PREGNANT WOMEN IN STATE PRISONS AND LOCAL JAILS

Federal Assistance to Support Their Care

Report to Congressional Requesters

October 2024

GAO-25-106404

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106404. For more information, contact Gretta L. Goodwin, 202-512-8777, GoodwinG@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106404, a report to congressional requesters

October 2024

Pregnant women in STATE PRISONS AND LOCAL JAILS

Federal Assistance to Support Their Care

Why GAO Did This Study

According to HHS, the U.S. has one of the highest maternal mortality rates among high-income nations, increasing rates of complications from pregnancy or childbirth, and persistent racial disparities in such outcomes. The U.S. also incarcerates women at the highest rate in the world, and the vast majority reside in state prisons or local jails.

GAO was asked to review maternal health care in state prisons and local jails. This report describes, among other issues, (1) available data on incarcerated pregnant women, (2) available federal support, and (3) challenges to providing care to this population and opportunities to enhance care.

GAO reviewed (1) existing available data on pregnant women incarcerated in state prisons and local jails, (2) federal grant information, and (3) relevant studies and peer reviewed articles. GAO also interviewed officials representing 9 state prisons and 9 local jails from a nongeneralizable sample of 12 states about maternal health care in their facilities. GAO visited prisons and jails in 3 states and interviewed 27 incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women about the care they received.

What GAO Found

Comprehensive national data on pregnant women incarcerated in state prisons and local jails do not exist. For example:

· Limited data reported by the Department of Justice (DOJ) indicates that about 4 percent of women in state prisons in 2016 and 5 percent of women in local jails in 2002 were pregnant at the time of admission. DOJ did not report on the demographics—such as race or ethnicity—or pregnancy outcomes of these women.

· The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) collects near national-level data on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes, but none of these efforts have systematic indicators to identify incarcerated pregnant women.

· Additionally, officials representing selected state prisons and local jails told GAO that they collect some information on pregnant women, such as pregnancy status at admission. However, the data are limited due to challenges they face with collecting, analyzing, and reporting data.

However, DOJ currently has an effort underway to collect more data through a voluntary survey of state prisons and expects to issue a report in 2025. The survey will request the count of women tested for pregnancy at admission and the number of those tests that are positive, among other things.

According to HHS and DOJ officials, five HHS and 10 DOJ grant programs could be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails during fiscal years 2018 through 2023, the most recent data available at the time of GAO’s review.

· The purposes of HHS’s five grant programs include providing health and education services to pregnant women and children, among other purposes. According to HHS officials, at least 23 of its grant awards were used to provide maternal health care in state prisons or local jails during this time. For example, one HHS grant recipient reported using grant funds to support its prison nursery, where eligible incarcerated mothers reside with their babies until the mother’s release from incarceration, up to 36 months.

· The primary purpose of DOJ’s 10 grant programs is to enhance substance use and other behavioral health treatments and improve reentry outcomes for people leaving prisons and jails. DOJ officials were not aware of, and GAO found no indication that, any of its grant funds were used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails.

Challenges and opportunities exist for providing maternal health care in state prisons and local jails. For example, officials representing three prisons reported and two peer reviewed articles GAO reviewed identified challenges with coordinating transportation for medical appointments for pregnant women that occur outside their facilities, which can delay or impede women’s access to maternal health care. Relevant literature also identified opportunities to address challenges, such as expanding program offerings to support pregnant women. Examples of such programs include mental health treatment, lactation, and mother-infant bonding programs.

Abbreviations

ACF Administration for Children and Families

ACOG American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

BJS Bureau of Justice Statistics

BOP Bureau of Prisons

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

DOC Department of Corrections

DOJ Department of Justice

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration

NGO nongovernmental organization

OJP Office of Justice Programs

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 2, 2024

Congressional Requesters

According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. is facing a maternal health crisis. The U.S. has one of the highest maternal mortality rates among high-income nations, increasing rates of complications from pregnancy or childbirth, and persistent racial disparities in such outcomes.[1] For example, we previously reported that HHS data indicate the maternal mortality rate among non-Hispanic Black or African American women was about 2.5 times greater than non-Hispanic White women in 2020 and 2021.[2]

In addition, according to the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research, the U.S. also incarcerates women at the highest rate in the world.[3] This includes around 168,800 women in federal and state prisons or local jails in 2022, according to the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). The most recent available BJS data on pregnancy also indicates that about 4 percent of women in state prisons and about 5 percent of women in local jails reported being pregnant at the time of admission.[4] The vast majority of incarcerated individuals reside in state or local correctional facilities.[5]

The White House released the Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis (blueprint) in June 2022.[6] The blueprint identifies goals and actions the federal government is taking, or plans to undertake, to decrease rates of maternal mortality and morbidity; reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes, such as racial and socioeconomic disparities; and improve the overall experience of pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period for women across the U.S.[7] The blueprint includes several federal efforts that could support maternal health care for incarcerated women, such as training and hiring doulas.[8]

We previously reviewed issues related to pregnant women in federal custody. In 2020, we issued a report on the care of pregnant women in Department of Homeland Security immigration detention facilities.[9] In 2021, we reported on pregnant women in DOJ custody.[10] Further, in 2021, 2022, and 2024 we reported on maternal morbidity and mortality, and disparities in maternal health outcomes, including racial and rural-urban disparities.[11]

You asked us to review issues related to maternal health care in state prisons and local jails. This report addresses the following questions:

1. What data are available on the characteristics of incarcerated pregnant women and pregnancy outcomes in state prisons and local jails?

2. What federal assistance can be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails?

3. How do selected state prisons and local jails provide maternal health care for incarcerated pregnant women?

4. What are the identified and reported challenges and opportunities to providing maternal health care to incarcerated pregnant women?

To address all four questions, we interviewed officials representing nine state prisons and nine local jails from across 12 states about maternal health care in their facilities.[12] We selected this nongeneralizable sample of states based on several factors. For example, we included states with a range of state female incarceration rates that generally had higher numbers of women under the jurisdiction of state correctional authorities or incarcerated in local jails.[13]

We conducted semi-structured interviews with officials representing all selected facilities in which we asked about (1) the data they collect on pregnant women in their facilities, (2) their knowledge of available federal assistance to support maternal health care for this population, and (3) the provision of maternal health care in their facilities—including any challenges they may experience in providing this care. The information these officials provided was reported to us during interviews, in written responses, or in relevant documentation. We report perspectives from officials representing state prisons and local jails in the aggregate, due to the sensitivity of some of the information we received about pregnant women and maternal health care at these facilities. In addition, we conducted in-person visits to prisons and jails in three states between June and November 2023.[14] In the states where we visited prisons and jails in-person, we also conducted semi-structured interviews with 27 incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women. We asked officials from the facilities to identify women who were pregnant or postpartum at the time of our visits and to ask for volunteers to participate. We also asked, if possible, to meet with women that reflect the facility’s racial and ethnic diversity. We asked the women about their experiences related to the maternal health care and resources they received, among other topics.

To address the first and fourth questions, we conducted a literature review of studies, peer-reviewed articles from researchers, and articles from national entities published from January 2013 through April 2023. We conducted keyword searches in ProQuest, Dialog Healthcare Databases, Scopus, Ebsco, and PubMed and screened each article for relevance. For any studies, we reviewed the methodologies to ensure that they were sound and determined that they were sufficiently reliable for our purposes. Through this review, we identified 12 articles that included data on pregnant and postpartum women incarcerated in state prisons and local jails. We also identified 33 articles that discussed challenges, recommended standards, or programs related to providing maternal health care to incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women.

