AMPHIBIOUS WARFARE FLEET

Navy Needs to Complete Key

Efforts to Better Ensure Ships Are Available for Marines

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106728. For more information, contact Shelby S. Oakley at (202) 512-4841 or oakleys@gao.gov and Diana Maurer at (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106728, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

Navy Needs to Complete Key Efforts to Better Ensure Ships Are Available for Marines

Why GAO Did This Study

The Navy maintains a fleet of large amphibious warfare ships that are used primarily for Marine Corps missions, such as amphibious assault and humanitarian response. There are currently 32 amphibious warfare ships in this fleet, one more than the minimum the Navy is statutorily required to maintain.

House Report 117-397 includes a provision for GAO to review plans for the amphibious warfare fleet. GAO’s report examines the extent to which (1) the Navy and Marine Corps are addressing challenges with fleet availability; (2) the Navy is addressing maintenance challenges; and (3) the Navy is positioned to meet its fleet size requirements into the future.

GAO reviewed Navy and Marine Corps documentation and interviewed officials responsible for overseeing fleet availability, maintenance, and new ship acquisition plans. GAO also visited six ships and spoke with officers and crew about maintenance issues.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 4 recommendations, including that the Navy use metrics to define amphibious ship availability goals, and updates its policy to clarify that it should not cancel maintenance when divesting ships before completing the waiver process. The Navy concurred with 3 of the 4 recommendations. The Navy partially concurred with updating its policy but noted actions it will take to address the recommendation. GAO maintains that documenting these actions is needed.

What GAO Found

Amphibious warfare ships are critical for Marine Corps missions, but the Navy has struggled to ensure they are available for operations and training. In some cases, ships in the amphibious fleet have not been available for years at a time. The Navy and Marine Corps are working to agree on a ship availability goal but have yet to complete a metrics-based analysis to support such a goal. Until the Navy completes this analysis, it risks jeopardizing its ability to align amphibious ship schedules with the Marine Corps units that deploy on them.

As of March 2024, half of the amphibious fleet is in poor condition and these ships are not on track to meet their expected service lives.

GAO identified factors that contributed to the fleet’s poor condition and reduced its availability for Marine Corps’ operations and training. For example, the Navy faces challenges with spare parts, reliability of ship systems, and canceled maintenance. GAO found that the Navy canceled maintenance for aging amphibious ships it planned to divest before completing the required waiver process. Navy officials said they no longer plan to cancel maintenance prior to completing the process, but the Navy has yet to update its maintenance policy to reflect that decision. Updating the policy would help ensure ships the Navy plans to divest do not miss maintenance if Congress restricts funds for divestment.

The Navy is likely to face difficulties meeting a statutory requirement to have at least 31 amphibious ships in the future given the age of many ships and other factors. The Navy is considering extending the service life for some ships to meet the 31-ship requirement. However, these efforts will require up to $1 billion per ship, according to the Navy, with six ships needing service life extensions in the next 3 decades amid rising ship construction costs and maintenance backlogs.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ARG |

Amphibious Ready Group |

|

MEU |

Marine Expeditionary Unit |

|

NAVSEA |

Naval Sea Systems Command |

|

OPNAV |

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations |

|

RMC |

Regional Maintenance Center |

|

TYCOM |

type commands |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 3, 2024

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Navy maintains a fleet of large amphibious warfare ships that are critical for Marine Corps missions, such as amphibious assault, emergency evacuation, and humanitarian response, among many others. In recent years, the Navy repeatedly proposed reducing the size of the amphibious fleet below the Marine Corps’ stated requirements. In response, Congress added provisions to the National Defense Authorization Acts for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 requiring the Navy to maintain a force of 31 operational amphibious warfare ships and to provide semiannual briefings to Congress on the status of these ships, respectively.[1]

The Navy currently has 32 amphibious warfare ships in its fleet, which is consistent with statutory requirements. However, despite the current fleet size, maintenance and sustainment challenges have beleaguered fleet availability in recent years. The Navy refers to the ability of a ship to conduct training or operations as ship availability. We have previously reported on Navy-wide maintenance challenges and sustainment issues affecting availability of amphibious warfare ships, including substantial amounts of deferred and delayed maintenance.[2]

House Report 117-397, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, includes a provision for us to review the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ plans for the amphibious warfare fleet. Our report examines the extent to which (1) the Navy and Marine Corps are working to address amphibious fleet availability for operations and training; (2) the Navy faces maintenance and sustainment challenges affecting the amphibious warfare fleet and is working to address them; and (3) the Navy is positioned to meet statutory fleet size requirements into the future.

To assess fleet availability, we analyzed Navy and Marine Corps documentation, spoke with Navy and Marine Corps officials, examined Navy and Marine Corps operational readiness assessments, and reviewed Navy and Marine Corps efforts to reach consensus. To determine the extent of ship maintenance and sustainment challenges, we assessed the material condition of the amphibious fleet and evaluated the Navy’s response to known challenges and how the Navy manages major maintenance periods. We visited six amphibious warships at Naval Station Norfolk and Naval Base San Diego to see, firsthand, maintenance issues affecting amphibious warfare ships. To determine how the Navy is positioned to meet statutory fleet size requirements into the future, we reviewed initial plans for these efforts, identified special acquisition authorities, and assessed the Navy’s use of those authorities. Appendix II provides a more detailed discussion of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to December 2024, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

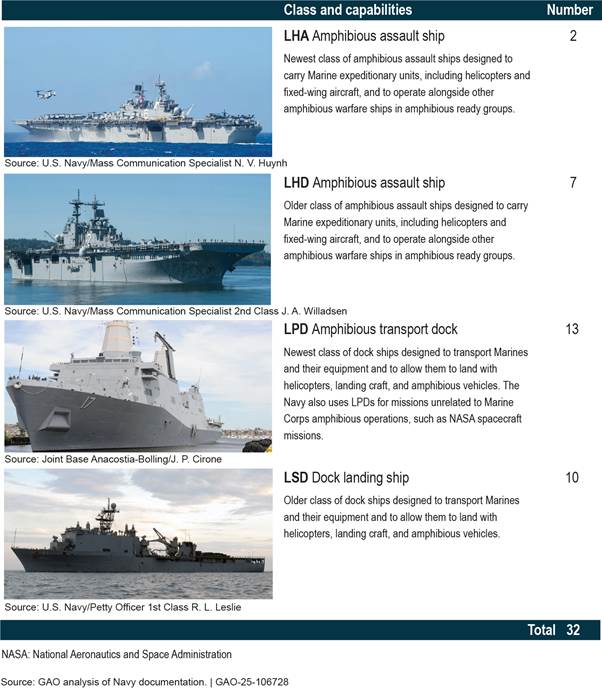

The Navy’s amphibious warfare fleet is composed of amphibious assault ships (LHD/LHA classes) and dock landing ships and amphibious transport docks (LSD/LPD classes) that transport and deliver Marines and their equipment, including landing craft and aircraft. While these ships are primarily used for Marine Corps missions, the Navy also uses its amphibious ships to conduct missions without the Marines, such as retrieval of National Aeronautics and Space Administration spacecraft. Figure 1 provides details on the roles and capabilities of these ships.

Note: An Amphibious Ready Group consists of a minimum of three amphibious warships, comprised of at least one amphibious assault ship, one amphibious transport dock, and one dock landing ship. According to the Marine Corps, a Marine Expeditionary Unit is a task force comprised of ground, aviation, and logistics combat elements.[3]

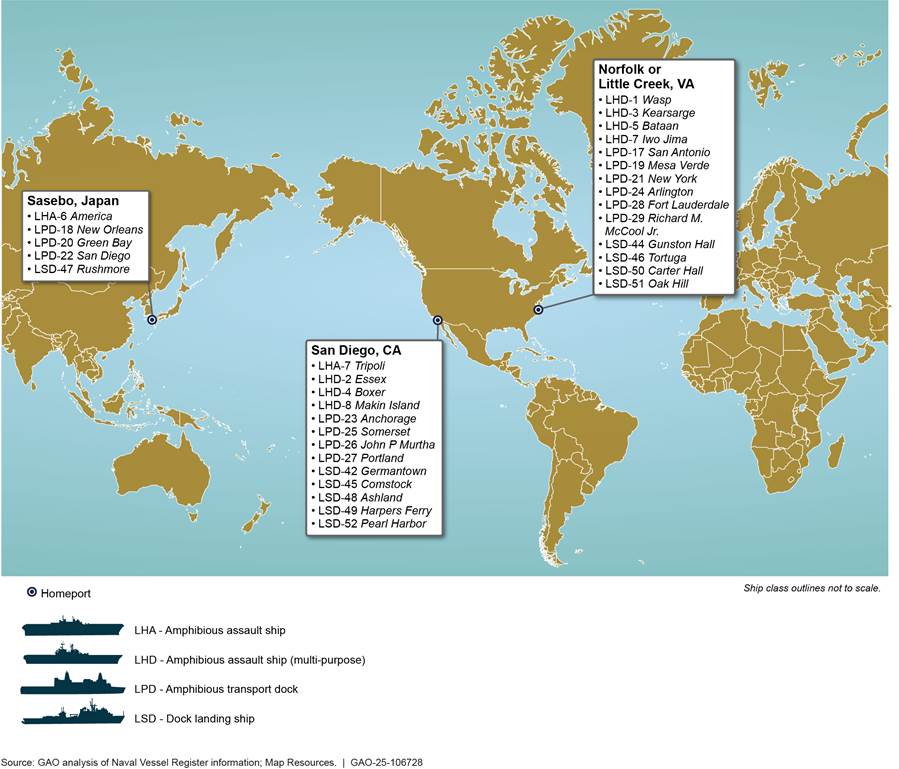

Amphibious Fleet Home Ports

The amphibious warfare fleet is divided between three home port locations: Norfolk or Little Creek, VA; San Diego, CA; and Sasebo, Japan. Figure 2 shows the homeport location of each of the 32 amphibious ships.

