MILITARY OFFICER PERFORMANCE

Actions Needed to Fully Incorporate Performance Evaluation Key Practices

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106618

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106618. For more information, contact Kristy Williams at (404) 679-1893 or williamsk@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106618, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

Military Officer Performance

Actions Needed to Fully Incorporate Performance Evaluation Key Practices

Why GAO Did This Study

Military service performance evaluation systems provide necessary performance information for approximately 215,000 active duty commissioned officers across the Department of Defense (DOD). They also support decisions about officer promotions and placements. These decisions affect the composition and quality of the military’s current and future leadership.

Public Law 117-263 includes a provision for GAO to review the military services’ officer performance evaluation systems. This report examines (1) the extent the military services’ active duty officer performance evaluation systems incorporate key practices for performance evaluation, and (2) how officer performance evaluations inform promotion board determinations and support officer development.

GAO developed 11 key practices for performance evaluation; reviewed military service policies, manuals, forms, and other documentation; conducted nongeneralizable interviews with 19 promotion board members and 31 active duty officers; and interviewed DOD officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making a total of 20 recommendations, including that three services develop a training plan and align performance expectations with organizational goals; two services address communication of performance expectations and competencies and require feedback; and all four services develop a plan to evaluate their systems. DOD generally agreed with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

Out of 11 key practices for performance evaluation, all four military service systems fully incorporated the same five key practices and partially incorporated one key practice. The service systems varied in their implementation of the remaining five practices. Some fully incorporated the practices, some partially incorporated them, and most did not incorporate one practice.

Note: Fully incorporated: GAO found complete evidence that satisfied the key practice.

Partially incorporated: GAO found evidence that satisfied some portion of the key practice.

Not incorporated: GAO found no evidence that satisfied the key practice.

For example, GAO found that all four service systems fully incorporated the key practice that organizations should establish and communicate a clear purpose for the performance evaluation system by stating the purpose of their systems in relevant policies. In contrast, GAO found that three service systems did not incorporate the practice that organizations should align individual performance expectations with organizational goals because their systems’ policies neither align performance expectations with organizational goals nor direct rating officials to do so. By fully incorporating all 11 key practices, the services will have better assurance that their performance evaluation systems are designed, implemented, and regularly evaluated to ensure effectiveness.

The 19 promotion board members and 31 active duty officers GAO interviewed provided differing perspectives on the value of information in officer performance evaluation reports and on the extent to which reports support officer development. Promotion board members stated that evaluation reports provided sufficient information to inform their decisions about which officers to recommend for promotion. Some active duty officers stated that the reports provide a clear and relevant tool for assessing performance and supporting officer development. Conversely, others stated that factors such as misused or overused narrative may prevent a clear picture of officer performance areas in need of growth.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 13, 2024

Congressional Committees

Effectively evaluating the performance of active duty military officers and supporting officer development are essential to cultivating an officer corps with the requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities to lead the military of the future. To this end, the military services operate and oversee individual systems to evaluate the performance of approximately 215,000 active duty commissioned officers. The military services also provide promotion selection boards with performance information to support officer promotion and placement decisions.[1] These decisions carry important national security implications, affecting both the composition of the military and the quality of its current and future leadership.

According to military service policies, the services’ performance evaluation systems broadly serve two purposes.[2] The first purpose is to communicate performance standards and expectations and evaluate officer performance. The second purpose is to support personnel management decisions—such as selecting qualified personnel for promotion and command—by providing promotion board members with a long-term cumulative record of officer performance and potential. Within the Department of Defense (DOD), responsibilities for executing and overseeing the military services’ performance evaluation systems are dispersed across military department offices and service-specific personnel commands or centers.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for us to review the military services’ officer performance evaluation systems against best practices for performance evaluation, as well as the information provided to promotion boards and to officers as developmental feedback.[3] This report examines (1) the extent to which the military services’ active duty officer performance evaluation systems incorporate key practices for performance evaluation, and (2) how officer performance evaluations inform promotion board determinations and support officer development.

For our first objective, we developed 11 key practices for performance evaluation through a literature review of scholarly and peer-reviewed publications on performance evaluation and key practices used by public- and private-sector organizations. We assessed the military services’ officer performance evaluation system policies, forms, and other documentation against these key practices to determine the extent to which each service’s system incorporated the 11 key practices.[4] To make these determinations, two GAO analysts independently evaluated relevant documentation for evidence of each key practice and met to resolve any differences in their respective analyses. In addition, we evaluated some aspects of the military services’ performance evaluation systems against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, including the principles that management define objectives clearly and design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[5]

For our second objective, we reviewed relevant statutes, DOD policy, and military department and service policies to obtain an understanding of how performance evaluations are intended to inform officer promotion board determinations and support officer development.[6] To obtain perspectives on how the military services’ officer performance evaluation systems evaluate officer performance, inform promotion board determinations, and support officer development, we conducted nongeneralizable interviews with 19 promotion board members and 31 separate active duty officers. To identify volunteers for these interviews, we obtained lists of promotion board members and other active duty commissioned officers from each of the military services. The lists of promotion board members comprised officers that served on at least one statutory promotion selection board since January 1, 2020. The lists of active duty officers included officers who had (1) received their commission prior to January 1, 2022, and (2) represented a diversity of grade, duty location, occupational specialty, gender, and race, to the extent possible. To ensure representation from each of the military services, we randomly selected participants from each of the services’ lists and sent emails to those individuals inviting them to volunteer for an interview. We repeated this process until we achieved at least three volunteers for our promotion board interviews and five volunteers for our officer interviews from each military service. See appendix I and appendix II for our complete questionnaires used to conduct these interviews.

For both objectives, we interviewed cognizant officials on DOD and military service policies and procedures for evaluating active duty commissioned officer performance; on the performance evaluation systems’ purpose, design, implementation, and evaluation functions; and on the provision of performance-related information to promotion boards and officers. For a detailed description of our scope and methodology, see appendix III.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Performance Evaluation and Management

Performance evaluation is the practice of assessing employee or group performance based on work performed during an appraisal period against the elements and standards in an employee’s performance plan and assigning a summary rating of record. Performance evaluation systems are often used to inform and justify organizational decisions, such as promotions, compensation, reassignment, or termination.

