VA VET CENTERS

Opportunities Exist to Improve Asset Management and Identification of Future Counseling Locations

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106781

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106781. For more information, contact David Marroni at (202) 512-2834 or marronid@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106781, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

VA VET CENTERS

Opportunities Exist to Improve Asset Management and Identification of Future Counseling Locations

Why GAO Did This Study

VHA’s 303 Vet Centers provide counseling services to eligible veterans, servicemembers, and their families who are experiencing challenges from readjusting to civilian life or continuing military service.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to review the physical infrastructure of Vet Centers. This report examines 1) how VHA monitors the physical condition of its facilities; 2) the extent to which VHA’s processes align with key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework; and 3) the extent to which VHA’s model for assessing future location needs aligns with selected practices and standards, among other topics.

GAO analyzed RCS data on leasing and inspections and its demand model. GAO visited three Vet Centers selected based on factors including location and recent inspection results. GAO reviewed documents and interviewed RCS officials to determine the extent to which RCS’s processes align with key asset management characteristics, actuarial practices, and internal control standards. GAO also interviewed a non-generalizable sample of Vet Center directors and regional officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making eight recommendations to VHA to improve its asset management processes, and ensure its modeling processes more fully follow actuarial practices and internal control standards. The Department of Veterans Affairs concurred with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) leases facilities to provide counseling at over 300 Vet Centers and satellite locations. RCS monitors the physical condition of these facilities through annual inspections. RCS’s inspection process identified physical condition issues at 13 percent of Vet Centers in fiscal year 2023, according to GAO’s analysis of RCS data. RCS addresses such issues and improves Vet Centers through projects ranging from replacing furniture to expanding space.

RCS’s processes fully align with two of the six key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework, and partially align with four (see table). For example, RCS maintains leadership support and a collaborative organizational culture around asset management. However, developing an asset management plan and refining policies could help RCS ensure its assets support its mission, prioritize improvements to Vet Centers, and collect better inspection data. Also, better evaluation of asset management practices could help RCS ensure that these processes help RCS meet its counseling mission.

Alignment of Readjustment Counseling Service’s Asset Management Processes with Key Characteristics of GAO’s Asset Management Framework

|

Characteristic |

RCS processes |

Alignment |

|

Leadership support |

RCS leadership supports asset management and provides necessary resources. |

Fully aligns |

|

Collaborative organizational culture |

RCS promotes a culture of information sharing regarding their assets. |

Fully aligns |

|

Establishing policies and plans |

RCS has some policies related to asset management but does not have a strategic asset management plan that ties to its mission. |

Partially aligns |

|

Maximizing asset value |

RCS has some policies that consider mission need when identifying new locations but does not have policies for prioritizing improvements. |

Partially aligns |

|

Using quality data |

RCS collects some data on leasing and improvements but does not consistently collect quality inspection data. |

Partially aligns |

|

Evaluating asset management |

RCS evaluates some aspects of its inspection process but does not fully evaluate the performance of its asset management practices. |

Partially aligns |

Source: GAO analysis of Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) information and GAO 19-57 | GAO-25-106781.

RCS recently worked with VHA’s actuarial contractor to develop a model to project demand for counseling and identify where to locate future Vet Centers to meet veterans’ needs. GAO found that RCS’s processes for developing the model do not fully align with three of eight actuarial practices and internal control standards in four areas. Specifically, 1) RCS does not document how it validates the data it provides the contractor, and does not require the contractor to provide documentation of 2) all its external data assumptions and 3) model validation, or 4) information on model uncertainty. By better aligning its modeling processes with actuarial practices and internal control standards, RCS could ensure it understands how to best use the model to identify future Vet Center locations.

Abbreviations

|

ASOP |

actuarial standards of practice |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

RCS |

Readjustment Counseling Services |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

VHA |

Veterans Health Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 13, 2024

The Honorable Jon Tester

Chairman

The Honorable Jerry Moran

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Bost

Chairman

The Honorable Mark Takano

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

House of Representatives

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) estimates that each year about 200,000 servicemembers make the transition from the military to civilian life. Many readjust without major difficulties, but it is essential to help veterans and servicemembers overcome challenges that can be related to this transition or continued military service—such as mental and physical health issues. Furthermore, according to VA, recent transition from military service to civilian life is a risk factor for suicide.[1]

Although the Department of Defense has a role in assisting servicemembers with preparing for their transition, it is primarily VA’s role to assist veterans after they separate from the military and begin readjusting to civilian life. VA also assists servicemembers facing challenges with continued military service. Congress established Vet Centers as part of VA’s Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in 1979 to provide readjustment counseling for veterans, when a significant number of Vietnam-era veterans were experiencing readjustment problems.[2] Eligibility was originally limited to veterans who served on active duty during the Vietnam era but has subsequently been expanded and now includes veterans and servicemembers who have served in any combat theater or area of hostility.[3]

VHA’s goal is to provide timely and accessible readjustment counseling services, by ensuring there are sufficient Vet Centers and outstations in place to meet the needs of veterans, service members, and their families.[4] The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for us to review the physical infrastructure of Vet Centers and planned future investments.[5] Specifically, this report examines: (1) how VHA obtains and improves space for Vet Centers and outstations, (2) how VHA monitors the physical condition of Vet Centers and outstations, (3) the extent to which VHA’s asset management processes for Vet Centers align with key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework, and (4) the extent to which VHA’s modeling processes for assessing future Vet Center location needs follow selected actuarial practices and internal control standards.

To address all our objectives, we reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from VHA’s Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) —the office that oversees Vet Centers. We also interviewed district officials from each of RCS’s five regional districts and Vet Center directors from five selected Vet Centers.[6] We selected one Vet Center from each district and considered other factors including the presence of an outstation location. Information obtained from our interviews with these officials is not generalizable but provides useful information on VHA’s processes.

To describe how VHA obtains and improves space for Vet Centers and outstations, we analyzed RCS data for fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023 on the number of Vet Center leases, length of the leasing process, number of improvements made to Vet Center space, and cost of those improvements. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed RCS documentation, conducted electronic and manual testing of the data, and interviewed RCS officials responsible for maintaining the data. We found the data sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing RCS’s leasing and improvement activity from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023.

To describe how VHA monitors the physical condition of Vet Centers and outstations, we requested and reviewed data on annual Vet Center inspections, including the date and results of these inspections. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed RCS documentation, conducted electronic and manual testing of the data, and interviewed RCS officials responsible for maintaining the data. We found the data sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing the physical condition of Vet Centers. We also visited and observed conditions at three Vet Centers—Washington, D.C.; Lakeland, Florida; and New Orleans, Louisiana—out of the five we selected for our review. We documented our observations using an analyst data entry form and compared the condition of these Vet Centers against the most recent annual inspection reports.

To examine the extent to which VHA’s asset management processes for Vet Centers align with six key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework, we compared RCS’s documented processes to obtain space for Vet Centers and outstations, improve that space, and monitor its condition to key characteristics of an effective asset management framework.[7]

To examine the extent to which VHA’s modeling processes for assessing future Vet Center location needs follow selected actuarial practices and internal control standards, we reviewed documentation from RCS and VHA’s actuarial contractor on the data, actuarial assumptions, and methods used to develop a demand projection model that assesses future demand for Vet Center locations. We also reviewed RCS documents about the actuarial assumptions and methods used to develop the 10-year projection of future counseling service demand. Further, we compared the process of the demand modeling against eight actuarial standards of practice.[8] We also compared these processes against three federal standards for internal control related to using and communicating quality information and responding to risk.[9] We also interviewed representatives from VHA’s actuarial contractor.

