SMALL BUSINESS CONTRACTING

National Nuclear Security Administration Needs Increased Contractor Oversight to Reduce Reporting Errors

Committee on

Armed Services,

United States Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106820. For more information, contact Allison Bawden at (202) 512-3841 or BawdenA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106820, a report to

Committee on Armed Services,

United States Senate

National Nuclear Security Administration Needs Increased Contractor Oversight to Reduce Reporting Errors

Why GAO Did This Study

Since 1988, the federal government has aimed to award at least 20 percent of contract dollars to small businesses. NNSA’s small business contracts typically account for more than half of DOE’s small business achievement.

Since 1990, GAO has designated aspects of NNSA’s acquisition management as a high-risk area because of its record of inadequate management of contractors. The DOE Inspector General has identified contract management as a fraud risk.

Senate Report 117-130 includes a provision for GAO to review NNSA’s approach to contracting with small businesses and achieving its small business contracting goals. This report examines the extent to which (1) NNSA and its M&O contractors accurately reported fiscal years 2018–2022 small businesses contracts; and (2) NNSA has conducted oversight of its M&O contractors’ small business contract reporting, including assessing fraud risks.

GAO reviewed small business contract data from NNSA and six M&O contractors for fiscal years 2018–2022, analyzed a sample of the data to identify errors, and spoke with knowledgeable contracting officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations, including that NNSA and its M&O contractors identify the root causes of reporting errors and establish an approach to address them, that NNSA improve oversight of reported data, and that NNSA develop mitigations for fraud risk in its small business program. NNSA agreed with all five recommendations.

What GAO Found

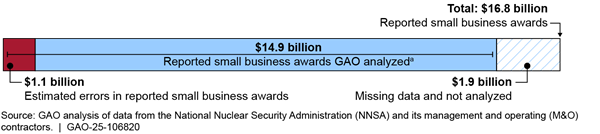

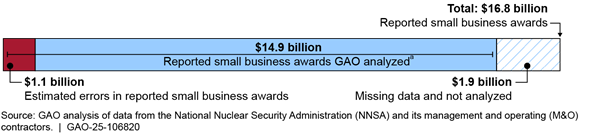

GAO estimates that the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and six of its management and operating (M&O) contractors incorrectly reported $1.1 billion of their $16.8 billion in small business contracts awarded in fiscal years 2018–2022. That is, they incorrectly reported awarding small business contracts to businesses that did not meet size standards established by the Small Business Administration. Further, for an additional $1.9 billion of the $16.8 billion, NNSA and the six M&O contractors could not provide the information needed for GAO to determine whether the small business contracts had been awarded to businesses that were actually small. Based on NNSA and M&O contractor responses about these errors, GAO identified three main reasons errors might be occurring in small business reporting: (1) not having a requirement to verify a business’s status as small; (2) mistakes using contractor-specific procurement systems; and (3) businesses misrepresenting themselves as small—intentionally or unintentionally. By identifying and addressing the root causes of errors in reported data, NNSA can ensure the quality of the data it reports and ensure that small businesses do not lose out on opportunities for work.

Estimated Errors in NNSA and M&O Contractors’ Reported Small Business Awards, Fiscal Years 2018–2022

aEstimated errors are based on analysis of the subset of businesses that had a higher likelihood of not being small at the time of the contract award.

NNSA’s oversight has not ensured accurate reporting of small business achievements primarily because NNSA has not dedicated Small Business Program resources to oversight. First, NNSA does not use the available data systems to assure the quality of small business contract data. Second, NNSA has not developed lessons learned to document findings from past reviews, conducted by both NNSA and the Small Business Administration, that identified problems in certain contractors’ data and processes. These problems were still present for contractors during GAO’s review. The Department of Energy (DOE) has a lessons learned program that is generally required to be used by NNSA and its M&O contractors. By taking steps to ensure the quality of small business contract data and share lessons learned, NNSA can improve the accuracy of its small business reporting. Finally, NNSA has not identified fraud risks—for example, that businesses may represent themselves as small when they are not—or developed responses to mitigate those risks. Without identifying and developing responses to potential fraud risks, NNSA cannot ensure that small businesses receive all intended contracting opportunities.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

DUNS |

Data Universal Numbering System |

|

eSRS |

Electronic Subcontracting Reporting System |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

M&O |

management and operating |

|

MOSRC |

Management and Operating Subcontract Reporting Capability |

|

NAICS |

North American Industry Classification System |

|

NNSA |

National Nuclear Security Administration |

|

OSDBU |

Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization |

|

SAM.gov |

System for Award Management |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

UEI |

Unique Entity Identifier |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 13, 2025

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

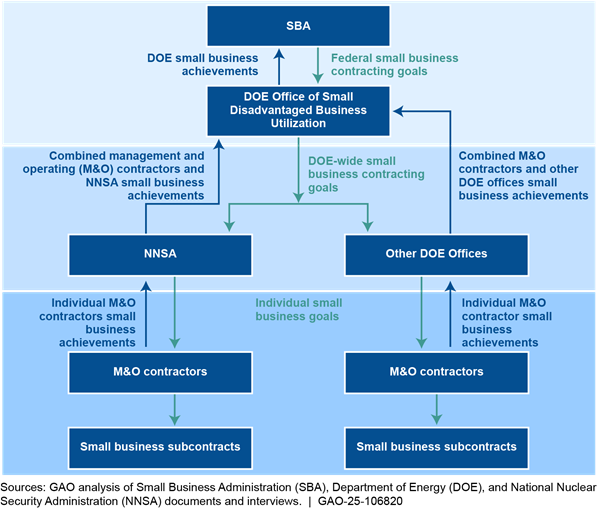

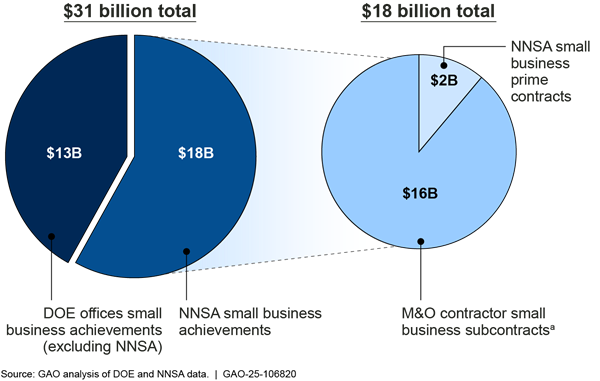

Since 1988, the federal government has aimed to award at least 20 percent of contract dollars to small businesses.[1] Small businesses are important drivers of the nation’s overall economic growth, and small business goals help maximize small businesses’ opportunity to provide goods and services to the federal government. The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a separately organized agency within the Department of Energy (DOE), reported awarding contracts to small businesses that accounted for approximately $18 billion of DOE’s $31 billion in small business achievements, or 58 percent, from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022.

