H-2A VISA PROGRAM

Agencies Should Take Additional Steps to Improve Oversight and Enforcement

Report to the Chair, Committee

on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

November 2024

GAO-25-106389

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106389. For more information, contact Thomas Costa at (202) 512-4769 or CostaT@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106389, a report to the Chair of the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

November 2024

H-2A Visa Program

Agencies Should Take Additional Steps to Improve Oversight and Enforcement

Why GAO Did This Study

Hundreds of thousands of foreign nationals receive permission to work in the U.S. each year under the H-2A visa program. DOL, DHS, and State each have a role in administering the program. DOL has primary responsibility for enforcing compliance with H-2A laws and regulations.

GAO was asked to review program trends and agencies’ ability to administer and enforce the H-2A visa program. This report examines, among other things, (1) trends in the characteristics of H-2A employers, jobs, and workers; (2) the extent to which DOL, DHS, and State have taken steps to process applications in a timely manner; and (3) the extent to which DOL has taken steps to investigate and remedy employer violations.

GAO analyzed DOL, DHS, and State data for FYs 2018–2023; reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and agency documents; and interviewed agency officials, five organizations representing workers, and six organizations representing employers.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that (1) DHS establish a schedule to process H-2A petitions electronically and (2) DOL evaluate options it could use to better locate workers to return back wages. DHS and DOL agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The H-2A visa program was created to allow U.S. agricultural employers to fill jobs on a temporary basis provided that workers in the U.S. are not available for those jobs. From fiscal year (FY) 2018 through FY 2023, the number of approved H-2A jobs and visas increased by over 50 percent, with the Department of State issuing almost 310,000 H-2A visas in FY 2023. The vast majority of approved H-2A jobs (87 percent) were in the farmworkers and laborers, crop, nursery, and greenhouse occupation category. The majority of jobs (51 percent) were located in five states: California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Washington. H-2A workers were mostly male (97 percent), Mexican (92 percent), under 41 years old (83 percent), and married (60 percent).

The Departments of Labor (DOL), Homeland Security (DHS), and State took steps—including prioritizing H-2A visa program applications—to keep application processing times constant from FY 2018 through FY 2023 as requests for H-2A workers increased. For example, although the number of applications DOL received increased by 72 percent, the average number of days to process an application remained between 27 and 29 days. However, DHS lacks full electronic processing of employer applications—known as petitions—for H-2A workers. Instead, employers must mail documents to DHS, and staff scan them into the agency’s database. DHS is 3 years into a 5-year plan for full electronic processing of all petitions for immigration benefits but has not included the H-2A program on its current schedule. Agency officials said they have prioritized online filing of other nonimmigrant visa classifications and critical humanitarian initiatives. However, establishing a schedule for full electronic processing of H-2A petitions would provide DHS with an accountability mechanism for the H-2A program in working toward full electronic processing and greater efficiencies.

From FY 2018 through FY 2023, 84 percent of DOL’s investigations of employers found one or more violations, with the most common violations related to pay.

DOL uses several tools to remedy violations including recovering back wages. GAO found that H-2A violations accounted for 54 percent of back wages assessed to all agricultural employers during the 6-year period GAO reviewed. DOL has taken steps to return back wages but may not have timely access to complete contact information for workers who have returned to their home countries. DOL has not assessed how or whether it could more efficiently locate such workers. By evaluating the costs and benefits of options to better locate workers, DOL may be able to strengthen its efforts to return back wages.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AEWR |

adverse effect wage rate |

|

COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

DOL |

Department of Labor |

|

FLC |

farm labor contractor |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

NOD |

notice of deficiencies |

|

OFLC |

Office of Foreign Labor Certification |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

State |

Department of State |

|

USAID |

U.S. Agency for International Development |

|

USCIS |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

|

WHD |

Wage and Hour Division |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 14, 2024

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Chair

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Chair:

Each year, some U.S. agricultural employers face a shortage of domestic workers and use the H-2A visa program to hire foreign workers to fill agricultural jobs in the U.S. Federal law allows these employers to apply for permission to hire foreign workers on a temporary or seasonal basis under temporary nonimmigrant H-2A visas.[1] Since we last reported on the H-2A visa program in 2015, the number of H-2A visas issued has more than quadrupled from about 74,000 in fiscal year (FY) 2013 to about 310,000 in FY 2023.[2]

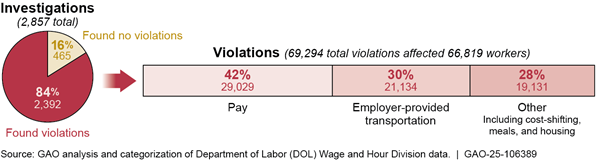

Three federal agencies—the Department of Labor (DOL), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Department of State (State)—have separate roles in administering the H-2A visa program. DOL and DHS screen employers who want to hire workers. State screens workers who apply for H-2A visas at U.S. embassies and consulates abroad. Through its U.S. Customs and Border Protection, DHS admits workers into the U.S. who have been granted an H-2A visa. DOL enforces federal employment laws and regulations pertaining to the program.

You asked us to review how the H-2A visa program has grown and federal agencies’ ability to administer and enforce the program. We examined (1) trends in the characteristics of H-2A employers, jobs, and workers in recent years; (2) the extent to which DOL, DHS, and State have taken steps to process applications in a timely manner as program uptake has increased in recent years; (3) the extent to which DOL has taken steps to investigate and remedy employer violations; and (4) steps DOL has taken to enhance workers’ ability to report potential violations and awareness of their rights.

To identify overall trends in program use, participant and job characteristics, and the timeliness of application processing, we obtained and analyzed FY 2018 through FY 2023 data—the most recent data available—on the H-2A visa program. We obtained and analyzed data from DOL’s temporary labor certification applications, DHS’s Form I-129 petitions for nonimmigrant workers, and State’s nonimmigrant visa applications. We also obtained and analyzed FY 2018 through FY 2023 data from DOL on its investigations of employers, enforcement of program rules, complaints from workers, and outreach efforts to inform workers of their rights.

To assess the reliability of agency data, we reviewed agency documentation; interviewed officials; and tested the data for missing values, outliers, and obvious errors, as appropriate. Based on these reviews, we determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting information about characteristics of H-2A applications; processing times; and DOL’s investigations, employer violations, and outreach efforts.

We interviewed five organizations representing the perspectives of agricultural workers (domestic and foreign) and six organizations representing the perspectives of agricultural employers.[3] We also met with six researchers who have studied the H-2A visa program. We selected worker and employer organizations to get a mix of national and regional organizations, with our regional selections focused on states representing a mix of those with either the largest numbers of H-2A workers or the greatest H-2A growth. We selected researchers who could provide a range of perspectives based on their expertise with immigration and labor issues and their engagement with the H-2A visa program. The perspectives of these interviewees are not generalizable but provide illustrative examples of the issues.

Finally, we reviewed DOL, DHS, and State documents—including program guidance, policies, and standard operating procedures—to understand how these agencies process H-2A applications. We compared this information to generally recognized project management practices and federal standards for internal control.[4] We also interviewed officials from each agency about their roles and activities in administering the H-2A visa program. See appendix I for more information about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2022 through November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Creation of the H-2A Visa Program

The H-2A visa program was created to help agricultural employers obtain an adequate labor supply while also protecting the jobs, wages, and working conditions of U.S. farm workers.[5] In 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act authorized the H-2 temporary worker program, which established visas for foreign workers to perform temporary services or labor in the U.S.[6] The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 amended the Immigration and Nationality Act and divided the H-2 program into two programs: the H-2A visa program expressly for agricultural employers and the H-2B visa program expressly for nonagricultural employers.[7] Federal law does not place a limit on the number of H-2A visas that can be issued.[8] Additionally, employers are required to provide H-2A workers a minimum level of wages, benefits, and working conditions. Further, generally, only workers from eligible countries are allowed to participate in the program.[9]

H-2A Visa Application Process

To participate in the H-2A visa program, employers and workers are screened by three federal agencies—DOL, DHS, and State—with separate roles and responsibilities in the application process (see fig. 1).[10]

Note: An employer may use an agent or association to submit the DOL temporary labor certification application and the DHS petition on the employer’s behalf.

