DISASTER ASSISTANCE

Updated FEMA Guidance Could Better Help Communities Apply for Individual Assistance

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106768. For more information, contact Chris Currie at curriec@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106768, a report to congressional committees

Updated FEMA Guidance Could Better Help Communities Apply for Individual Assistance

Why GAO Did This Study

FEMA’s IA program provides help to individuals to meet their immediate needs after a disaster, such as shelter. When a state, territorial, or tribal government requests IA through a major disaster declaration, FEMA evaluates the request against IA declaration factors such as uninsured home losses and makes a recommendation to the President. The President declares the disaster or denies the request.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to review the IA declaration factors. This report addresses (1) trends in IA disaster declarations; (2) the resources FEMA uses to help states understand the IA declaration process and the extent to which this information is updated; and (3) the extent to which FEMA uses information on vulnerable populations when making recommendations for IA declarations.

GAO analyzed data from FEMA’s disaster declaration system from fiscal years 2015 through 2018 and fiscal years 2020 through 2023—the time periods before and after 2019 when FEMA revised its IA declaration factors. GAO also reviewed agency documentation, and interviewed officials from FEMA and a non-generalizable selection of 11 states.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that FEMA take steps to ensure that its IA guidance reflects updated data, and that this information is regularly updated in FEMA’s guidance and on its website. DHS concurred with this recommendation.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) revised its Individual Assistance (IA) declaration factors in 2019, which included incorporating a factor on state fiscal capacity. In fiscal years 2015 through 2023, the percentage of IA requests that were approved by the President increased. Specifically, 55 percent of requests (56 of 102) for IA were approved in fiscal years 2015 through 2018. This increased to 62 percent of requests (78 of 126) approved for IA in fiscal years 2020 through 2023.

FEMA provides training and other resources to help states understand the IA declaration process but uses outdated information to convey the likelihood of approval. When evaluating an IA declaration request, FEMA considers a state’s cost-to-capacity ratio, which measures the estimated cost of assistance relative to the state’s capacity to respond to a disaster. The higher the ratio, the more likely FEMA will approve an IA request. FEMA’s IA guidance discusses how this ratio helps states understand the likelihood of IA approval and includes a table with historical approval rates of IA declarations for each range of ratios. However, the approval rates are based on data from 2008 through 2016. GAO found that using data from 2020 through 2023 would increase the IA approval rates across all ratio ranges. By updating this table regularly, FEMA could communicate a more accurate likelihood of approval to states. This could better inform states’ decisions on whether to request IA and help communities receive needed assistance after a disaster.

FEMA uses information on vulnerable populations, such as poverty rates, in its declaration process and is taking steps to better support small states and rural areas. For example, this information is used in developing Preliminary Damage Assessments that help determine whether federal assistance is needed. Since being appointed in 2023, FEMA’s Small State and Rural Advocate has conducted listening sessions with stakeholders in small states and rural communities to understand their needs for the declaration process.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

cost-to-capacity ratio |

Individuals and Households Program Cost to Capacity ratio |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

IA |

individual assistance |

|

IA declaration |

major disaster declaration authorizing IA |

|

Stafford Act |

Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act |

|

SVI |

Social Vulnerability Index |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 14, 2025

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

Each year, natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, and wildfires affect hundreds of American communities. In January 2025, historic wildfires in Los Angeles County destroyed over 16,000 homes and commercial properties, causing thousands of evacuations and at least 29 deaths. In September and October 2024, Hurricanes Helene and Milton hit the southeastern United States within 13 days of each other, causing unprecedented flooding and damage to affected areas. Federal disaster assistance is a critical resource for helping communities, businesses, and individuals respond to and recover from natural disasters, public health emergencies, and more. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), within the Department of Homeland Security, leads our nation’s efforts to prepare for, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the risk of disasters. Under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act), state, territorial, and tribal governments may seek federal assistance by requesting a major disaster declaration if an incident overwhelms their resources.[1]

Several types of assistance from FEMA may be requested by the state or tribal government in the major disaster declaration request, including Individual Assistance (IA) to help individuals and families meet their immediate needs after a disaster, such as shelter. IA consists of several programs, such as the Individuals and Households Program, which provides financial assistance and direct services to eligible individuals and households who have uninsured or underinsured necessary expenses and serious needs resulting from a major disaster. To obtain IA for its disaster survivors, a state or tribal government must request a major disaster declaration authorizing IA (IA declaration) through FEMA.[2] FEMA then determines whether to make a recommendation to the President to declare a major disaster and whether to recommend that the President approve IA within the declaration. In 2024, there were 27 disasters with at least $1 billion in damages, and FEMA provided over $4 billion in assistance to survivors through the Individuals and Households Program.[3]

In recent years, FEMA has faced an unprecedented demand for its services and played an increasing role in various disasters and emergencies. As the number and severity of disasters have increased, questions have been raised about FEMA’s ability to assist all people who qualify for services. Additionally, according to FEMA’s 2022-2026 Strategic Plan, disasters impact people and communities differently. Underserved communities or vulnerable populations often suffer disproportionately from disasters. For example, people in rural and tribal communities may live in places where weakened infrastructure, fewer resources, and less support may compound a disaster’s impact. FEMA’s 2022-2026 Strategic Plan identifies several objectives to help the agency meet the needs of vulnerable populations. Further, the Stafford Act requires FEMA assistance to be delivered without discrimination on the grounds of race, color, religion, nationality, sex, age, disability, language accessibility, or economic status.[4]

In 2018, we reported on FEMA’s process for recommending IA declarations nationwide.[5] We found that FEMA did not consistently obtain and document information it used to recommend IA declarations. We also found that states identified confusion about the factors FEMA used when assessing IA declaration requests. We recommended that FEMA evaluate why FEMA regions are not completing their recommendations for each element of the IA factors and take corrective steps, if necessary. FEMA has addressed this recommendation by surveying FEMA region officials, developing and issuing an updated template, new guidance, and a memorandum to regional administrators. In 2019, FEMA revised the factors it uses to assess IA declaration requests.[6] These factors are (1) state fiscal capacity and resource availability, (2) uninsured home and personal property losses, (3) disaster impacted population profile, (4) impact to community infrastructure, (5) casualties, and (6) disaster related unemployment.[7]

Section 5601(b) of the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for us to conduct a review of the implementation of the revised factors that FEMA considers when evaluating a governor’s request for a major disaster declaration requesting IA.[8] This report addresses

1. trends in major disaster declarations, including after the IA declaration factors were revised in 2019;

2. the resources FEMA uses to help states understand the IA declaration process and the extent to which this information is updated; and

3. the extent to which FEMA uses information on vulnerable populations when making recommendations for IA declarations.