Performance evaluation is part of the broader concept of performance management. According to the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), performance management is a systematic process by which an agency involves its employees, both as individuals and members of a group, in improving organizational effectiveness in the accomplishment of agency mission and goals. OPM policy identifies five phases of the performance management cycle: (1) planning work and setting expectations; (2) continually monitoring performance; (3) developing the capacity to perform; (4) rating periodically to summarize performance; and (5) rewarding good performance.[7] Performance evaluation most closely aligns with OPM’s fourth phase of the performance management cycle. It also includes steps such as setting expectations and monitoring performance, which align with OPM’s first and second phases, respectively.[8]

Between 2003 and 2009, we reported on DOD’s efforts to evaluate the performance of its civilian personnel through the design and implementation of two performance management systems: the National Security Personnel System and the Defense Civilian Intelligence Personnel System.[9] In that body of work, we reported on the need for appropriate internal safeguards when designing and implementing performance management systems and made 14 recommendations to improve the design and implementation of DOD’s systems. We performed the work by assessing these systems against a list of safeguards we developed based on our prior work on performance management practices used by leading public-sector organizations both in the United States and in other countries. As of August 2024, DOD had taken action to address 11 of the recommendations, which we closed as implemented. We closed the remaining three recommendations as not implemented following the 2009 repeal of the National Security Personnel System.[10]

Officer Performance Evaluations

The military services have developed and implemented service-specific systems for evaluating and documenting the performance of active duty officers based on characteristics valued by each service at specific points in an officer’s career. Within each service’s system, rating officials document officer performance on performance evaluation reports, which go into an officer’s permanent personnel file.[11]

Army. According to Army documentation, the Army performance evaluation system is intended to identify the Army’s best performers and those with the greatest potential for promotion. The system also facilitates the Army’s efforts to maintain discipline, promote leader development and professionalism, and provide feedback to rated officers.

Under the Army’s system, officers from Warrant Officer 1 (WO-1) through Brigadier General (O-7) receive performance evaluations.[12] Assessments of officer performance are made by supervisors in a rating relationship with the officer and are conducted for a number of different reasons, including (1) change of duty, (2) change of rater, (3) end of the annual 12-month rating period, (4) a “complete the record” report prior to a selection board, or (5) relief for cause (i.e., early release of an officer from a specific duty or assignment based on performance).

Key roles under the Army’s system include the rater, the senior rater, and, in some cases, an intermediate rater and a supplementary reviewer. Specifically, according to Army documentation, the rater is responsible for clearly and concisely communicating the rated officer’s most significant achievements and advocating for the officer to the senior rater. The Army’s policy for its performance evaluation system requires raters to provide an overall assessment of a rated officer’s performance during the rating period.[13] For the overall performance assessment, a rater selects a check box on the performance evaluation report based on a four-tier rating scale that ranges from “excels” to “unsatisfactory.” The check box—used on performance evaluation reports of officers in grades O-1 through O-5—is accompanied by required narrative comments.[14] In comparison, according to Army documentation, the senior rater is the owner of the evaluation and is responsible for ensuring timely completion of the evaluation report. The senior rater also uses a check box combined with narrative to assess the potential of officers in grades O-1 through O-6 and to send a clear message to the promotion boards. Under certain circumstances, a rating chain may also include an intermediate rater—a supervisor in a rated officer’s chain of command or supervision between the rater and senior rater.[15] Additionally, when there is no uniformed Army-designated rating official for a rated officer, a uniformed Army advisor from the organization above the rating chain—known as a supplementary reviewer—reviews the officer’s rating.

Navy. The Navy’s performance evaluation system policy highlights the system’s dual aims of informing officers of their performance and informing promotion boards and the chain of command about officer performance.[16] Under the system, the Navy’s performance evaluation report intends to guide performance and development, enhance accomplishment of the organization’s mission, and provide additional information to the chain of command.

In the Navy, officer performance evaluation reports are completed by an officer’s reporting senior, which is typically the officer’s commanding officer or officer-in-charge. The reporting senior evaluates officer performance across seven traits, based on a five-point scale.[17] The five-point scale ranges from one to five, with a score of one indicating an officer’s performance is “below standards” and a score of five indicating it “greatly exceeds standards.” The officer’s average rating across all seven traits is used by the reporting senior to rank officers of the same grade against their peers.

Reporting seniors also assess promotion potential when completing performance evaluation reports. The promotion recommendation uses a five-point scale ranging from “significant problems” to “early promote,” with restrictions placed on how many “early promote” and “must promote” recommendations a reporting senior can give to help reduce ratings inflation Navy-wide.

Marine Corps. According to Marine Corps policy, the Marine Corps performance evaluation report is the primary means of evaluating performance and the Commandant’s primary tool for the selection of personnel for promotion, resident schooling, and command and duty assignments, among other things.[18]

Under the system, the reporting senior is responsible for completing evaluation reports to capture an officer’s performance for a set period and to judge potential, while the reviewing officer focuses on the officer’s potential. The Marine Corps uses a seven-point scale to evaluate officer performance across 14 attributes.[19] According to Marine Corps documentation, reporting seniors assign a rating based on the seven-point scale using letter grades A through H for each attribute. Each letter grade corresponds to a number with the letter “A” corresponding with a score of one and “G” corresponding with a score of seven. The letter “H” corresponds to a score of zero, which indicates that the attribute was “not observed” and therefore was not relevant to the rating period. Reporting seniors also provide narrative that corresponds to sections of attributes. The sum of all attribute grades is divided by the number of observed attributes to calculate the officer’s evaluation average. Each reporting senior also maintains a score, known as the reporting senior average, which is calculated based on the total score of all evaluations a reporting senior has written on officers of a certain grade, divided by the total number of reports written for that grade.[20]

Air Force. According to the Air Force performance evaluation system policy, the Air Force performance evaluation system is intended to communicate performance standards, expectations, and feedback to rated officers; establish a long-term cumulative record of performance and promotion potential; and provide sound information for talent management decisions.[21] In 2022, the Air Force modified its performance evaluation system to use narrative-style performance statements combined with a competency-based framework to rate officers based on four proficiency levels ranging from “exceptionally skilled” to “needs improvement.” Officer performance is measured based on 10 desired airman leadership qualities, which represent the performance characteristics the Air Force seeks to define, develop, incentivize, and measure in its airmen.[22]

Within the system, the rater is responsible for rating an officer’s performance and potential based on performance throughout the rating period. A higher-level reviewer is responsible for performing an administrative review of all evaluations to, among other things, ensure all applicable blocks are completed and inappropriate comments or recommendations are not used.

Space Force. According to Space Force officials, the Space Force is currently implementing its own service-specific performance evaluation system after operating under the Department of the Air Force’s system since the service was established in 2019. In January 2024, the Space Force issued an instruction containing policy for its performance evaluation system to begin the process of standing up its own system.[23] Under this instruction, the Space Force maintained the use of legacy Air Force processes and forms to evaluate guardians.[24] Space Force officials stated that the service expects to reissue an updated version of that instruction with modifications to the system in late 2024. Officials further stated that Space Force-specific performance evaluation forms will accompany the reissued policy, as part of the planned update to the recently implemented system.

Similar to the Air Force, the Space Force’s performance evaluation system policy is intended to communicate performance standards, expectations, and feedback; establish a reliable, long-term, cumulative record of performance and promotion potential based on performance; and provide sound information to assist in making talent management decisions.[25] Space Force officials stated that the future updates to the system will implement the Guardian Appraisal, which will facilitate the evaluation of guardians through two key lenses of performance: (1) duty performance, or the mission-related outcomes associated with work, and (2) Guardian Commitment, or the demonstration of values while completing work.[26] Space Force officials stated that as of January 2024, the service was still developing many aspects of the new system, including a performance feedback form to identify and document expectations, a mechanism for ongoing performance data collection, and a holistic training program that will launch with the implementation of the Guardian Appraisal.