· An employer submits a temporary labor certification application to DOL’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC) for specific jobs the employer is looking to fill with H-2A workers.[11] As part of the application, the employer certifies that it complies and will continue to comply with all applicable federal, state, and local laws and regulations.[12] An employer can request approval for one or more jobs for H-2A workers on the same application.[13] OFLC may approve all or some of the jobs for H-2A workers requested or deny the application. OFLC will approve the application if the employer has

· established the need for the agricultural service or labor to be performed on a temporary or seasonal basis and

· complied with all the procedural requirements as well as all applicable regulatory requirements imposed to ascertain that (1) there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are qualified and available to perform the work, and (2) employing foreign workers will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed workers in the U.S.[14]

· After OFLC approves an application, an employer submits a Form I-129 Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker to DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to request workers.[15] The petition specifies the number of nonimmigrant workers needed, which may be less than or equal to the number of jobs approved by DOL.[16] The petition includes DOL’s certification, information about the employer, the positions the H-2A workers will fill, and the workers’ names if listed by the employer.[17] USCIS can either approve all or some of the workers requested by the employer or deny the petition. Approved workers may be permitted to work up to the period of time authorized on the temporary labor certification.[18]

· Following approval of the employer’s petition by DHS, prospective workers can apply to a U.S. consulate or embassy for H-2A visas. State’s process for determining whether to issue a visa includes reviewing the application, interviewing the applicant, and completing other required security checks.[19] State may deny a visa based on certain criminal and related grounds, security and related grounds, or an applicant’s status as illegal entrant or immigration violator, among other reasons.[20] Once the visa is approved, the worker must then seek admission to the U.S. with U.S. Customs and Border Protection at a U.S. port of entry.

Recruiting and Hiring H-2A Workers

There are various ways that employers may recruit H-2A workers. We previously reported that employers generally use one of several methods to recruit workers, such as by traveling to a foreign country to interview workers themselves, using returning workers to recruit additional workers for the next season, or using third-party agents or recruiters.[21]

Farm owners and operators may employ workers directly or indirectly. We use the term “direct-hire employers” to refer to farm owners and operators that directly employ the H-2A workers who work on their farms. Other farm owners and operators employ workers indirectly, using a farm labor contractor (FLC).[22] FLCs employ H-2A workers, but do not own or operate farm sites. Like direct-hire employers, FLCs may recruit and hire workers and arrange for their travel to the U.S. either directly or with the assistance of a third-party agent or recruiter. As with direct-hire employers, FLCs are responsible for providing workers with housing. When farm owners and operators contract with FLCs, FLCs are the employers of record.[23]

H-2A Visa Program Enforcement

DOL—specifically OFLC and the Wage and Hour Division (WHD)—has the primary authority to monitor and enforce H-2A visa program regulations as well as other relevant employment laws.[24] OFLC has discretionary authority to audit adjudicated applications for compliance with the terms and conditions of the H-2A labor certification. WHD’s responsibilities include ensuring employers pay required wages and provide transportation, meals, and housing, if applicable, among other employer obligations. WHD also conducts on-the-ground investigations of employers; imposes civil money penalties; seeks legal remedies; and enforces employer obligations, including the payment of back wages.[25] OFLC and WHD have concurrent jurisdiction to debar (i.e., temporarily ban) an employer from participating in the H-2A visa program if that employer has substantially violated a material term or condition of its temporary labor certification.[26]

H-2A Employer, Job, and Worker Characteristics Were Generally Consistent from FY 2018 through FY 2023

Most Employers Hire H-2A Workers Directly

During the period of our analysis, the annual number of applications approved for the H-2A visa program increased significantly.[27] Specifically, from FY 2018 through FY 2023, the annual number of applications that DOL’s OFLC approved increased by 80 percent—from 11,319 to 20,379. DOL approved 97 percent of applications, on average.

|

Farm Labor Contractors (FLC) in the H-2A Visa Program Representatives of three employer organizations we interviewed said employers used FLCs because they provide a more efficient way to hire workers. For example, FLCs may offer economies of scale in providing housing and more efficient management of the H-2A visa program’s administrative requirements. Representatives of five employer organizations also told us that FLCs were especially beneficial for small farms. Three researchers said smaller farms turn to FLCs because H-2A visa program requirements can be difficult to navigate. Source: GAO interviews with employer organizations and researchers. | GAO‑25‑106389 |

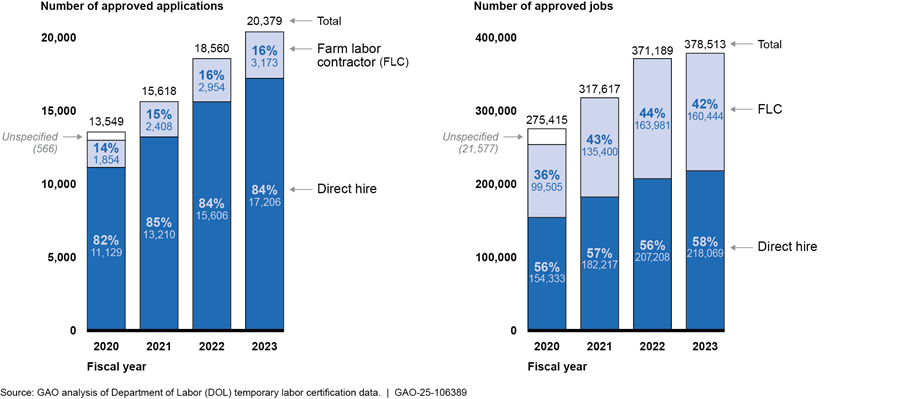

From FY 2020 through FY 2023, direct-hire employers submitted most of the applications (84 percent, on average) that OFLC approved, which accounted for 57 percent of the jobs approved during the period (see fig. 2).[28] Farm labor contractors (FLC) submitted 15 percent of approved applications and accounted for 42 percent of the jobs approved during the period. According to a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) report, FLCs usually provide workers to multiple farms.[29] We found that the average number of jobs per approved application was over four times higher for FLCs (54 jobs) when compared to direct-hire employers (13 jobs).

Notes: For the purposes of our analysis, we use the term “direct-hire” employers to mean all employers that did not contract with an FLC to hire and employ H-2A workers. Although FLC is a legal term with a specific meaning under the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act, we use the term throughout this report to refer to H-2A labor contractors. Under the H-2A regulations, an H-2A labor contractor is any person who meets the definition of an H-2A employer and is not a fixed-site employer, an agricultural association, or an employee of a fixed-site employer or agricultural association and who recruits, solicits, hires, employs, furnishes, houses, or transports any worker subject to the H-2A provisions. For additional details on how we categorized employers, see appendix I.

The number of jobs approved by DOL may exceed the number of workers issued visas. For example, employers may request fewer workers than the number of jobs approved by DOL, and therefore, the Department of State may issue fewer visas.

In each year from FY 2018 through FY 2023, employers in the crop production industry (e.g., vegetable and melon farming or fruit and tree nut farming) accounted for most of the approved H-2A applications.[30] On average, the crop production industry accounted for 60 percent of approved applications. The animal production and aquaculture industry (e.g., cattle ranching, sheep farming, or catfish farming) accounted for 18 percent of approved applications. Another 17 percent of approved applications were in the support activities for the agriculture and forestry industry (e.g., the work of FLCs).[31]

H-2A Jobs Were Concentrated in a Few Occupations and Locations

From FY 2018 through FY 2023, while the number of H-2A jobs increased significantly, the occupations and locations of jobs remained relatively consistent. Specifically, the number of H-2A jobs that DOL’s OFLC approved increased by 56 percent—from 242,762 to 378,513—with DOL approving 99.8 percent of jobs in employer applications. Nearly all H-2A jobs were in one occupation, and over half were in five states.

|

Potential Factors Contributing to H-2A Visa Program Growth Several factors may have contributed to the H-2A program’s growth, according to researchers and stakeholder groups we interviewed, including: · decreased supply of domestic agricultural workers as (1) agricultural workers aged out of the labor force, (2) younger workers opted for work in other industries, and (3) individuals without lawful immigration status could be subject to removal from the U.S.; · employers expanded use of H-2A workers for a broader set of crops and occupations and for longer periods during the year; and · employer preference for H-2A workers over domestic workers. Source: GAO interviews with employer organizations, worker organizations, researchers, and Department of Labor officials. | GAO‑25‑106389 |

Job occupations. In each year from FY 2018 through FY 2023, the vast majority of approved H-2A jobs were in the farmworkers and laborers, crop, nursery, and greenhouse occupation.[32] On average, jobs in this occupation made up 87 percent of approved jobs. The next most common occupation was agricultural equipment operators with 6 percent of approved jobs.[33]

Jobs in most H-2A applications were physically demanding. According to our analysis of DOL data, between FY 2020 and FY 2023, jobs in 84 percent of approved applications, on average, had lifting requirements and involved exposure to extreme temperatures, and jobs in 73 percent of approved applications involved repetitive movements.[34]

According to a 2021 USDA report, most approved jobs paid the H-2A visa program’s minimum wage, which is known as the adverse effect wage rate.[35] From FY 2011 through FY 2019, 95 percent to 97 percent of approved jobs offered the H-2A visa program’s adverse effect wage rate.

