WIC INFANT FORMULA

Single-Supplier Competitive Contracts Reduce Program Costs and Modestly Increase Retail Prices

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106503. For more information, contact Kathryn A. Larin at (202) 512-7215 or larink@gao.gov or Michael Hoffman at (202) 512-2700 or hoffmanme@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106503, a report to congressional requesters

Single-Supplier Competitive Contracts Reduce Program Costs and Modestly Increase Retail Prices

Why GAO Did This Study

WIC provided food assistance to more than 6 million low-income pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and young children each month in fiscal year 2023. WIC is administered by USDA and state agencies. For infant formula, state agencies use a competitive bidding system. The manufacturer offering the lowest net price after a rebate to the state becomes that state’s single-supplier of formula for WIC participants. In 2022, a national infant formula shortage raised questions about how this system for WIC affects the infant formula market.

This report examines (1) trends in the price of infant formula and the rebates states receive from manufacturers, (2) how the WIC single-supplier competitive system affects infant formula prices and the formula market, (3) advantages and disadvantages of the current system for WIC and (4) alternatives to the current system.

GAO reviewed 31 studies determined to be methodologically sound and analyzed 2013–2023 retail sales data on infant formula (the most current at the time of analysis). GAO also reviewed 2013–2024 USDA data on states’ WIC contracts. GAO conducted an econometric analysis to assess the effect of winning a WIC contract on retail formula prices, sales, and market share within a state. GAO interviewed federal agency officials and various stakeholders, including researchers; representatives of associations, retailers, and formula manufacturers; and officials from eight states that serve large numbers of WIC infants or that had provided formula to WIC participants outside the retail market.

What GAO Found

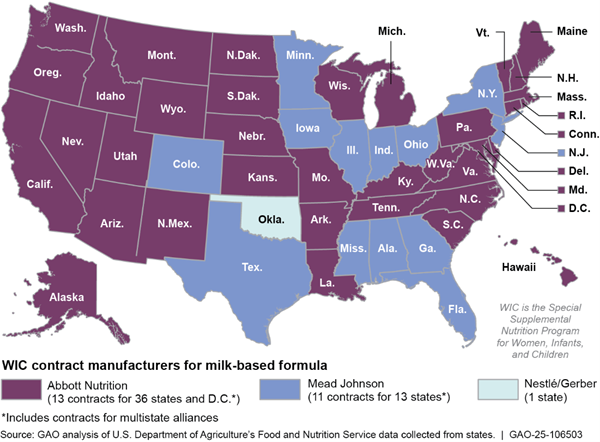

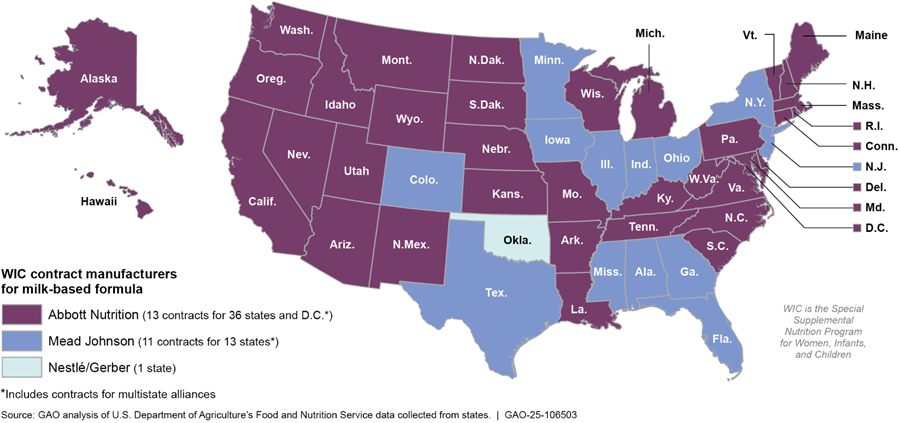

Over half of the country’s infant formula is purchased by state agencies through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Since 1989, federal law has generally required WIC state agencies to use a single-supplier competitive system for infant formula. States solicit bids from formula manufacturers for the lowest net price after accounting for a rebate amount given to the state. The manufacturer with the winning bid is awarded a multi-year contract to provide formula for WIC participants in a state or in a group of states that are part of a contracting alliance. As of August 2024, two manufacturers held almost all of WIC contracts in the United States (see figure).

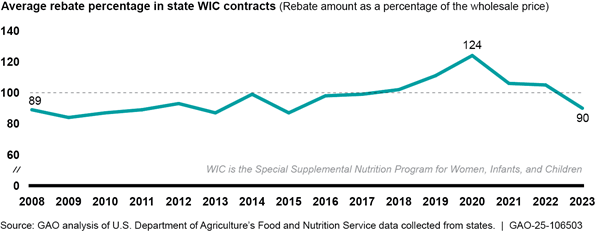

From 2013 to 2023, U.S. infant formula prices were generally stable or decreased, according to GAO’s analysis of retail sales data adjusted for inflation. For instance, the average price of milk-based powder formula—the most commonly purchased formula type—was relatively stable from 2013 to 2020 then fell by 11 percent from 2020 to 2023. During this same period (2020 to 2023), the size of rebates from formula manufacturers to states in newly awarded contracts fell by 27 percent after years of increases, according to GAO’s analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data (see figure). A number of trends were present in the infant formula market at this time, including a decline in the number of formula-fed infants and the temporary removal of tariffs on foreign formula. However, GAO’s analysis was not designed to evaluate the role of these factors in determining national price or rebate trends over time.

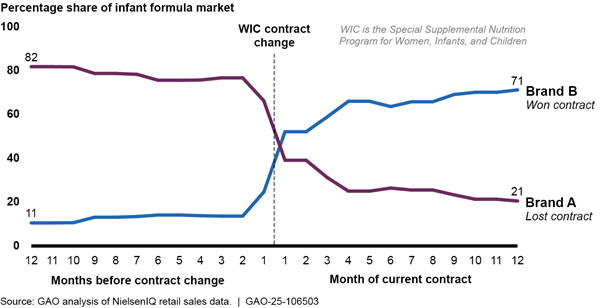

The WIC single-supplier competitive system modestly increased prices for infant formula products of the winning brand, according to GAO’s regression analysis of 2018-2023 infant formula sales data. Winning a WIC contract caused an average price increase of 1.7 percent for the formula products specified in WIC contracts—about 30 cents for a typical 12-ounce container of powder formula. It also caused a 0.3 percent price increase for other formula products of the same brand. Winning a contract also greatly increased the winning brand’s overall market share in a state (see figure).

The key advantage of the current system is that rebate savings allow states to serve more eligible participants. About one-fifth of WIC participants were served monthly with $1.6 billion in rebate savings in 2023, according to USDA estimates. Disadvantages include limited choice for WIC participants and increased retail prices, which adversely affect non-WIC consumers. The reliance on a single-supplier can also leave states vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, which Congress and USDA took steps to mitigate. For example, USDA implemented provisions of the Access to Baby Formula Act of 2022 that require WIC state agencies to prepare plans in case of any future supply chain disruptions.

Alternative approaches identified in research and stakeholder interviews could address some disadvantages of the current system but would be unlikely to result in the same level of cost savings compared to the current system. For example, states could contract with more than one manufacturer to provide WIC participants additional choices and mitigate potential supply disruptions. However, state agencies could face additional administrative burdens in managing multiple contracts, and manufacturers would likely reduce the size of their rebates to states without the guarantee of an exclusive contract.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

BLS Bureau of Labor Statistics

CPI Consumer Price Index

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FNS Food and Nutrition Service

FTC Federal Trade Commission

ERS Economic Research Service

EBT electronic benefits transfer

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

OIG Office of Inspector General

USDA U. S. Department of Agriculture

UPC Universal Product Code

WIC Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

January 14, 2025

Congressional Requesters

About 40 percent of infants in the United States received food assistance through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in fiscal year 2023, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). WIC provides supplemental food, including infant formula, at no cost to low-income pregnant, post-partum, or breastfeeding mothers, and to infants and young children. The program is administered by USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) and WIC state agencies.[1] WIC served about 6.6 million participants each month in fiscal year 2023. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024 provided just over $7 billion for WIC.[2]

Since 1989, federal law has generally required WIC state agencies to use a single-supplier competitive system with infant formula manufacturers to obtain rebates on formula purchased through the program.[3] Under this system, WIC state agencies typically use a competitive bidding process in which the manufacturer offering the lowest net price is awarded an exclusive multi-year contract to provide infant formula to the state’s WIC participants.[4] The net price is determined by the manufacturer’s wholesale price minus a rebate amount offered by the manufacturer to the state. The rebate savings from infant formula, which totaled about $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2023, offset other WIC food costs and enable the program to serve more eligible participants.

