BANK SUPERVISION

Federal Reserve and FDIC Should Address Weaknesses in Their Process for Escalating Supervisory Concerns

Report to the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate

November 2024

GAO-25-106771

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106771. For more information, contact Michael E. Clements, (202) 512-8678, clementsm@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO-25-106771, a report to the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Community Affairs, U.S. Senate

November 2024

BANK SUPERVISION

Federal Reserve and FDIC Should Address Weaknesses in Their Process for Escalating Supervisory Concerns

Why GAO Did This Study

Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank were closed in March 2023, and FDIC was named as receiver. The failures raised questions about bank supervision, including whether the banking regulators are adequately escalating supervisory concerns to ensure that banks take prompt action.

As part of a series of reports related to these bank failures, GAO was asked to examine the regulators’ supervisory practices. Among other objectives, this report examines the processes and policies for escalating supervisory concerns at the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC.

GAO analyzed data on the regulators’ supervisory concerns opened from 2018 through 2022 and examination documents for a nongeneralizable sample of 60 institutions representing different asset levels and regions. GAO compared regulators’ communications of supervisory concerns against their policies and procedures. GAO also reviewed regulators’ guidance and interviewed 109 federal bank examiners and seven subject-matter experts.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to the Federal Reserve and three to FDIC to strengthen their processes for escalating supervisory concerns. Federal Reserve neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendations. FDIC generally agreed with two of the recommendations but disagreed with a recommendation that it require rotations for large bank case managers. GAO maintains that the recommendation is valid, as discussed in this report.

What GAO Found

GAO identified weaknesses at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System related to escalation of supervisory concerns.

Corporate governance and risk management. The Federal Reserve’s lack of a regulation or enforceable guidelines under section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act on corporate governance and risk management issues may have contributed to delays in taking more forceful action against Silicon Valley Bank, which failed in March 2023. Such authority may assist the Federal Reserve in taking early regulatory actions against unsafe banking practices before they compromise a bank’s capital.

Early remediation. The Federal Reserve has not finalized a rule required by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (with an effective date of January 2012). The rule was intended to promote earlier remediation of issues at financial institutions. Federal Reserve officials stated that other rules accomplish much of what the act intended but acknowledged that substantive items from the act remain unimplemented. By implementing the act’s requirements, the Federal Reserve could align its supervisory tools with congressional intent that it take early action before an institution’s financial condition deteriorates.

GAO also found weaknesses in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) escalation procedures.

Centralized tracking. The absence of a centralized system for tracking supervisory recommendations—that is, communications informing an institution of changes needed in operations or financial condition—limits FDIC’s ability to identify emerging risks across the banks it supervises.

“Vetting” meetings. Unlike other regulators, FDIC does not have a formalized process to ensure that large bank examination teams and relevant stakeholders are consulted before making changes or decisions, such as escalation decisions. Examiners from two selected banks cited concerns about managers altering conclusions without consulting the examiners or being unreceptive to divergent views. Procedures, such as vetting meetings, requiring managers to consult with large bank examiners and other stakeholders could ensure decisions are grounded in the evidence gathered during examinations.

Rotation requirements. Unlike the other regulators, FDIC does not require large bank case managers to rotate after a few years at one institution. Case managers play a key role in the examination process. GAO has previously reported that agencies can mitigate threats to independence by implementing policies that rotate staff in key decision-making roles, thereby reducing the impact of any one employee. Implementing rotation requirements could limit close relationships between FDIC large bank case managers and bank management, helping ensure large bank case managers maintain their supervisory independence.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has procedures for escalating supervisory concerns to enforcement actions, and GAO found that it generally adheres to these procedures. These procedures include collaborative decision-making processes and documentation of divergent views between examiners and supervisors.

Abbreviations

|

CAMELS |

capital adequacy, asset

quality, management, |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 19, 2024

Congressional Requesters

The 2023 failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank created an estimated net loss of $3.2 billion to the Deposit Insurance Fund.[1] We previously reported that risky business strategies and weak liquidity and risk management practices contributed to these bank failures.[2] Officials from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve) have stated publicly that despite identifying vulnerabilities and supervisory concerns before the failures, they did not take sufficient actions to ensure the institutions promptly addressed these issues. The failures have prompted questions from some Members of Congress and the public about bank supervision.

In March 2024, we found that the Federal Reserve and FDIC had identified numerous supervisory concerns at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank as early as 2018 but did not issue any enforcement actions, which would have required the institutions to address the problems.[3] We recommended that the Federal Reserve revise its escalation procedures to be clearer and more specific and to include measurable criteria.[4] The Federal Reserve agreed with the recommendation but has not yet implemented it. We also recommended that Congress consider requiring the adoption of noncapital triggers that require early and forceful regulatory actions tied to unsafe banking practices before they impair capital.[5] For example, Congress could amend the Federal Deposit Insurance Act to require corrective actions based on indicators other than capital adequacy (such as interest rate risk, asset concentration, and poor management).

This report follows up on our March 2024 report and examines the supervisory practices of all three federal banking regulators. Specifically, this report examines communication of supervisory concerns and processes and policies for escalating supervisory concerns for the three federal banking regulators: (1) the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), (2) the Federal Reserve, and (3) FDIC.

To assess the communications of supervisory concerns, we developed a data collection instrument to systematically collect information on the supervisory concerns issued by the three regulators from January 2018 through December 2022, the most current data at the time of our review. We collected and analyzed supervisory documentation from each regulator.[6] We selected a nongeneralizable sample of 20 depository institutions supervised by each regulator for a total of 60.[7] We selected the sample of institutions to ensure it included (1) a range of asset sizes; (2) CAMELS (capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk) ratings of 2 or 3, as of 2022; (3) geographic diversity in the regional offices overseeing the financial institutions; and (4) institutions with the highest total number of supervisory concerns issued by the regulators from January 2018 through May 2023.[8]

We focused our analysis on the regulators’ communications and on institutions’ remediation of supervisory concerns related to safety and soundness risks, such as credit, corporate governance, and management and liquidity. We reviewed the regulators’ internal examination policies and procedures to identify their requirements for communicating and escalating supervisory concerns in both annual and target examinations and for escalating concerns to informal and formal enforcement actions. We reviewed the regulators’ escalation guidance against applicable federal standards for internal control.

To assess the regulators’ supervisory concerns issued from January 2018 to May 2023, we collected administrative data from OCC, the Federal Reserve, and FDIC to produce descriptive statistics on the regulators’ supervisory concerns. We assessed the completeness and reliability of the data by performing electronic data testing to identify missing values, logical inconsistencies, outliers, or duplicates and found the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

We also interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of examiners in charge and examination team members who conducted examinations from January 2018 through May 2023. We interviewed 109 examiners across the three regulators. To select these examiners in charge and examiners, we selected three depository institutions for each regulator from our sample of 60, for a total of nine institutions. We selected these institutions to include (1) one institution from each of three asset groups (large, regional, and community); (2) at least one failed or liquidated institution; (3) institutions with supervisory concerns that had been open for a longer period relative to similar institutions; and (4) institutions from different geographic regions. We also interviewed seven experts in the fields of banking, finance, and economics. In selecting the experts, we sought a range of perspectives from academia, industry associations, and think tanks. See appendix I for more detail on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Banking Regulators

The purpose of federal banking supervision is to help ensure that depository institutions throughout the financial system operate in a safe and sound manner and comply with federal laws and regulations for the provision of banking services. In addition, federal banking supervision looks beyond the safety and soundness of individual institutions to promote the stability of the financial system as a whole. Each depository institution in the United States is primarily supervised by one of the following three federal banking regulators:[9]

· OCC supervises federally chartered national banks and savings associations and federally chartered branches and agencies of foreign banks.

