DOE LOAN PROGRAMS

Actions Needed to Address Authority and Improve Application Reviews

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Frank Rusco at ruscof@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106631, a report to congressional committees

Actions Needed to Address Authority and Improve Application Reviews

Why GAO Did This Study

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) and the Inflation Reduction Act (2022) added two new loan programs to the three in DOE’s portfolio. The additions increased the office’s available loan authority many times over, bringing it to over $400 billion. Much of this authority expires in 2026 and 2028.

Congress provided in statute for GAO to review DOE’s Loan Guarantee Program. GAO’s scope for its report is the five loan programs administered by the office. The report examines (1) how the office has addressed the expansion of its loan programs and loan authority; and (2) the extent to which the office’s application review guidance and procedures ensure consistent and accurate application reviews.

GAO analyzed DOE actions to address an increase in applications. GAO also identified the extent to which DOE was planning to use the amount of its loan authority. It also reviewed application review guidance, documentation, and training, and interviewed DOE officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider changing authority for the five programs by, for example, reducing authority for the Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program. GAO is also making four recommendations to the Secretary of Energy; DOE concurred with three of them. DOE did not concur with GAO’s recommendation to review innovativeness at the time of conditional commitment. As discussed in the report, GAO maintains that such action is needed to help ensure that DOE is compliant with applicable law.

What GAO Found

The Department of Energy (DOE) is to provide loans and loan guarantees for innovative and other high-impact energy-related ventures through its Loan Programs Office (office). In recent years, Congress added two new loan programs and hundreds of billions of dollars in new loan authority for the office to manage. At the same time, the number of applications for loans and guarantees increased substantially. In response, the office increased its staff from 104 in 2020 to 412 in 2024, and made organizational changes, among other actions.

The office is not on track to issue loans in the amounts Congress authorized. A key example of this is the Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program. Enacted in August 2022, it received $250 billion in loan authority due to expire September 30, 2026. However, as of September 30, 2024, the office had made one loan for about $1.4 billion. While it has a total of $108.3 billion in outstanding submitted applications for loans and guarantees, the program almost certainly will fall short of the $250 billion in loan authority. Further, DOE needs to thoroughly review the current applications to ensure the government’s interests are protected.

However, the office cannot ensure consistent and accurate application reviews. For example, their guidance is at times incorrect and outdated. In several instances, the guidance refers to documents that officials said are no longer used, and it is at times contradictory or unclear. As a result, staff would likely find it difficult to follow the correct practice. Further, GAO found that the office’s guidance does not always follow the law. For projects that are required to be innovative, the office determines innovativeness early in the application review process and risks issuing a guarantee for a project that is no longer innovative. Without confirming innovativeness when it offers conditional commitment, the office may make loans or guarantees for projects that are not eligible.

Finally, the office does not comprehensively evaluate its application review process, including whether guidance is up to date, because officials have not considered the application review process to be high risk. Conducting a comprehensive annual review of this process could help the office identify and correct errors to better ensure it is consistently and accurately reviewing applications. Without correcting its guidance, the office cannot be assured that application reviews lead to selecting projects that further program goals.

Abbreviations

|

ATVM |

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Program |

|

CIFIA |

Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Program |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

FFB |

Federal Financing Bank |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act |

|

LPO Section 1703 |

Loan Programs Office Title XVII Clean Energy Financing Program |

|

Section 1706 |

Title XVII Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program |

|

TEFP |

Tribal Energy Financing Program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 8, 2025

The Honorable John Kennedy

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Chuck Fleischmann

Chairman

The Honorable Marcy Kaptur

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Department of Energy (DOE), through its Loan Programs Office (LPO), is responsible for implementing five federal programs to provide a “bridge to bankability” for innovative and other high-impact energy-related ventures. LPO accomplishes this by providing access to loans and loan guarantees that private lenders cannot or will not provide. To that end, since the first programs were established in 2005, LPO had made about $43.9 billion in loans and loan guarantees through September 2024. Most of these loans were approved before 2016.[1] LPO loans and loan guarantees support projects across the energy and advanced transportation sectors. Entities defaulting on loans for projects supported by LPO could lead to financial losses for the federal government.

We issued eight reports on DOE’s loan programs between 2007 and 2015 and made multiple recommendations to improve the programs.[2] Several recommendations focused on ensuring LPO had appropriate guidance and procedures in place to, for example, lay out roles, responsibilities, criteria, and requirements for conducting and documenting analyses and decision-making. DOE implemented most of these recommendations.

After several years in which LPO made very few loans, the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) expanded eligibility criteria for LPO’s existing programs. The acts also added new loan programs and provided over $360 billion in new loan authority for LPO, with much of the loan authority expiring by 2028.[3] These changes were accompanied by changes in regulations and policy. Industry interest in LPO’s loan programs increased in 2021 and, in this context, LPO added staff and set targets for application reviews.

In 2022, in response to the increase in funding, the DOE Office of the Inspector General identified four major risk areas for LPO: insufficient federal staffing; inadequate policies, procedures, and internal controls; lack of accountability and transparency; and potential conflicts of interest and undue influence.[4]

GAO has an ongoing mandate, first included in the 2007 Revised Continuing Appropriations Resolution, to review DOE’s execution of its loan guarantee programs and to report its findings to the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations.[5] This report addresses (1) how LPO has addressed the expansion of its loan programs and loan authority, and (2) the extent to which LPO’s application review guidance and procedures ensure consistent and accurate application reviews.

To examine how LPO has addressed the expansion of its programs and loan authority, we analyzed LPO data on applications; reviewed relevant laws, regulations, guidance, and program documentation; and interviewed LPO officials. Specifically, we analyzed LPO data on applications submitted from January 2016 through September 2024 to describe industry interest in LPO’s programs (as measured by the number of applications), the status of applications, the portfolio of projects, and the duration of application reviews. We also requested data on applications that had reached conditional commitment or financial close through December 2024 because of the significant increase in conditional commitments and financial closes during the last quarter of calendar year 2024. We took steps to assess the reliability of these data and found them to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting application review durations, milestone achievement, and financial information. To identify recent changes to LPO’s programs, we reviewed the IIJA, IRA, other relevant statutes, as well as draft and final rules and program guidance. We also interviewed LPO officials on the data and recent changes to the programs.

To evaluate the extent to which LPO’s application review guidance and procedures ensure consistent and accurate application reviews, we reviewed documents and interviewed LPO officials on three topics: (1) LPO’s application review guidance, (2) LPO’s application review documents, and (3) LPO’s training on how to review loan and guarantee applications. To understand LPO application review guidance, we requested application review guidance for each of the five loan and loan guarantee programs. We reviewed this guidance to identify the forms, memos, and other documents that LPO and independent contractors develop during the application review process. We also interviewed LPO officials about the application review guidance. To determine the extent to which LPO’s application review documents follow guidance on the process, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of 23 applications—across all five loan programs—submitted from fiscal year 2018 through August 10, 2023. We requested all available loan application documents for these applications, which resulted in 283 documents, such as forms LPO uses to determine whether a project is eligible for its programs, project reports from independent engineers, spreadsheets used to calculate risk, and memos to document decisions. We reviewed the documents provided to determine if they followed the guidance. Finally, we collected and reviewed LPO training materials and interviewed officials to better understand the extent to which LPO’s training program addressed the needs of staff who conduct application reviews. See appendix I for additional details on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Loan and Loan Guarantee Programs

Currently, LPO administers five loan and loan guarantee programs—three that have been in place for over a decade and two that were introduced by the IIJA and IRA.[6]

Title XVII Clean Energy Financing Program (Section 1703). The Energy Policy Act of 2005 established this program.[7] The program is to provide loan guarantees for projects that support clean energy deployment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or air pollution.[8] To be eligible, a project must fit into one of three categories: (1) innovative energy projects that deploy a new or significantly improved technology that is technically proven but not widely commercialized in the U.S., (2) innovative supply chain projects that deploy a new or significantly improved technology in the manufacturing process for a qualifying clean energy technology, or for projects that manufacture a new or significantly improved technology, or (3) projects that receive meaningful financial support or credit enhancements from a state energy financing institution, which may or may not employ innovative technology.[9] DOE’s regulations establish that, for projects to qualify as innovative, the technology should be innovative at the time LPO issues the term sheet—the document laying out the terms and conditions of the loan or guarantee—to the applicant.[10] For more detailed information on this and the other programs, including current loan portfolios and number of pending applications, see appendix II.

|

Title XVII Clean Energy Financing Program (Section 1703): Example Project In June 2022, the Loan Programs Office (LPO) announced a $504.4 million loan guarantee to finance Advanced Clean Energy Storage, a clean hydrogen and energy storage facility in Utah for providing long-term, seasonal energy storage. The facility is designed to use an innovative process for electrolysis—splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen is to be captured and stored for later use in two massive salt caverns, an innovative storage method. According to LPO, when complete, the project could help prevent 126,517 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually.

