FEDERAL RESEARCH CENTERS

DHS Actions Could Reduce the Potential for Unnecessary Overlap among Its R&D Projects

Report to Congressional Requesters

October 2024

GAO-25-106394

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106394. For more information, contact Tina Won Sherman at (202) 512-8461 or shermant@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106394, a report to congressional requesters

October 2024

FEDERAL RESEARCH CENTERS

DHS Actions Could Reduce the Potential for Unnecessary Overlap among Its R&D Projects

Why GAO Did This Study

DHS uses FFRDCs—not-for-profit organizations—to meet special, long-term R&D needs that its components and other contractors cannot meet as effectively. Since DHS established its first FFRDC in 2004, as statutorily required, the department has obligated over $3 billion through fiscal year 2023 on FFRDC contracts. According to DHS, FFRDCs are to provide independent and objective advice on critical homeland security issues.

GAO was asked to review the oversight of FFRDCs. This report addresses, among other issues, the extent to which (1) S&T has reviewed DHS’s proposed FFRDC projects for potential unnecessary overlap with other DHS R&D activities and (2) FFRDC PMO has developed tools to assess FFRDCs’ performance and receives, analyzes, and shares key performance information.

GAO reviewed DHS and S&T policies and procedures. GAO also selected a sample of 118 out of 732 FFRDC task orders—orders for services placed against established contracts—over a 9-year period to reflect a range in value and volume. GAO also interviewed officials from S&T, FFRDC PMO, selected DHS components, and the FFRDCs.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making eight recommendations, including that DHS (1) amend policies to require S&T to review FFRDC projects for potential overlap with DHS R&D activities and (2) ensure FFRDC PMO analyzes the risk of low response rates for FFRDC user surveys. DHS concurred with all eight recommendations and identified planned actions to address them.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) is responsible for coordinating and overseeing the department’s research and development (R&D) activities and, with selected DHS components, funding these activities. To help meet its R&D needs, DHS sponsors Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs), two of which are overseen by S&T’s FFRDC Program Management Office (PMO).

S&T has a coordination process that includes steps for reviewing proposed R&D projects with DHS component-funded R&D projects that S&T funds, oversees, or otherwise supports. S&T officials told GAO that they review proposed FFRDC projects for unnecessary overlap as part of this coordination process. However, GAO’s review of DHS and S&T policies found that the five DHS components that receive R&D appropriations are not required to share their component-funded R&D activities with S&T. Thus, S&T’s overall coordination reviews may not always include these DHS component-funded R&D activities. A leading practice from prior GAO work states that establishing a means to operate across agency boundaries can reduce or better manage program overlap. S&T could reduce the potential for conducting similar R&D work by amending its policies to require that officials review proposed FFRDC projects for unnecessary overlap with DHS component-funded R&D projects.

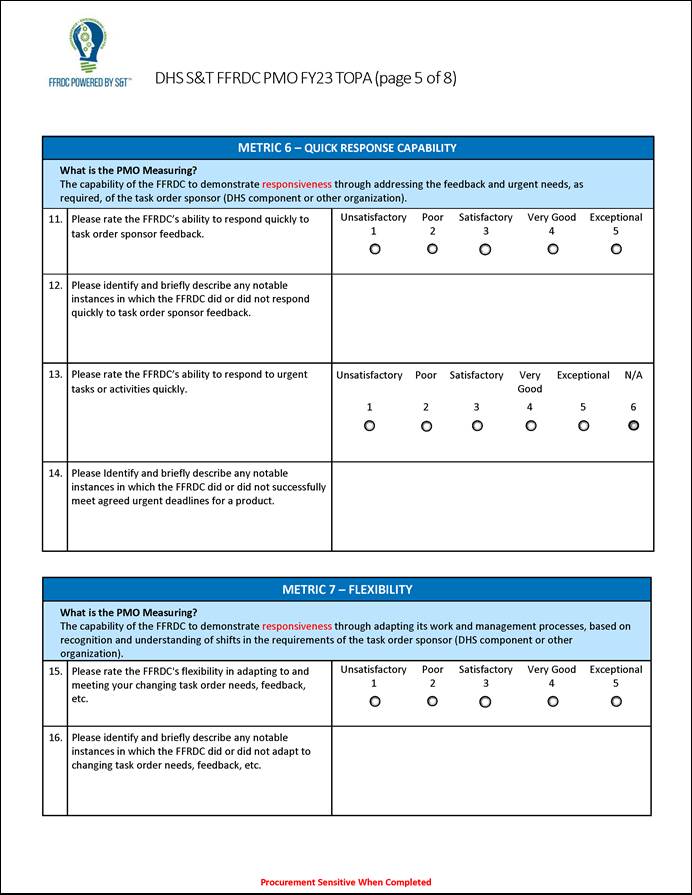

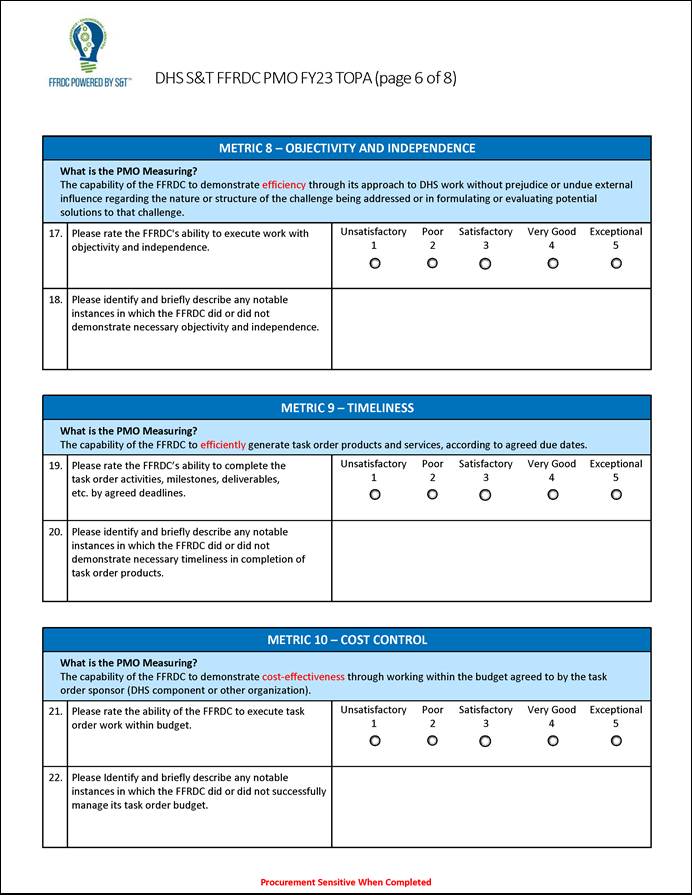

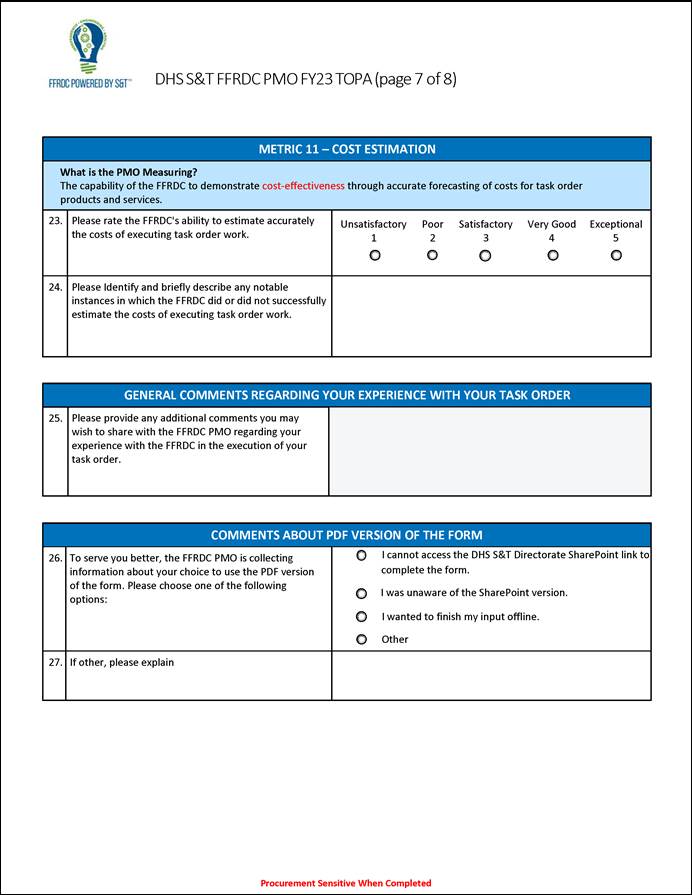

FFRDC PMO is responsible for assessing the performance of the two FFRDCs it oversees. Federal requirements and DHS guidance require FFRDC PMO officials to assess FFRDC performance each year and more comprehensively every 5 years. FFRDC PMO has developed two tools—a performance framework that identifies 11 performance metrics and a FFRDC user feedback survey—to assess FFRDC performance.

Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Federally Funded Research and Development Center Performance Assessment Process

GAO found that FFRDC PMO’s response rates for FFRDC user feedback surveys ranged in recent years from 100 percent to 43 percent across the two FFRDCs. FFRDC PMO officials said they have not analyzed the extent to which these variations in response rates could have impacted the validity of the overall survey data. Low response rates raise the risk that the survey responses do not represent the views of all FFRDC users. If the views of the users who did not respond to the survey differ from those who did, the survey results could produce a different outcome than what would be found across all users. Given the importance of the surveys in assessing FFRDC performance, analyzing the risk of low response rates could help FFRDC PMO identify whether further steps, such as increasing such rates, are needed to mitigate the risk of those responses not representing all users.

Abbreviations

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FFRDC |

Federally Funded Research and Development Center |

|

FY |

Fiscal Year |

|

HSOAC |

Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center |

|

HSSEDI |

Homeland Security Systems

Engineering and |

|

PMO |

Program Management Office |

|

R&D |

Research and Development |

|

S&T |

Science and Technology Directorate |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 30, 2024

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Anthony P. D’Esposito

Chair

Subcommittee on Emergency Management and Technology

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) uses Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDC) to meet special, long-term research and development (R&D) needs that DHS and other contractors cannot meet as effectively.[1] Since DHS established the first FFRDC in 2004, as statutorily required, the department has obligated over $3 billion through fiscal year 2023 on contracts for DHS FFRDCs to research issues and technologies that affect homeland security.[2] According to DHS, the purpose of its FFRDCs is to provide the department with independent and objective advice on critical homeland security issues.

The Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) oversees DHS’s three FFRDCs. Within S&T, the FFRDC Program Management Office (PMO) oversees, manages, and supports operations for two of DHS’s three FFRDCs—the Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center (HSOAC) and the Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute (HSSEDI).[3] S&T sponsors the FFRDCs through contracts with entities—such as not-for-profit organizations—that operate the FFRDCs. Combined, HSOAC and HSSEDI specialize in 16 areas, including homeland security threat and opportunity studies, emerging threats, innovation and technology, cyber solutions, and systems engineering.[4]

· HSOAC. HSOAC supports DHS through its operational analyses and acquisition and organizational studies. RAND, a not-for-profit research organization that conducts R&D work across multiple fields and industries, has operated HSOAC since its inception in 2016.[5] In 2022, the DHS Office of Procurement Operations awarded RAND a $495 million, 5-year contract on a sole-source (non-competitive) basis to continue to operate HSOAC into 2027.[6]

· HSSEDI. HSSEDI provides technical and systems engineering expertise to DHS. The MITRE Corporation (MITRE), a not-for-profit research organization that supports federal government operations in areas such as defense and cybersecurity, has operated HSSEDI since its launch in 2009.[7] In 2020, the DHS Office of Procurement Operations awarded MITRE an $862 million, 5-year contract on a sole-source basis to continue to operate HSSEDI into 2025.[8] In March 2023, the contract ceiling was increased to $1.42 billion. For more information on HSOAC and HSSEDI, see appendices I and II, respectively.

You asked us to review the extent to which FFRDC PMO engages in various oversight activities for HSOAC and HSSEDI. This report addresses the extent to which

1. S&T has reviewed DHS’s proposed FFRDC projects for potential unnecessary overlap with other DHS R&D projects;[9]

2. S&T’s FFRDC PMO has developed tools to assess FFRDCs’ performance and receives, analyzes, and shares key work performance information;[10] and

3. S&T’s FFRDC PMO has reviewed and analyzed DHS’s use of the results of FFRDC task orders.[11]

To address all our objectives, we identified task orders issued to FFRDCs from September 2014 through February 2023. This approximately 9-year timeframe includes the ongoing and immediately preceding 5-year FFRDC contract periods of performance and allowed us to review task orders issued over time. We assessed the reliability of the data by reviewing S&T data-entry guidelines and interviewing S&T officials on internal controls for data maintenance and verification. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for identifying task orders that S&T and DHS components sponsored, and other key task order information.

To better understand S&T’s FFRDC R&D project implementation processes, we reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 118 out of 732 FFRDC task orders issued within the approximately 9-year timeframe. The 118 task orders were issued on behalf of S&T and three DHS components.[12] We selected the components and task orders to reflect a range of the (1) value of issued task orders, (2) number of issued task orders by component, and (3) timeframes for which the task orders were issued (period of performance). We analyzed key documents, such as FFRDC PMO’s appropriateness certificate, for each task order and interviewed 17 S&T and DHS component program managers across the 118 task orders about their experiences overseeing the task orders.[13] We selected these managers to reflect a range of number of task orders they oversaw and value of the projects placed on the task orders.

To determine the extent to which S&T reviews proposed FFRDC projects for potential unnecessary overlap with other DHS R&D projects, we analyzed DHS and S&T management directives and guidelines for coordinating DHS-wide R&D needs and projects. We evaluated DHS’s R&D coordination procedures against our fragmentation, overlap, and duplication guidance for coordinating agency actions, selected leading practices for interagency collaboration, and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[14] We analyzed a set of five key documents, such as the Technical Execution Plan, for each of the 118 selected task orders, for indications that S&T, FFRDC PMO, FFRDC, or DHS component officials had reviewed FFRDC task orders for potential overlap with other DHS R&D activities.[15] We interviewed S&T, FFRDC PMO, FFRDC, and DHS component officials regarding their actions to identify and mitigate potential FFRDC project overlap.

To determine the extent to which FFRDC PMO has developed tools to assess FFRDCs’ performance and receives, analyzes, and shares key work performance information, we reviewed relevant federal requirements for assessing FFRDC performance as well as DHS management directives on establishing and contracting with FFRDCs.[16] We analyzed the most recent 5-year Comprehensive Review for each FFRDC. We also analyzed five Annual Assessments, for fiscal year 2020, fiscal year 2021, and fiscal year 2022 for HSSEDI and fiscal year 2021 and fiscal year 2022 for HSOAC, to determine the extent to which they were consistent with federal and DHS guidance and key practices for evidence-based policymaking that we identified in our 2023 work.[17] We also interviewed FFRDC PMO officials regarding their procedures for assessing FFRDC performance and RAND and MITRE officials regarding their assessment experiences.

To understand how FFRDC PMO receives and analyzes feedback on FFRDC performance, we analyzed FFRDC PMO’s data used to determine user feedback survey response rates from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation and interviewed responsible officials. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable to report on survey response rates over these fiscal years. We also interviewed FFRDC PMO officials regarding their procedures for collecting, assessing the quality of, and analyzing user feedback survey data. We assessed the extent to which FFRDC PMO’s processes for collecting, validating, and analyzing user feedback data were consistent with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and key practices for evidence-based policymaking.[18]

To address the extent to which FFRDC PMO has reviewed and analyzed DHS’s use of the results of FFRDC task orders, we reviewed DHS and S&T policies and procedures for contracting with FFRDCs.[19] We examined key documents, such as completed user feedback surveys, from the 118 selected FFRDC task orders to identify FFRDC PMO efforts to track S&T’s and DHS components’ use of task order results and interviewed FFRDC PMO officials about their outreach practices, as well as the 17 selected S&T and DHS component program managers and FFRDC officials. We also assessed the extent to which FFRDC PMO’s outreach efforts were consistent with key practices for evidence-based policymaking.[20] For additional information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix III.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2022 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DHS FFRDC Function and Oversight

FFRDCs are designed in part to meet departments’ special long-term R&D needs by allowing them to use non-government resources to accomplish tasks that are integral to their mission and operation. According to DHS guidance, FFRDCs provide the department with independent and objective advice to address critical homeland security issues.

In addition to overseeing the FFRDCs, S&T’s FFRDC PMO also acts as a liaison between the FFRDCs and the FFRDC task order sponsors.[21] FFRDC PMO is responsible for key FFRDC operations, including contract administration and management, business operations and knowledge management, and customer relationship management.

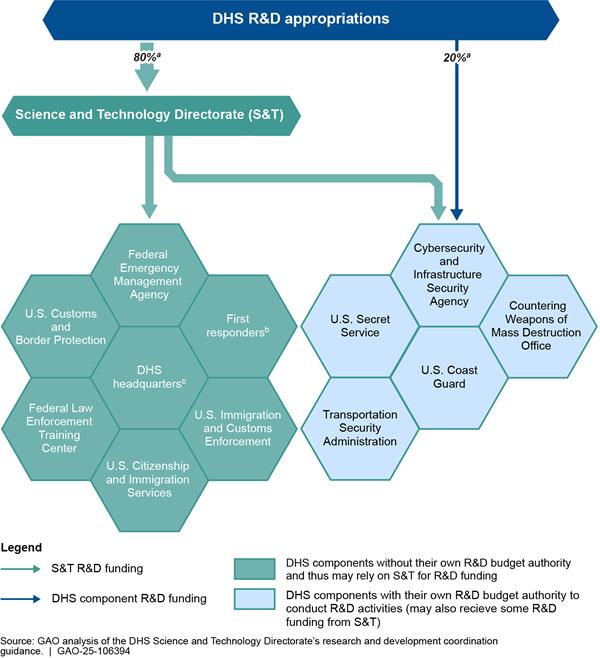

S&T’s Processes for Coordinating DHS R&D Activities

As the primary R&D arm of DHS, S&T is responsible for providing DHS components with R&D support and coordination. According to S&T officials, S&T is responsible for developing, coordinating, and tracking R&D projects it either funds with its own R&D appropriations or which it directly supports, such as by providing management or needed technical expertise. S&T officials stated that approximately 80 percent of all DHS R&D activities are funded with S&T R&D appropriations, while the remaining approximately 20 percent are R&D activities that DHS components fund with their own R&D budget authority and develop through their own project development processes.[22] We found in our prior work that, because selected DHS components can use their own R&D funds in addition to S&T’s funds to conduct R&D projects, R&D activities at DHS are inherently fragmented.[23]