To address the first question about available data, we determined the extent of available federal data on pregnant women incarcerated in state prisons and local jails. To collect information from federal entities, we interviewed or received written responses from DOJ and HHS about the extent to which they collect data on this population. Further, we reviewed available reports from BJS that provided relevant data. Additionally, we reviewed datasets from HHS that include data on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes to determine to what extent, if any, we could identify incarcerated women in these datasets.[15]

To address the second question about available federal assistance, we reviewed federal grant information from DOJ and HHS and interviewed officials representing selected state prisons and local jails. As part of our review of grant programs that DOJ and HHS identified as relevant, we reviewed grant solicitations and information about awards used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, the most recent data available at the time of our review. In our interviews with officials representing selected prisons and jails, we asked about their awareness of federal assistance to support maternal health care in their facilities and asked them to describe the types of federal assistance that would be useful. We also reviewed the efforts that DOJ and HHS are taking to respond to the blueprint by interviewing and collecting information from knowledgeable DOJ and HHS officials and reviewing the actions and goals for DOJ and HHS described in the blueprint.

Finally, to address the second and fourth questions on available federal assistance and challenges and opportunities to providing maternal health care in state prisons and local jails, we interviewed officials from five nongovernmental organizations.[16] We selected these entities because their work is related to maternal health care for incarcerated women.

For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2022 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Operation and Oversight of State Prisons and Local Jails

According to BJS, there were approximately 1,200 state prisons and 3,100 local jails across the U.S. as of 2019.[17] Women resided in approximately 200 public state prisons and accounted for about 8 to 9 percent of the total state prison population.[18] Additionally, as of 2019, women accounted for up to 15 percent of the total local jail population.[19]

Prisons and jails incarcerate different populations. Prisons incarcerate individuals after they are convicted of a criminal offense and typically incarcerate those serving a sentence of more than 1 year. Jails incarcerate individuals before or after court adjudication and typically incarcerate those serving a sentence of 1 year or less. The operation and oversight of prisons and jails also differs. Prisons typically operate under the authority of state departments of corrections (DOCs). Oversight of jails varies by state. State DOCs or other state-level bodies may oversee jails or may have no oversight role.[20] Local jurisdictions, such as a sheriff’s office, usually operate and oversee local jails. A local jurisdiction may oversee multiple local jails. The federal government does not have a role in operating state prisons and local jails.

Trends in the Incarceration of Women in Prisons and Jails

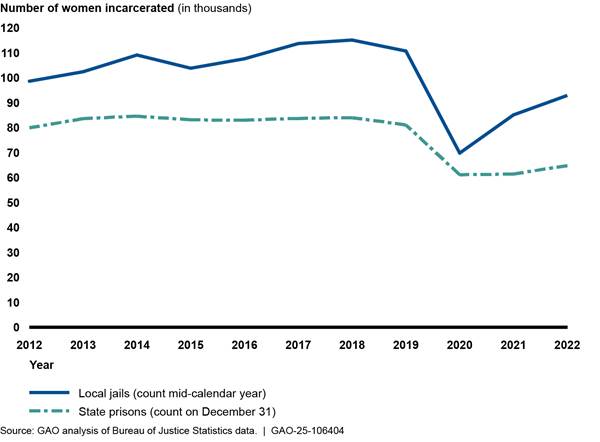

The number of women incarcerated in prisons and jails is increasing, following a temporary period of decline during the COVID-19 pandemic.[21] BJS data indicate the number of women in prisons and jails increased from 2012 through 2019, decreased in 2020 during the pandemic, and has since increased again.[22] Specifically, in 2020, the number of women in state prisons decreased by 25 percent compared to 2019 pre-pandemic levels, while the number of women in local jails decreased by 37 percent. By 2022, the number of women in state prisons and local jails was at about 80 percent of the pre-pandemic levels.[23] See figure 1 for more information.

Additionally, BJS data indicate that women of different racial and ethnic groups are incarcerated in U.S. federal and state prisons at different rates. See the text box below for more information about how these rates differ.

|

Incarceration Rates for Women in Federal and State Prisons Varies by Racial and Ethnic Groups According to the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) data, women of different racial and ethnic groups are incarcerated in state and federal prisons at different rates. BJS reported the following incarceration rates for women in 2022: •All women: 49 per 100,000 •White women: 40 per 100,000 •Black or African American women: 64 per 100,000 •Hispanic or Latina women: 49 per 100,000 •American Indian/Alaska Native women: 173 per 100,000 •Asian women: 5 per 100,000 •Women of two or more races (not specified): 269 per 100,000 |

Source: BJS data | GAO‑25‑106404

Supreme Court Rulings on Access to Health Care

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that incarcerated individuals have a constitutional right to adequate medical and mental health care. In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that deliberate indifference to the serious medical needs of prisoners by prison personnel constitutes the unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.[24] Similarly, in 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court held that adequate medical and mental health care must meet minimum constitutional requirements and meet prisoners’ basic health needs.[25] As such, incarcerated pregnant women, including those in state prisons and local jails, have a constitutional right to adequate medical and mental health care to support their pregnancies, deliveries, and postpartum period.

Standards and Guidance for the Care of Pregnant Women

Incarcerated pregnant women have a unique set of health and safety needs, such as access to prenatal care and maternal nutrition. Various professional organizations recommend standards and guidance for the care of pregnant women in correctional settings. These organizations include the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Correctional Association, and the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, among others.[26] Adherence to these standards and guidance is voluntary. Some of these professional organizations offer accreditation to correctional facilities that demonstrate they meet their recommended standards and guidance. However, there is no national requirement that facilities obtain and maintain accreditation. According to BJS officials, some jurisdictions or facilities may be required contractually or statutorily to adhere to accreditation standards and guidelines.

Federal Role

Multiple entities within DOJ and HHS have a role in maternal health care for incarcerated pregnant women:

· DOJ’s BJS collects, analyzes, publishes, and disseminates information on the operation of justice systems at all levels of government, including on state prisons and local jails. BJS also provides financial and technical support to state, local, and tribal governments to improve their statistical capabilities.

· DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs, the largest grantmaking component of DOJ, awards federal assistance through its many grant programs. Some of these grant programs can be used to support maternal health care, which we describe later in this report.

· DOJ’s Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is largely responsible for the custody and care of people incarcerated by the federal government.

· HHS agencies collect data on U.S. pregnancy and maternal health outcomes, including maternal morbidity and mortality. For example, HHS’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention manages the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System which collects data on maternal attitudes and experiences before, during, and shortly after pregnancy. The births in the jurisdictions participating in this effort represent approximately 81 percent of all live births in the U.S.

· HHS’s Health Resources and Services Administration and Administration for Children and Families, among other HHS agencies, also award federal assistance through their many grants programs to state, local, and tribal governments. Some of these grant programs can be used to support maternal health care, which we describe later in this report.