Federal agencies, such as DOE, negotiate their respective annual small business goals with the Small Business Administration (SBA). Since 2014, DOE has been allowed, in addition to considering prime contracts in meeting small business goals, to count subcontracts with small businesses to help achieve its small business prime contracting goal.[2] For example, NNSA enters into prime contracts with small businesses to carry out some work and also with large businesses, such as management and operating (M&O) contractors.[3] These small businesses and M&O contractors in turn subcontract to small businesses to perform some work.

Because typically 80 to 90 percent of DOE’s, and NNSA’s, budgets are obligated for M&O contracts, including subcontracts issued by M&O contractors, DOE’s small business achievement provides a more holistic view of the effect DOE funds have on small businesses. NNSA and its M&O contractors have contracted with small businesses for goods and services such as semiconductor manufacturing, audio and video equipment manufacturing, legal and accounting services, and scientific and technical consulting. For more information on the goods and services purchased from small businesses by NNSA and its M&O contractors, see appendix I.

Since 1990, we have designated aspects of DOE’s (including NNSA’s) acquisition management as a high-risk area for the government because of DOE’s record of inadequate management and oversight of contractors.[4] Further, the DOE Inspector General has identified contract management as a significant challenge for DOE and has identified fraud risk as a concern.[5] Ensuring that fraud risks are identified and mitigated is important to the integrity of any federal program and enables federal agencies to be strategically positioned to address the most significant fraud risks to federal programs.

Senate Report 117-130, accompanying the fiscal year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, includes a provision for us to review NNSA’s approach to contracting with small businesses and achieving its small business contracting goals.[6] In our report, we examine the extent to which (1) NNSA and its M&O contractors accurately reported fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022 small business contracts; and (2) NNSA has conducted oversight of its M&O contractors’ small business contract reporting, including assessing fraud risks.

To determine the extent to which NNSA’s Small Business Program and NNSA’s M&O contractors accurately reported on small business contracts, we reviewed fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022 data reported for small business contracts awarded by NNSA and six NNSA M&O contractors.[7] We chose these fiscal years because fiscal year 2022 was the most recent year for which there was complete data at the time of our review, and the 5-year period covers fiscal years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we reviewed data from each M&O contractor’s procurement systems and the Federal Procurement Data System, the system of record for federal procurement data.

To analyze NNSA and M&O contractor data, we grouped them into what we refer to as “instances,” that is, contract or purchase order groupings with the same (1) unique business identifiers assigned by the System for Award Management (SAM.gov) and Dun & Bradstreet; (2) North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code assigned to the contract or purchase order; and (3) the date of the first and last contract or purchase order award by each M&O contractor, if multiple contracts or purchase orders were awarded.

For example, if ABC Corp (identification number 123456789) was awarded 15 contracts by M&O Contractor Number 1 from October 2018 through September 2022 that were all performed under NAICS code 236000 (construction of buildings), these would be rolled up into a single instance in our data.[8]

Some businesses were in our dataset multiple times, for example, because they were awarded multiple contracts under the same NAICS code by different M&O contractors, or because they performed work under contracts with different NAICS codes. We then compared these instances with the small business size determinations generated by SAM.gov, where businesses enter their annual revenue and employee number data.[9] We used SAM.gov datasets from 2017, 2022, and 2024 to compare the instances at three points in time.[10] When business data were not available in SAM.gov, they were excluded from use in creating estimates.

We created two subsets of instances for awards to small businesses: (1) instances for businesses categorized as small, according to SBA’s NAICS code-based size standards, for all points in time for which they had data in the three SAM.gov datasets we used for our analysis; and (2) instances for businesses not categorized as small, according to those size standards, in one or more of those years.

We concluded that businesses in the first subset of data were highly likely to have been small for the purposes of the award and as reported by NNSA and its M&O contractors.

We performed additional analysis on the second subset of businesses because they had a higher likelihood of not being small at the time of the contract award. Using this second subset of data, which comprised 3,339 instances and was worth $4.1 billion in contract awards, we drew a generalizable stratified sample to ascertain the amount of contract dollars awarded to businesses that were not small under the size standard on a contract at the time of award. Additionally, we used this sample to estimate the number of contracts associated with businesses that were not small under the size standard on a contract at the time of award. We interviewed NNSA officials and M&O contractor representatives about potential reasons for errors in the data. We base our discussions about NNSA and M&O contractor data errors and the numbers we report on this generalizable sample. Margins of error for any sample-derived estimates in this report were calculated at the 95 percent confidence level.

To examine the extent to which NNSA’s Small Business Program has conducted oversight of its M&O contractors’ small business contract reporting, we reviewed SBA regulations, the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), the Department of Energy Acquisition Regulation, agency-specific guidance on contractor oversight, and relevant GAO reports.[11] We also reviewed information from the Electronic Subcontracting Reporting System (eSRS), a government-wide tool for monitoring subcontracting performance; the Federal Procurement Data System; and DOE’s Management and Operating Subcontract Reporting Capability (MOSRC) data.

