ILLICIT FINANCE

Agencies Could Better Assess Progress in Countering Criminal Activity

Report to the Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse, United States Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106568. For more information, contact Triana McNeil at (202) 512-8777 or McneilT@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106568, a report to the Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse, United States Senate

Agencies Could Better Assess Progress in Countering Criminal Activity

Why GAO Did This Study

Criminal organizations generate money from illicit activities such as drug and human trafficking and launder the proceeds. Federal agencies investigate illicit activity and have developed several strategies and efforts to combat these crimes.

GAO was asked to review efforts to counter illicit finance activities. This report addresses, among other things, (1) selected agencies’ roles and responsibilities in investigating and prosecuting illicit finance activities and (2) the progress made with selected strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activities.

To address these objectives, GAO reviewed agency documents and data, including those related to eight selected federal strategies and efforts on countering illicit finance activities. GAO compared four of these strategies and efforts—which represent long-range, multiagency undertakings—to selected key practices for evidence-based policymaking and for interagency collaboration.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations, including that Treasury collect and assess performance information on implementing the Illicit Finance Strategy, and that the Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development establish goals and assess progress for implementing the Initiative. Treasury disagreed with the recommendation, State agreed with the intent of the recommendation but believes it already addressed it, and USAID agreed. The National Security Council did not provide comments.

What GAO Found

Key federal agencies are responsible for investigating entities involved in illicit finance activities and referring them for federal prosecution. For example, the Federal Bureau of Investigation investigates transnational criminal organizations and associated money laundering efforts. Similarly, Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations conducts investigations of criminal organizations in relation to cross-border movement of people, goods, and money. These federal law enforcement agencies and others often work together in interagency collaborative groups, such as task forces, that coordinate investigations of transnational organized crime, money laundering, and major drug trafficking networks. The Department of Justice prosecutes defendants accused of committing federal crimes, including those related to illicit finance.

Federal agencies are taking actions to implement selected government-wide strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activities, but progress in implementation is not measured in some instances. In these cases, the strategies and efforts do not all have clearly defined goals, and lead agencies or entities do not regularly collect and assess relevant performance information tied to goals. For example, in the 2024 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing (Illicit Finance Strategy), the Department of the Treasury lists over 120 benchmarks (or goals) that agencies are generally implementing. However, Treasury does not collect and assess performance information from the implementing agencies to determine their progress against the goals. Similarly, entities leading the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal (Initiative)—a set of policy and foreign assistance efforts to fight corruption, among other things—have not set joint performance goals or assessed whether agencies are achieving the goals. Such goals and assessments of performance information could help collaborating agencies ensure accountability for common outcomes and inform decisions, which would be in line with leading practices for evidence-based policymaking and interagency collaboration.

Abbreviations

AMLA Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020

AML/CFT anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism

CATS Consolidated Asset Tracking System

DEA Drug Enforcement Administration

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DOJ Department of Justice

EOUSA Executive Office for United States Attorneys

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

FinCEN Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

HSI Homeland Security Investigations

ICE Immigration and Customs Enforcement

IOC-2 International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations

Center

IRS Internal Revenue Service

IRS-CI Internal Revenue Service – Criminal Investigation

MOU Memorandum of Understanding

NSC National Security Council

OCDETF Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces

OFAC Office of Foreign Assets Control

ONDCP Office of National Drug Control Policy

REPO Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force

TFFC Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

USCTOC U.S. Council on Transnational Organized Crime

USPIS U.S. Postal Inspection Service

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 16, 2025

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

United States Senate

Dear Senator Whitehouse:

Transnational criminal organizations use illicit activities such as human or drug trafficking or cyber fraud to generate money.[1] In many cases, these groups will launder the money they make to facilitate, conceal, and promote their crimes, which can distort markets and the broader financial system. The United States is particularly vulnerable to all forms of illicit finance because of the size of the U.S. financial system and centrality of the U.S. dollar in global trade.[2]

A number of federal departments including the Departments of Justice (DOJ), Homeland Security (DHS) and the Treasury, either individually or as part of collaborative groups, are charged with combating entities that conduct money laundering activities. The federal government has also developed strategies, executive orders, task forces, and other efforts in recent years aimed at countering illicit finance activities. For example, the National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing guides U.S. government efforts to address the most significant illicit finance threats and risks to the U.S. financial system.[3]

You asked us to review how the federal government investigates illicit finance activities, achieves goals, and collaborates to counter these activities and criminal networks. This is our second report responding to your request.[4] This report addresses (1) selected agencies’ roles and responsibilities in investigating and prosecuting entities involved in illicit finance activities; (2) the progress made with selected strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activities; (3) the extent to which selected law enforcement and intelligence agencies collaborate with federal and foreign entities to counter illicit finance activities; and (4) the availability of agency and government-wide estimates of resource and workforce needs to counter illicit finance.

To inform our work, we reviewed the following six agencies: Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), Internal Revenue Service’s Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI), U.S. Postal Inspection Service (USPIS), and U.S. Secret Service. We selected these agencies because they were responsible for referring about 75 percent of all money laundering-related cases to federal prosecutors during fiscal years 2018 through 2022, according to the most recent data available at the time of our selections, obtained from the Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA).[5] In addition to these agencies, we identified five interagency collaborative groups that combat illicit finance and money laundering activities for inclusion in our discussion of roles and responsibilities, as well as for answering our third objective (discussed further below). These collaborative groups are the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) Fusion Center, International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations Center (IOC-2), DEA Special Operations Division, El Dorado Task Force, and Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team.[6]

To address our first objective, we reviewed applicable laws and regulations, Congressional Budget Justifications, performance reports, and memoranda of understanding and interviewed officials from our selected agencies and interagency collaborative groups. To identify agencies responsible for prosecuting and assessing penalties against entities conducting illicit financial activity, we leveraged information from a prior GAO report on anti-money laundering and interviewed officials from the Department of Justice.[7]

To address our second objective, we reviewed relevant strategies and efforts and related implementation plans, including those publicly and not publicly available (e.g., documents marked sensitive by agencies).[8] Of these strategies and efforts, we selected four that we characterized as long-range, multiagency undertakings related to countering illicit finance activities. These were the National Drug Control Strategy; National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing; the United States Strategy on Countering Corruption; and the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal. In particular, we reviewed these four strategies and efforts to determine whether they contained clearly identifiable goals and information related to assessing performance tied to these goals.[9] For the selected four strategies and efforts, we then reviewed agency responses and documentation and compared them to key practices for evidence-based policymaking, such as setting goals to identify results, collecting performance information to measure progress, and using that information to assess results and inform decisions. We also compared them to leading practices to enhance interagency collaboration, such as ensuring accountability for common outcomes by monitoring progress toward the outcomes.[10] We further interviewed officials at agencies contributing to or responsible for leading all of the strategies and efforts in our review to better understand the status of their implementation efforts, including performance information for achieving stated goals.[11]

To address the third objective examining law enforcement and intelligence agencies’ collaboration to counter illicit finance, we conducted 11 semi-structured group interviews with a nongeneralizable sample of staff from the following collaborative groups: OCDETF Fusion Center, IOC-2, El Dorado Task Force, the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team, and Special Operations Division.[12] We developed a question set for the group interviews based on selected key considerations for implementing leading interagency collaboration practices.[13] The information collected during these group interviews and our analysis are not generalizable to all individuals involved in these collaborative groups. However, the views shared during these discussion groups provided insights into how effectively the selected groups facilitated collaboration between members.

