HAZARDOUS WASTE

EPA Should Take Additional Actions to Encourage Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities to Manage Climate Risks

Report to Congressional Requesters

November 2024

GAO-25-106253

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106253. For more information, contact J. Alfredo Gomez at (202) 512-3841 or gomezj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106253, a report to congressional requesters

November 2024

HAZARDOUS WASTE

EPA Should Take Additional Actions to Encourage Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities to Manage Climate Risks

Why GAO Did This Study

More than 1,000 facilities across the nation treat, store, and dispose of hazardous waste that could harm human health and the environment if released. Natural hazards such as flooding—which may become more frequent and intense due to climate change—can lead to hazardous waste releases. RCRA governs the management of hazardous waste by facilities. EPA promulgates RCRA regulations to minimize the risk of releases from facilities and has authorized 48 states to implement these regulations in lieu of EPA. EPA regional offices assist and oversee states in implementing RCRA.

GAO was asked to review EPA’s role in addressing climate risks to facilities. This report examines 1) the extent to which facilities are located in areas with selected natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change; 2) the extent to which EPA requires or encourages authorized states and facilities to manage risks to human health and the environment from climate change; and 3) challenges EPA, states, and facilities face in managing climate risks. GAO analyzed federal data on facilities and four natural hazards, reviewed agency documents, and interviewed officials from EPA headquarters and five regional offices, four state agencies, and eight stakeholder groups.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making nine recommendations to EPA, including that it provide training and technical assistance and assess issuing regulations to clarify requirements and provide direction on managing facility climate risks. EPA agreed with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

Federal data on flooding, wildfires, storm surge, and sea level rise indicate that more than 700 hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities, or about 68 percent, are located in areas with one or more of these hazards that could be exacerbated by climate change.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regions, authorized states, and facilities need more clarity on whether managing climate risks to facilities is required or there is existing authority to do so under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA). EPA has taken steps to clarify authorities and requirements for managing climate risks as part of permitting but has not done so for compliance and enforcement efforts, such as inspections. In June 2024, EPA issued guidance on selected RCRA authorities that regions and states could use to develop facility permit requirements to manage climate risks. However, some states and facilities may not implement the guidance unless EPA amends regulations to explicitly clarify authorities and requirements. EPA officials said the agency could provide training and technical assistance to regions and states to help ensure they understand and implement the guidance, but EPA has not done so yet. Without providing this training and technical assistance and seeking further feedback to determine whether it should issue regulations to fully clarify authorities and requirements for managing climate risks, EPA may be unable to ensure effective and consistent management of these risks.

EPA regions, states, and facilities also face challenges in managing climate risks. For example, regions, states, and facilities need guidance on how to assess climate risks and face challenges in knowing what data they should use to do so, according to interviews with officials from EPA, states, and stakeholder groups. By issuing guidance to regions, states, and facilities on how to manage climate risks, along with providing data, tools, and training, EPA could better ensure these risks are managed sufficiently and that regions, states, and facilities have the direction and information necessary to do so.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CRRA |

2014 Community Risk and Resiliency Act |

|

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

HELP |

Hydrologic Evaluation of Landfill Performance |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 |

|

DEC |

New York Department of Environmental Conservation |

|

NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

|

OECA |

Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance |

|

OLEM |

Office of Land and Emergency Management |

|

RCRA |

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 |

|

TSDF |

Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facility |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 14, 2024

The Honorable Tom Carper

Chairman

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Cory A. Booker

United States Senate

More than 1,000 facilities across the nation treat, store, and dispose of various types of hazardous waste that would pose harm to human health and the environment if released. For example, trichloroethylene—a widely used industrial chemical and a known human carcinogen—is managed in treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs). These facilities are engineered to prevent releases of hazardous waste into the environment and contamination of drinking water. However, these facilities could be at risk from natural hazards such as flooding and hurricanes, which the Fifth National Climate Assessment indicates may become more frequent and intense due to climate change.[1] These natural hazards may lead to hazardous waste releases, according to the Association of State and Territorial Solid Waste Management Officials and the Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center.[2]

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA) is the primary federal law governing the management of hazardous waste from generation to disposal to protect public health and the environment.[3] RCRA directs the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to establish regulations to ensure that hazardous waste is managed safely throughout its life cycle. Under RCRA, EPA may authorize states to administer and enforce the RCRA hazardous waste program within their jurisdiction provided the state program is at least as stringent as the federal requirements.[4] EPA regional offices work with authorized states to implement and enforce the RCRA hazardous waste program within their regions. However, EPA regions, authorized states, and TSDFs themselves may face challenges in managing climate risks (e.g., future changes to natural hazard conditions due to climate change, such as more frequent or intense weather events) at these facilities.

You asked us to review EPA’s role in addressing climate risks at TSDFs regulated under RCRA.[5] This report examines the (1) extent to which TSDFs are located in areas with selected natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change; (2) extent to which EPA requires or encourages authorized states and TSDFs to manage risks to human health and the environment from climate change; and (3) challenges that EPA, authorized states, and TSDFs face in managing risks to human health and the environment from climate change, and opportunities for EPA to address these challenges.

To examine the extent to which TSDFs are located in areas with selected natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change, we reviewed documents such as the Fifth National Climate Assessment and interviewed EPA officials to identify natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change and that could affect TSDFs. We identified nationwide federal datasets on four natural hazards that the National Climate Assessment and other sources reported may be exacerbated by climate change in some areas of the country:

· flooding, with data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA);

· wildfires, with data from the U.S. Forest Service;

· storm surge from hurricanes, with data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); and

· sea level rise, with data from NOAA and an interagency report.

For wildfires, flooding, and hurricane storm surge, the federal data are based on existing or historical weather patterns and data (which do not incorporate climate projections). For sea level rise, we used data for coastal regions and sea level rise projections from an interagency report covering sea level rise scenarios. Throughout this report, we refer to these four hazards as selected natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change.

We also analyzed EPA and state data on the locations and other characteristics of TSDFs and used mapping software to identify TSDFs located in areas that may experience the selected natural hazards. For our analysis, we used EPA and state data to identify operating TSDFs with permits that allowed them to actively handle hazardous waste and nonoperating TSDFs with post-closure care permits for units with waste in place. We assessed the reliability of the data sources used and found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our analysis.[6] For more detailed information on our scope and methodology and the steps we took to assess the reliability of the data used in this report, see appendix I. For more detail on data sources used in this report, see appendix II.

To examine the extent to which EPA requires or encourages authorized states and TSDFs to manage risks to human health and the environment from climate change, we analyzed documentary and testimonial evidence from EPA headquarters and five selected EPA regional offices; four selected authorized states; and eight stakeholder groups.[7] We also analyzed statutory and regulatory requirements, executive orders, and EPA policy documents to identify climate-related requirements and guidance. We reviewed guidance from the selected EPA regions that they provided to authorized states on developing annual work plans for their RCRA programs.

We assessed the extent to which the five selected EPA regions provided requirements or regional guidance for authorized states to include goals or commitments in their work plans related to managing climate risks to TSDFs. We reviewed all 25 state RCRA program work plans from the selected EPA regions to assess the extent to which these plans included commitments to incorporate climate-related risks into the state’s RCRA oversight at TSDFs. We also reviewed RCRA permits, contingency plans, and compliance inspection reports for eight TSDFs.[8] We assessed the extent to which the permits and contingency plans account for future projections of natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change. We also assessed the extent to which the inspection reports reflect climate risks present at the facilities.

To identify challenges that EPA, authorized states, and TSDFs face in managing risks to human health and the environment from climate change, and opportunities for EPA to address these challenges, we reviewed EPA documents, our prior work, and relevant documents from other organizations, such as state associations. We also interviewed officials from EPA headquarters and the selected regions, selected authorized states, and stakeholder groups to obtain their views on the challenges EPA, authorized states, and TSDFs face in managing risks from climate change and opportunities for EPA to address these challenges. The views of selected EPA regions, authorized states, and stakeholder groups we interviewed are illustrative and not generalizable to all EPA regions, states, and stakeholder groups.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2022 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Types of Hazardous Waste and TSDFs

Under RCRA, a waste is hazardous when it exhibits the characteristic of ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity, or toxicity, or is listed as a hazardous waste in the RCRA regulations.[9] These characteristics can make hazardous waste dangerous or capable of having a harmful effect on human health or the environment. Under RCRA, hazardous waste must be treated, stored, or disposed at permitted facilities, or TSDFs. See table 1 for examples of hazardous waste subject to RCRA.

|

· Spent solvents (such as degreasing and cleaning solvents) · Petroleum refinery oil/water separation floats and sludges · Hazardous waste landfill leachates |

· Veterinary pharmaceuticals · Automotive paint waste · Toxic metal-bearing dust from steel production |

· Formulations in which the hazardous chemical is the sole active ingredient · Residues, contaminated soil, water, or debris resulting from cleanup of spills of hazardous materials |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documentation. | GAO‑25‑106253

Note: Hazardous waste excluded from Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA) hazardous waste regulations includes certain household waste, waste generated from growing and harvesting agricultural crops, and other types of solid wastes EPA has identified in regulation. See 40 C.F.R. 261.4(b).

|

Example of Hazardous Waste Regulated under RCRA: 1,4-Dioxane Effects on Human Health 1,4-Dioxane is a clear liquid that easily dissolves in water and is considered hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA) when it is discarded as a commercial product. It is used primarily as a solvent in the manufacture of chemicals and as a laboratory reagent. 1,4-Dioxane is a trace contaminant of some chemicals used in cosmetics, detergents, and shampoos. However, manufacturers now reduce 1,4-dioxane from these chemicals to low levels before these chemicals are made into products used in the home. Exposure to 1,4-dioxane occurs from inhalation of contaminated air, ingestion of contaminated food and drinking water, and dermal contact with products such as cosmetics that may contain small amounts of 1,4-dioxane. Exposure to high levels of 1,4-dioxane in the air can result in damage to the nasal cavity, liver, and kidneys. Ingestion or dermal contact with high levels of 1,4-dioxane can result in liver and kidney damage. 1, 4-Dioxane sent to treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs) is generally transported in 55-gallon drums. Once at the TSDF, 1,4-dioxane is commonly incinerated but can also be disposed of in landfills after treatment, recycled, or stored. Source: GAO review of Environmental Protection Agency and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry information. | GAO‑25‑106253 |

TSDFs can be operational—facilities that receive hazardous waste—and nonoperational—facilities serving as permanent sites for disposal of hazardous waste that are in closure and post-closure care and are not receiving waste.[10] All facilities are subject to RCRA’s closure and post-closure requirements, whether they are owned or operated by private entities or federal, state, or local governments.[11]

TSDFs can have different types of waste management units, depending on the hazardous waste handled at the facility. For example, some facilities have land treatment units to degrade, transform, or immobilize hazardous constituents present in hazardous waste so it is no longer toxic to human health and the environment. Other facilities may have tanks to store or treat large volumes of hazardous waste, boilers to burn hazardous waste while recovering usable materials for future use, or incinerators to destroy hazardous waste. Others have landfills that are used to dispose of hazardous waste—which requires the landfill to be monitored while operational and after it closes. In some cases, a single facility may be permitted for more than one unit type.