We reviewed federal requirements for reports M&O contractors submit on their subcontracting activities, and corresponding DOE guidance.[12] We reviewed documentation from SBA compliance reviews to identify any known deficiencies among contractors and identify potential lessons learned. Additionally, we compared NNSA’s and its M&O contractors’ processes and data reporting with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government for managing reliable data and evaluating deficiencies. We interviewed SBA and NNSA officials regarding steps taken to oversee subcontract reporting. We also randomly selected a non-generalizable sample of 18 businesses from M&O contractor data and interviewed representatives about their experiences subcontracting with M&O contractors.

To understand the potential for increased fraud risk in NNSA’s reporting of its small business contract awards, we reviewed GAO’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework. The Office of Management and Budget’s Circular A-123 directs federal agencies, including DOE, to implement the Framework.[13] Fraud and fraud risk are distinct concepts. “Fraud” is the act of obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation and is a determination to be made through the judicial or other adjudicative system. “Fraud risk” exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity, have an incentive or are under pressure to commit fraud, or are able to rationalize committing fraud. Although the occurrence of fraud indicates there is a fraud risk, a fraud risk can exist even if actual fraud has not yet been identified or occurred. While our report did not assess fraud, we did examine the risk of fraud in the context of NNSA’s oversight of NNSA’s M&O contractors’ small business reporting. In appendix II, we describe our methodology in more detail.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2023 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Size Standards for Small Businesses

The U.S. Census Bureau assigns a six-digit code—called a NAICS code—to each industry based on its primary activity,[14] and SBA uses NAICS codes as the basis for establishing size standards for small businesses. Size standards vary by industry and are generally expressed either as the average number of employees or the average annual revenue.[15]

For certain codes, there is more than one size standard. SBA refers to these additional size standards as exceptions. For example, NAICS code 541715 (research and development in the physical, engineering, and life sciences, except nanotechnology and biotechnology) has a general size standard of 1,000 employees—meaning that a business with 1,000 employees or fewer that is contracted under this NAICS code would be considered small. This code also has three exceptions related to aircraft and aircraft engines (1,500 employees); other aircraft parts and auxiliary equipment (1,250 employees); and guided missiles and space vehicles, their propulsion units and propulsion parts (1,300 employees)—each of which creates a different threshold for determining whether a business is small.[16]

According to the FAR, when drawing up a contract or subcontract solicitation, contracting officers at NNSA or an M&O contractor must assign a NAICS code to the contract based on the principal purpose of the contract that will be issued. However, the choice of NAICS code is ultimately at the contracting officer’s discretion.[17] If a business’s revenue or employee count at the time it makes an offer are below the SBA size standard for the NAICS code assigned to that contract, it is considered a small business. If the revenue or employee count is above the threshold, the business is considered “other than small” (not small). Because the size standard for every NAICS code differs, a business can be small under some NAICS codes and not small under others at the same time.

SAM.gov is a government database in which businesses must register to compete for prime contracts with the federal government. Businesses must renew their registration annually, though they can also update their registration at any time to reflect changes to revenue, employee numbers, or NAICS codes they work under, for example. SAM.gov automatically populates a table of size standards—categorizing a business as small or not small for each NAICS code—according to a business’s revenue and employee information the business enters when registering or updating its profile. For businesses that are competing only for subcontracts and choose not to register in SAM.gov, the business representative would need to look up the size standard associated with the NAICS code on the solicitation for which the business is competing and ensure that the business is representing itself correctly—as small or not small.

Process for Setting DOE’s Small Business Goal and NNSA’s Process for Reporting Contracts

Each autumn, DOE’s Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization (OSDBU) negotiates the agency’s annual small business goal with SBA. DOE and SBA set the goal based on DOE’s past, current, and projected performance toward meeting its small business goals. For example, from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022, DOE’s small business goal was 10 to 14 percent of procurements, or between $3 billion and about $5.6 billion. Prior to DOE and SBA agreeing on the DOE-wide goal, OSDBU negotiates goals with each DOE program office based on that office’s previous achievement and projected procurements for the upcoming fiscal year.[18]

NNSA’s Small Business Program, which is separate from OSDBU, submits its own goal to OSDBU for inclusion in DOE’s overall goal. NNSA’s Small Business Program determines NNSA’s goal by negotiating site-specific goals with each of its M&O contractors for their small business subcontracts.[19] At the end of each fiscal year, NNSA’s Small Business Program reports NNSA’s and its M&O contractors’ small business achievements to OSDBU, so that OSDBU can include them in agencywide performance reporting against the department’s small business goals (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Process for Setting DOE’s Small Business Contracting Goal, and NNSA and DOE Offices’ Process for Reporting Contracts

NNSA documents its small business prime contracts in DOE’s Strategic Integrated Procurement Enterprise System. This system feeds contract information into the government-wide Federal Procurement Data System. OSDBU uses that system to generate reports on NNSA’s contributions toward meeting small business goals.

Each of NNSA’s M&O contractors documents its small business subcontracts in its respective procurement system. M&O contractors then upload portions of this contracting information into two different databases: DOE’s MOSRC and in eSRS, the web-based, government-wide system accessible to contractors and agency contracting officers. M&O contractors upload contract-level data to MOSRC on a monthly basis but cannot include any sensitive or classified contract information, so MOSRC only represents about 50 percent of small business contracts issued by NNSA’s M&O contractors. They upload summary-level data—the total amount of all small business contracts issued—twice per year into eSRS. NNSA can use these two systems during a fiscal year to track M&O contractor performance in meeting small business goals.[20]

NNSA and Its M&O Contractors Incorrectly Reported an Estimated $1.1 Billion in Small Business Contracts

From fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022, NNSA and six of its M&O contractors reported awarding contracts worth approximately $16.8 billion to small businesses. However, in our sample, we identified an estimated $1.1 billion of contracts that were reported in error because the contracts were awarded to businesses that were not small at the time the contract was awarded under the NAICS code on the contract. We identified three potential reasons for these errors in reported data: contracting officers not being required to verify a business’s representation of itself as small; mistakes made in entering or using information in M&O contractor procurement systems; and businesses misrepresenting themselves as small––intentionally or unintentionally.