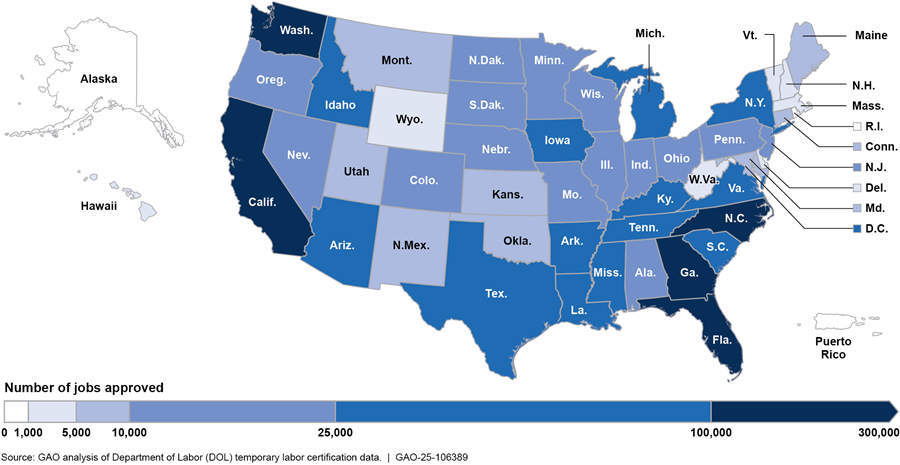

Job locations. In each year from FY 2018 through FY 2023, over half of approved H-2A jobs were concentrated in five states. Specifically, California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Washington collectively accounted for 51 percent of approved jobs, on average (see fig. 3). Florida and Georgia had the highest shares of H-2A jobs during the period, with 14 percent and 11 percent of jobs, respectively. Among regions, the South accounted for the largest share of jobs with 51 percent, and the Northeast accounted for the smallest share with 6 percent. The West and Midwest made up 29 percent and 14 percent, respectively.

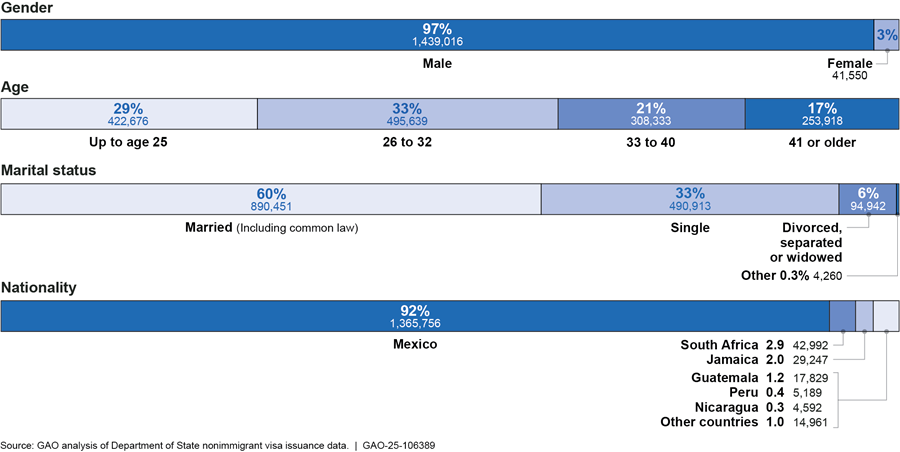

Most Workers Issued H-2A Visas Were Male, from Mexico, under 41 Years Old, and Married

From FY 2018 through FY 2023, while the number of H-2A visas increased significantly, worker demographics remained consistent. Specifically, the number of H-2A visas that State issued from FY 2018 through FY 2023 increased by 58 percent—from around 196,000 to almost 310,000—with State approving 95 percent of H-2A visa applications during the period.[36] In each year from FY 2018 through FY 2023, most workers issued H-2A visas were male, from Mexico, under 41 years old, and married (see fig. 4).

|

Agency Efforts to Address Gender-Related Issues in H-2 Visa Programs The White House established the H-2B Worker Protection Taskforce to address issues in the H-2B program, which allows employers to hire workers to fill nonagricultural positions. The taskforce issued a report in October 2023 that addressed some issues pertaining to both the H-2B and H-2A visa programs. In its report, the taskforce stated that while the Department of Labor, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of State currently collect data about worker sex, these data are not centralized. According to the taskforce, comprehensive data about the sex of H-2A and H-2B workers support agencies’ efforts to prevent discrimination and enforce employment laws, to conduct stakeholder outreach and advocacy efforts, and to support efforts to address sexual harassment and gender-based violence. The taskforce stated that it will aggregate, share, and publish existing data about the sex of H-2B and H-2A workers. Source: White House H-2B Worker Protection Taskforce, Strengthening Protection for H-2B Temporary Workers, October 2023. | GAO‑25‑106389 |

In interviews, we heard that employers may select workers based on demographic characteristics. Specifically, representatives from four of five worker organizations we interviewed stated that H-2A workers are recruited based on age and sex. A representative from one of these worker organizations explained that the structure of the H-2A visa program (i.e., how the employer recruits and hires workers) gives employers the ability to select workers with specific characteristics.[37]

Agencies’ Efforts Kept H-2A Visa Processing Times Constant but May Result in Unintended Consequences

Although DOL, DHS, and State received large increases in applications for the H-2A visa program from FY 2018 through FY 2023, the time it took the agencies to process applications remained generally stable. Agency officials took steps to maintain processing times for H-2A applications to ensure the availability of a seasonal agricultural workforce. All three agencies reported gaining efficiencies in the adjudication process through transitions to electronic application processing during the period of our review; however, DHS’s USCIS has not included H-2A in its schedule for full electronic processing of applications across the agency. Agencies’ approaches to processing H-2A applications amid growth may have unintended consequences for the agencies, such as for their ability to perform oversight, process adjudications for other programs in a timely manner, and ensure workers are provided with information about their rights.

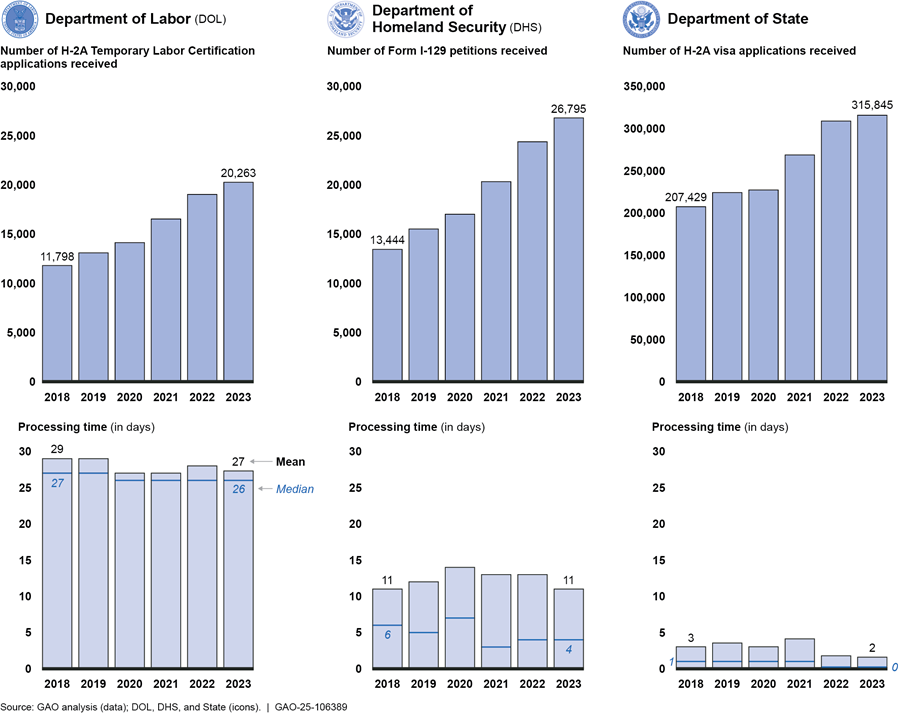

Agencies’ Application Processing Times Remained Constant Even as the Number of H-2A Applications Grew

As DOL, DHS, and State experienced large increases in applications for the H-2A visa program from FY 2018 through FY 2023, the time it took the agencies to process applications remained generally stable (see fig. 5).[38] For example, the number of H-2A applications DOL’s OFLC received increased by 72 percent during the period. At the same time, the average number of days it took the agency to process an application remained between 27 and 29 days.

Notes: For DOL and DHS, we defined processing times using the date the application or petition was received by the agency to the date of the final adjudication determination. For State, we defined the processing time as the date the consulate began adjudication to the date of the final adjudication determination. State begins adjudication once it has received both the approved DHS Form I-129 petition and the visa application, and the applicant has scheduled an interview and paid the required fees.