RCRA Technical Standards and Requirements for Control Measures

RCRA requires EPA to issue regulations establishing technical standards and requirements for TSDFs to ensure that permits include adequate control measures to manage hazardous waste and prevent releases.[12] For example, EPA regulations require TSDF permits to include general facility standards and preparedness and prevention requirements to avoid a release from natural hazards, among other things. RCRA permits must be protective of human health and the environment, technically sound and accurate, and enforceable, and include all RCRA regulatory and state-specific requirements. See table 2 for selected RCRA regulations aimed at preventing or mitigating hazardous waste releases from natural hazards.

|

Facility siting standards [40 C.F.R. 264.18(b)] |

RCRA regulations require treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs) located within a 100-year floodplain to be designed to withstand washout from a 100-year flood event, should there be a flood.a Surface impoundments, waste piles, land treatment units, and landfills must ensure no adverse effects on human health or the environment will result if washout occurs. Several factors must be considered, including the volume and physical characteristics of the waste in the facility and the impact of hazardous constituents on the sediments of affected surface waters or the soils of the 100-year floodplain that could result from washout, among other considerations. |

|

Containment and detection of releases [40 C.F.R. 264.193] |

Secondary containment systems must have sufficient strength and thickness to prevent failure owing to climatic conditions, among other requirements. Secondary containment for tanks must include external liner systems that are designed and operated to prevent run-on or infiltration of precipitation into the secondary containment system unless the collection system has sufficient excess capacity to contain run-on or infiltration. Such additional capacity must be sufficient to contain precipitation from a 25-year, 24-hour rainfall event.b |

|

Facility design and operations [40 C.F.R. 264.31] |

Facilities must be designed, constructed, maintained, and operated to minimize the possibility of a release of hazardous waste that could threaten human health or the environment. |

|

Landfill design and operating requirements [40 C.F.R. 264.301] |

Landfills must have a liner system for all portions of the landfill. The liner material must be constructed with sufficient strength and thickness to prevent failure due to pressure gradients, physical contact with the waste or leachate, and climatic conditions, among other requirements. |

Source: GAO analysis of Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA) regulations. | GAO‑25‑106253

aA 100-year flood is a flood with a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. The 100-year floodplain designations are provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to support the National Flood Insurance Program. EPA defines “washout” as hazardous waste moving from the TSDF because of flooding. 40 C.F.R. 264.18(b)(2)(ii).

bA 25-year, 24-hour rainfall event refers to a storm with a 4 percent probability of occurring in any given year and is a minimum rainfall amount used to design containment systems at TSDFs to ensure stormwater does not release hazardous waste into the environment. Precipitation frequency data are used to establish the design storm (or amount of rainfall in a period of time) and is expressed in terms of recurrence interval (e.g., 25-year) and duration (e.g., 24-hour).

To secure a permit, each facility must have a contingency plan designed to minimize hazards to human health or the environment from fires, explosions, or any unplanned sudden or nonsudden release of hazardous waste.[13] Regulations also require that facilities review and amend contingency plans, as necessary, when the applicable regulations or facility permits are revised, the plan fails in an emergency, or there are certain changes to the facility, the list of emergency coordinators, or the list of emergency equipment.[14] Facilities are required to submit updated contingency plans to their regulatory authority—typically authorized states—for review and approval.

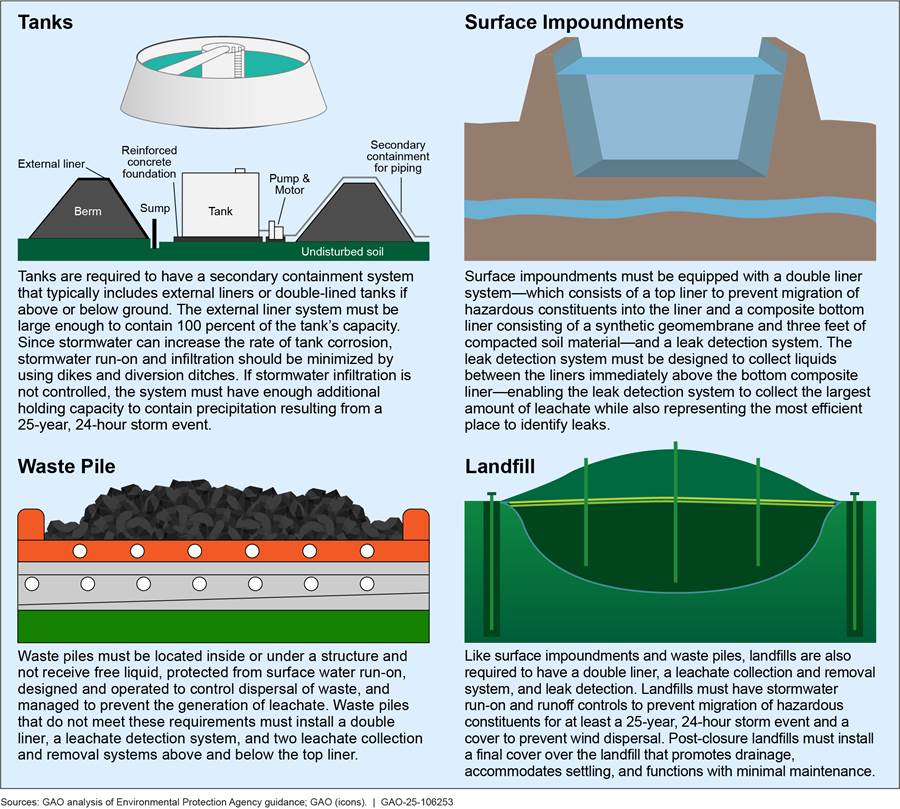

RCRA regulatory standards and control measures require TSDFs to safeguard their waste management units in a manner that will prevent hazardous waste releases that could threaten human health and the environment, including those caused by natural hazards. If waste management units are not properly maintained to withstand the effects of natural hazards or if control measures fail over time, the hazardous waste stored within these units can leak into the environment, contaminating groundwater and drinking water sources. See figure 1 for selected features of TSDF waste management units to prevent or mitigate hazardous waste releases.

EPA and Authorized State Roles and Responsibilities

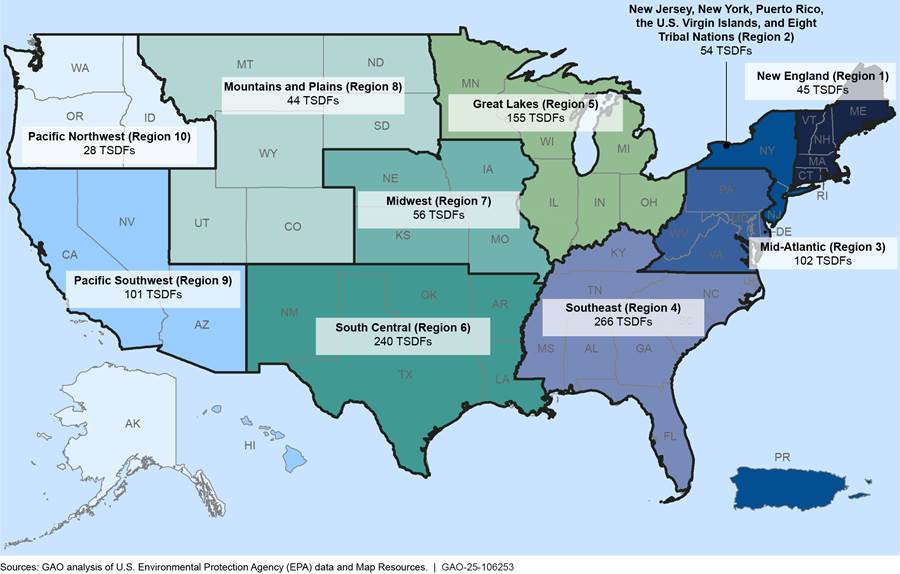

Under RCRA, EPA may authorize states to administer and enforce the RCRA hazardous waste program in their jurisdiction. To receive authorization, RCRA requires a state hazardous waste program to be at least equivalent to and consistent with the federal program. States may adopt the federal regulations verbatim or adopt state laws that are equivalent to or more stringent than the federal regulations. In addition, states enter into a memorandum of agreement with their EPA regional office that identifies each party’s roles, responsibilities, and oversight powers. The memorandum of agreement also defines the coordination between the authorized state and EPA in implementing and enforcing the program. As of April 2024, EPA had authorized 48 states to administer their own RCRA hazardous waste programs.[15] Figure 2 shows the number of TSDFs per EPA region.

