DEFENSE COMMAND AND CONTROL

Further Progress Hinges on Establishing a Comprehensive Framework

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106454. For more information, contact Travis J. Masters at masterst@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106454, a report to congressional committees

Further Progress Hinges on Establishing a Comprehensive Framework

Why GAO Did This Study

Military commanders need to quickly make informed decisions in battle. They rely on DOD systems to transform vast amounts of data into actionable information. DOD established the CJADC2 effort in 2019 to address these needs across domains. CJADC2 is not itself a system but is a way to use data and analytics to make and communicate better decisions in battle.

A House report includes a provision for GAO to review CJADC2 efforts. GAO (1) identifies how DOD defines its concept of CJADC2 and tracks systems, progress, and investments; and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD is positioned to improve command and control data sharing among existing systems and address challenges to developing new data- sharing solutions moving forward.

GAO analyzed policies, planning documents, and briefings related to DOD’s goals for CJADC2 and GAO reviewed documents on service-level CJADC2 efforts. GAO interviewed, among others, officials from DOD, the military services, all 11 combatant commands, and the CJADC2 cross functional team.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that DOD (1) develop a framework for CJADC2 that helps guide investments and measures progress; (2) devise a mechanism for sharing lessons learned; and (3) identify and address key challenges in achieving its CJADC2 goals. DOD concurred with two and partially concurred with one of GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

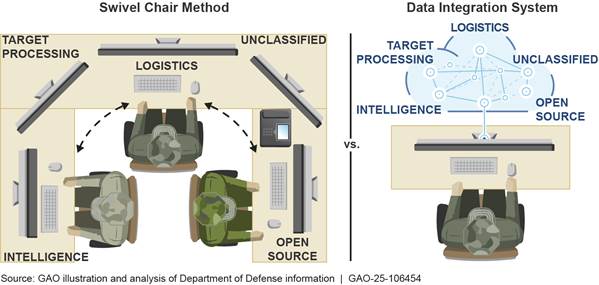

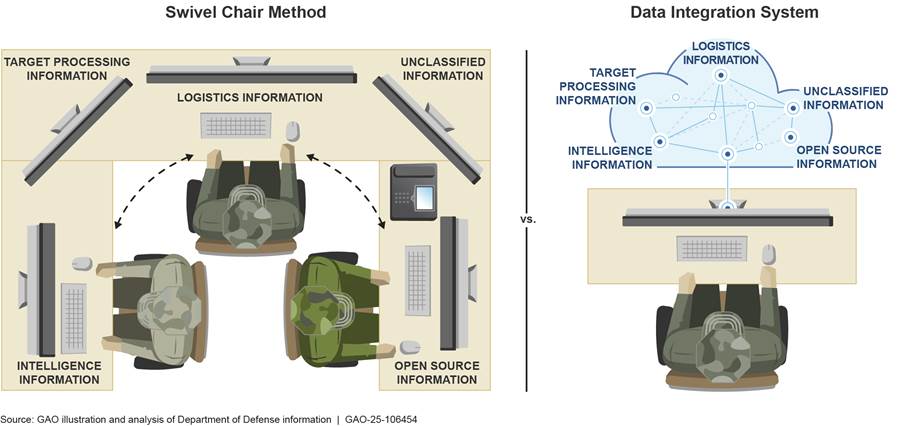

Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) is a Department of Defense (DOD) concept aimed at improving command and control by connecting selected U.S. assets across space, air, land, sea, and cyberspace domains. CJADC2 also aims to establish connections with international partners. DOD expects that, while difficult, pursuing CJADC2 will enable key decision makers to share and use data to perform command and control operations more quickly and easily. For example, CJADC2 would support a transition from a model where an analyst receives inputs and manually enters data from different systems—referred to as “swivel chair” analysis—to a model where all data is integrated.

DOD has attempted to define and guide CJADC2 efforts since its inception in 2019. However, it has yet to build a framework that can guide CJADC2-related investments across DOD or track progress toward its goals. As the CJADC2 concept has taken shape, military departments and other DOD entities have concurrently pursued their own independent data integration capabilities. GAO has previously found that establishing measurable goals and then measuring progress against these goals is critical for organizations. In the absence of clear direction, warfighting entities will continue to pursue their command and control projects largely in isolation, which will likely result in achieving CJADC2 much more slowly and inefficiently, if at all.

DOD is conducting activities aimed at demonstrating selected capabilities, but there is limited awareness of experimentation lessons learned that could lead to duplicative efforts and slower progress toward CJADC2 goals. Further, GAO found several critical challenges to achieving CJADC2 that DOD has yet to formally identify and address. For example, overly restrictive data classification is a significant hindrance to sharing command and control data. Further, officials GAO spoke with were not aware of an entity working on a solution to this or several other critical challenges. CJADC2 leadership told GAO that addressing these challenges was beyond their purview. Without identifying and addressing key challenges, DOD’s progress toward its CJADC2 objectives will remain limited.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ABMS |

Advanced Battle Management System |

|

API |

application programming interface |

|

CDAO |

Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office |

|

CFT |

Cross-Functional Team |

|

CJADC2 |

Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control |

|

CPM DOD |

capability portfolio management Department of Defense |

|

GIDE |

Global Information Dominance Experiment |

|

IC |

Intelligence Community |

|

ICD |

initial capabilities document |

|

JADC2 |

Joint All-Domain Command and Control |

|

OPEN DAGIR |

Open Data Applications Government-owned Interoperable Repositories |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 8, 2025

Congressional Committees

Military commanders need a real-time, complete, and high-quality battlespace picture to quickly make informed decisions, take direct actions, and assess a high volume of potential targets. Achieving success in future conflicts will require warfighters to quickly transform vast amounts of data into actionable information. The United States faces a complex array of threats to national security that continue to evolve as potential adversaries develop militarily. Adversaries seek to undermine the Department of Defense’s (DOD) strategic and operational strengths by impeding command and control capabilities. Thus, maintaining information and decision advantage is one of DOD’s top priorities.

While DOD recognizes that its systems need to operate in more complex battle environments that demand greater connectivity, its efforts to connect systems or build unified networks have often been unsuccessful.[1] In the past, when DOD acquired weapons systems, it largely prioritized optimizing individual system capabilities over ensuring connectivity, interoperability, and compatibility across systems. In an effort to identify, execute, and monitor operations across all domains—air, sea, land, space, and cyberspace—more effectively, DOD is now moving toward a long-term concept for sharing and using warfighting data across systems and organizations. DOD outlined the overall goals for the effort—then named Joint All-Domain Command and Control—in 2019 and established a team to oversee its implementation in 2020. In 2023, DOD expanded its original concept to reflect the importance of sharing data with international partner nations and renamed it Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2).

