ECONOMIC DOWNTURNS

Considerations for an Effective Automatic Fiscal Response

Report to Congressional Requesters

The publication date is June 9, 2025, and the public release date is July 7, 2025.

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Jeff Arkin at arkinj@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO-25-106455, a report to congressional requesters

Considerations for an Effective Automatic Fiscal Response

Why GAO Did This Study

GAO previously found that automatic stabilizers reduced the detrimental effects of recent economic downturns. For example, studies GAO reviewed showed that during downturns automatic stabilizers generated additional economic activity. They also had positive effects on the well-being of individuals and families, such as alleviating poverty and supporting positive health outcomes. Automatic stabilizers temporarily increase federal deficits in the wake of economic downturns.

GAO was asked to review several issues related to automatic stabilizers. This report describes (1) factors that contribute to the effective design of automatic stabilizers, (2) how triggers can be used to support automatic stabilization, and (3) the trade-offs and other considerations of select policy options to enhance automatic stabilizers.

To identify the factors that contribute to the effective design of automatic stabilizers and how triggers can be used to support automatic stabilization, GAO evaluated and compiled information from a literature review and from 21 expert interviews.

To identify policy options, GAO assessed information from a literature review and interviewed 21 experts in economic policy, social policy, automatic stabilizers, and specific policy areas. GAO evaluated evidence of various potential automatic stabilizers’ strengths and limitations, including their alignment with the factors that make automatic stabilizers effective. GAO discussed the potential automatic stabilizers with applicable federal agencies.

What GAO Recommends

GAO previously recommended that Congress could consider enacting a Federal Medical Assistance Percentage formula that targets variable state Medicaid needs and provides automatic, timely, and temporary assistance in response to national economic downturns.

The Departments of Agriculture, Health and Human Services, Labor, and the Treasury provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

What GAO Found

The federal budget contains mechanisms—known as automatic stabilizers—that alter spending levels and tax liabilities in response to changes in economic conditions without direct intervention by policymakers. For example, when incomes and the employment level fall, more people may become eligible for certain government benefits, such as unemployment insurance and food assistance, and tax liabilities may be lower. Conversely, when incomes and the employment level rise, eligibility for government benefits may fall and tax liabilities may rise.

GAO identified four principles that could be used to assess the design or reform of automatic stabilizers. Information from literature and economic and social policy experts suggests that effective automatic stabilizers are timely, temporary, targeted, and predictable. Within those four broad principles, GAO identified eight factors that contribute to the effective design of automatic stabilizers (see table).

|

Principles |

Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they: |

|

Timely |

Provide stimulus when it is needed most |

|

Temporary |

End stimulus as the economy recovers |

|

Are designed to minimize their long-term effect on the deficit |

|

|

Phase out benefits gradually as the economy recovers |

|

|

Targeted |

Are intended to have the greatest economic impact |

|

Reach the entire eligible population to the extent possible |

|

|

Tailor aid to state and local governments to reflect the relative severity of the economic downturn in each state or locality |

|

|

Predictable |

Are established in advance so that they are ready in times of crisis |

Source: GAO analysis of information from literature and interviews with experts. | GAO-25-106455

Deficit increases caused by increased spending and lower tax revenue during economic downturns should be temporary and should be mitigated by automatic declines in spending and increases in tax revenue during periods of economic growth. Developing internal controls and improving fraud risk management in automatic stabilizer programs before an economic downturn takes place can help agencies reduce improper payments and help mitigate their effect on the deficit.

While some automatic stabilizers naturally adjust to economic conditions, others use a pre-determined set of rules, known as a trigger, to automatically initiate or expand economic stimulus at the beginning of an economic downturn and end or reduce stimulus when economic conditions no longer call for it. When economic indicators, such as the unemployment rate, reach an established threshold, triggers could start or end stimulus accordingly. Well-designed triggers have the potential to match stimulus to real-time economic conditions and avoid the delays that may occur when policymakers rely on taking discretionary action. However, designing triggers may be challenging, in part because it is difficult to accurately assess economic conditions in real time. Discretionary fiscal policy can allow policymakers more flexibility to tailor assistance to specific circumstances, but actions need to be timely to have the maximum effect.

Based on an analysis of the strengths and limitations of policy options from relevant literature and interviews with knowledgeable experts, GAO identified 17 potential policy options to enhance existing automatic stabilizers or to create new ones (see table). These options are not listed in any specific order and are not comprehensive of all potential policy options for enhancing automatic stabilizers. GAO previously recommended that Congress consider taking action that would enhance Medicaid as an automatic stabilizer. Other than that previous recommendation, GAO does not endorse any specific policy option.

|

Policy Area |

Policy Option |

|

Unemployment Insurance (UI) |

Temporarily expand UI eligibility |

|

Temporarily increase weekly UI benefit amounts |

|

|

Temporarily increase the duration of UI benefits |

|

|

Short-Time Work Programs |

Temporarily federally fund the Short-Time Compensation programa |

|

Expand short-time work programs to all states |

|

|

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) |

Temporarily increase SNAP benefit amounts |

|

Temporarily suspend SNAP time limit and work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents |

|

|

Temporarily waive certain SNAP administrative requirements |

|

|

Temporarily increase federal SNAP administrative funding to states |

|

|

Medicaid |

Adjust the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage formula to be responsive to economic conditions |

|

Tax system |

Provide direct payments to individuals and families through the tax system |

|

Temporarily reduce employee payroll taxes |

|

|

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) |

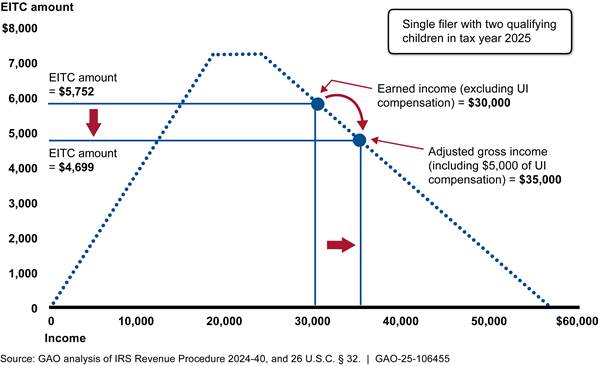

Temporarily allow taxpayers the option to include or exclude UI compensation when calculating EITC |

|

Temporarily increase EITC amounts for eligible taxpayers without qualifying children |

|

|

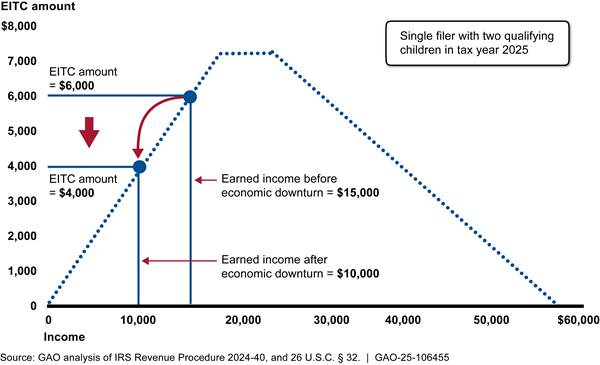

Temporarily allow taxpayers the option to use income from a prior year to calculate EITC amounts |

|

|

Temporarily increase the EITC phase-in rate |

|

|

Child Tax Credit |

Temporarily provide an advance Child Tax Credit |

Source: GAO analysis of information from literature and interviews with experts. | GAO-25-106455

aThe Short-Time Compensation program is a part of the UI system and allows employees experiencing a reduction in work hours to collect a percentage of unemployment benefits to replace a portion of their lost wages.

