NAVY SHIP MODERNIZATION

Poor Cruiser Outcomes Demonstrate Need for Better Planning and Quality Oversight in Future Efforts

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106749. For more information, contact Shelby S. Oakley at (202) 512-4841 or OakleyS@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106749, a report to congressional committees

Poor Cruiser Outcomes Demonstrate Need for Better Planning and Quality Oversight in Future Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

In 2012 and 2013, the Navy proposed retiring several cruisers due to budget constraints. Congress rejected the Navy’s proposal and provided funding to modernize these ships. In response, the Navy planned to use a phased approach to modernization that would extend 11 cruisers’ service life by 5 years and upgrade the vessels’ combat capability. The Navy originally planned to complete all 11 cruisers by fiscal year 2026. The Navy has other upcoming significant surface ship modernization efforts, such as for 23 destroyers. The success of these efforts is critical to the Navy having a combat-ready fleet.

A Senate report included a provision for GAO to assess the Navy’s cruiser modernization. This report assesses, among other things, the extent to which (1) the Navy met its modernization objectives; (2) the Navy’s planning affected outcomes; and (3) the Navy exercised effective quality control and oversight of the effort. To do this work, GAO toured five cruisers undergoing modernization, interviewed over 100 Navy officials, compared actual versus planned cost and schedule data, and reviewed Navy documentation and prior GAO reports related to Navy shipbuilding and repair.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including that the Navy assess root causes of unplanned work, develop mitigation strategies, and codify these strategies in policy; and re-assess its overall approach to quality assurance to prevent similar issues in future surface ship modernization efforts. The Navy concurred with all six recommendations.

What GAO Found

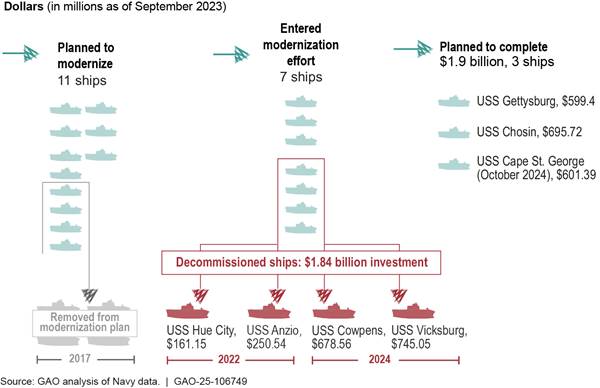

Since 2015, the Navy has spent about $3.7 billion modernizing seven of the Ticonderoga class guided-missile cruisers—large surface combatants that provide key air defense capabilities. However, only three of the seven ships will complete modernization, and none will gain 5 years of service life, as intended. The Navy wasted $1.84 billion modernizing four cruisers that have now been divested prior to deploying. The Navy also experienced contractor performance and quality issues across the cruiser effort. For example, the contractor performed poor quality work on USS Vicksburg’s sonar dome—a critical element of the Anti-Submarine Warfare mission area—resulting in additional cost and schedule delays due to necessary rework.

The Navy did not effectively plan the cruiser effort. This led to a high volume of unplanned work–9,000 contract changes–resulting in cost growth and schedule delays. The Navy has yet to identify the root causes of unplanned work or develop and codify root cause mitigation strategies to prevent poor planning from similarly affecting future surface ship modernization efforts.

Further, weakened quality assurance tools restricted the Navy’s ability to hold contractors accountable for poor quality work. In 2018, leadership restricted maintenance officials from assessing monetary penalties to contractors without senior leadership approval. In 2020, leadership changed procedures to reduce inspections, which are a vital tool for overseeing ship repair contracts, by almost 50 percent. These actions were implemented to maintain strong working relationships with the contractors because of the Navy’s dependence on them to modernize its fleet, according to Navy officials. Without reassessment, the Navy risks experiencing similar negative outcomes in future modernization efforts.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CAR |

Corrective Action Request |

|

CNO |

Chief of Naval Operations |

|

CNRMC |

Commander, Navy Regional Maintenance Center |

|

CPARS |

Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System |

|

DDG |

Guided-Missile Destroyer |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

JFMM |

Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual |

|

MARMC |

Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center |

|

NAVSEA |

Naval Sea Systems Command |

|

NAVSEA 21 |

Naval Sea Systems Command, Surface Ship Maintenance, Modernization, and Sustainment |

|

NMD |

Naval Maintenance Database |

|

NRMO |

Naval Sea Systems Command, Regional Maintenance Offices |

|

NWRMC |

Northwest Regional Maintenance Center |

|

OPNAV |

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations |

|

OPNAV N96 |

Chief of Naval Operations, Surface Warfare |

|

QASP |

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan |

|

RCC |

Request for Contract Change |

|

RMC |

Regional Maintenance Center |

|

SURFMEPP |

Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program |

|

SWRMC |

Southwest Regional Maintenance Center |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 17, 2024

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chairman

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rodgers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

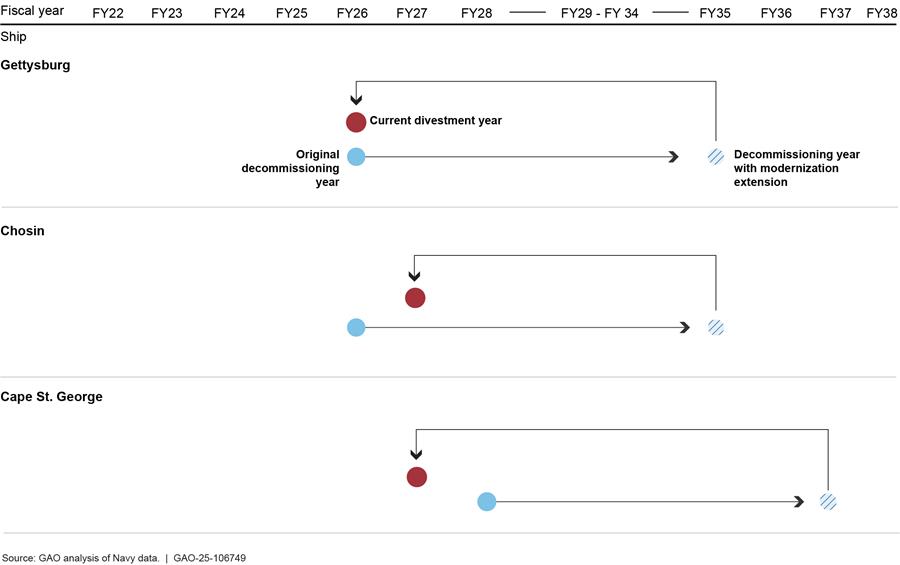

From 2015 through fiscal year 2023, the Navy spent about $3.7 billion modernizing seven Ticonderoga class guided-missile cruisers. Through the cruiser modernization effort, the Navy intended to extend the service lives—or lifespans—of 11 cruisers while also providing the ships with warfighting upgrades. The Navy planned to achieve this modernization through 4-year work periods on each ship over a 10-year period for all 11 ships. The work periods involved extensive maintenance and modernization work, including maintenance work on the ships’ hulls and modernization work to upgrade the ships’ guns and combat systems. But nearly 10 years later, only one of the ships has deployed and the Navy plans to divest the remaining cruisers by fiscal year 2027.

Cruisers are large surface combatants that primarily fulfill the Air and Missile Defense Commander role, which involves coordinating the use of valuable air defense assets to protect U.S. and ally ships. Since technology needs to be refreshed often and the United States industrial base is limited in the number of ships it can build, modernizing ships successfully is critical to maintaining and increasing the fleet size to 355 ships in accordance with Navy plans.

In the coming decade, the Navy is planning additional significant surface ship modernizations. These include an effort costing more than $10 billion to modernize 23 of the Navy’s destroyers (DDG) at some of the same ship repair yards that executed cruiser modernization. The Navy is planning additional multi-billion-dollar efforts to maintain and modernize many of its 32 amphibious ships. Modernization efforts can vary but are critical for updating ships. Our past work has found that the Navy has experienced substantial sustainment challenges across the fleet, including ship repair delays, degraded materiel condition, and a significant maintenance backlog.[1]

The Senate Armed Services Committee report accompanying the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for us to assess the Navy’s cruiser modernization.[2] This report assesses the extent to which (1) the Navy met its objectives for cruiser modernization; (2) the Navy’s planning affected cruiser modernization outcomes; (3) the Navy exercised effective quality control and oversight of cruiser modernization; and (4) the Navy extended the cruiser service lives as planned and considered the benefits, costs, and risks of decommissioning the cruisers that will complete modernization.

To answer all four objectives, we toured the five cruisers undergoing modernization as of September 2023. As discussed in this report, two additional cruisers were dropped from the modernization effort in 2022. We also interviewed over 100 officials across relevant Navy offices.