Officer Promotions

Identifying and promoting talent is of particular importance to DOD because the services generally cannot hire individuals—such as commissioned officers—into its ranks at higher-level positions. Accordingly, the department must promote its leaders from within. Military officers are selected for promotion to the next pay grade through a formal process guided by legislation and DOD policy, which includes the use of promotion boards consisting of members who determine the eligible officers most qualified for promotion.

The Defense Officer Personnel Management Act, as amended, created a standardized system for managing the promotions for the officer corps of each of the military services.[27] Originally enacted in 1980, the act sought to establish a uniform framework of laws from among the existing patchwork of rules and regulations related to the appointment, promotion, separation, and retirement of commissioned officers of the military services. The specific provisions of the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act are codified in title 10 of the United States Code and, in combination, create a framework of laws for the management of active duty officers. This includes, for example, the creation of a closed personnel system that permits new officers to enter the system at low grades, with some exceptions, and promotions made from within to fill higher grades.

The military services convene statutory promotion selection boards—referred to in this report as promotion boards—made up of designated officers to consider and recommend eligible officers for promotion to the next grade. Prior to the board convening, board members receive instructions that communicate information about board proceedings, set selection standards for the best and most fully qualified officers, and define skill requirements to be considered by the board for each competitive category, along with additional considerations.[28] Once sworn in, board members are tasked with reviewing performance evaluations and other applicable items in an officer’s official record, which may include awards, education records, letters to the board, and adverse information.

Officer Performance Evaluation Systems Incorporate Key Practices to Varying Degrees

GAO Developed Key Practices for Performance Evaluation

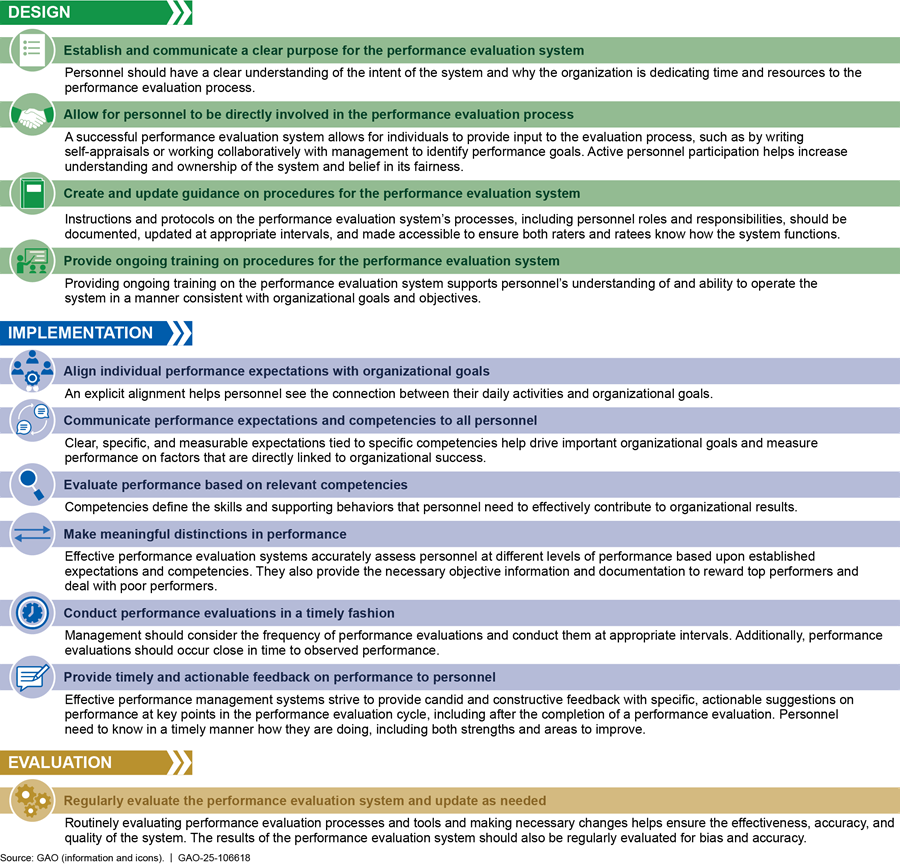

We developed a list of 11 key practices for performance evaluation to assess the military services’ officer performance evaluation systems. To develop the practices, we conducted a literature review of scholarly articles, books, and other publications on performance evaluation systems and key practices used by public- and private-sector organizations. Two analysts independently analyzed the results of the literature review to develop an initial list of practices.[29] We then incorporated, as appropriate, comments from internal stakeholders, academic experts, and DOD, military service, and other federal agency officials to develop the final set of practices. The 11 key practices for performance evaluation are shown in figure 1. These practices are grouped into three categories that relate to the design, implementation, and evaluation of a performance evaluation system.

The Military Services’ Officer Performance Evaluation Systems Fully Incorporated Some, but Not All, Key Practices

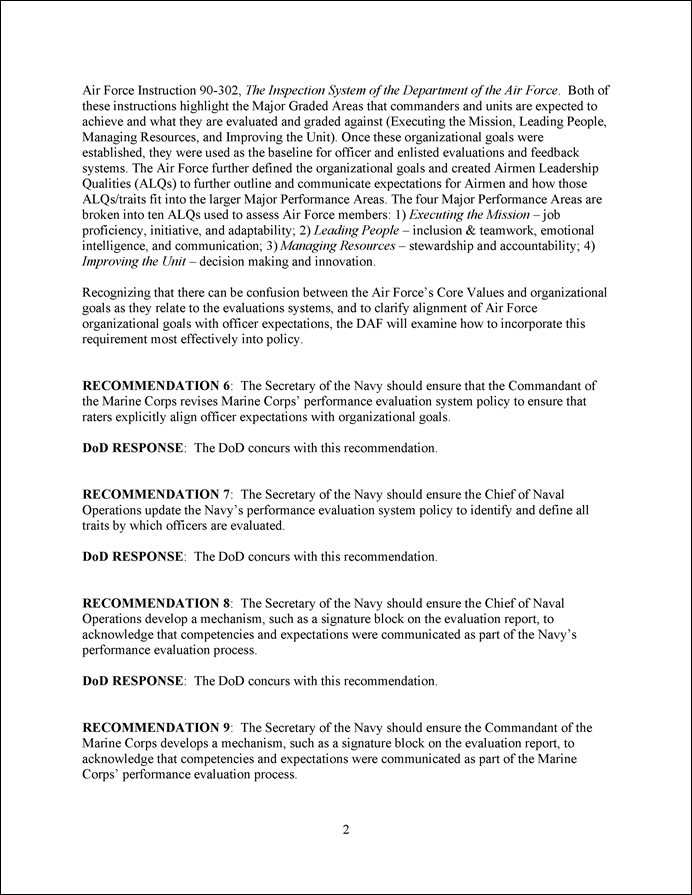

Overall, of the 11 key practices for performance evaluation, all four of the military service systems fully incorporated the same five key practices and partially incorporated one key practice.[30] The service systems varied in their implementation of the remaining five practices, with some fully incorporating the practices, some partially incorporating the practices, and most not incorporating one practice. Figure 2 shows our assessment of the military services’ performance evaluation systems against our 11 key practices, by category. Below the figure, we highlight key practices within each category that the service systems either partially incorporated or did not incorporate. Appendix V provides our complete analysis of the services’ performance evaluation systems against all 11 key practices, including our assessment of all key practices the service systems fully incorporated.

