SHIPBUILDING AND REPAIR

Navy Needs a Strategic Approach for Private Sector Industrial Base Investments

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Shelby S. Oakley at (202) 512-4841 or oakleys@gao.gov and Diana Maurer at (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106286, a report to congressional committees

Navy Needs a Strategic Approach for Private Sector Industrial Base Investments

Why GAO Did This Study

The Navy plans for a larger, more capable fleet of ships to counter evolving threats. But the Navy has struggled to increase the size of the fleet for the past 2 decades. Its performance in shipbuilding and ship repair is critical to achieving the desired future fleet.

Senate Report 116-236 includes a provision for GAO to examine the ship industrial base. GAO’s report examines the extent to which (1) the industrial base can support Navy shipbuilding and repair; (2) DOD supports the ship industrial base and assesses its support; and (3) the Navy has a strategic approach to the industrial base.

GAO analyzed DOD and Navy data and documentation; interviewed agency officials and all companies conducting complex repairs for surface ships and major shipbuilding; and conducted site visits.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations to DOD, including that it improves visibility across investments; and that the Navy establish metrics for its investments; assess its repair needs; and create a ship industrial base strategy. DOD did not provide formal comments on this report, but the Navy noted in draft comments that it generally concurred with the substance of the recommendations. The Navy stated that one of the six recommendations should include additional parties within the Navy. GAO agreed and adjusted the recommendation accordingly.

What GAO Found

The private companies that the Navy contracts with to build vessels and repair surface ships are key components of the Navy’s ship industrial base. These private companies augment the repair work conducted at the Navy’s public shipyards.

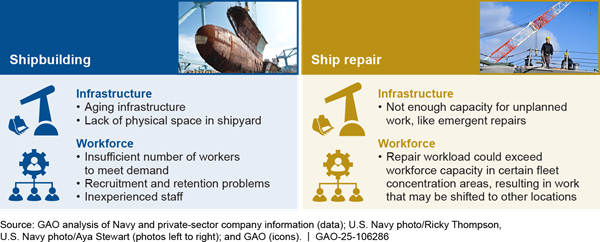

Ship Industrial Base Struggles to Meet the Navy’s Goals

· Shipbuilding.

The shipbuilding industrial base has not met the Navy’s goals in recent

history. The Navy’s shipbuilding plans have consistently reflected a larger

increase in the fleet than the industrial base has achieved. Yet, the Navy

continues to base its goals on an assumption that the industrial base will

perform better on cost and schedule than it has historically. The shipbuilders

have infrastructure and workforce challenges that have made the Navy’s goals

difficult to accomplish.

· Ship repair. The Navy has not historically met ship repair goals, but it has improved since 2019. The industrial base has grown since then, and representatives from some companies that GAO spoke with stated they often had more capacity than the Navy used. But companies may not be able to take on unplanned work due to infrastructure or workforce limitations. For example, a dry dock of the right size may not be empty when needed.

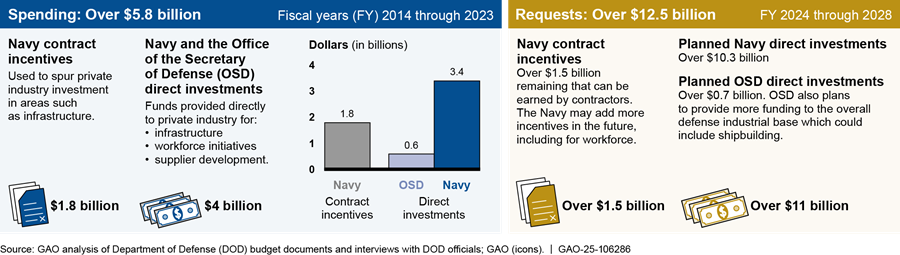

DOD Invests Billions to Support the Shipbuilding Industrial Base

The Department of Defense (DOD)—specifically the Navy and Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)—spent billions to support the shipbuilding industrial base. This included funding for infrastructure and workforce improvements for shipbuilders and their suppliers. But it has yet to fully determine the effectiveness of that support (i.e., its return on investment), though it has taken steps to do so. More specifically, DOD spent over $5.8 billion on the shipbuilding industrial base from fiscal years 2014 through 2023. It plans to spend an additional $12.6 billion through fiscal year 2028. DOD spent this funding on contract incentives and direct investments.

However, the Navy and OSD are not fully coordinating their shipbuilding investments to prevent duplication or overlap in spending. For example, the Navy and OSD do not coordinate across all investment efforts—such as between submarines and surface ships—though they both make related investments in workforce and infrastructure for these ship categories. Further, the Navy has yet to fully establish performance metrics, such as measurable targets that link to the agency’s goals that would enable it to consistently evaluate the effectiveness of its investments in building a larger fleet or achieving other intended outcomes. Without better visibility across investments and established performance metrics, the Navy and OSD cannot ensure their investments in the shipbuilding industrial base are an effective use of federal funds to help build a larger fleet.

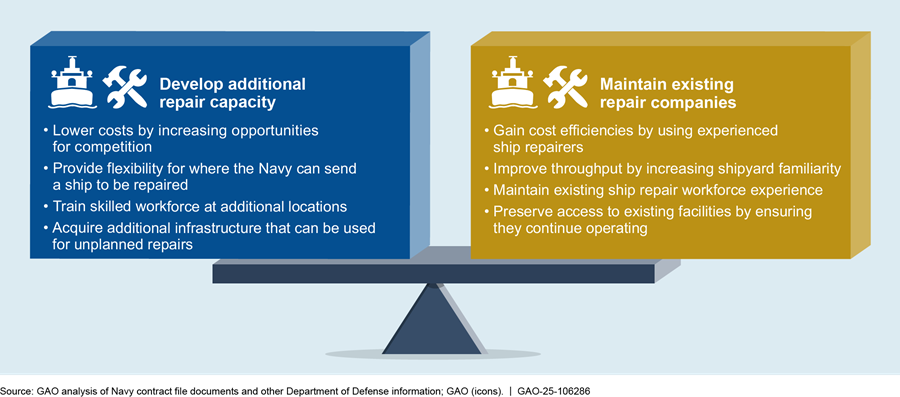

The Navy plans to make direct investments in the ship repair industrial base as it has for shipbuilding. However, the Navy has yet to fully assess how much infrastructure, such as dry docks, it needs to meet its ship repair goals when considering other than peacetime needs. Without understanding its needs, the Navy risks funding more infrastructure than necessary, which could interrupt the competitive environment.

The Navy Has Not Developed a Strategy for Managing the Ship Industrial Base

The lack of an overall strategy to guide management of the ship industrial base hinders Navy efforts to address several challenges, such as:

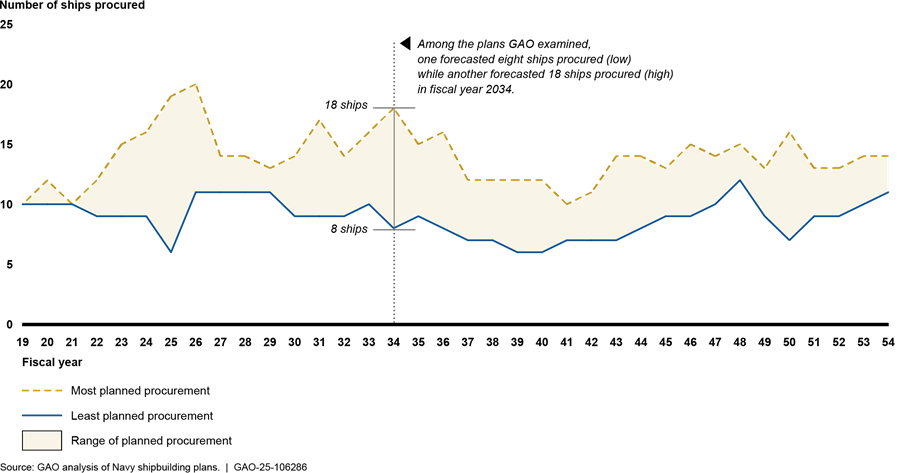

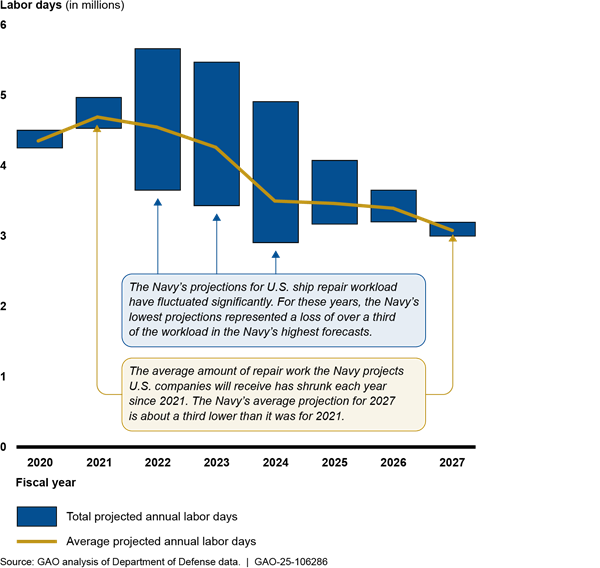

· Changing plans for future work. The Navy has struggled to provide industry with a stable workload projection. The Navy’s plans for building and repairing ships vary from year to year, hindering efforts to encourage the industry to invest in needed infrastructure.