Comprehensive National Data on Incarcerated Pregnant Women Do Not Exist, but DOJ Has a Collection Effort Underway

DOJ and HHS Have Limited Information on the Population of Incarcerated Pregnant Women in State Prisons and Local Jails

DOJ’s BJS does not regularly collect comprehensive data on incarcerated pregnant women in state prisons and local jails—nor are state DOCs and jails typically required to provide data to BJS. In prior years, BJS conducted two separate periodic data collection efforts that provided limited information on pregnant women in prisons and jails. Most recently, BJS published the findings in reports issued in 2021 and 2006, respectively.[27] In 2021, BJS reported that as of 2016 about 4 percent of women in state prisons reported being pregnant at the time of admission. Of these women, 91 percent reported they received an obstetric exam and 50 percent reported they received some other form of prenatal care.[28] In 2006, BJS reported that as of 2002 about 5 percent of women in local jails reported being pregnant at the time of admission. Of these women, 48 percent reported they received an obstetric exam and 35 percent reported they received some other form of prenatal care.[29] Neither of these studies provides demographic characteristics, such as the race and ethnicity, of the incarcerated pregnant women in prisons and jails.[30]

Further, HHS does not collect comprehensive data on incarcerated pregnant women in any type of correctional facility—nor is it required to do so. HHS has five national or near national-level data collection efforts related to maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. These include HHS’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, National Vital Statistics System, Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, and Maternal Mortality Review Information Application data collection efforts. These efforts, however, do not have systematic indicators to identify incarcerated pregnant women. According to HHS, while these efforts collect granular data on maternal health outcomes and pregnancy outcomes, none of them systematically identify whether the women are incarcerated in state prisons and local jails. For example, the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System collects data on maternal attitudes and experiences, before, during, and shortly after pregnancy, but does not collect specific data on whether women were incarcerated in a state prison or local jail during their pregnancies or at the time of delivery.

BJS Has Efforts Underway to Collect More Comprehensive Data

DOJ’s BJS has efforts underway intended to collect more comprehensive data on incarcerated pregnant women through a voluntary survey of state prisons. In fiscal year 2021, Congress directed BJS to amend its ongoing data collection efforts with prisons and jails to include collecting statistics related to the health needs of incarcerated pregnant women in the criminal justice system.[31] This includes statistics on the number of pregnant women in custody, outcomes of pregnancies, the provision of pregnancy care and services, the health status of pregnant women, and any racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health at the federal, state, tribal, and local levels.

In response, BJS first conducted a maternal health feasibility study in 2021 and 2022 to determine the types of data it could collect from prisons and jails.[32] As part of this study, BJS interviewed BOP, 21 state DOCs, and 20 local jails. In its 2024 report about its findings from the feasibility study, BJS acknowledged that there has been little research or data to date on maternal health in carceral settings, and there is a need for better data on women who are pregnant, outcomes of their pregnancies, and postpartum recovery while incarcerated. Additionally, BJS stated that such data are necessary to assess and address the health needs of incarcerated women related to pregnancy and childbirth.

In the 2024 maternal health feasibility study report, BJS stated that it is feasible to collect some maternal health data from state prisons and local jails but noted challenges to this effort. For example, BJS reported that state prisons and local jails participate in surveys on a voluntary basis, so it must work to get support from the state prison systems and local jail facilities from which it wants to collect information. Additionally, BJS reported that prisons and jails face technical and resource challenges that increase the burden of participating in these surveys. For example, BJS said in its report that the most frequently cited technical challenge by facilities was related to the location and format of maternal health data, noting that some electronic files are not easily searchable. As a result, facilities reported to BJS they would need more resources, such as additional staff, to manually review individual files and compile maternal health data in a timely manner. BJS made five recommendations in the report to mitigate the challenges it identified.[33]

Following the feasibility study, BJS officials told us they will conduct a one-time voluntary survey of state DOCs, on behalf of prisons, to collect information on maternal health care and pregnancy outcomes in state prisons as of the end of calendar year 2023.[34] The survey will request the count of women tested for pregnancy at admission, the number of those tests that are positive, and the number of pregnancy outcomes by outcome type, among other things.[35] BJS officials told us that they expect to publish the findings from the survey in 2025.

According to BJS, these data collection efforts will likely face some limitations. For example, BJS does not anticipate being able to report on maternal health outcomes, including maternal mortality and morbidity. BJS does not anticipate being able to report on individual-level outcome data because its feasibility study found that doing so significantly increases the burden for facilities to respond. For example, according to BJS officials, some facilities told them that doing so would require them to obtain permission from these women to disclose their private information. BJS officials noted that BJS will consider engaging in additional work to better understand these limitations and work with facilities on ways to mitigate them.

All Selected Facilities Reported Collecting Information on Incarcerated Pregnant Women, but the Data Are Limited

Officials representing all nine state prisons and nine local jails we spoke with reported collecting some information on incarcerated pregnant women. Representatives from all of these facilities reported maintaining health data in electronic health records, and officials representing five of nine prisons and three of nine jails reported maintaining custody-relevant information in case management systems.[36] Officials from the prisons and jails we met with generally reported that they collect information about pregnant women during the intake process—such as pregnancy status at admission—and medical providers update electronic health records as they provide care—such as documenting an individual’s delivery date and delivery method.

Officials representing all nine of the prisons we met with said they share pregnancy information with their state DOC. However, none of the prisons, jails, and state or local DOCs we spoke with told us they routinely report this information to DOJ or HHS, nor, according to DOJ and HHS officials, are they generally required to do so.[37] Further, officials representing two of the nine prisons and four of the nine jails we met with share some information with professional organizations, such as the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, to obtain or maintain accreditation. As discussed earlier, these accreditation processes are voluntary, and not all facilities report to these entities.

Prison and jail officials we spoke to also reported challenges to collecting, analyzing, and reporting the data on incarcerated pregnant women. These challenges are related to the personal experiences of incarcerated women, privacy issues, and technology limitations. BJS reported similar challenges in its 2024 maternal health feasibility study report.

Officials’ Perspectives of Personal Experiences of Incarcerated Women

According to officials representing three of the nine prisons and four of the nine jails, it can be difficult to collect complete health information about the pregnant women due to some of the personal experiences of this population. For example, some of these women may not have had access to health care prior to incarceration—often due to lack of resources—and therefore may not have community health records that could provide information about a woman’s health history. According to officials representing four of the nine prisons and three of the nine jails, for some pregnant women, the care they receive while incarcerated may be their first encounter with quality health care during their pregnancy. For women who were able to access health care prior to incarceration, officials representing one prison reported that those community health records may be difficult to obtain. Additionally, officials representing two of the nine prisons and three of the nine jails told us that some women may be reluctant to share their health information or may not report accurate information to corrections staff and health care providers at the facilities.

Further, according to officials representing three of the nine jails, women are not typically incarcerated in jails for their entire pregnancies, which makes it difficult to collect information on pregnancy and maternal health outcomes. For example, officials at one jail told us that the average length of stay at their facility is 59 days, while officials at another jail said that the average length of stay at their facility is 193 days. As such, women may be incarcerated at different points of their pregnancies for different lengths of time.

Moreover, officials representing three of the nine prisons reported that when women are transferred from jails to prisons, their health records may not be transferred in a timely manner—or at all. According to officials representing seven of the eight state DOCs we spoke with, they have little to no authority over jail facilities in their state, and officials from one of these DOCs told us they may not receive medical records for women transferring from jails in a timely manner. In addition, local, rather than state, authorities typically operate jails, meaning individual jails may maintain their data differently.