DOD emphasizes that CJADC2 is not a single weapon system acquisition program but is instead a concept intended to guide investments in modernizing and upgrading current systems, as well as developing and acquiring new systems. This concept aims to ensure they have the capabilities needed to succeed in future warfighting environments. DOD expects those future environments to require warfighters across all domains to handle increasing volumes of data and act faster than their adversaries. DOD requested over $1.4 billion for CJADC2 activities in its fiscal year 2025 budget request.

The House Armed Services Committee Report accompanying a bill for the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for GAO to review DOD’s CJADC2 efforts.[2] Our review (1) identifies how DOD has defined its concept of CJADC2 and tracks systems, progress, and investments; and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD is positioned to improve command and control data sharing among existing systems and address critical obstacles to developing new data-sharing solutions moving forward.

To identify how DOD has defined its concept of CJADC2 and tracks systems, progress, and investments for CJADC2, we reviewed policies, planning documents, implementation guidance, information papers, and overview briefings, including both classified and unclassified documents. We reviewed these documents to identify the goals of CJADC2, the CJADC2 governance structure, and the roles and responsibilities of CJADC2 officials. We conducted a content analysis of CJADC2 Cross-Functional Team briefing documents to identify and characterize DOD leadership descriptions for the CJADC2 concept. We reviewed the CJADC2 Capstone Initial Capabilities Document and used a content analysis to identify and outline CJADC2 examples of capability requirements for military entities. We also reviewed documents related to each military service’s contribution to CJADC2, including the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS), the Navy’s Project Overmatch, and the Army’s Project Convergence.[3] Further, we reviewed CJADC2 briefings and planning documents to identify and describe combatant command data-sharing efforts.

In addition to our document reviews, we met with officials from DOD Joint Staff—including the CJADC2 Cross Functional Team—and the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office (CDAO) to further understand CJADC2. We met with officials from the military services including the Air Force, Army, Navy, and the U.S. Marine Corps to discuss their activities related to CJADC2. In addition, we met with officials from all 11 combatant commands—DOD’s operational commanders—to assess their understanding of DOD’s CJADC2 goals and plans and where their organizations fit into them.

To determine the extent to which DOD is positioned to improve data sharing for existing systems and address critical obstacles to developing new data-sharing solutions, we reviewed planning and execution documentation from the CDAO, CJADC2 Cross-Functional Team, and military departments. We reviewed documentation pertaining to the CDAO’s Global Information Dominance Experiment (GIDE) event series. We identified CJADC2 as DOD’s primary concept to providing improved command and control capabilities for the joint force. We met with officials from the CDAO and military services as well as the Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps—which established its own experimentation series—to discuss command and control data-sharing efforts they have ongoing and the extent to which lessons learned from these efforts are shared to the larger DOD community. In addition, we assessed the extent to which DOD’s CJADC2 activities align with the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[4]

To identify the extent to which DOD is addressing critical obstacles to developing data sharing, we reviewed key CJADC2 planning documents establishing roles and responsibilities, such as the CJADC2 Cross-Functional Team (CFT) Charter. We also reviewed DOD status briefings to congressional staff and met with CFT and CDAO officials to further understand how ongoing experiments align with larger CJADC2 goals articulated in DOD guidance documentation. We met with officials from military departments and all 11 combatant commands to understand how their efforts align with DOD’s CJADC2 goals and the challenges they faced regarding CJADC2 related efforts. We also leveraged our past work examining early CJADC2 plans and concepts.[5]

We conducted this performance audit from December 2022 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Command and control is the exercise of authority and direction by a commander over assigned forces in the accomplishment of the mission. CJADC2 is DOD’s long-term concept to connect and modernize command and control capabilities from various military departments and organizations. CJADC2 is intended to help share and analyze command and control information across multiple domains—which we refer to as multi-domain in this report—such as space, air, land, sea, and cyberspace domains.[6] DOD expects improved data sharing and analysis to allow decision-makers to identify, execute, and monitor operations more efficiently and effectively. The CJADC2 concept originated from growing concerns that most military units did not have access to sufficient data to identify and quickly act on a large volume of targets. Further, DOD was concerned that the military departments were continuing to develop unique capabilities that did not adequately consider the need to share increasingly large amounts of complex data across systems or organizations.

Command and Control

Command and control capabilities are fundamental to military operations. They enable quick, accurate decision-making, which helps commanders to communicate and act decisively before enemies can anticipate and react. Military commanders and doctrine identify effective command and control as a potential deciding factor in conflict. A key aspect of command and control is the collection and sharing of information to enable military commanders to make timely, strategic decisions; take tactical actions to meet mission goals; and counter threats. For example, targeting—the process of selecting and prioritizing targets and matching the appropriate response to them—is a command and control activity.[7] Command and control is not the same thing as battle management, which is a subset of command and control. DOD defines battle management as the management of activities in an operational environment based on commands, direction, and guidance.

DOD currently builds large operations centers to collect, assess, and distribute data necessary to enable command and control. Within these operations centers, DOD largely relies on inefficient “swivel chair” data collection and assessment processes. In these processes, data comes into the operations centers from multiple systems and on multiple displays.[8] Analysts then collect, assess, and package the data by manually entering and transferring them into yet another system. This data aggregation is necessary for many reasons—for example, data may be classified at different levels or have different structures and formats.

The swivel chair approach makes it more difficult for warfighters to make decisions at the scale and tempo needed to effectively accomplish their missions. In addition, according to DOD’s command and control modernization strategy, DOD organizations and services cannot effectively use data analytics or artificial intelligence tools to sort through the large volumes of data that come into these centers. If the data remain isolated, this could cause the U.S. to fall significantly behind other nations that have these capabilities. DOD is trying to pivot toward more automated, scalable decision-making tools, according to its command and control modernization strategy. Figure 1 depicts the differences between the two different approaches.