Naval and Marine Corps Forces Involved in Amphibious Operations

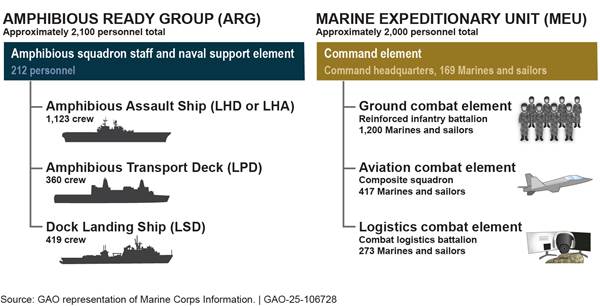

An amphibious operation is a military operation launched from the sea by an amphibious force embarked in ships or craft. This operation has the primary purpose of introducing a landing force ashore to accomplish an assigned mission. An amphibious force is comprised of (1) an amphibious task force and (2) a landing force together with other forces, such as aviation units, that are trained, organized, and equipped for amphibious operations.

The amphibious task force is typically a group of three Navy amphibious ships, most frequently deployed together as an Amphibious Ready Group. The landing force is a Marine Air-Ground Task Force—which includes certain elements, such as command, aviation, ground, and logistics—embarked aboard the Navy amphibious ships. A Marine Expeditionary Unit is the most commonly deployed Marine Air-Ground Task Force. Figure 3 illustrates the military assets that create an Amphibious Ready Group and a Marine Expeditionary Unit.

Navy Ship Maintenance

The level of complexity of ship repair, maintenance, and modernization can affect the length of a maintenance period. These periods can range from 6 months to about 3 years for more complex and involved maintenance and modernization. Privately owned shipyards perform depot-level maintenance for the amphibious fleet. These maintenance periods can include major repair, overhaul, or the complete rebuilding of systems needed for ships to reach their expected service lives. They also involve complex structural (hull), mechanical, and electrical repairs. Depot maintenance periods can also include ship overhaul efforts that involve major modernization work to ensure ships remain relevant in the warfare environment. The type of work—maintenance or modernization—is identified through the type of funding the Navy uses.[4] The Navy generally schedules depot maintenance periods every 2 to 3 years for surface ships. Ships in depot-level maintenance are not available for missions.

Intermediate maintenance periods occur between depot maintenance periods and have a higher frequency and much shorter duration. The Navy typically schedules 6-week intermediate maintenance periods each quarter a surface ship is not deployed. Because the Navy schedules intermediate maintenance periods more frequently and for much shorter durations, maintenance providers tend to complete fewer and less complex jobs during these maintenance periods.

The Navy also considers intermediate maintenance periods’ scheduling and duration to be more flexible than depot maintenance periods. According to Navy officials, the Navy considers a ship undergoing an intermediate maintenance period to be capable of stopping maintenance work and getting underway within 4 days (96 hours) to perform a mission.[5] Because of this, ships in an intermediate maintenance period can be considered available for missions within 4 days.

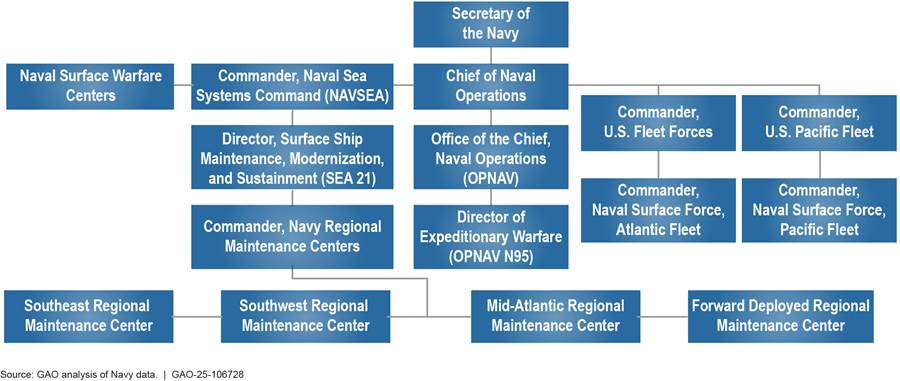

Several Navy commands have responsibilities for sustainment of the Navy’s ships:

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV). OPNAV is responsible to the Secretary of the Navy for the command, utilization of resources, and operating efficiency of Navy forces and of the Navy’s support activities. For example, OPNAV identifies the sustainment, maintenance, and support funding needed to meet Navy objectives related to equipping and ensuring the operational readiness of forces. The Board of Inspection and Survey, an independent organization that conducts material inspections of all Navy ships, reports to the Chief of Naval Operations and the Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command.

Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA). NAVSEA is responsible for managing critical modernization efforts and overseeing maintenance, among other things. Specifically, the Regional Maintenance Centers (RMC) within NAVSEA, which are co-located with the Navy’s ports, are tasked with executing and overseeing maintenance operations. Additionally, NAVSEA’s Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program is tasked with providing centralized surface ship life-cycle maintenance engineering, class maintenance and modernization planning, and management of maintenance strategies.

Naval Surface Warfare Centers. The Naval Surface Warfare Centers are responsible for installing equipment from other Navy program offices, such as networks, radars, and communication systems, as part of ship modernization efforts. We refer to the contractor teams that perform such work as modernization teams.

Type Commands (TYCOM). The Navy’s TYCOMs for the surface fleet— Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet; and Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet—are responsible for ship-crew maintenance, training, and the readiness of the ships assigned to each fleet.[6] The TYCOMs have a critical role developing and updating the Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual, which establishes a unified set of maintenance requirements. Figure 4 shows the general reporting relationships between different organizations tasked with Navy ship maintenance.

Navy and Marine Corps Disagree on Required Number of Available Ships to Conduct Operations and Training

Ships within the amphibious warfare fleet are sometimes unavailable for years at a time and the Navy has experienced significant schedule disruptions. In recent years, the Navy and Marine Corps have disagreed on the number of ships that should be available at any given time to conduct operations and training. The services have established an analytical process to further develop ship availability definitions and targets, but the definitions may require further refinement. Additionally, the process does not have a time frame for completion or implementation, and risks not resulting in a specific number of ships that the Navy needs to make available to conduct training and operations at any given time.

Insufficient Amphibious Warfare Ship Availability Hinders Marine Corps Operations and Training

Maintaining the statutorily-required fleet size of 31 ships does not indicate the capability of those ships to deploy or conduct training. In some cases, ships within the amphibious warfare fleet have not been available to support Marine Corps operations and training for years at a time.