To describe trends in disaster declarations since the IA factors’ revision in 2019, we obtained and analyzed data from FEMA’s systems for disaster declaration requests made by states in fiscal years 2015 through 2018 and fiscal years 2020 through 2023, the most recent data available at the beginning of our review.[9] The revised factors took effect on June 1, 2019. To compare the trends before and after the revised factors took effect, we excluded data from fiscal year 2019. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed the data and discussed data quality control procedures with FEMA officials. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. Our analysis did not seek to identify the cause of or reason for any trends in IA disaster requests or declarations. We interviewed officials in FEMA headquarters and all 10 FEMA regions to provide context around the trends observed in our data analyses of IA disaster declarations.

To describe the resources FEMA uses to help states understand the IA declaration process and the extent to which information is updated, we obtained cost-to-capacity ratios, a measure of the estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program against a state’s total taxable resources, from FEMA’s Preliminary Damage Assessments for major disasters declared after the IA declaration factors were revised in 2019. The cost-to-capacity ratios act as a gauge to help determine whether the state has the capacity to meet the housing and other needs of the affected communities.

To assess the extent to which FEMA has updated its IA guidance to help states understand the declaration process, we analyzed approval rates for IA requests from FEMA’s systems for major disaster declaration requests made by states in fiscal years 2020 through 2023, the most recent data available at the time of our review. We compared these results against FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance, which includes a table of ranges of cost-to-capacity ratios and the percentage of IA requests that had been approved in prior years for each range to help states understand the likelihood of IA approval. The percentages listed in FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance were based on data between January 2008 and December 2016.[10] The 2019 guidance also includes information about how often this information would be updated. We assessed these findings against federal internal control standards on using quality information to achieve agencies’ objectives.[11]

We interviewed officials in FEMA headquarters and all 10 FEMA regions to collect information on the ways in which FEMA supports states when applying for an IA declaration. We also obtained guidance and training materials from regions to understand the types of information FEMA uses to support states when applying for an IA declaration. We interviewed emergency management officials from 11 states (Arkansas, California, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New York, Pennsylvania, Oregon, South Dakota, and West Virginia) to discuss their experiences in applying for IA declarations. While not generalizable to all states’ experiences nationwide, these perspectives provided a wide range of experiences across large and small states and across geographic regions.

To examine how FEMA uses information on vulnerable populations when making IA declaration requests, we reviewed documents on the agency’s efforts to address the needs of vulnerable populations, including its 2022-2026 Strategic Plan and Equity Action Plan. We interviewed officials in FEMA headquarters and all 10 regions to collect information on how FEMA incorporates information on vulnerable populations in the IA declaration process. To corroborate information in these interviews and to examine how FEMA considers this information in the IA declaration process, we reviewed Preliminary Damage Reports for the 126 disasters requesting IA that occurred during fiscal years 2020 through 2023. We also reviewed 36 Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendations representing (1) the three most recent disasters that occurred in each FEMA region at the time of our review and (2) any disasters discussed in our regional interviews. To collect information about challenges faced by rural communities, we interviewed FEMA’s Small State and Rural Advocate and emergency management officials from 11 states, as described above.

In addition, we reviewed relevant laws and FEMA policies, procedures, and guidance related to the disaster declaration process and the IA declaration factors. We also interviewed subject matter experts to collect various perspectives on the disaster declaration process, including the role of states, the impact of disasters on vulnerable populations, and how Individual Assistance affects vulnerable populations.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusion based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Background

FEMA’s Role and Types of Disaster

Assistance

FEMA’s Role and Types of Disaster

Assistance

The Stafford Act establishes the programs and processes through which the federal government provides disaster assistance to state, local, and tribal governments and individuals.[12] FEMA has primary responsibility for coordinating the federal disaster response and recovery, which typically consists of providing grants to assist state and tribal governments, as well as individuals, to alleviate the damage resulting from such disasters. When a major disaster is declared, the declaration may authorize IA, Public Assistance, and/or the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.[13] For instance, some declarations may authorize IA and others Public Assistance, and some may authorize some but not all programs under IA. The Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, on the other hand, has historically been approved for all major disaster declarations if the affected area has a FEMA-approved Hazard Mitigation plan.

Disaster Declaration Process

Disaster Declaration Process

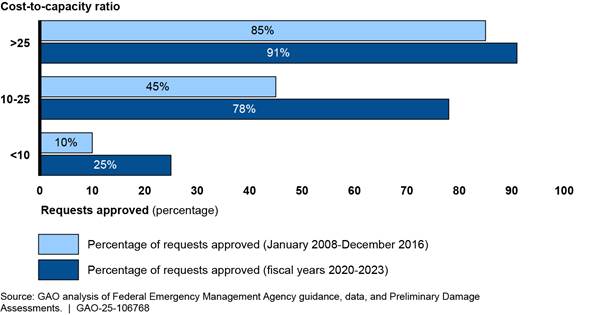

The Stafford Act also prescribes the process for states’ governors or tribal chief executives to request federal assistance.[14] As part of the request to the President, a governor or tribal chief executive must affirm that the state or tribal government has implemented its emergency plan and that the situation is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the state. To determine whether federal assistance is needed, state and tribal governments, along with local partners, and FEMA must first conduct a Preliminary Damage Assessment. The Preliminary Damage Assessment helps FEMA understand the magnitude of damage and the disaster’s impact. Information from this assessment is included in the disaster declaration request to demonstrate that the state or tribal government is overwhelmed and needs federal assistance.

The review of a declaration request occurs at two different FEMA levels: region and headquarters. Once a FEMA region reviews the state’s request, the Regional Administrator submits a recommendation to FEMA headquarters. The recommendation—known as the Regional Administrator’s Validation and Recommendation—outlines the reasoning and recommendation from the Regional Administrator on whether to approve or deny a major disaster declaration request. We refer to this as the Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendation. When reviewing declaration requests, FEMA headquarters offices make a recommendation to concur, partially concur, or non-concur with the region’s recommendation to approve or deny the governor or tribal chief executive’s request.[15] FEMA headquarters then sends a recommendation to the White House. Figure 1 shows the process for a major disaster declaration.

