CYBERSECURITY WORKFORCE

Departments Need to Fully Implement Key Practices

Report to Congressional Addressees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106795. For more information, contact David Hinchman at (214) 777-5719 or hinchmand@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106795, a report to congressional addressees

Departments Need to Fully Implement Key Practices

Why GAO Did This Study

Cybersecurity professionals are critical to developing, managing, and protecting the systems that support federal operations. The Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) of 2014 includes a provision for GAO to periodically evaluate federal agencies’ information security practices. GAO’s specific objectives were to (1) determine the extent to which selected departments implemented cybersecurity workforce practices, and (2) describe the selected departments’ cybersecurity workforce challenges and mitigation actions and the extent to which they evaluated the effectiveness of those actions. To do so, GAO identified the five federal non-military departments with the largest number of cybersecurity employees. GAO assessed the departments' cybersecurity workforce documentation against applicable leading practices. Further, GAO interviewed officials from the selected departments regarding workforce practices and challenges.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making a total of 23 recommendations to the five departments--Commerce, Homeland Security, Health and Human Services, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs--to fully implement applicable practices and determine the effectiveness of mitigation actions. Three departments agreed with the recommendations, one agreed with two and partially agreed with three, and one department did not agree or disagree. GAO maintains that all of its recommendations are warranted.

What GAO Found

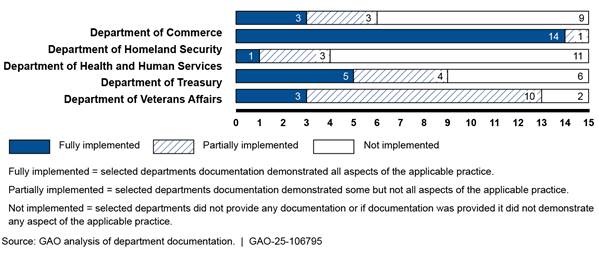

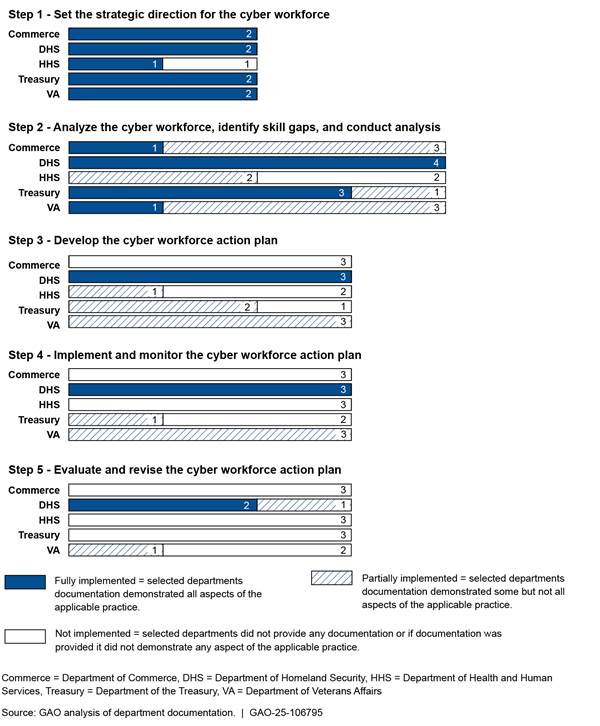

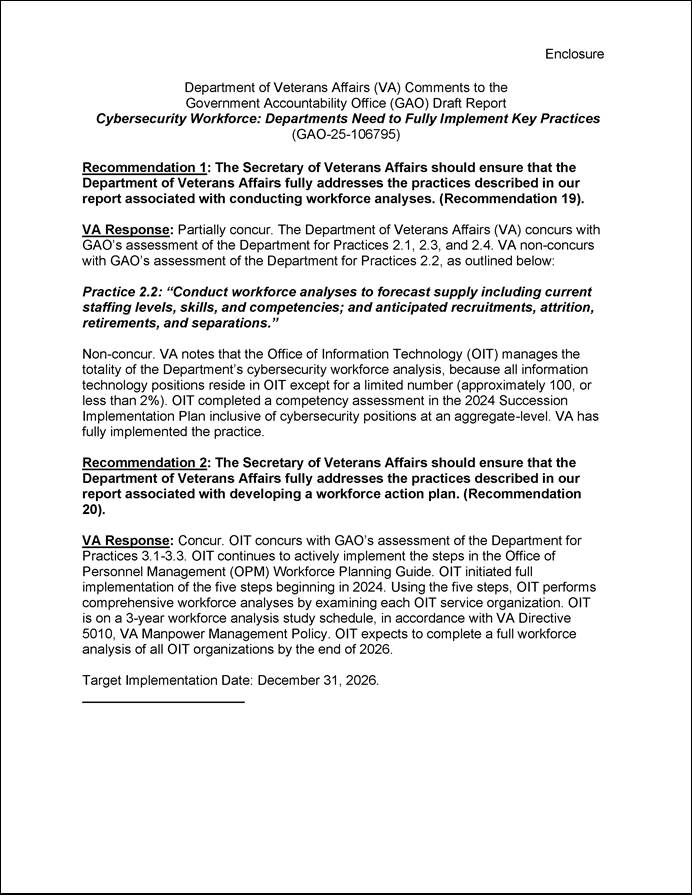

The Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) Workforce Planning Guide outlines a five-step process for workforce planning efforts: (1) setting the strategic direction, (2) conducting workforce analyses, (3) developing workforce action plans, (4) implementing and monitoring workforce planning, and (5) evaluating and revising these efforts. Within the five steps are 15 applicable practices that are central to effectively managing the cybersecurity workforce. Of the 15 applicable practices, the Department of Homeland Security fully implemented 14 of them. However, the other four selected departments were not as consistent in their implementation of the practices (see figure).

Most of the selected departments reported that they had not fully implemented all 15 practices due, in part, to managing their cybersecurity workforces at the component level rather than the departmental level, as intended by OPM. Until the departments implement these practices, they will likely be challenged in having a cybersecurity workforce with the necessary skills to protect federal IT systems and enable the government’s day-to-day functions.

Officials at the five selected departments cited three primary types of cybersecurity workforce management challenges: inadequate funding, difficulties with recruitment, and difficulties with retention. The departments described actions taken to mitigate these challenges. However, none of the departments had evaluated their actions taken to determine the extent to which they had been effective in addressing the challenges. Without evaluating the effectiveness of their mitigation actions, department officials will not know the extent to which their actions are addressing identified challenges and strengthening the cybersecurity workforce.

Abbreviations

|

CIO |

chief information officer |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FISMA |

Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Sciences |

|

MCO |

mission critical occupation |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 16, 2025

Congressional Addresses

A resilient, skilled, and dedicated cybersecurity workforce is essential to protecting federal IT systems as well as enabling the government’s day- to-day functions.[1] Building and maintaining the cybersecurity workforce is one of the federal government’s most important challenges as well as a national security priority.