Each of these policy options have trade-offs with other policy goals. Some general trade-offs that are broadly applicable to many of the options include:

Economy. Generally, strengthening automatic stabilizers can reduce the detrimental effects of economic downturns and prevent the economy from getting worse. However, enhancing automatic stabilizers could potentially contribute to inflation if they generate a large amount of spending that caused demand for goods and services to exceed the economy’s capacity.

Federal budget. Strengthening automatic stabilizers in ways that increase spending or reduce tax revenue during an economic downturn could add to the federal deficit and debt. However, during periods of economic growth automatic stabilizers result in less federal spending and more tax revenue, which could help reduce deficits. Policy design should carefully weigh the benefits of additional stabilization with any additional budgetary cost.

Improper payments. Increasing benefit amounts or expanding eligibility without appropriate administrative capacity could increase the risk of improper payments—payments that should not have been made or were made in incorrect amounts. Improper payments can include payments to ineligible recipients, duplicative payments, or payments for ineligible goods and services. Developing internal controls before a crisis occurs could help prevent or mitigate improper payments and potential fraud.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ABAWD |

Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents |

|

ACTC |

additional child tax credit |

|

AGI |

adjusted gross income |

|

ARPA |

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 |

|

CBO |

Congressional Budget Office |

|

CHIP |

Children’s Health Insurance Program |

|

CTC |

Child Tax Credit |

|

DOL |

Department of Labor |

|

DSH |

Disproportionate Share Hospital |

|

DWP |

Department for Work and Pensions |

|

EB |

Extended Benefits |

|

E-FMAP |

enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage |

|

EI |

Employment Insurance |

|

EIP |

Economic Impact Payment |

|

EITC |

Earned Income Tax Credit |

|

EPOP |

employment-to-population |

|

ERC |

Employee Retention Credit |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

FEA |

Federal Employment Agency |

|

FMAP |

Federal Medical Assistance Percentage |

|

FNS |

Food and Nutrition Service |

|

G7 |

Group of 7 |

|

GDP |

gross domestic product |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HMRC |

His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs |

|

IMF |

International Monetary Fund |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

MEUC |

Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation |

|

NBER |

National Bureau of Economic Research |

|

NPS |

National Insurance and Pay As You Earn Service |

|

OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

PPP |

Paycheck Protection Program |

|

PUA |

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

SNAP |

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

|

STC |

Short-Time Compensation |

|

STW |

Short-Time Work |

|

TFP |

Thrifty Food Plan |

|

Treasury |

Department of the Treasury |

|

TIGTA |

Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration |

|

UC |

Universal Credit |

|

UI |

Unemployment Insurance |

|

UK |

United Kingdom |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 9, 2025

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Michael F. Bennet

United States Senate

Since 2000, the U.S economy has experienced three recessions, most recently the rapid and severe recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, the federal government used tax and spending policies to stimulate economic growth and limit the detrimental economic effects on individuals and families. Some of this stimulus was enacted in direct response to the recession through legislation including the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the CARES Act, and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.[1]

Some of this stimulus also occurred automatically through certain provisions in federal law known as automatic stabilizers. These provisions alter spending levels and tax liabilities to respond to the effects of fluctuations in economic activity without the need for changes in the tax code or other legislation. As a result, they can provide timely adjustments in response to changes in economic conditions without direct intervention by policymakers. For example, when incomes and the employment level fall, more people may become eligible for certain government benefits, such as Unemployment Insurance and food assistance, and tax liabilities may be lower. Conversely, when incomes and the employment level rise, eligibility for government benefits may fall and tax liabilities may rise.

While some automatic stabilizers naturally adjust to economic conditions, others use a predetermined set of rules, known as a trigger, to activate changes in response to economic conditions. Triggers are tools that can automatically initiate stimulus at the beginning of an economic downturn and end stimulus when economic conditions no longer call for it. When economic indicators, such as the unemployment rate, reach an established threshold, triggers will start or end stimulus accordingly.

Strengthening automatic stabilizers could potentially help the federal government further support economic growth in the near-term to recover more quickly from recessions and further help vulnerable individuals and families mitigate the inevitable hardships that accompany them while also building in safeguards to prevent improper payments and fraud. At the same time, strengthening automatic stabilizers could potentially help the government automatically reduce support for the economy and individuals as the economic outlook improves to avoid overstimulating the economy and further contributing to federal deficits and debt.

We were asked to review several issues related to automatic stabilizers. We previously reported on the effect of automatic stabilizers on the well-being of individuals and families during economic downturns.[2] In this report, we (1) examine the factors that contribute to the effective design of automatic stabilizers, (2) describe how triggers can be used to support automatic stabilization, and (3) identify policy options that could enhance automatic stabilizers, along with related trade-offs and other considerations.

We focused this report on two categories of automatic stabilizers: existing automatic stabilizers and potential new automatic stabilizers. The major existing automatic stabilizer programs, as identified by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), are Unemployment Insurance (UI), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and several provisions in the tax code. We previously reported that these automatic stabilizers reduced the detrimental effects of economic downturns and improved the well-being of individuals and families.[3] Potential new automatic stabilizers we selected for analysis include existing federal programs that currently do not automatically respond to changes in economic conditions and previous temporary programs that have been enacted in response to prior economic downturns.

To do this work, we:

· Conducted a literature review of publications from academia, government, international organizations, and think tanks.

· Interviewed knowledgeable subject matter experts from government, nongovernmental organizations, organizations representing state and local governments, and academia.

· Conducted case studies of three countries: Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom (UK).[4] We selected these countries based on several characteristics, including membership in the Group of 7 (G7) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and to ensure representation of both centralized and decentralized governmental structures.[5]

· Identified factors and trade-offs that make automatic stabilizers effective in supporting the economy and the well-being of individuals and families and how triggers could be used to support stabilization by synthesizing themes from the literature review and expert interviews. We obtained feedback from experts on a draft list of factors before finalizing the list.

· Identified and selected policy options for both enhancing current automatic stabilizers and for potentially creating new ones. To do this, we (1) identified potential policy options based on a review of literature and interviews with experts; (2) analyzed the potential policy options to ensure that they met certain criteria, such as being targeted to individuals and families and being administered or at least partially funded by the federal government; (3) analyzed the strengths and limitations of these policy options, including their alignment with the factors that contribute to the effectiveness of automatic stabilizers; and (4) consulted with experts and the federal agencies that would administer or oversee the applicable programs and taxes. Our list of policy options is not comprehensive of all potential policy options for enhancing or creating new automatic stabilizers. We do not endorse the potential policy options, except for one option that we previously recommended to Congress.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2022 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Automatic Stabilizers Are Fiscal Mechanisms That Help Stabilize the Economy During Downturns

Economies go through alternating periods of upswings and downturns. This pattern is commonly referred to as the business cycle.[6] The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) defines a recession as a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.[7] NBER defines an economic expansion as occurring after the economy reaches its lowest point and economic activity begins to increase.

