MILITARY HOUSING

DOD Should Address Critical Supply and Affordability Challenges for Service Members

Report to Congressional Committees

October 2024

GAO-25-106208

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106208. For more information, contact Alissa H. Czyz at (202) 512-3058 or CzyzA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106208, a report to congressional committees

October 2024

MILITARY HOUSING

DOD Should Address Critical Supply and Affordability Challenges for Service Members

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD’s policy is to ensure that service members and their families have access to affordable, quality housing. About two-thirds of service members in the U.S. live off base in local communities. In recent years, the country has faced rising housing costs and increasingly competitive housing markets.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 includes a provision for GAO to review military housing in areas with limited housing supply. Among other issues, this report examines the extent to which DOD (1) assesses the availability of private-sector housing for service members; (2) assesses the potential financial and quality-of-life effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on service members; and (3) coordinates with communities surrounding installations on local housing issues.

GAO reviewed DOD policies and documentation; interviewed DOD housing officials; held discussion groups with service members; performed statistical analyses; and conducted a survey of local government officials in areas near military installations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including that DOD develops a comprehensive list of critical housing areas, obtains feedback on effects on service members living in such areas, and updates guidance on coordinating with local communities. DOD concurred with these recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense (DOD) does not use its housing assessments to identify a comprehensive list of areas where service members and their families are most severely affected by housing supply or affordability challenges—or critical housing areas. DOD’s policy is to rely primarily on the private sector to house service members. DOD officials provided GAO with some information about areas with limited housing availability from multiple sources within the department. However, the information provided was not comprehensive, and the analyses do not account for factors such as unavailability of units in areas with high numbers of vacation rentals. By identifying a comprehensive list of critical housing areas, accounting for the unique circumstances of various areas, DOD would be better able to make informed housing decisions.

DOD collects some information but does not routinely assess the negative financial and quality-of-life effects that limited supply or unaffordable housing has on affected service members. During GAO visits to selected DOD sites, some service members reported having to take on debt or commute long distances to afford quality housing. By consistently obtaining feedback from service members, DOD would be more aware of the extent of the effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on its service members and be better positioned to identify critical housing areas.

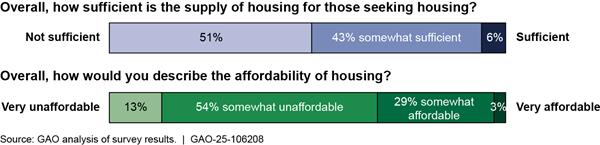

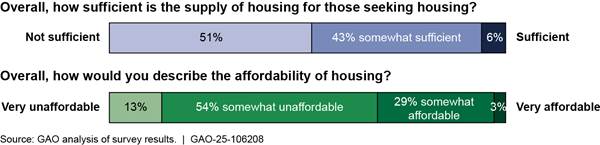

DOD encourages coordination with communities near military installations on local housing issues, but DOD does not have clear guidance on how installation leadership should coordinate with local communities on housing. Accordingly, GAO found differences in the processes for and the extent to which installations had pursued coordination to address housing challenges. GAO’s statistical analyses found that counties with higher military populations were associated with having higher median rents. Further, the majority of respondents (67 percent) to GAO’s survey of about 150 local government officials from selected locations near military installations said they believed they had somewhat or very unaffordable housing (see figure). If DOD were to provide clearer guidance on coordination with local communities, it could lead to better partnerships that could improve housing affordability and availability for service members and other residents within local communities.

Survey Response Frequencies from Local Government Officials Regarding Overall Housing Supply and Affordability

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

BAH basic allowance for housing

COLA cost-of-living allowance

DOD Department of Defense

HRMA Housing Requirements and Market Analysis

NDAA National Defense Authorization Act

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense

October 30, 2024

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chairman

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

Department of Defense (DOD) policy states that the department should ensure eligible service members and their families have access to affordable, quality housing.[1] About one-third of service members in the United States live in on-base housing, either in government-owned housing—such as barracks or dorms—or in military family housing that is owned and operated by private companies.[2] On-base housing is provided by the government at generally no cost to the service member.[3] In its policy, DOD acknowledges that it relies on the private sector to house the remaining two-thirds of service members and their families in the communities surrounding military installations.[4] Service members who live in off-base private-sector housing use housing allowances to help cover a portion of the monthly costs of rent (or a mortgage) and utilities.

Millions of Americans experience difficulties with obtaining housing due to affordability challenges and limited supply. Housing costs have increased steadily since 2012 and have risen sharply since 2020. As a result, housing affordability has decreased for most renter households, with the poorest households facing the most severe affordability challenges. In 2022, an estimated 50 percent of renter households were considered “cost-burdened” because they paid more than 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.[5] In addition, housing unit production fell dramatically during the 2007-2009 financial crisis and has been slow to recover since. In 2021, the number of new privately-owned housing units started nationwide surpassed a total of 1.5 million for the first time since 2006.

Since 1998, we have conducted various reviews related to military housing and reported on concerns regarding affordability and quality of housing for service members. In 2021, we identified concerns related to DOD’s ability to provide support services at remote or isolated installations, including access to affordable, quality housing.[6] We recommended that DOD develop policy and assess risks related to support services at these installations, and it has implemented those recommendations. We also reported in 2021 that DOD’s process for setting housing allowance rates did not result in amounts necessary to cover the cost of suitable housing for service members.[7] We recommended that DOD assess its process for setting those rates and update relevant guidance, and it has implemented these recommendations. In 2023, we reported on challenges related to appropriate oversight of privatized military housing and military barracks and recommended that DOD take steps to improve oversight.[8] DOD concurred or partially concurred with these recommendations but has not implemented most of them as of October 2024.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2022 includes a provision for us to review DOD’s management of military housing in areas with limited housing supply.[9] Specifically, we reviewed the extent to which DOD (1) assesses the availability of private-sector housing for service members; (2) assesses the potential financial and quality-of-life effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on service members; (3) responds to the effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on service members; and (4) coordinates with communities surrounding installations on local housing issues.

To address all of our objectives, we reviewed relevant DOD and military service policies, guidance, and other documents related to the department’s housing programs at domestic installations within the United States. We interviewed Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and military service officials, among others. We also selected and visited a non-generalizable sample of seven installations, some virtually and some in person, where we interviewed installation leadership, housing officials, and representatives from privatized housing companies that partner with DOD and toured on-base privatized housing communities.

To determine how DOD assesses the availability of housing, we examined DOD’s most recent Housing Requirements and Market Analysis (HRMA) reports for military installations across the United States. We compared the processes and frequency for developing these assessments against relevant DOD and service guidance and statutory requirements in the James M. Inhofe NDAA for Fiscal Year 2023.[10]

To determine how DOD assesses the financial and quality-of-life effects of housing on service members, we compared DOD’s efforts to obtain this information—such as through surveys—against relevant DOD and service guidance, among other criteria. We conducted 15 discussion groups with selected service members of varying ranks living both on and off base to discuss their experiences with housing. We identified strategies DOD may use to address the effects of unavailable and unaffordable housing and compared the use of these strategies against relevant DOD and service guidance, to include DOD’s Military Compensation Background Papers, which state that military compensation should be based on certain underlying principles, including equity and fairness.

