NATIONAL NUCLEAR SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Fully Incorporating Leading Practices for Agency Reform Would Benefit Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Allison Bawden at (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106675, a report to congressional committees

NATIONAL NUCLEAR SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Fully Incorporating Leading Practices for Agency Reform Would Benefit Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative

Why GAO Did This Study

NNSA is the busiest it has been since the Cold War as it oversees a $200 billion nuclear modernization effort. Recognizing the need to address the agency’s increased demands, the NNSA Administrator established the Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative team in January 2022. The team’s report made recommendations to help NNSA better deliver on its national and global security missions. Several recommendations affect acquisition and program management at NNSA, which have been on GAO’s High Risk List for decades.

A report accompanying the fiscal year 2023 consolidated appropriations act includes a provision for GAO to evaluate the Initiative’s proposed implementation. This report (1) describes the Initiative report’s findings and recommendations and examines (2) NNSA’s plans for implementation and the status of the reforms, and (3) the extent to which NNSA’s six reforms GAO identified as at high risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement were aligned with selected leading practices for agency reform.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making eight recommendations to NNSA, including that it define how it will govern follow-on continuous improvement efforts; establish goals and processes to monitor reforms’ progress against those goals; and monitor reforms to ensure they do not increase risks of fraud, waste, and abuse. NNSA concurred with all eight recommendations.

What GAO Found

To address the increased demands of its estimated $200 billion nuclear weapon modernization effort, in September 2022, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) published a report titled Evolving the Nuclear Security Enterprise: A Report of the Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative. The report had recommendations for reforming its agency and contractor operating environment that covered many aspects of NNSA’s operations, including program and project management, employee recruitment and retention, and contracting.

NNSA used the results from the report to develop 15 reforms, which the agency has implemented through decentralized implementation teams under a central reporting structure. NNSA considers 11 reforms implemented and four ongoing. In addition to the continued development of the ongoing reforms, officials stated they will continue to monitor and modify the implemented reforms. However, the reporting structure that had been in use was disbanded by September 2024, and NNSA has not defined how it will govern follow-on continuous improvement efforts or monitor and report on their status.

Reforms Sought for Managing Weapon Modernization Programs

B-61 bomb, modernized under processes the National Nuclear Security Administration seeks to reform through the Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative.

NNSA’s implementation plans for six of the 15 reforms that GAO selected based on their relation to areas it previously identified as at risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement partially aligned with relevant leading practices for successful agency reform. These plans were most in alignment with leading practices on leadership focus and attention. However, most of the plans for the six high-risk reform areas did not fully align with leading practices for setting goals, using data and evidence, monitoring, addressing longstanding management challenges, and engaging key stakeholders. Without establishing goals or processes to collect data and evidence, NNSA will not be able to monitor the effectiveness of implemented and ongoing reforms. Without this information, NNSA cannot assess whether the underlying issues identified in the Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative report have been addressed. Further, by not monitoring the effects of relevant reforms on high-risk areas or the potential for fraud, waste, and abuse, NNSA will not know if reforms could potentially perpetuate longstanding challenges or increase risks of fraud, waste, and abuse.

Abbreviations

|

Cal/OSHA |

California Division of Occupational Safety and Health |

|

DA |

Design Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

EMDI |

Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative |

|

FFRDC |

federally funded research and development center |

|

IPA |

Intergovernmental Personnel Agreement |

|

M&O |

management and operating |

|

NNSA |

National Nuclear Security Administration |

|

OSHA |

Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

|

PA |

Production Agency |

|

PEMP |

Performance Evaluation and Measurement Plan |

|

PER |

Performance Evaluation Report |

|

PMI |

Project Management Institute, Inc. |

|

PRT |

product realization team |

|

SNL |

Sandia National Laboratories |

|

S&T |

science and technology |

|

TDY |

temporary duty |

|

UPF |

Uranium Processing Facility |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 6, 2025

The Honorable John Kennedy

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Chuck Fleischmann

Chairman

The Honorable Marcy Kaptur

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA)—a separately organized agency within the Department of Energy (DOE)—is responsible for maintaining and modernizing the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile and leading nonproliferation efforts, among other missions. According to NNSA, the nuclear security enterprise has been asked to take on more work than at any time since the Cold War. This includes the simultaneous sustainment, surveillance, modernization, design, and development of multiple nuclear weapons and components that have not been produced in decades. In 2023, the Congressional Budget Office estimated this modernization effort will cost NNSA over $200 billion through 2032. Further, NNSA faces significant operational challenges, including delays and cost overruns in major programs and projects.

Recognizing the need to address the increased demands and challenges facing the nuclear security enterprise, the NNSA Administrator established a team in January 2022 to review and provide recommendations to allow NNSA to better deliver on its national and global security missions. NNSA published the team’s report in September 2022, titled Evolving the Nuclear Security Enterprise: A Report of the Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative (EMDI). The report identified 18 recommendations for reform in areas such as contracting, managing the federal and contractor relationship, recruiting and retention of federal and contractor personnel, and program and project management.[1]

NNSA relies upon contracted services to accomplish most of its work. Its largest contracts are generally management and operating (M&O) contracts to carry out its program and project work at eight government-owned sites, collectively known as the nuclear security enterprise.[2] The M&O contractors are responsible for managing daily operations and executing program and project activities at the sites. NNSA’s federal workforce is responsible for (1) portfolio, program, and project management; and (2) oversight, control, integration, and decision-making functions of governance. Contract and project management at DOE—including NNSA—has been on our High Risk List since 1990 because DOE’s record of inadequate management and oversight of contractors left the agency vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement.[3]

The Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for us to evaluate the proposed implementation of NNSA’s EMDI.[4] This report (1) describes the EMDI report’s findings and recommendations, (2) examines NNSA’s plans for EMDI implementation and the status of EMDI reforms, and (3) examines the extent to which selected EMDI implementation plans related to areas we identified as at high risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement—such as acquisition and program management—were aligned with selected leading practices for agency reform.

For the first objective, we analyzed the EMDI’s report findings and recommendations and discussed them with NNSA officials.

For the second objective, we examined EMDI project charters, success indicator forms, NNSA’s EMDI progress tracker, presentation slides, guidance produced by EMDI teams, and other implementation documentation. We analyzed the actions taken by EMDI teams, characteristics of EMDI efforts, changes to EMDI implementation plans over time, and future plans. In addition, to assess these future plans, we reviewed the Project Management Institute, Inc’s Continuous Improvement Practices.[5] We also conducted interviews with members of the 14 EMDI implementation teams (out of 15) who had project charters completed by July 2023 to clarify the information in the project charters and other implementation plan documents, identify additional relevant documentation, and fill in information gaps.

For the third objective, we selected six implementation plans out of 15 for review because they were associated with reforms that (1) related to areas we have previously determined are at high risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement; and (2) focused on multiple sites. Throughout the report, we refer to these six as “high-risk reforms.”

We also determined which of the leading agency reform practices identified in our prior work were most relevant to EMDI implementation plans.[6] Two analysts independently reviewed the leading practices to determine their relevance to NNSA and selected EMDI reforms. The analysts then met to reconcile any differences and reach agreement on which practices to eliminate as not relevant. We determined that 24 selected key questions under eight leading practices were applicable to EMDI reform implementation plans. See appendix I for our full methodology for selecting which implementation plans met our criteria for high risk and which leading agency reform practices were most relevant.