· The Federal Reserve supervises state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System, bank holding companies and any non-depository-institution subsidiaries of a bank holding company, and savings and loan holding companies and any subsidiaries (other than depository institutions) of a savings and loan holding company, Edge Act and agreement corporations, and the U.S. operations of foreign banks.[10]

· FDIC supervises insured state-chartered banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System, state-chartered savings associations, and insured state-chartered branches of foreign banks.[11]

Bank Supervision Process

The federal banking regulators have broad authority to examine depository institutions subject to their jurisdiction. Under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, as amended, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC are required to conduct a full-scope, on-site examination of each insured depository institution they supervise at least once during each 12-month period. The regulators may extend the examination interval to 18 months, generally for institutions that have less than $3 billion in total assets and meet certain conditions, based on ratings, capitalization, and status of formal enforcement actions, among other factors.

Regulators assess the strength of depository institutions using the Uniform Financial Institutions Rating System, also known as CAMELS. The federal banking regulators rate an institution on each CAMELS component (capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk). Evaluations of CAMELS components consider an institution’s size and sophistication, the nature and complexity of its activities, and its risk profile. The regulators then give a composite rating (which closely relates to the component ratings but is not an average of them). Both the composite and component ratings are based on a scale of 1 (best) to 5 (worst). As an institution’s ratings worsen, corresponding supervisory actions generally increase in severity.

For large depository institutions, federal banking regulators generally do not conduct an annual point-in-time examination of the institution. Rather, they generally conduct ongoing on-site supervisory activities that are intended to evaluate the institution’s operating condition, management practices and policies, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Throughout the examination cycle, target examinations culminate in supervisory letters that are transmitted to the institution (where applicable).[12] At the end of the supervisory cycle, a report of examination is issued to the institution. The supervisory letters and report of examination may include supervisory concerns. For smaller depository institutions with less than $10 billion in assets, the regulators typically conduct single point-in-time, full-scope examinations.

OCC, the Federal Reserve, and FDIC have organized their supervision of financial institutions according to the asset size and complexity of the institutions they oversee (see table 1).

|

Regulator |

Program |

Structure |

Types and asset sizes of institutions in each program |

Number of depository institutions |

|

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) |

Large Bank Supervision |

Core teams are assigned to specific institutions and are housed in OCC offices or embedded on-site with institutions. |

Large institutions generally with assets between $100 billion and $3 trillion |

28 |

|

Midsize and Trust Bank Supervision |

Core teams are assigned to specific institutions and are housed in OCC offices or embedded on-site with institutions. |

Midsize institutions, including federal savings associations with assets between $15 and $115 billiona |

63 |

|

|

Community Bank Supervision |

Supervision is conducted through six regions: East, Northeast, South, Southeast, Midwest, and West. |

Community institutions, including federal savings associations with assets of less than $15 billion |

850 |

|

|

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

Large Institution Supervision Coordinating Committee Program |

Supervision focuses on individual institutions’ safety and soundness and U.S. financial stability. Supervision includes the use of both institution-specific examinations and “horizontal” reviews.b |

Institutions that pose elevated risk to U.S. financial stability (for example, Bank of New York Mellon and State Street and Trust) |

4 |

|

Large and Foreign Banking Organization Program |

Each Reserve Bank supervises the large banking institutions located in its district, with support and oversight from staff at the Board of Governors. |

U.S. institutions with total assets of $100 billion or more and all foreign banking institutions operating in the U.S. regardless of asset size |

7 |

|

|

Regional Banking Organization Program |

Each Reserve Bank supervises the institutions located in its district with support from staff at the Board of Governors. |

U.S. institutions with total assets between $10 billion and $100 billion |

40 |

|

|

Community Banking Organization Program |

Each Reserve Bank supervises the institutions located in its district with support from staff at the Board of Governors. |

U.S. institutions with less than $10 billion in total assets |

654 |

|

|

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) |

Continuous Examination Process |

Due to the size and complexity of these institutions, staff are dedicated to a specific bank and use a continuous examination process. |

Institutions that are larger, more complex, or present a higher risk profile |

55c |

|

Point-in-Time Examination Process |

Examination teams located at field offices conduct point-in-time examinations. |

Institutions that are generally smaller or less complex |

2,853 |

Source: OCC, Federal Reserve, and FDIC. | GAO‑24‑106771

aThe asset levels of Midsize and Trust Bank Supervision overlap with Large Bank Supervision.

bHorizontal reviews involve examining several institutions simultaneously, and they encompass institution-specific supervision and the development of cross-institution perspectives.

cFive of the institutions have less than $10 billion in assets but are part of the continuous examination process because of their complexity.

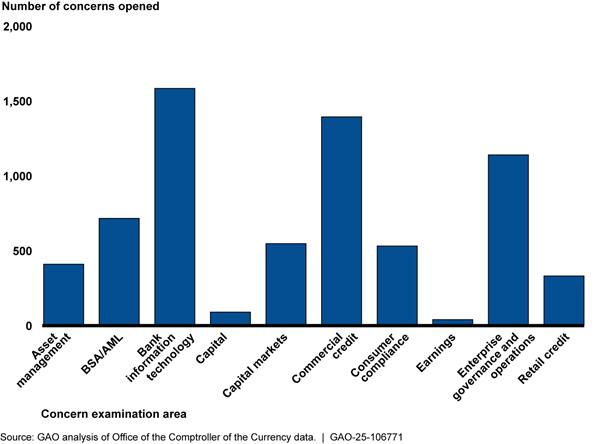

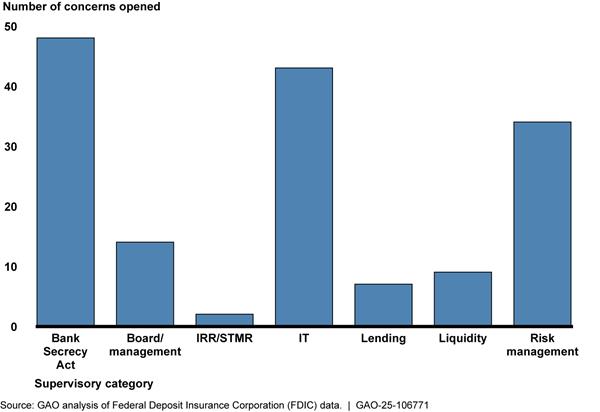

Supervisory concerns cover various topics related to safety and soundness and compliance with laws and regulations. For example, among the supervisory concerns OCC issued from January 2018 through May 2023, the most common were related to information technology, enterprise governance and operations, and commercial credit, which includes concerns related to commercial real estate risks.

Communicating and Escalating Supervisory Concerns

All three federal banking regulators have established requirements or guidance on the communication of supervisory concerns to the depository institutions. The regulators use various supervisory concerns and enforcement tools to communicate with institution management and to correct unsafe or unsound banking practices. See table 2 for the types of supervisory concerns issued by each regulator.

|

Level of severity |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Minor concern resolved in normal course of business |

Matter requiring attention |

No categorya |

Supervisory recommendation |

|

Serious concern resolved in normal course of business |

Matter requiring attention or informal or formal enforcement action |

Matter requiring attention |

|

|

Serious concern that demands immediate board attention |

Matter requiring attention or informal or formal enforcement action |

Matter requiring immediate attention |

Matter requiring board attention |

|

Typically, CAMELS composite rating of 3, 4, or 5, or lack of adequate institution response to serious concern that demands immediate response or triggers certain legal actions |

Informal or formal enforcement action |

Informal or formal enforcement action |

Informal or formal enforcement action |

Source: Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. | GAO‑24‑106771

aThe Federal Reserve may not issue written supervisory concerns for minor concerns resolved in the normal course of business.

FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC employ progressive enforcement regimes to address supervisory concerns that arise during the examination cycle. If an institution does not respond in a timely manner or address the issue sufficiently, the regulators may take informal or formal enforcement actions, depending on the severity of the circumstances. An example of an informal enforcement action would be obtaining an institution’s commitment to implement corrective measures under a memorandum of understanding. Formal enforcement actions include, for example, issuance of a cease-and-desist order and assessment of a monetary penalty.

All three regulators have established procedures to escalate supervisory concerns to informal and formal actions.