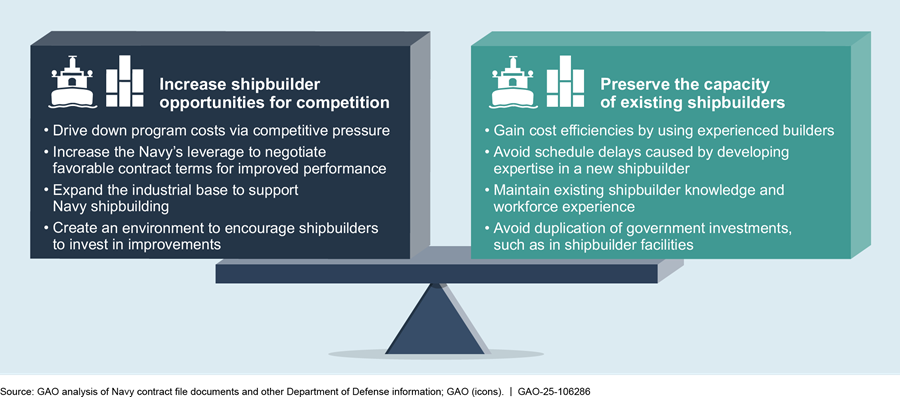

· Competing priorities. The Navy seeks to increase opportunities for competition in shipbuilding and repair, while simultaneously seeking to protect existing companies. These priorities can be at odds. A more competitive environment could help expand the industrial base, but some companies could struggle to remain viable if they do not win contracts.

Developing a ship industrial base strategy would help the Navy better address these challenges to improve the likelihood of achieving its shipbuilding and ship repair goals. GAO’s prior work has shown that a consolidated and comprehensive strategy enables decision-makers to better guide program efforts and assess results. GAO also previously identified desirable characteristics that a national strategy should include. DOD issued its national industrial strategy in November 2023. However, Navy officials told GAO that it established a new program office in September 2024 that will be positioned to develop a strategy for the ship industrial base. Officials said they plan to have additional details available in early 2025. Until the Navy implements a ship industrial base strategy, it will not be able to effectively align or assess its actions to manage the industrial base for shipbuilding and repair.

Abbreviations

|

ASN (RD&A) |

Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition |

|

AUKUS |

Australia, United Kingdom, and United States Trilateral Security Partnership |

|

DASN |

Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy |

|

DDG 51 |

Arleigh Burke class destroyers |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DPA |

Defense Production Act |

|

FY |

Fiscal Year |

|

IBAS |

Industrial Base Analysis and Sustainment |

|

NAVSEA |

Naval Sea Systems Command |

|

OSD |

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

|

OUSD(A&S) |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment |

|

PEO |

Program Executive Office |

|

SUBMEPP |

Submarine Maintenance Engineering, Planning and Procurement |

|

SUPSHIP |

Supervisor of Shipbuilding, Conversion, and Repair |

|

SURFMEPP |

Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program |

|

VCS |

Virginia class submarine |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Congressional Committees

February 27, 2025

The U.S. Navy is engaged in an era of strategic competition with near peer adversary nations that are rapidly modernizing and expanding the size of their naval forces, according to the Department of Defense (DOD). The Navy is concerned that these nations’ maritime ambitions threaten its dominance at sea, and thereby U.S. national security interests. In the face of this threat, the Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan for America’s Warfighting Navy 2024 from September 2024 calls for action to develop a larger, more lethal, and ready fleet.[1] The Navy’s performance in both shipbuilding and ship repair is critical to achieving the desired future fleet, but our recent work has shown that the Navy continues to fall short of its goals in these areas.[2]

By fiscal year 2026, the Navy expects to have no more ships than it did when it released its first 30-year shipbuilding plan in 2003 due to a combination of slower than expected new ship construction and the decommissioning of older ships. Since 2004, the Navy has nearly doubled its shipbuilding budget, after adjusting for inflation. At the same time, the Navy has accrued a backlog of surface ship maintenance—which reached $2.3 billion in deferred work by August 2022—that influenced it to propose retiring some ships early.[3] To achieve its goals for a larger future fleet, the Navy will need to reverse these trends and construct and deliver more capable ships on time while maintaining the readiness of a larger number of ships.

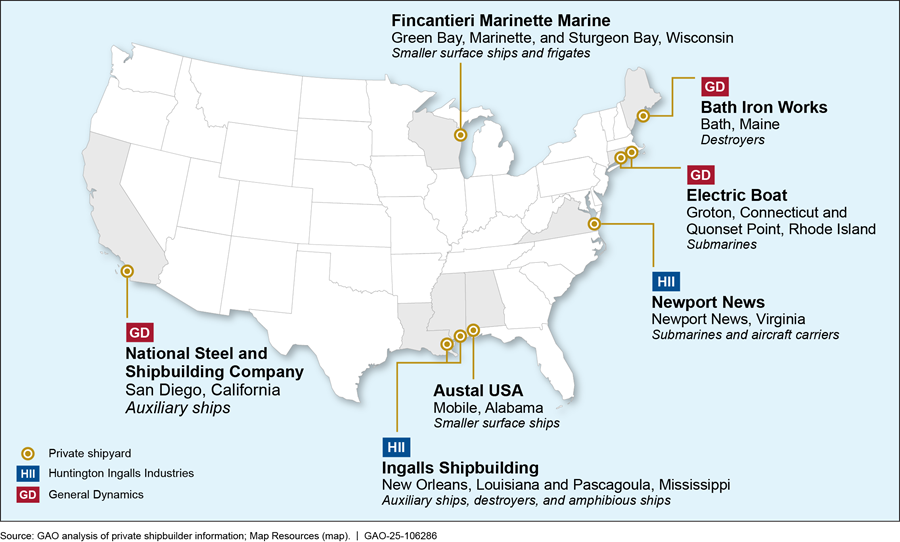

The Navy relies on private companies as a key element of the industrial base to build—and in many cases—repair its ships. However, the Navy has identified a “boom and bust” pattern of shipbuilding in recent history as responsible for diminished capacity in the shipbuilding industrial base. The Navy reported that 17 private shipyards that construct ships for the defense industry closed or left the defense industry over the last 50 years. In 2021, there remained roughly 25 shipyards in the United States constructing medium- to large-sized vessels. Seven of these shipyards construct Navy battle force ships.[4]

Further, with an aging fleet and significant operational requirements, a robust private sector ship repair industrial base capacity will be imperative. Private companies that use both Navy facilities and their own shipyards perform most ship repair periods, including maintenance on the Navy’s surface ships, such as cruisers, destroyers, and amphibious ships.[5] Although the Navy spends billions annually to sustain its ships, our work has found persistent sustainment challenges across the surface fleet, including maintenance delays and degraded material condition.[6]

Senate Report 116-236 accompanying the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 includes a provision for us to examine the industrial base for Navy shipbuilding and ship repair.[7] This report focuses on the capability and capacity that private industry provides to support Navy shipbuilding and repair efforts, which for the purposes of this report, we refer to as the ship industrial base.[8] This report examines (1) the extent to which the industrial base can support the Navy’s shipbuilding and repair goals; (2) the extent to which DOD is taking actions to support the ship industrial base and determining the effectiveness of those actions; and (3) the extent to which the Navy is taking a strategic approach to address the challenges it faces managing the ship industrial base to meet is long-term shipbuilding and repair goals.

To determine the extent to which the industrial base can support the Navy’s shipbuilding and repair goals, we analyzed shipbuilding programs for the Navy’s battle force; major repair periods for the Navy’s nonnuclear surface fleet; our prior work; and DOD, Navy, and contractor documentation. We also analyzed the Navy’s annual Long-Range Plan for the Construction of Naval Vessels for fiscal years 2015 through 2025 and the annual Long-Range Plan for Maintenance and Modernization of Naval Vessels for fiscal years 2023 through 2025 (the most recent years available).

To assess the extent to which DOD is taking actions to support the industrial base, we reviewed DOD and Navy budget and briefing documents. We compared DOD’s efforts to assess the effectiveness of its investments and incentives to selected standards for internal control.[9] Specifically, we examined DOD’s efforts to track, assess, and ensure visibility among its ship industrial base investments against internal control principles. We focused on comparing these efforts against internal controls that emphasize management’s responsibility to obtain relevant data in a timely manner for effective monitoring; design control activities to achieve objectives, such as activities to monitor performance measures and indicators; and to communicate quality information to help the entity achieve its objectives and address related risks. We focused on DOD efforts to provide financial support to the ship industrial base from fiscal years 2014 through 2023.[10]

To determine the extent to which the Navy is taking a strategic approach to addressing challenges with managing the industrial base, we interviewed Navy officials and reviewed the Navy’s long-range planning documents for shipbuilding and repair. We also analyzed changes in all the Navy’s long-range planning documents, such as the Navy’s ship procurement plans, and forecasted repair workload for October 2019 to April 2024. We also reviewed contract file documents related to non-competitive contract awards and Navy documentation and interviews for information about how the Navy is managing the industrial base and managing its competing priorities. Further, we assessed DOD’s National Defense Industrial Strategy for information related to the industrial base for shipbuilding and repair.[11] We also examined the Navy’s organizational structure against the statutory authorities of Navy leadership for overseeing ship acquisition and sustainment, including repair, and the associated industrial base.[12]

In support of all our objectives, we also conducted over 50 interviews with government officials and private industry representatives. These interviews included DOD and Navy officials; all seven shipbuilders the Navy uses for its battle force ships; and 12 companies eligible to conduct complex repair work on the Navy’s nonnuclear surface ships. Many of the companies conducting ship repair have facilities in multiple locations. We conducted site visits to meet with representatives from ship repair companies in Mayport, Florida; Norfolk, Virginia; San Diego, California; and Seattle/Everett, Washington; and interviewed representatives from some of these companies from more than one location to gain perspectives on region-specific topics. We also interviewed representatives from key supplier consortiums—which represent multiple suppliers that produce similar materials—to gain perspectives about challenges facing the supplier base. See appendix I for more information about our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2022 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Some of the companies we interviewed to inform our analysis identified some of the information they provided to us as being business sensitive, which must be protected from public disclosure. Therefore, this report omits sensitive information on the companies’ workforce, infrastructure, and subcontracts. One company, Bath Iron Works, did not respond to several requests to validate if information obtained from the company could be cleared for public release. We therefore omitted some information obtained from Bath Iron Works in this report.

