PRIVATE HEALTH PLANS

Comparison of Employer-Sponsored Plans to Healthcare.gov Marketplace Plans

Report to the Chairwoman

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

November 2024

GAO-25-106798

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106798. For more information, contact John E. Dicken at (202) 512-7114 or dickenj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106798, a report to the Chairwoman of the Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives

November 2024

PRIVATE HEALTH PLANS

Comparison of Employer-Sponsored Plans to Healthcare.gov Marketplace Plans

Why GAO Did This Study

Private health plan spending is projected to exceed $1.5 trillion in 2024. This has financial implications for enrollees, who pay for either all or part of their premiums; for employers who typically contribute to employees’ premiums costs; and for the federal government, which provides tax incentives and other financial support for Marketplace and employer-sponsored plans.

GAO was asked to compare employer-sponsored plans to Marketplace plans. In this report, GAO describes, among other objectives, how average employer-sponsored plan premiums compared to Marketplace plans; and how average cost sharing to consumers in employer-sponsored plans compared to that of Marketplace plans.

GAO reviewed Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component data on employer-sponsored plans and CMS Marketplace individual market plan data to estimate enrollment-weighted average premiums and cost sharing in 2022 in 33 states. These states were selected because they used the Healthcare.gov platform in 2022 (the most recent year of data available at the time of the review); thus, complete and comparable data were available for Marketplace plans across those states. Additionally, GAO interviewed officials from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, CMS, the Department of the Treasury, and representatives from six stakeholder groups, such as those representing insurers and policy researchers, selected to reflect a range of expertise on the topics under review.

What GAO Found

Most Americans get their health coverage from private health plans. In 2023, about 165 million individuals got their health coverage from an employer plan and 16.3 million got their coverage from plans purchased through Marketplaces established through the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

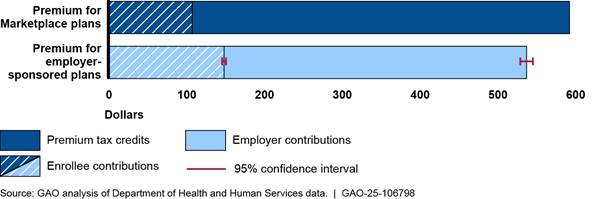

One of the costs for private health plans is the premium that needs to be paid for enrollment. GAO compared monthly premiums per covered individual for employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality survey data and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Marketplace data, respectively. GAO found that for the 33 states included in its review (those that used the Healthcare.gov platform), in 2022, the estimated average monthly premiums for employer-sponsored plans were lower than the average premiums for Marketplace plans. However, stakeholders noted that differences in covered populations, such as in health status, complicate comparability of premiums between these two types of plans. Additionally, after employer contributions to employee premiums and federal premium tax credits for Marketplace plans, the average estimated monthly enrollee contributions to premiums per covered individual for employer-sponsored plans were higher than the average enrollee contributions to premiums for Marketplace plans. Taxes complicate comparability because enrollee contributions to employer-sponsored plans do not reflect their cost after tax savings.

Note: Enrollee contributions to premiums for employer-sponsored health plans are made with pre-tax dollars, which results in tax savings for enrollees. Enrollee contributions to premiums for Marketplace plans are generally made with after-tax dollars.

Premiums for both employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans varied across the 33 states in 2022. In addition, for employer-sponsored plans, they varied by industry and for Marketplace plans they varied by tier of coverage.

GAO found that differences in plan designs complicated comparisons of cost sharing across plans. For example, in 2022, estimated average deductibles for employer-sponsored plans were lower than for Marketplace plans, but GAO estimated that a higher percentage of Marketplace plan enrollees were in plans with no deductible.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

|

AV |

actuarial value |

|

CI |

confidence interval |

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

CSR |

cost-sharing reduction |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

MEPS-IC |

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component |

|

PPACA |

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 27, 2024

The Honorable Virginia Foxx

Chairwoman

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

Dear Madam Chairwoman,

Most Americans get their health coverage from private health plans, including employer-sponsored plans and plans purchased on the individual market. In 2023, an estimated 165 million non-elderly individuals had coverage sponsored by employers and 16.3 million individuals were covered by plans purchased through health insurance exchanges—or Marketplaces—established through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA).[1] According to national estimates from the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), private health plan spending is projected to exceed $1.5 trillion in 2024. This spending has financial implications for (1) private health plan enrollees who pay for either all or part of their health plan premiums, (2) the many employers that sponsor plans and contribute to their employees’ premiums, and (3) the federal government, which provides different forms of federal financial support for both employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans, including through tax exclusions and tax credits. Because of this, there is interest in understanding how employer-sponsored and Marketplace plan premiums compare and who bears those costs. There is also interest in understanding how these plans compare in terms of the amounts plan enrollees are expected to pay for the services they use, which is referred to as cost sharing, as well as the benefits these plans cover.[2]

In addition to interest in comparing the costs and benefits of employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans, there is interest in understanding how changes in the financing for cost-sharing reductions (CSR) that insurers are required to offer to certain low-income Marketplace enrollees affected Marketplace enrollees. Initially, in 2014, the federal government reimbursed issuers for these CSRs. But beginning in 2018, the federal government stopped paying these reimbursements and the responsibility to fund them shifted to issuers.

You asked us to compare employer-sponsored plans to Marketplace plans. In this report, we describe

1. how average premiums of employer-sponsored plans compare to that of Marketplace plans;

2. how cost sharing and certain plan benefits offered in employer-sponsored plans compare to that of Marketplace plans; and

3. how the loss of federal payments for CSRs affected Marketplace enrollees.

To describe how the average premiums, cost sharing, and plan benefits of employer-sponsored plans compare to that of Marketplace plans, we used data from two units of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). For employer-sponsored plans, we used survey data from HHS’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) as a basis for creating our own estimates of the various plan elements included in our analysis.[3] For Marketplace plans, we used administrative data on individual market plans from CMS, the agency within HHS responsible for overseeing the establishment of these Marketplaces.[4] Our analyses used data from 2022, the most current available data at the time of our review. Complete CMS data were available only for the 33 states that used the federal Healthcare.gov platform in 2022, so for both employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans we generally limited our review to those 33 states.[5] To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation and discussed our methodologies with agency officials. Based on this work, we determined that the data were reliable for the purposes of describing how premiums, cost sharing, and benefits of employer-sponsored plans compare to that of Marketplace plans.

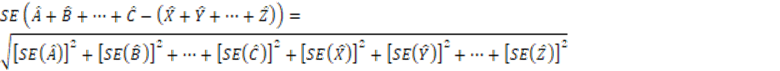

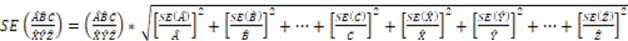

As part of the first objective, for our analyses of premiums for employer-sponsored plans, we created enrollment-weighted estimates across the 33 selected states based on publicly available MEPS-IC tabular state-level survey data.[6] Our estimates included average monthly premium and enrollee contributions to premiums for three coverage types (single, employee-plus-one, and family), weighted by the proportion of enrolled employees in each state. We also used the MEPS-IC data to estimate employer-sponsored premiums and enrollee contributions to premiums per covered individual. We did so by combining data from all three of these coverage types to allow a comparison to the Marketplace premium data which are reported at the per covered individual level. Because the MEPS-IC does not collect data on the total number of covered individuals on a family coverage plan, we used 2022 U.S. Census Bureau (Census) household data to approximate the number of covered individuals in each employer-sponsored family policy—resulting in an estimate of 3.83 covered lives per family policy, with an associated 95 percent confidence interval (CI) of 3.70-3.96. We used this estimate as a proxy for the average number of covered individuals per family coverage plan, which we used in calculating average premiums and enrollee contributions to premiums per covered individual across the 33 states. All results of our analysis based on the MEPS-IC data include an associated 95 percent CI to take account of survey sampling error.

