RED HILL FUEL STORAGE

DOD’s Contract Approaches and Oversight before and after the 2021 Fuel Leaks

Report to Congressional Requesters

November 2024

GAO-25-106572

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106572. For more information, contact Travis J. Masters at (202) 512-4841 or masterst@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106572, a report to congressional requesters

November 2024

red hill Fuel Storage

DOD’s Contract Approaches and Oversight before and after the 2021 Fuel Leaks

Why GAO Did This Study

In May 2021 and November 2021, Navy personnel accidentally caused two fuel leaks at Red Hill, according to a Navy investigation. These leaks contaminated drinking water for 93,000 service members and the local community. In November 2022—after DOD announced the closure of Red Hill earlier that year—contractor personnel accidentally caused 1,300 gallons of hazardous firefighting foam concentrate to release within the facility and surrounding environment, according to a DOD investigation.

GAO was asked to review the contracts related to Red Hill’s operations. This report describes (1) the roles that DOD and its contractors performed in the operations, maintenance, and repair of Red Hill; (2) how the contracts changed, if at all, after the 2021 leaks; and (3) the oversight mechanisms DOD used to monitor contractor performance on selected contracts for Red Hill.

To conduct this work, GAO selected 16 contracts for review—10 that were active at the time of the 2021 leaks based on federal procurement data from fiscal years 2014–2022 and six that were awarded in fiscal years 2022–2023 after the leaks. GAO reviewed contract files and Navy investigation reports, conducted a site visit to Red Hill, and met with DOD officials, contractors, and the local community. DOD provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

What GAO Found

Fuel leaks and the release of hazardous firefighting foam concentrate at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Red Hill) in Hawaii raised questions about the role contractors played and Navy’s oversight of them. The Department of Defense (DOD) managed Red Hill—a government-run facility—through a complex structure with several DOD organizations and multiple contractors performing essential maintenance and repair activities.

GAO found that the Navy changed its contracting approach after the fuel leaks. Specifically, eight of the 10 contracts GAO reviewed that were awarded before the 2021 fuel leaks were competitively awarded. After the 2021 fuel leaks, the Navy awarded all six of the contracts GAO reviewed noncompetitively, in part to address urgent safety or environmental concerns, improve facility operations, and identify needed maintenance and repairs. After DOD decided to close Red Hill, DOD shifted its focus to completing the repairs needed to defuel and ultimately close the facility, as currently planned, in June 2028.

DOD oversaw its contractors using various mechanisms, such as unscheduled site visits. After a contractor unintentionally released a hazardous firefighting substance in November 2022, the Navy took additional steps to address the situation. For example, the contractor was not allowed back on-site, with some exceptions. When the contract expired, the Navy awarded a new contract to a small business owned by a Native-Hawaiian Organization that was familiar with the Red Hill facility.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

|

AFFF |

aqueous film-forming foam |

|

CPARS |

contractor performance assessment reporting system |

|

DFSP |

defense fuel support point |

|

DLA |

Defense Logistics Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FLC |

Fleet Logistics Center |

|

Joint Task Force |

Joint Task Force - Red Hill |

|

NAVFAC |

Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command |

|

NAVFAC EXWC |

Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command’s Engineering and Expeditionary Warfare Center |

|

NAVSUP |

Naval Supply Systems Command |

|

PFAS |

per and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

|

Red Hill |

Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility |

|

USACE |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

November 4, 2024

The Honorable Mazie K. Hirono

Chair

Subcommittee on Readiness and Management Support

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Kevin Cramer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Seapower

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Red Hill), located on the island of O’ahu in Hawaii, was a significant fuel reserve for ships and aircraft in the United States Indo-Pacific region. On March 7, 2022, the Department of Defense (DOD) announced its decision to permanently shut down Red Hill. This decision followed two leaks at the facility in May 2021 and November 2021, respectively, that leaked an unknown amount of fuel into the Red Hill shaft, which thereby contaminated the water. Up to 5,500 gallons of fuel was unrecovered from the release. The Red Hill shaft supplied drinking water to about 93,000 service members, their families, and the local community. The Navy investigated the 2021 fuel leaks and found that human error was a primary cause in both incidents.[1] The Navy also identified other contributing factors related to the facility’s operations, such as material deficiencies and poor training and supervision of government personnel. A year after the second leak, in November 2022, an estimated 1,300 gallons of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) concentrate—a hazardous material used in the fire suppression system at Red Hill—were released within the facility and in the surrounding environment during a routine maintenance operation. DOD investigated and found that, among other things, a contractor improperly installed an air vacuum valve to the AFFF system.[2]

Both the fuel leaks and the AFFF concentrate release have raised questions about what role, if any, that contractors had in the operations, maintenance, and repair of Red Hill and the Navy’s oversight of its contractors. You asked us to review the contracts related to operations at Red Hill following the 2021 fuel leaks. This report examines (1) the roles that DOD and its contractors performed in the operations, maintenance, and repair of Red Hill and whether selected contract awards were competed; (2) how contracts for operations, maintenance, and repair activities changed, if at all, after the 2021 fuel leaks; and (3) the oversight mechanisms DOD used to monitor contractor performance on the selected contracts for Red Hill.

To address the first objective, we reviewed the Navy’s investigation reports; documentation that defined organizational roles and responsibilities—such as memorandums of agreement; and emergency orders to identify which organizations awarded or administered contracts for the facility at the time of the May 2021 and November 2021 fuel leaks. We selected 10 contracts for review—using data from the Federal Procurement Data System and discussions with DOD officials—that were the primary contracts for operations, maintenance, and repair activities and were active at the time of the 2021 leaks.[3] To determine whether selected contracts were awarded competitively, we analyzed contract file documentation—including solicitations and source selection decision documentation—to identify which competitive procedures and evaluation factors DOD organizations used to award contracts. We interviewed DOD officials, including those from the Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC), the Naval Supply Systems Command (NAVSUP), the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), as well as representatives from seven companies whose contracts we selected for review. We conducted a site visit to Red Hill in May 2023 to observe the facility and met with officials from DOD organizations that had defined responsibilities at Red Hill or awarded and administered selected contracts. Appendix I provides additional details about the contracts we selected.