Background

Navy Long-Range Planning for Shipbuilding and Ship Repair

30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

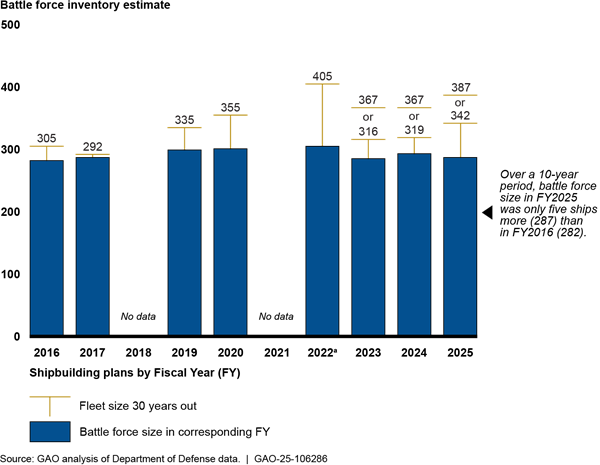

The Navy outlines its shipbuilding plans in an annual long-range shipbuilding plan, which is often referred to as the 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan (hereafter referred to as the shipbuilding plan). Statute requires the Navy to produce the shipbuilding plan, which should include details on the construction of Navy ships over the next 30 fiscal years and information about the force structure needed to align with the most recent national security or defense strategy.[13]

|

The Navy Shipbuilding Plan and the Australia, United Kingdom, and United States (AUKUS) Trilateral Security Partnership The Navy’s shipbuilding plan states that it has yet to fully reflect the AUKUS agreement, which was announced in September 2021 and updated in 2024, though this will be updated in future plans. According to the White House announcement, one effort under the September 2021 AUKUS partnership agreement was to provide Australia with a conventionally armed, nuclear powered submarine capability as soon as possible. According to the announcement, pending Congressional approval, the U.S. intends to sell Australia three Virginia class submarines in 2030, with the potential to sell two additional submarines if needed. The Navy’s Fiscal Year 2025 Long-Range Shipbuilding Plan states that the Navy envisions selling in-service Virginia class submarines to Australia in fiscal years 2032 and 2035 and delivery of a new submarine in fiscal year 2038. Navy officials told us that they planned to build new submarines to replace those sold to Australia. However, the shipbuilding plan has yet to reflect the rates of production that would enable the submarines to be replaced. Source: GAO analysis of Navy information. | GAO‑25‑106286 |

The Navy produced its first shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2004 in response to the statutory requirement.[14] Since that time, the Navy’s plans have reflected a range of desired fleet sizes—all calling for a significant growth in fleet size—based on changes to its analysis of the force structure it needs. The Navy’s most recent force structure analysis from June 2023, which serves as the basis for the fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan, called for a fleet of 381 battle force ships. According to the Navy, battle force ships are warships capable of contributing to combat operations or that contribute directly to Navy warfighting or support missions. This requires significant growth from the Navy’s fleet of 296 ships as of September 2024.[15] For additional information about the Navy’s shipbuilding plan and force structure analysis since 2016, see appendix II.

Long-Range Maintenance Plan

Statute requires the Navy to produce an annual Long-Range Plan for Maintenance and Modernization of Naval Vessels (hereafter referred to as the maintenance plan). The Navy has done so in response to statute since 2023. According to the statute, the maintenance plan should provide forecasted repair and modernization requirements for the current fleet and future ships included in the shipbuilding plan, and a description of Navy initiatives intended to increase ship repair industrial base capacity.[16]

Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Industrial Base

The industrial base for Navy shipbuilding and ship repair is a subset of the defense industrial base. This industrial base is comprised of a combination of people, technology, institutions, and facilities used to design, develop, manufacture, and maintain the weapons needed to meet U.S. national security objectives.[17] The private companies in the defense industrial base can be divided into tiers: top tiers that include prime contractors and major subcontractors, and lower tiers that include suppliers of parts and materials. The Navy also relies on organic industrial installations that are government owned and operated, which include four public shipyards that repair nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers.[18] While we did not examine the public shipyards in this report, they are part of DOD’s organic industrial base.[19]

At the prime contractor level, the Navy primarily uses seven private shipyards for its shipbuilding programs. Of these companies, Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding construct nuclear-powered ships and submarines. Figure 1 shows the locations of the major private shipyards that the Navy contracts with for shipbuilding.

These shipyards use a network of suppliers, known as the supplier base, to provide a range of items, from raw materials to manufactured items.

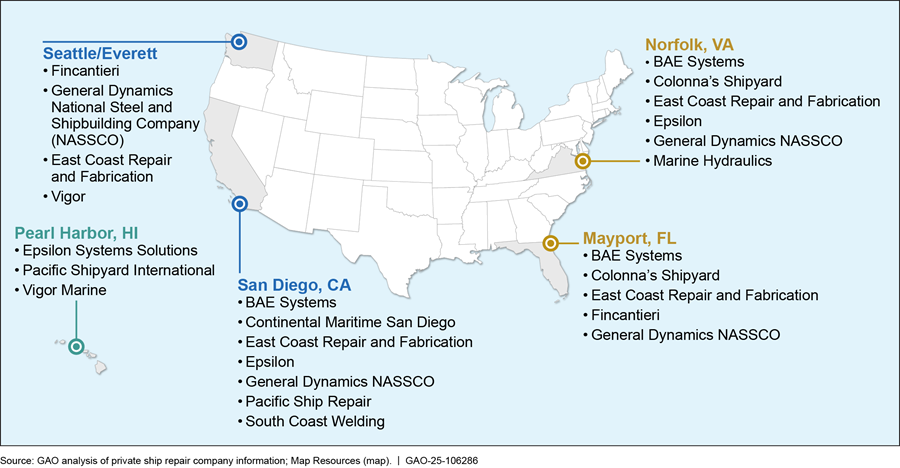

Private repair companies conduct maintenance for the nonnuclear surface fleet and comprise the industrial base for ship repair at the prime contractor level. These companies perform repair work in either government-owned or contractor-owned facilities. As of May 2024, there were 12 companies—including some that operate in multiple locations—that conduct major repair periods (also called Chief of Naval Operations availabilities) for the Navy’s amphibious ships and surface combatants. Additional companies conduct repairs for the Littoral Combat Ship. Only companies with Master Ship Repair Agreements, which are used to validate a company’s ability to conduct major repair periods, or that demonstrate equivalent capabilities, can conduct this work.[20] These repair periods accomplish significant planned repair work, such as structural, mechanical, and electrical repairs. Repair periods may include modernization work to upgrade a ship’s capabilities along with repair work, and they can last for over a year. During these repair periods, companies often take ships out of the water and put them into a dry dock to perform maintenance on below-water parts of the ship. Other types of repair periods are used to accomplish non-major repair work in shorter time periods—typically only weeks to a few months in duration.[21]

Domestic facilities where contractors repair naval surface ships are located in areas where ships are homeported, commonly referred to as fleet concentration areas. Five fleet concentration areas primarily conduct work for major repair: Mayport, Florida; Norfolk, Virginia; Pearl Harbor, Hawaii; San Diego, California; and Seattle/Everett, Washington. Figure 2 shows the companies that conduct these repairs and their locations.

Figure 2: Map of Private Ship Repair Companies Conducting Complex Navy Ship Repair Work by Fleet Concentration, Area as of May 2024

Note: The Navy uses a separate construct for ship repair

for the Littoral Combat Ship and does not designate the work as “complex” and “non-complex”.

As a result, some companies that were excluded from this figure perform repair

work for the Littoral Combat Ship. According to Navy documentation, the

following additional companies in San Diego are eligible to perform major

repair periods for the Littoral Combat Ship: Austal, Marine Group Boat Works,

and Vigor. In Mayport, Navy documentation shows that the following additional

companies can perform major repair periods for the Littoral Combat Ship:

Austal, Epsilon, and Tecnico Corporation.

Some of the contractors for major repair periods have their own facilities—such as dry docks—while other companies rely on Navy-owned facilities to conduct repair work.

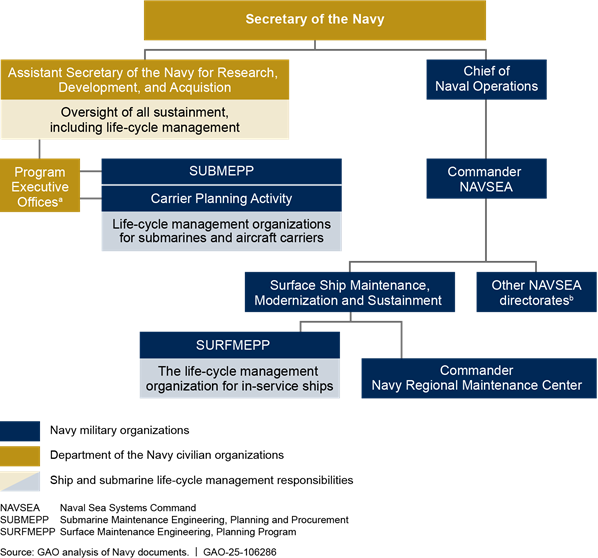

Key Navy and DOD Organizations with Responsibilities Related to Shipbuilding and Repair

Many organizations within the Navy and within DOD’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment have responsibilities related to the shipbuilding and ship repair industrial base.

· The Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition (ASN (RD&A)) has overall authority, responsibility, and accountability for all acquisition and sustainment functions and programs, including surface ship repair and maintenance.

Within the ASN (RD&A), Program Executive Offices (PEO) manage all aspects of life-cycle management of their respective programs, including program initiation, ship design, construction, testing, delivery, fleet introduction, and maintenance activities. PEO Ships manages the design and construction of all Navy nonnuclear surface ships, including surface combatants, amphibious ships, and support vessels. It is also responsible for providing complete life-cycle support for these ships. Similarly, PEO Strategic Submarines, PEO Attack Submarines, and PEO Carriers manage the design, construction, and life-cycle support for nuclear-powered submarines and aircraft carriers.