Declaration Approvals, Denials,

and Appeals

Declaration Approvals, Denials,

and Appeals

Many possible combinations of responses to declaration requests can result from states requesting assistance for multiple affected geographic areas such as counties, as well as states and tribal governments requesting Public Assistance and/or IA in their declaration request.[16] For example:

· IA approved for all counties. If a state requests a major disaster declaration with IA for 10 counties, the President could approve IA for all 10 counties. In this case, IA would be approved for all counties.

· IA approved for some counties. A state may request a major disaster declaration with IA for 10 counties, but the President may only approve assistance for six of the 10 counties. In such a case, IA would be approved for some counties, and FEMA would notify the Governor of the non-designation via a letter that indicates which counties or other geographic areas were not approved.

· Declaration approved, but all IA denied. The President may approve the major disaster declaration request only for FEMA’s Public Assistance and deny the request for IA.[17] In this case, although the state would receive a major disaster declaration, FEMA IA would not be authorized or provided. FEMA would notify the Governor of the non-designation via a letter that indicates which programs were not authorized.

· Entire declaration request denied. The President could deny the entire declaration request and no federal assistance under the Stafford Act would be approved. FEMA would send a denial letter to the state.

The governor of a state or the tribal chief executive has the right to a one-time appeal of a denied declaration request or non-designation of requested geographic areas or programs.[18] The governor or tribal chief executive must submit the appeal within 30 days of the date of the letter and include additional information justifying the need for federal assistance. According to FEMA officials, FEMA regions can provide states with technical assistance regarding the information for inclusion in the appeal. The appeal of a denial follows the same process as the original declaration request, with the FEMA region making a recommendation to FEMA headquarters, which makes a recommendation to the President. According to FEMA guidance, for an appeal of a non-designation, the President makes the determination for program non-designations and FEMA headquarters makes determinations for geographic area non-designations.[19]

Changes to the Individual

Assistance Declaration Factors

Changes to the Individual

Assistance Declaration Factors

In March 2019, FEMA issued a final rule revising the factors that FEMA considers when evaluating a request for a major disaster declaration with IA.[20] These revised factors were intended to provide clarity on the IA declaration factors that FEMA considers when determining whether a declaration authorizing IA is warranted, which may reduce delays in the declaration process. The revised factors also included a new factor on fiscal capacity to provide additional information and context on states’ ability to respond to disasters. Table 1 describes the revised factors and the previously used factors.

|

Factors prior to 2019 |

Factors as revised in 2019 |

|

1. Average amount of Individual Assistance by state—the average amount of Individual Assistance by state size |

1. State fiscal capacity and resource availability—the availability of state resources, and where appropriate, any extraordinary circumstances that contributed to the absence of sufficient resources. |

|

2. Insurance coverage—the level of insurance coverage among those affected |

2. Uninsured home and personal property losses—includes the estimated cost of assistance, among other things. |

|

3. Special populations—the impact of the disaster on special populations, such as low-income populations, older individuals, or unemployed individuals. |

3. Disaster-impacted population profile—the demographics of a disaster impacted population that may identify additional needs that require a more robust community response and delay a community’s ability to recover from a disaster. |

|

4. Concentration of damages—whether damages are highly concentrated, which generally indicates a greater need for federal assistance than widespread and scattered damages throughout a state. |

4. Impact to community infrastructure—disruption to, or increased demand for, life-saving, life-sustaining, and essential community services, or to utilities or transportation infrastructure that can adversely impact a population’s ability to safely and securely reside within the impacted community. |

|

5. Trauma—conditions that might cause trauma, including large numbers of injuries and deaths, large-scale disruption of normal community functions, and emergency needs such as extended loss of power or water. |

5. Casualties—the number of missing, injured, and deceased individuals following a disaster. |

|

6. Voluntary agency assistance—the extent to which voluntary agencies and state or local programs can meet the needs of disaster survivors. |

6. Disaster-related unemployment—survivors who lost work or became unemployed due to a disaster and who do not qualify for standard unemployment insurance benefits. |

Source: GAO summary of federal law, FEMA guidance, and GAO’s prior work. | GAO 25-106768

Note: These IA declaration factors apply only to state major disaster declaration requests that include IA. FEMA is implementing guidance for tribal declarations on a separate, distinct track. FEMA began piloting guidance for tribal declarations in 2017 and issued new guidance in December 2024. Our summary of IA declaration factors is based on 44 C.F.R. 206.48(b); GAO, Federal Disaster Assistance: Individual Assistance Requests Often Granted, but FEMA Could Better Document Factors Considered, GAO‑18‑366 (Washington, D.C.: May 2018); FEMA, Individual Assistance Declarations Factors Guidance, (Washington, D.C.: June 2019).

|

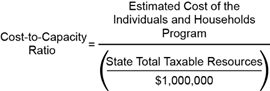

FEMA’s Cost-to-Capacity Ratio FEMA’s cost-to-capacity ratio is a gauge used to help determine whether to authorize the Individuals and Households Program, which is one of the primary programs that may be authorized under an Individual Assistance major disaster declaration designation. The cost-to-capacity ratio is calculated by dividing the estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program by the state’s total taxable resources (in millions):

For example, if a state estimates $2,000,000 in Individual and Household Program costs and the state’s total taxable resources is $30,000,000,000, the resulting cost-to-capacity ratio would be 66.7.

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency, Individual Assistance Declarations Factors Guidance (Washington, D.C.: June 2019). | GAO‑25‑106768 |

FEMA published guidance describing these factors in June 2019 and stated that this guidance was intended to provide additional clarity regarding the circumstances, especially the severity and magnitude of the disaster relative to state capacity, under which FEMA is likely to recommend a declaration authorizing IA.[21] This guidance includes an explanation of how FEMA uses elements from the first two IA declaration factors mentioned in table 1 above to calculate the Individuals and Households Program Cost to Capacity ratio (cost-to-capacity ratio). FEMA uses the ratio as a gauge to help determine whether to authorize the Individuals and Households Program, which is one of the primary programs that may be authorized under an IA major disaster declaration designation.[22] The cost-to-capacity ratio uses the estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program to determine “cost” and a state’s total taxable resources to determine “capacity,” which, together, help determine whether the state has the capacity to meet the housing and other needs of the affected communities. The higher the estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program and the lower the state’s total taxable resources, the less likely the state has the capacity to meet the needs of the affected communities, and the more likely a request for federal assistance will be granted. Put differently, a higher cost-to-capacity ratio is more likely to be approved for the Individuals and Households Program than a lower cost-to-capacity ratio.