An Estimated $1.1 Billion of Reported Awards to Small Businesses Went to Businesses That Did Not Meet Revenue or Employee Size Standards

From fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022, NNSA and six of its M&O contractors reported awarding $16.8 billion in contracts to small businesses. While some of these contracts were worth millions of dollars, the average contract amount across all six M&O contractors was approximately $32,000.[21]

Reviewing the subset of data likely to contain errors, we estimate that $1.1 billion of the contracts awarded by NNSA and the six M&O contractors from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022 that were reported as awarded to small businesses were actually awarded to businesses that were not small according to the NAICS code on the contract. We believe this $1.1 billion amount to be a conservative estimate of the total amount of errors in awards to small businesses that were reported for two reasons. First, this sample was taken from a subset of data that was more likely to have errors, and there may be additional errors in the other subset of data. Second, while we were able to analyze $14.9 billion of reported small business contracts, approximately $1.9 billion in reported contracts did not have the data we needed (identifying information for the business or the NAICS code on the contract) to carry out our analyses.[22] Thus, it is unclear to what extent this $1.9 billion in small business contracts was awarded to businesses that were small (see fig. 2).

aIncludes NNSA prime contracts with small businesses and subcontracts awarded by the six NNSA M&O contractors for whom NNSA negotiates small business goals. Estimated errors are based on analysis on the subset of businesses that had a higher likelihood of not being small at the time of the contract award.

Further, we estimate that the $1.1 billion incorrectly reported as being awarded to small businesses was awarded through at least 7,100 contracts. While these contracts were only about 4 percent of the total number of contracts we analyzed, we found that five of six M&O contractors had numerous––sometimes hundreds––of these errors in their reported data.[23]

We also found that many of the 7,100 contracts in the reported data that we estimate were awarded to businesses that were not small were in many cases not the only contract awarded to that business by a specific M&O contractor. Rather, they were often one of multiple contracts issued to individual businesses that were not small under the NAICS code at the time of the award. This, and the fact that we found errors in the data of NNSA and all six M&O contractors, indicates a systemic issue. NNSA and the M&O contractors issued contracts repeatedly to businesses that were not small under the NAICS code on the contract at the time of award. We are not referring simply to isolated instances of contracts being issued in error.

Three Reasons Contributed to NNSA and M&O Contractors Incorrectly Reporting Contracts Issued to Small Businesses

Analyzing interview responses from NNSA’s Small Business Program manager and representatives from the six M&O contractors, we identified three main reasons contributing to the incorrect reporting of awards to small businesses.

First, M&O contractors are not required to verify businesses’ representations. M&O contractors can accept businesses’ representations of themselves as small without further verification.[24] We found that some M&O contractors do not check a database, such as SAM.gov, to verify a business’s representation of itself as small under the NAICS code on the contract. According to the Small Business Act and the FAR, M&O contractors are not required to verify a business’s status as small under the NAICS code on the contract via a source such as SAM.gov or SBA’s Dynamic Small Business Search.[25] Rather, they are allowed to accept a business’s representation of itself as small without further verification.

To ascertain a business’s size, representatives from four of the six M&O contractors told us that they rely on paper or electronic representations and certifications forms. Specifically, each offer, proposal, bid, or application for a federal subcontract must contain a certification concerning the small business size and status of the business seeking the subcontract. The business responding must certify its status on the form.[26]

As noted, businesses are not required to register in SAM.gov to compete for subcontracts from M&O contractors, but we found that approximately 95 percent of businesses we searched for in SAM.gov in our sample analysis were registered.[27] Representatives from some M&O contractors said that they encourage businesses to register in SAM.gov, and representatives from two M&O contractors and officials from NNSA said that they do verify a business’s representations and certifications information in SAM.gov.

Additionally, representatives from two M&O contractors told us that for contracts under $10,000, the contracting officer does not need to obtain a representations and certifications form.[28] Representatives from one M&O contractor said their contracting officers may ascertain the business’s size through a verbal self-certification––the contracting officer simply asks the business representative if it is small––and no other checks of the business’s size need to be made. The representatives from this M&O contractor did not indicate whether the verbal check of a business’s size is supposed to include a mention of the specific NAICS code on the contract and the associated size standard for the NAICS code to ensure the appropriate thresholds are being considered.

Second, NNSA and M&O contracting officers may be entering information incorrectly into their respective procurement systems. Representatives from two of the six M&O contractors and officials from NNSA mentioned potential issues with their procurement systems that might lead to businesses being misreported as small. In four instances, officials from the businesses we interviewed told us that they had never represented themselves as a small business at all, or as small under the NAICS code on a particular contract. Representatives from one business said that they had checked the box as a large business on the representations and certifications form for a contract, and they were not sure how they had been classified as a small business in that M&O contractor’s data.

NNSA officials said that their procurement system has buttons that allow the contracting officer to select business size; if the contracting officer forgets to select a business size, the system may default to small, but officials were unsure if this was the main reason for errors.

In another case, representatives from an M&O contractor said that their procurement system only allows one NAICS code to be entered on a business’s profile, so they use the business’s primary NAICS code and note whether the business is small on that profile. If the business is awarded a contract under another NAICS code, the contracting officer must create another profile for the business in the procurement system, including whether the business is small under that NAICS code. As a result, businesses can have multiple profiles––each with a different NAICS code and potentially a different size designation––in this M&O contractor’s procurement system, and the contracting officer must select the correct profile to record the contract award.

Representatives from this M&O contractor said it was possible that contracting officers may not always select the correct profile with the correct NAICS code and size designation, thus potentially identifying a business as small in the data they report to NNSA when it is not small under the NAICS code on the contract. Additionally, this M&O contractor’s procurement system only allows for six digits of a NAICS code to be input, so the seventh digit that signifies an exception to a size standard is not captured in this procurement system. This means that some data may be reported incorrectly as a result of not being able to note the NAICS exceptions.

Representatives from the same M&O contractor noted that they made significant changes to their procurement system in 2017, so that when a new business profile is created it defaults to being listed as a small business unless the contracting officer or person creating the profile manually changes the profile to not small. As a result, errors may have been introduced into this contractor’s data when business profiles were not correctly updated or created, listing businesses as small when they were not.