· There are eight Deputy Assistant Secretaries of the Navy (DASN) that serve in coordinating roles and advise the ASN (RD&A) on subjects related to the office’s responsibilities. The DASN for Ship Programs (DASN Ships) is the principal advisor and coordinator for the ASN (RD&A) on matters pertaining to aircraft carriers, other surface ships, and submarines. DASN Ships also monitors and advises on ship programs managed by PEO Ships, PEO Carriers, PEO Strategic Submarines, and PEO Attack Submarines. Further, it is the principal advisor to the ASN (RD&A) for the shipbuilding industrial base. DASN Sustainment is the principal advisor and coordinator for the ASN (RD&A) on matters pertaining to Navy system sustainment, including policy, infrastructure, and supply chain management.

· The Chief of Naval Operations is the senior military officer of the Department of the Navy and is responsible to the Secretary of the Navy for the command, utilization of resources, and operating efficiency of the operating forces and shore activities. The Chief of Naval Operations serves as the primary focal point for developing department-level policy for approval by ASN (RD&A) on all matters dealing with ship sustainment and life-cycle logistics. This includes ensuring resources for maintenance and supply support align with Navy objectives.

· Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) and its directorate organizations provide support to both the acquisition and sustainment communities. NAVSEA is comprised of experts across multiple disciplines responsible for ensuring ship repair meets fleet requirements within cost and schedule parameters, among other duties for combat systems design and operation. Two of these directorates have responsibilities for the industrial base through contracting and life-cycle management functions:

· NAVSEA’s Contracts Directorate awards contracts for new ship construction and ship repair through its shipbuilding and fleet support divisions, respectively.

· NAVSEA’s Directorate for Surface Ship Maintenance, Modernization and Sustainment provides life-cycle management of the Navy’s in-service surface ships and manages critical modernization and maintenance programs.

· Within the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD(A&S)), the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy manages investment programs for the defense industrial base. This office serves as DOD’s principal advisor within OUSD(A&S) for issues and investment programs affecting the industrial base across the DOD enterprise.

Ship Industrial Base Struggles to Meet Navy’s Goals for Shipbuilding and Ship Repair

The Navy shipbuilding and ship repair industrial base struggles to meet the Navy’s goals for on time completion of ship construction and ship repair periods. Further, the Navy continues to base its shipbuilding goals on assumptions about the industrial base’s ability to achieve better performance than it has historically, but which it has yet to demonstrate. In part, our analysis found that shipbuilders have insufficient or aging infrastructure and struggle to hire and retain an appropriately trained workforce, which will make such improvements to performance difficult to accomplish. Similarly, the Navy has historically not met its ship repair schedule goals, though it has achieved some improvements since 2019. While companies that repair Navy ships have enough capacity for planned work, they are not always able to accommodate surges of unplanned work.

Shipbuilding Industrial Base Has Not Historically Met the Navy’s Goals

The shipbuilding industrial base has not met Navy goals for ship production in recent history. Specifically, the Navy’s recent shipbuilding plans have consistently reflected a larger increase in the fleet than what the industrial base has been able to achieve. For example, as shown in table 1, shipbuilders often did not meet the Navy’s planned rate of ship deliveries for Virginia class submarines and Arleigh Burke class destroyers from 2019 to 2023.[22]

Table 1: Number of Navy Planned Delivery of VCS and DDG 51 Compared with Actual Delivery Rates, Fiscal Years 2019-2023

|

Fiscal year |

Navy planned quantity of VCS to be delivered |

Number of delivered VCS |

Navy planned quantity of DDG 51 to be delivered |

Number of delivered DDG 51 |

|

2019a |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

2020b |

3 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

|

2021 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

|

2022c |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

|

2023d |

1 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

|

Total |

11 |

4 |

15 |

7 |

VCS: Virginia class submarines

DDG 51: Arleigh Burke class destroyers

Source: GAO analysis of Navy documentation. | GAO‑25‑106286

a2019 Navy planned numbers from the Navy Shipbuilding Plan fiscal year 2019.

b2020 Navy planned numbers from the Navy Shipbuilding Plan fiscal year 2020. The 2021 Navy planned numbers also come from the Navy Shipbuilding Plan fiscal year 2020 because the Navy did not release future inventory goals in this year.

c2022 Navy planned numbers come from the Navy Shipbuilding Plan submitted to Congress on December 9, 2020.

d2023 Navy planned numbers from the Navy Shipbuilding Plan fiscal year 2023.

These types of delayed ship deliveries contribute to the fleet not growing at a rate commensurate with Navy plans. For example, in fiscal year 2020, the Navy planned to have a battle force of 313 ships by 2025. However, in its fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan, the Navy plans to have a fleet of 287 ships by 2025—26 fewer ships than previously planned.

The Navy’s shipbuilding plans include goals that are based on assumptions about the industrial base’s ability to achieve better performance than it has achieved in the past, and that has yet to be

demonstrated.[23] The Navy’s fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan states that the Navy developed the plan based on the assumption that private industry will eliminate excess construction backlog and produce future ships on time and within budget—an assumption not grounded in historical trends. Navy officials with responsibility for the shipbuilding plan stated that they made this assumption because they expect their investments in the shipbuilding industrial base will enable improvements. However, our prior work has shown that Navy shipbuilding has regularly fallen short of schedule and cost goals, and current performance is consistent with these trends. As such, the Navy would need to deliver more ships at a quicker rate to meet its goals.[24]

|

Secretary of the Navy’s 45-Day Shipbuilding Review The Secretary of the Navy (pictured) directed the Navy in January 2024 to complete a 45-Day Shipbuilding Review to: (1) analyze the Navy’s shipbuilding portfolio; (2) assess the national and local causes of shipbuilding challenges; and (3) provide recommended actions for achieving a healthier shipbuilding industrial base to support warfighters’ needs on a timely schedule.

The Secretary of the Navy called for the study amid reported delays in the Columbia class submarine and the Constellation class frigate programs. In early 2024, the Navy released results from its study, which included an assessment of nine shipbuilding programs, their risks, issues, and root causes. It found schedule delays ranging from 12 to 36 months for four programs and delays to contract delivery dates for four additional programs; the remaining program had yet to start construction. Contributing factors for program delays included: (1) issues with the lead ship, such as with design maturity problems in the Constellation class frigate, and (2) ship class issues that are not unique to the lead ship, such as difficulty in hiring a skilled workforce. As a result of the review, the Navy is developing five initiatives for improvement in areas of workforce, acquisition and contract strategies, and investments. Source: GAO analysis of Navy documents (text); U.S. Navy/Chief Petty Officer Shannon Renfroe (photo). | GAO‑25‑106286 |

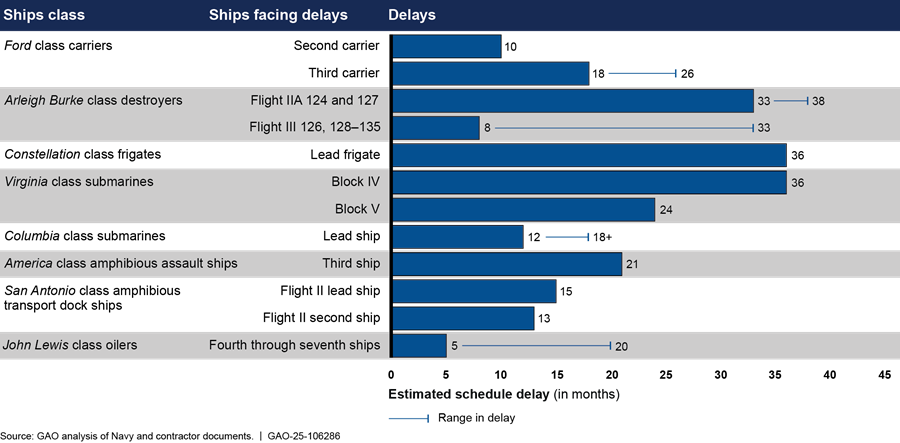

Schedule. The Navy’s 45-day review of its shipbuilding programs, completed in early 2024, states that its major shipbuilding programs continue to struggle with schedule delays (see sidebar). Our analysis found that schedule delays continue for most ships currently under construction, in addition to the number of ship delays reported in the 45-day review (see fig. 3).

Note: This analysis reflects 37 out of 45 battle force ships (85 percent) currently under construction, all of which are facing delays. GAO excluded the Littoral Combat Ship because the Navy is not planning to procure additional quantities of this class under its shipbuilding plan. GAO also excluded ships that recently started construction and for which there is not sufficient data to measure performance. We also excluded command and support ships.

Cost. Cost increases erode the Navy’s buying power to execute its shipbuilding plan, particularly because the plan assumes that ships will be delivered in alignment with cost targets. Yet we found that many shipbuilding programs face cost overruns. For example:

· Our independent analysis on the cost of the lead ship of the Columbia class submarine reflects that the government could be responsible for hundreds of millions of dollars in additional construction costs.[25]

· For the second Ford class carrier, John F. Kennedy (CVN 79), costs had increased by $1.3 billion in August 2021, largely due to contract overruns. The program has also increased costs due to programmatic changes. For example, we reported in June of 2024 that the program’s baseline construction costs increased an additional $0.2 billion because the program delayed planned delivery for CVN 79, and some post-delivery costs will now be included under the construction baseline.[26]

· On the lead ship of the Constellation class frigate and a block of six John Lewis class oilers, costs are estimated to have increased above the contracts’ ceiling prices. Costs exceeding the ceiling are generally absorbed by the contractor.[27]

These cost increases are consistent with our prior work, which found that from 2007 to 2018, cost growth in Navy shipbuilding exceeded Navy estimates by over $11 billion.[28]

Ship deliveries. Even if private industry begins delivering ships on time and within budget, the industrial base would need to deliver more ships and more quickly to meet the Navy’s current shipbuilding goals. For example, in fiscal year 2023, private industry delivered seven new battle force ships, but private industry would need to deliver an average of roughly 13 ships per year for 30 years to meet the optimal fleet size goal under the current shipbuilding plan.