· OCC. OCC policy states that when an institution receives a CAMELS composite rating of 3, the agency will likely issue a formal enforcement action following the supervisory letter or report of examination. The policy also states that OCC will likely issue a cease-and-desist order, consent order, or other actions for institutions with composite ratings of 4 or 5. Additional escalation factors OCC can consider include the institution’s risk profile; the nature, extent, and severity of the deficiencies; the extent of unsafe or unsound practices; and the board and management’s ability and willingness to correct deficiencies within an appropriate time frame.

· Federal Reserve. According to Federal Reserve guidance, informal enforcement actions generally are used for depository institutions with a composite CAMELS rating of 3. Formal enforcement actions generally are used for institutions with a composite rating of 4 or 5. The guidance also includes 10 factors that examiners are to consider in determining whether to escalate a concern. These include the institution’s supervisory rating and financial condition, the number of open supervisory concerns, the materiality of the open concerns to the institution’s safety and soundness, and the institution’s history of instituting timely corrective actions.

· FDIC. FDIC policy states that formal or informal enforcement actions are typically taken against institutions with a composite CAMELS rating of 3 or worse. The policy further states that FDIC may pursue enforcement actions regardless of the composite CAMELS rating if the “specific facts and circumstances make such an action appropriate.” The policy lists a number of escalation factors that are designed to assist examination staff in determining whether to seek informal or formal action. On August 29, 2023, FDIC issued a memorandum that advised examiners to (1) consider elevating a matter requiring board attention to an enforcement action if the matter was repeated or uncorrected at the end of an examination cycle and (2) elevate concerns to at least a matter requiring board attention if supervisory recommendations were repeated or remained uncorrected at the next examination cycle.

OCC Followed Guidance for Communicating and Escalating Supervisory Concerns for Selected Institutions

OCC Examiners Consistently Followed Guidance for Communicating Supervisory Concerns to Selected Institutions

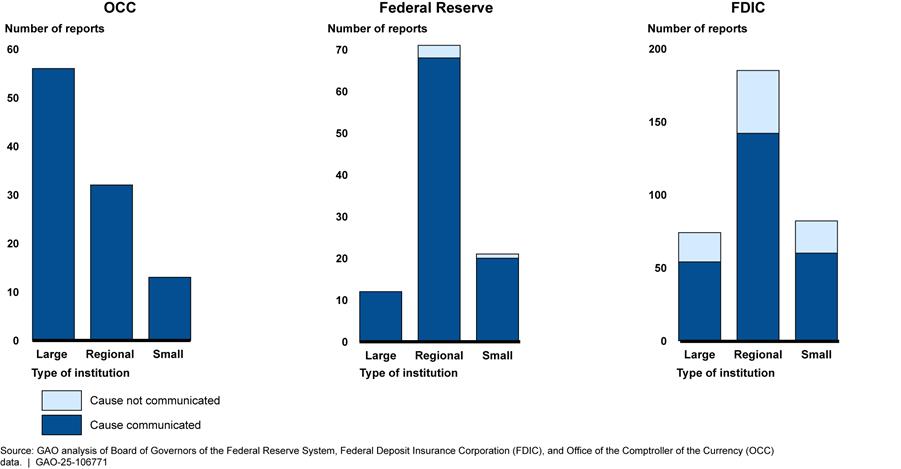

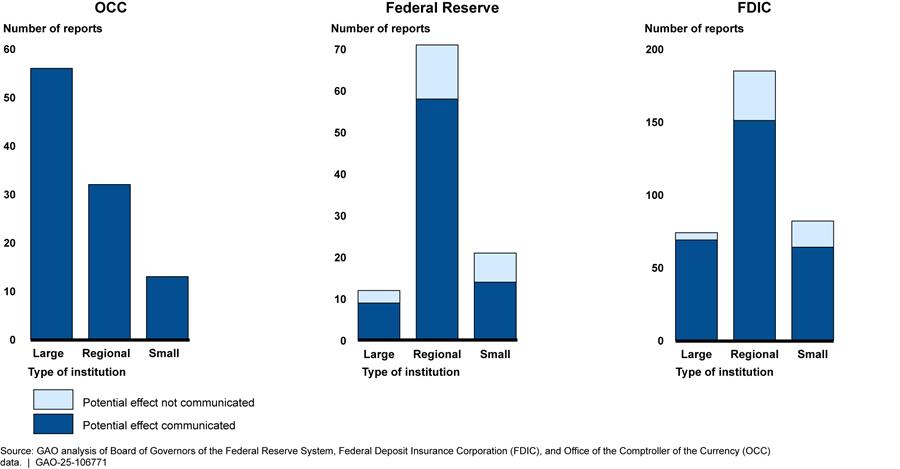

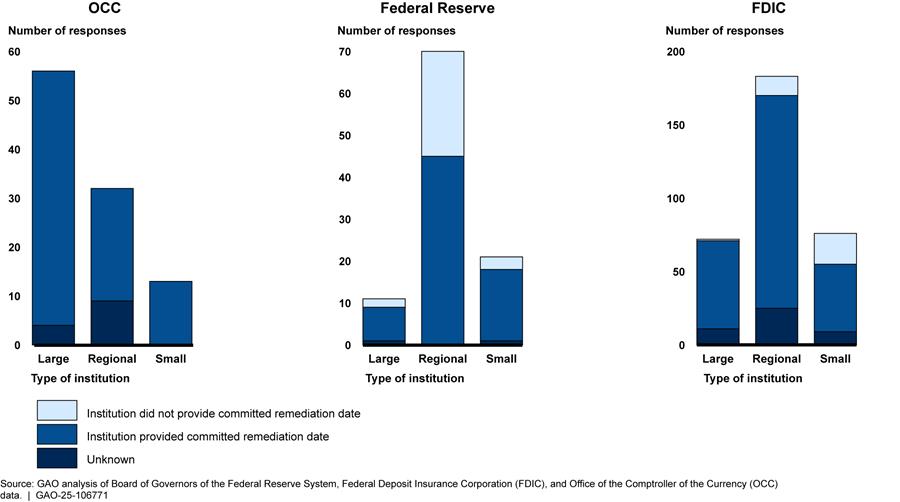

We found that OCC examiners consistently followed agency guidance for communicating supervisory concerns to institutions in our review of a nongeneralizable sample of 101 supervisory concerns to 19 selected depository institutions from January 2018 through May 2023.[13] According to the OCC Comptroller’s Handbook, communications of supervisory concerns include five elements: description of the concern, cause of the deficiency, consequences of not remediating the deficiency, corrective actions required, and a request for commitment to remediation by a specific date.[14] All the communications we reviewed included each of these elements (see app. II).

OCC policy states that examiners are required to issue reports of examination within 90 or 120 days of the examination’s start, depending on the condition of the institution. Additionally, officials from OCC’s Large Bank Supervision office told us they expect supervisory communications to be delivered to institutions within 45 days from the date that examination fieldwork is complete. Our review of 42 selected communications to three OCC-supervised institutions (from January 2018 through May 2023) found that communications were generally issued in a timely manner.[15] Specifically, 39 of these communications (93 percent) met OCC’s requirements and expectations for timely communication. The three communications that did not meet timeliness standards had waivers for communication time frames with documented explanations.

OCC Generally Closed Supervisory Concerns within 12 to 18 Months, Though Some Remained Open Longer

OCC policy requires institutions to submit an initial response with an action plan for remediation within 30 days of receiving a supervisory concern. We found that institutions consistently responded within this time frame in the nongeneralizable sample of supervisory communications we reviewed. All the OCC-supervised institutions in our sample provided a committed remediation date in their response to the concerns. The committed remediation dates were generally longer for large institutions than for regional and smaller institutions.

OCC officials told us there is no specific time frame requirement for remediating supervisory concerns. Instead, the institution and supervisory office negotiate a commitment date for remediating each supervisory concern. These officials and OCC examiners told us the length of time it takes to remediate a concern depends on several factors. These include the actions required, the severity of the concern, resources required to implement the actions, and the timing of activities required to verify and validate the effectiveness and sustainability of the institution’s corrective actions.