A national shortage of infant formula associated with the closure of a critical manufacturing plant in 2022 and exacerbated by existing COVID-19 supply chain challenges resulted in a federal response. For example, FNS temporarily waived certain restrictions on the type of infant formula WIC participants could purchase with WIC benefits. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also temporarily allowed, on a case-by-case basis, certain foreign manufacturers to sell their formula in the United States without meeting all of FDA’s requirements. The share of formula in the United States that is consumed by WIC infants ages 0 to 12 months is estimated to have been about 56 percent in 2018, according to research by USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS).[5] Accordingly, in the wake of the nationwide shortage, news reports and policymakers questioned how the WIC contract system affects the infant formula market.

You asked us to review WIC’s competitive single-supplier contract system for infant formula. This report examines (1) infant formula price and rebate trends, (2) how WIC contracts affect infant formula prices and the formula market, (3) advantages and disadvantages of the current single-supplier competitive system for WIC infant formula, and (4) advantages and disadvantages of potential alternatives to the current system.

To identify trends in infant formula prices and rebate amounts, we analyzed retail sales and rebate data and reviewed prior research. Specifically, we analyzed nationally representative data from NielsenIQ, a consumer information company, on the national average retail prices paid for 98 infant formula products over the last 10 years from July 13, 2013, through August 12, 2023.[6] Our analysis focused on infant formula products listed in WIC contract data provided by FNS as well as similar products that were not listed in WIC contracts but were under the same brands.[7] We focused on products by formula manufacturers with WIC contracts and did not include products whose manufacturers do not have WIC contracts. Over this period, the selected products accounted for about 64 percent of total infant formula sales.

We also analyzed data from FNS on rebate amounts and wholesale infant formula prices from WIC contracts that state agencies report to FNS. These data include information for contracts that were in effect at any time during the period from fiscal year 2013 through August 2024, though these contracts may have start or end dates beyond that time frame. We also identified and reviewed findings from 31 studies published from 1989 through 2023 that we identified through a literature search.[8] We selected these studies because they directly related to our research objectives, contained original research, and included clear descriptions of the study’s methodology.[9]

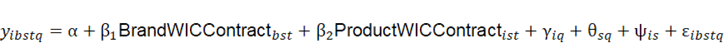

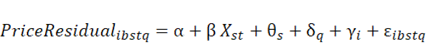

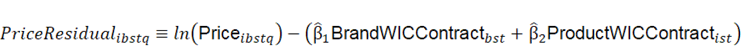

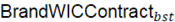

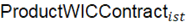

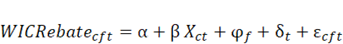

To determine how WIC contracts affect infant formula retail prices and the formula market, we used regression analysis to assess the relationship between winning a WIC contract and retail formula prices, sales, and market share within a state, controlling for other factors. For this analysis, we used state-level, quarterly sales data from NielsenIQ for 78 selected milk-based formula products from the last 5 years (October 2018 to September 2023).[10] This analysis included data collected from participating retailers in 30 states for which NielsenIQ could provide state-level estimates.[11] Accordingly, these data do not reflect infant formula sales or WIC contracts nationwide.

Our econometric analysis is not intended to measure the effect of the WIC program as a whole on infant formula prices and does not measure all possible effects the WIC contracting system might have on the competitive environment in the infant formula market. That is, our approach estimates price differentials between WIC primary contract products and non-WIC products that result from winning the WIC contract in a state or alliance under the existing regulatory environment. We view these price differentials as indicative of one of the effects of single supplier competitive contracts on the infant formula market, but effects may differ under alternative WIC contracting systems.

We assessed the reliability of the NielsenIQ and FNS data by reviewing technical documentation, interviewing NielsenIQ representatives and FNS officials, and testing data fields for missing values, outliers, and obvious errors. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for analyzing trends and the effects of WIC contracts on the infant formula market. See appendix I for more information about the data analyses we conducted to address our first two research objectives, including model specification, robustness checks, and limitations.

To identify the advantages and disadvantages of the current system and of potential alternatives to the system, we used several methods. We interviewed federal officials from FNS and ERS as well as WIC officials from eight states.[12] We selected these states because they led the largest state alliances (i.e., multiple states collectively soliciting competitive bids for infant formula), served the most WIC infants, or had historically used other ways to provide formula to WIC participants outside of the retail market.[13] Altogether, the selected states and other states in their state alliances represent 28 states in WIC infant formula contract negotiations and served 51 percent of WIC infants in fiscal year 2021. We conducted 11 interviews with various stakeholders we selected to obtain a broad range of perspectives including researchers and representatives from associations, infant formula manufacturers, and research/advocacy organizations.[14] We also interviewed two retailers that represented over 500 stores located in 11 states. The information collected through our interviews is not generalizable. We also reviewed relevant federal laws and regulations, agency guidance, and policy proposals discussed in our interviews.

Additionally, we drew on relevant findings from our data analysis and reviewed relevant government reports as they pertained to advantages and disadvantages of the current system. We also reviewed policy proposals identified in our interviews and, as part of our literature review, reviewed five prior studies or reports that included information about advantages and disadvantages of alternatives to the single-supplier competitive system. The potential alternatives we identified as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative are based on findings from prior research and testimonial evidence from our interviews.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

WIC Single-Supplier Competitive System

WIC Infant Formula Contracts

Under the single-supplier competitive system, a WIC state agency publicly solicits sealed bids from infant formula manufacturers to supply discounted infant formula to the state’s WIC participants.[15] States require bidders to specify a rebate for milk- and soy-based formula and for each of the physical forms of infant formulas, which include:

· powder, which must be mixed with water before feeding;

· liquid concentrate, which must be mixed with an equal amount of water before feeding; and

· ready-to-feed, which requires no mixing.

The manufacturer offering the lowest net price—determined by the manufacturer’s wholesale price minus its rebate to the state—wins a multi-year contract and becomes the primary supplier of WIC infant formula in the state. The length of the contracts ranged from 2 to 6 years with an average length of 4.7 years, according to our analysis of FNS contract data.[16] The winning manufacturer provides a per unit rebate on specific infant formula products listed in the contract. States receive the rebates based on the amount of infant formula purchased by the state’s WIC participants at retail stores. Each contract is between the WIC state agency or state alliance and the manufacturer and is subject to state-specific procurement laws, policies, and processes. FNS is not a party in the contract, but it provides WIC state agencies with technical assistance to help ensure that states have federally compliant, timely, and competitive bid solicitations.

The brand of infant formula provided by WIC varies by state and depends on which manufacturer holds the contract for that state. As of August 2024, three manufacturers—Abbott Nutrition, Mead Johnson, and Nestlé/Gerber—had contracts with WIC state agencies to provide infant formula for the WIC program, though Nestlé/Gerber was transitioning out of WIC contracting after selling its infant formula business to Perrigo in 2022. For contracts in effect as of August 2024, Abbott Nutrition provided milk-based formula to WIC participants in 36 states and the District of Columbia, Mead Johnson in 13 states, and Nestlé/Gerber in one state (see fig. 1). According to our analysis of FNS participant data, about 52 percent of WIC infants who were formula-fed (either partially or fully) lived in states with Abbott contracts, 47 percent of WIC infants who were formula-fed lived in states in states with Mead Johnson contracts, and 1 percent lived in the state with a Nestlé/Gerber contract.

Notes: This figure does not show the contract manufacturer for contracts that may be held by U.S. territories and tribal organizations.