To address the second objective, we reviewed investigation reports and other documentation, such as operations orders, to identify what changes DOD and the Navy determined needed to be made at Red Hill following the 2021 fuel leaks. We also examined DOD documentation to identify the agency’s decision to ultimately close Red Hill. We selected an additional six contracts awarded after the fuel leaks and reviewed contract file documentation to identify the goods and services that were purchased and whether the contract awards were competed. We interviewed DOD officials, including those from NAVFAC, NAVSUP, DLA, USACE, and Joint Task Force - Red Hill (Joint Task Force) to discuss any changes that DOD made to operations, maintenance, and repair activities after the 2021 leaks, as well as the plan for defueling of the tanks. During our site visit to Red Hill, we met with local organizations to obtain their perspectives on the fuel leaks and their concerns related to the facility, including any related to DOD’s contracting practices.

To address the third objective, we analyzed contract file documentation, including monthly status reports, and interviewed officials, including contracting officers’ representatives, from NAVFAC, NAVSUP, DLA, and USACE. We also interviewed representatives from selected contractors to discuss the oversight for the 16 selected contracts in our review. Appendix II provides additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

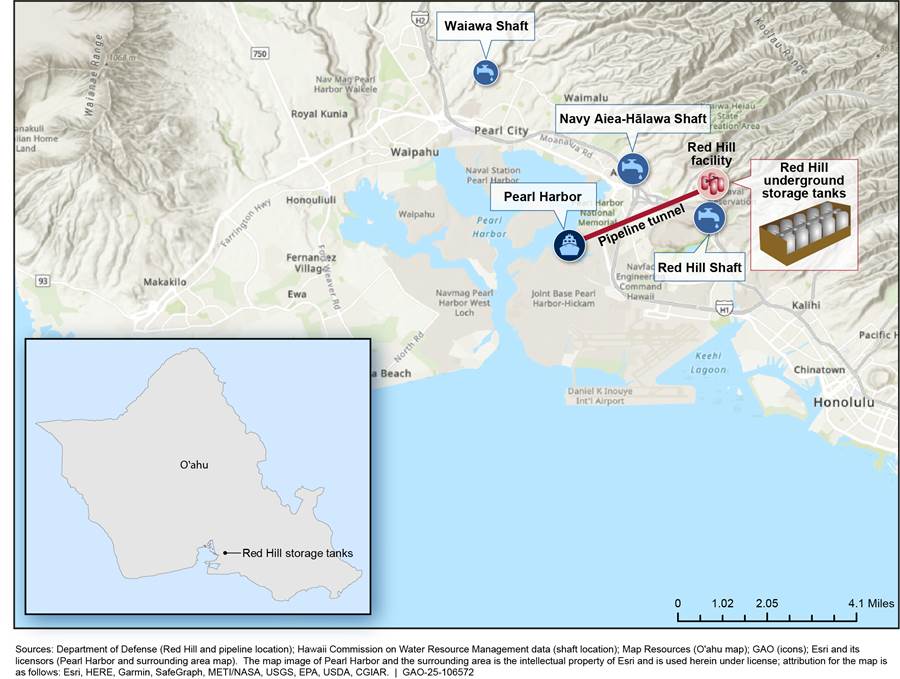

Background

Defense Fuel Support Point (DFSP) Pearl Harbor is a government-owned, government-operated facility on the island of O’ahu in Hawaii that includes the Red Hill facility, two aboveground tank facilities, a fuel oil recovery facility, an underground pump house, and Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam fuel distribution network.[4] The Red Hill facility consists of 20 underground tanks that can each hold approximately 12.5 million gallons of fuel. These tanks are located approximately 100 to 130 feet above the groundwater that serves as a drinking water source for several public water systems, largely those that support Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam and the greater Honolulu area. Figure 1 depicts the Navy’s nearby drinking water wells (shafts).

A series of key events took place between the first fuel leak in May 2021 and March 2024, when over 60,000 gallons of residual fuel was removed from Red Hill. Those events included a second fuel leak in November 2021, the accidental release of AFFF concentrate in November 2022, and several actions taken by DOD and the Navy to address the issues and ultimately defuel Red Hill.[5] Figure 2 provides additional insights into these events.

Before the 2021 Fuel Leaks, Red Hill Operated under a Complex Structure, Including Relying on Contractors for Essential Services

DOD used a decentralized structure that, in part, relied on a complex and interconnected set of roles and responsibilities to manage the operations, maintenance, and repair activities at Red Hill. Prior to the 2021 leaks, contractors also played an essential role in the maintenance and repair of equipment. DOD generally awarded contracts competitively to obtain those services.

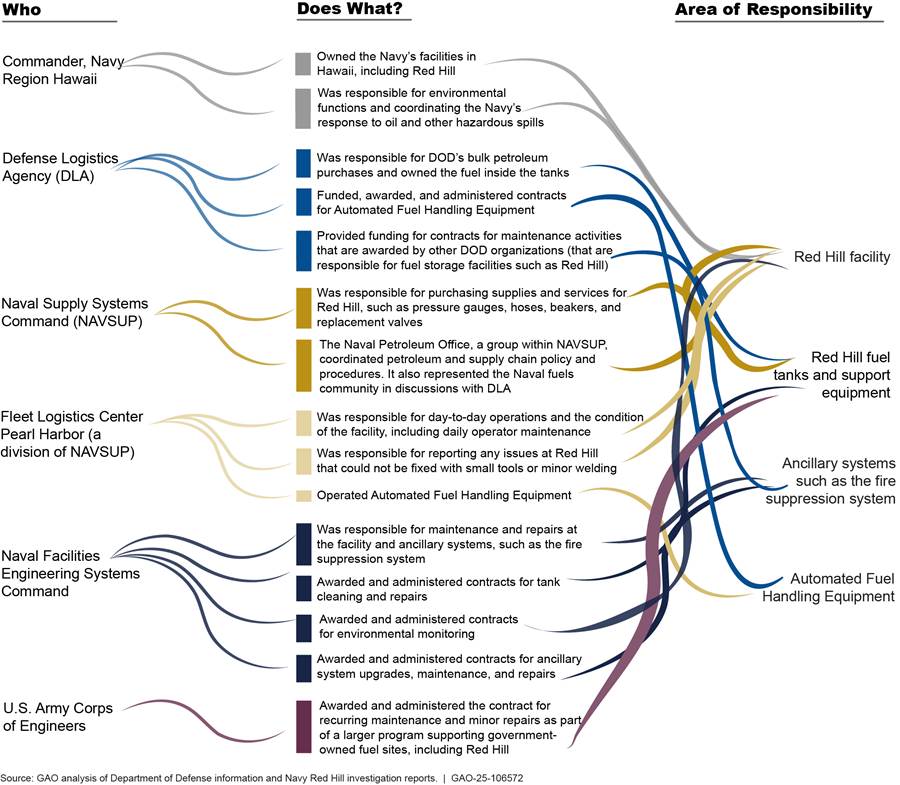

Several DOD Organizations Played a Role in Red Hill Operations, Maintenance, and Repair

Leading up to the 2021 fuel leaks, the Navy managed Red Hill operations, maintenance, and repair activities with support from DLA, using a decentralized set of roles and responsibilities. The Navy’s Fleet Logistics Center (FLC) Pearl Harbor was responsible for the day-to-day operations at the facility and relied on a workforce primarily comprised of government civilian personnel.[6] Other organizations within the Navy had responsibilities for other aspects of the facility, including awarding and administering contracts for maintenance and repair services. Figure 3 illustrates the different organizations that had roles at Red Hill and describes their responsibilities at the facility.