Notes: To identify TSDF locations, we used EPA and state data from EPA’s RCRAInfo database, as of July 2023. In this figure, TSDFs refer to operating facilities that are permitted to actively receive and handle hazardous waste and nonoperating facilities with at least one permitted post-closure unit with waste in place. The RCRAInfo database is EPA’s comprehensive information system that provides access to data supporting the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA). The data we used do not include any updates to TSDF information in the RCRAInfo system that were made after July 2023. As a result, we did not include TSDFs in our analysis if they did not have a relevant operating or nonoperating status code as of July 2023.

Under RCRA, authorized states oversee the issuance and maintenance of permits for TSDFs located within their jurisdiction. EPA regions and authorized states have issued RCRA permits for a variety of hazardous waste management units at more than 1,000 TSDFs. In addition, authorized states are required to conduct compliance evaluation inspections at TSDFs. Compliance evaluation inspections are conducted on-site and designed to assess compliance of the whole facility, including process-based inspections that comprehensively evaluate the facility’s waste management practices. These inspections evaluate a facility’s compliance with all applicable RCRA regulations and permit requirements. Authorized states are expected to annually inspect at least 50 percent of nongovernment TSDFs to ensure inspections are performed no less often than once every 2 years, according to EPA’s RCRA Compliance Monitoring Strategy.[16] If EPA or the authorized state determines through an inspection that a TSDF is not in compliance with RCRA permit conditions or program requirements, they have authority to take enforcement action to bring the facility into compliance.

While authorized states administer their own RCRA programs, EPA maintains certain oversight authorities to ensure state compliance with RCRA regulations. All EPA regional offices and two EPA national program offices contribute to EPA’s management and oversight of the RCRA program:

· EPA Office of Land and Emergency Management (OLEM) provides policy, guidance, direction, and oversight, and distributes funding for the implementation of the RCRA hazardous waste program. OLEM issues national regulations, defines solid and hazardous wastes, and imposes standards on entities that generate, transport, treat, store, or dispose of hazardous waste. OLEM also provides guidance to EPA regional offices on overseeing the RCRA program in authorized states.

· EPA Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA) issues enforcement and compliance guidance for all EPA programs, including RCRA, to regional offices and authorized states. For example, OECA issues the RCRA Compliance Monitoring Strategy, which is designed to provide strategic guidance for EPA regions and RCRA-authorized states and create national consistency in how EPA and states perform compliance monitoring. The strategy does so in part by providing a minimum set of expectations and a decision logic and structure for targeting inspections.[17] OECA and EPA regional offices retain authority to enforce RCRA in authorized states, and EPA inspections are a key aspect of EPA’s oversight of state programs and TSDFs, according to the strategy.

· EPA regional offices implement EPA programs, policy, and regulations in their respective regions, including for the RCRA program. Regional offices coordinate this work with authorized states and provide oversight of them to ensure effective implementation of RCRA. In addition, regions provide guidance and meet with authorized state managers to discuss grant funding, annual work planning, and inspection strategy development, among other things. EPA regions may conduct oversight inspections with or after state inspectors to monitor the quality of the states’ TSDF inspections.[18] As a component of oversight inspections, EPA regions may review state inspection reports to ensure that inspections are conducted properly, appropriate inspection procedures are followed, and sufficient evidence is collected. EPA regions enforce compliance in tribal lands and in states not authorized to implement the RCRA hazardous waste program. EPA regions also may review new and modified TSDF permit applications and draft permits, in coordination with authorized states.

According to EPA’s RCRA Compliance Monitoring Strategy and EPA officials, formal oversight and evaluation of authorized states is generally performed in two ways—state work plans and the state review framework.

State work plans. State work plans are annual cooperative agreements between each authorized state and its EPA regional office. OLEM and OECA provide national program guidance and set minimum requirements for the state work plans. EPA regions use the guidance to negotiate and develop state work plan requirements with authorized states as part of their grant applications for federal funds to support their RCRA program activities.[19] These plans detail the activities each state will perform in implementing the RCRA program to meet grant funding requirements and set expectations for what the state will accomplish over the following year. EPA reviews these work plans annually to ensure states meet their performance goals.

State review framework. This national framework, developed by EPA and states, provides a consistent process for evaluating the performance of and compliance with selected EPA programs, including RCRA, in authorized states.[20] Under the framework, each program is reviewed once every 5 years. EPA evaluates the performance of authorized programs for a 1-year period (typically the 1-year period prior to review) using a standard set of metrics in five areas: data, inspections, violations, enforcement, and penalties. For states’ TSDF inspections, the framework evaluates the completeness and accuracy of inspection data, coverage, report quality, and timeliness. The state review framework evaluation verifies whether the states have submitted RCRA minimum data requirements, as shown in table 3.

|

Compliance evaluation performed |

|

Compliance evaluation results (violation/compliance status) |

|

Severity of violation |

|

Notices of violation (informal enforcement) |

|

Formal enforcement actions |

|

Amount of assessed penalties |

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, State Review Framework: Compliance and Enforcement Program Oversight Reviewer’s Guide Round 5 (2024-2028) and EPA Enforcement and Compliance History Online Data Entry Requirements. | GAO‑25‑106253

Note: RCRAInfo—the federal database used to store and track RCRA information and activity—contains information on violations of federal RCRA requirements as well as violations of state hazardous waste management programs, which may be broader in scope or more stringent than the federal RCRA Subtitle C hazardous waste program.

Climate Adaptation Policies, Plans, and Strategies

Executive Order 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, states that it is the policy of the administration to deploy the full capacity of federal agencies to combat the climate crisis by implementing a government-wide approach that increases resilience to the impacts of climate change, among other things.[21] The executive order also directs agencies to develop action plans with steps each agency can take to bolster adaptation and increase resilience to the impacts of climate change. It requires agencies to submit annual progress reports to the National Climate Task Force and the Federal Chief Sustainability Officer.[22]

In October 2021, EPA released its 2021 Climate Adaptation Action Plan.[23] The plan states that EPA will ensure its programs, policies, regulations, and compliance and enforcement efforts consider current and future impacts of climate change and how those impacts will disproportionately affect certain communities. In addition, the plan identifies five priority actions for the agency to implement and directs EPA national program offices and regional offices to develop implementation plans that will incorporate these priority actions over time (see table 4). In October 2022, all EPA national program offices and all 10 regional offices issued Climate Adaptation Implementation Plans to implement these priority actions.[24]

|

Priority Action #1: Integrate climate adaptation into EPA programs, policies, rulemaking processes, and enforcement activities. |

|

Priority Action #2: Consult and partner with states, Tribes, territories, local governments, environmental justice organizations, community groups, businesses, and other federal agencies to strengthen adaptive capacity and increase the resilience of the nation, with a particular focus on advancing environmental justice. |

|

Priority Action #3: Implement measures to protect the agency’s workforce, facilities, critical infrastructure, supply chains, and procurement processes from the risks posed by climate change. |

|

Priority Action #4: Use measurement, data, and evidence to evaluate performance. |

|

Priority Action #5: Identify and address climate adaptation science needs. |

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Climate Adaptation Action Plan. | GAO‑25‑106253

In March 2022, EPA issued its strategic plan for fiscal years 2022 to 2026, which communicates the agency’s priorities to address climate change.[25] The first goal of the strategic plan is to address the climate crisis. This goal includes an objective to accelerate resilience and adaptation to climate change impacts. In June 2024, EPA released its updated Climate Adaptation Plan for 2024-2027, which highlights EPA’s planned actions from 2024 to 2027 to continue to make progress toward implementing its five priority action areas from the 2021 plan and strategic plan goals.[26]

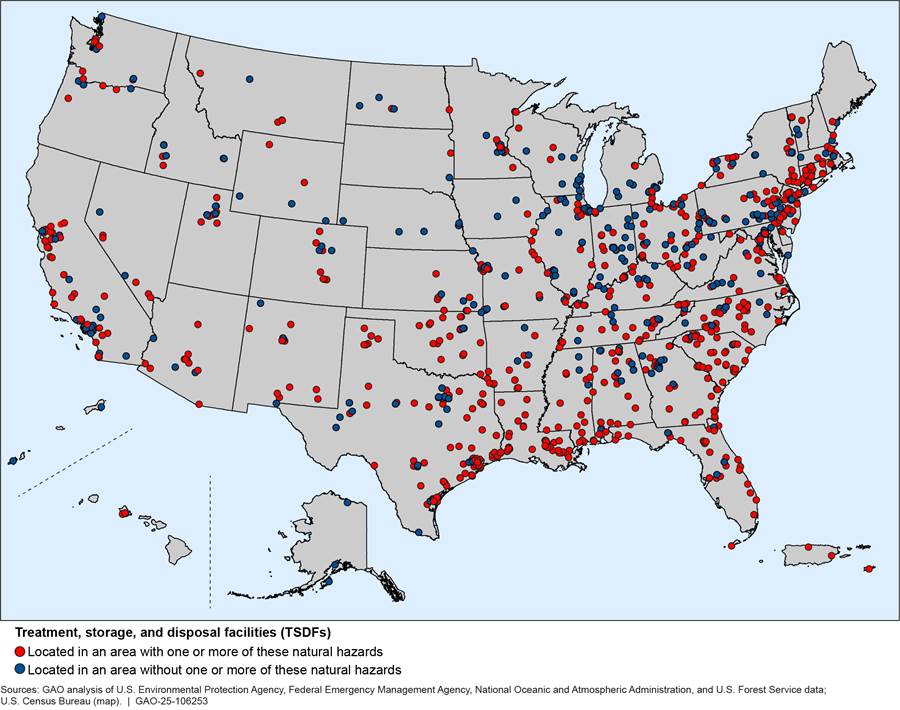

More than 700 TSDFs Are Located in Areas with Selected Natural Hazards That May Be Exacerbated by Climate Change