Figure 1: Swivel Chair Approach and Automated Approach to Collecting, Assessing, and Distributing Data

DOD’s ability to effectively gather and process large volumes of information in short time frames is dependent on improved and scalable technological capabilities. According to DOD, technical data collection, processing improvements, and data security protocols facilitate more automated decision-making. DOD identified technologies that it believes have the potential to improve data fusion and help overcome traditional data-sharing barriers such as stove-piped data flow that limits data discovery, and non-interoperable system interfaces. For example, artificial intelligence including machine learning is largely the ability of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, and is a key technology area that could potentially enable processing of large volumes of information quickly.[9] Another technology enabler, zero trust, is a network security strategy for verifying anything and anyone attempting to establish access to a system, network, or service outside or within a security perimeter. Among other things, zero trust can allow users with different permissions to securely access data they have permission to view.

Organizations that Generate and Use Command and Control Data

Several entities across DOD and the intelligence community

generate, use, and share command and control data. We discuss below key

organizations across DOD and the Intelligence Community who lead or are

stakeholders in CJADC2 efforts:

Entities Leading CJADC2 Efforts

· Office of the Secretary of Defense oversees policy development, planning, resource management and program evaluation for all of DOD. The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD(R&E)) is the principal advisor to the Secretary of Defense on DOD’s research, engineering, and technology development activities and programs. The Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office (CDAO)—created in 2022 by the Deputy Secretary of Defense—is the primary organization in the Office of the Secretary of Defense focused on CJADC2 experimentation and developing data services for the enterprise, among other things. In addition, the DOD Chief Information Officer is the principal staff assistant for information technology and is responsible for the DOD’s information enterprise supporting command and control.

· The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is the principal military advisor to the President, National Security Council, Homeland Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense.[10] The Joint Staff assists the Chairman in accomplishing their responsibilities and includes several directorates aligned by functional areas.[11] For example, the J6 Directorate supports the Chairman’s responsibilities for advancing command and control capabilities while the J3 Directorate provides guidance regarding current operations and plans.

· The CJADC2 Cross-Functional Team (CFT)—also established by the Deputy Secretary of Defense—is a group co-chaired by the Joint Staff J6 Directorate Deputy Director and CDAO that focuses on CJADC2 efforts.[12] The J6 Directorate establishes requirements associated with command, control, cyber, and communications capabilities. The Deputy Secretary of Defense chartered the CFT in January 2020 to coordinate CJADC2 efforts across DOD. The CFT includes membership representing Joint Staff, military services, and combatant commands, among others, as shown in figure 2. The Joint Staff also has directorates focused on operations, planning, intelligence, and logistics—all of which are critical to command and control. The team’s charter states that the team is responsible for optimizing joint solutions to command and control capability gaps, developing frameworks to guide capability development, and recommending resource allocations across the department.

DOD has used cross-functional teams in the past. GAO has previously reported on the usefulness of cross-functional teams in improving DOD business operations.[13]

Entities Generating and Using Command and Control Data

· DOD’s military departments—the Air Force, Army, and Navy—prepare and provide strategic, conventional, and special operations forces for military operations conducted by DOD. As we reported in January 2023, each military department is executing a command and control initiative focused on improving interoperability and information flow: these efforts are the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System, the Army’s Project Convergence, and the Navy’s Project Overmatch.[14]

· The Intelligence Community (IC) consists of 18 organizations, including the intelligence components of the five military services within DOD as well as the National Security Agency. These organizations gather, analyze, and produce the intelligence necessary to conduct foreign relations and national security activities. The IC operates across all domains and collects many different types of intelligence data. For example, signal intelligence data is derived from electronic signals and systems used by potential targets; and geospatial intelligence data consists of imagery, imagery intelligence, and geospatial information.

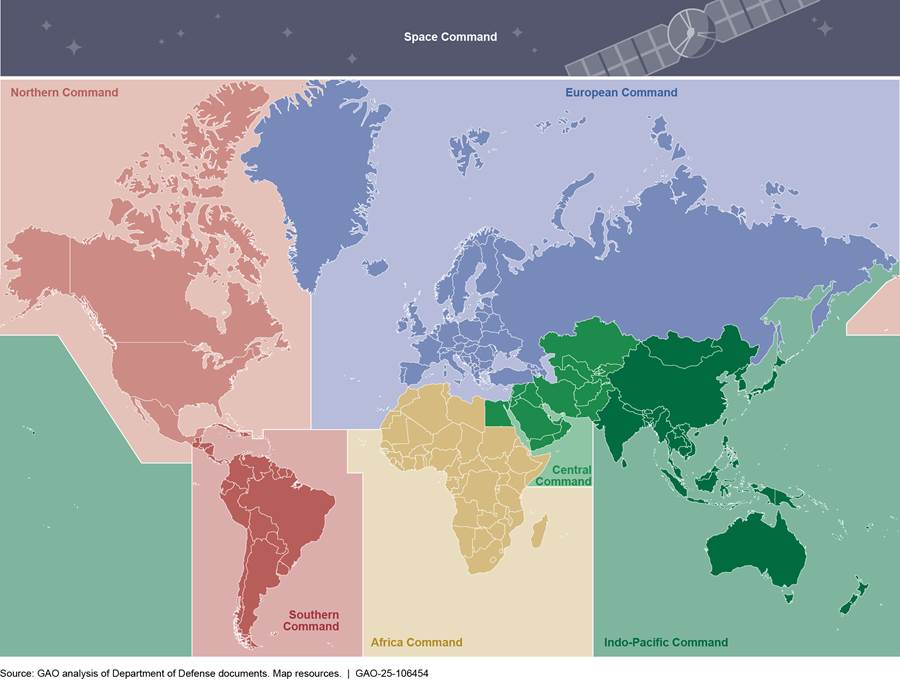

· DOD’s 11 unified combatant commands are responsible for conducting combat operations and providing direction for logistics so that warfighters have the capabilities needed to achieve mission success. Seven of the commands have responsibilities in regional areas of the world as shown in figure 3. The other four are combatant commands that operate across geographic boundaries and provide unique services. For example, the U.S. Transportation Command provides logistics and transport services around the world.

