, such as during the proposal evaluation process.

NNSA officials told us that the formality of documenting lessons learned varies depending on the type of procurement, with more formal lessons learned documentation for the larger and more complex procurements. They explained that NNSA does not have any separate guidance or policies from the processes outlined in DOE’s Acquisition Guide, which they cited as the primary source of guidance for the procedures to follow, including the SEB process. Although the guide states that SEB lessons learned shall be documented using a standard template,[48] NNSA officials indicated that lessons learned for M&O contracts are sometimes documented in different ways, including in emails.

· EM documented lessons learned for eight contracts using an office-specific process. We found that eight EM contracts, including one that also developed an SEB lessons learned report, documented lessons learned by following an EM-specific pre-award lessons learned retrospective program. EM’s program, implemented in May 2020, includes five phases, and is intended to ensure that formal procedures are used to effectively capture lessons learned during the acquisition process and, when necessary, act on them to ensure continuous improvement (see fig. 3).[49]

As part of this program, EM officials maintain a database that consolidates the identified lessons and, when applicable, describes the root causes, recommended and actual actions taken to resolve the issue, and whether the actions are completed. Some of the lessons included developing a realistic schedule; ensuring that the SEB chair and voting members have the appropriate technical expertise to evaluate proposals against scope requirements; and drafting the evaluation criteria included in a solicitation to ensure it is specific to what the government intends to evaluate. EM’s evaluation of several of the documented lessons resulted in corrective actions, including the implementation of a standard acquisition schedule template that can be more readily assessed to determine whether the schedule is realistic and credible.

EM documentation states that its pre-award lessons learned program builds upon the manner in which EM historically captured lessons learned through the SEB lessons learned process. Based on our prior work examining leading practices for a lessons learned process and compared to the process outlined in DOE’s Acquisition Guide, we found that EM’s program more closely reflects the activities typically performed as part of a lessons learned process employing leading practices, as described in figure 2 above.

EM officials with whom we spoke said that their office coordinated with DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management to highlight their lessons learned program at a brown bag attended by officials from across the department. Although the presentation was attended by officials from across the department, as of January 2024, no other offices in the department had reached out to EM to learn more about the program. While DOE’s effort to ensure that SEBs document lessons learned is positive, our review of 20 DOE and NNSA contracts shows that the Acquisition Guide’s existing process does not address or incorporate all the types of leading practices of a lessons learned process, though EM’s program does.

Further, we found that the existing process is not always completed or followed consistently. For example, in one case, DOE did not document any potential lessons learned that could have reinforced how to evaluate requirements as outlined in the solicitation. Yet, in another case, after a similar issue was identified, steps were taken to document the issue, its root cause, and a recommended corrective action. These additional actions resulted in the development of additional training that is provided prior to evaluating offers from prospective contractors. Developing a process that incorporates leading practices and then using it consistently across DOE and NNSA would help ensure that potential lessons learned identified during acquisition planning, as well as other phases of the acquisition process, will be documented. This will also help ensure that, in certain cases, corrective actions will be taken to improve acquisition planning and other processes.

DOE Does Not Have Readily Available Data on Extent of Canceled Solicitations, Contract Award Terminations, and Award Delays

DOE does not have readily available data on the number and value of canceled solicitations and terminated contract awards for fiscal years 2017 through 2022 in its contract database (i.e., STRIPES). For the canceled solicitations and terminated awards that we identified, changes to requirements were the most common reason reported for the cancellation or termination. Further, DOE does not track data on contract award delays, although it reported having implemented our 2006 recommendation to do so.[50] Given cancellations, terminations, and delays can be costly to DOE and its industrial base, it is important to have reliable information on cancellations, terminations, and award delays as a key step to understand the extent of these situations, assess root causes, and take any necessary corrective actions. This is particularly important given the potential negative consequences to DOE and its industrial base.

STRIPES Has Incomplete, Inconsistent Data on Canceled Solicitations and Terminated Awards

Reviewing multiple data sources, we identified incomplete and inconsistent DOE data for fiscal years 2017 through 2022 on canceled solicitations and terminated awards. Specifically, we identified canceled solicitations and terminated awards from other sources that were not captured in DOE’s STRIPES contract data (see fig. 4). The canceled solicitations we identified from other sources had an estimated total value of $40.7 billion, and the terminated awards had a total value of $169 million. In contrast, DOE’s STRIPES contract data accounted for $211 million in cancellations and $23.07 billion in terminations for the same period.

Figure 4: Number of Canceled Solicitations and Terminated Awards Identified in the Department of Energy (DOE) Procurement System and Other Sources, Fiscal Years 2017–2022

DOE Officials Do Not Consistently Maintain Data on Canceled Solicitations

DOE’s procurement data did not identify all canceled solicitations that occurred between fiscal years 2017 through 2022, as the data were missing important information and procurements. DOE captures information on solicitations in its STRIPES database, the main procurement data system for the agency that also links to public websites such as SAM and FPDS. However, our review found key information related to procurement value was missing, and the data also did not include records for some canceled solicitations, which we identified through other sources.

There is no designated process or data field in STRIPES that indicates if a solicitation is canceled. To provide us with records on canceled solicitations, DOE officials used a word search of selected fields in STRIPES to identify potential records in the scope of our review. This produced 142 records for further review. However, of the 142 records provided by DOE, we found that 126 were missing information on the estimated value of the contract. DOE officials told us that this information is not always entered in STRIPES, but would be included in other contract documents, necessitating manual review of documents.

Due to the missing contract value information and the need to manually review additional documents to identify relevant cancellations, we selected several offices with a total of 66 canceled solicitation records in STRIPES potentially in the scope of our review.[51] Out of the 66 canceled solicitations for which we reviewed contract documents, we identified nine canceled solicitations that were valued at $5.5 million or more and fall within the scope of our review; the total combined value of these procurements was about $211 million.

In addition to the nine procurements in the STRIPES data, we identified three cases of canceled solicitations that were not included in the data. DOE officials told us that they expect contracting officers to record canceled solicitations, but there can be cases where information is not reported in STRIPES. We identified these canceled solicitations in other DOE documents and media reports because they were large dollar and high-profile procurements, including

· Pantex Plant and Y-12 National Security Site Combined M&O contract. NNSA issued a solicitation for the combined M&O contract for the Pantex and Y-12 sites in November 2020, and an award was made in November 2021. Subsequently, the award was protested in December 2021, and NNSA announced it would take corrective action to address the protest. As a result, NNSA terminated the award and canceled the solicitation in May 2022 and then announced a decision to award separate M&O contracts for the sites due to the changing scope of work and other factors.

· Savannah River Site Liquid Waste Services contract. EM planned to award this contract for liquid waste stabilization and disposition activities by March 2017 given that the incumbent contract was ending in June 2017. EM awarded the contract in October 2017, but a subsequent bid protest was sustained. EM decided to cancel the solicitation in February 2019 related to decisions to substantively change the scope of work under the contract. EM later moved this scope of work into a new procurement, the Integrated Mission Completion Contract, which was awarded in October 2021.

· Hanford Tank Closure contract. EM issued an RFP in February 2019 for this procurement, related to tank waste management and retrieval operations, and awarded the contract in May 2020. Subsequently, a bid protest was filed by an offeror, and DOE announced a corrective action to address the protest and suspended the award in August 2020. In December 2020, DOE then canceled the solicitation due to decisions to change the scope.

Officials confirmed that these procurements were not included in the data and told us that solicitations are not amended once an award is made, even if the solicitation is subsequently canceled. However, we also identified a solicitation for a WAPA procurement in which an award was made, subsequently terminated, and then the solicitation was canceled, all of which was recorded in STRIPES. These differences in recording information in STRIPES highlight the inconsistency in how officials recorded canceled solicitations. Furthermore, as the official procurement system, the STRIPES system did not capture complete and accurate information on all canceled solicitations.

Overall, through our review of data sources, we identified at least 12 canceled solicitations in the scope of our review with a total estimated value of about $40.9 billion. Table 3 includes information on the canceled solicitations by office or program.

|

Office |

Number of canceled solicitations |

Dollar value of procurements |

Data source(s) |

|

National Nuclear Security Administration |

6 |

$23 billion |

DOE data, media reports |

|

Office of Environmental Management |

2 |

$17.7 billion |

Media reports |

|

Western Area Power Administration |

2 |

$86.9 million |

DOE data |

|

DOE Headquarters |

2 |

$25.6 million |

DOE data |

|

Total |

12 |

$40.9 billion |

|

Source: GAO analysis of DOE data. | GAO‑25‑106207

We also found that officials did not maintain certain contract documents for canceled solicitations. For example, EM did not have any documentation, including estimated contract value, for two of the five solicitations listed in the STRIPES data associated with the office. Similarly, for one NNSA procurement, officials had no estimated value, as that documentation was missing from the contract file and the contracting officer was no longer with NNSA. In another NNSA example, a solicitation did not have documentation of the reason for the cancellation because the contracting officer had left the agency, according to NNSA officials. According to the FAR, agencies should establish and maintain contract files for canceled solicitations, to include information to support decisions made and actions taken related to the procurement.[52] It is important to have reliable information on cancellations to better track their extent and take any necessary actions that might prevent their occurrence.

Information on Terminated Awards Was Inconsistent across Procurement Systems

We found that data on award terminations are not consistently recorded, though there are designated data fields to capture this information in STRIPES and FPDS, the system of record for federal procurement data. We reviewed several data sources for information on terminated awards that occurred from fiscal years 2017 through 2022, and we obtained different results for terminated awards from FPDS versus from our request from DOE for terminations from STRIPES. Similar to the canceled solicitations data, DOE officials pulled data from STRIPES using a word search of selected fields, and this produced different results between the datasets. We identified five terminated awards using the designated data field in FPDS data, and one of these awards also appeared in the STRIPES data; the other four did not. However, the STRIPES data included an additional three terminated awards that did not appear in the FPDS data because the reason for modification field did not indicate a termination. Instead, the STRIPES records were coded as a funding action (two records), or an administrative action (one record). When asked about the inconsistencies in the use of the modification field to indicate a termination, DOE officials told us the contracting officer may have used their professional judgment to select the most appropriate reason in cases where a modification included multiple actions. However, indicating a termination in a field other than the modification field would generally limit the accessibility of termination information in FPDS.

The combined results of our review of these data sources identified eight contract award terminations in the scope of our review with a total value of about $23.2 billion. The combined Pantex and Y-12 M&O contract made up about 99 percent of this value. Table 4 includes information on the terminations by office, including the source of the information.

Table 4: Terminated Awards by Department of Energy (DOE) Office, Fiscal Years 2017–2022 (value of at least $5.5 million and terminated shortly after award)

|

Office |

Number of terminated awards |

Dollar value of terminated awards |

Data source(s) |

|

National Nuclear Security Administration |

2 |

$23 billion |

DOE and FPDS data |

|

DOE Headquarters |

3 |

$124.4 million |

FPDS data |

|

Western Area Power Administration |

1 |

$80 million |

DOE and FPDS data |

|

Office of Nuclear Energy |

2 |

$55.9 million |

DOE data |

|

Total |

8 |

$23.2 billion |

|

Source: GAO analysis of data from DOE and the Federal Procurement Data System. | GAO‑25‑106207

In addition to the awards identified above, there were two EM procurements, the Savannah River Site Liquid Waste Services and Hanford Tank Closure contracts, that had canceled solicitations after awards were made, but EM officials did not provide evidence that the contracts were terminated for convenience as defined by the FAR. For the Savannah River Site Liquid Waste Services contract, EM officials told us that they did not execute a termination for convenience and used alternate methods to close out the awarded contract. They also said that ending an award through a close out rather than termination may help avoid certain costs associated with a termination, such as settlement costs. For the Hanford Tank Closure contract, officials told us in June and July 2024 that the contract was not terminated but instead closed out using other methods, similar to the Liquid Waste Service contract. However, in its technical comments on a draft of this report, provided to us in October 2024, DOE stated that the contract was terminated for convenience, but did not provide evidence to support this reversal. Further, we reviewed FPDS data and found that in June 2024, EM ended the Hanford Tank Closure contract through a “close out” modification while also terminating the contract’s first task order for convenience.