Available federal data on flooding, wildfire, storm surge, and sea level rise suggest that 743 of 1,091 TSDFs, or about 68 percent, are located in areas with one or more selected natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change.[27] Figure 3 shows the locations of these facilities. Climate change could exacerbate these natural hazards, such as by making them more frequent or intense. Climate change can also pose risks to TSDF waste management controls used to safeguard waste from being released, according to documents we reviewed and interviews with officials from EPA headquarters and regions, three authorized states, and four stakeholder groups.[28] For example, some TSDF landfills may face climate risks from sea level rise or increased flooding and are not designed and operated to account for how future natural hazard conditions may be different than historical data, according to an EPA report.[29]

Notes: We analyzed actively operating TSDFs and nonoperating TSDFs that have waste in place. To determine if a TSDF is located in an area with exposure to flooding, wildfire, storm surge, or sea level rise, we identified overlap between an estimated radius around a facility’s primary coordinates provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and federal data for each of these selected hazards. Overlap indicates that a facility is located in an area that may be affected by one or more of these selected hazards. This analysis includes facilities that are located in areas with at least one or more of the following natural hazards: 0.2 percent or higher annual chance of flooding or other flood hazards; storm surge from Category 4 or 5 hurricanes; moderate, high, or very high wildfire hazard potential; and regional sea level rise values for the 2100 intermediate scenario from an interagency sea level rise technical report. This analysis is based on the most recently available data from EPA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the U.S. Forest Service, as of 2023. We approximated the boundaries of TSDFs using a radius around each facility’s primary geographic coordinates based on acreage data for the facility that EPA provided. Facility boundaries based on these data do not account for where hazardous waste is specifically handled at facilities and we did not analyze site-specific information for these TSDFs, such as steps that specific facilities have taken to manage potential risks from selected natural hazards. See appendix I for more details on our data analysis.

Our analysis, however, may not fully account for the number of TSDFs that may be affected by these hazards for several reasons. First, data are not available for some areas. For example, FEMA has not mapped some areas of the country to determine exposure to flooding, and FEMA maps do not account for pluvial flooding (which occurs when rainfall creates a flood independent of an existing body of water). Additionally, sea level rise data are not available for Alaska, and some storm surge data are not available for areas of California. Second, we approximated the boundaries of TSDFs using a radius around each facility’s primary geographic coordinates based on acreage data for the facility, which may not precisely reflect its area or account for where hazardous waste is specifically handled at the facility.

Third, we did not analyze site-specific information for these TSDFs that may mitigate risks from natural hazards, such as steps specific facilities have taken to manage potential risks from selected natural hazards.[30] Our analysis is a screening-level analysis that evaluates whether TSDFs have exposure to climate-related hazards that could lead to facility risks, but it is not intended to provide estimates of actual risk for specific facilities. To evaluate the risk that a specific facility may face from existing natural hazard conditions or future conditions due to climate change (such as if climate change leads to an increase in the intensity or frequency of a natural hazard), site-specific information would need to be evaluated in conjunction with exposure information. Such site-specific analyses would be necessary to determine whether there is a risk to human health and the environment at TSDFs as a result of these hazards.

Fourth, while our analysis identifies facilities that are located in areas with natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change, our analysis does not reflect when, how, or at what rate conditions in these areas may change as the climate changes. The federal datasets we used in our analysis on flooding, wildfire, and storm surge are based on current or past conditions. Further, the National Climate Assessment has reported that climate change may exacerbate flooding, wildfire, storm surge, and sea level rise differently in certain regions of the U.S. According to NOAA officials, the regional average values we used in our analysis for sea level rise are more accurate than the national average; however, these officials said there may still be local variations of sea level rise of about 1 foot within each region.

Moreover, other natural hazards that may be exacerbated by climate change may also impact TSDFs, based on our review of the National Climate Assessment, EPA documents, previous GAO reports, and interviews with officials from EPA, authorized states, and stakeholder groups. These natural hazards include potential increases in saltwater intrusion (the movement of saline water into freshwater aquifers), permafrost melt, drought, hurricane winds, and extreme heat or cold temperatures. For example, more frequent or intense extreme heat conditions could lead to power outages that affect TSDFs, contribute to increased fire hazards, or cause high pressures in closed hazardous waste tanks that could lead to a release, according to documents we reviewed and interviews with officials from EPA, authorized states, and stakeholder groups. Increased drought conditions could increase wildfire risk or increase erosion of soil from landfill covers that protect against waste releases. Strong winds from hurricanes could damage facilities or units, such as hazardous waste tanks.

We did not analyze these other potential climate-related hazards as part of our mapping analysis because we did not identify relevant federal datasets for these hazards that fit the criteria for our analysis, such as being national in scope. See appendix II for more information about available federal data on the selected natural hazards that we analyzed for this report.

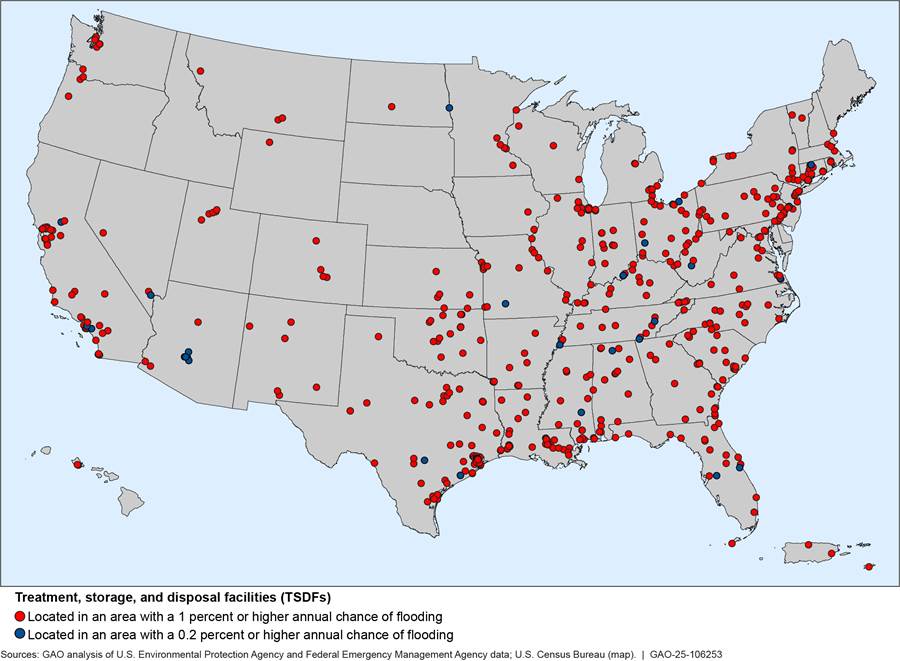

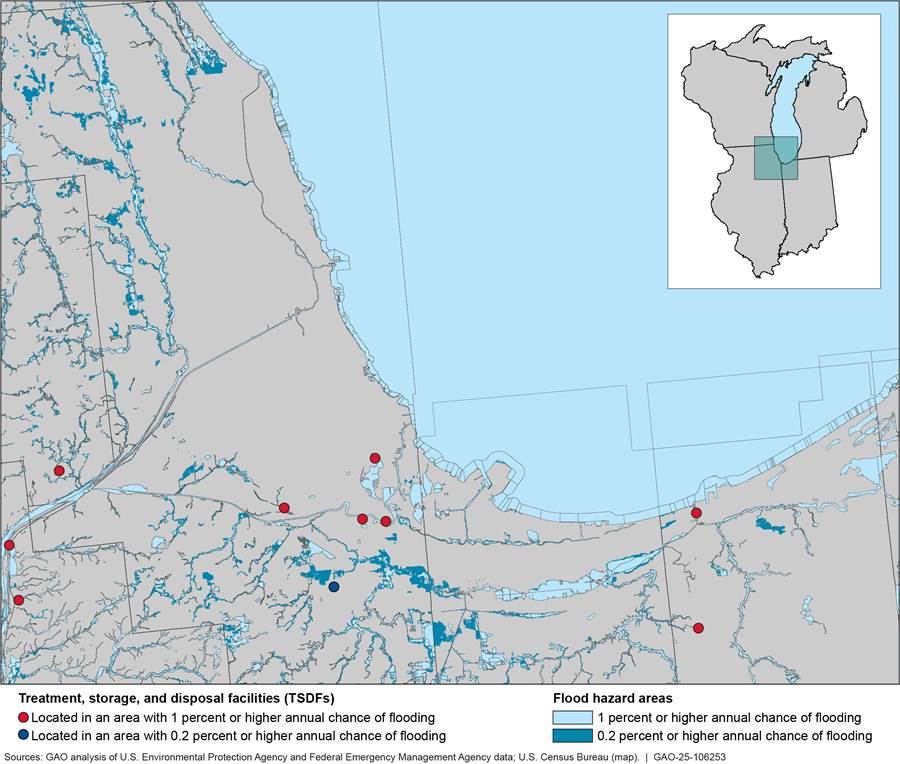

More Than 500 TSDFs Are Located in Areas That May Be Affected by Flooding

We identified 550 TSDFs—approximately 50 percent—that are located in areas that FEMA identified as having either high flood hazard or moderate flood hazard, as of 2023.[31] Of the 550 TSDFs that may be affected by flooding, 504 are located in areas with high flood hazard or a combination of high and moderate flood hazard, and 46 are located in areas with moderate flood hazard only (see fig. 4).[32] See appendix III for regional maps for flood and other hazards.

