IDENTITY VERIFICATION

GSA Needs to Address NIST Guidance, Technical Issues, and Lessons Learned

Report to Congressional Requesters

October 2024

GAO-25-106640

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106640. For more information, contact Marisol Cruz Cain at (202) 512-5017 or CruzCainM@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106640, a report to congressional requesters

October 2024

IDENTITY VERIFICATION

GSA Needs to Address NIST Guidance, Technical Issues, and Lessons Learned

Why GAO Did This Study

GSA established Login.gov as an identity proofing system that is used to access federal agencies’ websites with the same username and password. In 2017, NIST developed technical guidelines for federal agencies to follow when implementing digital identity services. However, in 2023, GSA’s Inspector General reported that Login.gov was not fully aligned with NIST’s guidelines.

GAO was asked to review Login.gov. This report examines (1) how Login.gov collects, shares, and protects PII while providing identity proofing services, (2) how many of the 24 CFO Act agencies use Login.gov and what benefits and challenges the agencies have reported, (3) the actions GSA is taking to align Login.gov with NIST’s Digital Identity Guidelines, and (4) the extent to which GSA’s actions are aligned with leading practices for pilot programs.

To do so, GAO reviewed documentation describing Login.gov’s identity proofing processes and efforts to align the system with NIST guidelines, compared Login.gov’s project plans to GAO’s leading practices for pilot programs, and conducted interviews with agency officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to GSA to address NIST digital identity guidance, agency identified technical issues, and lessons learned from its ongoing pilot. GSA concurred with each of the three recommendations. Just prior to issuing this report, GSA took action to address one of the recommendations.

What GAO Found

Login.gov collects a variety of personally identifiable information (PII) from users accessing government applications and websites. After collecting PII from users, Login.gov shares the data with multiple third-party vendors to determine whether users’ claimed identity is their real identity. Login.gov uses a range of methods to protect collected and shared PII, such as multi-factor authentication.

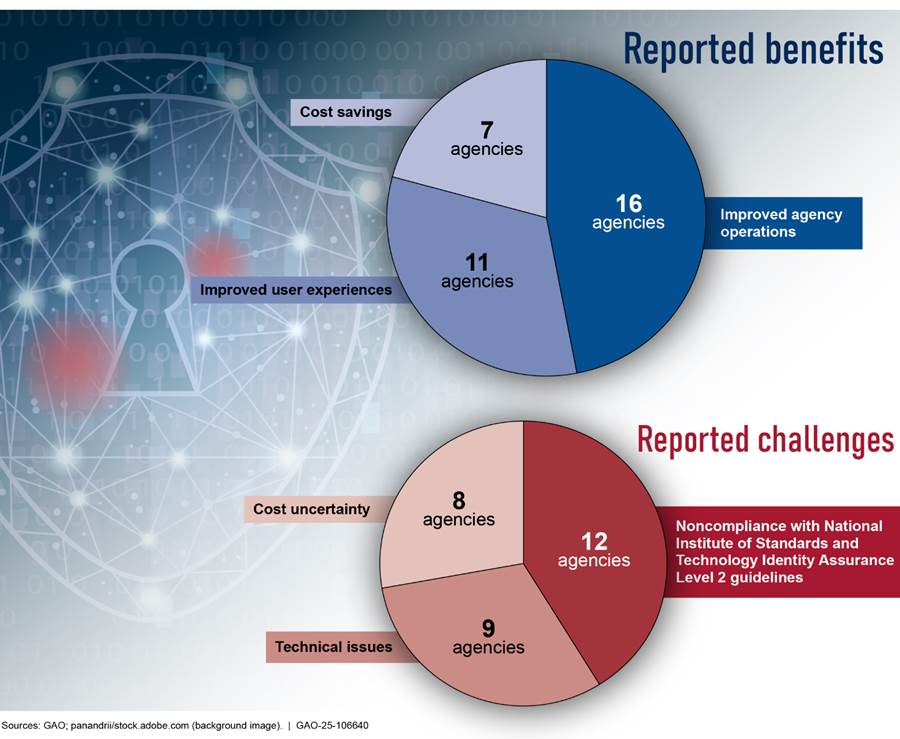

Twenty-one of the 24 Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agencies reported using Login.gov for identity proofing services. The agencies identified benefits from its use. Specifically, 16 reported improved operations, 11 reported enhanced users’ experiences, and seven reported reduced costs. The agencies also reported challenges, with 12 citing Login.gov’s lack of alignment with National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) digital identity guidelines, nine identifying technical issues, and eight noting cost uncertainty.

The General Services Administration (GSA) has not yet fully addressed alignment with NIST guidelines or the identified technical issues. For example, GSA has been taking steps to align Login.gov with NIST digital identity guidelines, including (1) completing a pilot on in-person identity proofing in March 2024 and (2) beginning a separate pilot on remote identity proofing. However, the remote identity proofing pilot is not yet available because GSA has not established an expected completion date for the pilot. Accordingly, non-compliance with NIST guidance continues.

The two pilot programs fully aligned with four of five leading practices.

|

Leading practice |

Description |

USPS in-person identity proofing pilot |

Remote identity proofing pilot |

|

Measurable objectives |

Establish clear, measurable objectives. |

● |

● |

|

Assessment methodology |

Articulate a data gathering and assessment methodology that details the type and source of the information necessary to evaluate the pilot, and methods for collecting that information, including the timing and frequency. |

● |

● |

|

Evaluation plan |

Develop a plan that defines how the information collected will be analyzed to evaluate the pilot’s implementation and performance. |

● |

● |

|

Lessons learned |

Identify and document lessons learned from the pilot to inform decisions on whether and how to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts. |

○ |

○ |

|

Stakeholder communication |

Appropriate two-way stakeholder communication and input should occur at all stages of the pilot. Relevant stakeholders should be identified and involved. |

● |

● |

Source: GAO-16-438 and GAO analysis of agency documentation | GAO‑25‑106640

Key: ● Fully Aligns. ◐ Partially Aligns. ○ Does Not Align.

For the pilot that is underway, a plan to identify lessons learned, if implemented effectively, could generate and apply important lessons to broader efforts.

Abbreviations

|

CFO |

Chief Financial Officers |

|

CSP |

credential service provider |

|

DOB |

date of birth |

|

FISMA |

Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

IAL |

identity assurance level |

|

IAL1 |

identity assurance level 1 |

|

IAL2 |

identity assurance level 2 |

|

ID |

identification |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PII |

personally identifiable information |

|

SSN |

Social Security number |

|

USPS |

United States Postal Service |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 16, 2024

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

The Honorable Pete Sessions

Chairman

The Honorable Kweisi Mfume

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Government Operations and the Federal Workforce

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

Federal agencies use personally identifiable information (PII) to verify the identity of individuals who access accounts on government websites.[1] The increase in cyberattacks on these agencies and other organizations has led to a greater risk of consumer PII being stolen and used to commit identity fraud. These attacks can also be used to fraudulently obtain federal benefits or sensitive information, which can harm citizens and damage the reputation of federal agencies.

To address this issue, the General Services Administration (GSA) launched Login.gov in 2017 to provide federal agencies with a single sign-on system to verify the identity of individuals seeking access to government websites. Login.gov uses a non-biometric three-step process—the identity-proofing process—that results in the verification of an individual’s identity. The identity-proofing process is to follow guidelines established by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).[2]

GSA reported that since its launch, Login.gov has been adopted by more than 40 federal and state agencies, and over 100 million users have signed up to use the system. In 2021, GSA, in accordance with a recommendation from the Technology Modernization Fund Board, awarded Login.gov about $187 million in technology modernization funds. The funds were to expand the usage of Login.gov by strengthening its security and anti-fraud protections, addressing identity verification barriers, and improving ease of agency adoption.