Additionally, for the first objective’s analyses of premiums and enrollee contributions to premiums for Marketplace plans, we used CMS data from the Open Enrollment Period Public Use files, which are reported as averages per covered individual.[7] These files include data on per covered individual average monthly premiums, average monthly advance premium tax credits, and average monthly enrollee contributions to premiums for plans in the bronze, silver, and gold metal tiers, as well as for the platinum and catastrophic tiers that we did not include in our analysis.[8] Average contributions to premiums per covered individual included in these files are the monthly premiums minus monthly advance premium tax credits received toward that premium.[9] We calculated an overall average Marketplace plan premium and enrollee contributions to premiums across the three metal tiers, weighting the averages per tier by the proportion of covered individuals in each tier.

For our analysis of cost sharing and plan benefits, we selected cost-sharing elements that were present in both the MEPS-IC survey data and CMS Marketplace data. The cost-sharing elements we analyzed were individual in-network deductible; individual in-network out-of-pocket maximum; and average in-network copay and coinsurance for provider services (a general doctor visit and a specialist visit) and prescription drugs (generic, preferred, non-preferred, and specialty).[10] The benefits we analyzed were mental health care and substance abuse treatment.[11] For employer-sponsored plans, we used the MEPS-IC data to estimate enrolled employee-weighted average individual deductibles, individual out-of-pocket maximums, copays, coinsurance, and benefit coverage, weighted across the 33 states based on the number of enrolled employees in each state.[12] For Marketplace plans we used CMS health insurance Marketplace public use files, together with plan variant enrollment-level data obtained from CMS, to calculate enrollment-weighted average cost sharing and plan benefits.[13]

To describe how the loss of federal payments for CSRs affected Marketplace enrollees, we conducted a literature search to identify papers published from January 2019 through September 2023 that focused on this issue. We also analyzed CMS Open Enrollment Period Public Use data from 2017 and 2018, the year prior to and the first year during the loss of federal payments for CSRs. We used these data to describe changes in average premiums and premium tax credits per covered individual across these two years for the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, as of 2022.

To inform all of our findings, we interviewed officials from AHRQ, CMS, the Department of the Treasury, and representatives from six organizations selected to reflect a range of expertise on the topics under review. Specifically, we spoke with organizations representing insurers, employers, insurance regulators, actuaries, and health policy researchers. See appendix I for additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Private health plans are the most common source of health coverage in the United States—covering approximately two-thirds of adults in 2023, according to HHS. Private health plans include, but are not limited to, employer-sponsored coverage and coverage offered through Marketplace plans. Health plan coverage reduces an enrollee’s costs for covered services when medical treatment is needed. Health plans do so by paying an agreed upon amount to the facilities, health care providers, and suppliers that a health plan has contracted with—referred to as the health plan’s network. Plans may also pay for services obtained outside of their network but at a higher cost to enrollees. Premiums are the amount—typically billed monthly—paid for health coverage.[14] In addition to premiums, plan cost-sharing elements, including deductibles, out-of-pocket maximums, copayments (copays), and coinsurance, can also affect an enrollee’s final cost for a health visit or procedure. See text box for definitions of key elements of a health plan discussed in this report.

|

Glossary of Key Terms Coinsurance: The percentage of costs of a covered health care service the enrollee pays (20 percent, for example) often after the deductible has been reached. Covered services typically have either a copay or coinsurance. Copay: A fixed amount ($20, for example) the enrollee pays for a covered health care service, often after the deductible has been reached. Covered health care service: A service that the health plan will pay for (in part or in full) on behalf of enrollees. Deductible: The amount the enrollee pays for certain covered health care services before the plan starts to pay. With a $2,000 deductible, for example, enrollees pay the first $2,000 for covered services, after which they usually pay only a copay or coinsurance for covered services. The plan pays the rest. For all Marketplace plans and most employer-sponsored plans, certain preventive services are covered in full before the deductible is met. In-network: Health care providers or health care facilities that have a contract with a health plan to provide health care services to its plan members. Out-of-pocket maximum: The most an enrollee pays for covered medical expenses in a plan year. The structure of an out-of-pocket maximum can vary by plan. For example, in some plans, out-of-network care may not apply to the out-of-pocket maximum or may result in a higher out-of-pocket maximum. Plan benefits: The health care items or services covered under a health plan. Premium: The amount paid to maintain health coverage. Premiums are typically paid monthly. |

Source: GAO analysis of Healthcare.gov and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services terms. | GAO‑25‑106798

Employer-Sponsored Health Plans

Many employers sponsor group health plans for their employees.[15] Eligibility for this group coverage is limited to individuals who are part of the group, by virtue of either their own employment or their relationship to an employee (e.g., the spouse or children of an employee, to the extent a sponsor makes the group plan available to family members). Payers for group plans generally include both the employers and employees, with each paying a share of the premium.[16]

Federal support for employer-sponsored plans is provided through various tax benefits. The employer’s share of the premiums for these plans is excluded from their employees’ gross income so it is not subject to federal income or payroll taxes (mainly for Social Security and Medicare). In addition, the employee’s share of premiums is also excluded from their taxable wages and therefore not subject to federal income or payroll taxes. Because tax rates vary, the amount of forgone tax revenue for employer-sponsored plans varies depending on employee income. See table 1 for illustrative costs of forgone federal tax revenue for individuals with different income levels in 2022. (We use 2022 for these examples to be consistent with the year of the analyses used to inform the findings of this report.)

|

|

Individual annual taxable income, Single filer in 2022 (top marginal tax rate) |

||||

|

|

$30,000 (12%) |

$75,000 (22%) |

$160,000 |

$300,000 (35%) |

$600,000 |

|

Forgone employee income tax |

$720 |

$1,320 |

$1,440 |

$2,100 |

$2,220 |

|

Forgone Social Security taxa |

$744 |

$744 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

Forgone Medicare taxb |

$174 |

$174 |

$174 |

$228 |

$228 |

|

Total forgone federal tax revenue |

$1,638 |

$2,238 |

$1,614 |

$2,328 |

$2,448 |

|

Forgone federal tax revenue as a percentage of total premium ($6,000) |

27% |

37% |

27% |

39% |

41% |

Source: GAO analysis based on Internal Revenue Service information. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: For the purposes of this table, the assumption is that health plans are offered and premiums are treated like the last dollars of income received, so we reflect the top marginal tax rates that would apply to the health plan premium if it was counted as taxable income.

aIncome above a certain amount is not subject to Social Security tax. As a result, there was no Social Security tax reduction for income above $147,000 in 2022.

bBeginning in 2013, Medicare taxes increased by 0.9 percent for some taxpayers, including single filers, for incomes above $200,000.

Based on tax expenditure estimates by the Department of the Treasury, the federal cost for the exclusion of employer-sponsored health plans was approximately $361.5 billion for 2022.[17]

Marketplace Plans

Since 2014, millions of consumers have purchased health plans through the Marketplaces.[18] These consumers purchase a health plan through the Marketplaces for a variety of reasons, including being unemployed, self-employed, or employed by an employer that does not offer a health plan. PPACA requires insurance companies (or issuers) to market certain plans, including individual market plans, according to defined categories (known as metal tiers) that indicate the extent to which the plans would be expected to cover the costs of consumers’ medical care.[19] PPACA also established requirements for the benefits that must be covered by Marketplace health plans—referred to as essential health benefits.[20]

In addition to codifying how Marketplace plans were marketed and the minimum essential benefits they must cover, PPACA also established premium tax credits and CSRs that are available to some Marketplace consumers to help them afford their coverage.