FEMA’s Small State and Rural

Advocate

FEMA’s Small State and Rural

Advocate

Section 326 of the Stafford Act, as amended, establishes the role of a Small State and Rural Advocate within FEMA.[23] According to FEMA’s website, the Small State and Rural Advocate works for the fair treatment of small states and rural communities by

1. ensuring these communities are represented in emergency management processes and programs,

2. counseling states on the emergency and major disaster declaration processes to ensure that the needs of rural communities are being addressed, and

3. assisting states in the collection and presentation of materials to demonstrate severe localized impacts for a specific incident as part of a request for a disaster declaration.[24]

FEMA appointed the current Small State and Rural Advocate in November 2023. This position advocates for 14 states, the District of Columbia, and several territories—all of which have populations of less than 2 million.

The Percentage of IA Requests That Were Approved Increased

in Fiscal Years 2015 through 2023

The Percentage of IA Requests That Were Approved Increased

in Fiscal Years 2015 through 2023

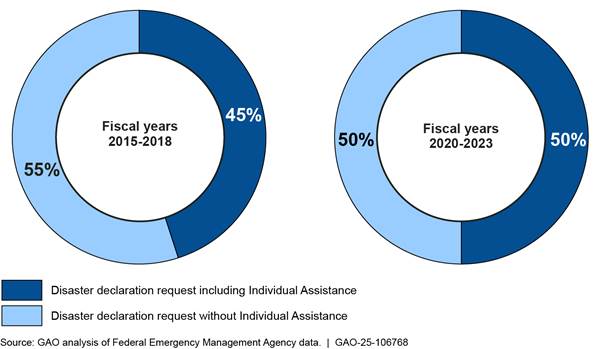

The percentage of requests for major disaster declarations that included IA increased in fiscal years 2015 through 2023.[25] Of the major disaster declaration requests from fiscal years 2020 through 2023, 50 percent (126 of 253) included IA. This represents a 5-percentage point increase from fiscal years 2015 through 2018, during which 45 percent of requests (102 of 229) included IA, as shown in figure 2.

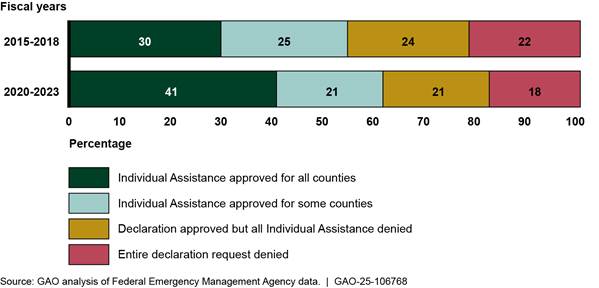

Among disaster declaration requests that included IA, there was an increase in the percentage of requests for which IA was approved. During fiscal years 2015 through 2018, 55 percent of requests (56 of 102) that included IA were approved for IA for at least some counties, compared to 62 percent of requests (78 of 126) that requested IA in fiscal years 2020 through 2023. More specifically, there was an increase in the portion of requests for which IA was authorized for all counties (41 percent versus 30 percent). The percentage of requests for which IA was denied and the percentage of declarations where the entire request was denied both decreased, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Outcomes of Major Disaster Declaration Requests With Individual Assistance (IA) by Percentage, Fiscal Years 2015–2018 and 2020–2023

Note: There were 102 major disaster declaration requests with IA from fiscal years 2015 through 2018, and 126 major disaster declaration requests with IA from fiscal years 2020 through 2023. The revised IA factors took effect on June 1, 2019. To compare the trends before and after the revised IA factors took effect, we excluded data from Fiscal Year 2019. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

· IA approved for all counties. As previously stated, the percentage of requests where IA was approved for all counties increased in the period after FEMA revised the IA declaration factors. From fiscal years 2015 through 2018, 30 percent of IA declaration requests (31 of 102) were approved for all counties. This increased to 41 percent (51 of 126) in fiscal years 2020 through 2023.

The increase in IA requests approved for all counties occurred among all disaster types, including hurricanes and floods. For example, the number of disaster declaration requests for hurricanes where IA was approved for all counties increased from six in fiscal years 2015 through 2018 to 15 in fiscal years 2020 through 2023. Among IA declaration requests for floods, the number of requests where IA was approved for all counties increased from 11 declarations in fiscal years 2015 through 2018 to 13 declarations in fiscal years 2020 through 2023. One factor considered in IA requests is the level of uninsured or underinsured homes. According to FEMA’s 2019 guidance, the level of insurance coverage is needed to determine whether IA is necessary. According to a FEMA official, flood insurance rates are lower than insurance rates for other disaster types. If a flood damages homes in an area where many homeowners do not have flood insurance, then IA may be needed.

· IA approved for some counties. The percentage of requests where IA was approved for some counties decreased since FEMA revised the IA declaration factors. From fiscal years 2015 through 2018, 25 percent (25 of 102) of IA declaration requests were approved for some counties. This decreased to 21 percent (27 of 126) in fiscal years 2020 through 2023.

Not all counties in an IA declaration request may be approved for IA because a storm’s path may change and result in less damage than anticipated. For example, in August 2023, one state requested IA for 27 counties for Hurricane Idalia. Of these 27 counties, FEMA approved 18. In another state affected by Hurricane Idalia, one county requested IA, but its request was denied. According to officials in one FEMA region, this county may have been part of the initial declaration request due to the predicted path of the storm, but the storm shifted, and the Preliminary Damage Assessment showed that there was not as much damage as initially anticipated.

In another FEMA region, officials said only some counties were approved for IA because the damage was not in as many areas as originally thought. Another reason that only some counties in a declaration request may be approved for IA is because certain types of disasters may make it difficult to determine the extent of damage to homes. For example, in one FEMA region, not all counties were approved for IA following an ice storm.

· Declaration approved but all IA denied. The percentage of requests where the disaster declaration was approved, but IA was denied, decreased in the period since FEMA revised the IA declaration factors. From fiscal years 2015 through 2018, 24 percent (24 of 102) of IA declaration requests had IA denied, but the rest of the declaration request was approved. This decreased to 21 percent (26 of 126) in fiscal years 2020 through 2023.