You requested that we review how Login.gov operates, including which federal agencies use Login.gov, and what their experiences using the system have been. Accordingly, this report examines (1) how Login.gov collects, shares, and protects PII while providing identity proofing services, (2) how many of the 24 Chief Financial Officers Act (CFO) agencies use Login.gov and what benefits and challenges have these agencies reported in their use, (3) the actions GSA is taking to align Login.gov with the requirements in NIST Digital Identity Guidelines,[3] and (4) the extent to which GSA’s actions are aligned with leading practices for pilot programs.

To address our first objective, we reviewed documentation that described Login.gov’s identity-proofing process and the types of information being collected and shared during the process. Specifically, we reviewed documentation such as privacy impact assessments, system security plans, and interviewed relevant agency officials. In addition, we reviewed privacy impact assessments for third party services used by Login.gov during its identity proofing process.

To address our second objective, we conducted semi-structured interviews with knowledgeable agency officials from the 24 CFO Act[4] agencies to identify whether they use Login.gov. We also obtained information about their reported benefits and challenges of using Login.gov for their public facing applications and websites. Subsequently, we discussed the reported challenges and any actions to address them with GSA.

Regarding our third objective, we reviewed Login.gov documentation such as program road maps, implementation plans, flowcharts, and publicly available statements about program plans to determine what efforts GSA had underway to align Login.gov with NIST Digital Identity Guidelines.[5] We also interviewed knowledgeable GSA officials to supplement that information.

Regarding our fourth objective, we evaluated the extent to which GSA’s efforts followed GAO’s leading practices for pilot programs.[6] We assessed GSA responses and documentation on each leading practice, and rated GSA’s efforts as “fully aligns,” “partially aligns,” and “does not align.” If the leading practice was “fully aligns,” we concluded that GSA’s pilot plans incorporated the leading practice. In contrast, if it was “partially aligns” or “does not align,” we concluded that GSA’s plans did not fully incorporate the leading practice. For more details on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2022 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal agencies are responsible for ensuring that individuals are properly vetted before they access government services, benefits, and other resources. A key part of this process is verifying that the person who is attempting to interact for the first time with a federal agency is the individual he or she claims to be. This process is known as identity proofing.

Identity proofing may occur in-person or through a remote online process. In the case of in-person identity proofing, a trained professional verifies an individual’s identity by making a direct physical comparison of the individual’s physical features and other evidence (such as a driver’s license) with official records to verify the individual’s identity. Verification of these credentials can be performed by checking electronic records in tandem with physical inspection.

Remote identity proofing is the process of conducting identity proofing entirely through an online exchange of information. When remote identity proofing is used, the individual provides the information electronically or completes additional electronically verifiable actions to confirm their identity.

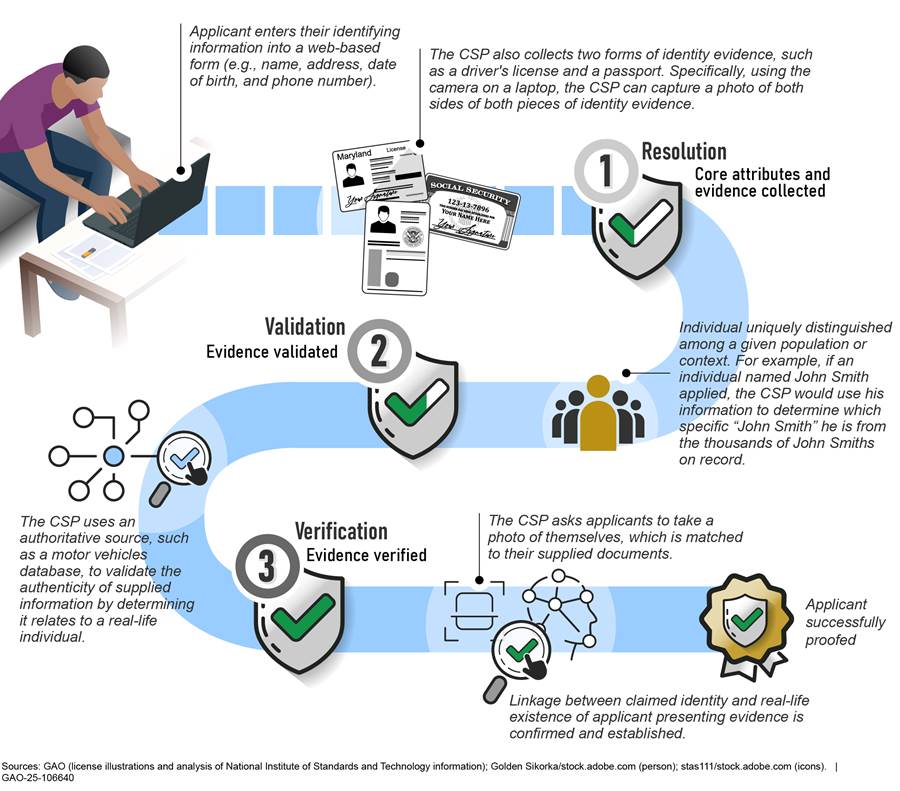

Overview of the Remote Identity-Proofing Process

Because many federal benefits and services are offered broadly to large numbers of geographically dispersed individuals, agencies often rely on remote identity proofing to verify the identities of individuals. Remote identity proofing is the process through which a credential service provider (CSP) collects and verifies information about a person for the purpose of issuing credentials to that person, as illustrated in Figure 1.[7]

Remote identity proofing involves three major steps: (1) resolution, (2) validation, and (3) verification.

· Resolution: The identity resolution process begins by having the applicant provide identifying information, typically through a web-based application form. Examples of information that an agency may collect for identity resolution includes name, address, date of birth (DOB), and Social Security number (SSN). The CSP may also collect information from the applicant’s driver’s license or passport by having the applicant use a camera to capture screenshots of both sides of the document.

The CSP then electronically compares the applicant’s identifying information with electronic records maintained by an authoritative source, such as a state’s Department of Motor Vehicles, to determine (or “resolve”) which identity is being claimed. For example, if an individual named John Smith applied, the CSP would use his identifying information to determine which specific “John Smith” he is from among the thousands of John Smiths that may be documented in the records of the authoritative source being used for this process.

· Validation: During this step, the agency electronically submits the information that the applicant provided to the CSP for validation. The validation process confirms that the evidence submitted is genuine and that the information is valid, current, and represents a real identity. Specifically, the CSP checks the image on the license and/or passport to determine that there are no alterations and that the identification numbers follow standard formats, among other things.

· Verification: In this step, actions are taken to verify whether the applicant is really who they claim to be. For example, in the case of John Smith, it is not enough simply to determine which “John Smith” is being claimed, because the applicant may not really be “John Smith” at all. During the verification, the CSP asks the applicant to take a photo of themself to match to the license and/or passport picture provided during the resolution step. Once the CSP matches the picture(s) on the license and/or passport to the applicant’s picture and determines that the pictures match, an enrollment code is sent to the validated phone number of the applicant. The user provides the enrollment code to the CSP, and a match is confirmed, which verifies users are in possession and control of the validated phone number.

After the user goes through these steps, they have been successfully proofed and the user is able to log into federal agencies’ websites and applications to access their information or apply for federal services.

Federal Legislation and Guidance on Information Security and Identity Proofing

The Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA) provides a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of security controls over information resources that support federal operations and assets, as well as the effective oversight of information security risks.[8] FISMA assigns responsibility to the head of each agency to provide information security protections commensurate with the risk and magnitude of the harm resulting from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction of information systems used or operated by an agency or on behalf of an agency.