Nevertheless, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and our prior reports have stated that the federal government faces a persistent shortage of cybersecurity and IT professionals.[2] For example, in our 2024 High-Risk Series report, we identified four major cybersecurity challenges and 10 critical actions. One of these actions was to address cybersecurity workforce management challenges.[3]

The Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA) requires federal agencies to develop, document, and implement an information security program to protect the information and systems that support the agencies’ operations and assets.[4] The act includes a provision for GAO to periodically evaluate federal agencies’ information security policies and practices that are required by FISMA. A key portion of these federal agency-wide cybersecurity programs include evaluating the agencies’ cybersecurity workforce management policies.

Our specific objectives were to (1) determine the extent to which selected departments implemented applicable cybersecurity workforce management practices, and (2) describe the cybersecurity workforce management challenges and mitigation actions that selected departments have identified and determine the extent to which departments evaluated the effectiveness of those actions.

For both objectives, we identified the five federal non-military agencies with the largest number of cybersecurity employees based on the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) Enterprise Human Resources Integration system for fiscal year 2021 data.[5] Specifically, we identified the five federal agencies with the greatest number of cybersecurity employees assigned to OPM’s General Schedule 1550 (Computer Science) and 2210 (Information Technology Management) occupational series codes. According to our prior work and OPM, these codes were the most frequently used for identifying federal cybersecurity professionals.[6] The five federal non-military departments with the largest number of cybersecurity employees were the Departments of Commerce, Health and Human Services (HHS), Homeland Security (DHS), and Treasury, and Veterans Affairs (VA).

To address the first objective, we identified applicable workforce management practices based on our review of IT and cybersecurity workforce planning and management practices identified in OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide and GAO’s Key Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning.[7] OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide outlines a continuous five-step process for (1) setting the strategic direction, (2) conducting a workforce analyses, (3) developing the workforce action plan, (4) implementing and monitoring the workforce action plan, and (5) evaluating and revising the workforce action plan. In addition, GAO’s Key Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning includes a framework for developing, communicating, and implementing strategic workforce planning.

We analyzed these documents and the five-step process, and selected 15 practices from both documents that can be categorized as supporting federal cybersecurity workforce management.[8] We selected practices that were applicable to effective management of the workforce, including whether the selected departments had workforce strategic plans and action plans in place; conducted workforce analyses; and implemented, monitored, evaluated, and revised the workforce action plans.

We reviewed department-level cybersecurity workforce management documentation from the five selected departments, including workforce planning policies and procedures, strategic plans, cybersecurity workforce documents, and staffing performance metrics. We compared the documentation to the 15 selected applicable practices. We then determined whether the five selected departments had fully implemented, partially implemented, or not implemented each of the 15 applicable practices.[9]

To address the second objective, we conducted interviews with relevant officials from the five selected departments and asked department officials for documentation on their identified challenges with managing their cybersecurity workforce. We then compiled a list of cybersecurity workforce management challenges identified by the five selected departments and grouped them into three primary types of challenges.

Further, we determined the extent to which the five selected departments had identified actions to mitigate their challenges through those interviews and document reviews. We then determined the extent to which the selected departments had evaluated the effectiveness of their mitigation actions by comparing them to practices identified in OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide and GAO’s prior work for measuring workforce performance.[10] We supplemented our analyses with interviews of staff from the five selected departments who performed various IT, cybersecurity-related, and human capital functions. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Congress has enacted various laws, and OPM and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have issued guidance, that called for departments and agencies to implement workforce planning processes. These processes are essential for ensuring that federal departments and agencies have the talent, skills, and experience mix they need to execute their missions and program goals, including strengthening their departments’ cybersecurity workforce. For example:

· The Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 required agency chief information officers (CIO) to annually perform workforce-related tasks, such as develop strategies and specific plans for hiring, training, and professional development to address any workforce knowledge and skill gaps.[11]

· The E-Government Act of 2002 required the Director of OPM, in consultation with the Director of OMB, the CIO Council, and the Administrator of General Services to, among other things, analyze the personnel needs of the federal government related to IT and information resource management.[12]

· FISMA requires agencies to develop, document, and implement agency-wide information security programs to protect their IT systems.[13] The act also requires agencies to submit reports on their information security programs to OMB, DHS, GAO, and Congress. As directed by OMB, these reports are to include the metrics that the agencies used to assess their progress toward outcomes intended to strengthen federal cybersecurity. FISMA also included provisions for GAO to periodically evaluate federal agencies’ information security policies and practices. Additionally, GAO is to evaluate agencies’ implementation of FISMA requirements, which include having sufficient personnel to carry out their responsibilities.

· The Federal Cybersecurity Workforce Assessment Act of 2015 required OPM, with support from the NIST, to establish a coding structure to be used in identifying all federal civilian and non-civilian positions that require the performance of IT, cybersecurity, or other cybersecurity-related functions.[14] The act also required agencies, in consultation with OPM and NIST, to then use this coding structure to annually assess, among other things, the IT, cybersecurity, and other cybersecurity-related work roles of critical need in their workforce.[15]

· In November 2020, NIST released an updated version of its Workforce Framework for Cybersecurity.[16] This guide included a common lexicon that categorizes and describes cybersecurity-related work roles and functions. The framework is intended to improve communication about how to identify, recruit, develop, and retain cyber talent.

· In November 2022, OPM published a Workforce Planning Guide as a resource for federal agency leaders and employees to use for planning and analyzing their workforce, identifying gaps, as well as implementing workforce action planning efforts.[17] Among other things, the Workforce Planning Guide detailed a continuous workforce process for identifying the size and composition of a workforce needed to achieve an organization’s goals and objectives.

· In February 2024, OPM published a Workforce of the Future playbook to enunciate the specific actions agencies could take to provide the foundation for the workforce of the future.[18] The Playbook was organized based on three pillars: inclusive, agile and engaged, and having the right skills. OPM, in partnership with its stakeholders, identified areas in the Playbook, that if strengthened, would enable federal agencies to adapt effectively to the rapidly evolving nature of work and to keep pace with other industries.

OPM Established a Cyber Workforce Dashboard

In addition to its Workforce Planning Guide and Workforce of the Future Playbook, OPM created the Cyber Workforce Dashboard to support departments in cybersecurity workforce planning efforts and in making data-driven decisions regarding current and future cybersecurity workforce requirements. Specifically, in April 2023, OPM launched its web-based Cyber Workforce Dashboard. The dashboard contained two viewing options: one for agency use and one for public use. OPM officials stated that the dashboard’s data comes from OPM’s Enterprise Human Resources Integration system and annual data calls made to the departments.[19]

According to officials from OPM’s Office of Strategic Workforce Planning, the dashboard version for agencies displayed work roles, hiring trends, workforce demographics, staffing gaps, and mission critical occupations. In addition, agencies could use the dashboard to track work role metrics, such as separations, compare data to benchmarks and other agencies, and review demographic information and hiring targets specific to each agency. The dashboard for the public allowed the user to view data across the federal departments, such as demographic trends and comparisons, the top 10 cybersecurity occupations, retirement eligibility, and separations.