Sources: GAO analysis of LPO information; ACES Delta, LLC; (image). | GAO‑25‑106631 |

Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP). This program, established by the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and first funded by Congress in 2017, is to provide loans and loan guarantees to federally recognized Indian Tribes, including Alaska Native villages or regional and village corporations, for energy development.[11] It also lends and provides guarantees to tribal energy development organizations that are wholly or substantially owned by a federally recognized Tribe or an Alaska Native village.[12] TEFP is to support a broad range of projects and activities for the development of energy resources, products, and services that use commercial technology.[13] For example, TEFP could be used to support electricity generation, transmission, or distribution facilities using renewable or conventional energy sources; energy resource extraction, refining, or processing facilities; or energy storage facilities. Eligible projects can be located on or off tribal land.[14]

|

Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP): Example Project In September 2024, the Loan Programs Office (LPO) announced a $72.8 million partial loan guarantee for the development of the Viejas Microgrid, a solar energy plus long-duration storage microgrid on the tribal lands of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians in California. The project seeks to provide the Viejas Band reliable, utility-scale renewable energy generation and storage infrastructure by installing new solar energy generation and long-duration energy storage systems. When the installation is complete, the Tribe should benefit from lower energy costs, according to LPO.

Sources: GAO analysis of LPO information; Viejas Enterprise Microgrid (photo). | GAO‑25‑106631 |

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Program (ATVM). This program, established by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, provides loans to manufacture more fuel-efficient vehicles or components.[15] Several types of vehicles are eligible under the program, including light-, medium-, and heavy-duty vehicles, locomotives, maritime vessels, and aircraft. To be eligible, a project must be located in the U.S. It must also build new facilities; reequip, modernize, or expand existing facilities; or perform engineering integration related to the manufacturing of eligible components.

|

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Program (ATVM): Example Project In December 2022, the Loan Programs Office (LPO) announced a $2.5 billion direct loan to Ultium Cells, LLC, to support the construction of new lithium-ion battery cell manufacturing facilities in Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee. These new cells can be used in a variety of vehicles, including work trucks, and are expected to expand electric vehicles’ range at a lower cost. LPO estimates that, when construction is complete, these new battery cells could reduce gasoline use by 480 million gallons per year.

Sources: GAO analysis of LPO information; Ultium Cells, LLC (photo). | GAO-25-106631 |

Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Program (CIFIA). This program was established in 2021 by the IIJA and provides loans and loan guarantees for carbon dioxide transport projects—such as pipelines, shipping, or rail—whose services are provided to public companies for a fee.[16] Eligible transport projects could include those that support carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and storage by providing the transportation link between the point of capture and carbon dioxide conversion facilities where it will be used, or wells where it will be stored. The carbon dioxide for these projects must be captured from human-generated sources or the ambient air.[17]

Title XVII Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program (Section 1706). Section 1706, established in 2022 by the IRA, provides loan guarantees for projects that (1) retool, repower, repurpose, or replace energy infrastructure that has ceased operations; or (2) enable operating energy infrastructure to avoid, reduce, utilize, or sequester air pollutants or greenhouse gas emissions.[18] To be eligible for the program, a project must be energy-related, located in the U.S., and involve technically viable and commercially ready technology.

|

Title XVII Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program (Section 1706): Example Project In September 2024, the Loan Programs Office (LPO) announced a $1.52 billion loan guarantee for Holtec Palisades, LLC to restore and repower their nuclear energy generation facility in Covert Township, Michigan. According to LPO, when completed, the project could avoid a total of 111 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions during the planned 25 years of the facility’s operations.

Sources: GAO analysis of LPO information; Holtec Palisades (photo). | GAO‑25‑106631 |

LPO’s Loan Authority and Credit Subsidy Costs

The total loan authority for each program, or the amount of loans and loan guarantees LPO may issue for each of the programs, is determined in one of two ways:

· Statutory cap on total loan authority. Congress may authorize a maximum amount for the loans or loan guarantees that can be made. LPO may not exceed this amount unless Congress amends the legislation.

· Appropriations for credit subsidy cost. LPO may also be limited by congressional appropriations for credit subsidy cost. LPO estimates the amount of loan authority it can support based on the dollar amount Congress appropriates for credit subsidy cost, and if that amount is lower than any statutory cap, LPO is limited by available appropriations.

The credit subsidy cost is the expected cost to the federal government of making a loan or loan guarantee. It is equal to the net present value of estimated cash flows from the government for the project, minus estimated cash flows to the government such as repayments on the loan. It is calculated over the life of a loan and excludes administrative costs. Federal agencies estimate subsidy costs as required under the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990.[19]

Loan and Loan Guarantee Application Review Process

LPO’s application review process is to ensure projects under all five programs meet program requirements and demonstrate a reasonable prospect of repayment.[20]

Before LPO receives an application, it offers a pre-application consultation with potential applicants to any of their programs. According to LPO information, the office encourages applicants to engage in no-fee, no-commitment consultations to discuss a proposed project. According to LPO, in these consultations, LPO will work with the applicant to determine whether their proposed project may be eligible for a loan or guarantee.

For the CIFIA program, however, potential applicants are required to submit a letter of interest that includes details related to the project, finances, and eligibility. LPO is to review the letter to determine if the project appears to meet the criteria specific to CIFIA and has a reasonable prospect of repayment, among other things. If LPO determines these criteria are met, LPO formally invites the potential applicant to submit an application.

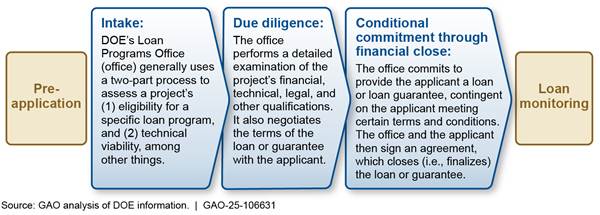

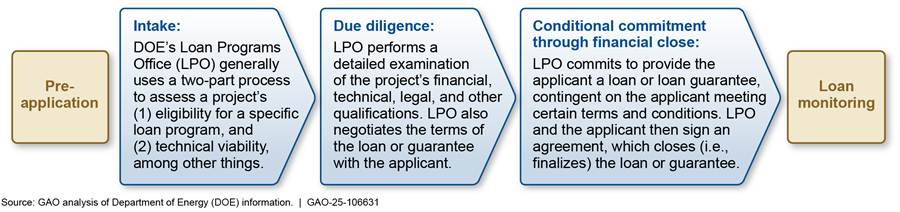

As shown in figure 1, LPO’s loan application review process includes three phases: intake, due diligence, and conditional commitment through financial close.