According to S&T guidance, to meet its DHS R&D coordination responsibilities, S&T has developed a R&D coordination process comprised of multiple steps. Two of these steps include procedures for identifying potential R&D project overlap: (1) identifying and prioritizing DHS mission needs (called “capability gaps”) and (2) determining how to address those needs.[24] According to S&T officials, S&T’s coordination process applies only to the DHS components’ R&D needs and projects that S&T funds, oversees, or otherwise supports. That is, S&T’s coordination process does not apply to the approximately 20 percent of DHS R&D activities that certain DHS components fund with their own R&D appropriations.[25]

S&T’s first relevant step for identifying potential project overlap is to identify and prioritize DHS R&D needs. This step is carried out by S&T’s Integrated Product Teams, which are organized by DHS component and are generally comprised of S&T and component senior officials. The Integrated Product Teams also are to coordinate each DHS component’s prioritized R&D needs with those of other DHS components to identify overlapping needs and projects. If, based on the work of the Integrated Product Teams, S&T officials identify overlapping DHS component needs or projects, S&T’s R&D coordination guidance instructs them to bring these components together to explore options to mitigate unnecessary overlap.

S&T’s second relevant step is to evaluate options for addressing the R&D needs the Integrated Product Teams identified in the first step. During this phase, various S&T subject matter experts are to review proposed R&D projects for overlap with other ongoing or planned R&D efforts across DHS.

Funding R&D Projects

According to S&T officials, DHS components may use a variety of funding sources to fund R&D projects, including those with the FFRDCs and other vendors or research institutions, as shown in figure 1.[26]

S&T R&D funding. S&T provides funds for R&D activities, including FFRDC projects, to DHS components. It coordinates these activities through its R&D coordination process.

DHS component R&D funding. As of May 2024, five DHS components have their own R&D budget authority—a specific appropriation for R&D activities—to conduct R&D activities separately from S&T efforts. These DHS components use these funds to identify their own R&D needs and to fund R&D processes and projects, including FFRDC projects and those with other research institutions, in support of their respective missions. See figure 1.

Note: Funding can be used for R&D activities conducted by FFRDCs as well as for other DHS R&D activities.

aAccording to S&T officials, approximately 80 percent of all DHS R&D funding goes through S&T, with the remaining 20 percent going directly to DHS components with their own R&D project development processes. Using its R&D appropriations, S&T may also fund some projects for the DHS components that have their own R&D project development processes and funding.

bS&T determines the R&D needs and projects for the first responder community at the federal, state, and local levels.

c”DHS headquarters” in this context refers to any DHS headquarters entity, such as the Office of Policy, that may have a R&D need.

Other available DHS component funding. According to S&T officials, DHS components may also use other available component funds to finance FFRDC projects or other R&D projects performed by other vendors or research institutions.[27] This includes both DHS components that have their own specific R&D budget authority and those that do not.

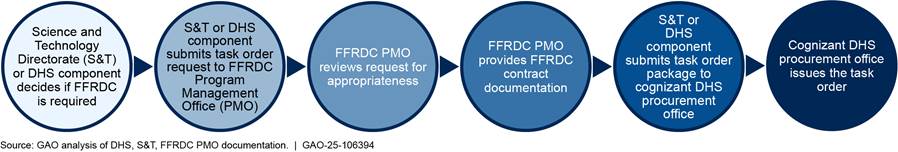

FFRDC Task Order Issuance Process, Implementation, and Closure

S&T’s FFRDC PMO is responsible for determining the appropriateness of proposed task orders for FFRDC development. As part of the process for issuing task orders, DHS procedures require S&T and DHS component sponsors to submit a task order proposal to FFRDC PMO officials for an “appropriateness” review to ensure the proposal meets specific FFRDC requirements.[28] FFRDC PMO officials are to review the information S&T and DHS component sponsors submit and, if suitable, certify that the task order is appropriate for a FFRDC. See figure 2.

At the beginning of this process, DHS component sponsors assign a contracting

officer and contracting officer’s representative to ensure contract

requirements are met and a program manager to oversee the development of the

task order and liaise with the FFRDC.[29]

After the appropriateness review, the assigned program manager submits a procurement request package to the cognizant procurement office for issuance.[30] S&T or the DHS component sponsor is responsible for funding the task order.

The FFRDC provides “deliverables” to the S&T or DHS component sponsor, as identified in the task order. Deliverables may include reports, data, assessments, analysis, and many other types of products.

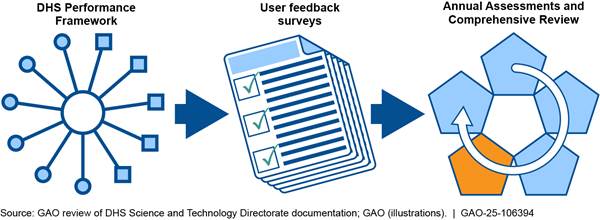

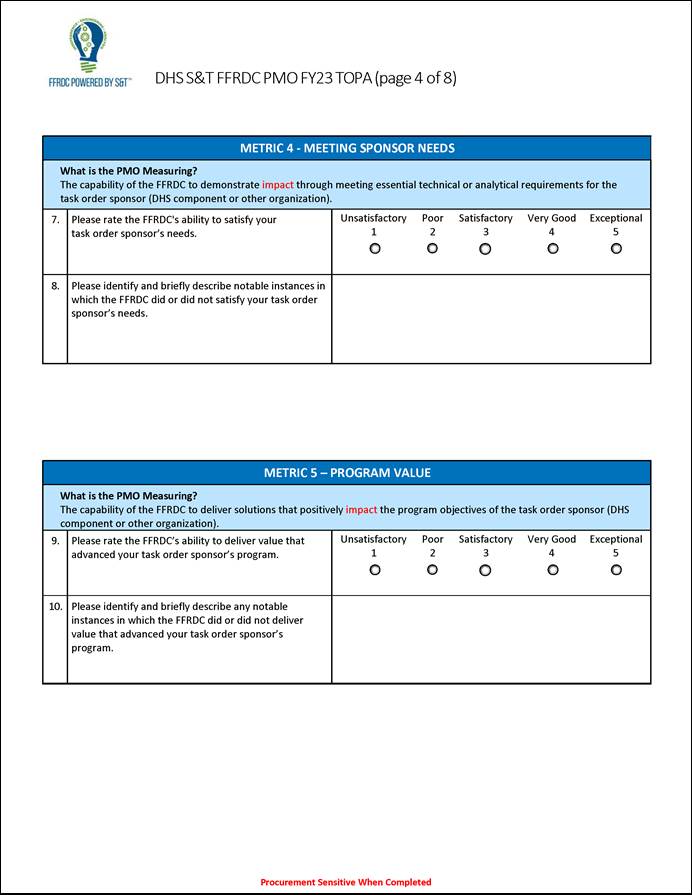

DHS Requirements for Assessing FFRDC Work Performance

FFRDC PMO, on behalf of the Under Secretary for Science and Technology, is also responsible for assessing FFRDC performance.[31] The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and DHS guidance require FFRDC PMO officials to conduct Comprehensive Reviews every 5 years; DHS guidance also requires FFRDC PMO officials to conduct Annual Assessments.[32]

· Comprehensive Reviews. FFRDC PMO officials are to conduct a Comprehensive Review of FFRDC performance every 5 years, corresponding with the FFRDC contract period, to include metrics that measure the efficiency and effectiveness of FFRDC work performance.[33] The purpose of a Comprehensive Review is to analyze how well a FFRDC has met DHS’s needs during the 5-year contract period and whether DHS has a continued need for R&D that can be met by the FFRDC. The Under Secretary for Science and Technology uses the Comprehensive Review to determine whether to re-award, recompete, or terminate the department’s sponsorship of the FFRDC.[34] DHS guidance requires FFRDC PMO to include a summary of program metrics and goals, as well as user surveys of performance in the review.[35] As shown in figure 3, the Comprehensive Review takes the place of the Annual Assessment for the contract year in which it is performed.

· Annual Assessments. FFRDC PMO officials are to assess FFRDC performance annually in the areas of technical quality, responsiveness, value, cost, and timeliness, and to establish performance metrics and goals, measure progress against those goals, and document the results in a report. This assessment report is to include S&T or DHS component sponsors’ perspectives on FFRDC performance, which FFRDC PMO officials are to gather through a user feedback survey.

Note: The Comprehensive Review is completed in year 4 of the 5-year contract. This is to allow the time necessary should DHS need to recompete or terminate the contract before it expires.

