SINGLE AUDITS

Interior and Treasury Need to Improve Their Oversight of COVID-19 Relief Funds Provided to Tribal Entities

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106741

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106741. For more information, contact Anne Sit-Williams at (202) 512-7795 or sitwilliamsa@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106741, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

SINGLE AUDITS

Interior and Treasury Need to Improve Their Oversight of COVID-19 Relief Funds Provided to Tribal Entities

Why GAO Did This Study

Treasury and Interior awarded $32.7 billion in COVID-19 relief funds to tribal entities, including two of the largest COVID-19 relief programs for tribal governments. Under the Single Audit Act, federal agencies are required to provide oversight for the funds that they award.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to report on its ongoing monitoring efforts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This report examines Interior’s and Treasury’s policies and procedures for (1) tracking the timely submission of required single audit reports from tribal entities to which the agencies awarded COVID-19 relief funds and (2) reviewing and following up on the findings of these audits. It also describes the assistance these agencies provided to tribal entities to help them navigate the single audit process.

GAO interviewed agency officials, three tribal-serving organizations, and a Tribe; analyzed agency data on tribal recipients of COVID-19 relief funds and tribal single audit submissions; and reviewed relevant federal statutes, regulations, and agency policies and procedures related to tracking and reviewing single audit reports.

What GAO Recommends

GAO urges prompt implementation of an open recommendation that Treasury issue timely management decisions. GAO is making three new recommendations—two to Treasury and one to Interior—to further enhance the single audit oversight provided to tribal entities. Interior and Treasury agreed with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

For the audit period of this report, the Single Audit Act requires nonfederal entities that spend $750,000 or more in federal awards in a year to undergo a single audit, which is an audit of an entity’s financial statements and federal awards, or in select cases a program-specific audit. The Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) single audit guidance requires that federal awarding agencies ensure that award recipients submit single audit reports timely. As federal awarding agencies, the Department of the Interior and the Department of the Treasury track the submission of required single audit reports from tribal recipients (see figure). Interior appropriately designed procedures to identify and track tribal recipients that did not submit required single audit reports or were not required to do so, but Treasury has not. Treasury stated that it did not have existing single audit processes when its COVID-19 relief programs were established. By finalizing and implementing such procedures, Treasury could better ensure that its recipients are meeting its program requirements.

Single Audit Report Submissions Tracked by Interior and Treasury for Tribal Recipients Awarded COVID-19 Relief Funds, Fiscal Years 2020 through 2022, as of October 31, 2023

OMB’s single audit guidance also requires awarding agencies to follow up on single audit findings to ensure that award recipients take timely and appropriate action to correct deficiencies identified by the audits. GAO found that both Interior and Treasury have policies and procedures to review findings and issue management decisions on the adequacy of tribal entities’ plans to correct findings, but Treasury did not issue timely management decisions. In addition, neither agency has procedures for appropriately monitoring the implementation of tribal entities’ corrective action plans. Until Interior and Treasury develop such procedures, these agencies may be missing opportunities to improve their oversight of federal awards and to help tribal entities address findings.

Interior and Treasury assisted tribal entities that received COVID-19 relief funds in complying with funding and single audit requirements. In general, tribal-serving organizations and a tribal official that GAO spoke with stated that Interior and Treasury have improved their assistance since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the tribal-serving organizations also noted that agency assistance did not fully consider the unique needs of tribal recipients and offered suggestions for enhancing such assistance.

Abbreviations

AO awarding official

ARTT Audit Report Tracking Tool

BIA Bureau of Indian Affairs

BIE Bureau of Indian Education

DIEA Division of Internal Evaluation and Assessment

FAC Federal Audit Clearinghouse

IA Indian Affairs

ISDEAA Indian

Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act,

as amended

OCA Office of Capital Access

OMB Office of Management and Budget

OSG Office of Self-Governance

OTNA Office of Tribal and Native Affairs

SAR single audit report

SLFRF State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 7, 2024

Congressional Committees

Since March 2020, the federal government has awarded billions of dollars in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including awarding funds to Tribes and tribal entities.[1] The unprecedented increase in federal awards distributed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, including many awards to recipients receiving a substantial amount of federal funds for the first time, has emphasized the importance of single audits. Single audits provide an oversight tool for federal agencies to help ensure that funds are properly used for allowable purposes.

Of the at least $43.6 billion[2] that COVID-19 relief laws[3] appropriated for federal programs serving Tribes, tribal citizens, and tribal organizations,[4] $2.27 billion was appropriated to the Department of the Interior. Also, the Department of the Treasury administered two of the largest COVID-19 relief programs for tribal governments—$20 billion from the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside and $8 billion from the Coronavirus Relief Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside. See appendix I for more details about the COVID-19 relief funding that Interior and Treasury administered.

Under the Single Audit Act,[5] Interior and Treasury have oversight responsibilities for the funds awarded to tribal entities.[6] For the audit period of this report, the Single Audit Act and the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) single audit guidance required tribal entities that spent $750,000 or more in federal awards in a fiscal year to undergo a single audit (an audit of an entity’s financial statements and federal awards).[7] These single audits help Interior and Treasury reasonably ensure that federal funds are used in accordance with applicable legal requirements. Interior and Treasury are responsible for reviewing these single audits and following up on any audit findings to provide reasonable assurance that tribal recipients take timely and appropriate action to correct deficiencies identified through the single audit process.

The CARES Act includes a provision for us to conduct oversight of the funds made available to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] This report examines the extent to which Interior and Treasury appropriately designed and implemented policies and procedures to help ensure they (1) track the timely submission of required single audit reports from tribal entities to which they awarded COVID-19 relief funds and (2) review and follow up on the findings of these audits, including issuing written management decisions on tribal entities’ plans to correct findings in a timely manner. This report also describes Interior’s and Treasury’s assistance, and tribal perspectives on this assistance, to help tribal entities navigate the single audit process, address single audit findings, and prevent future single audit deficiencies.

For our first and second objectives, we interviewed Interior and Treasury officials to discuss their single audit processes for tracking, reviewing, and following up on single audit reports. We also obtained and reviewed the design of Interior’s and Treasury’s single audit policies and procedures. We assessed Interior’s and Treasury’s policies and procedures against the Single Audit Act,[9] OMB’s single audit guidance,[10] and federal internal control standards[11] related to the control activities component to determine the extent to which the agencies conducted appropriate oversight using single audit reports.

To address our first objective, we obtained Interior’s and Treasury’s lists of tribal entities to which they awarded COVID-19 relief funds for fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022. We compared this list to a list of single audit reports that Interior and Treasury obtained from tribal entities for the same period (the most recent period for which single audit reports were submitted). For those tribal entities that Interior and Treasury awarded COVID-19 relief funds but had not submitted single audit reports, we reviewed each agency’s data and inquired with agency officials to determine whether Interior and Treasury had implemented a process to track whether a tribal recipient was required to submit a single audit report and had not.

For our second objective, we selected and reviewed a sample of single audit reports that (1) were submitted by tribal entities that received most of their funding from Interior or Treasury; (2) contained findings related to Interior or Treasury COVID-19 relief programs; and (3) were submitted for fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022. For Interior, we reviewed all 28 single audit reports that met the criteria. For Treasury, we randomly selected a nongeneralizable sample of 30 single audit reports from the 177 reports that met the criteria. Because we used a nongeneralizable sample to select the single audit reports, our findings cannot be used to make inferences about the entire population of reports.