Privacy Issues

The prison and jail officials we spoke with told us they generally collect data related to pregnancy in electronic health records, and these data are generally considered protected health information. For example, officials representing one of the nine prisons told us they must balance the privacy required for sensitive medical information with the need to share information with custody staff. To protect sensitive medical information, medical staff may not share all information about a woman’s pregnancy, such as the diagnosis of a high-risk factor, with custody staff. In addition, BJS reported in its maternal health feasibility study report that officials representing the prisons and jails it interviewed discussed privacy concerns related to the health data they can share.[38]

Technology Limitations

Officials representing two of the nine prisons and four of the nine jails reported that data systems sometimes do not connect to one another, or data cannot be easily extracted for analysis. For example, officials representing one of these prisons and three of these jails reported that hospital data systems may not share data with facility data systems, or facility custody data systems may not share data with facility health record data systems. Additionally, staff from some prisons and jails may have to manually extract data from individual health records to conduct analyses.

Selected Studies from 2013 through 2023 Provide Insights on Characteristics of Incarcerated Pregnant Women in State Prisons and Local Jails

We reviewed relevant literature about incarcerated pregnant women in state prisons and local jails, including 12 studies that provided limited information on this population. These 12 studies provided limited data on this population, including the number and prevalence of pregnancy in studied facilities, demographic characteristics of pregnant women, pregnancy outcomes, and maternal health outcomes. None of the studies described in these articles were nationally representative or generalizable. Table 1 provides information we collected from these articles about incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women in state prisons. For a list of all the articles we reviewed about pregnant women incarcerated in state prisons and local jails, see appendix II.

|

Demographics |

|

In a study of 58 women who gave birth and were participating in a pregnancy and parenting support group while incarcerated at one midwestern women’s state prison, 42 percent (23) were White, 13 percent (seven) were Black or African American, 26 percent (14) were American Indian, 2 percent (one) were Hispanic or Latina, 4 percent (two) were Asian, and 13 percent (seven) identified as having more than one racial-ethnic identity.a |

|

Of the 117 women who gave birth while incarcerated at one Minnesota state prison between 2007 and 2016, 57.7 percent (64) were White, 22.5 percent (25) were African American or Black, 14.4 percent (16) were American Indian or Alaska Native, 4.5 percent (five) were Asian, and 0.9 percent (one) were Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Additionally, 93.7 percent (104) were non-Hispanic, and 6.3 percent (seven) were Hispanic or Latina.b |

|

Of the 179 pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD) incarcerated in a North Carolina state women’s prison from 2016 to 2018, 62.4 percent (111) of the women in the sample were Non-White, and 37.6 percent (67) were White.c |

|

Prevalence of pregnancy |

|

A total of 1,224 pregnant women were admitted to the 22 state prisons participating in the Pregnancy in Prisons Statistics (PIPS) study during a 12-month study period (2016—2017). Pregnant women represented 3.8 percent of admitted women to participating state prisons in December 2016.d |

|

Pregnancy outcomes |

|

Of the 1,224 pregnant women admitted to state prisons participating in the PIPS study, 742 pregnancies ended during custody. Of these, 92 percent (685) ended in live births, 1.2 percent (nine) in abortions, 6 percent (42) in miscarriages, 0.5 percent (four) in stillbirths, and 0.3 percent (two) in ectopic pregnancies.e Of the 685 live births in these state prisons, 68 percent (464) were vaginal deliveries and 32 percent (221) were Cesarean deliveries. Among live births, 6 percent (39) were preterm and 0.3 percent were very early preterm.f |

|

There were 348 women who gave birth while incarcerated in a subset of 11 state prisons participating in the PIPS study that reported 6 months of lactation frequency data.g |

|

Researchers identified records of 114 births for women incarcerated at a large midwestern state prison from May 2013 to December 2018.h |

|

In a study of 58 women who gave birth and were participating in a pregnancy and parenting support group while incarcerated at one midwestern women’s state prison, women in the sample delivered at 39.3 weeks gestation on average, with a range of 33.1 to 43.1 weeks.i |

|

Of the 117 recorded births of single infants that occurred among women aged 18 and over incarcerated at one Minnesota state prison between 2007 and 2016, 76.9 percent (90) delivered vaginally, and 23.1 percent (27) had Cesarean sections. Medical records indicated that 4.5 percent (five) of infants had a low birthweight, 6.0 percent (seven) of births were preterm, and 6.0 percent (seven) of infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit.j |

|

Maternal health outcomes |

|

Researchers assessed depressive symptoms in 58 women who gave birth while in correctional custody and were participating in a pregnancy and parenting support group at one midwestern women’s state prison and found that 33 percent (19) exhibited minimal depression, 33 percent (19) exhibited mild depression, 21 percent (12) exhibited moderate depression, 10 percent (six) exhibited moderately severe depression, and 3 percent (2) exhibited severe depression. In addition, 9 percent (five) endorsed suicidal or self-injurious ideation at least once.k |

|

Health characteristics |

|

Twenty state prisons participated in a 6-month supplemental reporting period of the PIPS study. Among these prisons, 117 pregnant women with OUD were admitted. This represented 26 percent of the total 445 women admitted to these participating state prisons. Of the 117 pregnant women with OUD, 31 percent (36) underwent detoxification. Of these 36 women, 86 percent (31) underwent detoxification with medication. Of the 117 women, 69 percent (81) received medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), which were initiated in custody or continued from the community.l |

|

Of the 179 pregnant women with OUD incarcerated in a North Carolina state women’s prison from 2016 to 2018, 16.2 percent (29) reported heroin use and 85.5 percent (153) used other opioids prior to incarceration. Additionally, 29.6 percent (53) of women had received MOUD prior to incarceration.m |

|

In a study of 58 women who gave birth and were participating in a pregnancy and parenting support group while incarcerated at one midwestern women’s state prison, 68 percent (32) had a previous mental health diagnosis.n |

Source: GAO analysis of cited studies. | GAO‑25‑106404

Note: Regarding the demographic information provided in these studies, the percentages do not account for differences in the sizes of the populations by race and ethnicity. Further, the studies may have used different terms and methods for analyzing race and ethnicity demographic data.

aMariann A. Howland et al., “Depressive Symptoms among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Prison,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, vol. 66, no. 4 (2021): 494-502.

bRebecca Shlafer et al., “Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes Among Incarcerated Women Who Gave Birth in Custody,” Birth, vol. 48 (2021): 122-131. 58 of the 117 births recorded in this study occurred prior to 2013.

cAndrea K. Knittel et al., “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy in a State Women’s Prison Facility,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 214 (2020): 1-5.

dCamille Kramer et al., “Shackling and Pregnancy Care Policies in US Prisons and Jails,” Maternal and Child Health Journal, vol. 27 (2023): 186-196; Carolyn Sufrin, et al. “Abortion Access for Incarcerated People: Incidence of Abortion and Policies at U.S. Prisons and Jails,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 138, no. 3 (2021): 330-337; Carolyn Sufrin, et al. “Pregnancy Outcomes in US Prisons, 2016–2017” AJHP Open-Themed Research, vol. 109, no. 5 (2019): 799-805. Researchers associated with the Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People research group at the John Hopkins School of Medicine conducted the PIPS study. PIPS includes data on pregnancy outcomes from 26 Department of Justice Bureau of Prisons facilities, 22 state prison systems, and six county jails. Study prisons included 86 percent of all women in Bureau of Prisons facilities and 53 percent of all women in state prisons in 2016. Participating prisons and jails reported aggregate data to researchers on a monthly basis for 1 year (2016 to 2017).

eSufrin et al., “Abortion Access for Incarcerated People: Incidence of Abortion and Policies at U.S. Prisons and Jails.”