Intake. During intake, LPO generally uses a two-part process to assess an applicant’s eligibility for a specific loan program and the project’s viability. In part I, LPO determines a project’s eligibility based on requirements and relevant laws and regulations specific to the loan program. For example, for Section 1703 applications, LPO may review whether the project avoids, reduces, or sequesters air pollutants or greenhouse gases and employs new or significantly improved technologies. In part II, LPO assesses a project’s viability—the extent to which a project can perform adequately—against programmatic, technical, and financial criteria to determine whether to move forward with that project. For example, for ATVM loans, it weighs criteria such as an applicant’s technical readiness level, manufacturing plan, and corporate experience. According to LPO officials, all programs except ATVM complete part I before inviting an applicant to part II. In ATVM there is no separate invitation to part II. The intake stage concludes when an applicant accepts an invitation from LPO to proceed to the due diligence stage. Alternatively, LPO can reject an application, or an applicant can withdraw an application from consideration.

Due Diligence. During due diligence, LPO staff perform a more detailed examination of the project’s financial, technical, legal, and other qualifications. Specifically, LPO staff are to identify technical and project management risks and mitigation strategies, conduct a technical evaluation of the application, and propose technical terms and conditions for a potential loan.

Officials told us projects undergo full credit underwriting in due diligence. According to LPO officials, it uses an internal credit rating system, modeled on those used by private rating agencies, to evaluate each project. It uses a rating of CCC+ as an adjustable threshold or “soft floor” when determining a reasonable prospect of repayment. A rating of CCC+ currently implies about a 49 percent chance of default over 10 years, according to LPO documentation. According to LPO guidance, in most cases LPO commissions an independent engineer’s report to provide an independent technical review and assessment of the application in support of the due diligence process.[21] Specifically the independent engineer’s report is to cover the project’s technology maturity, financial merit, plant operation and maintenance, applicable licenses and permits, and risks and their mitigants, among other things. The information in the independent engineer’s report is used to develop the inputs to the term sheet, among other things.

LPO negotiates the financial terms of the loan or loan guarantee with the applicant. Financial terms can define the loan or loan guarantee amount, interest rates, maturity, and any applicable fees. LPO also often identifies technical monitoring requirements during due diligence.

According to LPO guidance and information, when the proposed loan or loan guarantee enters the interagency review process, it is submitted for review and approval by (1) the Office of Management and Budget, which is to review LPO’s estimated credit subsidy cost for each application, and (2) the Department of the Treasury, which reviews the transaction. Next, DOE’s Credit Review Board is briefed on pending transactions and votes on whether to move forward.[22] If the application is approved by the Credit Review Board, the Secretary of Energy decides whether to offer a conditional commitment to the applicant.

Conditional Commitment through Financial Close. Following the Secretary of Energy’s approval, LPO commits to provide the applicant a loan or loan guarantee, contingent on the applicant meeting certain terms and conditions. According to LPO documentation, examples of these terms and conditions include confirming project performance targets, providing a project management plan and risk mitigation plan, and certifying that the project will proceed using the identified construction budget. LPO and the applicant then sign an agreement which closes the loan or guarantee, and the applicant is able to draw on the loan, subject to the terms and conditions of the agreement.

According to LPO, once a loan closes, LPO monitors the loan until it is paid off. This monitoring includes assessments of performance against the project’s schedule and budget, according to agency documentation.

LPO Is Managing Program Expansion but Has Not Met Application Review Targets

LPO has taken steps to address the expanded number of loan programs, billions of dollars in greater loan authority, and an increased number of loan applications. Together, these changes have increased the risks of financial loss inherent in these programs. At the same time, LPO has not met its targets for the number of applications reviewed, and reviews are taking longer than in the past. LPO has identified reasons for longer review times and taken steps to address them.

LPO is Managing Programs Through a Period of Change and Increased Industry Interest

Recent legislation expanded the number of loan programs LPO administers from three to five, increased LPO’s loan authority many times over, and triggered significant changes in how the existing programs operate.

The two new programs are CIFIA, established by the IIJA in November 2021, and Section 1706, established by the IRA in August 2022. To fully implement these programs, LPO needed to develop and publish program guidance for staff and potential applicants. LPO published CIFIA guidance in October 2022 and updated its Title XVII regulations to reflect Section 1706 in an interim final rule in May 2023.[23]

Together, the IIJA and IRA also increased LPO’s loan authority from approximately $40 billion to over $400 billion, with much of this new authority expiring by September 30, 2028. Specifically,

· $290 billion of loan authority that expires September 30, 2026—$40 billion for Section 1703, and $250 billion for Section 1706.[24]

· $40 billion of ATVM loan authority and the appropriation underlying $18 billion loan authority for TEFP that expires September 30, 2028.[25]

The remaining $20 billion in new loan authority is for CIFIA and does not expire.[26]

Changes enacted in the Energy Act of 2020, the IIJA, and the IRA triggered significant procedural, administrative, organizational, and staffing changes to how LPO carries out its programs.[27]

Procedural. These changes include additional requirements or changes to application review procedures. For example, the IRA and LPO established that applicants to Section 1706 and Section 1703 are to develop a community benefits plan, which is to define how a project will engage with and affect associated communities.[28] According to officials, LPO also requires these plans from applicants to the other three loan guarantee programs. Project applications also must show that benefits of participation in the program will be passed on to these communities.

In addition, the IIJA and IRA expanded the eligibility or coverage of the programs. For example, the IIJA expanded the eligibility under ATVM to include medium- and heavy-duty vehicles and expanded Section 1703 to include loan guarantees for projects that receive support from state energy financing institutions.[29] These changes in eligibility required LPO to update its internal and external guidance and application review procedures.

Administrative. These changes include authorizing borrowers to apply for direct loans and eliminating or revising fees that applicants pay in some cases. For example, since March 2022, Congress granted LPO the authority to offer direct loans under TEFP.[30] Previously, LPO could only offer loan guarantees under that program.[31] In addition, in May 2022, LPO revised TEFP policy to eliminate several fees that applicants previously had to pay, including application and facility fees. According to LPO documentation, these fees were a significant impediment to using the program. Similarly, in 2023, LPO revised its guidance to remove application fees for the two Title XVII programs.

Organizational. These changes include re-organized responsibilities in administering the five programs. For example, in 2021, in response to statutory changes made by the Energy Act of 2020, LPO established the Outreach and Business Development Division to identify prospective program applicants. According to LPO documentation, this division is primarily responsible for completing the intake phase of the application review process. Further, the addition of CIFIA and Section 1706 in the IIJA and the IRA have added to or changed some staff responsibilities.

Staffing. These changes include increasing staff positions to address the increased workload from new authorities. The number of filled positions increased from 104 federal and contractor staff in May 2020 to 412 in October 2024, including part time staff, according to LPO documentation. However, as of October 2024, LPO continued to have a vacancy rate of 18 percent in its offices that conduct application reviews. LPO relied on contractors to complete key aspects of the application review process, particularly the intake phase.

LPO Has Not Met Its Application Review Targets

Since 2020, industry interest in DOE loan programs has increased substantially, as measured by the number of applications submitted. The average number of applications LPO received increased from approximately 10 per year in 2016 through 2020, to over 80 per year in 2021 through September 2024. The majority of applications from 2021 through September 2024, 78 percent, were submitted to the Section 1703 and ATVM programs.

Given the context of an increase in applications, LPO set internal targets for the number of applications it would review in calendar years 2022, 2023, and 2024. Specifically, they set targets for the number of applications achieving (1) conditional commitment, and (2) financial close. For example, LPO expected to review and offer conditional commitment for at least 36 applications in 2023 and to close 17 loans, according to LPO documentation and officials.[32]

As shown in table 1 below, LPO did not meet the targets it set from 2022 through 2024. In several cases, LPO fell well short of meeting its targets. LPO offered conditional commitments to nine applicants in 2023 and closed on one guarantee, falling short of its targets.