Selected Workforce Management Practices Are Key to Effective Cybersecurity Management

Workforce planning processes are essential for ensuring that federal agencies have the talent, skills, and experience mix they need to execute their missions and achieve program goals. OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide outlines a continuous five-step process for (1) setting the strategic direction, (2) conducting workforce analyses, (3) developing the workforce action plan, (4) implementing and monitoring the workforce action plan, and (5) evaluating and revising the workforce action plan.[20] OPM officials stated that workforce planning is intended to be managed at the department level.

In addition, GAO’s Key Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning includes a framework for developing, communicating, and implementing strategic workforce planning.[21] Within the five primary steps are 15 selected applicable practices from OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide that are central to effectively managing the cybersecurity workforce.[22] GAO’s workforce planning guidance further supports and complements these practices.[23] Table 1 describes the 15 selected applicable practices for the cybersecurity workforce.

Table 1: Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM) Workforce Planning Guide Five-Step Process and the 15 Selected Applicable Practices for Cybersecurity Workforce Management

|

Cybersecurity workforce management step |

Description |

Selected applicable practices |

|

Step 1: Set Strategic Direction |

Understanding the agency’s cybersecurity strategy and related performance plans, and involving top management, employees, and other stakeholders in workforce planning. |

1.1 Develop a strategy that describes the agency’s cybersecurity goals and mission and identifies anticipated changes in the cybersecurity landscape over the next 3-5 years. |

|

1.2 Establish a governance process that involves top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

||

|

Step 2: Conduct Workforce Analyses |

Analyzing the agency’s cybersecurity workforce, identifying skill gaps, and conducting workforce analyses. |

2.1 Conduct workforce analyses to forecast demand, and identify the skills and competencies needed to meet future organizational demands. |

|

2.2 Conduct workforce analyses to forecast supply including current staffing levels, skills, and competencies; and anticipated recruitments, attrition, retirements, and separations. |

||

|

2.3 Identify the cybersecurity mission critical occupations to help ensure that the agency has the resources and talent it needs to function successfully. |

||

|

2.4 Conduct cybersecurity gap and risk analyses that evaluate the gap between supply and demand and analyze current and future workforce risks. |

||

|

Step 3: Develop Workforce Action Plan |

Identifying strategies to close workforce gaps, implementing those strategies, and assessing progress. |

3.1 Develop a cybersecurity workforce plan that identifies current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. |

|

3.2 Develop a cybersecurity workforce plan that includes strategies to close the cybersecurity gaps, such as recruiting, training, retraining, restructuring, use of contractors, succession planning, and technological enhancements. |

||

|

3.3 Develop a cybersecurity workforce action plan with metrics to evaluate success and achievement of desired results. |

||

|

Step 4: Implement and Monitor Workforce Action Plan |

Ensuring human and fiscal resources are in place, roles are understood, and the necessary communication, education, change management, and coordination are occurring; and monitoring progress against milestones. |

4.1 Communicate the cybersecurity workforce action plan to the agency’s leadership; and plan and implement a communication strategy that defines roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

|

4.2 Develop a plan that describes how implementation will occur, including information on key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

||

|

4.3 Implement and monitor the cybersecurity workforce action plan, including tracking information on the milestones, metrics, and targets from the cybersecurity workforce action plan. |

||

|

Step 5: Evaluate and Revise Workforce Action Plan |

Assessing continuous improvement, adjusting the cybersecurity workforce action plan to make course corrections, and addressing new workforce issues. |

5.1 Assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

|

5.2 Record actions taken, review lessons learned from the cybersecurity workforce action plan, and update or adjust metrics and targets as necessary. |

||

|

5.3 Conduct an analysis of the extent to which cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives are being achieved. |

Source: GAO analysis of cybersecurity workforce management practices identified in OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide and GAO’s Key Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning. | GAO‑25‑106795.

GAO Has Previously Reported on Challenges to Effective Federal IT Workforce Planning

We have previously reported on federal workforce planning.

· In October 2019, we reported that federal agencies varied widely in their efforts to implement key IT workforce planning activities that were critical to ensuring that agencies have the staff they need to support their missions.[24] We noted that while agencies took important steps towards identifying their workforces, most agencies had not fully implemented the key IT workforce activities. Agencies limited implementation of the IT workforce planning activities was due, in part, to not making IT workforce planning a priority.

Accordingly, we made 18 recommendations directing 18 of the 24 federal agencies to fully implement the eight key IT workforce planning activities. As of January 2025, agencies have fully implemented 16 of the recommendations and partially implemented two.

· In July 2022, we reported on workforce recruitment and retention processes, leading practices, and challenges at the Department of State.[25] Specifically, we evaluated 15 recruitment and retention practices and determined that State fully implemented one, partially implemented 11, and did not implement three. For example, we reported that State had collected training performance data, but did not recruit continuously year-round for most of its IT positions or regularly assessed staffing needs. We also identified challenges related to State recruiting and retaining its IT workforce, including (1) low entry-level pay and no recruiting incentives, (2) long hiring and security clearance process, (3) inaccurate position descriptions that did not accurately reflect actual IT job responsibilities, and (4) limited promotions.

We noted that State addressed some of its IT workforce challenges, but the department had not monitored and evaluated those actions to determine whether they have been effective in addressing the recruitment and retention challenges. Accordingly, we made 16 recommendations to improve State’s IT workforce management. As of January 2025, one of the recommendations has been implemented.

· In September 2022, we reported on the Coast Guard’s implementation of workforce management leading practices.[26] Of the 12 selected recruitment, retention, and training leading practices, the Coast Guard fully implemented seven, partially implemented three, and did not implement two. For example, it leveraged available hiring incentives such as recruiting bonuses, relocation expenses, and student loan repayments. However, it had not developed a strategic workforce plan for its cyberspace workforce. Accordingly, we made six recommendations to the Coast Guard, including to determine the cyberspace staff needed to meet its mission demands and fully implement five recruitment and retention leading practices, such as establishing a strategic workforce plan for its cyberspace workforce. Coast Guard concurred with these recommendations. Coast Guard stated it is actively working to address each recommendation and has provided us updates. However, as of January 2025, we have not received evidence to close the recommendations.

· In our June 2024 high-risk update report, we stated that it was critical for the federal government to address cybersecurity workforce management challenges to help ensure it has a highly-skilled workforce, which is essential to a functioning government.[27] For example, we reported that federal agencies could strengthen cybersecurity by establishing and effectively implementing a comprehensive national cyber strategy and a government-wide cyber workforce plan. We also reported that while federal agencies had made progress in improving their cybersecurity workforce practices, they needed to take additional action to address challenges in hiring, training, and retaining their cybersecurity workforces.