fSufrin et al., “Pregnancy Outcomes in US Prisons, 2016-2017.”

gIfeyinwa V. Asiodu, Lauren Beal, and Carolyn Sufrin, “Breastfeeding in Incarcerated Settings in the United States: A National Survey of Frequency and Policies,” Breastfeeding Medicine, vol. 16, no. 9 (2021): 710-716. For 6 months, 11 state prisons completed an optional, supplemental, monthly reporting form for PIPS on the numbers of women who were lactating.

hVirginia E. Pendelton et al., “Caregiving Arrangement and Caregiver Well-being when Infants are Born to Mothers in Prison,” Journal of Child and Family Studies, vol. 31 (2022): 1894-1907.

iHowland et al., “Depressive Symptoms among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Prison.” The average gestation period is about 40 weeks.

jShlafer et al., “Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes Among Incarcerated Women Who Gave Birth in Custody.”

kHowland et al., “Depressive Symptoms among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Prison.” Researchers collected data as part of an ongoing evaluation of a prison-based pregnancy and parenting support program at one women’s state prison. At prenatal and postpartum visits with their doula, women completed a patient health questionnaire to measure their depressive symptom severity.

lCarolyn Sufrin et al., “Opioid Use Disorder Incidence and Treatment Among Incarcerated Pregnant People in the U.S.: Results from a National Surveillance Study,” Addiction, vol. 115, no.11 (2020): 2057-2065. For 6 months, 20 prisons completed an optional, supplemental monthly reporting form for PIPS on numbers of pregnant people with OUD admitted and their treatment. The prisons represented 38 percent of women in state prisons.

mKnittel et al., “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy in a State Women’s Prison Facility.”

nHowland et al., “Depressive Symptoms among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Prison.”

Additionally, table 2 provides information we collected from these articles about incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women in local jails.

|

Demographics |

|

In a study of 241 pregnant women incarcerated in one of seven jails in a southeastern state between August 1, 2012, and October 1, 2016, 46.5 percent (112) were White, 46.1 percent (111) were Black or African American, and 6.2 percent (15) were of another race. 22.4 percent (54) of the women reported being homeless during the past year.a |

|

Prevalence of pregnancy |

|

A total of 1,622 pregnant women were admitted to local jails participating in the Pregnancy in Prisons Statistics (PIPS) study during a 12-month study period (2016—2017). Pregnant women represented 3.2 percent of admitted women to participating jails in December 2016.b |

|

Pregnancy outcomes |

|

A total of 224 pregnancies in local jails participating in the PIPS study ended during custody. Of these, 64 percent (144) ended in live births, 18 percent (41) in miscarriages, 15 percent (33) in abortions, 1.8 percent (four) in ectopic pregnancies, and 0.9 percent (two) in still births. Of the 144 live births, 32 percent (46) were Cesarean deliveries and 8.3 percent (12) were preterm births.c |

|

There were 77 women who gave birth while incarcerated at a subset of five local jails participating in the PIPS study that reported 6 months of lactation frequency data and supported lactation.d |

|

Maternal health outcomes |

|

At all six participating local jails, there were no maternal deaths in the PIPS study.e |

|

Health characteristics |

|

Fifty pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD) were admitted to four local jails participating in optional, 6-month supplemental reporting about OUD for the PIPS study. This represented 14 percent of the total 353 women admitted to these participating local jails. Seventy-three percent (37) of the pregnant women with OUD received medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).f |

|

In a study of 27 pregnant women incarcerated at a local jail facility in a large midwestern county, 48.2 percent of study participants self-reported a mental health concern. Study participants reported previously receiving mental health treatment for depression (40.7 percent), anxiety (22.2 percent), physical abuse (18.5 percent), schizophrenia (11.1 percent), bipolar disorder (7.4 percent), and trauma (3.7 percent). Additionally, 55.6 percent screened positive for substance use disorder, 44.4 percent received previous alcohol or drug treatment in their lifetime, and 18.5 percent received previous alcohol or drug treatment in the last year. Further, 55.5 percent of study participants reported co-occurring conditions; 25.9 percent of pregnant women screened reported potential challenges with physical health problems, mental health treatment history, and substance use problems.g |

|

In a study of 241 pregnant women incarcerated in one of seven jails in a southeastern state between August 1, 2012, and October 1, 2016, 40.2 percent (97) of the women reported receiving a mood or psychiatric disorder diagnosis. Additionally, 52.7 percent (127) of the women reported illegal drug use in the past 2 years, and 12.4 percent (30) reported methadone use in the past 6 months.h |

Source: GAO analysis of cited studies. | GAO‑25‑106404

Note: Regarding the demographic information provided in these studies, the percentages do not account for differences in the sizes of the populations by race and ethnicity. Further, the studies may have used different terms and methods for analyzing race and ethnicity demographic data.

aCaroline M. Kelsey, Morgan J. Thompson, and Danielle H. Dallaire, “Community-Based Service Requests and Utilization among Pregnant Women Incarcerated in Jail,” Psychological Services, vol. 17, no. 4 (2020): 393-404.

bCamille Kramer et al., “Shackling and Pregnancy Care Policies in US Prisons and Jails,” Maternal and Child Health Journal, vol. 27 (2023): 186-196; Carolyn Sufrin et al., “Abortion Access for Incarcerated People: Incidence of Abortion and Policies at U.S. Prisons and Jails,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 138, no. 3 (2021): 330-337. Researchers associated with the Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People research group at the John Hopkins School of Medicine conducted PIPS study. PIPS includes data on pregnancy outcomes from 26 Department of Justice Bureau of Prisons facilities, 22 state prison systems, and six county jails. Study jails accounted for about five percent of all women in local jails in 2016. Participating prisons and jails reported aggregate data to researchers on a monthly basis for 1 year (2016 to 2017).

cKramer et al., “Shackling and Pregnancy Care Policies in US Prisons and Jails.”; Sufrin, et al., “Abortion Access for Incarcerated People: Incidence of Abortion and Policies at U.S. Prisons and Jails.”; Carolyn Sufrin, et al., “Pregnancy Prevalence and Outcomes in U.S. Jails,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 135, no. 5 (2020): 1177-1183.

dIfeyinwa V. Asiodu, Lauren Beal, and Carolyn Sufrin, “Breastfeeding in Incarcerated Settings in the United States: A National Survey of Frequency and Policies,” Breastfeeding Medicine, vol. 16, no. 9 (2021): 710-716. For 6 months, five local jails completed an optional, supplemental, monthly reporting form for PIPS on the numbers of women who were lactating.

eSufrin et al., “Pregnancy Prevalence and Outcomes in U.S. Jails.”

fCarolyn Sufrin et al., “Opioid Use Disorder Incidence and Treatment Among Incarcerated Pregnant People in the U.S.: Results from a National Surveillance Study,” Addiction, vol. 115, no. 11 (2020): 2057-2065. For 6 months, four prisons completed an optional, supplemental monthly reporting form for PIPS on numbers of pregnant people with OUD admitted and their treatment. The jails represented 2 percent of women in local jails.

gSusan J. Rose, and Thomas P. LeBel, “Confined to Obscurity: Health Challenges of Pregnant Women in Jail,” Health & Social Work, vol. 45, no. 3 (2020): 177-185. As part of a larger study of incarcerated mothers of minor children, women identified as pregnant were offered screening for substance use problems.

hKelsey, Thompson, and Dallaire, “Community-Based Service Requests and Utilization among Pregnant Women Incarcerated in Jail.”