To address our third objective, we met with Interior and Treasury officials to discuss the assistance these agencies provide to tribal entities for complying with requirements of the Single Audit Act and OMB’s single audit guidance. We also interviewed representatives from three tribal-serving organizations and one tribal official to obtain their perspectives on the support Interior and Treasury provide to tribal entities. We identified and selected tribal-serving organizations that (1) operate nationally; (2) focus on strengthening tribal finance, supporting economic development, and building tribal government capacity; and (3) were willing to meet with us. Using the list of single audits reviewed under objective two, we identified and selected Tribes that (1) had single audit findings related to both Interior and Treasury programs; (2) had not been recently contacted by GAO in the course of other GAO engagements; and (3) were willing to meet with us. The perspectives of the representatives from three tribal-serving organizations and one tribal official we interviewed cannot be generalized to those we did not interview. Additional details regarding our objectives, scope, and methodology are provided in appendix II.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The Single Audit Act and Federal Agencies’ Responsibilities

For the audit period of this report, the Single Audit Act and OMB’s single audit guidance required nonfederal entities that spent $750,000 or more in federal awards in a fiscal year to undergo a single audit or, in limited circumstances, a program-specific audit.[12] Single audits must be performed by an independent auditor and conducted pursuant to generally accepted government auditing standards.[13] Single audits are typically done either by a private firm hired by the award recipient or by a state or local government audit agency.

OMB’s single audit guidance requires each award recipient that meets the single audit threshold to submit an audit reporting package to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC).[14] The reporting package must include (1) the award recipient’s financial statements and schedule of expenditures of federal awards; (2) a summary schedule of prior audit findings; (3) the auditor’s report, including an opinion on whether the award recipient’s financial statements and schedule of expenditures of federal awards are fairly stated; and (4) the award recipient’s corrective action plans to address the auditor’s findings, as applicable.[15] Federal agencies and other interested parties may access the reporting package through the FAC.[16]

OMB’s single audit guidance requires that federal awarding agencies assume oversight responsibility for the funds that they award to nonfederal entities, including tribal entities.[17] As shown in table 1, these responsibilities include (1) ensuring timely receipt of completed audit reports, (2) following up on audit findings, (3) monitoring recipient’s corrective actions on findings, and (4) tracking effectiveness of the single audit process.

|

1. Ensure that audits are completed and reports are received in a timely manner. 2. Provide technical audit advice and assistance. 3. Follow up on audit findings and monitor the recipient taking appropriate and timely corrective action. 4. Coordinate with other agencies on management decisions for audit findings that affect the federal programs of more than one agency. 5. Issue management decisions. 6. Appoint an official who is responsible for ensuring that the agency fulfills single audit requirements. 7. Appoint a key management single audit liaison to serve as the point of contact for the single audit process and promote interagency coordination, consistency, and sharing. 8. Use audit follow-up techniques to promote prompt corrective action by improving communication, fostering collaboration, promoting trust, and developing an understanding between the federal agency and the nonfederal entity. 9. Provide OMB annual updates to the compliance supplement, which is an authoritative source for auditors to use in identifying and understanding existing compliance requirements that should be considered as part of an audit. 10. Develop a baseline, metrics, and targets to track the effectiveness of the single audit process. 11. Oversee training related to the single audit process. |

Source: GAO summary of Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance. I GAO‑25‑106741

As part of their responsibilities, federal awarding agencies must ensure that award recipients complete and submit single audit reports within the earlier of 30 calendar days after receipt of the auditor’s report or 9 months after the recipient’s audit period.[18] However, as we have previously reported, the FAC does not have the capability to identify federal award recipients that are required to submit a single audit. Thus, federal agencies are not able to use the FAC to identify recipients that were required to submit a single audit but did not do so, including those that received federal awards from multiple federal agencies that, when combined, could have caused them to spend at least $750,000. In addition, there is no oversight mechanism (i.e., responsible government-wide entity or comprehensive database) that tracks federal award expenditures in real time or determines when an award recipient, including a tribal entity, should submit a single audit report. Federal awarding agencies often do not have a means for determining whether a federal award recipient met the expenditure threshold for a single audit. Some federal agencies reported that they do not have access to other agencies’ awards information to be able to make such a determination.[19]

OMB’s single audit guidance requires that federal awarding agencies follow up on audit findings to ensure that the recipient takes appropriate and timely corrective action.[20] As part of this follow-up, the agencies must issue management decisions—written determinations on the adequacy of recipients’ proposed corrective action plans to address audit findings—within 6 months of acceptance of the audit report by the FAC.[21]

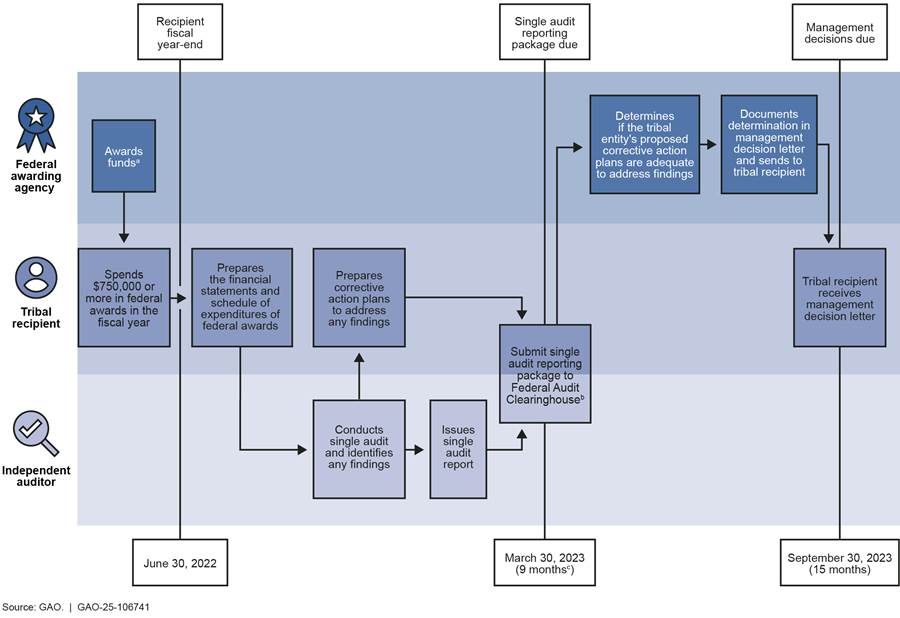

The agencies must also monitor recipients taking appropriate and timely corrective action and provide technical advice and counsel to award recipients and auditors as requested.[22] In addition, federal awarding agencies must develop a baseline, metrics, and targets to track the effectiveness of their process to follow up on audit findings and on the effectiveness of single audits in improving nonfederal entity accountability and their own federal award decisions.[23] Figure 1 depicts the overall process and example time frames for single audit report submissions by tribal recipients, as well as for single audit reviews conducted by federal awarding agencies.

aAgencies may award funds in a prior fiscal year or in the same fiscal year that they are spent.

bThe independent auditor or the tribal recipient uploads the single audit reporting package to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC). Both the auditor and the tribal recipient are required to certify the submission of the single audit reporting package. See 2 C.F.R. § 512(b).

cThe Office of Management and Budget (OMB) directed federal awarding agencies to allow federal award recipients and subrecipients with fiscal year-end dates through June 30, 2021, to delay completing and submitting their single audit reporting packages to the FAC to 6 months beyond the normal due date. See Office of Management and Budget, Promoting Public Trust in the Federal Government through Effective Implementation of the American Rescue Plan Act and Stewardship of the Taxpayer Resources, OMB Memorandum M-21-20 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 19, 2021).