We then assessed whether each of the selected EMDI implementation plans aligned, partially aligned, minimally aligned, or did not align with each of the selected leading practices for agency reform. To assess the implementation plans against leading practices for agency reform, two analysts independently compared the implementation plans against each of the selected practices and came to an agreement on the extent to which the plans aligned with the practices. We then conducted follow-up interviews with NNSA officials to obtain additional information regarding areas initially assessed as partially, minimally, or not aligned and incorporated such information into our final assessments as appropriate. See appendix I for the full methodology used to assess NNSA’s EMDI implementation plans.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

NNSA’s Organization

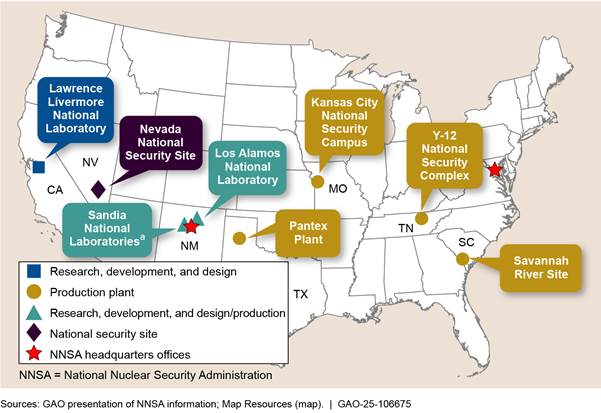

NNSA was established by law in October 1999 as a separately organized agency within DOE in response to long-standing management and governance challenges, especially DOE’s management and governance of its nuclear weapons program.[7] NNSA’s current federal workforce is based in headquarters offices located in Washington, D.C.; Germantown, Maryland; and Albuquerque, New Mexico, as well as in field-based offices collocated at eight government-owned, contractor-operated sites (see fig. 1). These eight sites are operated by M&O contractors that manage daily operations and execute program and project activities.

aSandia National Laboratories has two primary locations in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Livermore, California.

NNSA sites conduct a wide variety of research, development, testing, and evaluation missions as well as production missions. Three NNSA national laboratories—responsible for nuclear weapons design—are known as design agencies. The four sites that primarily have a production mission are known as production agencies.[8] Collectively, there were approximately 59,000 M&O contractor staff across NNSA’s sites in fiscal year 2022.

NNSA’s mission work is generally directed by headquarters-based federal program offices. Federal program managers are to help develop requirements, define performance standards, and ensure that contractors’ activities achieve intended outcomes. NNSA’s program activities often span multiple sites. For example, any weapon modernization programs generally require all eight sites to collaborate, as do many production modernization programs such as plutonium modernization. Federal field office staff are responsible for multiple oversight functions at the site level—which NNSA describes as mission-enabling—including contract management, safety, and security. As such, federal field office staff are to provide day-to-day oversight of the M&O contractors’ performance. NNSA’s federal workforce consisted of about 1,800 full-time equivalent employees in fiscal year 2022.

M&O Contracts and the Federal-Contractor Relationship

NNSA obligated about $18 billion to its M&O contracts in fiscal year 2023. M&O contractors are responsible for managing daily operations and executing program and project activities. The Federal Acquisition Regulation defines M&O contracts as agreements under which the government contracts for the operation, maintenance, or support, on its behalf, of a government-owned or government-controlled research, development, special production, or testing establishment, wholly or principally devoted to one or more major programs of the contracting agency.[9] According to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, an M&O contract is characterized both by its purpose and by the special relationship it creates between the government and contractor.[10]

Since the advent of NNSA, Congress and other observers have raised questions about the nuclear security enterprise’s ability to deliver on its mission in a timely and cost-effective manner. Numerous reports and commissions have assessed the governance of the nuclear security enterprise and the special relationship between M&O contractors and the federal managers overseeing them. These external and internal panels have proposed a variety of reforms to improve the management and operation of the nuclear security enterprise to meet the growing challenges of nuclear modernization.[11]

Similarly, in August 2016, we identified three key attributes associated with DOE’s M&O contracts,[12] which included NNSA’s M&O contracts:

· Limited competitive environment. We found that M&O contracts included longer terms than other federal contracts, so they were competed less frequently. In addition, according to DOE officials at the time, there were few contractors able to perform the highly technical and broad-ranging work that is done under M&O contracts.[13]

· Broad scopes of work. DOE M&O contracts had broad scopes of work that covered nearly all aspects of work at a site. Although mission activities of M&O contractors could be highly technical, we found that mission support activities generally accounted for about 25 to 50 percent of contractors’ total costs in fiscal year 2015 and encompassed such things as managing infrastructure, facilities, grounds, and security.

· Closer relationship. M&O contracts and DOE management practices contributed to a closer relationship between M&O contractors and the government. For example, we reported that M&O contractors were generally more integrated with DOE in how they were paid and in their accounting systems than other types of contractors. With regard to payment, rather than traditional bill payment methods—including invoices, payment approval and authorization, and disbursement of funds—M&O contractors can draw funds directly from federal accounts through “letter of credit financing,” and costs are intended to be reviewed annually for their allowability under the contract.

This special federal–contractor relationship that characterizes M&O contracts manifests itself in many ways, including the following:

Contract type and incentives. All NNSA’s M&O contracts are cost-reimbursement contracts, with award or fixed fees. Cost-reimbursement type contracts allow the agency to contract for work when circumstances do not allow the agency to sufficiently define its requirements or estimate its costs to allow for a fixed-price contract. Under a fixed-price contract, a contractor accepts responsibility for completing a specified amount of work for a fixed price. In contrast, under cost-reimbursement contracts, the government reimburses a contractor for allowable costs incurred, to the extent prescribed by the contract. Further, in the case of NNSA’s M&O contracts, the level of work the contractor is directed to complete can change based on the agency’s annual appropriations. The government may also pay a fee that is either fixed at the outset of the contract or adjustable based on performance criteria set out in the contract.

Contract term. According to NNSA officials, since the early 2000s, NNSA’s M&O contracts have generally had a base contract term of 5 years, with options to extend a contract at 1 or 2 year increments up to a term of 10 years. In addition, several of the contracts have included an incentive to earn additional contract term as awards for performance.[14] Some contracts have been or are expected to be extended non-competitively in anticipation of new contract competitions; NNSA has in some cases cited its acquisition capacity as a reason for these delays.

Contract performance evaluation. NNSA evaluates the performance of M&O contractors through annual evaluations. The Performance Evaluation and Measurement Plan is to be developed before the beginning of each fiscal year (that is, the beginning of the evaluation period). It establishes expectations for the site contractor’s performance and describes how the responsible NNSA offices will evaluate and measure performance against those expectations. The plan is to provide the blueprint for how the evaluations will be used to determine award fees, award terms, and any other incentives. The Performance Evaluation Report is to be developed at the end of each evaluation period. NNSA uses this report to document the performance rating and, in some cases, the fees and other incentives that will be awarded to the contractor.

Subcontracting oversight. We have found that a significant amount of work in the nuclear security enterprise is performed through subcontracts. For example, an M&O contractor may enter into a subcontract to obtain access to a specific set of skills or services that it may not possess, such as construction expertise, equipment services, or technology support. NNSA is responsible for monitoring contractors’ compliance with subcontracting requirements by assessing and approving their procurement systems, as well as their policies and procedures. NNSA is to monitor whether an M&O contractor is following its approved procurement system policies and procedures by providing consent to the contractors to award certain subcontracts. NNSA determines the subcontract actions that require consent in accordance with criteria such as subcontract dollar value and type of contract.

For subcontracts that are subject to a consent review, the contractor is to submit a package of information to the local NNSA contracting officer at the field office. The contracting officer either provides consent or raises issues that the contractor must address before awarding the subcontract. Although consent reviews have the potential to provide contracting officers with important information on the contractor’s compliance with requirements, they are subject to a minimum contract value requirement, and, as we previously reported, the number of reviews conducted by field offices each year varies due to different contract value thresholds at each location.[15] DOE guidance recommends that when establishing the threshold for consent reviews, the contracting officer should aim to review enough subcontracts annually to provide the field office with sufficient visibility into subcontracting actions without being overly burdensome on either the contractor or the federal staff.[16]

Involvement in contractor human resource issues. The special relationship also means an M&O contractor generally shares more data with the government than non-M&O contractors generally do. This includes NNSA oversight of M&O contractors’ human resource functions, including recruitment and retention. NNSA’s Contractor Human Resources Branch, through its Office of Partnership and Acquisition Services, works directly with M&O contractors’ human resources leaders to review and determine approval of requests related to actions that alter contractor workforce compensation or benefits. In general, any human resources actions that are precedent setting, cost increasing (with respect to the overall cost of the contract), or highly sensitive need NNSA approval, according to NNSA officials. For example, NNSA is responsible for reviewing and approving the M&O contractors’ annual compensation increase packages and benefits costs for their workforces. According to NNSA officials, NNSA’s guidance identifies over 30 actions requiring approval or review, with multiple NNSA offices’ involvement depending on the action. These various actions require approval as they occur and are not annual approvals.