Additional information about our scope and methodology is described in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Vet Center Services and Locations

The purpose of VHA’s Vet Centers is to help eligible veterans, servicemembers, and their families experiencing challenges from deployment, combat, or other military-related trauma with readjustment to civilian life or continued military service through readjustment counseling services. Vet Centers are community based and their services and structure are separate from health care provided at VHA medical facilities. According to VHA, Vet Centers are designed to be welcoming and promote access to counseling services and support in a non-institutional setting.[10]

Readjustment counseling includes a range of services, such as counseling for post-traumatic stress disorder and military sexual trauma, and is provided through individual, group, couples, and family counseling visits.[11] Veterans and active servicemembers who have a qualifying military-related experience are eligible for Vet Center services, and authorized services for their family members, at no cost to them.[12]

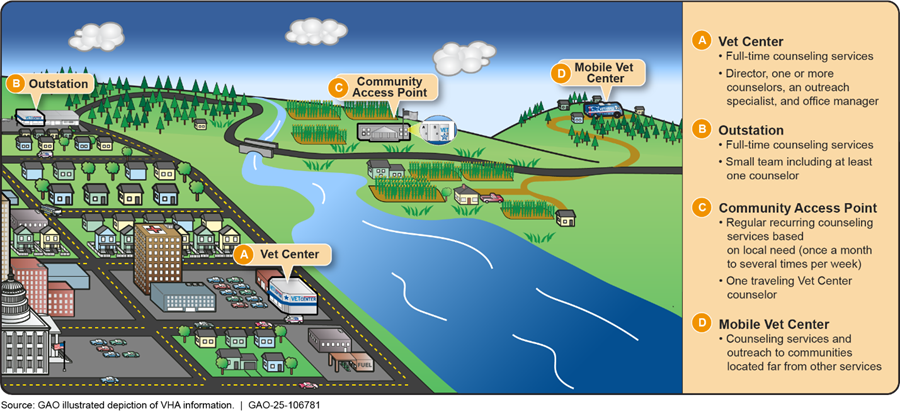

In fiscal year 2024, there were 303 Vet Centers located across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and Guam. Vet Center staff also provide services at satellite locations, including 22 outstations and hundreds of community access points located in donated spaces, such as at community centers or on college campuses (see fig. 1). In addition, RCS maintains a fleet of 88 Mobile Vet Centers, which are vehicles that Vet Center staff operate to provide outreach and counseling in the community.[13]

Figure 1: Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Readjustment Counseling Service Locations Providing Counseling Services

RCS and Vet Center Organizational Structure

RCS is the office within VHA that oversees Vet Centers. The Chief Readjustment Counseling Officer of RCS reports directly to VA’s Under Secretary for Health and maintains “direct line authority over all RCS staff.”[14] Vet Centers are organized into five regional districts, each led by a district director. Each of the five district directors (hereinafter referred to as “district leadership”) oversees the implementation of VA and VHA policies for RCS in their respective districts. Deputy district directors are responsible for supervising clinical and administrative staff at each of the Vet Centers within their district. Deputy district directors (hereinafter referred to as “district officials”) also oversee operational tasks, such as leasing office space, and conducting inspections of Vet Centers. Each Vet Center is managed by a Vet Center director, who is responsible for the day-to-day oversight of the Vet Center’s staff.

VHA Leases Its Vet Centers and Outstations and Improves Space Based on Needs Identified by Local Officials

VHA Works with Local Officials and Its Contracting Offices to Lease Vet Centers and Outstations

VHA’s RCS leases its Vet Centers and outstations using a process that relies on local officials (district officials and Vet Center directors) and its own contracting offices. According to RCS, it leases, rather than owns, the space it uses to provide counseling services for multiple reasons, including avoiding the costs and time required to acquire land and construct the space.

RCS primarily awards two types of leases for existing Vet Centers and outstations: (1) new leases for existing Vet Centers or outstations relocating to a new space, and (2) renewals of current leases. RCS may also award a new lease when adding a Vet Center or outstation to a geographic location where one did not previously exist.[15] We found that RCS awarded 139 leases from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023. This includes 69 lease renewals, 66 leases for Vet Centers or outstations relocating to a new space, and four leases for new outstation locations.

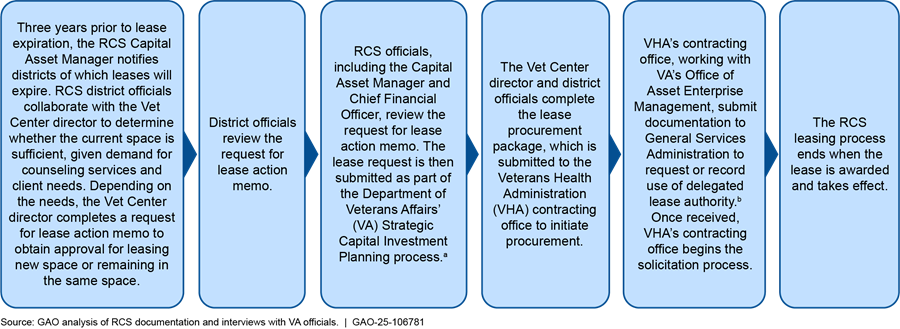

Our review of RCS documentation and interviews with VA officials identified the steps in RCS’s typical leasing process for existing Vet Centers, which begins about 3 years prior to the expiration of the current lease (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Veterans Health Administration Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Typical Leasing Process for Existing Vet Centers and Outstations

aThe Strategic Capital Investment Planning process is VA’s main mechanism for identifying and prioritizing capital-planning projects. The intent of the process is to identify the capital required to meet VA’s service and space needs and to ensure that all project requests are centrally reviewed in an equitable and consistent way throughout the system. The lease must be approved through this process before procurement.

bFederal agencies can apply to the General Services Administration for conditional delegations of leasing authority to procure space. VHA also makes use of the categorical delegation of lease authority under 41 C.F.R. 102-73.155(h).

RCS relies on local officials to determine their space needs—including whether they should relocate or remain in their existing space when a lease is up for renewal. When evaluating their space needs, local officials consider factors including facility security, location, number of clients, and the sufficiency of their existing space.[16] The Vet Center director documents the space needs in a request for lease action memo, as described in figure 2 above.

RCS relies on VHA contracting offices for assistance with the procurement process. For example, the contracting offices assist with obtaining the required delegation of authority from the General Services Administration (GSA) for each new lease and lease renewal.[17] According to RCS officials, they must obtain or record this delegation of authority for each new lease and lease renewal before the solicitation process starts.

VHA Relies on Local Officials to Identify Needed Improvements to Vet Centers and Outstations

VHA’s RCS relies on local officials to identify when improvements to Vet Center space are needed. These officials may identify improvements as part of the required annual inspection process (described in more detail later in this report), through ongoing monitoring of Vet Center space, or when determining whether to renew an existing lease or relocate to a new space, as described above. Improvement projects range from straightforward tasks like replacing worn or dated furniture to more extensive efforts like building out space in new or existing Vet Centers to accommodate private offices (see table 1). We found that RCS awarded 178 improvement projects from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023. These improvement projects totaled approximately $69 million, according to RCS information.[18]

|

Vet Center Location |

Fiscal Year Awarded |

Cost |

Description |

|

Des Moines, IA |

2023 |

$514,326 |

Space expanded to accommodate family counseling sessions and additional office space. Improvements include new interior flooring and wall coverings, accessible restrooms, and a security system. |

|

Greenville, NC |

2021 |

$547,500 |

Space buildout to accommodate new Vet Center location. Lobby, reception area, office spaces, and counseling rooms constructed. Improvements include access-controlled doors, accessible restrooms, new flooring and paint, and electrical work. |

|

Danbury, CT |

2022 |

$169,380 |

All furniture replaced. |

|

Watertown, NY |

2021 |

$176,673 |

All furniture replaced. |

Source: GAO analysis of Readjustment Counseling Service information. | GAO‑25‑106781

Note: This is not an exhaustive list of improvements made at the Des Moines and Greenville Vet Centers.