To address our fourth objective on agency and government-wide estimates of resource and workforce needs to counter illicit finance, we reviewed documentation and written responses to questions provided by the agencies as applicable. We also interviewed the agencies in our scope about how they estimate workforce and resource needs related to illicit finance activities. We further interviewed selected agency officials regarding their workforce estimation processes.

See appendix I for additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Agencies Involved in Countering Illicit Financial Activity

Various federal law enforcement agencies have responsibilities related to detecting illicit financial activity and conducting investigations of money laundering and related violations.[14] For example:

· DOJ investigates and prosecutes violations of federal criminal law, including money laundering statutes. Within DOJ, the DEA and FBI investigate drug trafficking and transnational criminal organizations and their money laundering activities. The FBI also gathers intelligence related to these and other federal crimes and threats to national security. Upon conviction of a federal criminal offense, district courts may impose statutory fines and other penalties, including terms of imprisonment. In addition, courts may impose restitution and the government may forfeit assets seized by law enforcement.

· Within DHS, U.S. ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) component targets transnational criminal organizations, and agents investigate money laundering, illicit finance, and other financial crimes related to how those organizations receive, move, launder, and store their illicit funds. The Secret Service also targets transnational criminal organizations engaged in illicit finance, cybercrimes, counterfeiting, and money laundering involving financial institutions and payment systems.

· Within the Department of the Treasury (Treasury), IRS-CI investigates complex and significant money laundering activity, including activities related to terrorism financing and transnational organized crime.[15]

· Law enforcement task forces and collaborative groups, such as OCDETF—part of DOJ—and the El Dorado Task Force, led by HSI, conduct illicit finance investigations. These task forces investigate transnational criminal organizations and seek to dismantle the financial networks that support them.

In addition, Treasury and its Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) are charged with enforcing the Bank Secrecy Act and its implementing regulations to combat money laundering and other criminal financial activity. The Bank Secrecy Act, as amended, and its implementing regulations require financial institutions to monitor customer transactions to identify suspicious activity that may indicate money laundering or other criminal activity.[16] The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA) was enacted in January 2021, in part, to modernize the anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regulatory framework.[17] AMLA charges the Secretary of the Treasury or FinCEN Director with various implementation responsibilities.

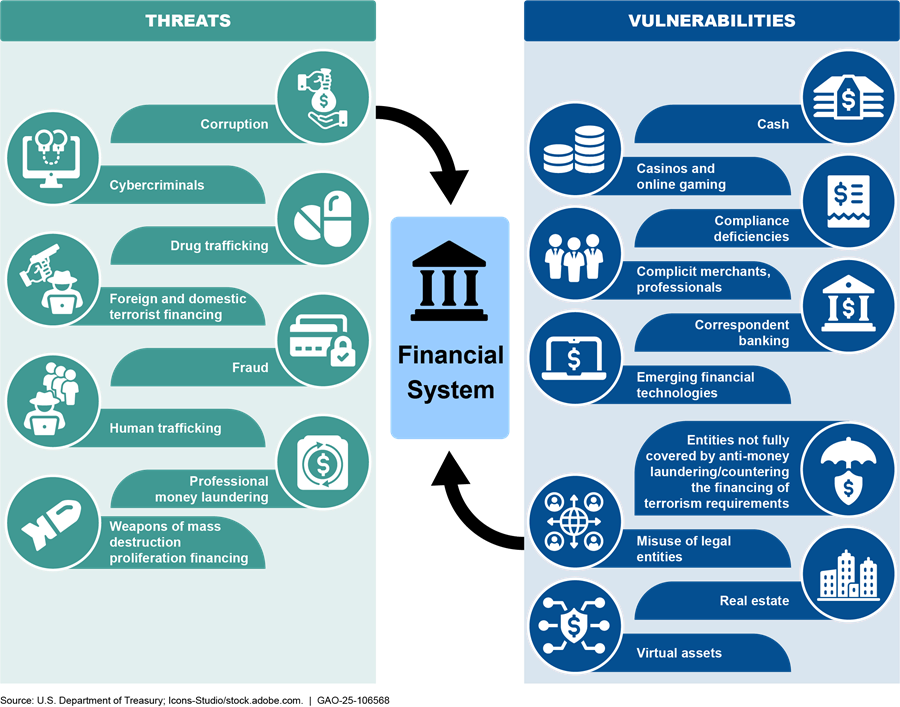

To address one particular AMLA requirement, in June 2021, FinCEN issued the first government-wide AML/CFT national priorities list, which is intended to help financial institutions prioritize compliance resources and risk management in relation to current threats.[18] According to FinCEN, the priorities, in no particular order, are (1) corruption; (2) cybercrime, including relevant cybersecurity and virtual currency considerations; (3) foreign and domestic terrorist financing; (4) fraud; (5) transnational criminal organization activity; (6) drug trafficking organization activity; (7) human trafficking and human smuggling; and (8) proliferation financing.[19]

In February 2024, we reported on FinCEN’s efforts in implementing various provisions of the Bank Secrecy Act and AMLA, as well as federal data collection on the outcomes of illicit finance investigations.[20] We found that FinCEN had not provided Congress and the public with a full picture of its progress in implementing all sections of AMLA for which it has implementation responsibilities. We also found that it was difficult to determine total outcomes of illicit finance investigations across the federal government because monitoring and data collection were fragmented across individual agencies.

We recommended, among other things, that FinCEN develop and implement a plan to inform Congress and the public about its progress in implementing AMLA, and that the Attorney General coordinate with DHS and Treasury to develop a methodology for producing government-wide data on the outcomes of anti-money laundering investigations. FinCEN did not comment on these recommendations at the time our report was issued, but in September 2024, noted that it agreed with recommendations directed to the agency and was taking actions to implement them. DOJ agreed with the recommendation for the Attorney General and informed us in November 2024 that it is taking steps to implement it. We will continue to monitor the status of agency efforts to implement these recommendations.

Federal Strategies and Efforts to Combat Illicit Finance Activities

In addition to law enforcement responsibilities to detect illicit finance activity and conduct investigations, several strategies and efforts[21] exist to combat illicit finance activities, such as those involving terrorism, corruption, transnational crime, and the actions of kleptocracies.[22] The national strategies are intended to holistically address these issues among multiple agencies, while other efforts are more targeted approaches to specific issues, such as the sanctioning of foreign individuals or freezing of Russian assets. Table 1 summarizes the purpose of each strategy and effort and identifies lead agencies responsible for overseeing their implementation.[23]

Table 1: Summary of Selected U.S. Strategies and Efforts Related to Combating Illicit Finance Activities

|

Strategy or effort |

Lead agencies |

Summary |

|

National Drug Control Strategya |

Office of National Drug Control Policy |

Sets forth a government-wide plan to reduce illicit drug use and its consequences in the U.S. by limiting the availability of drugs. The strategy aims to reduce the demand for drugs and promote prevention, early intervention, treatment, and recovery support. The disruption of illicit finance networks is one focus area of this strategy. |

|

National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financingb |

Department of the Treasury’s Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes |

Intended to guide efforts to address the most significant illicit finance threats and risks to the U.S. financial system. The response includes efforts to modernize the U.S. anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism regime so that the public and private sectors can effectively focus resources against the most significant illicit finance risks. |

|

United States Strategy on Countering Corruption |

White House, coordinated by the National Security Council |

Lays out an approach for how the U.S. will work domestically and internationally to prevent, limit, and respond to corruption and related crimes. This strategy places special emphasis on the transnational challenges posed by corruption. |

|

Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal |

National Security Council in consultation with Department of State and United States Agency for International Development |