Marine Corps documentation shows that, between 2011 and 2020, amphibious warfare ships were only available for operational tasking 46 percent of the time even though the Navy’s operational schedule—referred to as the Optimized Fleet Response Plan—notionally expects these ships to be available for operational tasking 50 percent of the time.[7]

At least two Amphibious Ready Groups/Marine Expeditionary Units experienced operational challenges in 2024. These included delayed deployments and missed exercises due to lack of available ships, according to Navy documentation. For example, from a training perspective, Marine Corps officials from First Marine Expeditionary Force stated that a lack of available amphibious assault ships makes it difficult to train Marine Corps aviators who must maintain certifications by landing on amphibious ships.

|

USS Tortuga (LSD 46) The Navy counts the USS Tortuga (LSD 46) as part of the 32-ship amphibious fleet inventory. However, as of June 2024, the ship had not deployed since 2013. Since that time, the ship experienced five separate maintenance and modernization periods. According to Navy officials, work associated with the ship’s major modernization effort remains incomplete more than 6 years after the maintenance period originally began. Navy documentation on root causes for Tortuga maintenance issues over the past 9 years described the modernization effort as consistently the lowest priority for the service. Source: GAO analysis of Navy documentation. | GAO‑25‑106728 |

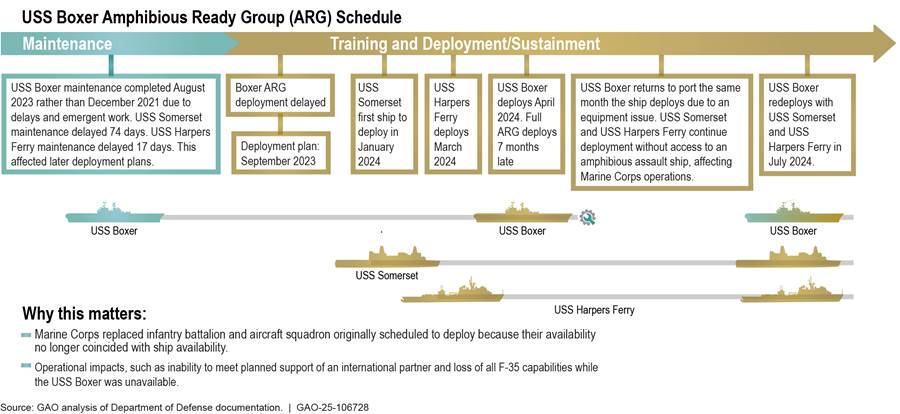

The Boxer Amphibious Ready Group. This group—comprised of the USS Boxer, USS Somerset, and USS Harpers Ferry—planned to deploy in September 2023. However, all three ships experienced maintenance delays and each ship individually deployed later than planned. In particular, the USS Boxer was not available and ready to deploy until April 2024. Days into its transit to the amphibious ready group, the USS Boxer experienced an equipment issue with its rudder and was forced to return to port. The ship was unable to resume its deployment until July 2024—or 10 months later than planned. During the time that the USS Boxer was unavailable, the Marine Corps was unable to deploy the full 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit and lacked the capabilities provided by F-35 fighter aircraft. Figure 5 shows a timeline of the USS Boxer’s unavailability and details how the ship’s unavailability affected the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ plans for the ship, such as missed international training exercises.

The America Amphibious Ready Group. This group was unable to conduct a patrol as a full group in 2024 due to a lack of available ships. Specifically, the Navy only had one LHA and one LPD available rather than the three ships required to compose a full amphibious ready group. As a result, the Navy and Marine Corps missed exercises and there was a presence gap in the group’s assigned area of responsibility.

Navy and Marine Corps Have Yet to Agree on Ship Availability Goals

According to Navy and Marine Corps officials, the services have yet to agree on how many ships within the amphibious fleet should be available for operations and training at any given time. For the past several years, the Navy and Marine Corps have not agreed on basic amphibious warfare fleet requirements, such as the size and availability of the fleet. Congress has subsequently enacted statutes that provide the Marine Corps with more influence in establishing requirements for the amphibious warfare fleet. For more information regarding these statutes, see appendix I.

In February 2024, Navy and Marine Corps leadership established a memo that requires the services to conduct an analytical process resulting in a plan that meets two general goals related to (1) ship availability definitions and (2) ship availability concerns.[8]

Ship availability definitions. The first goal is intended to define what constitutes an available ship. In June 2024, the Navy and Marine Corps completed this goal by agreeing on a common understanding of what constitutes an available ship. Table 1 provides an overview of how the Navy and Marine Corps define amphibious warfare ship availability and the categories associated with those measures.

|

Available Amphibious Warfare Ship |

|

|

Category |

Definition summary |

|

Fully mission capable |

Ship can support the full range of naval operations. Ship is capable of fully integrating within an Amphibious Ready Group/Marine Expeditionary Unit or larger formation. |

|

Mission capable |

Ship has completed basic training but may not have completed advanced or integrated training. Ship may not be considered fully mission capable because it is experiencing one or more temporary resource restriction(s) related to training, manning, or material. |

|

Partially mission capable |

Ship has not completed basic training but is otherwise available. Ship does not have any critical limiting restrictions, such as a category 4 casualty report, that would limit the Marine Corps’ ability to train or conduct events on the ship.a |

|

Unavailable Amphibious Warfare Ship |

|

|

Category |

Ship meets at least one of these criteria: |

|

Not mission capable |

Ship has a temporary critical limiting restriction that prevents the Marine Corps from conducting training or operations on the ship. Ship is in a maintenance phase. Ship is conducting post-delivery test and trials. Ship is preparing to decommission. |

Source: Navy and Marine Corps documentation. | GAO‑25‑106728

aThe fleet writes casualty reports when there are significant equipment failures that contribute to the ship’s inability to perform its missions. There are three categories of casualty reports (2, 3, and 4), with category 4 being the most severe. In GAO‑20‑2, GAO found that the Navy’s categorization of casualty reports tends to be subjective or based on other factors than the ship’s availability to perform missions.

Although the services took an initial step to define ship availability, we found these definitions are not tied to specific and measurable terms in some cases. For example, the definitions in the memo note that ships in a major maintenance phase are not mission capable, but they do not specify whether this includes all types of maintenance phases (i.e., intermediate level maintenance). This may limit Department of the Navy leadership or congressional awareness of a ship’s availability.

Specifically, the effect of extended or undefined intermediate maintenance on a ship’s availability may not be captured by the Navy’s definitions. As previously noted, the Navy considers a ship undergoing an intermediate maintenance period to be capable of stopping maintenance work and getting underway within 4 days (96 hours) to perform a mission. However, when we toured the USS Germantown in October 2023, officials told us that the ship could not deploy within 96 hours due to the extensive amount of maintenance in its ongoing intermediate maintenance period. This matched our observation of the ship’s condition at that time. Further, officials on the USS Germantown described upcoming maintenance for the ship as a “super continuous maintenance availability,” which is not a term defined in the Navy’s maintenance policy.[9]

Further, while the Navy identifies one example of a metric that may be used to measure ship availability—category four casualty reports—the definitions do not otherwise identify metrics. For example, the Navy tracks other metrics, such as redlines, to determine the minimum communications, damage control, engineering, navigation, and seamanship equipment required to safely get or remain underway for each ship class. However, the definitions make no mention of redlines or other measurable metrics tracked by the Navy.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should define objectives in specific and measurable terms.[10] Until the Navy and Marine Corps refine their ship availability definitions to incorporate specific and measurable terms, the services are likely to encounter situations where a ship’s availability is unclear to Department of the Navy leadership or Congress.

Ship availability concerns. The second goal is to generally address concerns related to amphibious warfare ship availability. Completion of this goal should result in a plan that partially addresses challenges the Navy and Marine Corps face related to ship availability.

While the February 2024 memo has a time frame for providing an initial report and accompanying briefings to Department of Navy leadership, it does not have a time frame for completing and implementing the final plan required by the second goal. Specifically, at the end of the memo, the Navy and Marine Corps agreed to submit an initial report by April 2024 with monthly briefings following the initial report until completion of a final plan. However, as of July 2024, Navy officials told us that they and the Marine Corps had yet to complete their initial report.

Additionally, the memo does not clearly specify that the final plan should identify a specific number of ships that need to be available over the near- and long-term future to meet Marine Corps and statutory requirements.[11] According to officials from Headquarters Marine Corps, Combat Development & Integration, a preliminary Marine Corps assessment conducted prior to the memo’s release indicated that a higher number of amphibious warfare ships should be available for operations or training compared to the Navy’s initial assessment.[12] Given previous disagreements between the services regarding requirements for the amphibious fleet—such as overall fleet size—and constrained funding, identifying a specific number of ships that need to be available over the near- and long-term future is critical to aid in planning maintenance and meeting operational needs.

The National Defense Authorization Act of 2024 requires the Secretary of the Navy to prepare a plan to schedule maintenance and repair in a manner that provides for the continuous operation of a total of three Amphibious Ready Groups (i.e., three amphibious assault ships and six dock ships) and Marine Expeditionary Units as soon as practicable.[13] Further, according to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should obtain relevant data from reliable sources in a timely manner and process those data into quality information to make informed decisions and evaluate performance in achieving key objectives.[14] Without time frames for the Navy and Marine Corps to complete their ongoing analysis, the Secretary of the Navy and Commandant of the Marine Corps risk lacking timely data required to make informed decisions about scheduling Marine Expeditionary Units to align with Amphibious Ready Group availability. Additionally, until the services identify a specific number of ships that should be available for operations and training at all times, the Navy is likely to lack the required information to plan ship maintenance and evaluate its performance in completing maintenance on time to meet operational needs.