Third, businesses may misrepresent themselves as small, intentionally or unintentionally. A business misrepresenting itself as small intentionally could be fraudulent activity; we did not look specifically for fraud during our audit, nor did we detect any fraudulent activity. But a representative from one M&O contractor noted that fraud––a business intentionally misrepresenting itself as small when it is not a small business to gain something of value––would be possible. An official from NNSA also said that his team is aware of the risk of businesses misrepresenting themselves as small when they are not.

Several factors might contribute to a business unintentionally representing itself as small. For example, some contractors did not specify the NAICS code or the relevant size standard for that NAICS code, as required by federal regulations.[29] As a result, businesses might have been unaware of the NAICS code the contracting officer assigned to the contract and the size standard associated with that NAICS code, making the potential for unintentional misrepresentation as a small business higher. Representatives of multiple small businesses we interviewed said that they typically work under a single NAICS code. As a result, they might not be familiar with the size standards associated with other NAICS codes and might assume they are small under every NAICS code if they are small under one NAICS code—when in reality, their status depends on the size standard assigned to the specific code.

Additionally, if a business changes from small to large because of an increase in revenue or number of employees that surpass the size standard for a particular NAICS code, the business should notify the M&O contractor to update information in the contractor’s procurement system when it makes an offer on a new contract.[30] It should also note the change on any subsequent representations and certifications forms. However, if businesses are not closely monitoring their status as small or associated size standards, it is possible for businesses who no longer qualify for awards to small businesses to receive them, again, through unintentional misrepresentation as small. For example, a representative from one small business we interviewed knew its business’s revenues had gone up from 2020 through 2022 but was unsure if its status as small had changed as a result of the increased revenue.

We were able to identify a few common reasons that officials from NNSA and representatives from M&O contractors gave for errors occurring in their data, but we did not identify the root causes for errors in NNSA’s and each M&O contractor’s data because their data collection processes and systems all differ. However, it is important for NNSA’s Small Business Program and M&O contractors to ensure errors are reduced so that small businesses have the maximum opportunity to participate in contracts.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Reliable sources provide data that are reasonably free from error and bias and faithfully represent what they purport to represent. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should evaluate issues and remediate deficiencies. Managers may do so by evaluating and documenting issues and determining and completing appropriate corrective actions for deficiencies on a timely basis.

Identifying the root causes of errors in small business contracting data and eliminating or mitigating those root causes from contracting and reporting processes would help ensure that NNSA and M&O contractors award contracts to businesses that are small under the NAICS code on the contract, potentially increasing opportunities for small businesses to be awarded contracts. NNSA’s Small Business Program and its M&O contractors each have a role to play in identifying the root causes of errors and developing approaches to address them to increase the quality of the small business contracting data reported to NNSA.

NNSA Has Not Ensured Accurate Small Business Contract Reporting or Mitigated Fraud Risk

NNSA has conducted limited oversight of small business award data that M&O contractors submit and that NNSA uses for small business reporting, primarily because of limitations in the data NNSA has available to it and because NNSA has not dedicated resources for this type of oversight. In particular, even though NNSA officials were aware of past problems with data and processes, they have not taken steps to address data limitations. Additionally, NNSA has not regularly shared lessons learned with M&O contractors from NNSA’s and SBA’s relevant reviews, thus limiting contractors’ ability to learn from each other and implement practices that could be effective for improving small business data and reporting. Finally, NNSA has not identified fraud risks to the Small Business Program—for example, that businesses can represent themselves as small when they are not—and has not developed responses to mitigate those risks.

NNSA’s Oversight Has Not Ensured Accurate Reporting of Small Business Achievements

NNSA’s oversight of M&O contractors is primarily subject to the FAR, as well as to the Department of Energy Acquisition Regulation and internal DOE and NNSA guidance.[31] NNSA officials told us that for tracking and reporting small business achievements, they rely on the summary reports submitted by M&O contractors in eSRS, which contain summary-level data on the total amounts awarded to small businesses during specific periods of time.

M&O contractors are to submit mid-year summary reports in April and October, and an end-of-year summary report is to be submitted annually in October on contract award data through eSRS.[32] For example, in an eSRS summary report, NNSA officials may see that an M&O contractor reported awarding $2 billion in total subcontracts to small businesses in a given fiscal year, but they cannot see any other details about individual subcontracts that were awarded. NNSA officials also provide periodic feedback reports to M&O contractors during the contract evaluation period that highlight small business contracting accomplishments, issues, and areas where the contractor’s performance met, or did not meet, expectations.

NNSA officials are responsible for reviewing and accepting or rejecting these summary reports. They said their review typically consists of looking for any data that appear to be outliers, such as a dollar amount that is extremely high or low compared to prior reports. If NNSA officials reject a summary report, it is returned to the M&O contractor for correction and resubmission. However, NNSA officials said they do not conduct any additional verification of eSRS data before using it to report small business achievements to DOE. NNSA officials also told us they use mid-year summary reports from eSRS to ensure M&O contractors are on track to meet their small business goals.

eSRS provides limited opportunity for NNSA to validate the quality of the data used to create the summary reports, which is partly why, NNSA officials told us, they do not use it for this purpose. For example, during our audit, we identified variances between the data that one M&O contractor submitted to us from its procurement system and data it reported in eSRS. After we notified the contractor of the discrepancy, the contractor conducted an internal investigation of its procurement system and discovered anomalies in the reports of small business achievements for multiple years we reviewed. The anomalies resulted in the contractor incorrectly reporting its small business goals in several years and reporting that it exceeded the goal for at least one socioeconomic category when it did not actually meet the goal.[33] While the contractor implemented an interim corrective action that will allow it to identify this error in future reports, the error has not been fully resolved.

According to the FAR, the reviewing agency must reject a contractor’s subcontracting report submission if it is not properly completed, for example, if it has errors, omissions, or incomplete data.[34] However, for the summary report pertaining to the data anomaly we identified, NNSA officials only rejected the report after we identified the error in the data. Because NNSA only sees summary-level data from eSRS, it has no way of knowing based on that data alone whether the amounts contractors report are correct or whether the contracts comprising that total amount were awarded to small businesses and reported properly.