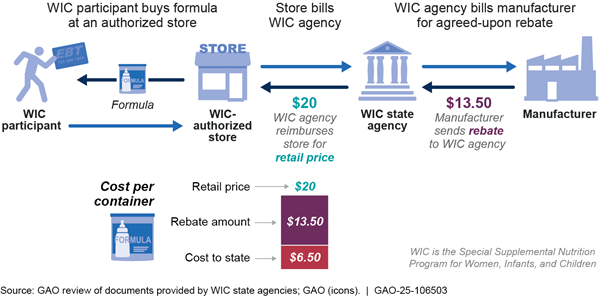

WIC Infant Formula Rebate Reimbursement Process

To receive infant formula rebates, WIC state agencies follow a specific reimbursement process, based on purchases of contract products by WIC participants. First, WIC participants use an electronic benefits transfer (EBT) card to obtain specified infant formula products at no cost to the participant at a WIC-authorized store.[17] Second, the store bills the WIC state agency for the retail price of the formula purchased and the state reimburses the store for this.[18] Third, the state invoices the contracted formula manufacturer to obtain a rebate for each container of its formula WIC participants obtained with WIC benefits. The rebate amount per container is the discount on the manufacturer’s wholesale price that was set during the competitive bidding process and agreed to in the contract.[19] Accordingly, the actual cost of infant formula to the WIC program is the difference between the retail price and the rebate amount. See fig. 2 for an example of this process with the retail price, wholesale price, and rebate percentage provided for illustration.

Note: EBT is an abbreviation for electronic benefits transfer. This example depicts the rebate provided for a 12.4-ounce container of milk-based powder formula. The sample retail price, wholesale price, and rebate amount are provided as an illustration.

With some exceptions, state agencies must provide WIC participants with the infant formula products specified in the rebate contract with the manufacturer. Federal regulations allow WIC participants with infants who have special medical or dietary conditions to be issued a different type of formula if they obtain medical documentation. Rebates are not provided for noncontract brands of formula that a medical professional has prescribed to an infant due to a health condition.[20]

2022 National Infant Formula Shortage

A combination of factors caused a national shortage of infant formula in 2022. In February of that year, Abbott Nutrition voluntarily shut down an infant formula production facility for about 4 months following an infant formula contamination and product recall after the FDA found that the plant was contaminated with harmful bacteria. Around the same time, multiple infants were hospitalized and at least two died from an illness caused by the same type of bacteria found in the plant. The shutdown of the Abbott Nutrition facility exacerbated pre-existing disruptions in the food supply chain due in part to the pandemic, which also contributed to shortages of infant formula.[21] More than one-third of parents with infants were affected by the shortage, including many families who obtained formula using WIC, according to estimates from a U.S. Census Bureau survey.[22] The shortage resulted in a wide-range of federal government responses and subsequent federal investigations (see examples in text box).

|

Federal Actions in Response to the 2022 Infant Formula Shortage Outside of efforts to help families participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) obtain formula, various federal entities took action during and following the shortage. For example in 2022, · The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) used its enforcement discretion to allow some manufacturers on a case-by-case basis to import infant formula. · Congress passed laws temporarily suspending tariffs on imports of infant formula and formula ingredients. |

· Congress passed the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022, which among other things, set forth new requirements related to disruptions, recalls and shortages. It also established infant formula as a ‘critical food’ and required FDA to establish an office of critical foods. Subsequent reports and investigations were also released in the years following the shortage. For example, · In March 2023, the FDA released a national strategy to increase the resiliency of the U.S. infant formula market. It described actions the FDA planned to take to protect against future contamination and other potential causes of shortages. · In June 2024, the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) released a report on its investigation of FDA’s actions leading up to the recall. The OIG found that FDA lacked or had inadequate policies and procedures to identify risks to infant formula and respond effectively through its complaint, inspection, and recall processes. The OIG made nine recommendations to address these findings. |

|

Source: GAO summary of information from FDA National Strategy, HHS OIG report, and relevant federal laws; Spiroview Inc./ stock.adobe.com (photo). | GAO-25-106503 |

|

To help address the effect of the shortage on WIC participants, FNS offered state agencies temporary waivers of program rules to help participants obtain infant formula, among other actions. The waivers allowed WIC participants to obtain alternate sizes, forms, or brands of infant formula during the shortage. For example, one of the waivers allowed WIC participants to purchase noncontract brands of formula without medical documentation.[23] Another waiver allowed state agencies to permit WIC participants to obtain certain imported formulas approved by the FDA.[24]

In May 2022, the Access to Baby Formula Act of 2022 was enacted, which gave USDA permanent authority to respond to infant formula shortages and recalls that affect the WIC program.[25] Specifically, USDA can modify or waive certain WIC statutory or regulatory requirements during disasters, emergencies, or supply chain disruptions that impact the program. The act also requires that all new WIC state infant formula rebate contracts include remedies to enable WIC participants to obtain formula in the event of an infant formula recall.

Infant Formula Prices and Manufacturers’ Rebates to State Agencies Declined in Recent Years

Inflation-Adjusted Prices for Formula Were Generally Stable or Fell during the Last Decade

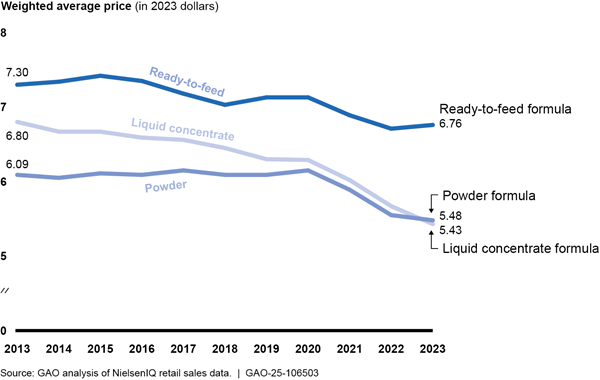

After adjusting for inflation, average infant formula prices in the United States were generally stable or fell from 2013 through 2023, according to our analysis of annual NielsenIQ retail sales data (see fig. 3).[26] The average price of milk-based powder formula—the most commonly purchased formula—was relatively stable from 2013 to 2020 and then fell by 11 percent, from $6.15 per 26 reconstituted ounces in 2020 to $5.48 in 2023.[27] While the average prices of milk-based liquid concentrate and ready-to-feed infant formula were generally higher than prices of powder formula, they followed a similar trend over time.[28]

Figure 3: Average Retail Price for Milk-Based Infant Formula Products by Type in 2023 Dollars (adjusted for inflation), 2013–2023

Notes: Reported amounts are adjusted to 2023 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for all items. The price represents the weighted average inflation-adjusted retail price per 26 reconstituted fluid ounces of formula, where retail price is weighted by units sold.

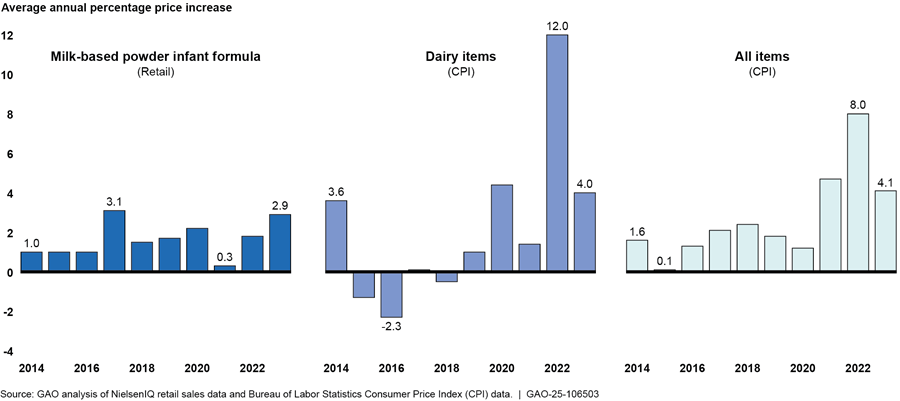

Milk-based powder formula prices generally kept pace with inflation from 2014 through 2020 but grew more slowly than inflation, which increased rapidly in 2021 and 2022 (see fig. 4). For example, our analysis of data from NielsenIQ and the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the average price for milk-based powder formula increased at a rate of 2 percent in 2022, which was lower than the overall inflation rate (8 percent) and the inflation rate for of dairy products (12 percent).

Figure 4: Average Annual Percentage Price Increase for Milk-Based Powder Infant Formula (not adjusted for inflation), All CPI Dairy Items, and All CPI Goods, 2014–2023

Notes: The Consumer Price Index (CPI) for all items is a common measure of inflation and is used to measure the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket—or standard group of items—of consumer goods and services. The CPI for dairy items includes the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for dairy products, such as milk, cheese, yogurt, and ice cream.