To assess DOD’s coordination with local communities on housing, we compared efforts as well as service and DOD guidance against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government. We also estimated statistical models to determine if there were associations between military presence in a geographic area and outcomes on the local housing market. In addition, we developed and conducted a survey of local government officials near military installations across the United States, including Alaska, Hawaii, and Guam. Our survey included questions on local housing market conditions, the perceived effects of the military’s presence on local housing markets, and the level of coordination between military and local government officials, among other topics. See appendix I for a detailed description of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2022 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Types of Housing for Service Members

· Private-sector housing. DOD relies on the private sector to house about two-thirds of service members and their families living in the United States. Private-sector housing is housing, such as apartments and homes, in the local communities near installations (i.e., not DOD-owned housing). Eligible service members receive a housing allowance to contribute toward the cost of private-sector housing in the local community.[11]

· Privatized military housing. In 1996, as part of an effort to improve the quality of military housing, Congress enacted the Military Housing Privatization Initiative, which provided DOD with authority to rely on private housing companies to operate, construct, repair, and renovate military family housing.[12] Since then, private housing companies have primary responsibility for approximately 99 percent of military family housing in the United States.[13]

The military departments have flexibility to structure their privatized housing projects, but typically the military departments lease land to the private housing companies for a 50-year term and convey existing housing located on the leased land to the private company for the duration of the lease. The private company then becomes responsible for operating, maintaining, renovating, repairing, and constructing new housing and for the daily management of the housing units. The private company receives housing allowance payments from the service members residing in the housing.

· Government-owned and leased housing. DOD continues to own, operate, and maintain (1) most barracks and (2) family housing overseas. In some cases, DOD may also lease housing in the local communities surrounding installations to provide to service members.

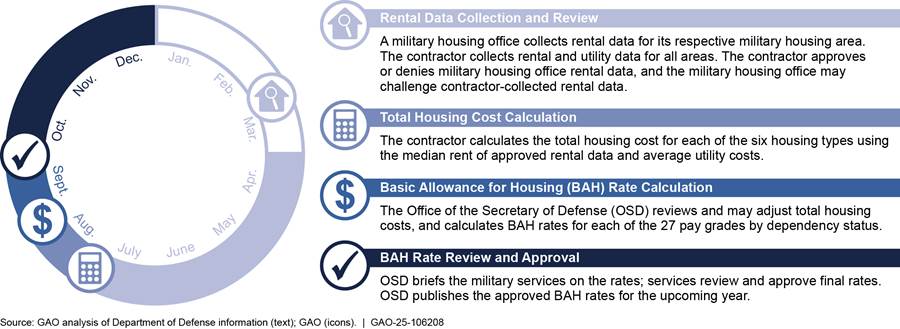

DOD Housing Allowances

Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH). The BAH is designed to enable service members to live off base comparably to their civilian counterparts by providing a fair housing allowance to help cover a portion of the monthly costs of rent and utilities. It is one of the largest components of cash compensation for military personnel, second only to basic pay.[14] Unlike landlords in the private-sector housing market, privatized military housing developers generally are prohibited from charging more for rent than the BAH rate. Therefore, if a service member lives in privatized military housing, the rent is typically equivalent to BAH. Service members who choose to live in private-sector housing rather than in privatized military housing may apply their BAH toward a mortgage or rental payment. They are permitted to keep any portion of BAH not spent on housing and, conversely, have to use other funds to pay housing costs that exceed their BAH. See appendix II for details on DOD’s data collection and rate setting process for BAH.

Overseas Housing Allowance. The overseas housing allowance is a cost-reimbursement for service members assigned to permanent duty overseas that allows them to lease privately owned housing. It includes three separate components: rent, utilities/recurring maintenance, and a move-in housing allowance. Rental allowances are computed using actual rent payments as reported through local finance systems. Service members are reimbursed for rent up to the amount of the lease or the maximum rental allowance, whichever is less.

Roles and Responsibilities for DOD Housing Programs

OSD and each of the military services have roles and responsibilities in overseeing DOD housing programs.

OSD roles and responsibilities. The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2020 directed the Secretary of Defense to designate a Chief Housing Officer, and the James M. Inhofe NDAA for Fiscal Year 2023 directed that this position be held by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment.[15] The Chief Housing Officer is responsible for the oversight of all housing and the creation and standardization of housing policies and processes.[16] These include procedures related to privatized housing, private-sector housing, government-owned or controlled housing, and housing-related relocation and referral services.[17] In addition, the Chief Housing Officer is to develop policy related to the availability of safe and affordable housing located on and off remote and isolated military installations.[18] According to DOD documentation, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Housing (within the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment) supports the Chief Housing Officer in all statutorily defined duties. Additional OSD offices also have responsibilities related to DOD housing programs. These include:

· The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment is responsible for overall policy making and oversight responsibility for DOD real property, including housing, and for establishing overarching guidance and procedures for managing and disposing of real property.[19]

· The Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness is responsible for overseeing the determination of housing allowances and for monitoring morale and welfare aspects of quality-of-life programs, including housing.

· The Under Secretary of Defense, Comptroller is responsible for providing guidance and procedures on financing, budgeting, and accounting for DOD housing programs.

Military service roles and responsibilities. The military services are responsible for managing their respective housing programs. These responsibilities include determining DOD housing requirements for each installation, exercising oversight of the management of privatized housing, and establishing criteria to determine which service members are required to live in DOD housing.

Further, military installations’ commanders and housing offices have defined roles for managing housing programs. Installation commanders are to ensure all service members have access to suitable housing and services; manage, operate, and maintain government-owned housing units; and provide assessment of privatized housing. Military housing offices manage government-owned or controlled housing, conduct oversight of privatized housing companies, and provide information on available private-sector housing to incoming service members and their families.[20] Further, these offices participate in the collection and review of information about housing within the market area and in BAH data collection.