Premium tax credits. Most Marketplace consumers in 2022 were eligible for federal premium tax credits that reduce the amount they contribute towards their premium. Based on tax expenditure estimates by the Department of the Treasury, the federal cost for premium tax credits in 2022 was approximately $76.3 billion.[21] The amount of the premium tax credit varies based on household income and the cost of a benchmark plan (the second lowest-cost silver plan available to the consumer).[22] The credit limits what the consumer would pay for that plan to be no more than a certain percentage of their household income. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 made temporary changes to premium tax credits by expanding eligibility to higher-income individuals and increasing premium tax credits for lower-income individuals for tax years 2021 and 2022.[23] For example, the law increased the premium tax credit amounts for eligible individuals and families, resulting in access to plans with no premium contributions for those earning 100 to 150 percent of the federal poverty level. It also expanded eligibility for premium tax credits to include certain individuals and families with incomes at or above 400 percent of the federal poverty level. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 extended these provisions through the end of tax year 2025.[24] See table 2.

|

Percent of federal poverty level |

Maximum percentage of annual household income paid for premiums in second lowest-cost silver plan, 2020 |

Temporary maximum percentage of annual household income paid for premiums in second lowest-cost silver plan, 2024a |

|

At least 100 up to 150b |

2.07-4.14 |

0.0 |

|

At least 150 up to 200 |

4.14-6.52 |

0.0–2.0 |

|

At least 200 up to 250 |

6.52-8.33 |

2.0–4.0 |

|

At least 250 up to 300 |

8.33-9.83 |

4.0–6.0 |

|

At least 300 up to 400 |

9.83 |

6.0–8.5 |

|

At least 400 and higher |

100 |

8.5 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Health and Human Services data. | GAO‑25‑106798

aThese percentages are temporary. The temporary percentages were established in 2021 and extended through 2025.

bPremium tax credits are generally only

available for households with incomes at or above 100 percent of the federal

poverty level. Lawfully present immigrants with incomes less than 100 percent

of the federal poverty level may receive premium tax credits if they are

ineligible for Medicaid based on immigration status.

Premiums for Marketplace plans can vary by age, with premiums being up to three times higher for older consumers than for younger consumers in most states.[25] In addition, different premium amounts are established for each rating area in the United States (which are often aligned with counties), so each rating area has its own benchmark plan.

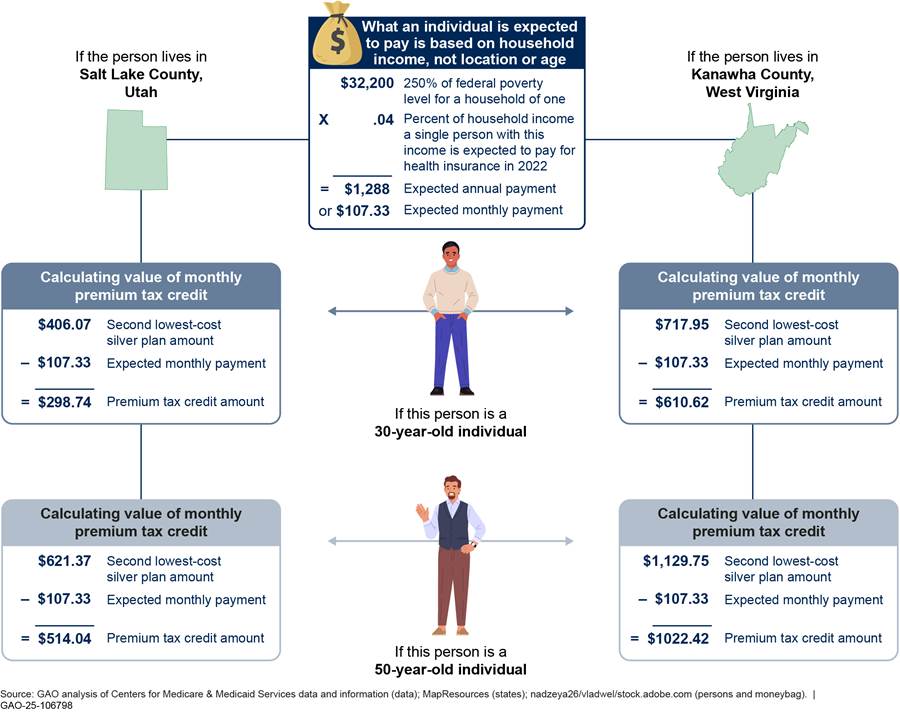

As a result, the formula used to calculate the premium tax credit available to a consumer takes into account their income, age, and location. Also, while premium tax credits are calculated based on the premium of a silver tier plan, consumers do not need to be enrolled in a silver tier plan to use these tax credits. See figure 1 for an illustration of how the premium tax credit for a 30-year-old individual living in Salt Lake County, Utah, would have been calculated in 2022. (We use 2022 for this example to be consistent with the year of the analyses used to inform the findings of this report.)

aPremium tax credits cannot be used to purchase a catastrophic plan available through the Marketplace. Catastrophic plans are available only to individuals under 30 and others who qualify for a hardship exemption or affordability exemption (based on Marketplace or job-based insurance being unaffordable).

bA premium tax credit cannot exceed the amount

of the premium. If an individual chooses a plan with a premium that is less

than their maximum premium tax credit, the premium tax credit is the lower of

the two amounts.

CSRs and actuarial values (AV). Marketplace consumers with household incomes from 100 to 250 percent of the federal poverty level who are eligible for premium tax credits and enroll in silver tier plans are also eligible to receive CSRs that further reduce out-of-pocket costs and increase the AVs of their plans.[26] A health plan’s AV is a measure of the relative generosity of a plan’s benefits that is expressed as a percentage of the covered medical expenses expected to be paid by the insurer on average. For example, on average, enrollees in a silver tier plan (which generally has an AV of 70 percent) would expect the plan to pay 70 percent of the costs of covered services they use, and enrollees would pay the remaining 30 percent.

For consumers who are eligible for CSRs and enroll in silver tier plans, the AVs of their plans are increased. These higher AV plans reduce enrollee costs, including by charging lower copays and coinsurance amounts, and by having lower deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums. The AVs of the three silver tier plans with CSRs are

· 73 percent for covered individuals with incomes greater than 200 percent and less than or equal to 250 percent of the federal poverty level;

· 87 percent for covered individuals with incomes greater than 150 percent and less than or equal to 200 percent of the federal poverty level; and

· 94 percent for covered individuals with incomes greater than or equal to 100 percent and less than or equal to 150 percent of the federal poverty level.

In 2022, around 53 percent of all covered individuals in Marketplace plans were in one of the three silver tiers with CSRs.[27] See table 3.

|

Plan type |

Number of covered individuals |

Percentage of all Marketplace-covered individuals |

|

Marketplace plansa |

10,187,998 |

100% |

|

Bronze tier, 60% actuarial value (AV) |

3,447,850 |

34% |

|

Silver tier with no cost-sharing reduction (CSR), 70% AV |

507,669 |

5% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 73% AV |

506,333 |

5% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 87% AV |

1,368,120 |

13% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 94% AV |

3,553,409 |

35% |

|

Gold tier, 80% AV |

804,617 |

8% |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: A health plan’s AV is a measure of the relative generosity of a plan’s benefits that is expressed as a percentage of the covered medical expenses expected to be paid by the insurer on average. Covered individuals who have household incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level who are eligible for premium tax credits and select silver tier plans are also eligible to receive CSRs that further reduce out-of-pocket costs and increase the AV of their plans.