The number of applications processed may not equal the number of applications received. Processing times across the agencies are not comparable for reasons including differences in processing tasks. In addition, the numbers of applications across the three agencies differ due to the nature of each application. For example, one application for a DOL temporary labor certification or one DHS Form I-129 petition may include multiple workers. However, a visa application is for an individual worker.

Although processing times have remained constant, officials from all three agencies said there are busier periods of time throughout the year due in part to the seasonal needs of agricultural employers in the U.S. For example, in the period of our analysis, DOL’s OFLC received 56 percent of its H-2A applications from December to March; DHS’s USCIS received 50 percent of H-2A petitions from January to April; and State received 51 percent of its H-2A visa applications from February to May.

DOL, DHS, and State reported additional factors that affect their processing times.

· DOL. The application review process may be prolonged if an employer has not submitted sufficient documentation with the application. In such cases, OFLC staff send the employer a notice of deficiency requesting additional information before the application review can proceed. Employers generally have 5 business days to submit the requested documentation for review, which can extend the application’s processing time.[39] Requirements specific to FLCs can also contribute to longer processing times. For example, FLCs must provide proof of surety bonds when they apply to DOL, which can take more time to review, according to OFLC officials.[40]

· DHS. Similarly, USCIS may require the employer to provide additional information—known as a request for evidence—before the agency issues a final decision on the petition. USCIS officials told us the agency provides 87 days (including mailing time) for employers to submit the requested evidence for review, which can extend the processing time.[41] Processing times for USCIS may also increase when the employer specifies the name of the worker they are requesting, according to USCIS officials.[42] For named workers, USCIS conducts security and background checks. In addition, petitions with named workers must include additional documentation that USCIS must review and verify. The number of named workers has grown over the past 6 years (see text box).

|

Growth in U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) H-2A Petitions with Named Workers · Generally, employers are only required to name H-2A workers on the Form I-129 petition who are already in the U.S. or are nationals of a country not designated as eligible to participate in the H-2A visa program. · The number of workers that employers named on H-2A Form I-129 petitions nearly doubled in the 6-year period we reviewed from 37,939 in fiscal year (FY) 2018 to 74,699 in FY 2023. · The number of petitions with at least one named worker more than doubled in the period of our analysis from 2,744 to 6,953. · Petitions with at least one named worker grew as a share of total petitions from 21 percent in FY 2018 to 26 percent in FY 2023. · USCIS officials said there may be various reasons for the growth of named workers. For example, as the program has grown, employers may find it more efficient to hire H-2A workers who are more accessible and already in the U.S. · As of April 2024, USCIS implemented changes that seek, in part, to reduce the burden associated with processing petitions with named workers. For example, USCIS now requires a maximum limit of 25 named workers on a single petition in several nonimmigrant classifications, including H-2A. USCIS officials said this change would help reduce the burden, complexity, and technical issues associated with using a single petition for hundreds of named workers. In September 2023, USCIS also proposed a change—which it expects to finalize in November 2024—to allow H-2A workers to switch employers more easily while staying in the U.S. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) USCIS petition data; DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Fee Schedule and Changes to Certain Other Immigration Benefit Request Requirements, 89 Fed. Reg. 6,194 (Jan. 31, 2024); and DHS’s Modernizing H-2 Program Requirements, Oversight, and Worker Protections, 88 Fed. Reg. 65,040 (Sept. 20, 2023). | GAO‑25‑106389

· State. State officials told us that various factors may lengthen the time it takes to process H-2A visas. State must receive the application package—both the DHS approved Form I-129 petition and the visa application—and the applicant must have an interview scheduled with the embassy or consulate and have paid the required fees to proceed with adjudication. However, State officials said some employers may wait months to schedule an appointment to align the time of the interview with when workers are needed.

Another key factor that can affect processing times is whether the embassy or consulate must interview the applicant. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in March of 2020, State used its statutory waiver authority to allow consular officers the discretion to waive certain nonimmigrant visa interviews, including those for H-2A visa applicants. In December 2023, State, in coordination with DHS, decided to indefinitely provide consular officers with flexibility to waive certain nonimmigrant visa interviews.[43] In FY 2023, consular officials waived 90 percent of H-2A interviews compared to 43 percent in FY 2018. State officials said the interview waiver has helped the agency maintain H-2A visa application processing times while visa requests have increased and has also allowed consular officers to focus on high-risk visa applicants.

Additionally, State officials said an ongoing fraud investigation could cause delays in adjudicating a visa application. For example, State may investigate potential fraud identified during its application prescreening.

Agencies Prioritized H-2A Applications to Maintain Processing Times

DOL, DHS, and State officials reported prioritizing H-2A applications to ensure the availability of a seasonal agricultural workforce.

DOL. Federal law generally requires OFLC to approve H-2A applications no less than 30 days before an employer’s date of need for workers, provided the employer has met the requirements.[44] OFLC officials said they use the date of need as a guide for prioritizing applications by processing applications with earlier dates of need first.

To further prioritize H-2A applications and help meet its legal obligation, DOL has a formal performance target of processing roughly 97 percent of completed applications 30 or more days before the date of need. According to our analysis, OFLC met this target in FY 2023.[45] When we included applications that OFLC excluded due to delays outside of the adjudicator’s control in our analysis, this dropped to 63 percent.[46] OFLC officials said that they exclude certain applications from the calculation when there are factors outside of OFLC’s control that prolong application processing, such as delays related to the housing inspections that state workforce agencies and employers must work together to schedule and complete.[47] To address such delays, OFLC officials said they work to facilitate communication between the state workforce agencies and the employer. In addition, OFLC recently updated its online system to give state workforce agencies the ability to enter notes that provide the employer with information about the status of the inspections.

DHS. DHS’s USCIS has an overall goal of processing Form I-129 petitions within 2 months of receipt; however, they aim to process 80 percent of Form I-129 petitions for H-2A workers, specifically, within 15 days, according to USCIS officials.[48] Our analysis of USCIS data found that from FY 2018 through FY 2023, USCIS processed over 80 percent of H-2A petitions within 15 days, meeting the agency’s 80 percent target. USCIS officials told us that managers actively monitor H-2A processing times and filing volumes to ensure they meet their 15-day organizational goal.

State. According to State officials, because the H-2A visa program is considered a matter of national security, the agency prioritizes H-2A visas over other visa types.[49] State’s need to prioritize H-2A visas varies by consular office because some countries have more H-2A visa applicants than other countries. For example, 92 percent of H-2A visas were issued for workers of Mexican nationality during the period of our review. According to State officials, its consulates in Mexico aim to issue H-2A visas within 3 days of when the consulate receives the application package, and the applicant has scheduled an interview. According to our analysis of State data, from FY 2018 through FY 2023, State’s consulates processed nearly 92 percent of H-2A applications within 3 days.[50]

Agencies’ Digital Capabilities Helped Maintain Processing Times, but DHS Lacks Full Electronic Processing

DOL, DHS, and State reported gaining efficiencies in the application review process through transitions to electronic application processing during the period of our review, but DHS’s USCIS has not included H-2A in its schedule for full electronic processing of applications across the agency.

DOL. OFLC transitioned from paper to electronic processing of applications and supporting documents in 2019, according to agency officials. OFLC officials said that before this transition, a significant amount of time was devoted to printing and mailing forms. OFLC officials told us that the fully digital application also helped keep processing times low by reducing the number of applications with deficiency notices (see text box). For example, the digital application prevented employers from submitting the application with blank fields. Digitization also reduced discrepancies and inconsistencies between different forms, according to OFLC officials.

|

Fluctuations in Department of Labor (DOL) H-2A Applications with Notice of Deficiencies (NOD) The percentage of H-2A applications with NODs fluctuated in the 6-year period we reviewed, according to our analysis. Due to electronic efficiencies, NODs declined from fiscal year (FY) 2018 through FY 2022 from 44 percent of total applications (5,159) to 29 percent of total applications (5,540). However, in FY 2023, NODs increased to 46 percent of total applications (9,695)—which represents nearly double the applications with NODs in the previous year. Officials from DOL’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification said this increase was related to recent regulatory changes that employers must learn to navigate. DOL’s 2022 Final Rule included several changes related to wage adjustments and housing standards, among other things. Officials said they conducted outreach and stakeholder education to help employers understand the new requirements. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOL’s temporary labor certification data and interviews with Office of Foreign Labor Certification officials. | GAO‑25‑106389

DHS. According to USCIS officials, the agency has taken steps to enhance its capability to process H-2A Form I-129 petitions electronically since 2021; however, it still relies on paper communication for many steps in the petition review process. Specifically, USCIS transitioned to a new case management system to allow for petition decisions to be communicated electronically, but employers must submit paper petitions and supporting documentation to USCIS by mail. USCIS staff then enter or scan these paper documents into USCIS’s electronic data system before they can review the petitions electronically. When necessary, USCIS mails the employer a request for evidence, and the employer must mail the requested documents back to USCIS. When USCIS receives the paper documentation, staff then scan and upload these documents to USCIS’s electronic system.