DOD Assessments of Housing Availability for Military Installations

DOD’s guidance on housing management (the DOD housing manual) requires that the military services perform housing requirements and market analysis (HRMA) for their respective installations to determine whether there is enough housing in the area to accommodate the needs of the military at an installation. The HRMA is a structured analytical process that is to assess both the availability and suitability of the private sector’s rental market, assuming specific standards related to affordability, location, features, and physical condition, and the housing requirements of the installation’s total military population.[21] HRMAs are to include an assessment of current and projected economic trends that could affect housing supply and demand in the market area including trends in population, employment, and housing. DOD uses a contractor to collect the data and perform the analyses.[22]

The American Community Survey’s vacancy rates are used as part of HRMAs.[23] Vacancy rates refer to the percentage of units available for new occupants.[24] Very low vacancy rates tend to indicate that demand for housing is higher than the existing level of inventory can accommodate. Vacancy rates have decreased since the housing market crash and financial crisis of 2007-2009, followed by additional decreases during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.[25] This has resulted in housing vacancy rates that were at or near historic lows across rental and owner-occupied housing as of May 2022, which reflects decreasing housing availability. As of April 2024, the nationwide vacancy rate in the United States for rental housing was about 7 percent and less than 1 percent for owner-occupied housing, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The availability of suitable housing in the defined market area is based on information collected through a variety of military and public sources, including housing market area surveys, U.S. Census Bureau data, local government agencies, local real estate professionals, and residents within the market area. Additionally, installation commanders and military housing offices are encouraged to participate in the collection and review of information about the availability and condition of the housing within the market area and recommend suitable housing options for service members.

DOD Does Not Consistently Assess the Availability of Private-Sector Housing or Identify Areas with Critical Supply and Affordability Challenges

The military services have not consistently completed HRMAs to assess private-sector housing availability in a timely manner, and DOD was late in fulfilling a statutory requirement to submit to Congress the military services’ plans for completing HRMAs for fiscal years 2023 and 2024. In addition, DOD does not use its housing assessments and other information to identify and regularly update a comprehensive list of military housing areas with critical availability and affordability challenges. As a result, DOD has limited information on areas in which housing availability and affordability challenges most severely affect service members and their families.

The Military Services Have Not Consistently Assessed Private-Sector Housing Availability

The military services use HRMAs to determine housing availability in areas around installations. However, they have not consistently assessed private-sector housing availability in a timely manner or used these assessments to make informed housing decisions.

Timeliness of HRMAs. The DOD housing manual states that HRMAs must be performed “within a minimum 4-year interval” and must be updated as necessary to reflect major changes in military force structure or changes to the local community that could significantly alter the interaction of supply and demand forces. However, this guidance does not clarify whether HRMAs must be conducted no less than every 4 years or at most every 4 years.

Without clear OSD direction on the required frequency for HRMAs, the services have generally followed their own guidance for conducting HRMAs. Each service’s guidance requires different frequencies for HRMAs, which range from every 3 years to every 6 years, or as needed. As a result of differing requirements in guidance, the frequency with which the services have conducted HRMAs has varied, and some HRMAs are outdated. For example, when we asked the services to provide the most recent HRMAs for all installations in February 2023, the age of HRMAs we received varied by service (see table 1).

Table 1: Percentage of Housing Requirements and Market Analysis (HRMA) Reports by Age Grouping for Each Service

|

|

Military service |

|||

|

Age of HRMA reporta |

Army |

Air Force |

Navy |

Marine Corps |

|

5 or fewer years old |

86% |

5% |

100% |

73% |

|

Between 5 and 10 years old |

9% |

6% |

0% |

13% |

|

Greater than 10 years old |

5% |

89% |

0% |

13% |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD HRMAs. | GAO‑25‑106208

Note: The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 required the military services to complete HRMAs at least every 5 years. We received and reviewed HRMAs for 180 installations in the United States, including Alaska, Hawaii, and Guam. Of those, 56 were Army; 63 were Air Force; 46 were Navy; and 15 were Marine Corps. Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number and therefore may not add up to 100 percent.

aWe determined the age of each HRMA we reviewed by comparing the date we received them to the publication date of each HRMA.

As shown in the table above, Navy HRMAs we reviewed were no more than 5 years old. However, housing officials at Naval Air Station Key West told us even an HRMA conducted as recently as 2021 was outdated given rapid changes in the local housing market in their area. Similarly, officials at Marine Corps Base Hawaii told us the existing HRMA accurately reflected housing requirements at the time the HRMA was conducted in 2018, but the age of the HRMA limited the installation’s ability to effectively plan for more updated housing requirements. Both Naval Air Station Key West and Marine Corps Base Hawaii have recently had or will soon have new HRMAs conducted, according to Navy and Marine Corps officials.

In an effort to standardize the frequency with which the services conduct HRMAs, the James M. Inhofe NDAA for Fiscal Year 2023 required all military services to conduct HRMAs for every installation by 2027 and to complete HRMAs at least every 5 years.[26] Officials from all services told us they were currently conducting HRMAs to fulfill these requirements. However, OSD has not updated the department’s guidance on the frequency of HRMAs to reflect this statutory requirement, and OSD officials told us its housing guidance is outdated.

Submission of Plans for HRMAs. The James M. Inhofe NDAA for Fiscal Year 2023 required the secretaries of the military departments to submit the military services’ plans for HRMAs to be completed in fiscal year 2023 no later than January 2023. It also required the Secretary of Defense to submit the military services’ plans for HRMAs to be completed in each fiscal year, beginning in fiscal year 2024, as part of the department’s annual budget request for each year.

However, while OSD received information from the military departments on the HRMAs planned for fiscal years 2023 and 2024, as of July 2024 it could not confirm that these HRMAs have been or will be completed in the identified time frames, according to an OSD official.[27] This official told us in July 2024 that, because OSD had not verified its information regarding these HRMAs was up to date, neither the military departments nor the Secretary of Defense had submitted this information to Congress, as required. The official added that, because HRMAs are not visible to OSD in DOD’s Enterprise Military Housing system, OSD must instead request each HRMA from the services, limiting its ability to verify that planned HRMAs were completed or were underway.[28] The military departments did, however, include their plans for HRMAs to be completed in fiscal year 2025 in the departments’ budget submissions for that year.

OSD has broad oversight responsibilities for DOD’s housing programs as defined in statutory requirements.[29] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should obtain data from reliable sources in a timely manner, use quality information to make informed decisions, and implement control activities through policies described in appropriate detail.[30]

However, OSD has not clearly defined its specific oversight role for the HRMA process in guidance. An OSD official told us that they have not exercised sufficient oversight of the services’ HRMA processes because the DOD housing manual assigns responsibility for conducting HRMAs to the military services. This official also told us the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Housing is working toward increasing oversight of HRMAs, such as by more regularly reviewing HRMA information requested from the services, but that this oversight has not been consistent.

Improved OSD oversight of the services’ HRMA process—such as ensuring that HRMAs are conducted in a consistent and timely manner and that DOD submits to Congress the military services’ planned HRMAs for each fiscal year—would better position the department to fulfill relevant statutory requirements. By clearly defining OSD’s oversight role for the HRMA process in guidance, DOD will be better able to ensure that the military services conduct HRMAs in a timely manner and at the required frequency. Further, with improved oversight, DOD would be able to provide more timely information about planned HRMAs to Congress, which would better position DOD and Congress to make fully informed decisions about housing.