The CJADC2 Concept Continues to Evolve, but DOD Has Yet to Establish a Framework to Effectively Guide Investments and Track Progress

Originally conceived as connecting “every sensor-to-every shooter,” the CJADC2 concept continues to evolve. The most recent refinement was made through the publication of a CFT Initial Capabilities Document (ICD) in October 2024 that identified 12 functions—aligned across four categories—that systems under CJADC2 should be able to perform and that constitute core CJADC2 capabilities.[15] However, military departments and combatant commands continue to develop and acquire capabilities to meet their specific command and control needs. While these organizations need to buy systems to meet their needs, they cannot steer toward the CJADC2 vision without a common definition and framework. However, DOD has not yet established a framework to collectively guide its various command and control efforts and investments. Without such a framework it is difficult for DOD to track overall progress toward stated goals or measure success, and difficult for the organizations that are expected to contribute to CJADC2 to understand the extent to which their efforts and investments are moving in the right direction.

DOD’s CJADC2 Concept Continues to Evolve

DOD’s vision for CJADC2 to broadly improve Joint Force command and control capabilities continues to evolve and gain clarity. For example, originally, DOD promoted the concept of CJADC2 as connecting “every sensor-to-every shooter,” which generally referred to the goal of connecting weapon systems and sensors across DOD. A senior Air Force official we spoke with noted that this idea is now largely viewed as unrealistic and unhelpful. Since pivoting from this vision in recent years, DOD has struggled to provide a clear framework for what does or does not constitute a CJADC2 effort or investment. Table 1 provides examples of DOD’s descriptions of the CJADC2 concept as noted in selected CFT documents from 2020 to 2024.

Table 1: Descriptions of Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) in Selected Strategy and Briefing Documents from 2020 to 2024

|

CJADC2 is: |

CJADC2 is not: |

|

A warfighting functiona |

A noun or program of record with established cost, schedule, and performance benchmarks. |

|

The ability to connect distributed sensors, data, and effects from all domains to decision-makers from the tactical to the strategic at the scale, tempo, and timing required to accomplish commanding officer’s intent, agnostic to domains and platforms. |

An acquisition program focused on singular box, platform, or system. |

|

Warfighting capability to sense, make sense, and act, across all domains, and with partners, to deliver information quickly. |

A concept with a singular defined end-state. |

|

The art and science of decision-making to rapidly translate decisions into action, leveraging capabilities across all-domains and with mission partners to achieve operational and information advantage. |

Primarily sensor-to-shooter. |

Source: Summary of CJADC2 Cross-Functional Team briefing documents from 2020 to 2024. | GAO‑25‑106454

aCJADC2 officials and documentation refers to CJADC2 as a warfighting function. However, DOD doctrine identifies the seven joint functions common to joint operations as command and control, information, intelligence, fires, movement and maneuver, protection, and sustainment. See Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Warfighting, Joint Publication 1-01(Aug. 27, 2023)

In October 2024, the CFT finalized an ICD that established more clarity regarding the CJADC2 concept. CFT officials said that the ICD they sponsored—which categorizes and organizes requirements for the capabilities that CJADC2 is expected to deliver—gives CJADC2 stakeholders a high-level document that outlines a common CJADC2 framework. The ICD defines functional requirements for command and control data sharing and sets guidelines for the capabilities military services should prioritize.

The ICD identifies 12 functions—aligned across four required capability areas—that systems under CJADC2 should be able to provide and that constitute core CJADC2 capabilities. Table 2 identifies the functions and capabilities required outlined in the ICD.

Table 2: Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control Capabilities Required and Associated Functions

|

Capability Required 1: Provide situational awareness across all domains, military services, the intelligence community as well as allies and partners: 1. Ingest, process, store, analyze, visualize and orchestrate data between the intelligence community and Department of Defense. 2. The ability to capture, update, analyze and synthesize people-based resource estimates across a warfighting operational area and detect deviations from the people needed and the people available. 3. Maintain persistent tracking of targets across domain and time. |

|

Capability Required 2: Conduct planning in support of all joint functions, to include targeting, across all domains: 4. The ability to fuse Joint Force actions for decision-makers. 5. Generate relevant courses of action and select optimal courses. 6. Integrate plans and actions with higher headquarters and appropriate commanders. |

|

Capability Required 3: Provide force direction to and through key components: 7. Distribute control and components as well as manage authorities such as rules of engagement—which are the rules around what actions can be taken. 8. Decentralize component execution to disseminate mission-type orders to subordinate commanders and mission partners. 9. Monitor execution to determine accomplishments of objectives. |

|

Capability Required 4: Perform integrated operations with allies and mission partners: 10. Seamlessly and interoperably share data with allies and partners. 11. Integrate allied and mission partner effects into courses of action and recommendations. 12. Inform and provide direction to allied and mission partner commands and forces. |

Source: GAO analysis of CJADC2 initial capabilities document. | GAO‑25‑106454

In addition, the ICD represents a step forward in outlining connections with the Intelligence Community as well as including systems and processes expected to use data rather than simply sharing information. Military department officials we spoke with expressed support for the new ICD, which provides military services and combatant commands some general guidance about what capabilities they can pursue that align with CJADC2 goals.

The CJADC2 Cross-Functional Team Has Yet to Establish a Way to Guide Investments and Track Progress

While the ICD represents a clearer target than what existed before, DOD has yet to establish a framework to guide investments and track progress toward the target. In January 2020, the Deputy Secretary of Defense chartered the CJADC2 CFT to coordinate CJADC2 efforts across DOD. Over time, the CFT has developed several documents that are intended to guide stakeholder behavior and facilitate collaboration to realize a vision of CJADC2. The purpose of many of these documents is to outline the goals, strategies, and plans of the CJADC2 enterprise. Table 3 lists each CFT document, the date it was signed, and its stated purpose.

|

Document |

Date originally signed (date updated) |

Purpose |

|

Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) Strategy |

March 2022 |

To outline the Department of Defense’s (DOD) approach for advancing joint C2 capabilities to support US national security interests. |

|

JADC2 Implementation Plan |

March 2022 |

To provide a primary means through which DOD identifies and implements C2 improvements, based on the JADC2 Strategy. |

|

JADC2 Reference Architecture |

August 2020 with recurring updates |

A high-level architectural description of JADC2 that provides an analytical structure framework to guide and evaluate development of Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) capabilities. |

|

JADC2 Reference Design |

November 2022 with additional volumes |

To provide capability developers information on how to model data to be interoperable in a CJADC2 context. |

|

JADC2 Posture Review |

July 2021 |

Compares the CJADC2 Implementation Plan & Strategy with C2-related capability requirements. |

|

JADC2 Campaign Plans (2027 and 2030) |

September 2023 and May 2024 |

Outlines time-bound, risk-based, and threat-informed goals to focus command and control capability development and deployment. |

|

CJADC2 Capstone Initial Capabilities Document |

October 2024 |

Defines broad requirements and gaps to drive capability developments, with the goal to close gaps quickly. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD documentation. | GAO‑25‑106454

Note: All of these documents, unless otherwise described, contain classified elements. Also, CFT officials noted that they have developed annual integrated resource strategy documents which provide recommendations for portfolio investments.