According to our analysis, factors that may affect retail prices for infant formula include overall demand for formula and the size of the WIC program in a state—in addition to the WIC single-supplier competitive system, which we describe in detail in the next section. Our analysis of state-level data from 2018 to 2023 found that as the number of formula-fed infants fell over time (regardless of whether their formula was purchased through WIC), average inflation-adjusted retail prices of infant formula also fell.[29] Similarly, prior research from USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) found that an increase in a state’s percentage of formula-fed infants who were served by WIC was associated with an increase in the retail price of formula across brands (those with the WIC contract and those without).[30] Additionally, steps taken by the federal government to alleviate the 2022 shortage by expanding supply, such as through reducing tariff and regulatory barriers to imports, could have also affected prices, although we were not able to account directly for these factors in our analysis.

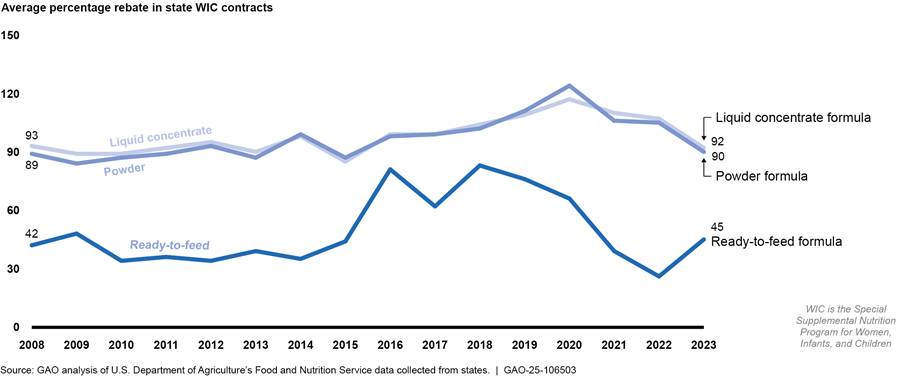

Manufacturers’ Rebates to States for WIC Infant Formula Declined in Recent Years After Several Years of Increases, Affecting Program Costs

The size of manufacturers’ rebates on milk-based formula purchased through WIC generally decreased in recent years following several years of increases, according to our analysis of FNS’s data on state contracts. For contracts initiated from 2008 to 2020, the rebate percentage that state WIC agencies received from manufacturers for milk-based powder formula generally increased. The rebate percentage peaked in 2020 at 124 percent of the manufacturer’s wholesale price and then declined to 90 percent in 2023 (see fig. 5).[31] Average rebate percentages for liquid concentrate formula followed a similar trend. For ready-to-feed formula, which is the most expensive type and the least commonly purchased, the average rebate percentage fluctuated over this period from a high of 83 percent in 2018 to a low of 26 percent in 2022. Although not shown in the figure, as of August 5, 2024, two states initiated new contracts in 2024, which also had lower average rebate percentages than prior years.

Figure 5: Average Manufacturers’ Rebate Percentage in State WIC Contracts by Milk-Based Infant Formula Type and Contract Initiation Year, 2008–2023

Notes: The rebate percentage represents the rebate as a share of the contract manufacturer’s wholesale price of formula, as set through a competitive bidding process and specified in the infant formula contract between the manufacturer and the WIC state agency or state alliance. This figure shows the average rebate percentage by contract initiation year and by the type of formula for contracts that were in effect from 2013 to 2023, which include some contracts with start dates as early as 2008. Because this figure presents the average rebate percentage at the contract level, the average rebate percentage is calculated using a different composition of state or alliance contracts in different contract initiation years. This figure excludes tribal organizations and U.S. territories that are not part of a state alliance.

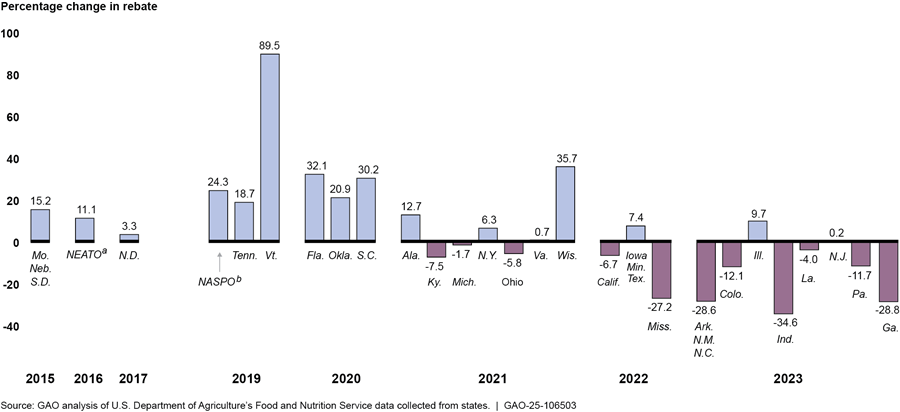

We found similar trends when examining how the size of manufacturers’ rebates have changed over time for a single state or state alliance. Compared to their previous contracts, WIC state agencies received higher rebate percentages from manufacturers on milk-based powder formula for contracts initiated between 2015 and 2020, according to our analysis of contract data.[32] However, state agencies generally received a lower rebate percentage for contracts they initiated in more recent years. Specifically, eight of the 11 states or alliances that initiated a new contract in 2022 or 2023 received a lower rebate percentage for milk-based powder formula than in their previous contract (see fig. 6).[33]

Figure 6: Change in the Rebate Percentage between the Current and Previous WIC Contracts for Milk-Based Powder Formula by State or Alliance, 2015–2023

Notes: WIC is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. The rebate percentage is the discount on the contract manufacturer’s wholesale price of formula, as set through a competitive bidding process and specified in the infant formula contract between the manufacturer and the WIC state agency or state alliance. This figure shows the percentage change between the milk-based powder rebate percentage of the current contract and the previous contract in the year the current contract was initiated for contracts that were in effect from 2013 to 2023. This figure excludes tribal organizations and U.S. territories that are not part of a state alliance.

aNEATO is the New England and Tribal Organization. In 2016, this alliance included Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Vermont joined NEATO in 2021.

bNASPO is the National Association of State Procurement Officials. This alliance includes Alaska, American Samoa, Arizona, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Delaware, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Virgin Islands, Washington, Washington DC, West Virginia, Wyoming, the Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona, Inter-Tribal Council of Nevada, Osage Nation, Pueblo of Isleta, and the Navajo Nation.

A variety of factors may affect the size of rebates manufacturers offer to states, according to our data analysis, prior research, and representatives from one formula manufacturer we interviewed. Our analysis of data from 2013 to 2023 found that the number of formula-fed infants in a state or alliance was positively correlated with WIC infant formula rebate amounts.[34] Specifically, as the number of infants who used formula (WIC or non-WIC) decreased over time, manufacturers offered lower rebates. An ERS study found a similar relationship between a state’s WIC infant population and rebates. This study found that a greater number of infants served by WIC was associated with lower net price bids.[35] Representatives from one formula manufacturer we interviewed said they determine the size of the proposed rebate in their bid based on the size of the contract, including the number of infants served in the state or alliance, as well other factors, such as the company’s budget and business strategy.

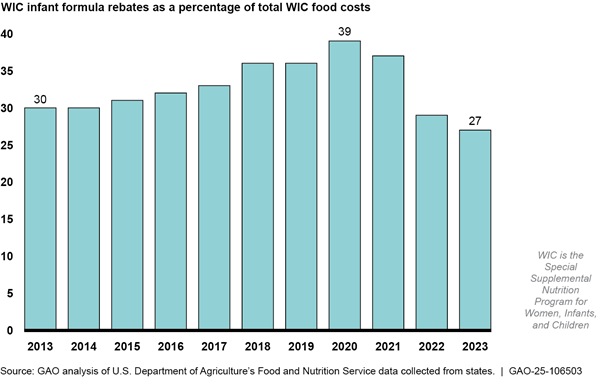

Infant formula rebates have covered a lower share of WIC food costs in recent years from a high of 39 percent in 2020 to a low of 27 percent in 2023 (see fig. 7). According to ERS, states spent more on WIC foods starting in fiscal year 2022 due, in part, to the increased costs associated with disruptions to the infant formula supply chain that year and the increased fruit and vegetable cash value benefit to WIC participants as a result of federal law in 2021.[36]

USDA monitors trends in infant formula rebates and WIC food costs, both of which have implications for overall WIC program costs. Specifically, FNS officials told us they review changes to state infant formula contracts when a new contract is awarded. If FNS anticipates these changes will affect the amount of funding needed to serve the state’s projected caseload, it will adjust future food costs in its budget estimate. In its fiscal year 2025 budget justification, FNS requested additional funding for WIC, in part to offset expected reductions in infant formula rebates.