DOD Assessments Are Not Used to Identify a Comprehensive List of Military Housing Areas with Critical Availability or Affordability Challenges

DOD’s policy is to rely primarily on the private sector to house service members, and DOD policy states that remote and isolated areas may pose particular challenges to providing safe and affordable housing.[31] However, the department does not have a comprehensive list of military housing areas in which limited housing supply or affordability challenges most severely affect service members and their families.[32] For the purposes of this report, we will refer to these areas as critical housing areas.[33]

DOD Information on Areas with Housing Shortages Varies

OSD and the military services provided us with some information about areas they stated had limited housing availability from various sources, but this information varies by source. For example, the Defense Travel Management Office maintains a list of locations with approved temporary lodging expense extensions. Officials told us locations on this list have been approved for temporary lodging expense extensions due to issues with housing availability and therefore generally represent a list of areas with housing shortages.[34]

However, certain locations with persistent housing availability challenges may not be identified as areas with housing shortages because they do not meet the specific criteria required for temporary lodging expense extensions to be approved.[35] For example, Key West, Florida—a location where officials and service members we met with told us that housing affordability and a limited housing supply are critical problems—is not included on the list of locations with approved temporary lodging expense extensions because it does not meet these criteria.[36]

Further, the Army provided us a list of locations in which service members and military housing offices had directly reported a lack of adequate, affordable off-base private-sector housing. However, Army officials told us this list was compiled specifically as part of an effort in 2022 to review the models used to calculate BAH rates, rather than an effort to identify critical housing areas in the Army. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps officials we met with identified some locations they stated had housing shortages but told us their services have not tracked critical housing areas through a structured analysis.

Limitations Exist with Current Analyses of Housing Areas

As described previously, all services conduct HRMAs to determine the extent to which housing in local communities can accommodate service member populations and to establish requirements for DOD housing. While timely and high-quality HRMAs could provide DOD and the services with important information about military housing areas, we identified limitations of relying solely on HRMAs to identify critical housing areas, particularly in areas with unique characteristics. Further, DOD has not performed a structured analysis to develop a comprehensive, department-wide list of critical housing areas. As a result, DOD has limited department-wide information regarding which military housing areas have the most significant challenges with housing availability and affordability.

Challenges with vacancy rates in areas with high vacation rentals. Despite reportedly high vacancy rates, private-sector housing may be particularly difficult to obtain in areas that have a high density of vacation rental properties. However, HRMAs may identify housing surpluses at installations in these vacation rental areas. As a result, DOD may not have a full picture of the availability of housing. We previously reported that Coast Guard service members identified housing related challenges they experience in high vacation rental areas.[37] For example, they identified that property owners do not offer year-round leases because property owners can command higher monthly rents during peak seasons or use the properties themselves during part of the year. DOD service members we interviewed during this review identified similar challenges.

The American Community Survey’s vacancy rates used as part of HRMAs are to exclude vacation and short-term rentals in the estimated number of vacant units. We selected Naval Air Station Key West as one of our site visit locations because the vacancy rate for the county encompassing that military housing area was about 19 percent, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey. This should reflect a housing market with ample available rentals as compared to the national average of about 6 percent. However, service members stationed at this location described significant challenges finding available and affordable housing, despite the most recent HRMA showing a surplus of housing. In addition, installation officials stated that housing availability and affordability are critical challenges in Key West because of the large share of vacation rentals in the market, which would be cost-prohibitive to rent long-term for many service members.

Challenges with availability of on-base housing. In addition, HRMAs may identify housing surpluses even if a portion of the on-base housing inventory is not available for service members. For example, the most recent HRMA for Naval Air Station Key West showed a surplus of over 200 housing units on base. However, officials told us some of these units have limited availability. Specifically, installation officials told us 222 of their 733 on-base homes are designated specifically for DOD civilians rather than service members. This can exacerbate challenges with housing availability for service members.[38] In addition, on-base housing units are sometimes temporarily unavailable due to systemic maintenance challenges that require long time frames to address, such as problems with heating, ventilation, and air conditioning ducts, according to officials.

Limited coordination in completing HRMAs among services sharing military housing areas. Also, each service may complete its own HRMA rather than coordinating to complete a single HRMA for an entire military housing area with multiple services’ installations. As a result, DOD may not have a clear picture of overall housing requirements and availability for the military housing area on the island of Oahu, Hawaii. For example, each service separately completed the most recent HRMAs for installations on Oahu even though they share the same military housing area. The most recent HRMAs we received for Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam (2021) and Marine Corps Base Hawaii (2023) identified projected housing surpluses, while the most recent HRMA for U.S. Army Garrison Hawaii (2022) identified a projected housing deficit.

Differences in housing requirements and housing demand. According to DOD’s HRMA contractor, DOD has limited information on the differences between the housing requirements identified through the HRMA process and the housing demand revealed by service members’ preferences and behavior. Specifically, the contractor stated that the services have varied in the extent to which they have conducted personnel housing surveys to gather information on service members’ actual housing decisions and preferences to support HRMAs. For example, the Army and Marine Corps last conducted such surveys in 2011 and the Air Force last did so in 2015, according to this contractor. However, according to officials, the Navy is conducting military personnel housing surveys in conjunction with the HRMAs it is conducting for fiscal year 2024 as an effort to further validate housing requirements at its installations. Navy officials told us this survey supplements an HRMA by providing information and data that otherwise would not be available, such as homeownership rates, actual rent and utilities costs paid by service members, and information pertaining to service members’ experiences with housing in the area.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should obtain data from reliable sources in a timely manner and use quality information to make informed decisions.[39]

However, DOD has not performed a structured analysis to develop a comprehensive, department-wide list of critical housing areas. As a result, DOD has limited department-wide information regarding which military housing areas have the most significant challenges with housing availability and affordability, such as those with high rates of vacation rentals. As DOD’s needs and housing markets may change over time, regular updates of such a list would provide the department with timely information. An OSD official told us developing and updating such a list would benefit DOD by providing this information. By performing a structured analysis to develop a list of critical housing areas—incorporating information from multiple sources—and regularly updating the list, DOD and the military services would be better positioned to make more informed housing decisions and to better focus efforts to address housing availability and affordability challenges for service members and their families living in identified critical housing areas.

DOD Does Not Fully Assess Negative Effects of Limited Supply or Unaffordable Housing on Service Members

Service members experience negative financial and quality-of-life effects in areas lacking available, affordable housing, but DOD does not routinely assess these effects. In addition, DOD and the services generally have not used service member feedback on financial and quality-of-life effects.

Service Members Report Experiencing Financial and Quality-of-Life Effects in Areas with Limited Supply or Unaffordable Housing

DOD has stated that many service members and their families experience challenges related to increasingly competitive housing markets, such as extended wait times for housing, reduced housing inventories, and sudden, sharp increases in rental or purchase costs.[40] DOD has taken some steps to assist service members with the challenges they may face in finding affordable housing, such as increasing allowances in areas with significant increases in housing costs.

A 2021 DOD memorandum described the broad financial and quality-of-life effects experienced by service members and their families, as a result of increasing costs of housing and competitive housing markets across the United States. Similarly, an official from OSD’s housing office stated that roughly one-quarter of about 200 installations with military housing offices have expressed concerns about challenges with housing availability and affordability, as well as the resulting effects on service members.