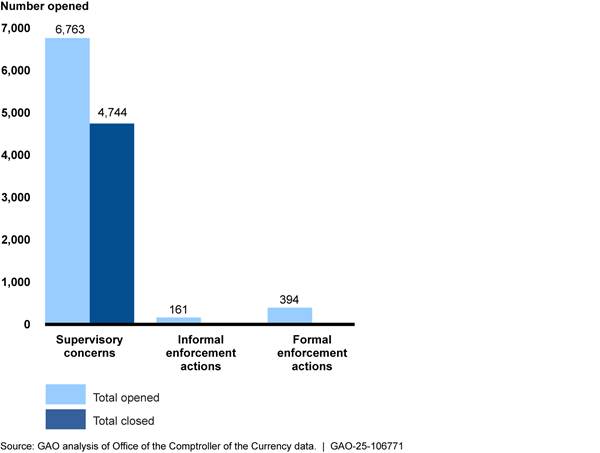

OCC requires examiners to assess an institution’s progress in addressing supervisory concerns quarterly until they validate the sustainability of the institution’s corrective actions. OCC policy favors taking additional supervisory or enforcement actions when an institution has continuing, recurring, or increasing deficiencies for a prolonged period (generally defined as more than 3 years), particularly when the institution has made insufficient progress in correcting the deficiencies.

Our review of administrative data on all 6,775 supervisory concerns that OCC issued to supervised institutions from January 2018 through May 2023 found that concerns generally closed within 12 to 18 months. An estimated 72 percent of concerns closed within 2 years, while approximately 12 percent closed between 2 and 3 years. Approximately 4 percent closed between 3 and 4 years.[16] The remaining 12 percent of supervisory concerns were open for more than 4 years and were primarily associated with the examination issue areas of commercial credit, enterprise governance and operations, and information technology. OCC examiners noted that concerns involving enterprise-wide issues or technology can take longer to close due to their complexity and the resources required for remediation.

Approximately 9 percent of concerns issued in 2018 remained open and pending remediation as of May 2023, when our sample time frame ended. These concerns were associated with 26 institutions, and approximately half were linked to enforcement actions. See appendix III for more details.

OCC Has Established Escalation Procedures and Generally Escalated Concerns According to These Procedures

As previously noted, OCC has established escalation procedures, which include a number of factors that examiners are to consider in determining whether to escalate a concern. These factors include the institution’s supervisory rating and financial condition, number of open supervisory concerns, and history of instituting timely corrective actions.[17] Examiners that supervised one of the institutions in our sample told us these factors are clear but can sometimes be difficult to apply. For example, they said that for complex issues involving many supervisory concerns with a potentially similar root cause, they would want to avoid escalating too many different concerns into a single enforcement action. They said this kind of situation may require additional analysis to determine which concerns need to be escalated to the enforcement action.

OCC management and multiple examination teams described escalation procedures including collaborative decision-making through formal vetting of issues. These vetting sessions provide a forum for discussing key examination findings and deliberating potential supervisory concerns or enforcement actions. Participants in these discussions may include the deputy comptroller, assistant deputy comptrollers, examiners in charge, team leads, subject-matter experts, legal staff, and examiners participating in the examination. OCC procedures also describe supervision review committees that review or make enforcement decisions and promote consistent application of policies. Examiners told us they were not aware of an instance where their supervisory office disagreed with their findings or told them to change their recommendations. They added that any challenges happen early in the process and are resolved before reaching the draft recommendation stage.

OCC also has procedures for documenting divergent views that emerge during the decision-making process. Under the updated Large Bank Supervision template used to document examination conclusions, examiners must document why a proposed matter requiring attention or potential violation was not included in the final supervisory letter sent to the institution. This documentation must include an explanation for the omission, which may draw from internal deliberations or other documents. These documentation requirements aim to increase transparency and accountability for decision-makers.

OCC has established rotation requirements for examiners in charge of large institutions. OCC policy states that these requirements promote objectivity, cross training, and growth in expertise among examiners. Rotation requirements are one way to guard against regulatory capture. We have defined regulatory capture as a condition that exists when a regulator acts in service of private interests, such as the interests of the regulated industry, at the expense of the public interest.[18] Regulatory capture can hinder timely and appropriate escalation. Captured regulators may make decisions that inappropriately benefit the institutions they oversee, such as overlooking risky practices or failing to impose appropriate penalties.

Our review of selected supervisory communications and discussions with examiners suggested that OCC followed its policy in instances where supervisory concerns were escalated to enforcement actions. OCC policy states that whenever possible, a proposed enforcement action should be presented to the institution within 180 days of the start of a supervisory activity that results in communication of significant deficiencies. We did not identify any instances in our sample where OCC’s escalation criteria appeared to be met but the concern was not escalated. OCC’s response to one community bank in our sample illustrates an example of timely and appropriate escalation:

· An annual report of examination described the bank’s increasing risk profile and included multiple supervisory concerns, noting the bank’s inadequate risk assessments and insufficient credit risk management processes.

· Approximately 3 months later, OCC began a target examination of the bank’s financial technology line of business, conducted due to the bank’s inadequate planning and management of increasing risks in its financial technology activities. The examination identified two violations of laws and regulations. It included new supervisory concerns and escalated prior supervisory concerns to an informal enforcement action. The bank was required to submit a safety and soundness plan, with a warning that failure to remediate these issues would result in further escalation.

· The subsequent annual report of examination noted that the bank’s board and management had not achieved compliance with their submitted plan and continued to aggressively grow the financial technology line of business. This report identified additional violations of laws and regulations and multiple new supervisory concerns, prompting OCC to escalate these items to a formal enforcement action.

Federal Reserve Generally Followed Its Communication Guidance for Selected Institutions, but Its Process for Escalating Concerns Has Weaknesses

We found that the Federal Reserve generally adhered to its guidance for communicating key details of supervisory concerns to selected institutions and has procedures for determining when to escalate a supervisory concern to an enforcement action. However, the Federal Reserve has not issued a regulation or enforceable guidelines on corporate governance and risk management, even though it has the statutory authority to do so, and has not finalized a rule related to early remediation standards, which may hinder escalation of concerns.

Federal Reserve Generally Adhered to Its Guidance for Communicating Selected Supervisory Concerns

Required Communication Components

Federal Reserve examiners generally followed agency guidance for communicating key details of concerns to selected institutions. Specifically, our review of a nongeneralizable sample of supervisory concern communications from January 2018 through May 2023 found that 98 of the 104 concerns we reviewed included most or all of the required components (see app. II for detailed analysis).[19]

In a 2019 report, we found that some Federal Reserve supervisory communications did not provide information on the cause or potential effect of a supervisory concern.[20] We recommended that the Federal Reserve require examiners to provide more complete information about the concerns, such as the likely cause and potential effect of the deficiency. In 2020, the Federal Reserve updated relevant manuals to require that communications of supervisory concerns include, if evident, both the root cause and potential effect of the finding on the institution. We determined that this modified guidance addressed our recommendation.[21]

Our review of selected communications from January 2021 through May 2023, following the Federal Reserve’s 2020 updates, found general alignment with its new guidance. Specifically, we found that 31 out of 33 communications (94 percent) identified a cause, and 29 out of 33 communications (89 percent) identified a potential effect. These communications also generally included most of the other elements described in the guidance, which emphasizes using clear and concise language, prioritizing findings by importance, focusing on significant matters that require attention, and using standardized language.

Timeliness of Communication

We found that Federal Reserve examiners generally issued communications in a timely manner, on the basis of our review of timeliness information for 177 communications to three institutions of different asset sizes from February 2018 through December 2023.[22]

The Federal Reserve expects examination reports or letters to be issued to institutions within certain time frames, depending on the category and size of the institution. Examination reports or letters are expected to be issued

· to community institutions within 60 days of the closing date of the examination and less than 90 days after the start of the examination;

· to regional institutions within 90 days of the examination start date for noncomplex holding companies and within 100 calendar days of the start date for state member institutions; and

· to large institutions within 60 days of the examination closing date.