Selected Departments Did Not Fully Implement Applicable Cybersecurity Workforce Management Practices

Of the 15 applicable practices, DHS fully implemented 14 of them. However, the other four departments were not as consistent in their implementation of the practices.

Figure 1 summarizes the extent to which the five selected departments implemented the practices within each of the five steps.

Figure 1: Extent to Which Selected Departments Implemented the Practices Within Each of the Five Cybersecurity Workforce Management Steps

Departments Largely Set the Strategic Direction

Almost all of the selected departments provided documentation that set the stage for the strategic direction of their cybersecurity workforces.

Table 2 provides a detailed assessment of the completeness of departments’ efforts to set the strategic direction for their cybersecurity workforces.

Table 2: Assessment of Five Selected Departments’ Implementation of Selected Applicable Practices for Step One: Set Strategic Direction

|

Department |

Rating |

GAO assessment |

|

Practice 1.1: Develop a strategy that describes the agency’s cybersecurity goals and mission and identifies anticipated changes in the cybersecurity landscape over the next 3-5 years. |

||

|

Commerce |

● |

Commerce provided a 5-year strategic plan, a 3-year cybersecurity strategy, and a technical statement of direction that described the department’s cybersecurity goals and mission. The plan also identified anticipated changes to the department’s cybersecurity landscape. |

|

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

● |

DHS provided a 5-year department level IT strategic plan that described the department’s cybersecurity goals and mission. The plan also identified anticipated changes to the department’s cybersecurity landscape. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

● |

HHS provided a 5-year department level strategic plan and a 3-year IT strategic plan that addressed the department’s cybersecurity activities and described its goals and mission. The plan also identified anticipated changes to the department’s cybersecurity landscape. |

|

Treasury |

● |

Treasury provided a 5-year department level strategic plan and a 5-year human capital operating plan that described the department’s cybersecurity goals and mission. The plan also identified anticipated changes to the department’s cybersecurity landscape. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

● |

VA provided a 5-year IT workforce plan that described the department’s cybersecurity goals and mission. The plan also identified anticipated changes to the department’s cybersecurity landscape. |

|

Practice 1.2: Establish a governance process that involves top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

||

|

Commerce |

● |

Commerce provided a cybersecurity workforce strategy and a technical statement of direction that described the department’s governance process that involved top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS provided a department-level cybersecurity workforce strategy and a department-level cybersecurity implementation plan that described the department’s governance process that involved top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

|

HHS |

○ |

While HHS provided an IT strategic plan and a department level strategic plan, the documentation did not describe the department’s governance process nor described how it involved top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

|

Treasury |

● |

Treasury provided a human capital operating plan, a strategic workforce planning policy, and a strategic workforce planning guide that described the department’s governance process that involved top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

|

VA |

● |

VA provided workforce charters and directives that described the department’s governance process that involved top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan. |

Legend: ● Fully implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated all aspects of the selected applicable practices;

◐ Partially implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated some, but not all, aspects of the selected applicable practices;

○ Not implemented = departments did not provide any documentation, or if documentation was provided, it did not demonstrate any aspect of the selected applicable practices.

Source: GAO analysis of department IT workforce planning policies and documentation. | GAO‑25‑106795

Most Departments Partially Conducted Workforce Analyses

DHS fully implemented all four applicable practices, but the other four departments did not. Specifically:

· Treasury fully implemented three practices,

· Commerce fully implemented one practice,

· VA fully implemented one practice, and

· HHS partially implemented two practices.

Table 3 provides a detailed assessment of the completeness of departments’ efforts to conduct workforce analyses.

Table 3: Assessment of Five Selected Departments’ Implementation of Selected Applicable Practices for Step Two: Conduct Workforce Analyses

|

Department |

Rating |

GAO assessment |

|

Practice 2.1: Conduct workforce analyses to forecast demand, identify the skills and competencies needed to meet future organizational demands. |

||

|

Commerce |

◐ |

Commerce provided some documentation on workforce analysis to forecast demand, including identification of some skills and competencies needed. However, this documentation did not detail what the department’s current cybersecurity workforce looked like, nor its optimal workforce capability to meet its future workforce demands. |

|

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

● |

DHS provided documentation of a cybersecurity workforce analysis to forecast its demand, specifically for the department’s cybersecurity work roles of critical need, including the skills and competencies needed to meet the department’s future organizational demands. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

○ |

HHS did not provide documentation of a workforce analysis to forecast demand. |

|

Treasury |

◐ |

Treasury provided a workforce demand analysis to forecast the department’s future workforce needs based on the Office of Personnel Management occupational codes. However, the analysis did not identify specific skills and competencies needed to meet the department’s future organizational demands. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

● |

VA provided documentation including VA’s Office of Information Technology strategic workforce plan, that included an analysis to forecast its demand. It also included information related to the skills and competencies needed to meet the department’s future organizational demands. |

|

Practice 2.2: Conduct workforce analyses to forecast supply including current staffing levels, skills, and competencies; and anticipated recruitments, attrition, retirements, and separations. |

||

|

Commerce |

◐ |

Commerce provided some documentation of a cybersecurity workforce analysis to forecast the department’s workforce supply including the full-time equivalent shortages for its roles of critical need, specifically the type and numbers of employees. However, this documentation did not describe the department’s current cybersecurity supply including current staffing levels, skills, and competencies, anticipated recruitments, attrition, retirements, and separations. Commerce officials stated succession planning assessments were conducted to review high-risk leadership positions and to identify potential employees to ensure the department had a pipeline of candidates to backfill IT and cybersecurity positions. While Commerce officials stated the department had a succession planning strategy and assessment that identified critical positions, talent pipeline, workforce strengths, weakness, and future needed competencies, the strategy was in draft. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS provided documentation of a cybersecurity workforce analysis to forecast the department’s workforce supply, including current staffing levels, skills, and competencies; and anticipated recruitments, attrition, retirements, and separations, specifically for its cybersecurity work roles of critical need. |

|

HHS |

◐ |

HHS provided some documentation of a cybersecurity workforce analysis to forecast the department’s workforce supply including mission critical occupations and 2210 occupational series. While this presentation included specific metrics such as retirement eligibility and new hire, retention, and attrition rates, it did not include details on the department’s current cybersecurity workforce including staffing levels, skills, and competencies. It also did not include information about the department’s recruitments and separations. |

|

Treasury |

● |

Treasury provided evidence of conducting a cybersecurity workforce analysis to forecast the department’s supply, including anticipated recruitments, retirements, and current staffing levels. Treasury officials provided an analysis of the department’s current cybersecurity occupational series staffing levels, skills distribution, and attrition rates, as well as a report that discussed the department’s 2210 occupational series retirements. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided the department’s Office of Information and Technology strategic workforce plan, which identified the current staffing levels, anticipated supply, and impacts to anticipated supply for its mission critical occupations. However, this plan did not contain any discussion of the department’s current workforce skills and competencies. |