Table 1: Loan Programs Office (LPO) Application Review and Financial Close Targets and Actual Performance, Calendar Years 2022 to 2024

|

|

Number of applications achieving conditional commitmenta |

Number of applications achieving financial close |

||

|

Year |

Target |

Actual |

Targetb |

Actual |

|

2022 |

More than 9 |

4 |

No target established |

3 |

|

2023 |

More than 36 |

9 |

17 |

1 |

|

2024 |

More than 36 |

12c |

47 |

3c |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Energy data and documentation. I GAO‑25‑106631

aAccording to LPO officials we interviewed, the application review target is reached when a project completes due diligence and enters the interagency review process, which immediately precedes the start of the conditional commitment phase.

bLPO officials established these goals in 2022. However, officials stated that LPO currently does not have annual targets for the number of applications achieving financial close.

cData through September 30, 2024.

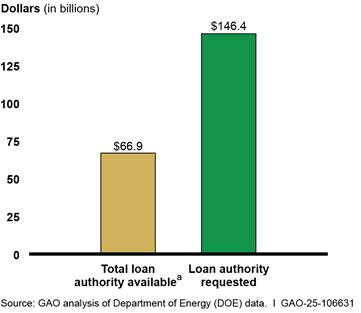

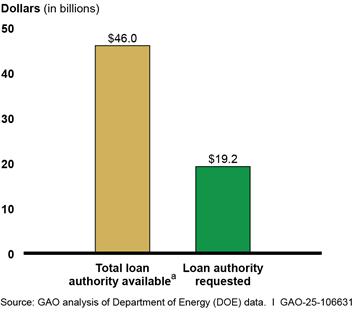

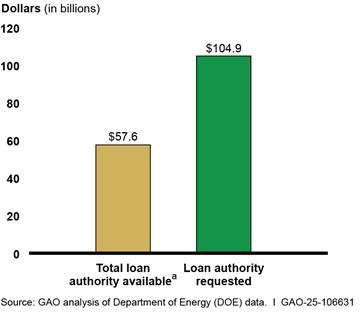

At this rate, LPO would not be on track to issue loans in the amounts Congress authorized before nearly $350 billion of that loan authority expires in 2026 and 2028. For example, Congress authorized $250 billion in loan authority for Section 1706 that is due to expire September 30, 2026. As of September 30, 2024, LPO had closed one loan for this program for about $1.4 billion. While it has a total of $108.3 billion in outstanding submitted applications for loans and guarantees, the program almost certainly will fall short of the $250 billion in loan authority.

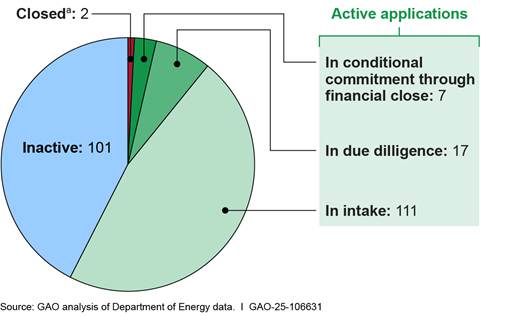

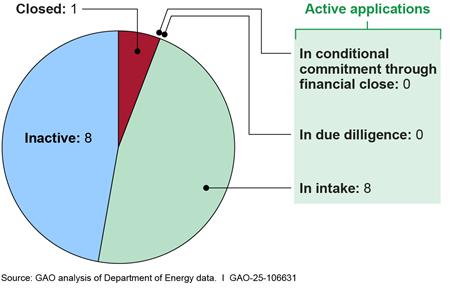

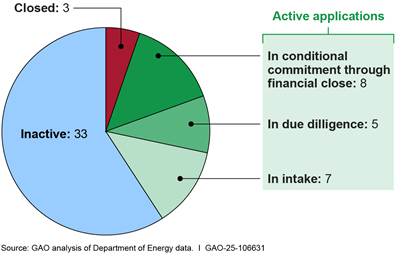

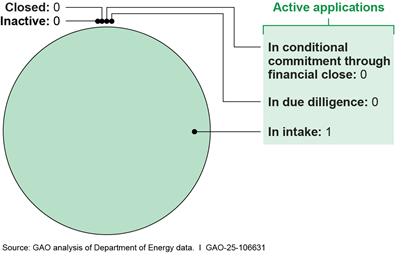

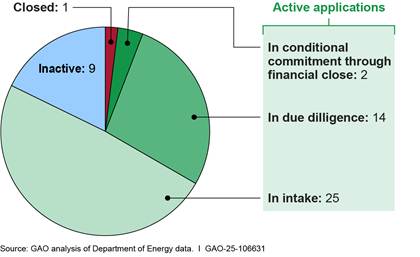

As of September 30, 2024, among the applications submitted in 2016 through September 2024, LPO had a queue of 205 active applications in the review process, and 22 applications on hold. It had closed 10 loans or loan guarantees, including three before 2022.[33] As shown in table 2, of these active applications, about 74 percent (152 applications) were in the intake phase, roughly 18 percent (36 applications) were in the due diligence phase, and the remaining 8 percent (17 applications) were in the conditional commitment through financial close phase. The 205 active applications had a potential loan or guarantee value of $299.9 billion. The 17 that had reached conditional commitment had a potential loan or guarantee value of $24.9 billion.

Table 2: Loan Programs Office Pipeline of Applications Submitted Since January 2016, by Program and Phase, as of September 30, 2024

|

|

Title XVII Clean Energy Financing Program (Section 1703) |

Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP) |

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Program (ATVM) |

Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Program (CIFIA) |

Title XVII Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program (Section 1706) |

|

Number (value, billions) of applications in intake |

111 ($119.0) |

8 ($4.2) |

7 ($4.3) |

1 ($0.2) |

25 ($42.2) |

|

Number (value, billions) of applications in due diligence |

17 ($27.4) |

0 ($0) |

5 ($14.9) |

0 ($0) |

14 ($62.7) |

|

Number (value, billions) of applications with conditional commitment |

7 ($5.0) |

0 ($0) |

8 ($17.3) |

0 ($0) |

2 ($2.6) |

|

Total (value, billions) of loans in pipeline |

135 ($151.4) |

8 ($4.2) |

20 ($36.6) |

1 ($0.2) |

41 ($107.5) |

|

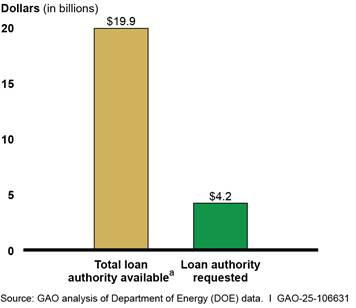

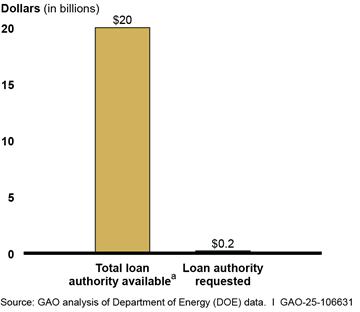

Loan authority available (billions)a |

$66.9b |

$19.9b |

$46.0c |

$20.0c |

$57.6c |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Energy documentation and data. I GAO‑25‑106631

Note: This table excludes inactive applications, which are project applications that were rejected, withdrawn, abandoned, or are otherwise on-hold. As of September 2024, Section 1703 has 101 inactive applications; TEFP has 8 inactive applications; ATVM has 33 inactive applications; and CIFIA has 0 inactive applications; and Section 1706 has 9 inactive applications.

aTotals may not sum due to rounding. Amount reduced to include applications that have received a conditional commitment.

bStatutorily established loan authority remaining.

cLPO estimate based on remaining appropriation for credit subsidy cost available as of September 30, 2024.

Since the programs began through September 2024, four programs had closed loans

or loan guarantees for a total of 13 projects with a combined obligated value

of $28.1 billion (see table 3). LPO closed its first loan under Section 1706

for about $1.4 billion in July 2024 and its first loan guarantee under TEFP for

$100 million in August 2024. As of September 30, 2024, CIFIA, a newer program,

had yet to close a loan or loan guarantee.