Note: At the time of the 2021 fuel leaks, DLA served as the executive agent for bulk petroleum. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 included a provision establishing that the U.S. Transportation Command would be the element responsible for DOD’s global bulk fuel management and delivery. See Pub. L. No. 117-81, 352(a)(1)(2021) (codified at 10 U.S.C. 2927). DLA became the integrated material manager for bulk petroleum and is responsible for coordinating the planning, purchasing, and storage of the fuel.

The decentralized structure at Red Hill necessitated careful coordination, communication, and management of responsibilities and relationships. For example, officials from DLA stated that they were not involved in the day-to-day operations at Red Hill—even though DLA owned the fuel that was stored at the facility—unless fuel was being delivered, at which point they would coordinate with FLC Pearl Harbor. Similarly, according to FLC Pearl Harbor and DLA officials, civilian operators were responsible for performing some minor maintenance at the facility, such as lubricating valves, painting, and minor welding. However, FLC Pearl Harbor officials stated that, although their organization was responsible for operating the facility, FLC Pearl Harbor was not responsible for larger maintenance or repair of the fuel tanks or the facility itself, which was under NAVFAC’s responsibility. In addition, NAVFAC was responsible for environmental monitoring—including groundwater and soil vapor—at the facility, although the Commander, Navy Region Hawaii, was responsible for responding to oil and other hazardous spills.[7] The Navy’s investigation found that Red Hill had a complex command structure that, at the time of the leaks, had devolved into “management by committee” with blurred lines of responsibility, authority, and accountability.[8]

Adding to the interconnectedness, the organization that funded the contracts could be different than the organization that awarded and administered the contracts. For example, DLA officials stated that the Navy owned and operated the facilities and infrastructure at Red Hill, but that DLA owned the fuel that was stored there. As a result, DLA provided funding to Navy organizations—such as NAVFAC—to award and administer contracts for maintenance and repair services at the facility. DLA officials also stated that they provided funding for environmental monitoring that occurred at the facility, but the contracts were awarded and administered by NAVFAC.

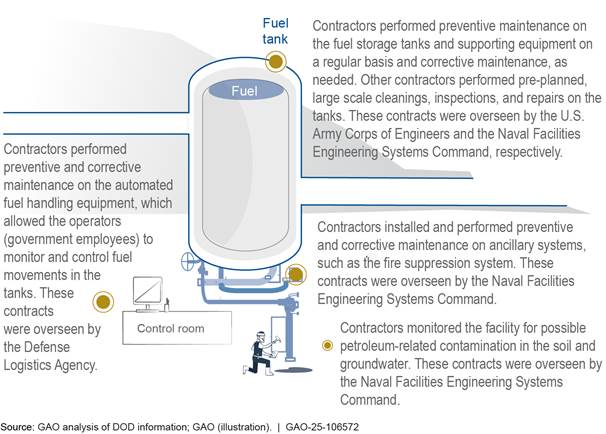

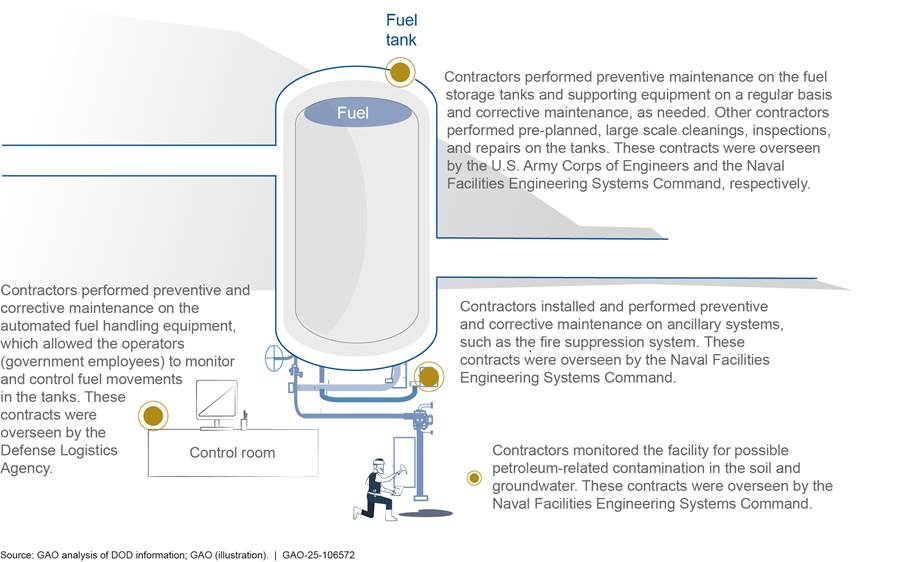

Multiple Contractors Provided Various Maintenance and Repair Services

Leading up to the 2021 fuel leaks, contractors performed key roles in maintaining and repairing equipment at Red Hill. Contractors were responsible for performing preventative maintenance and corrective repairs on the fuel tanks, pipelines, supporting equipment and systems, as well as monitoring services. In the 10 contracts active at the time of the leaks that we selected for review, the types of tasks that contractors performed included:

· Environmental monitoring. Long-term soil and water monitoring for any petroleum contamination and development of an implementation plan and cost estimate for investigation and remediation of releases and groundwater protections.

· Fire suppression system upgrades and maintenance. Updates to and maintenance of fire suppression and ventilation systems.

· Tank repair and maintenance. Clean, inspect, and repair services for three of the 20 tanks in Red Hill.[9] Corrective maintenance and repairs on tanks and supporting equipment identified by the inspection.