Further, FISMA assigns responsibility to NIST for developing comprehensive information security standards and guidelines for federal agencies. These include standards for categorizing information and information systems according to ranges of risk levels and guidelines for establishing minimum security requirements for federal information systems.[9] FISMA also identifies the development, implementation, and oversight of NIST’s federal information standards and guidelines that federal agencies are expected to follow.

To fulfill its FISMA responsibilities, NIST has issued technical guidance on many different aspects of information security, including identity proofing. Specifically, NIST issued guidance in 2017 on identity proofing that outlines technical requirements for resolving, validating, and verifying an identity based on evidence obtained from a remote applicant.[10] Further, this guidance defined identity assurance levels (IAL), which describes the degree of confidence that a user’s claimed identity is their real identity. NIST recommends agencies choose an assurance level based on their risk profile and the potential harm from an attacker falsely claiming an identity. This selection can vary based on the transaction type for which the agency needs identity proofing. See Table 1 for a description of each level.

|

IAL level |

Description |

Evidence collected |

|

IAL1 |

There is no requirement to link users to a specific real-life identity. Any information provided by users should be treated as self-asserted and is neither validated nor verified. |

No identity evidence is collected. |

|

IAL2 |

The evidence provided supports the real-world existence of users’ identities and verifies that users are appropriately associated with this real-world identity. This level introduces the need for either remote or physically present identity proofing. |

Evidence may include a passport or driver’s license, and remote biometric evidence, such as a “selfie.”a |

|

IAL3 |

Physical presence is required for identity proofing. Identifying attributes must be verified by an authorized and trained CSP representative. |

Evidence may include a passport and driver’s license, as well as a physical or remote interaction supervised by a live operator. |

Source: GAO analysis of National Institute of Standards and Technology information. │ GAO‑25‑106640

aA “selfie” is a photograph one takes of oneself.

Subsequently, in May 2019, Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued a memorandum that required federal agencies to implement NIST’s identity guidelines and any successive versions, which included the need for IAL2 capabilities for identity proofing.[11] Specifically, the guidelines state that for verification at IAL2, the goal is to confirm and establish a linkage between the claimed identity and the real-life existence of the subject presenting the evidence, requiring either a physical comparison to a photograph or a biometric comparison. In 2020, NIST published informational implementation resources that focused on digital authentication of users interacting with government systems and clarified the importance of liveness detection for identity proofing verification of evidence at IAL2.[12]

GSA Established Login.gov to Authenticate Users, but It Does Not Yet Provide All Intended Capabilities

When Login.gov was launched in 2017 by GSA’s Technology Transformation Services division,[13] it was created as a multi-factor authentication login platform that would generate a single account for users interacting with the federal government online.[14] The system offered IAL1 services to its users, meaning there was nothing linking users to a specific real-life identity. Later, in 2019, GSA’s Chief Information Officer stated in the Login.gov agency authorization to operate that the system “can support user validation at identity assurance level 1 or 2.”

However, in March 2023, GSA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) reported that Login.gov did not meet the requirements to verify a person at the IAL2 level. According to the report, this was because the system never included a physical or biometric comparison between the user and the evidence that was provided during the proofing process to link them to a specific real-life identity.[15]

In addition, the office found that Login.gov continued charging customer agencies for IAL2 services after Technology Transformation Service and Login.gov officials were informed in 2020 that IAL2 services were not available. According to GSA’s Technology Transformation Services division, Login.gov billed IAL2 customers more than $10 million for services through May 2022. Further, even after notifying customer agencies in February 2022 that their services were not compliant with NIST IAL2 standards, Login.gov continued to bill agency customers for those services.

As a result of the GSA’s OIG report, GSA officials updated their websites and documentation to reflect that Login.gov only offered services at the IAL1 level. Officials also communicated to partner agencies that they were working on updating the system to meet the applicable NIST IAL2 requirements. As of July 2024, Login.gov is not yet certified by an independent third-party auditor as IAL2 compliant.[16]

Login.gov’s Identity Proofing Process Collects, Shares, and Protects Personally Identifiable Information

Login.gov is a system designed for individuals to access federal agencies’ websites with a single username and password. To do this, the system collects a variety of personally identifiable information (PII) from users who seek access to government applications and websites. Login.gov then shares the data with multiple third-party vendors to determine the degree of confidence that users’ claimed identity is their real identity. Throughout the identity-proofing process, Login.gov uses a variety of methods to protect the collected and shared PII.

Login.gov Collects Users’ Personally Identifiable Information and Shares It with Third Party Services

|

Login.gov asks the user to provide the following personally identifiable information: · Full name · Date of birth · Home address · Social Security number · Type and number of users’ state-issued identification card; and · Images of the front and back of the state-issued identification card. Additionally, with the user’s consent, Login.gov may use the contact phone number provided to confirm the home address. Source: GAO summary of General Services Administration information. | GAO 25 106640 |

Login.gov was designed to collect information from users who create an account to access federal websites. Specifically, Login.gov requires that users enter their email address, create a password, and select a method of multi-factor authentication,[17] such as using a text message, among other options. Once the information is provided, users consent to the system’s privacy practices. Next, Login.gov sends users a one-time code via text or email. After users enter the code, their account is created. After this process, users can choose to either continue with the online identity-proofing processes or opt to go to a U.S. Post Office to finish the process.

Login.gov’s Online Identity-Proofing Process

After users create an account, Login.gov is intended to prompt them to upload an image of the front and back of their unexpired state-issued identification (ID) card. If users are able to successfully upload their ID, Login.gov reportedly encrypts the PII and the data is shared with third-party services, for identity proofing. Specifically, users’ PII goes through a series of checks with the following vendors:

· LexisNexis’ Document Authentication:[18] The PII is to be sent to LexisNexis to check the authenticity of the ID by reviewing security features and checking for evidence of tampering to determine if there were any alterations to the image of the ID. Specifically, if the submitted document conforms to the template for that document, passes checks showing no signs of tampering, and the document data in the visible fields matches the data extracted from the barcode, LexisNexis is to send a “passed” response to Login.gov. The response is to indicate that the document was authenticated, and no problems were encountered that were related to the authenticity of the document.[19]

· LexisNexis’ Identity Validation: Once the users’ state-issued ID is deemed authentic, Login.gov is to send users’ license data to LexisNexis to check that the data belongs to a single individual. More specifically, LexisNexis is to respond with whether the information passed or failed the Login.gov configured checks and provides the reason for passing or failing each check. For example, if users’ DOB passed the check, the response should say “DOBFullVerified.” If users’ SSN failed the check, a potential response code could say “SSNNotMatchFullName” indicating that the SSN does not match the first and last name of the user.

· Driver’s License Data Verification Service:[20] Once the users’ state-issued ID is deemed authentic and the PII is verified to belong to one individual, Login.gov is to send users’ license data to the driver’s license data verification service. The service intends to verify that the PII from the user’s license matches the data from a state ID in the user’s state. As a result, Login.gov is to receive a response as to whether the PII matches data from the appropriate jurisdiction.

· LexisNexis’ Phone Validation: Login.gov also is to send users’ PII including name, SSN, DOB, and phone number to a LexisNexis service to verify that the phone number provided is associated with the user and whether the user is the phone’s account owner (i.e., the phone is billed to the user). Once the phone number is verified, Login.gov is to send users a one-time code, which is intended to prove that users are in possession of the phone.