This increase would be needed because the Navy now targets a larger fleet size than it did in prior years and because it also plans to continue to decommission many ships during the same period. Specifically, the Navy plans to grow the size of the fleet by 91 ships over the next 30 years, yet it plans to decommission 292 ships during the same period.[29] As a result, the Navy will need to deliver a total of 383 ships in 30 years to reach its goal. However, the industrial base has yet to demonstrate an ability to increase production in this manner. The Navy’s fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan states that it would rely on planned, but not yet achieved, industrial capacity to do so.

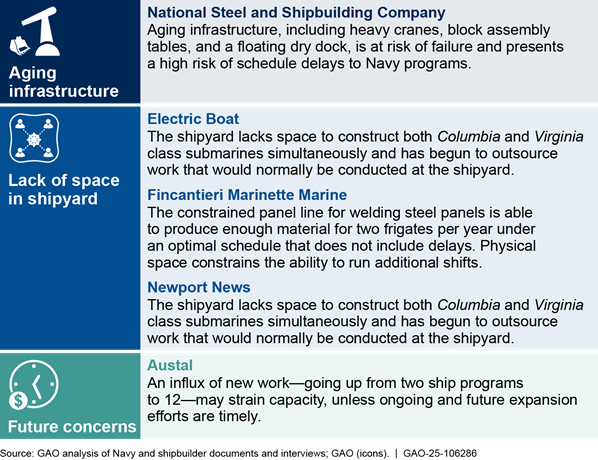

Industrial Base Infrastructure and Workforce Limitations Make Shipbuilding Delays Difficult to Overcome

Our analysis of Navy and shipbuilder documentation—as well as discussions with the seven shipbuilders that construct the Navy’s battle force ships—shows that none of the shipbuilders are currently positioned to meet the Navy’s delivery goals. This is, in part, due to infrastructure and workforce limitations.

Shipbuilding Infrastructure Limitations

The Navy’s current shipbuilders are limited in their ability to produce ships on time and within budget in part because of their existing infrastructure, which includes the amount of physical space and aging facilities.

Limited physical space. While representatives from three shipbuilders told us they have room to expand as needed, representatives from four of the shipbuilders stated they have constrained physical space. Specifically:

· Two of the shipbuilders we spoke with are already outsourcing work that would normally be done at their shipyards to their suppliers to overcome constrained physical space, with plans to expand the volume of material they are outsourcing.

· One shipbuilder has plans to use outsourcing but has yet to decide what portions of the construction effort to offload to the supplier base.

· One shipbuilder is considering outsourcing in the future if it is awarded a contract to construct a new class of Navy ships.

While outsourcing to suppliers can alleviate physical constraints at shipyards, many suppliers also have their own workforce and infrastructure problems that could result in challenges to their ability to produce quality materials on time. Additionally, as we previously reported, quality assurance oversight at supplier facilities is critical for avoiding further delays that could result from quality problems.[30]

Aging infrastructure. Some of the shipbuilders we spoke with also face challenges related to aging facilities and equipment that affect their ability to produce ships on schedule. Additionally, Navy officials stated that one shipbuilder experienced failures in its aging infrastructure that caused schedule delays and cost increases. Moreover, Navy documentation states that this shipbuilder has additional aged infrastructure that presents similar risk for schedule delays and cost increases.

Barriers to increasing capacity. Several of the seven shipbuilders the Navy currently relies on to build its battle force ships have specialized production capabilities that constrain the types of vessels they can build. This also presents a barrier to additional companies that may want to enter the market space in the future. This is, in part, because existing shipbuilders have optimized their facilities—by purchasing specialized tools and equipment—and developed specific processes to build specific ship types. Additionally, to start building Navy ships, new companies would also need expensive facilities and tooling that could present a barrier to market entry or result in duplicative costs to the government.

The Navy has some potential options for using additional U.S. shipbuilders to construct its battle force ships. For example, representatives from a shipbuilder we visited that generally constructs Coast Guard ships and conducts other commercial work told us that they would be interested in pursuing contracts for larger Navy ships. Other U.S. shipbuilders that construct ships for the U.S. Coast Guard, Military Sealift Command, and commercial buyers could also potentially pursue Navy work. However, the number of additional domestic shipbuilders is limited. Though the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have reflected that the commercial shipbuilding industry could build some Navy ships, such as auxiliary and support ships, these plans also note that U.S. commercial shipbuilding has atrophied. Specifically, the fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan states that U.S. commercial shipbuilding has experienced a near-total collapse and calls for the long-term revitalization of the domestic shipbuilding industry to bolster Navy shipbuilding and enable better cost and schedule outcomes.[31]

Shipbuilding Workforce Limitations

The Navy’s ability to reach shipbuilding goals is also limited by the size and composition of the shipbuilders’ workforces. We found that all seven shipbuilders face workforce limitations—such as problems with recruitment, retention, or skill level—that affect their ability to meet the Navy’s new ship delivery goals.[32] Further, when accounting for attrition, a DOD briefing from the 45-day shipbuilding review shows that over the next decade, the shipbuilding industrial base will require 174,000 new workers to keep pace with Navy shipbuilding goals. All seven of the shipbuilders we interviewed stated that they faced challenges with their skilled workforce. The following examples highlight key elements of the shipbuilders’ workforce challenges that we identified through reviewing documentation and interviews:

Demographic shift. The skilled workforce in the U.S.—such as for welding and electrical work—is aging and retiring, and fewer new workers are learning these skills to replace retiring workers. This demographic shift makes positions for skilled work more difficult to fill. For example, representatives from a shipbuilder told us that a generational shift away from work in manufacturing affected their hiring. DOD’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation’s review of the submarine industrial base for fiscal year 2023 states that a generational shift away from manufacturing careers has led to workforce shortages in key skilled labor positions.[33] Further, a 2021 DOD report on the defense industrial base workforce identified a national shortage in skilled labor that DOD must address to ensure enough workers for defense programs, such as in shipbuilding.

|

Limited Workforce and Infrastructure Capacity of the Submarine Shipbuilders As we previously reported, demand for submarine production has exceeded infrastructure and workforce capacity of both Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding, the only shipbuilders that produce nuclear powered submarines. The Navy, however, has a goal of increasing the rate of production. It plans to begin serial production—to start producing one Columbia class submarine per year—in fiscal year 2026. At the same time, it plans to continue its goal of producing two Virginia class submarines per year (together, the rate of submarine production is commonly referred to as “1+2”). Additionally, the size of submarines being produced has also increased. The Columbia class submarine is the largest submarine the U.S. has ever built. Further, Block V Virginia class submarines are larger than the earlier Block IV design due to additions, such as the Virginia Payload Module (a new section of the submarine that increases its capacity for cruise missiles). The Department of Defense (DOD) estimates that, based on the size increase from both submarine classes and the volume of materials needed, the shipbuilders will need to begin producing the equivalent of five Block IV Virginia class submarines per year starting in fiscal year 2026. According to a DOD assessment, the shipbuilders’ inability to keep up with planned submarine procurement rates undermines confidence in their ability to keep pace with a “1+2” rate of production. Further, current strains on shipyard capacity do not include increased demand for Virginia class submarines that may result from the need to replace submarines that would be sold to Australia under the Australia, United Kingdom, and United States Trilateral Security Partnership (AUKUS). Source: GAO analysis of Navy information. | GAO‑25‑106286 |

Recruitment and retention challenges. All seven of the shipbuilders we spoke with told us that competition with other industries for workers resulted in recruitment and retention challenges. Representatives from these companies provided examples of the services industry (such as fast-food companies and freelance work like Uber); technology companies; and the paper, oil and gas, and construction industries as being among their competitors. Five of the seven shipbuilders noted that a shrinking gap between wages for the services industry and manufacturing jobs, like shipbuilding, was a driver of this challenge. One shipbuilder explained that this is because people can make similar wages in the services industry and may perceive the work to be easier than working in a shipyard. Three shipbuilders told us that they recently raised wages to be more competitive for skilled workers.[34]

Inexperienced staff. The majority of shipbuilders we spoke with need to hire thousands of skilled employees in the coming years, which will increase the number of inexperienced staff. For some of the shipbuilders, these hiring efforts, if successful, will result in an increase in the size of their skilled workforce by roughly 80 to 100 percent, but will result in a smaller proportion of experienced skilled employees. According to shipbuilder documentation, it takes between 3 and 5 years for an employee to gain proficiency in the skilled trades. A shipbuilder we spoke with noted that they already have a high percentage of trade workers with fewer than 5 years of experience—at 57 percent. We previously found that the majority of skilled workers at another shipbuilder were expected to have less than 5 years of experience.[35] We reported in 2024 that this shipbuilder continued to struggle with an inexperienced workforce.[36] This will likely result in reduced shipyard efficiency in the near term. New employees also require greater supervision to avoid quality problems with resulting effects on cost and schedule. This could help avoid, for example, the types of quality problems and late discovery of rework that have affected the schedule of the lead Columbia class submarine. Yet, many shipbuilders will be challenged to provide the supervision needed because of the increasing proportion of newer employees.

Further, infrastructure and workforce limitations have been particularly acute in submarine shipbuilding. As a result, submarine shipbuilders are behind schedule and currently do not have the capacity to produce a greater rate of submarines per year, despite the Navy’s plans to do so in the future (see sidebar on previous page).

Appendix III provides examples of specific infrastructure challenges from shipbuilders we met with during our review and from our review of Navy documentation.

