SUBMINIMUM WAGE PROGRAM

Employment Outcomes and Views of Former Workers in Two States

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106471. For more information, contact Elizabeth H. Curda at EWISInquiry@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106471, a report to congressional requesters

Employment Outcomes and Views of Former Workers in Two States

Why GAO Did This Study

The 14(c) program originated from a provision of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Almost 40,000 people with disabilities were working under 14(c) certificates as of November 2024. Proposed federal legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates has raised questions about what happens to people when the program is eliminated.

GAO was asked to review the effects of eliminating the use of 14(c) certificates on 14(c) workers. This report examines (1) which states have eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates and are collecting outcome data on former employees, (2) post-14(c) employment outcomes in two selected states, and (3) the views of people who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers in selected states about the transition away from 14(c) employment.

GAO selected a nongeneralizable sample of two states, selected in part because they collected multiple years of relevant data. In Colorado, GAO analyzed data on former 14(c) workers from July 2021 to February 2024. In Oregon, GAO analyzed data on former 14(c) workers from July 2014 to April 2024. GAO also conducted in-person interviews with a nongeneralizable sample of 19 individuals from these two states who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers, selected to represent a range of experiences with the transition out of 14(c) employment in rural and urban settings.

What GAO Found

As of January 2025, 16 states had enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates, according to the Department of Labor (DOL) and state officials. DOL can grant these certificates to employers to pay wages below the federal minimum to certain individuals with disabilities. These states enacted legislation between 2015 and 2025, according to DOL and state officials.

GAO’s analysis of data from two selected states that eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates—Colorado and Oregon—provides a partial picture of outcomes in those states. As of 2023 (the most recent data available), fewer than half of the approximately 1,000 people these states were able to track had moved from 14(c) to some other type of employment. This included competitive integrated employment (CIE), which entails earning a competitive wage at or above the federal minimum alongside people without disabilities. The remaining 54 to 61 percent of people the states were able to track were not working but were receiving non-employment services funded by Medicaid, such as day services to build socialization and daily living skills. Both states were not able to easily track outcomes for people who no longer received Medicaid services. Those individuals may or may not be working; may have chosen to retire; may have lost eligibility; or may no longer be living, according to state officials.

People who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers in the selected states discussed positive and challenging experiences related to 14(c) employment and CIE. For both types of employment, more interview participants discussed positive experiences than challenging ones. For instance, people frequently cited liking the tasks they completed and the interpersonal relationships they had in both 14(c) employment and CIE. People also discussed a range of experiences with their transition out of 14(c) employment, such as opportunities for new social connections and challenges related to finding CIE.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ABLE |

Achieving a Better Life Experience |

|

CIE |

Competitive integrated employment |

|

DOL |

Department of Labor |

|

EOS |

Employment Outcomes System |

|

HCBS |

Home- and community-based services |

|

I/DD |

Intellectual or developmental disabilities |

|

SSI |

Supplemental Security Income |

|

VR |

Vocational Rehabilitation |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 29, 2025

The Honorable Tim Walberg

Chairman

Committee on Education and Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Virginia Foxx

House of Representatives

The Honorable Glenn Grothman

House of Representatives

Under Section 14(c) of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, the Department of Labor (DOL) may authorize employers to pay wages below the federal minimum (also known as “subminimum” wages) to individuals with disabilities if their earning or productive capacity is limited because of their disability.[1] This provision is intended to prevent the curtailment of employment opportunities. Almost 40,000 people with disabilities were employed under 14(c) certificates as of 2024.[2] Such employment often takes place in a sheltered workshop setting, where all employees have disabilities—typically an intellectual or developmental disability (I/DD).

In recent years, there has been an increased emphasis on competitive integrated employment (CIE) for people with disabilities. In 2014, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act amended the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 to state that one of its purposes is “to maximize opportunities for individuals with disabilities, including individuals with significant disabilities, for [CIE].”[3] In contrast to employment in sheltered workshops at subminimum wages under 14(c) certificates, CIE entails earning a competitive wage at or above the federal minimum in an integrated employment setting where workers with disabilities interact with other people without disabilities to the same extent that workers without disabilities do.

Federal legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) has been proposed several times, and in December 2024, DOL issued a notice of proposed rulemaking proposing to stop issuing new 14(c) certificates and phase out existing certificates.[4] In addition, some states have enacted legislation eliminating subminimum wages for individuals with disabilities (including those earned at sheltered workshops). Questions have been raised, however, about employment outcomes for these individuals when the use of 14(c) is eliminated.

You asked us to review the effects of eliminating the use of 14(c) on the employment of individuals with disabilities. This report examines: (1) which states have enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates and are collecting data on employment outcomes for people who worked in the program, (2) employment outcomes for people with disabilities who worked in the 14(c) program in selected states, and (3) the views of people and their caregivers in selected states about their transition out of 14(c) employment, including opportunities and challenges.

To examine states’ data collection, we obtained information on which states had enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates as of January 2025 from DOL officials, selected experts on the employment of people with disabilities and related state data, key stakeholder organizations, and publicly available sources such as state websites.[5] We sent questionnaires to cognizant state officials in the 16 states we identified and asked them to confirm or correct information we gathered, such as information about their state laws and whether they are collecting data on employment outcomes. We received responses from all 16 states we queried. We also used this information to select states to serve as illustrative examples for our other two objectives. We initially selected three states (Colorado, Maryland, and Oregon) because they had multiple years of relevant data on outcomes and had eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates recently enough that individuals who formerly worked in the program and their caregivers could more easily speak to their experiences with the transition. Specifically, we selected states where this transition was ongoing, or was completed no earlier than 2020. Maryland officials declined to participate in in-depth interviews for this study and to share data at an individual level, citing staff capacity issues.

To understand employment outcomes, we analyzed the most recently available, anonymized data provided at the individual level by the two states that agreed to participate in our study (Colorado and Oregon). In Colorado, we analyzed information regarding each worker’s transition out of 14(c) employment provided by 14(c) employers from July 2021 through June 2023 and data the state collected on Medicaid services provided to people who formerly worked in 14(c) employment from July 2021 through February 2024.[6] In Oregon, we used data the state collected from 14(c) employers and other Medicaid service providers in their Employment Outcomes System (EOS) on each worker’s transition, as well as data on services provided by Medicaid, from September 2015 through September 2023.[7] We also analyzed data on Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) services provided to the same population from July 2014 through April 2024.

We assessed the reliability of relevant variables by conducting electronic data tests for completeness and accuracy, reviewing documentation, and interviewing knowledgeable officials about how the data were collected and maintained and their appropriate uses. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable to describe what is known about employment outcomes in Colorado and Oregon for people who formerly worked in 14(c) employment.[8] To add context to our findings and better understand the landscape of the two selected states, we interviewed relevant state agency officials, such as those from developmental disabilities services agencies, and five selected stakeholders involved in transition efforts.[9] Employment outcomes we observed in these two states are not generalizable to all states that have eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates.

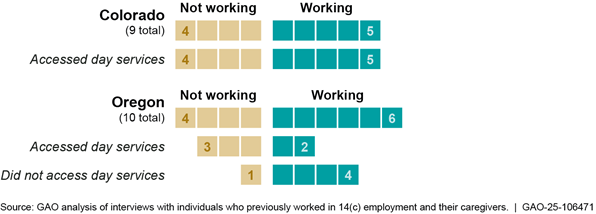

To obtain the views of those who were affected by the elimination of the use of 14(c) certificates, we conducted in-person interviews with 19 people who previously worked in 14(c) employment in Colorado and Oregon; in most cases we also interviewed a caregiver (a family member, guardian, or other support person of the individual’s choosing). We worked with state officials, case managers, former 14(c) employers, and others to identify people with a range of experiences, including those working and not working and those in both rural and urban areas. We interviewed 11 people who were working in CIE and eight who were not working and either attended a day services program or did not receive services.[10] The perspectives of the people we interviewed are not generalizable to all people participating in 14(c) employment. For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2022 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

14(c) Employers and Employees

Section 14(c) of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 allows DOL to certify employers to pay subminimum wage rates in certain circumstances. Under the law, such wages must be related to the productivity of the individual completing the work. Section 14(c) certificate holders, referred to in this report as 14(c) employers, can be private businesses but are often nonprofit agencies or organizations, known as community rehabilitation programs, that provide rehabilitation and skills training to people with disabilities.[11] In a prior survey of community rehabilitation programs that were 14(c) employers, we found that an estimated 70 percent of workers received day services that were provided directly from or organized by their employers.[12] These included non-work activities or services to help build socialization and daily living skills and may have taken place at a facility owned by the service provider or out in the community.