To assess the extent to which the Navy met its objectives for cruiser modernization, we compared cost and schedule data as of September 30, 2023, to the Navy’s planned cost and schedule objectives at the start of cruiser modernization. To identify quality of work on the ships, a critical element of completing each ship’s modernization, we reviewed Navy data on quality, such as corrective action requests and contractor performance assessment reports, and interviewed maintenance officials and ships’ crew on quality issues.

To assess how planning affected cruiser modernization outcomes, we reviewed the steps that the Navy took to gather information about the condition of the cruisers and to plan cruiser modernization. For example, we reviewed documentation of pre-modernization surveys that were conducted by the Navy to identify the condition of the ships that the Navy planned to modernize. We also analyzed requests for contract change and growth work data.

To assess the extent to which the Navy exercised effective quality control and oversight, we reviewed contracts, contract performance data, and documentation of Navy oversight of cruiser modernization. We compared these to Navy policy for maintenance and modernization and relevant portions of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR).

To assess the extent to which the Navy extended the cruisers’ service lives as planned and considered the benefits, costs, and risks of decommissioning the cruisers, we evaluated the Navy’s analyses based on existing requirements outlined in Navy policy on decommissioning Navy vessels. We also assessed the Navy’s analyses against GAO’s Assessment Methodology for Economic Analysis which provides guidance on conducting cost benefit analysis.[3]

Additional details about our scope and methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Cruisers carry out several missions, such as defending aircraft carriers, launching missiles to strike maritime and land targets, and patrolling sea lanes. Some cruisers are also capable of providing ballistic missile defense. Further, the cruiser is the Navy’s only purpose-built air defense platform designed to perform the Air Defense Commander role. The Air Defense Commander is responsible for coordinating air defense for carrier strike groups, and the cruisers are more equipped to perform this function than any other ship class. The lead Ticonderoga class ship was first commissioned in 1983. The Navy has since commissioned 27 cruisers, with each ship having an estimated 35-year service life. Figure 1 shows USS Gettysburg, a cruiser that was commissioned in 1991.

Navy Stakeholders Involved in Overseeing Cruiser Modernization

As previously mentioned, the overall cruiser modernization effort requires both maintenance and modernization. These types of work—maintenance or modernization—are funded through different categories of Navy funding.[4] Maintenance includes, for example, structural or mechanical repairs, whereas modernization involves upgrades to a ship’s capabilities. In this report, we refer to the overall modernization effort, including maintenance and modernization, as the “cruiser modernization effort.”

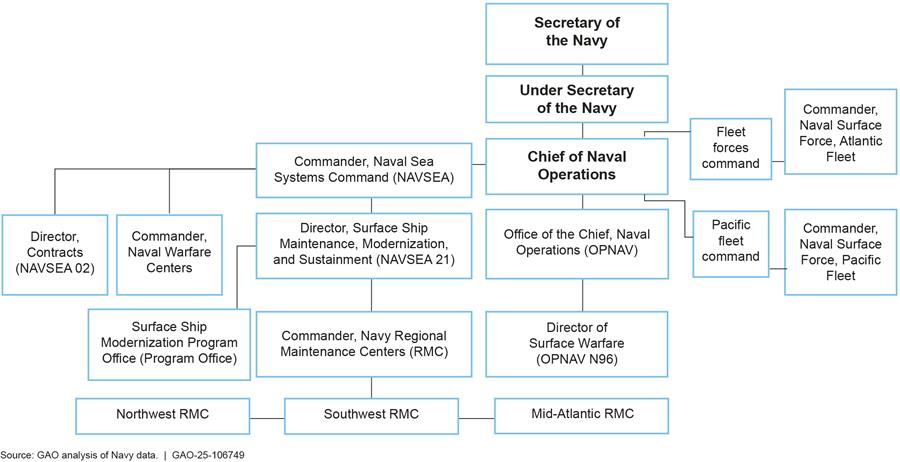

The cruiser modernization effort’s oversight and management are unique compared to how the Navy typically oversees other surface ship maintenance and modernization. When each ship was inducted into or entered cruiser modernization, the control and responsibility of the ship—along with responsibility for allocating and disbursing funding—was transferred from the fleet (Surface Forces Atlantic or Surface Forces Pacific) to Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA). Control of the ships was transferred back to the fleet midway through each ship’s modernization, but NAVSEA remained responsible for completing the modernization effort, according to Navy officials. For other surface ships, the fleet maintains control and responsibility of the ship going through maintenance. This can include modernization, and overseeing funding, whereas NAVSEA is primarily responsible for providing system expertise as well as contract award and administration. Figure 2 outlines the various stakeholders that oversee and manage cruiser modernization.

Figure 2: Organizational Chart for Navy’s Cruiser Modernization Effort

NAVSEA and its subordinate organizations help maintain ships to meet fleet requirements within cost and schedule goals, among other duties.

· Director, Surface Ship Maintenance, Modernization, and Sustainment (NAVSEA 21) manages life-cycle support for all nonnuclear surface ships and is responsible for the depot-level maintenance and modernization of surface ships operating in the fleet.[5] NAVSEA 21 has ownership of the cruiser modernization ships, meaning NAVSEA 21 has the overall technical, acquisition, and execution authority of cruiser modernization.

· Surface Ship Modernization Program Office (Program Office) leads and integrates all surface ship modernization policy, planning, and execution. The Program Office is responsible for various cruiser modernization oversight elements, including program management and requesting, allocating, and disbursing Chief of Naval Operations funds.[6]

· Commander, Navy Regional Maintenance Center (CNRMC) oversees the Navy’s Regional Maintenance Centers (RMC) in their administration of surface ship contracts for maintenance and modernization of ships.

o The RMCs administer and are responsible for the day-to-day oversight of the contracts the Navy uses to maintain and modernize ships. RMCs involved in the cruiser modernization effort include Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center (MARMC) in Norfolk, Virginia, Southwest Regional Maintenance Center (SWRMC) in San Diego, California, and the Northwest Regional Maintenance Center (NWRMC) in Everett, Washington.

· Commander, Naval Warfare Centers provide technical expertise and support for the Navy’s ships and systems. For certain modernization elements, the Warfare Centers oversee the Navy’s use of modernization teams. The government supervises and a contractor manages modernization teams responsible for installing ship alterations, such as a communications system upgrade. The modernization team’s work should be integrated into the ship repair yard’s maintenance period schedule, according to the Navy’s Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual.[7]

· NAVSEA Contracts awards contracts for large and complex ship repair and modernization periods, while the RMCs administer them.

Office of Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) is the senior military officer of the Department of the Navy, overseeing the Navy’s fleet, among other organizations.

· Office of the Chief of Naval Operations Surface Warfare Director, (OPNAV N96) is the requirements and resource sponsor for the maintenance and modernization of cruisers undergoing modernization.

· Operational Fleet Forces (fleet) of the Navy, including the fleet commands (Surface Forces Atlantic and Surface Forces Pacific), typically assume full responsibility for operating and maintaining ships. Port Engineers work for the fleet and are responsible for the maintenance of their assigned ships. The fleet does not have a significant role with developing and installing systems associated with major modernization efforts. As mentioned above, control of the cruisers was transferred away from the fleet for cruiser modernization and then back to the fleet midway through the ships’ modernization period, which we discuss later in the report.

Types of Ship Maintenance and Modernization

The Navy contracts with private shipyards—which are part of the ship repair industrial base—for the maintenance and modernization of non-nuclear surface ships. Certain types of work, such as repairing a ship’s hull, might require placing a ship in the ship repair contractor’s dry dock.[8] Ship maintenance and modernization work time frames can range from a few weeks to years depending on the extent and complexity of the work required. The types of maintenance periods, which also include modernization work, include the following:

CNO maintenance periods. The Navy’s most intensive maintenance and modernization periods are called CNO availabilities. In this report, as a broad term we refer to CNO availabilities as CNO maintenance periods. The Navy accomplishes major repair work—known as depot-level maintenance and modernization—during these periods. This level of work requires complex processes to complete restorative work, such as structural, mechanical, and electrical repairs. These may include modernization work to upgrade a ship’s capabilities and extend the ship’s service life.

Continuous maintenance periods. These maintenance periods accomplish non-major repair work, which includes routine maintenance work requiring relatively little time compared to CNO maintenance periods—typically only weeks to a few months in duration.[9]

Contracting Approach

The Navy began to award the cruiser modernization contracts as it transitioned its ship repair and modernization contracts from cost-type contracts to firm-fixed-price contracts. Under cost-type contracts, the government pays allowable costs incurred by the contractor, to the extent prescribed by the contract. Firm-fixed-price contracts provide for a price that is not subject to any adjustments regardless of the contractor’s cost experience. The Navy implemented this change in 2015 as part of a strategy to address widespread cost and schedule challenges related to ship maintenance. Under the new strategy, contracting opportunities for maintenance periods that the Navy expects to last more than 10 months are not restricted to vendors in the ship’s home port and are often competed among interested shipbuilders located on the same coast as the ship’s home port.