In addition to considering contract changes as part of budget planning, USDA’s ERS has a related study underway that will look at trends in state agencies’ infant formula rebate contracts. The purpose of the study is to summarize recent trends in state agencies’ infant formula rebate contracts and examine how factors such as declines in the number of infants participating in WIC contribute to these trends. ERS officials said they expect to publish the study on ERS’s website some time in 2025.

WIC’s Single-Supplier Competitive Contracts Caused Modest Infant Formula Price Increases and Large Market Share Increases for the Winning Brand

WIC’s Single-Supplier Contracts Caused Modest Increases in Retail Prices for WIC Contract Products and Other Products under the Same Brand

Our analysis of quarterly state-level retail sales data from 2018 to 2023 found that winning a WIC contract caused modest increases in retail prices for products specified in WIC contracts and other products under the same brand.[37] Formula manufacturers have a variety of products under a single brand. However, certain products are specified in the state’s WIC contract as the primary infant formula that will be provided to WIC participants.[38] Winning a WIC contract caused a 1.7 percent increase in the average retail price of the products included in the WIC contract—about 30 cents for a typical 12-ounce container of milk-based powder formula, based on our main regression model.[39] Winning a WIC contract also caused a 0.3 percent increase in the price of other formula products under the same brand that were not included in the WIC contract.[40]

Our findings are consistent with earlier studies that found that the WIC single-supplier competitive system modestly increased the retail price of infant formula. In one study, researchers reviewed retail prices of infant formula products and FNS contract data from 2007 to 2013. They found that the prices of the formula products of the winning brand increased by more than 5 cents per ounce, which was more than the price increases among other brands’ products.[41] In an older 2004 study, ERS analyzed retail price data from 1994 through 2000 and found that the WIC single-supplier competitive system resulted in modest increases in a non-WIC family’s monthly expenditures on milk-based formula due to increased prices.[42]

Retailers likely raise the price of the WIC primary contract product because of the increased demand for the new product. In particular, retailers are likely to increase prices because WIC participants are insensitive to price changes, given that they obtain formula at no cost using WIC benefits.[43] To ensure that payments to retailers reflect competitive retail prices, state agencies must establish allowable reimbursement levels for retailers.[44] For other formula products under the same brand, retailers likely increase prices due to the increase in demand (discussed below). However, price increases for these products are likely smaller because non-WIC consumers who pay for formula are more sensitive to price changes.[45]

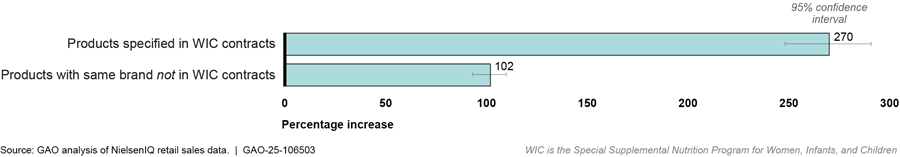

Winning a WIC Single-Supplier Contract Caused a Large Increase in the Contract Brand’s Sales and Market Share within a State

According to our analysis of state level retail sales data from 2018 to 2023, winning a WIC contract caused large increases in monthly dollar sales of the products specified in the WIC contract as well as other formula products under the same brand. On average, we estimated that the monthly dollar sales of products specified in the WIC contracts roughly tripled and products with the same brand roughly doubled after winning a state WIC contract (see fig. 8).[46] Some of this increase in dollar sales was due to the modest increase in retail prices described above, but the majority was due to a large increase in units sold after winning a WIC contract, as shown in the figure.[47]

Figure 8: Estimated Percent Increase in Infant Formula Products’ Monthly Dollar Sales for a Brand Winning a State WIC Infant Formula Contract, 2018 to 2023

Notes: The data were collected from about 90 participating retail chains and included 78 distinct milk-based formula products sold in 30 states and do not reflect infant formula sales nationwide. We express our confidence in the precision of our sample’s results at the 95 percent confidence level.

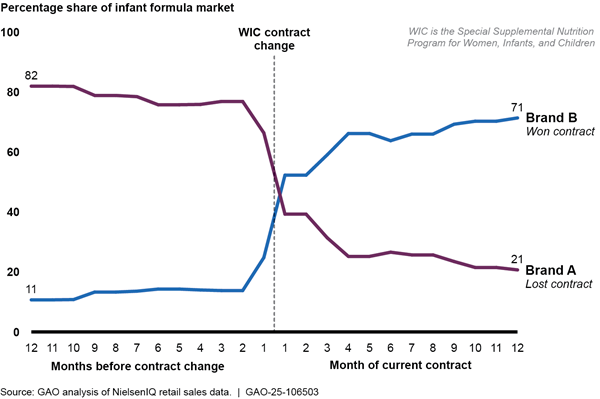

Winning a WIC contract also caused a substantial increase in the overall market share of the winning brand within a state, according to our regression analysis (see fig. 9).[48] Specifically, we estimated that winning a WIC contract caused a brand’s market share—the brand’s percentage of total infant formula sales in a state—to increase 58 percentage points on average.[49]

Figure 9: Estimated Average Infant Formula Brands’ Market Share of Selected Products Before and After a New State WIC Infant Formula Contract is Initiated, 2018 to 2023

Note: The month a new contract started was designated as month 1 (indicated by the dashed line), and the other months are numbered sequentially from that point. Market share is calculated using only the products included in our sample, and therefore excludes products by brands that do not have WIC contracts. Therefore, the market share calculation reflects a subset of the overall infant formula market.

Our findings are consistent with earlier studies that found that winning a WIC contract resulted in large-volume sales of products under the winning brand. For example, one study examining sales and WIC contract data from 2006 to 2015 found that 1 year after a WIC contract change, sales of infant formula products increased 322 percent for the new contract brand and decreased 77 percent for the former brand.[50] Similarly, a 2011 ERS study examining 2004 to 2009 sales and contract data found that after winning a WIC contract, the winning brand’s market share increased by an average 74 percentage points.[51]

|

WIC Contract Spillover Effects Infant formula manufacturers competitively bid to win contracts to provide infant formula for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) for states. In addition to purchases from WIC-consumers, the winning brand typically experiences increased sales by non-WIC consumers, known as spillover effects. Prior research has reported that spillover effects can occur for various reasons: · Retailers may devote more shelf space and better product placement to the brand under the WIC contract because WIC consumers make up a large portion of the infant formula market. This results in increased product visibility by non-WIC consumers. · Physicians or hospitals may recommend the WIC contract brand to all formula-feeding patients to avoid having to differentiate between those enrolled in WIC and those not. · WIC shelf tags may cause non-WIC consumers to perceive a food item as having the government’s endorsement. · WIC participants who are satisfied with the formula under WIC contract may continue with the same product if they leave WIC. They may also recommend the brand to others who are not enrolled in WIC. Source: Published studies by USDA’s Economic Research Service and others. | GAO‑25‑106503 |

Although some of this increase is due to WIC consumer purchases, some is due to a “spillover effect” in which non-WIC consumers also purchase products of the brand under WIC contract. Given that non-WIC infants account for about 44 percent of infant formula sales in the United States, we estimate that up to 44 percent of the increase in dollar sales and quantity sold of the infant formula specified in WIC contracts was due to non-WIC participants shifting their purchases to the product specified in the new WIC contract.[52] Almost all of the increase in sales for other products under the same brand is also likely due to this spillover effect.[53]

Prior research reported similar findings on spillover effects. In its 2011 study, ERS found that while most of the market share increase that occurred after winning a contract was directly due to WIC recipients switching to the products in the WIC contract, the winning brand also realized a spillover effect, in which non-WIC formula sales also increased.[54] ERS and other researchers have noted that these spillover effects help explain why infant formula manufacturers compete for contracts and have historically offered large rebates to win them. For example, a 2023 study found that the winning manufacturer was compensated for the loss experienced from providing a large rebate in WIC markets by a gain in non-WIC markets due to spillover effects.[55]

WIC’s Single-Supplier Competitive System Provides Substantial Cost Savings for WIC but Also Has Disadvantages

USDA Estimates More Than 1 Million WIC Participants Are Served Each Month Due to Rebate Savings from WIC Infant Formula Contracts

Rebate savings from WIC’s single-supplier competitive system have allowed states to serve more eligible participants, according to USDA estimates and other sources. For fiscal year 2023, rebate savings from the single-supplier contracts for infant formula totaled $1.6 billion and funded benefits for an average 1.3 million participants each month or 19.3 percent of the monthly caseload.[56] WIC state agency officials and other stakeholders we interviewed said that the cost savings from these rebates and the program’s ability to serve additional participants was a key benefit of the current system. Officials said they were unsure if an alternative system could provide similar savings, while serving the same number of participants.