Construction projects. Managing large and complicated sites means construction and maintenance projects of various sizes are a significant element of the scope of M&O contracts. These sites include both unique nuclear facilities and security infrastructure, as well as an extensive network of general infrastructure (offices, roads, and parking). As of June 2024, NNSA’s line-item construction project portfolio included over 40 projects collectively estimated to cost over $50 billion.[17] In addition to those major projects, M&O contractors carry out over 100 minor construction projects each year at NNSA’s eight sites.[18] These projects include additions, new or replacement facilities, and installations or upgrades that do not change a facility’s footprint.

U.S. Strategic Nuclear Modernization

The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review noted that, in recent years, the international security environment has deteriorated with the U.S. facing, for the first time in its history, two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.[19] This evolving threat environment has shortened time frames and increased workload for the nuclear security enterprise. NNSA’s scope of work and budget have increased, and NNSA’s efforts are centered on simultaneously sustaining and modernizing U.S. nuclear weapons and modernizing and recapitalizing its production infrastructure.[20] To meet Department of Defense requirements and congressional direction, NNSA is currently undertaking seven nuclear weapon modernization programs. NNSA’s cost estimates for these efforts range from approximately $3 billion to $25 billion each. In addition, NNSA plans to conduct two studies to evaluate options to meet potential future military needs.

Concurrent with and in service of NNSA’s weapons modernization, NNSA is also modernizing its outdated production infrastructure for capabilities such as those needed to produce plutonium pits, uranium secondaries, high explosives, and non-nuclear components at scale.[21] NNSA officials have described the $200 billion effort to modernize, expand, and manufacture a modern, safe, and reliable U.S. arsenal in a limited time frame as the busiest it has been in 3 decades. NNSA also must maintain and plan for its research, development, testing, and evaluation mission—such as subcritical testing, high-powered lasers, and high-performance computing—as well as support its global security mission through nonproliferation and counterproliferation efforts. Accomplishment of all these missions is made more difficult, according to NNSA officials, by employee turnover.

NNSA has faced challenges meeting these missions in a timely and efficient manner. While NNSA successfully completed weapon modernization programs in 2018 and 2020, most major programs and projects have seen schedule slips in the past 5 years. For example, as we reported in December 2024, component issues in the April 2019 time frame caused schedule slips of about 1 year to 18 months for two modernization programs. These delays added about $850 million to the programs’ costs. In August 2023, we found that 18 of NNSA’s major construction projects had a combined cost overrun of $2.1 billion and schedule delays of about 10 years. Since then, cost increases and schedule delays have worsened in many cases. For example, in December 2024, DOE approved NNSA’s revised schedule for the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) at Y-12 that would take 6 more years to complete than planned. This delay will result in cost increases estimated to be up to $3.8 billion, as of June 2024, according to agency documents. Further, as stated by defense officials in congressional testimony, NNSA will not meet statutory and military requirements to produce 80 plutonium pits per year during 2030. As we found in January 2023, NNSA will not have an overall idea of total program costs or when program objectives, to include the capability to produce 80 pits per year, will be reached until it establishes a comprehensive schedule or cost estimate.[22]

NNSA’s Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative

The deteriorating international security environment, related growth in NNSA’s workload, and the agency’s challenges executing this modernization mission helped spur EMDI. NNSA officials noted that NNSA’s missions are very time constrained and “no-fail.” In January 2022, the NNSA Administrator established its EMDI team to review and provide recommendations to allow NNSA’s nuclear security enterprise to better deliver its national and global security missions.

The EMDI team was assembled by the Associate Deputy Principal Administrator in January 2022. The team was led by three NNSA senior executives, two senior federal procurement officials (from NNSA and DOE’s Office of Science), and one report coordinator. The team conducted about 250 interviews with senior leaders and experts (including mostly current and former NNSA officials and representatives from M&O contractors, as well as some Department of Defense employees) to inform its work. NNSA published its EMDI report in September 2022.[23]

According to the report, the EMDI report authors scoped their work to (1) identify obstacles to the nuclear security enterprise’s agility and responsiveness to new challenges and requirements and (2) assess the relationships between the federal and M&O workforces, including contractual arrangements and other processes.

Our High Risk List

Since the early 1990s, our High-Risk Series has focused attention on government operations with greater vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or that are in need of transformation to address economy, efficiency, or effectiveness challenges. Since 1990, aspects of DOE’s—including NNSA’s—acquisition and management have been on our High Risk List because DOE’s record of inadequate management and oversight of contractors left the department vulnerable to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement.

In 2023, we updated the title of this high-risk area from Contract and Project Management to Acquisition and Program Management for DOE’s NNSA and Office of Environmental Management.[24] The title now more accurately represents the full range of challenges we have reported in this high-risk area since 1990. These challenges include issues such as the acquisition function, program and project management, and financial management. We found that NNSA needs to improve oversight of its acquisition processes and better manage its portfolios, programs, and projects.

We rate high-risk areas against five criteria. As of 2023, we determined that for NNSA’s Acquisition and Program Management, four of the five criteria needed attention: capacity, action plan, monitoring, and demonstrated progress. We rated the remaining criterion, leadership commitment, as “met” in recognition that NNSA has shown leadership commitment to improving acquisition and program management.

Leading Practices for Agency Reform

We have found that effective government transformation initiatives, such as EMDI, require a combination of people, processes, technologies, and other critical success factors to achieve results. Our June 2018 report describes leading practices that government agencies can use in agency reform efforts, including efforts to streamline and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of operations.[25] To develop these leading practices, we reviewed prior work and leading practices on organizational transformations; collaboration; government streamlining and efficiency; fragmentation, overlap, and duplication; high-risk; and on other agency long-standing management challenges. We also identified subject matter specialists knowledgeable about issues related to government reform and strategic human capital management who reviewed and commented on these practices.

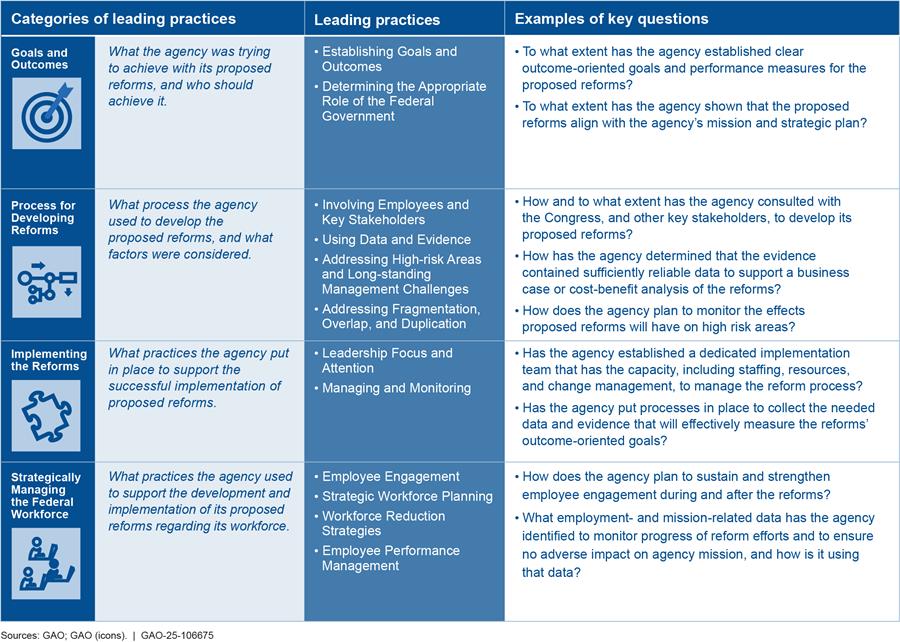

Our June 2018 report describes 12 leading practices and identifies 58 key questions that can be used to assess the development and implementation of agency reforms. The 12 leading practices fall under four broad categories: (1) goals and outcomes, (2) process for developing reforms, (3) implementing the reforms, and (4) strategically managing the federal workforce. See figure 2 for a list of the leading practices and examples of key questions.