Figure 4: More Than 500 TSDFs Are Located in Areas That May Be Affected by Flooding, as of July 2023

Notes: We analyzed actively operating TSDFs and nonoperating TSDFs that have waste in place. To determine if a TSDF is located in an area with exposure to moderate or high flood hazard, we identified overlap between an estimated radius around a facility’s primary coordinates provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and flood hazard data provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Overlap indicates that a facility is located in an area that may be affected by the selected hazard. To show exposure to flooding, we use FEMA’s National Flood Hazard Layer, which estimates several levels of flood hazard, including high flood hazard (areas with a 1 percent or higher annual chance of flooding), and moderate flood hazard (areas with a 0.2 percent or higher annual chance of flooding). We approximated the boundaries of TSDFs using a radius around each facility’s primary geographic coordinates based on acreage data for the facility that EPA provided. Facility boundaries based on these data do not account for where hazardous waste is specifically handled at facilities and we did not analyze site-specific information for these TSDFs, such as steps that specific facilities have taken to manage potential risks from selected natural hazards. See appendix I for more details on our data analysis.

According to the National Climate Assessment, heavy rainfall is increasing in intensity and frequency across the United States and is expected to continue to increase, which may lead to an increase in flooding in the future. Flooding, including from extreme precipitation events, can affect TSDFs and pose risks to engineering or other waste management controls used to safeguard waste from being released.[33] For example, TSDF landfills have been damaged from storm events that surpassed their design standards for withstanding extreme precipitation, according to EPA regional officials and documents we reviewed. Additionally, secondary containment systems that are designed to manage rainfall and prevent releases from certain waste management units, such as tanks, or other TSDF stormwater management systems could be at risk of failure due to more frequent or intense precipitation events, according to documents we reviewed and interviews with state officials and a stakeholder group.

Nearly 400 TSDFs Are Located in Areas That May Be Affected by Wildfire

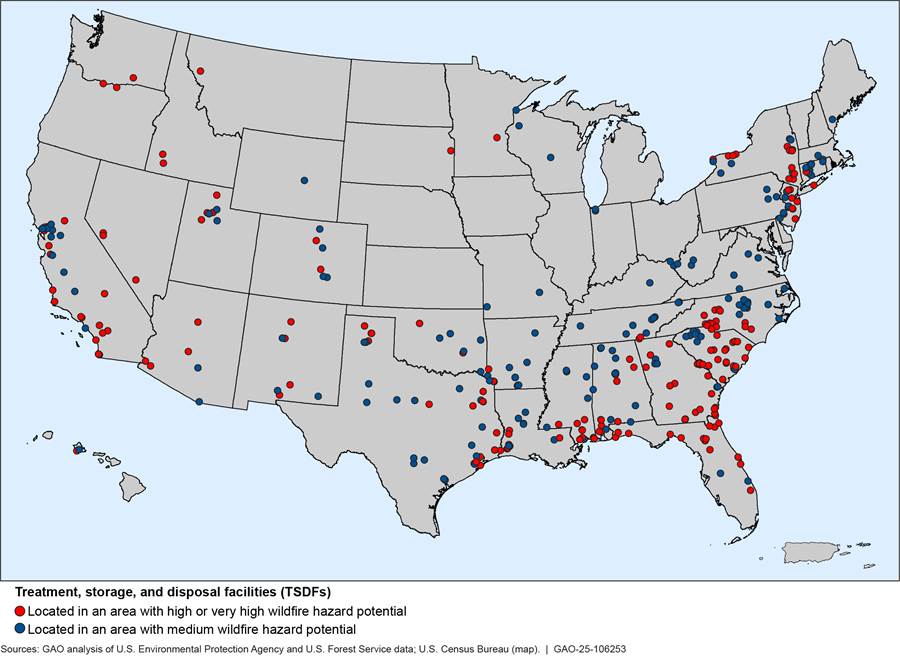

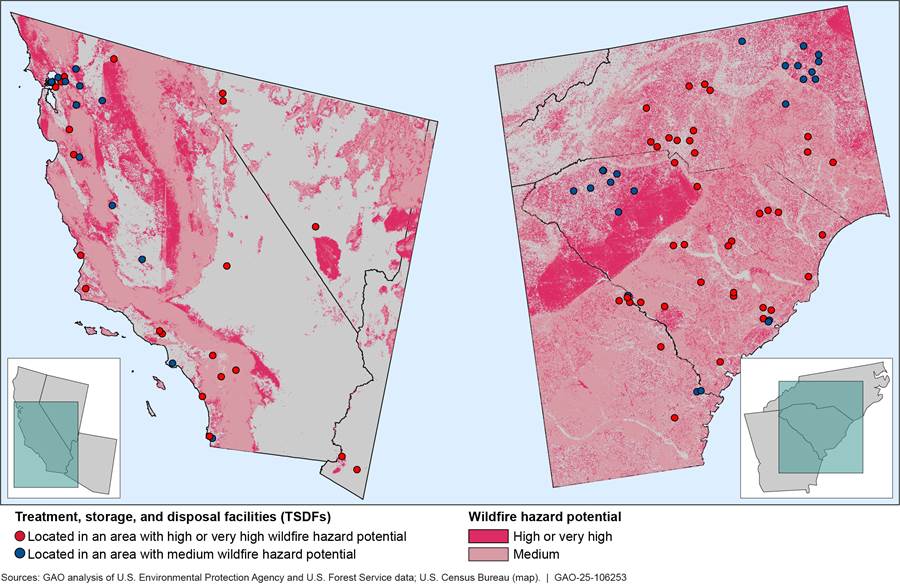

We identified 370 TSDFs—approximately 34 percent—that are located in areas that have very high, high, or moderate wildfire hazard potential, based on a U.S. Forest Service model as of 2023.[34] Of these facilities, 188 are located in areas with high or very high wildfire hazard potential, meaning they are more likely to burn with a higher intensity. An additional 182 facilities are located in areas with moderate wildfire hazard potential, which means they are less likely to experience high-intensity wildfire but could still be at significant risk of a wildfire occurring, according to U.S. Forest Service officials (see fig. 5). According to the National Climate Assessment, incidents of large forest fires are projected to increase in some parts of the United States, such as the southeastern and western United States and Alaska.

Notes: We analyzed actively operating TSDFs and nonoperating TSDFs that have waste in place. To determine if a TSDF is located in an area with wildfire hazard potential, we identified overlap between an estimated radius around facility coordinates provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and wildfire hazard potential data. Overlap indicates that a facility is located in an area that may be affected by the selected hazard. We used the U.S. Forest Service Wildfire Hazard Potential Map to show exposure to wildfire hazard potential. The map categorizes wildfire hazard potential into five classes: very low, low, moderate, high, and very high. We analyzed the moderate, high, and very high wildfire potential layers and combined results for the high/very high layers. We approximated the boundaries of TSDFs using a radius around each facility’s primary geographic coordinates based on acreage data for the facility that EPA provided. Facility boundaries based on these data do not account for where hazardous waste is specifically handled at facilities and we did not analyze site-specific information for these TSDFs, such as steps that specific facilities have taken to manage potential risks from selected natural hazards. See appendix I for more details on our data analysis.

Increasingly frequent or intense wildfire could increase the risk of contaminant releases from TSDFs, according to documents we reviewed and interviews with officials from EPA, one state program, and two stakeholder groups. Wildfire poses several risks to TSDFs. These include increasing the potential for on-site fires that could damage facility infrastructure or engineering controls used to safeguard waste, such as damage to landfills; overheating equipment; or causing high pressure in hazardous waste tanks. Some facilities may also handle ignitable wastes on-site, which could lead to explosions due to wildfire heat or flames. Further, wildfire could also disrupt electricity grids, causing a loss of power that could disrupt TSDF operations.