Focuses on strengthening democracy, defending against authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and promoting human rights. It is comprised of policy and foreign assistance initiatives that support democracy and defend human rights with like-minded governmental and non-governmental partners. |

|

Task Force KleptoCapture |

Department of Justice’s Office of the Deputy Attorney General |

An interagency law enforcement task force dedicated to enforcing sanctions, export restrictions, and economic countermeasures that the U.S. has imposed, along with allies and partners, in response to Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine. |

|

Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force |

Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control |

Uses its authorities in concert with other appropriate national ministries to collect and share information to take concrete actions, including sanctions, asset freezing, and civil and criminal asset seizure, and criminal prosecution. This task force works to ensure the effective, coordinated implementation of the group’s collective financial sanctions relating to Russia, as well as assistance to other nations to locate and freeze assets located within their jurisdictions. |

|

Expansion of Treasury authorities to impose sanctions on foreign persons involved in the global illicit drug tradec |

Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control |

Executive Order 14059 declared a national emergency to address international drug trafficking—including the production, global sale, and widespread distribution of illegal drugs; the rise of extremely potent drugs such as fentanyl; as well as the growing role of internet-based drug sales. This Executive Order authorizes the Secretary of Treasury to impose sanctions on foreign individuals involved in the illicit drug trade. |

|

Establishment of the United States Council on Transnational Organized Crimed |

U.S. Council on Transnational Organized Crime |

Established by Executive Order 14060, the U.S. Council on Transnational Organized Crime is to monitor the production and implementation of coordinated strategic plans for whole-of-government efforts to counter transnational organized crime. This is to be done in support of and in alignment with policy priorities established by the President through the National Security Council. |

Source: GAO summary of agency documentation. | GAO‑25‑106568

a21 U.S.C. 1705.

bSee Pub. L. No. 115-44, 261, 262, 131 Stat. 886, 934-36.

cExec. Order No. 14059, 86 Fed. Reg. 71,549 (Dec. 15, 2021).

dExec. Order No. 14060, 86 Fed. Reg. 71,793 (Dec. 15, 2021).

Federal Agencies Have Various Roles and Responsibilities in Investigating and Prosecuting Entities Involved in Illicit Finance Activities

Selected Agencies Conduct Investigations as Part of Their Role in Countering Illicit Finance Activities

Multiple federal law enforcement agencies investigate illicit finance, among other crimes, and related money laundering. For example, the FBI is charged with enforcing over 200 categories of federal laws, which include investigations of transnational crime and financial crimes.[24] As another example, Secret Service investigates cybercrimes, counterfeiting, and fraud and money laundering involving financial institutions and payment systems.[25] Table 2 below provides more information on selected federal agencies’ roles in countering illicit financial activities.

Table 2: Responsibilities of Selected Federal Law Enforcement Agencies in Countering Illicit Financial Activities

|

Agency |

Relevant responsibilities |

|

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) |

The FBI is responsible for collecting intelligence and conducting investigations into federal crimes and threats to the national security of the U.S.a It investigates transnational criminal organizations and their money laundering efforts, among other things. |

|

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) |

DEA is responsible for enforcing U.S. controlled substances laws and regulations.b As part of its investigations, DEA attempts to disrupt or dismantle targeted drug organizations, which includes impeding or destroying the organizations’ financing or financial base. |

|

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) |

ICE is responsible for enforcing federal laws governing border control, customs, trade, and immigration. HSI has legal authority to conduct federal criminal investigations into the illegal cross-border movement of people, goods, money, technology, and other contraband. It also has the legal authority to investigate certain cybercrimes, virtual currency crimes, the financial integrity of financial institutions, money laundering, and kleptocracy. HSI combats transnational criminal enterprises that seek to exploit legitimate trade, travel, and financial systems. |

|

United States Secret Service (Secret Service) |

The Secret Service is responsible for enforcing laws governing the U.S. financial and payment systems. This includes legal authority to investigate certain financial crimes, including crimes targeting financial institutions and payment systems, counterfeiting of U.S. obligations, bank fraud, money laundering, and other unlawful activity involving financial transactions. The Secret Service also has authority to investigate certain cybercrimes, such as unauthorized access to computers and systems and the resulting money laundering.c |

|

Internal Revenue Service’s Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI) |

IRS-CI is responsible for enforcing criminal statutes relating to violations of internal revenue laws and other financial crimes. IRS-CI investigates cases of fraud involving both legal and illegal sources of income. Its cases include violations of tax laws, mortgage fraud, and money laundering, as well as the profits and financial gains of organized crime groups involved in narcotics and money laundering. |

|

U.S. Postal Inspection Service (USPIS) |

USPIS is the law enforcement arm of the U.S. Postal Service. Its responsibilities include monitoring the flow of bulk cash seized in the mail and interdicting and investigating illicit drugs and their proceeds, as well as firearms, trafficked through the U.S. mail. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from the agencies listed above. | GAO‑25‑106568

Note: The agencies in this table represent over 75 percent of all money laundering-related cases referred to federal prosecutors from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. We obtained the data used to make this determination from the Executive Office for United States Attorneys.

aSee 28 C.F.R. 0.85.

bReorganization Plan No. 2 of 1973, Exec. Ord. No. 11,727, 38 Fed. Reg. 18,357 (July 10, 1973).

c18 U.S.C. 1030 and 3056.

Some of these agencies track and report performance measures on illicit finance cases and high-priority organizations that have been disrupted or dismantled.[26] See appendix II for selected examples of these data.

Each of the agencies above is responsible for investigating potential violations of specified federal laws, such as DEA’s enforcement of controlled substances laws and regulations under Title 21 of the United States Code and Code of Federal Regulations.[27] In addition, some agencies are authorized to investigate potential violations of the same or similar laws. Figure 1 provides an illustration of some of these similar responsibilities.

Figure 1: Types of Illicit Finance Activities That Selected Agencies’ Investigative Responsibilities May Involve

In addition to individual agencies’ investigations, multiagency investigations are conducted or supported through collaborative groups such as the OCDETF Fusion Center and the IOC-2. These groups serve to share information among participating agencies and coordinate and deconflict investigations, among other things, as shown in table 3. See appendix III for more information on these collaborative groups’ missions and participating agencies.

Table 3: Missions of Selected Collaborative Groups That Conduct or Support Illicit Finance and Money Laundering Investigations

|

Collaborative group |

Mission |

Lead Agency |

|

Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) |

OCDETF, an independent component within the Department of Justice (DOJ), uses a prosecutor-led, multiagency approach to lead coordinated investigations of transnational organized crime, money laundering, and major drug trafficking networks. |

DOJ |

|

OCDETF Fusion Center |

The OCDETF Fusion Center is a data center that manages drug and related financial intelligence information from OCDETF’s partner investigative agencies and other partners to create intelligence pictures of targeted organizations, among other things. |

OCDETF |

|

El Dorado Task Force |

The El Dorado Task Force is an anti-money laundering task force consisting of numerous law enforcement agencies—including federal agents; international, state, and local police investigators; intelligence analysts; and federal prosecutors—located at Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) field offices.a |

ICE HSI |

|

International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations Center (IOC-2) |

IOC-2 creates and disseminates intelligence products to support criminal investigations and prosecutions across the country and is regularly involved in deconfliction and case coordination.b |

OCDETF |

|

Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team |

This team is a Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI)-led initiative that supports, coordinates, and assists in deconfliction of investigations targeting the sale of illegal drugs online, especially fentanyl and other opioids. |

FBI |

|

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Special Operations Division |

The Special Operations Division is a DEA-led, multiagency operational coordination center aimed at dismantling drug trafficking and terrorist organizations by attacking their command, control, and communications. |

DEA |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by each of the lead agencies listed above. | GAO‑25‑106568

aThe first El Dorado Task Force was formed in HSI’s New York office. ICE officials have informed us that during the course of our review, the El Dorado Task Force model has been implemented at all 30 HSI field offices with a Special Agent in Charge throughout the U.S.

bIOC-2 and OCDETF Fusion Center officials have noted that when each entity was stood up, the OCDETF Fusion Center focused more on supporting drug trafficking investigations, with IOC-2 focused more on transnational organized crime. However, over time the OCDETF Fusion Center’s mission has expanded to include more transnational organized crime-related investigations. The officials stated that the two groups are working together to better delineate their separate responsibilities.