As USCIS officials reported, petitions requiring additional evidence take longer to process.[51] Our analysis of USCIS data shows that in FY 2023, average processing times for petitions requiring a request for evidence were nearly 10 times greater than petitions without (68 days compared to 7 days). This is an increase from FY 2018, when the average processing times for petitions requiring a request for evidence were six times greater than petitions without (42 days compared to 7 days). However, the share of petitions with a request for evidence declined from FY 2018 through FY 2023, from 12 percent to 7 percent.[52] Although petitions that require additional evidence inherently take more time to process than those that do not, reducing the need for communication and submissions by mail would likely speed up the process.

USCIS has been modernizing its paper-based immigration benefits process since 2006 but has not included H-2A in its current schedule for full electronic processing.[53] DHS’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that USCIS’s reliance on paper files created further backlogs during the COVID-19 pandemic.[54] In 2021, as required by law, USCIS developed a 5-year plan for, among other things: establishing electronic filing procedures for all petitions for immigration benefits; issuing correspondence electronically, including requests for evidence; and improving processing times.[55] USCIS has reported progress in achieving end-to-end electronic processing across its lines of business.[56] For example, since developing its 5-year plan, its end-to-end electronic capability for nonimmigrant petitions has increased from 17 percent to 54 percent.[57]

However, the 5-year plan has not yet included the H-2A visa program, and USCIS has not included the H-2A visa program on its current digitization schedule. USCIS officials said they did not have a timeline for the H-2A visa program but anticipated making progress on its capability to receive and respond to requests for evidence online in FY 2025 and online filing at a future undetermined date. The officials said H-2A is not a current focus due to critical humanitarian initiatives and other projects that USCIS has prioritized, including online filing of other nonimmigrant visa classifications. However, as discussed previously, federal law required USCIS to develop a 5-year plan for all petitions, regardless of their priority. Further, given the growth of the H-2A visa program, a schedule would better position USCIS to meet this growing demand.

A key component of project planning is developing a schedule for executing project activities, according to generally recognized project management practices from the Project Management Institute.[58] Using a schedule can help to measure actual performance against planned performance to determine whether deliverables and outcomes are being achieved as planned. Further, milestones and detailed schedules help ensure commitment to and implementation of deliverables. Given that USCIS is 3 years into its 5-year plan, establishing a schedule, including milestones, for complete end-to-end electronic processing of H-2A visa program petitions would provide USCIS with an accountability mechanism and better position USCIS to make program improvements before the end of the 5-year period.

State. Workers apply for their H-2A visa online through State’s website. In addition, since 2019, State has automatically received the USCIS-approved Form I-129 petitions—which contain information used to process the visa applications—electronically from DHS. Prior to that time, State relied on mailed copies of approved Form I-129 petitions—which officials estimated took 5 to 7 days to receive—and manually entered the information into its own electronic system for processing. Now, according to State officials, the agency typically receives the approved petition hours after USCIS approves it, and its intake center conducts initial intake of the information within 24 hours. Likewise, State conducts initial intake of workers’ online visa applications within 24 hours of the applicant’s submission so that the consular staff can begin prescreening the application.

Agencies’ Approaches to Processing H-2A Applications Can Affect Oversight, Other Programs, and Workers’ Access to Rights Information

As the H-2A visa program continues to grow, agencies’ approaches to prioritizing H-2A applications may result in unintended consequences for their effectiveness in overseeing the program, processing applications for other programs in a timely manner, and ensuring workers are provided with information about their rights.

Effect on Oversight

In recent years, DOL reported its concerns that H-2A visa program integrity may be affected by the need to process applications in a timely manner.[59] DOL’s OFLC audits approved H-2A applications to help ensure program integrity. Because these audits are a discretionary activity, in recent years, OFLC has audited fewer approved applications, in part, to handle the rise in applications, according to OFLC officials. Specifically, in a report to Congress, OFLC reported that in FY 2018, it concluded over 500 audits of H-2A applications.[60] In FY 2023, it concluded approximately 30 audits, according to data we reviewed. OFLC officials attributed the reduction in H-2A audits to the competing priorities of OFLC staff. Specifically, OFLC officials told us that they have limited resources to conduct audits because the same staff who process applications also audit the approved applications. Further, they told us the same staff conduct audits of other visa applications, and in some years, they must prioritize audits of one program over the other due to limited resources.

To manage its audit efforts, in 2021, in response to a recommendation by DOL’s OIG, OFLC developed a risk-based strategy to identify which adjudicated applications to audit.[61] OFLC also conducts oversight through supervisory reviews of certain H-2A applications during the approval process, although as with the audits, OFLC officials told us there is less time to conduct these reviews because staff are focused on application processing.[62]

Effect on Other Visa Programs

DOL officials reported that prioritizing H-2A applications adds to backlogs or waitlists in other programs. For example, DOL has reported that prioritizing H-2A applications has shifted staff away from processing immigrant permanent labor certification applications, even though demand for that program has also increased.[63] DOL’s OIG has reported on the lengthy application processing times for permanent labor certifications and has also reported that OFLC’s reallocation of staff to temporary visa programs during peak seasons decreases the number of permanent labor certification applications subject to audit review.[64] Further, DOL officials stated that the filing season for H-2A workers has lengthened as the program has grown (see table 1). As a result, they said it is more difficult to shift staff around to meet processing needs, which may affect processing of other visas.

|

|

DOL received over 1,000 H-2A applications… |

In January, applications peaked at… |

|

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 |

· in each of 5 months of the year |

· 2,012 applications |

|

In FY 2023 |

· in each of 9 months of the year |

· 4,164 applications |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Labor’s (DOL) temporary labor certification data. | GAO‑25‑106389

Similarly, USCIS and State officials told us that the prioritization of H-2A visas slows down the processing for other programs. For example, State officials said that many consular offices, especially in Mexico, focused significant resources on processing H-2A visas during peak season—February and March, in particular. This may result in longer wait times for interviews for other visa classifications during these months, according to the officials. The agencies have taken some steps to address the impact of H-2A visa program growth on other programs. For example, DOL has requested Congress allow it to implement new fees or leverage existing fees to help it access more resources.[65]

Effect on Workers’ Access to Rights Information

State requires consular officers to inform H-2A visa program applicants of their rights while in the U.S. but waiving the visa interview may limit whether workers receive this information. During the visa interview, consular officers must ensure applicants are provided the “Know Your Rights” pamphlet.[66] State officials said that when an interview is waived, consular officers include the pamphlet and a card with a QR code linked to the online pamphlet with the applicant’s passport when it is returned to the applicant with the H-2A visa. State officials said the workers’ representatives, such as recruiters who work for the employer, may pick up the passports at the consulate on the workers’ behalf to distribute to the workers. However, State officials said the recruiters may not deliver the pamphlets to the workers. Further, DOL’s OIG has found instances of employers and their representatives confiscating workers’ passports and charging fees in return for visas, suggesting that some employers may not prefer to provide H-2A workers with the information about their rights.[67]

State officials said they are taking additional steps to help ensure workers have direct access to the information in absence of the interviews. For example, they said that when completing the visa application online, workers must certify that they have read the “Know Your Rights” information to be able to continue with the application. In addition, applicant service centers, where workers go for fingerprinting and photos, display the “Know Your Rights” posters with the QR code. In May 2023, State issued a public notice for input on the “Know Your Rights” pamphlet. State officials told us that the agency is reviewing the input it received to improve the distribution methods of the “Know Your Rights” information, such as making the pamphlet, as well as a video with the information, available at major ports of entry, using social media, emailing applicants, and disseminating the pamphlet through foreign government consulates.

DOL Investigations Find High Rates of Violations, and Incomplete Information May Constrain Back Wage Repayment Efforts

DOL’s WHD investigates and penalizes employer violations of H-2A workers’ rights when the law and resources permit. Most H-2A investigations are agency directed rather than stemming from worker complaints, and most H-2A investigations uncover violations, according to our analysis of WHD data. To accommodate limited resources for enforcement, WHD uses strategies to target high-risk H-2A employers. After uncovering a program violation, WHD can impose civil money penalties, require employers to pay workers’ back wages, or debar employers from participating in the H-2A visa program in the future, among other actions. However, WHD has not assessed the costs and benefits of options to reduce the resource burden on WHD to return back wages.

DOL Investigates Few H-2A Employers, but Investigations Find High Rates of Violations

Investigations

WHD investigates a small share of H-2A employers. For example, according to our analysis of DOL data, from FY 2018 through FY 2023, OFLC certified 92,051 H-2A applications submitted by employers.[68] In that same 6-year period, WHD concluded 2,857 investigations of H-2A employers.