Ship Repair Industrial Base Has Not Met Schedule Goals Though It Has Seen Some Recent Improvements

The private ship repair industrial base has not met the Navy’s schedule goals for completing repair periods, although there have been some recent improvements. According to the Navy’s maintenance plan, in fiscal year 2022, repair companies completed only 36 percent of nonnuclear-powered surface ship repair periods on time. Further, in January 2024, we reported that private ship repair companies took nearly 10,000 days longer than planned to repair destroyers and more than 5,500 days longer than planned on cruisers between fiscal years 2015 and 2022.[37] Such maintenance delays reduce the number of ships available for training and operations. We also reported that the Navy has struggled to complete surface ship maintenance periods in full—meaning that the Navy did not complete all required maintenance scheduled or canceled the maintenance period entirely—resulting in a $2.3 billion backlog of surface ship maintenance by August 2022.[38]

Although the Navy still faces maintenance timeliness challenges, we found the average days of maintenance delay trended down from fiscal years 2019 through 2022.[39] Similarly, a 2023 Navy report stated that days of maintenance delay on complex repair periods had decreased by 43 percent since fiscal year 2019. The private sector industrial base for ship repair has also expanded in recent years, leading to more capacity for Navy repair work. For example, Austal invested in a dry dock for San Diego in 2021, representatives from Fincantieri told us in 2023 they invested in a dry dock for Mayport, and BAE Systems documentation shows that the company has invested in adding a docking system in the Mayport area that will operate similarly to a dry dock, with plans to be certified by April 2025.

The Navy attributes some of these improvements to a change it made to its contracting strategy in 2015, which it stated has increased competition in the ship repair industrial base.[40] Unlike in shipbuilding, in ship repair, there are often enough companies with capacity that there may be multiple companies able to compete for repair periods. According to Navy documentation, increased opportunities for competition since the Navy changed its contracting strategy has provided more opportunities for businesses to enter the Navy ship repair market and resulted in an expansion of the industrial base. For example, while under the prior contracting strategy there was only one company performing major Navy repairs in Mayport and one in Pearl Harbor, there are now five companies that can compete to be awarded orders to perform this work in Mayport and three in Pearl Harbor. However, when the Navy does not anticipate multiple companies will compete for a repair period within a fleet concentration area, it can also expand competition along the East or West Coast to consider additional companies.[41]

Ship Repair Industrial Base Has Capacity but Cannot Always Surge to Accomplish Unplanned Work

The ship repair private sector industrial base generally has enough capacity to support the Navy’s planned surface ship repair work in the near term. However, this industrial base does not always have the capacity to support maintenance plan changes, such as growth work, emergency repairs, or wartime needs due to limited infrastructure and workforce capacity.

Ship Repair Infrastructure Capacity

Our analyses found that the industrial base for ship repair has sufficient infrastructure capacity through at least fiscal year 2026 in each of the five fleet concentration areas—including private industry dry docks and dry docks at Navy facilities used by private industry for surface ship repairs—for the Navy’s peacetime planned surface ship maintenance.[42]

Representatives from companies in every fleet concentration area told us that they often had more infrastructure capacity than the Navy was using, except Pearl Harbor, where only Navy owned facilities are in use for ship repair.[43] For example,

· Mayport, Florida. One company we interviewed that conducts repair for the Mayport fleet concentration area has an ongoing acquisition to expand its docking capacity. Representatives from the company stated that the Navy could potentially use this additional capacity for surge capacity when needed if the Navy decided to pay for unused space. However, company representatives stated that they also have opportunities for commercial and Coast Guard repair work, so the facility could be otherwise filled with other work. We also spoke with a second company that is adding dry dock capacity in Mayport. Additionally, complex repairs are performed at Navy facilities in Mayport, which provide further infrastructure capacity for repairs.

· Norfolk, Virginia. We spoke with three companies that own dry docks in Norfolk, and representatives from all these companies told us there was unused dry dock capacity in the region. Representatives from one company told us that their dry docks were in use 53 percent of the time in 2022. Representatives from another company told us that their dry dock was in use roughly 85 percent of the time, but that this figure included their commercial repair work in addition to Navy work.

· San Diego, California. Representatives from one company with a dry dock in San Diego told us that their dry dock was in use roughly 70 percent of the time during the past 5 years. Representatives from another company told us they have enough dry dock space to accommodate two Navy ships up to a certain size simultaneously. However, these representatives told us that they did not regularly have two ships docked in this space. Further, they stated that their dry dock was in use 75 percent of the time in 2022. We also spoke with a company that is in the process of adding dry dock capacity in San Diego. In addition to dry dock capacity provided by private industry, companies can perform complex repair work at Navy facilities in San Diego.

· Seattle/Everett, Washington. Representatives from one company that owns a dry dock in Seattle told us that they had more capacity to do Navy work. In addition to their dry dock and pier capacity in Seattle, these representatives also told us this company had dry dock capacity in Portland, Oregon where it could also conduct repair for the Navy.

While some repair companies told us they had additional capacity to provide to the Navy, the amount of usable private industry dry dock capacity available to the Navy is dependent on a variety of factors. For example:

· Companies may have repair work from other sources, such as the Coast Guard or commercial industry, that could occupy their dry docks;

· The Navy needs dry docks of specific sizes to accommodate different classes of ships, so the infrastructure available would need to match the Navy’s needs to be usable;[44] and

· The amount of planned Navy repair work is variable, with some periods of time requiring more dry docks than others. As a result, there are times when none of the private industry dry docks the Navy relies on within a homeport are available.

Moreover, when the Navy needs private industry dry docks for unplanned work, it can disrupt the schedule for repair work the Navy had already planned.

We found, however, that there is not always sufficient infrastructure capacity available to manage unplanned repair work, such as growth work or emergent repairs. Growth work refers to additional tasks identified during performance that is related to a work item already specified on the original contract, some of which may be identified after a repair period has begun. For example:

· Growth work. Given the nature of ship repair, the Navy and ship repair companies will sometimes identify growth work during a maintenance period that was not originally planned. As an example, a Navy official stated that they cannot fully inspect ballast tanks and accurately write work specifications for their repair until the repair period has begun. In the Navy’s November 2023 report on its repair contracting strategy, the Navy identified growth work as a significant driver of maintenance delays. Yet, this report states that the Navy cannot rely on companies to accomplish large amounts of unplanned work added to a contract.[45] In part, this is because large amounts of unplanned work require planning, negotiation, and execution of time-consuming contract changes. Growth work can also result in the use of infrastructure, like dry docks, for longer than planned, which can disrupt the ability to start new repair periods. We have reported that growth work has detracted from both cost and schedule performance, and according to Navy documentation, this trend continues.[46] The Navy’s fiscal year 2025 maintenance plan states that the Navy has ongoing efforts to reduce growth work so that it can complete more repair periods on time.

|

Recent Example of Emergent Repair In June 2017, the USS Fitzgerald collided with a merchant vessel off the coast of Japan. Navy tugboats towed the ship to Fleet Activities Yokosuka, Japan, where it received temporary repairs. Later, the transport vessel Transshelf moved the ship to Ingalls Shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi, where it received the remainder of its repairs. Like battle damage repairs, these types of repairs have to be absorbed by the industrial base. In this way, emergent repairs such as those in response to the USS Fitzgerald collision in 2017 more closely mirror a battle damage repair process. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106286 |

· Emergent repairs. This type of repair occurs during ship deployments when ships experience a malfunction or other issue requiring immediate repairs (see sidebar).[47] The Commander of the Pacific Fleet issued a memorandum in August 2023 on the need for an additional dry dock in Pearl Harbor based in part on a need for these types of repairs. The memorandum states that there is no capacity for emergent repair work at this location for half of the time through at least 2028, which the Commander of the Pacific Fleet assessed as a high-risk circumstance. Our prior work has also shown that the Navy needs additional capacity for wartime repair, as the Navy has not had to conduct battle damage repair on multiple ships concurrently since World War II.[48]

In some instances, the Navy can shift the timing or location of other repair work to areas with additional capacity to mitigate infrastructure capacity challenges resulting from unplanned work. The Navy also plans to increase dry dock capacity for emergent and potential wartime repairs by encouraging private industry to build additional infrastructure and by building infrastructure at Navy facilities used for surface ship repairs done by private industry (see table 2).

Table 2: Navy Projection for Adding Surface Ship Dry Dock Capacity by Fleet Concentration Area, as of 2024

|

Fleet concentration area |

Navy plans for adding government and privately owned capacity |

Navy rationale for seeking additional capacity |

|

Mayport, Florida |

None |

Not applicable |

|

Norfolk, Virginia |

Navy officials told GAO that they are evaluating whether to seek investment by private industry in an additional dry dock, with a decision expected to occur later in the 2020s. |

Not applicable |

|

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii |

The Navy plans to begin using a dry dock that is currently dedicated to surface ship repair for submarine repair. As a result, the Navy identified a need to purchase a floating dry dock for Pearl Harbor for surface ship repair, with a need for it to be operational no later than fiscal year 2035. It is currently in the planning stage for this acquisition. |

Replace current dry dock capacity for planned ship repairs. |

|

San Diego, California |

The Navy has an ongoing acquisition of a floating dry dock. |

Provide surge capacity for planned and emergent maintenance. |

|

Seattle/Everett, Washington |

The Navy reported leasing a floating dry dock to a private ship repair company. This dock is currently located at the contractor’s facility in Seattle. According to Navy officials, when the lease ends in fiscal year 2025, the Navy is planning to renew it for another 5 years. However, the Navy put out a request for information from private industry to explore additional options for use of the dry dock. The Navy is also evaluating a permanent move of this dock to Naval Station Everett when the renewed lease expires, now planned for fiscal year 2030, as an alternative solution. |

Provide surge capacity for wartime and emergent maintenance; improve competition by providing a dry dock to companies to complete repair work. |