Our review of these documents found that they do not establish a framework to guide investments and track progress towards CJADC2-related goals. In addition, officials at several combatant commands we spoke with were not able to articulate how their efforts align with CJADC2 and contribute to its progress. CFT officials stated that the documents identified in table 3, along with regular meetings, are the primary means by which DOD expects to synchronize CJADC2 efforts across DOD. Air Force and some combatant command officials told GAO that the documents did not change how they consider command and control capabilities. Further, officials guiding different efforts across military departments and combatant commands told us that they want to help achieve the CJADC2 vision but need guidance that is meaningful and flexible. Further, our review of these documents found that some of them are still evolving and in various stages of implementation.

Without a framework to guide investments or track progress, several of the combatant commands we spoke with were not able to articulate how their efforts align with CJADC2 and contribute to its progress. The CJADC2 vision relies on organizations like combatant commands to make individual investments that work together to achieve the desired collective outcome. Officials at combatant commands—including Indo-Pacific Command—specifically referenced the need for guidance regarding which CJADC2 capabilities and efforts to prioritize, particularly when there are so many approaches to the same problems. For example, combatant commands are pursuing largely separate efforts to achieve their own goals. However, the extent to which these efforts contribute to and align with CJADC2 is not clear. Table 4 provides selected examples of combatant command information-sharing systems or projects.

|

Combatant Command |

Data integration system/project |

System purpose |

|

U.S. Central Command |

Collaborative Partner Environment |

Provides secure information sharing environment between U.S. Central Command, allies, and partners. |

|

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command |

Joint Fires Networka |

A fires-informing decision network at the theater strategic and operational levels that provides a persistent targeting common operating picture and mission command applications enabling decision-makers to plan and execute fires across services and partners at speed and scale. |

|

U.S. European Command |

Mission Partner Environment |

Facilitates data sharing among the U.S., foreign partners, and allies within the European Command area of responsibility. |

|

U.S. Northern Command |

Artificial Intelligence-based decision support system |

Enables users to explore and visualize battle while increasing ability to anticipate, monitor, and respond to destabilizing activities within the Northern Command area of responsibility. |

|

U.S. Space Command |

Joint Communications System |

Provides data aggregation and integration software for certain space systems. |

|

U.S. Special Operations Command |

Mission Command Systems/Common Operational Picture |

Provides global situational awareness for Special Forces operations. |

|

U.S. Transportation Command |

Logistics data dashboard |

Provides users with current and understandable transportation and logistics information through a data dashboard. |

|

U.S. Strategic Command |

Global Data Integration |

Provides data, analytics, and communications as a service to combatant commands, military departments, and operational warfighters. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense documentation. | GAO‑25‑106454

aAccording to DOD, Joint Fires Network is a prototype which will inform CJADC2 long range fire requirements over an information technology based architecture and is transitioning to an official program of record. The USD (R&E) has led JFN prototyping efforts working with the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

Similarly, the military departments, other defense agencies, and the intelligence community are also pursing initiatives to better integrate command and control functions within their organizations, as shown in table 5. These large, multi-faceted efforts are intended to identify and deliver command and control capabilities to operational units within the related organizations that, in turn, deliver systems and capabilities to the combatant commands for use in joint operations. While these efforts could benefit DOD’s CJADC2 goals, the extent to which they are contributing is not clear.

Table 5: Military Department, Other Defense Agencies, and Intelligence Community Command and Control Efforts

|

Entity |

Program or project name |

Purpose |

|

Air Force |

Department of the Air Force Battle Network, including the Advanced Battle Management System |

Integrates Air Force and Space Force programs by enabling distributed command and control at a variety of geographically disperse locations. |

|

Army |

Project Convergence |

By using data and communications more effectively, deliver speed, range, and decision dominance to achieve battlefield success. |

|

Navy |

Project Overmatch |

Develops and delivers the Naval Operational Architecture, enabling resilient communications and decision advantage necessary for distributed maritime operations, littoral operations in a contested environment, and expeditionary advanced base operations. |

|

Missile Defense Agency |

Command and Control, Battle Management, and Communications |

Integrating element of the Missile Defense System. Enables defense of an area larger than those covered by individual system elements and against more threat missiles simultaneously. |

|

DOD wide includes military services, nuclear force commanders, and defense agencies |

Nuclear Command and Control System |

Large, complex system of multidomain components used to ensure connectively between the President and military forces in the instance of a nuclear event. |

|

Intelligence Community |

Various efforts |

Supports Intelligence Community Data Strategy to make data more interoperable and ensure secure and timely, discovery, analysis, production, and dissemination of data. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense and Intelligence Community documentation. | GAO‑25‑106454

According to leading practices for cross-functional teams as well as standards for internal control, it is critical for organizations to guide investments by establishing measurable goals, measure progress against these goals, and use the data to make adjustments.[16] Further, according to DOD doctrine, near real-time comprehensive data sharing is critical to effectively employing command and control activities within a specific geographic area, function, or among military units that work together for a specific mission.[17] Without a framework that provides clear guidance for investments and measures to track progress, military departments and combatant commands will continue to focus on meeting the needs of their organization’s specific mission objectives without understanding how their efforts align with and contribute to CJADC2 goals, if at all.

Focused Efforts Demonstrate Results, but DOD Has Yet to Widely Share and Promote Lessons Learned and Address Challenges

The CDAO is conducting iterative experimentation activities aimed at advancing technologies and software to demonstrate selected data-sharing capabilities. However, some key stakeholders told us there was limited awareness of experimentation efforts and successes. Further, we found several critical challenges to achieving CJADC2 that DOD has yet to identify and address.

The CDAO Is Conducting Experiments That Connect Existing Systems, but Results and Lessons Learned Are Not Widely Shared

The CDAO is conducting exercises aimed at identifying and evaluating data-sharing solutions that can contribute to DOD’s broader command and control capabilities. This activity is primarily done through Global Information Dominance Experiment (GIDE) events. GIDE is comprised of a series of test events, conducted approximately every 3 months, that focus on specific high-priority challenges that the CDAO attempts to address by combining available data in new ways. For GIDE, the CDAO has identified specific objectives that it groups into three focus areas:

· Command Collaboration: Focuses on improving data sharing among combatant commands and developing tools to better understand global risk as opposed to specific geographic risks.