Interior and Treasury Offices Responsible for Single Audit Oversight of Federal Awards to Tribal Entities

Interior. The Office of Assistant Secretary – Indian Affairs (IA) is in the Office of the Secretary of the Interior and administers federal programs for Tribes and tribal citizens. As shown in figure 2, IA includes components, such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), and other offices and divisions under IA’s responsibilities. IA directly administers programs (direct service) or award funding for tribally administered programs. IA oversees the processing of single audit reports for federal awards administered through cognizant bureaus and offices under its purview, including BIA, BIE, and the Office of Self-Governance (OSG). As part of its single audit oversight responsibilities, IA designated the Division of Internal Evaluation and Assessment (DIEA) to coordinate with BIA, BIE, and OSG and manage the overall single audit oversight and review process for tribal entities.

Figure 2: The Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs’ Organizational Chart for Single Audit Oversight

As outlined in IA’s Single Audit Report Handbook,[24] DIEA monitors the submission of tribal single audit reports, the review of single audit findings, issuance of management decisions, and audit resolution and closure. DIEA also serves as the liaison office between applicable offices within IA (i.e., BIA, BIE, and OSG), Interior’s Office of Financial Management, Interior’s Office of Inspector General, and external auditors. DIEA is responsible for IA policy and provides guidance to IA offices on tribal single audits to help ensure IA compliance with the Single Audit Act and OMB’s single audit guidance.

Treasury. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Treasury did not have existing single audit processes or staff. The agency built its single audit capabilities by hiring additional staff with single audit expertise and developing policies and procedures for reviewing single audit findings and issuing management decisions. Treasury designated its Office of Recovery Programs as the office responsible for overseeing its single audit responsibilities for COVID-19 relief programs. In 2023, this office was renamed the Office of Capital Access (OCA).[25]

OCA manages the single audit review process for its programs and tracks the submission of single audit reports from tribal entities and other nonfederal entities. As outlined in Treasury’s Single Audit Procedures, OCA’s responsibilities include[26]

· monitoring the submission of single audit reports to the FAC;

· reviewing single audit reports to assess findings related to Treasury’s awards and the recipients’ corrective action plans, and issuing management decision letters to Treasury’s COVID-19 relief fund recipients;

· providing technical advice and counsel to recipients to help ensure their compliance with the terms and conditions of their award agreements;

· collecting, storing, and conducting analyses on single audit data retrieved from the FAC for award recipients to enable OCA to perform its single audit-related responsibilities; and

· coordinating single audit efforts, as appropriate, with other Treasury offices, OMB, and the audit community.

Treasury also established the Office of Tribal and Native Affairs in September 2022 to advise on economic and recovery programs and other policy matters that affect tribal communities and to coordinate tribal consultations and listening sessions, among other services.

Importance of Single Audit Reporting for Tribal Entities

Single Audit Reports Provide Information on Tribal Recipients’ Financial Management, Internal Control, and Compliance

Single audit reports provide valuable information on the design appropriateness and operating effectiveness of internal controls over compliance for major federal award programs.[27] For example, single audit reports convey whether a tribal entity’s accounting system has adequate internal controls to provide full accountability for assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenditures. Single audit reports can also help determine whether financial reports contain accurate and reliable financial data and if federal award funds were spent in accordance with the terms and conditions of award agreements and applicable laws or regulations that may have a direct and material effect on major programs.

Single audit reports convey whether a tribal recipient has federal award audit findings, including certain types of questioned costs and likely or known fraud.[28] For example, in one of the single audit reports we reviewed, an independent auditor found that a Tribe lacked sufficient oversight to ensure that procurement policies were consistently followed when spending COVID-19 relief funds, resulting in questioned costs of about $7,000. In another single audit report, an independent auditor reported that a Tribe was not able to provide sufficient support to confirm that COVID-19 relief funds were spent in accordance with the terms and conditions of the award, resulting in questioned costs of approximately $180,000. Reported federal award findings help identify weaknesses in a timely manner. Correcting these identified weaknesses may help reasonably assure the effective use of federal funds and reduce the likelihood of federal improper payments.

Single Audit Reports Could Affect Tribes’ Eligibility for Participation in Self-Governance

By correcting single audit deficiencies, Tribes may improve their financial stability and financial management capability. In addition, single audit results may affect tribes’ eligibility for self-governance compacts under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, as amended (ISDEAA).[29] ISDEAA authorizes Interior to enter into self-determination contracts and self-governance compacts at the request of eligible Tribes.[30] Both self-determination contracts and self-governance compacts authorize Tribes to take over the administration of certain federal programs previously administered by Interior and other federal agencies. Self-governance compacts, in particular, provide the Tribes with some flexibility in program administration by allowing Tribes to redesign or consolidate programs included in the compact and to reallocate funds among those programs.[31] For example, such flexibility allowed a Tribe to develop and manage its own COVID-19 response programs without obtaining permission from the federal agency; as a result, the Tribe quickly responded to and mitigated risks related to the pandemic as well as protected the health and well-being of the tribal community.[32]

Interior’s OSG is responsible for developing and implementing the Tribal Self-Governance Program. To be eligible to participate in the Tribal Self-Governance Program and enter into self-governance compacts, ISDEAA requires a Tribe to (1) successfully complete the mandatory planning process, (2) request participation in self-governance by an official action of a tribal governing body, and (3) demonstrate financial stability and financial management capability.[33]

To demonstrate the required financial stability and financial management capability to be eligible to enter into a self-governance compact, ISDEAA requires that a Tribe, for the 3 fiscal years preceding the date on which it requests to participate in the Tribal Self-Governance Program, have no uncorrected significant and material audit exceptions in the required annual audit of its self-determination or self-governance agreements with any federal agency.[34] As such, major deficiencies identified in a single audit report can affect a Tribe’s eligibility for self-governance compacts, which provide tribal autonomy over administration of federal programs.

Interior and Treasury Track Single Audit Reports from Tribal Entities Awarded COVID-19 Relief Funds, but Treasury Does Not Identify Late or Missing Reports

As part of their oversight responsibilities under the Single Audit Act, Interior and Treasury track the submission of required single audit reports from tribal entities to which they awarded COVID-19 relief funds. Interior has a process for identifying and following up with tribal entities that did not submit a single audit report. Treasury considered several methods for developing such a process but has not yet designed and implemented procedures for identifying tribal entities with late or missing single audit reports and for following up with those entities.