RCS officials told us they collaborate with other VA offices to make improvements to Vet Center space. For example, they said that to purchase furniture, RCS shares design information with VA’s Strategic Acquisition Center, which solicits for and awards the contract.[19] In addition, RCS works with VA’s Technology Acquisition Center to acquire some information technology office equipment.[20] RCS officials also told us they rely on VA subject matter experts in engineering, security, and information technology when building out new or existing Vet Center space to meet their needs. For example, they said that VA’s Office of Information and Technology often works to bring technical and acquisitions expertise to Vet Centers.

VHA Monitors the Physical Condition of Vet Centers and Outstations through Annual Inspections

Annual Inspection Process

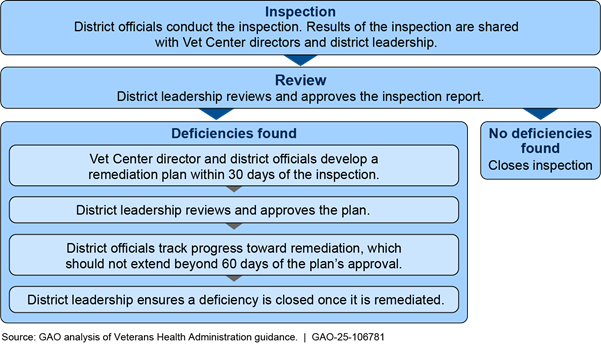

VHA’s RCS uses its annual inspection process to identify deficiencies in the physical condition of its Vet Centers and outstations.[21] These required inspections are intended to ensure compliance with VHA policies and procedures and include an assessment of the building and interior space in which counseling services are offered.[22] RCS inspected each of its 300 Vet Centers annually from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2023.[23]

District officials are responsible for annually inspecting each Vet Center in their district. Annual inspections can occur either in-person or virtually, but VHA policy requires RCS to conduct an in-person inspection at least every other year.[24] As described in figure 3 below, once a district official completes the inspection, the inspection report is shared with the Vet Center director and district leadership. If a deficiency is identified, district officials work with the Vet Center director to develop a remediation plan and track progress toward resolving the issue. Once the remediation plan is approved, all deficiencies are to be remediated within 60 days.[25]

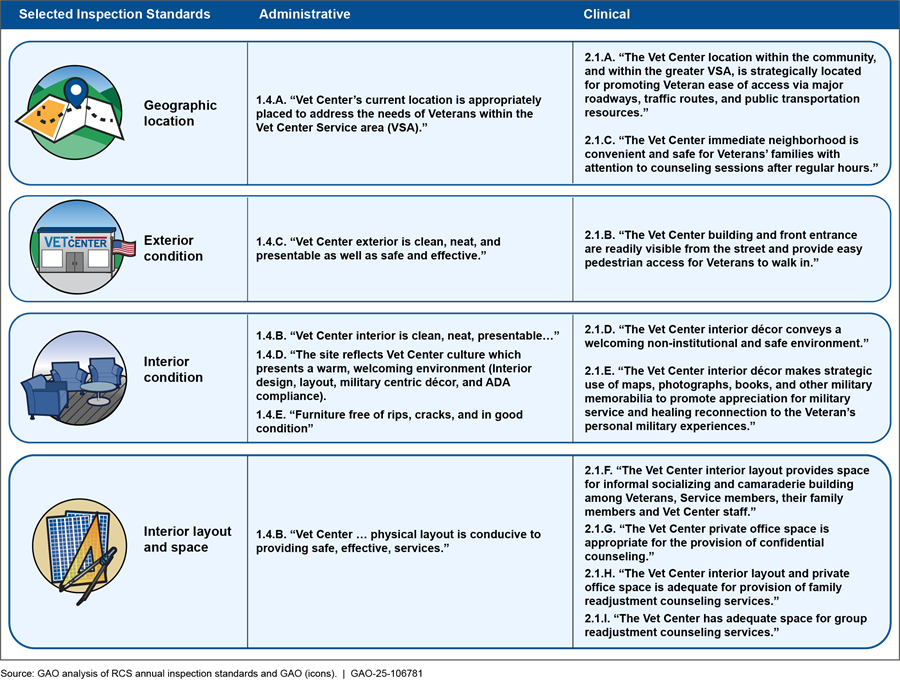

Standards for Vet Centers’ Physical Condition

District officials conduct inspections using two separate sets of standards—administrative standards and clinical standards.[26] These standards cover areas such as outreach activities, case management procedures, fiscal management, and privacy, as well as standards that directly assess the physical condition of Vet Center facilities. Our analysis of RCS’s annual inspection standards found 14 standards related to the Vet Center’s physical condition (hereinafter referred to as “selected standards”), which are shown in figure 4.[27] Officials rate the Vet Center’s compliance with each standard by indicating if the Vet Center has met, not met, or, in some cases, needs improvement. In addition, officials may include comments to describe how the Vet Center complied with a specific standard or provide more information about any deficiencies identified.

Figure 4: Selected Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Annual Inspection Standards Related to the Physical Condition of Vet Centers

Types of Deficiencies Identified

From fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023, RCS identified 484 deficiencies related to the selected standards described in figure 4.[28] Based on our review of Vet Center inspection results, our observations at selected Vet Centers, and interviews with RCS officials, we found variety in the scale and scope of the deficiencies identified. Examples:

Geographic location. Deficiencies in this category were often related to concerns regarding crime and safety.[29] For example, officials from a Vet Center in California told us an increase in crime has made the neighborhood around the Vet Center unsafe, which Vet Center staff attributed to a recently opened marijuana dispensary.

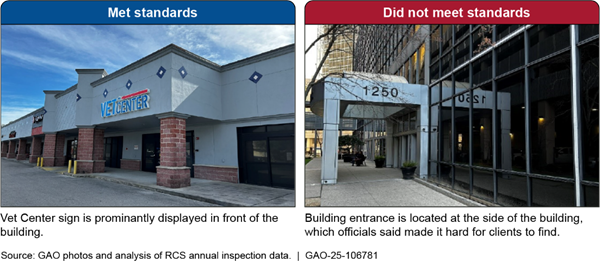

Exterior condition. Deficiencies in this category were often related to inadequate parking, signage, disability access, or exterior wear and tear. For example, district officials told us accessing a Vet Center in Hawaii required crossing through a fitness center to use a wheelchair lift that is sometimes out of service, making access challenging for veterans with disabilities. Figure 5 shows examples of exteriors we observed at two Vet Centers we visited.

Figure 5: Examples of Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Inspection Findings Related to Exterior Condition

Note: During the 2019 and 2020 annual inspections, the Vet Center on the right did not meet the standard, “the building, and front entrance are readily visible from the street and provide easy pedestrian access for veterans to walk in.”