Figure 2: Overall Assessment of the Military Services’ Officer Performance Evaluation Systems against GAO’s 11 Key Practices for Performance Evaluation, Grouped by Category

Key Practices for the Design of Performance Evaluation Systems

Figure 3 shows our assessment of the military services’ performance evaluation systems against the four key practices associated with the design of a performance evaluation system. These four practices relate to the establishment of a system’s overall framework and precede steps to evaluate individual performance. All the military service systems fully incorporated three of the four practices.

Figure 3: Assessment of the Military Services’ Officer Performance Evaluation Systems against GAO’s Key Practices for Performance Evaluation, Design Category

Provide ongoing training on procedures for the performance evaluation system. We found that the Marine Corps system fully incorporated this key practice. We also found that the Army, Navy, and Air Force systems partially incorporated the practice because their performance evaluation policies do not require ongoing training on their systems, and they have not established plans to provide such training to all officers.

· Army. The Army provides some performance evaluation-related training, such as through briefings provided during required courses of instruction. However, the Army’s policy for the performance evaluation system does not specify what training on the performance evaluation system is required, when training is required, and who is responsible for providing training. Additionally, the Army has not taken steps to ensure ongoing training on the system is provided to all officers, such as through the development of a training plan.

Army officials stated that some Army officers receive training on the performance evaluation system at certain career milestones, but not on an ongoing basis. For example, Army officials told us that all newly commissioned Army officers receive training on the performance evaluation system during the Army’s Basic Officer Leadership Course. They also said that officers selected for command positions receive a briefing on the performance evaluation system from Army Human Resources Command staff. Officials provided examples of briefing slides used during trainings that discussed various aspects of the Army’s system, including how to write effective narrative comments. Army officials also stated that training materials—including these briefings—are made available on the Army Human Resources Command website.[31]

Army performance evaluation system policy requires that commanders and commandants at all levels ensure that rating officials are fully qualified to meet their responsibilities. However, the policy does not specify how commanders and commandants should ensure raters are qualified or that this should be achieved through training. Army officials also told us that training on the performance evaluation system is at the discretion of commanders.

Army officials further stated that training is the responsibility of Army Training and Doctrine Command. According to Army Training and Doctrine Command officials, training providers such as the Army Centers of Excellence may develop training on officer performance evaluations, which may become a model for other commands or centers to use. However, these officials stated that they do not have visibility over who receives such trainings or whether additional training courses are developed and used based off the initial model.

· Navy. The Navy provides some online performance evaluation-related training on specific aspects of its system, but its performance evaluation system policy does not specify what training is required, when such training is required, and who is responsible for providing such training. Additionally, the Navy has not taken steps to provide ongoing training to all officers to help ensure that all personnel understand and can operate the system in a manner consistent with organizational goals and objectives. For example, the Navy Personnel Command’s web page includes instructional videos for the online performance evaluation application, but these videos do not provide training on aspects of the system such as how to evaluate officer performance or how to write a self-assessment. Navy officials stated that individual officer communities may also conduct optional “brown bag” sessions to discuss aspects of the performance evaluation system, and that various leadership development courses and online tutorials offer lessons on the use of applicable software. However, according to Navy officials, the Navy does not have visibility into the extent of these other trainings provided on the performance evaluation system because it has not established training requirements in policy across the service.

· Air Force. The Air Force provides training on aspects of its performance evaluation system, such as a step-by-step guide for completing an electronic performance evaluation that is available to users within the service’s online evaluation system. The Air Force’s performance evaluation system policy states that commanders will ensure supervisors are properly trained and educated on how to write a performance evaluation.[32] However, this policy does not specify what training on the performance evaluation system is required for officers and when such training is required. Moreover, the Air Force has not taken steps to provide such ongoing training to all officers. Air Force officials told us that Air Force Personnel Command conducts training for personnel service and support staff, who then train commanders and users, but officials could not say with certainty whether all officers receive training on the performance evaluation system and at what intervals. Additionally, Air Force officials did not provide us with materials related to ongoing training on the performance evaluation system.

In our one-on-one interviews, officers who also serve as raters under their service performance evaluation system described differing experiences in terms of the type and timing of training they received on their services’ performance evaluation system. Some of the officers described receiving formal training once, typically earlier in their careers, such as at Officer Training School or command school. Other officers stated they received infrequent or occasional informal briefings on topics such as current trends in ratings, use of specific words in evaluations, and how to increase competitiveness in more recent years.[33] One officer we spoke with stated that training on writing performance evaluations is especially important because promotion board decisions are based on what is written in the evaluation report.

Our fourth key practice for performance evaluation states that organizations should provide ongoing training on procedures for the performance evaluation system. Providing ongoing training on the performance evaluation system supports personnel’s understanding of and ability to operate the system in a manner consistent with organizational goals and objectives. Further, according to GAO’s guide for assessing strategic training and development efforts in the federal government, planning allows agencies to establish priorities and determine how training and development investments can best be leveraged to improve performance, as well as to help ensure that such efforts are not initiated in an ad hoc, uncoordinated manner.[34] By developing a plan for the delivery of ongoing training to all officers on their respective performance evaluation systems, the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force may increase assurance that officers receive consistent and timely training on their systems and are able to conduct necessary steps in a manner that aligns with organizational goals and objectives.

Key Practices for the Implementation of Performance Evaluation Systems

Figure 4 shows our assessment of the military services’ performance evaluation systems against the six key practices for the implementation of a performance evaluation system. These six practices relate to the steps and processes used to develop performance expectations, evaluate individual performance, and provide performance feedback. All the military service systems fully incorporated two of the six key practices in this category.

Figure 4: Assessment of the Military Services’ Officer Performance Evaluation Systems against GAO’s Key Practices for Performance Evaluation, Implementation Category

Align individual performance expectations with organizational goals. We found that the Army system fully incorporated this key practice. We also found that the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force systems did not incorporate the practice because although officials told us the services have organizational goals, their performance evaluation system policies and guidance neither align performance expectations with such goals nor direct raters to do so. For the purpose of this review, we define an organization’s goals as statements of end results expected within a specified period.[35]

· Navy. The Navy’s performance evaluation system policy describes how a supervisor should connect a sailor’s performance to Navy core values and attributes during performance counseling sessions,[36] but it does not direct raters to explicitly align performance expectations with organizational goals.[37] Navy officials stated that a module in the Navy’s next generation performance evaluation and management system will align individual performance expectations with organizational goals through expectations-based evaluations.[38] Officials believe this module will afford leaders throughout the Navy more influence over how officers are evaluated against critical Navy performance standards.

· Marine Corps. The Marine Corps’ performance evaluation system policy states that reporting seniors must evaluate officers against missions, duties, tasks, and standards as communicated to the officer being evaluated. Specifically, according to that policy, the description of a marine’s occupation or primary duties—or the billet description—should highlight significant responsibilities as they relate to the accomplishment of his or her unit’s or organization’s mission during the reporting period. The performance evaluation system policy further requires that officers be evaluated against known Marine Corps values and soldierly virtues.