|

Practice 2.3: Identify the cybersecurity mission critical occupations to help ensure that the agency has the resources and talent it needs to function successfully. |

||

|

Commerce |

● |

Commerce provided documentation regarding the department’s cybersecurity work roles of critical need for mission critical occupations to help ensure that it has the resources and talent it needs to function successfully. This documentation included progress metrics using fiscal year 2018 as a baseline to target the number of fiscal years 2019 to 2023 resources. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS provided documentation that identified its cybersecurity mission critical occupations to help ensure the department had the resources and talent it needed to function successfully. |

|

HHS |

◐ |

HHS provided some documentation regarding its cybersecurity mission critical occupations, including metrics for its 2210 occupational series. However, this documentation lacked a discussion of the department’s cybersecurity resources and talent needed to function successfully. |

|

Treasury |

● |

Treasury provided a human capital operating plan for fiscal years 2022 to 2026 that identified mission critical occupations to help ensure that the department has the resources and talent it needs to function successfully. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided a human capital operating plan and the department’s Office of Information and Technology strategic workforce plan, which identified some, but not complete information regarding its cybersecurity mission critical occupations projections, such as type, number, and location of employees. |

|

Practice 2.4: Conduct cybersecurity gap and risk analyses that evaluate the gap between supply and demand and analyze current and future workforce risks. |

||

|

Commerce |

◐ |

Commerce provided documentation describing the department’s full-time equivalent shortages based on roles of critical need, specifically the type and numbers of employees. However, this documentation did not describe the department’s current cybersecurity workforces’ skills, competencies, or gaps in workforce supply and demand. The documentation also lacked an analysis of current and future workforce risks. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS conducted a cybersecurity gap and risk analyses that evaluated the gap between supply and demand and analyzed current and future workforce risks. |

|

HHS |

○ |

HHS did not provide documentation of a cybersecurity gap and risk analysis, a discussion of the gaps between the department’s current workforce supply and projected demand, nor current and future workforce risks. |

|

Treasury |

● |

Treasury conducted a cybersecurity gap and risk analyses that evaluated the gap between supply and demand and analyzed current and future workforce risks. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided an Office of Information and Technology strategic workforce plan that provided some information related to the department’s gaps in current and projected workforce needs, as well as current and future workforce risks. However, VA’s demand and supply analyses were incomplete, including the department’s analysis of workforce gaps. |

Legend: ● Fully implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated all aspects of the selected applicable practices;

◐ Partially implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated some, but not all, aspects of the selected applicable practices;

○ Not implemented = departments did not provide any documentation, or if documentation was provided, it did not demonstrate any aspect of the selected applicable practices.

Source: GAO analysis of department IT workforce planning policies and documentation. | GAO‑25‑106795

Most Departments Did Not Fully Develop Workforce Action Plans

DHS implemented all three applicable practices, but the other four departments did not. Specifically:

· VA partially implemented three practices,

· Treasury partially implemented two practices,

· HHS partially implemented one practice, and

· Commerce did not implement any practices.

Table 4 provides a detailed assessment of the completeness of departments’ efforts to develop their workforce action plans.

Table 4: Assessment of Five Selected Departments’ Implementation of Selected Applicable Practices for Step Three: Develop Workforce Action Plan

|

Department |

Rating |

GAO assessment |

|

Practice 3.1: Develop a cybersecurity workforce plan that identifies current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not provide a cybersecurity workforce plan that identified the department’s current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. Commerce provided documentation that described the department’s shortages in roles of critical need, specifically, the type and numbers of employees; however, this analysis was incomplete in that it did not comprehensively identify the department’s current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. |

|

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

● |

DHS provided a cybersecurity workforce action plan that identified the department’s current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. In addition, DHS provided an implementation plan supporting its cybersecurity workforce action plan, as well as DHS’s cyber workforce strategy that was shared with Congress. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

○ |

HHS did not provide a cybersecurity workforce plan that identified the department’s current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. |

|

Treasury |

◐ |

Treasury provided some information regarding the department’s current and future human capital needs as it related to its IT and cybersecurity mission critical occupations. The information was limited to the department’s current and future skills and competencies. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

◐ |

VA provided the VA Office of Information Technology Strategic Workforce Plan, for fiscal years 2024 to 2028. However, the department’s analysis was incomplete in that it did not comprehensively identify VA’s current and future human capital needs, skills, and competencies. |

|

Practice 3.2: Develop a cybersecurity workforce plan that includes strategies to close the cybersecurity gaps, such as recruiting, training, retraining, restructuring, use of contractors, succession planning, and technological enhancements. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not provide a cybersecurity workforce action plan that included strategies to close cybersecurity gaps, such as recruiting, training, retraining, restructuring, use of contractors, succession planning, and technological enhancements. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS provided a cybersecurity workforce implementation plan and an annual report on cybersecurity work roles of critical need, including strategies to close cybersecurity gaps, such as recruiting, training, and retention incentives. |

|

HHS |

◐ |

HHS provided some documentation of recruiting and retention incentive strategies intended to address cybersecurity workforce gaps, such as using hiring flexibilities and student loan repayment. However, HHS did not provide a cybersecurity workforce action plan that included strategies to close cybersecurity gaps, such as recruiting, training, retraining, restructuring, use of contractors, succession planning, and technological enhancements. |

|

Treasury |

○ |

Treasury did not provide a cybersecurity workforce action plan that included strategies to close cybersecurity gaps, such as recruiting, training, retraining, restructuring, use of contractors, succession planning, and technological enhancements. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided its Office of Information and Technology strategic workforce plan that mentioned strategies to close cybersecurity gaps such as the use of special salary rate,a a succession planning program, and an apprenticeship program. The plan also referenced participation in the Cyber NextGen Development Program. However, the plan did not include details regarding the strategies listed. |

|

Practice 3.3: Develop a cybersecurity workforce action plan with metrics to evaluate success and achievement of desired results. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not have a cybersecurity action plan with metrics to evaluate success and achievement of desired results. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS provided a cybersecurity workforce implementation plan and an annual report on cyber work roles of critical need with workforce metrics to evaluate success and achievement of desired results. |

|

HHS |

○ |

HHS did not have a cybersecurity action plan with metrics to evaluate success and achievement of desired results. |

|

Treasury |

◐ |

Treasury provided some cybersecurity workforce metrics to evaluate success, such as baseline and target attrition rates and average time to hire. The documentation was not specifically dedicated to Treasury’s cybersecurity workforce; it targeted mission critical occupations, which included IT and cybersecurity-related occupational series. However, these metrics were only projected for 1 year (fiscal year 2024). |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided documentation that included some cybersecurity metrics to evaluate success and achievement of desired results such as time to hire, executive fill rates, and retention rates. VA used milestones to monitor its achievement of workforce goals; however, the department did not provide any other workforce metrics. |

Legend: ● Fully implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated all aspects of the selected applicable practices;

◐ Partially implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated some, but not all, aspects of the selected applicable practices;

○ Not implemented = departments did not provide any documentation, or if documentation was provided, it did not demonstrate any aspect of the selected applicable practices.