Navy Has Made Limited Progress Addressing Amphibious Fleet Condition and Maintenance Issues

Half of the Navy’s amphibious ships are in poor condition and amphibious ship maintenance often takes longer than expected. These factors have led to ship availability rates that are lower than required. While the Navy has identified key issues that affect the availability of amphibious ships, it has made little progress in addressing these challenges.

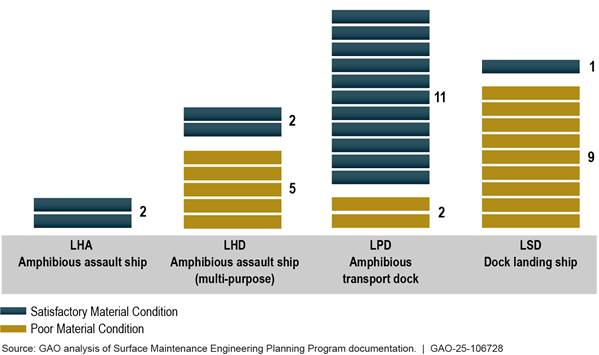

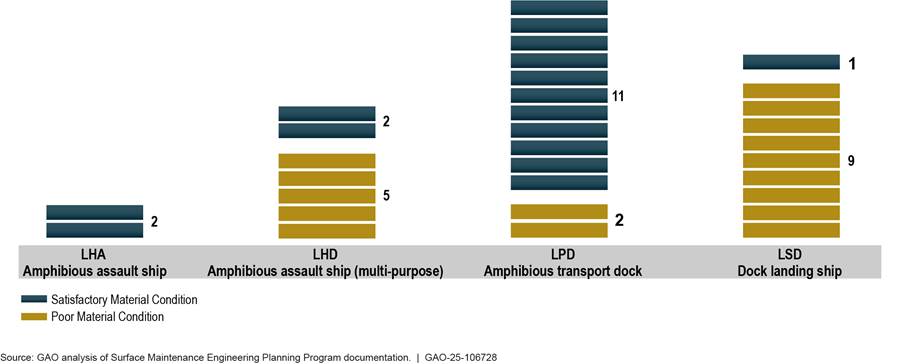

Amphibious Fleet Is in Poor Condition

One key reason that the Navy is not meetings its ship availability targets is the poor condition of many amphibious warfare ships. As of March 2024, the Navy’s Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program assessed that 16 of the Navy’s 32 amphibious warfare ships are in unsatisfactory condition.[15] These ships are generally the oldest ships in the amphibious fleet. Being rated as unsatisfactory means that these ships are not currently on track to meet their expected service lives because of the number of deferred mandatory maintenance tasks, the condition of essential systems, or the number of structural repair tasks required.[16] Figure 6 shows a breakdown of ship condition by class.

Note: The Navy’s assessment did not include two LPD class ships it took delivery of in 2022 and 2024. We included them in this graphic as the Navy considers new ships to be in satisfactory material condition until they are evaluated as part of their first major maintenance period. This has not yet occurred for either ship.

Additionally, according to a Navy Board of Inspection and Survey report from March 2023, amphibious ships have historically scored lower than the overall fleet on material inspections.[17] Similarly, in January 2023, we reported that LHD class ships experienced the largest increase in casualty reports (reports of events that impair a ship’s ability to conduct a primary mission) among 10 ship classes from fiscal years 2011 through 2021.[18]

A contributing factor to the fleet’s poor condition is the Navy’s decision to cancel maintenance for a significant portion of the fleet. As recently as 2022, the Navy planned to divest all 10 LSD ships, which is almost a third of the amphibious fleet. Divestment means to retire ships before the end of their expected service lives.[19] In doing so, the Navy canceled all major maintenance periods for these ships, which included maintenance on systems such as the ships’ diesel engines. The Navy canceled these critical maintenance periods prior to certification to the congressional defense committees of its divestment plans and completing the waiver process.[20]

When, in December 2022, Congress prohibited the expenditure of appropriations to implement the LSD divestment plans for a selected number of these ships, the Navy had to continue operating the ships— even though it had already canceled the required maintenance periods.[21] As a result, these LSD class ships fell into further disrepair, which compounded the amount of work the Navy needs to complete in future maintenance periods. In 2023, the Navy found that seven of 13 incidents that affected amphibious fleet readiness were linked to LSD diesel engine problems resulting from deferred maintenance.

Officials from Naval Sea Systems Command stated that canceling maintenance for LSD class ships is a major contributor to a reduction in their condition. Further, Navy documentation identified other effects. Canceling these maintenance plans:

· created a backlog of maintenance work that is not realistic for the Navy to complete;

· reduced availability of systems—such as the ships’ ballast systems—needed to support the warfighter;

· reduced visibility into the status of mandatory technical requirements—such as repairs to the ships’ propulsion systems and hull structures—that need to be corrected in maintenance periods; and

· created lag time between canceling and reactivating maintenance periods for the newest LSD class ships.

In May 2022, we found that a ship’s accumulated deferred maintenance can make it an increasingly attractive candidate for divesting before reaching its intended service life.[22] We reported that choosing to defer maintenance can also result in divesting ships earlier than planned. It also reduces the chances that the Navy can extend ships beyond their service lives if new ships are not built according to schedule. For example, we found the Navy divested the USS Fort McHenry (LSD 43) 6 years before it reached its expected end of service life. Navy maintenance officials described the USS Fort McHenry (LSD 43) as a poorly maintained ship that had accumulated a significant backlog (i.e., approximately $146 million) of deferred maintenance at the time of divestment.

According to the Navy’s operational schedule policy, completion of maintenance is necessary for a ship to meet its expected service life.[23] Recent Navy policy states that depot maintenance periods generally should not be scheduled in the year prior to a ship’s decommissioning.[24] The policy does not provide an exception for maintenance periods prior to divestment. However, as discussed earlier, statute limits the Navy’s ability to divest a battle force ship prior to its expected service life without completing a waiver process involving submitting a certification to the congressional defense committees.[25] While Navy officials stated that they no longer plan to cancel maintenance prior to completion of the waiver process, they have yet to document this intent in policy.

The Navy’s maintenance policy outlines requirements associated with revising planned major maintenance schedules for the fleet’s surface ships.[26] However, the requirements do not address the scenario where the Navy proposes, but Congress restricts funding for, an amphibious ship for divestment. The Navy would better position amphibious warfare ships to meet their expected service lives if it updates its maintenance policy to reflect that maintenance should not be canceled on ships proposed for divestment prior to completing the waiver process.

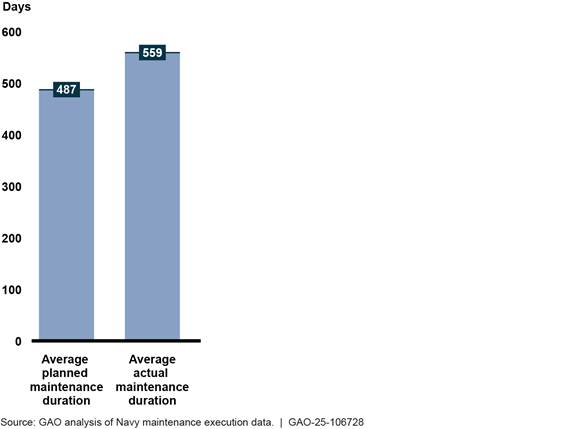

Amphibious Ship Maintenance Often Takes Longer than Expected

Another key reason the Navy is not meeting its ship

availability goals is that it has generally failed to complete amphibious

warfare ship maintenance in accordance with its planned maintenance schedules.

For amphibious warfare ships that began depot maintenance periods in fiscal

years 2020-2022, the Navy only completed three of 14 of those periods on

schedule.[27]

The remaining 11 maintenance periods that the Navy did not complete on schedule

resulted in more than 1,200 days of cumulative delays. Maintenance delays can

result in cascading delays to training and, ultimately, deployment.

Additionally, in total, the maintenance periods cost $400 million more than the

original contract value for the efforts. Figure 7 shows the average duration of

depot maintenance periods for amphibious ships in recent years.

|

USS Boxer Maintenance Delays Prior to a brief deployment in early 2024 that was cut short by a rudder issue, the USS Boxer (LHD 4) had experienced continuous maintenance delays since 2020. The ship suffered various maintenance problems, including multiple failures of the forced draft blowers—components that are critical to the ship’s propulsion system. During a maintenance period that began in 2020, a contractor overhauled the forced draft blowers but they failed during sea trials. The Navy overhauled the blowers again in August 2022, only to have them fail again in November of that year. Following these issues, the USS Boxer most recently deployed in April 2024. While officials said the maintenance period was nominally completed “on-time,” the Navy shifted about 6-month’s worth of major structural and other work that was supposed to be completed in the depot maintenance period to the intermediate maintenance period, which delayed deployment from September 2023. Source: GAO analysis of Navy documentation. | GAO‑25‑106728 |

Figure 7: Average Duration of Completed Depot Maintenance Periods that Began in Fiscal Years 2020-2022 for Amphibious Warfare Ships

Note: The figure does not reflect amphibious warship depot maintenance periods that began in fiscal year 2023 because those periods were ongoing at the time of GAO’s review.