These savings have long been an advantage of the current system, as noted in previous GAO and USDA reports. For example, in 2006, we reported that savings from infant formula rebates were an important source of funding for WIC, allowing the program to serve additional participants each year.[57] Before the single-supplier competitive system, infant formula accounted for nearly 40 percent of total WIC food costs and infant formula retail prices were rising more quickly than prices for other foods, according to a 2001 ERS report.[58] Similarly, a more recent study from FNS found that without infant formula rebates, the average estimated food package cost for WIC infants in fiscal year 2018 would have been about $94 more per month.[59]

States Cited Administrative Burden and Limited Choice as Disadvantages to WIC Agencies and Participants, While Higher Prices Affect Non-WIC Customers

Administrative Burden

WIC officials we interviewed from seven states said they dedicate substantial time and resources to overseeing WIC infant formula contracts. Officials estimated that it can take 1 to 2 years to complete the process given the multiple steps involved. These steps may include gathering state-specific data to include in the bid solicitation, drafting and publishing the bid solicitation, answering questions from manufacturers, reviewing manufacturer bid submissions, and awarding the contract. Officials from three states also told us that their agencies have spent an increasing amount of time responding to legal protests from manufacturers who did not receive the contract, challenging the award of the contract.

The transition from one brand to another when the WIC contract is awarded to a new manufacturer can be particularly burdensome, according to WIC state agency officials and retailers we interviewed. FNS contract data show that between July 2013 and August 2024, contract transitions occurred 20 times for 17 states or state alliances. WIC state agency officials noted that these transitions require updates to IT systems and informational materials, such as for WIC participants, healthcare providers, and retailers—all of which can be resource-intensive. Similarly, representatives from two retail companies said that a new WIC contract brand required stores to quickly manage inventory changes, shelf space, and store displays. FNS guidance recommends that state agencies plan well in advance of contract changes and alert WIC retailers of changes to allow ample time to order an adequate supply of the new contract brand of infant formula.[60]

Officials from two states said that state alliances lessened the administrative burden to some degree or that the contracting process was not significantly burdensome.[61] One official whose state was part of an alliance said that alliance membership reduced the administrative burden across member states since one state leads the procurement process on behalf of others. The administrative burden, however, is heavier for the lead state. As of August 2024, 31 states were part of six state alliances.[62] Officials from another state that was not part of a state alliance told us that the WIC contracting process was built into their overall workload and was not significantly burdensome.

Limited Choice for WIC Participants

WIC participants generally receive benefits for specific products of formula within the brand included in the rebate contract.[63] According to officials from three states, some participants can grow frustrated with the limited choice of formula offered. They noted that participants may perceive the WIC-authorized products as inferior when compared to other non-contract formula products that are newer or marketed as higher quality. As a result, these state officials said WIC staff spend considerable time with participants dispelling such perceptions. In addition, state rules that set maximum allowable reimbursement levels and other regulations on WIC-authorized stores decrease the incentive to become a WIC vendor, which could make formula less available for WIC participants. A 2011 ERS study also noted that non-WIC consumers may sometimes have fewer choices of formula under the single-supplier competitive system.[64] Given that WIC-authorized stores may be required by state agencies to maintain a minimum stock of formula products from their WIC contract, some retailers—especially smaller stores with limited shelf space—may decide to stock only WIC products.[65]

Higher Infant Formula Prices

As discussed earlier, the current single-supplier competitive system has caused modest price increases for infant formula products specified in WIC contracts and for other products under the same brand. These price increases affect non-WIC consumers—some of whom may have low-incomes. As we noted, some portion of increased product sales of the brand with the WIC contract can be attributed to non-WIC consumers. Non-WIC consumers may include those who are eligible for WIC but do not participate in the program. Based on the most recent available information, an FNS-funded study estimated that WIC served an estimated 78 percent of infants eligible for the program in 2022 and therefore about 22 percent of infants who were eligible for WIC did not receive WIC benefits.[66] Higher prices would also affect non-WIC households who have incomes that are above the WIC annual income limit, which is at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level. This equates to a gross income of at or below $57,720 for a family of four.[67]

WIC’s Single-Supplier Competitive System Leaves States Vulnerable to Supply Chain Disruptions, and May Hinder Other Manufacturers from Gaining Market Share

States’ reliance on a single supplier for WIC infant formula leaves them more vulnerable to supply chain disruptions. Specifically, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reported in March 2024 that because state WIC programs depend on a single manufacturer for most of their infant formula, single-supplier contracts can make it more likely that a lone contaminant outbreak could lead to serious supply disruptions in the future.[68] The FTC also noted that each state’s reliance on a single manufacturer for WIC infant formula can create challenges in their accessing alternate supply of formula from other manufacturers when disruptions occur. For instance, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers may need to modify existing supply chains, such as through new agreements, before an alternate infant formula supply can actually enter the state.[69]

Similarly, in a July 2024, a committee convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) stated that WIC’s single-supplier competitive system strongly influences the concentration of sales at the state level to the brand with the WIC contract.[70] Accordingly, if there is a supply disruption affecting the brand with the WIC contract, the effects in those states are greater because other brands’ products are less widely available immediately.

Stakeholders we interviewed also said that the WIC single-supplier competitive system made it more difficult to access formula during the 2022 shortage. For example, officials from three states told us that it was difficult for stores to get the needed non-contract formulas in a timely manner during the shortage because distribution chains were set up to support single-supplier contracting for WIC. Representatives from two retailers said that small independent retailers that specialize in serving WIC participants had trouble finding non-contract brands of formula to sell during the shortage because they did not have existing relationships with other distributors.[71] Officials from one state and representatives from a retailer association representing small independent stores also told us that formula distributors prioritized larger stores during the shortage. See the textbox to read about the experiences of some WIC-authorized retailers during the infant formula shortage.

Examples of Challenges WIC-Authorized Retailers Faced During the 2022 Infant Formula Shortage

During the 2022 infant formula shortage, authorized retailers for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) struggled to meet state program requirements to keep certain minimum amounts of WIC foods in stock and had difficulty accessing non-contract and imported infant formula, according to two retailer representatives we interviewed. In one state, some retailers that primarily sold WIC products were concerned with the financial risk of buying non-contract formula during the shortage for fear they would be left with unusable inventory once the shortage ended and normal program operations returned, according to WIC agency officials from that state.

In response to these challenges, USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (1) requested state agencies review and temporarily suspend state policies related to minimum stocking requirements for infant formula, if possible, until the supply of formula had normalized (2) issued memorandums that described the timeline for transitioning back to normal operations, and (3) encouraged WIC state agencies to proactively communicate with retailers and other stakeholders about plans for returning to primarily using the formula products in WIC contracts.

Source: GAO analysis of stakeholder interviews and review of documents from USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service. | GAO‑25‑106503

The FTC and National Academies reports also stated that in addition to state-level vulnerabilities, requirements related to WIC’s single-supplier contracts may make it difficult for smaller companies to bid on WIC contracts overall. To bid on WIC contracts, manufacturers must offer rebates on three physical forms of infant formula (powder, liquid concentrate, and ready-to-feed) and be able to supply formula that WIC agencies issue to participants in an entire state or multiple states in an alliance. According to the FTC, smaller infant formula manufacturers generally lack sufficient scale and could not afford to offer the same rebates as the larger incumbent manufacturers. Accordingly, the FTC concluded that smaller companies are essentially closed off from the market of WIC consumers and any spillover sales.[72] In its report, the National Academies also noted that the requirement to provide three forms of formula may prevent some smaller companies from bidding on WIC contracts.