Interior condition. Deficiencies in this category were often related to interior décor, cleanliness, and general wear and tear of the interior and furnishings. For example, district officials told us at one facility in Wisconsin, mold was discovered requiring the facility to provide services remotely while awaiting abatement. Figure 6 shows examples of two interiors we observed at Vet Centers we visited.

Figure 6: Examples of Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Inspection Findings Related to Interior Condition

Interior layout. Deficiencies in this category were often related to insufficient space for socialization and individual group and family counseling services, as well as the privacy of the space. For example, at one facility in New York, staff reported insufficient space for both group and individual counseling. Figure 7 shows examples of two counseling rooms at Vet Centers we visited.

Figure 7: Examples of Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) Inspection Findings Related to Interior Layout

Our analysis of RCS annual inspection data for fiscal year 2023 found that 13 percent of Vet Centers had a deficiency in at least one of the selected standards described above.[30] Table 2 shows the number and percentage of Vet Centers with deficiencies in these standards by type in fiscal year 2023.

Table 2: Type and Number of Deficiencies Related to the Physical Condition of Vet Centers – Fiscal Year 2023

|

Deficiency type |

Number of deficiencies |

Number of Vet Centers with this type of deficiency |

Percentage of all Vet Centers with this type of deficiency |

|

Geographic location |

12 |

9 |

3% |

|

Exterior condition |

14 |

14 |

5% |

|

Interior condition |

18 |

16 |

5% |

|

Interior layout and space* |

27 |

20 |

7% |

|

Total |

71 |

39a |

13% |

Source: GAO analysis of Readjustment Counseling Service annual inspection data. | GAO‑25‑106781

Notes: Some interior layout and space deficiencies found during inspection may include interior condition issues. At the time of the 2023 inspection, there were 300 Vet Centers. Inspection results for outstations are included in the report for the Vet Center to which the outstation is attached.

aSome Vet Centers had deficiencies across multiple categories but were only counted once. As a result, the total does not equal the sum of the rows above.

Efforts to Remediate Deficiencies

According to RCS officials, they typically fix deficiencies by using the improvement or leasing processes previously described. Examples of these remediations include:

Improvement projects. RCS provided examples of Vet Center directors replacing furniture, carpet, or paint or purchasing new signage or artwork to address deficiencies. For example, the 2023 annual inspection of one Florida Vet Center found torn furniture. Subsequently, the Vet Center director worked with district officials and RCS headquarters to replace the furniture. RCS officials told us that they may also undertake more involved projects, such as improving accessibility for clients with disabilities or working with the landlord to build out additional space.

Leasing. RCS provided examples of Vet Center directors, in coordination with district officials, determining that relocation is the best option to remediate a deficiency. This may occur if the lessor is not cooperative with RCS requests to improve space; the Vet Center is poorly located with respect to crime, parking, or proximity to clients; or the space no longer meets RCS needs. For example, the 2020 annual inspection found one Illinois Vet Center had insufficient space for group sessions. Subsequently, that facility moved to a new larger location.

As discussed in more detail in the next section of the report, we were unable to determine the extent and timeliness by which deficiencies were remediated due to inconsistencies in how RCS tracks how and when an issue is resolved.

VHA’s Processes for Vet Centers Align with Some but Not All Key Characteristics of GAO’s Asset Management Framework

We have previously identified six key characteristics of an asset management framework that can help federal agencies manage their assets and resources effectively. Our review found that VHA’s processes to lease and improve space and monitor the physical condition of its Vet Centers and outstations fully align with two of the six key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework, and partially align with four key characteristics (see table 3 and further explanation below).[31]

Table 3: Alignment of Readjustment Counseling Service Asset Management Processes with Key Asset Management Characteristics

|

Characteristic |

Description |

Alignment |

|

Maintaining leadership support |

Organizational leadership should clearly articulate its support for asset management and provide the necessary resources for asset management to succeed. |

● |

|

Promoting a collaborative organizational culture |

Organizations should promote a culture of information sharing and enterprise-wide decision-making regarding their assets. |

● |

|

Establishing formal policies and plans |

Organizations should have a clearly defined governance regime that includes a strategic asset management plan that ties to the organization’s mission and strategic objectives, defines the asset management scope, and defines the roles and responsibilities for each part of the organization. |

◐ |

|

Maximizing an asset portfolio’s value |

Organizations should develop an asset management policy to identify the value of their assets to achieving their mission and strategic objectives and invest in those assets in such as a way as to derive the greatest value from them. |

◐ |

|

Using quality data |

Organizations should collect, analyze, and verify the accuracy of asset data, including the organization’s inventory of assets and data on each asset’s condition, age, maintenance cost, and criticality to the organization. |

◐ |

|

Evaluating and improving asset management practices |

Organizations should evaluate the performance of their asset management system and implement necessary improvements. |

◐ |

Legend: ● Fully Aligns with key asset management characteristics

◐ Partially aligns with key asset management characteristics

Sources: GAO analysis of Readjustment Counseling Service information and GAO‑19‑57. | GAO‑25‑106781

Note: We used a three-tier system to assess whether RCS’s

asset management processes aligned with key asset management characteristics:

Fully Aligns, Partially Aligns, and Does Not Align. We determined that RCS’s

processes aligned with a key characteristic when we saw evidence that RCS

followed all aspects of the characteristic. We determined that the processes

partially aligned with a characteristic when RCS followed some, but not all,

aspects of the characteristic. We determined that all of RCS’s asset management

processes either partially or fully aligned with key asset management

characteristics.

Maintaining Leadership Support

RCS’s processes fully align with this characteristic because RCS leadership provides the necessary resources for its asset management processes to succeed. Most district officials told us RCS provides sufficient funding to lease and make improvements to Vet Centers. In addition, in 2016 RCS hired a Capital Asset Manager who developed tools and guidance to streamline and improve processes, including the process to lease space. For example, the Capital Asset Manager created templates to help Vet Center directors assess their space needs and a catalog of approved furniture so officials can make selections without needing interior design expertise. Three Vet Center directors we interviewed said the guidance and support was useful.

RCS leadership also provides the necessary resources and support for its annual inspection process. For example, VHA policy requires district officials to support Vet Center directors in remediating deficiencies identified during the inspection process. In addition, RCS leadership developed an RCS working group to improve guidance for the annual inspection process. Vet Center directors we spoke to reported that they felt supported by RCS leadership through the inspection process, had access to knowledge and resources on how to remediate deficiencies, and successfully remediated deficiencies with the support of district officials.

Promoting a Collaborative Organizational Culture

RCS’s processes fully align with this characteristic because RCS shares information across VA and VHA to support decisions about leasing, improving, and inspecting Vet Centers and outstations. As described previously, RCS relies on local officials to identify space needs. RCS leadership told us they hold monthly calls with district officials and each of VHA’s 18 network contracting officers to discuss the status of current leases and leasing needs. RCS also shares information with and relies on IT and security experts across VA to support decisions about space improvements. Further, Vet Center directors told us they regularly communicate with district officials about inspection results and collaborate with these officials and RCS headquarters staff to remediate deficiencies. Finally, the RCS working group mentioned above includes stakeholders from across leadership, districts, and Vet Centers working to improve guidance for the annual inspection process.