For a majority of the selected supervisory communications we reviewed, the issuance time frames fell within the expectations for each of the three institutions. For the community and regional institutions, we found that 15 of the 18 communications (83 percent) in the sample met the expectations, and for the large institution, 89 of the 160 communications (56 percent) in the sample met the expected issuance time frame. However, for the regional institution in the sample, we found that one communication exceeded the expectation by 56 days. For the large institution in the sample, we found that communications that did not meet timely issuance expectations exceeded these expectations by a median value of 28 days.

Federal Reserve officials cited several reasons for delays in issuing examination reports. They said delays can occur when supervisory findings are being escalated to enforcement actions, requiring discussion with enforcement, legal, and analyst staff and state regulators to confirm that the letter supports escalation. Additionally, the emergence of new or material issues during the vetting or report processing phases can cause delays. Reports may also be delayed if they involve complex or borderline issues that require vetting, or if they require additional research or legal interpretation of complex or technical matters.

Institutions’ Response to and Remediation of Concerns

Federal Reserve policy requires institutions to respond in writing to communications of supervisory concerns regarding any completed or planned corrective actions.[23] This policy does not specify a required time frame to provide written responses, but all 104 communications in our nongeneralizable sample included time frames for institutions to respond, such as 45 days. These response requirements were met for 92 of the 104 communications (88 percent) in our nongeneralizable sample and generally included a committed remediation date.[24]

However, Federal Reserve officials said they have not designated standardized time frames for remediating all supervisory concerns, as the complexity and severity of issues vary. They said that supervisory concerns are not all the same and that the time required to remediate a concern depends on the specific issue, its context, and the institution involved. Therefore, they said, remediation time frames for individual supervisory concerns are created to ensure the institution correctly remediates the concern. Officials further noted that examiners may require institutions to implement compensating controls or other temporary measures until issues are fully remediated. Federal Reserve examiners told us that in some cases, it may take an institution’s management one or two annual examination cycles to fully understand the root cause of the issue.[25]

Federal Reserve policies require the supervising Reserve Bank to follow up on matters requiring attention and matters requiring immediate attention to assess progress and verify satisfactory completion. The Federal Reserve uses a central tracking system for follow-up on supervisory concerns over time. Reserve Bank staff monitor the status of concerns, and follow-up actions vary depending on the nature and severity of the matter. These actions may include subsequent examinations or other supervisory activities deemed suitable for evaluating the issue.

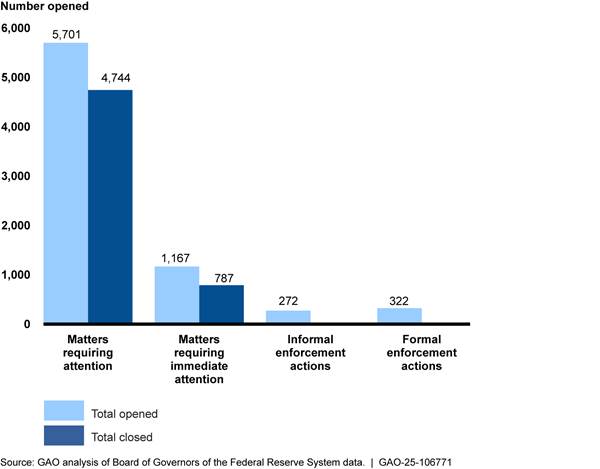

See appendix III for additional data on the Federal Reserve’s supervisory concerns issued and closed from January 2018 through May 2023.

The Federal Reserve Has Escalation Procedures and Is Considering Required Time Frames for Escalation

The Federal Reserve’s procedures, similar to OCC’s, include several factors examiners are to consider in determining whether to escalate a concern. These factors include the institution’s supervisory rating and financial condition, number of open supervisory concerns, and history of implementing timely corrective actions.[26] The Federal Reserve’s escalation process also involves collaborative decision-making through formal vetting of issues, according to Reserve Bank policy documents and interviews with Federal Reserve examiners. In addition, each Reserve Bank has a process for documenting and reviewing any divergent views that may arise during supervisory activities.

The Federal Reserve has a policy of preparing certain routine enforcement actions that involve safety and soundness concerns within 50 days. However, it does not have required time frames for issuing nonroutine, complex enforcement actions to institutions. In contrast, OCC’s policy is to present proposed enforcement actions to banks within 6 months of the start of the supervisory activity that identified the action. Unlike OCC, the Federal Reserve must coordinate with state banking agencies when considering escalation decisions, which can affect the timeline. The Federal Reserve said that while it may establish internal expectations for timeliness, it does not have authority to commit state banking agencies to these expectations.

In our review of a nongeneralizable sample of Federal Reserve examination documents, we found long time frames between the identification of concerns and the issuance of enforcement actions. In some instances, the Federal Reserve took more than 6 months from the start of a supervisory activity to issue a nonroutine, complex enforcement action. For example:

· In June 2022, the Federal Reserve downgraded a large institution. It issued an informal enforcement action about 10 months later, in April 2023.

· As we previously reported, Federal Reserve officials told us that although they initiated an informal enforcement action against Silicon Valley Bank in July 2022, examiners did not finalize the action before the bank failed in March 2023.[27]

In March 2024, we recommended that the Federal Reserve revise its escalation procedures to be clearer and more specific and to include measurable criteria.[28] The Federal Reserve agreed with the recommendation, and its staff told us they are updating their framework for escalating supervisory findings to enforcement actions. As part of this effort, they said they are considering whether required time frames for more complex enforcement actions are appropriate, including for those that raise legal or policy issues or that require more extensive coordination. Because more complex enforcement actions likely have a larger impact, establishing time frames for such actions would be prudent. We will continue to monitor the Federal Reserve’s progress in implementing our recommendation.

Federal Reserve Does Not Have Regulation or Enforceable Guidelines on Corporate Governance and Risk Management, Potentially Hindering Escalation

The Federal Reserve has established supervisory guidance on corporate governance and risk management standards, but it has no specific regulations or enforceable guidelines for escalating supervisory concerns on these issues.[29] The Federal Reserve’s Commercial Bank Examination Manual details supervisory expectations for board directors and management, including general duties and responsibilities and oversight of liquidity risks, and it provides guidance for assessing risk management practices.[30] In addition, under section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, the Federal Reserve may prescribe operational and managerial standards by regulation or guidelines.[31] Effective May 2021, the Federal Reserve’s regulation on procedures was amended to include an appendix that states that the agency “will not issue an enforcement action on the basis of a ‘violation’ of or ‘noncompliance with’ supervisory guidance.”[32] The final rule’s preamble states that the Federal Reserve will continue to robustly use guidance to support safety and soundness and promote compliance.[33] However, the final rule clarified that, unlike a law or regulation, supervisory guidance does not have the force and effect of law. It also noted that the Federal Reserve does not take enforcement actions based on supervisory guidance.

Federal Reserve officials told us examiners have been able to sufficiently address corporate governance weaknesses using matters requiring attention. As a result, officials believe it unnecessary to convert the guidance to regulation. The officials said that, while the Federal Reserve does not have specific regulations or enforceable guidelines on corporate governance and risk management for large state-member banks, large bank holding companies are already subject to enhanced prudential standards that include corporate governance and risk management requirements.[34] The officials said that section 8(b) of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act allows them to take an enforcement action for any violation of law or unsafe or unsound practice.[35]

However, despite identifying numerous corporate governance and risk management concerns at Silicon Valley Bank, the Federal Reserve did not pursue an enforcement action until the bank was near collapse.[36] The lack of regulation on corporate governance and risk management may have contributed to delays in taking more forceful action against Silicon Valley Bank, exposing a potential gap in the Federal Reserve’s supervisory toolkit.[37]

In contrast to the Federal Reserve, OCC and FDIC have the same authority under section 8(b) of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act but chose to establish specific regulations with enforceable guidelines on corporate governance and risk management.

· Since fall 2014, OCC has had “heightened standards” in its regulations codified as enforceable guidelines under section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act for insured national banks with assets of $50 billion or more. These standards include minimum standards for the design and implementation of a bank’s risk governance framework and board oversight of the framework.[38] OCC examiners told us this rule has been helpful in addressing governance and risk management issues because escalation is based on regulation rather than agency guidance.