Table 3: Summary of Obligations for All Projects that Reached Financial Close, by Program, through September 2024

|

Phase |

Title XVII Clean Energy Financing Program (Section 1703) |

Tribal Energy Financing Program |

Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Program |

Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Financing and Innovation Act Program |

Title XVII Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program (Section 1706) |

|

Achieved financial close |

3 ($15.39 billion)a |

1 ($100 million) |

8 ($11.31 billion) |

0 ($0) |

1 ($1.35 billion) |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Energy data. I GAO‑25‑106631

aThe Loan Programs Office has closed on a total of 10 loans on the Vogtle nuclear power plant.

When compared to 2012, the last time we examined how long LPO took to review applications, we found that each of the three application review phases now took longer, based on our analysis of LPO data from January 2016 through September 2024.[34] The median time to complete each application review phase is from about 19 percent to 41 percent longer than in 2012 (see table 4.) Although we found it took longer now than in the past to review applications, there is no benchmark for how long a review should take. According to LPO officials, they do not have control over when they receive information from applicants. As a result, they have the most direct control over the work done in the due diligence phase, as compared to the intake phase when LPO relies more on receiving information from applicants.

Table 4: Median Number of Months to Complete Application Review Phases, 2006 to 2011 and 2016 to 2024

|

Phase |

2006–2011a |

2016–2024b |

Percent increase |

|

Complete intake phasec |

6.1 |

8.7 |

41 |

|

Complete due diligence phased |

9.8 |

11.7 |

19 |

|

Compete conditional commitment through financial close phasee |

4.2 |

5.4 |

27 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Energy data. I GAO‑25‑106631

Note: The number of months elapsed represents the median for the review period of those applications that proceeded to the next review stage. We believe the median is a better representation of the data for this table because it reduces the effect of some outliers that skew the data. The numbers have been rounded.

aWe reported the median number of days each application phase took to complete in GAO, DOE Loan Guarantees: Further Actions are Needed to Improve Tracking and Review of Applications, GAO‑12‑157 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 12, 2012). We reported on applications submitted through September 2011 that responded to solicitations the Loan Programs Office issued between 2006 through 2010.

bWe include in this review those active applications submitted from January 2016 through September 2024 that have completed at least one phase of the application review process.

cAmong the 60 applications that completed intake, the minimum number of months elapsed was 1.2 and the maximum number of months elapsed was 30.3, which excludes one application that switched programs mid review.

dAmong the 27 applications that completed due diligence, the minimum number of months elapsed was 5.3 and the maximum number of months elapsed was 18.8.

eAmong the 7 applications that completed conditional commitment through financial close, the minimum number of months elapsed was 1.8 and the maximum number of months elapsed was 11.4.

However, some loans closed more quickly than in the past. In particular, from January 2016 through September 2024, seven applications achieved financial close after LPO completed a full application review process. Among these seven, the median time to complete the process was quicker than we found in 2012.[35] The cumulative value of these seven completed loans or loan guarantees is $8.2 billion. According to LPO officials, the factors that led to the quicker review time for the applications that have achieved financial close included (1) better prepared applications submitted by applicants, (2) more experienced LPO staff working on those transactions, and (3) less time spent on negotiating the final terms of the loan or guarantee agreement. The application with the quickest review timeframe reached financial close in slightly more than 13 months. According to LPO officials, the shorter review time was because the applicant submitted a high-quality application to begin with and responded quickly to LPO’s requests for documents and data during the due diligence process.

LPO Has Identified Reasons for Longer Review Times and Taken Steps to Address Them

According to LPO officials, there are several reasons why each phase of the loan application review process is taking longer than it did in the past. Specifically, the high volume of applications submitted, the incompleteness and quality of the applications, the complexity of the proposed projects, and the time it takes applicants to respond to questions can each influence how long it takes LPO to review an application. For example, applicants may need assistance with environmental permits or time to raise equity before applications move out of the intake phase, which would increase the amount of time spent in that phase, according to LPO officials.

LPO has taken several steps to identify and address where application reviews are taking longer than expected, according to LPO officials. For example, LPO is adding data elements to its database to help the agency establish how long specific review steps take and where delays are occurring.[36] With this and other information on the challenges that applicants face, LPO officials said they will be able to provide applicants with coaching and assistance to help their applications move more quickly through the review process.

In addition, LPO has also changed some aspects of its application review procedures. For example, according to LPO documentation:

· LPO staff are to delay inviting applicants to the due diligence phase until LPO believes applicants are ready to move forward, including whether the applicant has lined up equity for the project.

· The rigor of LPO’s due diligence review will vary, depending on the type of project being proposed. For example, applications that have an established purchase agreement, and therefore, assured income—such as for clean electricity generated—will have a less complex review than those that do not. In contrast, innovative, technologically complex projects will receive higher levels of review—such as for the engineering or design of the project—than projects that are for technologies already in use in the U.S.

· LPO staff are to prioritize applications. First priority will be given to applications considered to be of high quality. Second priority will be projects that help LPO and DOE meet their policy goals, such as greenhouse gas emission reduction targets or the Justice40 program priorities and targets.[37]

LPO Substantially Increased Its Completion of Application Reviews and Closed Loans in the Last 3 Months of 2024

In the last 3 months of 2024, after we completed our full analysis of LPO’s loan activity, LPO issued substantially more conditional commitments and closed loans or loan guarantees. Our cutoff date for collecting and fully reviewing application data was September 30, 2024. In the 3 months following that, LPO reported that it offered conditional commitments for 13 new projects with an expected loan or loan guarantee value of $41.2 billion. In addition, LPO reported it closed 11 additional loans or loan guarantees with a combined value of $24.4 billion. The loans and guarantees LPO closed in the last quarter of calendar year 2024 account for about half of the total value of all loans and guarantees that LPO has closed for these five programs. Even with this substantial increase in value of closed loans, LPO is not likely to use all of its authority or appropriations prior to expiration. We included all of these recently acted-on applications in our analysis as of September 30, 2024, at the stage they were in at that time, so our earlier analysis remains valid.

Even with this increase in activity, LPO did not meet its targets for the number of applications reaching conditional commitment or financial close for 2022 through 2024. LPO officials told us they had shortened their due diligence processing times in 2024; however, we found the loans that closed after our review still took longer to complete the due diligence review (median of 11.7 months) than in 2012. LPO officials told us they think they can now proceed at a steady-state level of reviewing loan guarantee applications in keeping with their targets. However, it remains to be seen whether LPO can maintain a steady pace of approving sound applications.

See appendix II for a complete list of the conditional commitments and closed loans and guarantees made for each program since the program began through December 31, 2024.

LPO Guidance and Procedures Cannot Ensure Consistent and Accurate Application Reviews

LPO guidance and procedures cannot ensure application reviews are implemented consistently and accurately due to several reasons. First, LPO application review guidance contains inconsistences and is sometimes not clear, in part because it is out of date. Second, our review of application documents found some were missing, incomplete, or contained errors. Third, in one case LPO guidance does not follow the law. Fourth, LPO does not comprehensively assess its application review process to ensure consistency and accuracy, including reviewing whether guidance is up to date and application reviews are complete and accurate. Finally, LPO does not comprehensively identify application review training needs and does not assess the extent to which its application review training is effective.

Application Review Guidance Is Incorrect and Outdated

We found LPO’s application review guidance was outdated and does not always match practice. Further, when we spoke to LPO officials for clarification about the application review guidance, they sometimes provided us with inconsistent or incorrect information about the review process. We also found three application review templates that contained errors. Together, these inconsistencies and errors made it difficult to determine the correct application review procedures. Staff responsible for reviewing applications will likely face similar challenges when trying to adhere to the review procedures.