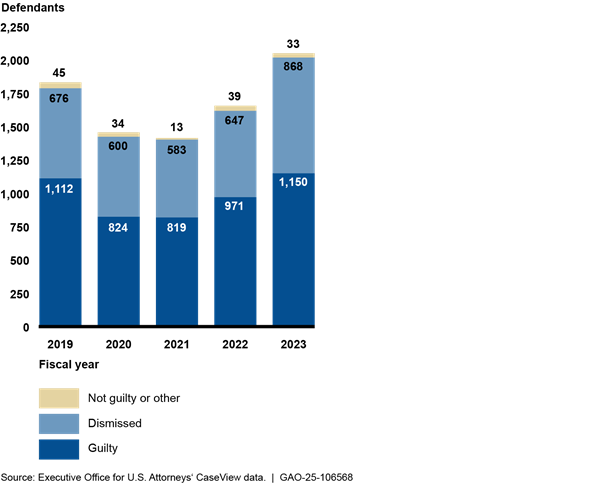

DOJ Prosecutes Defendants Charged with Violating U.S. Anti-Money Laundering Laws

Federal prosecutors in DOJ are generally responsible for prosecuting defendants accused of violating U.S. anti-money laundering and other federal laws.[28] Federal law enforcement agencies, upon determining that they have obtained sufficient evidence to pursue prosecution, may refer such cases to federal prosecutors in DOJ for prosecution or collaborate with federal prosecutors to develop cases that are appropriate for prosecution. See appendix II for data on money laundering-related charges referred to federal prosecutors, convictions, and sentence lengths for defendants found guilty from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023.[29]

|

Examples of prosecutions and seizures in relation to money laundering-related charges In August 2022, two defendants were sentenced to 97 months and 36 months incarceration, respectively, and ordered to pay a total of $12,313,364 in restitution and forfeit $5 million. These sentencings resulted from Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces’ (OCDETF) Operation Five Fingers, a joint investigation into a Nigerian and Ghanaian transnational organized crime group that targeted businesses with email compromise schemes to steal personally identifiable information and proceeds, and then laundered the proceeds. Agencies involved included the Department of Labor Office of Inspector General, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), and the U.S. Secret Service. Source: OCDETF | GAO‑25‑106568 In December 2023, Ezequiel Alanis Espitia, the leader of a conspiracy carried out on behalf of the Gulf Cartel in Mexico, was sentenced to 27 years in federal prison following a multiagency OCDETF investigation conducted by HSI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, Internal Revenue Service’s Criminal Investigation, and the Houston Police Department. Mr. Espitia pled guilty to money laundering and conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute controlled substances. As of his sentencing, 15 other individuals had also been convicted for their roles in the conspiracy. Law enforcement officials seized $610,400 in drug proceeds during the course of the investigation. Source: Immigration and Customs Enforcement. | GAO‑25‑106568 |

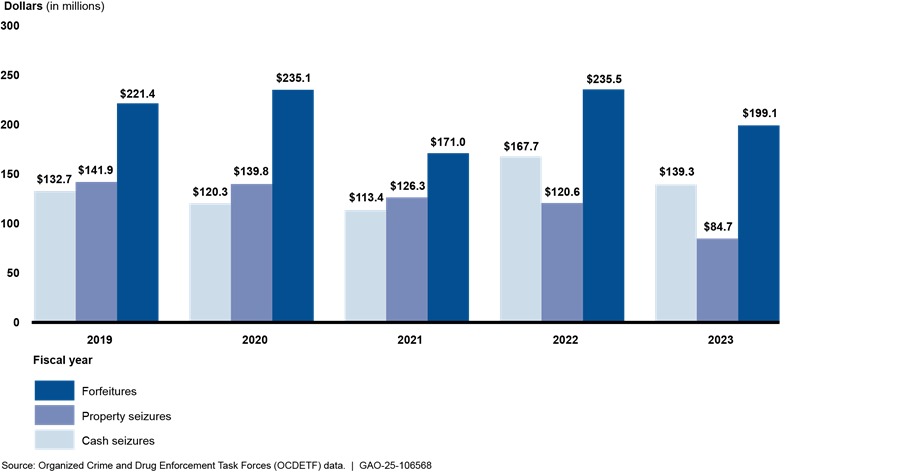

In certain instances, individuals suspected of committing federal criminal offenses, including money laundering-related offenses, may have assets seized for evidence or for forfeiture, or both. Seizure involves the physical restraint of an asset or its transfer from the owner or possessor to the custody or control of the government through a law enforcement agency.[30]

Defendants charged and convicted of money laundering-related offenses or other offenses may be subject to imprisonment and various types of penalties, including:

Fines: The U.S. District Courts where cases are tried may order fines for the criminal violations of money-laundering statutes.

Asset Forfeitures: This is the taking of property by the government without compensation because of the property’s connection to criminal activity. There are three types of asset forfeiture: criminal, civil, and administrative.[31]

Appendix II contains data on fines assessed and assets seized or forfeited in relation to money laundering-related charges from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023.

Agencies’ Assessments of Countering Illicit Finance Activities Provide Limited Insights Into Progress

Agencies have multiple strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activities and are taking actions to implement them. However, progress toward implementing them is not always clear because lead agencies have not set clearly defined goals or regularly collected and assessed relevant performance information tied to the goals.

Agencies Are Taking Actions to Implement Strategies and Efforts to Counter Illicit Finance Activities

Several federal agencies and entities are leading or taking actions to implement eight government-wide strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activity.[32] These are (1) the National Drug Control Strategy; (2) the National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing; (3) the United States Strategy for Countering Corruption; (4) the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal; (5) an expansion of Treasury authorities to impose sanctions on foreign persons involved in the global illicit drug trade; (6) the U.S. Council on Transnational Organized Crime; (7) Task Force KleptoCapture; and (8) the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs (REPO) Task Force.

National Drug Control Strategy

The National Drug Control Strategy is to set forth a comprehensive plan to (1) reduce illicit drug use in the U.S. by limiting the availability of, and reducing the demand for, illegal drugs and (2) promote prevention, early intervention, treatment, and recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders.[33] The Office of National Drug Control Policy’s (ONDCP) mission is to reduce substance use disorder and its consequences by coordinating the nation’s drug control policy through the development and oversight of the National Drug Control Strategy and National Drug Control Budget.[34] In part, it prioritizes a targeted response to drug traffickers and transnational criminal organizations, includes efforts to strengthen domestic law enforcement cooperation to disrupt the trafficking of illicit drugs within the U.S, and aims to increase collaboration with international partners to disrupt the supply chain of illicit substances and the precursor chemicals used to produce them.

In May 2024, ONDCP released its 2024 National Drug Control Strategy and 2024 National Drug Control Assessment, which include descriptions of the progress made toward each of the goals and objectives since the 2022 National Drug Control Strategy.[35] For example, the 2024 National Drug Control Strategy states that progress has been made on advancing efforts to reduce the supply of illicit substances through domestic collaboration and interagency coordination. Such efforts include focusing federal investigations on priority transnational criminal organizations engaged in drug trafficking.