· In October 2023, FDIC issued proposed rules to similarly convert agency guidance on corporate governance and risk management into regulation proposed to be codified as enforceable guidelines issued under section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act.[39] FDIC officials told us they recognized that these issues contributed to Signature Bank’s failure. The supplementary information published with the proposed guidelines emphasizes the need for larger or more complex institutions to have more sophisticated and formal board and management structures and practices to ensure appropriate corporate governance. The supplementary information also states that regulators should have the authority to intervene when these structures and practices are inadequate or do not match the institution’s risk level.

A report on the spring 2023 bank failures by the Bank for International Settlements highlighted this issue. It stated that supervisors had warned the distressed banks about governance issues that posed risks to their safety and soundness, but these warnings did not drive sufficient change to prevent stress.[40] It noted that without regulatory authority, supervisors may have to rely on less robust tools to incentivize banks to address risks, which may prove less effective. The report recommended that regulators review their supervisory tools to ensure they are sufficient to encourage corrective action by banks and consider any regulatory constraints on their application.

By promulgating a regulation or enforceable guidelines on corporate governance and risk management under section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, as the other regulators have done, the Federal Reserve could give examiners a specific tool to escalate corporate governance and risk management concerns and could more easily take early, forceful regulatory actions tied to unsafe banking practices before they impair capital.

Federal Reserve Has Not Finalized a Rule Related to Early Remediation Standards

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act directed the Federal Reserve to establish early remediation standards for nonbank financial companies and certain bank holding companies.[41] The standards are to require the Federal Reserve to intervene quickly, rather than waiting until a financial institution is about to fail. Specifically, section 166 of the act requires the Federal Reserve to establish an early intervention framework based on forward-looking financial metrics in addition to an institution’s capital levels. Examples of such metrics could include noncapital triggers based on liquidity metrics, risk management weaknesses, and other market indicators.[42] The statutory deadline for implementing section 166 was January 2012.[43]

The Federal Reserve proposed a rule in 2012 to implement early remediation standards for large bank holding companies, but it was never finalized.[44] Officials acknowledged that section 166 has not been fully implemented. They said the agency received substantial comments requiring further consideration to avoid implementing rules that duplicate existing regulations. The officials also noted that many risks intended to be addressed by the proposed rule under section 166 were being addressed in other rules.

Federal Reserve officials noted that the agency’s existing regulatory framework addresses numerous aspects of section 166. For example, they stated that existing rules on capital, capital planning, and total loss-absorbing capacity establish heightened requirements that restrict capital distributions or require capital raising when firms’ capital levels decline.[45] They also stated that existing rules on the liquidity coverage and net stable funding ratios require firms to notify regulators of liquidity shortfalls and submit remediation plans.[46] In addition, officials noted they already can take measures like restricting acquisitions and asset growth and requiring asset sales.[47] Given these existing regulations and powers, officials told us that reintroducing rulemaking for section 166 has not been a priority.

In addition, Federal Reserve officials expressed concern that the proposed rule could have unintended consequences. For example, punishing firms for not complying with the minimum requirements for the liquidity coverage ratio and net stable funding ratio could discourage the firms from using liquidity buffers to maintain regulatory ratios. A purpose of these requirements—especially the liquidity coverage ratio—is to ensure that firms hold sufficient liquid assets relative to their risk profile to meet their liquidity needs during stress. Therefore, it is appropriate and desirable for a firm to use its liquid assets to meet its liquidity needs under certain circumstances rather than hoard those assets to maintain regulatory ratios. However, a firm may choose not to use its liquid assets when needed if it will be punished for not complying with the minimum requirements. Further, they said the proposed rule included market indicators, which present policy and procedural challenges when tied to automatic and escalating triggers. Specifically, counterparties could be incentivized to act in a way that impacts market indicators if they know it will trigger a specific consequence.

However, Congress entrusted the Federal Reserve to develop a framework that balances these concerns with the ability to take early actions to prevent bank failures. Some commentators contend that the Federal Reserve’s partial measures do not satisfy Congress’s intent.[48] Subject-matter experts we interviewed noted, and Federal Reserve officials acknowledged, that key aspects of the 2012 proposed rule designed to implement section 166 remain unimplemented. These include the proposed rule’s restrictions on capital distributions, market-based triggers, and changes to the liquidity coverage ratio, which are not currently part of the Federal Reserve’s existing regulatory framework.[49]

In our March 2024 report, we recommended that Congress consider requiring the adoption of noncapital triggers that require early and forceful regulatory actions tied to unsafe banking practices before they impair capital.[50] As noted, section 166 already includes such triggers. In addition, since 2023, an interagency working group on liquidity involving FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC has been meeting weekly. According to officials, the group is working to address the types of liquidity deficiencies that contributed to losses at a number of banks, including Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank.[51] Officials did not provide a time frame for when any proposal by the group would be finalized.

In the meantime, by issuing a regulation to fully implement section 166, the Federal Reserve would help achieve the statutory goal of minimizing the risk of insolvency among nonbank financial companies and certain bank holding companies, thereby promoting financial stability.

FDIC Generally Followed Guidance for Selected Concerns, but Weaknesses in Escalation Processes Risk Inconsistent Action

FDIC generally followed guidance for communicating key details of supervisory concerns to selected institutions. However, certain limitations in FDIC data and policies—such as a lack of vetting procedures for large bank examination findings and rotation requirements for case managers—may hinder its escalation of concerns.

FDIC Generally Adhered to Guidance for Communicating Selected Supervisory Concerns

Required Communication Components

FDIC generally followed guidance for communicating key details of concerns to institutions in our review of a nongeneralizable sample of communications of supervisory concerns. Across all communications of supervisory concerns we reviewed, 323 of 341 (95 percent) included most or all of the components instructed in FDIC’s guidance.[52] See appendix II for details on FDIC’s adherence to communication requirements.

In 2019, we found that some FDIC supervisory communications from a sample of three institutions did not provide information on the cause of supervisory concerns.[53] We recommended that FDIC update its policies and procedures on communications of supervisory recommendations to institutions to provide more complete information, such as the likely cause of the problem or deficient condition, when practicable. In 2019, FDIC reported that it had formalized its policies and procedures on root cause analysis, which addressed our recommendation. We found that 130 of the 163 communications in our sample (80 percent) from January 2020 through May 2023 (after the guidance was in place) identified a cause.

FDIC’s guidance on communicating supervisory concerns also includes additional instructions, such as for describing the deficiency (including an introductory statement, a description of the concern, and the corrective action needed); reminding institutions’ management of the importance of addressing issues; listing supervisory concerns in order of importance; and communicating clearly. FDIC examiners generally followed these instructions in the nongeneralizable sample of communications we reviewed.

Timeliness of Communication

FDIC has established internal goals for timely sharing of information with institutions.[54] One goal is the timely transmission of safety and soundness reports to financial institutions, such that reports issued within a 12-month period have an overall median time frame of 75 days from the on-site examination start date to report transmission. Another goal is completion of report processing—from finishing field work to sending the report to the institution—within a median time frame of 45 days over a 12-month period. A 2018 memorandum clarifies that these median timeliness goals are not requirements for individual examinations and that the goals exclude institutions subject to the continuous examination process.

In 2024, FDIC reported on examination turnaround times and noted that the agency met its internal goals for timely communications.[55] Specifically, FDIC’s analysis showed that over a 12-month period, the time frames for issuing reports of examination had a median turnaround time of 60 days from the start of the examination and a median processing time of 25 days after field work was complete.

FDIC’s internal goals for sharing timely examination information with institutions are broad and allow for variation. Examiners we spoke with explained that delays can occur due to certain circumstances, such as changes to a bank’s CAMELS ratings, supervisory issues related to trust and information technology, or the need for significant edits to initial findings made by the regional office or state regulator during joint examinations.