NNSA Recommended Changes to Its Operating Environment Based on Findings from Its EMDI Report

The EMDI report described a variety of issues that senior leaders and experts identified with the nuclear security enterprise’s current operating environment and proposed 18 recommendations for changing its direction.[26] According to the EMDI report, NNSA’s current way of operating will not enable the agency to meet its increasing mission workload. Further, the report found that the contractual arrangements, processes, and relationships between federal staff and M&O contractors must change to meet NNSA’s mission goals. The report also found that the nuclear security enterprise is facing “tremendous” workforce attraction and retention issues.

Each recommendation in the report generally has its own discussion of the relevant issues found by the EMDI report team, which appears in the text preceding the recommendation. According to NNSA officials responsible for preparing the EMDI report, the recommendations were based on interviews with senior leaders and findings in past reports from internal and external review panels.[27] At least 12 of the 18 recommendations are substantially similar to recommendations made in prior external reviews of the governance of the nuclear security enterprise and the special relationship between M&O contractors and the federal managers, indicating that challenges previously identified had not been fully resolved.

According to NNSA officials, the EMDI report’s recommendations address the need to increase the speed and efficiency of nuclear security enterprise modernization or improve workforce recruitment and retention. In addition, two recommendations are focused on strategic planning efforts. See appendix II for the full text of NNSA’s EMDI report recommendations. We summarize individual findings and recommendations below:

· Contract award fees (EMDI 1): The report found that the award and performance fees in NNSA’s current M&O contracts were not a motivator for the majority of the workforce across the enterprise, and the focus on such fees was not appropriate for the special M&O contract relationship. The report recommended that NNSA develop a plan to discontinue the award fee model.

· Contract terms (EMDI 2): The report found that contract competitions and transition periods, as well as extending contracts 1 or 2 years at a time, are disruptive. According to the report, the process of recompeting a contract absorbs contractor leadership attention for about 2 years of the contract—the year before the competition and the year of transition after the contract is awarded. The report recommended that NNSA should transition all M&O contracts to a 5-year base period with 5-year extensions.

· Contract streamlining (EMDI 3): The report found that there was opportunity to review and revise contracts so that both federal and M&O contractor leadership understand what elements are helpful or detrimental to the M&O model and to streamline the contract. The report recommended that NNSA and M&O contractors streamline existing NNSA contracts using the Office of Science Revolutionary Working Group and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory contracts as a model.[28]

· Contractor performance evaluation process (EMDI 4): The report found that Performance Evaluation Measurement Plans and Performance Evaluation Reports were not consistently linked to NNSA’s strategic priorities and were viewed by M&O contractors as being too subjective and inconsistently applied. The report recommended that NNSA should adjust the Performance Evaluation Measurement Plan development and Performance Evaluation Report feedback process to be more transparent, allowing for meaningful feedback from M&O leadership prior to finalization.

· Controls on contractor salary and benefits (EMDI 5): The report found that NNSA’s internal controls on salary and benefits hinder M&O workforce competitiveness and efforts to recruit and retain qualified personnel. The report recommended that NNSA dramatically reduce or remove internal controls governing M&O employees’ direct and variable compensation and allow the M&O contractors to manage their workforces’ compensation packages within a given budget.

· Workforce office space (EMDI 6): The report found that inadequate workspaces negatively affect NNSA and M&O contractor workforce recruitment and retention. The report recommended that NNSA should improve and modernize its office, light laboratory, and light industrial spaces for its federal and M&O contractor personnel.

· Retired annuitants (EMDI 7): The report found that postemployment authorities covering pension-drawing contractor retirees were considered too limited and restrictive to retain much-needed M&O senior experts. The report recommended that NNSA work with the M&O contractors to develop a common plan to allow M&O annuitants and retirees to be compensated fairly for post-retirement service.

· Risk aversion and processes, procedures, and requirements (EMDI 8a, 8b, 8c, and 8d): The report found that “risk aversion”—the belief and related behavior that risks must be eliminated instead of managed or accepted—has deeply penetrated NNSA headquarters program offices, field offices, and M&O contractor leadership and workforces. It said that risk aversion has led to an accumulation and interpretation of requirements, procedures, and processes that must be completed before an action or decision is taken, which creates friction in the system. Additionally, the report found that multiple reviews and concurrences consume much time and engender lots of debate, but seldom substantially change the original product or plan content. The report also found that it was challenging to keep up with changes to existing requirements and implementation of newer requirements. According to the report, in a few cases, some requirements were developed without any or only limited consideration of effects on operations, activities, and associated facilities.

The report made a four-part recommendation (8a through 8d) that NNSA should (a) review major processes and procedures to reduce complexity and standardize implementation of requirements across sites and delegate certain approval authorities to field office staff; (b) explore giving M&O contractors greater approval and decision authority without prior federal review, shifting federal review to evaluation of outcomes; (c) establish deadlines for Headquarters approvals, with default approval if the deadline is hit without reply; and (d) require more formal justifications, cost and mission impact determinations, and coordination with impacted field offices and M&O contractors before accepting new or changed directives or requirements.

· Subcontracting approvals (EMDI 9): The report found that inconsistencies and perceived redundancies in NNSA’s required, “low risk” consent reviews of planned M&O subcontracts increased process time with little benefit. The report recommended that NNSA should reduce approval requirements for M&O contractors’ subcontracting actions and consent reviews considered “low risk.”

· Low-risk commercial-like construction (EMDI 10): The report found construction of low complexity commercial-like buildings or light manufacturing spaces would be helped by reducing competing requirements in DOE orders and state or local construction codes. The report recommended that NNSA reduce requirements for low-risk commercial-like construction and request congressional approval to raise the monetary threshold for what is considered “minor” construction.

· Risk-taking and risk acceptance (EMDI 11): The report found that there is no reward for risk taking or risk acceptance, either by M&O contractors or federal staff. This leads, according to the report, to the laboratories being very conservative in testing requirements and overly restrictive in design requirements, while continually striving for design perfection instead of simply meeting requirements. The report also said that this is counter to the M&O model and that the laboratories have forgotten how to manage risk, due in part to the roughly 40 percent of their workforce with less than 5 years of experience in the nuclear security enterprise. The report recommended that NNSA develop improved training for federal and contractor program managers on the special federal-contractor relationship. It also recommended that NNSA reward risk taking and associated risk management by M&O contractors and federal staff that balances mission, security, safety, and other requirements.

· Integrated priorities (EMDI 12): The report found that a lack of inter-program integration and prioritization within NNSA leads to “prioritization collisions” at the sites and inefficient communication to site management—both M&O contractor and field office. The report recommended that NNSA develop and provide an integrated and prioritized mission deliverable list across all aspects of the NNSA portfolio to each operating location.

· Headquarters’ understanding of field (EMDI 13): The report found there was a lack of empathy between disparate geographic workforces, with NNSA headquarters staff not recognizing the realities of competing program execution requirements in the field. The report recommended that NNSA increase opportunities for NNSA headquarters staff to work with NNSA field office and M&O workforces through rotations, details, or regular travel.