After these checks, Login.gov is to prompt users to re-enter the password that was created when the account was established. Once that step is successful, the identity-proofing process should be complete.

In-Person Identity Proofing at a U.S. Post Office

Users may opt to have identity proofing done in person or may need to do so if they are unable to upload their ID online.

· In-person proofing as an initial verification option: Users can select the “verify in person” option, allowing users to conduct the identity proofing process in person rather than online. Next, users search for and select a U.S. Post Office to visit. Then, users are to enter information from their state-issued ID, such as name, address, DOB, and unexpired ID number, in addition to their SSN and phone number. After Login.gov performs the verification checks described above, the system is to then generate a barcode that users can print or download to present along with their state-issued ID to the post office.[21]

· In-person proofing after failing to upload ID: As described above, as part of its online proofing process, Login.gov is to prompt users to upload an image of the front and back of their unexpired state-issued ID. If users’ ID image fails to upload, users are to have the option to verify their identification at their local participating U.S. Post Office. To do this, users will need to enter information from their ID, including their name; DOB; unexpired state-issued ID number; and address, in addition to their SSN and phone number. After Login.gov performs the verification checks described above, the system is to then generate a barcode that users can print or download to present along with their state-issued ID to the post office.

Once the user presents the barcode at the U.S. Post Office for verification, the clerk is to compare the full name and address on the ID and confirm that it matches the information submitted during the Login.gov process. The clerk also is to conduct a comparison of the photo on the ID to the person at the post office.[22] If the user passes the in-person proofing, they are to receive an email informing them that their identity has been successfully verified through Login.gov.

After successful verification at the post office, users are to receive an email from Login.gov to sign back into the system. Login.gov is to then confirm that the user has had their identity verified and obtains consent to share their PII with the relevant federal agency. At this point, the identity proofing is intended to be complete.

Login.gov Implemented Security Controls to Protect PII Collected in Its Identity-Proofing Process

Login.gov has security controls in place to protect users’ PII during its identity-proofing process, including limiting access to the information, as well as behavior monitoring and fraud protection. For example, throughout its identity-proofing process, Login.gov uses LexisNexis fraud detection as a fraud mitigation measure to distinguish a legitimate user from a cybercriminal.

Limiting Access to Login.gov Users’ PII

One method that Login.gov uses to limit access to users’ PII is by employing encryption. Specifically, Login.gov uses encryption when the data is in transit to its third-party vendors and when the PII is stored in the system. Users’ PII is encrypted using a unique value generated from the user’s password, ensuring that only the user can decrypt and view their information.

In addition to using encryption, Login.gov also limits the amount of PII available to its employees and third-party vendors. For instance, Login.gov and LexisNexis employees[23] have access to information about users’ transactions that were submitted for verification, but the PII available in those transactions is limited. Specifically, the employees have access to information such as transaction IDs, what checks failed, reason codes, and risk scores. These checks, reason codes, and scores do not contain any PII and only provide indications into the nature of the failure or the overall risk score. An example of a reason code would be “The SSN does NOT match the first and last name,” but no other information specific to an individual would be available. With respect to third party services, LexisNexis® Risk Solutions and the Driver’s License Data Verification Service do not store, keep, or use the user’s input data.

Further, Login.gov restricts employees or other individuals involved in the identity proofing process access to users’ PII to the minimum level that is needed to do their job. This helps to ensure that the risk of unauthorized disclosure or abuse is decreased. For example, for U.S. Post Office in-person proofing, clerks can only access the user’s name and address to verify the user’s identity. These clerks are not privy to any other PII that the user entered into Login.gov.

Monitoring and Preventing Fraud

Login.gov uses fraud detection and mitigation to monitor and prevent fraud. For example, fraud capabilities are deployed to limit identity impersonation and synthetic types of fraud. These services monitor Login.gov users via behavioral biometrics[24] during the identity verification process to understand their behavior and to determine if a fraudulent participant is involved during this process.

· These capabilities deliver multiple indicators that highlight potential fraud, social engineering, and remote access red flags. Additionally, Login.gov profiles devices accessing its website, including desktops, laptops, smartphones, or tablets to detect suspicious devices, spoofed IP addresses, and the presence of malware or other anomalies that might indicate a high-risk device or user.

· Fraud scoring is used to detect fraudulent applications including fake identities created by fraudulent actors and other types of fraud. The capability gathers and analyzes hundreds of unique identity characteristics, including users’ name, address, DOB, and SSN to identify inconsistencies and suspicious associations in the data.

Most CFO Act Agencies Reported Using Login.gov and Identified Benefits and Challenges

Most of the 24 CFO Act agencies reported using Login.gov for identity proofing services and identified several benefits associated with its use, such as improving agency operations, improving their users’ experiences, and cost savings. However, they also reported challenges, such as Login.gov’s noncompliance with NIST standards, technical issues, and uncertainty related to costs.

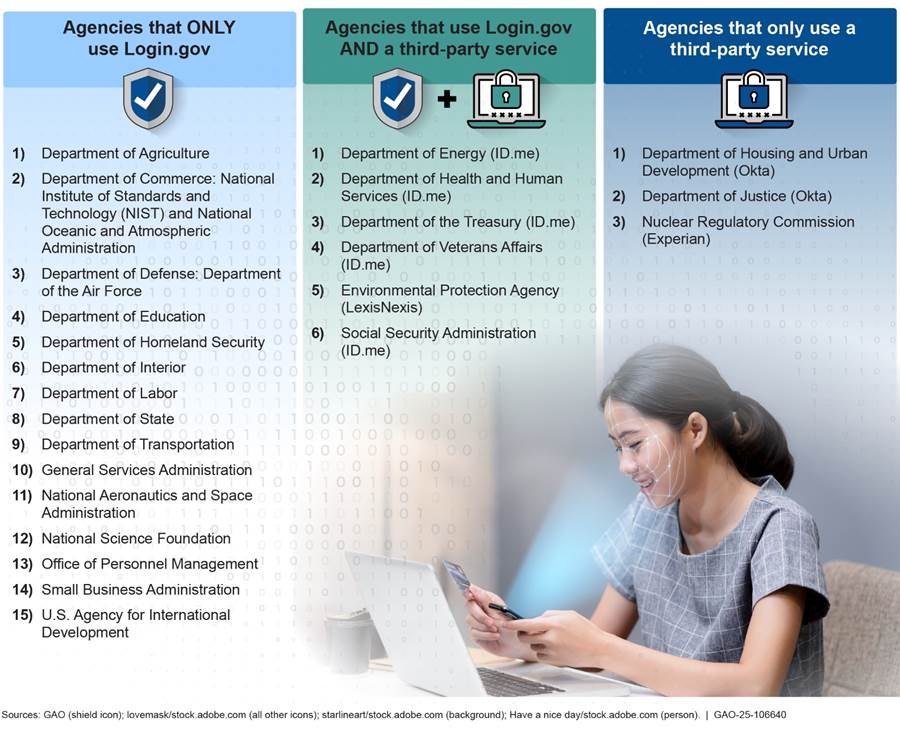

Twenty-one of the 24 CFO Act Agencies Use Login.gov

Of the 24 CFO Act agencies, 15 agencies reported using Login.gov for public facing applications, six reported using Login.gov in conjunction with an additional third-party service, and three reported not using Login.gov at all, opting instead to use a third-party service (see figure 2).

Notes: The names of any third-party services used are provided in parentheses after the agency name. The third-party provider may offer authentication only or identity verification services.

According to National Aeronautics and Space Administration officials, Login.gov is used for one public facing application.