WHD has a limited number of investigative staff to conduct wide-ranging enforcement obligations. In its FY 2022–2026 Strategic Plan, DOL reported that declining staff numbers in the preceding several years hindered its ability to carry out investigations, inspections, and other mission-critical activities. As the H-2A visa program continued to grow, WHD reported operating with one of the lowest investigator levels in the last 50 years, with 773 investigators in FY 2023. These investigators are responsible for agricultural labor standards as well as all WHD regulatory responsibilities, such as federal minimum wage and overtime enforcement.[69]

In the period of our review, most H-2A investigations were directed by the agency rather than stemming from worker complaints. According to our analysis of WHD data, from FY 2018 through FY 2023, 85 percent of WHD’s H-2A investigations were agency directed, and 15 percent stemmed from complaints, on average. Although WHD prioritizes complaint-based investigations over agency-directed investigations in accordance with its policy, WHD conducts more agency-directed investigations because it receives few complaints.[70] WHD’s 2023 Cross-Regional Agricultural Worker Initiative report states that H-2A workers are reluctant to complain because reporting a violation poses a risk to their jobs, housing, H-2A visas, and opportunities for future work.

Since WHD receives few complaints from workers and has limited investigative resources, WHD has developed strategies for targeted agency-directed investigations of agricultural employers in general and among H-2A employers in particular. According to WHD officials, the agency uses targeted investigations that aim to encourage compliance across geographic locations or industries. For example, WHD’s 2023 Cross-Regional Agricultural Worker Initiative report outlines four case selection strategies that use data, research, and stakeholder expertise to target investigations. These strategies target agricultural actors that have certain characteristics (e.g., crop type, employer type, geographic location) associated with a higher likelihood of violations or a high concentration of agricultural laborers. According to WHD’s Agency Management Plan, in FY 2023, 70 percent of WHD’s compliance actions were attributed to an initiative, like the Cross-Regional Agricultural Worker Initiative.

Because FLCs account for a disproportionate share of debarments, they are a strategic target of some WHD investigations, according to WHD officials. For example, the strategies in WHD’s Cross-Regional Agricultural Worker Initiative focus on investigating FLCs. According to WHD officials, there is widespread concern about the role that FLCs play in labor exploitation, which can include labor trafficking. According to our analysis of DOL data from FY 2018 through FY 2023, FLCs made up 21 percent of investigations (589 of 2,857) and 37 percent of H-2A visa program violations (25,335 of 69,294). From FY 2020 through FY 2023, FLCs made up 54 percent of debarments (31 of 57).[71] As stated previously, FLCs accounted for 15 percent of approved applications and 42 percent of the jobs certified in the H-2A visa program, on average, from FY 2020 through FY 2023. According to our analysis, most violations are charged on a per-worker basis, which may partly explain why FLCs account for a higher share of violations than applications.

The mobile nature of FLC operations may pose additional risks to worker safety, according to WHD officials. WHD officials said that FLCs are more likely than other employers to move workers to jobs outside of approved work locations (i.e., the intended area of employment). Officials noted that this practice can create a cascade of violations. For example, housing and transportation in these other locations may not have been inspected or approved. Likewise, because different localities may require different wages, when FLCs transport workers outside of certified work locations, they may fail to adjust pay appropriately.

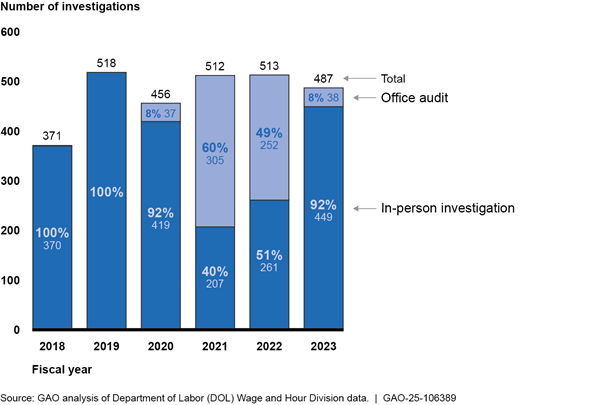

WHD primarily conducted investigations in person during the 6-year period we reviewed but relied more heavily on office audits in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to our analysis. WHD uses two methods to inspect employer compliance with H-2A visa program rules: in-person investigations and office audits.[72] In-person investigations include visits to the work site; interviews with workers; safety inspections of vehicles used to transport workers; health and safety investigations of housing; and, when applicable, inspections of field sanitation standards. Office audits focus on reviewing files and do not involve a site visit.

In the 6-year period we reviewed, the number of office audits WHD conducted peaked in FY 2021, making up 60 percent of H-2A investigations (see fig. 6). WHD reported pivoting to conduct more office audits in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as a health and safety precaution for both workers and investigators.[73] These virtual enforcement efforts allowed the agency to dedicate resources to uncovering wage violations—such as underpayment of workers or illegal pay deductions—which made up the top category of violation in FY 2021. Our analysis shows that back wages assessed in the 6-year period we reviewed peaked in FY 2021 at over $7 million.

Note: In our analysis of WHD data, we found that three additional compliance actions were used on one occasion each during the 6-year period: one self-audit, one conciliation (through remediation to resolve the complaint), and one housing pre-occupancy inspection. For reporting purposes, we excluded these compliance actions from this figure. Our analysis of in-person investigations encompasses WHD’s limited investigations and full investigations because both compliance actions involve on-site investigations.

However, WHD officials emphasized that in-person investigations are a key component of WHD enforcement efforts. DOL has reported that agricultural workers are often subject to unsafe housing, transportation, and working conditions, which may be difficult to uncover through office audits. According to our analysis of WHD data, the agency has begun to return to pre-pandemic levels of in-person investigations. As shown in figure 6, 92 percent of investigations were conducted in-person in FY 2023.

Violations

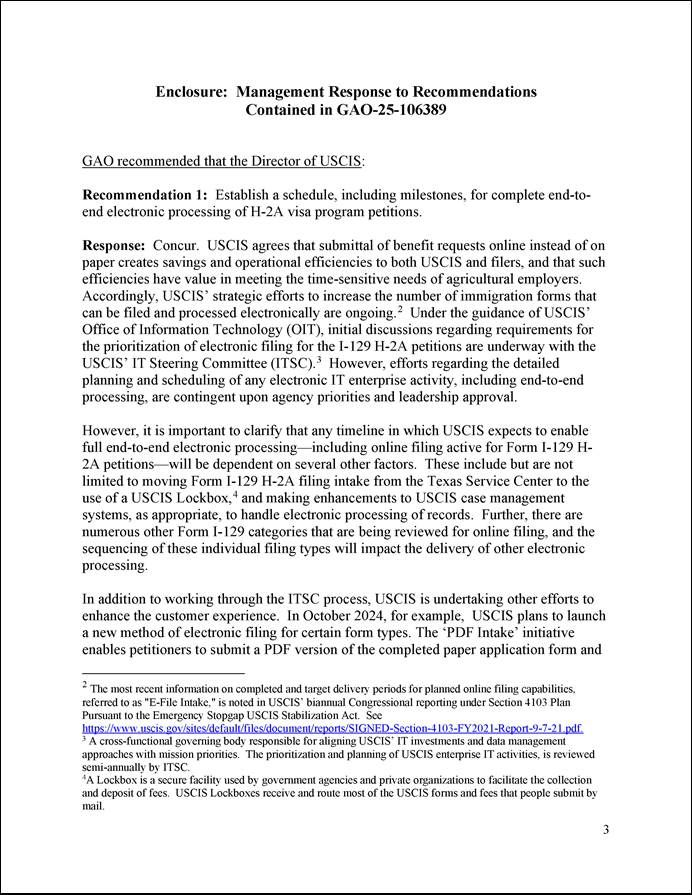

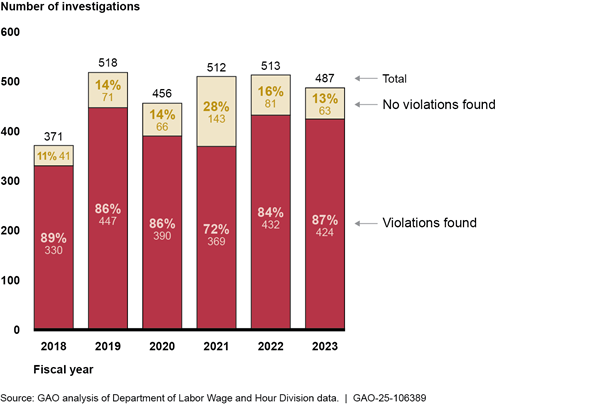

In the 6-year period we reviewed, most investigations of H-2A employers uncovered violations. From FY 2018 through FY 2023, WHD concluded 2,857 investigations of H-2A employers. Eighty-four percent (2,392) of investigations found one or more H-2A violations, accounting for a total of 69,294 H-2A violations affecting 66,819 workers (see fig. 7). In that period, of those employers found to have at least one violation, 45 percent had more than 5 violations.