Establishing Formal Policies and Plans

RCS’s processes partially align with this characteristic. RCS maintains some formal policies, plans, and processes to guide its asset management. For example, VHA directives identify RCS’s governance regime and the roles and responsibilities within RCS related to leasing, improving, and inspecting Vet Center space.[32] In addition, RCS’s long-range plan also includes an asset management objective that emphasizes the importance of using data to predict demand and inform decisions regarding the location of new Vet Centers.[33]

However, RCS has not developed a strategic asset management plan that describes how it intends to use its Vet Centers and outstations and its related asset management activities (including decisions regarding leasing and improvements) to support RCS’s mission and strategic objectives. While RCS collects and reviews some information on an individual asset basis, RCS would benefit from an overarching view across its assets.

RCS officials told us that their efforts to determine which leases to include in VA’s Strategic Capital Investment Planning process fulfill the intent of a strategic asset management plan.[34] Specifically, they noted that they use the request for lease action memos submitted by RCS’s districts to determine which leases to include in their Strategic Capital Investment Planning submission. As previously noted, the memos contain information on how the Vet Center or outstation affects RCS’s mission, including the facility’s location relative to the veteran population, accessibility, and number of clients served.

Although the Strategic Capital Investment Planning may be a useful planning mechanism for VA, this process does not constitute a formal asset management plan for RCS. We have previously reported that other agencies’ asset management plans and policies include elements that help the agencies take a more strategic approach to decision-making. For example, such plans and policies include information on the overarching objectives of an agency’s asset management approach, as well as how an agency collects data, prioritizes assets, and makes investment decisions.[35]

Without a formal asset management plan, it may be challenging for RCS to ensure it is managing its assets such that they support RCS’s strategic objectives and its mission to provide counseling services to veterans and their families. Such a plan could help RCS evaluate the performance of its asset management process in meeting strategic objectives and implementing needed changes. For example, by monitoring whether deficiencies are remediated in accordance with required time frames, RCS could better ensure its annual inspection process accurately reflects the physical condition of its Vet Centers and outstations.

Maximizing Asset Portfolio’s Value

RCS’s processes also partially align with this characteristic. RCS has some policies to prioritize investments in Vet Centers and outstations, which may help it better target resources toward assets that will provide the greatest value to the agency in meeting its mission and strategic objectives. For example, when determining where to locate new Vet Centers, RCS uses a demand model to identify the specific geographic areas where there is unmet demand for counseling services.[36]

However, RCS does not have a policy to prioritize improvements to its existing Vet Centers and outstations based on specific criteria such as asset condition and costs. RCS officials told us they have not developed guidance to prioritize improvements to Vet Center space because they have always been provided with sufficient funding.

RCS may not always have sufficient funding to make all requested improvements to Vet Centers. We have repeatedly reported on the fiscal challenges facing the federal government and the continued increase in the budget deficit.[37] Additionally, both the VA’s resource allocation processes and the federal government’s efforts to manage real property are included on our High-Risk list.[38] In the future, agencies may face constraints which may reduce flexibility in how funds are allocated.

Having a policy in place with specific criteria on how to prioritize improvements would allow RCS to target resources toward the Vet Centers and outstations that provide the greatest value to RCS in meeting its mission of providing counseling services to veterans and their families. For example, RCS officials told us they would prioritize improvements that affect client safety over cosmetic issues like dated furniture. Additionally, clear prioritization could help in resolving any disagreements and ensuring consistency of resource allocation decisions across RCS.

Using Quality Data

RCS’s processes partially align with this characteristic because RCS collects and analyzes information on Vet Center leases, improvements, and inspections, but it has not consistently collected quality inspection data. For example, RCS has an internal system to track lease expiration dates and the costs associated with both annual rent and improvement projects. According to RCS officials, this information is verified for accuracy and used to make leasing decisions. RCS also collects information in each request for lease action memo about a Vet Center’s surrounding population and the total number of unique clients served—information important for RCS’s mission. With respect to inspections, RCS officials told us they collect and store inspection data (such as the inspection results and the date of remediation) in RCS’s data systems, and then district leadership reviews this information to ensure the data are properly collected and verified.

However, our review of RCS inspection data and interviews with district officials found instances in which officials were inconsistent in how they applied inspection standards and recorded when a deficiency was remediated. For example, when conducting the clinical inspection of an Ohio Vet Center, one district official identified a deficiency with the exterior. However, when conducting the separate administrative inspection, another district official did not identify the same issue despite both inspections including an exterior assessment. In another example, we found RCS identified the same deficiency with the exterior condition of a Connecticut Vet Center each year between 2019 and 2022, despite its being marked each year as remediated.

RCS officials told us they do not provide guidance on several aspects of the annual inspection process. Specifically, RCS does not provide guidance about:

· How to apply the inspection standards, which are often subjective. For example, one standard includes that furniture should be “in good condition” but does not further define this standard.

· How to select a rating from the three-point scale (“met,” “needs improvement,” “not met”) used to rate compliance with each standard. For example, there is no guidance to differentiate between when a standard should be assigned “not met” versus “needs improvement.”

· How to address overlapping inspection standards. For example, both the clinical and administrative standards include evaluating whether the Vet Center interior is sufficiently welcoming and makes use of military-centric décor.

· How and when officials should record that a deficiency is remediated.

RCS officials told us that RCS developed a working group in February 2024 to improve guidance related to its annual inspection process. This working group is reviewing the process and standards to provide additional clarity and guidance, and address overlap, among other things. As of August 2024, RCS officials told us that they reviewed the inspection standards, identified overlap between them, and made recommendations about how to apply the standards to reduce subjectivity. RCS officials told us they anticipate piloting new inspection standards in fiscal year 2025.

It will be important for RCS to follow through on this effort to ensure it is collecting quality data about the physical condition of Vet Centers and outstations. Subjective standards can create situations in which district officials inconsistently apply standards during inspections. Further, without guidance about how and when remediations should be recorded, RCS may be unaware of the status of deficiency resolution.

Evaluating and Improving Asset Management Practices

RCS’s processes partially align with this characteristic. Specifically, RCS recently assembled a working group to evaluate and improve certain aspects of the inspection process but has not taken steps to fully evaluate its asset management processes and implement improvements. Specifically, RCS does not collect information needed to assess how well its lease process is working or whether aspects of the process need to be improved. For example, RCS does not track how long it takes to complete each lease. Similarly, RCS does not track some key indicators of compliance with its annual inspection process, including those related to remediating deficiencies. For example, RCS officials told us they do not monitor whether Vet Centers are inspected in person with the required frequency.

RCS officials told us that, following a reorganization in 2017, they identified gaps in planning, oversight, and process improvement, and hired new staff to serve in oversight roles. RCS officials acknowledged that they should monitor whether an inspection occurred in person as an indicator for the inspection process. However, as noted above, we found that they are not monitoring such an indicator. These officials also said they do not need to track whether a lease is in extension or holdover because they would be aware of each lease’s status through communication with contracting offices.[39] However, RCS officials told us they did not know of the total number of leases that were currently in an extension as of April 2024.

Without evaluating the performance of its asset management process and implementing needed changes, RCS cannot ensure these processes are helping it to meet its objectives. For example, we found instances where RCS could identify potential areas for improvement by evaluating its asset management processes and procedures:

Lease time frame. At least 58 out of 139 leases completed between fiscal years 2019 and fiscal year 2023 exceeded the 3-year time frame for awarding a lease.[40] RCS officials told us lease extensions may be used if additional time is needed to find an appropriate location or there are long lead times for procurement. However, we were not able to determine if the leases that exceeded the 3-year time frame were extended or went into holdover status because RCS does not track that information. General Services Administration guidance, which the VA follows, indicates that lease extensions should not be routinely used, and holdovers should be avoided.[41]

In-person inspections. RCS has not met its requirement to conduct in-person inspections at least every other year. Twenty-four Vet Centers did not receive an in-person inspection in either 2022 or 2023. RCS officials reported that they had not been tracking this compliance measure due to staffing challenges.