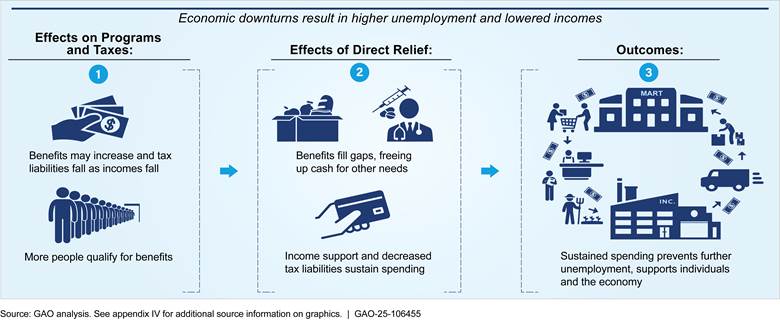

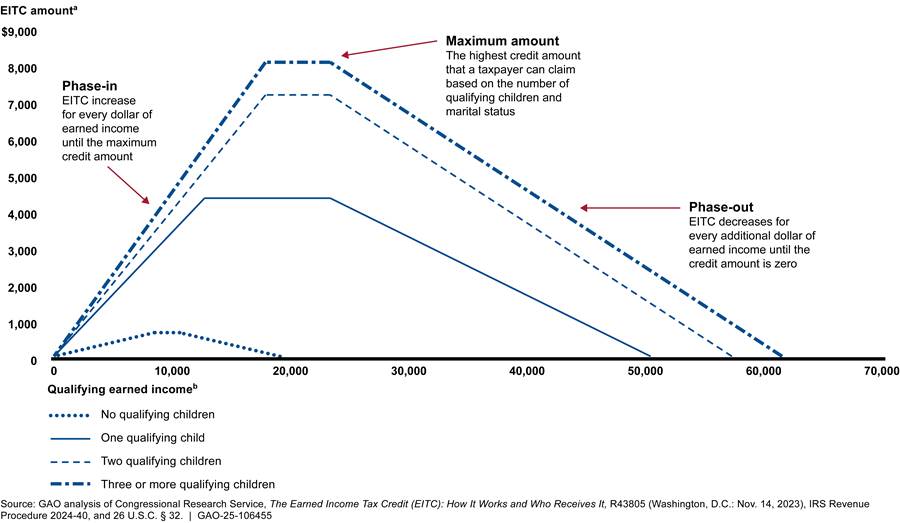

During economic downturns, automatic stabilizers are one way the federal government can use tax and spending policies to support economic growth and limit the detrimental effects on individuals and families. Studies we reviewed in our prior work found that automatic stabilizers limit the depth of economic downturns and reduce fluctuations in economic activity.[8] Figure 1 provides examples of how tax provisions and spending programs work as automatic stabilizers and affect the economy.

Automatic stabilizer mechanisms help to reduce uncertainty individuals may experience during an economic downturn related to potential financial hardships, such as job loss and food insecurity. Mitigating this uncertainty can help prevent people from substantially reducing consumption and increasing saving in anticipation of such financial hardship, actions that can exacerbate the effects of a downturn.

Key Automatic Stabilizer Programs

There are three spending programs that CBO identified as automatic stabilizers: UI, SNAP, and Medicaid.[9] All three of these programs experience increased enrollment during economic downturns and a decrease in enrollment as the economy recovers.[10]

· UI is a joint federal-state program that provides temporary financial assistance to eligible workers who have become unemployed through no fault of their own by replacing a portion of a recipient’s previous employment earnings.[11] UI benefits are primarily funded through state taxes on employers, while program administration is financed through a federal tax on employers.[12]

· SNAP provides nutrition benefits to supplement the food budgets of low-income households. The goal of SNAP is to help low-income households obtain a more nutritious diet by increasing their food-purchasing power. SNAP benefits are funded by the federal government, with administrative costs shared by states. SNAP benefit eligibility and amounts are determined by household size and income.[13]

· Medicaid finances health care coverage for millions of low-income and medically needy individuals. Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal government and states, with the federal government matching most state expenditures based on a statutory formula that covers at least half of states’ expenditures.[14]

In addition to these three spending programs, CBO identified multiple provisions within the U.S. tax code that also act as automatic stabilizers. These include provisions for (1) individual income tax; (2) payroll taxes (taxes that pay for Medicare, Social Security, and UI); (3) corporate income tax; and (4) taxes on production and imports. For example, individual income taxes are progressive, meaning that individuals with higher incomes generally pay a higher share of their income in taxes while individuals with lower incomes generally pay a lower share. During economic expansions, income tax revenue increases as individual incomes rise and the share of income paid in taxes rises. The opposite effect occurs during downturns. CBO analysis shows that the taxes that act as automatic stabilizers account for nearly all federal revenue.[15]

These programs and the taxes exist primarily for purposes beyond economic stabilization. They were created with other goals, for example, supplementing the food budgets of low-income families or collecting revenue to fund government programs and operations.

Discretionary Fiscal Policies

In addition to automatic stabilizers, the federal government can make temporary changes to taxes or spending programs—referred to as discretionary fiscal policy.[16] Discretionary fiscal policy is often used to make temporary changes to key automatic stabilizer spending programs either to extend the duration of benefits, provide benefits to individuals who do not traditionally qualify, or increase benefit amounts for eligible individuals.[17] Discretionary fiscal policy provides policymakers with more flexibility to tailor assistance to specific circumstances, but it sometimes entails a delay in providing benefits since adjustments to programs may require legislative action.

Automatic Stabilizers in Other Advanced Economies

According to the International Monetary Fund and OECD, the ability of automatic stabilizers to reduce the severity of downturns in the business cycle can be related to the size of the government’s spending and revenue as a share of the economy. Automatic stabilizers in advanced economies typically include progressive tax systems as well as spending programs such as unemployment benefits and short-term work programs, which allow employers to retain employees during downturns.[18]

OECD simulations show that automatic stabilizers offset an average of 60 percent of economic shocks to household disposable income in 23 OECD countries. However, the effects of automatic stabilizers vary significantly across countries, with the U.S. near the middle of this range.[19]

To show how automatic stabilizers operate in other advanced economies, appendix II provides illustrative examples from Canada, Germany, and the UK. While these three countries’ automatic stabilizers operate in different ways, they all demonstrate how automatic stabilizers can be used to support the economy and the well-being of individuals and families.

Automatic Stabilizers are More Effective if They Are Timely, Temporary, Targeted, and Predictable

We identified several factors for designing automatic stabilizers that are effective in supporting the economy and the well-being of individuals and families, as well as trade-offs between those factors and other policy goals. These factors are based on a synthesis of information from our literature review and interviews with experts in economic policy, social policy, and automatic stabilizers. They align with four broad principles for policymakers to consider when enhancing existing automatic stabilizers and creating new ones: ensuring that they are timely, temporary, targeted, and predictable (see table 1).

|

Principles |

Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they: |

|

Timely |

Factor 1: Provide stimulus when it is needed most |

|

Temporary |

Factor 2: End stimulus as the economy recovers |

|

Factor 3: Are designed to minimize their long-term effect on the deficit |

|

|

Factor 4: Phase out benefits gradually as the economy recovers |

|

|

Targeted |

Factor 5: Are intended to have the greatest economic impact |

|

Factor 6: Reach the entire eligible population to the extent possible |

|

|

Factor 7: Tailor aid to state and local governments to reflect the relative severity of the economic downturn in each state or locality |

|

|

Predictable |

Factor 8: Are established in advance so that they are ready in times of crisis |

Source: GAO analysis of information from literature and interviews with experts. | GAO‑25‑106455

Automatic stabilizers in the U.S. and our three case study countries—Canada, Germany, and the UK—can serve as illustrative examples of how these factors help automatic stabilizers support the economy and well-being.[20]

Automatic stabilizers operate through programs and taxes that exist primarily for purposes beyond economic stabilization. For example, SNAP helps low-income families afford nutritious food, and payroll taxes finance Medicare and Social Security. As a result, it is important to consider any potential changes to automatic stabilizers in tandem with other policy goals, such as program administration, prevention of improper payments and fraud, and fiscal sustainability.