For the purposes of this table, we use Marketplace plan selection as a proxy for enrollment.

aMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver,

and gold tier Marketplace plans combined. Our analysis did not include

catastrophic or platinum tier Marketplace plans. The Marketplace data include

individual plan enrollments in the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov

platform, whether consumers enrolled directly into plans using the platform or

enrolled through a third party, such as an agent or broker.

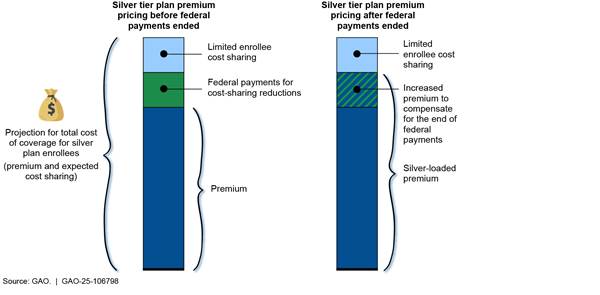

Silver loading. Originally, in 2014, HHS made payments to issuers to reimburse them for reduced cost sharing from qualified enrollees. After HHS discontinued these payments, beginning in plan year 2018, the responsibility to pay for CSRs shifted to issuers. As we reported in 2018, issuers in most states increased the premiums they charged for silver tier plans to offset the loss of federal payments. These silver plan increases were larger than increases made to plans in other metal tiers because enrollees who receive CSRs are typically enrolled in silver plans.[28] This approach, which loads the cost of silver plan CSRs onto silver plan premiums, is commonly referred to as “silver loading.”

Differences between Employer-Sponsored and Marketplace Plans

PPACA provides that grandfathered health plans, such as employer-sponsored group health plans that were offered on March 23, 2010, are not subject to a number of PPACA’s market reform provisions.[29] For example, while all Marketplace plans are required to have an out-of-pocket maximum, that requirement does not apply to grandfathered employer-sponsored plans. In addition, while all Marketplace plans are required to cover certain preventive services without cost-sharing requirements for enrollees, that requirement does not apply to grandfathered employer-sponsored plans. These differences in health plan elements like cost sharing and coverage requirements, in addition to the nuances of health plan design, make comparing Marketplace and employer-sponsored plans complex. See table 4 for a comparison of key structural differences between Marketplace and employer-sponsored plans, including grandfathered plans.

|

Health plan element |

Employer-sponsored plans |

|

Marketplace plans |

|

Federal financial support |

Payroll and income tax exemptions |

|

Premium tax credits and tax exemptionsa |

|

Non-federal financial support |

Employer premium contributions |

|

Cost-sharing reductions |

|

Annual out-of-pocket maximum limits |

Required except for grandfathered plansb |

|

Required |

|

Ten federally defined essential health benefit categories covered |

Required except for large group, self-funded and grandfathered plansb,c,d |

|

Required |

|

Certain preventive services covered without cost sharing |

Required except for grandfathered plansb |

|

Required |

|

Treatment for pre-existing conditions |

Required |

|

Required |

Source: GAO analysis of Healthcare.gov and Department of the Treasury information. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: Additionally, individual Marketplace plan premiums can vary by age and location.

aSome Marketplace enrollees with medical expenses that reach a certain threshold may deduct the amount they spent on health plan premiums from federal income taxes.

bA grandfathered health plan refers to an existing plan in which at least one individual has been enrolled since March 23, 2010. These plans are subject to fewer requirements than plans established later. To maintain grandfathered status, a plan must avoid certain changes to benefits, cost sharing and employer contributions.

See Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 1251, 124 Stat. 119, 161 (2010) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. 18011).

cIn general, large group plans are offered by an employer with 51 or more employees, but states may elect to define a large employer as one with 101 or more employees.

dIn self-funded plans, the employer pays for employee health care benefits directly, bearing the risk for covering medical benefits generated by beneficiaries.

Employer-Sponsored Plans Had Lower Average Premiums Than Marketplace Plans, but Higher Average Enrollee Contributions to Premiums

Average Premiums Were Lower for Employer-Sponsored Plans, but Differences in Covered Populations Limit Comparability between Employer-Sponsored and Marketplace Plans

Our analysis found that, per covered individual, the estimated average premiums for employer-sponsored plans were generally lower than average premiums for Marketplace plans. We found, however, that demographic and other differences in the covered populations complicate the comparability of premiums between these two types of plans.[30] Specifically, we found that, for the 33 states in our review, our estimate of the average monthly premium per covered individual in 2022 for employer-sponsored plans was $55 lower than the corresponding average for Marketplace plans.[31] Furthermore, the estimated average monthly premium per covered individual for employer-sponsored plans was $138 lower than the average monthly premium for Marketplace gold tier plans. According to some studies, Marketplace gold tier plans have an average AV similar to that of employer-sponsored plans.[32] See table 5.

|

|

Estimated average monthly premium per enrolled employee (95 percent confidence interval) |

Estimated average monthly premium per covered individual (95 percent confidence interval) |

|

|

Employer-sponsored plans |

|

||

|

Plan coverage type |

|

|

|

|

Single |

$619 ($587-$652) |

n/a |

|

|

Employee-plus-one |

$1,214 ($1,140-$1,289) |

n/a |

|

|

Family |

$1,769 ($1,659-$1,879) |

n/a |

|

|

All employer-sponsored plansa |

n/a |

$539 ($511-$567) |

|

|

|

|

Average monthly premium per covered individual |

|

|

Marketplace plans |

|

||

|

Metal tier |

|

||

|

Marketplace plansb |

n/a |

$594 |

|

|

Bronze |

n/a |

$526 |

|

|

Silver |

n/a |

$623 |

|

|

Gold |

n/a |

$677 |

|

Legend: n/a = Not applicable.

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: Our estimate for employer-sponsored plans is based on Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data and is limited to plans offered by private sector employers. The employee-plus-one and family coverage estimates are premiums for policies that cover multiple individuals. The estimates per employee are weighted by enrolled employees across the 33 states.

aWe used MEPS-IC data reported on a per employee level as the basis to estimate the average monthly premium per covered individual across the 33 states and all three coverage types. This estimate was calculated using a proxy for the average number of covered individuals for a family coverage plan of 3.83 (CI 3.70-3.96) that we derived from national level U.S. Census Bureau household survey data. Employee-plus-one plans were counted as two covered individuals and single plans as one.

bMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver,

and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or

platinum tier Marketplace plans. The Marketplace data include individual plan

enrollments in the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether

consumers enrolled directly into plans using the platform or enrolled through a

third party, such as an agent or broker.

Reporting average premiums across our 33 selected states masks variation in premiums by geographic area. Our analysis of premiums for both employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans found variation in average premiums depending on the state in which plans were sold. We also found that there was narrower state-by-state variation for employer-sponsored plan premium estimates compared to average premiums for Marketplace plans. Specifically, our per covered individual estimates of average monthly employer-sponsored plan premiums ranged from a low of $483 (CI $423-$543) in Alabama to a high of $634 (CI $569-$698) in Alaska—an estimated difference of $151. The average per covered individual monthly premiums in 2022 for Marketplace plans ranged from a low of $408 in Utah to a high of $1,144 in West Virginia—a difference of $736.

For employer-sponsored plans, the average premium also masks variation in premiums across industries. For example, MEPS-IC national data for private sector employer-sponsored plan enrollees showed variation in average total premiums across different industries. According to these data, in 2022 the estimated average total monthly premium for a retail company employee with a single coverage plan was $598 (CI $581-$616) compared to $680 (CI $662-$697) for a financial services and real estate company employee in a single coverage plan.[33]

For Marketplace plans, because their premiums can vary by the age of the covered individual, average premiums also mask variation in premiums by age.[34] For example, in 2022, the premium for the second lowest-cost Marketplace silver tier plan in Salt Lake County, Utah, was $406 per month for a 30-year-old individual and $621 per month for a 50-year-old individual.