Representatives we interviewed from one foreign infant formula company cited challenges to entering the U.S. market and competing for WIC contracts. For example, they noted that it was not financially viable for their company to offer competitive rebates in addition to paying the tariff on their products. They also told us that in addition to obtaining FDA certification to sell formula in the U.S. market—which they described as a difficult and lengthy process—infant formula companies must meet additional federal requirements to be able to bid on state WIC infant formula contracts. For example, the nutritional requirements for iron content in WIC infant formula are different than those required by the FDA.[73] WIC provides iron-fortified infant formula to help reduce the risk of iron deficiency anemia.[74] In 2022, FNS sought public comments on these requirements as part of its rulemaking on WIC food packages. The agency ultimately decided to maintain the current iron requirements for WIC infant formula, citing insufficient evidence warranting a change.[75]

Congress and FNS Have Taken Steps to Better Prepare the WIC Program to Respond to Formula Supply Disruptions

Congress and FNS have taken steps to mitigate WIC’s vulnerability to future supply chain disruptions. In December 2023, FNS issued a final rule implementing provisions of the Access to Baby Formula Act of 2022.[76] In addition to implementing provisions that grant FNS permanent authority to waive WIC rules during certain disasters, emergencies, and supply chain disruptions, the rule included other provisions. For example, the rule requires WIC state agencies to develop alternate operating procedures—such as developing a communications plan and coordinating with disaster and public health emergency planning agencies—to support the continuation of WIC services during an emergency.

The rule implemented provisions of the Access to Baby Formula Act of 2022 that required WIC state agencies to include specific remedies in their infant formula contracts with manufacturers they could use in the event of a product recall.[77] At minimum, these remedies must include allowing WIC participants to receive infant formula in sizes that may exceed the maximum monthly allowance and allowing WIC participants without medical documentation to receive formula products not specified in the WIC contract.[78] The remedies must also specify that when a contracted manufacturer is the subject of a recall, the manufacturer must provide the state agency with an action plan that includes supply data and must pay rebates to the state on non-contract brand infant formula.[79] State agencies may include additional remedies beyond these regulatory minimum requirements.[80]

State officials we interviewed expressed support for these remedies, but also had concerns. WIC officials from five states said that the new remedy requirements may help mitigate the effects of future supply chain disruptions. Officials from one state and representatives from one stakeholder organization also expressed concern that these remedies may negatively affect manufacturers’ bids—for instance by increasing costs for manufacturers, resulting in fewer or lower bids. Representatives from one infant formula manufacturer told us that when bidding on WIC contracts, the company considers the risk associated with any required remedies and bids accordingly.

In issuing the final rule, FNS also requested public comments on whether it should modify the requirement that bidders produce liquid concentrate formula—a change that could encourage more infant formula manufactures to consider bidding on WIC contracts. In the rule, FNS noted that states already have the flexibility to provide WIC participants with powder formula or liquid concentrate and that consumers predominantly purchase powder formula. However, FNS also noted that requiring liquid concentrate in WIC could impact some manufacturers’ ability to competitively bid and meet contractual requirements.

FNS officials told us that they will review the public comments and decide whether it should take additional actions related to bidding requirements. Officials we interviewed from two states expressed concern about eliminating the liquid concentrate requirement, noting that in some cases, liquid concentrate may better suited for WIC participants.[81] For example, state officials said liquid concentrate formula may be seen as a safer product compared to powder because it is sterile before opening and may be easier to prepare compared to powder.

Lastly, FNS has taken steps to allow WIC participants to order WIC foods online, which would provide them with additional ways to access infant formula. Data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey showed that some WIC participants shopped online to find infant formula during the 2022 shortage even though they were not able to use their WIC benefits for these purchases.[82] In 2023, FNS proposed changes to WIC regulations to address key regulatory barriers to online shopping in the WIC program, such as the current prohibition of internet-based retailers.[83] Through a grant award, FNS is also funding the development of resource materials for state agencies interested in pursuing online transactions and awarded sub-grants to WIC state agencies to test online ordering and transactions. According to FNS, online shopping would provide WIC participants safer and more reliable options to access infant formula during a program disruption, including a supply chain disruption.

Alternatives Identified by Stakeholders and Relevant Studies Could Address Some Cited Disadvantages of the Current System, but Would Likely Increase Program Costs

Through stakeholder interviews and a review of relevant studies, laws, and regulations, we identified five alternatives to the current single-supplier competitive system for WIC infant formula. While these alternatives could address some disadvantages of the current system, including participant choice and administrative burden for states, they are unlikely to result in the same amount of cost savings and could pose other trade-offs, according to prior research and stakeholders we interviewed (see appendix II for a summary of these alternatives). To implement an alternative cost containment system for WIC infant formula, WIC state agencies must provide FNS with cost estimates, showing that the alternative system would result in savings equal to or greater than a single-supplier competitive system.[84] Except for fixed-price contracts, which we describe in more detail below, the alternatives are conceptual and have not been implemented and studied in real-world settings. As a result, there is very little empirical information on implementation or about how formula manufacturers, WIC participants, or the overall market would respond in these scenarios.

Two Alternative Systems Cited in Current Regulations Could Reduce Some Aspects of Administrative Burden with the Current System but Increase Others

Fixed-Price Contracts with Direct Distribution of Formula

States that distribute WIC foods directly to participants are exempt from the requirements to contain infant formula costs by soliciting manufacturer rebates.[85] Vermont and Mississippi previously purchased discounted formula for direct distribution, using a competitive bidding process to award contracts to the manufacturer with the lowest fixed discounted price. The states then directly distributed the formula to WIC participants, through WIC food centers in Mississippi and home delivery in Vermont. Vermont and Mississippi ended direct distribution of WIC foods when they implemented WIC EBT and began using retail stores for WIC food distribution in 2016 and 2021, respectively.

Advantages of this alternative system include increased state control over inventory and reduced administrative burden on the state to reimburse retailers, according to state officials we interviewed. Mississippi and Vermont state officials said that since the state was responsible for inventory control, it could more easily ensure that WIC products were available to participants. For example, WIC participants could obtain a full month’s supply of formula at a WIC food center and not deplete the center’s supply, according to Mississippi state officials. In addition, state officials told us that the state’s ongoing administration of fixed-price contracts was less complicated because it did not have to reimburse retailers for WIC infant formula purchases.

However, disadvantages of this alternative system could include limited participant access, depending on the type of distribution system; potentially higher administrative costs; and increased formula costs, resulting in lower government cost savings per participant served.

· Participant access. In Mississippi, officials said that participants’ access to WIC foods was more limited under the direct distribution system, which relied on 95 food centers across the state, operating from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Monday through Friday. In contrast, using the retail distribution system, officials said WIC participants have access to 290 retail stores in the state that are open longer hours and have a wider variety of WIC allowable items.

· Administrative costs. USDA officials we interviewed suggested that operating a direct distribution system may be more costly than operating a retail distribution system. For example, a separate food distribution system could require additional operations staff at the state and local levels. Similarly, a direct distribution system that delivered products to participants’ homes would add shipping costs and could involve other logistics, such as the state needing to maintain a separate WIC participant mailing list for distribution purposes.

· Cost savings. Fixed-price contracts may result in higher infant formula costs for states and therefore lower government cost savings for the same population served, according to our analysis of NielsenIQ sales data, state contract information from Mississippi, and interviews with Mississippi state officials.[86] For example, the cost of milk-based powder formula totaled $8.6 million per year under Mississippi’s 2017 fixed-price contract, but we estimated that it would have been about $1 million per year under a rebate contract.[87] Mississippi state officials confirmed that the state had seen lower formula costs since it began using a rebate contract. Manufacturers may offer lower discounts under the fixed-price contract because the winning manufacturer would not receive any spillover sales from the non-WIC market.

FNS Assistance with Bid Solicitation

Under current law and regulations, FNS could solicit bids and select the winning bidder for WIC infant formula contracts on behalf of states if two or more state agencies with retail food delivery systems request FNS to do so.[88] However, no states have made this request, according to FNS officials.

FNS assistance with bid solicitation could reduce some of the administrative burden for states, but state officials we spoke with said they had not considered this option, noting that it would create an additional burden in other areas. For example, to request FNS assistance, WIC state agencies would need to provide FNS with detailed information about their state’s procurement procedures, any required contractual provisions, and historical data on WIC participation and formula purchases. In addition, under this option, FNS would not award or enter into any infant formula cost containment contract on behalf of state agencies, so states would still have administrative costs associated with awarding and managing their contracts.

At the federal level, since use of this option would shift some of the administrative burden to FNS, the agency could face difficulties ensuring that bid solicitations adhere to state-level procurement and other policies. Most of the state officials we interviewed said this option could create additional complications given differences in state-level procurement rules.