· Contractors’ understanding of NNSA headquarters (EMDI 14): The report found there was a lack of empathy between disparate geographic workforces, with distance from Washington, D.C., removing context and awareness of the pressures driving NNSA headquarters data calls and decisions from many M&O contractors’ employees’ views. The report recommended that NNSA develop a simplified approval process for Intergovernmental Personnel Agreements and a financially neutral approach for M&O employee rotational assignments to encourage effective interaction between headquarters and field expertise.[29]

· Data calls, reporting, and briefings (EMDI 15): The report found that an increased number of data calls, reporting requirements, project controls, reviews, and briefings to federal program managers are burdensome and often do not add value.[30] The report recommended that NNSA federal program staff should make fewer data requests, have fewer “federal only” meetings, and allow M&O contractors to participate directly in briefings to internal and external groups, including the Department of Defense and Congress.

· Process and program controls (EMDI 16): The report found that accrued process and program controls and reviews consume significant manpower. The report recommended that NNSA’s Office of Defense Programs reduce process and program controls identified through a joint headquarters, field office, and M&O contractor group.

· Design and production agencies (EMDI 17): The report found that design and production agencies’ roles and responsibilities lacked clarity and balance. The report did not explain how the relationship was imbalanced or unequal, but said that a more balanced relationship is needed, with equal responsibility and accountability for final product delivery. The report recommended that NNSA’s Office of Defense Programs lead a review to rebalance the relationship between design agencies and production agencies to result in more equal authority and accountability.

· Science, technology, and engineering infrastructure (EMDI 18): The report found that there is not an integrated, long-term plan across the nuclear security enterprise to recapitalize and revitalize science and engineering capabilities and infrastructure, including everything from light laboratory and general experimental infrastructure to major new science and engineering capabilities. The report recommended that NNSA develop an integrated strategic plan to revitalize this science, technology, and engineering infrastructure.[31]

NNSA Considers Most EMDI Reforms Implemented but Has Not Formalized How It Will Evaluate Reforms’ Effectiveness or Plan for Future Improvement Efforts

NNSA considers most of the 15 reforms it developed under EMDI implemented, with implementation activities led by decentralized teams under a central reporting structure. Some of the reforms that were pursued changed significantly during implementation from their original conception. Although NNSA considers most EMDI reforms implemented, activities are continuing to monitor reforms, and NNSA plans to pursue further continuous improvement efforts. However, officials told us that the agency has not formalized its approach to governing these longer-term efforts.

Implementation of EMDI-Related Reforms Has Been Executed by Decentralized Teams from Across NNSA

NNSA ultimately developed 15 reforms associated with EMDI, which mostly, but not always, map to the 18 recommendations included in the EMDI report. See table 1 for EMDI reforms and a crosswalk to the original recommendations made in the September 2022 EMDI report.

Table 1: Crosswalk Between Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative (EMDI) Reforms and Related EMDI Report Recommendations

|

EMDI reform |

Related EMDI report recommendation(s) |

|

Management and Operating (M&O) Contract Term and Award Fee Model |

EMDI 1 EMDI 2 |

|

Streamline M&O Prime Contracts |

EMDI 3 |

|

Improve the Corporate Performance Evaluation Process |

EMDI 4 |

|

Controls on Compensation |

EMDI 5 |

|

Modernization of Workforce Office Space |

EMDI 6 |

|

Use of Retired Annuitants |

EMDI 7 |

|

Addressing Backlog of Telecommunications Security Reviews |

Not applicablea |

|

Improving the Concurrence Process |

Not applicablea |

|

Improving Modernization Programs Efficiency Pilot |

EMDI 8A-D EMDI 11 EMDI 15 EMDI 16 EMDI 17 |

|

Improve M&O Subcontracting Efficiency |

EMDI 9 |

|

Waive DOE Project Order for Low-Risk Commercial-Like Construction |

EMDI 10 |

|

Integrated Strategic Priorities List |

EMDI 12 |

|

Improving Off-Site Assignments |

EMDI 13 |

|

Increasing Rotations Between M&Os and NNSA |

EMDI 14 |

|

Develop an Integrated Strategic Plan for Science, Technology & Engineering |

EMDI 18 |

Source: GAO analysis of National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) documentation. | GAO‑25‑106675

aNNSA officials included two reforms under EMDI implementation teams that were not directly mentioned in the EMDI report’s 18 recommendations. NNSA officials told us these were included because they generally addressed EMDI themes of improving speed and efficiency.

NNSA created an implementation team to develop and implement each reform. NNSA officials stated that the 15 implementation teams are composed of employees working on these teams in addition to their regular duties, some of whom were recruited based on their specific positions, skills, and experience. Officials told us that some implementation teams are made up entirely of federal employees, while others include a mix of federal and M&O contractor employees.

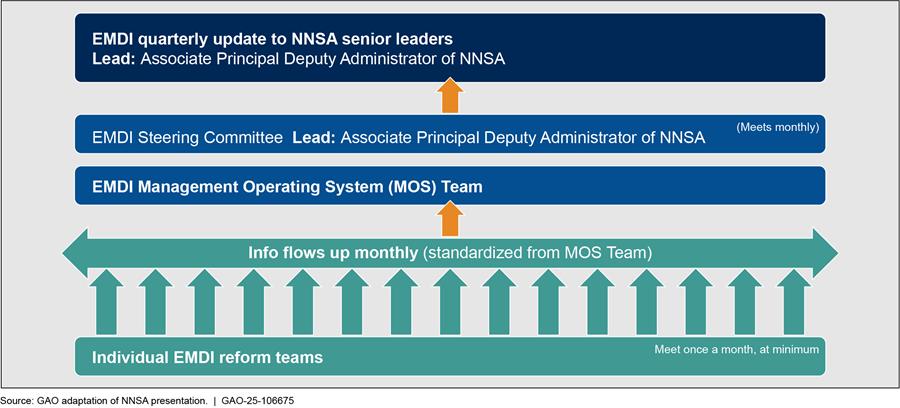

According to agency officials, NNSA created an EMDI implementation structure in spring 2023 to monitor the progress of the implementation teams. As shown in figure 3, the implementation structure initially required implementation teams to report on their progress monthly through a Management Operating System Team and a Steering Committee—both dedicated to the EMDI effort—to senior NNSA leadership. Agency officials told us that the Management Operating System Team was assigned five full-time staff to support the effort. By September 2024 and as implementation progressed, this structure was disbanded in favor of each implementation team that was still conducting work reporting as needed to the Associate Principal Deputy Administrator of NNSA.

Figure 3: National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) Implementation Structure for Initial Implementation of Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative (EMDI) Reforms

As part of the EMDI implementation process, the Management Operating System Team provided a template for each implementation team to create a charter for the 15 EMDI reforms. The charters included fields for general information, such as a list of team members, statement of the problem, major deliverables, and performance metrics. Each implementation team completed a charter, which NNSA provided to us.

NNSA Considers Most EMDI Reforms Implemented, and Some Reforms Changed During Implementation from Their Original Conception

As of September 2024, NNSA officials considered 11 EMDI reforms implemented and four as ongoing. According to NNSA, “implemented” means that the EMDI implementation team is no longer taking any significant actions related to implementing the reform. It is not necessarily indicative of whether the underlying issue that was identified in the original EMDI report is addressed or not. Officials have stated that they will continue to monitor the implemented reforms and make modifications to them as necessary.

Four ongoing reforms are still conducting significant actions associated with implementing their reforms. For example, members of the Improving Off-Site Assignments reform implementation team stated that, as of April 2024, the team was continuing to search for new ways to share information throughout the agency regarding off-site assignments. Members also told us that the team was continuing to hold meetings to evaluate the agency’s policies for all types of off-site assignments and to identify ways NNSA can improve the program. See table 2 for a full list of EMDI reforms’ implementation status.