One reason IA may be denied is because residents affected by a disaster are well-insured; IA benefits cannot duplicate insurance proceeds. In addition, because FEMA provides assistance for primary residences, IA could be denied if much of a disaster’s damage occurs to second or vacation homes. Officials in one FEMA region said that IA was denied for a disaster because the damage was mostly to resorts and second or vacation homes.

· Entire declaration request denied. The percentage of requests where the entire declaration request was denied also decreased between these two time periods. From fiscal years 2015 through 2018, 22 percent of (22 of 102) all requests with IA were completely denied. This decreased to 18 percent (22 of 126) in fiscal years 2020 through 2023.

According to FEMA officials, the most common reason for a disaster declaration request to be denied is because the situation is not as severe as to be beyond the state’s capabilities. That is, the state has the capacity to respond to the event and help affected areas recover from it.

According to FEMA officials, the increased percentage of declarations with IA after the factors changed in 2019 was due to the severity of disasters, not the revised factors themselves. This trend of increasing IA disaster declarations reflects the overall trend of increasing disaster declarations. According to the Congressional Research Service, disasters in the U.S. have become more frequent and severe, and the average number of disaster declarations has increased from the first decade after the enactment of the Stafford Act in 1988 to the most recent 10 fiscal years. In addition, more counties have experienced a greater number of disaster declarations in the past 10 years than in the first decade after FEMA was established in 1979.[26]

FEMA Helps States Understand the IA Declaration Process

but Uses Outdated Information to Convey the Likelihood of Approval

FEMA Helps States Understand the IA Declaration Process

but Uses Outdated Information to Convey the Likelihood of Approval

FEMA Resources Help States

Understand the IA Declaration Process

FEMA Resources Help States

Understand the IA Declaration Process

FEMA regions support states as they navigate the IA declaration process through a range of resources.[27] These include training, technical assistance, guidance, and supporting state and territorial emergency management offices through FEMA Integration Teams, as described below.

· Training. Officials from all 10 FEMA regions we spoke to said they offer trainings to states on topics such as the declaration process, requesting IA, and how to perform damage assessments. These trainings may be offered regularly or when a state or territory has new emergency management staff or leadership, according to officials in three FEMA regions. The state may also request trainings as needed. For example, four FEMA regions shared their presentations on IA, which they had tailored for states in their regions. Officials in one FEMA region said they offer a training or webinar every two weeks in addition to an annual 12-part webinar and state-requested trainings.

· Technical assistance. FEMA regions also provide technical assistance to states during the declaration request process. This includes answering questions on what information is needed, where to find forms, and advice on how to assess the likelihood of IA approval, according to officials in four FEMA regions. For example, states may share the draft declaration request with the FEMA region and receive feedback on where more or clearer information is warranted, according to officials in one FEMA region.

· Guidance. FEMA regions provide guidance documents for states on topics such as how to complete a request for a major disaster declaration, how to conduct expedited damage assessments, and expected timelines.

· FEMA Integration Teams. Officials in all 10 FEMA regions that we interviewed stated that they provide resources and support to states through FEMA Integration Teams, which are FEMA staff embedded within state emergency management offices.[28] Officials from six FEMA regions said that Integration Team members serve as liaisons between FEMA and the states in various aspects of responding to disasters. For example, officials from these six FEMA regions said that Integration Team members provide situational awareness during a disaster response. Officials in one region said they have an Integration Team member who serves as an IA subject matter expert during Preliminary Damage Assessments.

Although FEMA regions provide a range of support to states, state officials told us that FEMA does not share why IA declaration requests were not approved in its denial letters. Specifically, emergency management officials from four states told us that denial letters are vague and do not offer any specific explanations for why the declaration request was not approved. One state official said that the denial letter received only said they did not meet the IA factors and was unsure why the requests were not approved. FEMA headquarters officials said they use standard denial letter templates that do not offer reasons behind the denial. Using these templates ensures consistency across all states and FEMA regions when communicating necessary information during the declaration process, according to FEMA headquarters officials. Further, if a state appeals a denial, FEMA regions can provide the state with technical assistance regarding the information to include in the appeal.

FEMA Has Not Updated Its Guidance

to Incorporate Recent Data on the Cost-to-Capacity Ratio

FEMA Has Not Updated Its Guidance

to Incorporate Recent Data on the Cost-to-Capacity Ratio

According to FEMA, the cost-to-capacity ratio is an important tool for estimating the likelihood of approval for IA. As previously stated, this ratio is calculated by dividing the estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program, one of the primary programs that may be authorized under an IA major disaster declaration designation, by the state’s total taxable resources (in millions). The higher the estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program and the lower the state’s total taxable resources, the more likely a request will be granted. That is, a higher cost-to-capacity ratio is more likely to be approved for IA.

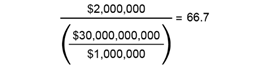

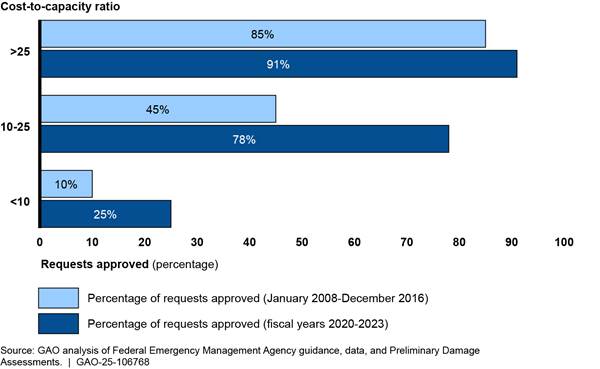

FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance includes a table of ratios and the percentage of IA requests granted for several ranges of ratios, as shown in table 2. According to this guidance, this table is intended to aid states in their decision-making when making a request. The table illustrates that IA requests with higher cost-to-capacity ratios (i.e., higher estimated cost of the Individuals and Households Program and lower state total taxable revenue) are more likely to be approved than IA requests with lower cost-to-capacity ratios. For example, table 2 shows that if the cost-to-capacity ratio is above 25, IA is more likely to be granted (i.e., 85 percent of IA requests) compared to 10 percent of IA requests granted with a cost-to-capacity ratio below 10.

Table 2: Percentage of Individual Assistance Requests Approved by Cost-to-Capacity Ratio, January 2008–December 2016

|

Cost-to-capacity ratio |

Percentage of

requests approved |

|

>25 |

85% |

|

10–25 |

45% |

|

<10 |

10% |

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency data. | GAO‑25‑106768

Note: Data are from Federal Emergency Management Agency, Individual Assistance Declarations Factors Guidance (Washington, D.C.: June 2019).