S&T’s Process for Reviewing Proposed FFRDC Projects for Potential Unnecessary Overlap May Not Include All DHS R&D Projects

S&T’s R&D Coordination Process Includes Review of Proposed FFRDC Projects for Potential Overlap

S&T’s R&D coordination process includes steps for reviewing proposed R&D projects—including FFRDC projects—for potential unnecessary overlap with other DHS R&D projects. S&T officials told us that they review potential FFRDC projects for overlap with other DHS R&D projects as part of S&T’s ongoing efforts to coordinate DHS R&D activities that S&T funds, oversees, or otherwise supports.

S&T officials told us they use steps in the coordination process, such as through the Integrated Product Teams, to identify and coordinate DHS components’ R&D needs and projects, which S&T funds or otherwise supports.[36] S&T guidance requires officials to document key decision points in the S&T coordination process. We reviewed examples of S&T’s documentation of key steps in the coordination process for non-FFRDC R&D projects.[37]

S&T’s Coordination Process May Not Include All DHS R&D Projects

S&T officials who oversee the R&D coordination process with DHS components told us that the five DHS components that receive R&D appropriations are not required to share their component-funded R&D activities with S&T as part of S&T’s R&D coordination process. For this reason, the FFRDC project reviews that S&T officials told us they conduct to identify potentially unnecessary overlap may not always include DHS component-funded R&D activities.

S&T officials responsible for reviewing R&D activities as part of the coordination process—including reviews for potential overlap—told us they have concerns about obtaining needed information on the R&D activities that the five DHS components self-fund and develop. Specifically, five of the nine S&T portfolio managers who lead the Integrated Product Teams told us that although the five DHS components usually share information on their self-funded R&D activities with S&T, they may not always do so. These S&T officials said they are not always made aware—through the Integrated Product Teams—of FFRDC or other R&D projects initiated by these five DHS components. Five of the nine portfolio managers also told us that obtaining information on DHS component-funded R&D projects would be helpful to them in assessing whether the projects potentially overlap with other DHS R&D projects.

According to S&T officials, in the event they are not made aware of DHS component-funded R&D efforts through S&T’s coordination processes, it is possible to identify those efforts through an annual report of DHS R&D activities that S&T compiles each year. S&T officials told us that each fiscal year, in response to a statutory requirement, they reach out to DHS components to compile a list of all DHS R&D projects that were funded through DHS R&D budget authority, including DHS component R&D appropriations.[38] The list includes R&D projects that were ongoing, completed, or terminated during the prior fiscal year, including DHS component-funded projects. According to S&T officials, they use the list to develop the statutorily required DHS annual R&D report, which also provides FFRDC PMO and DHS components with a complete list of DHS R&D activities that they can review for potentially overlapping R&D activities.

However, the DHS annual report on R&D activities may not provide sufficient information to fully identify unnecessary overlap between FFRDC and DHS R&D projects for two reasons: (1) the time lag in updating the list and (2) its potential omission of some projects based on the funding source.

Time lag in updating the annual DHS R&D list. Because S&T officials update and provide the list to Congress annually, there can be a significant lag in identifying newly initiated DHS R&D activities through the DHS annual report, including FFRDC projects. For example, DHS issued its fiscal year 2022 report in early July 2023, approximately 9 months after the end of the fiscal year. For R&D projects initiated earlier in fiscal year 2022, the lag time for stakeholders to learn about these projects would be greater. While the annual list of DHS R&D projects could be useful to FFRDC PMO and DHS components as an additional way to identify potential project overlap, DHS components could initiate new R&D projects after S&T compiles the annual list. Therefore, FFRDC PMO and DHS components would not see these new projects until S&T updates the list the next year.

Consequently, using the annual list to identify overlapping projects would mean missing potentially relevant projects that DHS initiates after the annual list was updated. In addition, S&T portfolio managers told us that receiving timely information on proposed FFRDC projects before the task order is issued would be helpful in assessing whether any of these projects potentially overlap with other DHS R&D activities.

Potential impact of funding source on completeness of the annual R&D list. In addition, since the list includes projects funded from R&D appropriations, the annual list may not capture some R&D projects that DHS components finance with funds that are not from a specific R&D appropriation, which, according to S&T officials, could include FFRDC projects.[39]

While S&T develops and publishes this list annually, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 requires DHS to develop and update the list of R&D projects on at least a quarterly basis.[40] S&T officials told us that while they update the results of certain completed projects each quarter, they do not update all the projects due to their view that this information would be of limited usefulness during the course of the year.[41] Further, S&T officials told us that they do not distribute the quarterly updates of certain projects internally to DHS components. Instead, they said they used them to update the annual list in anticipation of the report to Congress.

Updating the annual list of R&D projects on at least a quarterly basis, as required by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, and disseminating the updated list to relevant DHS entities, including DHS components, would provide DHS with a more updated and useful resource with which to review proposed FFRDC projects for potentially unnecessary overlap.

According to our guidance on fragmentation, overlap, and duplication, agencies that establish a means to operate across agency boundaries can reduce or better manage program overlap.[42] Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that effective and efficient operations minimize waste.[43]

DHS and S&T policies and procedures require S&T officials to review proposed FFRDC projects for potential unnecessary overlap through their R&D coordination process. However, this process may not include all R&D projects that DHS components develop with their own R&D appropriations. S&T officials stated that this is because, as part of S&T’s coordination process, DHS and S&T policies and procedures do not require the five DHS components to share their component-funded R&D activities with S&T.

By amending its policies and procedures to require S&T officials to review proposed FFRDC projects for unnecessary overlap with DHS component-funded R&D projects, S&T could better avoid the potential for expending DHS resources for similar R&D projects.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, an agency’s significant events should be fully documented.[44] Documenting the results of the R&D coordination efforts between the proposed FFRDC task orders and the R&D activities funded by the five DHS components could better ensure that the overlap reviews take place and informs all relevant parties that the overlap reviews have been conducted.

FFRDC PMO Has Tools to Assess FFRDC Performance but May Not Receive, Analyze, or Share Key Information

FFRDC PMO Has Developed and Implemented Tools to Assess Performance, Including a Framework and User Feedback Survey

FFRDC PMO officials have developed and implemented two tools—the FFRDC PMO Performance Framework (Performance Framework) and a user feedback survey—to meet the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) requirements and DHS guidance on assessing FFRDC work performance and to ensure consistency across assessments.[45] In combination, these two tools serve as the foundation for FFRDC PMO officials’ performance assessments of FFRDCs, as shown in figure 4.

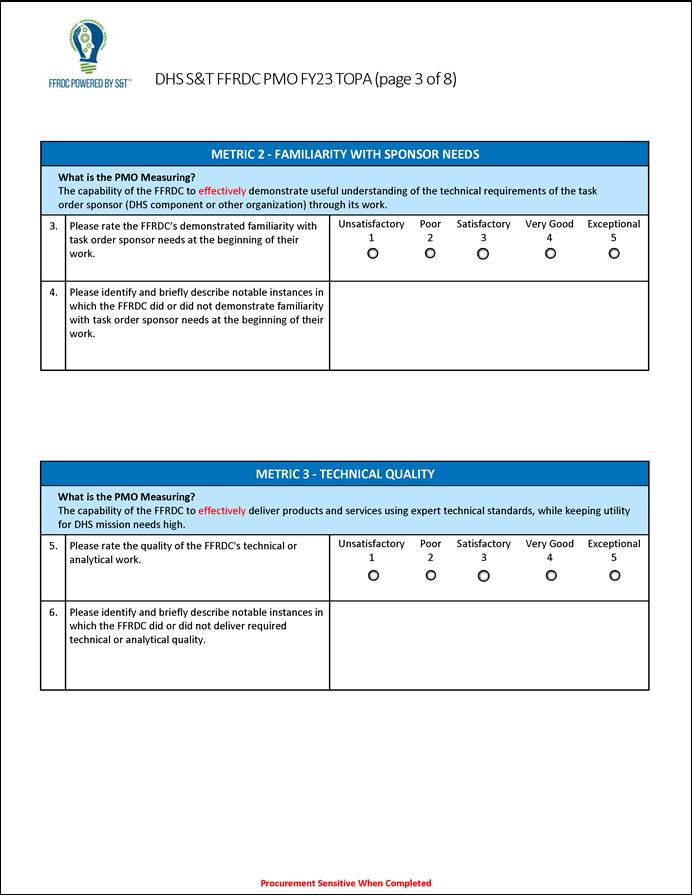

The Performance Framework organizes FFRDC assessment criteria, which the FAR and DHS guidance require as part of the Comprehensive Reviews and Annual Assessments.[46] As shown in table 1, FFRDC PMO officials have defined 11 performance metrics based on FAR and DHS guidance and distilled them into five performance categories. These five performance categories comprise two broad performance areas: (1) technical value and (2) quality process.

|

Performance area |

Performance |

Performance metrics from Federal Acquisition Regulation |

Performance metrics from DHS Directives System Instructions |

|

Technical Value |

Effectiveness |

Current in its fields of expertise |

Technical quality |

|

Familiarity with sponsors’ needs |

|

||

|

Impact |

Meeting sponsor’s needs |

Program value |

|

|

Quality Process |

Responsiveness |

Quick response capability |

Flexibility |

|

Efficiency |

Objectivity and independence |

Timeliness |

|

|

Cost effectiveness |

Cost control |

Cost estimation |

Source: DHS Science and Technology Directorate, FFRDC PMO. | GAO‑25‑106394

To collect information about how the FFRDCs are performing in the areas outlined in the Performance Framework, FFRDC PMO officials have also developed a user feedback survey. According to FFRDC PMO officials, the intention of this survey is to offer S&T and DHS component sponsors—FFRDC users—a direct mechanism to submit comprehensive, structured, and detailed feedback to FFRDC PMO at the conclusion of a task order.[47] FFRDC PMO officials stated that due to their varying involvement in the day-to-day management of task orders, the user feedback surveys provide them with necessary insight into how well the FFRDCs have performed for S&T and DHS component sponsors across the department. As such, FFRDC PMO officials told us they consider the surveys a critical resource for their oversight and management of FFRDCs.