· Automated fuel handling equipment maintenance. Maintenance of automated fuel handling equipment. This equipment provided fuel operators with visibility of the fuel infrastructure and controlled the motor-operated functions used to move fuel from one point to another. It also included equipment, such as various sensors including pressure-indicating and temperature sensors.

The type of maintenance or repair activity determined which contract and, subsequently, which contractor was responsible for performing work at the facility. Figure 4 illustrates the different contractors who performed work on fuel tanks at the facility and the associated DOD organization responsible for administering the contract, based on the contracts we reviewed.

DOD officials and contractor representatives stated that contractors were on-site daily (i.e., Monday through Friday) at Red Hill performing various tasks and services under their respective contracts. The contracts we selected for review, at times, outlined specific tasks and associated time frames for preventative maintenance and equipment inspections. For example, DLA officials stated that the contractor’s maintenance schedule for the automated fuel handling equipment included weekly, monthly, semiannual and annual inspections of the equipment.

Because contractors had a key role in carrying out maintenance and repair activities—and the type of activity determined which DOD organization and contract was involved—the process for coordinating, reporting, and assigning repairs was also complex.

Coordinating Repairs

Scheduling maintenance and repair work required ongoing coordination and communication between the different organizations with responsibilities at Red Hill. For example, NAVFAC officials stated that they would coordinate with FLC Pearl Harbor to determine which tanks could be taken out of service for cleaning, inspection, and repair work without interrupting operations. NAVFAC officials stated that coordination and communication with FLC Pearl Harbor was critical for scheduling work at Red Hill. Similarly, the organizations also coordinated to approve more substantial repairs. NAVFAC officials stated that, after inspecting the fuel tanks, the contractor would submit a report that outlined any issues identified during inspections. NAVFAC, FLC Pearl Harbor, and DLA would review the report and recommendations and authorize required repairs to return the tanks to service. The group would collectively approve other recommended repairs or improvements. In the event of a disagreement, the organizations would meet to determine the source of the disagreement and reach resolution. Once the repairs were approved, NAVFAC would modify or issue a task order for the work.

Reporting Corrective Repairs

According to DOD officials, if any issues were identified by contractors during routine maintenance checks or by FLC Pearl Harbor operators, the requests for any corrective repairs were submitted to various organizations within DOD, depending on the type of activity, for approval and assignment. Contractors were responsible for reporting any identified issues to the DOD organization responsible for administering their respective contract and may also be responsible for addressing the issue. For example, DLA officials stated that a technician from the contractor responsible for maintaining the automated fuel handling equipment would address an issue if within the scope of their respective contract. Other DOD officials noted that, if a corrective issue was beyond the scope of a contractor’s respective contract, a DOD official would notify the organization responsible for the repair and pass the issue along to address it. However, corrective repairs could be reported through more informal communications as well. A FLC Pearl Harbor official explained that the fuel operators maintained a good relationship with the contractors at the facility and the operators would often informally learn about issues that the contractors identified during their work.

Assigning of Repairs

For certain repair and maintenance activities, it could take time to assign or start the needed work at Red Hill. For example, contractor representatives stated that requests for repair work had to be adjudicated by the different government organizations at Red Hill to determine which organization had responsibility for the specific task. At times, those various organizations could take weeks to complete that process and assign the work, according to contractor representatives. In other instances, the nature of the work itself required considerable time. For example, NAVFAC awarded a task order to clean, inspect, and repair specific tanks. NAVFAC officials explained that it could take up to 6 months to obtain the proper clearances for the contractors, the cleaning tasks would take about 2 months, and the design work for any repairs would take between 6 and 8 months to complete, with the contractor on-site every day.

DOD Generally Used Competition and a Variety of Evaluation Factors to Award Contracts

We reviewed 10 contracts that DOD awarded prior to the fuel leaks, eight of which were awarded competitively and two noncompetitively.[10] DOD awarded five of the eight competed contracts using full and open competition.[11] To award the remaining three competitive contracts, DOD used a process that limited competition to certain sources, such as small businesses or used simplified procedures.[12] DOD awarded two noncompetitive contracts on the basis that only one responsible source could meet DOD’s requirements.[13] One of the noncompetitively awarded contracts was a bridge contract awarded in 2019 that provided the continuation of maintenance services and allowed DLA additional time to solicit and competitively award a follow-on contract for the work.[14]

For the eight competitively awarded contracts, DOD used a variety of evaluation factors in making its award decision, such as:

· recent, relevant experience;

· past performance on recent, relevant projects;

· personnel experiences and professional qualifications, such as engineering certifications;

· price;

· safety;

· small business utilization; and

· schedule.

Of the contracts we reviewed, DOD generally used common processes to evaluate the proposals. For example, the Navy awarded one contract to the company that offered the lowest price after it met or exceeded the acceptability standards for certain technical factors. Those factors included past performance, experience and qualifications, safety, and schedule.[15] In another example, the Navy awarded a contract to a company that it determined to be the best value to the government after assessing technical approach, schedule, past performance, and price.[16]

After the Leaks, the Navy Awarded Contracts Noncompetitively to Obtain Needed Services

In contrast to the contracts awarded before the leaks, the Navy used noncompetitive contracting procedures and quickly awarded contracts after the fuel leaks. The Navy intended for these contracts to improve facility operations and identify needed maintenance and repair activities for the continued operation of the facility. After the Secretary of Defense announced plans to permanently close Red Hill, DOD shifted its focus to completing the repairs needed to safely defuel and shut down the facility.[17]

We reviewed six contracts that the Navy awarded after the 2021 leaks, all of which were awarded noncompetitively. Specifically,

· The Navy awarded four sole-source contracts through the Small Business Administration’s 8(a) program to tribally-owned small businesses, which generally can receive noncompetitive contracts for any dollar amount.[18]

· The Navy awarded the remaining two contracts using the justification that the need for services was urgent.

· One was a task order to perform an assessment of the fuel pipelines and fire suppression systems at Red Hill under an existing contract.[19] The Navy had an urgent need to inspect and assess the pipeline system after the leaks. The Navy had paused all operations at Red Hill pending this assessment to assure the maximum safe use of Red Hill and fully address concerns as to potential impacts of the facility on public health.

· The remaining contract was for an independent assessment of design and operational deficiencies at Red Hill that could impact the environment. To ensure an independent and expeditious assessment, the Navy reached out to qualified companies with limited or no contracts with the Navy and asked them to develop proposals. Although the Navy received and evaluated three proposals, it awarded the contract noncompetitively to a company because of the urgency to start the work.[20] Ultimately, the company that received the award completed the work in about 3 months.