National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing

The 2024 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing (Illicit Finance Strategy) identifies steps to increase transparency in the U.S. financial system and strengthen the U.S. anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) framework.[36] To accomplish this, the 2024 Illicit Finance Strategy identifies four priorities—derived and continuing from the 2022 Illicit Finance Strategy—to guide U.S. government efforts and address the most significant illicit finance threats and risks to the U.S. financial system. The four priorities are the following:

1. Assess and address legal and regulatory gaps in the U.S. AML/CFT regime

2. Make the U.S. AML/CFT regulatory and supervisory framework for financial institutions more risk-focused and effective

3. Enhance the operational effectiveness of law enforcement and other U.S. government agencies in combating illicit finance

4. Support responsible technological innovation and harness technology to mitigate illicit finance risks

The 2024 Illicit Finance Strategy provides a summary of the progress that the Department of Treasury’s (Treasury) Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes and its federal partners have made toward implementing the 2022 Illicit Finance Strategy. Treasury officials we spoke with said a key goal of the 2022 Illicit Finance Strategy was implementing the Corporate Transparency Act, with the ultimate launch of the Beneficial Ownership Information Registry on January 1, 2024.[37] In addition, since 2022, Treasury has conducted a number of risk assessments identifying significant money laundering and illicit finance threats and vulnerabilities to the United States, which the priorities and supporting actions of the Illicit Finance Strategy are intended to address. See appendix IV for further information on these threats and vulnerabilities.

United States Strategy for Countering Corruption

The 2021 United States Strategy for Countering Corruption (Strategy) lays out the U.S. government’s approach for working domestically and internationally, with governmental and nongovernmental partners, to prevent, limit, and respond to corruption and related crimes. The Strategy emphasizes the transnational dimensions of the challenges posed by corruption, including by recognizing the ways in which corrupt actors have used the U.S. financial system and other rule-of-law based systems to launder their ill-gotten gains. According to the Strategy, to curb corruption and its effects, the U.S. government will organize its efforts around five mutually reinforcing areas of work: (1) modernizing, coordinating, and resourcing U.S. efforts to fight corruption; (2) curbing illicit finance; (3) holding corrupt actors accountable; (4) preserving and strengthening the multilateral anti-corruption architecture; and (5) improving diplomatic engagement and leveraging foreign assistance.

In 2023, the White House released two reports that described agencies’ efforts toward implementing the Strategy, organized according to its five areas of work. For example, Treasury advanced efforts to implement the Corporate Transparency Act and prevent criminals from using shell and front companies to launder illicit proceeds by issuing a final rule that requires certain entities to report information about their beneficial owners to FinCEN.[38] In addition, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) launched a Financial Transparency and Integrity Democracy Cohort to spur action and encourage implementation of commitments to prevent corruption. Also related to the Strategy, in 2024, FinCEN issued final rules intended to help safeguard the residential real estate and investment adviser sectors from illicit finance.[39]

Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal

In 2021, the White House announced the establishment of the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal (Initiative), a set of policy and foreign assistance efforts that are intended to build upon the U.S. government’s ongoing work to bolster democracy and defend human rights globally. According to the announcement, the Initiative centers on five areas of work related to the functioning of transparent, accountable governance: (1) supporting free and independent media; (2) fighting corruption; (3) bolstering democratic reformers; (4) advancing technology for democracy; and (5) defending free and fair elections and political processes.

From 2022 to 2024, the White House released annual reports that described agencies’ efforts toward implementing the Initiative, organized according to the five areas of work. For example, related to the fighting corruption area of work, the U.S. government and its foreign partners announced in 2023 the Summit for Democracy Commitment on Beneficial Ownership and Misuse of Legal Persons. The goal of the commitment is to enhance beneficial ownership transparency to make it more difficult for corrupt actors to conceal their identities, assets, and criminal activities. USAID assigned the Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance to further implement key aspects of the Initiative. In addition, State appointed a Coordinator on Global Anti-Corruption to strengthen international coordination on anti-corruption issues and advance U.S. anti-corruption priorities.

Expansion of Treasury Authorities to Impose Sanctions on Foreign Persons Involved in the Global Illicit Drug Trade

In December 2021, the White House declared a national emergency to address international drug trafficking and authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to impose sanctions on foreign individuals involved in the illicit drug trade.[40] Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions based on U.S. foreign policy and national security goals. These sanctions are targeted to certain foreign countries and regimes, terrorists, international narcotics traffickers, and other threats. According to a White House report, the new authorities build on two decades of sanctions imposed pursuant to the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act and implements, in part, the Fentanyl Sanctions Act.[41]

In response to the national emergency declaration, Treasury has submitted four reports to Congress detailing actions OFAC has taken to sanction foreign individuals and entities involved in the illicit drug trade. According to the four reports, which covered the period from December 15, 2021, to October 23, 2023, OFAC closed 12 licensing cases and received reports on blocking 119 transactions or accounts pursuant to the expanded sanction authorities.[42] The blocked transactions or accounts totaled approximately $2.758 million. In addition, from January 2022 through December 2023, OFAC reported making 238 total designations—142 individuals and 96 entities—for activities related to the international proliferation or production of illicit drugs.[43]

U.S. Council on Transnational Organized Crime

Established in December 2021, the U.S. Council on Transnational Organized Crime (USCTOC) brings together six departments and agencies involved in counter-transnational organized crime efforts. This council facilitates information sharing and aims to ensure that the U.S. government leverages its tools to counter the threats posed by transnational criminal organizations.[44] According to a White House report, the council is to coordinate government-wide lines of effort to counter transnational organized crime and restructure and enhance the U.S. government’s Threat Mitigation Working Group.[45]

USCTOC is to monitor the production and implementation of coordinated strategic plans for whole of government counter-transnational organized crime efforts. The USCTOC strategic division, an interagency working group within DOJ, is responsible for drawing on law enforcement and intelligence community information to produce the coordinated strategic plans that support policy priorities established by the President through the National Security Council.[46] The executive order creating the USCTOC also charged the Director of National Intelligence with providing annual reports to the President assessing the intelligence community’s posture with respect to transnational organized crime-related collection efforts. The reports include recommendations on resource allocation and prioritization. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence had provided two such reports as of December 2023.[47]

To date, USCTOC has produced three strategic plans aimed at countering transnational organized crime in specific regions, with one plan focused on countering such crime in Haiti.[48] In the Haiti strategy, it made 21 recommendations to the U.S. government, organized into three lines of effort: (1) investigative actions or judicial outcomes, (2) non-judicial deterrence outcomes, and (3) near-term enhancement of law enforcement posture. One such recommendation stated that the counter-transnational organized crime community should surge intelligence to map Haitian illicit financial networks, with particular emphasis on where within the U.S. financial system the proceeds of crime reside.