Across all site visit locations, we heard from installation officials and service members about various negative effects experienced by service members due to limited housing availability and affordability, including financial and quality-of-life effects. For example, in all 15 discussion groups we conducted with service members living in privatized housing or in private-sector housing, at least one or more participants indicated they felt housing in the area around their installation was generally unaffordable.

However, we observed differences by location. For example, all discussion group participants in Key West and Oahu stated that housing was unaffordable and many also stated that housing availability was limited. Discussion group participants at Mountain Home Air Force Base all agreed that housing was limited near base, and as a result, many service members seek housing about 50 miles away in Boise, Idaho. Conversely, several discussion group participants in Fort Bliss and Camp Lejeune stated that they were able to generally find and afford housing in the area.

|

Selected Discussion Group Perspectives Regarding Effects on Finances To get better quality homes, we have to pay up to $1,000 per month over BAH. We are expected to be on high alert for 8-hour shifts on base, then have to go to a second job for multiple hours, which causes anxiety and stress. I bought a house years ago, but if I tried to buy it today—or even just to rent it—I would not be able to afford it. Source: GAO discussion groups. | GAO‑25‑106208 |

Financial impacts. While individual experiences varied by location and rank, across all 15 discussion groups, many participants described similar financial challenges due to limited housing availability and high housing costs. For example, at all seven locations we contacted, we heard that some service members paid significant amounts—in some cases hundreds to a thousand dollars—more than their BAH each month to afford housing because of limited availability of housing at costs close to or under their BAH rates. However, some service members in locations with more abundant housing told us they were able to find housing at or below their BAH rate.

Participants in discussion groups at five installations told us they had to use savings, take on significant credit card debt, or obtain second jobs to afford housing and other related expenses. For example, service members in Key West—where long-term rentals are scarce and typically require significant up-front move-in costs—described having to withdraw retirement savings, incur significant credit card debt, or secure additional employment to afford the high costs of rent, utilities, and other items, such as gas and groceries. Participants in 11 of the 15 discussion groups noted that they or others they knew had second jobs to supplement their income given high costs of housing and living expenses. Some installation commanders we interviewed expressed concern that service members’ seeking additional employment could negatively affect their quality of life and work performance in the military.

|

Selected Discussion Group Perspectives Regarding Effects on Quality of Life It doesn’t make sense that we have to work rigorous jobs and still worry about surviving—it leads to service members experiencing financial and mental struggles. The wait time for on-base housing was a year, so I had to settle for a poor-quality home out in town—with major termite issues—just to have somewhere to live. To live in an affordable area, I often have to commute 2 hours each way in traffic. Source: GAO discussion groups. | GAO‑25‑106208 |

Quality-of-life concerns. Across discussion groups we held, participants described negative effects on their quality of life due to limited housing supply and affordability challenges. Some participants described positive effects from having quality housing on or near base. However, other participants reported negative effects such as living in homes with poor conditions or below suitability standards, living with roommates, leaving families behind in other states, or living farther from their installation and experiencing long commute times.

Some discussion group participants told us they had to choose to live in homes below suitability standards or with poor conditions due to a lack of available and affordable housing in their area. For example, at two installations, discussion group participants told us they lived, or knew others who lived, in recreational vehicles due to availability and affordability challenges. Additionally, some discussion group participants told us they had to live in homes without air conditioning in hot, humid climates or in neighborhoods where safety is a concern because they had few private-sector options available when searching for housing.

At two installations, we heard from some discussion group participants that they decided to leave their families behind in other states because they could not find affordable housing of the size needed to comfortably house their families, and it would be financially easier to rent a single room in a shared home or a studio apartment on their own. These service members said living far away from their families negatively affected their quality of life. Service members also described having to live with multiple roommates to afford housing.

Effects on performance and mission. Service members and installation officials also reported that limited housing supply or unaffordable housing can result in negative effects on performance and mission, especially for lower ranked, junior personnel. In some cases, service members may be unable to get to work if they have to commute long distances in dangerous weather conditions. For example, an Air Force official stated that the interstate that many service members use to commute between Boise and Mountain Home Air Force Base is shut down several times a year due to traffic accidents and weather issues.

Further, installation officials told us DOD civilians may also face challenges with housing availability and affordability. Installation commanders at all three installations we visited in Hawaii, as well as at Mountain Home Air Force Base, told us challenges with housing availability and affordability negatively affect their installations’ ability to recruit and retain a qualified civilian workforce necessary to support the installation. At installations in Hawaii—where housing can be scarce and expensive—officials said civilians often face difficulties with housing affordability because they do not receive a housing allowance, resulting in higher turnover and fewer qualified civilian staff. Similarly, officials at Mountain Home Air Force Base told us that while service members’ housing allowances have increased over 100 percent since 2017, civilian locality pay for that location has increased only 2 percent, despite the area’s increased cost of living. As a result, according to these officials, there is little incentive for civilians to move to or stay in the area to fill civilian positions that provide important support of service members living and working on base and are also key in meeting DOD’s mission.

Issues related to privatized housing. Service members may perceive privatized housing to be a better value than private-sector housing in areas with limited availability or particularly high housing costs because the cost of privatized housing is typically equal to service members’ BAH rates.[41] For example, service members living in privatized housing in 10 discussion groups told us they lived there because they would not be able to find similar quality private-sector housing in the local community at their BAH rates.

However, some service members living in privatized housing described issues with maintenance quality and timeliness.[42] In 10 discussion groups we conducted with residents of privatized housing, participants told us having to submit multiple maintenance requests for persistent problems or low-quality maintenance work negatively affected their quality of life.[43] In some cases, discussion group participants described potentially serious problems, such as moisture damage and the presence of possible mold in their homes. For example, at Naval Air Station Key West, installation officials told us persistent challenges with moisture contributed to a leak in the ceiling of one home, and the immediate maintenance response was to brace the damaged ceiling with fence pickets (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Ceiling with Hole Braced with Fence Pickets in Privatized Home on Naval Air Station Key West

Service members and installation officials at all installations we visited told us availability of privatized housing was also limited, exacerbating quality-of-life and financial effects on service members. For example, we heard from discussion group participants that they sometimes had to remain on privatized housing waitlists for long periods given limited availability, and in some cases had to live for extended periods in hotels or short-term rental housing.[44] However, in other cases, service members we spoke with told us they quickly secured privatized housing.

At some installations, discussion group participants told us the quality of homes varied by community, contributing to longer wait times for communities perceived to be higher quality. During site visits to three installations in Hawaii, we observed privatized homes in varied conditions (see fig. 2). Specifically, officials told us that some privatized housing communities perceived to be higher quality had long waitlists (see fig. 2, example 1), while in others, privatized housing companies offered concessions on rent—offering them at costs below BAH rates—for homes with quality challenges, such as older homes, or in less desirable communities (see fig. 2, example 2). Discussion group participants described the financial challenges they would face if they tried to pursue private-sector housing in the local area while continuing to wait for homes in desirable on-base communities to become available.