HHS and DOJ Assistance Can Be Used to Support Maternal Health Care in State Prisons and Local Jails

Five HHS and Ten DOJ Grant Programs Could Be Used to Support Maternal Health Care

Both HHS and DOJ have grant programs that could be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails. HHS has five such grant programs.[39] Officials from HHS’s Administration for Children and Families (ACF) and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) told us that while their grant programs are not specifically designed for providing maternal health care in prisons and jails, award funds for five grant programs could be used for this purpose. For example, HRSA officials told us that recipients could use award funds from the Healthy Start Initiative program to enhance maternal health care in prisons and jails. The purpose of this program is to reduce rates of infant death, improve maternal health outcomes, and reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Appendix III provides more information about these five HHS grant programs.

DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs (OJP) has 10 grant programs that could be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails. OJP officials told us that while these grant programs are not specifically designed for providing maternal health care in prisons and jails, award funds could be used for this purpose. For example, OJP officials told us that recipients could use award funds from the Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Abuse Site-Based Program to enhance maternal health care in prisons and jails by planning, developing, and implementing comprehensive efforts that identify, respond to, treat, and support individuals impacted by the use and misuse of opioids, among other substances. Appendix III provides more information about these 10 DOJ grant programs.

In addition to available OJP grant programs, officials from OJP’s Bureau of Justice Assistance and BOP’s National Institute of Corrections told us they provide training and information resources online that may be useful to state prisons and local jails.[40] They can also provide technical assistance directly to prisons and jails upon request, such as guidance, assessment, and customized training.

Few State Prisons or Local Jails Received HHS or DOJ Federal Assistance

HHS officials told us some of its grant funds are being used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails. According to officials and grant documentation, at least 23 awards under the Healthy Start Initiative, Head Start and Early Head Start, and the Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant programs were used to support maternal health care in prisons and jails during fiscal years 2018 through 2023.[41] However, none of the 23 HHS grant recipients for fiscal years 2018 through 2023 were state departments of correction or prison or jail facilities. The recipients that used HHS award funds to provide services at these facilities were nongovernmental organizations or other government entities, such as state governments, child development agencies, and county departments of health. Examples of how recipients are using these grant programs are provided in the text box below. Appendix IV provides information about how HHS grant recipients are using all 23 grant awards to support maternal health care in prisons and jails.

|

Examples of Grant Award Funds Used to Support Maternal Health Care in State Prisons and Local Jails One Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Healthy Start Initiative recipient is using grant funds to provide medical care in a local jail, along with county jail staff. Grant funds help support a portion of a family medicine doctor’s salary and a full-time medical assistant who ensure the jail complies with the recommended prenatal visit schedule. One HHS Early Head Start recipient reported using grant funds to support its prison nursery, where eligible incarcerated mothers reside with their babies until the mother’s release from incarceration, up to 36 months. As part of this program, incarcerated mothers receive targeted learning opportunities to assist in building their parenting skills. |

Source: HHS grant information. | GAO‑25‑106404

DOJ officials were not aware of any of its grant funds being used to support maternal health care in state prisons or local jails during fiscal years 2018 through 2023. Additionally, based on a key word search of DOJ’s grants management systems, we did not identify any grant recipient that utilized funds for maternal health care in state prisons or local jails. Further, as of May 2024, officials from the Bureau of Justice Assistance and the National Institute of Corrections said that they did not receive any requests for technical assistance related to maternal health care for incarcerated pregnant women during fiscal years 2018 through 2023.

In interviews with officials representing selected prisons and jails, we found that they generally were unaware of HHS and DOJ assistance that could be used to support maternal health care in their facilities. For example, officials representing five of the nine prisons and six of the nine jails we met with were unaware of any available federal grants. When asked about what types of federal assistance would be useful, officials from seven prisons and four jails described how they would potentially use financial assistance. Officials representing one prison and one jail said they would construct specialized housing for pregnant and postpartum women. Officials representing four prisons also said they would use funds to develop additional services for postpartum women, such as a nursery or breastfeeding program.

Two of the five grant programs HHS officials told us could be used to support maternal health care in prisons and jails—Healthy Start Initiative and Head Start and Early Head Start—use grant solicitations, also known as notices of funding opportunity.[42] We reviewed a sample of five available HHS grant solicitations, and none mentioned providing maternal health care in state prisons or local jails as an allowable use of funds.[43]

HRSA officials stated that they do not include information about how grant funds can be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails in their grant information because they only include the required elements found in law. This prevents grant applicants from misinterpreting the authorized uses of the grant awards. HRSA grant recipients determine how to use the funds they receive based on state and community needs, and thus may choose to support services in state prisons and local jails. In addition to solicitations, HRSA makes information about its grant programs available on its public website and disseminates newsletters to interested parties, among other things.

Similarly, ACF officials noted that they do not include information about how grant funds can be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails in their grant information because Head Start and Early Head Start programming can be delivered to a range of eligible families in a wide variety of settings. ACF officials also stated that they do not want to prescribe the physical location for the services or the children to be served. ACF officials noted that this allows organizations to design and implement programs that are the most responsive to the unique needs of the communities and populations they serve.

We reviewed available DOJ grant solicitations for the 10 grant programs that DOJ told us could be used to support maternal health care in prisons and jails. We found that from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, DOJ issued 39 solicitations for these 10 grant programs. Only four of the 39 solicitations mentioned that funds could be used to provide services to pregnant women in prisons or jails. This represented three of the 10 relevant grant programs. For example, the 2022 and 2023 solicitations for the Second Chance Act: Improving Substance Use Disorder Treatment and Recovery Outcomes for Adults in Reentry stated that grant funds can be used to provide family-based substance use disorder treatment programming for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women in prisons.

According to OJP officials, the primary purpose of its 10 grant programs is to enhance substance use and other behavioral health treatments and improve reentry outcomes for people leaving prisons and jails. OJP officials stated that they do not include information about how grant funds can be used to support maternal health care in state prisons and local jails in most of their grant information, such as solicitations for these programs, because grant recipients may only use the funds in that manner if doing so helps them meet the primary purpose of these programs. In addition, it is possible that maternal health care would not be an allowable use of funds for these programs; for example, if the award recipient did not specify it would use award funds to provide maternal health care in its approved award budget.

Further, Bureau of Justice Assistance and National Institute of Corrections officials noted that they market and distribute existing technical assistance and resources on their public websites and in stakeholder listservs. Bureau of Justice Assistance officials told us that both grant recipients and nonrecipients may request technical assistance. They allocate funding to training and technical assistance providers, such as research organizations and consulting agencies, and scope responses to requests to manage available funds. Additionally, National Institute of Corrections officials told us they are not able to broadly announce new technical assistance for maternal health care because they do not have funding available to support responding to requests for new technical assistance. Rather, they review requests to determine trends and patterns related to state and local requests. Occasionally, National Institute of Corrections advertises targeted technical assistance on specific topics in high demand from state and local requests, as allowed by available funding.

In addition to available assistance for providing maternal health care to incarcerated pregnant women in state prisons and local jails, HHS and DOJ have both committed other resources to addressing the maternal health crisis in alignment with the White House blueprint, including for incarcerated women. For example, HHS issued a report to Congress in July 2024 that described its efforts to address the maternal health crisis, including developing a framework to assess its progress.[44] HRSA resources also continue to support the use of doulas, among other actions that could enhance maternal health care for incarcerated pregnant women.