Further, Marine Corps documentation indicates that amphibious warfare ships have generally not met the Navy’s planned maintenance schedules dating back to 2010. Specifically, Marine Corps documentation states that, from 2010-2021, the Navy extended 71 percent of amphibious warfare ship depot maintenance beyond its original planned end date. This cumulatively resulted in 28.5 years of lost training and deployment time for those ships and their associated Marines.

The Navy’s operational schedule policy states that adhering to planned maintenance schedules is critical to the Navy’s ability to generate forces.[28] Not adhering to maintenance schedules has multiple effects. For example, it impacts the ship experiencing the delay and the Navy and Marine Corps units that deploy with it. In November 2022, we found that maintenance delays affected the Navy’s ability to generate carrier strike groups and left individual ships unavailable for training and operations.[29] To address these findings, we recommended in 2022 that the Navy clearly identify measures of success and performance in its process for producing ready and available ships to include measures related to maintenance timeliness and adequacy. As of September 2024, this recommendation remains open.

Navy Has Made Little Progress Addressing Maintenance Challenges

The Navy has identified key issues with amphibious fleet maintenance affecting ship availability, but it has made little progress in addressing these challenges.

The Navy has two amphibious readiness reviews to study maintenance of the fleet:

· The first review was conducted under the direction of the Commander, Naval Surface Forces and was completed in May 2023. This review identified four root causes accounting for 80 percent of the amphibious ship maintenance issues affecting readiness.[30] The four root causes were: (1) challenges with parts obsolescence and supply, (2) poor equipment design, (3) poor contractor work quality, and (4) deferred maintenance.

· The second review began in April 2024 at the Chief of Naval Operation’s direction and is not yet complete.

To address maintenance issues, the May 2023 review made recommendations across five areas in which the Navy should make long-term improvements:

1. sparing and orphaned parts—managing supply for spare and orphaned parts;[31]

2. configuration management—keeping consistency of parts and systems across ships and better documenting changes;

|

GAO Work on Key Areas for Amphibious Fleet Improvement Sparing and Orphaned Parts: (GAO‑23‑106440) In January 2023, we identified diminishing manufacturing sources and material shortages as common issues for surface ship maintenance. Configuration Management: (GAO‑20‑2) In March 2020, we reported challenges with inconsistent ship equipment configuration, such as using different versions of the same equipment on different ships. The different versions can require unique spare parts and maintenance expertise, resulting in added complexity for maintaining this equipment across the fleet. Knuckle Boom Crane and Caley Davit Sustainment: (GAO-20-2) In March 2020, we reported that LPD ships are often considered operationally available even though their knuckle boom cranes and davit systems work less than 30 percent of the time. These systems are critical to many of the LPD’s missions. Quality Control and Assurance: We have ongoing work on the cruiser class surface ships’ challenges with contractor oversight and performance related to quality control and assurance. We expect to issue this report in the winter of 2024. Balancing Operational and Maintenance Needs: (GAO‑23‑105294SU) In November 2022, we identified challenges with adherence to maintenance and training schedules that disrupt planned fleet operations and ship operational schedules. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106728 |

3. knuckle boom crane and Caley davit sustainment;[32]

4. quality control and assurance; and

5. balancing operational and maintenance needs—options to conduct additional maintenance while maintaining ship availability requirements.

Consistent with the Navy’s review, we also previously identified or have ongoing work relating to all five areas the Navy identified for improvement.

As of July 2024, we found the Navy had made little progress addressing the identified improvements that Commander, Naval Surface Forces recommended in its May 2023 review. For example, in a February 2024 update, the Navy indicated that the actions taken to date to address quality control and assurance issues only included actions related to identifying performance issues on propulsion systems. The actions to date did not address other problem areas that both the May 2023 review and our prior work have found related to contractor performance, such as addressing oversight or quality assurance improvements.

Additionally, in the same February 2024 update, the Navy indicated that the progress made to date to address sparing and orphaned parts improvements included a few efforts, such as establishing working group meetings. The actions to date did not include resource deficiencies being presented to leadership or identify budget plans. The Navy considers all five of these improvements to be ongoing.

As noted above, in April 2024, following recent maintenance incidents impacting operational availability of three amphibious ships, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations released a memo initiating another amphibious readiness review. This review, among other things, directed key Navy organizations to establish recommendations for solutions to persistent maintenance challenges.[33] Like the May 2023 review, the April 2024 review directed the fleet to assess maintenance period planning, contractor work, and government oversight and accountability. In the memo directing the review, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations called out key areas that we also found are degrading amphibious fleet maintenance.

According to senior Navy officials involved with the report, they had not finalized it as of the end of October 2024. However, they said it identified two primary factors contributing to the poor amphibious warfare ship maintenance performance and subsequent availability delays. These two issues relate to maintenance planning and oversight. We previously reported on the Navy’s struggles with both issues.[34] For this report, we found evidence of the persistent maintenance challenges and root causes highlighted in the Navy’s May 2023 amphibious readiness review during all our visits to ships.[35] Senior officials also discussed their preliminary findings from the April 2024 review, which align with issues we observed during our visits. We discuss examples from three of these visits below.

USS Wasp (LHD 1). The oldest LHD class ship, the Wasp, is facing challenges with parts obsolescence and supply. According to ship and maintenance officials, as one of the last non-nuclear steam propulsion ships in the Navy, the LHD class faces diminishing sources for the manufacture of parts for its steam systems.

Non-nuclear steam propulsion repair is facing a significant loss of repair expertise as an increasingly obsolete trade. Officials from the Commander, Navy Regional Maintenance Center told us that the Navy is soliciting input from industry regarding the best approach to mitigate this challenge. According to Navy officials, this challenge poses immediate concern for the Navy to address because it is examining the possibility of extending the service lives of the remaining in-service LHD ships beyond their expected 40 years to maintain required fleet size. However, officials stated that replacing steam propulsion plants is not currently a part of this effort, so the Navy will need to continue maintaining them on LHD ships.

According to Navy officials, the service is taking some measures to address obsolescence issues with the machinery control systems on some LHD and LHA class ships beginning fiscal year 2025. We discuss the Navy’s LHD service life extension plans later in this report.

USS Fort Lauderdale (LPD 28). The Fort Lauderdale, delivered to the fleet in March 2022, is already facing limitations with its use in part because of poor equipment design. For example, according to ship and maintenance officials, the USS Fort Lauderdale faces challenges with the knuckle boom crane and Caley davit having high failure rates coupled with rising costs and ordering delays for parts.

Ship and maintenance officials also stated that the ship has challenges with fuel and ballast tank level indicators being unreliable or improperly calibrated.[36] Further, because the USS Fort Lauderdale’s tank level indicators are a new design, the ship’s technicians do not have the information needed to calibrate them. This requires the Navy to bring an industry qualified technician out every time the parts need recalibrating. Finally, the ship and maintenance officials stated that some LPD system selection choices involve proprietary parts that prevent the ship’s technicians from being able to maintain certain items, such as the fiber optic navigation lights.

USS Essex (LHD 2). The Essex has faced challenges with contractor work and quality control. RMC officials stated that, in a recent maintenance period for the Essex, a Naval Surface Warfare Center hired a modernization team to weld pipe joints for part of the high-pressure steam propulsion system. As previously noted, during major maintenance availabilities, the Navy conducts both maintenance and modernization activities. The RMC was aware the work was ongoing but did not have adequate knowledge to approve process control procedures for the work, nor the necessary controls in place to coordinate approvals with the modernization team.

RMC officials stated that the Naval Surface Warfare Center asked the RMC to obtain x-ray inspections of the welds after the modernization team had completed more than 300 of them.[37] The RMC became aware of issues with many of the welds only after these inspections, because the modernization team did not follow required quality assurance steps. This resulted in extensive rework and delays to the repair period. In the winter of 2024, we expect to report on similar oversight challenges with cruiser modernization periods.

The Navy’s lack of progress toward implementing solutions in identified areas for improvement allows for these maintenance challenges to persist. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, an agency should develop performance goals as a target level of performance expressed as a tangible, measurable objective against which progress toward achieving the objectives can be assessed within a time frame.[38] However, we found that the Navy has not developed performance goals to guide the ongoing improvement efforts identified in its May 2023 review. Additionally, while the Navy has yet to develop recommendations from its April 2024 review, the memo from the Vice Chief of Naval Operations directing it did not provide any guidance for establishing performance goals with tangible, measurable objectives and associated time frames to track implementation of recommendations developed during the review. In September 2024, senior Navy officials said they plan to include recommendations directed at specific organizations with measurable objectives and time frames. However, as of the end of October 2024, the Navy has yet to finalize the April 2024 review.