Figure 7: Wage and Hour Division (WHD) H-2A Investigations That Found Violations, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: WHD staff may calculate violations on a per-requirement basis or a per-worker basis, according to WHD’s Field Operations Handbook. For example, an employer that fails to properly house 10 workers may receive one violation (one per requirement) or 10 violations (one per worker). Particularly egregious violations, willful violations, and violations significantly and adversely affecting workers are more likely to be calculated on a per-worker basis.

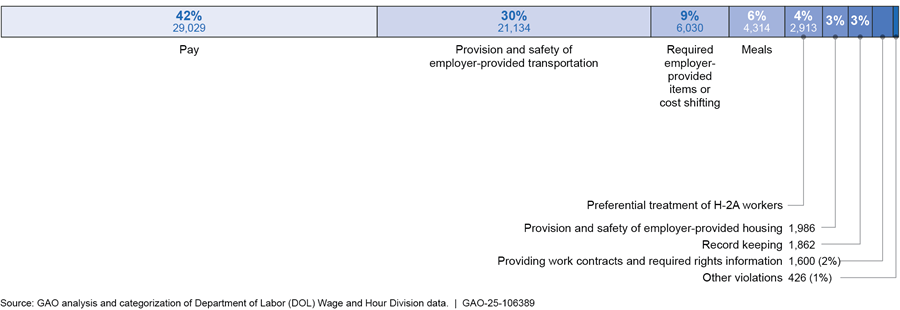

The most common violations uncovered in WHD investigations were related to pay (42 percent), provision and safety of transportation (30 percent), and illegal charges and fees (9 percent) for employer-provided items such as bedding or work supplies (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Violations Uncovered by DOL’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) in the H-2A Visa Program, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: WHD staff may calculate violations on a per-requirement basis or a per-worker basis, according to WHD’s Field Operations Handbook. For example, an employer that fails to properly house 10 workers may receive one violation (one per requirement) or 10 violations (one per worker). Particularly egregious violations, willful violations, and violations significantly and adversely affecting workers are more likely to be calculated on a per-worker basis. For reporting purposes, we consolidated WHD violations into the nine broad categories shown above. See appendix I for more information about how we consolidated categories.

Investigations of H-2A employers often uncover violations of other labor laws in addition to H-2A violations, according to our analysis of WHD data. From FY 2018 through FY 2023, 39 percent of investigations that found H-2A violations also found violations of other labor laws.[74] As described in WHD’s Field Operations Handbook, every investigation of an H-2A employer includes a concurrent investigation of the employer’s compliance status with the Fair Labor Standards Act and Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act. According to WHD officials, investigators may also evaluate compliance with other rules such as child labor laws and Occupational Safety and Health Act field sanitation and temporary labor camp standards. Of cases with violations co-occurring with H-2A, 69 percent were Fair Labor Standards Act violations and 26 percent were Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act violations.

DOL Uses Several Tools to Remedy Employer Violations but May Face Difficulties Returning Back Wages

To remedy violations of H-2A visa program rules by employers, DOL’s WHD has the statutory authority to impose civil money penalties (i.e., fines), recover back wages (i.e., unpaid wages) for workers, and debar (i.e., temporarily ban) violators from future participation in the program, among other actions.[75] However, WHD faces difficulties returning back wages to workers.

Civil Money Penalties

WHD considers civil money penalties whenever it finds violations, according to WHD regulations. To determine the penalty amount, WHD considers the type of violation, the gravity of the violation and its impact on the worker(s), and the circumstances surrounding the violation, among other things.[76] From FY 2018 through FY 2023, WHD assessed over $25 million in H-2A civil money penalties, according to our analysis of WHD data. According to data presented on WHD’s website, from FY 2018 through FY 2023, H-2A violations accounted for 63 percent of civil money penalties assessed to all agricultural employers.[77]

Back Wages

In response to wage violations, WHD may order that an employer pay back wages to make up the difference between what the worker was paid and the amount they should have been paid.[78] From FY 2018 through FY 2023, WHD assessed over $20 million in H-2A back wages, according to our analysis of WHD data. According to calculations presented on WHD’s website, from FY 2018 through FY 2023, H-2A violations accounted for 54 percent of back wages assessed to all agricultural employers.[79] According to agency officials, about 75 percent of back wages are paid directly to workers by the employers.

If an employer is unable to find the worker, WHD collects the back wages from the employer and must make every reasonable effort to locate the worker, according to WHD’s Field Operations Handbook. As of March 2024, WHD officials told us that roughly 80 percent of back wages assessed from FY 2018 through FY 2023 had been successfully returned to workers, including both back wages returned directly by employers and those returned by WHD. Although the majority of back wages are returned to workers—and most by employers—roughly 20 percent of back wages assessed in the period of our review did not get returned to workers.

WHD has taken steps to increase the share of back wages returned to workers. Specifically, according to WHD’s Fiscal Year 2022 Agency Management Plan, the agency is increasing its efforts to inform workers about how to contact WHD for back wages they may be owed.[80] For example, WHD has launched a public service campaign to raise the visibility of its online tool, Workers Owed Wages, which allows workers to search for unclaimed wages. In FY 2022, WHD set its first agency-wide performance goal to return 79 percent of back wages to workers, which it met. WHD then increased the goal to 82 percent in FY 2023. Further, according to DOL’s FY 2024 Budget in Brief, the agency is requesting budget increases that would support the hiring of 105 full-time staff in several enforcement positions, including back wage follow-up specialists.[81]

Although the agency has taken steps to get more back wages into the hands of workers, WHD still faces challenges finding workers in a timely and efficient manner. WHD does not always have timely access to complete contact information to locate and disburse back wages to workers who have returned to their home countries. WHD officials told us that employers sometimes fail to keep workers’ permanent addresses even though DOL requires that employers keep these records on file for 3 years after the H-2A application was certified by OFLC. DOL does not require employers to submit this information to the agency unless it is requested by WHD for an investigation.[82] As a result, WHD staff may learn that workers’ address information is missing after workers have returned to their home countries, which makes returning back wages more difficult.

WHD’s efforts to return back wages to unlocated workers may inefficiently use agency resources and delay worker repayment. According to WHD officials, in instances where employers fail to pay the workers the back wages directly, WHD staff attempt to reconstruct worker contact information through different avenues, such as through data from other federal agencies, employers, and other means. For example, State may have contact information from visa applications. In addition, WHD officials said WHD staff may be able to find additional contact information from employer records. Further, according to WHD officials and WHD’s Field Operations Handbook, staff also use several additional avenues to locate workers—such as social media, internet searches, phone directories, and internet locator applications. WHD officials told us they do not track how long it takes them to find workers and return back wages. Two worker organizations we interviewed expressed concerns that H-2A workers often do not receive back wages for 2 or 3 years, or at all. When WHD is unable to locate employees after 3 years, they are required to transfer any remaining monies from back wages to the U.S. Treasury.

WHD officials said they had not assessed options for efficiencies that may reduce the resources WHD must invest in locating workers to return back wages. For example, WHD could explore ways to incentivize employers to retain worker information or find workers or ways to streamline its own methods for locating workers. Given that employers have direct contact with workers and have more success in returning back wages than WHD, identifying and implementing incentives could reduce the resource burden placed on WHD. Federal internal controls state that management should use quality information to achieve agency objectives and emphasize developing efficient structures and operations that minimize the waste of resources.[83] By identifying and evaluating various options to reduce the resource burden on WHD to return back wages, including the costs and benefits of those options, WHD may be able to improve efforts to return back wages, as well as potentially increase the amount of back wages returned to workers.

Debarment

According to statute, DOL can debar—temporarily ban for up to 3 years—an employer that violates certain H-2A visa program rules. Debarment is reserved for substantial violations and is used sparingly; DOL debarred 121 employers from FY 2018 through FY 2023.[84] For example, in May 2022, DOL debarred an Ohio nursery owner for 3 years for repeatedly violating H-2A visa program rules, intimidating and threatening workers, and denying workers their full wages.[85] In addition, in October 2022, DOL debarred a Florida-based FLC from participating in the H-2A visa program for 3 years. Two DOL investigations found that the FLC failed to pay workers the minimum required wage and failed to provide employees with copies of their work contracts, among other violations.[86]

|

H-2A Visa Program Offenses Subject to Employer Debarment The Department of Labor has the authority to debar employers for substantial violations. Examples of offenses subject to debarment described in regulation include failure to pay or provide the required wages, benefits, or working conditions; intimidation, threats, coercion, or blacklisting of workers who file complaints; failing to pay civil money penalties or back wages; or committing a single heinous act showing such flagrant disregard for the law that future compliance with program requirements cannot reasonably be expected. Source: 20 C.F.R. 655.135, 655.182; 29 C.F.R. 501.20(d). | GAO‑25‑106389 |

Since we last reported on the H-2A visa program, DOL has taken steps to ensure the effectiveness of its actions to prevent debarred employers from participating in the H-2A visa program. DOL has developed a standard operating procedure for cross-referencing debarments with DHS data, among other things.[87] Further, in April 2024, DOL issued a final rule intended to enhance the Department’s capabilities to take necessary enforcement actions and ensure that debarred entities do not circumvent the effects of debarment.[88] As of August 2024, the rule is subject to litigation in federal court and under a preliminary injunction.[89]

Additionally, DOL has asked Congress to extend a 2-year statute of limitations for debarring an H-2A employer.[90] According to WHD officials, WHD has 2 years from the last known date the violation occurred to notify an employer of the agency’s intent to debar the employer, if appropriate. However, agency officials said they can face challenges providing this notice of intent within the 2-year period when employers do not provide timely information or when violations are reported long after they occurred. Consequently, the 2-year statute of limitations can impede WHD’s ability to debar a violating employer. In a 2022 report, DOL recommended that Congress extend the statute of limitations on debarment to help increase the protection of worker rights under the H-2A visa program.[91]

DOL Is Taking Steps to Help Workers Understand and Assert Their Rights Under the H-2A Visa Program

DOL has reported that the H-2A visa program lacks sufficient protections for workers to assert their rights, and the agency is taking steps to help workers understand and assert those rights. As we previously mentioned, DOL officials reported that H-2A workers are reluctant to file complaints, and our analysis found that a small portion (15 percent) of DOL’s investigations stemmed from complaints in the 6-year period we reviewed. However, our analysis also indicates that complaint-based investigations are an effective way to identify violations. The average investigation arising from a complaint finds 38 violations compared to the 22 violations found in agency-directed investigations, according to our analysis of DOL data from FY 2018 through FY 2023. DOL’s efforts to address challenges H-2A workers face in reporting violations include addressing barriers to filing complaints—by mitigating workers’ disincentives to filing complaints and their difficulties using an online contact form—and educating workers on their rights through community outreach and collaboration with foreign governments.

DOL Efforts to Mitigate Disincentives to Workers Filing Complaints

DOL is involved in several efforts that seek to mitigate disincentives that workers face when filing or considering whether to file a complaint. Workers continue to face the same disincentives to filing complaints that we identified in our 2015 report—including risk of deportation due to workers’ visas being tied to their employers, fear of retaliation and blacklisting, and high rates of debt from illegal recruitment fees.[92] DOL has also cited research that shows H-2A workers are unlikely to complain because they fear retaliation and may risk losing their visas along with their jobs.[93] In interviews with agency officials, researchers, and worker organizations, we heard that these issues persist (see text box). DOL has instituted antiretaliation and foreign recruitment transparency measures for the H-2A visa program, collaborated with other agencies to protect H-2A workers’ rights, issued guidance on fair recruitment practices of foreign workers, and updated its online contact form.

|

Disincentives Faced by H-2A Workers in Reporting Violations of Their Rights In interviews with five worker organizations, five researchers, and agency officials, we heard about the following disincentives H-2A workers face in reporting violations of their rights: · Workers’ visas being tied to their employers. Representatives from four worker organizations said workers do not file complaints because their legal status is tied to their employer. Workers who file complaints may risk deportation, according to three researchers we interviewed. Department of State officials told us that workers may not report illegal recruitment fees because they would lose their H-2A visas if State found the employer violated program rules. · Retaliation and blacklisting. Representatives from all five worker organizations we interviewed told us workers are reluctant to file complaints because they fear they would be blacklisted or not invited back for future work. · Debt from illegal recruitment fees. Representatives from all five worker organizations said that some H-2A employers or recruiters charge illegal recruitment fees, and representatives from four of the organizations said that workers may take on debt to pay these fees. A representative from one of the organizations said that workers do not complain because they would be unable to pay their debts if they lost their jobs. |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑106389

Antiretaliation and transparency measures. In April 2024, DOL issued a final rule seeking to protect H-2A workers from retaliation and to enhance the transparency of H-2A worker recruitment.[94] According to DOL, the rule aims to protect workers against unjust termination—including retaliatory termination—by clarifying the circumstances in which workers can be terminated for cause. It also expands and clarifies the range of activities that are protected by antiretaliation provisions, such as labor organizing. Additionally, to help DOL enforce the prohibition against recruitment fees, it requires employers to disclose information about all agents and recruiters used to recruit workers.[95]

Cross-agency collaboration. As a member agency of the H-2B Worker Protection Taskforce, DOL collaborates with other agencies to develop action plans that may address some of the disincentives H-2A workers face when filing complaints. Where feasible, the taskforce’s actions are expected to cover H-2A as well as H-2B workers. For example, the taskforce reported that the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) will work with foreign governments to identify recruiting misconduct—such as charging recruitment fees—by surveying workers. As mentioned in our 2015 report, debt bondage from recruitment fees may serve as a disincentive to reporting abuse.[96] In addition, the taskforce has created the Interagency H-2 Worker Protection Working Group to explore extending its actions to the H-2A visa program. [97] The Working Group reported that USAID worked with DOL, worker and migrant advocacy organizations, and the national Ministries in Northern Central America to improve the “Know Your Rights” materials provided to H-2 visa holders both before travel to the U.S. and while they are in the U.S.

Recruiting guidance. In June 2022, DOL, along with State and USAID, issued the nonbinding “Guidance on Fair Recruitment Practices for Temporary Migrant Workers,” which addresses how to identify, mitigate, respond to, and prevent abuses in the H-2 worker recruitment process.[98] The guidance aims to promote best practices among foreign governments, recruiters, and employers in the recruitment of H-2 workers under the H-2A and H-2B visa programs. Specifically, the document promotes best practices for H-2 employers to prohibit recruitment fees in contracts and for foreign governments to take measures to prevent recruiters from charging such fees, which may leave workers in debt.

Planned updates to WHD’s online contact form. WHD plans to update its online contact form in FY 2025 with changes that address some of the difficulties workers face when using the form to alert WHD of a potential violation. There are several ways for workers to alert WHD of potential violations: by calling WHD’s National Contact Center (1-866-487-9243), by visiting a local WHD office, or by submitting an online contact form. Submitting the online contact form does not formally initiate a complaint; however, after a worker completes the online contact form, a WHD representative calls the worker by phone to record the complaint. Although the online contact form is currently only available in English, WHD officials told us that the updated contact form will be translated into Spanish—the national language of most H-2A workers. The planned update will also eliminate the current form’s requirement for workers to submit information such as their zip code, which some workers may not have, according to two researchers we interviewed.

DOL Community Outreach and Collaboration with Foreign Governments and Agencies

DOL educates H-2A workers on their rights through community outreach and collaboration with foreign governments. Workers who are unaware of their rights are unlikely to file complaints, according to DOL officials and representatives from a worker organization we interviewed. Representatives from five employer organizations we interviewed said employers provide workers with information about their rights in their contracts, on workers’ rights posters, or through trainings; however, a representative from one employer organization also stated that educating workers on their rights is left to the employers’ discretion. To educate workers on their rights, DOL’s WHD organizes community outreach and implements several outreach strategies and media campaigns. DOL also collaborates with foreign governments and agencies to educate workers about their rights. In addition, DOL updated the H-2A visa program regulations to make it easier for service providers to educate workers at employer-provided housing.

Community outreach and media campaigns. To educate workers on their rights and employers on their responsibilities, WHD’s community outreach specialists organize and facilitate outreach within local communities. According to our analysis of DOL data, WHD concluded 2,419 community outreach events related to the H-2A visa program from FY 2018 through FY 2023, including 725 stakeholder meetings, 489 presentations, 167 webinars, 73 compliance consultations, and 65 media engagements.[99] WHD targets specific audiences in its outreach activities, including employers, employer associations, workers, advocacy groups, state government agencies, and community-based organizations, among other groups.

In FY 2020, DOL launched the Cross-Regional Agricultural Worker Initiative, which includes outreach strategies, such as holding regular meetings with stakeholders, collaborating with stakeholders to distribute materials on workers’ rights, and training FLCs and H-2A agents on program requirements.[100] The initiative also includes media campaigns, which incorporate press releases, radio, video, and social media. For example, one campaign highlights worker stories to mitigate the fear of filing complaints.[101]