Further, BJS is taking action to learn more about the number and characteristics of incarcerated pregnant women in prisons and jails. In its maternal health feasibility study report, BJS noted that collecting data on incarcerated pregnant women and learning more about the health services and accommodations provided is necessary to assess and address the health needs of incarcerated women related to pregnancy and childbirth.

Selected Prisons and Jails Reported Providing Care for Incarcerated Pregnant Women that Aligned with Guidance, State Laws, and Policies

Selected Prisons and Jails Reported Following Recommended Guidance to Provide Care for Incarcerated Pregnant Women

Officials representing eight of the nine prisons and eight of the nine jails we met with reported following guidance from one or more professional organizations on providing maternal health care to incarcerated women.[45] These organizations include the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Correctional Association, and the National Commission on Correctional Health Care.

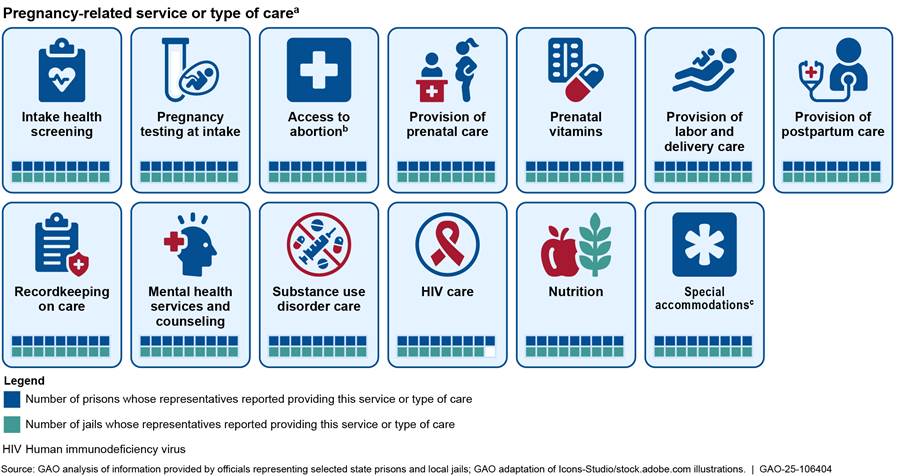

We also asked officials representing the nine prisons and nine jails we met with about the services and types of care that they provide for pregnant and postpartum women in their facilities, regardless of whether they reported following guidance from one or more professional organizations.[46] For example, we asked about pregnancy testing, postpartum care, and substance use disorder care. Figure 2 shows how many prisons and jails reported providing each service or type of care. See appendix V for additional information about the services that state prisons and local jails reported providing.

Note: We spoke with officials representing nine prisons and nine jails in a nongeneralizable sample of states to discuss maternal health care in their facilities. To develop our sample, we considered state rates and counts of incarcerated females and state maternal mortality rates, as well as racial and ethnic data available for the population under the jurisdiction of state or federal correctional authorities. We also considered whether we were aware of any federal funding serving this population, diversity of geographic location, and the availability of nursery and doula programs in prison or jail facilities, among other factors. Doulas are trained professionals who provide physical, educational, and emotional support and advocate for mothers before, during, and shortly after childbirth.

aWe identified the type of service or care the nine prisons and nine jails we spoke with reported providing based on information obtained during interviews with officials representing these facilities or documentation from these facilities. If a facility is excluded from the count of prisons or jails providing a type of service or care, this does not necessarily mean that the facility does not provide that type of service or care. Instead, it may mean that officials did not mention that type of service or care to us, even though the facility they represent provides it. Additionally, we did not independently verify the availability or provision of services and types of care that officials or facility documentation identified as available.

bAccess to abortion services is based on what officials reported to us, which may mean that the facility provides access to abortion within the context of any applicable state laws. Officials made these statements as of the dates of our interviews, and state laws and facility policies may have changed following our interviews.

cSpecial accommodations may include housing (such as lower bunk assignments), adjusted work, activity, or programming assignments, and special clothing.

Although state prisons and local jails are not required to follow guidance from professional organizations, several of the services and types of care that officials described providing aligned with standards from ACOG’s 2021 committee opinion on reproductive health care for incarcerated pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant individuals.[47] For example, ACOG recommends assessing all women of child-bearing age for pregnancy, including by offering pregnancy testing, and officials representing all nine prisons and nine jails we met with reported providing pregnancy testing. Additionally, ACOG recommends the provision of medications for opioid use disorder for pregnant women with opioid use disorder.[48] Officials representing seven of nine prisons and eight of nine jails reported that medications for opioid use disorder are available for pregnant women, and officials representing one other prison told us that they are starting a program to provide this treatment.

Officials representing the nine prisons and nine jails we met with reported providing some services and types of care in different ways. For example, the nutrition that pregnant women receive varied across facilities. Officials representing six of nine prisons and eight of nine jails reported providing supplemental calories or a pregnancy diet for pregnant women. Officials representing one of the other three prisons reported that a clinical dietician and medical providers assess each pregnant woman and jointly decide on appropriate nutrition. Additionally, officials representing another prison told us that all women at the facility receive additional calories because they receive the same portions as incarcerated men in the state, and a doctor can determine that a pregnant woman requires a different diet.[49] Finally, officials representing one jail reported that a nutritionist at the facility can request special diets for pregnant women.

Additionally, who provided maternal health care to pregnant and postpartum women varied across selected facilities. For example, officials representing six of nine prisons and five of nine jails reported that they provide care through a partnership with a hospital, health system, or government entity. Additionally, officials representing three of nine prisons and three of nine jails told us that they contract with a private company to provide medical care.[50]

Many of the pregnant and postpartum women we met with reported receiving several of the services outlined above.[51] For example, 18 of 19 women we met with in prisons and all eight women we met with in jails reported receiving prenatal vitamins and being assigned a lower bunk. Additionally, 18 of 19 women we met with in prisons and six of eight women we met with in jails told us that they received supplemental food. For more information about the personal experiences of pregnant and postpartum women in the prisons and jails we visited, see appendix VI.

Selected Prisons and Jails Reported Following Applicable State Laws and Policies

Officials representing eight of nine prisons and six of nine jails reported that they are subject to state laws requiring particular care for and treatment of incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women.[52] These laws cover topics such as the use of restraints, restrictive housing, and other topics related to the treatment of pregnant and postpartum women.

Restraints. Officials representing all nine prisons and nine jails told us that they prohibit or limit the use of restraints for pregnant and postpartum women based either on state law or policy, including policy from the facility, state or local DOC, or sheriff’s office.[53] While officials representing all prisons and jails reported that their facilities followed laws or policies prohibiting or limiting the use of restraints, variations in these laws and policies existed across states and facilities.

Officials representing five of nine prisons and six of nine jails reported that state law or policy restricts, not prohibits, the use of restraints on pregnant women. For example, officials representing two prisons and two jails told us that staff may use restraints on pregnant women in certain situations, including for safety, such as when a pregnant woman presents a serious risk of harm to herself and others. Officials representing two prisons and three jails indicated that in cases when staff restrain a pregnant woman, they must document the use of restraints, such as by reporting to an external oversight body. For example, officials representing one of these three jails explained that if custody staff use restraints on a pregnant woman, they must report this use to a statewide oversight body.