Remediation dates. Over half of annual inspections from fiscal years 2019 through fiscal year 2023 with deficiencies were (1) reported as not remediated within the 60-day time frame noted in RCS policy, (2) missing a remediation date, or (3) included a remediation date predating either the submission of a plan or the date of inspection. RCS officials said that prior to 2022, RCS did not have the ability to review remediation data in a consolidated format and relied on reports from individual districts. They said new data systems allow them to track this information centrally and rectify any inaccuracies. However, RCS still needs to ensure that data from these systems are properly analyzed and used as part of a regular process.

VHA’s Processes to Model Demand and Identify Future Locations Do Not Fully Align with Selected Practices and Standards

VHA Uses a Demand Model to Identify Future Vet Center and Outstation Locations

VHA’s RCS recently developed a demand model to support its approach for identifying new Vet Center and outstation locations. In 2021, RCS partnered with VHA’s actuarial contractor to develop a model that projects demand for counseling services 1 to 5 years out, measured in anticipated service hours.[42] This model estimates the population eligible for counseling services and demand for those services using data on Vet Center usage, Census population data, and demographic data from the Department of Defense.[43]

Outputs from this model are used to identify the geographic areas where there is demand for counseling services and insufficient services are currently offered. RCS officials told us they have used this model to identify the need for three new Vet Center locations in Clarksville, Tennessee, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Fredericksburg, Virginia.[44] As of August 2023, RCS had used this model to project those geographic locations with the greatest degree of unmet demand for fiscal year 2028 (see table 4).

Table 4: Counties with Greatest Projected Unmet Demand for Counseling Services for Fiscal Year 2028 (As of August 2023)

|

State |

County |

Existing RCS location |

|

1. Virginia |

Spotsylvania |

Pending – Vet Center approved for Fredericksburg, Virginia |

|

2. Washington |

Clallam |

Yes – Community Access Point |

|

3. Idaho |

Bonneville |

Yes - Vet Center and Community Access Point |

|

4. Oregon |

Klamath |

Yes - Mobile Vet Center |

|

5. Arkansas |

Garland |

Yes - Community Access Point |

|

6. Virginia |

Augusta |

No |

|

7. Virginia |

Orange |

Pending – Vet Center approved for Fredericksburg, Virginia |

|

8. Mississippi |

Lowndes |

No |

|

9. Virginia |

Henry |

No |

|

10. Mississippi |

Lamar |

Yes - Community Access Point |

|

11. Washington |

Jefferson |

Yes – Community Access Point |

|

12. Arizona |

Apache |

Yes – Outstation and Mobile Vet Center |

|

13. Nevada |

Churchill |

No |

|

14. Illinois |

Adams |

No |

|

15. Mississippi |

Jones |

Yes - Community Access Point |

Source: Readjustment Counseling Service (RCS) and U.S. Census Bureau data as of August 2023. | GAO‑25‑106781

RCS officials told us they validate the information provided by this model through outreach to veterans and community partners to confirm the extent of demand. RCS officials noted that they prefer to first establish a community access point or outstation to test demand for services, prior to establishing a fully staffed Vet Center.[45]

VHA’s Processes for Actuarial Modeling Do Not Fully Align with Selected Practices and Standards

VHA’s processes, including those related to documentation, for modeling demand for counseling services do not fully align with three of eight actuarial standards of practice and internal control standards in areas related to (1) internal data validation, (2) external data validation, (3) model testing and validation, and (4) model uncertainty.[46] By following the practices and standards we discuss below, RCS will be better positioned to determine those locations where there will be the greatest unmet demand for counseling services.

Internal data validation. RCS does not have a documented process to validate internal data used as inputs for the projection model and did not document communications to the contractor on data quality, including any limitations. To project demand for counseling services and identify the need for future Vet Center locations, RCS provides the actuarial contractor with a variety of data including the number of clients served, hours of counseling service provided, location, and type of counseling (individual, group, family, etc.). The contractor relies on RCS to ensure the quality of the data RCS provides for use in the actuarial model. However, RCS uses data from various VA offices and does not have a process to validate the data and assumptions it provides to the contractor as inputs to the model. Further, according to the contractor, if the provided data are inaccurate or incomplete, the modeled projections based on those data may also be inaccurate or incomplete. In addition, despite the contractor’s reliance on RCS data, RCS does not provide documentation to the contractor on data quality, including any limitations affecting these data.

According to relevant actuarial standards of practice, when actuaries use data provided to them by others, the accuracy and completeness of the data is the responsibility of those who supply the data. The actuary is not required to perform an audit of the data.[47] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that agencies should obtain relevant data from reliable internal and external sources and process the obtained data into quality information.[48]

RCS officials told us they have not established a process to validate internal data for the model because the data come from various VA offices and databases that all have existing quality assurance practices.[49] RCS officials added that they meet with the contractor to discuss the data’s quality and limitations. We have previously noted the importance of establishing procedures for communicating all relevant information on the quality of VA data being used in a model and ensuring the quality of data pulled from various data owners in VA.[50] Without a process to ensure the data pulled from various VA offices and databases are validated and data limitations are property communicated to the contractor, RCS cannot know how much confidence it can reasonably place in the model when identifying where to locate future Vet Centers and outstations.

External data validation. RCS does not document the modeling assumptions the actuarial contractor made based on external data. The actuarial contractor relies on several external data sources to project demand for counseling services, including demographic data from the Department of Defense and U.S. Census Bureau. The actuarial contractor told us it reviews the reasonableness of external data used in the model, including comparing it to data from previous years, when possible, but does not audit the external data for accuracy. In addition, the actuarial contractor said it generally consults with VHA stakeholders when deciding which external data sources to use or when making modeling assumptions based on this external data.

However, RCS officials told us they do not require the actuarial contractor to provide documentation of its external data validation and assumptions. RCS officials told us that the contractor documents decisions, including modeling assumptions and data decisions made during meetings with VHA stakeholders. While RCS provided us with some documents that reference the collaboration between the contractor and VHA stakeholders, RCS did not provide documentation of the modeling assumptions the actuarial contractor made based on the external data. For example, the contractor told us it used data from Pew Research Center, which was based on survey results, to inform the assumption for pre-9/11 Gulf War era combat veterans eligible for counseling services. However, RCS did not provide documentation of how these assumptions were made.

According to actuarial standards of practice, while not required to audit external data provided by others, actuaries should consider preparing and retaining documentation in a form such that another qualified actuary could assess the reasonableness of the actuary’s work.[51] In addition, federal internal control standards state that agencies should obtain relevant data from reliable internal and external sources and process the obtained data into quality information.[52]

Model testing and validation. RCS does not have documentation that the actuarial contractor evaluated model risks. The contractor told us it has an internal process to test and review the demand model. According to the contractor, the model goes through four levels of peer review before the demand projections are provided to RCS. In addition, the contractor told us it conducts an impact analysis, which compares the differences between projected demand and actual demand. However, RCS did not have documentation of the contractor’s model testing and validation because RCS has not required the contractor to provide documentation of these processes. RCS officials told us they plan to ask for a summary of the contractor’s sensitivity testing around trends and seasonality as part of the contractor’s future deliverables, pending contract award and funding.