According to Department of Defense officials, U.S. Air Force is the only component that uses Login.gov at the Department of Defense. Also, according to Department of Commerce officials, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Standards and Technology are the only components at the Department of Commerce that uses Login.gov.

Fifteen agencies reported using Login.gov with their public facing applications. For example, the Department of Transportation’s Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration uses Login.gov to authenticate medical examiners before they can report the medical status of commercial motor vehicle operators to the agency. Also, the Department of Agriculture’s Guaranteed Underwriting System uses Login.gov to verify and authenticate lenders before they can submit and process loan application requests for the Single-Family Housing Guaranteed Loan Program.[25]

Six agencies reported using both Login.gov and a third-party commercial identity proofing service−ID.me[26] or LexisNexis.[27] For example, Treasury reported using Login.gov for transactions at IAL1 across approximately 10 public-facing applications, such as the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System.[28] In addition to Login.gov, Treasury uses ID.me for IAL2 transactions across approximately 15 public-facing applications, such as the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Claims System.[29] Further, the Environmental Protection Agency reported using Login.gov for IAL1 transactions including those in its Integrated Compliance Information System.[30] The agency also uses LexisNexis for applications that needed IAL2 identity verification such as their Central Data Exchange system.[31]

Three agencies reported not using Login.gov for public facing applications and using a third-party commercial solution instead. For example, Department of Justice reported using Okta[32] because the department required services at the higher assurance level. In addition, the Department of Housing and Urban Development reported using Okta at the department level for its Federal Housing Administration Connection system.[33] The department explained that they believed that Okta improved the customer experience by creating self-service registration capabilities for users, organizations, and application administrators. Further, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission reported using Experian[34] because the agency performs identity proofing only about 200 times a year and this option was deemed cost effective for the agency.

Agencies Reported Benefits and Challenges Using Login.gov

According to officials at 21 of the 24 CFO Act agencies,[35] the use of Login.gov creates benefits for some agencies, such as improved operations and user experiences, but can also present technical and cost challenges. Figure 3 shows the benefits and challenges most frequently identified, which are discussed in more detail below.

Agency Reported Benefits

Agencies most frequently identified three benefits associated with their use of Login.gov.

· Improved agency operations. Sixteen of 21 agencies reported that -deploying Login.gov improved their operations by decreasing the workload for agency employees, addressing existing security issues, and employing new technology. For example, the Department of Interior reported that employees’ workloads decreased because they did not have to manage and maintain individual user accounts or keep up to date on security requirements, which the department needed to do when using an in-house solution. In addition, the Department of Veterans Affairs reported that Login.gov addressed security issues in the login process for the department’s existing applications. Specifically, the department stated that it was previously using a login system that was vulnerable to fraudsters that were accessing veterans’ accounts. Further, the Office of Personnel Management reported that using Login.gov had improved its authentication and security by transitioning from the use of username and password to a system that uses multi-factor authentication.

· Improved user experiences. Eleven agencies reported that deploying Login.gov improved their users’ experiences by creating a standard interface for use across the government. Specifically, users were able to use their Login.gov sign on credentials to access applications across different federal agencies. In addition, the Department of Homeland Security reported that Login.gov’s 24/7 help desk was a benefit to users needing assistance.

· Cost savings. Seven agencies reported that deploying Login.gov provided cost saving benefits. For example, the Department of State reported that, when it was managing a bureau’s own identity proofing system, the bureau had to manage system costs and ensure that its system was compliant with system requirements. Also, the bureau provided technical support to users who had account issues, all of which became expensive. In addition, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that having Login.gov provided cost savings due to the department’s reduced time spent keeping up with changes to NIST standards and other security requirements.

Agency Reported Challenges

Agencies reported three challenges associated with Login.gov.

· Noncompliance with NIST IAL2 guidelines. Twelve of 21 agencies reported challenges related to Login.gov’s noncompliance with NIST IAL2 guidelines. For example, the Department of Treasury reported that using Login.gov for applications needing IAL2 services would expose the agency to security risks, such as cyber criminals and exploiting systematic weaknesses. In addition, the Small Business Administration reported that Login.gov’s noncompliance is a challenge. Specifically, officials stated that the finding from GSA’s Office of Inspector General report regarding the system’s noncompliance caused the agency to pause their plans to use the system.[36] The agency had to perform additional data calls and reviews to learn more about Login.gov’s costs and security issues.

Login.gov officials reported that they are taking steps to address this challenge. GSA rolled out additional in-person identity proofing functionality in April 2024 and is currently developing a pilot to test remote identity proofing functionality. The agency is also seeking third-party certification to ensure that adding these functionalities will allow the system to meet NIST IAL2 digital identity standards.

However, as of July 2024, Login.gov is not yet IAL2 compliant. As discussed in the next section of this report, the pilot started in May 2024 but does not have a scheduled completion date.[37]

· Technical Issues. Nine agencies reported challenges involving technical issues with Login.gov, such as not having visibility into authentications, high failure rates, and lack of fraud controls, among others. For example, the Department of Labor reported the lack of real time visibility into application authentications as being a major challenge. Labor noted that this real-time visibility is essential for identifying and addressing potential security threats, performance issues, or compliance issues in a timely manner. In addition, the Small Business Administration reported that their public users experienced difficulties accessing and setting up Login.gov accounts. Specifically, officials noted that users had a 30-40 percent failure rate during account creation and reported that the multi-factor authentication options could be confusing to users. Further, the U.S. Agency for International Development reported that Login.gov’s SMS authentication[38] option that uses text messaging or phone calls is not available in some countries, which impacts their employees’ ability to access the Development Information Solution.[39]

Login.gov officials reported that they are communicating with agencies and taking steps to address the reported technical challenges. However, the affected agencies reported that GSA has not yet provided solutions or timelines to address these challenges. For example, during Login.gov’s Partner Advisory Group meetings, Labor requested advanced monitoring tools and a customer dashboard to address its challenge related to real-time visibility into authentications. Labor officials stated GSA responded that they would consider implementing tools and a dashboard in the future but did not provide any information on these proposed changes or timelines for implementing them. In addition, the Small Business Administration reported that it is working with GSA to address the difficulties their users are experiencing when trying to create an account. However, GSA has not yet fully addressed the challenge or developed timelines for when this will be addressed.

Further, U.S. Agency for International Development reported that GSA has added more countries for international phone support such as using a multi-factor authentication method to receive texts. However, U.S. Agency for International Development reported that phone numbers from some countries remain unsupported by Login.gov and GSA has not provided any timeframes for when this will be addressed. According to GSA officials, addressing these challenges will be considered for future iterations to Login.gov. However, without GSA-proposed actions and time frames for addressing the challenges, agencies will continue to experience technical issues with the system.

· Cost Uncertainty. Eight agencies reported challenges related to Login.gov’s pricing. For example, the Department of Justice reported that their agency was not able to get a multi-year pricing plan from Login.gov, which they were able to get from other identity proofing vendors. Also, the Office of Personnel Management reported that there was cost uncertainty related to Login.gov’s annual renewal process and the potential for prices to rise between years. The office also further explained that the pricing model for enterprise users can result in steep cost increases when their user volume increases.