· Joint Kill Webs: Focuses on more effectively and efficiently identifying and acting on targets across sea, air, land, space, and cyberspace domains and across military departments.

· Mission Partner Integration: Focuses on improving data sharing with foreign allies and partners.

DOD officials noted that twelve GIDE events have taken place, each focusing on a specific mission or part of the world and leveraging operational networks with live data. Each successive GIDE event builds on the results and discoveries of the preceding ones using an iterative process. As capabilities are either developed or improved during these events, those capabilities are then available for users and recommended for implementation throughout the enterprise.

According to DOD officials, the CDAO’s GIDE events have generally been successful. For example, according to U.S. Central Command, the volume of targets that it can identify and act on in its area of responsibly within a 24-hour period has increased ten-fold by implementing specific

|

XVIII Airborne Corps The XVIII Airborne Corps—located at Fort Bragg, NC—is known as “America’s Contingency Corps” that “rapidly deploys ready Army forces anywhere in the world by air, land or sea, entering forcibly, if necessary, to shape, deter, fight and win.” Because of its mission, it regularly operates in a joint capacity. In 2022 members from the XVIII Airborne Corps deployed to Germany for 9 months in support of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in response to a heightened security environment in Eastern Europe. Source: Department of Defense. | GAO‑25‑106454 |

data-sharing and processing capabilities demonstrated in a GIDE event. In another instance, the CDAO successfully integrated two large data systems, which allowed users to assess logistics information associated with proposed military courses of action with greater speed and precision. Thus, the commander’s understanding of options and risks was improved. According to U.S Central Command officials, military planners would get information from operational planners and then, separately, gather information from logistics planners that they would then combine using documents and slide decks to assess the feasibility of a particular course of action. By integrating the systems, the user can now immediately visualize potential logistics issues that they might encounter with a planned course of action and adjust it in real-time. Some of the combatant commands we spoke with have successfully implemented this capability.[18]

In addition to the GIDE experiments by the CDAO, some military units are also experimenting with command and control data solutions. For example, the XVIII Airborne Corps is a large military unit developing increased warfighting capability through its own iterative experiments. Like GIDE, the XVIII Airborne’s experimentation series, known as Scarlet Dragon, operates on a 3-month cycle and has yielded positive measurable results, particularly in target identification and validation and software efficiency. For example, XVIII Airborne officials reported that during a recent deployment they developed 62 software updates in a 10-month period, resulting in a 600 percent improvement in software efficiency. Additionally, members of the XVIII Airborne Corps targeting team processed 55 targets per day in support of a contingency operation but officials told us that they believe that number could grow to 5,000 targets per day using advanced artificial intelligence tools in the future.

In prior work, we found that the collecting and sharing of lessons learned from previous programs or projects provides organizations with a powerful method for sharing ideas for improving work processes.[19] In particular, we found that collecting and sharing lessons learned from an interagency effort is valuable because one agency can share lessons it has learned with other agencies that may benefit from the information.[20]

While the organizations conducting GIDE and other iterative experiments have often gathered lessons learned, those lessons and successful techniques have not been widely shared across the enterprise. Further, experimentation efforts have not been driven by common lexicon, guidance, or principles. Officials with the XVIII Airborne Corps told us that the lack of formally documented guidelines makes it difficult for other organizations to implement a successful iterative approach, making it challenging for similar organizations to duplicate the results of the XVIII Airborne Corps. Without DOD widely sharing lessons learned and providing guidance for GIDE-like events across DOD and other agencies, organizations may spend time addressing problems that others have already solved or spend time developing capabilities that others have already fielded.

CJADC2 Leadership Has Yet to Identify and Address Key Challenges

The CJADC2 CFT and CDAO have yet to fully identify and address key challenges that prevent CJADC2 stakeholders from better sharing and using data with each other and international partners. Due to the vast array of stakeholders involved with CJADC2, there are complex challenges with data classification, DOD policies, and technical processes. In March 2022, DOD published a summary of its CJADC2 strategy that states that successful implementation of CJADC2 required a coherent and focused DOD-wide effort. Further, this document states that the CFT is responsible for implementing this plan and addressing challenges. However, some of those challenges are beyond the purview of the CFT and may require DOD or government leadership attention. Many of these challenges reflect unique organizational needs, practices, and cultural norms within DOD and the intelligence community. For example, combatant commands and the intelligence community expressed that they manage data differently than one another, which creates barriers to these organizations’ ability to share data and limits the ability to collaborate on complicated operational challenges. Without comprehensively collecting information on and addressing these key challenges, DOD’s ability to work towards the CJADC2 vision is significantly hindered.

Acquisition Challenges

· Making weapons systems interoperable. DOD entities have historically developed complex systems of systems, such as satellite communication systems, that often have difficulty sharing data with other systems. Key reasons these systems cannot easily communicate with each other include military department-specific operational and acquisition requirements, stove-piped system development efforts, and proprietary contractor designs and architectures, among others. In our January 2025 report on DOD’s use of modular open systems architecture, we found that several acquisition programs did not take full advantage of this type of architecture, in part, because DOD did not sufficiently incentivize programs to use and plan for open architecture.[21] Establishing full command and control over a battlespace in a contested environment using all data available requires linking hundreds of critical systems.

· Establishing standards and guidance for improved data exchange. Various DOD practices impede CDAO efforts to use software in cloud computing.[22] One example is the use of proprietary application programming interfaces (API), which can restrict the government’s ability to connect software applications and make updates. An API is software that creates a standardized system access point for a collection of data, which other systems can use to access that data. This sets up machine-to-machine communication, which can allow users to obtain real-time data awareness.[23] DOD has previously reported that the APIs currently in use have non-standard data connections that limit compatibility across the enterprise. This is in contrast to previous GAO findings, which state that providing data in non-proprietary formats and interoperable with other datasets can make that data more useful for users.[24] The CDAO is working to improve the use of APIs across the CJADC2 vendors, which, according to CDAO officials, has been successful.