Automatic Stabilizers Are More Effective When They Are Timely

To provide the greatest benefit to the economy and the well-being of individuals and families, stimulus should be provided as soon as possible when an economic downturn begins. However, precisely timing stimulus can be a challenge. If it is implemented too early, the economic impact of the stimulus may not be large enough to justify its budgetary cost. On the other hand, if it is implemented too late there is a risk that the economic downturn becomes so severe that much more stimulus is needed to stabilize the economy. In addition, if stimulus is not initiated until after the economy has started to recover, it may contribute to inflation.

|

Factor 1: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they provide stimulus when it is needed most. |

Compared to discretionary fiscal policy, automatic stabilizers generally can provide stimulus more quickly because they respond directly to economic conditions without the need for policymakers to act. Conversely, they can ensure that stimulus ends based on economic conditions so it does not end too early, which could jeopardize economic recovery, or last too long, which could contribute to inflation.

Timely stimulus can also ensure that individuals and families receive support at the right time. During economic downturns, many people lose their jobs or face increased financial instability. By providing support for the economy at the right time, automatic stabilizers can prevent these conditions from getting worse and provide support for people facing economic hardship when they need it most. For example, one expert on the federal social safety net whom we interviewed said that when automatic stabilizers are available at the time of income loss, they can replace that income and help people maintain consumption, which dampens economic shock and maintains well-being for individuals and families. Similarly, we previously found that UI benefits can help households that have suffered job loss sustain consumption, leading to increased demand for goods and services which bolsters economic activity and reduces the unemployment rate.[21]

Providing programmatic flexibilities, such as easing administrative requirements, could also streamline the process for individuals and families facing economic hardship to receive financial assistance. However, providing stimulus quickly can hinder fraud prevention by limiting the time available to apply processes intended to ensure government assistance is provided only to eligible individuals and families, and in the correct amounts.

|

Germany’s Short-Time Work (STW) program allows workers to remain employed and companies to retain workers during economic downturns. Companies facing hardship reduce workers’ hours instead of laying them off, and the government provides 60 percent of their net income (or 67 percent for workers with children) for the hours not worked. To initiate STW, a company submits a written announcement to its local employment agency. After the local employment agency reviews the company’s announcement and confirms that basic requirements for participation have been met, the company can request that the local employment agency reimburse it for eligible costs. According to officials from Germany’s Federal Employment Agency (FEA), the government typically makes payments to companies within 15 business days of the announcement. They said that the company’s monthly requests for reimbursement are reviewed for accuracy by FEA. As part of this process, officials told us they use software to assist in detecting instances of potential fraud. FEA officials explained that a comprehensive final examination is conducted after STW has ended for the company. According to FEA officials, if fraud is discovered the company must immediately pay back benefits or face prosecution. This multi-stage process enables Germany to provide timely assistance to companies and workers during economic downturns, which prevents layoffs and helps avoid further economic disruption. |

Source: GAO analysis of German government information and information provided by officials from Germany’s FEA. | GAO‑25‑106455

Automatic Stabilizers Are More Effective When They Are Temporary

Ending stimulus as the economy recovers can help limit the detrimental effects that automatic stabilizers can have on other policy goals, such as deficit reduction and preventing the economy from overheating.

|

What happens when the economy overheats? The economy is said to overheat when the demand for goods and services exceeds what can be produced when the economy is at full capacity. When this occurs, the resulting gap between supply and demand can lead to a rise in inflation. An overheating economy may lead to a downturn if high inflation persists and policymakers enact contractionary fiscal policies that shrink the economy, such as increasing taxes or reducing government spending. Additionally, central banks could take actions that increase interest rates, which would make borrowing more expensive and saving more attractive, thereby reducing spending and slowing the economy. |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑106455

|

Factor 2: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they end stimulus as the economy recovers. |

Ending stimulus as the economy recovers can help limit the growth of federal deficits and debt, as well as the economic effects of rising debt. According to CBO, perpetually rising debt as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) has many direct and indirect implications for the economy and individuals.[22] For example, as the government’s borrowing needs grow, interest rates could rise. Higher interest rates may entice some investors to buy Treasury securities, leaving less capital available to invest in other productive uses, such as research and development.

|

The United Kingdom (UK) provides monthly direct payments to eligible low-income beneficiaries, known as Universal Credit (UC). Payments vary by income. For recipients with earned income, the amount is reduced by 55 pence for every £1 of earnings. As such, during economic downturns more people are eligible and payment amounts can increase for beneficiaries who experience a decline in income. Payments are automatically adjusted to reflect most beneficiaries’ current wages and taxes using real-time data from His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, the UK’s tax agency. These data are shared with the Department of Work and Pensions, which administers UC. By automatically adjusting payments based on real time data, the UK ensures that the financial support UC provides is tailored to current economic circumstances and the needs of individuals and families. |

Source: GAO analysis of United Kingdom government reports and information. | GAO‑25‑106455

Similar to the challenges of determining when to initiate stimulus described above, it can be difficult to determine when to end stimulus. Ending benefits too early, while unemployment remains elevated, could hamper economic recovery and remove benefits when individuals and families are still relying on them to mitigate hardships caused by the economic downturn. One economic policy expert we interviewed suggested that the duration of benefits should correspond with the unemployment rate. Specifically, when the unemployment rate remains high for a longer period of time, this expert said that benefits should be provided for longer, when it can be harder to find employment. Similarly, we have reported that the federal government could provide states with additional temporary Medicaid assistance during economic downturns based on the employment-to-population ratio.[23]

|

Factor 3: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they are designed to minimize their long-term effect on the deficit. |

We previously found that automatic stabilizers contributed to federal deficits in the wake of recent economic downturns, when spending increased and tax revenue declined, but are not the key drivers of debt over the long term.[24] Deficit increases caused by automatic stabilizers during economic downturns should be temporary and should be mitigated by automatic declines in spending and increases in tax revenue during periods of economic growth. By supporting economic growth, automatic stabilizers can also help improve the federal government’s fiscal condition over time.

To be consistent with a long-term fiscal policy it is important that automatic stabilizers strike the right balance between short-term deficits and long-term economic growth. The federal government faces an unsustainable fiscal path due to an imbalance between spending and revenue that is built into current law and policy. In February 2025, we projected that debt held by the public would reach its historical high of 106 percent of GDP by 2027 and grow more than twice as fast of the economy over a 30-year period, reaching 200 percent of GDP by 2047.[25] If not addressed, this poses serious economic, security, and social challenges. Since 2017, we have suggested that Congress develop a strategy to place the government on a sustainable long-term fiscal path, where government spending and revenue result in a stable or declining ratio of debt held by the public to GDP over the long term.[26]

Reducing improper payments and improving fraud risk management in automatic stabilizer programs can help mitigate their effect on the deficit. We found that for fiscal year 2024, four automatic stabilizer programs—Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit, SNAP, and UI—totaled $64 billion in estimated improper payments. [27] Improper payments include overpayments and underpayments, which can result from fraud, lack of agency oversight, mismanagement, errors, and abuse. We previously developed a framework with five principles and corresponding practices that can help Congress and federal program managers design and manage programs that provide emergency assistance funding.[28] Specifically, the five principles are:

· commit to managing improper payments;

· identify and assess improper payment risks, including fraud;

· design and implement effective control activities;

· monitor the effectiveness of controls in managing improper payments; and

· provide and obtain information to manage improper payments.