The types of tasks that contractors performed under these contracts included:

· Third-party, independent assessments and repair identification. Independent assessments for the condition of the tanks, pipeline system, support equipment, and the fire suppression system at Red Hill, including a life-cycle sustainment plan. One contract, awarded prior to DOD’s decision to close the facility, required the contractors to assess the facility for two options—(1) to continue operations or (2) to close the facility.

· Support and improve facility operations procedures. Advisory and assistance services, including engineering and operations subject matter expertise, to support and improve the operation at DFSP Pearl Harbor, including Red Hill.

· Fire suppression system maintenance. Maintenance of fire suppression and ventilation systems.

· Repurposing survey. Services necessary to obtain public input regarding the potential benefits of repurposing Red Hill for the Navy’s consideration. Congress directed DOD to undertake this study to examine potential repurposing solutions for Red Hill, after the Secretary’s decision in March 2022 to permanently close the facility.[21] The Navy released the study in March 2024.[22] The study incorporated the local community’s views and preferences regarding repurposing Red Hill and found that the nature of the facility makes repurposing difficult. It also found that there are insufficient data to compare possible alternatives for reuse and concluded, based on the available data, that the most feasible option was not reusing the facility.

Similar to the contracts awarded before the 2021 leaks, the Navy used a variety of factors, such as price, past performance, and technical ability, to assess and select companies for noncompetitive contract awards. The Navy also considered other factors specific to Red Hill. For example, NAVFAC awarded the new contract for fire suppression system maintenance and repair to a contractor that was participating in the Small Business Administration’s 8(a) program and had recent, relevant experience. According to the Navy, this contractor was interested in the work and had the necessary experience to perform the requirements of the contract, including experience working at Red Hill. In another case, the Navy awarded a contract for supporting and improving facility operations procedures to a company after determining that the contractor had the highest degree of capability, technical expertise, and knowledge required to provide the services immediately. The Navy determined that the contractor’s partnership with another company that was already on-site at the facility would facilitate and accelerate the start of performance. The Navy also determined that the contractor and their partner had the most combined experience of the companies for which the Navy conducted market research, and the capability to begin shortly after the award was issued.

DOD Used a Mix of Oversight Mechanisms and Evaluation Reporting to Monitor, Address, and Document Contractor Performance Both before and after the 2021 Leaks

DOD used multiple mechanisms to conduct sustained oversight of the 16 contracts we selected for review. Various DOD components and the Joint Task Force had roles in conducting oversight of the contractors’ work at Red Hill. In addition, DOD used oversight mechanisms to take corrective action and document contractor performance when problems occurred, including in the contractor’s response to the AFFF concentrate release, and used evaluation reporting mechanisms to document contractor performance for future source selection purposes.

DOD conducted various forms of contract oversight. For the 16 selected contracts we reviewed—awarded both before and after the 2021 fuel leaks—provisions were included that DOD would conduct oversight using the practices identified in the contracts, such as unscheduled site visits, reviewing deliverables, and addressing complaints received from DOD personnel. For example, one contracting officer’s representative stated that she provided monthly assessments of the contractor’s work.[23] She stated that she was also on-site between eight and 20 times per month, depending on the task order itself or the number of unscheduled visits. DOD officials overseeing another contract stated that their local quality assurance personnel would regularly go on-site and report their findings back to the contracting officer’s representative, who was not located in Hawaii.

Various entities had roles in contract oversight. The establishment of the Joint Task Force to oversee the defueling of Red Hill increased contract oversight. However, DOD officials told us that quality assurance checks within the contract scopes remained the primary responsibility of the organization that awarded the contract, such as NAVFAC, along with the repair directorate of the Joint Task Force. The Joint Task Force brought more coordination and oversight of the activities and personnel on-site at Red Hill. For example, the Joint Task Force began requiring DOD personnel to regularly escort contractors throughout the facility and instituted the use of access control points and a list of authorized personnel at Red Hill to manage which contractors were on-site performing work.[24] Of the contractor representatives we interviewed, most stated that the DOD personnel providing oversight assisted in coordinating the contractors’ work with the schedules of other ongoing work at Red Hill and were available to answer questions as needed. For example, representatives from one contractor stated that the Navy’s contracting officer’s representative would, on a weekly basis, coordinate with the other contractors that would be on-site. The purpose of doing so, according to the representatives, was to ensure that the contractors could come and complete their work without interfering with one another.

In addition to DOD’s oversight, contractors generally maintained their own mechanisms for ensuring quality in the services that they performed. Each of the 16 contract files we reviewed included provisions about quality assurance mechanisms and maintaining appropriate documentation. For example, several contracts had provisions requiring contractors to maintain and share documentation with DOD such as accident prevention plans, health and safety plans, quality control plans, and daily quality control reports. One contractor reported that after the fuel leaks and AFFF concentrate release, the Navy increased oversight of how contractors implemented their own quality mechanisms to ensure quality in their work. For example, they told us the Navy reviewed and provided feedback on the contractor’s quality procedures.

Performance standards. Within the 16 selected contracts we reviewed, DOD included similar performance standards, such as submitting deliverables on schedule and submitting them as specified by the contract. In some instances, DOD included additional performance standards in the contracts. For example, the contract for the independent assessment required the contractor to actively identify, manage, and mitigate risks to Hawaiian cultural, economic, and environmental sensitivities. Navy personnel told us that the contractor addressed this requirement by identifying how to prevent a spill at all and whether or not the spill could harm Hawaiian interests. A quality assurance surveillance plan for another contract included performance standards that determined how much of the invoice the Navy would pay to the contractor based on how consistently the contractor performed routine actions and how quickly they addressed requests.

Examples of oversight at Red Hill. When DOD identified issues while administering the selected contracts we reviewed, they took action using contractual mechanisms to correct the problems. In one case, the Navy notified the contractor that they left plastic at a work site. In response, the contractor removed the plastic the same day they were notified and worked to identify methods to avoid making the same mistake again. In another case, one DOD organization issued a letter of concern to a contractor after they fell behind schedule on completing work. The contractor representatives stated that they engaged in conversations with DOD and determined that additional resources were needed. After three contractor staff were added to the work at Red Hill, contractor representatives stated that they were able to resolve the issue and maintain their schedule going forward. DOD considered this information when evaluating the contractor’s overall performance rating.