Cruiser Modernization Strategy

In 2012, the Navy decided to divest seven cruisers and two dock-landing ships due to budget constraints, according to Navy officials.[10] However, Congress did not support the Navy’s decision and provided funds to maintain, operate, and sustain the ships in the fleet. In March 2014, as part of the President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2015, the Navy proposed a Phased Modernization Plan that included placing 11 Ticonderoga class cruisers into a phased modernization and maintenance period to reduce near-term funding requirements and as a means to extend the life of these ships. According to Navy officials, the Navy did not consider any formal alternatives to the original Phased Modernization Plan submitted as part of the President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2015. Navy officials stated that the Navy’s Phased Modernization Plan evolved after Congress rejected the Navy’s earlier proposal to divest nine ships, and that there were discussions held to determine the best plan. According to Navy officials, because Congress did not approve its Phased Modernization Plan, the Navy made further modifications to the plan and adopted the “2-4-6” strategy, which the officials believe is consistent with congressional intent.

Under this strategy, the Navy planned to modernize a total of 11 cruisers over 10 years by

· inducting no more than 2 cruisers each year into modernization cycles,

· for up to 4 years in modernization, and

· with no more than 6 cruisers undergoing modernization at the same time.

To save on crew costs, the Navy inactivated, but retained in commission, the seven ships that entered the cruiser modernization effort. The Navy continued to count these ships toward fleet size but reduced the crew on each ship from generally over 350 sailor billets allowed to a 45-sailor caretaker crew. To maintain the ship with a caretaker crew, officials told us that the Navy had to preserve the ship, which included taking actions such as draining the lube oil from the propulsion system and replacing it with a preservative. The Navy’s strategy was unusual, as a ship going through maintenance or modernization typically would not have its crew significantly reduced or be inactivated, according to Navy officials. According to Navy guidance, midway through the modernization period for each ship, the Navy was to increase the number of crew back to the full billets, generally around 350, to help reactivate the ship.

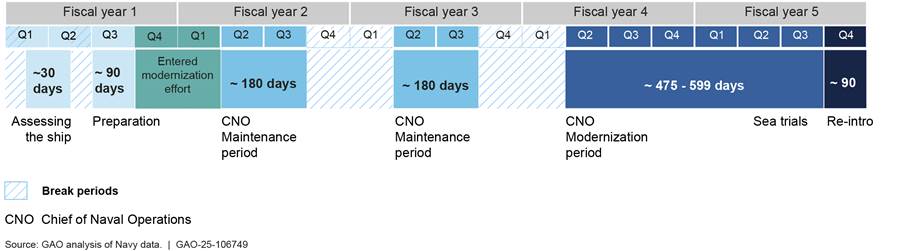

Cruiser Modernization Approach

Cruiser modernization consisted of several maintenance periods. For a given cruiser, following a 90-day preparation period, the cruiser entered the modernization effort.[11] At that point, the ownership of the ships was transferred from the fleet to NAVSEA 21. This started the planned 4-year time frame for modernization.

As part of the modernization effort each ship was planned to go through one or two 180-day CNO maintenance periods. These were followed by a CNO dry dock maintenance period with an expected duration of about 1.5 years, during which most of the modernization work was to be accomplished. For purposes of this report, we will refer to this dry dock maintenance period as the “modernization period.” The Navy planned for a break in between each of the periods to ensure that the modernization effort for each ship spanned 4 years, according to officials. Figure 3 represents an example of the planned maintenance periods for a cruiser undergoing modernization. The Navy planned for each ship’s modernization and the 4-year time frame to conclude with sea trials, typically conducted after major work is done on a ship.

The Navy generally contracted for each cruiser’s maintenance and modernization periods separately.[12] The contractor location determines which RMC is responsible for administering the contracts and conducting quality assurance.

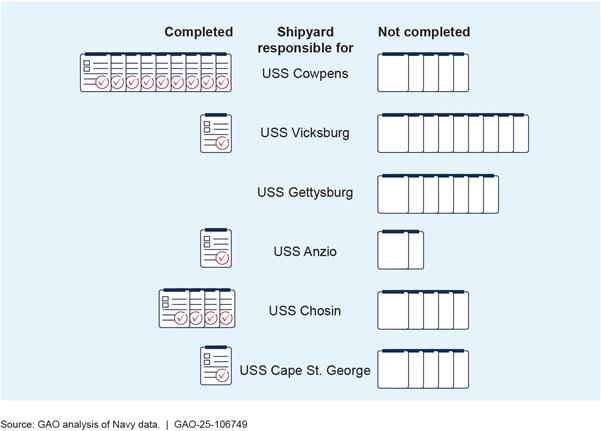

Figure 4 shows the seven cruisers that entered cruiser modernization. As shown, five of the seven ships began modernization periods, while the Navy discontinued work on one ship (USS Anzio) after beginning a maintenance period, and never started work on one ship (USS Hue City).[13] Figure 4 summarizes the maintenance and modernization periods and responsible RMC for each ship.

Note: This table only shows Chief of Naval Operations maintenance periods. Some of the cruisers, such as USS Gettysburg, had shorter and lower dollar continuous maintenance periods interspersed throughout their modernization.

Upcoming Surface Ship Maintenance and Modernization Efforts

In prior work, we identified that the Navy continues to face delays in building new ships to meet its current 355-ship force-level goal.[14] Therefore maintaining, modernizing, and extending the service lives of surface ships already in the fleet is crucial. Currently, the Navy plans to perform CNO maintenance and modernization periods on its destroyer and amphibious fleets in the next 10 years. These surface ship maintenance and modernization efforts are critical for ensuring that the Navy has enough ships to execute missions such as air and missile defense and supporting Marines in their missions.

The Navy has started to modernize its other large surface combatants, the Arleigh Burke class (DDG 51) Flight IIA Destroyers, through an effort called DDG Modernization 2.0. Currently in its early stages, this modernization, as previously mentioned, is estimated to cost more than $10 billion to modernize 23 DDGs over a span of 15 years. The ships will receive three different modernizations, including an upgrade to the newest and most capable radar, according to Navy officials. While DDG Modernization 2.0 is in the planning stages, the Navy has completed a modernization period for one destroyer and reported awarding contracts for two additional destroyers as part of an early effort to better understand the complexities of DDG modernization.

Further, the Navy is planning various potential service life extensions and modernizations to ensure it can meet the statutory requirement to have 31 operational amphibious warfare ships in the fleet.[15] The Navy is examining the possibility of extending the service life for selected amphibious assault ships. In addition, the Navy is planning significant maintenance and modernization efforts for the amphibious transport dock ships to ensure they are operationally available until the end of their expected 40-year service life and that they remain operationally relevant. The Navy expects the midlife maintenance to cost more than $1.8 billion for the 13 amphibious transport dock ships currently in the fleet. Additionally, officials are in the early stages of planning the modernization effort and said the Navy had not yet developed budget estimates for the effort.

Navy Spent about $3.7 Billion on Cruiser Modernization, Experienced Significant Quality Issues, and Recently Deployed One of These Ships

The Navy spent about $3.7 billion on cruiser modernization since 2015 and has failed to meet its objectives. Of the 11 ships the Navy intended to modernize, it now plans to deploy only three. These three ships will not gain 5 years of service life. The Navy has divested four of the cruisers prior to finishing modernization and without providing any operational value to the Navy, thereby wasting the $1.84 billion already spent to modernize them. The Navy decided to divest these ships, in part, due to a lack of funding to finish them, according to Navy officials. The three ships that have completed or are planned to complete modernization were scheduled for only one deployment before the Navy planned to divest them, however it has now extended their service lives and plans to decommission them in fiscal year 2030. In total, the Navy experienced approximately 36 percent cost growth on the cruisers it attempted to modernize and has cumulatively experienced over 15 years of schedule delays. Further, the Navy experienced significant quality issues implementing the cruiser modernization effort.

Navy Planned to Modernize 11 Ships but Expects to Return Only Three to Active Service

The Navy spent about $3.7 billion on seven of the 11 cruisers it intended to put through the modernization effort. It has deployed only one of these ships, though its initial plans called for completing the modernization of all 11 ships by the 1st quarter of fiscal year 2026. The Navy removed the remaining four ships from the effort in 2017 due to a lack of funding, according to officials. See figure 5 for the status of cruiser modernization as of August 2024.

Notes: The dollars spent noted in the figure are as of September 30, 2023. Officials told us the Navy has obligated an additional $26 million on cruiser modernization in fiscal year 2024.

Of the seven ships that entered the modernization effort, the Navy has divested four of them without completing modernization or deploying them. This is after incurring costs of $1.84 billion as of the end of fiscal year 2023 to maintain and modernize them. As shown in figure 5, these ships are USS Hue City, USS Anzio, USS Cowpens, and USS Vicksburg. USS Cowpens and USS Vicksburg have each undergone about 8 years of maintenance and modernization. But Navy officials told us that, as of May 2024, these ships would have required significant effort to complete their modernizations. For USS Cowpens, the Program Office estimated that, as of June 2022, it would have taken about $88 million and about 3 more years to complete the ship. However, officials managing the day-to-day work on USS Cowpens stated that they had not quantified the work remaining to complete the ship. As an example of outstanding issues on this ship, figure 6 shows a picture from June 2023 of rust and corrosion on the deck plate and holes in USS Cowpens’s flooring.

Similarly, in July 2024, the Navy divested USS Vicksburg with significant work remaining to complete the modernization. In September 2023, MARMC officials stated that the Navy would have been able to finish the ship with an additional $100 million by fiscal year 2025. However, these officials noted that this estimate did not include the cost of dry docking, which is necessary to fix the ship’s nonfunctional sonar dome—a critical element of the Anti-Submarine Warfare mission area. Program Office officials said it would have cost about $120 million to complete USS Vicksburg’s modernization. However, the RMC and Program Office’s estimates were likely optimistic, as a senior fleet forces official stated that USS Vicksburg is “years away” from completion. In addition, we observed during our tour of USS Vicksburg in September 2023 that modernization was largely incomplete. According to fleet officials, USS Vicksburg has since been cannibalized for parts for USS Gettysburg and other cruisers. Figure 7 shows the combat information center during our ship tour in September 2023 with consoles wrapped and disconnected and, therefore, unusable.

The Navy still plans to complete and deploy the remaining three cruisers—USS Gettysburg, USS Chosin, and USS Cape St. George—on which it had spent approximately $1.9 billion as of the end of fiscal year 2023, according to Program Office officials. Despite the plan for each ship to gain 5 years of service life, none of the three ships will. We discuss this in more detail later in the report.

USS Gettysburg completed its modernization, including sea trials, in February 2023. The Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey determined the ship meets the minimum standard to get to sea.[16] However, in January 2024 the Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey identified several outstanding issues during an inspection of the ship’s condition. For example, several elements of the weapons systems were inoperable or degraded and there were structural issues throughout the ship. Since the inspection, the Navy has addressed several of these issues and the ship completed 18 days at sea in June 2024 in preparation for deployment. During this time at sea, USS Gettysburg completed a successful missile launch and intercept using its updated combat systems software.

The Navy deployed USS Gettysburg in September 2024 with its carrier strike group. Prior to the deployment, the ship’s crew told us that parts continued to be a problem, including steering gears and hydraulic power unit solenoid valves, among others. To address this problem, the Navy used parts from the decommissioned cruisers. According to the ship’s crew, propulsion plant and electric system failures were key concerns for the USS Gettysburg deployment. Navy officials told us that future deployment plans for USS Gettysburg depend on how the ship does during its September 2024 deployment. However, the shipbuilding plan shows that the Navy plans to divest the ship in fiscal year 2026 after it completes its deployment.

USS Chosin also completed its modernization and sea trials in February 2024. The Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey plans to inspect the ship in fiscal year 2025, according to Navy officials. The Navy plans to deploy USS Chosin within the next few years before its planned divestment in fiscal year 2027.

USS Cape St. George is still undergoing modernization and the Navy plans to conduct sea trials in fiscal year 2025. Like USS Gettysburg and USS Chosin, the Navy currently plans to deploy USS Cape St. George at least once before divesting the ship in fiscal year 2027, according to senior Navy officials.

In November 2024, the Navy extended the service lives of USS Gettysburg, USS Chosin, and USS Cape St. George. The Navy now plans to decommission all three ships in fiscal year 2030.

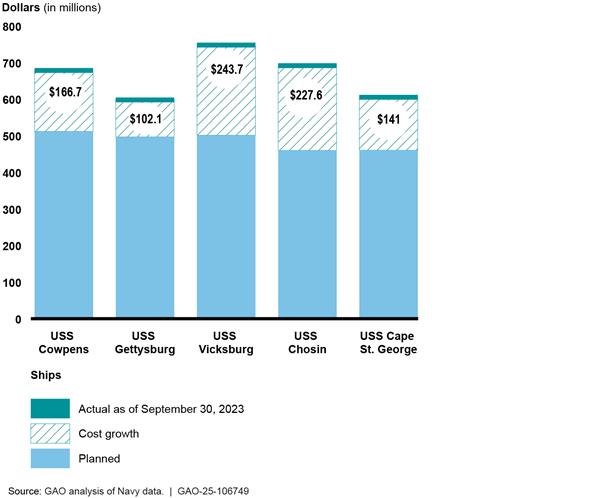

Cruiser Modernization Experienced Significant Cost Growth and Schedule Delays

The Navy planned to spend approximately $2.44 billion to complete maintenance and modernization work on the five cruisers that finished maintenance and transitioned to modernization periods—USS Cowpens, USS Vicksburg, USS Gettysburg, USS Chosin, and USS Cape St. George. We found that the maintenance and modernization work on those five cruisers experienced approximately $881 million in cost growth beyond the planned $2.44 billion.[17] This is a 36 percent cost increase. Figure 8 summarizes overall cost growth for the five cruisers that reached their modernization periods.

Note: The cost and cost growth shown in this figure include procurement of government furnished equipment, planning, program management, engineering support and testing, combat systems, and the maintenance and modernization periods.

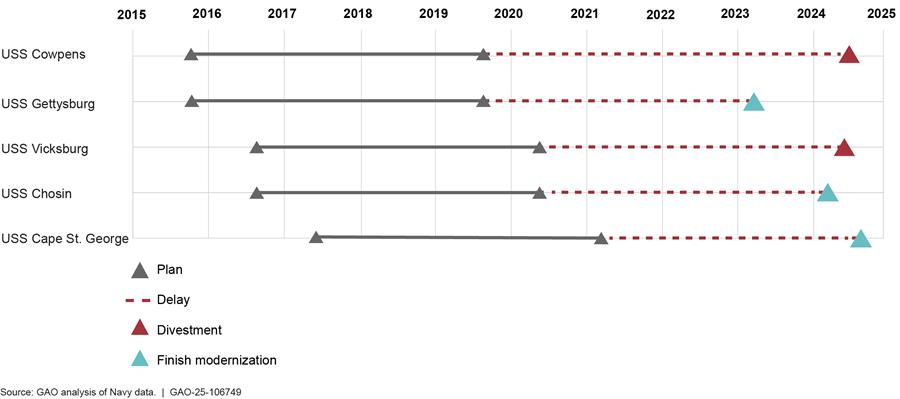

In addition to the cost growth, these five cruisers experienced extensive schedule delays. As previously mentioned, the Navy planned for each cruiser to undergo modernization for 4 years. However, the five cruisers that reached their modernization periods have faced schedule delays beyond the 4-year period, ranging from 3 to nearly 5 years (see fig. 9). The Navy originally planned for the maintenance and modernization periods to occur sequentially with gaps in between each period as shown in figure 3. However, these delays caused maintenance and modernization periods for individual ships to overlap. Figure 9 summarizes the delays.

Cruiser Modernization Efforts Hindered by Poor Quality

The Navy experienced widespread contractor performance and quality issues across all five cruisers that entered modernization. The Navy documents contractor performance using the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System (CPARS) which is the government’s tool for evaluating the contractor’s performance at certain intervals. CPARS evaluations are like report cards for the contractor that evaluate areas such as quality, schedule, and management. These evaluations provide relevant performance information for award decisions for future government contracts. The Navy completed CPARS evaluations for only 16 of the 49 evaluation periods.[18] In 13 out of the 16 completed CPARS evaluations the Navy documented significant quality issues.[19]

In addition, Navy’s RMCs issued over 1,400 Corrective Action Requests (CAR) to contractors, requesting that the contractors correct their work. According to the Navy, CARs are one of the most effective tools for quality assurance used when contractor work is deficient.[20] One of the two ships that entered modernization but failed to complete the program had the most instances of poor quality (see table 1).

|

Ship |

Number of CARs |

|

Ship 1 |

76 |

|

Ship 2 |

205 |

|

Ship 3 |

247 |

|

Ship 4 |

448 |

|

Ship 5 |

197 |

|

Ship 6 |

236 |

|

Grand total |

1,409 |

Source: GAO Analysis of Corrective Action Request Data. | GAO‑25‑106749

The following summarizes various quality issues for the five cruisers that completed maintenance and started modernization:

Ship 6. Ship 6 had the third most CARs issued among the cruisers undergoing modernization. Work related to the sonar dome is one example of repeated poor-quality work by the contractor on Ship 6. The sonar dome is located on the bottom of the hull and houses electronic equipment used for detection, navigation, and ranging. As part of the modernization effort, the contractor was to inspect the sonar dome rubber window while the ship was in dry dock. The contractor found that the window needed replacement. The government purchased a new rubber window and modified the contract to include window installation. However, Navy-provided documentation states the contractor began installation prematurely and without the presence of the manufacturer or representatives from the ship’s crew. The ship’s crew, upon learning of the installation, arrived at the ship to find the contractor had damaged the new sonar dome rubber window. The Navy wrote a CAR identifying the damage to government-furnished material caused by the contractor. Neither the Navy nor the contractor could fix the buckle in the window, as shown in figure 10. RMC officials told us the Navy then purchased a second, new window, which was installed 4 months later. According to Navy officials, the new window cost over $1.07 million and the government did not seek compensation from the contractor.[21]

The same contractor then conducted a required sonar dome pressurization test. This test seeks to ensure that there are no water leaks from the sonar dome that would damage the electronic equipment inside the dome equipment room or leak into other areas of the ship. The initial test failed, showing pressure loss was coming from large cables that run from the dome to other parts of the ship that are part of the degaussing system.[22] According to Navy documentation, in attempting to correct the pressure loss, the contractor used unauthorized materials such as plastic wrap, tape with common store bought super glue, expanding foam, and as seen on television sealant product, as shown in figure 11.

Figure 11: Use of Unauthorized Interventions, Including as Seen on Television Sealant Product and Plastic Wrap (left), Expanding Foam, Tape, and Common Store Bought Super Glue (right) as Documented by the Navy

After 13 failed retests and an 8-month delay, the contractor, with government approval, severed critical degaussing cables and installed nickel caps sealing off the sonar dome. According to officials, as a result of these and other quality issues, the Navy deprioritized Ship 6 and, as such, removed it from dry dock—prior to completing the sonar dome repair work—to accommodate another ship. Thus, if the Navy had wanted to complete sonar dome work on Ship 6, it would have had to return the ship to the dry dock. This would have been significantly more time consuming and costly than repairing it while it was already in dry dock. Because of these additional costs and the condition of the vessel, in its fiscal year 2024 President’s Budget Request, the Navy included the divestment of Ship 6. According to the Navy, congressional decision-makers did not oppose the divestment, and the Navy is proceeding with it.

Ship 4. Across the ship’s three maintenance and modernization periods, Ship 4 received the most CARs, 448, of any cruiser in this modernization effort and almost twice as many as the next highest ship at 247. The contractor for Ship 4 received several CARs for repeated quality issues. For example, ship’s crew officials told us about welding issues during our tour of the ship, which were also documented in CARs. The Navy issued two CARs for welds that were too close together and had a high chance of cracking as well as several welds that were not structurally sound. These deficiencies were found during surveillance by maintenance oversight officials. These CARs were categorized as major nonconformities. They were closed as satisfactory by maintenance oversight officials after the contractor corrected the welds.

In addition, across multiple contractors the Navy documented significant issues with work quality. Because of the condition of the vessel and costs to complete the ship, in its fiscal year 2024 President’s Budget Request, the Navy included divestment of Ship 4. According to the Navy, congressional decision-makers did not oppose the divestment, and the Navy is proceeding with it.

Ship 5. Across the ship’s maintenance and modernization periods, Ship 5 received 197 CARs. As an example of a quality problem, Ship 5 had issues with gun foundations (see fig. 12). Navy contract oversight officials said that the contractor replaced the gun foundations as part of the contract’s scope, but the contractor installed them at the incorrect height. To correct this issue, the foundations had to be removed and reinstalled, which caused a 4-month delay. In addition, the gun could not fire without hydraulic fluid leaking. Ship’s crew officials told us that they did not discover this issue until combat systems sea trials. The Navy has since corrected these issues. The Navy did not submit any CPARS evaluations for the contractor’s seven evaluation periods. We discuss the factors contributing to the failure to submit CPARS evaluations later in the report.

Ship 3. Across the ship’s maintenance and modernization periods, the contractors for Ship 3 received 247 CARs. For this ship, the contractor was executing the maintenance period while the Navy was competing the follow-on modernization contract. According to Navy maintenance officials, when the Navy awarded the modernization contract to a different contractor, the original contractor stopped working on the ship and left its tools and equipment on board. The Navy did not terminate the contract for default. According to Navy officials, the contractor for the modernization contract completed the work and this was done to prevent losing expired funding. However, this situation resulted in significant inefficiencies that affected quality. For example, an official who worked on both the maintenance and modernization periods, stated that Ship 3 was in bad condition when it left the maintenance period contractor and the modernization contractor had to spend significant resources to repair the ship prior to beginning modernization.

CPARS evaluations showed that the Navy documented poor contractor quality across many of the evaluation periods. In these ratings, the Navy stated that the work was highly complex, including difficult welding that the contractor was not prepared to accomplish. One contractor strongly disagreed and the government reviewing official increased one rating.

Ship 2. Across the ship’s two maintenance and modernization periods, the contractors for Ship 2 received 205 CARs. As an example, several CARs were issued for welding nonconformities mostly due to failure to meet joint requirements, not adhering to standard procedures, and weld joints not straight or offset as required. According to one of these CARs, an RMC quality assurance specialist noticed in a single day that five contractor personnel in three separate areas of the ship were using incorrect welding methods not in accordance with the requirements. While the CAR was closed as satisfactory, the ship’s crew stated, during our ship tour in October 2023, that welding is an ongoing issue. Across the contractors, the Navy only submitted one CPARS evaluation for the six evaluation periods.

Insufficient Planning Led to Poor Execution and Outcomes

Even though the Navy used more than $2 billion of procurement funding for cruiser modernization, it did not implement planning and oversight tools typical of high dollar major defense acquisition programs following the major capability acquisition pathways because it is not an acquisition program. Further, the Navy also failed to factor key elements into its planning, such as the condition of the ships and stakeholder involvement, including RMC officials and Port Engineers. This resulted in significant amounts of unplanned work that negatively impacted the execution of the cruiser modernization program.

Cruiser Modernization Effort Did Not Include Key Planning and Oversight Tools

The Navy did not develop key program planning and oversight tools and documents for the cruiser modernization effort, such as an acquisition strategy, independent cost estimate, risk management plan, baseline, and Navy program oversight meetings, according to Navy officials. The cruiser modernization effort was not required to implement these elements because it was not a program within DOD’s acquisition system.[23] Nevertheless, these tools could have been used to support Navy program managers, senior leadership, as well as stakeholders in the DOD and Congress to plan, manage, and oversee large Navy modernization efforts. Table 2 provides our assessment on the extent to which the Navy used key acquisition planning and oversight tools on the cruiser modernization effort.

Table 2: Planning and Oversight Tools for Programs Using DOD’s Major Capability Acquisition Pathway Compared to the Navy’s Cruiser Modernization Effort

|

Acquisition planning tool |

Description |

Impact of not using acquisition planning tool |

|

Acquisition strategy |

A comprehensive integrated plan that identifies the acquisition approach and key framing assumptions. It describes the business, technical, product support, security, and supportability strategies that the Program Manager plans to employ to manage program risks and meet program objectives. |

Navy officials told us that the Navy did not have a comprehensive acquisition strategy to meet the program objectives of cruiser modernization, such as inducting each of the 11 cruisers into modernization for no more than 4 years or extending the service lives of the cruisers by 5 years, from 35 to 40 years. The Navy did outline standards for its 2-4-6 modernization effort and develop acquisition plans for the individual ship modernization periods. However, it did not document a comprehensive acquisition strategy for the overall modernization effort. Among other issues, an acquisition strategy could have helped prevent maintenance period delays, which contributed to overlap of modernization periods and postponed deployments. |

|

Cost estimate |

Provides an in-depth cost estimate that covers the entire life cycle of the program. The estimate should include analysis to support decision making that identifies and evaluates alternative courses of action that may reduce cost and risk and result in more affordable programs and less costly systems. |

The Navy did not develop a cost estimate or assessment that covered the cruiser modernization program with significant depth. The Navy provided some cost estimate documents, but the documentation either did not include all 11 cruisers intended for modernization or provided information in slide format at a very high level. Additionally, these estimates were below the contractor offers received and the contract amounts awarded. The Navy also did not seek an independent review of its cost estimate documents. An independent cost estimate is one of the best and most reliable methods for validating an estimate. It provides an independent review of expected costs and tests the program office’s estimate for reasonableness. Had the Navy developed a sufficient cost estimate, it could have more accurately forecasted the true cost of conducting these modernizations and would have had better information for decision making throughout the effort. |

|

Risk management plan |

Provides program risks and associated risk mitigation plans. Typically detailed in the program acquisition strategy and presented at all relevant decision points and milestones. |

The Navy did not document specific risks or take steps to mitigate risk during cruiser modernization, according to Navy officials. For example, as discussed above, the Navy planned for months-long gaps between the cruisers’ modernization periods. However, when the cruiser modernization periods experienced schedule delays, the Navy had no method of preventing various maintenance and modernization periods from overlapping. When these periods overlap, there are risks that need to be identified and addressed, such as conflicting contractor work schedules. Without a risk management approach, the Navy waited for risks to be realized. According to a DOD report, this often sparks a ripple effect that results in additional delays. For the Navy, this could lead to incomplete, out of sequence, and insufficient work that must be redone. A more comprehensive risk management plan would have assessed these potential challenges thoroughly and identified more effective mitigation strategies. |

|

Baseline |

Documents the program cost, schedule, and performance baseline. A baseline allows tracking and reporting of cost and schedule deviations above certain thresholds from initial estimates through the life of the project. |

The Navy did not track the progress of cruiser modernization against its original cost and schedule baselines or report deviations to leadership. For example, as delays occurred, goals were updated in briefing documents to leadership that did not address divergence from original plans. As a result, senior leaders did not have information that could have improved decision making throughout the modernization program. |

|

Integrated Master Schedule |

An integrated and reliable schedule can realistically reflect changes, show when major events are expected, and show the completion dates for all activities leading up to them. This can help determine if the program’s parameters are realistic and achievable. |

Given the $3.7 billion cost of this effort, a master schedule could have been developed to integrate various types of work (e.g., modernization periods and maintenance periods). A master schedule would also have enabled the Navy to manage the critical work necessary to achieve the cruiser modernization effort and make decisions to remove some work from the scope when it was clear that the efforts were going much longer than planned. A master schedule would have also provided the means to gauge progress, identify and resolve potential problems, and promote accountability at all levels of the program. Without such a schedule, the Navy was unable to adjust to changes from the planned schedule without significant delays. |

|

Navy leadership/ stakeholder meetings |

Provides a setting in which the Program Office and other involved Navy organizations can brief Navy leadership on progress. These gate reviews are at key junctures that allow leadership to weigh in on decisions made, offer feedback, and provide accountability. |

The Navy did not participate in a gate process for the cruiser modernization effort, according to Navy officials. While leadership was briefed on the status of cruiser modernization, following a standard gate process would have provided a mechanism for involving leadership more actively at key milestones. These meetings would have provided the cruiser modernization effort with an environment in which progress could be tracked, and the Program Office could be held accountable. As a result of not holding these meetings, leadership had fewer opportunities to weigh in on and compare the progress of cruiser modernization efforts to initial objectives. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) Instruction 5000.85, and Navy Instruction 5000.2G, and Navy data. | GAO‑25‑106749

DOD typically uses these tools for programs using the major capability acquisition pathway. While the Navy did not identify the cruiser modernization effort as an acquisition program within DOD’s acquisition system, use of these acquisition tools could have served as a model to identify appropriate cost and schedule objectives for the effort as well as identify and resource risks.[24] Of the $3.7 billion that the Navy spent on the cruisers, $2 billion were procurement dollars—used to buy new capability—while the remaining funding was maintenance dollars. When procurement funding dollars reach similar levels for acquisition programs, reporting requirements associated with larger DOD acquisition category programs (highlighted in table 2)—while some may not be relevant to cruiser modernization—could be leveraged to facilitate oversight of Navy modernization efforts.[25] Acquisition programs of this size using the major capabilities acquisition pathway are generally required to establish an acquisition cost and schedule baseline prior to program start, report any significant deviations from the established baseline—also known as a “breach”—and provide information on risk management to senior leadership.[26]

We have previously recommended that DOD manage other modernizations and large projects as separate acquisition programs to encourage the use of acquisition planning tools. In 2016, we reported on modernization efforts for the F-35 aircraft. In that review, we endorsed the approach to use planning tools for some aspects of the program and recommended that DOD expand its use of acquisition planning tools to the full program.[27] Further, in 2018, we found that the Navy was not conducting cost, schedule, and risk assessments to help manage the future dismantling of the first nuclear powered aircraft carrier—CVN 65—a complex project estimated to cost more than $1 billion. In assessing this issue, we determined that while many requirements for DOD acquisition programs were not relevant to dismantlement and disposal, the Navy should leverage elements of the acquisition planning tools associated with larger DOD programs to facilitate oversight of CVN 65 dismantlement and disposal.[28]

Other leading practices and standards also support using acquisition planning tools for large projects, such as ship modernization. For example, GAO’s Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide states that having a realistic estimate of projected costs makes for effective resource allocation and increases the probability of a program’s success.[29] Additionally, the Standards for Internal Control in Federal Government state that to identify and mitigate risk, program objectives such as a baseline for cost and schedule should be clearly defined in measurable terms so performance in attempting to achieve those objectives can be assessed.[30]

Navy officials responsible for the upcoming DDG Modernization 2.0 are using some acquisition planning tools, even though DOD and Navy policy do not require they do so. Officials recognize the benefit that using these tools could have on managing a major modernization effort. For example, the Navy developed an acquisition strategy for the effort and officials from the new program office established for this modernization effort told us that they are developing a group specifically focused on identifying, documenting, and resourcing risks. Program leadership told us that even though they are not required to use these acquisition planning tools, these tools and a disciplined approach to planning are critical to the success of the more than $10 billion program. For example, DDG Modernization 2.0 officials are developing an integrated master schedule. However, the Navy has yet to incorporate all the tools listed in table 2, such as participating in gate meetings, that could have set the cruiser modernization on a more successful path.

By not using acquisition planning tools, the Navy did not adequately plan for modernizing the cruisers. It is too late to do so for the cruiser modernization effort. The Navy will be investing at least $10 billion in other modernization efforts, including the DDG. Without requiring these modernization efforts to use the acquisition planning tools that major acquisition programs following the major capability acquisition pathway generally use, the Navy may miss the opportunity to use these tools to better manage future efforts.

Navy Faced Numerous Challenges to Accurately Planning Cruiser Maintenance and Modernization Work

The Navy experienced significant challenges planning each ship’s maintenance and modernization periods. The three most common factors that inhibited the planning for these maintenance and modernization periods included: (1) ship condition, (2) planning time frames, and (3) ship ownership and inactivation of the cruisers, based on our interviews with NAVSEA 21, the Program Office, OPNAV, CNRMC, RMCs, and Port Engineers.

Ship Condition

The Navy did not sufficiently track and, thus, did not fully understand, the condition of the cruisers prior to modernization. NAVSEA 21, Program Office, and OPNAV officials told us that, in hindsight, the cruisers were in worse condition than they realized. Navy officials noted that this was primarily due to the Navy deferring maintenance by cancelling maintenance periods throughout the lives of these ships. As an example, fuel tank cracks, likely the result of cancelled maintenance according to OPNAV officials, have been an ongoing challenge during USS Vicksburg’s modernization. In some cases, the Navy deferred planned maintenance to address critical national security priorities. For example, according to OPNAV officials, the Navy deferred cruiser maintenance periods during the 2000s due to the operational need for the cruisers during the Global War on Terror. Then, Navy officials told us the Navy canceled maintenance periods for the cruisers between 2011 and 2014, because the Navy was planning to divest the cruisers. Once Congress provided funding for the modernization effort, the Navy tried to gain information on the condition of the cruisers.[31] For example, for seven of the cruisers that entered the cruiser modernization effort, the Navy completed pre-modernization surveys to assess the condition of the ships and ship checks between 2015 and 2019. Navy officials told us that the pre-modernization surveys were comprehensive and robust. However, the high volume of unplanned work indicates that these efforts to gain information were unable to make up for years of not tracking ship condition and deferring maintenance. We have previously found that deferred maintenance creates a backlog of maintenance tasks and can contribute to the Navy deciding to decommission a ship due to its condition.[32]

Starting in 2010, the Navy has made changes to better track ship condition, but the improvements from these changes are too late to help the cruiser fleet. Deferred maintenance and lack of knowledge on the condition of ships was a known issue across the Navy surface fleet, which led to a 2010 assessment of Navy Surface Force readiness.[33] The report found that Surface Force readiness had degraded over several years. Among other things, ship maintenance requirements had not been adequately identified or resourced. Following that report, in November 2010, the Navy established the Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program (SURFMEPP). SURFMEPP is tasked with providing centralized class maintenance and modernization planning, and management of maintenance strategies. SURFMEPP also assesses the extent to which ships’ maintenance requirements have been met. For example, in 2014, SURFMEPP started to publish reports on priority repair work that could affect ship service life. Further, in 2016, SURFMEPP started to develop Life Cycle Health assessments for the surface fleet, which provide an annual overall health score and a condition assessment for each ship.

Navy officials told us that they have continued to improve the information they have on the condition of ships. For example, they said they have conducted more robust assessments of the condition of Navy ships and are better tracking what required maintenance needs to be completed. The Navy’s improvements are helping its ability to track ship condition and improve the probability that ships meet their service lives. However, these improvements are more impactful as a preventive measure on newer ships that have yet to fall behind than for older ships where the Navy has already deferred significant maintenance and lost track of condition, as happened with the cruisers.

Planning Time Frames for CNO Maintenance Periods

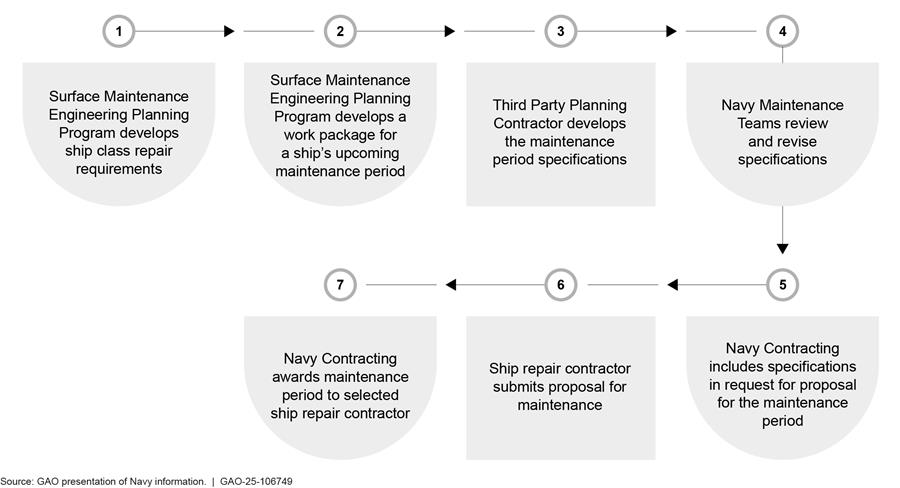

In 2015, the Navy changed the process and time frame for planning. As previously noted, the cruiser modernization effort involves both maintenance and modernization work. The Navy now uses a planning contractor to develop work specifications, rather than relying on planners of the ship repair contractors as it did previously. Work specifications are sets of instructions to help the lead contractor understand and complete the work. If, after performance begins, the needed work is within the scope of the contract but does not match the work specified in the contract, the Navy modifies the contract to accommodate the unplanned or poorly specified work. As previously mentioned, cruiser modernization also began in 2015. Thus, the new planning process was used for most of cruiser modernization. The maintenance planning process is depicted in figure 13 below.

Figure 13: Navy Maintenance Period Planning Process for Surface Ships Since 2015

Note: As previously mentioned, maintenance periods also involve modernization. The process outlined above also applies to maintenance periods during which modernization occurs.

To facilitate planning, the Navy has set milestones to award contracts a specific number of days before work begins. The milestones established in 2015 applied to most of the cruiser maintenance and modernization planning. Planning for a maintenance period contract, including the scope of work and specifications, was to be complete 155 days before contract award and the contract was to be awarded 60 days prior to the start of work. In January 2020, after cruiser modernization planning was complete and all the contracts had been awarded, the Navy extended the time frames for completion of maintenance period planning. Now, the Navy aims to complete planning 350 days before contract award, with contract award 120 days prior to the start of work.

Program Office and RMC officials noted that planning the scope of work and work specifications for maintenance period contracts 155 days prior to contract award makes it challenging to have an accurate work package. This is because even if the third-party planners and maintenance stakeholders, for example RMC officials, have an accurate assessment of ship condition, the condition of a ship is likely to change throughout the planning process prior to the start of work. However, at the same time, the Navy reported that these maintenance period contracts require more advanced planning to ensure adequate time to develop the procurement package and compete the contract. Completing planning and awarding a contract earlier is beneficial because it allows for the earlier procurement of long lead time material and the Navy has reported that this also allows the contractor to be involved earlier. However, RMC officials noted this as an area of concern because the condition of a ship degrades over time, and it provides less time for planning which is a labor-intensive process.

Navy officials continue to try to improve the planning process, but balancing these competing goals is difficult. For example, Navy officials stated that the DDG Modernization 2.0 effort has used undefinitized contract actions for the DDG Modernization contracts to have more flexibility in planning timeline requirements.[34] The Navy stated that its expectation is that all remaining maintenance periods will have definitized contracts at award.

Ship Ownership and Inactivation

As the cruisers entered the modernization effort, the Navy inactivated the cruisers, transferring ownership—meaning the overall technical, acquisition, and execution authority—from the fleet to NAVSEA. This was part of an attempt to reduce crew size and save money on crew costs, according to OPNAV officials. However, inactivating the ships and reducing the crew made it more difficult for program officials to understand the condition of and maintain the ships, thus inhibiting accurate planning for the modernization effort. For example, according to Navy officials, it was hard to assess the condition of inactivated ship systems. Further, because the ships had reduced crews of 45 sailors and the systems were turned off, these systems further deteriorated. This additional deterioration was difficult to identify until the Navy increased the crew size and started to reactivate the ships midway through each ship’s modernization period.

Also due to the transfer in ship ownership, the Navy deviated from its typical work specification development process. The NAVSEA guidance outlining cruiser modernization states that NAVSEA 21 is accountable and responsible for maintenance period planning. According to RMC officials, the NAVSEA Program Office’s involvement in planning was atypical, because normally the RMCs in conjunction with the port engineers—the maintenance officials who are the most familiar with the condition of the ships—would work with the planning contractor to develop specifications for maintenance availabilities. As a result, according to RMC officials, this approach contributed to incorrect specifications. RMC officials and port engineers told us that the Program Office did not incorporate their feedback into work specifications developed by the planning contractor for the cruiser maintenance and modernization periods. Program Office officials said that they knew there was a rush to plan cruiser modernization, which could have resulted in the RMCs feeling like they were not included in specification development. In addition, they stated that the issues described by the RMC officials and port engineers were a result of the change in ownership of the cruisers.

Officials across the Navy organizations we met with told us that a lesson learned from cruiser modernization is that the Navy should not transfer ownership or inactivate a ship undergoing modernization to this extent again. OPNAV officials stated that the challenges associated with transferring ownership and inactivating a ship are Navy lessons learned being applied to DDG Modernization 2.0. However, officials noted that the Navy has not codified this lesson learned into policy. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks.[35] OPNAV officials agreed that the lessons learned should be codified in policy but added that the Navy could need to do something similar, such as inactivate the ship, reduce the crew size, and transfer ship ownership to save money in a budget constrained environment. They also stated that Navy leadership needs to retain flexibility. However, doing so would likely significantly increase the risk of the Navy experiencing poor outcomes, as occurred with the cruiser modernization effort. Without codifying this lesson learned into policy, the Navy may revisit this idea once again when faced with future cost constraints.

Planning Issues and Unplanned Work Impacted the Navy’s Ability to Efficiently Manage Cruiser Modernization Effort

As a result of its ineffective planning, the Navy experienced high volumes of unplanned work. This led to delays and cost increases from which the cruiser effort could not recover. For example, one of the cruisers had over 2,500 unplanned work items across three contracts that had a total contract price increase of over $103 million. According to maintenance officials, the administrative processing and repair time to address these 2,500 items contributed to preventing the Navy from achieving its cost and schedule goals. Further, Navy contracting officials stated they have attempted some efforts to reduce contract administration times through contracting initiatives.

Planning Shortfalls Led to Unplanned Work

As a result of poor planning and inaccurate specifications, the Navy experienced numerous instances of unplanned work on its cruiser maintenance and modernization contracts, resulting in cost and schedule delays discussed earlier. Unplanned work generally divides into two categories—new work and growth work. Growth work is when tasks are added to related work items already specified in the contract, such as discovering significant corrosion upon dismantling a piece of equipment. New work is when tasks are added that are not related to items already specified in the contract. As shown in table 3, the Navy experienced over 9,000 contract changes due to growth work that, on average, took 47 days to process. This does not include the time to execute the work.