Without clear performance goals with tangible, measurable objectives and associated time frames to track and assess progress implementation for the May 2023 and April 2024 review recommendations, the Navy cannot appropriately assess progress toward achieving intended outcomes of efforts to address persistent maintenance challenges. Further, without these elements, the Navy risks missing opportunities to address identified maintenance issues in a comprehensive and timely manner to improve amphibious ship readiness outcomes.

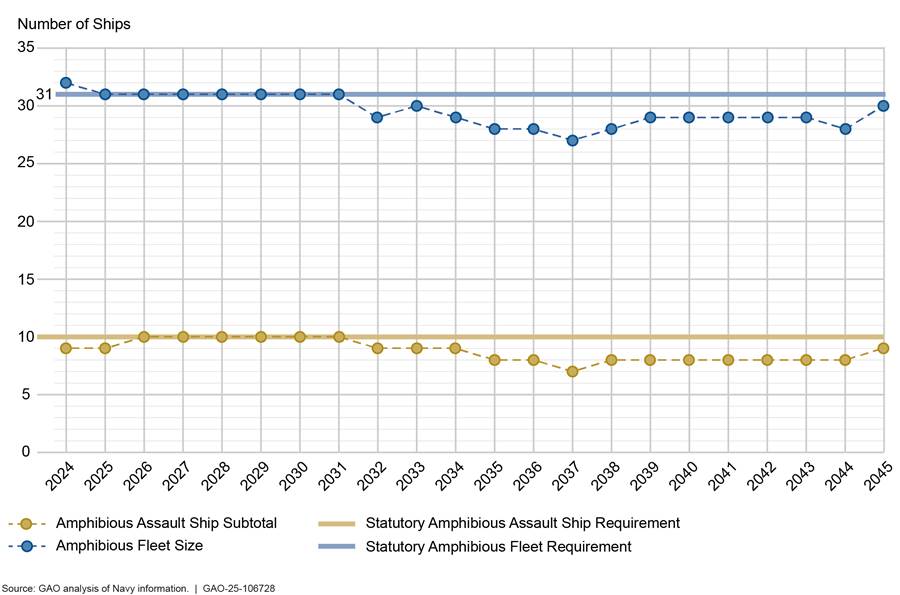

Navy’s Current Plans Do Not Support a 31-Ship Fleet by the 2030s

The Navy is likely to face difficulties meeting a statutory requirement to maintain a fleet size of at least 31 operational amphibious warfare ships between 2032 and 2040. The Navy currently plans to procure new LPD and LHA ships and recently entered into contracts intended to achieve cost savings using a multi-ship procurement authority provided by Congress. However, new ships alone are insufficient to maintain 31 ships for the next 15 years based on the Navy’s fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan. The Navy is also examining the possibility of extending the service lives of six LHD class ships and modernizing the LPD class ships. It is too early to tell whether these investments will help the Navy maintain available amphibious warships and mitigate potential gaps.

Navy Likely to Face Difficulties Meeting 31-Ship Amphibious Fleet Requirement

The Navy is likely to face difficulties meeting a statutory requirement to have a fleet size of at least 31 amphibious warfare ships into the 2030s, based on its existing investments and planned ship decommissions and divestments. This overall fleet size requirement includes not less than 10 amphibious assault (LHD and LHA) ships. Specifically, over the next decade, the Navy generally plans to buy a new LPD ship every other year and a new LHA every 4 years.

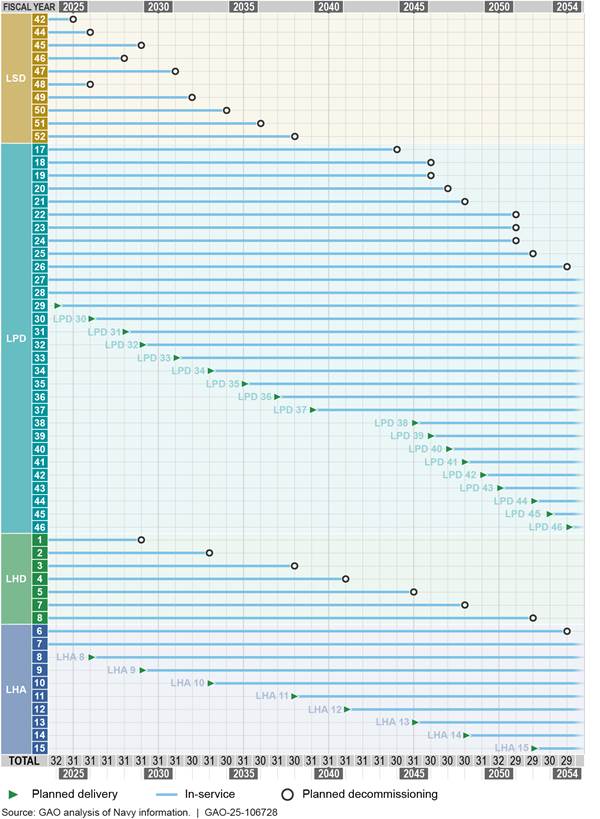

The Navy’s plan is optimistic. The Navy’s shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2025 is predicated on accelerating LHA procurements (and intended deliveries) to every 3.5 years. Based on estimates for amphibious ships for which the Navy awarded contracts in recent years (i.e., LPD 32 and LHA 9), LPDs take approximately 6.5 years to build—from contract award to delivery—and LHAs take approximately 7 years to build. LHA program officials expressed concerns about the shipbuilding workforce’s ability to meet the potentially accelerated targets. Additionally, any substantial increase in the current procurement cadence—a new LPD every other year, and a new LHA every 4 years—would likely have significant cost ramifications because large funding amounts would be required more frequently. Figure 8 depicts the Navy’s plans for acquiring and divesting amphibious warfare ships.

Figure 8: Navy Plan for the Future LSD, LPD, LHD, and LHA Amphibious Warfare Fleet Including Service Life Extensions and Divestments

Note: The ship totals reported in the figure do not include ships in the year of their proposed decommissioning but do include ships in the year of their delivery.

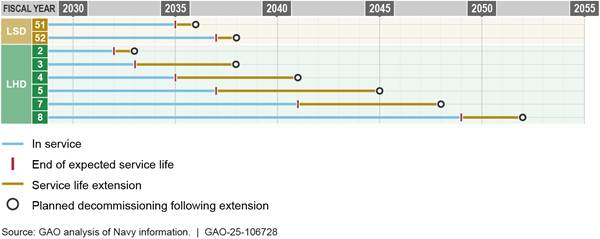

To avoid a sustained drop in fleet size, the Navy will need to keep nearly all its legacy amphibious assault ships in service past their expected service lives while it waits for new ships. The Navy’s shipbuilding plan, which meets the 31-ship requirement, relies on operating LHD and LSD class ships beyond their service lives. Specifically, the shipbuilding plan reflects extensions to six LHD class amphibious assault ships beyond their 40-year service lives. Additionally, the shipbuilding plan calls for operating two LSD class ships beyond their expected service lives by approximately 1 year even though Navy data suggest these ships do not have sufficient maintenance to operate for this long. The shipbuilding plan notes that the planning and investments needed for these actions will not be addressed until future budget requests, which OPNAV officials reported are significantly constrained. Figure 9 depicts the eight ships that the Navy needs to outlast their expected service lives to maintain a 31-ship inventory.

Figure 9: Fiscal Year 2025 Shipbuilding Plans for Future LSD and LHD Class Amphibious Warfare Ship Service Life Extensions

If the Navy is unable to extend the lives of these ships, it will fall short of the 31-ship requirement. As ships advance toward the end of their service lives, their conditions tend to worsen, maintenance becomes pricier, and the ships are out of service for longer periods of time. OPNAV officials indicated that the age of LHD class ships will require the Navy to address several challenges with its life extension program. For example, as previously mentioned, OPNAV officials said LHD class ships are some of the last non-nuclear steam propulsion ships in the Navy. Additionally, officials said LHD class ships face challenges with older systems, including those that supply power and cooling to the ships’ communications equipment.[39] As a result, the Navy’s projections for maintaining a 31-ship fleet into the future require significant levels of funding and, even if it receives this funding, are optimistic given the condition of the fleet.

Navy officials said current planning efforts are focused on at least two LHDs, with an early estimate of up to $1 billion per ship, for extensions of up to 10 years. Extending the service lives of LHD class ships may be challenging in the Navy’s fiscally constrained environment. Without extending the service life of at least two LHD class ships, the Navy will not have a 31-ship fleet by 2036.[40] Specifically, the Navy plans to begin decommissioning LHD class ships in fiscal year 2029 and, by fiscal year 2032—absent service life extensions—the total number of amphibious warfare ships will drop to 29, where it will remain for most of the next several years. Further, once the Navy begins to decommission a ship class, such as LSDs, it becomes more difficult to maintain the existing ships since demand for parts and specialized labor begins to decrease. Figure 10 provides an overview of the projected overall amphibious fleet size and amphibious assault ship fleet size based on the Navy’s upcoming ship delivery and decommissioning plans, if the Navy is not able to bring its long-term plans to extend the lives of LHD and LSD ships to fruition.

Figure 10: Projected Amphibious Warfare Fleet Size If the Navy Does Not Pursue Service Life Extensions or Accelerate Production

Given the Navy’s plans for buying and decommissioning ships, a few recent trends and challenges could put maintaining the statutory fleet size at risk. We reported in 2018 that cost growth has contributed to the erosion of the Navy’s buying power with ship costs exceeding estimates by billions of dollars.[41] We also noted that the Navy’s shipbuilding programs have had years of construction delays and, even when the ships eventually reach the fleet, they often fall short of quality and performance expectations. Additionally, the Secretary of the Navy’s 45-Day Shipbuilding Review in 2024 noted significant construction delays across multiple ship classes, as well as issues with design stability and acquisition and contract strategies, among others. Finally, in May 2022, we found that the Navy faced a nearly $1.8 billion maintenance backlog.[42]

According to service officials, the Navy is also planning significant efforts for LPD class ships. The first effort is a midlife modernization program intended to keep the ships operationally available until the end of their expected 40-year service life. As shown in the figures above, it is critical for amphibious warfare ships to reach and even go beyond their expected service lives to maintain the size of the amphibious fleet into the future. The Navy anticipates that the midlife modernization period will begin in 2029 and cost approximately $140 million per ship—for a total of more than $1.5 billion based on the current plan for midlife modernization on 11 ships. The second effort, according to Navy officials, is a modernization effort intended to increase the ship’s relevance in the future operating environment by expanding weapons, radar, and other capabilities. Officials are in the early stages of planning this modernization effort and said the Navy had not yet developed budget estimates for the effort as of the time of our review.

Navy Plans to Acquire New Ships Using Multi-Ship Authority

As of March 2024, the Navy planned to use a multi-ship procurement approach authorized by statute. These kinds of special acquisition authorities allow the Navy to purchase multiple ships on one or more contracts to achieve cost savings (referred to as a multi-ship procurement).[43]

In fiscal years 2021 through 2023, the National Defense Authorization Acts provided the Navy with multi-ship acquisition authorities that would enable the purchase of multiple LPD and LHA class ships to achieve cost savings. This is accomplished, in part, by establishing a stable demand signal for shipbuilders and their suppliers through the Navy entering into a contract to buy multiple ships within a specified time frame, even though funding for the authorized procurement is still provided on an incremental basis. Use of these multi-ship procurement authorities for certain amphibious shipbuilding programs also requires the Navy to provide certifications to Congress relating to expected cost savings and the stability of the ship designs, among other things.[44]

In December 2020, the Navy reported to Congress that it could save taxpayers more than $700 million to procure LPDs 31-33 and LHA 9 using multi-ship procurement authorities. By the time Congress authorized use of these special authorities for certain amphibious ships, the Navy reported that it had already put LPD 31 on contract but reported its intent to purchase LPDs 32-33 and LHA 9 using multi-ship procurement authorities. However, since receiving these special procurement authorities in fiscal year 2021, the Navy has bought two LPDs and one LHA, each funded and procured one at a time.

Total acquisition costs for the next two new ships, as reported in the Navy’s fiscal year 2025 budget proposal, are approximately $2.1 billion for the next LPD ship (LPD 33), and $4.6 billion for the next LHA ship (LHA 10). The Navy subsequently reported that it did not intend to use multi-ship procurement authorities for those ships, citing the need to further assess force structure needs before committing to buy multiple amphibious warships. According to Navy officials, the service paused LPD procurements in fiscal year 2023 after the Office of the Secretary of Defense directed the Navy to first evaluate amphibious force structure requirements.

In fiscal year 2024, the Office of the Secretary of Defense directed a study to determine how the Navy might be able to save money for the LPD platform through both acquisition and sustainment. According to LPD program officials, this study analyzed different options for the future of the LPD program, including whether the Navy could reduce costs through reducing some capabilities. However, the study concluded that the current ship configuration remains the best balance between capability and cost for the Navy and Marine Corps.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 authorized the Navy to procure up to five amphibious ships using one or more contracts. In September 2024, the Navy announced that it awarded contracts totaling nearly $9.5 billion for 1 LHA and 3 LPD ships using a multi-ship procurement approach. The Navy projects savings of 7.25 percent, compared with purchasing the ships individually, or approximately $900 million.

Conclusions

The Navy’s amphibious fleet is the linchpin of the Marine Corps’ amphibious warfare training and operations. However, the fleet suffers from poor availability that has negatively affected training and operations. Absent establishing time frames for completion of a Navy and Marine Corps agreement on the number of amphibious ships that should be available at a given time, with objective and measurable metrics to guide it, the services will be at continued risk of late or disaggregated Marine deployments.

Further, poor material condition of the ships and delays in their maintenance has negatively affected availability of the amphibious fleet. Decisions in recent years to divest ships before reaching the end of their expected service lives and prior to completing a waiver process involving submitting a certification to congressional defense committees triggered decisions to forego critical maintenance and worsened the condition of those ships. Clarifying policy on when it is appropriate to cancel maintenance on amphibious ships proposed for divestment will enhance the Navy’s ability to manage competing budget priorities.

Moreover, the Navy has not yet implemented the recommendations from its May 2023 review to address the wide range of maintenance problems affecting readiness in the amphibious fleet. Establishing performance measures to guide improvements to amphibious ship maintenance challenges identified in its May 2023 and April 2024 reviews will help the Navy improve amphibious ship readiness outcomes.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of four recommendations to the Department of the Navy.

The Secretary of the Navy, in coordination with the Commandant of the Marine Corps, should refine definitions related to amphibious warfare ship availability to include specific and measurable terms. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Navy, in coordination with the Commandant of the Marine Corps, should establish a time frame for completing and implementing their ongoing joint plan to address ship availability concerns and ensure that the analysis results in a specific number of amphibious warfare ships that the Navy and Marine Corps require to be available at any given time. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Chief of Naval Operations updates the Navy’s amphibious ship depot maintenance policy to clarify that, absent operational needs, the Navy should not cancel depot maintenance for amphibious ships proposed for divestment that have yet to reach the end of their expected service life, prior to providing the requisite certification to the congressional defense committees and completing the divestment waiver process. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Chief of Naval Operations establishes performance goals with tangible, measurable objectives and associated time frames that can be used to measure progress, for implementing the recommendations identified in the May 2023 Amphibious Readiness Review and, when completed, for implementing recommendations resulting from the Navy’s April 2024 review. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the Navy for review and comment. The Navy provided an official comment letter (reproduced in appendix III) noting concurrence with three of our recommendations and partial concurrence with one of them. The Navy also provided technical comments which we incorporated as appropriate.

The Navy partially concurred with our third recommendation to modify the Navy’s maintenance policy to keep scheduled depot maintenance for amphibious ships proposed for divestment. The Navy said that the 10 U.S.C. 2244a prohibition on modifying vessels the Secretary plans to retire prevents it from fully implementing the recommendation. However, the Navy also said in its response that it will schedule maintenance, including depot-level repair as necessary, to maintain such ships in operational condition. The Navy noted that the Secretary may waive the 10 U.S.C. 2244a prohibition when ship modification is in the interest of national security, which includes additional maintenance and modernization efforts when the Navy plans operational employment for a ship.

The purpose of our recommendation is to ensure the Navy does not defer critical ship maintenance before completing the 10 U.S.C. 8678a certification process, including opportunity for congressional approval, for divesting ships before the end of their planned service life.

We maintain that the Navy should ensure that maintenance availabilities are not canceled before the 10 U.S.C. 8678a congressional certification process for early divestment is completed. The Navy should also document, such as in budget guidance, the steps that it will take to ensure maintenance availabilities are not canceled in these situations. Taking these actions will enable the Navy to meet the intent of our recommendation.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and other interested parties, including the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of the Navy. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions concerning this report, please contact us at (202) 512-4841 or oakleys@gao.gov, or (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov. Contact points for our offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Staff members making key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Shelby S. Oakley

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Diana Maurer

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Table 2 below summarizes selected provisions from the National Defense Authorization Acts for Fiscal Years 2023 and 2024 that relate to the amphibious warfare fleet. We selected these provisions based on their relevance to the size of the amphibious warfare fleet, fleet maintenance and readiness issues, decisions relating to decommissioning ships in the fleet, and expanded role of the Commandant of the Marine Corps in setting requirements for the fleet.