M&O contractors also submit data to DOE’s MOSRC system monthly, but an NNSA official said they do not use MOSRC data for oversight—they primarily look at MOSRC data to understand trends in small business involvement across all M&O contractors but do not use them for any other data verification or analyses.[35] This is because NNSA officials estimate that MOSRC contains about 50 percent of subcontracts issued by M&O contractors, as it excludes classified or sensitive subcontracts. Unlike eSRS, MOSRC contains contract-level data, which means agency officials have access to additional information on individual contracts such as the date of award, the business the contract was awarded to, the amount of the award, and the NAICS code on the contract, among other information.

While MOSRC data provide more detailed information, NNSA officials told us the summary-level eSRS data are more representative of each M&O contractor’s total annual contribution to NNSA’s small business goals, given that the data include contract amounts from classified and sensitive contracts, which is why they use eSRS data to report their total small business accomplishments. But NNSA is responsible for overseeing its M&O contractors and is ultimately responsible for the quality of the data they report, and that DOE includes in its reports to SBA.

NNSA could take additional steps to oversee the quality of data submitted by its M&O contractors when approving mid-year or end-of-year summary reports in eSRS and better utilize contract data provided in MOSRC to ensure that small business reporting is accurate. For example, NNSA officials could periodically select a sample of contracts from the MOSRC data for each M&O contractor and check it against another database, such as SAM.gov, to ensure contracts captured in MOSRC were issued to businesses that are small according to the NAICS code assigned to the contract.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Reliable sources provide data that are reasonably free from error and bias and faithfully represent what they purport to represent. Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should evaluate issues and remediate deficiencies. Managers may do so by evaluating and documenting issues and determining and completing appropriate corrective actions for deficiencies on a timely basis.

While the sources of data that NNSA has to assess data quality have limitations—either missing some contracts or only at the summary level—using the data that are available to monitor submissions by M&O contractors and ensure the quality of their small business contracting data and processes is important. Doing so would help ensure NNSA’s reported achievements to OSDBU are accurate and annual goals are based on accurate data.

NNSA Could Improve Oversight of Small Business Data by Documenting and Sharing M&O Contractors’ Lessons Learned

From 2017 through 2020, NNSA officials said that the Small Business Program conducted compliance audits of its M&O contractors to evaluate their compliance with subcontracting procedures and goals outlined in M&O contractors’ small business subcontracting plans. However, NNSA officials told us they discontinued their audits in January 2020 due to resource limitations and because they believed SBA had increased its resources for auditing contractors.

During one NNSA compliance review that was carried out prior to 2020, NNSA officials learned that one M&O contractor’s procurement system only stored the primary NAICS code in a business’s profile. As a result, this led the M&O contractor to classify businesses as small under all NAICS codes when they might have only been small under some NAICS codes and large under others.[36] NNSA officials told us they directed the contractor to correct the issue following its audit. However, during our review, officials from same M&O contractor identified this as one of the primary reasons for the large number of errors in its data, and this issue had not been corrected at the time of our review.

In 2022, SBA conducted compliance reviews for two of the six NNSA M&O contractors whose data we analyzed for this review.[37] During the reviews, SBA identified several issues with both contractors’ management of data and processes for issuing small business subcontracts that resulted in a marginal rating for both contractors. A marginal rating indicates that the contractor is deficient in meeting one or more subcontracting plan elements or is deficient in complying with contract terms regarding the use of small businesses, and the contractor is required to develop a corrective action plan to address issues identified in the review. SBA conducted follow-up reviews of these two contractors and updated their ratings to satisfactory in 2023 after determining that the contractors had developed and implemented corrective action plans.[38]

In table 1, we characterize examples of the findings from the initial SBA compliance reviews of these two contractors. This includes findings that both contractors used representations and certifications forms that did not require businesses to sign on the same page as their claimed size status, and that both contractors failed to include the size standard (in annual revenue or number of employees) or NAICS code on appropriate forms. Both issues put the contractors out of compliance with federal regulations. As we noted above, both issues potentially contributed to the errors we found in data reported by M&O contractors.

Table 1: Examples of Findings from Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Compliance Reviews of Two NNSA M&O Contractors, Fiscal Year 2022

|

SBA finding |

Description |

|

Size-certification non-compliance |

One contractor did not collect the size certifications for the subcontracting amounts reported on summary reports submitted in the Electronic Subcontracting Reporting System. |

|

North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code and corresponding size standard non-compliance |

Both contractors failed to include the applicable NAICS codes or the size standards on subcontracts or solicitations. |

|

Representation and certification forms non-compliance |

Both contractors’ representations and certifications forms did not include a signature block on the same page that contains the size status reported by the small business. |

|

Improper classification of small business and other categories |

One contractor’s procurement system did not properly capture size status of vendors who were awarded contracts, leading to incorrect classification of some large businesses being counted toward small business achievements. |

Source: GAO analysis of 2022 SBA Subcontracting Program Compliance Reviews for two selected National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) management and operating (M&O) contractors. | GAO‑25‑106820

SBA notified NNSA officials of findings from the compliance reviews, and NNSA officials were invited to attend the entrance and exit briefings. NNSA officials told us they found the corrective actions taken by the M&O contractors were sufficient on the basis of SBA’s follow-up reviews. Although SBA found both data and process issues in their audits, NNSA did not take additional steps to further review the two M&O contractors’ data or processes or adjust its oversight of any of its M&O contractors for awarding contracts to small businesses following the compliance reviews, primarily because they chose not to allocate resources to do so, citing limited capacity in NNSA’s Small Business Program.