When properly and promptly applied, these principles can successfully reduce improper payments.

|

Factor 4: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when benefits are phased out gradually as the economy recovers. |

Gradually phasing out benefits when economic conditions indicate that they should be ended prevents recipients from abruptly losing support. If the additional benefits provided during an economic downturn are reduced to predownturn levels all at once, individuals and families may face a sudden drop in income that causes them to reduce their consumption, which could in turn slow economic recovery. We previously reported that in October 2021, following the September 2021 expiration of more generous UI payments, the number of households that reported not having enough to eat began to rise steadily.[29]

On the other hand, one economic and social policy expert we interviewed pointed out that if there were predictable pre-established conditions for ending stimulus the ability to plan may mitigate the impact on recipients. For example, some discretionary fiscal policy actions taken during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as continuous Medicaid enrollment, initially had end dates corresponding to the duration of the public health emergency.[30] This led to uncertainty about the duration of Medicaid coverage for enrolled individuals and state administrative agencies. We previously recommended that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services document and implement lessons learned from the end of the continuous enrollment requirement.[31]

Phasing out benefits could have effects on other policy goals. For example, the more complicated a mechanism for phasing out benefits is, the more administrative burden it could create. Agencies that administer automatic stabilizers like SNAP may have to make multiple changes to their systems to implement a gradual benefit reduction.

In addition, we previously found that while reducing benefits as earnings rise can create potential work disincentives, a more gradual phase-out can lessen these disincentives.[32] However, a slower phase-out of benefits can increase budgetary costs.

Automatic Stabilizers Are More Effective When They Are Targeted

According to CBO, the same dollar amount of spending increases or tax reductions can have significantly different effects on overall demand, depending on how it is provided and to whom.[33] Therefore, designing automatic stabilizers so that they are well-targeted can help ensure that they increase economic activity as much as possible for a given budgetary cost. In addition, targeting the amount of stimulus so that it reflects the magnitude of an economic downturn can prevent an over-response that could have excessive budgetary costs and potentially lead to inflation. Targeting can also ensure that stimulus protects the well-being of individuals and families by assisting those who have been most effected by an economic downturn.

|

Factor 5: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they are intended to have the greatest economic impact. |

Well-targeted stimulus can have the greatest impact on the economy and well-being for a given budgetary cost. Stimulus funds have a more profound effect on short-run demand when recipients spend—rather than save—the financial assistance that they receive. Studies we reviewed found that providing stimulus to low-income individuals and families has the greatest boost to short-run demand in the economy for a given budgetary cost because they are likely to spend any assistance on immediate needs.[34]

In addition, targeting those with the greatest need can have the most significant effect on the well-being of individuals and families during economic downturns. For example, we previously found that SNAP helped the poorest households moderate income fluctuations and UI helped keep people out of poverty during recent economic downturns.[35] However, the effects of individual economic downturns vary, and some may have a greater effect on higher-income individuals, such as homeowners.

|

Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) program provides support for individuals who are unemployed through no fault of their own—known as EI regular benefits—or workers who take time off for life events such as illness and caregiving responsibilities—known as EI special benefits. EI regular benefits are targeted to be higher in areas of the country with the greatest economic need. Specifically, a 3-month moving average unemployment rate is calculated monthly for each of Canada’s 62 economic regions. This average determines for how long benefits are provided, how much is provided, and how many hours a worker needs to have worked to qualify for benefits. The 3-month moving average that is calculated for each month determines the benefit rules for workers who file that month. According to officials, the rules in place for the month in which a worker files for benefits remain in place for that worker for the duration of their benefits.

|

Source: GAO analysis of Canadian government documents and information. | GAO‑25‑106455

According to Joint Committee on Taxation officials, programs targeted to specific eligible populations can be more difficult to administer than programs with broad eligibility. The time needed to verify eligibility can affect the speed at which benefits can be provided.

To prevent improper payments, automatic stabilizers need to balance flexibility with accountability. Programs with less robust verification processes may be more susceptible to fraud. For example, under the CARES Act, the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program allowed workers who were not previously eligible for UI—such as self-employed individuals and gig workers—to obtain UI benefits by self-certifying that they could not work due to a COVID-19 related reason.[36] The Department of Labor’s Office of the Inspector General reported that states cited self-certification as a top fraud vulnerability.[37]

We previously reported that, while the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act addressed this issue by creating new documentation requirements for PUA, the program had already become an attractive target for increasingly sophisticated fraud schemes.[38] We found that preexisting internal control plans might have helped managers quickly implement appropriate controls before payments were disbursed, such as by leveraging existing data-matching services to validate individuals’ employment status. In emergencies, we found that such plans may also help agencies to conduct postpayment checks in a timelier manner.

|

Factor 6: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they reach the entire eligible population, to the extent possible. |

According to economic and social policy experts we interviewed, reaching everyone who is eligible for benefits ensures that federal aid provides the most support to economic recovery, as well as individuals and families. If people who are eligible do not receive benefits, then automatic stabilizers will not have their full intended effect on the economy and well-being. However, it can be difficult to reach people who are not already known to agencies administering stimulus programs.

|

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) distributed three rounds of direct payments to eligible individuals, known as Economic Impact Payments. These payments were provided on a temporary basis only and therefore are not an automatic stabilizer. In an effort to distribute these payments to the entire eligible population, IRS used various methods to engage people who may have been eligible for these payments but were not already in the tax system. For example, some eligible individuals are not required to file a federal tax return. In 2020, IRS mailed roughly 9 million letters to people who do not normally file a federal income tax return but may have qualified for a payment. Overall, IRS identified and contacted potentially eligible individuals by:

See policy option 11 below for a discussion of the effects of potentially making these payments automatic stabilizers, including trade-offs and other considerations. |

Source: Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, Implementation of Economic Impact Payments, 2021-46-034 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2021), and GAO analysis of IRS documents and interviews with IRS officials. | GAO‑25‑106455

It is also important to ensure that payments are only made to those who are eligible, and made in the correct amounts. We previously reported that the risk of improper payments may be higher in emergencies because the need to provide assistance quickly can hinder the implementation of effective controls.[39]

|

Factor 7: Automatic stabilizers are more effective when they tailor aid to state and local governments to reflect the relative severity of the economic downturn in each state or locality. |

State and local governments often face fiscal pressures during economic downturns because revenues generally fall at the same time as certain expenses increase. For example, more people become eligible for Medicaid during economic downturns, and states are responsible for paying a portion of Medicaid costs. However, it is important to target aid to state and local governments in a way that is proportionate to their respective needs. According to the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, allocating COVID-19 rental assistance funding to state and local governments based on population rather than need led to a mismatch between the distribution of pandemic relief funds and need.[40]

|

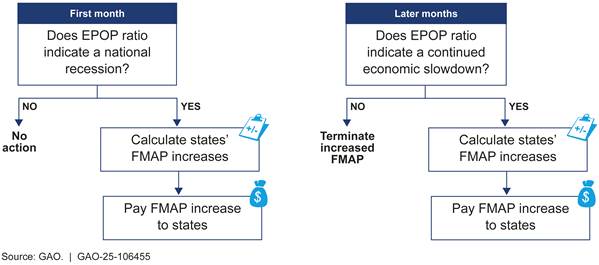

The Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) formula sets the federal matching rate for most state Medicaid expenditures. This formula uses per capita income to calculate each state’s federal matching rate. However, our prior work has found that this is a poor proxy for states’ need for Medicaid funds because it does not fully account for the size of a state’s population in need of Medicaid services or the ability of a state to fund Medicaid. We suggested that Congress consider enacting a formula that targets variable state Medicaid needs and provides automatic, timely, and temporary assistance in response to national economic downturns. For example, we developed a prototype formula that would initiate a temporary FMAP increase when 26 states show a sustained decrease in the employment-to-population ratio. As of February 2025, this matter for congressional consideration has not been implemented. |

Source: GAO, Medicaid: Prototype Formula Would Provide Automatic, Targeted Assistance to States during Economic Downturns, GAO‑12‑38 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 10, 2011). | GAO‑25‑106455

According to CBO, federal transfers to state and local governments only provide stimulus if they do not pay for spending that would have occurred anyway. To stimulate the economy, these payments must lead to an increase in spending or prevent a decrease (or have a similar effect on taxes).[41]

On the other hand, automatic aid for state and local governments may create a disincentive for them to prepare for economic downturns. To mitigate this issue, federal funding could include requirements to match federal funding or maintain reserves to address unforeseen events, or aid could be provided as loans that must be repaid once revenues are restored.