This table is important because states and FEMA use it to assess the likelihood of IA approval, according to FEMA headquarters officials. It is also important because FEMA regions use this table to help states understand their chances of being approved for IA, including in training materials about the IA declaration process.

However, FEMA has not updated this table and percentage of IA requests approved to reflect data from more recent disasters, including those that occurred after the 2019 revision of the IA declaration factors. Rather, this table is based on data from January 2008 through December 2016. According to FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance, FEMA tracks this information and will provide annual updates to this information on its website, but this information has not been updated since this guidance was issued. FEMA headquarters officials said that they have not updated this information and that FEMA’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic played a role in the delay. As of April 2025, FEMA is not updating the IA declaration factors guidance at this time, according to FEMA headquarters officials.

Based on our analysis, IA approval rates differ once the underlying data are updated. Using available data from fiscal years 2020 through 2023, we found that approval rates were higher for each cost-to-capacity ratio category compared to the approval rates in FEMA’s current guidance. Specifically, FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance indicates 45 percent of disasters with a cost-to-capacity ratio between 10 and 25 were approved for IA, based on disaster declaration requests between January 2008 and December 2016. However, as shown in figure 4, 78 percent of requests within the same range of cost-to-capacity ratios were approved when using data from fiscal years 2020 through 2023. Similarly, IA requests with a cost-to-capacity ratio less than 10 resulted in 25 percent of the requests being approved compared to 10 percent of IA requests being approved in the table using data from 2008 through 2016, as shown in figure 4. Officials in three states said that their states’ higher total taxable resources make it challenging for their states to be approved for IA. This is because a higher total taxable resource would result in a lower cost-to-capacity ratio. However, more recent trends in IA declarations suggest that each category of cost-to-capacity ratio may have a greater chance of being approved than the guidance suggests.

Figure 4: Percentage of Individual Assistance Requests Approved, by Cost-to-Capacity Ratios and Time Periods

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government calls for agencies to use quality information to help ensure they achieve their objectives.[29] Quality information should be accessible, complete, and accurate to help management make informed decisions and evaluate performance in achieving key objectives and address risks. The cost-to-capacity ratio is instrumental in the IA declaration process to help states and FEMA assess a state’s request for IA. In particular, the cost-to-capacity ratio acts as a gauge for whether IA will be approved and is an important factor for helping states in their decision-making. If IA approval seems unlikely, states may decide to not devote resources toward requesting IA. For example, officials from two states said that they assume their request for IA will not be approved, so they do not request it. By regularly updating the cost-to-capacity table in its guidance and website, FEMA could provide states with a more accurate understanding of their likelihood of approval. This could better inform states’ decisions on whether to request IA, especially at lower cost-to-capacity ratios, and help communities receive needed assistance after a disaster.

FEMA Uses Information on Vulnerable Populations When

Making IA Recommendations and Is Taking Steps to Better Support Small States

and Rural Areas

FEMA Uses Information on Vulnerable Populations When

Making IA Recommendations and Is Taking Steps to Better Support Small States

and Rural Areas

FEMA’s IA Declaration Process

Considers Information on Vulnerable Populations

FEMA’s IA Declaration Process

Considers Information on Vulnerable Populations

FEMA considers information on vulnerable populations when developing recommendations for major disaster declarations using the information states are required to detail on each IA declaration factor. Factors such as uninsured home and personal property losses, the disaster-impacted population profile, impact to community infrastructure, and disaster-related unemployment inherently address vulnerabilities and needs of populations disproportionately impacted by disasters, according to FEMA headquarters officials. FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance states that the demographics of a disaster-impacted population may identify additional needs that require a more robust response and delay a community’s ability to recover from a disaster. The guidance also notes that states should elaborate on recovery challenges experienced by the impacted population due to the demographics of the areas. These demographic data include the percentage of the population in poverty, receiving government assistance, or having a disability. See text box for additional information.

|

FEMA’s Third Individual Assistance Declaration Factor: Disaster Impacted Population Profile Consistent with its regulation, FEMA will consider demographic data points related to the disaster impacted community. FEMA will consider the following U.S. Census and other federal agency demographic data points in making a recommendation for Individual Assistance under a major disaster declaration: (1) the percentage of the population in poverty; (2) the percentage of the population already receiving government assistance, such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits; (3) the pre-disaster unemployment rate; (4) the percentage of the population that is 65 years or older; (5) the percentage of the population 18 years or younger; (6) the percentage of the population with a disability; and (7) the percentage of the population who speak a language other than English and speak English less than “very well.” |

Source: 44 C.F.R. 206.48(b)(3); Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) guidance. | GAO‑25‑106768

In addition, uninsured and underinsured households are more vulnerable after a disaster. According to the Congressional Budget Office, low- and moderate-income households are more likely to be uninsured or underinsured than high-income households, leaving them more likely to face financial losses after a natural disaster.[30] FEMA’s 2019 IA guidance states that the level of insurance coverage in an affected area is necessary to determine whether the Individuals and Households Program, one of the primary programs that may be authorized under an IA major disaster declaration designation, is needed. Insurance coverage may differ by disaster type, and that can impact the estimated cost of assistance, according to FEMA headquarters officials.

We found that FEMA incorporated data on vulnerable populations in two parts of the declaration process: (1) Preliminary Damage Assessments and (2) FEMA’s Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendations.

· Preliminary Damage Assessments. Data such as the percentage of the population in poverty were reported in 92 percent (116 of 126) of the Preliminary Damage Assessments we reviewed. The percentage receiving government assistance or who have a disability were reported in 88 percent (111 of 126) and 87 percent (109 of 126) of the Preliminary Damage Assessments we reviewed, respectively. For example, a Preliminary Damage Assessment from Delaware to assist with the remnants of Hurricane Ida reported that 11 percent of households were in poverty and 11 percent of the population received government assistance such as Supplemental Security Income and benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. A Preliminary Damage Assessment from Kentucky for severe storms and other events reported that 21 percent of households were in poverty and 22 percent of the population had a disability.

· Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendations. These data were also reported in FEMA’s Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendations sent to FEMA headquarters. All but two of the 36 FEMA Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendations we reviewed included the percentage of the affected population who are in poverty, receive government assistance—such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or have a disability, among other demographic variables.