SBA’s 2022 compliance reviews of two M&O contractors found that both contractors used representations and certifications forms to verify small business status from subcontractors. Those forms were not in compliance with federal regulations because they did not require a signature where the size standard associated with the contract was stated, though both M&O contractors changed their forms to bring them into compliance as part of their corrective actions.[39] Having business representatives sign on the same page as the contract NAICS code can help ensure that the business is aware of the applicable size standard and knows whether it is small under the standard. NNSA officials were alerted to the two M&O contractors using representations and certifications forms that were not in compliance in 2022 through SBA compliance reviews but did not share this information with other M&O contractors. As a result, this issue was not elevated to other M&O contractors for correction, if necessary.

During our review, we found that three of the four M&O contractors not audited by SBA also had representations and certifications forms that were not in compliance with federal regulations. Two of these M&O contractors identified the issue on their own and corrected it. But we found that one M&O contractor’s form was still not in compliance with federal regulations at the time of our review in 2024.

In some of our previous work, NNSA officials raised concerns that they do not have enough staff with the right skills in their acquisition workforce to effectively oversee contracts.[40] NNSA officials we interviewed for this review cited these same reasons as to why they rely on SBA compliance reviews to identify issues with M&O contractor processes and data and that fixes in response to those compliance reviews are effective. However, SBA only conducted compliance reviews for two of the six M&O contractors included in our review from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022.

DOE’s Corporate Operating Experience Program is intended to prevent adverse operating incidents and facilitate the sharing of good work practices among DOE sites.[41] DOE departments, including NNSA and most of its M&O contractors,[42] must submit lessons learned in DOE’s Corporate Lessons Learned Database when both (1) the operating experience has relevance to other DOE facilities, sites, or programs; and (2) the information has the potential to help avoid adverse operating incidents or contribute to performance improvements or cost savings. This helps to facilitate the sharing of good work practices among DOE sites and ensures significant issues and lessons learned can be centrally collected, stored, and retrieved to allow readily access to information on a timely basis.

NNSA officials told us that they could benefit from sharing lessons learned to allow contractors to learn from each other and to prevent recurring issues within and among M&O contractors. For example, representatives from the M&O contractor with the lowest error rate in its data told us about two practices it has implemented to help ensure data accuracy. First, representatives told us that to help the M&O contractors’ contracting officers determine the correct business size for each contract, they use a computer program to automatically gather business size data from SAM.gov at the time a contract is awarded and input that information into their own procurement system. When contracting officers are preparing to award a contract, they have current information on the business’s size according to SAM.gov already in the procurement system. While M&O contractors cannot require businesses to register in SAM.gov to bid on contracts, officials from this M&O contractor said they encourage businesses to do so, which would reduce potential for the contractor to miscategorize businesses size.

Further, representatives from this M&O contractor said that for any contracts that are awarded to businesses that are not registered in SAM.gov, instead of relying solely on a representations and certifications form, these contracts are flagged to be checked by other contracting officers to ensure that contracts are awarded to small businesses and are recorded properly. Sharing these practices with other M&O contractors could help those who use a similar procurement system and help improve M&O contractors’ processes for verifying business size before making an award.

We previously reported on DOE’s and NNSA’s use of lessons learned, which is a principal component of an organizational culture committed to continuous improvement.[43] Lessons learned aim to communicate knowledge more effectively and to ensure that beneficial information is factored into planning, work processes, and activities. Key practices of a lessons learned process include (1) collecting, analyzing, saving, or archiving; and (2) sharing and disseminating information and knowledge gained from positive and negative experiences. Given that NNSA officials have attributed a lack of resources as a reason for limited contractor oversight, documenting and sharing lessons learned about the processes used to identify and verify small business status and management of small business award data could be a cost-effective way to help M&O contractors improve their reported small business data. It could also help NNSA better determine how to allocate resources to focus efforts on the most important issues.

NNSA Could Improve Oversight of Small Business Reporting by Identifying and Mitigating Fraud Risks

Because NNSA and its M&O contractors erroneously reported an estimated $1.1 billion in small business achievements from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022, and because NNSA officials and M&O contractor representatives told us they do not fully know the root causes of these errors, NNSA’s Small Business Program faces increased fraud risk. NNSA officials told us that they are aware of the potential risk of businesses misrepresenting themselves as small, and that fraud is a risk to any federal program, including the Small Business Program. Due to the amount of money involved in small business contracting—billions of dollars—ensuring that fraud risks are identified and mitigated is important to the integrity of NNSA’s Small Business Program. While we did not specifically assess fraud during our audit, the lack of verification of small business representations by M&O contractors and lack of additional NNSA oversight of the quality of contractor data create an environment of increased fraud risk.

Fraud risk exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity that poses a significant risk to the integrity of federal programs and can erode public trust. To minimize fraud risk and increase program integrity, GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs provides leading practices that serve as a guide for program managers to use when developing or enhancing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[44] The Office of Management and Budget’s Circular A-123 directs federal agencies, including DOE, to implement the Framework. Specifically, the Framework recommends that federal programs identify risks and design and implement specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud. And a December 2024 DOE Inspector General report stated that the agency’s risk management guidance had been updated to add substantial emphasis on using data analytics to mitigate and reduce potential fraud.[45]

Effective fraud risk management helps to ensure that federal programs fulfill their intended purpose, funds are spent effectively, and assets are safeguarded, such as awards to small businesses, in this case. The Framework for Managing Fraud Risks also encourages managers to effectively assess fraud risks the agency or program faces and analyze the potential likelihood and effect of fraud schemes. We have previously highlighted that reliance on self-certifications for eligibility opens agencies up to significant fraud risk as an internal control for fraud prevention.[46] Even when programs allow for the use of self-certification, agencies can do more to design and implement control activities to prevent the emergence of fraud risks.