Evaluation reporting. DOD documented performance evaluations for the selected contracts through annual ratings in the contractor performance assessment reporting system (CPARS), an evaluation reporting tool for government contracts and orders.[25] DOD graded contractors in areas such as quality, cost control, and safety, often giving “satisfactory” ratings to contractors at Red Hill. DOD gave some contractors “very good” or “exceptional” ratings if they provided particularly good service. In one instance, DOD gave a contractor a very good rating for cost control because contractor staff made changes requested by the Navy and completed the scope of work on schedule without requesting additional funds. In some cases, DOD gave contractors “marginal” or “unsatisfactory” ratings to reflect issues they found.

The Navy’s response to the AFFF concentrate release. After the Joint Task Force determined that the cause of the November 2022 AFFF concentrate release was an air valve that the contractor had improperly installed, the Navy documented issues with the contractor related to management, quality, business relations, and safety. In addition, after the AFFF concentrate release, DOD officials stated that the Joint Task Force did not allow the contractor back on-site for the remainder of the contract period, except to perform maintenance on selected fire alarms. After the contract expired, the Navy issued a contract through the Small Business Administration’s 8(a) program to a Native Hawaiian Organization-owned small business that the Navy reported was familiar with the facility. The Navy competitively awarded a new contract for fire suppression system maintenance and repair in May 2024.[26]

In an April 2024 GAO report on the Navy’s efforts to address persistent chemicals at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, DOD officials stated that they responded to the AFFF concentrate release as required by DOD policy and the Navy Region Hawaii Integrated Contingency Plan.[27] Navy officials told us they used their in-house resources to clean up the AFFF concentrate release, despite the contractor having insurance to cover it, due to the scale of the spill and the need for quick action. Navy officials said they had a contract with a company for disposal, which they used, but that the Navy needed to use their own resources for reclamation, which included digging up asphalt and other technical operations. After the Joint Task Force completed their investigation, they recommended that the Navy undertake a review of possible contractor liability for the AFFF concentrate discharge.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Navy, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

Should you or your staff have questions, please contact me at (202) 512-4841 or masterst@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Travis J. Masters

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Table 1 describes the 16 contracts and orders that GAO selected for review. The Navy, the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) awarded these contracts for work at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Red Hill) before and after the May 2021 and November 2021 fuel leaks.

|

Fiscal year awarded |

Awarding organization |

Description of work |

Initial contract value (millions of dollars) |

Use of competitive procedures |

|

2015 |

Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC) Pacific |

Long-term monitoring of petroleum-related contamination in soil and groundwater at Red Hill |

$0.81 |

Compet

|

|

2015 |

NAVFAC Pacific |

Update and install fire suppression and ventilation system |

42.82 |

Compet

|

|

2016 |

NAVFAC Engineering and Expeditionary Warfare Center (EXWC) |

Clean, inspect, and repair and inspect repairs to storage tanks |

20.44 |

Compet

|

|

2018 |

NAVFAC Pacific |

Implementation plan and cost estimate for investigation and remediation of releases and groundwater protection and evaluation |

0.02 |

Compet

|

|

2018 |

NAVFAC Pacific |

Long-term monitoring of soil vapor and fuel product to monitor petroleum related contamination in soil at Red Hill |

0.41 |

Compet

|

|

2018 |

NAVFAC Hawaii |

Maintenance and repair of fire protection equipment and systems to ensure they are fully functional and in normal working condition |

10.33 |

Compet

|

|

2020 |

Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) |

Automated Fuel Handling Equipment maintenance |

9.57 |

Not compet

|

|

2021 |

NAVFAC Hawaii |

Clean, inspect, and repair and inspect repairs to storage tanks |

20.97 |

Not compet

|

|

2021 |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

Provide all required recurring maintenance and minor repairs services identified through a facility maintenance plan prepared by the contractor |

9.47 |

Compet

|

|

2022 |

DLA |

Interim support of Automated Fuel Handling Equipment maintenance with option periods to follow to maintain the overall period of performance |

0.40 |

Compet

|

|

Fuel leaks occur in May 2021 and November 2021, respectively |

||||

|

2022 |

NAVFAC EXWC |

Assess and report on the condition of the primary fuel pipelines, support equipment, and fire suppression system. Prepare a life-cycle sustainment plan, a brief on findings to respective Navy and DLA organizations, and an updated Integrity Management Plan Evaluation for the facility’s pipeline system |

2.96 |

Not compet

|

|

2022 |

Naval Supply Systems Command (NAVSUP) |

Conduct an assessment of Red Hill operations and system integrity to identify design and operational deficiencies that may impact the environment |

1.45 |

Not compet

|

|

2022 |

NAVSUP |

Advisory and assistance services that will provide engineering and operations subject matter experts to assist the government in data management, analysis strategies, management strategies, operations, process safety, and training to safely operate and manage Defense Fuel Support Point Pearl Harbor |

4.02 |

Not compet

|

|

2023 |

NAVFAC Hawaii |

Fire protection system maintenance and repair services for Red Hill, including fire alarm and detection systems, fire suppression systems, kitchen fire suppression systems, fire pumps, exterior ratio fire alarm reporting systems, and foam fire suppression systems |

2.47 |

Not compet

|

|

2023 |

NAVFAC Hawaii |

Provide all services necessary to allow the Navy to obtain public input regarding beneficial repurposing for Red Hill for the Navy’s nonbinding consideration |

0.53 |

Not compet

|

|

2023 |

NAVSUP |

Support services in (1) technical writing and knowledge management in regard to Red Hill; (2) developing reports and briefs for senior officials: (3) updating operations manuals; (4) providing written fuel facility maintenance assessments and proposing high-level facility modifications and improvements |

6.21 |

Not compet

|

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense information. I GAO‑25‑106572

This report examines contracting for operations, maintenance, and repair services at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Red Hill). Specifically, we assessed (1) the roles that the Department of Defense (DOD) and its contractors performed in the operations, maintenance, and repair of Red Hill and whether selected contract awards were competed; (2) how contracts for operations, maintenance, and repair activities changed, if at all, after the 2021 fuel leaks; and (3) the oversight mechanisms DOD used to monitor contractor performance on the selected contracts for Red Hill.