Automatic Stabilizers Are More Effective When They Are Predictable

One advantage of automatic stabilizers compared to discretionary fiscal policy is that they can be put into place before a crisis occurs. This allows policymakers, administrative agencies, and the public to know what programmatic changes will occur during an economic downturn and plan accordingly. Likewise, quickly implementing new programs in times of crisis can lead to administrative challenges. For example, we previously reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, pressure to quickly implement Pandemic Unemployment Assistance and other new UI program requirements made it difficult for states to establish sufficient controls ahead of program implementation to prevent improper payments.[42]

|

Factor 8: Automatic stabilizer programs are more effective when they are established in advance so that they are ready in times of crisis. |

Establishing policy in advance to support automatic stabilizers’ response to economic downturns can allow time for thoughtful policy design and the development of administrative structures. Such preparation can facilitate implementation of the policy when a crisis occurs.

In cases where state and local governments have a role in program administration, advanced preparation can allow time for effective communication between the federal government and these entities. It can also allow time for state and local governments to develop systems, workforce and technical capacity, and other infrastructure that they would need in times of crisis.

In addition, preparing guidance before a crisis occurs can mitigate potential uncertainty and prevent delays in issuing stimulus when it is needed. Timely guidance from federal agencies can also help state and local governments that have a role in program implementation ensure that they are prepared to meet federal requirements.

Developing a program’s internal controls before an emergency takes place can help federal program managers mitigate improper payments. We previously recommended that Congress consider requiring the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to provide guidance for agencies to develop internal control plans that would immediately be ready to use in, or adaptation for, future emergencies or crises.[43] Preexisting internal control plans should include prepayment controls, such as use of the Do Not Pay working system. This system is operated by the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) and provides a variety of data matching and data analytics services for all federal executive agencies and many state agencies to support their efforts to prevent improper payments. Using the system can help agencies to determine payment eligibility quickly prior to payment issuance. In addition, expedited postpayment controls, such as postpayment reviews and recovery audits, are critical when the quick disbursement of funds makes prepayment controls difficult to fully apply.

When federal funds are distributed before clear guidance for spending and reporting on those funds is available, they may be spent in a way that is later deemed improper. For example, we previously reported that Coronavirus Relief Fund payments to state and local governments were required to be disbursed 30 days after the enactment of the CARES Act, which did not allow time for Treasury to develop guidance in advance.[44] As a result, Treasury made payments while it was still developing guidance and recipient accountability requirements. The Pandemic Response Accountability Committee later reported that Treasury issued three versions of guidance and eight versions of Frequently Asked Questions, which caused confusion, delayed use of the money, and resulted in some ineligible uses of these funds.[45]

Establishing automatic stabilizer programs in advance can also give households and businesses confidence that they will be supported in the event of an economic downturn. For example, workers covered by UI can count on those benefits to replace a portion of their former income if they lose their jobs through no fault of their own. If people do not have confidence that programs like UI will help them during an economic downturn, they may reduce consumption due to financial risks, known as precautionary savings. If a lot of people respond to an economic downturn by spending less and saving more, it could make the downturn worse. On the other hand, predictable federal aid may create disincentives for state and local governments to prepare for economic downturns.

One way to ensure that automatic stabilizers are ready in advance is to use established mechanisms to deliver aid. Using existing systems to deliver aid can help ensure that it is distributed quickly. For example, we previously reported that Congress has leveraged the Medicaid program to quickly increase funding to states and ensure that eligible individuals maintained access to essential health care services during the COVID-19 pandemic and other times of crisis.[46]

|

The United Kingdom (UK) began implementing monthly direct payments to eligible low-income beneficiaries through the Universal Credit (UC) program in 2013 and rolled out UC for new claims nationwide in 2018. This program consolidated multiple low-income programs and tax benefits into a single payment. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of UC claims increased from nearly 3 million in February 2020 to nearly 6 million in February 2021. According to a UK official responsible for administering UC, the UK Department for Work and Pensions was able to quickly process the surge of applications without the need for major changes or updates because the program had online functionality before this sudden increase. |

Source: GAO analysis of UK government documents and information. | GAO‑25‑106455

Well-Designed Triggers Can Enhance Automatic Stabilization

Triggers can also be designed to help enhance the effectiveness of an automatic stabilizer. For example, by initiating changes automatically based on economic indicators, triggers have the potential to match stimulus to real-time economic conditions and mitigate the delays that may occur with discretionary fiscal policy alone.

Delays can occur in part because recessions are officially identified after the fact. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee identifies recessions by retrospectively analyzing economic data, including data on income, employment, consumption, and industrial production.[47] The committee waits until sufficient data are available to avoid the need for major revisions to its determinations.

As a result, NBER typically identifies the start of a recession several months after it actually occurs and identifies the end of recession after it is confident that the economy is recovering. While this approach contributes to the reliability of NBER’s determinations, it means that official recession dates may not be sufficiently timely to use for initiating and ending fiscal stimulus.

In the absence of real-time information about when a recession begins and ends, policymakers can use economic indicators to judge when to act based on current conditions. Indicators can be used to establish triggers for automatic stabilizers, as well as inform discretionary fiscal policy and monetary policy decisions.

Economic policy experts we interviewed said that it can be advantageous to use indicators related to unemployment to trigger automatic stabilizers, compared to economic output data such as gross domestic product. Data on unemployment become available sooner than data on economic output, so they provide a more accurate representation of current economic conditions.

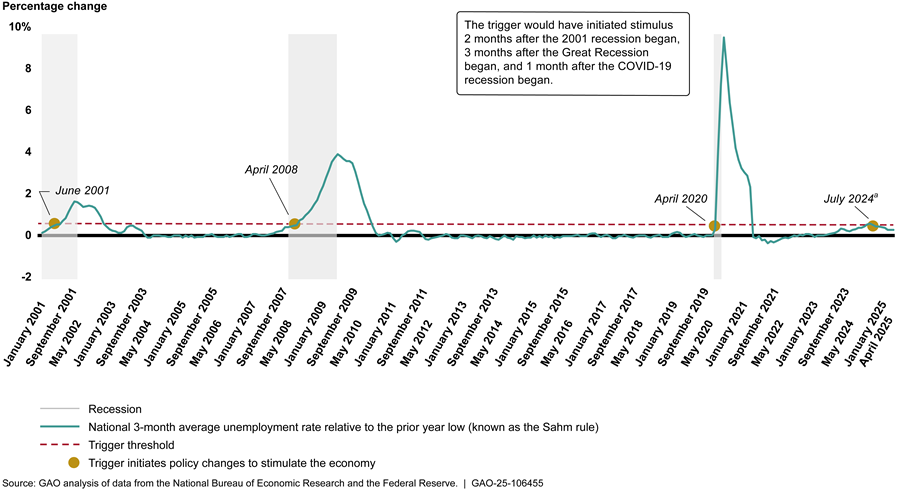

Some studies have proposed indicators based on unemployment data to approximate the start of a recession and trigger stimulus. These studies identified patterns in the data that occurred in past recessions with the goal of providing a timely indicator to show when recessions may occur in the future.[48] Several economic and tax policy experts we interviewed said that policymakers could potentially consider a trigger known as the Sahm Rule, which was proposed in a 2019 study by a former Federal Reserve economist. This study suggests that stimulus could automatically be initiated when the national 3-month average unemployment rate increases by 0.5 percentage points relative to the prior year low.[49]

Potential triggers can be compared to past recession dates to show how accurately they would have predicted those recessions. However, we do not know how accurately they would predict future recessions. The Sahm Rule generally would have started stimulus near the beginning of the past three recessions.

aIn July 2024, the national 3-month average unemployment rate increased by 0.53 percentage points compared to the prior year low. Because this increase exceeded 0.50 percentage points, it met the Sahm Rule’s conditions for beginning fiscal stimulus. It remained above the threshold in August and September 2024 and subsequently fell to 0.43 in October and November 2024.