Officials representing six of nine prisons and five of nine jails reported that custody staff receive training or information about using restraints on pregnant and postpartum women. For example, officials representing one prison told us that the same state law that, among other things, limits the use of restraints on pregnant women also requires the state department of corrections to train staff on the law’s provisions. In addition, officials representing one of nine jails that we met with reported that they provide all pregnant women with laminated cards. In addition to other information, the cards include a list of their rights during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and recovery after delivery, including limitations on the use of restraints.

Restrictive housing. Officials representing three of nine prisons also told us that state law either prohibits or limits the use of restrictive housing for pregnant, and in one state, postpartum, women. For example, officials representing one of these prisons told us that placing pregnant women in restrictive housing requires approval from state department of corrections officials.

Other facilities reported policies that limit the placement of pregnant women in restrictive housing or that add precautions to placing pregnant women in this setting. Officials representing two of nine prisons reported that based on policy, they do not or generally do not place pregnant women in restrictive housing. Officials representing one of these facilities explained that staff may only place pregnant or postpartum women in restrictive housing if doctors determine that the woman has specific medical or mental health needs and would benefit from the placement. Additionally, officials representing one of nine jails reported that staff may not place a pregnant woman in restrictive housing, and officials representing two other jails reported that staff generally do not place pregnant women in restrictive housing. Further, officials representing four of nine jails told us that staff may place pregnant women in restrictive housing under certain circumstances. Officials representing three of these jails told us that medical staff must clear women for placement in restrictive housing.

Other topics related to the treatment of pregnant and postpartum women. Officials representing two prisons and two jails identified other state laws affecting the treatment of pregnant and postpartum women in their facilities. According to officials representing two prisons, state laws require 72 hours of bonding time for incarcerated women and their infants following delivery. Officials from one jail also reported that state law entitles incarcerated women to a support person during delivery.[54] Additionally, officials from another jail reported that state law requires the jail provide education on prenatal topics for pregnant women.

Selected Prisons and Jails Reported Providing Additional Programs and Resources to Support Maternal Health Care

In addition to the care and services that professional organizations recommend or that are required by state laws, officials representing several of the nine prisons and nine jails also reported other programs and resources that support maternal health care at these facilities. These programs include pregnancy or parenting classes, doula programs, nursery programs, and lactation programs.

Pregnancy or parenting classes. Officials representing five of nine prisons and three of nine jails reported that their facilities offer classes on pregnancy or parenting. For example, officials representing one jail told us about an adapted version of the CenteringPregnancy program that medical staff and staff from the facility’s doula program provide for pregnant women at the facility.[55] During CenteringPregnancy sessions, medical providers facilitate discussions and lead activities for pregnant and postpartum women related to topics including nutrition, stress management, labor and delivery, and infant care. Additionally, officials representing one prison described the facility’s pregnancy and parenting programs, which incarcerated women lead for their peers. These classes cover topics that include having a healthy pregnancy, managing successful family visits, and improving communication skills with their children.

Doula programs. Officials representing one of nine prisons and four of nine jails reported that they provide incarcerated women the option of working with a doula. Five of the six pregnant and postpartum women we met with at a facility with a doula program reported working with a doula. Three of these five women assessed their experiences, and all three told us that they found the program helpful and appreciated the support they received from their doulas. Including those facilities with a doula program, officials representing six of nine prisons and five of nine jails reported that women may have a support person present during delivery.[56] Officials representing two of these prisons and two of these jails reported that the support person must receive authorization to act in this capacity, such as by undergoing a security review.

Nursery programs. Officials representing three of nine prisons and one of nine jails told us that their facilities operate nursery programs where eligible women can reside with their babies following delivery.[57] According to officials representing the three prisons and one jail with nursery programs, participants have access to several types of programming, which may include parenting and child development classes, educational opportunities, substance use disorder treatment, and life skills, such as anger management. Additionally, officials from the three prisons that operate nursery programs reported that program participants enroll in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children to receive financial assistance for groceries as part of the program.

According to officials representing all four facilities with nursery programs, participants have access to reentry services.[58] Some of these services are specific to those participating in the nursery program. For example, officials from one facility reported that participants receive equipment, such as car seats to take home with them upon release from the facility. Additionally, officials from another program reported that participants can also receive services following their release, including home visits and referrals to community support.

Lactation programs. Some facilities offer programs that allow postpartum women to continue lactation following separation from their babies, when a nursery program is not available at a facility or a woman is not eligible to participate. Officials representing two of nine prisons and three of nine jails reported that postpartum women can express milk for pick-up and delivery to their infants. Additionally, officials representing one prison and three jails told us that they allow postpartum women to express milk but did not state whether they allow pick-up. Further, officials representing one prison and one jail told us that some postpartum women, such as those releasing within 6 months or those whose doctors request it, are permitted to express milk while others are not. Finally, officials representing two prisons and one jail told us that they are in the process of developing a program that would allow postpartum women to express milk for delivery to their infants.

Challenges and Opportunities Exist for Providing Maternal Health Care in State Prisons and Local Jails

Reported Challenges Include Personal Experiences of the Incarcerated Population, Inconsistent Services, and Other Logistical Issues

Officials representing several of the nine prisons and nine jails we met with, as well as officials from some of the five nongovernmental organizations (NGO) we met with, identified various challenges to providing maternal health care to incarcerated women.[59] We also reviewed 33 articles that described such challenges and opportunities to address them.[60] The challenges that these officials and articles frequently cited included those related to the personal experiences of incarcerated pregnant women, inconsistent access to services across facilities, and logistical challenges.

Identified Challenges Related to Personal Experiences of Incarcerated Pregnant Women

Officials representing several prisons and jails, as well as articles we reviewed, identified various challenges related to the personal experiences of incarcerated pregnant women. These challenges included stress and anxiety, the prevalence of other health conditions among this population, and differences in the care that these women received prior to entering the facility.

Stress and anxiety. Officials representing four of nine prisons and three of nine jails told us that stress from the correctional environment, isolation from loved ones, or pending separation from their infants can cause increased anxiety or frustration or complicate the provision of maternal health care for pregnant women. For example, officials representing one prison reported that women may seek to postpone upcoming inductions if they have not finalized placements for their infants. Nine of the 33 articles we reviewed also described the stress that pregnant women may experience while incarcerated, and six of these articles explained how this stress can negatively impact the health of these women or their infants.

Other health conditions. Officials representing four of nine prisons and four of nine jails reported that pregnant women in their facilities often have other health conditions, such as mental health concerns or substance use disorder, that can complicate their pregnancies and how facilities provide maternal health care. For example, officials representing one prison told us that almost every woman in their care has experienced trauma, which may result in hesitancy to accept care at the facility. Eighteen of the 33 articles we reviewed on challenges and opportunities related to providing care to incarcerated pregnant women also indicated that many of these women have high rates of other health conditions. Nine of these articles noted that incarcerated pregnant women have often experienced trauma, and six of these articles connect this trauma to pregnancy complications, poor health generally, or unique medical needs for these women.

Differences in care prior to entering the facility. Officials representing four of nine prisons reported that by the time pregnant women enter their facilities and staff begin to provide care for them, they have received different quality and types of maternal health care in previous facilities or in their communities. Officials representing three of these prisons explained that pregnant women at their facilities may not have received any care prior to their arrival, and officials representing one of these prisons stated that this delay may result in more progressed medical complications by the time the women receive care. Additionally, six of the 33 articles we reviewed described how pregnant women arriving at a prison or jail may have had limited access to health care prior to incarceration.

Inconsistent Access to Services