Further, establishing and using open standards and architectures are complicated by relying on a single software provider to deliver key data solutions that enable command and control capabilities. Officials from several different organizations with whom we spoke shared their concern that DOD could effectively become locked to certain vendors for key capabilities. This concern is based on officials’ observation of the CDAO’s current usage of a particular contractor-developed, artificial intelligence software suite during experimentation activities. Vendor lock means DOD entities cannot shift to another vendor without incurring substantial costs, rework, or inconvenience or become reliant on that contractor to achieve its missions. We have previously found that this can result in significant cost increases for software licenses.[25]

· Building a DOD-wide cloud or data repository. The extent to which the CDAO can build a software environment that facilitates data exchange across all of DOD and connects to the Intelligence Community is unclear. In 2023, the CDAO began pursuing a data integration layer as a system to connect the various data sources and in different environments. However, the CDAO has changed its approach—in light of new leadership—and officials now emphasize that this data integration layer is a computing environment that effectively connects existing federated data across multiple systems and mission areas.

In May 2024, the CDAO announced a new initiative aimed at creating acquisition vehicles that allow DOD organizations to more easily leverage commercial technologies to scale data, analytics, and artificial intelligence development. This effort is called Open Data Applications Government-owned Interoperable Repositories (OPEN DAGIR). The CDAO is planning to pursue innovation through OPEN DAGIR by focusing on three aspects —1) enterprise-level infrastructure that can quickly onboard new capabilities, 2) applications that the government can procure through license agreements, which standardize digital tools, and 3) a new acquisition process that can prototype and scale new digital solutions. However, CDAO officials told us that there will not be a single data repository or integration layer of any kind across DOD.

Policy Challenge

· Security classification. Command and control data tends to be highly classified, as this type of data often contains real-time information about the location of military forces and enemy combatants. Further, information is classified to protect the sources and methods of obtaining the data. Multiple levels of classification exist, and classified data at each level may be restricted to certain networks.

Additional designators further limit foreign partners and allies from seeing certain information. Data or information tagged as Not Releasable to Foreign Nationals or NOFORN is not available to any non-U.S. entities. For example, we heard from agency officials that there is a SECRET/NOFORN database that is critical to cooperation among a trilateral of security partnership countries—Australia, United Kingdom, and U.S. Other information is only releasable to specific international partners. Once information is tagged with these designators, it can be difficult to change them, even if they were too restrictive or if stakeholders determine that sharing is in the U.S. interest.

Some of the principal agencies involved in the CJADC2 concept, such as the military departments, have the authority to establish data security classifications. However, this does not give them authority to facilitate the necessary data transfers across classifications, which combatant command officials and military department services told us contributes to some of the largest data-sharing delays across CJADC2 stakeholders. Several officials we met with cited the inability to readily share classified information with allies and mission partners who, according to DOD strategic documents, are an integral part of the future of CJADC2. Addressing classification policy concerns will require senior DOD level leadership attention as this area is not the purview of the CJADC2 CFT nor the CDAO.

Organizational Challenges

· Collaboration within and among joint forces. DOD uses Joint Task Forces to closely integrate forces in complex mission areas. According to DOD documentation, these task forces face challenges, such as unity of effort and interoperability, which can affect DOD’s ability to identify and use a complete set of data. Differences in budget, authorities, and culture can affect a joint force’s ability to accomplish missions. During the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, we found that DOD faced challenges in coordinating the use of joint forces because of complex command relationships that, at times, also led to incomplete data.[26]

Our prior work also found DOD concerns that individual services prioritize their individual service efforts, as opposed to supporting joint force efforts in the long run.[27] This means that in a resource constrained environment, military services might be more interested in prioritizing funds for their specific capabilities and less interested in funding joint capabilities.

· Collaboration with the Intelligence Community. DOD and the Intelligence Community have many collaboration challenges. For example, when multidomain operations rely on Intelligence Community data, performing missions requires more coordination and processes. In part, this is because there are different data standards and requirements for Intelligence Community and DOD data. The additional time and staff resources involved in this coordination could make it more difficult to conduct this type of multidomain activity during a fast-paced operation.

Intelligence Community leadership has previously stated that its data is generally not accessible, making intelligence sharing with partners, including DOD, a significant challenge. However, they have also stated that collaborating and cultivating partnerships with partners is critical to its mission success. For data to move across the CJADC2 enterprise, these different organizations need to work together to agree on data standards. However, given the Intelligence Community’s mission and unique security requirements and authorities, it often does not provide the broader DOD with data. This means that other CFT stakeholders will need to work within the restrictions that the Intelligence Community establishes around its data, rather than having ready access to the data CJADC2 requires.

· Collaboration with foreign allies and partners. In addition to the classification issues listed above regarding disclosure to foreign entities, DOD also faces data-sharing challenges with coalition forces. For example, DOD might have data-sharing agreements with all foreign partners within a coalition. However, if those foreign partners do not also have data-sharing agreements among themselves, which is out of the control of the US government, effective data sharing can be hindered. For example, while the US may have data-sharing agreements with Australia and Japan, if Australia and Japan have not agreed to share data with each other then, according to combatant command officials, they cannot be put into the same data-sharing environment or network.

DOD also faces challenges that are beyond the scope of its CFT stakeholders, although the CFT can be a forum for different entities, such as combatant commands or military departments to discuss the best way for them to work together, officials noted. For example, DOD has very little influence, if any, over what data standards allies and partners use. Therefore, when DOD develops capabilities using the CFT-developed requirements with the goal of connecting to allies and partners, there can be disparate requirements for those capabilities because of the breadth of data sharing that DOD envisions with allies and partners. Some of these international partners have been included in CFT planning. However, there are logistical and security limitations to the stakeholders the CFT can include, even though the CJADC2 concept requires the Joint Force to exchange information and coordinate actions in all types of combined operations. Without senior DOD and government leadership providing guidance or support, these problems are likely to persist.

Conclusions

DOD is making positive progress in refining its vision for CJADC2. However, the scope of the effort across combatant commands, military services, and the intelligence community is enormous and complicated. These organizations are all pursuing command and control capabilities, but the extent to which these capabilities are contributing to the overall CJADC2 effort is unclear. Typically, individual military departments will prioritize their own programs over joint capabilities. Without a common framework that assesses the extent to which key stakeholders and organizations are pursuing the goals established by the CFT, any progress made by DOD will remain hard to understand and likely relies on joining individual efforts together after-the-fact, rather than working collectively from the outset.