However, the policy does not require the alignment of individual performance expectations with organizational goals. A Marine Corps official stated that every unit is assigned a mission, and the unit’s goals are tied to that mission. The official provided an example of a unit’s organization and equipment report, which identifies the unit’s assigned mission and how tasks should tie into that mission. This official further stated that if an officer understands his or her billet description and how that billet description relates to the mission of the unit, the officer’s daily activities and expectations are effectively aligned with a unit’s goals. However, the example of the unit organization and equipment report provided to us focused specifically on the unit’s mission and, therefore, did not clearly reflect an alignment between mission and goals.

· Air Force. Air Force performance evaluation system documentation highlights the importance of the Air Force’s Core Values, but its performance evaluation system policy does not require that raters align rated officers’ individual expectations with organizational goals.[39] Air Force officials told us that individual performance expectations are aligned to four major performance areas, which are divided into 10 Airman Leadership Qualities, and are considered metrics for mission achievement. These major performance areas include (1) executing the mission, (2) leading people, (3) managing resources, and (4) improving the unit. The officials stated that the major performance areas are organizational goals that commanders and units are expected to achieve and be evaluated against.

However, documentation provided by Air Force officials aligned these major performance areas and the associated Airman Leadership Qualities with the Air Force’s Core Values. The documentation also did not state that an explicit alignment of individual performance expectations with Air Force organizational goals should occur. As discussed, goals and values differ in that an organization’s goals are end results expected to be achieved within a specified period, while its values are the moral code of the organization.

Our fifth key practice for performance evaluation states that organizations should align individual performance expectations with organizational goals. An explicit alignment helps personnel see the connection between their daily activities and organizational goals.[40] By revising policy or guidance to direct raters to explicitly align individual officer performance expectations with organizational goals, the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force can better ensure that officers’ daily activities and performance are cascading upwards to meet the goals of the organization.

Communicate performance expectations and competencies to all personnel. We found that the Army and Air Force systems fully incorporated this key practice. The Navy and Marine Corps systems partially incorporated the practice because they do not have assurance that clear, specific, and measurable performance expectations tied to specific competencies are being communicated to all personnel.

· Navy. As previously discussed, the Navy evaluates officers up to the rank of captain (O-6) against seven traits, or competencies, using a five-point scoring system. According to a Navy official, the Navy’s performance evaluation system policy should guide officers’ understanding of the system’s procedures and processes. However, while the policy[41] provides detailed descriptions for all traits used to evaluate flag officers, it identifies and provides detailed descriptions for only two of the seven traits used to evaluate all other commissioned officers.[42]

Navy officials stated that due to concerns about the length of the policy, detailed descriptions were provided in the policy for the two traits that most often lead to adverse evaluations. Those two traits were (1) Command or Organizational Climate/Equal Opportunity and Character, and (2) Military Bearing and Character. One official further stated that raters and rated officers may refer to the performance evaluation report used during the performance evaluation cycle to identify the full list of traits on which officers are evaluated. However, the report provides only limited descriptions for the seven traits and describes what constitutes performance at three of the five rating levels; it does not provide full descriptions for the five traits not addressed by the policy. For example, the evaluation report identifies what performance levels should result in ratings of 1, 3, and 5, but does not provide descriptions for ratings of 2 or 4.

Further, the Navy does not have a mechanism for capturing or acknowledging that expectations and competencies were communicated by raters to rated officers. Navy policy states that raters will perform counseling at the midpoint of the performance evaluation cycle and at the signing of the report. While the Navy’s performance evaluation report contains signature blocks to document that midpoint and final counseling occurred, it does not include a mechanism, such as a signature block, for the officer to acknowledge the communication of clear, specific, and measurable expectations tied to specific competencies.

· Marine Corps. The Marine Corps’ performance evaluation system policy and its associated performance evaluation report clearly identify and define the competencies by which officers are evaluated and set the standards for specific performance ratings for each competency. The Marine Corps’ policy also outlines a process for developing officer billet descriptions. This process serves to communicate performance expectations and competencies to officers, according to Marine Corps officials. The policy states that within the first 30 days of a reporting relationship, the rater and rated officer should meet to discuss and establish the rated officer’s billet description and document it on the performance evaluation report. However, the Marine Corps’ performance evaluation report does not include a mechanism—such as a signature block—for the officer to acknowledge this step.[43] A Marine Corps official confirmed that there is no such mechanism on the form and that there is nothing in current practice to ensure this process is occurring as intended. He stated that this was a gap in the Marine Corps’ current approach and that the Marine Corps is exploring options to achieve greater assurance that the policy is being followed, such as by notifying both the rater and the rated officer when the 30-day window for the initial counseling session begins.

Our sixth key practice for performance evaluation states that organizations should communicate performance expectations and competencies to all personnel. Clear, specific, and measurable expectations tied to specific competencies help drive important organizational goals and measure performance on factors that are directly linked to organizational success. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should design control activities—such as the policies, procedures, techniques, and mechanisms that enforce management’s directives—to achieve an entity’s objectives and address related risks.[44] By revising its performance evaluation system policy to identify and define all traits by which officers are evaluated, the Navy will be positioned to better communicate expectations and competencies to all personnel. Separately, by developing a mechanism, such as a signature block on the evaluation report, to acknowledge the completion of performance expectation and competency discussions, the Navy and the Marine Corps will have greater assurance that this step is being carried out, as required.

Make meaningful distinctions in performance. We found that the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force performance evaluation systems fully incorporated this key practice. We found that the Army’s system partially incorporated this practice because it employs a forced distribution of ratings, which limits the number of top-level ratings—known as the “top block”—a rater may assign to officers of any grade. This forced distribution may not result in accurate, meaningful distinctions of officer performance.

As previously discussed, Army raters evaluate officer performance by selecting a check box on the performance evaluation report that aligns with a four-tier rating scale. According to Army policy, under the Army’s forced distribution, a rater’s use of the top-level rating cannot exceed 50 percent of officers within each grade of officers evaluated by that rater.[45] Army officials stated that this limit on the top-level rating enforces rater accountability while controlling ratings inflation.

According to Army documentation, the rater’s overall distribution of ratings—known as the rater’s profile—is maintained over the rater’s entire career. Officials stated that when evaluating an officer’s performance, a rater must consider the performance of all officers of the same grade that the rater previously evaluated, as well as all future officers the rater may evaluate. This may result in a rater assigning a high-performing officer a more average rating to help ensure they reserve space within their profile to assign top-level ratings to future officers. While the use of a forced distribution system is not prohibited for active duty service members, an OPM memorandum states that the forced distribution of civilian employees among levels of performance is prohibited, because employees are required to be assessed against documented standards of performance versus an individual’s performance relative to others to ensure accurate individual ratings based on objective criteria.[46]

During our officer interviews, two of the six Army officers stated they felt the Army’s forced distribution poses challenges for raters to accurately evaluate officer performance. One officer told us that the timing of an officer’s evaluation could factor into their rater’s assessment of performance because the rater may be constrained by the forced distribution. For example, according to the officer, raters may choose to withhold higher ratings for officers close to retirement in order to maximize their ability to use higher ratings to advance the careers of those who will remain in the Army. Another officer stated that rating can be difficult in organizations with a concentration of top performers or individuals with highly specialized training because raters are constrained by the same cap as all other units.