Table 2: National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) Assessment of Implementation Status of Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative (EMDI) Reforms, as of September 2024

|

Title of EMDI reform |

Implementation status as of September 2024 |

|

M&O Contract Term and Award Fee Model |

Implemented |

|

Streamline M&O Prime Contracts |

Ongoing |

|

Improve the Corporate Performance Evaluation Process |

Implemented |

|

Controls on Compensation |

Implemented |

|

Modernization of Workforce Office Space |

Implemented |

|

Use of Retired Annuitants |

Implemented |

|

Addressing Backlog of Telecommunications Security Reviews |

Implemented |

|

Improving the Concurrence Process |

Implemented |

|

Improving Modernization Programs Efficiency Pilot |

Ongoing |

|

Improve M&O Subcontracting Efficiency |

Implemented |

|

Waive DOE Project Order for Low-Risk Commercial-Like Construction |

Implemented |

|

Integrated Strategic Priorities List |

Implemented |

|

Increasing Rotations Between M&Os and NNSA |

Ongoing |

|

Improving Off-Site Assignments |

Ongoing |

|

Develop an Integrated Strategic Plan for Science, Technology & Engineering |

Implemented |

M&O = management and operating; DOE = Department of Energy

Source: NNSA EMDI Tracker. | GAO‑25‑106675

Note: NNSA has defined “implemented” to mean that the EMDI implementation team is no longer taking any significant actions related to implementing the reform. NNSA officials have stated that they will continue to monitor the implemented reforms and make modifications to them as necessary.

We found that in some cases the reforms NNSA has implemented, or is still working to implement, generally adhere to how the reforms were originally conceived while others have changed significantly. Because NNSA’s definition of “implemented” only considers the extent to which activities on the reform continue, identifying a reform as “implemented” does not necessarily mean it has met all its objectives. As noted above, in part due to decentralized implementation, as well as the varying scopes and types of reforms NNSA pursued, implementation of each reform has progressed at its own pace and with varying degrees of change from the original EMDI report conception. Each reform discussed below describes actions taken by the reform implementation teams and, if applicable, the extent to which the reform changed from its original conception.

· The M&O Contract Term and Award Fee Model team told us it decided not to pursue discontinuing the award fee contracting model. Team members said they made this decision because of concerns that, due to federal acquisition regulations on fixed fees, moving from award fees to entirely fixed fees would result in a smaller fee on a percentage basis and thus not serve as a proper incentive. The same team told us that NNSA would extend all existing M&O contracts (excluding the single contract in place at the time to manage and operate Pantex and Y-12, which was extended for Y-12 only) to their maximum term allowed through contract options. Additionally, team members told us that they worked with contracting officers to pursue an acquisition to manage and operate Pantex alone that would last 5 years with three possible 5-year extensions instead of the typical 5-year contract with five possible 1-year extensions. Although NNSA considers this reform implemented, the team stated that it will evaluate the new June 2024 Pantex contract as a model for future contracts as part of the agency’s EMDI follow-up activities.

· The Streamline M&O Prime Contracts team determined that the site contract model it had sought for the agency to implement was not applicable to its pilot site, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (Livermore), due to significant differences between the two sites such as complexity and hazardousness of mission and the organizational structure of the entities that comprise each M&O contractor. Instead of pursuing implementation of the site model contract, the team stated that it was working to improve the contracting process at Livermore by identifying and addressing “pain points.” The team created a list of over 200 pain points. After reviewing the pain points list, members of the team told us that most of the issues were not tied to contract requirements. Rather, officials said that pain points were generally caused by old policies and guidance that were either internal to Livermore or provided by the Livermore Field Office. As of April 2024, NNSA officials stated that this reform effort is ongoing and limited to Livermore and its field office.

· The Improve the Corporate Performance Evaluation Process team told us they worked with contracting officers to adjust the Performance Evaluation and Measurement Plans and Performance Evaluation Report feedback processes in a way that NNSA believes will be more transparent, have better alignment on priority timelines, and better identify key outcomes. In addition, the team stated that, as a result of this reform, NNSA has begun piloting a software tool to capture and track performance feedback from offices across NNSA that will also document NNSA’s process of concurrence and approval on performance ratings.[32] We found that this reform largely adhered to its original conception, and NNSA considers this reform implemented.

· The Controls on Compensation team told us they decided not to pursue the reduction or removal of internal controls governing M&O contractor employees’ direct and variable compensation. NNSA officials said they are not pursuing this reform because it would be challenging to establish whether the costs for certain human resources actions are reasonable and to forecast the increased costs that benefits or salary enhancements would have in the future on the agency’s budget requests. In the team’s project charter, NNSA officials also cited compliance with compensation laws and policies as an obstacle to moving forward. Instead, the team told us they took related actions to provide M&O contractors more flexibility on compensation in 2024.[33] Specifically, in conjunction with M&O contractors, NNSA completed a review of industry surveys used in the agency’s annual Compensation Increase Plan, and NNSA officials said they modified the calendar year 2024 Compensation Increase Plan guidance accordingly.[34] NNSA considers this reform implemented.

· The Modernization of Workforce Office Space team told us it continued the implementation of office modernization efforts that were underway prior to EMDI, including utilizing new supply chain management strategies, a design library, and project execution board. Efforts also include completing construction of a significant amount of additional office space. According to NNSA documentation, some of these initiatives have been underway since at least 2016, such as the supply chain management strategies, which NNSA uses to increase quality, enhance buying power, and accelerate the delivery for repairing and replacing major common building systems. Officials felt that incorporating these ongoing efforts into EMDI would give extra focus to their implementation teams and reinforce the importance of these projects. Officials stated that office space modernization efforts are being implemented across the enterprise and include construction of new facilities, development of standard office building designs, and streamlined construction contracting strategies. As of September 2024, officials said that these streamlining initiatives have been used to execute M&O contractor led modernization activities, but they are being evaluated for potential use for federally led acquisitions in the near future. NNSA considers this reform implemented.

· The Use of Retired Annuitants team sent out a poll to NNSA’s M&O contractors regarding proposed changes to authorities for employing retired annuitants. The team stated that the survey results indicated a preference by most M&O contractors to keep their current systems rather than implement the changes envisioned through the original reform. Team members stated that the contractor at one site, Sandia National Laboratories, did make policy changes allowing annuitants to work more hours with less risk to their pension, but officials stated that these changes were underway prior to EMDI. NNSA considers this reform implemented.

· The Addressing Backlog of Telecommunications Security Reviews team told us it created a pilot program to train an NNSA employee to assist with the agency’s backlog of telecommunications security reviews, which team members said ensure that agency telecommunications equipment meets specific security standards. As the next stage of the pilot program, the team assigned the fully trained employee to the Sandia Field Office for 1 year in October 2023. In June 2024, the team told us it completed the pilot and reported the average review time was 3 business days, which met the team’s target of 10 business days or less. NNSA officials are evaluating the feasibility of implementing the concept at other sites and consider this reform implemented.

· The Improving the Concurrence Process team created a 6-month pilot program that allowed congressional reports to be signed by the NNSA Administrator without having to go through DOE review and raised the threshold for what requires concurrence from other NNSA offices with equity in the report, which officials told us is now the agency’s standard procedure. Officials stated that this streamlined process reduced the time between NNSA approval of reports for release to Congress and actual release to Congress by over 70% in fiscal year 2024 compared to fiscal year 2022. NNSA considers this reform implemented.

· The Improving Modernization Programs Efficiency Pilot team stated that its pilot consists of multiple efforts to improve NNSA’s nuclear weapons modernization processes. According to agency officials, senior leaders of NNSA’s Office of Defense Programs approved the consolidation of these modernization efforts into one reform because they believed there was significant overlap between them. The team stated that activities associated with the pilot generally fall into four major categories: (1) clarifying roles; (2) streamlining and standardizing requirements; (3) rebuilding trust; and (4) achieving speed, agility, and resilience.