Login.gov officials reported that they are taking steps to address challenges related to cost uncertainty. GSA officials stated that Login.gov has developed and communicated with agencies a new pricing model that is intended to help agencies of all sizes more affordably use and expand their use of Login.gov. The pricing model went into effect on July 1, 2024. Given this action, agencies should now have less uncertainty with cost-related information and should be able to make informed financial decisions related to their use of Login.gov.[40]

GSA Plans to Align Login.gov with NIST Guidelines but Compliance Not Yet Achieved

GSA is taking steps to align with NIST guidelines and offer IAL2 services to its partner agencies. Specifically, the agency conducted a pilot that resulted in Login.gov offering users the option to conduct in-person proofing at post office facilities at the start of the identity-proofing process. In addition, GSA reported that an additional pilot is intended to provide remote identity proofing. Further, the agency has applied to have these identity-proofing capabilities assessed for IAL2 compliance by a third-party auditor.[41]

According to GSA, the remote identity proofing pilot started in May 2024 with one agency.[42] However, GSA has not established an expected completion date for the pilot. Further, the timing of the third-party auditor’s assessment is uncertain since IAL2 compliance has not yet been achieved.[43]

|

According to NIST, the identify-proofing process involves three steps: · Resolution: This step starts the identity resolution process by having users provide identifying information, such driver license information, typically through a web-based application form. · Validation: The authenticity and accuracy of users’ personally identifiable information is compared to an authoritative source such as a motor vehicle database. · Verification: Users take a “selfie” of themselves to match the license picture provided in the resolution step. Source: GAO summary of National Institute of Standards and Technology information. | GAO 25 106640 |

· In-person identity proofing at U.S. Post Offices. Initially, Login.gov only offered in-person proofing at post offices when users fail to upload their ID image during the remote verification process. To offer this option to all users, GSA created a pilot to evaluate the feasibility of offering in-person proofing to users as an initial verification option. The pilot started in January 2024 and concluded in March 2024. The goal of the pilot was for GSA to identify users that could be prevented from abandoning the Login.gov online process when in-person proofing at the post office was offered at the start of the process. The pilot ran until 1,000 users started the Login.gov process and continued through to in-person proofing at the post office. Based on Login.gov’s feedback from agency partners such as Veterans Affairs and the Department of Labor, some users preferred in-person proofing at the post office up front.[44] During this pilot, more than half (57 percent) of users who successfully proofed did so by opting-in during the start of the identity proofing process. This opt-in option was made permanently available to the public in April 2024.

· Remote identity proofing. As previously noted, NIST’s identity-proofing process has a third step called verification. This step involves users providing a “selfie” of themselves to match to the photo from the state-issued ID that was provided during the resolution step. Currently, Login.gov’s identity-proofing process does not include this step. To address this, GSA reported that it started a pilot in May 2024 that intends to provide a remote identity proofing option. However, as of August 2024, GSA has not provided an estimated timeframe for when this option will be available to the public.[45]

In addition to conducting these pilots, GSA is using an independent third-party auditor to assess whether the new identity proofing capabilities described above will meet the relevant IAL2 guidance. According to GSA officials knowledgeable about the process, the auditor will conduct conformance assessments and testing. Specifically, Login.gov’s policies, processes, and functions will be audited to ensure they meet NIST’s IAL2 guidance. If the auditor determines that the system meets the guidance, a certification will be issued to show that Login.gov is IAL2 compliant. GSA reported that its application was submitted in April 2024, and they are awaiting the results from the third-party auditor.[46]

According to GSA documentation, Login.gov intends to offer the remote “selfie” identity proofing functionality; however, this option is not yet available to users. Further, a completion date for the pilot has not yet been established to determine if the functionality will work as intended. Until GSA establishes a completion date for the pilot and confirms the functionality works as intended, the agency will not be able to ensure that Login.gov fully aligns with NIST’s IAL2 guidelines.

GSA Pilot Programs Met Most Leading Practices, but Did Not Identify Lessons Learned

A well-designed and documented pilot program can help ensure agency assessments produce information needed to make effective program and policy decisions. This process enhances the quality, credibility, and usefulness of evaluations in addition to helping to ensure that time and resources are used effectively. GAO’s five leading pilot program practices are: (1) establish measurable objectives, (2) develop an assessment methodology, (3) identify lessons learned, (4) develop an evaluation plan, and (5) ensure two-way stakeholder communication. In addition, prior GAO reports have shown that designing pilot programs in alignment with leading practices increases an agency’s ability to assess the pilot’s success and evaluate outcomes and impacts of the pilot.[47]

As previously discussed, GSA reported that it now offers the option to conduct in-person proofing at U.S. post offices at the start of the identity-proofing process. Additionally, GSA has started a pilot that is intended to provide users with a remote identity proofing option.[48] While GSA’s two identity proofing pilots met most of the leading practices, we found that for the in-person proofing pilot, GSA did not identify and document lessons learned. Since this pilot has been complete for five months, it is too late for action to be taken for this pilot. However, for the remote identity proofing pilot, GSA did not have plans on how it was going to document lessons learned. See Table 2 for a detailed description of each leading practice and our assessment of the design of GSA’s pilot programs.

|

Leading practice |

Description |

USPS in-person identity proofing pilot |

Remote identity proofing pilot |

|

Measurable objectives |

Establish clear, measurable objectives. |

Fully Aligned |

Fully Aligns |

|

Assessment methodology |

Articulate a data gathering and assessment methodology that details the type and source of the information necessary to evaluate the pilot, and methods for collecting that information, including the timing and frequency. |

Fully Aligned |

Fully Aligns |

|

Evaluation plan |

Develop a plan that defines how the information collected will be analyzed to evaluate the pilot’s implementation and performance. |

Fully Aligned |

Fully Aligns |

|

Lessons learned |

Identify and document lessons learned from the pilot to inform decisions on whether and how to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts. |

Did Not Align |

Does Not Align |

|

Stakeholder communication |

Appropriate two-way stakeholder communication and input should occur at all stages of the pilot. Relevant stakeholders should be identified and involved. |

Fully Aligned |

Fully Aligns |

Source: GAO‑16‑438 and GAO analysis of agency documentation. | GAO‑25‑106640

Note: For our analysis, “fully aligns” means we found evidence that fully or significantly satisfied the leading practice; “partially aligns” means we found evidence that satisfied some portion of the leading practice; and “does not align” means we found little or no evidence that satisfied the leading practice.

Measurable Objectives

Clear and measurable objectives can help ensure that appropriate evaluation data are collected from the outset of pilot implementation so that data will subsequently be available to measure performance against the objectives.

· For the USPS in-person identity proofing pilot, we found that GSA’s pilot program documentation fully aligned with this leading practice. For example, documentation outlined the objectives of the pilot, which included measuring the success rates of users who used the USPS in-person identity proofing at the start of the Login.gov process, among others. Specifically, the pilot intended to measure usage rates between USPS in-person proofing that occurred at the start of the Login.gov process and USPS in-person proofing that happens after users fail online. In addition, the pilot intended to identify the impact of help desk usage.

· For the remote identity proofing pilot, we found that its documentation fully aligns with this leading practice. GSA documentation stated that the objective of the pilot is intended to measure whether the remote biometric functionality can work. To do this, GSA plans to use a phased approach by evaluating this functionality using real-world use cases and making iterative improvements to Login.gov, when necessary. In addition, GSA intends to measure key metrics against the objective of the pilot, such as the percentage of “selfie” images that appears to match the image from the ID’s picture and successfully completes the identity verification process.

Assessment Methodology

Key features of an assessment methodology include a strategy for comparing the pilot implementation and results with other efforts, a clear plan that details the type and source of the data necessary to evaluate the pilot, and methods for data collection including the timing and frequency.

· For the USPS in-person identity proofing pilot, we found that pilot documentation fully aligned with this leading practice. Specifically, GSA described the types of data necessary to evaluate the pilot, such as tracking the total number of identity proofs that were completed for remote and in-person identity proofing, before and during the pilot. For example, GSA reported that 48,505 users were identity proofed during the pilot. Of these users, 1,138 were proofed in-person, with 639 of these users opting into identity proofing at the start of the process. In addition, GSA documentation showed that they tracked end-to-end metrics for the in-person identity-proofing process and documented them daily. For example, on May 22, 2024,124 users went through the process online to generate a barcode to identity proof in person at U.S. Post Office. Also, on that day, 114 users went to the post office and were successfully able to be identity proofed.