In addition to the various factors that mask variation when comparing average premiums, stakeholders we interviewed noted other factors that limit the comparability of premiums of employer-sponsored plans (which are group plans) to Marketplace plans (which are nongroup plans). For example, stakeholders from an actuarial association and an association representing insurers told us that there are differences in the risk pools for these two types of plans. Specifically, they noted that nongroup plan enrollees are generally sicker than large group plan enrollees. One stakeholder also described Marketplace enrollees as generally older than employer-sponsored plan enrollees, while another stakeholder noted that more of the enrollees in Marketplace plans are early retirees. These demographic factors, along with other considerations like provider networks, benefits offered, cost sharing and average plan AV, as well as regulatory requirements and other factors insurers take into consideration in setting premiums, may affect average premiums and complicate the comparability of premiums for Marketplace and employer-sponsored plans.

Estimated Average Enrollee Contributions to Premiums for Employer-Sponsored Plans Were Higher Than Enrollee Contributions to Premiums for Marketplace Plans

|

Taxes and Enrollee Health Plan Premiums Employee and employer premium contributions to employer-sponsored health plans are made with pre-tax dollars. This lowers the amount of income on which the employee must pay taxes and is a tax savings for the employee. Enrollee premium contributions to Marketplace plans are generally made with after-tax dollars. However, some Marketplace enrollees with medical expenses that reach a certain threshold may deduct the amount they spent on health plan premiums from federal income taxes. For employer-sponsored plans, the tax benefit for an enrollee’s health plan contributions excluded or deducted from taxable income depends on the income and tax rate of the enrollee. For example, as illustrated in table 1, in 2022, an individual with employer-sponsored health coverage with taxable earnings of $75,000 per year with an annual health plan premium of $6,000, would have saved $1,320 in federal income taxes that year as well as $918 in forgone Social Security and Medicare taxes. Source: GAO analysis based on Internal Revenue Service information. | GAO‑25‑106798 |

Our analysis of per covered individual enrollee contributions to premiums found that in 2022, the estimated average monthly enrollee contribution for employer-sponsored plans was higher than the average enrollee contribution for Marketplace plans. After employers’ contributions, the estimated average monthly contribution to premiums per covered individual for employer-sponsored plans was $150 (CI $142-$158). After premium tax credits, the average monthly per covered individual contribution to premiums for Marketplace plans was $109.[35] See table 6. Taxes complicate comparability, however, because enrollee contributions to employer-sponsored plans are paid with pre-tax dollars, which results in a tax savings for enrollees, while enrollee contributions to Marketplace plans are generally paid with after-tax dollars. See sidebar.

|

|

Estimated average monthly enrollee contributions to premiums per enrolled employee (95 percent confidence interval) |

Estimated average monthly enrollee contributions to premiums per covered individual (95 percent confidence interval) |

|

|

Employer-sponsored plans |

|

||

|

Plan coverage type |

|

|

|

|

Single |

$138 ($129-$147)a |

n/a |

|

|

Employee-plus-one |

$370 ($345-$396)a |

n/a |

|

|

Family |

$549 ($511-$587)a |

n/a |

|

|

All employer-sponsored plansb |

n/a |

$150 ($142-$158) |

|

|

|

|

Average monthly enrollee contributions to premiums per covered individual |

|

|

Marketplace plans |

|

||

|

Metal tier |

|

||

|

Marketplace plansc |

n/a |

$109d |

|

|

Bronze |

n/a |

$125d |

|

|

Silver |

n/a |

$77d,e |

|

|

Gold |

n/a |

$276d |

|

Legend: n/a = Not applicable.

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: Our estimate for employer-sponsored plans was based on Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data and was limited to plans offered by private sector employers. The employee-plus-one and family coverage estimates are premiums for policies that cover multiple individuals. The estimates per employee are weighted by enrolled employees across the 33 states.

Average contributions to premiums for employer-sponsored plans and for Marketplace plans include enrollees with zero-dollar premium contributions.

aEnrollee contributions to premiums for employer-sponsored plans reflect the balance after employer contributions and are paid with pre-tax dollars, which results in a tax savings to enrollees.

bWe used MEPS-IC data reported on a per employee level as the basis to estimate the average monthly contributions to premiums per covered individual across the 33 states and all three coverage types. This estimate was calculated using a proxy for average number of covered individuals for a family coverage plan of 3.83 (CI 3.70-3.96) that we derived from national level U.S. Census Bureau household survey data. Employee-plus-one plans were counted as two covered individuals and single plans as one.

cMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver, and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or platinum tier Marketplace plans. The Marketplace data include individual plan enrollments in the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether consumers enrolled directly into plans using the platform or enrolled through a third party, such as an agent or broker.

dEnrollee contributions to premiums for Marketplace plans are the amount after premium tax credits and are paid, generally, with after-tax dollars. Average enrollee contributions to premiums per covered individual for Marketplace plans take into account premium tax credits. When calculating enrollee contributions to premiums for Marketplace plans, we use advance premium tax credits as a proxy for premium tax credits.

eThe majority of covered individuals in silver

tier plans were from households with incomes under 200 percent of the federal

poverty level. As a result, silver tier plan enrollees received among the

highest premium tax credits, resulting in lower average contributions to

premiums per covered individual when compared with those in bronze tier plans.

Enrollee contributions to premiums for employer-sponsored plans varied across employers.[36] For example, national MEPS-IC survey data on private sector employer-sponsored plans showed variation in the average share of employee contributions across industry type. Specifically, in 2022 an employee in single coverage employed by a retail company was, on average, responsible for an estimated 25 percent (or $150) (CI 23 percent-27 percent and $136-$163) of the average monthly premium for such a plan. Comparatively, an employee in single coverage employed by a financial services and real estate company was, on average, responsible for contributing an estimated 19 percent (or $128) (CI 18 percent-20 percent and $122-$135) of the average monthly premium.

Additionally, 2022 premiums for silver tier plans were, on average, higher than that of bronze tier Marketplace plans. However, the average enrollee contribution to premiums per covered individual in silver tier plans was lower as a result of premium tax credits, which are income based. In 2022, the majority (83 percent) of covered individuals in silver tier plans were from households with incomes from 100 up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level—levels that would make them eligible to receive among the highest premium tax credits. By contrast, most covered individuals in bronze and gold tier plans (68 and 85 percent, respectively) were from households with incomes above 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

|

Coverage Gap Premium tax credits are generally only available for households with incomes at or above 100 percent of the federal poverty level—$12,880 for a single person in the 48 contiguous states in 2022. In states that have expanded Medicaid to cover certain adults up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, individuals with incomes below the 100 percent of federal poverty level premium tax credit threshold are generally eligible for Medicaid coverage. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, however, individuals whose incomes are below 100 percent of the federal poverty level may not be eligible for either premium tax credits or Medicaid coverage, depending on their states’ Medicaid eligibility criteria. For example, in some states, adults without a disability or a dependent are not eligible for Medicaid, regardless of their income. According to research released in 2024 from KFF using data from 2022, nearly 1.5 million people living in the ten states that have not opted to expand Medicaid as of the publication of their research fell into this coverage gap. Source: Department of Health and Human Services and GAO analysis of KFF research. | GAO‑25‑106798 |

Access to both premium tax credits and CSRs are factors that may have driven high enrollment in silver tier plans among covered individuals in households with lower incomes. For example, in 2022, about 83 percent of covered individuals in silver tier plans were from households with incomes from 100 to 200 percent of the federal poverty level, compared with 31 percent of covered individuals in bronze plans in households with incomes in that range. At this income level, individuals would have been eligible to receive among the highest premium tax credits amounts that year (regardless of the metal tier plan selected) and they would have also been eligible for CSRs if they chose coverage in a silver tier plan.