Our eighth key practice for performance evaluation states that organizations should make meaningful distinctions in performance. Effective performance evaluation systems accurately assess personnel at different levels of performance based upon established expectations and competencies. They also provide the necessary objective information and documentation to reward top performers and deal with poor performers. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives.[47] By assessing the design, implementation, and outcomes associated with its forced distribution model, the Army will have better insight into whether its performance evaluation system is resulting in accurate, meaningful distinctions of officer performance. Moreover, such an assessment would allow the Army to consider alternatives as necessary based on the findings of the assessment.

Provide timely and actionable feedback on performance to personnel. We found that the Navy and Air Force performance evaluation systems fully incorporated this key practice. We also found that the Army and Marine Corps systems partially incorporated the practice because their policies do not require that raters provide performance feedback at all key points in the process. Further, the Army policy does not require that officers of all grades receive performance feedback.

· Army. The Army has established some limited time frames for the provision of performance feedback to some officer grades, but it has not required that all officer grades receive performance feedback or that feedback be provided following a performance evaluation. Moreover, it does not have a mechanism to help ensure that feedback occurs after a performance evaluation.

Army policy states that initial performance counseling should be provided within the first 30 days of the rating period, and quarterly thereafter, for officers in grades O-1 through O-3. However, according to this policy, initial and ongoing counseling for all other officer grades is provided on an as-needed basis. Army officials stated that once an officer reaches the grade of O-4 or higher, they should understand the Army’s and their supervisor’s expectations. These officials further stated that for grades O-4 and above, counseling should be an informal, ongoing process since formal or documented counseling has the potential to carry a negative connotation. The Army’s performance evaluation system policy does not require raters to conduct counseling or other performance feedback sessions with officers of all grades after a performance evaluation or to identify time frames for conducting such sessions.

Additionally, the Army does not have a mechanism on its officer performance evaluation forms to ensure that feedback is delivered after the officer’s performance evaluation.[48] Army policy requires the use of the Officer Evaluation Report Support Form, which includes a section for the rated officer, rater, and senior rater to verify that face-to-face counseling occurred periodically during the evaluation cycle.[49] Separately, the Army’s officer performance evaluation report includes a section for the rater to indicate that the Officer Evaluation Report Support Form was received and used when drafting the officer’s rating. However, the Officer Evaluation Report Support Form, which documents the dates counseling occurred, is completed prior to the preparation of the officer’s evaluation report by the rating chain and, therefore, cannot capture whether feedback was provided with the performance evaluation report.

According to Army officials, a rated officer authenticates—or signs—an evaluation report after all rating officials in the rating chain have conducted and authenticated their assessment of the rated officer’s performance. These officials further stated that according to Army policy, the final evaluation report must be submitted for processing to an officer’s permanent record within 90 days of the date the evaluation report was completed. According to the officials, this time frame provides rating officials the opportunity to present, discuss, and authenticate an evaluation report with a rated officer. The officials further stated that the submission of the final evaluation report represents the acknowledgment that all required steps during the evaluation period were completed.[50] However, as discussed, Army policy does not require raters to provide performance feedback with the performance evaluation report and there is no mechanism, such as a signature block on the evaluation report, to capture that any feedback occurred.

· Marine Corps. The Marine Corps partially incorporated this practice because although its policies and guidance provide for the provision of some feedback, it does not have clear requirements for performance feedback following a performance evaluation or a mechanism to ensure that feedback is delivered at all key points in the performance evaluation cycle.

Specifically, the process for providing performance feedback in the Marine Corps is defined within three policy and guidance documents—its counseling guidance, performance evaluation system policy, and leadership development policy.[51] The counseling guidance—which officials told us governs the counseling program for the Marine Corps independent of the performance evaluation system policy—states that officers will receive an initial counseling session within 30 days of establishing a rater-ratee relationship and follow-on sessions at intervals of no more than 6 months.[52] However, neither this counseling guidance nor the two other policy documents establish clear requirements for the provision of feedback with specific, actionable suggestions on performance to officers after the completion of a performance evaluation. The Marine Corps performance evaluation system policy specifically states that counseling[53] is separate and complementary to performance evaluation.[54]

Additionally, while the Marine Corps’ counseling guidance sets the time frames for initial and follow-on counseling, it does not require documentation of those counseling sessions and leaves specific procedures up to the individual unit commanders. This guidance provides worksheet templates and recommended elements for the documentation of counseling. But neither the guidance nor associated documentation include a mechanism—such as a signature block—for the officer being evaluated to acknowledge the completion of counseling during the performance evaluation cycle or following the completion of a performance evaluation report.

Sixteen of the 31 officers we interviewed told us they received feedback accompanying their most recent performance evaluation report, while the remaining fifteen told us they did not receive such feedback—including three of the six Army officers and two of the six Marine Corps officers.[55] For example, one Marine Corps officer told us that the Marine Corps does not have a system in place to force the rater to provide feedback to an officer on the performance evaluation report. The officer further told us that feedback is considered a good practice but not a requirement, and that sometimes officers do not receive feedback at all. Similarly, another Marine Corps officer stated that although officers are supposed to receive quarterly counseling, performance feedback following a performance evaluation is often not provided because there is no formal requirement to do so. We present additional officer perspectives on the types and frequency of feedback received later in this report.

Our tenth key practice for performance evaluation states that organizations should provide timely and actionable feedback on performance to personnel. Effective performance management systems strive to provide candid and constructive feedback with specific, actionable suggestions on performance at key points in the performance evaluation cycle, including after the completion of a performance evaluation. Personnel need to know in a timely manner how they are doing, including both strengths and areas to improve. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should design control activities—such as the policies, procedures, techniques, and mechanisms that enforce management’s directives—to achieve objectives and address related risks.[56]

By establishing clear requirements in policy for the delivery of performance feedback at all key points of the performance evaluation process—including after the completion of a performance evaluation report—and creating a mechanism, such as a signature block, to ensure it occurs, the Army can better ensure that officers receive timely and actionable information on their performance throughout the process. Similarly, by (1) establishing clear requirements in policy for the provision of timely and actionable performance feedback following the completion of a performance evaluation report, and (2) developing a mechanism, such as a signature block, to ensure feedback at all key points of the process occurs, the Marine Corps can better ensure that feedback is provided to all officers.

Key Practices for the Evaluation of Performance Evaluation Systems

Figure 5 shows our assessment of the military services’ performance evaluation systems against our key practice for evaluating system processes and tools to ensure effectiveness, accuracy, and quality.

Figure 5: Assessment of the Military Services’ Officer Performance Evaluation Systems against GAO’s Key Practices for Performance Evaluation, Evaluation Category

Regularly evaluate the performance evaluation system and update as needed. We found that all four of the military services partially incorporated this practice because although the services update their performance evaluation policies and have studied some aspects of their systems, they have not regularly evaluated their systems, including system processes and tools, and do not have plans for conducting such evaluations in the future.