LPO’s application review guidance is not always correct. We found 11 instances in which LPO’s application review guidance refers to templates or documents that LPO officials told us do not exist or are not in use. For example, the conditional commitment guidance document for LPO’s Origination Division calls for the use of two templates LPO officials told us do not exist: a credit paper template and a project risk register template.[38] According to agency officials, when LPO developed the guidance, they thought a credit paper template would maximize processing efficiencies. However, they found a template would not be capable of capturing the nuances of LPO’s different loan programs and do not use one. Similarly, TEFP guidance calls for the drafting of a technical viability memo by the evaluating engineer to document the results of LPO’s technical viability evaluation.[39] However, officials we interviewed told us they do not create these memos. In addition, the Intake procedure document for CIFIA refers to several forms that officials told us are not used by LPO.[40] Officials told us these forms may have been included as an oversight when the agency used the procedure for Title XVII as a model to develop the CIFIA procedure. The officials also said that they were developing a plan to correct the guidance.

In three of the 11 instances, guidance continued to refer to documents that were used in the past but are no longer used. LPO guidance calls for the development of three related documents: a list of technical monitoring requirements in a table, a technical monitoring requirements table approval form, and a technical monitoring plan approval form.[41] We received the technical monitoring requirements table and the technical monitoring requirements table approval for some, but not all, of the applications we reviewed. According to officials, LPO now rolls the technical monitoring requirements table into another document and is taking steps to retire the two forms.

Guidance documents were at times contradictory or unclear. In one example, ATVM guidance states that part I and part II reviews are to be performed at the same time.[42] The same guidance also states that staff are to proceed to part II only after part I has been completed.[43] In another example, the requirements for developing a list of technical monitoring requirements are described differently in different guidance documents. One guidance document states that the list must include a title, intended purpose, and triggering date or event.[44] However, another guidance document does not list these three as required items. Instead, it calls for a responsible party, required completion date, and metrics.[45] Both call for a description and completion criteria. Staff may approach the list of requirements differently depending on which document they reference.

Officials sometimes gave inconsistent and incorrect information about application review procedures. In some cases, when we asked LPO officials to clarify application review procedures, their statements contradicted written procedure, practice, or other statements from LPO officials. Specifically, LPO officials told us at one time that a Part I Review Form is required only for CIFIA and not for the other four loan programs. This conflicted with other communications, guidance documents, and documentation we received. For example, the form is listed in guidance documents for the other programs. Further, officials later told us that a Part I Review Form is not required for CIFIA, directly contradicting the earlier statement that it is required for CIFIA.

In another case, in a written response to our questions, LPO officials provided conflicting information about the correct review procedure. LPO’s written response first stated that a federal project engineer is assigned to perform part I and II reviews for applications to all programs except ATVM, because ATVM does not have part I and II reviews. Later in the same document, LPO’s written response states that ATVM has part I and part II reviews that are completed by a federal project engineer. LPO officials told us that we may have received conflicting or inaccurate information from new staff, or because of recent changes to the application process as LPO’s programs have expanded.

Some application review templates have errors. We found errors in three application review spreadsheet templates. The Title XVII Part II Financial Score Form is a spreadsheet with formulas that automatically average scores entered by LPO staff. In one instance, we found an error in the formula, so that when staff recorded “not applicable” as an entry, the spreadsheet automatically returned a score of zero instead of removing the entry from the calculation. According to the form, a score of zero signifies a project is “materially deficient” in a category, which is not the same as “not applicable.” As a result of this error, one project received a score of 2.2 out of a possible 5 points for the project sponsor’s financial and managerial capability. When the not applicable entry is appropriately factored into the calculation the score is 2.75. The same project received a score of 2.14 instead of 2.5 for the creditworthiness and financial viability of the project because of this error.

We also found one spreadsheet had overlapping rating scales, so that the same score could fit into two credit rating categories, while another had scales that did not include all possible scores, so it was not clear where some scores fit. The ATVM Internal Risk Rating and Recovery Matrix form calculates a preliminary credit rating, and the scale places scores from 1.6 through 2.6 at a “CCC” rating and scores from 2.6 through 3.6 at a “B” rating, which indicates less risk. One project in our sample had a score of 2.6, which could be a “CCC” or a “B” rating under this scale. The same issue of overlapping scores occurs elsewhere in the ATVM Internal Risk Rating and Recovery Matrix form. Additionally, the Section 1703 Internal Risk and Recovery Rate Matrix form has scales that do not include every score. As a result, in one instance, a score of 7.1 was between two categories.

LPO is updating its guidance, but errors remain. LPO officials we interviewed told us they began updating their application review guidance to reflect recent changes in December 2022 and completed the update in October 2024. However, the update did not address all the errors we found during our review. Some of the examples noted above were from guidance updated or written during the most recent update period. Accordingly, it is unknown when guidance will be accurate, complete, and consistent.

Guidance errors and inconsistencies make it difficult to consistently and accurately review applications. Specifically, contradictory and unclear guidance that does not match LPO application review practices will make it more difficult for staff—particularly new staff—to consistently and accurately follow procedures. Further, when we tried to clarify the guidance with LPO staff, we sometimes received inconsistent or incorrect information. If staff receive inconsistent or incorrect information, it could also make it difficult for them to consistently and accurately follow procedure. Additionally, template errors that lead to incorrect measures of creditworthiness result in LPO using inaccurate information for application reviews, while overlapping preliminary credit rating scales make it unclear which preliminary credit rating is accurate.

Application Review Documents Were Incomplete, Missing, and Contained Errors

In our examination of 283 application review documents from our nongeneralizable sample of 23 loan or loan guarantee applications, we found examples of incomplete documents, missing documents, documents for which it was unclear if they had been signed by the proper official, and documents that contained technical errors. Without consistently completing and reviewing application review documents, LPO may not be able to ensure consistency and accuracy in its reviews. For more information on how we selected documents to review, see appendix I.

Incomplete documents. Of the 283 application review documents we examined, 23 were incomplete. We found a variety of ways in which the documents were incomplete, including fields in forms that were not fully or clearly completed and documents that contained unaddressed comments or tracked changes by LPO staff that made it unclear whether a document had been finalized.

Of the 23 incomplete documents, we found 21 had a field or fields that were not fully or clearly filled out. However, LPO officials told us they considered 17 of the 21 to be complete. For example, we found fields to describe how scores were determined were left blank in three Part II Financial Score Forms. According to LPO, this document determines the project’s creditworthiness and financial viability and the applicant’s financial and managerial capabilities. LPO officials told us they considered these forms complete. However, in contrast, documents of this type for other applications we reviewed were completely filled out with explanations of why a rating was selected. By not completely filling out this document, the reasoning for these determinations is unclear.

In another example, a check box on a form used to document the reviewer’s determination of whether a project was eligible for the program to which it applied was not checked. However, LPO officials noted that the narrative on the form stated the project is eligible. In another instance, a form did not have a reviewer name and date listed, which LPO officials told us was considered a clerical error.

Finally, we found four documents that were incomplete because they had unaddressed comments or tracked changes, two of which also had fields that were not fully or clearly filled out. Among these four, one was a review document that contained multiple tracked changes made by a different person after the reviewer signed off on the document, making it unclear whether the reviewer of the document saw or approved of the edits. The tracked changes included changing or adding new information to the document, and a change to the reviewer date. LPO told us that they considered this document complete. In two other cases, documents contained unaddressed comments. In the last case, briefing slides used by the LPO to brief the Credit Review Board included changes throughout.

Missing documents. In addition to the 283 documents we reviewed, we could not find two documents that should have been completed. Both of these were part of the same Section 1706 application. Both documents were from the intake phase of the application review process and were intended to document LPO’s determination that a project was technically eligible for the Section 1706 program. According to LPO officials, the documents were not created because of “heavily detailed technical requirements” and “the fact that LPO wanted this loan application to proceed.” Therefore, the eligibility review was incorporated into the part II review, which is typically used to evaluate the viability of a project. The part II review for this project discusses eligibility, but without the standard eligibility review it is not clear whether the same analysis was done for this project as for other projects. Additionally, LPO’s explanation of why it deviated from the standard application procedure suggests selected projects could be fast-tracked to avoid certain requirements.