Nearly 200 TSDFs Are Located in Areas That May Be Inundated by Storm Surge

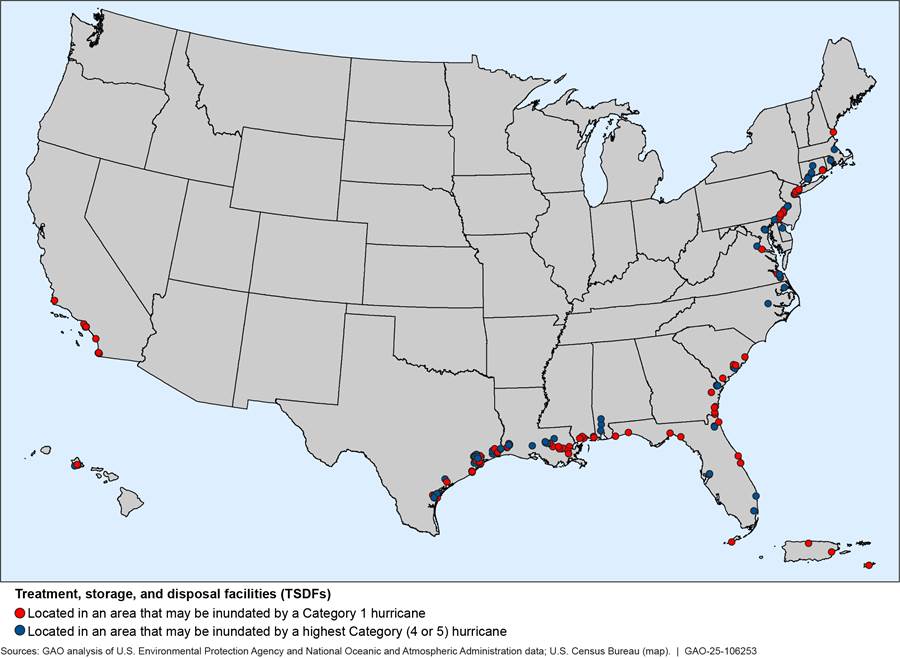

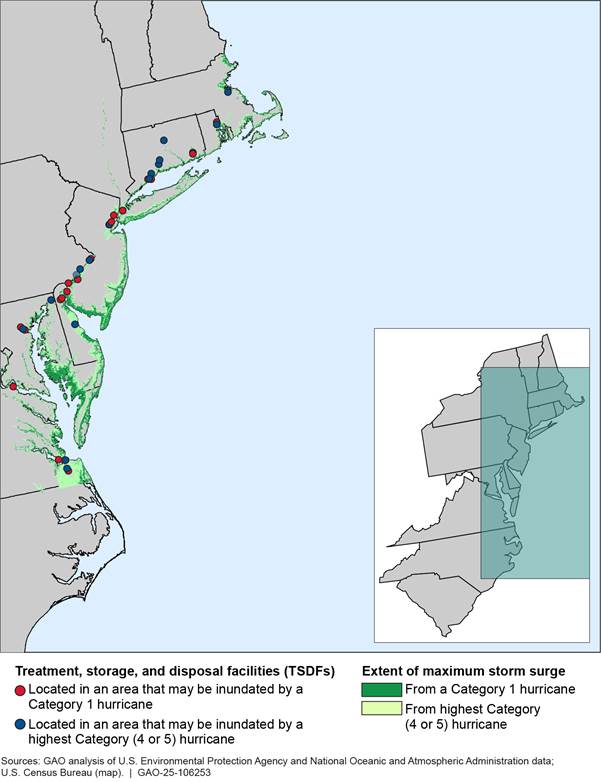

We identified 185 TSDFs—about 17 percent—located in coastal areas that may be inundated by storm surge corresponding to Category 4 or 5 hurricanes, the highest categories, based on NOAA’s storm surge model that uses data as of November 2023.[35] One-hundred seventeen TSDFs are located in areas that may be inundated by storm surge corresponding to a Category 1 hurricane (see fig. 6).

Notes: We analyzed actively operating TSDFs and nonoperating TSDFs that have waste in place. To determine if a TSDF is located in an area with exposure to hurricane storm surge, we identified overlap between an estimated radius around a facility’s primary coordinates provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and storm surge data. Overlap indicates that a facility is in an area that may be affected by the selected hazard. To show exposure to hurricane storm surge, we use the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Sea, Lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes Model, which estimates storm surge heights resulting from the various categories of hurricanes. We approximated the boundaries of TSDFs using a radius around each facility’s primary geographic coordinates based on acreage data for the facility that EPA provided. Facility boundaries based on these data do not account for where hazardous waste is specifically handled at facilities, and we did not analyze site-specific information for these TSDFs, such as steps that specific facilities have taken to manage potential risks from selected natural hazards. See appendix I for more details on our data analysis.

|

Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facility (TSDF) Emergency Response Measures to Prevent Hazardous Waste Releases from Hurricanes To secure a permit to handle hazardous waste, TSDFs must have a contingency plan designed to minimize hazards to human health or the environment from fires, explosions, or any unplanned sudden or nonsudden release of hazardous waste. As part of contingency plans, TSDF operators plan for and respond to emergencies caused by natural hazards, such as hurricanes, according to officials from two authorized states and a TSDF company we spoke with that operates two facilities along the Gulf Coast. For example, the TSDF officials that operate these two coastal facilities said they monitor hurricane predictions and begin implementing emergency response procedures several days in advance of a hurricane making landfall. These procedures include preparing flood control infrastructure, such as closing sea walls that protect the facility from storm surge, and taking other proactive measures, such as shipping storage drums inland to higher ground, securing tanks that cannot be moved, and moving mobile water pumping equipment into place. As a hurricane arrives, TSDF operations shut down and a small number of staff stay at the facility to manage emergency response actions, such as monitoring storm water management systems and pumping out excess water from facility areas to prevent hazardous waste releases due to flooding. Source: Interviews with authorized state officials and stakeholders, including a TSDF company that manages coastal facilities affected by hurricanes. | GAO‑25‑106253 |

According to the National Climate Assessment, climate change is expected to heighten hurricane storm surge, wind speeds, and rainfall rates.[36] Additionally, hurricanes are intensifying more rapidly and decaying more slowly due to climate change, leading to stronger storms that will extend farther inland and leave less time for preparing emergency measures. Storm surge from hurricanes can cause coastal flooding that may damage TSDFs and increase the risk that facility infrastructure or waste management controls will fail and lead to a release, according to EPA and documents we reviewed.[37] For example, hurricane storm surge could compromise the integrity of hazardous waste drums or flood indoor areas used to store waste piles, according to documents we reviewed. Further, more extreme coastal flooding could prevent emergency response personnel, equipment, and supplies from reaching a facility, according to documents we reviewed and interviews with a stakeholder group.

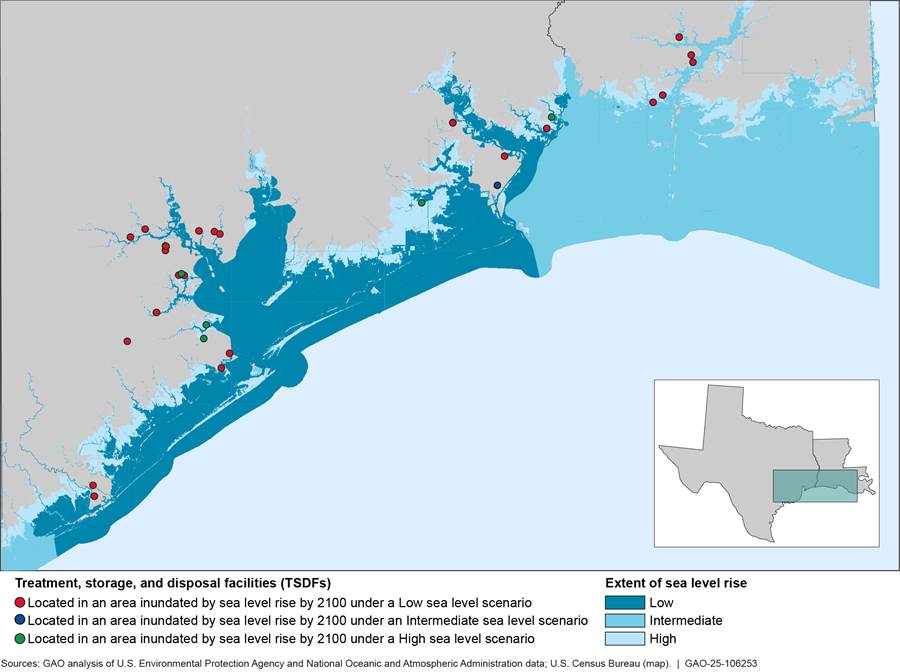

Over 100 TSDFs Are Located in Areas That May Be Affected by Sea Level Rise

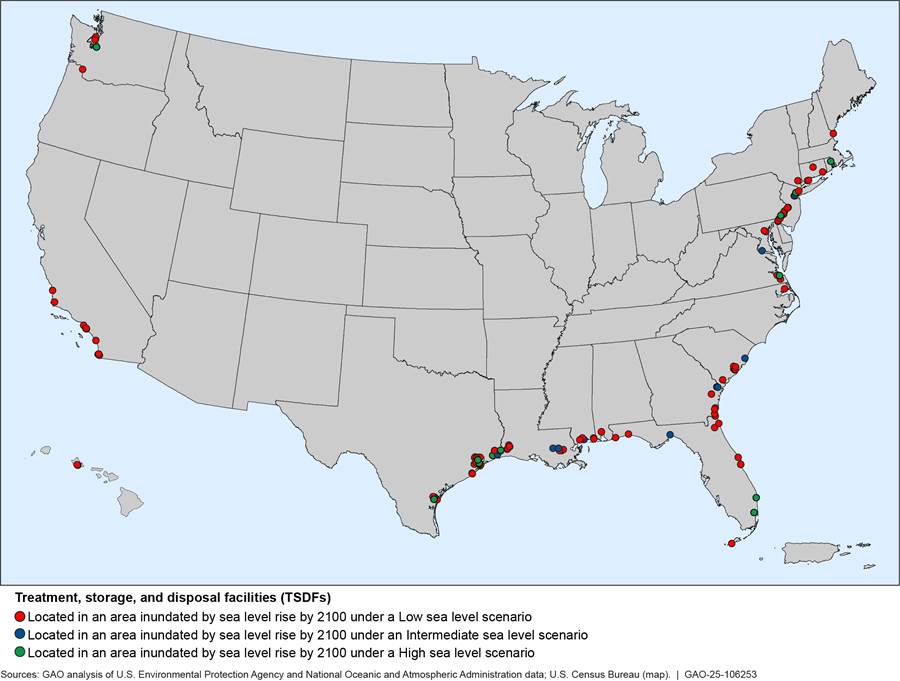

We identified 103 TSDFs—about 9 percent—located in coastal areas that may be inundated by sea level rise, according to our analysis of sea level rise projections from an interagency report covering sea level rise scenarios.[38] Of the 103 TSDFs that may be affected by sea level rise, 89 are located in areas that could be inundated by sea level rise by 2050 under the Intermediate sea level scenario. Two additional TSDFs may be affected by 2100 under the Low sea level scenario, and 12 additional TSDFs may be affected by 2100 under the Intermediate sea level scenario. Twenty-one additional TSDFs are located in areas that may be inundated by 2100 under the High sea level scenario (see fig. 7).[39] We analyzed the number of facilities in areas that may be affected by several different sea level rise scenarios because, according to the interagency report, relative sea levels along the U.S. coastline are projected to rise by about 2 feet to 7 feet by 2100, depending on the scenario.[40] Sea level rise is expected to increase coastal flooding by contributing to higher tides and storm surges that reach further inland.