In December 2023, NNSA provided us with documentation of two pilot programs. According to the documents provided, the team created a product realization team (PRT) pilot, which modified attendance policies to reduce federal participation in PRT technical reviews on three weapons modernization programs, the W80-4, W87-1, and W93 programs.[35] Additionally, the team said it created a pilot that required federal officials and M&O contractor representatives to negotiate certain new, annual milestones for the W80-4 and W87-1 programs with greater focus on specific program technical deliverables.[36] As of September 2024, NNSA officials stated that both the PRT pilot and the milestone pilot have been incorporated into current processes for weapons modernization programs as a regular standard of operation.

Officials also stated that four other projects have begun pilots and have timetables and deliverables through fiscal year 2026. These pilots include a change management pilot that aims to understand and approve changes to projects at the lowest possible levels of leadership; a clean sheet pilot that is investigating how NNSA can begin the production process at Pantex more quickly for certain types of programs; a schedule integration pilot that aims to develop an IT solution to integrate the schedules of various weapons programs; and a training pilot that aims to develop a training course on Federally Funded Research and Development Centers. However, as of September 2024, NNSA did not have a central plan or timeline for these activities.

Overall, this reform is considered ongoing. Because of its breadth and complexity, it is difficult to determine the extent to which reform activities adhere to the original conception of the reform.

· The Improve M&O Subcontracting Efficiency team told us it created a pilot program that established a middle category of subcontract reviews that no longer require full consent reviews with NNSA approval. Instead, some subcontracting actions now require only notification to NNSA. Actions $100 million or over are still subject to review. We found that this reform largely adhered to its original conception, and NNSA considers this reform implemented.

· The Waive DOE Project Order for Low-Risk Commercial-Like Construction team helped institutionalize a pilot program begun in 2019, which used commercial construction practices and environmental, safety, and health standards, rather than DOE’s Project Order requirements, for projects between the minor construction threshold and $50 million.[37] See figure 4 for an image of a facility built under the pilot. As part of this reform, NNSA issued a supplemental directive in September 2023 that codified the pilot’s streamlined project management practices for non-complex, non-nuclear construction projects between the minor construction threshold and $100 million.[38] We found that this element of the reform largely adhered to its original conception, and NNSA considers it implemented. This reform also initially pursued raising the minor construction threshold (up to $50 million or $100 million). Instead, NNSA officials told us that they advocated for Congress to amend the minor construction threshold to allow for inflation-based increases. As a result of congressional action, the minor construction threshold was raised from $25 million in 2021 to $34 million in February 2024.[39] NNSA also considers this element of the reform implemented.

Figure 4: Emergency Operations Center Built Under a Pilot Related to the Waive DOE Project Order for Low-Risk Commercial-Like Construction Reform

· The Integrated Strategic Priorities List team told us members reached out to representatives of NNSA field offices to determine their priorities for the fiscal year. The team then integrated these priorities with NNSA’s established mission priorities to create a single integrated strategic priorities list. The team believes that the integrated strategic priority list could be used to guide the allocation of NNSA resources and equipment in cases where projects have conflicting needs. We found that this reform largely adhered to its original conception, and NNSA considers this reform implemented. Officials have stated that the agency will continue to create a new integrated strategic priorities list for each fiscal year and to integrate development of the list with the budgeting and performance evaluation processes.

· The Increasing Rotations Between M&O and NNSA Employees team stated that the team is working to identify ways to improve the agency’s rotational programs and share information about them to increase opportunities for NNSA headquarters staff to work with field office and M&O workforces through rotations, details, or regular travel. NNSA officials stated that such programs are currently limited by high program costs but are important because they increase mutual understanding among the agency’s federal and contractor workforces. As of April 2024, NNSA officials stated that this reform effort is ongoing.

· The Improving Off Site Assignments team stated that it collected feedback from NNSA sites as part of its attempt to determine how the agency could increase employee participation in off-site assignment programs. NNSA officials stated that the length and relocation costs of the assignments can be a deterrent to potential participants, especially those who are early in their careers. As of April 2024, NNSA officials stated that this reform effort is ongoing, and that the team is working to revise NNSA policies and procedures governing M&O Off-Site Extended Duty Assignments.[40]

The Develop an Integrated Strategic Plan for Science, Technology, & Engineering team developed an integrated strategic plan for science, technology, and engineering, which NNSA approved in September 2024. NNSA considers this reform implemented.[41]

NNSA Does Not Have a Formal Continuous Improvement Governance Structure in Place to Evaluate the Effectiveness of EMDI Reforms or to Implement Future Reform Efforts

|

Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI) on Continuous Improvement PMI is a not-for-profit association that provides global standards for project, program, and portfolio management. These standards are generally recognized as leading practices and used worldwide by private companies, nonprofits, and others. PMI has also published guidance complementary to these foundational standards. For example, PMI has developed and published a set of continuous improvement practices that the association says need to be considered as part of continuous improvement efforts. One such practice is that agencies should “govern improvement.” PMI states that as part of continuous improvement, “there needs to be some way to monitor and report on, preferably in a lightweight and streamlined manner, the improvement.” Source: PMI, Inc. | GAO‑25‑106675 |

According to NNSA, the organizational structure that was in place initially to implement EMDI reforms gradually disbanded as EMDI implementation progressed, but implementation teams working on ongoing reforms continue their work and report directly to the office of the Associate Principal Deputy Administrator. As described above, the members of these implementation teams are performing this work in addition to their regular duties. Further, for reforms that NNSA considers implemented, officials told us that some activities will continue, including monitoring the reforms and making adjustments to them as needed. NNSA officials have also stated that the agency will pursue additional reform efforts after EMDI. For example, NNSA senior officials described EMDI in March 2023 as a starting point for the agency’s efforts to improve the speed and efficiency of the nuclear security enterprise and to improve employee recruitment and retention.

According to senior NNSA officials, the Office of the Associate Principal Deputy Administrator has taken on the role of overseeing reform efforts broadly. However, these officials also told us that this role has not been formalized as such in agency organizational descriptions of office functions and responsibilities. Further, these officials told us that they have not established processes for governing reform efforts, such as expectations for who is responsible for long-term monitoring of EMDI reforms or reporting on them, or for pursuing anticipated future continuous improvement efforts. According to senior NNSA officials, these actions have not yet been taken because the efforts are new and have been evolving, but they recognized the importance of moving in this direction.

According to the Project Management Institute, Inc.’s Continuous Improvement Practices, organizations should govern improvement by having a way to monitor and report on their improvement activities, preferably in a lightweight and streamlined manner. These monitoring efforts should include development of improvement metrics to measure improvement and whether the improvement is achieving its goals. Without defining how it will govern the work to implement ongoing EMDI reforms, monitor implemented EMDI reforms, and pursue continuous improvement, NNSA is less likely to be able to determine whether its reforms achieve desired goals. Additionally, NNSA may be challenged to maintain the continuity of EMDI reforms and continuous improvement efforts in cases of employee turnover and leadership changes if NNSA’s Office of the Associate Principal Deputy Administrator does not have a defined governance structure to carry out monitoring and reporting on EMDI reforms and continuous improvement efforts.

As of September 2024, NNSA has made at least three attempts to pursue continuous improvement efforts post-EMDI, none of which has moved into implementation, further demonstrating the importance of developing a governance approach. It also hired consultants to focus on federal workforce initiatives—a significant shift from the agency’s original EMDI efforts that were mainly focused on M&O contractors and the federal-contractor relationship.[42] Officials told us this contract has ended, but the agency plans to create a request for proposals to hire a consultant with expertise in organizational transformation to continue such efforts. Specifically, NNSA continuous improvement efforts have included the following:

Unlocking Latent Capacity: NNSA officials told us that the agency initially planned to implement an EMDI follow-on effort that they named “Unlocking Latent Capacity.” Officials subsequently told us that this title did not catch on among the agency’s workforce, and probably would have limited the initiative’s effectiveness.

EMDI 2.0: Because of the concerns above, NNSA developed a new initiative to replace Unlocking Latent Capacity. Senior officials referred to this second version of post-EMDI activities as “EMDI 2.0” in public remarks at a conference in February 2024. According to agency documentation, EMDI 2.0 involved reforms that were aimed at improving the agency’s communication, workforce and training, risk management, and systems and processes.