In addition to the strategic plans, USCTOC developed a national prioritized list of 71 priority transnational organized crime activities (called “harm activities”) and 62 transnational organized crime networks (also referred to as “actors”) based on the risk they pose to national security. In 2024, USCTOC further refined this list to identify the top transnational organized crime activities and actors.[49]

Task Force KleptoCapture

Established in 2022, Task Force KleptoCapture is an interagency law enforcement task force. It is dedicated to enforcing sanctions, export restrictions, and economic countermeasures that the U.S., along with allies and partners, has imposed in response to Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine and other malign activity. According to DOJ, the mission of the Task Force includes the following activities:

· Investigating and prosecuting violations of sanctions imposed in response to the Ukraine invasion, as well as sanctions imposed for prior instances of Russian aggression and corruption

· Combating unlawful efforts to undermine financial institutions’ record-keeping and reporting obligations, including the prosecution of those who try to evade know-your-customer and anti-money laundering measures[50]

· Targeting efforts to use cryptocurrency to evade U.S. sanctions, launder proceeds of foreign corruption, or evade U.S. responses to Russian military aggression

· Using civil and criminal asset forfeiture authorities to seize and forfeit assets belonging to sanctioned individuals or assets identified as the proceeds of unlawful conduct

The Task Force is authorized to investigate and prosecute any criminal offense related to its mission, including conspiracy to defraud the United States by interfering in and obstructing lawful government functions, money laundering, or other offenses. Task Force officials said actions taken to fulfill its mission are dependent on the outcomes of investigations and are often subject to contested litigation.

According to DOJ, as of February 2024, Task Force KleptoCapture has restrained, seized, and obtained judgments to forfeit nearly $700 million in assets from Russian oligarchs and enablers. Further, they reported charging more than 70 individuals and five corporate entities accused of sanctions evasion, export control violations, money laundering, and other crimes—and arrested more than 30 defendants worldwide.

Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force

Established in 2022, the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs (REPO) Task Force is a transatlantic task force that works to ensure the effective implementation of financial sanctions by identifying and freezing the assets of sanctioned individuals and companies that exist within member states’ jurisdictions.[51] The Task Force was formed to find, restrain, freeze, seize, and, where appropriate, confiscate or forfeit the assets of those individuals and entities that have been sanctioned in connection with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the continuing aggression of the Russian regime. According to Treasury officials, the U.S. government is represented on the multilateral REPO Task Force by both the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Treasury, meaning that DOJ and Treasury share lead on REPO Task Force matters. REPO Task Force officials said the Task Force does not measure success in terms of the number of targets or actions but rather the extent to which it has served as a vehicle for members to coordinate efforts. According to Treasury officials, the REPO Task Force continues to leverage financial intelligence, law enforcement information, joint investigations, and the assistance of the private sector to deny Russia access to the revenue streams and economic resources used to wage its war on Ukraine.

In 2023, the REPO Task Force issued a press release that described various achievements since it was established. For example, the REPO Task Force reported that it had blocked or frozen more than $58 billion worth of sanctioned Russian individuals’ assets in financial accounts and economic resources. It also reported ensuring that $300 billion in Russian Central Bank and Russian National Wealth Fund assets in REPO Task Force members’ jurisdictions remain immobilized.

The REPO Task Force has reported leading and coordinating sanctions enforcement efforts with international partners and counterparts, including detecting and fighting sanctions evasion through joint outreach. In March 2023, the REPO Task Force issued a global advisory on Russian sanctions evasion, which identified certain tactics and issued recommendations to mitigate the risk of exposure to continued evasion. Among these recommendations were ensuring compliance programs implement relevant AML/CFT laws and regulations and are regularly reviewed and taking part in existing public-private partnerships. Treasury officials said the recommendations are intended to be longstanding best practices to reduce sanction evasion. Treasury officials said the agency plans to continue working with the compliance community and related stakeholders to adopt and incorporate them.

Selected Strategies and Efforts Lack Performance Information Useful for Assessing Progress

Implementing strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activities requires federal entities to collaborate with one another to, for example, define outcomes, share information, and assess progress.

According to key practices for evidence-based policymaking, performance management activities help an organization define what it is trying to achieve, determine how well it is performing, and identify what it could do to improve results.[52] Specifically, performance management is a three-step process by which organizations (1) set goals to identify the results they seek to achieve, (2) collect performance information (a type of evidence) to measure progress, and (3) use that information to assess results and inform decisions to ensure further progress toward achieving those goals.[53] For example, performance data that an organization regularly collects and reviews can help determine whether performance goals were met and can help an organization assess progress toward its strategic goals and objectives.[54]

Further, according to leading practices for enhancing interagency collaboration, collaborative efforts between organizations benefit from defining common goals and outcomes. The organizations should then work together to define shared outcomes and goals that are agreed upon by participants. In addition, ensuring accountability of the collaborative effort by assessing its progress toward such defined outcomes is also a leading practice of effective interagency collaboration. This can be done by tracking and monitoring progress of the collaborative mechanism toward these outcomes.[55] If agencies do not use performance information and other types of evidence to assess progress toward outcomes, they may be at risk of failing to achieve their outcomes or show measurable progress toward achieving stated outcomes.

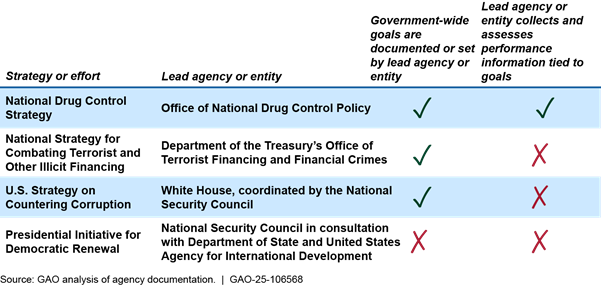

A number of federal agencies have taken steps to implement selected strategies and efforts to counter illicit finance activities. However, progress toward implementing some of the strategies and efforts cannot be measured because either the strategies and efforts do not have clearly defined goals, or agencies do not regularly collect and assess relevant performance information—or both. In addition, such performance information can help better manage fragmentation among federal agencies by clearly identifying key activities performed and provide opportunities for input and coordination with federal stakeholders.[56] Table 4 describes the extent to which the following strategies and effort, which are long-range, multiagency undertakings related to countering illicit finance activities, have established and defined performance information to be collected and assessed.

Table 4: Extent that Selected Federal Strategies and Efforts Related to Countering Illicit Finance Activities Have Goals and Performance Information is Collected

|

Strategy or effort |

Government-wide goals are documented or set by

lead |

Lead agency or entity collects |

|

National Drug Control Strategy |

✓ |

✓ |

|

National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing |

✓ |

✗ |

|

United States Strategy on Countering Corruption |

✓ |

✗ |

|

Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewalb |

✗ |

✗ |

Legend: ✓ = Yes; ✗ = No.

Source: GAO analysis of agency documentation and interviews with agency officials. | GAO‑25‑106568

Note: When discussing the strategies and efforts in this table, “lead agency or entity” refers to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Departments of State and Treasury, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the National Security Council and the White House.

aWe used the term “goals” to refer to a strategy or effort’s unique terminology for establishing desired performance levels.

bThe Initiative is an effort that defines areas of work for implementing agencies to focus their efforts.

National Drug Control Strategy

In December 2022, we reported that the 2022 National Drug Control Strategy fully met its statutory requirements related to comprehensive, long-range, quantifiable goals, and targets to accomplish those goals.[57] For example, the National Drug Control Strategy was accompanied by the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s (ONDCP) Performance Review System report, which assessed the federal government’s overall progress toward achieving the goals of the Strategy. Another document accompanying the Strategy was the National Drug Control Assessment, which is a summary of the progress of each National Drug Control Program agency’s efforts toward meeting the National Drug Control Strategy’s goals. The Assessment summarized agencies’ progress using specific performance measures developed and established pursuant to the Strategy.[58]

As stated earlier, in May 2024, ONDCP released its 2024 National Drug Control Strategy and 2024 National Drug Control Assessment, which include descriptions of the progress made toward each of the goals and objectives since the 2022 National Drug Control Strategy. As of November 2024, ONDCP had not yet released its 2024 Performance Review System report that accompanies the 2024 National Drug Control Strategy.