Interior Appropriately Tracks Single Audit Report Submissions from Tribal Entities

Interior designed and implemented procedures to track single audit report submissions from tribal entities and documented these procedures in its Single Audit Report Handbook.[35] To help ensure that tribal recipients submit single audit reports in a timely manner, awarding officials (AO) within IA’s cognizant offices (i.e., BIA, BIE, and OSG) send a letter to each tribal recipient prior to the single audit report due date.[36] The letter informs the tribal recipient of single audit requirements and requests that the recipient submit a single audit report. AOs also request certification statements from those tribal entities that assert that they do not meet the effective expenditure threshold requirement for single audits. When a single audit report or certification statement is received, DIEA staff notes its receipt in its Audit Report Tracking Tool (ARTT).[37] DIEA uses the data in ARTT to track the status of single audit report and certification submissions.

Interior also has appropriately designed procedures for identifying and following up with tribal recipients that did not submit a single audit report or certification statement. DIEA maintains a comprehensive list of tribal entities that have received federal awards from IA cognizant offices.[38] Using the data in ARTT, DIEA is able to determine which tribal entities submitted a single audit report or certification statement, had a late or missing submission, or otherwise were not required to submit a single audit report.[39]

DIEA notifies the AOs of any late or missing single audit reports, and the AOs send letters to tribal recipients reminding them of the single audit requirements and requesting that they submit the late or missing reports.[40] DIEA also sends status reports regarding late or missing single audit reports to AOs, IA cognizant offices, and BIA regional management monthly and to IA leadership, Interior’s Office of Financial Management, and Interior’s National Single Audit Coordinator on a quarterly basis.[41] These status reports help Interior track the effectiveness of its procedures to ensure that single audits are completed and reports are received in a timely manner.

As part of our audit, we obtained a list of tribal entities that received COVID-19 relief funds from Interior and identified those entities that submitted single audit reports to the FAC and DIEA. As shown in table 2, DIEA provided us with the status of single audit report submissions from tribal recipients as of October 31, 2023. Based on our review, we found that Interior’s procedures for tracking single audit report submissions were appropriately designed and implemented.

Table 2: Status of Single Audit Report (SAR) Submissions from Tribal Entities Awarded COVID-19 Relief Funds by the Department of the Interior, Fiscal Years 2020 through 2022, as of October 31, 2023

|

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

Tribal recipients with SAR submissions |

486 |

424 |

248 |

|

Tribal recipients that did not submit a SAR |

68 |

100 |

152 |

|

Certified that SAR submission was not required |

21 |

8 |

3 |

|

Identified as late in submitting SAR or certification |

30 |

82 |

129 |

|

Reported under a tribal consortiuma |

17 |

10 |

20 |

|

Tribal recipients’ SAR submission status not trackedb |

4 |

2 |

4 |

|

Total number of tribal recipientsᶜ |

558 |

526 |

404 |

Legend: DIEA = Division of Internal Evaluation and Assessment

Source: GAO analysis of Interior documents. I GAO‑25‑106741

aTribes that report under a consortium are not required to submit a separate SAR.

bDIEA was not notified by the awarding officials to track recipients. The number of tribal recipients not tracked by DIEA represents less than 1 percent of the total number of tribal recipients.

ᶜTribal recipients included in this table consist of federally recognized Tribes, tribally controlled schools, and tribal organizations to which Interior awarded COVID-19 relief funds.

Treasury Tracks Single Audit Report Submissions but Does Not Identify and Follow Up on Late or Missing Reports

Treasury has procedures to identify the single audit reports that nonfederal entities, including tribal entities, submitted. As noted above, Treasury’s OCA is responsible for monitoring the submission of single audit reports to the FAC. To do so, OCA accesses the FAC website to obtain single audit reporting and finding data and transfers the data to its electronic single audit dashboard.[42] The dashboard is a monitoring tool that contains program and recipient data from the Treasury Recovery Awards Management System and single audit data obtained from the FAC, including the number of single audit reports submitted. Treasury relies on the dashboard to track the submission of single audit reports and identify reports for review.

However, Treasury has not established a process for identifying all tribal recipients that are required to submit a single audit report. Without this information, Treasury has not been able to identify and follow up with all tribal entities that have late or missing single audit reports.

Our analysis of federal award data found Treasury did not track the status of single audit report submissions for a significant number of tribal recipients because it does not have a process to identify whether tribal recipients are required to submit a report. As shown in table 3, for fiscal years 2020 through 2022, the percentage of tribal recipients for which Treasury did not track whether single audit report submission is required ranged from 30 percent to over 45 percent. Because Treasury does not identify tribal recipients that are not required to submit single audit reports, Treasury does not know whether the recipients are late in submitting those reports or not required to do so.

Table 3: Status of Single Audit Report (SAR) Submissions from Tribal Entities Awarded COVID-19 Relief Funds by the Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Years 2020 through 2022, as of October 31, 2023

|

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

Tribal recipients with SAR submissions |

400 |

470 |

248 |

|

Tribal recipients’ SAR submission status not trackedᵃ |

174 |

393 |

164 |

|

Percentage of tribal recipients for which SAR submission status not tracked |

30.3% |

45.5% |

39.8% |

|

Total number of tribal recipientsb |

574 |

863 |

412 |

Source: GAO analysis of Treasury documents. I GAO‑25‑106741

aSAR submission may be late or not required.

bTribal recipients included in this table consist of eligible tribal governments and tribally designated housing entities to which Treasury awarded COVID-19 relief funds. In 2021, Treasury began making awards from the Coronavirus Relief Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside to corporations established pursuant to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that they were eligible tribal governments. See Yellen v. Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation, 594 U.S. 338 (June 25, 2021).

According to Treasury officials, Treasury did not have existing single audit processes when its COVID-19 relief programs were established, and the agency is still developing procedures to fully carry out its single audit responsibilities as a federal awarding agency. Also, Treasury officials stated that maintenance of the FAC transitioned from the U.S. Census Bureau to the General Services Administration in October 2023, creating technological challenges and further delaying Treasury’s efforts toward designing effective processes.

Treasury officials noted that the agency first attempted to use its recipient-reported expenditure data from its Treasury Recovery Awards Management System to identify tribal recipients that reported spending $750,000 or more in COVID-19 relief funds from Treasury programs but had not submitted a single audit report. However, when comparing recipient-reported data to single audit data from the FAC, Treasury noted that limitations with the data prevented it from effectively identifying late or missing single audit reports using an automated process. For example, if a recipient submitted a single audit report to the FAC with a different identification number than the number associated with its Treasury award, Treasury’s automated processes could not match the single audit report with the recipient.

Treasury officials stated that the agency has taken additional steps to identify tribal recipients that were required to submit, but did not submit or may be late in submitting, a single audit report:

· Manual reviews. Treasury has conducted limited manual reviews of recipient-reported expenditures and FAC data to identify Tribes that had failed to submit single audit reports. For example, according to Treasury officials, in January and February 2024, the agency conducted a review of 292 tribal entities awarded funds through one of the COVID-19 relief programs it administers. Based on this review, Treasury identified 41 Tribes that were required to submit a single audit report but had not done so yet. Treasury sent notices of noncompliance to those Tribes.[43] As of July 11, 2024, 8 of those Tribes have come into compliance by submitting a single audit report. Treasury officials stated that replicating this review for all recipients would be burdensome given the number of federal award recipients.

· COVID-19 required reporting. In early 2024, Treasury added questions to required reporting for certain Treasury-administered COVID-19 relief programs, inquiring whether tribal recipients had met the single audit expenditure threshold and submitted a single audit report to the FAC. Treasury is currently assessing how to use information obtained from the questions to identify tribal recipients that are required to submit a single audit report.

· Coordination with Interior. Treasury is planning on entering into a memorandum of understanding with Interior’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs to cooperate and coordinate on the review of tribal government single audit reports. According to the draft memorandum, OCA and Indian Affairs plan to share information regarding, among other things, (1) certifications from tribal entities that they did not spend $750,000 or more in total federal awards and therefore do not meet the effective annual expenditure threshold requirement for completing a single audit and (2) responses from tribal entities regarding late submissions of their single audit reports.

OMB’s single audit guidance states that for the federal awards it makes, the federal awarding agency must ensure that audits are completed and reports are received in a timely manner.[44] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks—such as ensuring the timely submission of single audit reports and providing oversight for federal funds awarded to tribal entities—and implement such activities through policies.[45]

Without effective policies and procedures for identifying tribal recipients with late or missing single audit reports, Treasury cannot reasonably ensure that its federal award recipients have adequate internal controls in place and are complying with program requirements. In addition, tribal entities with late or missing single audit reports will not be complying with OMB’s single audit guidance on report submission; therefore, they may miss opportunities to identify and correct weaknesses in their internal controls in a timely manner.

Interior and Treasury Have Procedures for Reviewing and Following Up on Single Audit Findings, but Do Not Include Key Monitoring Activities

Interior and Treasury have policies and procedures for reviewing and following up on single audit findings, including issuing management decisions on tribal entities’ corrective action plans to address audit findings related to the use of COVID-19 relief funds. Interior appropriately implemented its procedures for issuing management decisions within the required 6-month period consistent with OMB’s single audit guidance.[46] However, Treasury does not issue management decisions within the 6-month period. Interior designed and implemented procedures for establishing most key baselines and targets for tracking single audit findings, but it has not designed procedures for monitoring tribal entities’ repeat single audit findings and tribal entities’ implementation of corrective action plans. Treasury has not implemented certain procedures for following up on single audit findings, including monitoring single audit metrics against targets and baselines and ensuring proper oversight of the metrics by sharing them with Treasury management. Treasury also has not designed and implemented procedures to monitor tribal entities’ implementation of corrective action plans.

Interior Appropriately Designed and Implemented Procedures to Review Single Audit Reports and Issue Timely Management Decisions

Interior appropriately designed and implemented procedures for reviewing tribal entities’ single audit findings and respective corrective action plans, as well as issuing timely management decision letters to tribal entities. Specifically, DIEA staff obtain single audit reports, perform an initial review of the reports, and record report information, including the FAC completion date, in the agency’s ARTT.[47] Based on its review, DIEA staff then draft a memorandum noting any audit findings and questioned costs associated with the reports, among other things. For single audit reports containing audit findings and questioned costs, DIEA staff send the memorandum to the responsible AO, requesting a management decision within 120 days of the FAC completion date, per IA’s guidance.[48] OMB’s single audit guidance states that federal awarding agency must issue management decisions within 6 months (approximately 180 days) of the FAC completion date.[49] According to Interior officials, DIEA can grant an additional 30-day extension to ensure that Interior meets the OMB requirement to issue management decisions within 6 months.

The AO reviews the DIEA memorandum, the single audit report, and the tribal entity’s corrective action plan, if included, to determine if the corrective action plan sufficiently addresses the single audit findings. If the corrective action plan is not sufficient, the AO requests additional information from the tribal recipient before making a final determination. AOs are required to provide technical assistance to tribal entities upon request. After assessing whether the actions taken or proposed by the tribal entity will correct the audit findings, the AO issues a management decision letter to the tribal entity documenting the official’s determination in writing. The AO also notifies the regional director and DIEA director of the AO’s management decisions. Figure 3 illustrates Interior’s process for reviewing tribal entities’ single audit reports and issuing management decisions.

Figure 3: The Department of the Interior’s Process for Reviewing Tribal Entities’ Single Audit Reports and Issuing Management Decision Letters

DIEA staff verify whether the management decision letter (1) was issued within the required time frame, (2) addresses all audit findings and questioned costs, (3) includes a determination on the adequacy of the recipient’s proposed actions to address audit findings, and (4) was signed by the AO. DIEA staff then update ARTT with the management decision date and indicate whether the corrective action plans are adequate to address single audit findings and, if applicable, whether questioned costs were sustained (disallowed) or reinstated (allowed).

Based on our review of 28 management decision letters that Interior issued to tribal entities related to audit findings reported for fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022, we found that Interior generally issued the letters in a timely manner.[50] For example, Interior issued 26 of the 28 management decision letters within the required 6-month period. For the two letters not issued within 6 months, Interior officials explained that the BIA regions responsible for issuing the management decisions did not have AOs at that time. According to Interior officials, the agency has since hired new AOs in those regions and issued the management decisions letters late.

Interior Tracks Single Audit Findings but Does Not Monitor Tribal Entities’ Implementation of Corrective Actions

Interior developed metrics, including baselines and targets, to track the effectiveness of its process for following up on single audit findings. Consistent with OMB’s single audit guidance,[51] Interior implemented procedures requiring DIEA to generate several status reports from information in ARTT and to send these reports to regional directors, AOs, and IA cognizant offices monthly. These reports track (1) overdue management decisions, (2) management decisions coming due, and (3) single audit findings for which management decisions have been issued and disallowed costs need to be collected. Additionally, DIEA prepares and sends quarterly reports to IA leadership, Interior’s Office of Financial Management, and Interior’s National Single Audit Coordinator, summarizing the data in the monthly status reports along with other relevant information.[52]

As part of audit follow-up, OMB’s single audit guidance states that the federal awarding agency must monitor the recipient taking appropriate and timely corrective action.[53] However, we found that Interior is not systematically tracking single audit findings that are repeated from year to year, nor is it tracking the implementation of tribal entities’ corrective action plans proposed in their single audit reports. According to Interior officials, DIEA notes that the single audit review is complete in ARTT after the management decision is issued and AOs have determined that the corrective action plans are sufficient to address the audit findings, even if plans have not been implemented. When there are repeat audit findings, DIEA staff note the repeat findings in the memorandum that is sent to the AOs. However, Interior does not have a procedure that requires AOs to review prior-year audit findings and determine whether prior-year corrective action plans were implemented or why they were insufficient to prevent repeat findings.

Of the 28 fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2022 single audit reports that we reviewed, we found that 12 contained audit findings that were repeated from the previous year, indicating ongoing problems with those tribal entities’ internal controls. Repeat findings could occur because a corrective action was not taken, was not completed, or was ineffective.

Repeat findings can be used to measure the efficiency and effectiveness of an agency’s single audit process. Specifically, if an AO’s management decision finds that a proposed corrective action plan, if implemented, will address the audit findings, then implementation of the plan should result in a reduction in repeat findings.

Because Interior does not systematically track tribal entities’ repeat audit findings or implementation of corrective action plans, the agency is unable to measure the efficiency and effectiveness of its process for following up on audit findings and improving its oversight of federal awards. In addition, uncorrected material and significant audit exceptions related to a self-determination contract or self-governance compact affect a tribal entity’s eligibility for future self-governance compacts.

Treasury Reviews Single Audit Reports but Does Not Issue Timely Management Decisions

Treasury’s OCA has procedures for reviewing single audit reports and issuing management decisions for recipients of its COVID-19 relief funds, including tribal recipients. Specifically, OCA staff retrieve a list of single audit findings from Treasury’s single audit dashboard and prioritize them for review, considering factors such as available resources, OCA-wide priorities, and risk assessment results. Based on this prioritization, OCA staff review the single audit reports and the summary data forms auditors and tribal entities submit with the reports. The staff then use a Single Audit Review Form to document the findings, questioned costs, and their determination as to whether the corrective action plans will address the root causes of the audit findings. Using data from the Single Audit Review Forms, OCA staff draft management decision letters, which contain OCA’s determination regarding whether (1) the corrective action plans are accepted and (2) any questioned costs are allowed or disallowed.[54] Management decision letters undergo various levels of review for data accuracy and consistency, including by Treasury leadership and general counsel. Figure 4 illustrates Treasury’s process for reviewing tribal entities’ single audit reports and issuing management decisions.

Figure 4: Department of the Treasury’s Process for Reviewing Tribal Entities’ Single Audit Reports and Issuing Management Decision Letters

Treasury’s policies and procedures require staff to review single audit findings and issue management decisions within the 6-month time frame required by OMB.[55] However, we found that Treasury has continued to miss deadlines for issuing management decision letters. Of the sample of 30 management decision letters we reviewed related to findings reported for fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022, we found that as of May 22, 2024, none were issued in a timely manner: three management decisions were issued after 6 months, and 27 had not been issued and were considered late.[56] Overall, Treasury officials stated that as of September 30, 2024, the agency has issued 35 of the 294 management decision letters it is required to issue to tribal entities for fiscal years 2020 through 2022.

In a previous audit, we found that Treasury did not promptly issue its management decisions. Specifically, we reported in December 2023 that Treasury did not issue timely management decisions pertaining to State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) findings in recipients’ single audit reports, and as a result, it does not have reasonable assurance that unallowable uses of funds are identified or remediated.[57] In that report, we stated that Treasury officials indicated that the agency faced challenges in implementing systematic reviews of single audit reports and issuing management decisions because it did not have existing single audit processes or staff to administer these processes when the COVID-19 relief programs were established. Treasury officials further stated that they were continuing to assess the backlog of single audit report reviews and other anticipated workload in their development of a plan to continue to resolve single audit findings.

In the December 2023 report, we recommended that the Secretary of the Treasury should issue timely management decisions related to SLFRF findings in accordance with OMB’s single audit guidance. Treasury agreed with the recommendation and stated that reviewing and resolving single audit findings is an important piece of effective federal award administration and monitoring. Treasury officials stated that during 2024, the department has prioritized review of single audits for the recipients with the (1) highest award amounts and (2) questioned costs reported in their single audits.

Treasury uses the same procedures for issuing management decision letters related to SLFRF audit findings as those for issuing management decision letters related to other COVID-19 relief funds findings. If Treasury takes steps to issue management decisions letters related to SLFRF audit findings, these actions should result in the timely issuance of management decisions letters for other COVID-19 relief fund findings, including tribal entities’ findings. As such, prompt implementation of our December 2023 recommendation is critical. Until Treasury issues timely management decisions, tribal recipients may be unclear about the agency’s position on the single audit findings and whether the proposed corrective actions will address the findings. Additionally, there is an increased risk that potential audit findings related to unallowable uses of program funds, including COVID-19 relief funds, may remain unidentified and uncorrected for significant periods of time.

Treasury’s Procedures Require Monitoring of Single Audit Metrics, but Baselines, Targets, and Oversight Could Be Improved

Treasury’s Single Audit Procedures requires the agency to collect data on single audits for recipients of Treasury-administered funds and monitor its progress against certain metrics. These metrics include the (1) percentage of single audits with no audit findings, (2) percentage of single audits with audit findings, (3) percentage of repeat single audit findings, and (4) timely issuance of management decision letters. These procedures also require Treasury to evaluate its performance data annually, revising and recalibrating measures as needed.[58]

We found that although Treasury reports metrics in its single audit dashboard, it does not use the metrics as described in its policies and procedures to monitor its progress. Specifically, according to Treasury officials, there are currently no baselines or targets associated with the metrics, and there are no documented procedures to regularly share the metrics with management, including OCA’s Chief Operating Officer. Additionally, we found that Treasury’s procedures do not require the agency to report metrics regarding tribal recipients’ implementation of corrective action plans. According to Treasury officials, the agency has prioritized addressing its backlog of management decision letters and OCA staff meet regularly to track progress on and discuss single audit reviews and issuance of the letters. Treasury officials stated that they will review the baselines and targets for Treasury’s single audit process after it has issued a greater proportion of management decisions letters.

OMB’s single audit guidance requires the monitoring of the recipient taking appropriate and timely corrective action, the development of baselines and targets to track the effectiveness of the process to follow up on audit findings, and that an official be held accountable for improving the effectiveness of the single audit process based on these metrics.[59] Also, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. Control activities include, for example, management comparing actual performance to planned or expected results throughout the organization and analyzing significant differences.[60]

If Treasury does not use metrics to monitor whether tribal recipients are implementing corrective action plans, it cannot reasonably ensure that the recipients are taking appropriate and timely action to correct single audit findings as required by OMB’s single audit guidance.[61] In addition, if single audit findings are not corrected, tribal entities may miss opportunities to improve their financial stability and management capability. Also, without baselines and targets for single audit process metrics and adequate oversight of these measures, as required by OMB’s single audit guidance,[62] Treasury may not identify opportunities to improve the effectiveness of its single audit process.

Interior and Treasury Reported Assisting Tribal Entities throughout the Single Audit Process

Interior and Treasury assist tribal recipients of COVID-19 relief funds in navigating the single audit process. Both agencies reported using various methods to help tribal recipients comply with single audit requirements and prevent future audit findings. The representatives from tribal-serving organizations and the tribal official who we interviewed provided their perspectives on the agencies’ assistance, including opportunities for these agencies to enhance the assistance they provide to tribal recipients.

Interior and Treasury Single Audit Assistance for Tribal Entities

Interior’s Tribal Assistance

Interior uses various methods to help tribal recipients comply with requirements for single audits and COVID-19 relief funds. For example, IA provided webinars on topics such as allowable uses of COVID-19 relief funds and single audit requirements. In addition, Interior provided information on its website to assist tribal entities with COVID-19 relief funds management.[63] Specifically, Interior’s website provides information about BIE virtual listening sessions, Coronavirus Relief Fund guidance for tribal governments, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, and upcoming tribal consultations. IA also issued notifications on its website to tribal recipients regarding the use of COVID-19 relief funds.

AOs provide technical assistance upon request to tribal recipients during the single audit review, in accordance with Interior’s Single Audit Report Handbook.[64] According to Interior officials, some of this assistance includes explaining single audit findings and related disallowed costs to tribal recipients, helping recipients determine the source or root cause of issues leading to audit findings, providing suggestions to address the root causes, and helping recipients develop corrective action plans to address single audit findings, as needed. AOs may also provide administrative or other miscellaneous assistance upon request. Examples of such assistance include copies of documentation, such as contracts and financial status reports; reviews of payments provided through certain Interior programs; and help creating property inventory lists.