When a trigger’s conditions for initiating stimulus are met, there can be uncertainty about whether an economic downturn is beginning or if the trigger may activate when a recession is not actually taking place. The economic circumstances of 2024—in which the Sahm rule’s conditions for triggering fiscal stimulus were met for 3 months, as shown in figure 2—illustrate the difficult decisions that policymakers face about initiating stimulus. A trigger that initiates stimulus early could provide support to the economy that is entering a recession. On the other hand, it may risk an unnecessary increase in the federal deficit and potentially overheating the economy if a recession does not occur.

Moreover, whether to use a trigger, and what trigger to use, should be considered in the context of specific policy options. There is no one universally applicable trigger. Triggers that initiate recurring spending, such as changes to the benefits provided by public assistance programs like SNAP, may need to be designed differently than triggers that initiate individual economic impact payments. Examples of triggers designed for specific stimulus policies include:

· Sahm’s 2019 study proposed automatic economic impact payments using a trigger.[50] Specifically, when the national 3-month average unemployment rate increases by 0.5 percentage points relative to the prior year low, it would automatically authorize lump-sum stimulus payments to individuals. Additional payments could potentially be made in subsequent years, depending on the unemployment rate.[51]

· Currently, the Unemployment Insurance (UI) system includes an Extended Benefits (EB) program, which extends the duration of UI benefits to eligible claimants based on the insured unemployment rate and total unemployment rate in each state.[52] The threshold that must be reached to trigger EB, and the additional duration of benefits provided when EB activates, varies by state.[53] One study we reviewed analyzes potential alternative triggers for EB using the Sahm Rule to more closely link EB triggers with economic conditions.[54] The study found that the Sahm Rule would trigger EB earlier in a recession, when unemployment is low but starting to rise.

· We have previously proposed a prototype formula for automatically adjusting the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) formula—which sets the percentage of federal assistance for state Medicaid expenditures—during economic downturns.[55] Our prototype formula would use the monthly employment-to-population ratio to trigger an FMAP increase. The trigger would activate when the 3-month average of this ratio decreases in 26 states, compared to the same 3-month period in the previous year, over 2 consecutive months.

While triggers may be designed to enhance timeliness of economic stimulus, they could also align with other factors for effective automatic stabilizers described above:

· Temporary. Triggers can specify conditions for ending stimulus when economic indicators suggest it is no longer necessary. By ending stimulus as economic conditions improve, triggers can help prevent stimulus from lasting too long.

· Targeted. Triggers could also help ensure that stimulus is targeted to the severity of an economic downturn. For example, they can be designed to distribute stimulus based on economic conditions in each state.

· Predictable. Because triggers use a predetermined set of rules, they can help ensure that households, businesses, and state and local governments will know how the federal government will use fiscal stimulus to respond to an economic downturn.

Options to Strengthen Automatic Stabilizers Involve Trade-Offs

Based on a review of relevant literature and interviews with knowledgeable experts, we identified 17 potential policy options to strengthen automatic stabilizers, as shown in table 2.[56] Our list is not comprehensive of all policy options for enhancing automatic stabilizers. We have previously recommended that Congress consider taking action that would enhance Medicaid as an automatic stabilizer.[57] Other than that previous recommendation, we do not endorse any specific policy option.

|

Policy Area |

Policy Option |

|

Unemployment Insurance (UI) |

1. Temporarily expand UI eligibility |

|

2. Temporarily increase weekly UI benefit amounts |

|

|

3. Temporarily increase the duration of UI benefits |

|

|

Short-time work programs |

4. Temporarily federally fund the Short-Time Compensation program |

|

5. Expand short-time work programs to all states |

|

|

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) |

6. Temporarily increase SNAP benefit amounts |

|

7. Temporarily suspend SNAP time limit and work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents |

|

|

8. Temporarily waive certain SNAP administrative requirements |

|

|

9. Temporarily increase federal SNAP administrative funding to states |

|

|

Medicaid |

10. Adjust the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage formula to be responsive to economic conditions |

|

Tax system |

11. Provide direct payments to individuals and families through the tax system |

|

12. Temporarily reduce employee payroll taxes |

|

|

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) |

13. Temporarily allow taxpayers the option to include or exclude UI compensation when calculating EITC |

|

14. Temporarily increase EITC amounts for eligible taxpayers without qualifying children |

|

|

15. Temporarily allow taxpayers the option to use income from a prior year to calculate for EITC amounts |

|

|

16. Temporarily increase the EITC phase-in rate |

|

|

Child Tax Credit |

17. Temporarily provide an advance Child Tax Credit |

Source: GAO analysis of information from literature and interviews with experts. | GAO‑25‑106455

Note: These potential policy options are not listed in any specific order. We have previously recommended that Congress consider taking action that would enhance Medicaid as an automatic stabilizer. Other than that previous recommendation, we do not endorse any specific policy option.

For each of these options, we provide a brief background of the policy area, a description of the policy option, and an overview of any related actions that the federal government has taken to address past emergencies, such as economic downturns or natural disasters.

All these policy options have strengths and limitations. Below we provide a list of general trade-offs that are broadly applicable to many of the options. In addition to these general trade-offs, for each of the policy options we include a description of option-specific trade-offs and considerations, where applicable. Our list of trade-offs is not a comprehensive list of all potential strengths or limitations.

Each policy option could be implemented in different ways that could influence its effectiveness. Therefore, for each option, we include a list of selected questions for policymakers based on our analysis of relevant literature, interviews with knowledgeable experts, and temporary policies from prior economic downturns.

We did not examine how the different policy options could interact with each other or how the effectiveness of certain policies could be changed if paired or substituted with other policies. Specifically, there could be potential implications of enacting multiple automatic and discretionary policies at the same time.

Trade-Offs and Other Considerations for Strengthening Automatic Stabilizers

Some general trade-offs and considerations that are broadly applicable to many of the policy options include:

Economy. Generally, strengthening automatic stabilizers can help households, businesses, and state and local governments maintain spending during economic downturns, which can increase demand for goods and services, thus bolstering economic activity. However, an automatic fiscal response that generates a large increase in spending could have other important economic effects, such as contributing to inflation.

Federal budget. During economic downturns automatic stabilizers typically result in more federal spending and less revenue, which temporarily increases budget deficits. Strengthening the current automatic stabilizers by increasing benefit amounts or changing eligibility requirements could further increase federal spending or reduce tax revenue. However, some enhanced automatic stabilization could take the place of typical discretionary action that may not be as timely, targeted or predictable. Nevertheless, automatic stabilizers should be designed with careful consideration for balancing budgetary costs with the benefits of stabilization to the economy and the well-being of individuals and families. Over the long term, a strong economy can improve the federal government’s fiscal health.[58]

State budgets. During economic downturns, state tax revenue typically declines. Because states generally have a requirement to balance their respective budgets, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers, this revenue loss could potentially lead to spending cuts, which could limit recovery efforts and prolong downturns. Enhancing automatic stabilizers—which include several programs that are federal-state partnerships—can help remove some of the fiscal risk to states by shifting some spending from states to the federal government. However, if fiscal risks are shifted from states to the federal government, states might have less incentive to prepare for economic downturns, such as by saving for such contingencies (e.g., through a rainy day fund).[59]

Individuals and families. Automatic stabilizers can help support the well-being of individuals and families with the greatest need during economic downturns. For example, we previously found programs with automatic stabilizer mechanisms help to reduce uncertainty when individuals experience the effects of an economic downturn, like job loss and food insecurity.[60]

Administration. Using and enhancing the administrative systems of existing automatic stabilizers could be more efficient than designing and implementing new programs. However, programmatic changes to automatic stabilizers may necessitate administrative changes, such as updates to processes, guidance, or information technology systems. These changes could lead to the federal government and state governments increasing (1) time spent on administrative activities; (2) costs, such as IT costs; or (3) compliance and oversight workload.