· Army. According to Army officials, the Army’s most recent evaluation of its performance evaluation system—a directed review—culminated in 2014.[57] Since then, officials told us, the Army’s efforts to evaluate its system have included the processing and final compliance reviews of ratings, and the consideration of ad hoc updates to the system’s policies, processes, and tools. For example, Army officials stated that changes in law, Army doctrine, and DOD policy are considered when proposed to ensure that the performance evaluation system remains current with such changes.

According to Army policy, the senior rater is responsible for conducting a final review of the ratings to check for objectivity and fairness of officer ratings and completeness of performance evaluation reports.[58] Army officials also stated that the Army Human Resources Command’s Evaluations Branch receives every Army evaluation report for processing and final review for compliance with established policy and checks for violation or error, among other things. Army officials stated that these final review responsibilities help ensure constant oversight and monitoring capabilities for the health of the Army’s performance evaluation system. These officials further stated that feedback is collected following selection board deliberations to assess system effectiveness. However, while Army officials described examples of efforts to us, they were unable to provide us with documentation to support how or when such reviews and evaluations occur or a plan for conducting such reviews in the future.

· Navy. The Navy has made incremental changes to its performance evaluation system. For example, in 2022, the Navy began implementing an electronic system for filing performance evaluation reports. Additionally, two recent studies conducted by the Naval Postgraduate School reviewed aspects of the system. Specifically, one of the studies identified perceptions of the Navy’s system and compared it to the other services’ systems, while the other validated future performance traits the Navy has developed as part a new performance evaluation system prototype.[59] Navy policy also states that commands should establish quality review processes to check performance evaluations for completeness.[60] However, the Navy has not regularly evaluated the system’s processes and tools to help ensure the effectiveness, accuracy, and quality of the system. Further, it does not have a process for conducting reviews of ratings or ratings trends to ensure fairness or accuracy of individual ratings.

· Marine Corps. According to Marine Corps officials, the last major evaluation or study of its performance evaluation system was conducted in 1996, just prior to the service adopting its current system. However, the Marine Corps has since made updates to its system through revisions and changes to the performance evaluation system policy, with the most recent reissuance occurring in June 2023. The Marine Corps also has processes for inspecting performance evaluation reports and reviewing rating trends, which according to officials, include reviews at the headquarters level for accuracy and completeness. However, these efforts do not include regular evaluation of the system’s processes and tools to help ensure its effectiveness, accuracy, and quality.[61]

· Air Force. According to Air Force officials, the Air Force makes incremental changes—such as policy updates—to its performance evaluation system as needed and has a process for ensuring completeness of performance evaluation reports. However, it has not regularly evaluated the system’s processes and tools to help ensure the effectiveness, accuracy, and quality of the system, and it does not review ratings or related trends to ensure fairness or accuracy of individual ratings.

The Air Force’s performance evaluation system policy requires that the Directorate of Military Force Management Policy establish an annual evaluation systems program review to determine if improvements or changes are needed. An Air Force official told us that such reviews have not been required due to the frequency of updates made to the performance evaluation system policy, with some as recent as 2023 and 2024. However, the policy-specific updates officials described were not based on evaluations of the system’s processes or tools. For example, officials stated that the most recent policy update revised the Department of the Air Force policy to be applicable only to the Air Force following the issuance of the Space Force’s policy. Additionally, the Air Force’s performance evaluation system policy states that major commands may conduct an optional quality review of ratings and return any for correction, as necessary.[62] However, the policy does not prescribe the scope of these reviews and their optional nature does not ensure that the results of the performance evaluation system are reviewed on a regular or routine basis.

Air Force officials also told us that the Air Force has contracted with the RAND Corporation to develop an evaluation plan to study the impact of changes made to the Air Force’s performance evaluation system, which will include surveying airmen at all ranks to gather feedback on their experiences with the performance evaluation system. However, officials did not state how these perspectives would inform an evaluation of the performance evaluation system. Moreover, while the Air Force has this effort underway, it does not have a plan to evaluate its performance evaluation system moving forward.

Our eleventh key practice for performance evaluation states that organizations should regularly evaluate their performance evaluation systems and update them as needed. Routinely evaluating performance evaluation processes and tools and making necessary changes helps ensure the effectiveness, accuracy, and quality of the system. Further, the results of the performance evaluation system should also be regularly evaluated for bias and accuracy. By developing plans to regularly evaluate their officer performance evaluation systems, including system tools and processes, the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force will be better positioned to ensure that their performance evaluation systems are achieving intended results in an effective and accurate manner. Moreover, by developing a process for conducting reviews of the results of their performance evaluation systems, for example, through reviews of ratings or ratings trends, the Navy and Air Force will have better assurance that performance evaluation ratings are accurate and free from bias.

Promotion Boards Use Performance Evaluation Reports to Inform Determinations, but Officer Perspectives Differ on Whether Evaluations Support Development

Promotion board members and other officers we interviewed provided differing perspectives on the value of information captured in officer performance evaluation reports. Promotion board members felt the evaluation reports provided sufficient information to inform their decisions about which officers to recommend for promotions. However, other officers we spoke with shared mixed perspectives on the value of their performance evaluations and the extent to which they support officer development. The information captured during our interviews with promotion board members and other military officers is not generalizable to the broader officer or total military populations, but it provides insights into potential areas that may warrant further consideration by the services as they assess their individual performance evaluation systems. As previously discussed, the military services have not regularly evaluated their performance evaluation systems’ tools and processes.

Performance Evaluation Reports Directly Inform Officer Promotion Determinations

Military officer performance evaluation reports provide key information for promotion boards making determinations about which officers to select for promotion. As discussed, the military services convene promotion boards to consider and recommend eligible officers for promotion to the next grade.[63] Board members receive instructions about board proceedings prior to the board convening and review performance evaluation reports and other applicable items in an officer’s official record once the board convenes. These items include awards, education records, letters to the board, and adverse information.

According to service policies, the military services’ officer performance evaluation reports provide the primary source of information to support selection of the best qualified officers for promotion, career designation, retention, schooling, and command and duty assignments. As discussed, each service’s evaluation report comprises a unique combination of competencies, rating scales, and narratives to provide a documented assessment of an officer’s performance during the performance period.

To better understand promotion board members’ use of performance evaluation information during board deliberations, we conducted 19 nongeneralizable interviews with officers who served on at least one statutory promotion board since January 1, 2020.[64] Overall, promotion board members we interviewed held positive views of the quantity of information they received during board proceedings and of the time they were afforded to consider the information.

· Quantity of information. All 19 members we interviewed stated they felt they received enough information—across all sources of information they received—during the most recent promotion board they served on to make an informed decision about whether to recommend specific officers for promotion. Two board members told us that the addition of more information on the officers could hinder the board’s progress.

· Time to consider information. Seventeen of the 19 board members felt they had enough time to consider the information provided on each officer. Two board members told us that additional time was allowed, as needed, to review all the necessary information on the officers. Another board member noted that being new to the board process and a slower reader resulted in concern about keeping up with the more experienced board members who were more familiar with the process.

