INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT

Federal Entities’ Efforts to Increase Opportunities for Minority- and Women-Owned Asset Managers

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Michael E. Clements at ClementsM@gao.gov or Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen at NguyenTT@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106766, a report to congressional requesters

Federal Entities’ Efforts to Increase Opportunities for Minority- and Women-Owned Asset Managers

Why GAO Did This Study

MWO firms managed about 1.4 percent of the $82 trillion overseen by a sample of asset management firms in 2021, according to an industry report. Some policymakers raised questions about the extent of federal entities’ use of MWO firms and the challenges these firms face in competing for opportunities.

GAO was asked to update its 2017 review of federal entities’ use of MWO firms. This report describes selected federal entities’ use of MWO firms, challenges these firms may face in competing for business, federal entities’ alignment with key practices for selecting asset managers, and the status of SEC efforts regarding diversity in the asset management industry, among other objectives.

GAO reviewed investment policies and financial statements of seven federal entities that manage or sponsor nine investment plans (seven retirement plans, one endowment, and one insurance program) that were also reviewed in GAO’s 2017 report. GAO reviewed SEC staff reports and press releases. GAO also interviewed or held discussion groups with representatives of SEC, the federal entities, and industry stakeholders including five consulting firms, four industry associations, two researchers, 11 MWO asset management firms, five non-MWO firms, and five nonfederal plans.

What GAO Found

Use of minority- and women-owned asset managers (MWO firms) varied among nine selected federal investment plans reviewed by GAO. In 2022, 61 MWO firms managed about 3 percent of total externally managed assets across five of the nine plans (see figure). The use of MWO firms increased since GAO’s prior report on the topic (GAO-17-726). Four of the nine plans did not use MWO firms.

Federal entity officials that manage the selected federal plans and many industry stakeholders GAO spoke with said that MWO firms continue to face challenges in competing for opportunities in the asset management industry that are similar to those that GAO reported in 2017. For example, they said that MWO firms lack the size or resources to keep client fees low, a challenge larger firms can more easily overcome due to their greater capacity and resources.

All seven federal entities that GAO reviewed incorporated key practices that institutional investors can use to increase opportunities for MWO firms. For example, the entities generally conducted outreach to MWO firms and communicated expectations of inclusive practices to their staff and consultants. This represents an improvement from GAO’s 2017 review, which found that four of the seven federal entities had not done so. Two executive orders issued in January 2025 directed federal agencies to end diversity-related initiatives. In February 2025, officials from two federal entities said they had not determined whether the orders impacted their application of the key practices; officials from three said there would be no impact because their asset manager selection processes are merit-based; officials from one said they will remove references to MWO firms from its policies; and officials from another declined to comment.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and its staff took steps to promote diversity in the asset management industry. For example, in January 2018, SEC introduced a voluntary self-assessment for regulated entities to evaluate their diversity policies and practices and report demographic information. In February 2025, SEC staff said that they were analyzing the potential impact of the executive orders on the industry self-assessment. SEC staff removed staff guidance from the SEC website that addressed investment advisers’ consideration of diversity-related factors when recommending or selecting other investment advisers. Accordingly, GAO removed an assessment of this staff guidance and a related recommendation from its review.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AAFES |

Army and Air Force Exchange Service |

|

BlackRock |

BlackRock Institutional Trust Company |

|

DEI |

diversity, equity, and inclusion |

|

DEIA |

diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility |

|

Dodd-Frank Act |

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FRTIB |

Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board |

|

MWO |

minority- and women-owned |

|

NEXCOM |

Navy Exchange Service Command |

|

OMWI |

Office of Minority and Women Inclusion |

|

PBGC |

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation |

|

SEC |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

|

TSP |

Thrift Savings Plan |

|

TVA |

Tennessee Valley Authority |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 15, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Minority- and women-owned asset management firms (MWO firms) managed about 1.4 percent of the $82 trillion overseen by a sample of asset management firms in 2021, according to one industry report.[1] In 2017, we reported on challenges these firms may face, including the preference of some institutional investors to contract with large, well-known asset managers with brand recognition. We recommended that four federal entities serving as institutional investors take certain steps to increase opportunities for MWO firms, which they had implemented by 2021.[2]

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates asset management firms registered as investment advisers. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) requires SEC to develop standards to assess the diversity policies and practices of entities it regulates through its Office of Minority and Women Inclusion (OMWI).[3] Some policymakers have raised questions about the availability of data on the use of MWO firms and opportunities for MWO firms to compete for work with institutional investors.

You asked us to update our prior work and examine federal entities’ use of MWO asset management firms and SEC’s efforts to promote diversity in the industry. Two executive orders issued in January 2025, during our audit work, directed federal agencies to end diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) initiatives and programs.[4] As a result, SEC staff removed staff guidance from the SEC website that addressed investment advisers’ consideration of DEI factors when recommending or selecting other investment advisers.[5] Accordingly, we removed an assessment of this staff guidance from our review.[6]

In this report we discuss

1. changes since our last report regarding selected federal entities’ use of MWO firms and the major asset classes in which they invest;

2. reported challenges faced by MWO firms in competing for work and selected federal entities’ efforts to align with key practices for increasing these firms’ opportunities;

3. selected federal entities’ data collection on their use of MWO firms and challenges to consistent reporting; and

4. the status of SEC actions regarding diversity in the asset management industry.

To address these objectives, we reviewed seven federal retirement plans, one endowment, and one insurance program administered or overseen by seven of the entities reviewed in our 2017 report.[7] These selected federal entities are the Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES); the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board (FRTIB); Smithsonian Institution; Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC); Navy Exchange Service Command (NEXCOM); and Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).[8] We selected the entities based on investment size (assets of more than $1 billion) and to reflect a mix of strategies (both passive and active management).[9] Findings from our review cannot be generalized to other federal plans.

To address our first objective, we reviewed 2022 data provided by the selected federal entities on the number of MWO firms they contracted with, the amount of assets managed by these MWO firms, and available information on their demographic characteristics. We obtained asset allocation data from the federal entities’ audited financial statements and annual reports for 2022 (the most recent available at the time of our review) and 2015 (the year used in our 2017 report). We also interviewed selected federal entity officials to understand their reported MWO firm use and asset allocations.

We identified MWO firms using publicly available directories and databases. We determined the market share of these firms by obtaining their reported assets under management from their Form ADV filings in SEC’s Investment Adviser Public Disclosure database.[10] We compared the total assets under management by MWO firms to the industry total as of November 2023.[11] We also compared this to our 2017 data. However, direct comparisons between the 2022 and 2017 data are limited due to differences in the sources used to compile the list of MWO firms. To assess the reliability of these data, we checked information from the Form ADV filings of a nongeneralizable sample of firms against publicly available information, such as firm ownership and history, location, and audited financial statements from the firms’ websites, and removed duplicates. We determined the data we used were sufficiently reliable for determining the market share of the MWO firms.

To address our second objective, we interviewed representatives from five consulting firms used by federal entities to contract with MWO firms, as well as four industry organizations and two research organizations with expertise in the asset management industry.[12] We held three asset management discussion groups with a total of 16 participants that reflected a range of firm sizes, geographic locations, and asset specializations. Two of these discussion groups were with representatives from 11 total MWO firms and one was with representatives from five non-MWO firms. We also held one discussion group and one group interview with a total of five representatives from nonfederal retirement plans.[13] We obtained and analyzed documentation from the federal entities on their policies and processes for selecting asset management firms. We assessed this information against the key practices institutional investors can use for increasing opportunities for MWO firms that we identified in our prior work.[14]

To address our third objective, we reviewed information on the selected federal entities’ use of MWO firms, asset manager selection processes, and related demographic data. We also interviewed federal entity officials and representatives from the consulting firms, industry associations, and research organizations discussed above and from one additional consulting firm.[15] We also obtained views from the two discussion groups with MWO firms and one discussion group and interview with nonfederal retirement plans discussed above and held a discussion group with representatives of five non-MWO firms. Information from these discussion groups and the interview cannot be generalized to all MWO and non-MWO asset management firms and nonfederal retirement plans.