To assess the roles that DOD and its contractors performed at Red Hill, we reviewed documentation that defined organizational roles and responsibilities—such as memorandums of agreement, memorandums of understanding, and emergency orders—to identify which organizations had an active role at Red Hill. We reviewed the Navy’s investigation reports and other documentation to identify organizations that awarded or administered contracts at the facility and contractors that were performing work leading up to and at the time of the fuel leaks in 2021. To understand the organizational structure, including how roles and responsibilities for awarding, administering, and overseeing contracts are shared across DOD organizations at Red Hill, we interviewed DOD officials, including those from the Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC), Naval Supply Systems Command (NAVSUP), the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). We discussed with DOD officials the role contractors played, the types of goods and services provided, and the frequency of tasks. We conducted a site visit to Red Hill in May 2023 to observe the facility and met with officials from DOD organizations that had defined responsibilities at Red Hill or awarded and administered selected contracts.

To determine the goods and services that were provided by contractors and whether selected contract awards were competed, we selected 10 contracts for review. The contracts we reviewed were the primary contracts for operations, maintenance, and repair activities at Red Hill and were active at the time of the fuel leaks in May 2021 and November 2021, respectively. To determine which contracts to select for our review, we reviewed contract actions from the Federal Procurement Data System that included the term “Red Hill” and were awarded by a DOD organization from fiscal years 2014 through 2022. We requested lists of contracts that were active at the time of the 2021 fuel leaks from contracting officers during our initial meetings with DOD organizations who were responsible for operations, maintenance, and repair activities at Red Hill. During these initial meetings, we discussed with DOD officials which contracts were the primary contracts that were active at the time of the fuel leaks in 2021. We compared the lists of contracts we received from DOD officials and contracting officers with the original data we reviewed in Federal Procurement Data System. We selected an additional six contracts awarded after the leaks. We requested and reviewed contract file documentation to identify the goods and services purchased under the selected contracts for Red Hill. We analyzed contract file documentation, including justifications and approvals for the use of other than full and open competition, solicitations, source selection decision documentation, and business clearance memorandums to determine the extent to which the selected contract awards were competed and

identify the competitive procedures and evaluation factors that DOD organizations used to award contracts.[28] We interviewed contracting officers and contracting officer’s technical representatives from NAVFAC, NAVSUP, DLA, and USACE to discuss the development of contract requirements, competitive procedures, and processes for evaluating contract proposals.

To determine how contracts for operations, maintenance, and repair activities changed, if at all, after the 2021 fuel leaks, we reviewed investigation reports and other documentation, such as operations orders, to identify what changes DOD and the Navy determined they needed to make at Red Hill. We reviewed administrative and emergency orders issued by the Environmental Protection Agency and the State of Hawaii, Department of Health to determine what changes, if any, DOD made to the operation, maintenance, and repair activities after the 2021 fuel leaks. We examined DOD documentation to identify the agency’s decision to ultimately close Red Hill. We analyzed contract documentation for the six contracts that were awarded after the leaks, including solicitations, source selection decision documentation, and business clearance memorandums, to identify which, if any, competitive procedures and evaluation factors DOD used to award contracts. We interviewed officials from the NAVFAC, NAVSUP, DLA, USACE, and Joint Task Force - Red Hill to discuss the changes that DOD made to operations, repair, and maintenance activities after the May 2021 and November 2021 leaks as well as the plan for defueling of the tanks and closure of the facility. During our site visit to Hawaii, we met with two local organizations to obtain their perspectives on the May 2021 and November 2021 fuel leaks and concerns related to the facility or contractors.

To determine the oversight mechanisms DOD used to monitor contractor performance on the 16 selected contracts at Red Hill—awarded both prior to and after the May 2021 and November 2021 fuel leaks—we analyzed contract file documentation, such as quality assurance surveillance plans, performance of work statements, and monthly status reports. We interviewed officials, including contracting officers’ representatives, from NAVFAC, NAVSUP, DLA, and USACE to discuss the actions they took to oversee the contractors, including the types and frequency of their surveillance and how they identified problems or issues and how the contractors addressed them. We also interviewed representatives from seven contractors who were awarded 10 of the 16 contracts we reviewed. These contractors include contracts that were awarded by each DOD organization and contracts that were awarded both prior to and after the fuel leaks.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Travis J. Masters at (202) 512-4841 or masterst@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff members made key contributions to this report: Tatiana Winger, Assistant Director; Laura Durbin, Richard Catherina, Sabrina Riddick, Brittany Morey, and Robin Wilson. Other contributions were made by Vinayak Balasubramanian, Lorraine Ettaro, and Suellen Foth.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Department of Defense, U.S. Navy, Command Investigation Into the 6 May 2021 and 20 November 2021 Incidents at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Department of the Navy, Jan. 14, 2022); and Supplement to the Command Investigation into the 6 May 2021 and 20 November 2021 Incidents at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Department of the Navy, Apr. 15, 2022).

[2]Department of Defense, Command Investigation into the Facts and Circumstances Surrounding the Discharge of Aqueous Film Forming Foam that Occurred at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility on 29 November 2022. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Apr. 6, 2023).

[3]Our sample included contracts and orders under indefinite delivery contracts. For the purposes of this report, we refer to our sample collectively as contracts.

[4]DFSPs are assets overseen by DOD, contractors, or foreign governments that DLA and the military services use to store fuel. DFSPs are located on military bases, at contractor facilities, and on floating vessels across the world.

[5]We have also issued two earlier reports on issues related to the Red Hill incidents. In February 2024, we issued a report on DOD’s efforts to remediate Red Hill and the liabilities and costs to clean up and close the facility. GAO, Environmental Cleanup: DOD Should Communicate Future Costs for Red Hill Remediation and Closure, GAO‑24‑106185 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 14, 2024). In April 2024, we issued a report on DOD’s efforts to address per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—which is a substance found in AFFF—at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. GAO, Persistent Chemicals: Navy Efforts to Address PFAS at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, GAO‑24‑106812 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 15, 2024).

[6]See U.S. Navy Investigation reports from January and April 2022 related to incidents at Red Hill.

[7]See U.S. Navy Investigation reports from January and April 2022 related to incidents at Red Hill.

[8]U.S. Navy, Command Investigation into the 6 May 2021 and 20 November 2021 Incidents at Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility.

[9]According to DOD officials, contractors performed clean, inspect, and repair services on the tanks on a rotating basis and up to four tanks could be taken off-line at a time for service.

[10]By statute and under the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), agencies generally must use full and open competition when awarding contracts, unless an exception applies. 10 U.S.C. §3201-3208; 41 U.S.C. § 3301; FAR 6.101. Agencies generally must also provide fair opportunity for each awardee to be considered for certain task orders under multiple delivery-order contracts or multiple task-order contracts unless an exception applies. See FAR 16.505(b)(1). For more information on how we determined which contract awards were competed and not competed, see appendix II.