Institutions’ Response to and Remediation of Concerns

FDIC policy requires examiners to discuss tentative findings and supervisory recommendations with the financial institution’s management prior to the conclusion of an examination and to provide management an opportunity to respond. Agency policy also states that in some cases, supervisory communications can request that the bank provide a written response to the examination, although it does not specify a required time frame for these responses. In the nongeneralizable sample of 341 supervisory communications we reviewed, 288 (84 percent) specified a required response date. Institutions generally met this requirement and provided a committed remediation date.[56] The expected remediation time frames were generally longer for large and regional institutions than for small institutions.[57]

FDIC requires interim contacts with institutions to monitor progress on matters requiring board attention and supervisory recommendations. Case managers are to review institution management’s response to examination reports and follow up on the disposition and resolution of these concerns between examinations. However, in August 2023, FDIC revised its escalation guidance to require examiners to consider elevating a supervisory recommendation to a matter requiring board attention, and a matter requiring board attention to an enforcement action, if the concern is repeated or uncorrected at the next examination cycle. If examiners choose not to escalate, they must provide written justification to regional office management.

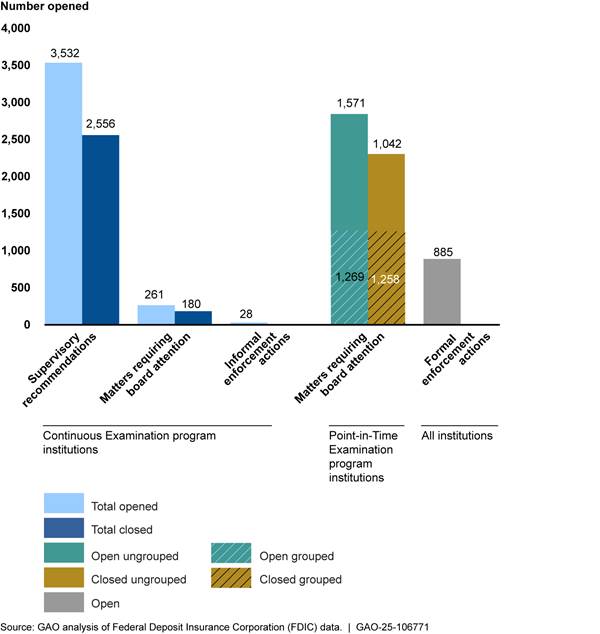

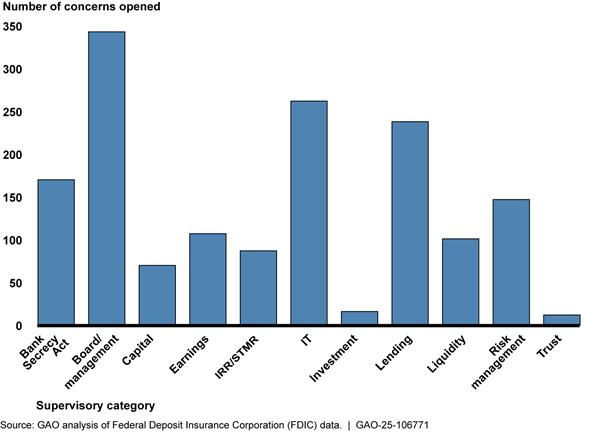

FDIC officials told us that they expect institutions to remediate supervisory recommendations (other than matters requiring board attention) during the normal course of business, meaning institutions should generally address supervisory recommendations within months of receiving the report of examination. FDIC expects institution boards of directors to remediate matters requiring board attention within an examination cycle. However, not all concerns close within this time frame.[58] FDIC examiners from one institution told us remediation can take longer for larger institutions, especially if the issue involves information technology or enterprise-wide response across multiple units. In the case of Signature Bank, supervisory concerns related to liquidity issues were identified in the 5 years before the bank failed.[59] See appendix III for details on FDIC’s closure of supervisory concerns.

Certain Limitations in FDIC Data and Policies May Hinder Its Effective Escalation of Concerns

FDIC Does Not Have a Central Tracking System for Supervisory Recommendations

FDIC’s existing tracking methods do not provide headquarters managers and staff with readily available information on supervisory recommendations.[60] Supervisory recommendations refer to FDIC communications with an institution that are intended to inform the institution of FDIC’s views about changes needed in its practices, operations, or financial condition. When we requested data on these recommendations, FDIC staff had to manually compile and process spreadsheets created by examiners to provide the necessary information. For community banks, officials told us that the request would require extracting supervisory recommendation data from examination documentation, as it was not otherwise readily available. In contrast, OCC and the Federal Reserve centrally track all their supervisory concerns and provided readily available data.

Federal internal control standards state that management should use quality information to achieve objectives.[61] Quality information is appropriate, current, complete, accurate, accessible, and provided on a timely basis. Management uses quality information to make informed decisions and evaluate the entity’s performance in achieving key objectives and addressing risks.

The absence of centralized tracking of supervisory recommendations prevents FDIC from leveraging these data to identify emerging risks and target its reviews more effectively. According to an analyst in the Large Bank Supervision Branch, the absence of centralized tracking has hindered efforts to aggregate related issues across institutions, limiting opportunities for horizontal examinations (i.e., examining the same issue across multiple institutions).[62] Because supervisory recommendations are common and may detect key issues early, implementing centralized tracking could help FDIC managers and examiners identify common emerging risks across all supervised institutions.

In addition, the absence of centralized tracking hinders FDIC’s ability to ensure proper implementation of its new policy of escalating concerns after one examination cycle. Currently, individual examination teams may be aware of when supervisory recommendations are opened and escalation is triggered, but recommendations are not tracked in the aggregate. Without centralized tracking of supervisory recommendations, FDIC management does not have the comprehensive visibility needed to ensure consistent application of the new policy across examination teams.

FDIC Lacks Processes to Ensure Managers Formally Consult Large Bank Examiners on Escalation

FDIC uses composite CAMELS ratings to determine whether to escalate a supervisory concern to an enforcement action. FDIC’s Formal and Informal Enforcement Actions Manual states that formal or informal enforcement actions are typically taken against an institution with a composite CAMELS rating of 3 or worse. In addition, FDIC requires examiners to consider elevating a matter requiring board attention to an enforcement action if the matter is repeated or uncorrected at the end of an examination cycle. If an examiner believes such a case does not warrant escalation, the examiner must provide written justification to regional office management, which makes a final determination.[63] In addition, the manual includes 11 factors to consider in determining whether to take informal or formal enforcement actions, regardless of the CAMELS rating.

FDIC officials described their process for making key examination decisions, including decisions about escalation, as iterative, with ongoing communications during supervisory activities. According to FDIC procedures, case managers should discuss any significant changes to examination findings with examiners in charge prior to finalizing the report. In addition, FDIC procedures require case managers to complete a feedback form for examiners in charge, which provides reasons for substantive report changes. These procedures apply to both Point-in-Time Examination and Continuous Examination process case managers.

However, unlike OCC and the Federal Reserve, FDIC does not require “vetting” meetings for managers (including case managers, assistant regional directors, deputy regional directors, and regional directors) to formally consult with examination teams and other stakeholders before making substantive decisions about examination findings, including those related to escalation. Although managers generally are required to consult with examiners in charge before making substantial changes to examination findings, FDIC does not require managers to also consult with other stakeholders, including the dedicated or designated examination team reporting to the examiner in charge and specialists in the Large Bank Supervision division. In contrast, OCC and Federal Reserve large bank vetting meetings include managers, examiners, subject-matter experts, and other stakeholders. Several OCC and Federal Reserve examiners we spoke with described the benefits of collaborative work, including the vetting meetings used to reach agreement on examination findings and escalation decisions.

In our interviews, examiners cited examples of changes made to examination reports without the examiners’ knowledge that may indicate threats to the objectivity and independence of the decision-making process. FDIC examiners and examiners in charge at two of the four institutions we selected for examiner interviews described cases where substantial changes or deletions were made to substantive examination findings without their input. Also, one examiner in charge described an instance when certain findings were removed from the examination report without consultation. This examiner in charge did not learn about the changes until seeing the final examination report as it was shared with the institution.

Examiners for another institution noted that managers sometimes but not always consult with them on changes to findings. For example, the examination team cited an instance where management added a violation to the examination report without explanation or supporting evidence in the workpapers.