A Preliminary Damage Assessment or Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendation may include less information when a state makes an expedited request for a major disaster declaration.[31] A state may also decide to request IA after submitting the initial disaster declaration request, so the Preliminary Damage Assessment or Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendation may not include the IA declaration factors if the state did not initially request IA.

In addition to these demographic data, FEMA regional offices used additional data tools to understand the population of a disaster-affected area—the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) and the Climate and Economic Justice screening tool.[32] We found that 22 of the 36 Regional Disaster Declaration Recommendations from July 2019 through December 2023 that we reviewed included information about the affected area’s level of social vulnerability, and officials in six of the 10 FEMA regional offices said they considered an area’s SVI score when reviewing a state’s request for a disaster declaration with IA. Officials in one FEMA regional office said that in addition to the SVI, they also used the Climate and Economic Justice screening tool to consider special populations affected by a disaster. FEMA regional officials said that these data tools can be helpful especially when the cost-to-capacity ratio does not clearly indicate whether FEMA should recommend the President approve or deny a request for IA.

FEMA’s Small State and Rural

Advocate May Help Address Challenges in the Declaration Process Faced by

Smaller Communities

FEMA’s Small State and Rural

Advocate May Help Address Challenges in the Declaration Process Faced by

Smaller Communities

The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006 established the Small State and Rural Advocate within FEMA to assist small population states in preparing requests for declaration requests and participating in the declaration process to ensure that the needs of rural communities are being addressed.[33] The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 added an additional responsibility, which is to assist states in the collection and presentation of material in a declaration request to demonstrate severe localized impacts within a state for a specific incident.[34] More recently, FEMA’s 2022-2026 Strategic Plan includes persons living in rural areas as a vulnerable community.

Rural areas affected by disasters, as shown in figure 5, face unique challenges in their response and recovery. According to one FEMA official, rural areas’ sparse populations, fewer or limited local resources, and great distances to critical infrastructure can underscore the need for federal assistance. Rural communities’ fewer resources may also create challenges in collecting the information needed for a disaster declaration request, according to FEMA headquarters and regional officials, and state emergency management officials.

Emergency management officials in a small state we spoke with noted that they had a small emergency management office, and the level of documentation required to apply for an IA declaration is more challenging for them and rural communities. In particular, damage assessments may be especially challenging for small rural areas. According to one FEMA official, rural areas often have less robust infrastructure, which makes it more challenging to recover from repeated disasters, all of which can impede thorough damage assessments needed to make a declaration request.

In November 2023, FEMA appointed a new Small State and Rural Advocate. Officials in five of 10 FEMA regions said they were aware of the Small State and Rural Advocate, and officials in the other five regions said they were unfamiliar with this position when we interviewed them in February through May of 2024. Officials in two FEMA regions said that this position was vacant for many years, and that they had not yet interacted with the Small State and Rural Advocate as the position was only recently filled. According to a FEMA official, the duties of the Small State and Rural Advocate were first added to existing positions at FEMA before becoming a separate full-time position in 2023.

The Small State and Rural Advocate, who was appointed in 2023, reported having engaged in listening sessions with state, local, tribal, and territorial representatives across four FEMA regions and having assisted with Preliminary Damage Assessments in one region to better understand the declaration process for small states and rural communities. In particular, the advocate has worked with FEMA regional, state, and local officials to collect information from a rural area for the Preliminary Damage Assessment needed for the state to submit a disaster declaration request. This advocate also played a key role in responding to Hurricane Helene in 2024, working closely with FEMA’s Federal Coordinating Officer, other federal agencies, and state agencies, including a state emergency management office.

According to a FEMA official, when not helping rural areas respond to a disaster, the Small State and Rural Advocate is responsible for (1) building relationships with FEMA regions, state and local officials, community leaders, and stakeholders; (2) conducting listening sessions with stakeholders from small states and rural areas to understand their unique challenges and needs; and (3) providing technical assistance to FEMA regions, small states, and rural areas on disaster management practices and strategies. In addition, this official is responsible for supporting efforts to strengthen the capacity of local agencies and organizations in disaster response and recovery, as well as advocating for the interests and priorities of small states and rural areas within FEMA and other relevant agencies. As of December 2024, there are no plans for FEMA to add staff to support the Small State and Rural Advocate.

As disasters continue to affect smaller communities, the Small State and Rural Advocate may help to address challenges related to disaster declarations. Since this position and these efforts are new, we will continue monitoring FEMA’s efforts to support small states and rural communities in future work.

Conclusions

Conclusions

In 2023 alone, the President declared 22 major disasters with Individual Assistance, and FEMA spent over $1.5 billion on Individual Assistance programs. In 2024, Hurricanes Helene and Milton occurred within 2 weeks of one another and resulted in over 200 deaths. As disasters continue to occur more frequently and with greater intensity, more individuals and households will require federal assistance to help recover from disasters. FEMA’s IA declaration factors are an important part of evaluating a state’s request for federal assistance. FEMA’s guidance for the IA declaration factors has not been updated since 2019 and may understate the likelihood of being approved for IA. Regularly updating its cost-to-capacity ratio table with more recent data could help states have a more accurate understanding of their chances of IA approval and could inform states’ decisions on whether to apply for IA. This ultimately could help more individuals and households receive the assistance needed to recover from disasters.

Recommendation for Executive Action

Recommendation for Executive Action

The FEMA Administrator should take steps to ensure that FEMA’s guidance for requesting Individual Assistance declarations reflects updated data on the number of IA requests approved, and that this information, including the percentage of approved declarations and cost-to-capacity ratio ranges, is updated regularly in its guidance and on its website. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and FEMA for comment. DHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix I. DHS concurred with the recommendation and provided steps it plans to address it, which should address the intent of our recommendation if implemented effectively. FEMA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of

this report to the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Acting FEMA

Administrator, and the appropriate congressional committees. In addition, the report

is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

We are sending copies of

this report to the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Acting FEMA

Administrator, and the appropriate congressional committees. In addition, the report

is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at curriec@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Chris Currie

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

GAO Contact

Chris

Currie, Director, curriec@gao.gov.