Most individuals employed in the 14(c) program have I/DD.[13] I/DD includes a range of conditions that are present from childhood and can require lifelong care and support. Examples of I/DD include Down syndrome and autism spectrum disorder—conditions that may result in difficulties with learning, problem solving, and the ability to acquire and use everyday life skills.

Federal and State Programs That Support People with I/DD

Medicaid is the nation’s primary payer of long-term services and supports for individuals with I/DD. Medicaid is a joint federal-state health care financing program for certain low-income and medically needy individuals that is overseen at the federal level by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services within the Department of Health and Human Services and administered at the state level by individual state Medicaid agencies. Long-term services and supports provided through Medicaid encompass a broad set of health care, personal care, and supportive services. Service providers, such as community rehabilitation programs that deliver long-term services and supports outside of institutional settings, are known as home- and community-based services (HCBS) providers. These services may include day services, behavioral support, and supported employment—assistance with gaining and maintaining employment in an integrated setting.[14] In 2014, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a final rule establishing certain requirements for the settings in which HCBS could be provided, aimed at maximizing opportunities to receive services in the most integrated community-based settings.[15]

The VR program provides services, including counseling and training, that, among other things, help people with disabilities obtain CIE. The Department of Education oversees VR program funding and distributes it as grants to the state agencies that administer the program. To be eligible for VR services, an individual must have an impairment that constitutes a substantial impediment to employment and must be able to benefit from VR services in terms of an employment outcome.

Individuals with disabilities also may qualify for benefits unrelated to their employment, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Administered by the Social Security Administration, SSI is a federal benefit program that pays monthly benefits to certain individuals with limited income and resources who are aged, blind, or have a disability. To be eligible for the program on the basis of a disability, an adult must have a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that (1) has lasted or is expected to last for a continuous period of at least 1 year or is expected to result in death and (2) prevents them from engaging in substantial gainful activity—generally considered by the Social Security Administration to be earning above a certain monthly amount.[16]

Movement from 14(c) to CIE

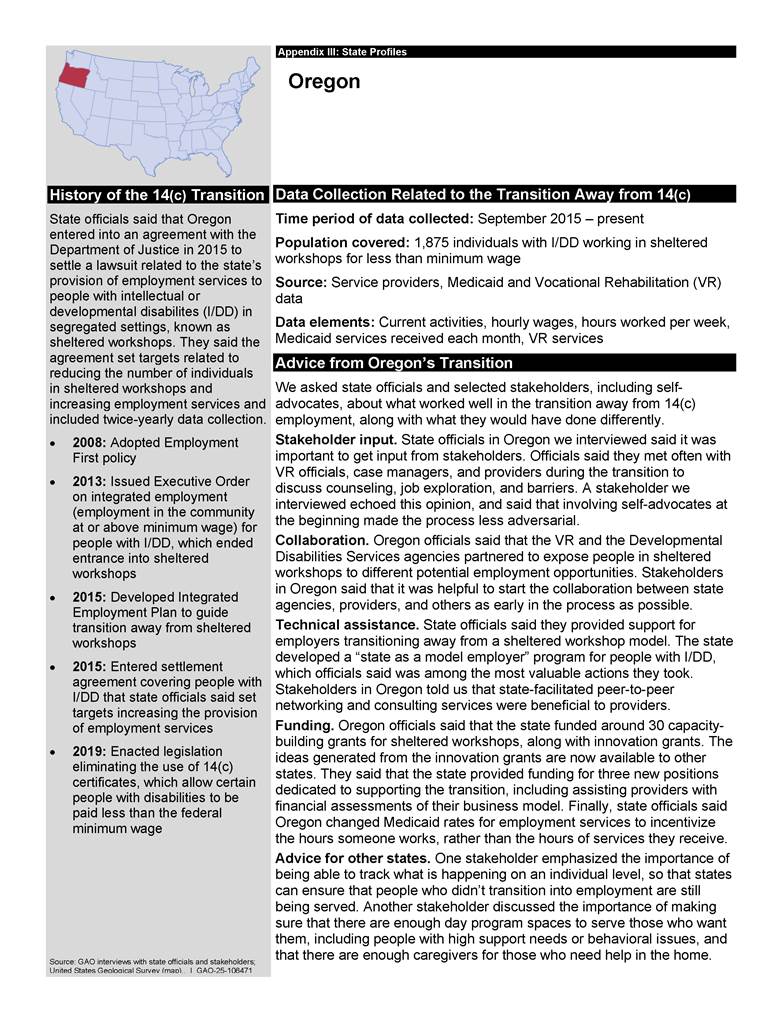

Our prior work identified a number of factors that influence whether and how individuals move out of 14(c) employment and into CIE.[17] Figure 1 shows these factors, which we identified through interviews with experts and state officials.

Figure 1: Factors That Influence Transition from 14(c) Employment to Competitive Integrated Employment (CIE)

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying certain individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage, often in a sheltered workshop setting where most employees have disabilities.

aSection 511 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires that individuals receive, as a condition of 14(c) employment, regular career counseling and information designed to enable the individuals to explore, discover, experience, and attain CIE.

In December 2024, DOL published a framework for increasing CIE through state policy. According to DOL, this framework identifies barriers to increasing CIE and describes how policy and practice can promote CIE at the state level throughout the nation.

Available State Data on Post-14(c) Employment Outcomes

How many states have enacted legislation eliminating the use of 14(c) certificates?

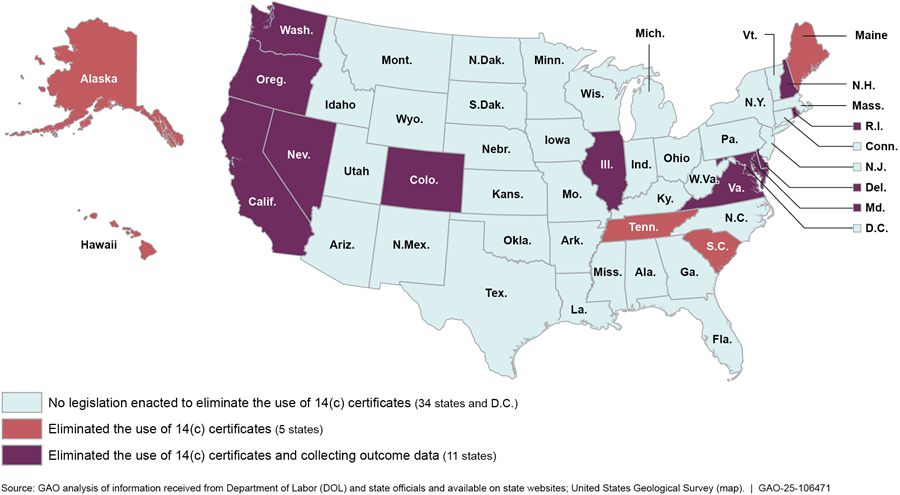

In 2014, all states except Vermont had at least one active 14(c) certificate, according to our prior analysis of DOL data.[18] From 2015 to January 2025, however, 16 states enacted legislation eliminating the use of 14(c) certificates, according to DOL and state officials. These states are: Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington. See the subsequent question and appendix II for more information about these states. As of November 2024, 37 states had at least one active 14(c) certificate. Some states may have taken steps other than enacting legislation to reduce the use of 14(c) certificates, such as no longer allowing Medicaid funding to be used for services provided through 14(c) employment.

What data on employment outcomes are available for states that have enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates?

No federal data sets systematically collect data on individuals transitioning out of 14(c) employment, according to DOL officials. Existing federal data sets are generally tied to whether people receive services from specific federal programs. For example, people in 14(c) employment may receive Medicaid services, such as supported employment (e.g., job coaching) or day services, but Medicaid data do not specifically identify those individuals as 14(c) workers.[19] Limited data on some 14(c) workers, such as their wages in one specific quarter within a 2-year period as reported by their employer when applying for a section 14(c) certificate, are available from DOL’s system for processing 14(c) certificates. However, these data do not include Social Security numbers or other unique identifiers, making it difficult to match with other federal data sources. In addition, according to Department of Education officials, the VR data system collects information on whether someone receiving VR services was referred to the program by a 14(c) employer.[20] At the same time, not all people who worked in 14(c) employment seek VR services.[21]

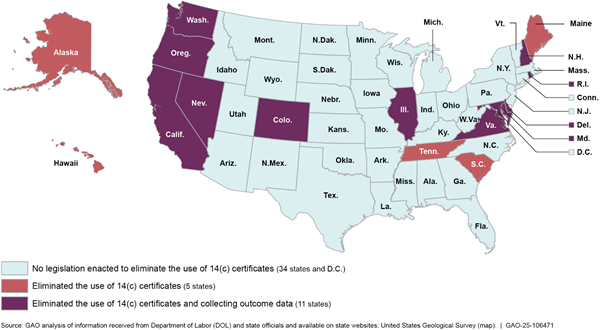

In the absence of federal data, some states are collecting information on employment outcomes for people who used to work in 14(c) employment. According to DOL and state officials, of the 16 states that have enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates as of January 2025, 11 reported collecting or planning to collect data on employment outcomes of people who transitioned out of such employment (see fig. 2). These 11 states reported collecting specific data at the individual level, such as hours worked, wages earned, movement to CIE or unpaid activities, and employment status.

Figure 2: States That Have Enacted Legislation Eliminating the Use of 14(c) Certificates as of January 2025, According to DOL and State Information

Note: 14(c) certificates are issued by DOL and permit employers to pay certain individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage.

Some states enacted legislation in recent years and either had not yet begun collecting data or had data covering a short period of time. Other states had few or no individuals working in 14(c) employment at the time legislation was enacted. As mentioned previously, we selected Colorado and Oregon because they agreed to share multiple years of relevant data on outcomes, among other factors.

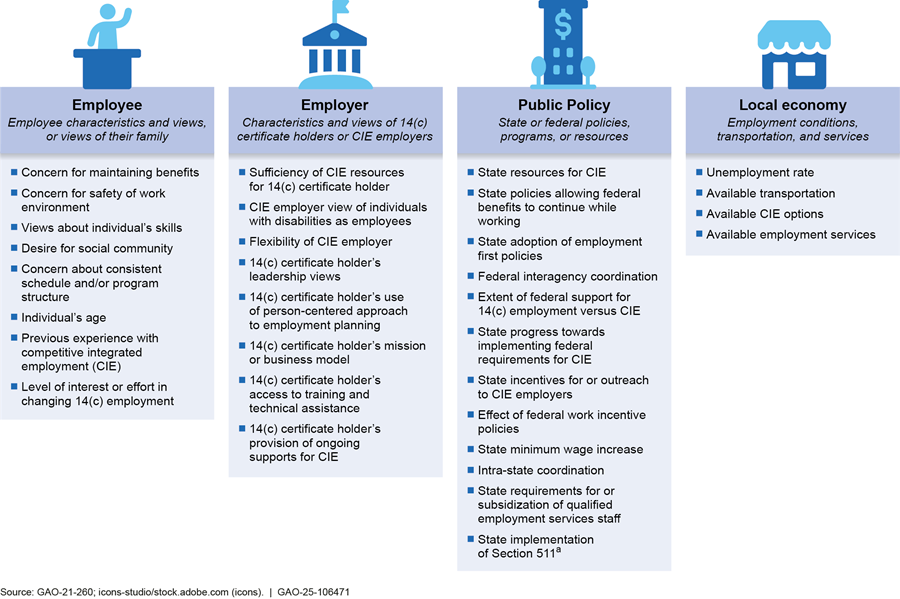

Colorado enacted legislation to phase out the use of 14(c) certificates from July 1, 2021, through July 1, 2025. State officials reported that by July 1, 2023, there were no longer any individuals employed under 14(c) certificates in Colorado. The legislation required employers holding 14(c) certificates to report on workers’ initial placement after leaving 14(c) employment, including the number of individuals who went into CIE or day services and their wages and hours worked, as applicable. State officials said that the 195 people in 14(c) employment at the time the legislation went into effect and for whom data were collected represent a smaller subset of the people who had worked in 14(c) employment in the state. For example, they said that about 500 people in the state worked in 14(c) employment at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to state officials, Oregon entered into an agreement with the Department of Justice in 2015 to settle a lawsuit related to the state’s provision of employment services to people with I/DD in segregated settings, such as sheltered workshops. Officials said the agreement, which did not specifically involve 14(c) employment but did involve sheltered workshops, set targets such as reducing the number of individuals in sheltered workshops and increasing the provision of employment services.[22] They said it also required that the state track data on the types of supported employment services each person covered by the settlement agreement received, along with wages, and hours worked for those who were employed. Officials told us the state was tracking 1,875 individuals who were working for less than minimum wage in September 2015.[23] Oregon subsequently enacted legislation in 2019 that eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates.[24] See appendix III for more information on our selected states.

Post-14(c) Employment Outcomes in Selected States

What are the employment outcomes for workers in selected states after leaving 14(c) employment?

Our analysis of data from Colorado and Oregon provides a partial picture of employment outcomes in those states, given data limitations. Both selected states track individuals primarily using data on Medicaid services and additional information, such as wages and hours worked, provided by former 14(c) employers or service providers. As a result, neither state was easily able to track long-term outcomes for all individuals who worked in 14(c) employment, particularly if individuals stopped receiving Medicaid services. For example, individuals who no longer receive Medicaid-funded services may or may not be working; may have chosen to retire; may have lost eligibility; or may no longer be living. We discuss these limitations further in a subsequent question about why selected states were unable to track outcomes for certain people who worked in 14(c) employment.

The data nevertheless provide insights into employment outcomes for a significant number of people who worked in 14(c) employment in these states. For example, Oregon’s data tracks individuals with I/DD who receive supported employment services from Medicaid and flags those who were paid less than minimum wage. As a result, the data do not include individuals with other types of disabilities working in 14(c) employment or those who were earning higher wages before their transition out of 14(c) employment. At the same time, our prior work suggests that Oregon’s data include the vast majority of individuals who worked in 14(c) employment at the time.[25]

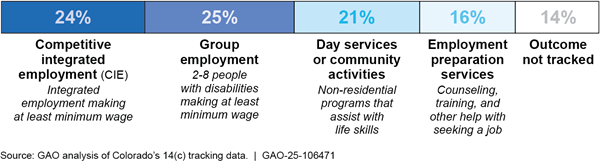

Colorado

Of the 195 people in 14(c) employment immediately before Colorado’s transition away from 14(c) employment, about half moved to CIE or supported group employment (where groups of two to eight individuals with disabilities work together), according to state data on workers’ initial placements gathered between July 2021 and June 2023 (see fig. 3).[26] More than a third were participating in Medicaid employment preparation services or day services. Fourteen percent were not included in this initial placement data for a variety of reasons, including because they left their 14(c) employer prior to the state’s transition away from 14(c) employment.[27]

Figure 3: Colorado Workers’ Initial Placements after Leaving 14(c) Employment, July 2021 – June 2023

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. These data, collected from former 14(c) employers during a 2-year period and verified by Colorado officials in February 2024, represent initial placements for 195 individuals after they left 14(c) employment during the state’s transition away from 14(c) employment. According to state officials, the state did not require employers to continue to track workers after these placements. As a result, the data do not provide information on any subsequent changes in employment. In addition, employer-reported information covers the employment that these individuals engaged in and, if not employed, the non-employment services or activities individuals received. To avoid double-counting, the data capture one outcome for each individual, with a priority on employment. For example, a person working in group employment may have also received day services, but this figure reflects their employment.

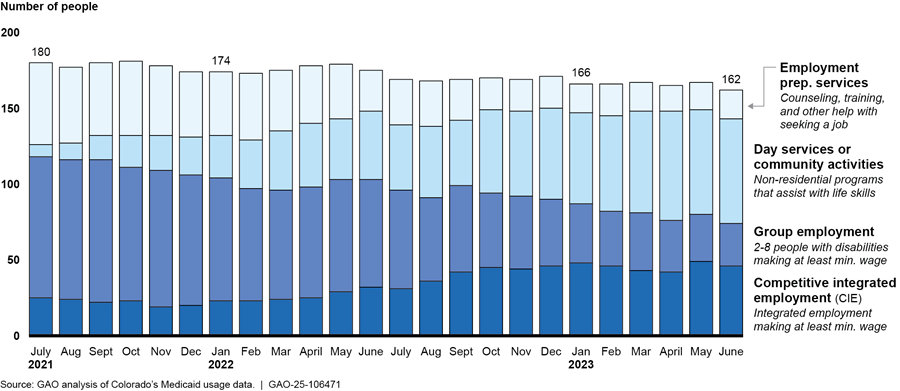

Another data source provides additional insight into outcomes for many of the 195 former 14(c) workers over time.[28] During the state’s transition away from 14(c) employment, the number of people working with Medicaid-funded supported employment decreased while use of day services or community activities increased, according to our analysis of data from July 2021 through June 2023 (see fig. 4).[29] At the same time, the share of those receiving Medicaid-funded supported employment who were working in group employment during this period fell while the share working in CIE doubled, from 14 to 28 percent.[30] As of February 2024, almost 20 percent of the former 14(c) workers were no longer included in the Medicaid data. For more information, see the subsequent question about why selected states were unable to track outcomes for certain people who worked in 14(c) employment.

Figure 4: Use of Medicaid Supported Employment and Other Services among Coloradans Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment, July 2021-June 2023

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. This figure includes individuals who were working in 14(c) employment and also may have been receiving Medicaid services immediately before the state’s transition away from 14(c) employment began in July 2021. Individuals may have received more than one Medicaid service in any given month. To avoid double-counting, the figure shows each individual once per month in which they received any of the designated Medicaid services, in the following priority order: (1) supported employment for CIE, (2) supported employment for group employment, (3) employment preparation, or (4) day services or community activities. For example, a person receiving supported employment services for group employment may have also received day services during the same month, but this figure reflects their employment. See appendix I for more information on our data analysis, including additional analysis of certain individuals who received more than one service.

Put differently, for the 162 individuals remaining in Colorado’s data as of June 2023, 46 percent were receiving Medicaid-funded supported employment services, including 28 percent working in CIE. The remaining individuals were not receiving employment services and were receiving either employment preparation services (12 percent) or day services (43 percent).[31]

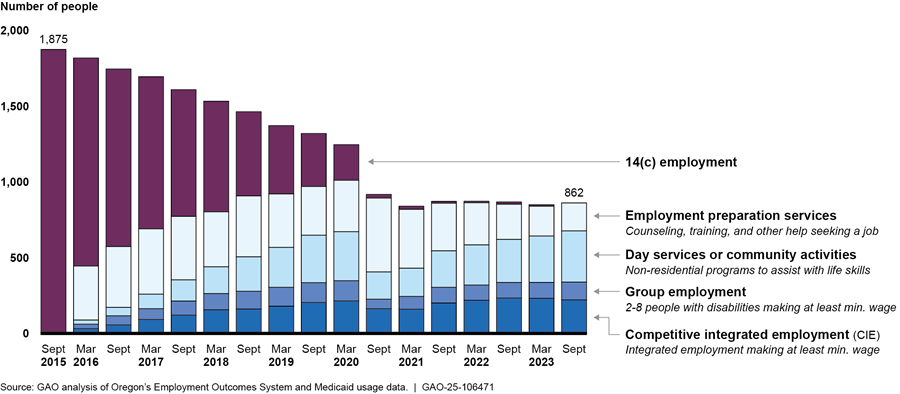

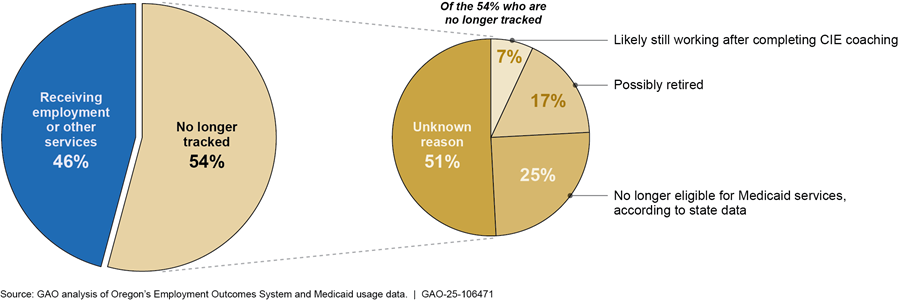

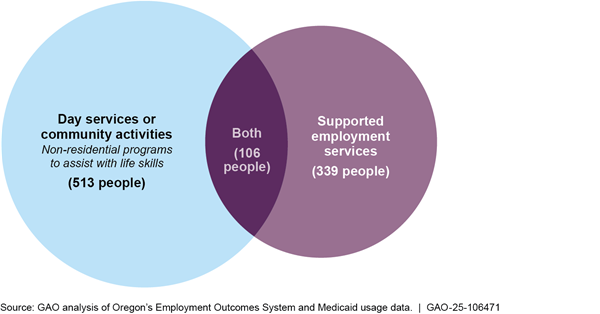

Oregon

Of the 1,875 individuals Oregon officials were tracking in September 2015, 18 percent were working in CIE (12 percent) or group employment (6 percent) with Medicaid-funded support in September 2023, according to the state’s Medicaid service and EOS data.[32] Another 28 percent were receiving employment preparation or day services, but not working. Finally, 54 percent were no longer included in the state’s data as of September 2023 (see fig. 5). For more information on these individuals, see the subsequent question about why selected states were unable to track outcomes for certain people who formerly worked in 14(c) employment.

Figure 5: Use of Medicaid Supported Employment and Other Services among Oregonians with I/DD Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment, September 2015-September 2023

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. This figure includes 1,875 individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) who were receiving Medicaid supported employment services in September 2015 and working for less than the Oregon minimum wage in 14(c) employment. Individuals may have received more than one Medicaid service in any given month. To avoid double-counting, the figure shows each individual once per month in which they received any of the designated Medicaid services, in the following priority order: (1) services for 14(c) employment, (2) supported employment for CIE, (3) supported employment for group employment, (4) employment preparation, or (5) day services or community activities. For example, a person receiving supported employment services for working in group employment may have also received day services, but this figure reflects their employment. See appendix I for more information on our data analysis, including additional analysis of certain individuals who received more than one service.

For the 862 former 14(c) workers that Oregon was able to track as of September 2023, 39 percent were receiving Medicaid-funded employment support services, including 26 percent working in CIE. The remaining individuals were not receiving employment services and were instead receiving either employment preparation services (21 percent) or day services (nearly 40 percent).

|

Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Employment Outcomes in Oregon In addition to Medicaid service data, VR data provide another picture of individuals’ employment outcomes after the transition away from 14(c) employment. Of the 1,875 individuals Oregon was tracking in September 2015: · about 60 percent (or 1,100 people) had participated in VR by April 2024. · of these, about 500 people had successfully closed cases (i.e., they found employment for at least 90 days). The VR system tracks people intermittently after their cases are closed, and some people may choose not to return to Medicaid services after successfully completing VR services. According to our analysis, 70

percent of the people who found competitive integrated employment through VR

did not return to Medicaid for supported employment services. Source: GAO analysis of Oregon VR data. | GAO‑25‑106471 |

For the individuals in our analysis, a decline in the use of Medicaid-funded employment services coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and state-mandated increases in the minimum wage for people working in 14(c) employment.[33] As figure 5 shows, by September 2020, participation in 14(c) employment had fallen to near zero. At the same time, the share of individuals using employment services for CIE or group employment decreased.[34] Oregon state officials said that the pandemic generally had a significant impact across different services. However, our analysis could not isolate the ultimate cause of the declines we observed.[35] The use of employment services for CIE subsequently rebounded and grew slightly, but group employment levels did not recover to pre-pandemic levels during the period we analyzed.

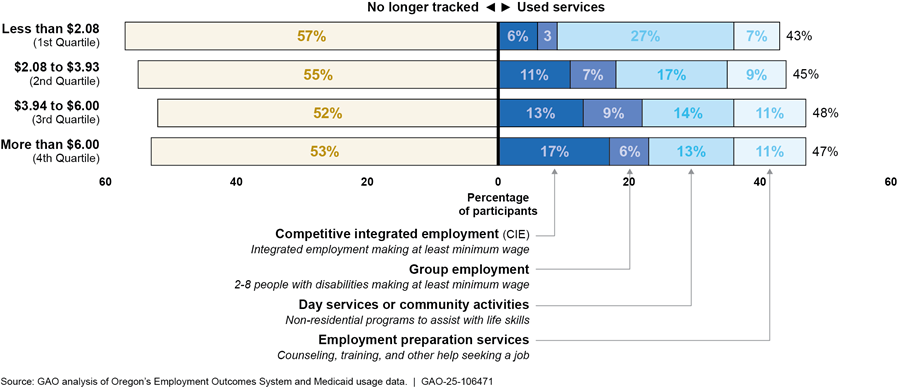

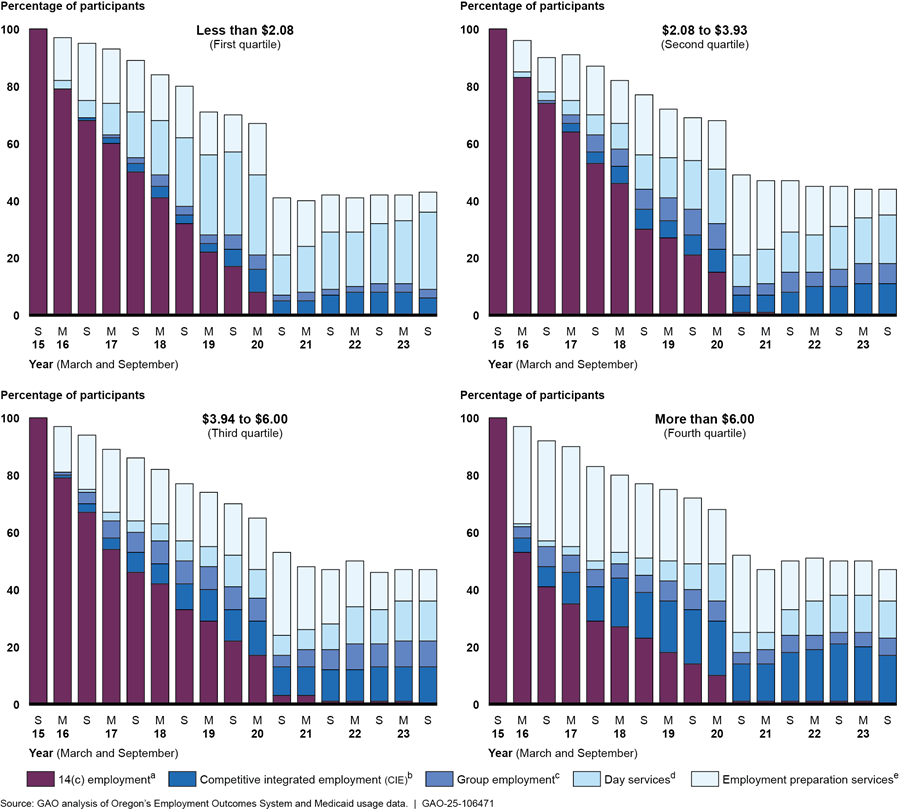

We conducted additional analyses using individuals’ baseline hourly wages in 14(c) employment and found that those with the highest 14(c) wages were the most likely to move to CIE after the transition away from 14(c) employment. Specifically, 23 percent of those with the highest hourly wages in September 2015 were receiving employment support services for CIE or group employment in September 2023, compared with 9 percent for those with the lowest baseline hourly wages (see fig. 6).[36] Individuals who earned the lowest hourly wages in September 2015 were more likely to participate in day services in September 2023 than those who earned the highest hourly wages. We previously reported that wages for people working in 14(c) employment may reflect differences between workers as well as employment opportunities, and that these factors can influence their movement into CIE.[37]

Figure 6: Outcomes for Oregonians with I/DD Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment by Baseline Hourly Wage Level, September 2023

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. This figure includes 1,875 individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) who were receiving Medicaid supported employment services in September 2015 and working for less than the Oregon minimum wage in 14(c) employment. We grouped individuals into quartiles based on their hourly wages in 14(c) employment in September 2015 (i.e., lowest 25 percent, 26-50 percent, 51-75 percent, 76-100 percent). Individuals may have received more than one Medicaid service in any given month. To avoid double-counting, the figure shows each individual once per month in which they received any of the designated Medicaid services, in the following priority order: (1) supported employment for CIE, (2) supported employment for group employment, (3) employment preparation, or (4) day services or community activities. For example, a person receiving supported employment services for working in group employment may have also received day services, but this figure reflects their employment. Numbers may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. See appendix I for more information on our data analysis, including additional analysis by September 2015 baseline 14(c) wage.

What were workers’ wages and hours after transitioning out of 14(c) employment in selected states?

Colorado

Among those in Colorado who left 14(c) employment for another type of employment, average hourly wages increased compared to the overall average under 14(c) employment, which includes individuals regardless of their later employment status. In addition, average hours worked per week varied depending on the type of employment they moved to (see table 1).[38]

Table 1: Average Wages and Hours Worked for Coloradans Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment, June 2021-June 2023

|

|

Average hourly wages |

Average hours per week |

|

Baseline: June 2021 14(c) data 195 people |

$4.33 |

13.0 |

|

Transitioned to competitive integrated employment 47 people |

$12.92 |

10.4 |

|

Transitioned to group employmenta 49 people |

$12.56 |

14.7 |

|

Transitioned to employment (overall) |

$12.74 |

12.5 |

Source: GAO analysis of Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy & Financing 2021 Data Report and Colorado’s 14(c) tracking data. | GAO‑25‑106471

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. The information on hours and wages were reported by former 14(c) employers at various points between July 2021 and June 2023. In February 2024, state officials verified each employer’s average wage and hour information. We did not adjust wages for inflation. From July 2021 to June 2023, prices on average increased 12 percent.

aOne former 14(c) employer reported that five individuals who worked in 14(c) employment transitioned to group employment but did not report wages or hours for them. As a result, our calculations for group employment and overall employment reflect 44 of the 49 people who transitioned into group employment.

Oregon

In Oregon, average hourly wages in September 2023 increased compared to the overall average under 14(c) employment in September 2015, which includes individuals regardless of their later employment status. At the same time, average hours worked per week generally decreased for the individuals the state was tracking between September 2015 and September 2023 (see table 2).[39]

Table 2: Average Wages and Hours Worked for Oregonians with I/DD Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment, September 2015-September 2023

|

|

September 2015 (14(c) baseline) |

September 2019 |

September 2023 |

|||

|

|

Average hourly wages |

Average hours per week |

Average hourly wages |

Average hours per week |

Average hourly wages |

Average hours per week |

|

14(c) employment |

$4.01 |

16.0 |

$5.70 |

14.6 |

- |

- |

|

Competitive integrated employment |

|

|

$11.85 |

12.3 |

$14.14 |

10.8 |

|

Group employment |

|

|

$11.73 |

8.5 |

$13.56 |

10.8 |

|

Post-14(c) employment (overall) |

|

|

$11.79 |

10.5 |

$13.93 |

10.8 |

Source: GAO analysis of Oregon’s Employment Outcomes System data. | GAO‑25‑106471.

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. This table includes data for individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) who were receiving Medicaid supported employment services in September 2015 and working for less than the Oregon minimum wage in 14(c) employment. Average wages and hours are based on those who received employment services in the month shown. The 2015 data includes all 1,875 individuals, but fewer people were working in September 2019 (685) and September 2023 (339). We did not adjust wages for inflation. From September 2015 to September 2023, prices on average increased 29 percent.

Why were selected states unable to track outcomes for certain people who used to work in 14(c) employment?

Colorado and Oregon officials primarily track employment and other outcomes for people who used to work in 14(c) employment based on their use of services funded by Medicaid, such as supported employment or day services, so they are not able to easily track outcomes for people who stop receiving those services. State officials and stakeholders identified several possible reasons that people may no longer receive these Medicaid services from the state, including that:

· they are no longer eligible for services (e.g., they have passed away or moved out of state);

· they retired from employment and chose not to participate in day services or similar community activities; or

· they are continuing in CIE with natural supports—personal associations and relationships developed in the community and at work—rather than Medicaid-funded supports.

We analyzed available state Medicaid data from Colorado and Oregon to better understand the extent to which outcomes for some former 14(c) workers are no longer tracked and, to the extent possible, why.

Colorado

As of the most recent data available in February 2024, Colorado officials were not able to use the state’s Medicaid data to track employment outcomes for almost 20 percent of those who worked in 14(c) employment in July 2021.[40] Of those individuals, the state’s data indicated that nearly half were no longer eligible for Medicaid services in Colorado.[41] We were not able to determine why the remaining individuals were not using Medicaid employment or day services in February 2024.

State Medicaid officials told us that other state data systems could provide more information on individuals’ employment outcomes and activities, but that they face challenges sharing data across agencies. For example, people with disabilities who are not receiving Medicaid employment or day services may be instead receiving VR services to obtain a CIE job.[42] Officials told us that they faced challenges trying to share data with other agencies, including VR, which could make it difficult to identify anyone who may be working in CIE without Medicaid supports after completing VR services.

Oregon

As of September 2023, Oregon officials were not able to use Medicaid data to track employment outcomes for 1,013 former 14(c) workers, or 54 percent of the individuals they began tracking in September 2015. Of those, a quarter were no longer eligible for Medicaid services, according to the state’s data.

Oregon officials and stakeholders identified some additional reasons why they may no longer be able to track outcomes. Specifically, some former 14(c) workers may have decided to retire or may be continuing to work in CIE with natural supports. Using additional data the state provided, we estimated how many individuals may fall into these categories.

· About 17 percent of individuals whose outcomes were no longer being tracked in the Medicaid data were at least 62 years old when they exited the data and, therefore, possibly retired.[43]

· Although we did not identify any data in Oregon to indicate whether an individual is continuing to work with natural supports, state officials said that Medicaid data offers potential insights. Specifically, officials told us that people who completed the full 2 years of Medicaid’s CIE job coaching were likely continuing to work in their CIE positions with natural supports.[44] Our analysis found that this could explain up to 7 percent of the people who no longer appear in the data (see fig. 7).[45]

Note: 14(c) employment involves paying individuals with disabilities less than the federal minimum wage. This figure includes 1,875 individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) who were receiving Medicaid supported employment services in September 2015 and working for less than the Oregon minimum wage in 14(c) employment. See appendix I for more information on our data analysis, including how we identified individuals who may have retired or were likely continuing to work in competitive integrated employment (CIE) after completing job coaching.

Finally, individuals who do not appear in the Medicaid data could have instead received services from VR. According to officials, individuals generally receive employment preparation services through Medicaid and use VR services for supports to find a job in CIE. Individuals who obtain CIE jobs through VR may choose not to return for CIE job coaching provided through Medicaid. According to our analysis, 70 percent of the approximately 500 people who found CIE jobs through VR did not return for supported employment services provided through Medicaid between September 2015 and September 2023.

Perspectives of Individuals Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment and Their Caregivers

What did individuals and their caregivers in selected states say about the individuals’ prior experience in 14(c) employment?

Individuals and their caregivers we interviewed talked about both positive and challenging experiences with 14(c) employment. However, more individuals discussed positive experiences than challenging experiences.[46] They most frequently mentioned liking the tasks they completed, the interpersonal relationships they had with coworkers and staff, and earning a wage.[47] Other things individuals said they liked included the skill growth opportunities available and the sense of contribution they felt while working. However, they also reported challenges related to the tasks they completed, interpersonal relationships, and issues related to employment services they accessed.

Tasks and responsibilities. Individuals who previously worked in 14(c) employment talked about liking the duties they completed, such as vacuuming or cleaning bathrooms. Similarly, caregivers also reported that the individual liked the tasks they completed because they aligned with the individual’s interests. For example, one person’s parents told us their son vacuumed as a part of his janitorial duties, which they said was his favorite hobby. His mother also said that his former 14(c) employer “[was] really good about letting him do what he liked to do.” However, we also heard from another individual who described her janitorial duties as “dirty work.” In addition, other individuals said they did not like the physical aspects of their 14(c) job, such as standing for long periods of time, or shared concerns about the safety of the tasks they completed. Finally, other caregivers said that some of the tasks the individuals completed at their 14(c) jobs did not align with their skill levels or interests.

|

Examples

of Tasks and Responsibilities Performed by PeopleWho Worked in

A worker assembles cardboard inserts. Source: GAO file photo. | GAO‑25‑107024 Note: This employer was not located in our selected states. |

Interpersonal relationships. Individuals and their caregivers who reported having positive experiences with interpersonal relationships at their 14(c) jobs said that they liked seeing people they knew, such as their peers or supervisors. One caregiver said her son “made lifelong friends” at his 14(c) job. In contrast, individuals also discussed issues they had working with others who were not nice to them or who they thought created an uncomfortable environment.

Earning a wage. Individuals also cited positive experiences related to their wages. For instance, they said they liked earning a wage and being able to save money to spend on things they liked. One person talked about using the money he saved to buy new shoes.

Employment services. Individuals also cited challenges related to a lack of training available to them and a dissatisfaction with the quality of employment services they received. For instance, one person said, “The [job coaches] would make promises, [but] they never really helped me with anything. They never kept track of anything. They wanted me to do this and that, and they wanted me to do stuff that I didn’t want to do.”

|

In Their Words: Perspectives on Prior 14(c) Employment “I liked working with my hands in woodwork.” – Individual who previously worked in 14(c) employment “A lot of the stuff that he was doing at the beginning [when he was working in 14(c) employment] would help strengthen his hands because he has weakness on the left side. [The things he did] would help him with the mobility of [his hands].” – Caregiver “That type of sheltered workplace…I don’t think it was really the right fit for me overall, just because of my aptitudes of getting higher up. And also, having to travel back and forth and then getting paid less than minimum wage wasn’t really worth my time.” – Individual who previously worked in 14(c) employment “I think he tried a couple of sheltered workshop kind of things, and they weren’t very meaningful because he was more capable than what they were doing.” – Caregiver |

Source: GAO interviews with individuals who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers. | GAO‑25‑106471

Note: We selected these comments because they provide

real-life examples of the common themes identified through our content analysis

of the interviews we conducted. In some cases, we edited responses for clarity

or readability.

What did individuals and their caregivers in selected states say about the transition out of 14(c) employment?

|

Other Opportunities for Social Connection Outside of work and day services, individuals and their caregivers talked about participating in activities, such as camp, church, or community-based committees or organizations, as well as caregiver-organized outings and events. For instance, three people talked about being involved in various types of advocacy work. Another person said he played basketball for his state’s Special Olympics team and went to the Special Olympics USA Games. People also talked about romantic relationships, relationships with neighbors, and relationships they had in their communities. Source: GAO interviews with individuals who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers. | GAO‑25‑106471. |

Individuals and their caregivers we interviewed discussed various opportunities and challenges they experienced during the transition out of 14(c) employment, such as how the individuals’ social connections had been affected since transitioning out of their 14(c) jobs or their experiences finding CIE jobs.

Social connections. Individuals and their caregivers talked about making new social connections or maintaining old connections. For instance, everyone we interviewed who transitioned to CIE talked about the social connections they made with people at work.[48] They talked about how various work functions, such as holiday parties and gift exchanges, helped them build social connections. Individuals also talked about connecting with coworkers outside of work by going out to eat or to the movies or playing video games. Some people also said they maintained relationships with their former 14(c) coworkers through their day service programs and providers, or through their CIE job.

On the other hand, we also heard from caregivers and one individual who said the individual’s social circle had shrunk since transitioning out of 14(c) employment. For instance, they talked about how the individuals’ former coworkers were no longer attending the same day service provider. Generally, those who had this perspective were caregivers of individuals who were not employed but were attending day services. In addition, other individuals said they were not inclined to stay in contact with their former 14(c) coworkers.

Day services. Individuals who accessed day services after transitioning out of 14(c) employment talked about positive experiences they had, such as the classes and activities available, the outings they participated in, and the interpersonal relationships they had with staff and others who accessed day services. People said they enjoyed classes such as science, art, and cooking. They also talked about individualized and group outings their day service providers coordinated, including attending sports games or movies, going to museums or animal shelters, and trips to explore cities nearby. Day service providers also coordinated larger events such as dances, fundraisers, plays, and holiday parties. Finally, people talked about how they got along with everybody at their day services, or said they liked being able to see people they knew regularly at day services. One person told us, “I’m [re-writing] a book for [my friend] because sometimes the words are too small, and he likes to [read]. So [now,] he can read it better without giving himself a headache.”

|

Example of Activities Coordinated by Day Service Providers

A day service provider decorated for a Spring Dance. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107024 Note: This provider was not located in our selected states. |

At the same time, individuals and caregivers also discussed challenges related to accessing day services after transitioning out of 14(c) employment. For instance, one individual said she was on a waiting list to increase the number of days she could attend her day services program. Two caregivers, whose sons attended the same day services facility, discussed how their sons’ skill development had been affected since the service provider transitioned from 14(c) employment to day services. For instance, one of these caregivers said she had observed small regressions in her son’s skills—such as misspelling his name—since his day service provider limited the number of days he was able to access day services. She said, “I think [his skills regressed] because there wasn’t an everyday progression of doing stuff…They used to do t-shirts and stuff like that, and I don’t think they do that anymore.” These caregivers said that the day service facility their sons attended had been affected by decreases in funding and staffing levels.

Finding CIE opportunities. Individuals who transitioned to CIE told us about how they obtained their job, including through support from job coaches or their own research. For others, their former 14(c) employer converted to provide CIE. People who transitioned to CIE talked about opportunities they experienced since obtaining their job, including chances to work in various departments, potential new employment opportunities, or pathways for taking on additional responsibilities at work, such as receiving a promotion. For instance, one person said he recently took over managing inventory for two products at his job.

At the same time, individuals who transitioned to CIE and those who had not transitioned to CIE talked about challenges related to finding CIE opportunities. Specifically, individuals and their caregivers said it was challenging to find CIE opportunities that matched the individual’s interests or addressed the individual’s or caregiver’s needs. For instance, one person said, “It took me a while [to find a job]. I had to look and look and look because I didn’t want [to work in] any grocery stores. I wanted [to work in] restaurants.” Caregivers also discussed logistical needs and safety concerns. For example, they talked about challenges finding jobs nearby and finding accessible public transportation to get to work.

Further, with respect to challenges finding CIE opportunities, individuals and their caregivers commented that people with disabilities have a wide range of interests and needs, and there should be more support for various types of employment, not just CIE. For instance, one parent of an individual said, “One of the biggest concerns we have about the changes [is that they] don’t really cover everybody, they only cover a small population. No whole population of [people with intellectual or developmental disabilities] is going to function at the same level.” The other parent added, “There needs to be options. And they need to have a say in it.”

|

In Their Words: Experiences During or After the Transition Out of 14(c) Employment “[I like] just being around my peers and my [day service] staff and my [former 14(c) and CIE] work peers here at the day program.” – Individual who previously worked in 14(c) employment “Wednesday night is [social night]. One of the providers picks up [a few] people and takes them to [a nearby city] for activities.” – Caregiver “Not everyone is the same. And when they made this blanket change, they made the change for everyone, and maybe they could have done it in phases or something. I don’t know. I feel like they could have approached it a little different because there’s always this thing where they just kind of group people with disabilities together. But somebody with autism is not going to have the same needs as somebody with Down syndrome. And then even two people with autism aren’t going to have the same needs. [When I was in 14(c) employment, I had co-workers] that were autistic, non-verbal, but they can read, they can write. They could do their job. They just needed a different form of communication. And I feel like those are [some] of the people that kind of got hurt the most by [the transition away from 14(c) employment].” – Individual who previously worked in 14(c) employment “The [14(c) job] [was] more of a controlled environment that they were going to. There was an understanding of those who were working there that the staff were able to work with [the employees] more. The [staff] were trained on how to deal with things that might come up, but in [CIE] they’re well-meaning, but they don’t always get it.” – Caregiver |

Source: GAO interviews with individuals who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers. | GAO‑25‑106471

Note: We selected these comments because they provide real-life examples of the common themes identified through our content analysis of the interviews we conducted. In some cases, we edited responses for clarity or readability.

Employment support services. While some individuals had positive experiences accessing employment support services, others talked about issues accessing these services when they transitioned out of 14(c) employment. For instance, one person talked about challenges he experienced working with the local VR office. He said, “It would have been nice if VR was more up to speed…They were like in a holding pattern. Well, the longer it takes, [then] the opportunity may not be there.” He chose to pursue employment without the help of VR services. He applied directly to the employer and was hired.

What did individuals and their caregivers in selected states say about their experiences with CIE?

|

Example of a Competitive Integrated Employment (CIE) Workplace

An electronic recycling and document shredding facility. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107024 |

Individuals we interviewed who transitioned to CIE from 14(c) employment talked about both positive and challenging experiences they had with CIE. However, more individuals shared positive experiences with their CIE job than challenging experiences.[49] Similar to what they said about their 14(c) jobs, people in CIE said they liked the interpersonal relationships they had at work, the tasks they completed, the skill growth opportunities available, and earning a wage. Aside from common themes addressed below, individuals also said they liked the sense of contribution they felt from doing their job, the ability to work independently, and the discounts they received on products sold at their workplaces. At the same time, those who discussed challenges reported issues related to interpersonal relationships, the tasks they completed, and the employment services available.

Interpersonal relationships. As previously discussed, individuals said they liked the interpersonal relationships they had at work, including with colleagues and customers. For instance, one person said, “I love the people. I like coming in, seeing their faces, talking to them, [and] helping them out.” Conversely, individuals and their caregivers also said it could, at times, be challenging to work with others. One person said it was difficult to work with new people until she learned their communication styles.

Tasks and responsibilities. Individuals also discussed the specific tasks they liked, such as cleaning and putting boxes together for baked goods. One person said she liked “working [in the] pet and toy [departments]” of the store. Another individual told us that she liked all the tasks she completed in her CIE position, including setting tables. On the other hand, other people said they did not like tasks such as cleaning bathrooms or stocking shelves.

Skill growth opportunities. Individuals discussed liking the skill growth opportunities available at their CIE job, such as working on their social skills. One person told us he liked having opportunities to overcome challenges at work. He said one of the challenges he worked to overcome was interpersonal conflicts with coworkers. He told us what helped him was learning to stay patient and “[to try to] get to know that they have struggles as well, and also try to help them as best as you can.”

Earning a wage. Other individuals talked about how they liked being paid for the hours they worked rather than at a piece rate, and one person talked about the financial autonomy she experienced.[50] She said, “I can pay my own bills instead of [my sister]. It’s my own time and [I] got my own house.” Caregivers also discussed the individual’s financial autonomy, including being able to purchase their own groceries and travel.

Employment services. Individuals talked about challenging experiences they had with employment services, such as the quality of the match between the individual and their job coach. For instance, one individual and her sister, who was her caregiver, talked about how the individual has had multiple job coaches because there was not always a good personality match between her and her job coach. A case manager for another individual said, “Sometimes, the job coaches that they hire aren’t really as effective at helping the people. So that’s frustrating to [her]. One, she feels like [her co-worker] is not getting the help they need. But also, it’s frustrating when that person doesn’t know what to do.”

|

In Their Words: Experiences with Competitive Integrated Employment (CIE) “My job is great, [it] makes me feel fantastic.” – Individual who previously worked in 14(c) employment “They treat them very well there and he has a lot of good friendships and stuff like that.” – Caregiver “Every once in a while, [someone else’s] job coach would boss me around. And no, it’s not how it works. I just ignore it.” – Individual who previously worked in 14(c) employment “I think you had—just like any other job—you have testy people to put up with.” – Caregiver |

Source: GAO interviews with individuals who previously worked in 14(c) employment and their caregivers. | GAO-25-106471

Note: We selected these comments because they provide real-life examples of the common themes identified through our content analysis of the interviews we conducted. In some cases, we edited responses for clarity or readability.

What did individuals who worked in CIE and their caregivers in selected states say about impacts to the individuals’ federal means-tested benefits?

Individuals and their caregivers we interviewed said they were aware of how their federal means-tested benefits could possibly be impacted by their work in CIE. Most individuals and their caregivers mentioned fears or concerns about how increases to the individual’s income or assets could affect benefits they received, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medicaid.[51] In particular, fears or concerns about potential impacts to the individual’s SSI benefits were common.

Income limits. Individuals and their caregivers told us that their fears or concerns about the potential impacts to the individual’s benefits factored into decisions they made about employment. For instance, in one interview, an individual and his parents discussed concerns about how small or temporary increases in wages could decrease his monthly SSI benefits. The Social Security Administration calculates a person’s benefits each month using a formula in which benefits are generally reduced by $1 for every $2 of earned income (which excludes the first $65 earned each month) until benefits reach zero.[52] As a result of these concerns, this individual and his parents were hesitant about taking on additional shifts, such as when a co-worker called in sick. Another person talked about how increasing the number of days she worked had decreased her monthly SSI benefits, which affected her ability to pay for housing because she used her monthly benefits to help make her rent payments.

Among those who shared concerns about potential impacts to Medicaid, concerns included losing access to services supported by an individual’s Medicaid benefits or being deemed ineligible for Medicaid benefits completely.[53] However, in each case, the individual or the caregiver told us they were able to access another program through Medicaid to receive support or had access to another health care plan. One of these people said she lost her SSI when she was hired as a full-time employee, but she retained her Medicaid coverage.[54]

Asset limits. Individuals and their caregivers also talked about how the asset limits for SSI benefits factored into decisions they made, including employment decisions. For instance, we heard from individuals and caregivers who said the individual has, at times, needed to spend money they had saved because their SSI could be impacted if their savings surpassed the maximum threshold for assets, which is $2,000 for individuals.[55] Each individual who said their federal benefits had not been impacted by their transition to CIE had an Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) account, which is a tax-advantaged savings account for people with disabilities that often does not count toward SSI’s asset limit.[56] In contrast, among those who considered the potential impacts to their benefits when making employment decisions, individuals and caregivers frequently did not know about ABLE accounts.[57] We also heard from one person with an ABLE account who was still concerned about how increases to his income or assets could impact his benefits. Finally, individuals and their caregivers said the individual would consider taking on additional hours if their benefits would not be impacted.[58]

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Education, Labor, and Health and Human Services for review and comment. We also provided relevant portions of the draft report to cognizant officials within the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing and the Oregon Department of Human Services. The Departments of Education and Labor and Colorado and Oregon state officials provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. The Department of Health and Human Services did not provide comments on the report.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at EWISInquiry@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Elizabeth H. Curda

Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security

This report examines: (1) which states have enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates and are collecting data on employment outcomes for people who worked in the program, (2) employment outcomes in selected states for people who worked in the program, and (3) the views of people and their caregivers in selected states about their transition out of 14(c) employment, including opportunities and challenges.

Identifying States That Have Enacted Legislation Eliminating 14(c)

For our first objective, we obtained information on which states had enacted legislation to eliminate the use of 14(c) certificates as of January 2025.[59] To identify states, we relied on information from Department of Labor (DOL) officials; four experts on the employment of people with disabilities and related state data; four key stakeholder organizations; and publicly available sources such as state websites and information from the Association of People Supporting Employment First and the Council of State Governments. We selected experts based on their academic research, policy expertise, and knowledge of state legislation and data collection. Experts included researchers who have published on the use of 14(c) certificates and/or transition out of 14(c) employment and stakeholders included representatives of organizations that work with 14(c) workers and employers.[60] We excluded states that have taken indirect steps to reduce the use of 14(c) certificates, such as no longer allowing Medicaid funding to be used for services provided through 14(c) employment, but have not enacted legislation.

We sent questionnaires to cognizant officials in 16 states asking them to confirm or correct information we gathered, such as whether they are collecting data on employment outcomes. We pretested our questionnaire by meeting with three states to solicit feedback about whether the questions were clear and concise. We received responses from all states we queried. See appendix II for a summary of this information.

State Selection

We also used information from our first objective to select states to serve as illustrative examples for our other two objectives. Our criteria for state selection included:

· availability of reliable, relevant individual-level data on employment outcomes for affected individuals, ideally covering before, during, and after the transition away from 14(c) employment;

· ongoing transition or recent completion so that (a) individuals who transitioned out of 14(c) employment were more likely to recall their experiences, and (b) state officials involved in the transition were more likely to still be in their positions;

· a significant number of individuals working under 14(c) certificates at the time of transition (which we defined as a minimum of 150 individuals); and

· variation in geography and state minimum wage rates (obtained from DOL’s website), where possible.

To help identify states that had eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates and met these criteria, we sent written requests for information and conducted interviews, when possible, with six states to make our final decisions. We initially selected three states that met our criteria: Colorado, Maryland, and Oregon. These states had multiple years of relevant data on outcomes and had eliminated the use of 14(c) certificates recently enough that individuals who formerly worked in the program and their caregivers would be more likely to easily recount their experiences with the transition out of 14(c) employment. However, Maryland officials declined to participate in in-depth interviews or share data at an individual level, citing staff capacity issues at the state’s Developmental Disabilities Administration. We were unable to select a suitable replacement as the remaining states did not meet our criteria. For example, some states had not yet started collecting data or had few workers left in 14(c) employment at the time the state enacted its legislation, according to state officials.

Analysis of State Data

To understand employment outcomes for individuals who used to work in 14(c) employment, we obtained and analyzed data provided at the individual level by the two states that met our criteria and agreed to participate in our study (Colorado and Oregon). These data generally covered the time periods during which each state was eliminating the use of 14(c) certificates. To add context to our findings and better understand the landscape of each selected state, we interviewed relevant state agency officials, such as those from developmental disability agencies, and other stakeholders involved in efforts to transition away from 14(c) employment. We selected these five stakeholders—self-advocates, provider organizations, and a parent advocacy group—based on discussions with state officials, national organizations, and experts on disability employment.[61] In addition, with respect to our analysis of wages, we measured inflation over our study periods using national Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers data.

Colorado Data

We analyzed two types of data obtained from state officials to understand employment and other outcomes for individuals who formerly worked in 14(c) employment in Colorado. These data included information about those individuals’ initial placements after leaving 14(c) employment and, for most, their longer-term use of Medicaid-funded supported employment and day services.

First, we obtained individual- and summary-level tracking data submitted by the nine employers that held 14(c) certificates immediately before the state’s legislation eliminating the use of 14(c) certificates went into effect on July 1, 2021. The data covered 195 individuals and included information such as the date when they left 14(c) employment, the type of employment [competitive integrated employment (CIE), or group employment] or other service they participated in immediately after 14(c) employment, and, for those who obtained CIE or group employment, the number of hours worked weekly and their hourly wage.[62] The individual-level data were collected between July 2021 and June 2023. State officials told us that in February 2024, they verified summary-level information with each of the nine employers, making corrections or updates as needed.

Second, we obtained available, anonymized monthly Medicaid utilization data for a large subset of the 195 individuals in the tracking data, covering January 2021 through February 2024, which allowed us to look at trends in overall service usage over time.[63] For analysis of outcomes, we generally relied on data from July 2021 through June 2023 to align with the tracking data discussed above. To avoid double-counting individuals receiving more than one service, we assigned each person to a single activity using the following order of Medicaid services:

1. supported employment for CIE,

2. supported employment for group employment,

3. employment preparation services (services that help people obtain employment, including counseling or training, or services that teach general concepts for being successful at work),

4. day services or community-based activities (non-residential programs to assist with self-help, socialization, and adaptive skills), and

5. outcome not tracked, which applies to any individuals for whom there is no record of any services provided in the designated month.

This ordering ensured that we captured any CIE or group employment supported by Medicaid services, to provide insight into how many people continued to work after leaving 14(c) employment. For any individuals who were receiving more than one service in a given month, we classified them by the service that comes highest in the above list. For example, a person who was receiving supported employment services for CIE and was also in day services would be classified as in CIE. Similarly, a person who was in employment preparation services and day services would be classified as receiving employment preparation services. For our analysis of individuals whose outcomes were not tracked, we used data from February 2024 (the most recent data available to us).

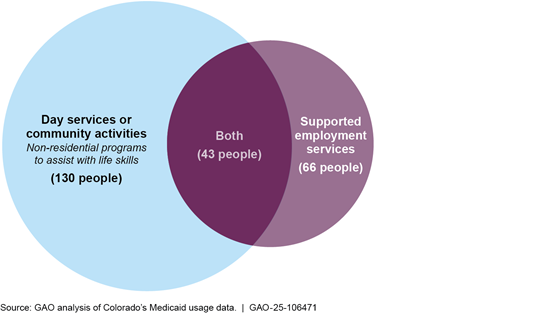

Because day services are an important part of Medicaid-funded support services for most individuals who worked in 14(c) employment, we conducted analyses to identify how many individuals used day services overall.[64] In February 2024, nearly 70 percent of the 195 individuals Colorado began tracking in July 2021 were using day services, including one-third who were also receiving supported employment services for CIE or group employment (see fig. 8 below).

Figure 8: Overall Use of Medicaid Funded Day Services and Employment Supports among Coloradans Who Used to Work in 14(c) Employment, February 2024

Note: Supported employment services refer to Medicaid services such as coaching for those in competitive integrated employment or group employment.

Colorado Data Reliability

For both data sets described above, we assessed the reliability of selected variables by conducting electronic data tests for completeness and accuracy, reviewing documentation, and interviewing knowledgeable officials about how the data were collected and maintained and their appropriate uses. Through this process, we identified some limitations of the data and, where needed, applied measures to mitigate the effect of the limitations (see below).

For Colorado’s 14(c) employment tracking data, we identified the following limitations:

· The data represent where each person went as of the date they left 14(c) employment, which generally occurred between July 2021 and June 2023. State officials said they did not require employers to continue to track workers after these placements. As a result, the data do not provide information on any subsequent changes in employment, wages, or other outcomes.

· The data capture one outcome for each individual, with a priority on employment. As a result, the data capture the employment each individual engaged in and, if not employed, the non-employment services or activities individuals received. For example, a person working in group employment may also have received day services, but the data reflects their employment.

· Individual wages and hours were not included for all those who moved from 14(c) employment to other employment. In particular, the data included individual-level wages and hours for less than half of people in group employment. As a result, we determined that those data were not sufficiently reliable for us to analyze. Instead, we relied on summary-level data confirmed for each employer by the state for our analysis. We used the employer-level summary data to calculate weighted averages of hours worked and hourly wages by type of post-14(c) employment.[65]

For Colorado’s Medicaid utilization data, we identified the following limitations:

· Due to Colorado’s definitions for individual and group supported employment services (specifically, job coaching) during the time period of our analysis, it is not possible to cleanly split the individual and group services into CIE and group employment. State officials explained that they report individual job coaching as CIE, but that there are people working in a group setting who were receiving individual job coaching for line-of-sight supervision, a one-to-one service. Conversely, there may be some people receiving group job coaching who are in CIE. Because there is no way identify those individuals, we followed Colorado’s approach and reported individual coaching as CIE and group coaching as group employment.

· Medicaid utilization data were not available for a small percentage (less than 5 percent) of the 195 individuals included in the 14(c) tracking data discussed above. Specifically, they were not tracked because they were (1) not receiving supported employment services under their type of Medicaid waiver, or (2) receiving services through a state-funded program that is not tracked in the Medicaid data system, according to state officials.

Despite these limitations and in conjunction with the steps we took to address the limitations listed above, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of analyzing available data on employment outcomes for individuals who used to work in 14(c) employment in Colorado.

Oregon Data

We analyzed three types of anonymized data obtained from state officials to understand employment and other outcomes for individuals who used to work in 14(c) employment in Oregon. This included data from Employment Outcome System (EOS), as well as Medicaid service and Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) case data. These data generally covered September 2015 through September 2023, including the use of Medicaid services for supported employment and day services, as well as use of VR services to seek and obtain CIE.