As with canceled solicitations, DOE officials told us they rely on contracting officers to properly record a termination. These officials acknowledged, however, that there may be cases where the information is not properly recorded, despite agency requirements to report contract information in designated procurement data systems. For example, the combined Pantex and Y-12 M&O contract did not appear in the termination data we obtained through FPDS because the termination was not recorded using the “reason for modification” field. While the termination of this procurement was noted in text fields in STRIPES, this data would not be easily accessible in FPDS. Officials corrected this issue after we pointed it out by submitting a new modification in FPDS in April 2024, with termination listed in the reason for modification field.

Our review of DOE and office requirements and guidance found very little instruction about how to record and report contract terminations. When asked about this, officials pointed to the FAR and FPDS user manuals as guidance for contracting officers related to terminations. Regarding the quality of procurement data, our Framework for Assessing the Acquisition Function at Federal Agencies discusses the importance of data stewardship to ensure that data captured and reported are accurate, accessible, timely, and usable for acquisition decision making and activity monitoring.[53] In addition, according to federal internal control standards, management should use quality information to achieve the entities’ objectives.[54] However, we found that DOE does not have guidance related to recording terminations in STRIPES and does not consistently capture complete information on terminated awards in STRIPES.

The Primary Reason for Cancellations and Terminations Was Changes to Requirements, Affecting Both Government and Industry Interests

Changes to requirements were the most common reason reported for solicitation cancellations and award terminations for the procurements in the scope of our review. We identified a total of 18 procurements with a total estimated value of $41.1 billion that involved a solicitation cancellation or award termination, or both, and changes to requirements or poorly defined requirements were involved in 14 of these procurements based on our review of contract documents.[55] These 14 procurements accounted for $41 billion, which is 99.8 percent of the estimated value of all cancellations and terminations we identified, as shown in table 5.

Table 5: Department of Energy (DOE) Procurements with Cancellations or Terminations Related to Requirements, Fiscal Years 2017–2022 (value of at least $5.5 million)

|

Office |

Number of procurements |

Estimated dollar value of procurements |

|

|

National Nuclear Security Administration |

5 |

$23.0 billion |

|

|

Office of Environmental Management |

2 |

$17.7 billion |

|

|

DOE Headquarters |

3 |

$125.6 million |

|

|

Western Area Power Administration |

2 |

$86.9 million |

|

|

Office of Nuclear Energy |

2 |

$55.9 million |

|

|

Total |

14 |

$41.0 billion |

|

Source: GAO analysis of data from DOE and the Federal Procurement Data System. | GAO‑25‑106207

Some of the procurements with requirements changes in the various DOE offices include the following:

· For an NNSA procurement for specialized vehicles in 2022, officials determined that they needed to change requirements in the solicitation to increase competition, including changes to the structure of the contract award and time frames. As a result, they canceled the existing solicitation after receiving one bid. In another example, from May 2022, NNSA announced that it would cancel the contract solicitation for the combined M&O contract for Pantex and Y-12 that was awarded in November 2021, stating that the agency intended to hold new competitions for separate contracts at each site. NNSA reported that separating the contract would be in the best interest of the government due to increasing work at the sites and the challenging geopolitical environment.

· In 2022, DOE’s Headquarters Procurement Services office awarded a contract for cybersecurity services, but this award was subsequently subject to a successful protest that found that DOE had not followed the requirements from its solicitation in evaluating and awarding the contract. As a result, DOE had improperly awarded the contract to a firm that failed to meet material solicitation requirements. This outcome suggests that requirements were not well defined since a firm was evaluated as capable of performing the work even though it did not meet solicitation requirements. For another procurement related to information technology support services, Headquarters Procurement Services officials canceled the solicitation in July 2017 after significant program requirement changes necessitated changes to the acquisition strategy.

· After awarding the Savannah River Site Liquid Waste Services contract in 2017, EM subsequently canceled the solicitation after a successful bid protest. Officials determined it was in the best interest to cancel the procurement and pursue a new solicitation with a materially different requirement, including expansion of scope and pivoting to a contract structured according to the ESCM approach. Similarly, the Hanford Tank Closure contract was awarded in 2020 by EM but was subsequently protested. DOE filed a notice of corrective action to address the protest. Agency officials then canceled the solicitation based on the decision to make changes to the scope and switch to an updated ESCM approach for the contract.