The contributions to premiums for Marketplace plans by enrollees eligible for premium tax credits varied less by geographic location than total premiums varied. For example, in 2022, the premium for the lowest-cost bronze plan for a 30-year-old individual was $254.10 per month in Salt Lake County, Utah (the state with the lowest average Marketplace premiums) and $596.48 per month in Kanawha County, West Virginia (the state with the highest average Marketplace premiums)—a difference of $342.38. However, after the premium tax credit, a single 30-year-old enrollee with a household income at 150 or 250 percent of the federal poverty level in either county would pay no premium for the lowest-cost bronze plan. Similarly, a single 30-year-old enrollee with a household income at 400 percent of the federal poverty level would contribute $212.96 towards the monthly premium in Salt Lake County and $243.46 in Kanawha County—a difference of $30.50 per month. See table 7.

|

|

Salt Lake County, Utah |

Kanawha County, West Virginia |

|

Premium for lowest-cost bronze plan |

$254.10 |

$596.48 |

|

Enrollee contribution to premium after premium tax credit |

|

|

|

Household income 150% of the federal poverty level ($19,320) |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

|

Household income 250% of the federal poverty level ($32,200) |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

|

Household income 400% of the federal poverty level ($51,520) |

$212.96 |

$243.46 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Marketplace plan enrollees eligible for premium tax credits experienced less geographic variation in the amounts they contributed to premiums than those in Marketplace plans who did not receive premium tax credits. Because premium tax credits limit enrollee contributions to premiums based on household income—regardless of location or age—premium tax credits for enrollees in states that have higher premiums will be larger than that of enrollees in states with lower premiums. Similarly, because premiums are higher for older enrollees, the premium tax credits for older enrollees will be larger than the premium tax credits for younger enrollees. See figure 2 for an illustration of the calculation of premium tax credits in 2022 for 30-year-old and 50-year-old individuals with the same income in Salt Lake County, Utah, and Kanawha County, West Virginia.

In addition, because the premium tax credit is calculated, in part, based on

the premium of the second lowest-cost silver plan (also referred to as the

benchmark plan), the contribution to premiums for an older enrollee who

receives a premium tax credit could be less than that for a younger enrollee

who receives a premium tax credit for the same plan. For example, in 2022 the

premiums for a 50-year-old were $388.83 for the lowest-cost bronze plan in Salt

Lake County, Utah, and $938.60 for the lowest-cost bronze plan in Kanawha

County, West Virginia, which are notably higher than the premiums for a

30-year-old ($254.10 and $596.48, respectively). However, because the benchmark

plan for a 50-year-old was also more expensive than the benchmark plan for a

30-year-old, a 50-year-old with the same income would have had a higher premium

tax credit. When that higher tax credit is applied to the lowest-cost bronze

plan, the result could be a lower contribution to premiums for a 50-year-old

enrollee compared to that of a 30-year-old enrollee with the same income

selecting the same plan. See table 8 for examples of premiums and contributions

to premiums in 2022 for different aged enrollees in Salt Lake County, Utah, and

Kanawha County, West Virginia.

|

|

Salt Lake County, Utah |

Kanawha County, West Virginia |

||

|

|

30-year-old |

50-year-old |

30-year-old |

50-year-old |

|

Premium for lowest-cost bronze plan |

$254.10 |

$388.83 |

$596.48 |

$938.60 |

|

Enrollee contribution to premiums after premium tax credit |

|

|

|

|

|

Household income 150% of the federal poverty level ($19,320) |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

|

Household income 250% of the federal poverty level ($32,200) |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

|

Household income 400% of the federal poverty level ($51,520) |

$212.96 |

$132.39 |

$243.46 |

$173.78 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Average Cost-Sharing Amounts and Selected Covered Benefits Varied across Marketplace and Employer-Sponsored Plans

Estimated Average Cost-Sharing Amounts for Employer-Sponsored Plans Varied; Some Were Higher, Others Were Lower Than the Average for Marketplace Plans

In 2022, for the 33 states in our review, estimated average cost-sharing amounts for employer-sponsored plans were sometimes higher and sometimes lower when compared to Marketplace plan averages. However, the complexity of plan design complicates comparisons across Marketplace and employer-sponsored plans. For example, data we reviewed for employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans (MEPS-IC and CMS data, respectively) did not necessarily reflect the nuances of plan design or how those nuances may have affected who enrolled in each plan, which could affect how much enrollees paid for the health care services they received.

Our review focused on four cost-sharing features that applied to in-network services for employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans—deductibles, out-of-pocket maximums, and copays and coinsurance.[37]

Deductibles. We found that, for the 33 states in our review, compared to employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans, a greater share of individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans in 2022 were in plans with no deductibles—meaning they did not have to meet a deductible before their plan started paying for covered services. Specifically, 37 percent of individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans were in plans with no deductible compared to an estimated 8 percent (CI 7 percent-9 percent) of employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans with no deductible. This high percentage of Marketplace enrollees in plans with no deductibles was driven by the number of individuals enrolled in two of the silver tier plan variants with CSRs (the CSR plan variants with 87 and 94 percent AV), many of which had no deductible. See table 9.

|

Plan type |

Percentage of total Marketplace enrollees |

Percentage of enrollees in a plan with no deductible (95 percent confidence interval) |

|

Employer-sponsored plans (estimate)a |

n/a |

8% (7%-9%) |

|

Marketplace plansb |

100% |

37% |

|

Bronze tier, 60% actuarial value (AV) |

34% |

1% |

|

Silver tier with no cost-sharing reduction (CSR), 70% AV |

4% |

5% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 73% AV |

5% |

5% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 87% AV |

13% |

39% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 94% AV |

36% |

83% |

|

Gold tier, 80% AV |

8% |

10% |

Legend: n/a = Not applicable.

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) reports the percent of employees in plans with a deductible. For Marketplace plans, when determining which plans had a deductible, we included any non-zero deductible. This includes any non-zero value for plans with a combined medical and drug deductible or any non-zero value for either medical or drug deductibles.

A health plan’s AV is a measure of the relative generosity of a plan’s benefits that is expressed as a percentage of the covered medical expenses expected to be paid by the insurer on average. Covered individuals who have household incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level who are eligible for premium tax credits and select silver tier plans are also eligible to receive CSRs that further reduce out-of-pocket costs and increase the AV of their plans.

aOur estimates for employer-sponsored plans were based on MEPS-IC data and were limited to plans offered by private sector employers. The percentage of employees in a plan with a deductible includes those employees in single, employee-plus-one, and family coverage. MEPS-IC survey data is reported at a per enrolled employee level.

bMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver, and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or platinum tier Marketplace plans. Marketplace data are reported at a per covered individual level. Marketplace data in this table are based on effectuated enrollment, which is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enroll in a Marketplace plan, have selected a plan, and have submitted the first premium payment for a Marketplace plan. Because this data includes some plan variants where the number of enrollees is suppressed due to privacy concerns, it may not represent 100 percent of effectuated enrollment. The Marketplace data include individual plan enrollments in the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether consumers enrolled directly into plans using the platform or enrolled through a third party, such as an agent or broker.

|

Drug Deductible According to national Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data for private sector employers, in 2022, 9.9 percent (confidence interval [CI] 9-11 percent) of employees enrolled in employer-sponsored health plans had a separate drug deductible. The average drug deductible for those enrollees was $357 (CI $317-$397). Among the individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans in 2022, we found that 13 percent had a separate drug deductible. The average drug deductible for those individuals was $3,360, driven primarily by bronze tier enrollees who had an average $4,374 drug deductible. Additionally, when there are separate medical and drug deductibles, some plans may have no deductible for one service type and a deductible for the other service type. For example, we found that 76 percent of Marketplace enrollees with a separate drug deductible had no medical deductible. This means they only needed to meet a deductible for drugs. Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798 |

There are different ways deductibles can be structured that complicate comparisons of deductible amounts across plans. Notably, some plans have a single total deductible that applies to both medical services and drugs, while others have separate deductibles for medical services and drugs. For example, employer-sponsored plans and Marketplace plans differ in their use of separate drug deductibles. See sidebar.

Because of these and other complexities of plan design for deductibles, as well as limitations in the detail available in the MEPS-IC data, we focused our comparison of deductible amounts on individual medical deductibles for in-network services. This included plans that had a total deductible that pertained to both medical services and drugs or a separate deductible for medical services—which we refer to throughout this section collectively as medical deductibles.[38]

We found that across the 33 states in our review, among plans that had a medical deductible, our estimates of average individual medical deductibles for employer-sponsored plans were lower than that of Marketplace plans. But a much higher percentage of Marketplace enrollees were in plans with no medical deductible.[39] Among plans that had a medical deductible, the estimated average individual annual medical deductible in 2022 for employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans was $2,063 (CI $1,943-$2,182), compared to an average of $4,285 for individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans. However, the average individual medical deductibles in plans with a medical deductible for three Marketplace tiers—silver tier plan variants with 87 and 94 percent AV CSR and gold tier plans—were lower than the estimate of that for employer-sponsored plans. Additionally, the majority of Marketplace plan enrollees in that same year (57 percent) were enrolled in plans in one of these three tiers. See table 10.

|

Plan type |

Percentage of total Marketplace enrollees |

Average individual medical deductible (for plans that have a deductible) (95 percent confidence interval) |

Average individual medical deductible (including plans with no deductible) (95 percent confidence interval) |

|

Employer-sponsored plans (estimate)a |

n/a |

$2,063 ($1,943-$2,182) |

$1,902 ($1,794-$2,011) |

|

Marketplace plansb |

100% |

$4,285 |

$2,536 |

|

Bronze tier, 60% actuarial value (AV) |

34% |

$7,067 |

$6,968 |

|

Silver tier with no cost-sharing reduction (CSR), 70% AV |

4% |

$4,715 |

$4,439 |

|

Silver CSR tier with 73% AV |

5% |

$3,312 |

$3,114 |

|

Silver CSR tier with 87% AV |

13% |

$765 |

$449 |

|

Silver CSR tier with 94% AV |

36% |

$366 |

$60 |

|

Gold tier, 80% AV |

8% |

$1,568 |

$1,411 |

Legend: n/a = Not applicable.

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: The calculations for average medical deductibles included separate medical deductibles and total deductibles that pertained to both medical services and drugs. Separate drug deductibles were not included in these calculations. Averages in the table are enrollment-weighted.

A health plan’s AV is a measure of the relative generosity of a plan’s benefits that is expressed as a percentage of the covered medical expenses expected to be paid by the insurer on average. Covered individuals who have household incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level who are eligible for premium tax credits and select silver tier plans are also eligible to receive CSRs that further reduce out-of-pocket costs and increase the AV of their plans.

aOur estimates for employer-sponsored plans were based on Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data and were limited to plans offered by private sector employers. The percentage of employees in a plan with a deductible includes those employees in single, employee-plus-one, and family coverage. MEPS-IC data reports average individual deductibles for employees enrolled with single coverage. When estimating the individual medical deductible for employer-sponsored plans including those plans with no deductible, we assumed that the rate for those single plan enrollees with no deductible was the same as the rate of employees across all coverage types with no deductible. The average individual medical deductible was then weighted based off the number of enrolled employees in single plans across the 33 states.

bMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver,

and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or

platinum tier Marketplace plans. Marketplace data in this table are based on

effectuated enrollment, which is the number of unique individuals who have been

determined eligible to enroll in a Marketplace plan, have selected a plan, and

have submitted the first premium payment for a Marketplace plan. Because this

data includes some plan variants where the number of enrollees is suppressed due

to privacy concerns, it may not represent 100 percent of effectuated

enrollment. The Marketplace data include individual plan enrollments in the 33

states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether consumers enrolled

directly into plans using the platform or enrolled through a third party, such

as an agent or broker.

In addition, national level survey data for employer-sponsored plans also showed variation in average individual medical deductibles across industries. For example, according to these data, in 2022, the estimated average individual medical deductible for an employee of a retail company in a single coverage plan with a deductible was $2,079 (CI $1,929-$2,229). In comparison, the estimated average individual medical deductible for an employee of a financial services and real estate company in a single coverage plan with a deductible was $1,707 (CI $1,609-$1,805).

Beyond the variation in the use of deductibles and their amounts, there are other complexities that make it challenging to compare deductibles across employer-sponsored plans and Marketplace plans. For example, all Marketplace plans are required to provide coverage for recommended preventive care like mammograms and behavioral health screenings at no cost to patients. These services are not subject to the deductible. These requirements apply to most, but not all, employer-sponsored plans depending on whether they have been granted a grandfathered status.[40] Similarly, it is difficult to know the full costs that covered individuals in these plans pay for the health care services they use before meeting their deductible. For example, two plans may have identical deductibles, but one plan may have more expensive copays for specialist visits prior to reaching the deductible. Another plan may have lower specialist visit copays but require the enrollee to pay the full negotiated amount of that specialist visit up until the deductible is reached.

Out-of-pocket maximums. For the 33 states in our review, the average individual out-of-pocket maximum—generally a cap on the maximum amount a covered individual will pay each year for covered expenses—was similar for employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans. However, while some employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans were in plans that did not have an out-of-pocket maximum, all individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans were in plans with out-of-pocket maximums.

Our estimate of the average individual out-of-pocket maximum for employer-sponsored plans, among plans that had an out-of-pocket maximum, was $4,715 (CI $4,454-$4,975) compared to an average of $4,986 for Marketplace plans. However, an estimated 8 percent (CI 7-9 percent) of employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans were in plans that did not have an individual out-of-pocket maximum, and no individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans were in plans without an individual out-of-pocket maximum. See table 11.

|

Plan type |

Percentage of total Marketplace enrollees |

Average individual out-of-pocket maximum (for plans that have an out-of-pocket maximum) (95 percent confidence interval |

Percentage of covered individuals in a plan with no out-of-pocket maximum (95 percent confidence interval |

|

Employer-sponsored plans (estimate)a |

n/a |

$4,715 ($4,454-$4,975) |

8% (7%-9%) |

|

Marketplace plansb |

100% |

$4,986 |

0% |

|

Bronze tier, 60% actuarial value (AV) |

34% |

$8,435 |

0% |

|

Silver tier with no cost-sharing reduction (CSR), 70% AV |

4% |

$8,369 |

0% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 73% AV |

5% |

$6,603 |

0% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 87% AV |

13% |

$2,724 |

0% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 94% AV |

36% |

$1,411 |

0% |

|

Gold tier, 80% AV |

8% |

$7,505 |

0% |

Legend: n/a = Not applicable.

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: A health plan’s AV is a measure of the relative generosity of a plan’s benefits that is expressed as a percentage of the covered medical expenses expected to be paid by the insurer on average. Covered individuals who have household incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level who are eligible for premium tax credits and select silver tier plans are also eligible to receive CSRs that further reduce out-of-pocket costs and increase the AV of their plans. Averages in the table are enrollment-weighted.

aOur estimates for employer-sponsored plans were based on Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data and were limited to plans offered by private sector employers. The individual out-of-pocket maximum data in MEPS-IC is reported only for those employees enrolled in single coverage plans, so the average individual out-of-pocket maximum and the percentage of covered individuals in a plan with no out-of-pocket maximum are for employees enrolled in a single plan.

bMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver,

and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or

platinum tier Marketplace plans. Marketplace data is reported at a per covered

individual level. Marketplace data in this table are based on effectuated

enrollment, which is the number of unique individuals who have been determined

eligible to enroll in a Marketplace plan, have selected a plan, and have

submitted the first premium payment for a Marketplace plan. Because this data

includes some plan variants where the number of enrollees is suppressed due to

privacy concerns, it may not represent 100 percent of effectuated enrollment.

The Marketplace data include individual plan enrollments in the 33 states that

used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether consumers enrolled directly into

plans using the platform or enrolled through a third party, such as an agent or

broker.

National level survey data for employer-sponsored plans also showed variation in average out-of-pocket maximums across industries. For example, in 2022, among employees enrolled in single coverage plans that had an out-of-pocket maximum, the estimated average individual out-of-pocket maximum for an employee of a retail company was $4,807 (CI $4,559-$5,055). This is in comparison to an out-of-pocket maximum of $4,399 (CI $4,255-$4,573) for an employee of a financial services and real estate company.

Although the overall average out-of-pocket maximums in employer-sponsored and Marketplace plans were similar, comparing averages miss an important element. As noted above, we estimated that 8 percent (CI 7-9 percent) of covered individuals in employer-sponsored plans did not have an out-of-pocket maximum in 2022. For that estimated 8 percent, the potential annual out-of-pocket costs—such as costs for undergoing expensive treatment for certain cancers—could far exceed both Marketplace and other employer-sponsored plan limits. This difference limits the comparability of estimated average individual out-of-pocket maximums in employer-sponsored plans to Marketplace plan out-of-pocket maximums. Comparing the averages does not account for the fact that an estimated 8 percent of employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans are potentially at risk for incurring catastrophic medical expenses.

Copays and coinsurance. Our review of 2022 data in the 33 selected states found that average enrollment-weighted copays and coinsurance among plans with such features were generally either similar or lower for employer-sponsored plans compared to Marketplace plans. For example, our estimate for the average copay for general physician services for employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans ($28; CI $26-$30) was the same as the average copay for individuals enrolled in Marketplace plans ($28). But we estimated that employer-sponsored plan enrollees had a lower average coinsurance for general physician services (20 percent; CI 19-22 percent) compared to covered individuals in Marketplace plans (31 percent). Additionally, the average enrollment-weighted copays and coinsurance among plans with such features for the different Marketplace tiers varied—some were higher, while others were lower, than estimated averages of employer-sponsored plans. See table 12 for general physician and specialist physician copay and coinsurance data, and appendix II for additional copay and coinsurance data, including for prescription drugs.

|

|

General physician visit |

Specialist physician visit |

||

|

Plan type |

Average copay (95 percent confidence interval) |

Average coinsurance (95 percent confidence interval) |

Average copay (95 percent confidence interval) |

Average coinsurance (95 percent confidence interval) |

|

Employer-sponsored plans (estimate)a |

$28 ($26-$30) |

20% (19%-22%) |

$48 ($45-$52) |

22% (20%-23%) |

|

Marketplace plansb |

$28 |

31% |

$41 |

34% |

|

Bronze tier, 60% actuarial value (AV) |

$47 |

40% |

$85 |

44% |

|

Silver tier with no cost-sharing reduction (CSR), 70% AV |

$33 |

25% |

$69 |

36% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 73% AV |

$26 |

25% |

$59 |

36% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 87% AV |

$13 |

20% |

$28 |

30% |

|

Silver CSR tier with 94% AV |

$7 |

13% |

$10 |

22% |

|

Gold tier, 80% AV |

$23 |

21% |

$46 |

29% |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

Notes: While this table describes average cost sharing for certain types of covered benefits, preventive care services like mammograms and behavioral health screenings are provided at no cost to enrollees for all Marketplace plans and for most employer-sponsored plans.

Average copays reflect plans that have a non-zero value for copays. Average coinsurance reflect plans that have a non-zero percentage of coinsurance. Averages in the table are enrollment weighted.

A health plan’s AV is a measure of the relative generosity of a plan’s benefits that is expressed as a percentage of the covered medical expenses expected to be paid by the insurer on average. Covered individuals who have household incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level who are eligible for premium tax credits and select silver tier plans are also eligible to receive CSRs that further reduce out-of-pocket costs and increase the AV of their plans.

aOur estimates for employer-sponsored plans were based on Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data and were limited to plans offered by private sector employers. We used MEPS-IC data that were reported at the per employee level to weight average copays and coinsurance across the 33 selected states.

bMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver,

and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or

platinum tier Marketplace plans. Marketplace data are reported at a per covered

individual level. The Marketplace data include individual plan enrollments in

the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether consumers enrolled

directly into plans using the platform or enrolled through a third party, such

as an agent or broker.

Like the other cost-sharing features we analyzed, complexity in plan design makes comparing average copays and coinsurance across plans challenging. For example, different plans may apply different rules for when and how cost sharing is applied to the deductible. Some plans may require enrollees to pay the full cost of certain services until the deductible is met, while others may limit enrollee costs for these services to the copay or coinsurance amounts before the deductible is met. Additionally, for some plans, certain services, such as preventive services, may be available at no cost, while for other plans they are not. These are just a few examples of many ways that plan designs can differ.

Most, but Not All, Employees Enrolled in Employer-Sponsored Plans Had Coverage for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Benefits, Which Marketplace Plans Are Required to Cover

As previously noted, our comparison of benefits focused on mental health care and substance abuse treatment because of challenges in measuring other types of care. Our review found that most, but not all, employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans were in plans that had coverage for mental health and substance abuse care. All Marketplace plans are required to cover these as essential health benefits. Specifically, according to our estimates using MEPS-IC survey data across the 33 states, 6 percent (CI 1-10 percent) of employees enrolled in employer-sponsored plans may lack mental health coverage and 7 percent (CI 3-12 percent) may lack substance abuse treatment coverage.[41] See table 13.

|

Plan type |

Percentage of enrollees with mental health benefits (95 percent confidence interval) |

Percentage of enrollees with substance abuse treatment benefits (95 percent confidence interval) |

|

Employer-sponsored plans (estimate)a |

94% (90%-99%) |

93% (88%-97%) |

|

Marketplace plansb |

100% |

100% |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality MEPS-IC data. | GAO‑25‑106798

aOur estimates for employer-sponsored plans were based on Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data and were limited to plans offered by private sector employers. We used MEPS-IC survey data that were reported at the per employee level to estimate average benefit coverage across the 33 selected states.

bMarketplace plans refers to bronze, silver, and gold tier plans combined. Our analysis did not include catastrophic or platinum tier Marketplace plans. Marketplace data are reported at a per covered individual level. The Marketplace data include individual plan enrollments in the 33 states that used the Healthcare.gov platform, whether consumers enrolled directly into plans using the platform or enrolled through a third party, such as an agent or broker.

The Loss of Federal Payments for CSRs Resulted in Increased Premium Tax Credits for Certain Marketplace Enrollees