Relevant actuarial standards of practice state that actuaries should evaluate model risk and if appropriate, take reasonable steps to mitigate that risk.[53] In addition, federal internal control standards state that management should communicate with, and obtain quality information from, external parties using established reporting lines.[54]

Model uncertainty. The documentation provided to us by RCS did not provide sufficient clarity for our qualified actuary to fully understand the actuarial uncertainty of the contractor’s work. Specifically, this documentation did not include an assessment of the model’s overall degree of uncertainty associated with projections of demand for counseling services and potential output variability, because RCS does not require the contractor to assess, document, and communicate uncertainties associated with the demand model and how model output might vary.[55] RCS officials told us they do not require the contractor to provide certain information on uncertainties, such as potential ranges of demand, because these ranges may lead to inaccurate data analysis. However, without information on the uncertainty of the model, RCS may not be fully informed of, for example, how the model output might vary when using it to make decisions.

RCS’s long-range plan includes an objective that emphasizes the importance of using data to predict demand and inform decisions on the location of new Vet Centers.[56] Further, federal internal control standards state that management should communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the agency’s objectives, and identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving an agency’s defined objectives.[57]

By better documenting and more effectively communicating its modeling process and the model’s overall uncertainty, RCS could ensure it understands how to best use model output to identify future Vet Center and outstation locations.

Conclusions

Vet Centers play a pivotal role in helping veterans, servicemembers, and their families. VHA’s RCS has recognized the importance of ensuring that Vet Centers are welcoming, well-maintained, and appropriately located and has taken steps to provide the information and resources necessary to lease and improve space as needed. However, RCS does not fully follow characteristics of an effective asset management framework. Specifically, RCS has not developed certain guidance and policies that could help it more effectively manage these assets. For example, because RCS has not developed a strategic asset management plan or policies that would allow it to prioritize the requested improvements to Vet Centers, it could face challenges using its resources in ways that best support its mission. In addition, because RCS does not provide clear, consistent, and complete guidance for its annual inspection process, it cannot ensure it is collecting quality data about the physical condition of its Vet Centers, including deficiencies that need remediation. Moreover, because RCS does not fully evaluate the performance of its asset management processes, it cannot ensure these processes are helping it meet its objectives.

Placing new Vet Centers where demand will be greatest is vital to VHA’s goal of providing timely and accessible counseling services. However, the effectiveness of RCS’s actuarial model for projecting demand depends not just on the model itself but the incorporation of actuarial standards of practice and internal control standards related to the quality of the input, the assumptions used, and the model’s uncertainties. Because RCS is not communicating important information to the contractor, nor requiring the communication of additional important information from the contractor, RCS cannot be assured it has all the information it needs to understand how to use the model’s output and make the best possible selections for future locations. By following these practices and standards, RCS will be better positioned to determine those locations where there is the greatest unmet demand for counseling services.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following eight recommendations to VHA:

The Chief Readjustment Counseling Officer of RCS should develop a strategic asset management plan that outlines RCS’s asset management approach, as well as how that approach ties to RCS’s mission and objectives. (Recommendation 1)

The Chief Readjustment Counseling Officer of RCS should develop written procedures to prioritize improvements to Vet Centers and outstations based on specific criteria. (Recommendation 2)

The Chief Readjustment Counseling Officer of RCS should develop guidance to clarify its processes and help ensure consistent data are collected related to inspecting Vet Centers and outstations and remediating deficiencies. (Recommendation 3)

The Chief Readjustment Counseling Officer of RCS should develop written procedures to evaluate the performance of its asset management processes to identify any necessary improvements to its management of those assets. (Recommendation 4)

The Chief Readjustment Counseling Officer of RCS should document processes for validating VA data used as an input to the demand model and communicate the findings including known relevant data limitations to the actuarial contractor. (Recommendation 5)

The Chief Strategy Office of VHA should require its actuarial contractor to provide documentation of its processes to validate external data and the key actuarial assumptions made using the external data, including the contractor’s rationale for assumptions used in the demand model. (Recommendation 6)

The Chief Strategy Office of VHA should require its actuarial contractor to document and communicate to RCS the process for and results of the contractor’s evaluation of the actuarial model risk. (Recommendation 7)

The Chief Strategy Office of VHA should require its actuarial contractor to provide documentation of the overall uncertainty associated with the demand model, including output variability of projected demand. (Recommendation 8)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to VA for review and comment. VA provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendix II. In its written comments, VA concurred with all eight of the report’s recommendations and identified actions VHA is taking to implement them. VA raised concerns that the language in our draft report would lead readers to think that we found errors in its demand model results. We adjusted the language in the report to ensure that it is clear that our findings are focused on the extent to which VHA’s modeling processes follow selected actuarial practices and internal control standards. VA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committee, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-2834 or MarroniD@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

David Marroni

Director, Physical Infrastructure Issues

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for us to review the physical infrastructure of Vet Centers and planned future investments in those facilities.[58] This report examines: (1) how the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) obtains and improves space for Vet Centers and outstations, (2) how VHA monitors the physical condition of Vet Centers and outstations, (3) the extent to which VHA’s asset management processes for Vet Centers align with key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework, and (4) the extent to which VHA’s modeling processes for assessing future location needs follow selected actuarial practices and internal control standards.

To address all our objectives, we reviewed Readjustment Counseling Service’s (RCS) annual reports to Congress on Vet Center activities from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2023.[59] We also interviewed district officials from each of RCS’s five regional districts and Vet Center directors from five selected Vet Centers.[60] We selected Vet Centers to ensure we included: (1) a Vet Center from each district; (2) a Vet Center with at least one deficiency related to the physical condition of the facility in the fiscal year 2023 inspection; and (3) one Vet Center with an attached outstation. Information obtained from our interviews with these officials is not generalizable but provided useful insights from local officials. Further, we interviewed representatives from three veterans service organizations —–American Legion, Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, and the Wounded Warrior Project—which we selected to ensure representation of different populations who are eligible for Vet Center services.

To describe how VHA obtains and improves space for Vet Centers and outstations, we reviewed VHA and RCS documentation, including guidance and policies on leasing and making improvements to Vet Center space. We also compared RCS and Vet Centers’ efforts to VHA Directive 1500, which outlines roles and responsibilities with respect to the leasing process.[61] We interviewed officials from RCS and VA, including the Office of Asset Enterprise Management and Office of Procurement and Logistics, to determine how RCS obtains and improves Vet Centers and outstation space. In addition, we interviewed General Services Administration officials on the process for agencies to obtain delegated leasing authority.

We analyzed RCS data for fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023 on the number of Vet Center leases, length for a portion of the leasing process, number of improvements made to Vet Center space, and cost of those improvements. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed RCS documentation, conducted electronic and manual testing of the data, and interviewed RCS officials responsible for maintaining the data. We found the data sufficiently reliable for our purposes of describing RCS’s leasing and improvement activity from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023.

To describe how VHA monitors the physical condition of Vet Centers and outstations, we reviewed VHA and RCS documentation, including policies and guidance that establish RCS roles and responsibilities and the standards RCS uses to annually assess the physical condition of Vet Centers.[62] We also interviewed RCS officials on the processes to inspect Vet Centers and identify and remediate deficiencies.