Source: GAO analysis of Navy documentation. | GAO‑25‑106286

Ship Repair Workforce Capacity

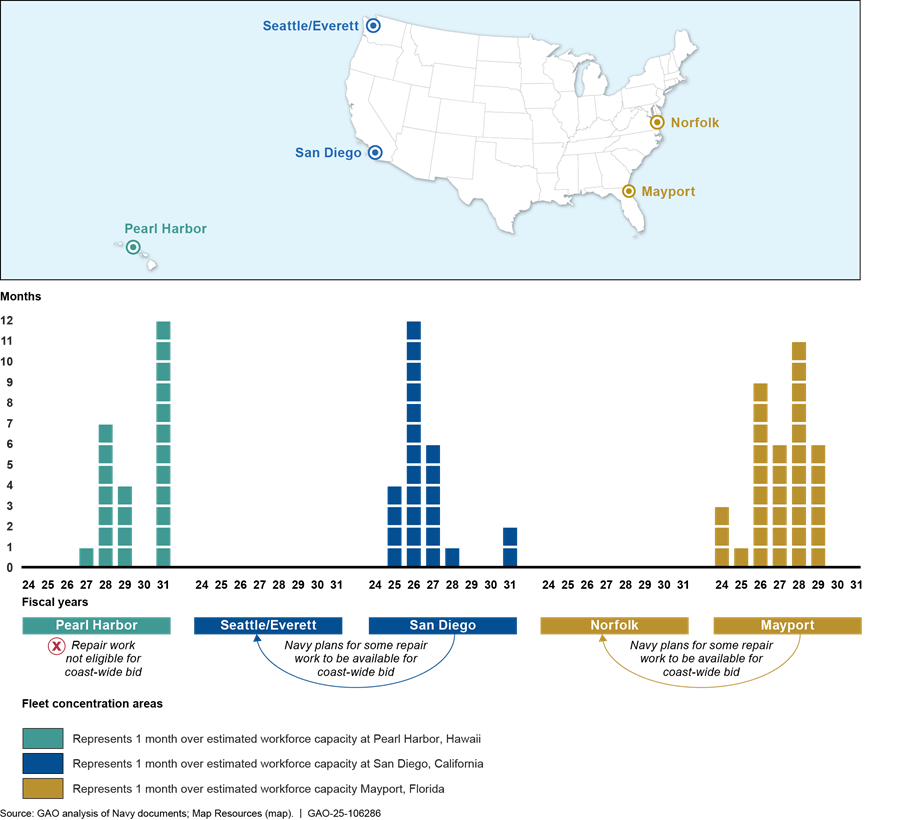

The Navy estimates that its planned repair workload could exceed ship repair companies’ workforce capacity in three fleet concentration areas— San Diego, Mayport, and Pearl Harbor— at some times through fiscal year 2031 if workforce capacity does not change from current levels.[49] However, it often has some flexibility to shift the timing of work or location to areas with additional capacity.[50]

In most instances when the Navy anticipates a volume of work that exceeds workforce capacity, it plans to expand the geographic range for competition for repair periods during this timeframe so that it can utilize repair workforce that is available elsewhere (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Navy Estimation of When Workload Could Exceed Capacity Based on Private Repair Companies’ Workforce Levels, as of February 2024

Navy officials told us that they are concerned with repair projections that exceed current workforce capacity in San Diego because of instability in the projected repair workload. Navy officials told us they are less concerned about the projected workload in Mayport and Pearl Harbor because the surges in workload are projected to occur in later years, giving both the Navy and the industrial base more time to prepare. The Navy’s plans for addressing periods when projected workload exceeds estimated capacity in San Diego, California; Mayport, Florida; and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii; are as follows:

San Diego, California. Navy documentation shows the workload in San Diego faces a dip in the second quarter of fiscal year 2025 that immediately precedes a spike. Navy officials stated that this instability could result in a reduction of the amount of available workforce as repair companies may reduce the size of their workforce when the workload is projected to dip. Navy officials told us that this issue would be a subject of discussion during future planning sessions to schedule repairs. To mitigate any workforce limitations in San Diego, the Navy is able to award repair work to ship repair companies in Seattle/Everett, Washington, as appropriate. Representatives from one of the repair companies we spoke with in Seattle told us that they did not have challenges with hiring enough workers when they have enough lead time.

Mayport, Florida. Representatives from one ship repair company told us that their ongoing effort to add infrastructure capacity to repair more ships will allow them to employ hundreds of additional full-time employees in the future. If they are successful in hiring as expected, it would help reduce any repair workforce shortages in the region. Additionally, the Navy is able to award work to ship repair companies in Norfolk, Virginia, as appropriate. Representatives from five of the six ship repair companies in Norfolk that we spoke to told us that they had either conducted layoffs or were concerned about having to reduce the size of their workforce because of a downturn in Navy repair work. However, the Navy projects that Norfolk will have either excess workforce capacity or the ability to provide surge capacity through overtime through at least fiscal year 2031.

|

Examples of Regional Challenges for Navy Ship Repair in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii Navy officials told GAO that Pearl Harbor, Hawaii faces some unique challenges in ship repair due to its location, such as: Frequency of emergent repair demands. Navy officials told GAO that because of its strategic location, Pearl Harbor conducts a high number of emergent repair periods. For example, ships deploying from San Diego, California and Seattle/Everett, Washington or returning from Japan may need to stop at Pearl Harbor for emergent repairs. Officials stated that if ships with operational commitments come with high priority repair needs, they may delay planned maintenance to address the needs of these ships. Availability of local workforce. Navy officials from the regional maintenance center told GAO that ship repair workforce recruitment is generally limited to people who already live on the island. They stated that people who come to Pearl Harbor to conduct Navy repairs are generally only willing to stay about 5 years. Suppliers and technical support for repairs. Navy officials told GAO that supplies and technical support for repairs take longer to get to Pearl Harbor because of transit time. For example, when technical support for ship repair is needed from original equipment manufacturers, it can be difficult to obtain quickly because representatives need to fly into Hawaii from the contiguous United States. Source: GAO analysis of Navy information. | GAO‑25‑106286 |

Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Representatives from one of the repair companies we spoke with in Pearl Harbor also stated that they can take on additional work if the Navy provides them with enough lead time for them to prepare. Similarly, Navy officials from the regional maintenance center in Hawaii told us that private industry could gradually increase the number of workers available if it has stable work. However, based on the Navy’s projected volume of work for fiscal year 2031, private industry would need to be prepared for roughly double the amount of work that it can presently accomplish. Increasing the workforce in Hawaii could be particularly challenging (see sidebar). According to a Navy report on ship maintenance gaps and requirements from November 2021, Navy personnel may be used to conduct repairs that exceed private industry’s workforce capacity.

During some periods, the Navy projects that the amount of work in every fleet concentration area will go up above normal workforce labor hours but remain below estimated port capacity. Many ship repair companies told us that they use subcontracted labor to bolster their workforces and can create capacity as needed. Yet, Navy documentation states that managing sustained surges in this way for prolonged periods can affect the cost, schedule, and quality of maintenance periods. Unplanned work—like emergent repair needs—could result in prolonged periods in which a surge in workforce is needed. This is because, as emergent repairs are conducted with little or no notice to restore mission-essential capabilities to ships, they may occur at times that overlap with surges of planned work.

DOD Has Yet to Fully Determine Effectiveness of or Ensure Visibility into Billions Spent on the Ship Industrial Base

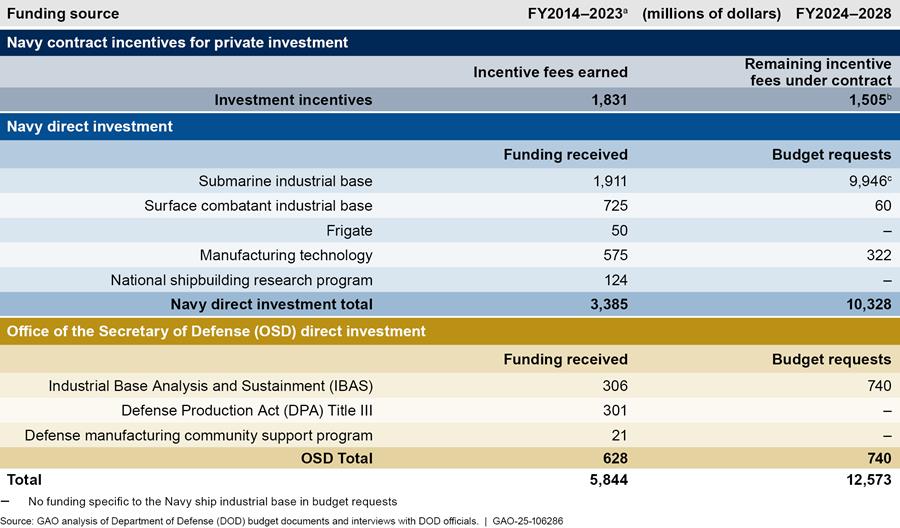

DOD has spent over $5.8 billion since fiscal year 2014 on support for the shipbuilding industrial base and plans to spend $12.6 billion more through at least fiscal year 2028. However, it has yet to fully determine the effectiveness of these funds or ensure visibility into how they are spent. The Navy has historically provided most of the funding intended to bolster the shipbuilding industrial base, but OSD also makes investments. The Navy does not consistently track its investments, and neither the Navy nor OSD has fully assessed the effectiveness of their support. Additionally, DOD has not ensured visibility into these funds because the Navy and OSD do not coordinate spending across all of their investment efforts to prevent duplication and overlap of spending. For ship repair, the Navy plans to award grants to the private ship repair industrial base for infrastructure investments, but has yet to determine the full amount of additional infrastructure it needs to meet repair goals.

DOD Has Spent Billions to Bolster the Shipbuilding Industrial Base Over the Last Decade and Plans to Spend Billions More Through 2028

DOD spent over $5.8 billion from fiscal year 2014 to fiscal year 2023 to support the shipbuilding industrial base, with plans to spend an additional $12.6 billion through fiscal year 2028.[51] This support includes:

· Navy contract incentives for private investment, which are typically used to encourage the shipbuilders to make corporate investments in infrastructure and facilities; and

· Navy and OSD direct investments, in which the government pays outright for the partial or whole cost of an investment, such as for infrastructure, workforce initiatives, and supplier development.

Figure 5 shows past and planned contract investment incentives and direct investments from the Navy and OSD for the shipbuilding industrial base.