Notes: We analyzed actively operating TSDFs and nonoperating TSDFs that have waste in place. To determine if a TSDF is located in an area with exposure to sea level rise, we identified overlap between an estimated radius around a facility’s primary coordinates provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and sea level rise projections from an interagency report covering sea level rise scenarios. Overlap indicates that a facility is located in an area that may be affected by the selected hazard. To show potential exposure to sea level rise, we used federal data for three sea level rise scenarios—Low, Intermediate, and High—for the year 2100. We used three scenarios for 2100 because of greater uncertainty for scenarios further in the future. These scenarios provide information on a range of potential outcomes that affect whether TSDFs will be exposed to this hazard. As a result, these scenarios are subject to uncertainty. The two primary limitations the report discusses for the sea level rise estimates we use include process uncertainty and emission uncertainty. Process uncertainty refers to uncertainty about the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on ice sheet loss, ocean expansion, and local ocean dynamics. Emission uncertainty refers to the uncertain amount of greenhouse gas emissions that will enter the atmosphere, trap heat, and affect temperature and sea level rise. We approximated the boundaries of TSDFs using a radius around each facility’s primary geographic coordinates based on acreage data for the facility that EPA provided. Facility boundaries based on these data do not account for where hazardous waste is specifically handled at facilities, and we did not analyze site-specific information for these TSDFs, such as steps that specific facilities have taken to manage potential risks from selected natural hazards. See appendix I for more details on our data analysis.

Storm surge coupled with sea level rise can lead to increased risk of hazardous waste releases from TSDFs due to flooding, according to documents we reviewed and interviews with officials from EPA, one state program, and two stakeholder groups. Additionally, sea level rise could lead to saltwater intrusion and changes to nearby groundwater levels, which threaten land-based units and post-closure unit hazardous waste control measures, according to officials from two EPA regions, one stakeholder group, and one authorized state.

EPA Has Efforts Underway to Manage Climate Risks to TSDFs, but Has Not Fully Clarified Its Authorities or Requirements or Assessed Risk Management Efforts

As part of meeting its strategic goal to tackle the climate crisis, EPA has started taking actions to incorporate climate adaptation into the RCRA hazardous waste program. For example, EPA has released climate adaptation implementation plans that identify the need to manage climate risks to TSDFs in permitting and compliance and enforcement efforts and issued guidance that directs EPA regions and authorized states to manage these risks. However, while EPA believes it has broad authority under RCRA to manage climate risks, EPA officials said regions and states needed more clarity and guidance on their authority and requirements to be able to do so. EPA has taken steps to clarify these authorities and requirements for RCRA permitting by issuing guidance that identifies broad authorities that regions and authorized states can use to develop permit requirements that require TSDFs to manage these risks.

However, some states and TSDFs may not implement this guidance unless EPA amends regulations to explicitly clarify authorities and requirements. EPA officials said that another way the agency could address this concern would be to develop and provide training and technical assistance to EPA regions and states to help them implement the guidance, but EPA has not developed and provided such training to them. Additionally, EPA officials said that, as part of upcoming rulemaking, they are considering seeking feedback on potential revisions to regulations to further clarify requirements and authorities for managing climate risks, but had not determined whether they would revise the regulations.

In addition, EPA has not assessed the extent to which authorized states and TSDFs have managed climate risks, nor has it developed metrics to do so.

EPA Has Set Broad Priorities to Manage Climate Risks Across the Agency and Taken Some Actions to Implement Them in the RCRA Hazardous Waste Program

As discussed above, in October 2021, EPA released its updated Climate Adaptation Action Plan with the goal of integrating climate adaptation into EPA programs, policies, rulemaking processes, and compliance and enforcement efforts. As required by the plan, all EPA national program and regional offices issued office-specific implementation plans, which outline each office’s plan to incorporate climate adaptation into their programs. As part of these efforts, in October 2022, EPA’s Office of Land and Emergency Management (OLEM) and Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA) issued implementation plans that include incorporating climate adaptation into their programs, including the RCRA hazardous waste program for TSDFs.[41] In June 2024, EPA released its updated Climate Adaptation Plan for 2024-2027. The plan highlights EPA’s planned actions for 2024 to 2027 to continue to make progress toward implementing its five priority action areas from the 2021 plan and strategic plan goals.[42]

OLEM and OECA have begun taking actions to incorporate climate adaptation into RCRA hazardous waste permitting (OLEM) and compliance and enforcement efforts (OECA). In addition, OLEM is collaborating with EPA’s Office of Research and Development to develop climate vulnerability screening tools for TSDFs. Table 5 shows actions that OLEM, OECA, and the Office of Research and Development have taken to incorporate climate adaptation into the RCRA program for TSDFs to prevent the release of hazardous waste.

|

Office of Land and Emergency Management (OLEM) |

· August 2022: OLEM issued national program guidance for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 that requires authorized states to (1) discuss in their work plans how they will address current EPA priorities, (2) describe how the states’ work plan tasks link to EPA’s Strategic Plan, and (3) include appropriate metric requirements in the grant criteria and workplan. This guidance encourages—but does not require—EPA regions and states to support and implement efforts to consider climate change when issuing permits to treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs). · May 2023: OLEM launched an interactive map of sea level rise around TSDFs along the U.S. coastline. According to EPA, EPA developed this climate screening tool to help states, regions, and TSDFs prepare for the impacts of climate change, independently assess their sea level rise vulnerabilities, and help inform actions they can take to become more resilient to climate change. · February 2024: To ensure that RCRA permits for TSDFs are adequately protective in a changing climate, OLEM issued guidance to all EPA regions that will require regions to include a term and condition on climate adaptation in RCRA grants issued to authorized states. The guidance notes that EPA regions may alter the wording of the term and condition slightly in negotiation with states, as long as the purpose of the term and condition is met. The term and condition language will require that permit decisions consider the potential for threats such as sea level rise, flooding, and extreme weather events, among other requirements. According to OLEM officials, the term and condition will be implemented in authorized state RCRA grant agreements from 2024 through 2027, given that authorized states will be applying for new grant agreements during this time frame. · June 2024: OLEM issued a memorandum to EPA regional division directors: “Implementing Climate Resilience in Hazardous Waste Permitting Under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).” The memorandum identifies selected RCRA regulatory authorities that EPA regions and authorized states could use to support additional permit requirements for TSDFs to manage climate risks. It also recommends site-specific screening analyses and more detailed vulnerability assessments as part of the TSDF permitting process to determine if adaptation measures are necessary to ensure TSDFs are resilient to climate risks. EPA states that it plans to release further policy and guidance regarding how permits can incorporate climate change adaptation considerations through a rulemaking currently in development. In addition, the memorandum notes that climate vulnerability screening tools and assessment methodologies are currently under development. OLEM officials said they plan to finalize these tools and assessment methodologies in January 2025. · July 2024: OLEM issued national program guidance for fiscal years 2025 and 2026. The guidance directs EPA headquarters to provide technical or policy support for regions and authorized states to do necessary climate adaptation work. It also directs headquarters to provide a tool for climate change hazard screening at the TSDF level using updated climate hazard data. The guidance also directs EPA regions and authorized states to ensure that RCRA permits issued to TSDFs are protective of human health and the environment for the duration of the permit, including under changing climate conditions. · Ongoing: OLEM is updating a guide to help EPA region and authorized state permit writers draft and review RCRA permit conditions that incorporate consideration of climate risks into TSDF permits. This guide—known as a model permit—is based on example language from actual permits and is expected to reduce the time to issue permits to TSDFs, promote national consistency, and result in clearer, more readily implementable and enforceable permit conditions. According to OLEM officials, sections of the model permit will address climate risks to TSDFs and will be made available to EPA regions, states, and TSDFs as they are completed. As of August 2024, OLEM had completed the permit cover page, which does not include information on climate risks. · Ongoing: OLEM is in the process of updating RCRA regulations to incorporate EPA policy changes and technical corrections and is considering revising the regulations to clarify requirements and authorities related to managing climate risks to TSDFs as part of this effort, according to OLEM officials. EPA expects to publish revisions for public comment in 2025. |

|

Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA) |

· August 2022: OECA issued national program guidance for fiscal years 2023 and 2024. The guidance states that OECA intends to use RCRA authorities to proactively investigate and prevent threatened hazardous releases in climate-sensitive communities, which may include hazardous waste releases from TSDFs. · September 2023: OECA issued a memorandum on EPA’s climate compliance and enforcement strategy. This memorandum requires all EPA compliance and enforcement offices, including those that oversee and enforce the RCRA hazardous waste program, to address climate change in every matter within their jurisdiction, as appropriate. For example, the memorandum states that enforcement staff should ensure consistent consideration of climate change in the case development process and incorporate relevant climate adaptation considerations in administrative, civil, and criminal enforcement actions, which could apply to enforcement actions against TSDFs. · March 2023: OECA released updated guidance for state review framework evaluations conducted in fiscal years 2024 through 2028. The state review framework provides a consistent process for evaluating the performance of and compliance with selected EPA programs, including RCRA, in authorized states. The guidance encourages EPA regions to incorporate climate change as an optional state review framework evaluation criteria associated with inspections, noncompliance, and enforcement actions for states that have specifically incorporated climate change into their state’s compliance monitoring strategy. · July 2024: OECA issued national program guidance for fiscal years 2025 and 2026. The guidance states that OECA and EPA regions will continue to use RCRA authorities to proactively investigate and prevent hazardous waste releases in climate-sensitive communities, among other directives. |

|

Office of Research and Development |

· 2023: The Office of Research and Development established the Integrated Climate Sciences Division. According to EPA documentation, the division provides client services to EPA regional offices and delivers quantitative assessments of climate changes, regionally relevant assessments, technical assistance, and capacity building to support climate adaptation planning. According to OLEM officials, the division also advises states on making climate-smart investments, including investments relevant to the RCRA hazardous waste program. |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documentation and interviews with EPA officials. | GAO‑25‑106253

Note: The EPA actions described relate to preventing hazardous waste release from operating TSDFs and nonoperating TSDFs with waste in place. EPA actions related to corrective action are not included.