Senior officials told us that they hoped EMDI 2.0 would transform EMDI into a broader effort led mainly by the agency’s middle leadership. For example, a senior NNSA official stated in February 2024 that EMDI 2.0 would involve many small-scale initiatives and allow lower-level NNSA officials to look for ways to do their jobs better with the overall goal of reducing the agency’s aversion to risk. However, officials told us that due to the initiative’s association with the agency’s original EMDI efforts, NNSA employees perceived EMDI 2.0 as a top-down initiative that depended on guidance from senior leadership. As a result, EMDI 2.0 did not inspire the type of agencywide participation that senior leadership had intended to promote.

Continuous improvement: As of September 2024, officials told us that the agency had begun pursuing a yet unnamed continuous improvement effort. Without establishing how it will manage, monitor, and report on the status of those efforts, NNSA may be limited in its ability to determine whether EMDI reforms and continuous improvement are achieving their goals.

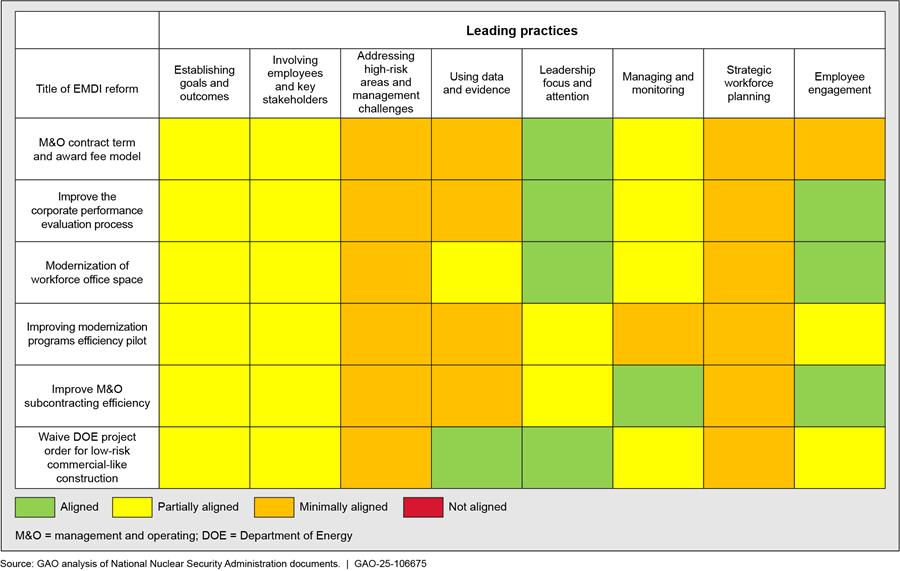

NNSA’s Implementation of EMDI Reforms Related to GAO High-Risk Areas Partially Aligned with Selected Leading Practices for Agency Reform

We found that NNSA’s implementation plans for the six high-risk EMDI reforms we reviewed partially aligned with selected leading practices for successfully achieving agency reform. We selected six out of 15 reforms for review that we identified as at high risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement. While we focused our analysis on the implementation plans and associated documentation for these six reforms, the leading practices are applicable to all 15 reforms. Our past work has shown that agency reforms are more likely to be successful in refocusing and enhancing agency missions and achieving efficiency and effectiveness if they followed these leading practices.[43]

EMDI reforms are relevant to several high-risk functions at NNSA and long-standing management challenges. For example, three of the six reforms we reviewed are about contracting practices, which are a key focus of the DOE Acquisition and Program Management high-risk area that has been on GAO’s High Risk List for over 3 decades. A fourth reform, the Improving Modernization Programs Efficiency Pilot, is also related to DOE Acquisition and Program Management. Nuclear weapons modernization programs, such as the W87-1 and W80-4, are among NNSA’s largest and most complex acquisition programs—each costing tens of billions of dollars—and are considered by NNSA and Congress to be major acquisitions. In addition, NNSA is simultaneously modernizing production infrastructure—the facilities and programs needed to modernize U.S nuclear weapons. Challenges with capital asset acquisitions—which include large construction projects—for this production infrastructure have also figured prominently in our reporting on this area of GAO’s High Risk List.[44]

We identified the high-risk reforms by assessing whether NNSA’s EMDI reform implementation plans (1) were related to areas that are at high risk for fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement, as we have described in our High-Risk Series; and (2) had actions focused on multiple sites. Six reforms met those two criteria. We then evaluated NNSA’s implementation plans for these six selected high-risk EMDI reforms against eight leading practices for agency reform.[45] Of the six reforms we selected, NNSA considers five to be implemented. The one ongoing reform is the Improving Modernization Programs Efficiency Pilot.[46] See figure 5 for the alignment of these high-risk reforms with the eight selected leading practices. In particular, NNSA’s plans were most closely aligned with the selected leading reform practices on leadership focus and attention.

Figure 5: Alignment of Selected Enhanced Mission Delivery Initiative (EMDI) Reforms with Leading Practices for Agency Reform

Note: We identified six EMDI reforms that (1) related to one of our high-risk areas and (2) had actions focused on multiple sites.

Establishing goals and outcomes. All six EMDI reforms we reviewed partially aligned with leading practices for establishing goals and outcomes in agency reform efforts. Our prior work shows that establishing a mission-driven strategy and identifying specific desired outcomes to guide that strategy are critical to developing reforms and achieving intended results.[47] For example, designing proposed reforms to achieve specific, identifiable goals encourages decisionmakers to reach a shared understanding of the purpose of the reforms. Further, agreement on specific goals can help decisionmakers determine what problems genuinely need to be fixed, how to balance differing objectives, and what steps need to be taken to create long-term gains.

We found that for several of the selected high-risk reforms, NNSA did not clearly articulate reform goals and how achieving those goals would achieve desired outcomes. EMDI implementation team charters often used EMDI report language verbatim; however, as noted above, many EMDI reform activities changed during implementation from the original recommendations in the report. For several reforms, NNSA’s implementation team charters either did not document the goals the reform was trying to achieve or were not updated to reflect changes to goals as reform efforts changed.

For example, a stated outcome of the reform Modernization of Workforce Office Space was improved employee recruitment and retention. However, NNSA did not provide documentation showing clear connections between the main goal and success indicator of the reform—increased square footage of new or improved office, light lab, and light industrial space—and the outcome of improved recruitment and retention. Further, the Waive DOE Project Order for Low-Risk Commercial-Like Construction reform implementation team listed different goals and success indicators to measure those goals in the reform’s charter, success indicator form, and other documents as the reform changed during implementation—making it unclear whether increases to the minor construction threshold remained a goal of the reform. Without documentation with clearly linked goals—especially as reform efforts change—it is difficult to align the results of a program’s products and services with how well or if the reform has been executed.

Additionally, EMDI reform implementation plans did not always ensure that goals were clearly linked to outcomes. For example, NNSA’s charter for its Improving Modernization Programs Efficiency Pilot reforms includes several efficiency related goals, such as improvement in efficiency of requirements and procedures and increased efficiency in mission execution. However, the outcomes and performance measures in NNSA’s success indicator forms were “adherence to pilot rules” and “effectiveness of pilot rules.” These were to be measured through a qualitative survey of participants, not through explicit measures of efficiency. The success indicator forms and implementation memo also did not include plans for collecting data on improved efficiency. NNSA officials stated that the team is exploring appropriate metrics to measure the effectiveness of the ongoing pilots.

Without the establishment of clear goals and outcomes, reforms may not ultimately address the issues they set out to address. Additionally, without clear goals and associated outcomes, NNSA may not be able to measure whether reforms are achieving the desired result. Further, the lack of clear goals and outcomes will make mandated congressional reporting on whether all EMDI reforms are achieving desired results challenging.[48] This is applicable to all reforms—implemented or ongoing, high risk or not—that have not established clear goals and outcomes.