National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing

The 2024 Illicit Finance Strategy contains three high-level goals, four priorities (steps to achieve those goals), 15 supporting actions (to support the priorities) and over 120 benchmarks (which we refer to as “goals” for reporting purposes) for progress under each supporting action. Treasury and various other federal agencies are generally responsible for implementing the Illicit Finance Strategy.[59] Treasury’s Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes (TFFC) collects and summarizes actions that agencies have taken to implement the goals in the Illicit Finance Strategy. TFFC officials informed us that they collect this information primarily through formal and informal interaction with agency partners, as well as through participation in other interagency processes (including National Security Council (NSC) meetings and task forces) where countering illicit finance is discussed. The Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017 requires that the Illicit Finance Strategy include an assessment of current U.S. efforts to address the highest risks of illicit finance.[60]

While the 2024 Illicit Finance Strategy contains an appendix section that lists and summarizes some actions agencies have taken since the prior Strategy, it does not convey an assessment of whether or not these actions have fully or partially fulfilled the intent of each goal. This is in part because Treasury lacks information from participating agencies to do so. For example, one goal in the 2024 Illicit Finance Strategy is to develop indicators to assess AML/CFT technical assistance outcomes more systematically across the federal government. To help assess whether this goal was fully implemented, Treasury could gather relevant performance information from partner agencies to determine whether agencies are using such indicators. Furthermore, by conducting similar assessments across each goal in the Illicit Finance Strategy and aggregating its findings, Treasury could be better positioned to determine whether agencies have succeeded in fully implementing the supporting actions and four priority areas of the Illicit Finance Strategy.[61] Treasury officials also noted that goals (benchmarks) from the prior Illicit Finance Strategy that are considered to be fully addressed by the subsequent Illicit Finance Strategy are removed from the list of benchmarks in the later strategy. By removing or replacing these goals in subsequent strategies and not referencing them, Treasury may miss opportunities to determine or demonstrate overall progress in achieving what it set out to achieve in the current Illicit Finance Strategy.

Treasury officials told us they do not use a formal tracking mechanism to collect performance information on a regular basis. This could impact its ability to assess whether goals are being met. They further told us that Treasury does not have the authority to task other departments or agencies to formally report progress toward goals in the Illicit Finance Strategy. However, Treasury officials also said they would find value in developing a more formal process to obtain performance information related to agencies’ efforts to implement the Illicit Finance Strategy. They said this could include developing a quarterly process whereby they obtain more updates that would allow Treasury to regularly update a working document. Given that multiple agencies are tasked with supporting the implementation of the strategy, Treasury could benefit from working with relevant agencies to implement a process for collecting and assessing evidence on the extent to which agencies are achieving the goals outlined in the Illicit Finance Strategy. Doing so could help Treasury better assess the extent to which agencies are meeting goals.

United States Strategy on Countering Corruption

The 2021 United States Strategy on Countering Corruption (Strategy) contains 19 goals, or “strategic objectives,” including 76 lines of effort that federal agencies should take to support the goals.[62] Specific to curbing illicit finance, the Strategy contains two goals and 12 lines of effort. These goals are (1) addressing deficiencies in the anti-money laundering regime and (2) working with partners and allies to address these deficiencies.

According to the Strategy, the Biden-Harris Administration is to develop metrics to measure progress against each strategic objective, which will inform an annual report to the President. Federal departments and agencies, coordinated by the NSC and in consultation with the National Economic Council and Domestic Policy Council, are to report annually to the President on progress made against the Strategy’s goals. We learned that various agencies implementing the Strategy collect their own performance information independent of NSC, but no government-wide metrics to measure the extent to which progress is being made in implementing the overall strategy have been established or included in the annual reports to the President. For example:

· Some agencies are taking steps to implement the Strategy and collect their own performance information, absent guidance from NSC or specific government-wide target levels or metrics for success in the Strategy. For example, the State Department (State) has developed an implementation plan that includes activities it is taking to address the strategic objectives, broken into anticipated timelines and a description of successful “end states” for each activity.[63] Furthermore, agencies such as USAID and State use project-specific performance metrics to inform their assessments of progress on the Strategy. However, these and other agencies do not analyze—in consultation with NSC, the lead entity responsible for collecting and reporting progress information to the President—the extent to which agencies’ collective efforts overall are meeting the goals of the Strategy.

· Some agencies have cited a need for clearer goals or performance metrics in the Strategy. For example, State officials said they would defer to NSC on refining goals for agencies or establishing specific performance metrics, and that developing such metrics could be helpful to gauge progress on the Strategy in the aggregate. In addition, USAID officials said agencies are making progress on implementation, but challenges remain for monitoring and reporting progress against the broad goals in the Strategy, especially across agencies.

· Agencies have taken varied approaches to update NSC on efforts to implement the Strategy. According to DOJ and Treasury officials, they generally provide oral updates to NSC. Treasury officials said they work closely with NSC and other agency partners to advance the Strategy. DOJ officials informed us that there is no written process for reporting their progress. Furthermore, according to USAID officials, NSC initially developed an implementation tracker to collect quarterly updates from agencies about their efforts toward implementing the Strategy. This tracker included information, broken down by the five strategic pillars of the strategy, on ongoing and future actions and timelines for completing actions. USAID officials said NSC now solicits annual updates on highlights of agencies’ significant achievements in addressing the strategic pillars of the Strategy. While USAID has used these updates to provide information on its efforts, the updates, as well as the most recent annual fact sheet on implementation, do not indicate that performance metrics for the Strategy have been developed.

While NSC has submitted annual reports to the President in the form of fact sheets describing agencies’ efforts in implementing the Strategy, as discussed earlier, these reports do not contain metrics measuring progress against the goals. Including such metrics could help NSC and the implementing agencies better measure the extent to which progress is being made against each strategic objective outlined in the Strategy.

Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal

USAID and State, in collaboration with bilateral and multilateral partners, are the primary agencies responsible for leading the implementation of the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal’s (Initiative) programs.[64] Specifically, according to USAID officials, USAID and other agencies (mainly State) worked closely together to develop the Initiative and its five areas of work through an interagency policy coordination process led by NSC.

We learned that USAID and State generally developed documentation that describes their planning, development, partnering, and implementation of deliverables for individual programs under the Initiative. This includes tracking their own efforts to implement specific programs unique to USAID and State. In addition, USAID and State provide updates to NSC about their efforts to implement the programs. For example, in February 2024, USAID provided NSC with a written update for 13 programs that were organized under the Initiative’s Fighting Corruption area of work, among others. According to the update, USAID is the lead agency for six of the programs and collected status updates from State and Treasury, which are the lead agencies on the remaining seven programs.

However, neither USAID nor State, in collaboration with NSC, have defined joint, unifying performance goals or developed a method to collect and assess evidence that tracks the extent to which agencies are achieving the goals. For example, lead agencies could develop joint goals that apply to all 13 programs under the Fighting Corruption area of work, such as goals that define successful end states or establish key requirements related to performance. Furthermore, lead agencies could collect and assess relevant performance information tied to such goals, which could help provide insights into the extent to which agencies are improving on this area of work under the Initiative. USAID officials stated they would welcome NSC guidance on high level, joint (e.g., government-wide) outcomes it would like the agency to achieve under the Initiative.

Collecting and assessing such performance information could help agencies focus their efforts to implement various aspects of the Initiative and provide for an overall status of progress toward achieving established performance goals. By working with each other and with NSC to develop and establish joint performance goals, as well as a method to collect and assess performance information tied to them, USAID and State could improve their oversight and tracking of agencies’ progress in carrying out the Initiative and could better determine and assess the effectiveness of agencies’ efforts.