Unclear signatures. We found 15 documents out of the 283 we reviewed for which it was unclear if the correct official signed the document. These documents were either missing a signature or it was not clear to us whether they had been signed by the correct official. For example, one internal memo used to document concurrence among key officials—including the Secretary of Energy—on moving an applicant to the next phase of the review process was missing signatures from two senior LPO officials and the Secretary of Energy or the Secretary’s authorized designee. In another of these memos, we also found that the Secretary of Energy or their designee did not sign the document as called for in LPO’s guidance.[46] In another example, a form used to document the applicant’s technical viability during the intake phase was missing a signature by a senior LPO official. Without signatures, it was not clear to us whether the correct officials had reviewed and approved these documents and decisions.

Additionally, we could not determine whether the correct LPO officials signed the director concurrence for applications at the due diligence phase of the application process in eight out of nine cases.[47] According to LPO officials, director concurrence is used to document sign-off on a package of documentation needed to approve due diligence. According to LPO officials, the concurrence is to be signed by the following seven LPO officials: Deputy Director, Chief Investment Officer, Chief Operating Officer, Director of the Risk Management Division, Director of the Origination Division, Director of the Technical and Environmental Division, and Chief Counsel. Other designees may only sign when one of these officials is unavailable and a memo of delegation of authority is in place. In our review, we found that five of the nine concurrences we reviewed only had six signatures.

Further, none of the concurrences identified the title of the official, so we were unable to determine whether the required officials had concurred on the decision in instances when the person who signed was no longer working at LPO or changed positions. LPO officials told us that there is no check in the application review process to ensure that all relevant directors concurred. It is possible the correct officials signed, but we could not verify the names we saw were the correct officials at the time of the signatures.

Technical errors. We also found technical errors in 10 application review documents, including chemistry and mathematical errors. LPO or the independent engineers that provide an independent technical review and assessment of projects did not always follow standard naming or chemical formula conventions, resulting in incorrect information in the reviews of some applications.[48] For example, we found two examples of incorrect chemical formulas in LPO presentations to the DOE Credit Review Board. We also found incorrect chemical names in a technical viability review form in that they did not follow the accepted naming convention.

In addition, nine of the 23 applications we reviewed included an independent engineer’s report as one of the application review documents, and of these nine independent reports, five had chemistry-related errors. Specifically, we found examples of incorrect chemical formulas and incorrect chemical symbols. For example, one report incorrectly used the symbol Ma for manganese, instead of Mn. Similarly, another report incorrectly used the symbol FL instead of F for fluorine in the chemical formula for hydrofluoric acid. According to LPO, officials expect independent engineers to provide LPO with high quality, error-free reports that require limited review by LPO. The LPO division directors review the reports only for errors deemed substantive; however, LPO officials told us that, with the increase in application submissions, staff have less time to critically review each report to identify substantive issues for management review. Such errors may raise questions about the quality and thoroughness of other aspects of these independent engineer’s reports.

We also found mathematical errors in our analysis of LPO application review documents. Specifically, we found two instances in which LPO staff miscalculated scores on technical viability forms. These scores rate the application against criteria in areas such as technical merit and environmental benefits. In one case, the document lists an overall score of 476, instead of the correct 449. Although both are considered passing scores, similar miscalculations have the potential to produce incorrect determinations on whether an applicant meets certain criteria related to the project’s technical viability.

LPO reviews application review documents, but errors remain. LPO officials told us they generally use a “doer and reviewer” approach to application review documents. Officials said various steps are assigned to one staff person to complete, and then reviewed and approved by someone in a supervisory position. To ensure staff are trained on current procedures, officials said LPO pairs new hires with experienced staff. If there is deviation in how policies and procedures are followed, LPO has regular staff meetings to discuss policies and procedures. Nevertheless, we found errors, including on documents that had a supervisory signature.

Application review documents that are incomplete or contain errors make it difficult to ensure consistent and accurate reviews. LPO officials noted that they judge a document as substantially complete based in part on the importance of the missing information and can follow up to ask for information later in the process. However, if forms are not filled in completely and with similar information, it could be difficult for staff to consistently find and use information across applications. Reviewers also may not be able to understand the reasoning behind decisions or internal scores and ratings that feed into the decision on whether to offer a loan or guarantee if explanations are not clear. Finally, technical or mathematical errors that are not caught and corrected may make it difficult to consistently and accurately evaluate applications. As a result, LPO decisions about the merits of an application may be based on erroneous or incomplete information.

The Section 1703 Application Review Guidance Does Not Require DOE To Confirm Innovativeness at the Time of Commitment

As previously discussed, to be statutorily eligible for a loan or loan guarantee under the Section 1703 program, a project must use new or significantly improved technologies compared to technologies in general commercial use in the U.S.[49] DOE’s regulations implementing this requirement call for eligible projects to be deemed innovative at the time LPO offers the term sheet that details the final terms of the loan or guarantee to be agreed upon by LPO and the applicant.[50]

However, according to LPO guidance and officials, LPO determines whether a project is innovative during the intake phase of the application process in the part I review. LPO officials said they determine whether an application is innovative during the intake phase so that applicants will know whether they qualify for the program before moving forward. This is earlier than at the time the term sheet is issued. For the two 1703 projects we reviewed, at least 11 months elapsed between LPO’s part I review, when it makes its innovativeness determinations, and when the term sheet was issued, according to agency data.

There is no provision in LPO’s application review guidance for project eligibility to be reevaluated to address any changes in the project or the commercial technologies between the time LPO determines the technologies’ innovativeness and the time LPO offers the final terms of the loan or guarantee to the applicant. For one Section 1703 project we reviewed, we found the project’s proposed technology changed significantly between the part I review and the time the project reached financial close. In particular, the applicant did not implement several software functions or features that experts at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory deemed innovative in the project’s technology, potentially affecting whether the project would still be deemed innovative without those features. According to officials, the final software technology was not reviewed to determine if it was innovative at the time the term sheet was issued or the loan guarantee was issued. LPO officials stated that they do not re-assess the technologies unless an applicant notifies LPO of a change in the technology. Without reassessing project applications for innovativeness when the term sheet is issued, LPO risks guaranteeing loans for projects that no longer meet eligibility requirements.

LPO Does Not Comprehensively Assess Its Application Review Process to Ensure Consistency and Accuracy

We found that LPO does not conduct a comprehensive review of its application process, including a review of guidance and application review documents. This contrasts with LPO’s portfolio management division, which conducts a comprehensive review of its loan monitoring process at least annually.[51] The annual portfolio management division review includes a continuous improvement loop wherein LPO evaluates any deficiencies identified, determines appropriate corrective actions on a timely basis to remedy the deficiency, and evaluates the effectiveness of previously implemented remedies. LPO documentation shows that through this process the Portfolio Management Division has regularly identified and corrected issues in the loan monitoring process. Officials told us they have not conducted similar reviews of the application review process because they did not until recently consider this a high-risk area.

We have identified problems with LPO’s guidance and procedures and recommended updates to reflect current application review practices. However, problems persist, and an annual, comprehensive review of LPO’s entire application process with a continuous improvement loop could help ensure LPO addresses its deficiencies in guidance and application document review. By doing it annually in a transparent manner, LPO could also help ensure consistency in implementing guidance updates.

LPO Does Not Comprehensively Identify Its Training Needs or Assess the Effectiveness of Its Training Program Regarding Application Reviews

LPO officials told us they take steps to provide training, identify training topics, and evaluate training that staff receive regarding following established policy for application reviews.