The promising efforts of several DOD organizations, such as the XVIII Airborne Corps and CDAO, are demonstrating progress toward CJADC2 goals and capabilities. However, DOD has limited formal lessons learned mechanisms in place to inform future efforts or to help other DOD organizations contribute to CJADC2 objectives. More formalized and CJADC2-focused lessons learned would help DOD manage its efforts and help guide its unique partners in a common direction.

DOD faces many critical challenges to achieving CJADC2 that are not new or novel, but it lacks a strategy or approach to identify and address these challenges. These challenges are complex and difficult to address. For example, various organizations have different missions and legal authorities, and international partners are sovereign nations who do not always want to share information with each other even if they want to share information with the United States. However, thus far, DOD ‘s efforts to identify and address these key challenges appear disparate and unorganized. Without a comprehensive approach to identify and address these challenges, DOD’s ability to achieve further progress toward its CJADC2 vision will face significant roadblocks.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should establish a framework to evaluate the extent to which military organization investments align with and achieve CJADC2 goals. The framework should establish clear guidance for command and control investments and a means to collectively track progress toward CJADC2 goals. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should establish an approach to consolidate and share lessons learned from ongoing CJADC2-related experimentation and real-world activities to the larger DOD enterprise. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should identify, comprehensively assess, and address key challenges that hinder progress toward DOD’s CJADC2 goals. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD provided an official comment letter (reproduced in appendix I) noting concurrence with two of our recommendations and partial concurrence with one of them. DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

DOD partially concurred with our first recommendation to establish a framework to evaluate the extent to which military organization investments are aligned with and achieving CJADC2 goals. In its comments, DOD noted the Secretary of Defense can evaluate the extent to which military organizations are aligned and are achieving CJADC2 goals through its capability portfolio management (CPM) process. At the time of our review that process had not yet been fully implemented for CJADC2, but DOD noted that as CJADC2 CPM matures, the Secretary will have the information needed to effectively manage and oversee DOD’s command and control investments. We agree that DOD could largely satisfy the intent of our recommendation as it matures its CJADC2 CPM process but want to reemphasize the importance of establishing, as part of that maturation, clear guidance for command and control investments and a means to clearly and accurately track progress toward achieving its CJADC2 goals.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and other interested parties, including the Secretary of Defense, the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Director of National Intelligence, Secretaries of the Air Force, Army, and Navy, and combatant command commanders. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or members of your staff have any questions regarding this report, please contact me at masterst@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix II.

Travis J. Masters

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

List of Congressional Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mitch McConnell

Chair

The Honorable Christopher Coons

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

GAO Contact

Travis J. Masters, masterst@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff members made key contributions to this report: Laurier Fish (Assistant Director), Charlie Shivers III (Analyst-in-Charge), Pete Anderson, Vinayak Balasubramanian, Hans Eggers, Ethan Kennedy, and Adam Wolfe.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website:https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]See GAO, Major Automated Information Systems: Selected Defense Programs Need to Implement Key Acquisition Practices, GAO‑14‑309 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 27, 2014); Defense Acquisitions: Cyber Command Needs to Develop Metrics to Assess Warfighting Capabilities, GAO‑22‑104695 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 30, 2022); and Defense Acquisitions: DOD Management Approach and Processes Not Well-Suited to Support Development of Global Information Grid, GAO‑06‑211 (Washington D.C.: Jan. 30, 2006).

[2]See H.R. Rep. No. 117-397, at 255 (2022).

[3]For the purposes of this report, we use the phrase “military department” to refer to the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy, and the Department of the Air Force. See 10 U.S.C. § 101(a)(8). We use the phrase “military service” to refer to the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Space Force, and Coast Guard.

[4]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[5]GAO, Battle Management: DOD and Air Force Continue to Defense Joint Command and Control Efforts, GAO‑23‑105495 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2023).

[6]A domain is an area of activity within the operating environment in which operations are organized and conducted.

[7]Joint Chiefs of Staff, Countering Air and Missile Threats, Joint Publication 3-01 (Apr. 6, 2023).

[8]An operations center is a facility or location on an installation, base, facility used by the commander to command, control, and coordinate all operational activities.

[9]GAO, Artificial Intelligence: DOD Needs Department-Wide Guidance to Inform Acquisitions, GAO‑23‑105850 (Washington, D.C.: June 29, 2023).

[10]10 U.S.C. § 151(b).

[11]10 U.S.C. § 155(a).

[12]At the time it was established, it was the JADC2 CFT.

[13]GAO, Defense Management: DOD Needs to Implement Statutory Requirements and Identify Resources for its Cross-Functional Reform Teams. GAO‑19‑165 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 17, 2019).

[15]An initial capabilities document identifies a specific gap or set of gaps that exist in joint warfighting capabilities and proposes various potential solutions to address those gaps.

[16]GAO, Defense Management: DOD Needs to Take Additional Actions to Promote Department-Wide Collaboration, GAO‑18‑194 (Washington, DC: Feb. 28, 2018); GAO‑14‑704G.

[17]Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-01. Countering Air and Missile Threats (Apr. 6, 2023).

[18]There are other positive examples that are classified.

[19]GAO, DOD Utilities Privatization: Improved Data Collection and Lessons Learned Archive Could Help Reduce Time to Award Contracts, GAO‑20‑104 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 2, 2020); and Project Management: DOE and NNSA Should Improve Their Lessons-Learned Process for Capital Asset Projects, GAO‑19‑25 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 21, 2018).

[20]GAO, Federal Real Property Security: Interagency Security Committee Should Implement A Lessons-Learned Process, GAO‑12‑901 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2012).

[21]GAO, Weapon Systems Acquisition: DOD Needs Better Planning to Attain Benefits of Modular Open Systems, GAO‑25‑106931 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 22, 2025).

[22]Cloud computing is a means for enabling on-demand access to shared pools of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released. See National Institute of Standards and Technology, The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing, Special Publication 800-145 (Gaithersburg, Md.: September 2011).

[23]GAO, Open Data: Treasury Could Better Align USAspending.gov with Key Practices and Search Requirements, GAO‑19‑72 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 13, 2018).

[25]GAO, DOD Software Licenses: Better Guidance and Plans Needed to Ensure Restrictive Practices Are Mitigated, GAO‑23‑106290 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2023).

[26]GAO, Military Readiness: Joint Policy Needed to Better Manage the Training and Use of Certain Forces to Meet Operational Demands, GAO‑08‑670. (Washington D.C., May 30, 2008).