Figure 5: Contract Incentives for Private Investment and Direct Investments for the Shipbuilding Industrial Base, Fiscal Years (FY) 2014-2028

Note: The dollar values in this figure do not account for inflation.

aGAO reviewed investments from fiscal years 2014 to 2023 and did not include fiscal year 2024 as it was still ongoing during the time of its review. The data are current as of the end of fiscal year 2023.

bThe fiscal year 2024 to 2028 includes $1,505 million in Navy investment incentives, which may be subject to change as shipbuilders may not earn all available incentives. The Navy may also add additional investment incentives for shipbuilders to earn on future contracts.

cThe fiscal year 2024 to 2028 $9,946 million

funding request for the submarine industrial base includes $2,456 million of

supplemental funding that Congress provided in April 2024. Pub. L. No. 118-50

(2024).

Appendix IV provides more information on the legal authorities associated with these investments.

|

Purpose of Navy Contract Incentives for Private Investment The Navy provides investment incentives to motivate contractor performance in areas deemed important to a shipbuilding program’s success. For shipyard investment incentives, the Navy primarily uses Special Capital Expenditures and Construction Readiness Incentives. As GAO previously reported, funds under these incentives are available to the shipbuilder only if it agrees to make a Navy-approved shipyard investment. Navy officials told us that they also consider the shipbuilder’s level of independent investment in its own facilities prior to making an incentive award. GAO previously reported that Navy officials cited a lack of competition and instability in Navy shipbuilding work as major reasons for why investments need to be incentivized. As such, investment incentives serve as a way for the Navy to help ensure shipbuilders make necessary facility and capital investments. Source: GAO‑10‑686 and GAO analysis of Navy documentation. | GAO‑25‑106286 |

Navy contract incentives for private investment. Private shipyards earned $1.83 billion in contract incentives between fiscal years 2014 and 2023. Most of this amount was shipyard investment incentives, which support capital and facility investments.[52] However, the amount also includes other contract incentive types, such as for shipbuilders to make shipyard investments to help them meet construction schedules.[53] More specifically, Navy documentation shows that:

· Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding earned about $1.15 billion in incentives under submarine construction contracts.

· Newport News Shipbuilding earned an additional $115 million under aircraft carrier contracts.[54]

· Bath Iron Works and Ingalls collectively earned $391 million under destroyer construction contracts.

· Ingalls earned an additional $67 million under amphibious ship construction contracts.

· General Dynamics National Steel and Shipbuilding Company earned about $105 million under contracts for constructing combat logistics force and command and support ships.

Navy direct investment. The Navy made direct investments of $3.39 billion between fiscal years 2014 and 2023 through various mechanisms including supplier development funding, industrial base support for the Navy’s frigate program, and research and development (see table 3).

|

Navy direct investment category |

Description |

|

Submarine Industrial Base |

The Navy uses supplier development funding for the submarine industrial base—a subset of overall Submarine Industrial Base funding—to reduce risk from existing sources and establish new sources of supply for submarine programs. The Navy and submarine shipbuilders also use it to purchase materials to help coordinate the demand signal for shipbuilding such as through multi-program material procurement, which buys materials for both programs—Virginia class and Columbia class—in one order.a |

|

Surface Combatant Industrial Base |

For the surface combatant industrial base, shipbuilders use supplier development funding to increase supplier capacity, add additional sources of supply, provide workforce development, and stabilize suppliers. The Navy also uses surface combatant industrial base funding for shipyard infrastructure and advance procurement of program materials to support the supplier base. |

|

Frigate |

The frigate shipbuilder uses frigate funding for workforce development initiatives, shipyard infrastructure, and supplier projects. |

|

Manufacturing Technology |

Manufacturing Technology provides manufacturing technologies, like artificial intelligence, to naval suppliers and focuses on affordability improvements for shipbuilding programs. |

|

National Shipbuilding Research Program |

The National Shipbuilding Research Program works to reduce costs and accelerate delivery schedules through improved shipbuilding methods, like 3D printing of metal parts. It is an industry-led effort that works with the Navy to contribute funds to projects as part of its commitment. |

Source: GAO interviews with shipbuilders and analysis of Department of Defense information. | GAO‑25‑106286

aThe Navy uses supplier development funding to coordinate the demand signal for suppliers and mitigate long-lead times for materials through multi-program material procurement, production backup units, and continuous production of shipyard-manufactured items. These program-level funding mechanisms accelerate planned program funding rather than provide additional funding. Production backup units are long-lead time materials procured early and kept in reserve to ensure their availability, and continuous production seeks to avoid challenges caused by suppliers by gaps in demand and secure potential cost savings.

OSD direct investment. OSD invested $628 million between fiscal years 2014 and 2023 in the shipbuilding industrial base. It made these investments primarily through the Industrial Base Analysis and Sustainment (IBAS) program and Defense Production Act (DPA) Title III funding, and provided a smaller amount of funding via the Defense Manufacturing Community Support Program (see table 4).

Table 4: Descriptions of Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) Direct Investment Categories for the Shipbuilding Industrial Base

|

OSD direct investment category |

Description |

|

Industrial Base Analysis and Sustainment (IBAS) |

IBAS seeks to maintain or improve the health of essential parts of the defense industry by addressing critical capability needs, such as by supporting technical education for skills needed in the industrial base. |

|

Defense Production Act (DPA) Title III |

DPA Title III focuses on projects that establish, expand, maintain, or restore domestic production capacity for critical components and technologies, such as by supporting an infrastructure project to add steel shipbuilding capacity to a shipyard. |

|

Defense Manufacturing Community Support Program |

The Defense Manufacturing Community Support Program supports long-term community investments that seek to strengthen the defense industrial ecosystem, including the submarine and shipbuilding workforce. |

Source: Department of Defense Information. | GAO‑25‑106286

|

Fiscal Year 2024 National Security Supplemental Funding for the Submarine Industrial Base Congress provided $2.456 billion in supplemental funding in fiscal year 2024 for the private submarine industrial base. Around $2.449 billion is to support the private submarine industrial base and $7 million is for Navy research, development, test, and evaluation. As part of industrial base supplemental funding Congress provided an additional $558 million for the Navy’s four public shipyards that repair submarines and $282 million for military construction. Department of Defense officials told GAO that the supplemental funding accelerates its planned funding requests by a year, so the funding for fiscal years 2025 to 2029 shifted up to fiscal years 2024 to 2028. The officials said they will need to identify a new funding amount for fiscal year 2029. See Pub. L. No. 118-50 (2024). Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense and analysis of budget documentation. | GAO‑25‑106286 |

In addition to the IBAS and DPA Title III investments for the shipbuilding industrial base, over $4.3 billion of IBAS and DPA Title III funding went to other investments in the defense industrial base, some of which indirectly benefited the shipbuilding industrial base. For example, OSD spent $38.6 million on IBAS workforce programs it categorizes as having an indirect benefit on the shipbuilding industrial base. Project MFG is an example of an IBAS workforce program with an indirect benefit, as it holds competitions for the trades nationally and internationally to promote manufacturing skills across industries.

Future planned spending. DOD plans to increase investments in the shipbuilding industrial base by an additional $12.57 billion over the next 5 years. It has requested funding in the President’s Budget for fiscal year 2025 for the submarine industrial base, surface combatant industrial base, Manufacturing Technology, and IBAS.[55] Private shipyards also have remaining investment incentives to earn on existing contracts, and the Navy can include additional incentives on future shipbuilding contracts. For example, based on recent legislation, certain future shipbuilding contracts should generally include incentives for private shipyards to implement workforce development projects.[56]

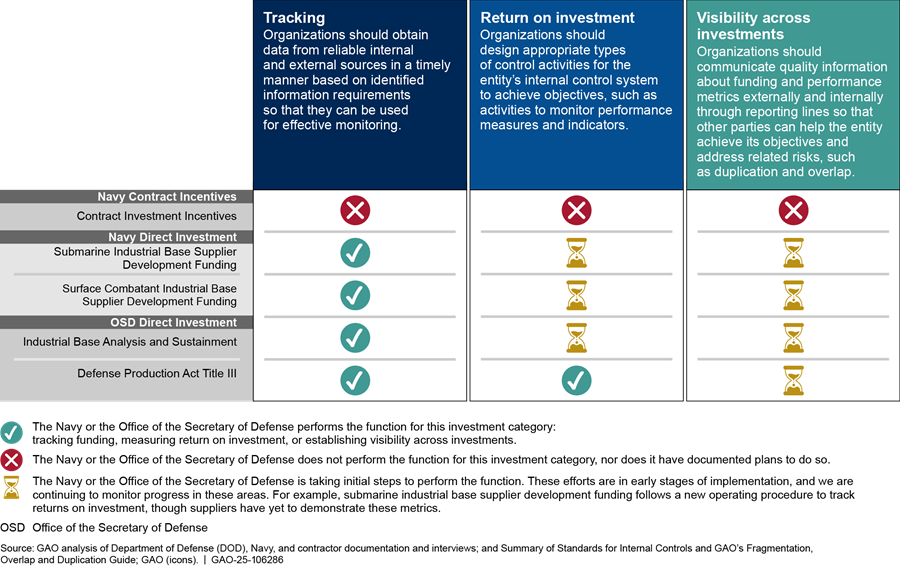

DOD Has Yet to Fully Assess the Effectiveness of Support for the Shipbuilding Industrial Base

DOD is not consistently tracking, monitoring, or fully assessing the effectiveness of the contract investment incentives and direct investment it provides to support shipbuilders and suppliers. While both the Navy and OSD take steps to assess the effectiveness of some of their funding efforts, the Navy does not track all its investments and both the Navy and OSD have yet to fully measure return on investment.[57] Further, both the Navy and OSD do not have visibility across their shipbuilding investments to help ensure against potential duplication and overlap. For example, as shown in figure 6, the Navy is not consistently

· updating the information collected on its contract investment incentives;

· conducting assessments of the effectiveness of its investment incentives; or