· Provide training. LPO uses a variety of approaches to provide training to federal and contractor staff—such as new-hire orientations, brown bags, role-specific trainings provided by external experts, informal mentor-mentee relationships for new staff, and in all-hands staff meetings, according to LPO officials and documentation. For example, following a recent consultant’s review of how LPO can prioritize quality applications to move through the application review process, LPO management made several significant changes to guidance and procedures for application reviews and conveyed these changes to staff during an all-hands meeting in January 2024. In addition, LPO provided role-specific training for application review team leads.

· Identify training topics. LPO uses several mechanisms—such as a working group, staff requests, and input from senior management—to identify topics for training staff on application review procedures, according to officials. For example, LPO has established mechanisms where staff can request training or identify their training needs. Specifically, staff may request a brownbag training, fill in a weekly training needs survey, or develop an individual development plan that identifies specific training needs to conduct application reviews. However, as of May 2024, 74 percent of staff had not started an Individual Development Plan, 11 percent were preparing one, and nearly 9 percent had an approved plan, according to LPO documentation.

· Evaluate training. LPO evaluation of training focuses on knowledge checks and participant satisfaction surveys, often conducted at the conclusion of a training event, according to LPO officials and documentation. According to LPO officials, LPO offers feedback surveys, quizzes, or assessments at the end of many of their trainings to evaluate the training or staff development activities.

However, as the application review shortcomings presented above demonstrate, LPO’s efforts have not comprehensively identified training needs or evaluated the extent to which staff training has been put into practice to effectively reduce errors in application reviews. While LPO officials told us that they take steps to hire knowledgeable and experienced staff, they acknowledged existing staff may not understand the details of LPO’s new programs or recent changes to existing programs. In addition, we found that the significant number of new staff will likely need training on current procedures to follow in their application reviews.

We previously reported that agencies need to identify the most important training needs and resources that can address those needs.[52] In addition, agencies need credible information on how training programs affect organizational performance and goal attainment, such as efficient and consistent review of applications leading to closed loans. Without a comprehensive understanding of staff’s application review training needs or the outcomes of such training provided, LPO does not know if their training provides new and existing staff with the skills and knowledge to follow recently updated procedures accurately.

Conclusions

Providing billions of dollars in loans and loan guarantees to innovative and other high-impact energy-related ventures that private lenders will not make involves the risk of financial loss. In the last several years, the addition of two new loan programs and significantly higher loan authority and funding have challenged LPO in balancing increased financial risk with endeavoring to approve loans and guarantees on the scale Congress envisioned. In response, LPO published new rules, reviewed and revised existing guidance, issued new guidance, added hundreds of staff positions, and provided training.

Although LPO substantially increased the number of loans it closed in the last 3 months of 2024, it is not on track to use the full extent of the loan authority Congress provided. At the same time, shortcomings with LPO’s guidance, documentation, and training for reviewing loan applications raise questions about the extent to which LPO is reviewing applications accurately and effectively, including being consistent with law. These weaknesses suggest a measured approval pace is warranted until the agency implements needed improvements.

Without addressing needed improvements in loan application reviews, LPO risks making billions of dollars in loans and guarantees for ineligible projects. Use of an annual review mechanism such as that implemented by LPO’s Portfolio Management Division could help jump start LPO’s needed corrective actions. Thus, LPO could better ensure application reviews lead to selecting projects that further program goals.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider making changes to the authority for LPO’s five loan programs or reducing appropriations to reflect what LPO is likely to use before the authority expires. (Matter 1)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following four recommendations to LPO:

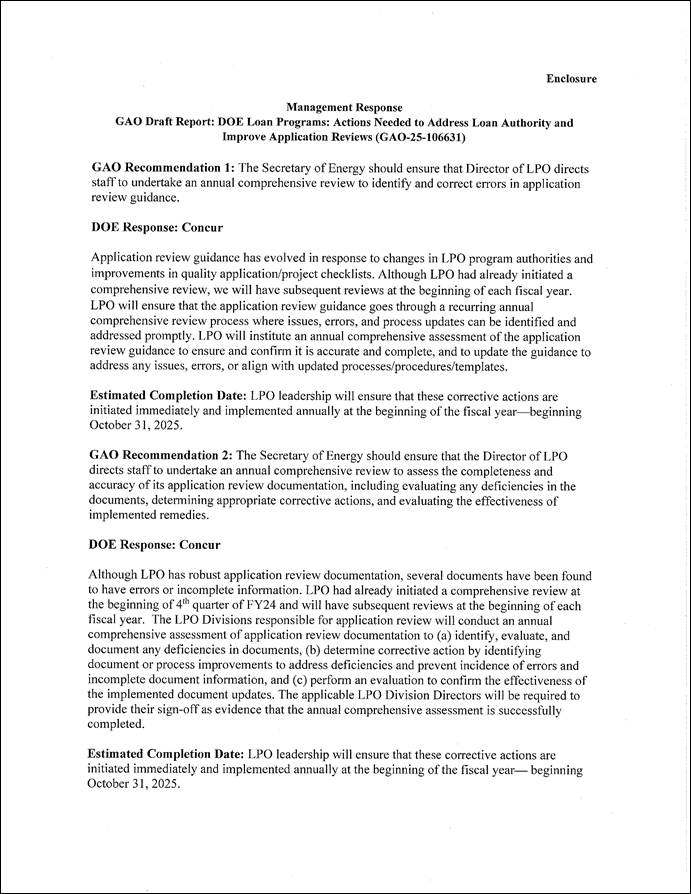

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that the Director of LPO directs staff to undertake an annual comprehensive review to identify and correct errors in application review guidance. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that the Director of LPO directs staff to undertake an annual comprehensive review to assess the completeness and accuracy of its application review documentation, including evaluating any deficiencies in the documents, determining appropriate corrective actions, and evaluating the effectiveness of implemented remedies. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that the Director of LPO directs staff to undertake an annual comprehensive review to identify application review training needs and to evaluate the extent to which training addressed deficiencies. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that the Director of LPO updates application review guidance for Section 1703 loans to include an evaluation of whether a project qualifies as innovative at the time the term sheet is issued. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOE for its review and comment. In response, DOE provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendix III. In its response, DOE concurred with our first three recommendations on conducting annual comprehensive reviews of (1) LPO’s application review guidance, (2) application review documentation, and (3) training needs. DOE also described steps it will take to implement these recommendations.

DOE did not concur with our fourth recommendation on updating LPO’s application review guidance for Section 1703 loans to include an evaluation of whether a project qualifies as innovative at the time a term sheet is issued. This recommendation would ensure LPO is following DOE regulations that implement the law by calling for eligible projects to be deemed innovative at the time LPO offers the term sheet to an applicant.

In its written comments, DOE stated several reasons for disagreeing with the recommendation. Specifically:

· DOE claimed that LPO’s process already ensures a project is innovative at the appropriate phases of the application review process, making the recommendation unnecessary. DOE also stated that we did not account for steps of the LPO underwriting process, including a review of the innovative technology prior to offering an applicant a term sheet and prior to the financial close of a loan guarantee.

· DOE stated that an additional evaluation would cause delays and potentially create an unnecessary burden for applicants.

· DOE stated that it disagreed with our statement in the report that, for one project, “the final software technology was not reviewed to determine if it was innovative at the time the term sheet was issued or the loan guarantee was issued.”

However, we continue to believe our recommendation is necessary to ensure that approved Section 1703 projects comply with the law. Specifically:

· We found LPO’s process did not ensure a project is innovative at the time a term sheet is issued, as required by DOE regulations implementing the law. According to LPO, the determination of whether a project is innovative happens during its part I review, which occurs early in the application review process, before LPO conducts full due diligence and several months before a term sheet is issued.

We reviewed LPO’s application review process from beginning (intake) to end (financial close) and found no provision in LPO’s application review guidance for a project to be reevaluated to ensure it remains innovative at the time the term sheet is offered. We also reported that LPO officials told us the office does not reassess the technology for innovativeness after part I unless an applicant notifies LPO of a change in the project’s technology.