According to RMC officials, this high volume of unplanned work largely derailed the cruiser modernization schedule because the Navy could not process the contract changes in time to keep these efforts on track. When unplanned work is discovered, the Navy must determine if the work should be added to the contract and if so, define the task(s), communicate to the contractor the need for the contract change, request a contractor proposal, negotiate the price, and modify the contract. To navigate a high volume of work, an efficient process is critical since, according to the Navy, increasing the speed and accuracy of processing changes is a driver to on-time availability completion. While speed is critical, especially when faced with a high volume of changes, accuracy in the underlying documentation and negotiating a fair and reasonable price is also important and takes time. Table 3 shows the number of processing days due to growth work across all six cruiser modernization ships that began maintenance or modernization work.

|

Growth work change reason |

Total changes |

Average days per change |

|

Work that could not be planned |

3,809 |

42.39 |

|

Drawing, Specification, or Technical Document Issue |

2,655 |

55.43 |

|

Other |

1,337 |

49.49 |

|

Removal from scope of work |

1,223 |

40.98 |

|

Total |

9,024 |

46.71 |

Source: GAO analysis of Navy request for contract change data. | GAO‑25‑106749

Note: From creation to settlement is defined as the time between change issuance to contractor and price settlement. In addition, the Other category consists of obstruction in work area, testing issue, funding unavailable, ship condition not reflected in contract requirements, material issues (unavailable, defective, not ordered) and acts of nature. Removal from scope of work refers to work deleted due to change in schedule, lack of funds, descoping work, work completed prior to availability or defer work to later maintenance period. The start for the process time is the “Creation Date” field in the Navy Maintenance Database for request for contract changes. The process time end is the “Settled Date” field in same database. This table includes the growth work across all six cruiser modernization ships that began maintenance or modernization work.

Contractors typically do not begin work on the growth work changes until processing is complete and prices have been agreed to. This can lead to out of sequence work if too many changes accrue. The Navy stated that requesting additional funding through an upward obligation request is a time-consuming process that can contribute to higher processing times.[36] About $179 million in upward obligations was needed between 2019 and 2024. The delay caused by the changes significantly contributed to the cruisers’ schedule delays.

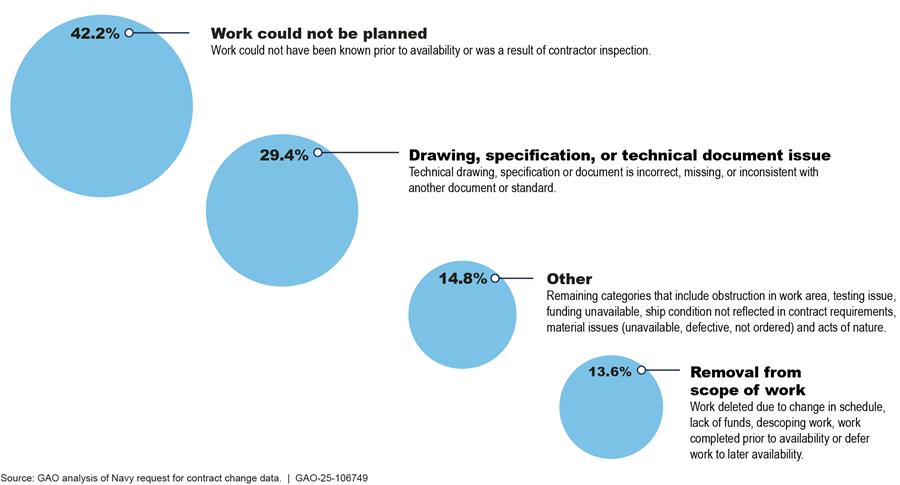

We assessed the Navy’s data and found that nearly all the changes across 13 maintenance and modernization periods were due to growth work. Further, our analysis of Navy growth work data identified that over 70 percent of those contract changes had two causes: (1) work that could not be planned, and (2) drawing, specification, or technical document issues.[37] Figure 14 shows the breakdown of the categories of growth work changes for the cruiser maintenance and modernization periods.

Figure 14: Categories of Contract Changes Due to Growth Work across 12 Contracts for Cruiser Modernization

While 42.2 percent of the changes were categorized by Navy officials as work that it could not plan, the Navy likely could have prevented some of this growth work with a better life-cycle maintenance plan. A life-cycle maintenance plan is a comprehensive analysis of forecasted repairs, directive repairs, associated support services, and a fixed percentage of the resources for Fleet Alterations to provide requirements for a maintenance event that conforms to the Fleets’ constraints. For example, a better understanding of the ship’s condition could inform the Navy of areas likely needing work, common problems across the ship class, and maintenance work that has not been done.

A second category, totaling 29.4 percent, are changes due to the Navy providing missing, incorrect, or inconsistent drawings, specifications, or technical documents to the contractor. In our past work, Navy officials have said omissions and inaccuracies with ship documentation disrupt the contractor’s ability to sequentially plan and perform work in line with cost and schedule goals.[38] For example, maintenance oversight officials noted that 75 percent of the work for a ship maintenance and modernization period is planning, and the consequence of improper planning is high volumes of growth work.

The Navy states it has yet to fully assess the root causes of why the cruiser planning and specification effort was ineffective and codify resulting strategies into Navy maintenance policy documents to implement lessons learned for future surface ship modernizations. Several Navy officials stated that the cruiser effort is unique because, as previously mentioned, in addition to significant deferred maintenance for the ships, the Navy transferred ownership of the ships to NAVSEA, reduced the crew sizes, and inactivated the ships. However, we have previously found that the Navy often experiences planning challenges and growth work across surface fleet maintenance.[39] In addition, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations released a memorandum in April 2024 that directed its staff to investigate maintenance planning and roles and responsibilities for amphibious ships.[40]

Standards for Internal Control in Federal Government state management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks—by acceptance, avoidance, reduction or sharing—related to achieving the defined objectives.[41] The Navy has stated that growth work is expected in maintenance and modernization periods, and early-stage planning to avoid or reduce a great volume of growth work is necessary to manage risk. Analyzing the root causes of the cruiser modernization growth work would provide the Navy with important insights to develop effective approaches during the planning stages for future efforts such as the upcoming DDG modernization.

Efforts to Reduce Lengthy Contract Change Process

The Navy has made several attempts to reduce the delays and administrative burden caused by growth work. NAVSEA 02 officials noted that contract changes have been a problem for years. As a result, beginning in 2018, they implemented some tools to reduce processing times for contract changes due to growth work.

· Level of Effort to Completion initiative is used in six of the 12 cruiser contracts. The Navy sets aside a pre-funded set number of hours and material costs when a contract is awarded to fund growth work that contractors regularly discover during execution. Thus, it is not necessary to separately negotiate each item.

· Small Dollar Value Growth contract term is used in three of the 12 cruiser contracts. It specifically addresses schedule delays due to growth work items valued at $25,000 or less. This contract term allows the Navy and the contractor to agree on a set price—usually between $8,000 and $10,000 according to Navy officials—to be used for a growth work item of value equal to or less than $25,000, eliminating the time-consuming negotiation of small dollar growth work.

The Navy’s goal for processing growth work contract changes is 7 days. When using the Level of Effort to Completion initiative, the goal is 5 to 7 days. When using the Small Dollar Value Growth contract term, the goal is shortened to 1 to 2 days. As discussed above, the processing time for contract changes for cruiser modernization overall exceeded 46 days on average. Table 4 shows the contract change cycle times when using the two streamlining contract tools for growth work compared to the average times without use of a streamlining contract tool.

|

Contract change process tool |

Total changes |

Average days |

Decrease in days |

Goal |

Days over goal |

|

No special tool used |

7,646 |

50.87 |

N/A |

7 |

43.87 |

|

Level of effort to completion |

464 |

47.11 |

3.76 |

5-7 |

40.11 |

|

Small dollar value growth |

1,111 |

21.33 |

29.54 |

1-2 |

19.33 |

Source: GAO analysis of contract change cycle times. | GAO‑25‑106749

While processing times for cruiser modernization growth work are still far above the 7-day goal established by the Navy, use of the two contracting tools did reduce cycle times, as shown above. The Navy continues to implement initiatives to shorten the contract change process time and address other factors of cycle time. Navy contracting officials stated they have analyzed these processes and discussed the results with industry. Delays were found to be in two main areas: contractor proposal submissions to the Navy and negotiation of the final price adjustment. Navy contracting officials stated they have attempted to address the delay in receiving contractor proposals by including contract terms through which they could assess monetary penalties for late proposals.

Weakened Quality Assurance Tools and Uncoordinated Work Hindered Cruiser Modernization Oversight

Despite widespread instances of poor-quality work during the cruiser modernization effort, NAVSEA senior leadership discouraged RMCs and contracting officials from fully using key quality assurance tools to maintain the industrial base and a positive working relationship with the ship repair industry. This reduced the RMC’s ability to ensure that contractors were producing quality work. Further, Navy guidance does not set forth clear roles that enable coordination among several key stakeholders within the Navy, which further inhibited effective oversight of work.

Navy Took Actions That Weakened Use of Contract Quality Assurance Tools