[11]See FAR 6.101. For more information on how we determined which contracts were awarded using full and open competition, see appendix II.

[12]See FAR 19.805-1(b)(2); DFARS 219.805-1(b)(2)(A) and FAR subpart 13.5. For more information on how we determined that contracts were awarded competitively using a process that limited competition to certain sources, or using simplified procedures, see appendix II.

[13]See FAR 6.302-1, 6.302-2 and FAR 16.505(b)(2). For more information on the exceptions to competition used in our sample, see appendix II.

[14]For more information on bridge contracts, see GAO, Sole Source Contracting: Defining and Tracking Bridge Contracts Would Help Agencies Manage Their Use, GAO‑16‑15 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 14, 2015).

[15]According to FAR 15.100, an agency can obtain best value in negotiated acquisitions by using any one or a combination of source selection approaches. In different types of acquisitions, the relative importance of cost or price may vary. The lowest price technically acceptable source selection process is appropriate when best value is expected to result from selection of the technically acceptable proposal with the lowest evaluated price. FAR-15.101-2

[16]The tradeoff source selection process is appropriate when it may be in the best interest of the government to consider award to other than the lowest priced offeror or other than the highest technically rated offeror. FAR 15.101-1.

[17]DFSP Pearl Harbor will remain open to support Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam and the Indo-Pacific region. According to the Navy’s current schedule, it plans to remove all pipelines and ancillary equipment from Red Hill by June 2028.

[18]The 8(a) Business Development Program of the Small Business Administration helps small businesses owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals and entities, such as federally- or state-recognized Indian tribes. 8(a) firms owned by Alaska Native Corporations, Indian Tribes, or Native Hawaiian Organizations (for DOD only) can receive sole-source contracts for any dollar amount, while other 8(a) firms generally must compete for contracts valued above certain thresholds. See FAR 19.805-1(b)(2); DFARS 219.805-1(b)(2)(A).

[19]A Petroleum, Oil and Lubricant Multiple Award Contract provides architect‐engineering services for petroleum, oil and lubricant systems worldwide. The exception to competition cited was FAR 16.505(b)(2)(i)(A).

[20]The exception to competition cited was FAR 13.501(a).

[21]James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-263, § 336 (2022).

[22]Stephen M. Worman, Alexis Levedahl, Brian Persons, Monika Cooper, Richard Guida, Robert Murphy, William Schmitt, Jackson Smith, Analysis of Alternative Uses for the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2024).

[23]The contracting officer’s representative is appointed by a contracting officer to monitor contract performance on their behalf.

[24]See U.S. Navy Investigation reports from January 2022 and April 2022 related to incidents at Red Hill.

[25]CPARS is a government-wide evaluation reporting tool for all past performance reports on contracts and orders. See FAR 42.1502. Past performance reports in CPARS reflect ratings and supporting narratives for various evaluation factors, including quality of products and services, management and business relations, and adherence to schedules. See FAR 42.1503(b)(1).

[26]The prior contract was awarded to a subsidiary of a Native Hawaiian Organization. The new contract was awarded to another subsidiary under the same Native Hawaiian Organization. For more information on federal contracting with tribally-owned entities, see GAO, Federal Contracting: Monitoring and Oversight of Tribal 8(a) Firms Need Attention, GAO‑12‑84 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 7, 2012).

[28]For the purposes of this report, competitive contracts include (1) contracts awarded using full and open competition procedures under Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) subpart 6.1; (2) contracts awarded using full and open competition procedures after exclusion of sources under FAR subpart 6.2; (3) contracts competed to the maximum extent practicable under FAR subpart 13.5 (using simplified procedures for certain commercial products and commercial services); (4) task orders awarded under a single-award indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract that was competitively awarded; (5) task orders awarded under a competitively awarded multiple award contract after fair opportunity was provided for contract awardees to compete for the task order (see FAR 16.505(b)(1)); and (6) task orders awarded under a General Services Administration Multiple Award Schedule (see FAR subpart 8.4).

Noncompetitive contracts include: (1) contracts awarded using other than full and open competition procedures under FAR subpart 6.3; (2) task orders awarded under a multiple award contract where fair opportunity was not provided for contract awardees to compete for the task order (see FAR 16.505(b)(2)); (3) contracts awarded on a sole-source basis using simplified acquisition procedures under FAR subpart 13.5 or through the Small Business Administration’s 8(a) program (see FAR 6.302-5(b)(4)).

For the purposes of this report, contracts awarded using full and open competition include (1) contracts awarded using full and open competition procedures under FAR subpart 6.1; (2) task orders awarded under a single-award indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract that was awarded using full and open competition procedures under FAR subpart 6.1; (3) task orders awarded under a multiple award contract that was awarded using full and open competition procedures under FAR subpart 6.1 after fair opportunity was provided for contract awardees to compete for the task order (see FAR 16.505(b)(1)); (4) task orders awarded under a General Services Administration Multiple Award Schedule and using the relevant competitive processes (see FAR subpart 8.4).

Contracts awarded competitively after exclusion of sources or using simplified procedures includes contracts that are set aside for competition among small businesses and contracts competed to the maximum extent practicable under FAR subpart 13.5.

For some noncompetitive contracts, the Justification and Approval memorandums for the use of other than full competition procedures cited title 10, section 2304(c)(1) of the U.S. Code (currently codified at title 10, section 3204(a)(1) of the U.S. Code), as implemented by FAR 6.302-1, as providing authority for the award. This provision allows agency heads to use procedures other than competitive procedures to award contracts when the property or services needed by the agency are available from only one responsible source or only from a limited number of responsible sources and no other type of property or services will satisfy the needs of the agency. The memorandum for one of the contracts also cited title 10, section 2304(c)(2) of the U.S. Code (currently codified at title 10, section 3204(a)(2) of the U.S. Code), as implemented by FAR 6.302-2, as providing authority for the award; this provision allows agency heads to use procedures other than competitive procedures to award contracts when an unusual and compelling urgency precludes full and open competition; and delaying a contract award would result in serious injury to the government. FAR 16.505(b)(2) contains provisions exempting contracting officers, under certain circumstances similar to those outlined in FAR 6.302-1 and FAR 6.302-2, from giving every multiple delivery-order or multiple task-order contract awardee a fair opportunity to be considered for a delivery or task order.