To address our fourth objective, we reviewed SEC documentation and interviewed SEC staff about the status of actions SEC took regarding diversity in the asset management industry. These documents included SEC staff reports, emails to regulated entities, SEC leadership talking points, and SEC press releases. We obtained views on these actions from the industry stakeholders that we interviewed and that participated in our four discussion groups, as described above. As noted earlier, we removed an assessment of SEC staff guidance from our review.

We also obtained information from SEC and the selected federal entities on the extent to which the January 2025 executive orders impacted any activities related to increasing opportunities for MWO firms and from selected federal entities on their efforts to collect and report data on their use of MWO firms. We did not obtain similar information from nonfederal stakeholders that we included in this review. More detailed information on our methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Institutional Investors

Institutional investors are public and private entities that pool funds on behalf of others and invest the funds in securities and other investment assets. Examples include federal, state, and local government entities, as well as private retirement plans, endowments, and foundations. The selected federal entities we reviewed administer or oversee nine plans, consisting of defined benefit retirement plans, defined contribution retirement plans, an endowment, and an insurance program, each with distinct investment objectives (see table 1).[16]

|

Entity |

Plan name |

Type of plan |

|

Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES) |

AAFES Retirement Annuity Plan |

Defined benefit plan |

|

Navy Exchange Service Command (NEXCOM) |

NEXCOM Retirement Plan |

Defined benefit plan |

|

Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board (FRTIB) |

FRTIB Thrift Savings Plan |

Defined contribution plan |

|

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

Federal Reserve System Retirement Plan |

Defined benefit |

|

|

Federal Reserve System Thrift Plan |

Defined contribution |

|

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) |

TVA Retirement System |

Defined benefit plan |

|

|

TVA Retirement System Savings and Deferral Retirement Plan |

Defined contribution plan |

|

Smithsonian Institution |

Smithsonian Endowment |

Endowment |

|

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) |

PBGC Single-Employer Program |

Insurance program |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑106766

In fiscal year 2022, the selected federal entities held nearly $593 billion in externally managed investment assets, representing about a 63 percent increase from $364 billion in 2015.

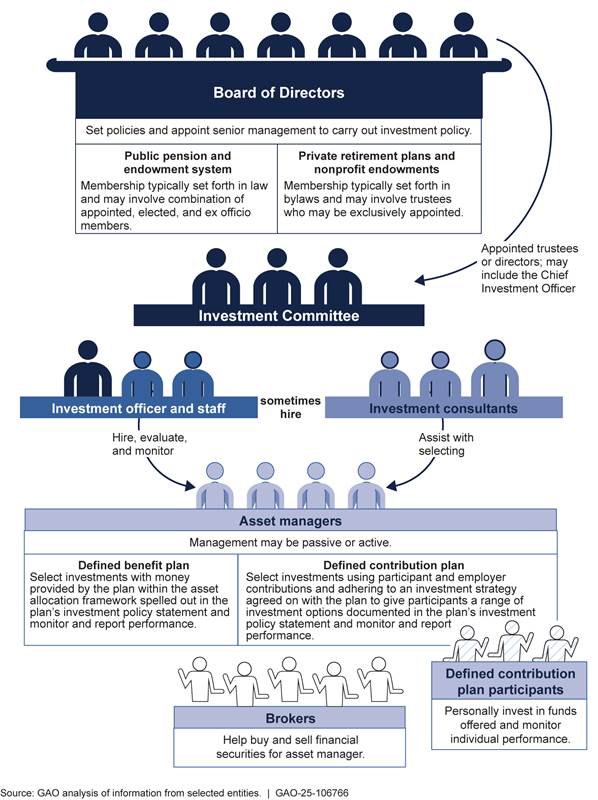

Investment Decisions and Stakeholders in the Investment Process

The selected federal entities we reviewed generally make investment decisions in accordance with investment policy statements approved by boards of directors, trustees, or regents. These statements generally define an asset allocation or mix of asset classes in proportions designed to meet the entity’s overarching investment objectives. For defined contribution plans, participants decide how to allocate their contributions and those made by their employer among investment options offered through the plan. The entities administering these plans may outline these options in the plans’ investment policy statements. For two entities in our review, legislative mandates also specify certain investment decisions, such as asset diversification and investment options.

The federal entities we reviewed are managed by fiduciaries with responsibilities similar to those of private sector retirement plans, requiring them to act solely in the interest of participants and beneficiaries. These responsibilities include acting with the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to the participants and beneficiaries and defraying reasonable expenses of plan administration; carrying out duties prudently; following the plan documents; and diversifying plan investments.

A number of stakeholders are typically involved in the investment process, including investment boards of directors or trustees, investment committees, investment officials and staff, investment consultants, asset managers, and brokers. These stakeholders work together to invest clients’ funds in securities and other types of assets that match their financial objectives (see fig. 1).

As of 2023, over 15,000 investment advisers were registered with or reporting to SEC, categorized as either registered investment advisers or exempt reporting advisers. Collectively, these firms reported $119 trillion in assets as of November 2023. Registered investment advisers managed approximately $114 trillion in assets in 2023, representing a 38 percent increase from the $70 trillion reported in 2017. Exempt reporting advisers reported about $5 trillion in private assets to SEC in November 2023.[17]

Asset Classes and Portfolio Management

Generally, asset management companies invest in or offer participants investments in four major asset classes: equity, fixed income, alternative assets, and cash and cash equivalents (see table 2).

|

Major asset class |

Sample sub-asset classes |

Sample investment strategies |

|

Equity |

Domestic and foreign stocks, mutual funds, and exchange-traded funds that invest in stocks |

Small-, mid-, and large- capitalization, growth, and value |

|

Fixed income |

Corporate and municipal bonds, U.S. securities, and other debt-related instruments |

Core, short duration, and long duration |

|

Alternative assets |

Private equity, venture capital, commodities, real estate, futures, and derivatives |

Event-driven, distressed debt, and absolute return |

|

Cash and cash equivalents |

Cash management, certificates of deposit, and money market funds and other securities with short maturities |

N/A |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106766

Note: Real estate investments can include direct purchase of properties, interests in non-publicly traded entities such as partnerships that invest in real estate, or investments in a real estate investment trust. Hedge funds are commonly described as pooled investment vehicles that are privately organized and administered by professional managers who often engage in active trading of various types of securities and other assets. Private equity funds are commonly described as privately managed pools of capital that invest in companies, many of which are not listed on a stock exchange, and other illiquid assets.

Key Practices for Increasing Investment Opportunities for MWO Firms

In 2017, we identified four key practices that institutional investors, such as retirement plans, can use to increase opportunities for MWO firms.[18]

· Top leadership commitment. Demonstrate commitment to increasing opportunities for MWO firms.

· Remove potential barriers. Review investment policies and practices to remove barriers that limit the participation of smaller, newer firms.

· Outreach. Conduct outreach to inform MWO firms about investment opportunities and selection processes.

· Communicate priorities and expectations. Explicitly communicate priorities and expectations about inclusive practices to investment staff and consultants and ensure those expectations are met.

These key practices are closely related, and improvements or shortfalls in one may contribute to improvements or shortfalls in another. The key practices also do not require investors to develop targets or allocations for MWO firms or change performance standards.

Federal Entities Generally Have Increased Use of MWO Firms, and MWO Firms’ Overall Market Share Has Minimally Increased

Selected Federal Entities’ Use of MWO Firms and Investment in Alternative Assets Has Generally Increased Since 2015

Use of Minority- and Women-Owned Firms

The same five federal plans that we reported as having MWO firms under contract in 2017 continued to do so in 2022. As of 2022, these plans varied in the number of MWO firms they contracted with and the amount of assets they had under MWO firms’ management (see table 3). In total, 61 MWO firms managed approximately 2.8 percent of externally managed assets across the five plans in 2022. Of these 61 MWO firms, 50 managed alternative asset funds, including private equity and real estate. Investments in alternative assets accounted for approximately $1.5 billion, or 37 percent, of the assets managed by MWO firms across the plans.