Chris

Currie, Director, curriec@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Joel Aldape (Assistant Director), Grace Cho (Analyst in Charge), Jennifer Alexander, Hiwotte Amare, Erika Cubilo, Elizabeth Dretsch, Eric Hauswirth, Tracey King, Kristiana Moore, and Kevin Reeves made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports

and Testimony

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports

and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste,

and Abuse in Federal Programs

To Report Fraud, Waste,

and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General

Inquiries

General

Inquiries

[1]42 U.S.C. § 5170. Throughout this report, and in accordance with the Stafford Act, “state” means any state of the United States, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. See 42 U.S.C. § 5122(4). As such, references in this report to states and state governors include territories and territorial governors.

[2]States and tribal governments may also request emergency declarations under the Stafford Act; however, IA is rarely approved as part of emergency declarations. See 42 U.S.C. § 5191.

[3]GAO, Disaster Assistance: Improving the Federal Approach, GAO‑25‑108216, (Washington, D.C.: March 25, 2025); FEMA, Daily Operations Briefing, (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2025).

[4]42 U.S.C. § 5151(a).

[5]GAO, Federal Disaster Assistance: Individual Assistance Requests Often Granted, but FEMA Could Better Document Factors Considered, GAO‑18‑366 (Washington, D.C.: May 31, 2018).

[6]84 Fed. Reg. 10,632 (Mar. 21, 2019) (codified as amended at 44 C.F.R. § 206.48(b)). We excluded emergency declarations from our analyses, as emergency declarations do not require an evaluation of the IA declaration factors.

[7]44 C.F.R. § 206.48(b).

[8]Pub. L. No. 117-263, § 5601(b), 136 Stat. 2395, 3403 (2022). We submitted preliminary observations of this review to the appropriate committees of Congress on December 22, 2023.

[9]We did not include tribal declarations because FEMA uses different factors when considering IA requests from tribal governments. FEMA updated its guidance for tribal disaster declarations on December 3, 2024. State requests can include tribal areas, and we included these in our review. We also did not include COVID-related disaster declarations in our review because the President declared a nationwide emergency for the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, these were authorized for all states and did not rely on the IA declaration factors.

[10]FEMA, Individual Assistance Declarations Factors Guidance (Washington, D.C.: June 2019).

[11]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[12]Pub. L. No. 93-288, 88 Stat. 143 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 5121 et seq.).

[13]Public Assistance aids state, local, territorial, and tribal governments, as well as certain private non-profit organizations, for emergency work and the repair or replacement of disaster-damaged facilities, such as roads, bridges, and utilities. The Hazard Mitigation Grant Program provides grants for state, local, territorial, and tribal governments for activities taken to prevent or reduce long-term risk to life and property from natural hazards.

[14]42 U.S.C. § 5170.

[15]According to FEMA officials, partially concurring with a FEMA region’s recommendation occurs when a FEMA headquarters’ recommendation to the President includes or excludes some geographic areas and/or programs in the region’s recommendation.

[16]Throughout this report, “counties” also refer to parishes, municipalities, or similar geographic areas.

[17]Public Assistance is FEMA’s largest grant program providing funds to assist communities responding to and recovering from major disasters or emergencies declared by the President. The program provides funding for emergency assistance to save lives and protect property and assists with funding for permanently restoring community infrastructure affected by a federally declared incident.

[18]44 C.F.R. § 206.46.

[19]FEMA, Presidential Disaster Declaration Process Guide (Washington, D.C.: March 2023).

[20]84 Fed. Reg. 10,632 (Mar. 21, 2019) (codified as amended at 44 C.F.R. § 206.48(b)).

[21]FEMA, Individual Assistance Declarations Factors Guidance (Washington, D.C.: June 2019).

[22]Other IA programs that may be approved when IA is designated are the Crisis Counseling and Training Program, Disaster Case Management Program, Disaster Legal Services, and Disaster Unemployment Assistance.

[23]The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 gave the Small State and Rural Advocate responsibility to assist states in the collection and presentation of material in the major disaster or emergency declaration request relevant to demonstrate severe localized impacts within the state for a specific incident, including, (1) the per capita personal income by local area, (2) the disaster impacted population profile, and (3) the impact to community infrastructure. 42 U.S.C. § 5165d(c)(3).

[24]“Small State and Rural Advocate,” FEMA, accessed on February 11, 2025, https://www.fema.gov/about/organization/regions/small‑state‑rural‑advocate.

[25]Our analysis identified trends but was not intended to identify the cause of any trends in IA requests or declarations from the period before to the period after the IA factors were revised in June 2019. In order to examine trends before and after FEMA revised the IA declaration factors, we did not include fiscal year 2019 in our analysis.

[26]Congressional Research Service, FEMA: Increased Demand and Capacity Strains, (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 2, 2025).

[27]We did not include tribal declarations in our review as FEMA uses different factors when considering IA requests from tribal governments.

[28]The FEMA Integration Teams were established in July 2017 with the goal of embedding FEMA staff with state and territorial partners, and to work alongside tribal partners. FEMA Integration Teams provide technical assistance and coordination to state, tribal, and territorial emergency management agencies in areas such as planning, logistics, recovery, and grants management.

[30]Congressional Budget Office, Climate Change, Disaster Risk, and Homeowner’s Insurance (Washington, D.C.: August 2024).

[31]An expedited request for a major disaster declaration may be submitted by a state for a disaster of unusual severity and magnitude when field damage assessments are not necessary to determine the need for federal assistance. In such a case, the governor may send an abbreviated written request, and FEMA may waive the requirement for a Preliminary Damage Assessment. 44 C.F.R. §§ 206.33(d), .36(d).

[32]The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) is a place-based index, database, and mapping application designed to identify and quantify communities experiencing social vulnerability. Social vulnerability refers to the demographic and socioeconomic factors, such as poverty and lack of access to transportation, that adversely affect communities that encounter hazards and other community-level stressors. These stressors can include natural or human-caused disasters. An area’s SVI is presented as a score ranging from zero to one, where one indicates a high level of social vulnerability. The Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool is an interactive map and uses datasets that are indicators of challenges in eight categories: climate change, energy, health, housing, legacy pollution, transportation, water and wastewater, and workforce development. The tool uses this information to identify communities that are experiencing burdens in these areas. On January 20, 2025, Executive Order 14008, which established the Justice40 Initiative and required the Council on Environmental Quality to create this tool, was revoked by Executive Order 14148. See 90 Fed. Reg. 8237 (Jan. 28, 2025). As of March 2025, the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool is no longer available on the White House website.

[33]42 U.S.C. § 5165d.

[34]Id. § 5165d(c)(3).