|

Stormwater and Erosion Analysis by EPA’s Region 9 and Office of Research and Development Officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Region 9 noted that the region has recently experienced several high-intensity storm events that exceeded the federal minimum design standard of controlling stormwater from a 25-year, 24-hour storm. As a result of such storms, stormwater controls and landfill covers at hazardous waste landfills were damaged. For example, a treatment, storage, and disposal facility (TSDF) located in Region 9 experienced a down-drain failure and stormwater flowed down the landfill slope instead of through the drains, causing ruptures in the soil and a potential breach of hazardous waste. Region 9 has initiated an Inflation Reduction Act-funded contract with EPA’s Office of Research and Development to conduct research that assesses stormwater and erosion controls at three TSDF landfills in Region 9. The research is expected to provide design recommendations, including revised landfill design for storm events that take into account potential climate change. Source: GAO analysis of EPA Region 9 information. | GAO‑25‑106253 |

Selected EPA regions have also begun taking various actions to build their capacity to manage climate risks to TSDFs or encourage authorized states and TSDFs to manage climate risks. For example, in June 2022, Region 9 issued a memorandum to implement climate change resiliency into the region’s permitting process.[43] This memorandum directs Region 9 RCRA project managers to require TSDFs to evaluate permitted facilities for climate change threats. It also directs project managers to take appropriate actions to ensure that control measures to address these risks are included in EPA approvals of permits. In addition, Region 9 is working with the EPA Office of Research and Development to conduct a stormwater and erosion analysis to assess controls at TSDF landfills and provide design recommendations to account for climate risks. Region 5 developed a checklist specifically for TSDF inspections that includes climate risk considerations.

EPA Believes It Has Broad Authority to Manage Climate Risks but Has Not Fully Clarified These RCRA Authorities or TSDF Requirements

While EPA believes the agency has broad authority under RCRA to manage climate risks to TSDFs, we found that regions, states, and TSDFs need more clarity on RCRA authorities and requirements for managing climate risks. EPA officials agreed that more clarity would be helpful. EPA also has not fully clarified these requirements as part of its key RCRA oversight mechanisms of authorized state programs. Further, some authorized states and TSDFs may not manage these risks until EPA revises regulations to include explicit authorities or requirements for states and TSDFs to manage these risks.

EPA Believes RCRA Regulations Grant Broad Authority to Manage Climate Risks, with Some Limitations on Compliance and Enforcement Efforts

While RCRA regulations do not include explicit requirements on climate change, EPA officials believe that RCRA grants EPA and authorized states broad authority to manage climate risks to TSDFs. EPA’s RCRA regulations do not include any standards and requirements that specifically mention climate change or that are directly intended to manage climate risks to TSDFs. However, while RCRA regulations do not explicitly mention climate risks, officials from EPA headquarters and regions and three stakeholder groups said that existing regulations could be interpreted as broad enough to address some climate risks that TSDFs face. These officials also said that some states and TSDFs may already be addressing climate risks as part of broad risk management efforts to prevent hazardous waste releases. For example, EPA headquarters and regional officials said that TSDF contingency plans are required to prevent or mitigate the release of hazardous waste from any potential cause—which could include consideration of climate risks.[44]

Additionally, officials from EPA’s Office of General Counsel and OLEM said that EPA has extensive authority under RCRA to address risks to human health and the environment related to hazardous waste management, including from climate change. These EPA officials said that there are both general and specific RCRA provisions that give EPA regions authority to require authorized states and TSDFs to manage climate risks. For example, there are broad requirements for TSDFs to minimize the possibility of hazardous waste releases. The officials noted that authorized states or EPA regions could use these requirements to justify including permit requirements for these facilities that would address climate risks that could affect the potential for a release.[45]

Officials from EPA’s Office of General Counsel said that authorized states would have the same broad authorities as EPA regions to manage climate risks as part of both permitting and compliance and enforcement, given that they are authorized to implement the federal hazardous waste program for TSDFs in lieu of EPA. Additionally, OLEM officials said that RCRA regulations should be seen as setting minimum standards and requirements for TSDFs. They noted that EPA regions and authorized states have authority to develop permit conditions that go above these standards, if additional measures are needed to manage climate risks.

OECA officials also said that some RCRA regulations could be interpreted as broad enough to provide authority for EPA regions and authorized states to manage climate risks to TSDFs as part of compliance and enforcement efforts. For example, OECA officials said that RCRA inspectors might be able to evaluate whether TSDFs are managing climate risks as part of their facilities’ contingency plans. Additionally, officials from one EPA region said that regions might be able to require TSDFs to manage climate risks as part of compliance and enforcement efforts if certain conditions are met.[46] There also could be opportunities for EPA regions and authorized states to manage climate risks to TSDFs through the settlement negotiation process during enforcement actions, according to officials from two EPA regions, one state program, and one stakeholder group.

Although compliance and enforcement efforts may present opportunities for EPA regions and states to manage climate risks at TSDFs, OECA officials said the lack of explicit RCRA requirements to manage these risks places some limitations on EPA’s and states’ authority to do so.

EPA Regions, Authorized States, and TSDFs Need More Clarity on Authorities or Requirements for Managing Climate Risks under RCRA

While OLEM believes that EPA has broad authority to manage climate risks as part of the permitting process, OLEM officials also said that EPA regions and authorized states needed more clarity on their authority to manage climate risks to TSDFs and guidance on interpreting which regulations could be used to develop requirements. Additionally, OECA officials said that there is not a uniform practice for managing these risks as part of RCRA compliance and enforcement efforts. They noted that OLEM is in the process of defining requirements and developing guidance related to managing climate risks to prevent hazardous waste releases.[47] As a result, OECA officials said the extent to which regions or states are managing these risks as part of compliance and enforcement efforts could vary, given there are not currently any explicit national requirements.

We also found that EPA regions, authorized states, and TSDFs need more clarity on whether managing climate risks is required under RCRA regulations or they have authority to do so as part of RCRA hazardous waste permitting and compliance and enforcement. For example:

· Officials from four of the five EPA regions in our review said they had not taken any specific actions to manage climate risks to TSDFs as part of permitting or compliance and enforcement. They said they needed more clarity on RCRA authorities and requirements to be able to ensure authorized states and facilities manage these risks. For example, officials from three regions said they did not have any formal direction on authorities or requirements for managing climate risks to TSDFs and are waiting for EPA headquarters to provide guidance.

We did not identify any examples of EPA regions using RCRA authorities or requirements to manage climate risks to TSDFs, including those that OLEM and OECA cited as potential sources of authority. For example, we did not find that any selected EPA regions had reviewed or required any updates to TSDF contingency plans in order to manage climate risks as part of compliance and enforcement efforts. According to OECA officials, one EPA region is considering conducting comprehensive reviews of flood risk during inspections but has not yet done so.

· Officials from three authorized states told us that EPA had not clarified what requirements exist for states or TSDFs to manage climate risks as part of the RCRA hazardous waste program. They said their authorized state programs had not taken any specific actions to manage these risks as part of permitting and compliance and enforcement. For example, officials from one authorized state said they had not had any communication with EPA on managing climate risks to TSDFs or what requirements may exist. Further, one stakeholder group said EPA had not clarified what authorized states would specifically be required to do in order to manage these risks to TSDFs. Officials from two EPA regions also said that they did not believe it was clear to states or TSDFs if managing climate risks was required under RCRA or if states had the authority to do so.

· TSDFs have not been required to manage climate risks by EPA or authorized states, according to officials from two stakeholder groups, including a TSDF industry association. We reviewed permits, contingency plans, and inspection reports from eight TSDFs located within the five selected states and found that none of the documents identified, assessed, or addressed any future climate change risks on the facility or waste management units or included any specific requirements for the TSDF to do so. All eight TSDFs in our review accounted for at least some current natural hazard risks in their contingency plans or permits. However, none of the plans or permits we reviewed identified how climate change might exacerbate natural hazard risks or described any climate adaptation measures or other controls being taken to specifically address any future climate risks.[48] For example, no plans or permits described climate adaptation measures that would address additional hazard risks above what may be expected from current weather and natural hazards the facility may face.

EPA Has Not Fully Clarified Requirements for Regions or Authorized States on Managing Climate Risks as Part of Key Oversight Mechanisms

EPA also has not fully clarified requirements on managing climate risks as part of its key oversight mechanisms used to ensure state compliance with RCRA requirements. Both OLEM and OECA provided national program guidance for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 to EPA regions and authorized states that reflect minimum requirements for the state work plans. However, this guidance does not include requirements to manage climate risks to TSDFs in the hazardous waste program.[49] In addition, we found that four out of the five selected EPA regions did not have requirements or regional guidance for authorized states to include work plan goals or commitments to manage climate risks to TSDFs.[50]

Furthermore, authorized state work plans for the hazardous waste program generally did not include commitments or goals related to managing climate risks. For example, 20 of the 25 state hazardous waste program work plans we reviewed had no climate-related goals for TSDFs. The other five states included commitments or goals that could relate to managing climate risks to TSDFs. OLEM officials said some of EPA’s regions face challenges convincing some states to commit to goals on managing climate risks in work plans. They said this is because climate change is a politically charged issue for these states and their programs may not consider it a priority or requirement to manage climate risks to TSDFs.

Additionally, OECA uses the state review framework as a primary oversight tool to evaluate whether authorized state compliance monitoring and enforcement programs are ensuring TSDF compliance with RCRA requirements. However, OECA officials said the framework does not include reviewing whether states manage climate risks for TSDFs because there are no national RCRA policies, guidance, or regulatory requirements that require regions or states to manage these risks as part of their compliance and enforcement programs.[51] Table 6 summarizes our findings on the extent to which climate risks are mentioned in TSDF and key EPA oversight documents we reviewed.

|

TSDF and key EPA oversight documents |

Extent climate risks are mentioned |

|

TSDF permits, contingency plans, and compliance inspection reports |