Table 3: Use of Minority- and Women-Owned (MWO) Asset Management Firms Contracted by Federal Plans, 2022

|

Plan name |

Number of MWO firms contracted by federal plan |

Asset classes managed |

Assets managed (dollars in millions) |

Percentage of external assets managed by MWO firms |

|

Army and Air Force Exchange Service Retirement Annuity Plan |

1 |

Equity |

$139.8 |

3% |

|

Federal Reserve System Retirement Plan |

22 |

Fixed income, alternative assets |

$1,587.4 |

8% |

|

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation Insurance Program |

4 |

Fixed income |

$1,490.0 |

1% |

|

Smithsonian Endowment |

26 |

Alternative assets, Equity and Fixed income |

$694.4 |

2% |

|

Tennessee Valley Authority Retirement System |

9 |

Alternative assets |

$146.0 |

2% |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Reserve, Tennessee Valley Authority, Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, and Smithsonian Institution data. | GAO‑25‑106766

Notes: As of 2022, defined benefit and defined contribution plans administered by the Navy Exchange Service and Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board and the defined contribution plans administered by the Federal Reserve and Tennessee Valley Authority did not use or directly contract with MWO firms. Ownership requirements that asset management firms must meet to be considered MWO vary across different institutional investors and locations. In this table, we relied on identification by the plans of an asset management firm as being MWO.

Three of these five plans reported increasing their use of MWO firms since our prior report. The number of MWO firms used by each plan increased as follows:

· Federal Reserve System Retirement Plan: five firms to 21 firms (2015 to 2022)

· Smithsonian Endowment: 13 firms to 26 firms (2016 to 2022)

· TVA Retirement System: zero firms to nine firms (2016 to 2022)[19]

None of the defined contribution plans we reviewed had MWO firms under contract in either 2015 or 2022.[20] Instead, those plans used large, sometimes publicly owned asset managers that were not identified as MWO firms. For example, the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) is required by statute to offer participants five passively managed funds; four of which are tied to various equity and fixed-income indexes.[21] In 2017, we reported that all of the TSP’s externally managed funds were managed by BlackRock Institutional Trust Company. FRTIB officials told us that the TSP engaged State Street in 2022 to manage one of the four externally managed funds, while the other three remain under BlackRock management. We discuss challenges facing MWO firms when competing for opportunities to work with passively managed funds later in this report.

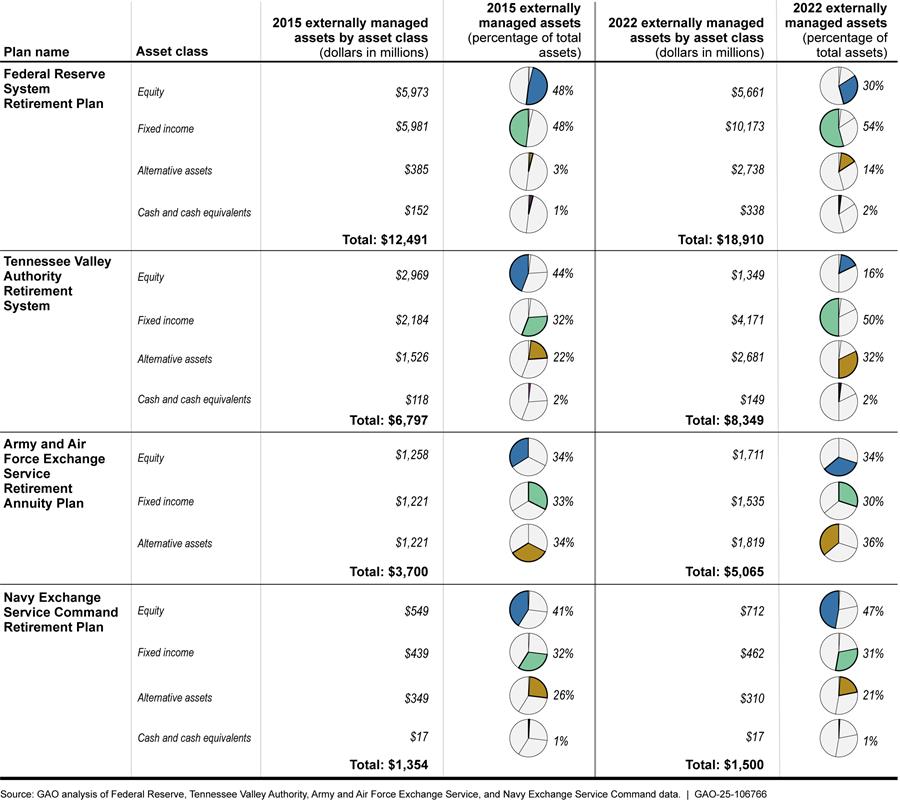

Asset Allocation

Most of the selected federal entities we reviewed have continued to invest in all major asset classes since 2015. In 2022, eight of the nine plans we reviewed primarily invested in equity and fixed income, while two plans had alternative assets as their largest single investment class. As noted earlier, alternative assets include private equity, commodities, real estate, and futures.

Defined benefit plans. Equity and fixed income assets comprised the largest shares of investment for the federal defined benefit plans we reviewed in both 2015 and in 2022 (see fig. 2). Together, these assets accounted for between 64 percent and 84 percent of investments across the defined benefit plans and an average of about 73 percent in total across those plans in 2022.

The amount of alternative asset investments by the defined benefit plans has increased since our prior report. In 2022, these four plans invested between 14 percent and 36 percent of their assets in alternative assets, compared to between 3 percent and 33 percent in 2015. Three of these four plans increased their alternative asset investments from 2015 to 2022, with the largest increase made by the Federal Reserve System Retirement Plan (from 3 percent to 14 percent). NEXCOM Retirement Plan decreased its alternative asset investment from 26 percent to 21 percent during that period.

Figure 2: Externally Managed Asset Allocation for Four Selected Federal Defined Benefit Plans, by Asset Class, 2015 and 2022

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding. In 2015 and 2022, Army and Air Force Exchange Service Retirement Annuity Plan held approximately 1 percent of assets as Cash and Cash Equivalent.

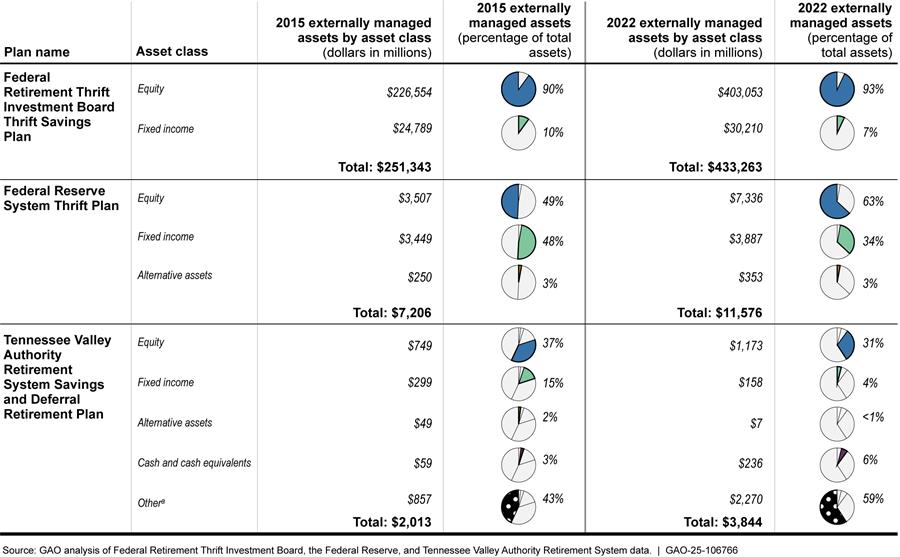

Defined contribution plans. From 2015 to 2022, all three defined contribution plans we reviewed increased their investment in equity and two of the three increased their investment in fixed income assets (see fig. 3).[22]

Figure 3: Externally Managed Asset Allocation by Asset Class for Three Selected Federal Defined Contribution Plans, by Asset Class, 2015 and 2022

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding. The Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board also internally managed $292.6 billion of participant investments in a Government Securities Investment Fund, which invests exclusively in a nonmarketable short-term Department of the Treasury security specially issued to the Thrift Savings Plan.

aThe “other” asset class listed under Tennessee Valley Authority Retirement System Savings and Deferral Retirement Plan consists primarily of participant investment in target date funds that invest predominantly in equity and fixed income and a brokerage window option through which participants can invest in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other securities not offered by the plan.

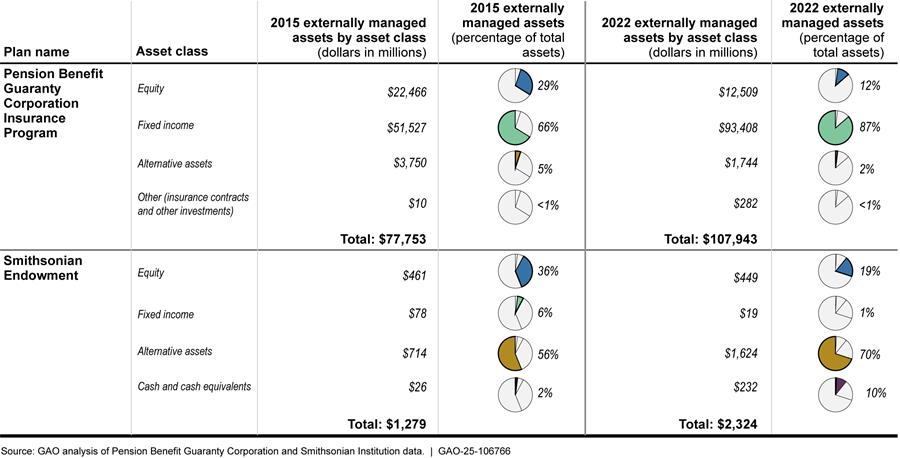

Other plans. As shown in figure 4, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation Insurance Program largely invested in fixed income, increasing its investments in that asset class from 66 percent of total assets in 2015 to 87 percent in 2022. The Smithsonian Endowment’s investments in alternative assets grew from 56 percent of total assets in 2015 to 70 percent in 2022, primarily due to cumulative investment gains.

Figure 4: Externally Managed Asset Allocation by Asset Class of Insurance Program and Endowment, 2015 and 2022

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

MWO Firms Continue to Operate Across All Asset Classes, but Firms’ Market Share Shows Minimal Increases

According to our analysis, in 2022, MWO firms operated across all asset classes in which the selected federal entities invest. We identified 340 asset management firms with some level of MWO ownership registered with or reporting to SEC through publicly available sources, as of October 2023.[23] These MWO firms reported managing almost $1.3 trillion in market assets, accounting for about 1.1 percent of the assets reported to SEC in November 2023.[24]

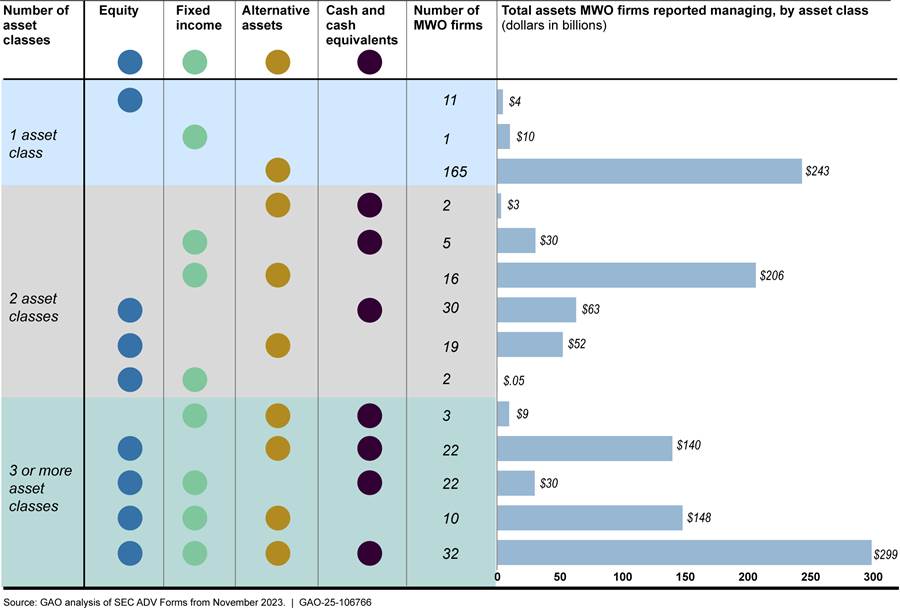

Our analysis showed that these MWO firms generally had a larger market presence as exempt reporting advisers, which manage only private funds or venture capital funds, compared to those that are registered investment advisers. Almost half of the MWO firms we identified manage only alternative assets (see fig. 5). However, the group of MWO firms with the largest amount of assets under management consists of the 32 firms that manage assets across all four major asset classes.

Figure 5: Assets Under Management by Minority- and Women-Owned (MWO) Asset Management Firms by Asset Class, 2022

Note: Asset managers identified as minority- or women-owned by publicly available industry sources and state pension programs. The level of ownership by women and minorities varies and in some cases is not known. Although we did not independently verify ownership, in certain cases we removed asset managers from consideration based on additional information on the firm or review of the firm’s publicly available filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In our prior report, we identified approximately 180 MWO firms through publicly available sources, which reported managing $529 billion. That represented less than 1 percent of the $70 trillion assets in market assets reported to SEC by registered investment advisers in May 2017. Direct comparisons between the 2022 and 2017 data are limited due to differences in the sources used to compile the list of MWO firms. Although the number of MWO firms we identified more than doubled between the two reports, it is unclear whether this increase reflects an actual growth in the number of MWO firms in the market or simply an improvement in the availability of publicly accessible data on MWO firms over time. However, we found that the MWO firms we identified in our prior report also reported managing assets across all four major asset classes.[25]

MWO Firms Face Competitive Challenges, and Federal Entities Incorporated Key Practices in Selecting Firms

MWO Firms Continue to Face Challenges Competing in the Market, According to Industry Stakeholders

According to many federal entity officials and industry stakeholders we spoke with, MWO firms continue to face the same challenges in competing for opportunities in the industry that we reported in 2017.[26] These challenges include the following:

Investor and consultant brand bias. Institutional investors and their consultants may prefer larger asset managers with recognizable or familiar brands, according to some industry stakeholders we spoke with. Many participants in our MWO discussion groups and all our participants in our nonfederal plan discussion group told us that brand bias remains an issue for MWO firms or that their firms have experienced increased consultant brand bias since 2017. Participants in both our MWO firm discussion groups noted the challenges small firms can face in building a brand and competing against large firms with decades of experience.

Industry trends. In our 2017 report, we identified two primary industry trends that posed challenges for MWO firms: the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans and the shift from active to passive management strategies. We reported that MWO firms struggled to compete in defined contribution plans with passive management investment strategies. This is because they often lack the size or resources to keep client fees low, a challenge larger firms can more easily overcome due to their greater capacity and resources.

Federal entity officials and industry stakeholders we spoke with said that MWO firms continue to face similar challenges due to the widespread adoption of passively managed funds. Federal Reserve officials noted that the lack of MWO firms managing passive investments remains a significant obstacle to increasing their use of MWO firms. TVA officials also said that their plan’s strategic focus on lowest-cost fund vehicles and index funds for passive investments has limited their ability to work with MWO firms, as the lowest-cost funds are generally offered by large firms. According to these officials, factors like these will likely continue to affect their entity’s ability to evaluate and consider new MWO firms for their defined benefit and defined contribution plans.

Two industry stakeholders we interviewed and some participants in both MWO firm discussion groups and the nonfederal plan discussion group agreed that the shift from active to passively managed funds has grown since 2017.[27] According to a participant in one MWO discussion group, many institutional investors have abandoned active management in public markets altogether. Another participant from our nonfederal plan discussion group stated that some institutional investors in equity markets now generally view active management strategies as unable to consistently match or outperform passive management benchmarks.

Size and infrastructure. Smaller asset management firms, including MWO firms, often face challenges in meeting threshold requirements set by institutional investors, according to many participants in our MWO firm and nonfederal plan discussion groups, as well as other industry stakeholders and federal entity officials that we interviewed. These requirements may include minimum levels of assets under management, liability insurance, and a certain length of track record.

Representatives from one consulting firm noted that institutional investors do not hire MWO firms because they generally have fewer assets under management than other firms. FRTIB officials echoed this statement, stating that the size of the TSP necessitates working with only a handful of firms that can handle the funds from a fiduciary and insurance perspective. They noted that the criteria used to select asset managers for the TSP include providing a passive index strategy (as mandated by statute) and best value, which is a combination of technical ability and low price. As noted earlier, MWO firms often lack the size or resources to keep client fees low. FRTIB officials said that FRTIB requirements for firms managing TSP funds include having a minimum of $245 billion in assets under management and offering low-cost administrative services, investment services, and insurance—requirements that indirectly exclude smaller firms. As a result, they believe it unlikely that FRTIB would break down the TSP funds to accommodate access for smaller managers.

However, one MWO firm discussion group participant suggested that MWO firms may be finding opportunities in alternative assets, noting that this sector has lower barriers to entry. For example, the participant told us that institutional investors may not have minimum assets under management requirements for managing alternative assets.

Perception of weaker performance. In 2017, we reported that institutional investors may perceive MWO firms as performing more poorly than non-MWO firms. This perception persists, according to two participants in one MWO firm discussion group and most participants in the nonfederal plan discussion group. A representative from one industry association said that investors may assume that MWO firms deliver lower returns than their non-MWO counterparts. A participant in our nonfederal plan discussion group agreed, noting that perceived performance is often cited as a reason for not working with MWO firms.

However, participants in the three asset management discussion groups stated that recent studies have increased transparency around MWO firm performance. One study we reviewed using data from 1992 to 2009 of single-manager U.S. equity mutual funds found no significant performance difference between female- and male-managed funds.[28] Another study we reviewed analyzed data from 1991 to 2019 on single-manager active equity funds and found no significant differences in the performance between white and minority managers.[29]

Selected Federal Entities Made Efforts to Incorporate Key Practices to Increase Opportunities for MWO Firms

In February 2025, representatives from six federal entities told us that they were in the process of developing guidance on how to implement the January 2025 executive orders. Representatives from the Federal Reserve and the Smithsonian Institution said they had not determined whether the orders impacted their entities’ asset management selection processes and continued application of GAO’s key practices for increasing opportunities for MWO firms. Representatives from AAFES, NEXCOM, and PBGC said they did not anticipate changes to their asset manager selection processes because these processes are merit based.[30] Representatives from TVA told us they plan to update their policies to remove any specific references to MWO firms and instruct investment consultants to evaluate and review investment managers without reference to underlying gender and ethnic ownership. Below, we discuss efforts selected federal entities made to incorporate GAO key practices.

As previously discussed, in 2017, we identified four key practices that institutional investors, such as retirement plans, can use to increase opportunities for MWO firms. At that time, we found that three of the seven selected federal entities—Federal Reserve, PBGC, and Smithsonian Institution—had fully incorporated all four key practices into their asset manager selection policies and processes.

For example, the Federal Reserve had removed a potential barrier to MWO firm participation by lowering its minimum requirement for assets under management from $5 billion to $1 billion for its defined benefit and defined contribution plans. Its leadership also participated in meetings and conferences organized by industry associations that represent MWO firms and met with MWO firms individually to conduct outreach.

The remaining federal entities had made partial or no use of the key practices in their asset manager selection processes. We recommended that these entities—AAFES, NEXCOM, TVA, and FRTIB—take steps to fully incorporate the use of all the key practices, which they all did by 2021.[31] For example, in 2017, NEXCOM and AAFES directed their consulting firm to include qualified MWO firms in its database when searching for new asset managers.[32] Additionally, in June 2022, FRTIB introduced an option that allows TSP participants access to a mutual fund window with over 5,000 mutual funds. This mutual fund window includes a screener tool that allows participants to look for different funds, including funds managed by MWO firms, to the extent that such data are publicly available.[33]

For this report, we found that, as of 2023, the asset manager selection practices of all seven federal entities fully incorporated and used the key practices we identified for increasing opportunities for MWO firms. We did not identify any additional actions taken by federal entities to implement the key practices beyond what we previously reported.

At the time of our review, officials from several of the selected federal entities expressed confidence that their actions have led or will lead to an increase in asset management opportunities for MWO firms. For example, PBGC implemented its Smaller Asset Managers Pilot program with a goal of identifying talented, diverse, small, fixed-income managers. PBGC staff said they used the program to identify the MWO firms they currently contract with. The program became permanent in March 2022.

Also, at the time of our review, TVA officials noted that it had become standard practice for them to include, evaluate, and consider MWO firms in their asset management searches. Officials from NEXCOM, PBGC, TVA Retirement System, and Smithsonian told us that since our last report, their hiring consulting firms, when possible, included at least one MWO firm in asset management searches.

However, other factors may continue to limit the opportunities for MWO firms to compete for contracts with federal entities. Specifically, low asset manager turnover and long contracts can impede MWO firms from obtaining opportunities to manage assets for federal retirement plans, according to officials from four federal entities, a representative from a research association, and participants in both MWO discussion groups. For example, officials from NEXCOM stated that only three asset manager contracts have become available for the entity’s defined benefit plan in the last 6 years.

Federal Entities Collected Data on MWO Firm Use but Barriers Limited Data Consistency

The extent of reporting on the use of MWO firms varied among the federal entities we reviewed. Inconsistent data collection and reporting methods pose challenges to identifying and tracking MWO firms. Industry stakeholders are working to standardize data collection, but barriers remain.

Additionally, in February 2025, representatives from the Federal Reserve and the Smithsonian Institute told us that they had not yet determined how, if at all, the January 2025 executive orders impact their entities’ collection and usage of MWO firm data.[34] Representatives from AAFES, PBGC and NEXCOM told us that they follow a merit-based approach in selecting qualified firms, regardless of their MWO status. Representatives from TVA told us they will no longer collect any demographic data from its current and prospective asset managers. Therefore, we discuss the status, at the time of our review, of the selected federal entities’ efforts to collect and use MWO firm data.

Two Selected Federal Entities Reported on Their MWO Firm Use and All Collected Data on Asset Manager Diversity

Among the selected federal entities, FRTIB and the Federal Reserve are required to report on their use of MWO firms. Although the other five are not required to report on MWO firm use, Smithsonian reported information voluntarily. Additionally, while all entities collected data on the diversity of their asset managers, they had different approaches to identifying and classifying MWO firms.

Reporting on Use of MWO Firms

FRTIB is required by the Thrift Savings Plan Enhancement Act of 2009 to submit annual reports to Congress on the demographics of its asset managers. As of 2022, no MWO firms manage funds for the TSP. However, FRTIB’s 2022 report included employee demographic information from both of Thrift Savings Plan’s investment managers.[35]

Federal Reserve officials noted that the Board of Governors and the Federal Reserve Banks are subject to Section 342 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which requires certain agencies to submit an annual report to Congress reporting on their use of MWO firms. These officials said that because the Board of Governors and the Federal Reserve Banks are the plan sponsors of the Federal Reserve System’s benefits plans, the Federal Reserve Office of Employee Benefits determined that it was appropriate to file an annual report for the years before 2023.[36]

Federal Reserve officials also said that public reporting helps demonstrate the agency’s commitment to including MWO businesses in its procurement and other activities. The Federal Reserve’s 2023 annual report includes the number of MWO firms managing funds for its retirement plans, the amount of assets they manage, and its planned commitments to MWO firms.[37] The report also describes Federal Reserve’s efforts to increase access to investment opportunities for MWO firms within its retirement plans and gather data on diversity and inclusion metrics and policies among its asset managers.

The other five federal entities we reviewed are not required to report on their use of MWO asset managers, according to officials. However, at the time of our review, Smithsonian’s Office of Investments voluntarily published an annual diversity and inclusion report that included the percentage of the Smithsonian Endowment’s assets under management that are overseen by MWO firms. The report further broke down the percentage by the ownership race and ethnicity of the firms.[38] It also included Smithsonian’s efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in its investment practices, including efforts to identify MWO firms. According to Smithsonian Institution officials, the annual report aimed to provide transparency into the Institution’s priorities and efforts to increase diversity and inclusion in its investment practices. They said it sought to demonstrate Smithsonian’s commitment to a fair and inclusive process for selecting the best investment managers in each asset class.[39]

Efforts to Identify MWO Firms

The federal entities we reviewed had different approaches to identifying MWO firms.[40] At the time of our review, officials from NEXCOM, TVA, AAFES, and PBGC said they relied primarily on their consulting firms to identify whether a firm is MWO. PBGC also used its existing knowledge and industry outreach to identify MWO firms, as part of PBGC’s smaller asset managers program. FRTIB officials said it does not identify MWO asset managers because only a few firms in the U.S. can manage the TSP due to its size.[41]

Instead of relying on consultants, officials of the Federal Reserve and Smithsonian Institution said they primarily identified MWO firms internally. Federal Reserve officials said its real estate consulting firm identified potential MWO firms for its portfolio. However, they said the Federal Reserve identified MWO firms primarily by building relationships with trade organizations, fund-of-funds, and broker dealers, and by using those entities’ informal databases.[42] In addition, Federal Reserve officials said the entity included diversity-related questions in its requests for proposals, covering applicants’ policies, procedures, and diversity metrics. Smithsonian Institution officials said the institution did not use consulting firms to identify MWO firms but requested demographic data from U.S.-based external managers to help officials identify demographic characteristics of potential asset management firms’ owners.

Definition of MWO Firms

The selected federal entities had varying approaches to classifying firms as minority- or women-owned in their data collection. The main difference lay in the ownership threshold required. The four entities that relied on consulting firms to identify MWO firms used the consulting firm’s definition of an MWO firm. Three entities used the same consulting firm, which used a threshold of roughly 50 percent diverse ownership, according to representatives of the firm.[43]

The Federal Reserve used a 20 percent threshold to define ownership by women or minorities, according to officials. Smithsonian Institution officials said they defined MWO firms as being 50 percent or more diverse owned, having recently lowered this threshold from 51 percent to accommodate firms with equal partners.

Industry Stakeholders Have Taken Steps to Standardize Demographic Data Collection, but Barriers Limit Consistency

According to industry stakeholders in our three asset management firm discussion groups and in many of our interviews, demographic data collection in the asset management industry is inconsistent. Consultants and institutional investors typically use customized data collection instruments, leading to variability in data gathering. Further, as discussed earlier, the federal entities differed in how they collected demographic data on asset managers—for example, some used their own questionnaire, while others relied on consulting firms. These differences in data collection methods created inconsistencies in the types of data collected across entities.

Consistent with this observation, our review found that federal entities varied in the types of data they possessed. For example, the five federal entities with MWO firms under contract provided us with some ownership demographic data, but the level of detail differed. Table 4 describes federal entities’ investment with MWO firms at the level of detail the agencies were able to provide, along with their varying definitions of MWO firms. Four entities supplied the number of MWO firms they worked with, as well as the race or ethnicity of the minority firms’ ownership. However, officials said AAFES could provide the number of MWO firms but not the race or ethnicity of their ownership, due to its consulting firm’s data collection methods.[44]

Table 4: Demographic Breakdown of Minority- and Women-Owned (MWO) Asset Management Firms Contracted by Federal Plans That Invested with MWO Asset Management Firms, Fiscal Year 2022

|

Plan |

Plan definition of MWO firm |

Reported number and type of MWO firms invested with |

|

Federal Reserve System Retirement Plan |

20 percent or higher MWOa |

The plan invested with 22 total MWO firms: · Two firms were women-owned, · seven were African American-owned, · four were Hispanic American-owned, · five were Asian American-owned, · two were Middle Eastern American-owned, · one was women- and African American-owned, and · one was owned by another racial or ethnic minority. |

|

Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES) Retirement Annuity Plan |

More than 50 percent MWOb |

The plan invested with one MWO firm that was 18 percent minority-owned and 40 percent women-owned.c |

|

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) Insurance Program |

At least 51 percent MWOd |

The program invested with four total MWO firms: · One firm was 50 percent women-owned, 11 percent Asian American owned, and 11 percent Middle Eastern American-owned; · one was 58 percent women-owned; · one was 42 percent women-owned, 56 percent African American-owned, and 26 percent Asian American-owned; and · one was at least 55 percent minority-owned.e |

|

Smithsonian Endowment |

50 percent or more MWO |

The endowment invested with 26 total MWO firms: · Seven firms were women-owned, · six were African American-owned, · three were Hispanic American-owned, · nine were Asian American-owned, · and one was woman and Asian American-owned. |

|

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) Retirement System |

More than 50 percent MWOb |

The system invested with nine total MWO firms: · One firm was women-owned, · two were African American-owned, · two were Hispanic American-owned, and · four were Asian American-owned. |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Reserve, AAFES, PBGC, Smithsonian Institution, and TVA reported data. | GAO‑25‑106766

aThe Federal Reserve’s Office of Employee Benefits used a 20 percent threshold to define MWO firms, but representatives said most of the firms they work with have over 50 percent minority ownership.

bAAFES and TVA relied on their consulting firm’s definitions of MWO firms, which has a 50 percent threshold but also will consider firms near but below this threshold based on facts and circumstances, according to representatives of that consulting firm.

cDue to overlap between the two groups (minority-owned and women-owned), the firm had 56 percent MWO ownership.

dOfficials said that PBGC adhered to the Federal Acquisition Regulation’s (FAR) classification of socio-economic categories. The FAR defines these categories, such as women-owned small businesses, as being at least 51 percent owned by members of that socio-economic category.

ePBGC was unable to provide more detailed demographic information on the fourth firm it contracted with in 2022 because it no longer contracts with that firm.

To address inconsistent data collection within the asset management industry, several industry associations and private companies have developed standardized questionnaire templates for asset management firms to use. The two publicly available templates we reviewed are intended to enhance asset owners’ understanding of vendor demographics and diversity practices, reduce administrative burden, and establish consistent reporting metrics for long-term data assessments. Both generally asked for quantitative information, such as the number or percentage of ownership and employees by race and gender. They also requested qualitative information, such as information about firms’ diversity-related policies and procedures.

While the entities that created the templates collaborated on their efforts, there are some differences between them. For example, for staff-level data, one template requests data on the portfolio management team, while the other requests data by employee title. Also, while both templates ask a series of yes and no questions about whether firms have diversity-related policies and procedures, one also asks yes and no questions about the content of firms’ policies and programs, while the other asks firms to provide narrative descriptions of such policies and programs.

Representatives from one industry association with a template said that its efforts to collaborate with other industry organizations on standardizing data collection and definitions are ongoing. However, according to representatives in some of our interviews with consulting firms and both MWO firm discussion groups, the adoption of standardized templates has been inconsistent, with many industry participants continuing to prefer their own data collection tools. Asset managers are reluctant to use a standard template because consulting firms typically prefer their own due-diligence questionnaire, according to representatives of one consulting firm. Participants in both MWO firm discussion groups said that investors and consulting firms often create their own surveys for asset management firms to complete. An industry research organization representative noted that each investor requests data from firms differently.

Investors can also obtain demographic data on asset management firms through private companies. Such companies collect and aggregate demographic data, along with other metrics, to help clients evaluate asset management firms, according to representatives from one industry research organization and participants in our nonfederal plan discussion group and interview.

However, industry stakeholders in our discussion groups and interviews cited four key barriers to collecting consistent demographic data on asset management firms: defining MWO firms, inconsistent reporting protocols, privacy concerns, and data quality.

· Defining MWO firms. According to representatives of industry stakeholders in some of our interviews, stakeholders have varying criteria for determining MWO ownership thresholds. For example, representatives of the Institutional Investing Diversity Cooperative told us its members use ownership thresholds ranging from 30 percent to 51 percent minority or women ownership to designate a firm as MWO. Representatives from three of the five consulting firms we spoke with said they formally define diverse firms as being over 50 percent owned by minorities or women. However, representatives from one of those firms said their firm takes a holistic approach, considering metrics beyond ownership levels, such as leadership and organizational diversity. This allows firms with diverse ownership levels as low as 30 percent to be considered MWO.[45]

Some definitions of diversity encompass categories beyond race and gender, such as veteran status, disability, or sexual orientation. Participants in the nonfederal plan discussion group said that they collect data on those metrics. Additionally, one industry association that maintains a database of MWO firms said it now allows reporting data on disability and sexual orientation. Participants in two of our three asset management discussion groups mentioned being asked to report data on ownership veteran status.

· Inconsistent reporting protocols. Participants in all of our asset management discussion groups said demographic data are often requested in a variety of formats, including requests for proposals, due diligence questionnaires, survey templates, and online platforms. Participants in both MWO firm discussion groups noted that while providing the data is not itself difficult, reporting the data in multiple formats can be cumbersome. Three of the six industry associations and research organizations we spoke with said this inconsistency can cause administrative challenges or frustration for asset management firms.

Participants in one MWO firm discussion group and the non-MWO firm discussion group cited the potential for standardized demographic data to help institutional investors identify diversity gaps in firms, among other benefits. Furthermore, participants in both MWO firm discussion groups suggested that having a centralized database for demographic data would reduce the reporting burden on small firms lacking the administrative resources of larger firms.

· Privacy and effect on business opportunities. MWO firms may want to keep ownership or employee demographic data private to safeguard personal information and avoid potentially limiting their firm’s opportunities.[46] One industry research organization said some smaller firms that cannot anonymize data have objected to demographic data requests, citing privacy concerns about sharing information on disability or sexual orientation.

Representatives of two stakeholder organizations we interviewed and participants in one of our MWO firm discussion groups said that identifying as an MWO firm might restrict opportunities. For example, representatives from one industry research organization said that some MWO firms may avoid identifying as such out of fear that they will be relegated to emerging or small allocation portfolios, despite possessing the qualifications to compete for larger portfolios.

· Data quality. Stakeholder representatives in some of our interviews and participants in both of our MWO discussion groups expressed concerns that data quality may be compromised by firms overstating their diversity. Representatives of one consulting firm said firms may falsely claim ownership—such as naming the spouse of the actual owner—to appear more diverse. Participants in our MWO firm discussion groups noted actual owners may inaccurately claim membership in a particular racial or ethnic group or firms may report data that include the statistics of staff in noninvestment roles, who may be more diverse, to make their firm appear diverse in the aggregate, despite limited diverse staff being in investment roles.

Inconsistent data reporting also can undermine data quality. Representatives of one consulting firm said that some firms refuse to disclose any demographic data. Participants in our nonfederal discussion group and interview similarly stated that some firms, especially private ones, are hesitant to report demographic data. However, they observed that firms’ willingness to respond to data requests has generally been improving over time.

Stakeholders Cited Factors to Consider in Demographic Data Collection

Industry stakeholders we interviewed cited several factors to consider in collecting demographic data on asset management firms:

Data utility and decision-making. According to representatives of one industry research organization, collecting data is not useful if the decision-makers do not identify actions they plan to take based on the data.

Additional demographic data. Representatives from an association that created a standardized template said they include team-level demographic data, including investment professionals and leadership, because research they have reviewed shows ownership structure does not affect client returns. Similarly, some stakeholder representatives we interviewed told us they focus on leadership and staff diversity beyond ownership because it provides a broader view of diversity in the industry.[47] Representatives of an industry research organization said they review funds invested with MWO firms rather than just commitments, as many entities prefer to report fund commitments before those funds are actually allocated to MWO firms. Participants in one of our MWO firm discussion groups said that collecting data on staff diversity and a firm’s approach to diversity could be helpful to those seeking to better understand a firms’ commitment to diversity.

Data collection challenges. Some plans need to budget additional funds to hire companies to survey their asset management firms for demographic data, according to representatives from one nonfederal plan we interviewed. This can be a challenge for smaller plans with limited resources, according to those representatives. Participants in our nonfederal plan discussion group also highlighted the importance of investing in a provider to collect demographic data, as gathering it internally can be too time-consuming and resource intensive.

Legislative requirements can also have an impact. A nonfederal plan representative we interviewed mentioned that a state legislature’s requirement to report on asset manager demographic data encouraged them to take collection and reporting of demographic data more seriously.

Benefits of demographic data collection. Participants in our nonfederal plan interview and discussion group emphasized the importance of considering the benefits for plans and MWO firms of collecting and reporting demographic data. For example, one nonfederal plan representative we interviewed said that publicly sharing information on its use of MWO firms could help plans benchmark their progress against peers, identifying areas of strength and improvement. Similarly, participants in our nonfederal plan discussion group noted that public reporting of demographic data could help break down biases, introduce plans to new potential partners, and encourage MWO firms to bid on contracts with institutional retirement plans by showing that other MWO firms had success doing so.

Status of SEC Efforts Regarding Diversity in Asset Management

In February 2025, SEC staff said that in response to the January 2025 executive orders, they removed staff guidance from the SEC website that addressed investment advisers’ consideration of DEI factors when recommending or selecting other advisers.[48] As a result, we removed our assessment of this guidance from our review.[49] SEC staff also told us that they were analyzing the potential impact of the executive orders on their activities related to promoting and collecting diversity policies and practices through SEC’s diversity self-assessment form for its regulated entities.

SEC’s OMWI introduced this form, known as the Diversity Assessment Report for Entities Regulated by the SEC, in January 2018.[50] The form is intended to help regulated entities—including asset managers registered as investment advisers—self-evaluate their diversity policies and practices and collect demographic information for submission to SEC OMWI. The form supports the Joint Standards for Assessing Diversity Policies and Practices of Entities Regulated by the Agencies, issued in 2015 by SEC and other federal financial regulators.[51] SEC and the regulators issued these standards in response to a Dodd-Frank Act requirement to develop standards for assessing the diversity policies and practices of the entities they regulate.[52]

In 2023, SEC OMWI staff streamlined the form and renamed it the Diversity Self-Assessment Tool. As with the prior form, this revised form collects information on diversity policies and practices; demographic details on firm diversity, including gender, race, and ethnicity; and supplier diversity (see text box).[53]

|

Diversity Self-Assessment Tool for Entities Regulated by SEC SEC created the Diversity Self-Assessment Tool (formerly the Diversity Assessment Report) to help guide and inform a regulated entity’s self-assessment of its diversity and practices. The Diversity Self-Assessment Tool has three sections: section I collects information on the entity, section II requests the entity’s assessment of its diversity policies and practices, and section III requests its diversity data. Diversity policies and practices. Section II asks entities whether they take certain steps related to promoting diversity and inclusion in five areas: 1. Organizational commitment to diversity and inclusion. This section focuses on leadership commitment to diversity and inclusion, including whether the entity has a written diversity and inclusion policy that is supported and approved by the entity’s leadership. 2. Implementation of employment practices to promote workforce diversity and inclusion. This section asks about an entity’s promotion and implementation of its diversity and inclusion practices, including whether the entity conducts outreach to minority and women organizations as a source for potential hires for the regulated entities. 3. Procurement and business practices—business diversity. This section focuses on an entity’s efforts to broaden its pool of available business options by increasing outreach to minority and women-owned businesses. 4. Practices to promote transparency of organizational diversity and inclusion. This section focuses on making public an entity’s commitment to diversity and inclusion to inform investors, employees, customers, and others about its efforts. It includes questions such as whether the entity publicizes its commitment to diversity and inclusion or its progress toward achieving diversity and inclusion in its workforce and procurement activities. 5. Self-assessment of diversity policies and practices. This section focuses on an entity’s efforts to monitor and evaluate its performance under its diversity policies and practices on an ongoing basis and whether an entity publishes information pertaining to its assessment of its diversity policies and practices. Diversity Data. Section III requests data on the demographic composition of an entity’s workforce and management by gender, race, and ethnicity. It also requests the dollar amount and total percentage of an entity’s procurement spending with MWO businesses. |