Selected Law Enforcement and Intelligence Groups Are Generally Collaborating to Counter Illicit Finance Activities

The law enforcement and intelligence collaborative groups we reviewed facilitate interagency collaboration to counter illicit finance activities. Collaborative group participants we met with (participants of the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) Fusion Center, the International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations Center (IOC-2), El Dorado Task Force New York, the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team, and Special Operations Division) reported their groups effectively collaborated with federal and foreign entities to counter illicit finance activities, in alignment with leading interagency collaboration practices.[65] These collaborative groups are not directly tied to the government-wide strategies and efforts discussed above, though their efforts may support activities in line with these strategies and efforts. As discussed earlier in this report, various federal agencies provide staff and resources to support these collaborative groups for the purpose of coordinating interagency law enforcement and intelligence activities. In addition, we found that these collaborative groups track outcomes of their activities and have agreements such as memoranda of understanding in place to govern their interactions.

Table 5 presents selected questions we asked participants of these groups and counts of the responses they provided. We presented interviewees’ responses on three of the leading collaboration practices for inclusion in table 5 to highlight some of the major substantive themes that emerged. For the complete list of questions and responses, see appendix V.

Table 5: Law Enforcement and Intelligence Collaborative Group Participants’ Responses to Selected GAO Questions on Implementation of Leading Interagency Collaboration Practices

|

Selected leading interagency collaboration practices |

Selected questions asked on implementation of interagency collaboration practices |

Very effectively |

Somewhat effectively |

Not applicable |

|

Ensure Accountability |

How effective do you believe your mechanism’s leadership is at ensuring outcomes or objectives are being reached? |

44 |

3 |

0 |

|

Bridge Organizational Cultures |

How effectively do you feel that staff from all agencies work together through this mechanism? |

46 |

1 |

0 |

|

Leverage Resources and Information |

How effective do you believe your mechanism is at providing you with tools, technologies, or other resources needed to conduct your duties? |

35 |

12 |

0 |

|

How well would you say information flows through your mechanism, both within the mechanism itself and to and from your agency? |

44 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

How effective would you say information sharing is with foreign partners, both inside and outside of your information sharing mechanism? |

32 |

5 |

10 |

Source: GAO analysis of comments from selected agency staff. | GAO‑25‑106568

Notes: We interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 46

supervisory and nonsupervisory staff from eight agencies involved in five law

enforcement and intelligence collaborative groups. (In addition to the six

agencies in our review—FBI, DEA, ICE-HSI, Secret Service, IRS-CI, and USPIS—we

also interviewed certain staff from OCDETF and Treasury due to the importance

of their roles in these collaborative groups). One interviewee provided two

sets of responses—one on behalf of each of two collaborative groups in which

this interviewee participates—resulting in a total of 47 sets of responses to

the interview questions. The interviewees included five El Dorado Task Force

participants, seven IOC-2 participants, seven Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet

Enforcement team participants, 17 OCDETF Fusion Center participants, and 11

Special Operations Division participants. Some interviewees explained that

certain questions were not applicable to them in their specific roles, so we

recorded their responses as “Not applicable.” We asked one or more questions

related to all eight categories of leading interagency collaboration practices

identified by GAO in Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to

Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges. GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington,

D.C.: May 24, 2023). The eight categories are: define common outcomes, ensure

accountability, bridge organizational cultures, identify and sustain

leadership, clarify roles and responsibilities, include relevant participants,

leverage resources and information, and develop and update written guidance and

agreements. Appendix V presents a full summary of these interview responses.

Response categories for these selected questions included 5-point Likert scales

regarding effectiveness (very effective, somewhat effective, neither effective

nor ineffective, somewhat ineffective, or very ineffective). Since no

interviewees provided any of the latter three responses, we present the first

two response options (very or somewhat effective) in the table. See appendix I

for more details on our methodology.

|

Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) Fusion Center and International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations Center (IOC-2) Use of Intelligence Product Surveys. OCEDTF Fusion Center and IOC-2—which both prepare and disseminate intelligence products for field agents—determine the effectiveness of these products through surveys attached to the products. These surveys ask product requestors and recipients four to seven questions about topics such as how well products were tailored to their needs, how satisfied they were with the response, and how they would rate overall product quality. Based on information provided by OCDETF Fusion Center, in the first quarter of fiscal year 2024, 95 percent of the requestors responding to these evaluation forms rated the products as good to great, and the forms had a response rate of about 24 percent. The response rate for these forms has increased from a response rate of 6.5 percent in fiscal year 2020. OCDETF officials told us they believe voluntary responses to these feedback forms are more reliable than mandatory responses would be. Source: OCDETF. | GAO‑25‑106568 |

The following conveys insights and illustrative examples interviewees provided in the areas of ensuring accountability, bridging organizational cultures, and leveraging resources and information in their collaborative groups.[66]

Ensure Accountability. GAO has reported that when collaborating entities ensure accountability, such as by communicating progress toward short- and long-term outcomes, they are better able to encourage participation, assess progress, and make necessary changes.[67] Almost all 46 collaborative group interviewees responded that leadership was very effective at ensuring achievement of identified outcomes or objectives. Twelve interviewees from four collaborative groups (OCDETF Fusion Center, El Dorado Task Force, the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team, and Special Operations Division) described how their group’s leadership contributed to effective collaboration and communication with various agencies that comprise the group. For example, one interviewee from El Dorado Task Force said their leadership worked effectively to set objectives and outcomes by maintaining partnerships and relationships with participating agencies.

In addition, four interviewees from the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team noted benefits of open communication for achieving outcomes. For instance, one interviewee said leadership and program managers worked together to solve problems and develop a vision for the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team, as its role had evolved over time. According to one official from the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team, the team ensured accountability by leveraging each agency’s unique authority and operational culture because the team offered a good platform for dealing with certain offices that may have different relationships among headquarters or task force components.

Three interviewees within OCDETF Fusion Center stated that its Strategic Management Team—consisting of unit and section chiefs—regularly discussed its process improvements and concerns. Table 6 below provides information on the key outcomes agency officials identified for each collaborative group.

Table 6: Key Outcomes Reported by Selected Participants of Collaborative Groups Involved in Combating Illicit Finance

|

Collaborative group |

Key outcomes |

|

Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) Fusion Center |

In fiscal year 2023, OCDETF Fusion Center reported that it disseminated a total of 14,123 intelligence products prepared by participating analysts. These products were disseminated to 46,675 law enforcement personnel in the United States and internationally. Of these products, OCDETF Fusion Center reported that 4,141 were created by OCDETF Fusion Center intelligence analysts and disseminated to 36,693 law enforcement personnel.a See sidebar for additional information about these intelligence product disseminations. |

|

International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations Center (IOC-2) |

In fiscal year 2023, IOC-2 produced 766 intelligence products that it disseminated to 6,079 law enforcement partners.a See sidebar for additional information about these intelligence product disseminations. |

|

El Dorado Task Force |

El Dorado Task Force New York reported that in fiscal year 2023, its operations resulted in 101 criminal arrests, 79 indictments, 52 convictions, 57 disruptions and 39 dismantlements of criminal organizations, seizures of $53.3 million and 532 pounds of drugs, and 10 seizures of arms, ammunition, or explosives. |

|

Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team |

The Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team issues press releases with statistics about its larger joint operations. For instance, in May 2023, it announced an operation with results that included 288 arrests as well as seizures of 117 firearms, 850 kilograms of drugs, and $53.4 million in cash and virtual currencies.b |

|

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Special Operations Division |