In some cases, the lack of available privatized family housing could be the result of broader challenges. For example, at Naval Air Station Key West, officials told us many housing units were down for maintenance due to systemic issues or were designated for DOD civilians, and thus unavailable for service members, leading to longer wait times for service members to obtain privatized homes. At Camp Lejeune, officials told us it took years for some housing on the installation to be fully repaired after hurricane damage, resulting in fewer available homes (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Significant Roof Repair to On-Base Privatized Homes at Camp Lejeune after Hurricane Damage

DOD Collects Some Feedback but Does Not Fully Assess the Effects of Limited Supply or Unaffordable Housing on Service Members

DOD employs some methods at the service and installation levels to obtain service member feedback on housing, but these methods focus on residents of privatized military housing and vary by installation. DOD does not routinely assess the effects that limited supply or unaffordable housing has on all affected service members.

Tenant satisfaction survey. The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2020 required each military installation to administer the same tenant satisfaction survey for service members living in all privatized military housing.[45] As such, all military services conduct this survey annually for residents of privatized or government-owned or controlled family housing. Service and installation officials told us the survey provides useful feedback on service members’ experiences with DOD housing, which installations use to identify problems and potential solutions for DOD housing. However, the tenant satisfaction survey is not administered to service members who live in private-sector housing—the majority of service members—which limits the services’ ability to understand the financial and quality-of-life effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on all affected service members.[46] Moreover, it does not include questions related to affordability or any negative financial or other quality of life effects associated with a limited supply of housing.[47]

Installation-specific feedback methods. Installation officials at all site visit locations described installation-specific methods of gathering feedback on the financial and quality-of-life effects of housing on service members. For example, installation commanders told us they conduct regular town hall meetings during which service members can raise issues with DOD housing. Installation commanders also described other methods for feedback on housing, such as emails, maintenance surveys, and interactive customer evaluation comments.[48] Army officials told us that many installation commanders conduct regular “walking” town halls—during which installation leaders visit and meet with residents of on-base housing communities—and that the format has been successful in identifying common housing challenges on installations and bringing greater attention to them given installation leadership’s presence in the on-base housing communities. However, these installation-specific methods focus on residents of privatized housing rather than all service members, and officials across the services stated that feedback from these installation-specific methods is generally not used to identify and develop strategies to address the effects of limited housing supply service-wide.

Status of Forces Survey. DOD conducts an annual department-wide Status of Forces survey to assess a range of personnel issues that affect service members and their families. The survey previously included questions on service members’ experiences and satisfaction with housing, but they were removed from the survey after 2019 because housing was not a priority and to reduce survey length, according to OSD officials. The removal of these questions from the Status of Forces survey limited DOD’s ability to understand the extent to which issues with housing affect service members and to identify in which areas these effects are most critical.

In September 2023, we recommended that DOD collect department-wide information on housing satisfaction, such as through the Status of Forces survey.[49] DOD partially concurred with our recommendation, stating that the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Housing had established a working group with the military departments to update and streamline DOD housing satisfaction survey questions and process. Subsequently, the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 included a provision requiring the department to include such questions on the Status of Forces survey.[50] As of September 2024, DOD officials stated that the Status of Forces survey has been revised to include housing-related questions and they intend to implement the next Status of Forces survey in December 2024.

The DOD housing manual states that the services should evaluate housing-related questions on service-wide or installation-specific surveys to assess the housing choices made by service members and how satisfied they are. It also states that survey results should be used as an additional tool to assess the reasonableness of projected housing requirements. Further, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should obtain data from reliable sources in a timely manner and use quality information to make informed decisions.[51]

The services each use some methods to gather feedback on housing, but none survey the full population of service members. Until the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 required that questions on housing satisfaction and affordability be added to the Status of Forces survey, there was no specific requirement to collect this information on a department-wide scale for all service members, including those living in private-sector housing. In the absence of such a requirement, OSD and the services have had limited information to use to assess or respond to the effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on all service members. An OSD official told us obtaining and using more department-wide information on such effects could enable DOD to better understand challenges in critical housing areas. Going forward, by obtaining and using feedback from all service members through the Status of Forces survey and other existing methods, DOD will be more aware of the extent of the financial and quality-of-life effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing on its service members. Using department-wide feedback will also better position DOD to identify critical housing areas.

DOD Has Not Fully Responded to the Effects of Limited Supply or Unaffordable Housing on Service Members

The services have a responsibility to provide housing referral services to help service members locate suitable and affordable housing when relocating. However, DOD is generally not using the solutions identified in its guidance to fully respond to the effects of limited supply. Additionally, although DOD uses various compensation mechanisms to assist service members with the cost of living, these mechanisms may not adequately address the challenges of critical housing areas.

Housing Offices Generally Provide Housing Referral Services to Service Members

DOD guidance requires the services to provide housing referral services when service members are relocating, and officials from the military housing offices at all seven installations we visited reported that their offices provide these services. Specifically, the DOD housing manual states that installation commanders are to ensure service members receive housing referral services to help them locate suitable, affordable, and nondiscriminatory housing in privatized housing or the local community.[52] In addition, according to OSD, military housing offices are required to track personnel assigned to an installation and provide housing referral services to assist these service members, regardless of location. According to OSD, this assistance is to include referrals to area landlords; assistance with rental negotiations and review of leases; rental partnership programs with select local landlords who will provide discounts to service members; inspections of units for suitability based on environmental, health, and safety considerations prior to leasing; and assistance for service members who have family members who require accessible housing.[53]

Service officials told us installation military housing offices provide this assistance, consistent with requirements. However, during our site visits, we found that the extent to which military housing offices provided these services varied. For example, service members from multiple services we met with in Hawaii told us the military housing offices at their installations provided few resources to assist them with finding suitable off-base housing. Some of these service members said they were unaware of the services that military housing offices are required to provide. In contrast, other service members described having received helpful support from their military housing offices, such as referrals for rental partnership programs with select local landlords or other off-base housing referrals. For example, Marine Corps Base Hawaii’s military housing office maintains a binder of off-base housing rentals (see fig. 4), which contained numerous available rental units when we reviewed the binder in February 2024.