Improper payments. Automatically expanding eligibility or increasing benefit amounts absent appropriate capacity in administrative controls could increase the risk of improper payments. An improper payment is any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount, including both overpayments and underpayments. They can be caused by either deliberate misrepresentation of information—known as fraud—or unintentional mistakes. Examples of improper payments include payments to an ineligible recipient, payments for ineligible goods or services, and duplicate payments. For example, we previously estimated that the amount lost to fraud in UI programs during the pandemic—from April 2020 through May 2023—was likely between $100 billion and $135 billion.[61]

Strengthening automatic stabilizers by better planning for and taking a more strategic approach prior to an economic downturn could help prevent or mitigate improper payments. Congress and federal program managers could design and implement internal controls that allow assistance to be disbursed rapidly while mitigating identified risks of improper payments, including those resulting from fraudulent activity.[62]

Trigger design. Well-designed triggers can help ensure that automatic stabilizers are timely, temporary, targeted, and predictable. Because triggers encompass (1) what indicator would initiate additional automatic fiscal action, (2) how soon in an economic downturn it would be initiated, and (3) how long it would be in place, they should be designed thoughtfully for each program to ensure that they are appropriate. However, designing triggers may be challenging, in part because it is difficult to accurately assess economic conditions in real time.

Policy Area: Unemployment Insurance

The UI system is a federal-state partnership that provides income support to workers who have lost employment through no fault of their own.[63] Under this arrangement, states design and administer their programs within federal parameters.[64] The Department of Labor (DOL) has general responsibility for overseeing the UI program to ensure that states are operating the program properly and efficiently. For example, DOL is responsible for monitoring state operations and procedures, providing technical assistance and training, and analyzing UI program data to diagnose potential problems.

UI acts as an automatic stabilizer because UI enrollment increases during economic downturns as more people lose jobs and become eligible for benefits. Qualified unemployed workers receive benefits after filing a claim with the UI program in the state where they worked. UI benefits play an important role in supporting the economy during downturns by giving households resources to continue spending on basic living expenses. Use of UI benefits decreases as the economy recovers and more individuals find employment.

UI benefits are funded primarily through state taxes levied on employers.[65] The benefits replace a portion of a claimant’s previous employment earnings.[66] States have discretion on the maximum number of weeks of regular UI benefits to offer, with current durations ranging from 12 to 28 weeks, according to DOL.[67] The UI system includes the Extended Benefits (EB) program where states extend UI benefits for up to an additional 13 weeks under certain economic conditions. Some states have added an additional 7 weeks of extended benefits, up to 20 weeks, according to DOL.[68] EB funding is typically split equally between the states and the federal government; however, in past recessions the federal government has taken discretionary action to fully fund them.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, UI benefit uptake surged at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, as initial UI claims rose nearly 3,000 percent from about 200,000 per week to more than 6 million per week during late-March and early-April 2020.[69] EB was triggered in all states except South Dakota during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to DOL.[70]

The UI system faces systemic challenges that affect its ability to meet the needs of unemployed workers during nonrecessionary times as well as during economic downturns. We have identified challenges such as staffing limitations, outdated IT infrastructure, increased improper payments, and limited effectiveness of triggers for the EB program.[71] In 2022, we reported that program variation across states contributed to disparities in worker access and benefit distribution.[72] We also found that continued use of legacy IT systems hindered states’ abilities to implement new programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. We added UI to our High-Risk List in 2022 based on these ongoing challenges and the risks they pose to service delivery and financial costs.[73]

In April 2024, in response to our high-risk designation and recommendation, DOL released a comprehensive plan for transforming the UI system. The plan includes strategies for modernizing state UI infrastructure and increasing states’ administrative capacity, as well as recommendations for legislative changes to improve the UI system.[74] These strategies and changes include adequately funding state UI administration, improving the resilience and responsiveness of state IT systems, bolstering state UI programs against fraud, and addressing funding challenges for state UI benefits. In our most recent High Risk report, DOL officials told us that 47 of the 53 actions in the agency’s UI transformation plan were completed or underway as of December 2024.[75]

Based on our review of literature and interviews with economic policy and UI experts, policymakers have various options to make the UI system more responsive to economic downturns (see options 1-3 below). Each of these options has trade-offs and other considerations. For example:

· Automatically initiating temporary changes to UI eligibility, benefit amounts, or duration could strain state budgets.

· States may not have the administrative capacity and IT capabilities to implement these policy options without first addressing systemic UI infrastructure challenges.

· The risk of fraud and other improper UI payments could increase if state systems lack appropriate capacity for managing changes in benefit eligibility, amounts, and duration.

These policy options also could help households maintain an income source and their ability to contribute to the economy during an economic downturn. We previously reported that UI and other social safety net programs helped stabilize income and prevented rises in poverty during recent economic downturns.

Option 1: Temporarily Expand UI Eligibility

Our literature review and interviews with economic policy and UI experts found that temporary, automatic adjustments to eligibility during economic downturns could allow UI to expand to populations that typically do not have access to benefits. This expansion would increase the number of unemployed individuals who are eligible for UI benefits. For example, individuals who are self-employed, independent contractors, and gig workers are typically ineligible for UI benefits. We have previously reported that workers in these categories may experience lower job stability and receive fewer benefits, which may leave them more vulnerable during recessions.[76]

|

Previous Discretionary Actions The federal government temporarily expanded Unemployment Insurance (UI) eligibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. · The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program authorized UI benefits for individuals not otherwise eligible for UI benefits who were unable to work as a result of specified COVID-19-related reasons. PUA initially provided for up to 39 weeks of benefits and was subsequently authorized to provide up to a total of 79 weeks of benefits. Initially, applicants only self-certified that their unemployment or inability to work was due to one of the COVID-19-related reasons, increasing the risk of fraud and error. Subsequently, applicants generally were required to provide documentation substantiating their employment or self-employment. PUA expired in September 2021. · The Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation (MEUC) program was intended to cover regular UI claimants whose benefits did not account for significant self-employment income and who thus may have received a lower regular UI benefit than they would have received had they been eligible for PUA according to the Department of Labor (DOL). MEUC provided $100 per week to individuals who received at least $5,000 in self-employment income in the most recent tax year. The $100 weekly benefit was in addition to other UI benefits received by claimants, however, individuals receiving PUA were ineligible for MEUC payments. MEUC was payable only in states that opted to administer the benefit. MEUC expired in September 2021. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOL guidance and the CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, 134 Stat. 1182 (2020); the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 4 (2021). | GAO‑25‑106455

However, automatically initiating a temporary expansion of UI eligibility could affect the solvency of state budgets. States have UI trust fund reserves to pay for UI benefits, which are primarily funded through state taxes on employers. Workers who may qualify for UI benefits during this eligibility expansion, such as self-employed individuals or gig workers, may not have employers who would typically pay into UI trust funds. This difference in program spending and revenue could potentially contribute to challenges with solvency of those funds during a recession.

In evaluating this option, policymakers could consider: