CURRENCY TRANSACTION REPORTS

Improvements Could Reduce Filer Burden While Still Providing Useful Information to Law Enforcement

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

CURRENCY TRANSACTION REPORTS

Improvements Could Reduce Filer Burden While Still Providing Useful Information to Law Enforcement

Highlights of GAO-25-106500, a report to congressional committees

View GAO-25-106500. For more information, contact Michael Clements at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov

Why GAO Did This Study

Financial institutions filed roughly 167 million CTRs in fiscal years 2014– 2023. The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 includes a provision for GAO to review CTR requirements and issue a report by December 2025. GAO has issued four prior reports in response to the act, including one on law enforcement’s use of reports about suspicious financial transactions.

This report examines (1) the potential effects of changing the CTR threshold, (2) the extent that CTR requirements align with statutory objectives, and (3) the extent that CTR requirements provide useful information to law enforcement.

GAO analyzed data from FinCEN on CTRs filed in fiscal years 2014–2023 and conducted a survey of all 327 federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies that can directly access CTRs (60 percent response rate). GAO also interviewed officials of tribal, federal, state, and local agencies; industry groups representing CTR filers; and 13 financial institutions (selected to represent different asset sizes and types of institutions), as well as privacy and compliance experts. GAO also reviewed relevant laws and regulations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations, including that FinCEN take steps to reduce the number of unused CTRs, eliminate infrequently used fields, and simplify and clarify aggregation requirements. FinCEN agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

Currency transaction reports (CTR) must be filed by financial institutions for cash transactions exceeding $10,000 in a day and are intended to provide law enforcement with highly useful information. The $10,000 threshold, set in regulation by the Department of the Treasury in 1972, has not been adjusted for inflation. Inflation may have contributed to the increase in volume of CTRs filed, which has increased by about 62 percent since fiscal year 2002 (see figure). The inflation-adjusted threshold in 2023 would have been about $72,880. Using an inflation-adjusted threshold would have reduced the number of CTRs filed by at least 90 percent annually since 2014.

D

GAO identified key challenges and potential inefficiencies in the CTR system:

· Unused reports. Law enforcement agencies accessed a small percentage of CTRs through either the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) BSA Portal or agencies’ internal systems, leaving most unused. From 2014 through 2023, law enforcement agencies accessed about 5.4 percent of CTRs filed in FinCEN’s BSA Portal during that period. For CTRs accessed in either FinCEN’s BSA Portal or agencies’ internal systems in 2023 (the most recent full year), law enforcement agencies accessed less than 3 percent of CTRs filed from 2014 through 2023.

· Difficult and infrequently used fields. Filers GAO interviewed reported difficulty completing certain fields, some of which law enforcement agencies reported infrequently using.

· Unclear or unhelpful aggregation requirements. FinCEN’s requirements for aggregating related transactions exceeding $10,000 in 1 day was sometimes unclear to filers GAO interviewed. Further, some law enforcement agencies noted that large aggregated CTRs of unrelated parties do not provide useful information.

By taking steps to reduce the number of unused CTRs—such as through adjusting the reporting threshold—and by eliminating rarely used fields and clarifying aggregation requirements, FinCEN could reduce unnecessary filer burden without affecting CTRs’ usefulness to law enforcement.

Abbreviations

|

AMLA |

Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 |

|

BSA |

Bank Secrecy Act |

|

CTR |

currency transaction report |

|

CFTC |

Commodity Futures Trading Commission |

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

DEA |

Drug Enforcement Administration |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

FinCEN |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

IRS-CI |

Internal Revenue Service Criminal Investigation |

|

NAICS |

North American Industry Classification System |

|

OCDETF |

Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces |

|

SAR |

suspicious activity report |

|

SEC |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 11, 2024

The Honorable Sherrod Brown

Chairman

The Honorable Tim Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Patrick McHenry

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

To safeguard national security and combat money laundering, terrorism financing, and other financial crimes, federal law requires financial institutions to provide information on individuals that engage in large cash transactions.[1] Specifically, the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requires that financial institutions such as banks, casinos, and money services businesses file currency transaction reports (CTR) on cash transactions that exceed $10,000 in a single day.[2] CTRs contain information on the person conducting the transaction, such as name, address, and taxpayer identification number, as well as information about the transactions involved in the filing. The Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)—which administers the BSA—collects and maintains CTR information. Authorized law enforcement and other agencies can use CTRs when investigating and prosecuting illicit finance activities.[3]

In a 2020 report, we found that many law enforcement agencies regard CTRs as an important source of information.[4] However, some Members of Congress and financial industry representatives have raised questions about the usefulness and level of burden associated with CTRs. For example, they note the $10,000 CTR threshold has not been adjusted for inflation since Treasury introduced it in 1972.

The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA) includes provisions for Treasury to review CTR requirements for potential streamlining and to evaluate potential adjustments to the CTR threshold.[5] AMLA also includes a provision for GAO to review the effectiveness and importance of CTRs to law enforcement and the effects of raising the CTR threshold.[6] The provision called for GAO to issue a report by December 2025. This report examines (1) how CTR requirements have changed since they were established, and the extent to which these requirements align with statutory objectives; (2) the extent to which CTRs provide useful information to law enforcement; and (3) the potential effects of changing the CTR threshold.

The scope of our review was the use of CTRs by law enforcement agencies and not other entities, such as intelligence agencies.

For our first objective, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations and documentation from FinCEN on its implementation of CTR reporting requirements. We compared FinCEN’s CTR requirements and related actions against statutory requirements and best practices for performance management identified in our prior work.[7]

For our second objective, we analyzed FinCEN data on the number and characteristics of CTRs filed and accessed by law enforcement through FinCEN’s BSA Portal for fiscal years 2014–2023. We also obtained and analyzed available data on user access of CTRs in the internal systems of five law enforcement agencies.[8] We also conducted a generalizable survey of 327 federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies that have direct access to BSA reports.[9] For purposes of these analyses, an “agency” is any law enforcement entity that has a memorandum of understanding with FinCEN for access to BSA reports.

We also reviewed prior GAO reports, Inspector General reports, and other studies on use of CTRs. In addition, we assessed FinCEN’s use of its data to inform decisions on CTR policy against statutory requirements.

For our third objective, we used the FinCEN data described above to identify how changes to the CTR threshold might affect the number and characteristics of CTRs filed and accessed by law enforcement. We also reviewed documentation on CTR reporting requirements, including comment letters, and international standards.

For all three objectives, we interviewed officials from several federal agencies, including Treasury agencies, law enforcement agencies, and financial regulators. We also interviewed one tribal and nine state and local law enforcement agencies. We selected state and local law enforcement agencies to represent a range of types, locations, and number of CTRs accessed. Additionally, we interviewed four umbrella organizations representing tribal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. We also interviewed representatives of 13 depository institutions (selected to represent a range of institution types and asset sizes) and 11 industry groups (selected to reflect different types of CTR filers).[10] We also interviewed three BSA compliance consultants and representatives of four think tank and privacy groups and four automation technology companies, all selected for their expertise or public comments on relevant issues.[11]

More detailed information on our objectives, scope, and methodology is presented in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Bank Secrecy Act Roles and Responsibilities

The BSA and its implementing regulations provide the legal and regulatory framework for preventing, detecting, and deterring money laundering and terrorist financing.[12] The framework is designed to prevent criminals from using private individuals and financial institutions to launder the proceeds of their crimes and to detect criminals who successfully use the system to launder those proceeds. The main entities involved in implementing the framework include the following:

FinCEN. FinCEN oversees the administration of the BSA and related anti-money laundering regulations.[13] It implements the BSA through the issuance of regulations and guidance. FinCEN also has authority to enforce compliance with BSA requirements, and it serves as the repository of BSA reporting from financial institutions.[14] In addition, FinCEN analyzes information in CTRs and other BSA reports and shares such analyses with appropriate federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies.

Financial regulators and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). FinCEN has delegated its examination authority to certain federal agencies, including the financial regulators who supervise institutions for BSA compliance and IRS.[15] Financial regulators typically review CTRs during examinations of regulated entities, but they can also use them for investigations, according to agency officials. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) have their own BSA review teams that analyze BSA reports to identify potential violations of federal laws.

Financial institutions. The BSA authorizes FinCEN to impose reporting, recordkeeping, and other anti-money laundering requirements on financial institutions, including banks, casinos, and money services businesses.[16] By complying with BSA and anti-money laundering requirements—including CTR requirements—the institutions assist government agencies with detecting and preventing money laundering, terrorist financing, and other crimes. In turn, law enforcement agencies can use the information compiled by financial institutions to detect and deter criminal activity by investigating and prosecuting criminal actors.

Law enforcement agencies. Federal law enforcement agencies work to detect illicit activity and conduct criminal investigations, including those related to money laundering and criminal violations of BSA. These include multiple components within the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Homeland Security. Federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies also can use CTRs and other BSA reports to investigate and prosecute drug trafficking, terrorist acts, fraud, and other criminal activities.

· DOJ prosecutes violations of federal law, including criminal money laundering statutes and criminal violations of the BSA. Within DOJ, law enforcement agencies, including the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), play a role in conducting BSA-related criminal investigations. Additionally, law enforcement task forces, such as the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) (an independent component of DOJ), conduct illicit finance investigations.

· In the Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers and agents enforce applicable laws, including against illegal immigration, narcotics smuggling, and illegal importation. Agents of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations and the U.S. Secret Service investigate money laundering, illicit finance, and other financial crimes.

· In Treasury, IRS Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI) investigates potential criminal violations of tax laws and related financial crimes, including complex and significant money laundering activity.[17]

· The Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Office of Justice Services supports tribal law enforcement agencies and provides direct law enforcement services to Tribes. Bureau of Indian Affairs special agents are responsible for investigating crimes that involve violations of federal and tribal law that are committed in Indian country, including drug trafficking and cases of missing and murdered persons. The Bureau of Indian Affairs also partners with FBI on certain cases, including those related to financial crimes.

Bank Secrecy Act and Anti-Money Laundering Requirements

Among other anti-money laundering requirements, the BSA and its implementing regulations require financial institutions to file CTRs for cash transactions that exceed $10,000 (or aggregate to exceed $10,000) in a single day.[18] While the BSA did not identify a reporting threshold for CTRs, it required reports to be highly useful for law enforcement purposes. BSA directed Treasury to implement regulations to achieve that goal. Treasury introduced CTR requirements, including the $10,000 reporting threshold, through a regulation finalized in 1972.[19]

In addition to CTRs, financial institutions must file suspicious activity reports (SAR) for certain transactions that might be indicative of money laundering, tax evasion, or other criminal activities.[20] This includes filing SARs on suspicious transactions that appear designed to evade CTR requirements by structuring transactions in a deliberate manner.

Most financial institutions must also develop, administer, and maintain effective BSA and anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism programs.[21] Generally, these institutions must

· establish a system of internal controls to ensure ongoing compliance with the BSA and its implementing regulations;

· provide anti-money laundering compliance training for appropriate personnel;

· provide for independent auditing to test program compliance;

· designate a person or persons responsible for coordinating and monitoring compliance; and

· for financial institutions, such as banks and broker-dealers, establish risk-based procedures for verifying customer identity as part of the customer identification program and conduct ongoing customer due diligence.[22]

Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020

Congress enacted AMLA into law on January 1, 2021. The act updated aspects of the policy framework for anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism. Several aspects of AMLA are relevant to CTRs.

· AMLA Section 6216 requires Treasury to conduct a formal review of BSA regulations and guidance and submit a report to Congress on the review findings by January 2022.

· AMLA Section 6204 requires Treasury, in consultation with other federal agencies, state regulators, and other relevant stakeholders, to conduct a formal review of CTR reporting requirements and submit a report to Congress by January 2022 that includes proposed rules (as appropriate) to reduce any unnecessarily burdensome regulatory requirements.

· AMLA Section 6205 requires Treasury, in consultation with other federal agencies, state regulators, and other relevant stakeholders, to review whether the CTR dollar thresholds, including aggregate thresholds, should be adjusted, and submit a report to Congress by January 2022.

AMLA updated the purpose of BSA to include, among other things:

· providing for certain reports (including CTRs) or records that are highly useful in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations;

· preventing money laundering and terrorism financing;

· facilitating the tracking of money that has been sourced through criminal activity;

· assessing the money laundering, terrorism finance, tax evasion, and fraud risks to financial institutions; and

· establishing appropriate frameworks for information sharing among financial institutions, regulatory authorities, Treasury, and law enforcement authorities to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

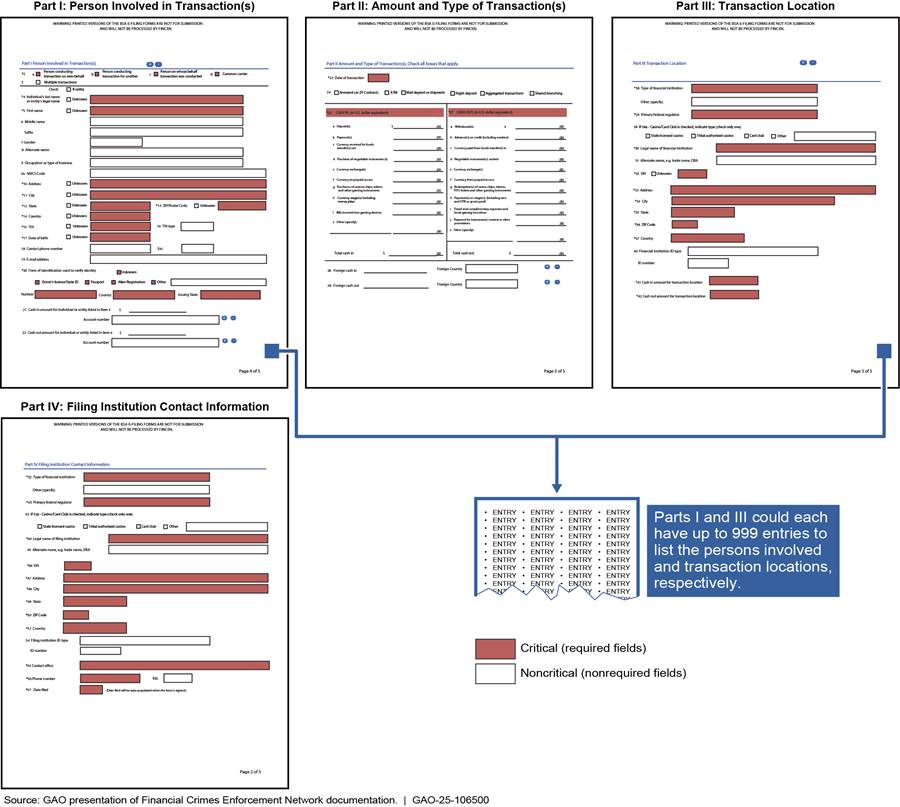

CTR Filing Process

The key steps for financial institutions filing CTRs include: (1) determining when to file a CTR (such as through automated alerts); (2) verifying the identity of the conductor (the person conducting the transaction); (3) collecting identifying information on the conductor and, if necessary, on the beneficiary (the person on whose behalf the transaction is being conducted); and (4) filing the CTR electronically with FinCEN (see fig. 1).

After filing, CTRs are stored in a BSA system of record (or database) managed by FinCEN. Access is available through BSA Portal—FinCEN’s user access interface—to authorized agencies at the federal, state, and local level of government that have entered agreements with FinCEN.[23] Law enforcement agencies, financial regulators, intelligence agencies, and others can use the system to retrieve identifying information, generate leads in investigations or prosecutions, begin new investigations or prosecutions, or analyze of illicit finance activities.

Law Enforcement Agencies’ Access to CTRs

Agencies can access CTRs directly through BSA Portal or indirectly by working through a coordinating entity. To obtain direct access to FinCEN’s BSA database, law enforcement agencies must enter a memorandum of understanding with FinCEN that specifies the terms and conditions under which they can use the reports. Agencies with a memorandum of understanding can use BSA Portal to access FinCEN’s BSA database through BSA Search, a secure web application that allows them to search the complete BSA database and allows FinCEN to capture access data.[24]

In addition, selected federal agencies have Agency Integrated Access agreements with FinCEN, enabling them to download BSA data into their internal computer systems. This allows agencies to combine FinCEN BSA data with their own databases to perform more complex analyses than available through BSA Portal.[25] As of March 2023, nine federal agencies had agreements to download BSA data.[26] FinCEN does not track agencies’ internal use of downloaded data. However, agencies are required to maintain access logs to track usage within their internal system as required by their agreements with FinCEN.

Agencies without direct access to BSA reports may request searches of the BSA database through FinCEN or through the agency designated as their state coordinator.

CTR Requirements Have Expanded and Do Not Fully Align with the Statutory Objective of Providing Highly Useful Information

Expansions to CTR requirements in statute and regulation have broadened the scope of institutions required to file and increased the amount of information collected. However, some of this information is reported by CTR filers to be burdensome and is infrequently used by law enforcement, inconsistent with the statutory objective of requiring reports that provide highly useful information to law enforcement. Financial institution representatives told us they faced challenges in collecting certain data, implementing exemptions, and complying with aggregation requirements. Further, FinCEN does not have performance goals or related measures specific to CTRs.

Laws and Regulations Have Expanded CTR Scope Despite Alternative Tools for Identifying Suspicious Transactions

Although the CTR threshold has remained the same for over 50 years, the scope of CTR requirements has expanded significantly. Statutes and requirements implemented through FinCEN’s regulations have increased the number and types of institutions required to file CTRs, as well as the amount of information collected in CTRs.[27] Figure 2 provides a timeline of the key statutes and regulations affecting CTRs.

aThe formal name of the act is the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act.

bAggregation involves treating multiple currency transactions as a single transaction if the financial institution has knowledge that they are by or on behalf of any person and result in either cash in or cash out totaling more than $10,000 during any one business day.

cSuspicious activity reports must be filed for certain suspicious transactions involving possible violation of law or regulation, including transactions that are broken up for the purpose of evading the BSA reporting and recordkeeping requirements.

dThe formal name of the act is Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism.

In 1987, Treasury added regulatory requirements for financial institutions to aggregate transactions for the purpose of filing CTRs.[28] The requirements intended to address transactions that were structured to evade CTR reporting.[29] These aggregation requirements increased CTR complexity by requiring financial institutions to aggregate multiple currency transactions associated with either the conductor (person making the transaction) or beneficiary (person for whom the transaction is made) in one business day. The requirements also include aggregating related transactions from multiple branches and sources of cash transactions (e.g., ATMs and certain transactions conducted by armored car services).[30]

FinCEN further expanded the types of information collected in CTRs when it designed the BSA database for electronic CTR filings, which became mandatory for filers in April 2013. FinCEN added fields to the CTR form and designated all data fields as critical (required to file) or noncritical (not required to file). Newly added noncritical fields included gender and North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code.[31] According to FinCEN’s 2012 guidance, fields were added in response to law enforcement feedback that the fields would be useful for their queries.[32] FinCEN officials told us the agency consulted its Data Management Council, comprising federal law enforcement and regulatory stakeholders, before making these form changes. The council reviews any changes to BSA reports, FinCEN officials said.

The CTR form consists of 57 fields, with some fields allowing for multiple records. For example, “person involved in transaction(s)” and “transaction location” fields may include up to 999 records (see fig. 3).

In 1992, Congress authorized Treasury to require financial institutions to file a suspicious activity report with FinCEN whenever they suspected illicit activity, providing law enforcement an additional tool for identifying suspicious transactions.[33] SAR requirements include reporting on cash transactions structured to avoid reporting requirements, such as those just below the CTR threshold.

However, Treasury made minimal changes to reduce or remove CTR reporting and aggregation requirements after SAR and structuring SAR requirements were added. The Money Laundering Suppression Act of 1994 required Treasury to implement exemptions to reduce the number and size of CTRs consistent with effective law enforcement.[34] Treasury implemented the exemptions in 1997 and 1998.[35] FinCEN made further changes to address recommendations we had made in 2008.[36] However, exemptions are limited to depository institutions and to certain transactions and customers meeting specific criteria.

AMLA required Treasury to consider streamlining CTR and SAR requirements and consider updating the CTR reporting threshold and other BSA reporting thresholds and issue reports with its findings by January 2022.[37] Treasury was past the statutory deadline and had not issued its report as of July 2024. In February 2024, we recommended that FinCEN develop and implement a communication plan to regularly inform Congress and the public about its progress implementing AMLA.[38]

Some Noncritical Information That CTR Filers Reported as Burdensome Is Infrequently Used by Law Enforcement

In public comments to FinCEN and in most of our interviews with financial institutions, representatives expressed that collecting information for certain noncritical CTR data fields can be burdensome. As discussed previously, FinCEN designates CTR data fields as critical or noncritical for electronic filing purposes. Critical fields include the name, address, and ID number of the persons involved in the transaction.[39] Noncritical fields include gender, NAICS code, and occupation. According to public comments and bank representatives we spoke with, examples of burdensome information collection included performing extra work to collect out-of-date information (such as occupation) and responding to customers’ reluctance to provide information on their gender or former occupation.[40]

Some noncritical fields cited as burdensome to complete, such as occupation and gender, are populated in most CTRs (see table 1). Although noncritical fields are not mandatory to file CTRs, FinCEN and BSA examiner guidance state that filers are expected to complete these fields if they have direct knowledge of the information.[41] This expectation may indirectly obligate filers to collect and report noncritical information. According to summary data FinCEN provided us, most CTR forms filed in fiscal years 2019–2023 included information in the noncritical fields of phone number, occupation or business type, gender, and email address.[42]

Table 1: Percentage of Noncritical Currency Transaction Report (CTR) Fields Populated by Filers, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

|

CTR field |

Percentage populated |

|

Phone number |

86% |

|

Occupation or business type |

85% |

|

Gender |

77% |

|

Email address |

62% |

|

Industry codea |

41% |

Source: Summary data provided by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). | GAO 25-106500

aThese are standard industry codes from the North American Industry Classification System. Filers must link the codes to an occupation or business type.

FinCEN has stated it added noncritical fields because feedback from law enforcement officials indicated such information was important for query purposes.[43] However, our survey results indicated law enforcement agencies infrequently use some of these noncritical fields.[44] We estimated that about 60 percent of law enforcement agencies rarely or never used gender information and about 75 percent rarely or never used NAICS code information.

In contrast, our survey indicated law enforcement agencies frequently used critical fields, such as those related to account and identification numbers and location. For example, an estimated 94 percent of law enforcement agencies at least occasionally used account number, and about 85 percent at least occasionally used location (see fig. 4).[45]

Figure 4: Estimated Percentage of Law Enforcement Agencies That Used Selected Currency Transaction Report (CTR) Fields At Least Occasionally

Note: We use the term “at least occasionally” to cover survey responses that reported using CTR fields “occasionally” or “frequently.” The response options to this survey question were: frequently; occasionally; not often; never; and don’t know.

Section 6204 of AMLA directs Treasury to review CTR processes and requirements and propose changes to reduce unnecessary filer burden while still ensuring that the information in CTRs is highly useful in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations. The section also calls for Treasury to determine whether the number and nature of CTR fields need to be adjusted. According to FinCEN officials, this review has not been completed due to competing priorities. These priorities include addressing new authorities and mandates imposed by AMLA, according to officials.[46]

As of May 2024, officials told us FinCEN was in the process of consulting with law enforcement, regulatory, and other stakeholders to review CTR requirements and consider potential revisions. They noted a commitment to making changes as needed to ensure law enforcement continues to have access to highly useful information while eliminating unnecessary regulatory burdens.[47] However, FinCEN has not yet determined what actions, if any, it will take in response to its review, including whether it will make changes to CTR fields. By eliminating optional, noncritical fields that are not frequently used by law enforcement, FinCEN could reduce unnecessary burden on financial institutions while maintaining information highly useful to law enforcement.

Institutions Face Constraints Using Exemptions

As discussed previously, depository institutions can exempt certain customers from CTR filing requirements.[48] However, these exemptions are limited to exempting customers that are other banks, government agencies, or business customers meeting specific criteria. FinCEN implemented two types of exemptions—Phase I and Phase II—for different customer types (see table 2). The exemptions vary, based on customer type and business activities, in whether they require the institution to file an exemption report, or whether they require an annual review of the exemption.[49]

|

Type of customer |

File a Designation of Exempt Person reporta |

Ineligible business activityb |

Annual reviewc |

|

Phase I |

|

|

|

|

Banks operating in the U.S. |

No |

n/a |

No |

|

Federal, state, local, or inter-state governmental departments, agencies, or authorities |

No |

n/a |

No |

|

Entities listed on the major national stock exchanges |

Yes |

n/a |

Yes |

|

Certain subsidiaries of entities listed on the major national stock exchanges |

Yes |

n/a |

Yes |

|

Phase II |

|

|

|

|

Non-listed businesses |

Yes |

No more than 50% of gross revenues derived from ineligible activity |

Yes |

|

Payroll customersd |

Yes |

n/a |

Yes |

Legend: n/a = Not applicable

Source: GAO analysis of FinCEN guidance. | GAO‑25‑106500.

aWhen a depository institution chooses to exempt certain customers under Phase I or Phase II, it must electronically file a one-time Designation of Exempt Person report (FinCEN Form 110).

bFinCEN has identified a list of ineligible activities that apply to non-listed businesses. Ineligible activities include money transmission, lottery, gaming, and sales of motor vehicles, of which a business can derive no more than 50 percent of its gross revenues to be exempt.

cAt least once each year, banks must review the eligibility of an exempt person that is a listed public company, a listed public company subsidiary, a non-listed business, or a payroll customer to determine whether such person remains eligible for an exemption.

dPayroll customers operate a firm that frequently (five or more transactions within a year) withdraws more than $10,000 to pay its U.S. employees in currency.

Our analysis of CTR data found that over a 10-year period, about 60 percent of CTRs that were filed included businesses.[50] Although not all of these businesses may be eligible for exemption, there is potential to identify and expand exemptions to capture some portion of cash intensive businesses that have routine cash transactions that are considered low-risk for money laundering.

Representatives for large and regional banks generally said their institutions used minimal exemptions because they are more time-consuming, costlier, and pose greater compliance risk than filing CTRs. Representatives for many smaller depository institutions (credit unions, community banks, or mid-sized banks) said they did not file many exemptions because many of their business customers did not qualify for exemptions based on the restrictive eligibility criteria.

Phase I exemptions for businesses are generally limited to companies listed on major national stock exchanges (listed companies), restricting their use to a small share of business customers.[51] There were about 6,000 companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq Stock Market, compared to nearly 11 million business customers identified in CTR filings in fiscal year 2023. Listed companies make up a small portion of the roughly 321,000 large operating companies that FinCEN estimated would be exempt in supplementary information included with its beneficial ownership reporting rule.[52]

Bank representatives we interviewed identified challenges with Phase II exemptions, including the following:

Documenting exemption decisions. The supplementary information included with FinCEN’s 2008 final rule amending exemptions stated that banks do not need to maintain separate documentation for exemption determinations based on activities performed for other BSA obligations, such as the requirement to maintain a customer identification program.[53] Instead, the bank may make notations within its other BSA documentation. However, some bank representatives we interviewed believed additional steps were necessary to support Phase II exemptions. FinCEN officials told us that banks may obtain exemption-related information through other BSA obligations but must comply with all applicable exemption documentation requirements.[54]

Determining extent of ineligible activities. According to some bank representatives we interviewed, banks are reluctant to exempt non-listed businesses that engage in some ineligible business activities because it is difficult or time-consuming to determine and monitor the scope of these activities. Specifically, banks need to identify what portion of a Phase II business’s services constitute ineligible activities and whether these activities account for more than 50 percent of the business’s gross revenues, which would render the business ineligible for exemption. CTR data by industry indicate that CTRs are commonly filed on business categories, such as grocery stores or gas stations, that may conduct some ineligible activities, such as money transmission, in addition to their primary services (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Number of Currency Transaction Reports (CTR) Filed, by Selected Industry Type, Fiscal Years 2014–2023

Notes: Industry types are based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code, which is a noncritical (nonrequired) field. CTRs may be filed without reporting a NAICS code for any party. The figures represent CTRs with at least one industry type reported for a party. FinCEN defines the term party as the person(s) involved in the transactions. A party can be an individual or a business. A single CTR may include multiple parties with different industry types and are counted for each industry reported. A CTR that reported more than one party in the same industry would be counted only once for that industry.

Further, our analysis shows that law enforcement accessed CTRs filed on grocery stores, gas stations, and convenience stores, which may conduct some portion of ineligible activities, proportionally less than other industries (see fig. 6). This indicates that these CTRs may be relatively less useful than CTRs of other industries.[55]

Figure 6: Proportion of Currency Transaction Reports (CTR) Filed in Fiscal Years 2014–2023 That Were Accessed by Law Enforcement in Fiscal Year 2023, by Selected Industry Type

Notes: Percentages represent Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) accessed through FinCEN’s BSA Portal or the internal systems of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Internal Revenue Service Criminal Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces. Definitions of access vary depending on the system. Industry types are based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code, which is a noncritical (nonrequired) field. CTRs may be filed without reporting a NAICS code for any party. The figures represent CTRs with at least one industry type reported for a party.

Additionally, officials from IRS-CI, Secret Service, and Homeland Security Investigations supported expanding CTR exemptions to include more cash businesses that banks determine to be low-risk for money laundering, such as well-established restaurants or gas stations. IRS-CI officials said this could reduce the number of CTRs filed on legitimate cash businesses that pose minimal risk of money laundering. As discussed earlier, as of July 2024, Treasury was past the deadline to complete its AMLA-mandated review on streamlining CTR requirements, including the use of exemptions.

Regulators and Financial Institutions Identified Challenges to Complying with Aggregation Requirements

Many financial institution representatives and some financial regulators we spoke with cited aggregation requirements as a key challenge in banks’ implementation of CTR requirements, with some banking representatives noting the requirements can be unclear.

Many financial institution representatives we spoke with told us that aggregating transactions by conductor was a key challenge.[56] For example, some of these representatives highlighted challenges in collecting information on conductors that are not the institution’s customer.[57] In such cases, financial institutions must either collect information at the time of the transaction or conduct research or follow up after the transaction. Representatives from two banks suggested simplifying the process by removing the requirement to aggregate transactions based on conductors and applying it solely to the beneficiary (typically a customer of the depository institution). FinCEN officials told us they are soliciting and evaluating stakeholder input on the usefulness of both conductor and beneficiary aggregation as part of FinCEN’s consultation efforts under Section 6204 of AMLA.

Some bank representatives said their institutions had difficulty determining whether or when to start collecting information on conductors of transactions. For example, representatives from one bank cited challenges anticipating whether a conductor will conduct multiple transactions totaling over $10,000 in a business day, triggering the need to file a CTR.

Banks whose representatives we interviewed differed in their policies regarding the collection of conductor information. For example, some collected information on all transactions regardless of amount, some started at low dollar values (such as $500), and some collected information only when the transaction exceeded $10,000. Representatives from one large bank said it collected conductor information starting at $500 to comply with its interpretation of aggregation requirements, which they said often results in collecting unnecessary information (because it does not result in a CTR). However, another representative said many banks collect conductor information for every transaction, regardless of amount, as a best practice. In contrast, three large banks we interviewed had a different interpretation of the aggregation rules and guidance, opting not to collect conductor information for transactions below the $10,000 threshold.

According to FinCEN’s frequently asked questions, filers are not required to collect conductor information in certain circumstances. A CTR filer can instead select an “aggregate transactions” checkbox if the following conditions are met: (1) the financial institution did not identify any of the individuals conducting the related transactions, (2) all the transactions were below the $10,000 threshold, and (3) at least one of the aggregated transactions was a teller transaction.

Many financial institution representatives we spoke with said aggregation requirements resulted in increased CTR compliance costs, including staff resources and IT investments. For example, aggregation can require tracking multiple cash sources, as discussed earlier. Some bank representatives also cited difficulty aggregating and reporting cash transactions by individual business names under sole proprietorships. They also cited challenges tracking transactions by location for legal entities with multiple locations.[58]

Officials from some federal law enforcement agencies and over half of the state and local law enforcement agencies we interviewed said that large aggregated CTRs can be difficult to review and are not necessarily useful. One large bank described encountering CTRs with more than 750 parties, which the bank splits into separate CTRs by regional locations to capture all the transaction details.[59] Officials from OCDETF Fusion Center and CBP noted that large consolidated CTRs may aggregate unrelated transactions, making it difficult for investigators to establish a money trail. Although our data analysis shows that law enforcement agencies generally access CTRs with a larger number of parties, this does not necessarily indicate that these CTRs are more useful. Instead, it may be that the search criteria match CTRs with more parties simply because they contain more data to match.

AMLA requires FinCEN to review CTR requirements to determine if changes are needed to reduce unnecessary burden for filers and ensure that CTRs provide highly useful information to law enforcement.[60] This review includes assessing potential improvements to CTR aggregation for entities with common ownership. Further, Section 6205 of AMLA requires Treasury to review and determine whether the CTR dollar thresholds, including aggregate thresholds, should be adjusted.

As of May 2024, FinCEN officials told us the agency was in the process of conducting these reviews by taking steps such as soliciting and evaluating input from relevant stakeholders. As previously discussed, officials also noted FinCEN’s commitment to making changes as needed to ensure law enforcement continues to have access to highly useful information while eliminating unnecessary regulatory burdens. However, FinCEN has not completed the reviews that were due in January 2022 or determined what changes, if any, it will make to aggregation requirements. Simplifying and clarifying aggregation requirements could reduce unnecessary burden on financial institutions while still providing useful information to law enforcement.

FinCEN Does Not Have a Performance Management Process Specific to CTRs

FinCEN has not established a performance management process that defines performance goals and measures and is specifically related to CTR effectiveness. We have previously defined a performance management process as a process by which organizations

· set goals to identify the results the agency seeks to achieve,

· collect performance information to measure progress, and

· use that information to assess results and inform decisions to ensure further progress toward achieving those goals.[61]

We have also previously identified key practices to help federal officials manage and assess the performance of their efforts, including individual programs and activities.[62] CTRs are an important program activity because they result in the majority of BSA filings (about 75 percent) and have a significant impact on both law enforcement agencies and financial institution filers. These key practices state that performance goals should be objective, measurable, and quantifiable.

FinCEN’s performance plan identifies goals from Treasury’s strategic plan, including the objective of increasing financial system transparency. While the plan has a performance measure on the usefulness of BSA reports to law enforcement, the measure is not specific to CTRs.[63] In addition, our previous work has found that the surveys FinCEN uses for this performance measure were not reliable.[64] FinCEN officials noted the challenges of quantifying the use of CTRs, as described in DOJ’s annual report on agencies’ use of BSA reporting required by AMLA.[65] The officials also said the agency is considering performance management steps, such as more targeted measures for tracking the usefulness of BSA reports, but does not yet have goals or measures related to CTRs.

FinCEN already collects data on law enforcement’s access of CTRs. Some of these data, such as the number and percentage of CTRs accessed by law enforcement, could serve as a valuable source of evidence to measure CTR usefulness. By developing a performance management process, including goals and related measures, that is targeted to CTRs, FinCEN could better monitor the effectiveness of CTRs and identify modifications and improvements to better ensure CTRs meet statutory objectives.

Law Enforcement Agencies Find CTRs Useful, but Did Not Access Most CTRs

Our survey found that nearly all of the 327 law enforcement agencies with direct access to CTRs used them and considered them important to investigations and prosecutions. However, these agencies accessed a small portion of all CTRs filed. This suggests that there are opportunities to reduce the volume of CTRs without compromising their usefulness to law enforcement.

Law Enforcement Reported CTRs Can Be a Useful Source of Information

We conducted a generalizable survey of all 327 law enforcement agencies that had a memorandum of understanding with FinCEN for direct access to BSA reports (165 federal and 162 state and local agencies).[66] We received responses from 197 agencies (89 federal and 108 state and local agencies), an overall response rate of 60 percent. We asked about agencies’ use of CTRs from January 2021 through January 2024.

Use of CTRs

We estimated that 96 percent of law enforcement agencies used CTRs from January 2021 through January 2024. Federal agencies used CTRs at generally the same rates as state and local agencies.[67] Surveyed agencies reported that CTRs were relevant to a range of crimes, especially fraud, money laundering, drug trafficking, and organized crime (see fig. 7). In addition, FBI provided data indicating that CTRs are most often relevant to its program that investigates drug trafficking and organized crime.

Figure 7: Estimated Percentage of Law Enforcement Agencies That at Least Occasionally Identified Currency Transaction Reports Relevant to Selected Crimes, January 2021–January 2024

Notes: We conducted a generalizable survey of 327 law enforcement agencies that had an active memorandum of understanding with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network to access Bank Secrecy Act reports as of June 30, 2023. We use the term “at least occasionally” to cover survey responses that reported using currency transaction report fields “occasionally” or “frequently.” The response options to this survey question were “frequently,” “occasionally,” “not often,” “never,” and “not applicable to agency.”

According to our survey, federal, state, and local agencies generally align in their use of CTRs by crime type. Law enforcement agency officials provided the following examples of investigations in which CTRs were useful:

· A complex money laundering investigation in which CTRs helped investigators identify patterns of money movement and additional bank accounts associated with the scheme.

· A benefits fraud investigation in which CTRs helped investigators detect a business owner defrauding a government program.

· Tax fraud investigations in which CTRs helped identify retail businesses that may be underreporting cash receipts.

· Money laundering investigations in which suspects import cash to the U.S., generating CTRs and alerting law enforcement to investigate the source of the cash.

Law enforcement agencies use CTRs as a searchable database to confirm information about subjects of existing investigations and potentially discover new leads.[68] Officials from most law enforcement agencies we interviewed told us they search all BSA reports at once, rather than just CTRs. Investigators search for information, such as a subject’s name, date of birth, or other identifying information, according to FinCEN officials. An estimated 91 percent of surveyed agencies at least occasionally used CTRs to develop leads for existing investigations. In addition, an estimated 47 percent of agencies searched CTRs as a standard practice for each investigation or prosecution.

Law enforcement agencies sometimes also use CTRs to develop cases and initiate new investigations, according to our interviews and survey. Officials from many of the law enforcement agencies we interviewed told us their agencies did not typically use CTRs to initiate investigations. Some of these officials said it was more common to initiate investigations in response to a SAR. However, an estimated 67 percent of surveyed agencies at least occasionally used CTRs to identify the need for new investigations. For example, IRS-CI has used CTRs for case development projects in the areas of pandemic relief fraud, tax fraud, and casino-based money laundering, according to officials.[69]

Importance of CTRs

An estimated 91 percent of law enforcement agencies reported that CTRs were important to investigations or prosecutions. According to our survey results, the most important aspect of CTRs was providing unique account information—about 75 percent of surveyed agencies considered it very important.

Officials from most law enforcement agencies we interviewed emphasized that criminals know about CTR reporting requirements and modify their behavior to avoid CTRs. Many of these officials said CTR requirements force criminals to act in ways that increase chances of detection through other methods, such as structuring SARs. Financial institutions reported more than 900,000 structuring activities on SARs each fiscal year from 2019 through 2023.[70] From 2019 through 2022, law enforcement agencies accessed structuring SARs through BSA Portal more than 450,000 times each fiscal year.[71]

Officials from many law enforcement agencies we spoke with told us that CTRs are more likely to contain accurate information than other sources or may contain information that is not available from other sources. For example, IRS-CI officials said a CTR may capture the identity of a person conducting a transaction on behalf of a business, while bank records may not, which could help trace illicit currency movements. Additionally, some officials said it would often be harder and more time- or resource-intensive to obtain information from alternative sources, potentially hindering investigations.

Still, most surveyed agencies reported they would have been able to use information from other sources, such as SARs, if CTR information had been unavailable. An estimated 90 percent of agencies would have been able to use SARs instead of CTRs from January 2021 through January 2024. An estimated 64 percent of agencies would have been similarly efficient in their work by using SARs instead of CTRs (see table 3).

Table 3: Estimated Percentage of Law Enforcement Agencies That Were Able to Use Other Sources Instead of Currency Transaction Reports, January 2021–January 2024

|

|

Estimated percentage |

95 percent confidence interval |

|

Bank records |

91% |

87–95% |

|

Yes, with similar efficiency |

51% |

44–59% |

|

Yes, but with less efficiency |

40% |

32–47% |

|

Suspicious activity reports (other than structuring) |

90% |

86–95% |

|

Yes, with similar efficiency |

64% |

57–72% |

|

Yes, but with less efficiency |

26% |

19–32% |

|

Suspicious activity reports (structuring) |

88% |

83-93% |

|

Yes, with similar efficiency |

60% |

52–67% |

|

Yes, but with less efficiency |

28% |

21–35% |

|

Other Bank Secrecy Act reports |

79% |

73–85% |

|

Yes, with similar efficiency |

45% |

37–53% |

|

Yes, but with less efficiency |

34% |

27–42% |

|

314(a) programa |

66% |

58–75% |

|

Yes, with similar efficiency |

25% |

17–34% |

|

Yes, but with less efficiency |

41% |

32–50% |

|

Tax records |

63% |

55–71% |

|

Yes, with similar efficiency |

26% |

19–33% |

|

Yes, but with less efficiency |

37% |

29–45% |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106500

Notes: We conducted a generalizable survey of 327 law enforcement agencies that had an active memorandum of understanding with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to access Bank Secrecy Act reports as of June 30, 2023. Upper- and lower-bound 95 percent confidence intervals are provided for each estimate.

aFinCEN’s 314(a) program enables law enforcement agencies, through FinCEN, to contact U.S. financial institutions to locate accounts and transactions of subjects that may be involved in terrorism or money laundering.

IRS-CI provided data showing that, on average, about 35 cases originated from CTRs each fiscal year from 2020 to 2022. Other than IRS-CI, few law enforcement agencies track whether using CTRs leads to outcomes such as case originations, indictments, convictions, or recoveries.[72] Officials from some agencies we interviewed said they do not track use of CTRs separately from other sources of information used during an investigation or prosecution. Additionally, officials from four agencies told us they do not mention CTRs in court records, warrants, or other evidentiary documents.[73] An estimated 13 percent of surveyed agencies reported tracking their CTR use. Among 23 agencies that described on our survey how they tracked their CTR use, two described tracking outcome-related metrics.[74]

In response to a Congressional mandate, DOJ began submitting an annual report to Treasury in 2022 that is required to contain statistics, metrics, and information on contributions of BSA reports to law enforcement outcomes.[75] In a 2022 report, we found that law enforcement agencies had difficulty linking BSA reports to outcomes, and some reported difficulty determining what it means to “use” a BSA report.[76] We made two recommendations for DOJ to improve data collection and analytical rigor for its annual reports to Treasury, and as of July 2024, DOJ had implemented one of these two recommendations.[77] The second annual DOJ report to Treasury, covering fiscal year 2022, did not include any outcome metrics specifically for CTRs.[78]

A Small Portion of CTRs Are Accessed by Law Enforcement

Most CTRs are not accessed by law enforcement agencies, according to our analysis of data from FinCEN’s BSA Portal and agencies’ internal systems.[79]

Five federal agencies—FBI, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, IRS-CI, CBP, and DEA—accounted for about two thirds of all law enforcement CTR accesses through BSA Portal in fiscal years 2019–2023. Overall, personnel from these five agencies constituted more than half of all active law enforcement users on BSA Portal. All except DEA also have Agency Integrated Access agreements with FinCEN, permitting them to allow personnel to access BSA reports on their internal systems.[80] DEA officials told us that the agency has requested Agency Integrated Access, and FinCEN officials told us FinCEN is working with DEA to draft an Agency Integrated Access agreement to provide DEA access.[81]

Accessing a CTR does not necessarily mean that law enforcement personnel viewed it or used it in their work. For example, officials said IRS-CI’s internal system records access when a user loads a page with information from multiple sources, including CTRs, making it impossible to determine if the user looked at or used a particular CTR.[82] Similarly, BSA Portal allows law enforcement users to download batches of up to 5,000 BSA reports per session, according to FinCEN officials. Accessing a CTR through this method does not ensure law enforcement personnel reviewed or used it.

Conversely, BSA Portal access data may not always capture law enforcement’s views or use of CTR information. Specifically, when using BSA Portal, users can view CTR fields on a summary search results screen without opening or downloading the CTR and generating an access record.[83] This means that law enforcement personnel may use CTR information in their work without it being reflected in the access data. However, officials from two federal law enforcement agencies that are heavy users of CTRs told us that investigators would typically review a relevant report in BSA Portal rather than viewing only summary data.

CTRs Accessed through BSA Portal in Fiscal Years 2014–2023

A small portion of the CTRs filed were ever accessed by law enforcement through FinCEN’s BSA Portal during the period of our review. Of the more than 167 million CTRs filed from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2023, about 5.4 percent (about 9 million) were accessed through the portal.[84] FinCEN’s policy, prior to a system transition in June 2024, was to make CTRs accessible indefinitely.[85] Because they were available for longer, earlier years’ CTRs were more likely to be accessed. Fewer than 7 percent of CTRs were accessed within 5 years of filing, and 7.6 percent of fiscal year 2014 CTRs had been accessed by the end of fiscal year 2023 (see table 4).[86]

Table 4: Proportion of Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) Accessed by Law Enforcement Agencies in BSA Portal Within 3, 5, and 9 Years of Filing, Fiscal Years 2014–2023

|

|

Proportion of CTRs |

Filing years included |

|

Accessed within 3 years |

5.7% |

2014–2020 |

|

Accessed within 5 years |

6.6% |

2014–2018 |

|

Accessed within 9 years |

7.6% |

2014 |

Source: GAO analysis of Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) data. | GAO‑25‑106500

Notes: This table displays CTRs accessed through BSA Portal and does not include CTRs accessed on the internal systems of Integrated Access agencies. CTRs were counted as accessed within 3 years if they were accessed by the end of the third fiscal year after the fiscal year in which they were filed.

Among the 5.4 percent of CTRs accessed through BSA Portal, most were accessed once. Fewer than 1 percent of CTRs filed in fiscal years 2014 through 2023 were accessed through the portal more than twice. However, law enforcement officials noted investigators may view CTRs downloaded from BSA Portal multiple times outside of the portal, or share them with colleagues, which would count as a single access in our analysis.[87] This suggests some CTRs that were only accessed once may have been viewed many times.[88]

CTRs Accessed through Either BSA Portal or Agency Internal Systems in Fiscal Year 2023

A significant portion of law enforcement’s CTR use occurs on internal systems of agencies with Agency Integrated Access. However, these systems differ in how they display CTR information, how users access it, and how such access is recorded. As a result, data on CTR accesses from internal systems are not directly comparable between agencies or with FinCEN’s BSA Portal.[89] To present a more comprehensive picture, we combined BSA Portal data with internal system data from agencies with Agency Integrated Access.[90]

Our analysis of the combined data for fiscal year 2023 (the most recent full year with complete data) showed that law enforcement agencies accessed between about 3.9 million and about 4.2 million of the CTRs filed since fiscal year 2014.[91] This represented less than 3 percent of the more than 167 million CTRs filed in that period. See figure 8 for law enforcement access to CTRs on BSA Portal or agencies’ internal systems.

Figure 8: Number of CTRs Accessed by Law Enforcement on BSA Portal or Agency Internal Systems in Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23), for CTRs Filed in Fiscal Years 2014–2023

Notes: Internal systems category includes CTRs accessed on the internal systems of IRS Criminal Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces, and ICE’s newer internal system. Systems differ in how they display CTR information and record CTR access.

aWe were not able to determine the extent to which CTRs accessed by FBI or ICE’s older system overlap with CTRs accessed by other law enforcement agencies because FBI and ICE did not provide us with FinCEN CTR identification numbers for these systems. For that reason, these numbers are presented separately.

Officials from the Department of Homeland Security said one reason most CTRs are not accessed could be because CTRs largely reflect lawful activity, making them less relevant to law enforcement than SARs, which focus on suspicious activity. According to Department of Homeland Security officials, CTRs typically are used to support SAR information and may not be useful unless they contain information related to a SAR. In addition, officials from one law enforcement agency told us that an absence of CTR filings can provide useful information about the sufficiency of a financial institution’s anti-money laundering program, making even search results with no matches useful to investigators.

Characteristics of CTRs Accessed by Law Enforcement

We compared the characteristics of CTRs that were accessed by law enforcement personnel in fiscal year 2023 to those that were not accessed.[92] We identified the following trends:

· Newer CTRs were accessed more frequently. Law enforcement personnel accessed more recent CTRs more frequently than older ones. For example, during fiscal year 2023, they accessed roughly four times as many 2022 filings as 2014 filings (see fig. 9).[93] Despite this, law enforcement personnel continue to access older CTRs, particularly on internal systems.

Figure 9: Number of CTRs Accessed by Law Enforcement on BSA Portal or Agency Internal Systems in Fiscal Year 2023, by Fiscal Year Filed

Notes: Includes CTRs accessed through BSA Portal and CTRs accessed on the internal systems of IRS Criminal Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Systems differ in how they display CTR information and record CTR access. This analysis does not include CTRs accessed on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) internal system because FBI was not able to provide complete information on filing years for older CTRs.

· CTRs with multiple parties were accessed more frequently. CTRs with multiple parties, such as the transaction’s conductor and beneficiaries, were more likely to be accessed by law enforcement (see table 5). This is because CTRs are used as a searchable database for investigation subjects and other persons of interest. However, some law enforcement agency officials told us that CTRs with high numbers of parties are difficult to interpret and likely to generate “false positive” search results.

Table 5: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) Filings, Fiscal Years 2014–2023, and Proportion Accessed in Fiscal Year 2023, by Number of Parties

|

|

Number of CTRs filed, fiscal years 2014–2023 |

Number of CTRs accessed by law enforcement agencies in fiscal year 2023 (proportion) |

|

All CTRs |

167,525,214 |

3,929,286 (2.3%) |

|

Missing/zero parties |

92,301 |

2,290 (2.5%) |

|

One to five parties |

164,313,175 |

3,755,208 (2.3%) |

|

Six to 50 parties |

3,039,961 |

130,005 (4.3%) |

|

More than 50 parties |

79,777 |

41,783 (52.4%) |

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑25‑106500

Notes: Includes CTRs accessed through BSA Portal and CTRs accessed on the internal systems of IRS Criminal Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Systems differ in how they display CTR information and record CTR access. This analysis does not include CTRs accessed on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) internal system because FBI did not provide information on the number of parties.

· Money services business CTRs were accessed at a higher rate than those of other financial institutions. Depository institutions filed the majority (86 percent) of CTRs in fiscal years 2019–2023, followed by casinos (about 9 percent), and money services businesses (about 3 percent).[94] However, money services business and casino CTRs were accessed at a higher rate than CTRs filed by other types of financial institutions, as of fiscal year 2023 (see table 6). Nearly 10 percent of CTRs filed by money services businesses were accessed that year, compared to less than 3 percent of CTRs filed by depository institutions. According to IRS-CI officials, CTRs from money services businesses are particularly useful for investigating tax fraud.

Table 6: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) Filings, Fiscal Years 2019–2023, and Proportion Accessed in Fiscal Year 2023, by Filer Type

|

|

Number of CTRs filed in fiscal years 2019–2023 |

Number accessed by law enforcement agencies in fiscal year 2023, excluding FBI (proportion) |

Number accessed by Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in fiscal year 2023 (proportion)a |

|

All CTRs |

90,403,652 |

2,772,949 (3.1%) |

193,001 (0.2%) |

|

Money services business |

2,967,403 |

291,178 (9.8%) |

8,596 (0.3%) |

|

Casino |

8,277,569 |

355,905 (4.3%) |

23,884 (0.3%) |

|

Depository institution |

77,789,487 |

2,073,259 (2.7%) |

157,578 (0.2%) |

|

Other |

1,361,142 |

52,530 (3.9%) |

2,943 (0.2%) |

|

Missing/unknown |

8,051 |

77 (1.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑25‑106500

Notes: Includes CTRs accessed through BSA Portal and CTRs accessed on the internal systems of IRS Criminal Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Systems differ in how they display CTR information and record CTR access. The other category includes CTRs filed by securities and futures filers as well as filers that selected the ‘other’ filer type option.

aWe were not able to determine the extent to which CTRs accessed by FBI overlap with CTRs accessed by other law enforcement agencies because FBI did not provide us with FinCEN CTR identification numbers.

· Access rates differ by party industry. CTRs request that filers report a party’s occupation or type of business and assign a related NAICS code.[95] But occupation/business type and NAICS code are noncritical fields and fewer than half of CTRs report at least one NAICS code. The top reported industries were grocery or convenience stores, restaurants or bars, and gas stations, but CTRs with parties in these industries were accessed at lower rates than others in fiscal year 2023 (see table 7).[96]

Table 7: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) Filings, Fiscal Years 2014–2023, and Proportion Accessed in Fiscal Year 2023, by Selected Industry

|

|

Number of CTRs filed in fiscal years 2014–2023a |

Number accessed by law enforcement agencies in fiscal year 2023 (proportion) |

|

All CTRs |

167,525,214 |

3,929,286 (2.3%) |

|

Missing/unknownb |

105,078,134 |

2,517,405 (2.4%) |

|

1. Food and beverage retailers |

8,702,093 |

154,144 (1.8%) |

|

2. Food services and drinking places |

8,513,308 |

132,395 (1.6%) |

|

3. Gasoline stations |

7,504,655 |

109,186 (1.5%) |

|

4. Administrative and support services |

5,297,020 |

120,337 (2.3%) |

|

5. Motor vehicle and parts dealers |

4,484,701 |

105,452 (2.4%) |

|

6. Credit intermediation and related activities |

4,383,286 |

128,048 (2.9%) |

|

7. Couriers and messengers |

3,795,634 |

72,940 (1.9%) |

|

8. Merchant wholesalers, durable goods |

2,293,877 |

74,319 (3.2%) |

|

9. Merchant wholesalers, nondurable goods |

2,202,856 |

60,853 (2.8%) |

|

10. Miscellaneous store retailers |

1,787,116 |

47,569 (2.7%) |

|

All others |

23,732,101 |

706,998 (3.0%) |

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑25‑106500

Notes: Includes CTRs accessed through BSA Portal and CTRs accessed on the internal systems of IRS Criminal Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Forces, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Systems differ in how they display CTR information and record CTR access. Industries are based on three-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes. This analysis does not include CTRs accessed on FBI’s internal system because FBI did not provide information on NAICS codes.

aThe sum of CTRs by industry is higher than the total number of CTRs filed because a single CTR may report on parties in more than one industry. A CTR is counted for each industry reported, but multiple parties in the same industry are counted only once.

bNAICS code is a noncritical (nonrequired) field and CTRs may be filed without reporting a NAICS code for any party. Filers are expected to complete noncritical fields if they have direct knowledge of the information.

As discussed earlier, the BSA called for CTRs to be highly useful for law enforcement purposes. AMLA required Treasury to review CTR requirements and reporting thresholds to reduce unnecessary burdens on filers while maintaining usefulness for law enforcement. Our analysis shows that most CTRs are never accessed by law enforcement, suggesting room for optimization. FinCEN does not use access data to measure CTR usefulness or evaluate CTR requirements and instead relies on user surveys and other measures of value, according to FinCEN officials. By reducing less relevant CTR filings, FinCEN could reduce the burden on financial institutions while preserving valuable CTRs. Additionally, our analysis identified characteristics of those CTRs that are most commonly accessed. In its efforts to reduce CTR filings, leveraging such data could assist FinCEN in targeting reductions of less useful CTRs.

Changing the CTR Threshold Involves Balancing Law Enforcement Needs Against Filers’ Compliance Burden

CTR Filings Have Increased as Reporting Threshold Has Remained at 1972 Level

The CTR reporting threshold that Treasury established in 1972 has not been adjusted for inflation, possibly contributing to an increase in CTR filings.[97] CTR filings rose by about 62 percent between fiscal year 2002 and fiscal year 2023, from 12.9 million to 20.9 million. AMLA required Treasury to review the CTR threshold, taking into account factors such as the cost to financial institutions and whether CTR thresholds should be tied to inflation or otherwise be adjusted based on other factors consistent with the purposes of the BSA, including the BSA’s objective of providing highly useful information to law enforcement.

As inflation has increased nominal (unadjusted) prices of goods and services, the number of cash transactions made with financial institutions exceeding the fixed $10,000 CTR threshold would have likely increased as a result, holding other factors constant. The $10,000 threshold that was set in 1972 is equivalent to about $72,880 in 2023 dollars.[98] An inflation-adjusted threshold would have reduced the number of CTRs filed by at least 90 percent in each fiscal year since 2014, with the percentage reduction increasing slightly each year (see fig. 10).

Figure 10: Effect on Filing Volume If Currency Transaction Report (CTR) Threshold Had Been Adjusted for Inflation

Notes: We use fiscal year 2014–2023 data because comparable data were unavailable prior to fiscal year 2014. We use the fiscal year Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics to calculate the inflation-adjusted thresholds for each fiscal year. Between fiscal years 2014 and 2023, the inflation-adjusted threshold increased from $57,348 to $73,445. This figure portrays the inflation-adjusted threshold in fiscal year rather than calendar year inflation to align with FinCEN’s fiscal year CTR data.

Factors other than inflation may also have affected the number of CTRs filed. Changes in consumer behavior, such as a further shift from cash to credit card payments during the COVID-19 pandemic, may have reduced CTR filings in fiscal year 2020.[99] CTR rule changes, such as those related to exemptions, may have decreased filings in 2009, according to a 2010 FinCEN study.[100] In addition, automation technology has increased the number of CTRs filed, particularly for aggregated CTRs, according to three bank and credit union representatives. All software vendors we interviewed said automated systems are more effective and efficient than human tellers at detecting and aggregating transactions over $10,000.

Small Changes in the CTR Threshold Might Significantly Affect Compliance Burden

FinCEN conducted research on reducing CTRs that are not useful to law enforcement in 2004 through the BSA Advisory Group, which consisted of representatives from federal agencies, financial institutions, and other stakeholders.[101] This study included the evaluation of a possible recommendation to increase the CTR reporting threshold.[102] In 2019, FinCEN solicited input on this issue from users of BSA reports during an assessment of the benefits of BSA reporting. Neither effort resulted in changes to the threshold.

Potential Effects of Change to CTR Threshold

Relatively small changes to the CTR threshold would significantly change the number of CTRs filed. Based on our analysis of fiscal year 2023 CTR data, a threshold of $20,000 would have reduced CTR filings by 65 percent (see fig. 11).

Figure 11: The Number of CTRs Filed in Fiscal Year 2023 Would Have Been Significantly Lower If the Reporting Threshold Had Been Raised

aInflation-adjusted amount calculated using Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers for calendar year 2023.

Most bank and credit union representatives we interviewed stated that increasing the CTR threshold would decrease their compliance burden. A relatively modest increase of $5,000 to $20,000 could significantly reduce compliance costs, most bank and credit union representatives said.[103] Conversely, reducing the threshold could significantly increase compliance costs, according to many bank and credit union representatives we interviewed.

Small threshold changes could significantly affect staff costs due to incremental workload such as manual staff review for each CTR filed. Although automated systems are used, manual tasks like data entry, follow-up, and review are still necessary, according to financial institution representatives. These tasks, including pre-filing reviews, research, and collection of customer information, are the most burdensome aspects of CTR compliance, according to bank and credit union representatives.

Even if most CTRs require no staff intervention, significant resources are still devoted to manual review, according to two large bank representatives. Casinos in particular spend significant time manually collecting information from non-member players, sometimes relying on manual surveillance to aggregate transactions and collect identifying information, according to gaming industry representatives. Reviewing and aggregating 1 day’s worth of CTRs usually takes 7 to 12 hours and can take up to 2 days during peak gaming periods, they said.

FinCEN Time and Cost Estimates