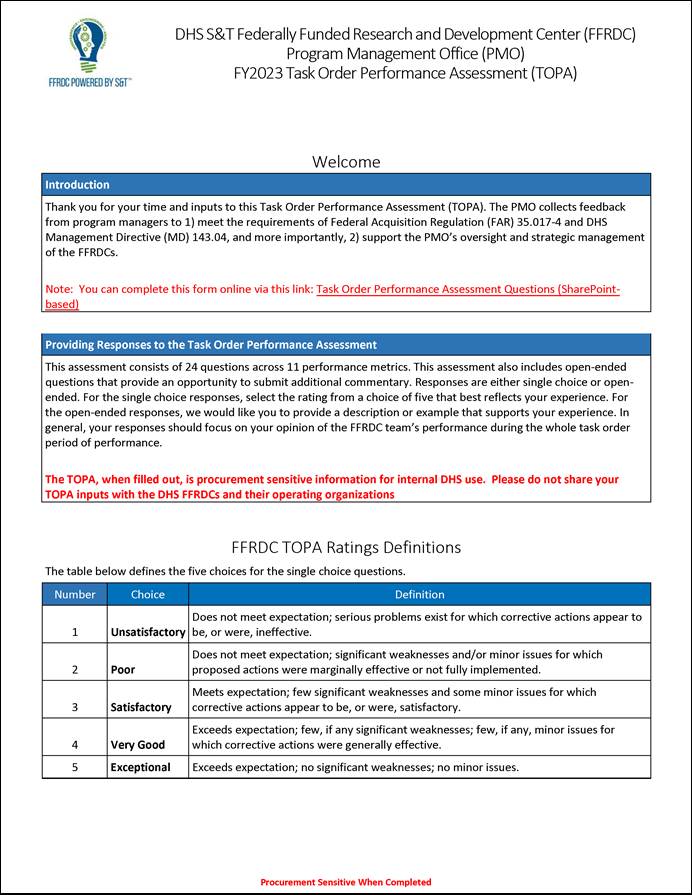

In the user feedback survey, S&T and DHS component sponsors answer questions about FFRDC performance on the 11 performance metrics defined in the Performance Framework. Specifically, the user feedback survey consists of two types of questions. First, S&T and DHS component program managers answer rating questions by selecting a score from a 5-point scale that ranges from “Unsatisfactory” to “Exceptional,” to describe FFRDC performance, as shown in table 2. Second, the survey includes open-ended questions that offer program managers the option of providing narrative feedback, such as examples, to support their rating responses. Appendix IV includes FFRDC PMO’s user feedback survey template as well as additional details on how FFRDC PMO uses the rating data to determine whether the FFRDCs meet performance standards.

|

Scoring number |

Rating |

Definition |

|

1 |

Unsatisfactory |

Does not meet expectations; serious problems exist for which corrections appear to be, or were, ineffective. |

|

2 |

Poor |

Does not meet expectation; significant weaknesses or minor issues for which proposed actions were marginally effective or not fully implemented. |

|

3 |

Satisfactory |

Meets expectations; few significant weaknesses and some minor issues for which corrective actions appear to be, or were, satisfactory. |

|

4 |

Very good |

Exceeds expectations; few, if any significant weaknesses; few, if any, minor issues for which corrective actions were generally effective. |

|

5 |

Exceptional |

Exceeds expectations; no significant weaknesses; no minor issues. |

Source: DHS Science and Technology Directorate, FFRDC Program Management Office. | GAO‑25‑106394

FFRDC PMO Lacks Understanding of Potential Risks Posed by Incomplete Survey Information

FFRDC PMO does not have an understanding of potential risks to the quality of its user feedback data due to variation in response rates. Our analysis of FFRDC PMO’s response rate data for completed user feedback surveys found that response rates varied when comparing across recent fiscal years and FFRDCs. FFRDC PMO officials told us that they have not analyzed the extent to which these variations in response rates could have impacted the validity of the overall survey data.

Specifically, our analysis found that response rates for user feedback surveys for HSSEDI ranged from 83 percent in fiscal year 2021 to 46 percent in fiscal year 2023, and response rates for HSOAC ranged from 100 percent in fiscal year 2019 to 43 percent in fiscal year 2023. Lower response rates could mean survey results do not represent the views of the population—in other words, the results could be biased to underrepresent or overrepresent different aspects of the population. However, FFRDC PMO officials told us they do not conduct an analysis to understand the risk of bias in the overall results from the user feedback surveys.

We reviewed user feedback survey response rates from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023, as shown in table 3. During this period, we found S&T and DHS component program managers completed less than two-thirds of the surveys sent to them in fiscal year 2020 and fiscal year 2023 for HSSEDI, and in fiscal years 2021, 2022, and 2023 for HSOAC. S&T and DHS component response rates to the user feedback survey also varied by FFRDC. For example, in fiscal year 2021, S&T and DHS component program managers completed 83 percent of user feedback surveys for HSSEDI, but 58 percent of surveys for HSOAC. Additionally, we found that S&T and DHS component managers completed less than half of the surveys distributed in fiscal year 2023 for both HSSEDI and HSOAC projects.[48]

|

Fiscal year |

Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute |

Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center |

||||

|

Number |

Number of responses |

Response rate |

Number |

Number of responses |

Response rate |

|

|

2019 |

46 |

34 |

74% |

32 |

32 |

100% |

|

2020 |

76 |

47 |

62% |

29 |

19 |

66% |

|

2021 |

42 |

35 |

83% |

31 |

18 |

58% |

|

2022 |

58 |

44 |

76% |

27 |

17 |

63% |

|

2023a |

50 |

23 |

46% |

54 |

25 |

43% |

Source: DHS Science and Technology Directorate, FFRDC Program Management Office. | GAO‑25‑106394

aUser feedback data for fiscal year 2023 are as of February 2024.

FFRDC PMO staff told us their initial effort to prompt S&T and DHS component program managers to respond to the survey is a reminder email set up through an online system.[49] According to FFRDC PMO officials, program managers are to receive up to two reminder emails within 2 weeks of closing out the project. According to FFRDC PMO officials, after the initial email outreach effort, FFRDC PMO leadership may decide to take additional steps to encourage survey response depending on the results of the main efforts and staff availability. These additional steps include (1) FFRDC PMO staff outreach to users directly by phone, (2) FFRDC PMO director outreach to users by phone, or (3) notices to users from S&T’s Executive Secretariat Office.

FFRDC PMO officials told us they have not analyzed the risk of nonresponse bias and thus do not use it as a factor when deciding whether to take additional steps to increase survey response rates. “Nonresponse bias” can occur when survey results produce a different outcome than what would be found in the overall population, because the views of those who did not respond to the survey differ from those who did respond.

While bias can be caused by many factors, low survey response rates are of concern because they raise the risk that the responses received do not represent the views of all S&T and DHS component program managers (the overall user population). For example, a survey response rate of 40 percent means 60 percent of S&T and DHS component program managers did not respond to the survey. The 60 percent of program managers who did not respond could have different views on FFRDC performance from the 40 percent who did respond.

There are multiple ways to analyze the risk of nonresponse bias. One way is to compare the characteristics of those program managers (e.g., length of experience as a program manager) who responded or the characteristics associated with their task orders (e.g., type of work overseen or the DHS component funding the task order) to the corresponding characteristics of the overall population of the survey. In this way, an analysis of nonresponse bias can help to identify whether certain groups are missing or underrepresented from the results. Once identified, additional steps can be taken to correct the bias, such as targeting missing groups with additional follow-up.

Determining when to conduct a nonresponse bias analysis can vary based on circumstances such as the level of importance of the survey and the likelihood of a large difference between those who did and did not respond to the survey. However, the 2006 Office of Management and Budget’s Standards and Guidelines for Statistical Surveys suggests that an agency should plan to conduct analysis of nonresponse if it expects the survey response rate to be less than 80 percent.[50]

Key practices for evidence-based policymaking that we identified state that an organization should assess the quality of the evidence it uses for decision-making, which includes the completeness of the data.[51] Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that, to establish an effective internal control system, management should use quality information to achieve an entity’s objectives. Quality information requires reliable data that are reasonably free from error and bias and faithfully represent what they purport to represent. Documentation is also a necessary part of an effective internal control system.[52]

FFRDC PMO officials told us they have not conducted an analysis of risk for nonresponse bias in part due to competing higher priorities and limited staff resources. But they said that a formal analysis of risk for nonresponse bias has not been necessary given the staff’s experience-based knowledge of program managers’ behavior with respect to completing or not completing the user surveys.[53] While FFRDC PMO staff may be familiar with the reasons program managers may not have completed user surveys in the past, each assessment year can be unique in terms of risk factors and characteristics of the user population, and knowing the reasons for not responding does not necessarily help determine whether there could be bias in the overall results.

Moreover, FFRDC PMO relies solely on the user feedback data to understand FFRDC work performance in its Annual Assessment and as an input to its Comprehensive Review. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving objectives and communicate necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objective.[54]

Given the importance of the data to understanding FFRDC work performance, risks to the quality of the data may impact FFRDC PMO’s ability to fulfill its objective of assessing FFRDC performance. Therefore, conducting an analysis of the risk for nonresponse bias could help FFRDC PMO officials identify to what extent survey results may be at risk of potential bias and whether they should take actions to mitigate that risk and increase the survey response rate. Moreover, documenting the results of the user feedback surveys (response rate, risk of bias analysis, and steps taken to increase the response rate) for each fiscal year’s Annual Assessment and the Comprehensive Review would help FFRDC PMO better ensure it is transparent about relevant data in all assessments of FFRDC work performance.

FFRDC PMO Did Not Comprehensively Analyze Open-Ended Survey Responses on FFRDC Performance

To assess users’ experiences with FFRDCs, FFRDC PMO officials rely on ratings data from completed user feedback surveys; however, since fiscal year 2022, officials have not included an analysis of users’ open-ended written responses in Annual Assessments to provide context for users’ satisfaction ratings. Specifically, while satisfaction ratings can indicate when FFRDCs did not meet performance standards, they cannot tell FFRDC PMO officials the reasons why they did not meet the standards. A comprehensive analysis of the users’ responses to the open-ended survey questions, however, could explain the reasons why.

For fiscal year 2019 for HSOAC, and fiscal years 2020 and 2021 for HSSEDI, FFRDC PMO officials analyzed open-ended written responses from FFRDC user surveys to identify positive- and negative-themed comments.[55] FFRDC PMO included the broad results of this analysis in the respective FFRDC Annual Assessments, along with examples of “themed” comments.[56] Each quarter FFRDC PMO officials also drafted a presentation for discussion with FFRDC leadership of survey results for that quarter. The presentation slides provided examples of high- and low-scoring survey results, including both rating scores and open-ended written comments.

FFRDC PMO officials told us they stopped developing the positive- and negative-themed analysis of open-ended survey comments with the fiscal year 2022 Annual Assessments. They said they discontinued the analysis because the Word format they used for the Annual Assessments in fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2021 was too long and FFRDC PMO consequently decided to switch the assessment format to an executive-level summary product. As such, in fiscal year 2022, FFRDC PMO officials revised the Word Annual Assessment format into a “report card” style PowerPoint briefing. FFRDC PMO officials streamlined the survey analysis to focus solely on rating scores and revised the format from a Word report to presentation slides.

FFRDC PMO officials stated that under the revised Annual Assessment format, they generally scan the open-ended survey comments as S&T and DHS component program managers complete the surveys to identify notably high or low FFRDC performance. FFRDC PMO officials told us they will also complete a “cursory” review of the open-ended written responses to identify themes associated with low ratings data. However, FFRDC PMO officials stated they no longer conduct a comprehensive review of the open-ended responses, nor do they include the themes they identify from the cursory review in the Annual Assessments.

FFRDC PMO officials also stated that they do not perform a comprehensive analysis of the open-ended responses because they rely on other sources, such as interviews with the S&T and DHS component program managers, to inform the Annual Assessments and Comprehensive Reviews. However, our analysis of the fiscal year 2022 FFRDC Annual Assessment presentation slides found that FFRDC PMO did not include context from any source as to why FFRDCs are not fully meeting performance standards.[57] Of the three instances in which FFRDC PMO officials identified aggregated ratings for a performance metric as “partly meets FFRDC PMO standard” in the fiscal year 2022 Annual Assessments, none included an explanation of what factors may be driving those ratings.

FFRDC PMO leadership told us that they are considering instituting a “formal (i.e., regular, structured and complete) analysis” of user survey information in the future for both FFRDC Annual Assessments and the Comprehensive Reviews. This analysis might include an assessment of positive and negative themes for the open-ended survey comments or other type of content analysis, as deemed necessary. As of July 2024, FFRDC PMO officials told us they expect to establish a process for assessing users’ open-ended written comments by March 2025.

Key practices for evidence-based policymaking that we identified state that an organization should assess the quality of evidence it uses for decision-making, which includes the completeness of the evidence.[58] These key practices state that understanding the quality of the evidence is important because it impacts the credibility of the data and, ultimately, the decisions an organization makes based on those data. Performing a comprehensive analysis of the users’ open-ended survey responses may explain why user ratings fall below performance standards and therefore provide a more complete understanding of user feedback. Further, incorporating this analysis into their FFRDC Annual Assessments may help FFRDC PMO officials and FFRDC leadership identify and more accurately address issues that are broader than just one task order.

FFRDC PMO Has Not Consistently Shared Annual Assessment Results with FFRDCs

We found that FFRDC PMO officials have not consistently shared Annual Assessment results with FFRDC leadership, as required by DHS directive, although they have shared feedback—such as project performance or staffing issues—through other channels.[59] Specifically, both HSSEDI and HSOAC leaders told us they had not received or been briefed on Annual Assessment results for fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2022. FFRDC PMO officials and FFRDC leadership stated that FFRDC PMO officials share feedback with FFRDCs through channels other than the Annual Assessments.

For example, FFRDC PMO officials told us they hold quarterly review meetings, during which they provide FFRDC leadership with feedback both at a project and a strategic level. Additionally, FFRDC PMO officials stated they schedule ad hoc meetings with FFRDC leadership in response to specific feedback from a program manager or other S&T and DHS component officials regarding the FFRDC’s performance on a task order. Leaders from both HSSEDI and HSOAC agreed they receive oral and written feedback from FFRDC PMO. However, HSOAC leadership stated they would appreciate having more structure in the feedback and seeing the user feedback survey results, both of which could be achieved through sharing the Annual Assessments.

FFRDC PMO officials told us they do not share the results of annual assessments with FFRDCs due to the sensitive nature of the feedback and because of the time lag between the user feedback survey results and the annual assessment report. While feedback on individual task orders could include sensitive information, such as the identities of the S&T and DHS component program managers who provided the feedback, FFRDC PMO officials told us they regularly provide project-level and strategic feedback to FFRDCs through quarterly and ad hoc review meetings. Moreover, the user survey results provided in the Annual Assessments are aggregated.

DHS directs FFRDC PMO to share the results of Annual Assessments with FFRDC management and provide feedback and assistance in resolving problems.[60] By consistently sharing Annual Assessments with FFRDC leadership, as required by DHS directive, FFRDC leadership can receive a holistic assessment of their performance rather than feedback about individual projects. This holistic view could provide the FFRDCs a better understanding of their overall performance across DHS components and areas in which they need to improve.

FFRDC PMO Receives Some Information on DHS’s Use of Task Order Results but Does Not Sufficiently Review and Analyze How DHS Uses Results

FFRDC PMO Receives Some Information on How Task Order Results Are Used

FFRDC PMO officials told us that they receive some information on how S&T and DHS components use results for some FFRDC task orders.[61] FFRDC PMO officials may receive feedback on the use of task order results in the following instances.

· In preparation for a Comprehensive Review, FFRDCs provide FFRDC PMO officials with summaries of between 12 to 14 selected task orders they have completed that showcase the FFRDCs’ skills in their fields of expertise. These case studies discuss how S&T and DHS components used the task order results and the extent to which the results met their needs. For example:[62]

· U.S. Coast Guard satellite connectivity. To address reliability issues with the satellite communications capabilities of U.S. Coast Guard ships—which were affecting operational readiness and efficiency—HSSEDI adapted MITRE’s satellite communications software to support U.S. Coast Guard’s satellite communications operations. As a result, according to HSSEDI, U.S. Coast Guard improved its operational readiness and efficiency fleet-wide. HSSEDI addressed this issue through U.S. Coast Guard task orders, MITRE’s independent research program, and other FFRDC work.

· Data analytic capability for export enforcement. To enhance U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement labor- and time-intensive manual investigation of the export of sensitive U.S. technology, materials, and products, HSSEDI developed an enhanced data analytic capability. S&T requested that HSSEDI develop a way to track the shipment of individual components that could be assembled into a weapon. HSSEDI stated that it developed improved tools for investigators to find linkages between shippers, receivers, and methods of shipping, which helps them save time, more efficiently track sensitive technology, and discover new ways to track illegal activity. In December 2017, U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (now the “Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office”) partnered with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to explore options for adapting this data analytic capability to their own missions. HSSEDI addressed this issue through a S&T task order, MITRE’s independent research program, and other MITRE FFRDCs.

· FFRDC PMO officials said they also reach out to S&T and DHS components for examples of unique or noteworthy task orders that went well and details on how S&T and DHS components used the results. FFRDC PMO officials told us they use these examples in their educational outreach to S&T and DHS components on the benefits of using FFRDCs to address research and development (R&D) needs.

· FFRDC PMO officials said they can also receive some feedback from S&T and DHS components when individual task order results did not meet the components’ needs or they had issues with the FFRDC during the implementation of the task order. This feedback is relatively infrequent, however, compared to the positive feedback FFRDC PMO officials receive from the FFRDCs and solicit from S&T and DHS components.

FFRDC PMO Does Not Sufficiently Review and Analyze S&T and DHS Components’ Use of Task Order Results Due to Limited Collection of Information

Our review of key documents from selected FFRDC task orders, interviews with selected S&T and DHS component program managers who oversaw those task orders, and discussions with FFRDC PMO officials found that FFRDC PMO does not sufficiently review and analyze how S&T and DHS components use task order results (deliverables) to be better informed as to how well those results overall meet users’ needs. Specifically, while FFRDC PMO officials receive some information on task order results that FFRDCs, S&T, and DHS components identify as having worked well, they receive comparatively less information about the range of task order results, including ones that did not meet S&T and DHS components’ expectations or otherwise did not work out well. As a result, FFRDC PMO officials are not positioned to review and analyze comprehensive task order results, which would help FFRDC PMO officials to better understand how results met user needs and to identify and address issues of concern.

Our analysis of selected task order documents showed that FFRDC PMO and other stakeholders did not indicate whether FFRDC PMO followed up with S&T and DHS components to determine how task order results were used. In addition, of the 17 S&T and DHS component program managers we interviewed, one told us he had discussed with FFRDC PMO how his agency had used the task order results after the order was completed. In this instance, the follow-up was part of routine meetings his agency holds to discuss the results of R&D work.

FFRDC PMO officials stated that they do not have the time and staff to follow up with S&T or DHS components on every task order to determine how and to what extent the results were used. However, officials stated that obtaining more information on how and to what extent S&T or DHS components used the task order results would help them to identify particularly noteworthy task orders to showcase in Comprehensive Reviews and in educational outreach efforts.

Key practices for evidence-based policymaking that we identified in prior work state that reviewing program outcomes can help organizations identify effective approaches to solving issues, such as performance challenges or trends in below-standard performance, as well as lessons learned.[63] In addition to helping to identify which processes are working well, it also helps to identify processes that are not working well and which may require changes or new approaches. Reviewing outcomes also helps organizations better understand what led to the results they achieved or why desired results were not achieved.

Ensuring that FFRDC PMO officials review and analyze a selection of completed task orders that better reflect a range of results would allow them to better understand the extent to which task order results are meeting S&T and DHS components’ needs. To accomplish this, FFRDC PMO officials could explore options for identifying and reviewing a broader range of results from a selection of task orders.

For example, FFRDC PMO officials could request from S&T and the DHS components examples of task orders in which the results did not exceed or meet expectations, to complement their ongoing outreach efforts. Additionally, FFRDC PMO officials could identify and review results from a random selection of completed task orders. The selection would not need to be so large as to be generalizable, but large enough to provide a more balanced picture of S&T’s and DHS components’ satisfaction with task order results. This approach would provide more insight as to S&T’s and DHS components’ use of task order results, including those that did not work out well.

Establishing a process to review a selection of task orders with results that reflect an array of outcomes, including those that did not meet expectations, and analyzing that information, could help to inform FFRDC PMO’s future decision-making regarding the design and implementation of task orders. This information could also enhance S&T’s understanding of FFRDC performance as presented in the FFRDC Annual Assessments and Comprehensive Reviews.

Conclusions

Since 2004, DHS has obligated billions of dollars on contracts for DHS FFRDCs to research issues and technologies that affect homeland security. These obligations represent a significant investment in R&D. Recognizing the scope and importance of this investment, S&T has established a process to coordinate DHS’s R&D activities, including proposed FFRDC projects. However, S&T’s R&D coordination process may not always include component-funded R&D projects. In those instances, S&T officials may use the annual list of DHS R&D projects that S&T submits each year to Congress. Updating this list at least quarterly, as required by statute, and disseminating the updated list to relevant DHS entities, including DHS components, would offer DHS a more updated and useful resource with which it could review proposed FFRDC projects for potentially unnecessary overlap with other DHS R&D projects.

S&T’s R&D coordination process may not always include DHS component-funded R&D activities. Amending policies and procedures to require S&T to review those R&D activities for unnecessary overlap with proposed FFRDC projects could better ensure that DHS investments in R&D activities reduces the potential for this. Moreover, documenting the results of the overlap review could better ensure that S&T conducts the reviews and informs relevant parties about them.

Given the importance of FFRDCs’ role in addressing critical DHS R&D needs that are integral to its mission and operation, the department has developed internal guidance for assessing FFRDCs’ work performance, in addition to federal requirements, which FFRDC PMO officials implement. Receiving, analyzing, and sharing key user feedback survey information is a critical underpinning of FFRDC PMO’s efforts to assess FFRDC work performance. Yet, FFRDC PMO has not addressed issues in these areas that may impact its ability to fully and successfully assess FFRDC performance, such as not understanding potential risks posed by using incomplete survey information and not comprehensively analyzing users’ open-ended survey responses in addition to ratings data. Assessing the risk of low survey response rates across FFRDCs, comprehensively analyzing users’ open-ended survey responses, and sharing the results of their assessments with FFRDC leadership (as required) would allow FFRDC PMO officials to more fully leverage the data they use to assess FFRDC work performance, provide the FFRDCs with a holistic assessment of performance, and potentially enhance the quality of their performance assessments.

While user feedback survey data are an invaluable source of information on FFRDC performance, gathering additional information on how FFRDC sponsors use the results of task orders could provide unique insight into the longer-term impact of FFRDC work. In addition, obtaining data on a range of user’s experiences that produced an array of outcomes—experiences that worked out well and those that did not—could provide a more balanced understanding of FFRDCs’ work and the extent to which it meets users’ needs. It could also help FFRDC PMO’s design and implementation of task orders in the future.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following eight recommendations to DHS:

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should update the list of R&D activities on at least a quarterly basis, as statutorily required, and disseminate the updated list to relevant DHS entities, including DHS components. (Recommendation 1)

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should amend policies and procedures to require that S&T review proposed FFRDC projects for unnecessary overlap with R&D activities funded and developed by DHS components that have their own R&D appropriations. (Recommendation 2)

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should require S&T to document its additional overlap reviews of R&D activities funded and developed by DHS components that have their own R&D appropriations. (Recommendation 3)

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should ensure that FFRDC PMO conducts and documents an analysis of the risk of nonresponse bias based on the response rate of the initial outreach efforts for each fiscal year’s set of user feedback surveys. Should the analysis indicate a risk of nonresponse bias which would influence FFRDC PMO’s understanding of FFRDC performance, FFRDC PMO should take additional steps to increase their response rate. (Recommendation 4)

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should ensure FFRDC PMO documents, in all Annual Assessments and 5-Year Comprehensive Reviews, the response rate, risk of bias, and steps taken to increase the user feedback survey response rate. (Recommendation 5)

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should amend its policies and procedures to require FFRDC PMO to include a comprehensive analysis of open-ended responses to FFRDC user surveys in the Annual Assessments to gain a more complete understanding of user feedback when assessing FFRDC performance. (Recommendation 6)

The DHS Under Secretary for Science and Technology should ensure that FFRDC PMO shares, as required, the results of Annual Assessments with FFRDC leadership. (Recommendation 7)

The Under Secretary for Science and Technology should ensure that FFRDC PMO establishes a process to review and analyze a selection of task order results that reflect a range of S&T and DHS component experiences to inform the design and implementation of FFRDC task orders. (Recommendation 8)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this product to DHS for review and comment. DHS provided written comments, which are summarized below and reproduced in full in appendix VI. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In its written comments, DHS concurred with our eight recommendations and identified actions planned or undertaken to address them.

Regarding recommendations 2 and 3, we initially proposed that S&T and DHS component sponsors take steps to identify unnecessary FFRDC project overlap, and document the results, during FFRDC PMO’s task order appropriateness review. However, S&T officials clarified that the purpose of the appropriateness review is to assess whether a proposed task order is appropriate for a FFRDC. Therefore, using the review to identify potential project overlap would be outside the scope of the review. In response to these comments, we modified recommendations 2 and 3 and made conforming changes throughout the report to remove references to the appropriateness review as the point in time in which a project overlap review should occur.

With respect to our first recommendation that S&T should update the list of R&D activities on at least a quarterly basis, as statutorily required, and disseminate the updated list to relevant DHS entities, DHS concurred and noted that it would coordinate with the heads of DHS components and headquarters offices to collect and share R&D activities with relevant entities on a quarterly basis. It also noted that S&T would implement quarterly updates of the R&D activities inventory and facilitate centralized access to the inventory on an internal website for DHS entities to access. These steps, if fully implemented, should address the intent of this recommendation.

With respect to our second recommendation that DHS should amend policies and procedures to require that S&T review proposed FFRDC projects for unnecessary overlap with R&D activities funded and developed by DHS components with their own R&D appropriations and to document these reviews, DHS concurred. The department noted that S&T plans to conduct a study in fiscal year 2025 to determine needed actions, to include a baseline of all “entry points” for DHS component R&D appropriations to FFRDCs and other DHS offices that receive R&D appropriations for Innovation, Research, and Development support. After the baseline is established, S&T plans to conduct a gap analysis to identify and consider all relevant policies and processes. S&T would use this information to develop a capability roadmap and associated implementation costs for determining resource needs. We will monitor S&T’s implementation actions and the extent to which they address this recommendation.

DHS also concurred with our third recommendation that S&T document its additional overlap reviews of R&D activities self-funded by DHS components. The department noted S&T plans to identify the appropriate avenue to document overlap review results in fiscal year 2026, after it completes the study for recommendation 2. We will monitor S&T’s implementation actions and the extent to which they address this recommendation.

With respect to our fourth recommendation that FFRDC PMO conduct and document an analysis of the risk of nonresponse bias based on response rates of initial outreach efforts for each fiscal year’s set of user feedback surveys, DHS concurred. DHS noted that FFRDC PMO plans to analyze the risk of nonresponse bias in FFRDC user survey response rates for each fiscal year. To develop this analysis, FFRDC PMO plans to study the Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology’s best practices for analyzing nonresponse bias and identify the resources needed to implement a future approach. In fiscal year 2026, FFRDC PMO plans to use fiscal years 2025 and 2026 FFRDC user feedback survey responses and associated data to pilot test an approach and will use the resulting information to assess the risk of nonresponse bias. We will monitor FFRDC PMO’s implementation actions and the extent to which they address this recommendation.

DHS also concurred with our fifth recommendation that FFRDC PMO document, in all FFRDC Annual Assessments and Comprehensive Reviews, the applicable FFRDC survey response rate(s), risk of bias, and any steps it takes to increase the FFRDC user feedback survey response rate. DHS noted that FFRDC PMO plans to document the results of the analysis it conducts in response to recommendation 4 in future Annual Assessments and apply the outputs in the fiscal year 2026 HSOAC Comprehensive Review. We will monitor FFRDC PMO’s implementation actions and the extent to which they address this recommendation.

With respect to our sixth recommendation that S&T amend its policies and procedures to require FFRDC PMO to include a comprehensive analysis of open-ended responses to FFRDC user surveys in FFRDC Annual Assessments, DHS concurred. DHS noted that in fiscal year 2025, FFRDC PMO will conduct an analysis to determine what is needed to ensure a comprehensive analysis of user responses to open-ended survey questions and pilot test the results in fiscal year 2026. FFRDC PMO plans to use the test results to amend its policies and procedures and require a comprehensive analysis of open-ended responses to FFRDC user feedback surveys. We will monitor FFRDC PMO’s implementation actions and the extent to which they address this recommendation.

With respect to our seventh recommendation that FFRDC PMO shares, as required, the results of FFRDC Annual Assessments with FFRDC leadership, DHS concurred. The department noted that FFRDC PMO will coordinate with FFRDC leadership, as appropriate, to identify a recurring timeframe to formally share the results of the FFRDC Annual Assessments. These steps, if fully implemented, should address the intent of this recommendation.

With respect to our eighth recommendation that FFRDC PMO establish a process to review and analyze a selection of task order results that reflect a range of S&T and DHS component experiences to inform the design and implementation of FFRDC task orders, DHS concurred and requested that we close the recommendation as implemented, based on ongoing actions. Specifically, DHS noted that FFRDC PMO already reviews and analyzes a selection of task orders with the FFRDCs to improve task order practices.

However, as detailed in this report, we found that FFRDC PMO does not sufficiently review and analyze how S&T and DHS components use task order results to better understand how well those results overall meet users’ needs. The reviews FFRDC PMO discusses in its response focus on the “health” of ongoing task orders,” such as “progress to date,” rather than how the results of completed task orders have been used, including those that did not work out well or did not meet expectations. Reviewing such information would help FFRDC identify and better address issues of concern. To fully address our recommendation FFRDC PMO should collect information on a range of task order outcomes.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions concerning this report, please contact Tina Won Sherman at (202) 512-8461 or ShermanT@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VII.

Tina Won Sherman

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

|

Founded 2016 Contractor RAND Headquarters location Santa Monica, CA Primary sponsor Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Executive agent for the primary sponsor DHS’s Science and Technology Directorate |

Contract Information Indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract, awarded sole-sourcea How projects are placed on contract: through task orders Type: Cost-plus-fixed-fee Latest contract extension: March 23, 2022 Total value: $495 million Period of performance: March 24, 2022, through March 23, 2027b Contracting office: DHS, Office of Chief Procurement Officer, Office of Procurement Operations, Science and Technology Acquisition Division |

|

Task orders FY2023: 45 FY2023: $85,589,049 FY2022: 65 FY2022: $71,865,882 FY2021: 44 FY2021: $66,848,338

|

|

|

DHS component sponsors include, among others, · Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office · Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency · Federal Emergency Management Agency · Science and Technology Directorate · Transportation Security Administration · U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

Background HSOAC provides DHS with studies and analysis expertise. HSOAC supports DHS in addressing analytic, operational, and policy challenges in its mission areas and across the homeland security environment. HSOAC provides analysis to identify vulnerabilities and future risks, help DHS improve management and planning, and improve the agency’s operational processes and procedures. |

|

Focus areas (i.e., areas of expertise or specialization) · Acquisition studies · Preparedness, response, and recovery · Innovation and technology acceleration · Homeland security threat and opportunity studies · Personnel policy and management studies · Operational studies · Organizational studies · Regulatory, doctrine, and policy studies · Research and development studies |

Source: GAO analysis of DHS Science and Technology Directorate information and data. | GAO‑25‑106394

aA “sole-source” contract is one that was awarded on a non-competitive basis.

bThe period of performance for RAND’s prior contract was September 19, 2016, through March 23, 2022, with an indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract ceiling of $495 million.

Appendix II: Information on Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute (HSSEDI)

|

Founded 2009 Contractor MITRE Headquarters location Bedford, MA, and McLean, VA Primary sponsor Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Executive agent for the primary sponsor DHS’s Science and Technology Directorate |

Contract Information Indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract, awarded sole-sourcea How projects are placed on contract: through task orders Type: Cost-plus-fixed-fee Latest contract extension: March 23, 2020 Total value: $1.42 billion Period of performance: March 24, 2020, through March 23, 2025b Contracting office: DHS, Office of Chief Procurement Officer, Office of Procurement Operations, Science and Technology Acquisition Division |

|

Task orders FY2023: 72 FY2023: $221,938,359 FY2022: 59 FY2022: $193,704,101 FY2021: 57 FY2021: $155,955,4

|

|

|

DHS component sponsors include, among others · Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office · Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency · Federal Emergency Management Agency · Science and Technology Directorate · Transportation Security Administration · U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

Background HSSEDI is a systems engineering and integration center that supports the Department of Homeland Security by providing specialized technical and systems engineering expertise to S&T, DHS components, program managers, and operating elements in addressing national homeland security system development issues related to the development and delivery of DHS capabilities. HSSEDI achieves its program objectives through efforts such as the recommendation of new technologies and establishment of technical standards, measures, and best practices. |

|

Focus

areas · Acquisition planning and Development · Emerging threats, concept exploration, experimentation and evaluation · Information technology and communications · Cyber solutions / operations · Systems engineering, system architecture and integration · Technical quality and performance · Independent test and evaluation |

Source: GAO analysis of DHS science and Technology Directorate information and data. | GAO‑25‑106394

aA “sole-source” contract is one that was awarded on a non-competitive basis.

bThe period of performance for MITRE’s prior contract was September 24, 2014, through March 23, 2020, with an indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract ceiling of $675 million.

This report addresses the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) use and oversight of two Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDC)—the Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute (HSSEDI), operated by MITRE since 2009, and the Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center (HSOAC), operated by RAND since 2016. These FFRDCs are organized under DHS’s Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) and overseen by the FFRDC Program Management Office (PMO).[64]

Specifically, we examined the extent to which

1. S&T has reviewed DHS’s proposed FFRDC projects for potential unnecessary overlap with other DHS Research and Development (R&D) projects;[65]

2. S&T’s FFRDC PMO has developed tools to assess FFRDCs’ performance and receives, analyzes, and shares key work performance information;[66] and

3. S&T’s FFRDC PMO has reviewed and analyzed DHS’s use of the results of FFRDC task orders.[67]

To address all our objectives, we identified the number of task orders issued to the two FFRDCs from September 2014 through February 2023. We chose this 9-year period to include the ongoing 5-year FFRDC contract period and the immediately preceding completed 5-year base contracts awarded to MITRE and RAND to operate HSOAC and HSSEDI, respectively. These two contract periods include operations starting in 2014 for HSSEDI and in 2016 for HSOAC and allowed us to review (1) the number of S&T and DHS component task orders issued over time, (2) roughly parallel time periods for each FFRDC, and (3) one complete and one ongoing 5-year contract period for each FFRDC. Including a complete contract period also allowed us to review the most recent 5-year Comprehensive Review performance appraisal for each FFRDC.[68]

We assessed the reliability of the task order data by reviewing relevant guidelines and processes for entering and maintaining the data, such as S&T’s Collaboration Site (STCS) Governance Plan.[69] We also interviewed relevant S&T officials to better understand how the data are compiled, maintained, and verified, and to identify internal controls for ensuring data accuracy and completeness. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of identifying (1) the number of task orders issued, (2) task order amounts and performance period, (3) task order sponsors (S&T and DHS components), and (4) key task order documents (e.g., task order documentation and appropriateness certification).