According to Interior officials, DIEA only provides direct assistance to tribal entities when requested by the AOs or education program administrators. DIEA’s assistance is provided through meetings, correspondence, and training.

Interior officials told us the agency also helps tribal recipients prevent future audit findings. It does so by working directly with tribal entities to resolve prior audit findings and provide technical assistance to avoid future findings. For example, if a tribal entity is in reassumption, IA provides targeted technical assistance, which involves recurring meetings to identify progress and on-site visits with the recipient to ensure that any relevant corrective action plans are being implemented.[65] IA also continues to provide training and webinars to tribal recipients on financial reporting and single audits to help prevent future audit findings.

Treasury’s Tribal Assistance

Treasury helps tribal recipients comply with COVID-19 relief fund and single audit requirements in a variety of ways. For example, OCA provides single audit advice and counsel to Treasury’s recipients and their auditors, in accordance with OCA’s Single Audit Procedures.[66] Treasury also publishes a variety of program-specific compliance materials online for recipients, such as SLFRF user guides.[67] Additionally, Treasury makes presentations at tribal events and conferences and provides informational and training webinars for tribal recipients on topics such as single audit compliance and accounting best practices. Treasury also operates a call center to answer award recipients’ questions, including tribal recipients, regarding COVID-19 relief programs.

Treasury’s OCA and Office of Tribal and Native Affairs (OTNA) are responsible for providing a range of single audit support to tribal entities. According to Treasury officials, OTNA offers guidance to tribal entities, including information sessions, one-on-one discussions, and training for compliance and support. For example, according to Treasury, OTNA conducted 389 one-on-one discussions with tribal entities on specific issues in 2023. In addition, OTNA facilitated on-site training for tribal governments in Anchorage and Kotzebue to improve the likelihood that tribal recipients in Alaska will submit required reporting for SLFRF and the Coronavirus Relief Fund Tribal Government Set-Asides. According to Treasury officials, in August 2024, OTNA is partnering with Interior and the Alaska Federation of Natives to host a webinar for Alaska Native Villages focused on undergoing a single audit for the first time. OTNA also publishes a weekly newsletter containing high-level information on Treasury tribal matters, compliance and reporting requirements for COVID-19 relief programs, and overviews of the single audit process, among other things.

OTNA may engage with tribal entities, as needed, when issues arise from more complex single audit findings. For example, according to Treasury officials, OTNA identified the lack of access to reliable, high-speed internet as the principal cause of prevalent single audit findings related to late or missing annual and quarterly reports required under certain COVID-19 relief programs.[68] They also told us that OTNA worked with OCA to develop a method for tribal entities to submit paper reports as an alternative to electronic reports to help reduce the prevalence of this audit finding.

According to Treasury officials, the agency is also working to help tribal entities prevent future audit findings. For example, Treasury partnered with the Department of Health and Human Services, the Executive Office of the President, and Interior to research and report on ways to improve technology and address knowledge gaps with the goal of increasing tribal recipients’ compliance with the terms and conditions of federal awards and reducing burden for tribal recipients. The report was issued in June 2024 and identified key needs of Tribes.[69]

Treasury officials also noted that guidance, training, and one-on-one engagement with tribal recipients are intended to help tribal entities prevent future audit findings. For example, Treasury officials noted that the agency provided targeted one-on-one trainings to tribal governments that did not perform required annual or quarterly program reporting or submitted incorrect reports for COVID-19 relief programs.

Tribal Perspectives on Single Audit Assistance

We interviewed representatives from three tribal-serving organizations and a tribal official to obtain their perspectives on Treasury and Interior’s single audit assistance. They discussed (1) Treasury’s and Interior’s improved capacity for assistance since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) tribal entities’ unique needs and challenges encountered throughout the single audit process, and (3) suggestions for Treasury and Interior to further enhance assistance.

Improved capacity for assistance. According to the representatives from the tribal-serving organizations and the tribal official we interviewed, Interior and Treasury have improved their capacity to provide technical assistance to tribal recipients since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, both Interior and Treasury provided resources related to federal funding and overall federal guidance. One tribal-serving organization noted that Interior publicly posted its Single Audit Report Handbook,[70] which outlines its single audit review process and noncompliance remedies, in October 2021. In addition, in March 2024, we reported that most tribal schools funded by BIE reported that they received guidance on COVID-19 relief spending that was timely, useful, and clear.[71]

One tribal-serving organization noted that one-on-one engagement with agency officials was helpful because tribal entities receive more clear and concise guidance when they have direct, long-term connections with federal agencies. A tribal official noted that Interior’s OSG has provided one-on-one assistance to help the Tribe with writing corrective action plans. The official also stated that Treasury has provided helpful guidance through FAQs, webinars, and a presentation at a conference for tribal finance staff. Also, all representatives from tribal-serving organizations and the tribal official we interviewed noted that when Treasury established OTNA in September 2022, Treasury’s guidance and assistance to tribal entities were enhanced.

Tribal entities’ unique needs and challenges. While Interior and Treasury assist tribal entities throughout the single audit process, representatives from the tribal-serving organizations and the tribal official who we interviewed noted that the assistance provided may not fully consider the unique needs and challenges of tribal recipients. According to one of the tribal-serving organizations, for example, it is often difficult for tribal entities to know what general guidance applies to their specific situation when preparing for single audits or developing corrective actions to address audit findings. This tribal-serving organization indicated that the webinars and online information provided by federal agencies tend to be high level, outlining information such as auditee and auditor responsibilities.

Tribal governments also differ in size and resources. While smaller Tribes may have one to two staff members, who may lack the specialized knowledge needed to meet single audit requirements, other Tribes may have large accounting departments. For example, one tribal-serving organization stated that a Tribe did not have a certified public accountant in its accounting division or staff with knowledge of the single audit process. In such cases, tribal entities told us, tribal staff may not know where to look for single audit information and may find it difficult to keep up with changes in guidance on allowable uses of award funds and single audit reporting requirements.

In December 2022, we reported that tribal recipients had to spend more time and effort determining which requirements applied for audit compliance, as agencies repeatedly modified guidance or provided additional information about COVID-19 relief funding requirements. In that report, one tribal recipient specifically noted challenges caused by Treasury releasing many iterations of its Coronavirus Relief Fund guidance on the use of funds.[72]

One tribal-serving organization noted that many Tribes and tribal organizations, particularly those on reservations or in remote areas, have unreliable access to the internet and may have trouble contacting federal agencies for assistance or meeting single audit reporting requirements. In October 2021, we reported that Tribes noted that internet connectivity issues affected their ability to meet a COVID-19 relief funding program compliance reporting deadlines.[73]

Tribal-serving organizations’ suggestions for improvement. Generally, the representatives of tribal-serving organizations we interviewed noted that Interior and Treasury continued to improve their assistance to tribal recipients since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. These tribal-serving organizations also provided suggestions for improvement. For example, one organization suggested that the agencies provide (1) clear, realistic examples of what tribal entities should do during each step of the single audit process, including how the process may differ based on variables such as Tribe size and income level, and (2) general information, in the form of FAQs, to help nonexperts more easily begin the process of learning about single audits.

Another tribal-serving organization suggested that regional technical assistance offices be established, and that each Tribe be assigned to one. This organization also noted that it would have been helpful for federal agencies to provide tribal entities with consistent guidance and information on the types of projects that Tribes could do upon receipt of the federal award.

Conclusions

Through the COVID-19 relief laws, the federal government provided billions of dollars in critical assistance to tribal entities to help them respond to the pandemic. In many cases, smaller tribal entities received substantial amounts of funding and became subject to single audit reporting requirements for the first time. Federal awarding agencies, such as Interior and Treasury, must do their part to ensure accountability for these funds, including reviewing single audits, issuing management decisions, and monitoring recipients’ corrective actions.

Both Interior and Treasury have processes for obtaining the relevant single audit reports. Interior has a process for identifying and following up with tribal entities that did not submit a report. However, Treasury is in the process of assessing procedures for identifying and following up with tribal entities that have late or missing single audit reports but has not yet formalized and incorporated such procedures. By developing and implementing policies and procedures to identify and follow up with tribal recipients that did not submit required single audit reports when due, Treasury could better assure that it is meeting its oversight responsibilities.

Interior and Treasury review single audit findings and issue management decisions on the adequacy of tribal entities’ corrective action plans to address findings related to the use of COVID-19 relief funds, but Treasury failed to issue timely management decisions. As such, prompt implementation of our December 2023 recommendation is critical to ensure that any potential findings are corrected timely. In addition, both Interior and Treasury could improve their procedures for tracking the effectiveness of their single audit processes by monitoring the implementation of tribal entities’ corrective action plans. Designing and implementing procedures are key to Interior and Treasury ensuring that tribal entities identify and correct weaknesses in their internal controls in a timely manner. Strong internal controls can help tribal entities ensure that they spend federal award funds on allowable uses, maintain accurate and reliable financial data, and comply with applicable laws or regulations. In turn, by correcting single audit deficiencies, Tribes may improve their financial stability and financial management capability. Further, these corrections would help Tribes become eligible for self-governance compacts that provide the greatest autonomy over the design and administration of federal programs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of three recommendations, including two to Treasury and one to Interior. Specifically:

The Secretary of the Treasury should develop and implement procedures to identify tribal recipients that did not submit required single audit reports when due and follow up with those recipients. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Interior should develop and implement procedures for tracking the implementation of corrective action plans, including tracking repeat single audit findings, to ensure that tribal recipients take appropriate and timely action to correct single audit findings. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Treasury should develop and implement procedures to use metrics to improve the effectiveness of Treasury’s process for following up on audit findings, including developing baselines and targets, tracking the implementation of corrective action plans, and sharing the metrics with OCA’s Chief Operating Officer. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to Interior and Treasury for review and comment. We received written comments from Interior and Treasury that are reproduced in appendixes III and IV, respectively, and summarized below. Interior and Treasury also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In their comments, Interior and Treasury agreed with our recommendations. With regard to recommendation 1, Treasury stated that it will implement a process to identify Tribal recipients that failed to submit required single audits using interagency information sharing and recipient-reported data. Treasury noted that it plans to enter into a memorandum of understanding with Interior’s Indian Affairs to share single audit information, including tribal governments’ certifications as to whether they or their tribal entities are required to conduct a single audit. Treasury said that it will use its existing processes to follow up with recipients identified through this process. The actions that Treasury described, if implemented effectively, would address this recommendation.

With regard to recommendation 2, Interior noted that it will update its policies and procedures to include requirements that staff monitor the status of tribal entities’ single audit corrective action plans, including their implementation, and close out single audit findings when corrective action plans are implemented. Interior also noted that, as part of its updated policies and procedures, it will develop a new process of tracking and monitoring repeat single audit findings. The actions that Interior described, if developed and implemented effectively, would address this recommendation.

With regard to recommendation 3, Treasury noted that it will implement monthly status reports for management, including OCA’s Chief Operating Officer, that will track (1) overdue management decisions, (2) management decisions coming due, (3) status of management decisions issued, and (4) status of disallowed costs or prior period reporting adjustments. The actions that Treasury described, if implemented effectively, would not fully address this recommendation. To do so, Treasury will also need to develop baselines and targets and track the implementation of corrective action plans.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of the Interior, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staffs have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7795 or sitwilliamsa@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Anne Sit-Williams

Director

Financial Management and Assurance

List of Committees

The Honorable Patty Murray

Chair

The Honorable Susan Collins

Vice Chair

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Chairman

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Chair

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Tom Cole

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Cathy McMorris Rodgers

Chair

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

Since March 2020, COVID-19 relief laws have appropriated at least $43.6 billion for federal programs serving Tribes, tribal citizens, and tribal organizations.[74] These laws provided assistance to Tribes and other tribal entities, as well as tribal citizens, by creating several new COVID-19 relief programs, making appropriations for those new programs, and providing appropriations for existing programs. For example, the Department of the Interior and the Department of the Treasury awarded $32.7 billion in COVID-19 relief funding to tribal entities through existing programs, such as Interior’s Aid to Tribal Governments, and new programs, such as Treasury’s Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside. Table 4 contains detailed information on the COVID-19 relief funding that these departments administered. This table does not include appropriations that were made to other federal agencies and subsequently transferred to Interior and Treasury.

Table 4: COVID-19 Relief Funding for Eligible Tribal Entities Administered by the Departments of the Interior and the Treasury

|

Department |

Agency/ office |

Appropriation |

Legal authority |

Eligible recipients |

Amount (in dollars)ᵃ |

|

Interior |

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

|

Bureau of Indian Affairs |

American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), § 11002 |

Tribes, tribal organizations, and BIA |

$900 million |

|

Operation of Indian Programs |

CARES Act, div. B, tit. VII |

Tribes, tribal organizations, and BIA |

$453 million |

||

|

Bureau of Indian Education (BIE)

|

Bureau of Indian Education |

ARPA, § 11005 |

Tribes, tribal organizations, tribal colleges and universities, and BIE |

$850 million |

|

|

Operation of Indian Education Programs |

CARES Act, div. B, tit. VII |

Tribes, tribal organizations, tribal colleges and universities, and BIE |

$69 million |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treasury |

Office of Capital Access

|

Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside |

ARPA, § 9901 |

Tribal governmentsᵇ |

$20 billion |

|

Coronavirus Relief Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside |

CARES Act, § 5001 |

Tribal governmentsᶜ |

$8 billion |

||

|

Emergency Rental Assistance 1 Tribal Community Set-Aside |

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, div. N, § 501 |

Tribes, eligible tribally designated housing entities, and the Department of Hawaiian Homelands |

$800 million |

||

|

State Small Business Credit Initiative Tribal Government Allocationd |

ARPA, § 3301 |

Tribal governmentsᵉ |

$500 million |

||

|

Homeowner Assistance Fund Tribal Set-Aside |

ARPA, § 3206 |

Tribes, eligible tribally designated housing entities, and the Department of Hawaiian Homelands |

$498 million |

||

|

Local Assistance and Tribal Consistency Fund Tribal Government Set-Aside |

ARPA, § 9901 |

Tribal governmentsf |

$500 million |

||

|

Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund for Tribal Governments |

ARPA, § 9901 |

Tribal governmentsg and the State of Hawaii |

$100 million |