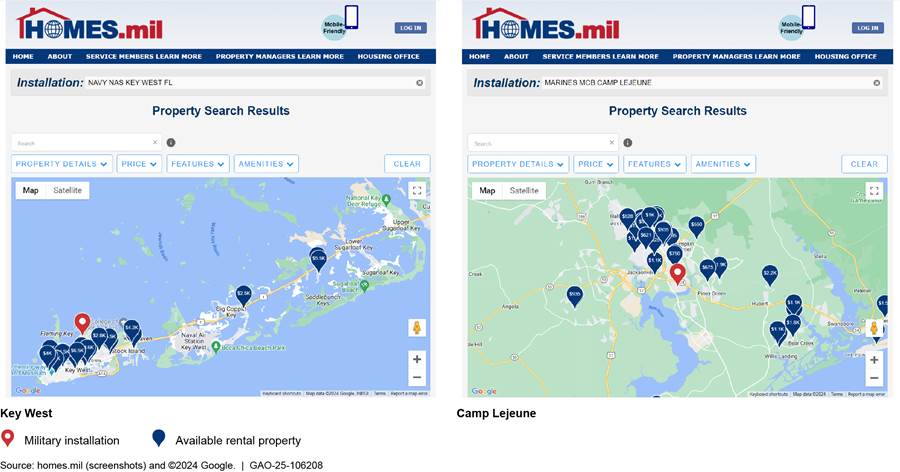

Service officials stated that service members can also access the DOD website HOMES.mil to find a list of local rental and sale properties at each location, however the availability of affordable housing in close proximity to installations varies. Figure 5 shows an example of a comparison between two locations with varying housing availability. In addition, while service members are looking for housing or waiting on a waitlist, they may stay in temporary lodging and be reimbursed for their stay.[54] This reimbursement may be authorized for up to 60 days, depending on the location.

Note: The above HOMES.mil screenshots showing available rental properties near Naval Air Station Key West, Florida, and Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, were accessed on August 26, 2024.

DOD’s Use of Identified Solutions to Respond to Housing Supply Challenges is Limited

DOD is generally not using the solutions identified in DOD guidance to respond to limited housing supply. The DOD housing manual states that when an HRMA determines that the local community around an installation cannot adequately meet the needs of the military community, the military services may pursue (1) privatization, (2) military construction, or (3) leasing to address limited housing supply. However, DOD faces challenges with these options and thus efforts to pursue them have been limited.

· Privatization. Since 1996, DOD has privatized 99 percent of military family housing in the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. One recent example of a new privatization project is the Small Installations Privatization Initiative, an Army project in response to limited housing supply.[55] Additionally, officials from multiple services told us there have been initial discussions about expanding inventory at existing privatized housing projects, and proposals have moved forward at several installations due to housing shortages. For example, according to officials, the Navy has advanced proposals to add nearly 200 privatized military housing units at Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada, and Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California, and nearly 100 units at Naval Station Everett, Washington, due to those installations’ reports of housing deficits.

However, the services and installations may face challenges attempting to build additional privatized housing, even if they have identified a need for additional housing. For example, officials at Naval Air Station Key West told us there is a desire to build additional privatized family housing on an 18-acre parcel of vacant land on the installation, but the ongoing approval process for doing so has been lengthy (see fig. 6). These officials noted this land previously contained government-owned military family housing, but it was demolished due to attrition.

· Military construction. DOD has existing authorities to pursue military construction for all housing. However, DOD generally no longer pursues military construction projects to build military family housing at domestic installations—even if they have identified a need for additional housing—because of the adoption of privatization across domestic installations. DOD does pursue military construction projects for barracks at both domestic and overseas installations and projects for family housing at overseas installations. However, we previously reported on DOD’s challenges in identifying funding needs for constructing new barracks for unaccompanied service members.[56]

· Leasing. DOD has statutory authority to lease family housing units, if necessary, but it does so only in limited circumstances.[57] The DOD housing manual states that leasing should be temporary, used primarily to assist in providing housing for lower-ranking personnel, and used only until DOD housing or private-sector housing becomes available.[58] Leasing is generally uncommon as a result, according to DOD officials. For example, Army officials told us the Army currently leases homes in a small number of more remote locations, such as recruiting stations, where the Army does not have existing housing inventory or long-term housing requirements that would justify privatized housing or military construction projects.[59]

DOD officials have stated that they cannot easily pursue the three identified solutions for limited housing supply outlined in DOD guidance without going through lengthy processes that can result in the long-term financial commitment of federal resources. For example, the process for approval for new privatization projects takes years, and any new projects would be subject to Office of Management and Budget scoring requirements, requiring the services to list the full amount of the loan as an obligated expenditure in its budget.[60] Further, according to an OSD official, expanding privatized housing inventory beyond the number of homes required in a privatized housing project’s legal agreement typically takes more than 2 years.[61] This official also stated that such additional housing development typically requires either a government cash equity investment to pay for the additional homes, or the legal transfer of government-owned housing units to a privatized housing partner—both of which require congressional appropriation and authorization. Officials told us negotiating changes to the legal agreements governing privatized housing projects to add more housing can be a lengthy process, and that privatized housing companies may need to secure additional funding—such as through issuing debt—to obtain enough resources to do so. Expansions are also subject to Office of Management and Budget scoring requirements.

Officials told us longer-term solutions for limited housing supply, such as new or expanded privatization projects, may not be appropriate for short-term issues, such as housing market fluctuations or uncertain force structure decisions. For example, an OSD official stated that the department’s process for identifying housing requirements at installations is intended to help DOD respond to long-term housing needs and not to address short-term housing requirements, such as the market changes resulting from events like the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, according to officials with DOD’s contractor, if there is any risk that planned increases of military personnel at an installation may not take place, privatized housing partners may not invest in developing more housing on or near an installation without a financial guarantee from the government.

OSD, service, and installation officials told us that major challenges with housing availability and affordability have increased in recent years and are particularly challenging and persistent in some areas, and that the department should work to identify feasible solutions. According to an OSD official, for example, installations across the department have reported significant challenges with availability and affordability of housing—including installations for which DOD had not previously considered housing to be a challenge. In addition, this official told us that in some areas housing availability and affordability have been—and are likely to remain—persistent, critical challenges.

DOD’s Current Compensation System Does Not Fully Account for Critical Housing Areas

DOD uses various compensation mechanisms to assist service members with the costs of living, but the mechanisms do not fully account for critical housing areas and may not adequately address the negative effects experienced by service members. We identified potential limitations with BAH, the cost-of-living allowance (COLA), and assignment and special duty pays, which may make it more difficult to use these compensation mechanisms to equitably compensate service members for challenges they face in critical housing areas.

Challenges with BAH calculation and equity. Officials across all services told us certain aspects of the BAH calculation—specifically the anchor points—may not be suitable, especially for areas with limited housing supply or high costs.[62] DOD officials overseeing the BAH program told us the anchor point system does not work well in areas with limited housing supply, and that anchor points should be reviewed or potentially replaced. For example, they told us in military housing areas with limited housing supply, service members may receive a BAH rate based on a housing type that is unavailable for them to rent. As a result, they may have to choose between renting a smaller sized unit or renting a larger sized unit and pay some amount above BAH for their housing.

Challenges with anchor points also may contribute to inequity—differing experiences of financial and quality-of-life burden or benefit—among service members of the same rank based on their family status or location. DOD is in the process of completing its Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation, which an official said is estimated to be complete in January 2025.[63] According to officials, the process is reviewing the BAH program’s anchor points and other potential areas for improvement, and the results of this review may be used to make future changes to the BAH program.