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). | GAO‑25‑106766

SEC encourages regulated entities to submit this self-assessment to SEC OMWI every 2 years. SEC OMWI uses the reported information to monitor industry progress, identify trends, and highlight successful diversity practices. Conducting and submitting self-assessments, including using the SEC’s self-assessment tool, is voluntary.[54]

According to SEC OMWI’s 2022 summary report on diversity policies and practices, SEC OMWI staff invited approximately 1,300 regulated entities with over 100 employees to submit their self-assessments. SEC OMWI received 58 responses, representing more than 90 regulated entities.[55] The vast majority of regulated entities did not submit a self-assessment. The report noted that most respondents demonstrated an organizational commitment to diversity and inclusion and employed practices promoting workforce diversity and inclusion. Additionally, many monitored and publicized their workforce diversity progress. However, the report also noted that few entities reported having supplier diversity policies and practices in place or publicizing supplier diversity progress. Additionally, less than half the firms reported using the joint standards or publishing the results of their self-assessments.

Most industry stakeholder representatives we spoke with had limited familiarity with the diversity self-assessment form, and therefore had few comments on its effectiveness. More specifically, most participants in four of our discussion groups and in our interview with nonfederal plans said they were not familiar with the diversity self-assessment form. Among representatives of consulting firms we interviewed, one used the form alongside the company’s own questionnaire, while another was unfamiliar with it.

The 2022 summary report noted that the industry’s low response rate for submitting self-assessments creates a substantial knowledge gap for SEC, underscoring the need for greater participation to better understand workforce and supplier diversity policies and practices in the financial securities industry. To increase participation for the 2024 collection year, SEC OMWI staff said they raised awareness about the Diversity Self-Assessment Tool and collaborated with the office’s leadership on outreach and communication strategies. These efforts included emails to regulated entities, press releases, social media posts, lunch-and-learn events, and requests for SEC leadership to promote the report. Additionally, SEC OMWI staff streamlined the self-assessment form with changes including adding clarifying language to items, combining some items, and removing some items.

In February 2024, the SEC Investor Advisory Committee sent a letter to the Acting Director of SEC OMWI, highlighting the low participation rate in regulated entities submitting self-assessments and the resulting knowledge gap regarding diversity policies and practices in the industry.[56] The letter also cited SEC’s activities to streamline the reporting process for the 2024 collection period. The Investor Advisory Committee expressed support for the streamlining and encouraged SEC OMWI to continue its outreach to regulated entities to boost submission of diversity assessment reports.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to AAFES, Federal Reserve, FRTIB, SEC, Smithsonian Institution, PBGC, NEXCOM, and TVA Retirement System for review and comment. Federal Reserve, FRTIB, SEC, and Smithsonian Institution, provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

The draft report that we sent to the federal entities and SEC included analysis and a recommendation to SEC regarding SEC staff guidance that addressed investment advisers’ consideration of DEI factors when selecting or recommending other advisers. Given that SEC staff removed the staff guidance from the SEC website pursuant to the January 2025 executive orders, we removed the related analysis and draft recommendation from the report because they were no longer relevant.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Executive Director of the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, the Acting Director of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, the Acting Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Tennessee Valley Authority, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Michael E. Clements at clementsm@gao.gov or Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen at nguyentt@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Michael E. Clements

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen,

Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

List of Requesters

The Honorable Cory A. Booker

United States Senate

The Honorable Tim Kaine

United States Senate

The Honorable Ben Ray Luján

United States Senate

The Honorable Patty Murray

United States Senate

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

United States Senate

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Al Green

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Alma S. Adams

House of Representatives

The Honorable Joyce Beatty

House of Representatives

The Honorable Al Lawson

House of Representatives

The Honorable Juan Vargas

House of Representatives

The Honorable Nikema Williams

House of Representatives

This report discusses (1) changes since our last report regarding selected federal entities’ use of minority- and women-owned (MWO) asset management firms and the major asset classes in which they invest; (2) reported challenges faced by MWO firms in competing for work, and selected federal entities’ efforts to align with key practices for increasing these firms’ opportunities; (3) selected federal entities’ data collection on their use of MWO firms and challenges to consistent reporting; and (4) the status of actions by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regarding diversity in the asset management industry.

Our review focused on seven federal retirement plans, one endowment, and one insurance program. These were selected because they were administered or overseen by seven of the entities reviewed in our 2017 report.[57] These seven entities are Army and Air Force Exchange Service; the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board (FRTIB); Smithsonian Institution; Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC); Navy Exchange Service Command; and Tennessee Valley Authority.[58] Those entities had been selected for our 2017 report because they oversaw large federal plan and investments with different sizes (assets of more than $1 billion) of varying types and strategies.[59]

Additionally, two executive orders issued in January 2025, during our audit work, directed federal agencies to end diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) initiatives and programs.[60] We obtained information from SEC on the extent to which these orders impacted activities related to increasing opportunities for MWO firms. SEC staff said that, in response to the orders, they removed staff guidance from the SEC website that addressed investment advisers’ consideration of DEI factors when recommending or selecting other investment advisers.[61] Accordingly, we removed an assessment of this staff guidance from our review.[62]

We also obtained additional information from the selected federal entities on the extent to which these executive orders impacted any activities related to increasing opportunities for MWO firms and collecting and reporting data on their use of MWO firms. We did not obtain similar information from nonfederal stakeholders we included in this review.

Selected Federal Entity Use of MWO Firms and Asset Allocation of Selected Federal Plans

To address our first objective, we reviewed 2022 data provided by the selected federal entities on the number of asset managers that the entities or their consulting firms identified as MWO firms and the amount of assets they had under MWO firms’ management by major asset class. We also reviewed information provided by each federal entity on the demographic characteristics of each MWO firm under contract in 2022. We compared the 2022 data on MWO firm usage to the data previously provided to us by the federal entities (which were from 2015 or 2016, depending on the federal entity).

To assess the reliability of federal entities’ data on MWO firm usage, we interviewed representatives of the selected federal entities and their consulting firms, as appropriate, with knowledge of the systems and methods used to produce these data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for purposes of estimating federal entities’ use of MWO asset managers in 2022.

To determine the major asset classes in which the selected federal entities invest, we obtained data from the federal entities on the allocations they made to each asset class in 2022 from their annual reports and audited financial statements. We compared each federal entity’s 2022 asset allocation data to its 2015 asset allocation data as reported in our 2017 report.[63]

To determine the 2022 market presence of MWO firms in the asset classes invested in by the federal entities in our review, we reviewed publicly available directories and databases of MWO asset managers compiled by industry stakeholders. We identified these directories and databases by searching prior GAO reports and conducting systematic web and database searches in July and August 2023.[64] Using these directories and databases, we created a preliminary list of MWO firms.[65]

We interviewed representatives of the organizations that compiled these directories or databases of MWO firms to understand how the data were collected and how MWO firms were defined. We included firms on our list that were confirmed by the sources to have some level of minority or women ownership and that published information on the demographic characteristics of their owners.[66]

We determined each firm’s registration status with SEC by reviewing the SEC’s Investment Adviser Public Disclosure database.[67] If a firm was not a registered investment adviser or exempt reporting adviser, we removed it from our list.[68] For the remaining firms, we downloaded their Form ADV filings from the database to identify the asset classes in which they operate and the assets they reported managing.[69]

We compared the total assets reported by MWO firms we identified to the total assets under management reported by all registered investment advisers and exempt reporting advisers in the database as of November 2023.[70] We also compared this information to the 2017 data previously reported, although differences in how we compiled the 2017 and 2022 lists of MWO firms limit direct comparisons. Specifically, while the number of MWO firms we identified more than doubled between the two reports, we cannot determine whether this increase was due to a rise in the actual number of MWO firms in the market or an improvement in the availability of information and data sources during that time frame.