· For the remote identity proofing pilot, we found that pilot documentation fully aligns with this leading practice. For example, GSA documentation stated the agency intended on collecting certain data points daily during each phase to evaluate the pilot. This data includes the percent of users that initiate biometric proofing, the percent of users that successfully have their selfie matched to their ID image, and the percent of users who complete the identity verification process after a successful match.

Evaluation Plan

A detailed evaluation plan identifies who will do the analysis as well as when and how data will be analyzed to measure the pilot program’s implementation and performance. For example, a data analysis plan could include surveying pilot program participants, or agency partners, to compare their experiences and observations with program goals.

· For the USPS in-person identity proofing pilot, we found that pilot program documentation fully aligned with this leading practice. For example, GSA documentation described who was responsible for analysis and reporting tasks to measure the pilot’s implementation and performance. Specifically, GSA listed the tasks related to the pilot and the person responsible for each task. In addition, the department described the metrics that were measured, such as the rate in which users opted to use in-person proofing at the start of the process versus after the user failed the online option.

· For the remote identity proofing pilot, we found that the pilot program documentation fully aligns with this leading practice. Specifically, GSA provided documentation that describes the initiatives, responsible parties and how data will be analyzed to measure the pilot program’s implementation and performance. For example, one task is to test a working proof of concept for “selfie” verification to understand how Login.gov’s users interact with the “selfie” feature and identify any challenges the users might face. The documentation also identifies potential methodologies for this task, completion timeline, and describes next steps for pilot implementation.

Lessons Learned

The use of lessons learned is a principal component of an organizational culture committed to continuous improvement. Specifically, lessons learned serve to communicate acquired knowledge more effectively and to ensure that beneficial information is factored into planning, work processes, and other activities. In addition, the main purpose of a pilot is generally to inform a decision on whether and how to implement a new approach in a broader context. Therefore, it is critically important to consider how well the lessons learned from the pilot can be applied in other, broader settings.

· For the USPS in-person identity proofing pilot, we found that pilot program documentation did not align with this leading practice because GSA has not identified and documented lessons learned from the pilot program. While GSA recorded the results of the pilot, the agency did not identify lessons learned or demonstrate that it documented lessons learned from this pilot. Specifically, documentation stated that Login.gov experienced a 30 percent increase in proofing volumes during this pilot. In addition, Login.gov experienced a 3.01 percent conversion rate to in-person proofing, which reflected the users who preferred to start the Login.gov process with in-person proofing. However, GSA did not identify lessons learned or document how the lessons learned from this pilot will inform broader efforts such as the upcoming remote identity proofing pilot.

According to officials knowledgeable about Login.gov, the pilot only tracked and addressed technical issues, which they considered lessons learned. However, identifying lessons learned goes beyond tracking just technical issues. Specifically, lessons learned serve to communicate acquired knowledge more effectively and to ensure that beneficial information is factored into project planning, work processes, and other activities. In addition, the main purpose of a pilot is generally to inform a decision on whether and how to implement a new approach in a broader context. By not identifying lessons learned while conducting this pilot, and it has been five months since the completion, GSA missed out on important information that could have been applied to other efforts, such as the remote identity proofing pilot.

· For the remote identity proofing pilot, we found that pilot documentation does not align with this leading practice. GSA reported that because they are using a phased approach for this pilot, they will evaluate this functionality using real world use cases to help identify lessons learned which would result in improvements. However, GSA documentation did not demonstrate how lessons learned will be identified and documented from this pilot. As previously discussed, it is critically important to develop a plan for identifying lessons learned to inform future phases of this pilot or how they can be applied in other, broader settings. Until GSA develops a plan for how it will identity and document lessons learned from this pilot, Login.gov faces an increased risk of not capturing important information gained in the phases of the pilot to apply to future phases or the broader Login.gov efforts.

Stakeholder Communication

Appropriate two-way stakeholder communication and input should occur at all stages of the pilot, including design, implementation, data gathering, and assessment.

· For the USPS in-person identity proofing pilot, we found that the pilot program documentation fully aligned with this leading practice. GSA established and maintained two-way communication with stakeholders through established executive steering committee meetings and partner advisory group meetings that discussed the pilot with agency partners. For example, the committee discussed GSA’s USPS agreement that would start the pilot, expansion of the USPS locations that would be included in the pilot, and how GSA was going to fund the pilot. In addition, the committee reported pilot updates to Login.gov stakeholders at different points during the pilot, such as when developing application materials to submit to an independent third-party evaluator. Further, one of the agency partners that participated in the USPS in-person identity proofing pilot reported that GSA held a webinar to review the in-person proofing process and provided documentation to these agencies detailing how in-person identity proofing fit into the overall identity proofing workflow.

· For the remote identity proofing pilot, we found that the program documentation fully aligns with this leading practice. Specifically, GSA provided documentation that showed that the agency shared IAL2 updates with stakeholders. These updates included information regarding Login.gov’s third party assessment process, information about the rollout phases for the remote biometric option and next steps for implementation. In addition, GSA provided a development update presentation for agency partners. This presentation included updates on Login.gov’s path to IAL2 compliance and showed a demo of how the remote identity proofing would work.

While GSA has taken steps to align Login.gov to NIST guidance, these two pilot programs do not fully follow leading practices for developing lessons learned. Incorporating these leading practices will give GSA greater assurance that the functionalities that are tested during the pilots will meet NIST guidelines.

Conclusions

As members of the public increasingly rely on the internet to access government services and benefits, it is critical for agencies to have a secure, reliable method for verifying those individuals’ identities. Agencies using Login.gov noted that the service provides benefits, but technical challenges are not being resolved in a timely fashion, potentially hindering its further adoption.

In addition, GSA has initiated pilot programs to ensure that Login.gov is aligned with federal digital identity guidelines, but one is not yet complete. Until this pilot is conducted and confirms the functionality is working as intended, GSA cannot be assured that Login.gov is aligned with IAL2 guidelines. Developing plans for identifying lessons learned can inform future efforts and will better position GSA to ensure Login.gov complies with these guidelines.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to the Administrator of the GSA:

The Administrator of GSA should direct the Technology Transformation Service division to propose actions to address the technical challenges that the agencies identified related to Login.gov and develop mutually agreed-upon time frames for taking those actions. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of GSA should direct the Technology Transformation Service division to establish a completion date for the remote identity-proofing pilot. (Recommendation 2)

The Administrator of GSA should direct the Technology Transformation Service division to ensure that it develops and documents a plan for lessons learned for Login.gov’s remote identity-proofing pilot program. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments, Third-Party Views, and Our Evaluation

We requested comments on a draft of this report from GSA and the other 23 CFO Act agencies included in our review. We also requested comments on relevant sections of the draft report from key third parties, including the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, Experian, ID.me, LexisNexis, and Okta. The one agency to which we made recommendations, GSA, agreed with those recommendations.

GSA and three other agencies provided written comments. Fifteen agencies provided emails noting that they had no comments. The remaining five agencies and the third parties provided only technical comments.

In written comments, the General Services Administration concurred with our recommendations and described steps planned or under way to address them. The Administrator stated that the agency is prioritizing the concerns noted in this report, including a self-service portal to provide agencies with increased visibility into usage metrics and a number of initiatives aimed at increased success rates.