Three Other Alternative Systems Could Provide WIC Participants Additional Choices and Might Reduce Prices and Increase Market Resilience, but Would Likely Increase Program Costs

Multi-Supplier Rebate Contracts

Stakeholders we interviewed and prior studies we reviewed identified multi-supplier rebate contracts as another alternative system. With these contracts, the state competitively bids and awards a contract to the manufacturer that offers the lowest net price and to any other bidders within a specified percentage or amount of the best bid. Bills have been introduced that would require states to contract with more than one infant formula manufacturer for WIC following the national infant formula shortage. Specifically, a bill was introduced in July 2022 that would require states to award WIC contracts to at least two manufacturers offering the lowest prices.[89] This bill also stipulated that no manufacturer could receive a contract for more than 70 percent of the formula purchased annually through the state’s WIC program. In May 2023, a separate bill was introduced that would require states to select two manufacturers offering the lowest price.[90]

Multi-supplier contracts could address some of the disadvantages of the current system. Use of these contracts would allow WIC participants to choose from at least one additional brand of formula and may help states more effectively manage disruptions if one manufacturer experiences supply chain issues. However, WIC officials from four states and representatives from three other stakeholder groups we interviewed did not support this alternative system due to concerns about increased administrative burden and reduced rebate savings.[91] Officials from two states said that their agencies would face additional administrative burden due to the complexity of managing multiple contracts. In addition, state officials and other stakeholders we interviewed noted that manufacturers would likely offer lower rebates to states without the guarantee of an exclusive contract. Moreover, with only two manufacturers currently bidding for state WIC contracts, requiring states to contract with multiple manufacturers would guarantee, in the near term, that both companies win contracts, regardless of the size of the rebates offered. Accordingly, manufacturers may have even less incentive to offer sizable rebates, which would increase program costs or result in fewer participants served, without additional funding.

Federally Set Rebate

In one 2023 study, researchers described another potential alternative system in which the federal government would set a predetermined rebate for WIC infant formula.[92] Companies that want to sell formula to WIC participants could voluntarily participate in the rebate program. The researchers used simulated models to compare this national predetermined rebate system—similar to a method used in the Medicaid drug rebate program—to the current WIC contract system. In their models, researchers set a national WIC infant formula rebate at 55 percent of the retail price. Their analysis suggested that at least two infant formula manufacturers would be willing to participate at this rebate percentage. In their scenario, any manufacturer that agreed to provide this rebate to states could sell their formula to WIC participants.

Use of a federally set rebate could have some advantages, but would likely increase program costs, according to this study’s researchers. Specifically, they noted that this alternative could allow more manufacturers to compete in the WIC market, including smaller manufacturers that agreed to provide a rebate. Additional formula brands in the WIC market would provide more choices to WIC participants and could potentially lower prices for non-WIC consumers. However, the researchers estimated that federal government costs for a given population served would increase due to lower rebate percentages in their model. With lower rebate savings and increased government costs, the WIC program would likely serve fewer participants under this option without additional funding.

Cash Value Benefit for Infant Formula Purchases

WIC officials we interviewed from two states suggested that it could be beneficial to pilot a cash value benefit for infant formula that would allow participants to purchase additional brands of formula. The benefit could be coupled with a “not-to-exceed amount” set by the state agency to help contain infant formula costs.[93] WIC uses a cash value benefit for fruit and vegetable purchases adjusted annually for inflation.[94]

Providing WIC participants with a cash value benefit for infant formula has some advantages, according to two stakeholders we interviewed. For example, using a cash value benefit could allow the program to provide WIC consumers more choices of formula. Without the single supplier contract, more companies’ products may be available on store shelves, which could help consumers find formula if one company experiences a supply chain disruption. With cash value benefits, WIC participants would be more price sensitive, so retailers would have an incentive to lower prices. Increased competition among manufacturers, resulting from the loss of exclusive single-supplier contracts, could also result in lower formula prices. In addition, states would incur fewer administrative costs related to WIC contracting.

However, eliminating the use of single-supplier contracts for WIC infant formula could also eliminate the cost savings from manufacturers’ rebates, which would have implications. ERS researchers noted that the implications would depend on whether the quantity of formula provided to WIC participants was maintained or whether containing program costs was the primary goal. According to ERS researchers we interviewed, if the quantity of formula for participants was maintained at current levels, then a cash value benefit for formula would substantially increase the cost of the WIC program or result in fewer participants served unless Congress provides additional funding.[95] Alternatively, if a cash value benefit for formula was used as a cost containment measure, the benefit amount would need to be set at an amount low enough to offset the loss of rebates, absent other program changes. As a result, WIC participants would not be able to purchase as much formula with their benefits, which could put infants at increased risk of malnutrition, according to ERS researchers we interviewed.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to USDA for review and comment. USDA provided technical comments on a draft of this report, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We will send copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Agriculture and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact us at (202) 512-7215 or larink@gao.gov, or (202) 512-2700 or hoffmanme@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Kathryn A. Larin

Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security

Michael Hoffman

Director

Center for Economics

Applied Research and Methods

List of Requesters

The Honorable John Boozman

Chairman

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

United States Senate

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

United States Senate

The Honorable Susan M. Collins

United States Senate

The Honorable John Cornyn

United States Senate

The Honorable Deb Fischer

United States Senate

The Honorable Charles E. Grassley

United States Senate

The Honorable Roger W. Marshall, M.D.

United States Senate

The Honorable James E. Risch

United States Senate

The Honorable Thom Tillis

United States Senate

National Trends in Retail Price

We used retail scanner data from NielsenIQ, a consumer intelligence company, to examine national level trends in average retail infant formula prices. These data contain annual data on the average unit price, total units sold, and total sales for 98 different infant formula products from 2013 to 2023.[96] Each product is depicted by a unique Universal Product Code (UPC) in the NielsenIQ data. Our selected UPCs contain the milk and soy Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) primary contract brand infant formula products as well as similar non-primary WIC brand products.[97] We focused on products by formula brands with WIC contracts and did not include products by brands that do not have WIC contracts. Our selected UPCs represent about 64 percent of total infant formula sales.

The infant formula products available over time can change as manufacturers introduce new products and discontinue others. To assess trends in average prices over the 10-year period, we used a subset of products that were in the data in every year so that we could examine changes in a constant set of products.[98] We focused on milk-based products in this report because milk-based is more commonly purchased than soy-based products.[99] We also examined trends in national average prices of WIC primary contract soy-based products and found that soy concentrate and powder products followed a similar trend as milk-based products while the average price of WIC primary contract soy ready-to-feed products was generally increasing over time.[100]

Average retail price is estimated as the total dollars sales of an item divided by the total units sold of that item.[101] Because infant formula products are sold in different sized packages and different forms, we used item price to create a standardized measure of price represented as the price per 26 reconstituted ounces of formula. Reconstituted fluid ounces refer to the amount of formula that a product will produce when prepared at standard dilution. For example, a typical WIC eligible container of milk-based powder formula contains about 12.4–12.9 ounces of powder formula and makes about 90–92 fluid ounces of formula when mixed with water while a typical container of concentrate formula contains 13 ounces of concentrated formula and makes 26 fluid ounces of formula when mixed with water. We examined prices per 26 reconstituted fluid ounces, which is the method used in prior U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) studies.[102] Average retail prices per 26 reconstituted ounces were weighted by the sales quantity of the observation to account for varying sales volume of different products.[103] We inflation-adjusted prices to 2023 dollars using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) all items index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Trends in Infant Formula Rebates

To examine trends in WIC infant formula rebates over time, we examined infant formula rebate contract data provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). These data contain information on each state agency’s WIC contract formulas for each form of formula, the contract length, wholesale price, and rebate amount for contracts in place from 2013 through August 2024, meaning they may have start or end dates beyond that time frame. To examine trends in WIC participation, food costs, and total rebates, we examined FNS state-level WIC participation and program cost data for calendar years 2013 to 2023.

Econometric Analysis of WIC Contract Status on Retail Price, Sales, and Market Share

We used quarterly state-level NielsenIQ retail scanner data from quarter four of 2018 to quarter three of 2023 to examine the impact of WIC contracts on infant formula retail prices, sales quantities, sales dollars, and market share.[104] These data contain information from participating retailers on average unit price, total units sold, and total dollar sales at a quarterly level for 95 products in 30 states for which NielsenIQ could provide state-level data.[105] As in the national trends analysis above, we excluded all soy-based infant formula products. Thus, our analytical sample contains information on 78 milk-based products in 30 states.[106] Our data have some shortcomings that limit our ability to describe the entire U.S. infant formula market, which we discuss in more detail after describing our specification below.