A process for managers to consult with examination teams and other stakeholders is particularly important for institutions supervised under the Continuous Examination process. These institutions are larger and more complex, and, as FDIC staff explained, examination findings are more specialized. In contrast, institutions supervised through the Point-in-Time Examination process are smaller, less complex, and, according to FDIC staff, examiners-in-charge are typically more involved in all aspects of the examination.

Federal internal control standards state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives.[64] Management should also design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. In addition, in previous work, we identified policies that agencies can use to mitigate threats to independence.[65] One policy includes incorporating layers of review that involve individuals with differing perspectives, incentives, and relationships with industry. Agencies can also promote transparency by documenting the full decision-making process to include divergent views and the rationale or evidence used to resolve them.[66]

OCC and the Federal Reserve have processes for managers to consult with large bank examination teams and other stakeholders before making substantive changes to examination findings. Without a similar documented process, FDIC faces increased risk that decisions related to Continuous Examination process institutions may not be fully independent or grounded in evidence gathered during examinations.

Lack of Rotation Requirements for FDIC Large Bank Case Managers Can Threaten Independence

FDIC officials told us that case managers for Continuous Examination process institutions are not required to rotate assignments after a certain number of years. In contrast, the Federal Reserve and OCC require individuals in similar roles to rotate every 5 years.[67] Officials told us that FDIC does have a 5-year rotation requirement for individuals whose job responsibilities meet certain criteria. In prior work, we reported that FDIC requires examiners in charge to rotate.[68] But, FDIC officials said these criteria do not apply to case managers, who are not subject to this policy.

However, we found that FDIC’s criteria for rotations align with the tasks and interactions of case managers for Continuous Examination process institutions. Specifically, FDIC policy requires rotations for individuals when (1) the primary portion of their tasks involves continuing, broad, and lead responsibility for examining an institution and (2) they are required to interact routinely with financial institution officers and staff and to have on-site presence. According to FDIC procedures, case managers serve as primary points of contact for Continuous Examination process institutions and are responsible for

· ensuring supervisory strategies are appropriate and revised as needed;

· reviewing and analyze reports of examination, applications, investigations, and other correspondence involving the institution;

· developing informal and formal programs to correct deficiencies in the operations and condition of the institution; and

· coordinating all communications with the institution.

While case managers may not meet all of FDIC’s criteria for rotation requirements—specifically, they do not always have an on-site presence—they play a key role in the supervisory process and have important decision-making authority. When case managers are assigned to the same institution for long periods, they risk developing close relationships with institution management, which can threaten their independence and interfere with supervision outcomes.

Additionally, examiners and examiners in charge from two selected institutions described instances of case managers exhibiting biased behavior, including informal meetings between case managers and institutions that may not have been appropriate. As previously discussed, several examiners also described instances where managers overrode examiner assessments of an institution’s condition without consulting with examinations teams or providing adequate support.

In 2019, FDIC identified regulatory capture as a risk through its risk identification process.[69] Federal internal control standards state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives.[70] Management should also design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. In addition, in previous work, we identified policies that agencies can use to mitigate threats to independence.[71] In particular, we found that agencies can mitigate threats to independence by implementing policies that require staff in key decision-making roles to rotate, so as to mitigate the impact of any one employee.

As noted earlier, FDIC has rotation policies in place for examiners in charge. Rotation requirements for Continuous Examination process case managers could also help ensure they maintain their supervisory independence.

Conclusions

The March 2023 bank failures raised questions about the regulators’ ability to escalate safety and soundness concerns, such as weak corporate governance and risk management practices, before they materially affect a bank’s financial condition. We identified several issues that could affect the Federal Reserve’s and FDIC’s ability to escalate concerns effectively:

· The Federal Reserve’s lack of specific regulation or enforceable guidelines to escalate supervisory concerns about corporate governance and risk management may hinder its ability to take early, forceful regulatory action against unsafe banking practices before they compromise an institution’s capital.

· Congress recognized the importance of early intervention in financial institution supervision when it enacted the Dodd-Frank Act’s section 166, which requires the Federal Reserve to develop early remediation standards for large bank holding companies. However, more than 14 years later, the Federal Reserve has yet to issue a regulation fully implementing section 166. By doing so, it would help lessen the risk of insolvency among certain financial institutions, thereby protecting financial stability.

· FDIC does not centrally track supervisory recommendations, which are common and can help the agency detect key issues early, as it does matters requiring board attention. Central tracking of supervisory recommendations could help management identify emerging risks earlier across all supervised institutions.

· By implementing procedures for managers—including case managers, assistant regional directors, and regional directors—to consult with the entire Continuous Examination process examination team and relevant stakeholders before making substantive changes to examination findings, FDIC could better ensure its escalation decisions are independent and grounded in the evidence gathered during examinations.

· Rotation requirements for Continuous Examination process case managers after a certain number of years could help FDIC prevent regulatory capture and ensure that case managers for Continuous Examination process institutions maintain their supervisory independence.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following five recommendations, including two to the Federal Reserve and three to FDIC:

· The Chair of the Federal Reserve should determine whether to promulgate a regulation or enforceable guidelines on corporate governance and risk management under section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, consistent with those issued by the other regulators, and document steps taken to make this determination. (Recommendation 1)

· The Chair of the Federal Reserve should issue a regulation to implement remaining open portions of section 166 of the Dodd-Frank Act, taking into account prior proposals and public comments. (Recommendation 2)

· The Chair of FDIC should develop a central database for recording and reporting supervisory recommendations, similar to that used for matters requiring board attention. (Recommendation 3)

· The Chair of FDIC should establish procedures, such as vetting meetings, for the Continuous Examination process program to ensure that managers formally consult with the examination team and relevant stakeholders before making substantive changes to examination findings. Such vetting meetings should be documented and include any divergent views that arise. (Recommendation 4)

· The Chair of FDIC should consider a requirement that case managers for Continuous Examination process institutions periodically rotate assignments. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to OCC, the Federal Reserve, and FDIC for review and comment. The Federal Reserve and FDIC provided written comments, which are provided in appendix IV and V, respectively. OCC, the Federal Reserve, and FDIC provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In its comments, the Federal Reserve neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendations. The Federal Reserve said it recognizes the importance of using available supervisory tools to require firms to timely and fully remediate issues identified through the supervisory process that may pose a threat to an institution’s safety and soundness. The Federal Reserve also said it has been modifying supervisory processes so that once material issues are identified, they are addressed more quickly by both bankers and supervisors.

Regarding the first recommendation, the Federal Reserve stated that it will evaluate its existing applicable standards and expectations to determine the appropriateness of promulgating a new regulation or enforceable guidelines on corporate governance and risk management at state member banks and holding companies.

Regarding the second recommendation, the Federal Reserve stated that it will continue to consider how to address any residual elements of section 166 of the Dodd-Frank Act in a manner consistent with the statutory language and without creating unintended consequences.

In its comments, FDIC expressed concern that some findings in the draft report appeared to be based solely on interviews with individual examiners and did not appear to consider the views of others or supporting documentation for context. We conducted the interviews to obtain examiner perspectives on escalation of supervisory concerns. In light of concerns raised in a report commissioned by FDIC’s Board of Directors on allegations of sexual harassment and interpersonal misconduct at FDIC, as well as concerns about retaliation expressed by examiners-in-charge and examiners we interviewed, we agreed to provide anonymity to encourage open and honest discussion on escalation practices.[72] Therefore, we did not disclose to FDIC management the specific details shared during these interviews. However, after the interviews, we met with FDIC management to ask questions related to what we heard and later sent follow-up written questions seeking further clarification.

FDIC agreed with our first recommendation to centrally track supervisory recommendations and will explore interim technology solutions for doing so.

FDIC generally agreed with our second recommendation to formally consult with the entire examination team and relevant stakeholders before making substantive changes to examination findings. On the basis of FDIC’s comments, we revised our recommendation to include only the Continuous Examination process. We made this revision in recognition of the large volume and small size of institutions in the Point-in-Time Examination process, and we note that institutions under the Continuous Examination process are more comparable to those institutions supervised by OCC and the Federal Reserve, which also employ such vetting meetings.