Source: GAO analysis of department IT workforce planning policies and documentation. | GAO‑25‑106795

aThe Special Salary Rate is paid to VA employees in General Schedule (GS) positions at grades GS-5 to GS-15 across the 2210, 1550, and 0854 occupational series, unless an employee is entitled to receive a higher GS locality rate of pay.

Most Departments Did Not Fully Implement and Monitor Action Plans

DHS implemented all three applicable practices, but the other four departments did not. Specifically:

· VA partially implemented three practices;

· Treasury partially implemented once practice; and

· Commerce and HHS did not implement any practices.

Table 5 provides a detailed assessment of the completeness of departments’ efforts to implement and monitor their workforce action plans.

Table 5: Assessment of Five Selected Departments’ Implementation of Selected Applicable Practices for Step Four: Implement and Monitor the Workforce Action Plan

|

Department |

Rating |

GAO assessment |

|

Practice 4.1: Communicate the cybersecurity workforce action plan to the agency’s leadership; plan and implement a communication strategy that defines roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not provide documentation of communicating a cybersecurity workforce action plan to the department’s leadership. Commerce officials also did not provide a plan and implement a communication strategy that defined roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

|

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

● |

DHS communicated the cybersecurity workforce action plan to the department’s leadership; and planned and implemented a communication strategy that defined roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

○ |

HHS did not provide documentation of communicating a cybersecurity workforce action plan to the department’s leadership. HHS officials also did not provide a plan and implement a communication strategy that defined roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

|

Treasury |

◐ |

Treasury provided some documentation of communicating cybersecurity workforce planning to the department’s leadership. Specifically, Treasury provided a human capital operating plan that included some evidence of communicating and coordinating roles including those for the department’s mission critical occupations such as IT and cybersecurity-related occupational series. Treasury did not provide a plan and implement a communication strategy that defined roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

◐ |

VA provided some documentation of communicating cybersecurity workforce action planning to the department’s leadership. Specifically, VA provided an Office of Information and Technology strategic workforce plan that included documentation regarding workforce communication. VA did not provide a plan and implement a communication strategy that defined roles, resources, and achievement of strategic objectives. |

|

Practice 4.2: Develop a plan that describes how implementation will occur, including information on key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not develop a plan that described how implementation will occur, including information on key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS provided a cybersecurity workforce implementation plan and described how implementation will occur, including information on key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

|

HHS |

○ |

HHS did not develop a plan that described how implementation will occur, including information on key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

|

Treasury |

○ |

Treasury did not develop a plan that described how implementation will occur, including information on key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided documentation that discussed implementation of the agency’s workforce activities; however, this documentation did not describe how VA would implement its cybersecurity workforce action plan, including key deliverables, timelines, responsibilities, and needed resources. |

|

Practice 4.3: Implement and monitor the cybersecurity workforce action plan, including discussing the plan at the department dashboards and includes information on how the milestones, metrics, and targets from the cybersecurity workforce action plan are being tracked. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not implement and monitor the cybersecurity workforce action plan, including discussing the plan at the department dashboards nor included information on how the milestones, metrics, and targets from the cybersecurity workforce action plan were being tracked. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS implemented and monitored the cybersecurity workforce action plan, including discussing the plan at the department dashboards and included information on how the milestones, metrics, and targets from the cybersecurity workforce action plan were being tracked. |

|

HHS |

○ |

HHS did not implement and monitor the cybersecurity workforce action plan, including discussing the plan at the department dashboards nor included information on how the milestones, metrics, and targets from the cybersecurity workforce action plan were being tracked. |

|

Treasury |

○ |

Treasury did not implement and monitor the cybersecurity workforce action plan, including discussing the plan at the department dashboards nor included information on how the milestones, metrics, and targets from the cybersecurity workforce action plan were being tracked. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided documentation that discussed the workforce status at the department’s dashboards. The information included discussions on milestones, metrics, and targets for the workforce. However, the department did not provide evidence of it implementing and monitoring the cybersecurity workforce action plan. |

Legend: ● Fully implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated all aspects of the applicable practice;

◐ Partially implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated some, but not all, aspects of the applicable practice;

○ Not implemented = departments did not provide any documentation, or if documentation was provided, it did not demonstrate any aspect of the applicable practice.

Source: GAO analysis of department IT workforce planning policies and documentation. | GAO‑25‑106795

Departments Did Not Fully Evaluate and Revise Action Plans

None of the five selected departments fully evaluated and revised their cybersecurity workforce action plans. Specifically, of the three applicable practices:

· DHS fully implemented two practices;

· VA partially implemented one practice; and

· Commerce, HHS, and Treasury did not fully implement any practices.

Table 6 provides a detailed assessment of the completeness of departments’ efforts to evaluate and revise their workforce action plans.

Table 6: Assessment of Five Selected Departments’ Implementation of Selected Applicable Practices for Step Five: Evaluate and Revise the Workforce Action Plan

|

Department |

Rating |

GAO assessment |

|

Practice 5.1: Assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

|

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

● |

DHS assessed the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

○ |

HHS did not assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

|

Treasury |

○ |

Treasury did not assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

○ |

VA did not assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the cybersecurity workforce action plan and the progress made against its targets, baselines, outcomes, and performance measures. |

|

Practice 5.2: Record actions taken, review lessons learned from its cybersecurity workforce action plan, and update or adjust metrics and targets as necessary. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not record actions taken, review lessons learned from its cybersecurity workforce action plan, nor update or adjust metrics and targets as necessary. |

|

DHS |

◐ |

DHS provided documentation of actions taken from its cybersecurity workforce action plan, and updated metrics and targets, specifically, for its cybersecurity work roles of need. However, the documentation did not include evidence of reviewing lessons learned. |

|

HHS |

○ |

HHS did not record actions taken, review lessons learned from its cybersecurity workforce action plan, nor update or adjust metrics and targets as necessary. |

|

Treasury |

○ |

Treasury did not record actions taken, review lessons learned from its cybersecurity workforce action plan, nor update or adjust metrics and targets as necessary. |

|

VA |

○ |

VA did not record actions taken, review lessons learned from its cybersecurity workforce action plan, nor update or adjust metrics and targets as necessary. |

|

Practice 5.3: Conduct an analysis of the extent to which cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives are being achieved. |

||

|

Commerce |

○ |

Commerce did not conduct an analysis of the extent to which cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives were being achieved. |

|

DHS |

● |

DHS conducted an analysis of the extent to which cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives were being achieved. |

|

HHS |

○ |

HHS did not conduct an analysis of the extent to which cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives were being achieved. |

|

Treasury |

○ |

Treasury did not conduct an analysis of the extent to which cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives were being achieved. |

|

VA |

◐ |

VA provided some analyses documentation of the extent to which its cybersecurity workforce strategic objectives were being achieved; however, it was limited in scope to analyzing employee retention concerns. |

Legend: ● Fully implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated all aspects of the applicable practice;

◐ Partially implemented = departments’ documentation demonstrated some, but not all, aspects of the applicable practice;

○ Not implemented = departments did not provide any documentation, or if documentation was provided, it did not demonstrate any aspect of the applicable practice.

Source: GAO analysis of department information technology workforce planning policies and documentation. | GAO‑25‑106795

According to officials at three of the five selected departments, they did not fully implement the selected practices because they were managing their cybersecurity workforces at the individual component level rather than at departmental level. Selected departments noted other reasons for not fully implementing the selected applicable practices.

· Commerce. According to Commerce officials, the department did not have a departmental-led cybersecurity workforce governance, instead, each individual Commerce components’ Chief Information Security Officer was responsible for the planning and analysis of the component’s cybersecurity workforces. In addition, according to Commerce officials, given the timing of this review, the department was not able to issue a data call in which all of its individual components were able to support an overall departmental response.

· DHS. According to DHS officials, their review revealed a gap between specialty operational workforce planning and overarching DHS cybersecurity workforce planning. DHS officials also stated that the department was committed to working with key stakeholders to identify lessons learned and affirm the overarching cybersecurity workforce action plan.

· HHS. HHS officials stated that while the department followed OPM’s guidance to implement workforce planning processes, it did not have a strategic plan specifically for the department’s cybersecurity activities. HHS officials also stated a department-level cybersecurity workforce management strategic plan and business plan would be developed in 2024.

· Treasury. Treasury officials stated the department’s workforce strategy was decentralized and individually handled by the department’s individual components. Treasury officials also stated that Treasury’s recruitment gap size and retention rate did not warrant a gap closure strategy, action plan, and implementation plan.

· VA. VA officials stated that while the department’s Office of Information Technology developed several workforce-related documents, a specific cybersecurity workforce strategy had yet to be developed. VA officials add that they have taken the opportunity to use the insight provided in the OPM guide to assist in the creation of a new VA Workforce Strategy, which is intended to identify goals surrounding talent acquisition, workforce planning, competencies, and collaboration with other departments. VA completed this strategy in October 2024, and we updated our analysis accordingly; however, several workforce planning practices were still not fully implemented.

Until the departments implement all the selected applicable practices for their cybersecurity workforces, they will be challenged in having cybersecurity workforces with the necessary skills to protect federal IT systems and enable the government’s day-to-day functions.

Most Departments Took Steps to Mitigate Identified Workforce Challenges, but No Departments Evaluated Their Actions

Officials at the five selected departments cited three primary types of cybersecurity workforce management challenges: inadequate funding, difficulties with recruitment, and challenges with retention. Within these three primary types, officials identified six specific challenges. Each of these was reported by at least two departments. To mitigate these challenges, department officials described actions, both underway and planned. However, none of the departments evaluated their actions to determine whether they were effective in addressing their cybersecurity workforce management challenges.

Selected Departments Identified Cybersecurity Workforce Challenges

Table 7 shows the three key types and six specific cybersecurity workforce challenges identified by department officials:

|

|

Departments |

||||

|

Challenge type |

Commerce |

DHS |

HHS |

Treasury |

VA |

|

Inadequate funding for the cybersecurity workforce |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pay disparity between federal agencies and the private sector |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Department budget limitations |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Difficulties with recruiting the cybersecurity workforce |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maintaining an adequate cybersecurity workforce |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Cybersecurity workforce candidates |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

|

Recruiting processing |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Challenges with retaining the cybersecurity workforce |

|

|

|

|

|

|

High attrition due to cybersecurity employees choosing different career paths |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

|

Totals challenges by departments |

5 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

Legend: ✓ = Department faced challenge; ✗ = Department did not face challenge

Source: GAO analysis of department documentation. | GAO‑25‑106795

Inadequate Funding for the Cybersecurity Workforce

Officials from all five departments stated they faced challenges in inadequate funding for their cybersecurity workforces.

· Commerce, DHS, HHS, Treasury, and VA reported that pay disparity between federal agencies and the private sector was a challenge. Many of the departments stated that it was difficult to recruit and retain employees, especially highly qualified candidates. For instance, staff from VA reported that existing salaries within certain geographic regions were not competitive with private sector salaries, even when combined with VA’s compensation incentives and benefits.

· Staff from DHS, HHS, Treasury, and VA noted that department cybersecurity workforce budget limitations caused recruiting and retention complications.

Difficulties with Recruiting the Cybersecurity Workforce

Officials from all five selected departments stated that their departments faced difficulties with recruiting their cybersecurity workforces.

· Officials at Commerce, DHS, and VA stated it was difficult to maintain an adequate cybersecurity workforce. For example, Commerce reported that it experienced a shortage of cybersecurity workforce personnel, specifically for its 2210 Information Technology series positions.

· Officials at Commerce, DHS, HHS, and Treasury stated they had difficulties with recruiting cybersecurity workforce candidates. For example, DHS reported that since COVID-19, open cybersecurity position announcements for its U.S. Secret Service component no longer generated enough well-qualified applicants, thus resulting in a decreased talent pool of qualified cybersecurity candidates.

· Officials at Commerce, DHS, HHS, and VA stated that they experienced difficulties with recruitment processing. For example, VA reported that the lengthy time-to-hire cybersecurity personnel for vacant positions impacted its overall ability to deliver products and services.

Challenges with Retaining the Cybersecurity Workforce

Officials from all five selected departments stated that their departments faced difficulties with retaining their cybersecurity workforces. Specifically:

· Officials at Commerce and HHS reported challenges with high attrition due to cybersecurity employees choosing different career paths. For example, Commerce noted that cybersecurity employees would leave the department to choose a different career path or a job closer to home. HHS reported that cybersecurity trained staff were able to easily move through the federal government due to their essential skillset.

Selected Departments Took Actions to Mitigate Cybersecurity Workforce Challenges

Officials from all five

selected departments stated that their departments identified mitigating

actions to address each of the three cybersecurity workforce challenge types.

Inadequate Funding for the Cybersecurity Workforce

Officials from all five of the selected departments developed mitigation actions in response to their challenges with inadequate funding for their cybersecurity workforces. The following provides key examples:

· In response to the pay disparity between the federal agencies and the private sector, officials from the selected departments described mitigating actions. For example, Commerce officials reported that the department temporarily promoted employees in its competitive service and leveraged various authorities to hire cybersecurity professionals for special projects. Officials at DHS and HHS stated that their departments offered incentives such as student loan repayment. DHS officials also noted that the department offered market-sensitive pay for cybersecurity personnel. HHS officials stated the department offered higher starting salaries based on superior skills and qualifications. Treasury officials stated the department offered cash awards to cybersecurity personnel. VA officials stated the department offered special salary rates for IT and cybersecurity personnel.

· To address department cybersecurity workforce funding and budget limitations, officials from the selected departments described mitigating actions. For example, DHS reported that the U.S. Secret Service used all available hiring authorities, including special hiring authority and veteran hiring authority. DHS officials stated the department contracted support to assist with recruitment and retention activities. HHS officials stated the department provided human resources support and funding for additional human resources personnel. Treasury officials stated the department created workforce demand projections beyond the time frames of the current budget cycle to be better prepared for its future workforce needs.

Difficulties with Recruiting the Cybersecurity Workforce

Officials from selected departments developed mitigation actions in response to their challenges with difficulties recruiting their cybersecurity workforces. The following provides key examples:

· To address the difficulty of maintaining an adequate cybersecurity workforce, officials from the selected departments described mitigating actions. For example, Commerce officials stated the department planned to leverage various hiring authorities to hire cybersecurity professionals for special projects and considered using special salary rates for the 2210 occupational series positions to expand its cybersecurity workforce. DHS officials reported the department’s U.S. Secret Service component used all available hiring authorities, including special hiring authority and veteran hiring authority. VA officials reported that the department’s Office of People Science continuously updated and analyzed VA personnel recruitment data to identify obstacles to recruiting and addressed delays to reduce the overall time to hire.

· To address difficulties with recruiting cybersecurity workforce candidates, officials from the selected departments described mitigating actions. For example, Commerce officials reported the department expanded the talent pool for its cybersecurity workforce positions to include both internal and external candidates. DHS reported that U.S. Secret Service used, in addition to addressing this challenge through contracted support, all available hiring authorities, including special hiring authority and veteran hiring authority. HHS officials noted the department used the federal government’s Pathways Program to hire recent IT graduates for the department’s cybersecurity positions, in addition to participation in the Office of Personnel Management’s Tech to Gov recruitment events. Treasury officials reported that the department dedicated $1.1 million dollars for talent outreach to recruit for cybersecurity roles and other occupations.

· With respect to recruitment processing issues, officials from the selected departments described mitigating actions. For example, Commerce officials reported the department launched an 80-day time-to-hire dashboard that allowed managers to track how long it took the department to onboard IT employees. DHS officials reported that the department used its Cybersecurity Talent Management System (CTMS) for dissemination of broad recruiting announcements rather than posting for specific positions. HHS officials reported the department addressed recruitment processing challenges by using direct hire authority, a focus on reducing the amount of time it took to obtain security clearances, identification of efficiencies to process candidates requesting pay based on superior qualifications, and implementation of a workforce planning center of practice. VA officials reported that the department’s Office of People Science continuously updated and analyzed personnel recruitment data to identify obstacles to recruiting and addressed delays to reduce the department’s overall time to hire.

Challenges with Retaining the Cybersecurity Workforce

Officials from all five of the selected departments developed mitigation actions in response to their challenges with retaining their cybersecurity workforces. The following provides key examples:

· In response to the higher attrition due to cybersecurity employees choosing different career paths, officials from the selected departments described mitigating actions. For example, Commerce officials stated that the department offered temporary promotions with pay increase, opportunities for details across Commerce, and training opportunities. HHS officials stated that the department implemented a department-wide detail program and planned to provide HHS cybersecurity personnel with 6-month to 1-year rotations in cybersecurity positions in other departments.

None of the Selected Departments Evaluated the Effectiveness of their Mitigation Actions

OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide and Model emphasizes that agencies should develop, monitor, evaluate, and revise a workforce action plan.[28] Further, our report on key principles of strategic workforce planning noted that periodic measurement of an agency’s progress toward human capital goals and the extent of human capital activities provides information for identifying performance shortfalls.[29] Our report also stated workforce planning should be done at the departmental level.

However, none of the five selected departments evaluated the effectiveness of their mitigation actions in response to the identified workforce challenges. Officials from HHS, Treasury, and VA reported that they had not evaluated the effectiveness of their efforts. Commerce officials reported that the department monitors the effectiveness of its actions to respond to cyber workforce challenges but did not provide evidence to support these assertions. DHS officials reported that they plan to develop a strategy to measure the effectiveness of their efforts but did not provide a plan or time frame for doing so.

Without evaluating the effectiveness of their mitigation actions, agencies will not know the extent to which their actions are addressing challenges and helping to meet cybersecurity workforce goals.

Conclusions

Building and maintaining a cybersecurity workforce by addressing mission critical skills gaps is one of the federal government’s most important challenges, as well as a national security priority. While DHS fully implemented almost all selected leading workforce management practices, the other four reviewed departments fully implemented less than half. Addressing these practices from a department-level perspective can help ensure that their cybersecurity workforces have the necessary skills and capabilities to protect federal IT systems and enable the government’s day-to-day functions.

Selected departments have proactively identified challenges and implemented mitigation strategies and associated actions to strengthen their cybersecurity workforces. However, because the departments have not evaluated the effectiveness of their actions, officials do not know the extent to which their departments’ cybersecurity workforce issues have been addressed and their cybersecurity postures have been strengthened.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 23 recommendations to the five selected departments.

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Department of Commerce fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with conducting workforce analyses. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Department of Commerce fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with developing a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Department of Commerce fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with implementing and monitoring a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Department of Commerce fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with evaluating and revising a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Department of Commerce identify and analyze the effectiveness of its mitigation actions on the cybersecurity workforce challenges. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Department of Homeland Security fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with evaluating and revising a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Department of Homeland Security identify and analyze the effectiveness of its mitigation actions on the workforce challenges. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with setting the strategic direction for the cybersecurity workforce. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with conducting workforce analyses. (Recommendation 9)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with developing a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 10)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with implementing and monitoring a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 11)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with evaluating and revising a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 12)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services identify and analyze the effectiveness of its mitigation actions on the cybersecurity workforce challenges. (Recommendation 13)

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Department of the Treasury fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with conducting workforce analyses. (Recommendation 14)

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Department of the Treasury fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with developing a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 15)

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Department of the Treasury fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with implementing and monitoring a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 16)

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Department of the Treasury fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with evaluating and revising a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 17)

The Secretary of the Treasury should ensure that the Department of the Treasury identify and analyze the effectiveness of its mitigation actions on the cybersecurity workforce challenges. (Recommendation 18)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should ensure that the Department of Veterans Affairs fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with conducting workforce analyses. (Recommendation 19)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should ensure that the Department of Veterans Affairs fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with developing a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 20)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should ensure that the Department of Veterans Affairs fully addresses the practices described in our report associated with implementing and monitoring a workforce action plan. (Recommendation 21)