· In 2018, WAPA officials canceled a solicitation after agency officials received bids with wide variances. Officials reviewed the procurement and determined there were likely flaws in the requirements documents and IGCE that necessitated a re-evaluation of requirements. For another WAPA contract, a need to change the technical requirements in the original solicitation was identified when responding to a bid protest. Because offerors could not meet the requirements in the original solicitation, the award was terminated, and the solicitation was amended.

When we asked DOE procurement officials if they had assessed or evaluated the issue of requirements definitions in procurements, given the prevalence of requirements changes in cancellations and terminations, DOE officials were not aware of any such study. DOE procurement officials added that there is a shortage of contracting staff overall that would make it difficult to use scarce resources for that type of review. Officials also pointed out that the program side owns the requirements and has primary responsibility for setting the requirements of the procurement. Additionally, officials told us that circumstances may change while waiting for an award to be finalized because of the length of time to make awards, which can result in changes to requirements. They said this may occur particularly when a solicitation or an award is protested, which occurred in seven of the 18 procurements we identified that involved a canceled solicitation or terminated award. Yet, a study of the contribution of requirements changes to cancellations and terminations may reveal whether these outcomes could be reduced through improved requirements planning.

We reviewed lessons learned documentation for four of the 14 procurements with cancellations or terminations related to requirements and for which we had contract documents. Similar to our findings above, we found that the lessons learned process described in DOE’s Acquisition Guide was not used consistently for these four procurements. In particular, we did not identify any documented lessons learned in the contract files for two of the four contracts. The other two contracts did not have lessons learned related to requirements definitions. As we noted previously, potential lessons learned should be documented as part of a lessons learned process that follows all leading practices to ensure that opportunities to improve the acquisition process are not lost. This would seem particularly relevant in cases where a procurement faced problems that ultimately led to a canceled solicitation or terminated award and involved a foundational issue such as requirements stability.

Defining requirements is a key acquisition planning element to help ensure the success of an acquisition. We have reported in the past that requirements instability or poorly defined requirements can result in increased costs and schedule delays for programs.[56] Although DOE implemented acquisition planning practices related to requirements documentation, as discussed in the previous objective, the prevalence of cancellations and terminations that occurred due to requirements changes point to potentially fundamental problems in DOE’s acquisition planning. These problems can negatively impact a procurement, as well as the agency and industry involved in that procurement.

DOE officials told us that canceled solicitations and terminated awards are the exception and not common, but there are times when the agency determines that they are necessary. DOE commits resources to successfully awarding contracts but may also determine that it is in the best interest of the government to cancel a solicitation, according to officials. Yet, officials also told us that delays in the procurement process, such as from cancellation of a solicitation, may impact achieving mission requirements.

We spoke to representatives from 10 selected industry entities, including contractors and organizations that represent DOE contractors, about their experiences with canceled solicitations and terminated awards and how cancellations and terminations affect their companies. According to representatives from nine of the 10 industry entities we interviewed, cancellations and terminations may result in financial losses and lost productivity for key personnel and may ultimately impact their interest in future contracts. For example:

· Costs to prepare a bid proposal can be millions of dollars, and the cancellation of a solicitation means this money was in effect wasted. Two industry representatives also pointed out that there are government resources wasted in these cases as well.

· Key personnel are a very important factor for procurements, as the quality of key personnel is often an important evaluation criteria for the award. Almost all industry representatives (eight of 10) told us that companies start to line up their key personnel very early, well before an RFP is issued by DOE. The key personnel included in the bid must be reserved for that contract and are effectively “on the bench” until an award decision is made. As a result, canceled solicitations can have a significant impact on the availability of key personnel, such as their ability to work on other important projects. Representatives also reported that it is expensive to keep the personnel waiting for the actual contract to begin, as they are carried as overhead. Additionally, it can be frustrating for the careers of key personnel, and employees may leave if they are kept off substantive projects for too long such as in cases of procurements that are beset with delays, cancellations, and terminations.