We reviewed RCS data from fiscal year 2019 through 2023 about annual Vet Center inspections, including the date, method (in-person or virtual), results of those inspections, and steps to remediate deficiencies. To identify those inspection standards relevant to the scope of our work, we examined all standards included in the RCS annual inspection process and selected those we identified as related to the physical condition of the Vet Center space (hereinafter referred to as selected standards). An analyst also reviewed comments describing deficiencies related to these selected standards to identify common themes across Vet Center inspections. Another analyst reviewed and verified those results. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed RCS documentation, conducted electronic and manual testing of the data, and interviewed RCS officials responsible for maintaining the data. We found the data sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing the physical condition of Vet Centers.

We also conducted site visits to three of the five selected Vet Centers and compared the condition of these Vet Centers to the most recent annual inspection reports. (See table 5 for a list of the Vet Centers we selected and visited.) We documented our observations using an analyst data entry form and compared the condition of these Vet Centers against the most recent annual inspection reports. The results of the information obtained during our site visits are not generalizable to all Vet Centers.

|

Vet Center |

|

|

District 1: North Atlantic |

Washington, D.C. Vet Center* |

|

District 2: Southeast |

Lakeland, FL Vet Center* |

|

District 3: Midwest |

Chicago, IL Vet Center |

|

District 4: Continental |

New Orleans, LA Vet Center* |

|

District 5: Pacific |

Anchorage, AK Vet Center |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106781

Notes: We visited the Vet Centers denoted with an asterisk in-person between October 2023 and January 2024. The Anchorage Vet Center has an outstation in Soldotna, Alaska.

To examine the extent to which VHA’s asset management processes for Vet Centers align with key characteristics of GAO’s asset management framework, we reviewed VHA and RCS policies, processes, and planning documents related to asset management, and interviewed RCS officials. We compared this information to six key characteristics we previously identified for an effective asset management framework.[63]

An analyst assessed the extent to which RCS’s processes aligned with the leading practices using a three-tier system: “Fully Aligns,” “Partially Aligns,” and “Does Not Align.” We determined that RCS’s processes fully aligned with a key characteristic when we saw evidence that RCS followed all aspects of the characteristic. We determined that the processes partially aligned with a characteristic when RCS followed some, but not all, aspects of the characteristic. We determined that the processes did not align with a characteristic when we did not see evidence of RCS following a characteristic. A second analyst then reviewed the evidence and concurred with the assessment or suggested changes. Any differences were then reconciled by the two analysts.

To examine the extent to which VHA’s modeling processes for assessing future Vet Center location needs follow selected practices and standards, we reviewed actuarial documents and other modeling documents provided by RCS.[64] We also reviewed the demand models for 2021 and 2023 developed for RCS by the modeling contractor. We reviewed documented data sources used for developing the demand model and VA’s processes for selecting the data and ensuring data quality and data credibility. To evaluate the actuarial modeling process, we reviewed RCS documents about the actuarial assumptions and methods RCS used to develop the 10-year projection of future counseling service demand. [65]

We reviewed RCS’s documents on actuarial analysis of risk classifications and the rationale for actuarial assumptions applied. In addition, we reviewed the actuarial models used to estimate the Veteran population eligible for RCS services, the use of RCS services, and costs by RCS location. Further, we reviewed the RCS model’s use of external data including data from other government agencies, such as Department of Defense and U.S. Census Bureau. We also examined RCS’s modeling processes and the findings included in its actuarial documents. We compared the methodology, the results, and the process against eight Actuarial Standards of Practice and three Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, where applicable. We selected these standards because they are relevant to how the actuarial contractor performs the actuarial services and communicates the results of those services. Finally, we interviewed RCS officials and representatives of VHA’s modeling contractor on the development and validation of the model and how the model’s outputs are used to identify the potential need for new Vet Center locations.

In performing this analysis, we relied on actuarial reports and documentation provided by RCS. We reviewed the documents for reasonableness but did not audit them for accuracy. This review is not a technical review, and we did not verify the accuracy of the calculations performed by the actuaries who developed the RCS service demand projections.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

David Marroni, (202) 512-2834 or MarroniD@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following individuals made key contributions to this report: Crystal Huggins (Assistant Director); Kristen Farole (Analyst in Charge); Melissa Bodeau; Laura Bonomini; Emily Crofford; George Depaoli; Elizabeth Dretsch; Lijia Guo; Alyssa Hundrup; Alma Laris; Malika Rice; Timothy Smith; Frank Todisco; Alicia Wilson; Malissa Winograd; and John Yee.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Department of Veterans Affairs, National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018-2028 (Washington, D.C.: June 29, 2018).

[2]Veterans’ Health Care Amendments of 1979, Pub. L. No. 96-22, tit. I, § 103(a), 93 Stat. 47, 48 (codified as amended at 38 U.S.C. § 1712A).

[3]In October 2020, Congress expanded eligibility for Vet Centers to include, among other groups, members of reserve components who served on active service in response to a national emergency or major disaster declared by the President. Vet Center Eligibility Expansion Act, Pub. L. No 116-176, § 2, 134 Stat. 849 (2020). See 38 U.S.C. § 1712A(a)(1)(C) for currently eligible veterans and servicemembers and their families.

[4]Department of Veterans Affairs, FY 2022–2028 Strategic Plan. Vet Centers also provide counseling services at satellite locations, such as outstations.

[5]James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. Law 117‑263, § 5216(e), 136 Stat. 2395, 3216-17 (2022).

[6]VHA’s 303 Vet Centers are organized into five regional districts. Our review included the following five Vet Centers: (1) Washington, D.C. Vet Center; (2) Lakeland Vet Center (Florida); (3) Chicago Vet Center (Illinois); (4) New Orleans Vet Center (Louisiana); and (5) Anchorage Vet Center (Alaska).

[7]GAO, Federal Real Property Asset Management: Agencies Could Benefit from Additional Information on Leading Practices, GAO‑19‑57 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 5, 2018). The six characteristics are: (1) maintaining leadership support, (2) promoting a collaborative organizational culture, (3) establishing formal policies and plans, (4) maximizing an asset portfolio’s value, (5) using quality data, and (6) evaluating and improving asset management practices. Specifically, an analyst assessed the extent to which RCS’s processes aligned with the leading practices using a three-tier system: Fully Aligns, Partially Aligns, and Does Not Align. A second analyst then reviewed the evidence and concurred with the assessment or suggested changes. Any differences were then reconciled by the two analysts.

[8]The Actuarial Standards Board’s standards of practice describe the procedures an actuary should follow when performing actuarial services and identify what the actuary should disclose when communicating the results of those services. The relevant actuarial standards of practice are: 12 (Risk Classification for All Practice Areas); 23 (Data Quality); 25 (Credibility Procedures); 38 (Catastrophe Modeling for All Practice Areas); 41 (Actuarial Communications); 46 (Risk Evaluation in Enterprise Risk Management); 47 (Risk Treatment in Enterprise Risk Management); and 56 (Modeling).

[9]Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved, see GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). The Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government’s relevant Principles are: 7 (Identify, Analyze, and Respond to Risks); 13 (Use Quality Information); and 15 (Communicate Externally).

[10]VHA Directive 1500(4), Readjustment Counseling Service (VHA 2021, amended 2023).

[11]Military sexual trauma refers to trauma resulting from sexual assault, battery, or harassment experienced during military service.

[12]See 38 U.S.C. § 1712A(a)(1)(C) for information on eligibility for veterans, servicemembers, and their families and descriptions of authorized services.

[13]RCS also provides counseling services via phone and VHA’s video-capable telehealth platform.

[14]VA Directive 1500(4).