In addition, GSA published a press release on October 9, 2024, announcing the conclusion of the remote identity proofing pilot and certification of Login.gov as an IAL2 compliant identity proofing solution. Specifically, GSA reported that partner agencies will now have the option to select a new IAL2-compliant capability that offers a higher identity assurance level. The press release states that the new capability adds one-to-one facial matching technology that allows Login.gov to confirm that a live “selfie” taken by a user matches the photo on an ID, such as a driver’s license, provided by the user. Further, the press release states that the IAL2 certification covers both the remote and in-person identity verification offerings, effectively ending their remote identity proofing pilot.

We confirmed that GSA obtained the IAL2 certification and verified that the agency now considers the pilot complete. Therefore, we plan to close recommendation two after we issue our report. GSA’s comments are reprinted in appendix II.

Three additional agencies provided written comments on the report:

· The Social Security Administration stated that it is working with GSA to improve fraud controls and prevent inappropriate or criminal access to the PII they safeguard. The comments are reprinted in appendix III.

· The U.S. Agency for International Development stated that it utilizes Login.gov to standardize and enhance user experiences for public-facing applications. The agency states that currently it does not have an immediate need to utilize GSA's identity proofing solution but will ensure it aligns with NIST's IAL2 guidelines before considering its use. The comments are reprinted in appendix IV.

· The Department of Veterans Affairs stated that a challenge it has experienced associated with Login.gov is that, as of June 2024, the system is not fully compliant with section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The department noted that ensuring access to information and communications technologies is essential to accomplishing its mission. The comments are reprinted in appendix V.

Further, fifteen agencies stated that they had no comment on the report. We received emails from the:

· Department of Agriculture’s Audit Liaison,

· Department of Education’s Audit Liaison,

· Department of Energy’s Audit Resolution Team,

· Health and Human Services’ GAO Intake Team,

· Department of Homeland Security’s Departmental GAO-OIG Liaison Office,

· Housing and Urban Development’s Audit Liaison Officer,

· Department of the Interior’s Audit Management Division,

· Department of Labor’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy,

· Department of State’s Sr. Management Analyst,

· Department of Transportation’s Audit Relations and Program Improvement Office,

· Department of Treasury’s Office of the Chief Information Officer,

· Environmental Protection Agency’s GAO Liaison,

· National Science Foundation’s GAO Liaison,

· Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Audit Liaison,

· Office of Personnel Management’s Audit Liaison, and

· Small Business Administration’s Audit Liaison.

Five agencies, the Departments of Commerce, Defense, Justice, and State, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, provided technical comments via email, which we incorporated as appropriate. We also received technical comments from the third parties, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the heads of the agencies in our review, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Marisol Cruz Cain at (202) 512-5017 or cruzcainm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Marisol Cruz Cain

Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

Our objectives were to determine (1) how Login.gov collects, shares, and protects PII while providing identity proofing services, (2) how many of the 24 Chief Financial Officers Act (CFO) agencies use Login.gov and what benefits and challenges have these agencies reported in their use, (3) the actions GSA is taking to align Login.gov with the requirements in NIST Digital Identity Guidelines,[49] and (4) the extent to which GSA’s actions are aligned with leading practices for pilot programs.

To address our first objective, we reviewed Login.gov program documentation such as the privacy impact assessment, system of records notice, and system security plan to identify what PII Login.gov collects during its identity proofing and verification process. We also determined how the PII is used and what processes are in place to prevent fraud. Also, we reviewed privacy impact assessments for third party services used by Login.gov to determine their role in the identity proofing process. Further, we conducted interviews with GSA officials responsible for Login.gov and relevant third-party services to gain a better understanding of the agency’s procedures for sharing and securing PII collected from Login.gov and the identity-proofing process.

To address our second objective, we conducted semi-structured interviews with the 24 CFO Act agencies to determine what identity proofing services each agency used to authenticate and verify users accessing their public-facing applications.[50] We also asked each agency that reported using Login.gov to describe the benefits and challenges they had experienced while using the service. We then analyzed the agency responses and identified three most frequently identified benefits and three most frequently identified challenges. We followed up with the agencies that reported using Login.gov to verify our assessment of their reported benefits and challenges, as well as to confirm when an agency reported not having experienced any benefits or challenges. In addition, we followed up with agencies that reported not using Login.gov to confirm the identity proofing service that was being used. Subsequently, we discussed the most frequently reported challenges and any actions to address them with GSA.

Regarding our third objective, we reviewed Login.gov documentation such as program road maps, implementation plans, flowcharts, and publicly available statements about program plans. Using these documents, we determined the steps GSA took or planned to take to align Login.gov with NIST Special Publication 800-63, Digital Identity Guidance. Additionally, we interviewed GSA officials regarding their actions or plans to address NIST’s identity guidance.

To address our fourth objective, we compared GSA’s two pilot programs to GAO’s five leading pilot program practices:[51]

1. Establish well-defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives.

2. Clearly articulate assessment methodology and data gathering strategy that addresses all components of the pilot program and includes key features of a sound plan.

3. Develop and document plans for lessons learned about the pilot to help inform decisions about scalability and whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts.

4. Develop a detailed data-analysis plan to track the pilot program’s implementation and performance and evaluate the final results of the project and draw conclusions on whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts.

5. Ensure appropriate two-way stakeholder communication and input at all stages of the pilot project, including design, implementation, data gathering, and assessment.

We then compared GSA’s pilot program documentation to leading practices to determine the extent to which the agency had incorporated them into their pilot programs. For the in-person proofing pilot, we analyzed pilot documentation to determine whether GSA met the leading practices. For the remote identity proofing pilot, we analyzed the agency’s plans for the pilot to determine whether those plans met the leading practices.

We shared the criteria against which we evaluated GSA’s efforts to address NIST Digital Identity Guidance with agency officials. GSA officials provided additional documentation and clarification on their efforts based on these criteria. Where warranted, we updated our analyses based on GSA responses and the additional information provided to reach a final score.

To score our analyses, we used the following scoring system:

· Fully aligns: we found evidence that satisfied the leading practice;

· Partially aligns: we found evidence that satisfied some portion of the leading practice; and

· Does not align: we found little or no evidence that satisfied the leading practice.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2022 to October 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Marisol Cruz Cain, (202) 512-5017 or CruzCainM@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact listed above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Elena Epps (Assistant Director), Kami Brown (Analyst-in-Charge), Lauri Barnes, Tracey Bass, Madison Brown, -Christopher Businsky, Chase Carroll, Kristi Dorsey, Jonnie Genova, Corwin Hayward, Keith Kim, Michael Lebowitz, Jess Lionne, Andrew Stavisky, Ibrahim Suleman, and Adam Vodraska.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]PII is any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, such as name, date or place of birth, and Social Security number; or that can otherwise be linked to an individual.

[2]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Digital Identity Guidelines, Special Publication 800-63-3; and Digital Identity Guidelines: Enrollment and Identity Proofing, Special Publication 800-63A (June 2017).

[3]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Digital Identity Guidelines, Special Publication 800-63-3 and Digital Identity Guidelines: Enrollment and Identity Proofing, Special Publication 800-63A (June 2017).

[4]The 24 agencies covered by the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 are the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Justice, Labor, State, Transportation, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs; the Environmental Protection Agency, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Science Foundation; Nuclear Regulatory Commission; Office of Personnel Management; Small Business Administration; Social Security Administration; General Services Administration; and the U.S. Agency for International Development. See 31 U.S.C. 901(b).

[5]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Digital Identity Guidelines and Digital Identity Guidelines: Enrollment and Identity Proofing.