Table 2: Summary of Selected National Defense Authorization Act Provisions from Fiscal Years 2023 and 2024 Related to the Navy’s Amphibious Fleet

|

James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 |

|

|

Section and title of provision |

Brief description of provision |

|

Sec. 129. Procurement Authorities for Certain Amphibious Shipbuilding Programs |

Authorizes the Secretary of the Navy to enter into one or more contracts for the procurement of up to five LPD (amphibious transport dock) and LHA (amphibious assault ship) class ships. |

|

Sec. 1022. Navy Consultation with Marine Corps on Major Decisions Directly Concerning Marine Corps Amphibious Force Structure and Capability |

Requires the Secretary of the Navy to ensure that the views of the Commandant of the Marine Corps are appropriately considered before a major decision is made by the Navy outside the Marine Corps on a matter that directly concerns Marine Corps aviation or amphibious force structure and capability. |

|

Sec. 1023. Amphibious Warship Force Structure |

Requires that the naval combat forces of the Navy shall include not less than 31 operational amphibious warfare ships, of which not less than 10 shall be amphibious assault ships. An operational amphibious ship includes an amphibious ship that is temporarily unavailable for worldwide deployment due to routine or scheduled maintenance or repair. |

|

Sec. 1025. Amphibious Warfare Ship Assessment and Requirements |

Assigns the Commandant of the Marine Corps responsibility for developing requirements relating to amphibious warfare ships in Navy battle force ship assessments. Sec. 1019 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 added requirements for naval vessels with the primary mission of transporting Marines. |

|

Sec. 1029. Prohibition on Retirement of Certain Naval Vessels |

Prohibits the Navy from retiring—or planning to retire—four LSD (dock landing ship) class ships using funds authorized by the act to be appropriated for fiscal year 2023. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 |

|

|

Section and title of provision |

Brief description of provision |

|

Sec. 352. Semiannual Briefings on Operational Status of Amphibious Warship Fleet |

On a recurring basis, requires the Secretary of the Navy to brief the congressional defense committees on the operational status of every amphibious warfare ship in the fleet. Among other requirements, these briefings must include information regarding: the average quarterly operational availability of the amphibious warship, an update on any delays in the completion of scheduled or unscheduled maintenance, and a plan to schedule maintenance and repair for the amphibious warship in a manner that provides for the continuous operation of a total of three Amphibious Ready Groups and Marine Expeditionary Units as soon as practicable. |

|

Sec. 1021. Prohibition on Retirement of Certain Naval Vessels |

Prohibits the Navy from retiring—or planning to retire—three LSD class ships using funds authorized by the act to be appropriated for fiscal year 2024. |

|

Sec. 1022. Authority to Use Incremental Funding to Enter into a Contract for the Advance Procurement and Construction of a San Antonio-Class Amphibious Ship |

Allows the Secretary of the Navy to use funds authorized to be appropriated by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, or funds otherwise made available for Navy shipbuilding and conversion in fiscal years 2023 through 2025, to enter into an incrementally funded contract for the advance procurement and construction of a San Antonio-class amphibious ship. |

|

Sec. 1066. Annual Report and Briefing on Implementation of Force Design 2030 |

Requires the Commandant of the Marine Corps to submit a report that details, among other things, a description of the amphibious warfare ship and maritime mobility requirements of the Marine Corps, an assessment of whether the 30-year shipbuilding plan of the Navy meets amphibious ship requirements, and an assessment of Marine Corps force structure and the readiness of Marine Expeditionary Units compared to availability of amphibious ships comprising an Amphibious Ready Group over the 2 fiscal years preceding the fiscal year during which the report is provided and the expected availability for the subsequent 2 fiscal years. |

Source: GAO analysis of the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117–263 (2022); National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31 (2023). | GAO‑25‑106728

House Report 117-397, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, includes a provision for us to review the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ plans for the amphibious warfare fleet. Our report examines the extent to which (1) the Navy and Marine Corps are working to address amphibious fleet availability for operations and training; (2) the Navy faces maintenance and sustainment challenges affecting the amphibious warfare fleet and is working to address them; and (3) the Navy is positioned to meet statutory fleet size requirements into the future.

To assess the extent to which the Marine Corps and Navy are working to address amphibious fleet availability for training and operations, we first examined Marine Corps requirements for available amphibious warships. We reviewed documentation provided by the Marine Corps and interviewed officials from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations Expeditionary Warfare office and the Marine Corps Combat Development & Integration office to understand the Navy’s plans for meeting those requirements. To assess the Navy’s ability to meet those requirements, including meeting appropriate readiness levels, we reviewed documentation from the Marine Corps and Naval Sea Systems Command to evaluate the extent that amphibious warfare ship maintenance is completed on schedule. We also reviewed documentation and statements from Navy and Marine Corps officials relating to their efforts to determine the number of ships that need to be available for operations and training at a given time. We evaluated this information against Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government relating to defining objectives and risk tolerance.[45]

To assess the extent to which the Navy is addressing maintenance and sustainment challenges affecting the amphibious fleet, we first evaluated the condition of the fleet. To assess the condition of the Navy’s amphibious warfare fleet, we reviewed recent assessments conducted by the Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program and the Board of Inspection and Survey. We also reviewed documents on the Navy’s efforts to identify and address known maintenance issues—including deferred maintenance—and to manage major maintenance periods. These include the Navy’s most recent amphibious fleet review, the 2023 Amphibious Readiness Review. We assessed that review, including the five areas identified for long-term improvements, against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government that discuss the definition of objectives.[46] We also interviewed a senior official from Commander, Naval Surface Forces, the organization leading the review.

We visited amphibious warfare ships undergoing maintenance at Naval Station Norfolk and Naval Base San Diego: (1) USS Wasp, LHD 1; (2) USS Fort Lauderdale, LPD 28; (3) USS Tortuga, LSD 46; (4) USS Germantown, LSD 42; (5) USS Essex, LHD 2; and (6) USS Portland, LPD 27. We spoke with crew members and commanding officers about their perspectives regarding the condition of these ships. We also spoke with the officers and crew of these six ships to obtain additional understanding of identified maintenance issues and actions, if any, taken to address them. We also interviewed officials from Commander, Naval Regional Maintenance Center; Southwest Regional Maintenance Center; and Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center. We also compared maintenance issues identified in interviews with the four root causes the Navy identified in its 2023 amphibious readiness review to ascertain which root causes applied to those issues.

To assess the extent to which the Navy is positioned to meet amphibious warfare fleet requirements, we reviewed plans for acquiring new amphibious warships over the next 3 decades. We also reviewed budget reports from the prior 2 years and Navy cost estimate documentation relating to the cost of new amphibious warships and modernization efforts. We spoke with officials from various offices of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Naval Sea Systems Command to gain an understanding of acquisition plans and projected costs.

We reviewed documentation provided by the Navy identifying the service’s anticipated costs to modernize ships in the fleet. We also met with officials from Naval Sea Systems Command, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations Expeditionary Warfare office, and the Marine Corps Combat Development & Integration office to understand the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ plans for modernizing these ships.

We also assessed the extent to which the Navy has used special procurement authorities to save on amphibious fleet procurement costs. Specifically, we reviewed prior legislation, such as National Defense Authorization Acts. We also reviewed Navy documentation, such as shipbuilding plans from the last 2 years, on decisions relating to amphibious ship acquisitions. We spoke with officials from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the program office for the LPD and LHA class ships to discuss acquisition and contracting planning.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to December 2024, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Shelby S. Oakley, (202) 512-4841 or oakleys@gao.gov, and Diana Maurer, (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff members made key contributions to this report: Laurier Fish (Assistant Director), Jodie Sandel (Assistant Director), Andrew H. Redd (Analyst-in-Charge), Jeff Carr, Susan Ditto, Stephanie Gustafson, Tonya Humiston, Anne Louise Taylor, Kaitie Trabucco, and Adam Wolfe.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Appendix I provides a summary of a selected number of these provisions.

[2]GAO, Weapon System Sustainment: Navy Ship Usage Has Decreased as Challenges and Costs Have Increased, GAO‑23‑106440 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 31, 2023); Navy Ships: Applying Leading Practices and Transparent Reporting Could Help Reduce Risks Posed by Nearly $1.8 Billion Maintenance Backlog, GAO‑22‑105032 (Washington, D.C.: May 9, 2022); Navy Ship Maintenance: Actions Needed to Monitor and Address the Performance of Intermediate Maintenance Periods, GAO‑22‑104510 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 8, 2022); and Navy Shipbuilding: Increasing Focus on Sustainment Early in the Acquisition Process Could Save Billions, GAO‑20‑2 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 24, 2020).