When asked about the specific types of information the board members reviewed, 18 of the 19 promotion board members told us they reviewed officer performance evaluation reports when considering an officer for promotion. One board member responded that he did not review the evaluation report for every officer being considered because, as part of the board’s procedures, summary information was presented by other board members who were responsible for reviewing and presenting specific officer files. Overall, board members generally held positive views of the usefulness and level of detail of officer performance evaluation reports.

· Usefulness of reports. Seventeen of the 18 board members who told us they reviewed officer performance evaluation reports found the information contained in the reports to be useful or very useful when deciding whether to recommend an officer for promotion. One member stated that evaluation reports were very useful because almost all reports clearly conveyed whether an officer should be promoted, and that it would be rare for a board to see a generic report that did not clearly indicate future potential. Another board member told us the evaluation reports are useful, but not very useful, because the reports provide the best possible image of the officer since the goal is to get the officer promoted. One board member told us that the information contained in the evaluation reports is somewhat useful but did not explain why certain types of information were only somewhat useful.

· Detail of reports. Sixteen of the 18 board members who told us they reviewed officer performance evaluations felt their service’s evaluation reports provided enough detail to inform their decisions about whether to recommend an officer for promotion. For example, several board members identified specific sections on the evaluation report that highlight an officer’s performance in a specific role. Conversely, one officer told us that the performance evaluation reports do not provide enough detail due to a limit on the narrative that must capture an entire year’s worth of performance. One other board member did not answer the question.

Promotion board members also described specific words or phrases that may be used in performance evaluation reports to send a signal about officer performance to promotion boards. Specifically, 16 of the 19 promotion board members we interviewed were aware of certain words or phrases used by raters in performance evaluation reports to communicate with the promotion boards. For example, according to board members, statements such as “promote immediately,” “future general,” and “enthusiastically recommend” are often used to convey a positive message to the board about an officer’s potential. The board members also stated that vague language, or the omission of certain words or phrases—such as the aforementioned examples—serves as a signal to the board that the rater would not endorse the officer for promotion. Board members stated that they did not receive training on how to interpret these words or phrases; rather, they had a general understanding of how to interpret them based on their time operating under their services’ performance evaluation system.

While promotion board members’ responses about the utility of performance evaluations were generally positive, some members made suggestions related to the information provided to the boards. For example, several members stated they would like to see 360-degree feedback incorporated into the evaluations or added to officers’ files to better capture peer or subordinate views of officers’ performance, and to provide the boards with further insight into officers’ leadership potential or concerns about toxic behavior. Additionally, members who served on Space Force promotion boards felt more time should be spent reviewing information about other military services’ performance evaluation systems and reports to better understand how those systems operate, since the newest service is composed of transfers from other services. Finally, some board members made suggestions about ways the services could better address the potential for bias based on gender or race. For example, one board member stated that names should be replaced with a number on performance reports to further eliminate identifiers of gender and race.

See appendix VI for summary data of responses to selected questions from promotion board members who volunteered to be interviewed about their experiences serving on a statutory promotion selection board.

Officers Shared Varying Perspectives on How Evaluations Support Their Development

Officers we interviewed about their own performance evaluation experience shared a range of perspectives on whether performance evaluation reports and related feedback provide useful information that supports their development. We conducted nongeneralizable interviews with 31 officers across all five military services to capture these perspectives.[65]

Performance evaluation reports. Three officers we interviewed stated that their service’s performance evaluations provide a clear and relevant tool for assessing officer performance and supporting officer development. For example, one officer stated that the system is transparent and that he would not change any aspects of the system. Another officer stated that the criteria outlined in the evaluation are well developed and associated expectations were clearly described by the rater. Additionally, one officer stated that one of his performance evaluation reports prompted a discussion about overall performance and ways to continue progressing professionally.

By contrast, several officers stated that performance evaluations do not provide actionable information that supports development. Officers that held these views cited three main reasons for why performance evaluations do not provide actionable information.

· Content policies and expectations. Six of the officers noted that service policies and expectations about the content of performance evaluation comments limit the use of actionable information that could support officer development.[66] For example, one officer stated that performance evaluations provide only positive accounts of an officer’s performance, with little information on necessary improvements to performance. Another officer told us that it can be difficult to write clearly about an officer’s performance due to perceived restrictions on what a rater can and cannot say.

· Misused or overused common narrative. Three officers we interviewed stated that because some raters misuse or overuse common narrative, the evaluations may not provide a clear picture of a rated officer’s performance or areas in need of growth or emphasis. For example, one officer stated that some raters inaccurately characterize performance using commonly used positive narrative because they are reluctant to have difficult conversations with underperforming officers.

· Audience of reports. Six officers suggested that the content and presentation of information in performance reports do not support development because promotion boards are the target audience of evaluations. For example, one officer stated that raters include or do not include certain phrases or statements—such as enumeration about where the officer ranks or when they should be promoted in relation to peers—to send a message to the board. Another officer stated that since board members likely do not know the officers personally, the evaluation reports will convey overall performance and career potential but will not necessarily reflect areas of growth.

Performance feedback. Twenty nine of the 31 officers we interviewed reported receiving some form of feedback on their performance at some point during their most recent evaluation cycles. According to the officers, this feedback was typically provided in the form of ongoing or scheduled feedback sessions or in response to a specific action. As we have previously discussed, the provision of timely and actionable feedback on performance is GAO’s tenth key practice for performance evaluation.

As previously noted, 16 of the 31 officers we interviewed told us they received feedback accompanying their most recent performance evaluation report. Of those, nine officers felt that the feedback they received was either valuable or very valuable to their development as an officer. For example, one officer told us that he received critical feedback during an end-of-evaluation cycle feedback session, which allowed him to improve his performance without detrimental career impacts. Of the remaining seven officers, five stated that the feedback they received with their most recent performance evaluation was somewhat or slightly valuable, while two stated that the feedback received with their most recent performance evaluation was not valuable at all to their development.

When asked to consider all types of feedback—not only the feedback provided with their most recent performance evaluation—received since January 1, 2022, 10 of the 31 officers told us that feedback provided during ongoing or scheduled sessions was the most valuable form of feedback to their professional development. Nine of the 31 officers stated that feedback in response to a specific action was the most valuable, and three officers said the feedback they received with a performance evaluation was the most valuable type of feedback to their professional development.[67] Of the remaining nine officers, eight cited other instances during which they received feedback that they found to be the most valuable to their professional development. One officer was unsure which type of feedback was the most valuable.

Other officers we interviewed described not receiving feedback at all or having feedback sessions that were largely perfunctory, particularly when their performance evaluation was positive. For example, one officer stated that actionable feedback was never provided with prior performance evaluation reports and that rater comments accompanying the evaluation reports were limited to statements such as “good job” and a request for signature. The officer further stated that developmental feedback should be provided at midpoint so that performance can be corrected between midpoint and receiving the performance evaluation report. Similarly, several other officers noted that when the evaluation is good, the feedback provided is to maintain the status quo in terms of performance without mention of ways to develop further as an officer. See appendix VII for summary data of responses to selected questions from our interviews with officers about their services’ performance evaluation systems.

Conclusions