BAH rates are based on housing costs for civilians with comparable incomes to service members in a military housing area. While officials acknowledged that the size, quality, and cost of private-sector housing vary across military housing areas, service members often have little to no control in where they are sent to serve—whether a major metropolitan area, a rural area, or a popular vacation destination. Across installations we visited, service members participating in discussion groups reported a perceived inequity resulting from their assigned duty stations. Specifically, they reported experiencing a high standard of living in some locations, compared to experiencing financial difficulty in locations with high costs of living and housing. For example, service members at some installations told us they had previously been able to afford high-quality private-sector housing for less than their BAH at previous duty stations, while at their current duty stations they had to pay significant amounts above their BAH for much lower-quality private-sector housing—despite receiving higher BAH in those more expensive locations.

Limited use of cost-of-living allowance in continental United States. While not specifically related to housing, service members living in areas with high costs of living may receive a COLA. At six site visit locations, service members who were receiving or had received a COLA at other duty stations told us it helped them with overall expenses, reducing financial burden due to high costs of living, including high costs of housing. Further, in Hawaii, service members at all three installations we visited told us they experienced financial difficulties as a result of recent decreases in Hawaii’s COLA.[64] Additionally, service members in Key West—a location in the continental United States where service members do not receive a COLA—told us they felt they should receive a COLA given the extreme financial burden they experience.[65] Navy officials similarly recognized Key West as a critically challenging area given high costs and limited housing availability.

In 2024, service members living in 15 of the approximately 300 military housing areas in the continental United States were eligible to receive a COLA.[66] DOD information regarding the continental United States COLA states that the availability of military commissaries or exchanges in proximity to a service member’s place of duty implies that expenditures for the member will be lower than for a comparable civilian, and that the presence or absence of facilities has an impact on the calculation of the continental United States COLA index. However, we previously reported that the savings for commissary customers within the continental United States is consistently lower than the target, and that the methodology used by the commissaries to report savings for locations outside the continental United States is unreliable.[67] Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness officials told us the ongoing Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation will also examine the processes and methodologies for calculating COLA.

Assignment and special duty pays generally not used for housing. Military department secretaries generally possess authority to offer special duty pay to service members under eligibility conditions they can establish. However, while service members may receive these forms of compensation in especially difficult locations or for unusual assignment circumstances, the services generally do not use them to offset the financial burden experienced because of limited housing supply.[68] For example, Army officials told us the Army has increased special duty pay in some locations due to high costs, but generally has not explored the use of various compensation authorities to respond to the financial effects of limited housing supply on service members.

DOD has previously temporarily increased BAH rates in certain areas to ease the financial burden of rising housing costs for service members. However, DOD officials told us service members and installation commanders may perceive that BAH should compensate for issues outside of what BAH can address, such as a lack of housing supply. According to these officials, BAH is not specifically designed to compensate service members for the challenges they face in areas with limited housing supply. Rather, BAH is meant to provide service members additional compensation commensurate with median housing costs for housing types associated with their pay grade and dependent status in each area.

In addition, DOD and local government officials described a perception that BAH rate increases inflate housing prices and therefore disadvantage local civilians, who do not receive housing allowances. For example, we surveyed local government officials and organizations from selected areas near military installations.[69] When asked about how BAH rates provided to service members affect housing in their communities, some respondents stated that BAH can benefit local housing markets, such as by securing income for local landlords and providing access to better quality housing for service members. However, 18 of 30 survey respondents who answered the question indicated they believed that BAH rate changes affect housing affordability in their communities. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness officials stated they did not share the perception that BAH rate increases inflate housing prices because the military represents only a small portion of the population in many housing areas, and overall military compensation is generally higher than the average U.S. civilian income.

Given these challenges with raising BAH rates, some DOD officials stated that other compensation mechanisms, such as assignment and special duty pays, could be more suitable to alleviate service members’ financial challenges resulting from limited housing supply, especially in critical areas.

The DOD housing manual states it is DOD policy to ensure personnel and families have access to affordable, quality housing facilities consistent with pay grade and dependent status and generally reflect contemporary living standards. However, this guidance is not clear about how the department should plan to respond to and address critical housing areas. In addition, the Military Compensation Background Papers state that military compensation should be based on certain underlying principles, including equity and fairness.[70]

The Coast Guard’s guidance on critical housing areas addresses how service members’ compensation may be affected by their assignment to critical housing areas.[71] In contrast, DOD’s guidance does not address how alternative compensation methods could be used to address the financial and quality-of-life challenges service members face due to critical housing areas.

Because solutions identified in DOD’s housing policy for limited housing supply may not be feasible in certain areas, and therefore not pursued by the services, DOD is less able to respond to the effects of limited housing supply in these same areas. However, an OSD official told us that DOD could do more to identify feasible strategies for addressing limited housing supply. By developing a plan to identify and implement feasible solutions to address limited supply in critical housing areas, once these areas are identified, DOD and the military services will be better able to ensure that service members and their families have access to affordable, quality housing. Further, by determining whether and how alternative compensation could potentially be provided to offset the effects of limited supply or unaffordable housing in critical housing areas, the department will be better positioned to ensure that total compensation meets the principles of equity and fairness in areas with persistent and long-term housing challenges.

DOD Coordination with Local Communities to Address Housing Issues Varies

DOD’s coordination with local communities varies across installations. In response to our survey, some local government officials described challenges they face in coordinating with military installation officials. In addition, through statistical analysis, we found that communities with a higher military population were associated with higher median rents. However, DOD guidance does not define how installations, including military housing offices, are to coordinate with communities on housing issues.

DOD Encourages Coordination, but the Services Vary in How They Interact with Local Communities

DOD encourages installation coordination with local communities on issues like housing, but the coordination varies across installations. The DOD housing manual states that installation commanders are encouraged to work proactively with community leaders, especially during periods of increased military movements. In addition, it states that the installation commander shall coordinate with community and government officials as part of providing member support services.

As such, although installation commanders are generally responsible for coordinating with local government officials regarding housing issues, this coordination varies across the services. Moreover, military service-specific guidance varies in the level of detail provided on how coordination with local officials is to occur. Military service guidance generally states that the housing offices should maintain relationships with local community organizations. However, Army guidance is more extensive and with clearer direction than the guidance of the other services. For example, the Army’s facilities management guidance requires that installations’ housing offices pursue an active role in their relationships with local community entities associated with real estate and the housing market, and it states that the housing office must be active in local, off-post communities in an aggressive search for additional adequate housing.[72] Further, U.S. Army Installation Management Command conducts annual training for senior level housing officials called “Housing the Force” to discuss installation housing and management for service members, according to officials (see fig. 7). Conversely, the other services’ guidance does not state in detail the responsibilities of the housing offices for engaging with local community organizations beyond maintaining relationships.