DOE has issued multiple enterprise risk management guidance documents to its departments, including NNSA, to improve decisions by having a holistic view of risks and their interdependencies, and those guidance documents reference the leading practices in the Framework for Managing Fraud Risks.[47] Under DOE’s guidance, headquarters offices, field and site offices, and M&O contractors are to annually assess risk, including fraud. As noted in the sidebar, we have previously reported on contracting fraud schemes at DOE, where businesses have misrepresented themselves as small to win contracting opportunities.[48]

|

Misrepresentation of Eligibility We previously reported on contracting fraud schemes that occurred at DOE, some of which included misrepresentation of eligibility. In 2021, we found multiple adjudicated cases of contractors purposefully reporting incorrect information, such as small business status, in a bid proposal to falsely claim eligibility to perform the work. In one case, in 2010 and 2012, a DOE contractor claimed that it was subcontracting to small, disadvantaged businesses when these businesses were allegedly being used as a pass-through, and the work was performed by a different subcontractor that was not a small, disadvantaged business. The awards were for multimillion-dollar subcontracts, and the government recovered over $5.5 million from the defendants. As a result of this type of scheme, legitimate small, disadvantaged businesses may not have had the opportunity to fairly compete for and perform work on subcontracts. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑106820 |

Despite knowing about contracting fraud schemes within DOE and acknowledging that fraud is a risk for any federal program, including the Small Business Program, NNSA officials told us they have not taken additional steps to identify and assess fraud risks specific to the Small Business Program. Officials told us they have not taken steps because federal statute says that contractors acting in good faith do not have to verify businesses size representations, and NNSA has not committed the resources to verifying the information itself. Additionally, representatives from one M&O contractor told us it is possible that a business could have checked a box on its representations and certifications form regarding its business size that was incorrect, intentionally or unintentionally—an example of one way this fraud risk could materialize. One NNSA official told us that with written representations and certifications forms, there is potential for error and misrepresentation.

While M&O contractors are allowed to rely on businesses’ self-certifications to determine whether they are small, the frequency with which we found awards made to businesses that were not small and were claimed as small business achievements indicate that NNSA and its M&O contractors could do more to mitigate this risk. Businesses falsely claiming small business eligibility when they are not is one example of fraud risks specific to NNSA’s Small Business Program. By identifying fraud risks and developing responses to mitigate them, NNSA can ensure that it maximizes small business participation in agency contracting.

Moreover, agencies can leverage details on fraud schemes and their corresponding effects to evaluate and adapt fraud risk management activities in alignment with leading practices outlined in the Framework for Managing Fraud Risks. NNSA may also be missing out on important trends in fraud risks that are common across multiple M&O contractors by not documenting risks as they emerge and developing appropriate responses to mitigate those fraud risks. Without identifying potential fraud risks related to small business reporting and determining an appropriate risk response, NNSA’s Small Business Program may be susceptible to undetected potential fraud, which may take away opportunities from businesses that are small under the size standard assigned to a contract, and which may cause inaccurate small business reporting to continue. NNSA could benefit from a robust process in place to prevent, detect, and respond to potential fraud that may go unnoticed.

Conclusions

NNSA’s and M&O contractors’ small business goals are intended to enhance opportunities for small businesses to participate in federal contracting. However, we found that while NNSA and six of its M&O contractors reported awarding contracts worth approximately $16.8 billion to small businesses from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022, an estimated $1.1 billion of this amount was reported in error and awarded to businesses that were not small under their contracted NAICS code. Further, this number may be an underestimate because we examined a subset of the data, and because $1.9 billion in small business contracts did not contain sufficient data for our analysis. The frequency with which we found these errors suggests NNSA can do more to improve its oversight of small business contract reporting. Taking steps to identify and address root causes for errors in both NNSA’s and M&O contractors’ reported data would better ensure that quality data are reported and that contracting opportunities are maximized to include small business participation.

While the data sources that NNSA has access to are limited in different ways, NNSA could still use that data to oversee the quality of the data used for small business reporting. Additionally, some errors we identified in the data resulted from issues previously identified by NNSA and SBA during small business reporting reviews. These issues were not regularly communicated with the M&O contractor community. By developing and documenting lessons learned from M&O contractors on how to improve accuracy of processes and data, NNSA and its M&O contractors can share positive experiences to identify potential solutions to recurring issues where they exist. Moreover, strengthening oversight of M&O contractor processes and data for reporting small business achievements can decrease fraud risk and strengthen small business contracting efforts.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of five recommendations to NNSA:

The Administrator of NNSA should ensure that the Small Business Program identifies root causes of errors in NNSA’s prime small business contract data and establishes an approach to address those root causes of errors to ensure data quality. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of NNSA should ensure that the Small Business Program works with M&O contractors to identify the root causes of errors in their small business subcontract data and establishes an approach to address those root causes of errors to ensure data quality. (Recommendation 2)

The Administrator of NNSA should ensure that the Small Business Program uses available data sources, as feasible, to oversee the quality of the data used to generate reporting on NNSA’s and M&O contractors’ small business awards. (Recommendation 3)

The Administrator of NNSA should ensure that the Small Business Program collects, develops, documents, and disseminates lessons learned about small business contracting processes and data reporting from M&O contractors to allow contractors to learn from each other and to prevent issues from recurring across the enterprise. (Recommendation 4)

The Administrator of NNSA should ensure that the Small Business Program identifies fraud risks to the program and develops responses to mitigate those risks, to ensure small business awards are used to fulfill their intended purpose. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to NNSA for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix III, NNSA concurred with all five of our recommendations. NNSA estimated it will address these recommendations by October 31, 2025 or December 31, 2025, depending on the recommendation.

NNSA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Energy, the acting NNSA Administrator, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or BawdenA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Allison Bawden

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and its management and operating (M&O) contractors awarded small businesses contracts for a variety of different goods and services from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. During this time, the Department of Energy (DOE) reported awarding approximately $31 billion in small business contracts, including subcontracts from its M&O contractors; this was approximately 16 percent of its total procurements.[49] NNSA and its M&O contractors accounted for $18 billion of DOE’s total awards to small businesses from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022.[50]

Figure 3: Department of Energy (DOE) and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) Reported Small Business Achievements, Fiscal Years 2018–2022

aThis amount reflects small business achievements by the six management and operating (M&O) contracts whose data we reviewed, in addition to achievements by the two M&O contractors for whom NNSA does not set small business goals but contributed to the total M&O small business achievements from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. Additionally, achievements reflected in this figure have been rounded and may not represent the exact small business achievements reported by DOE and NNSA.

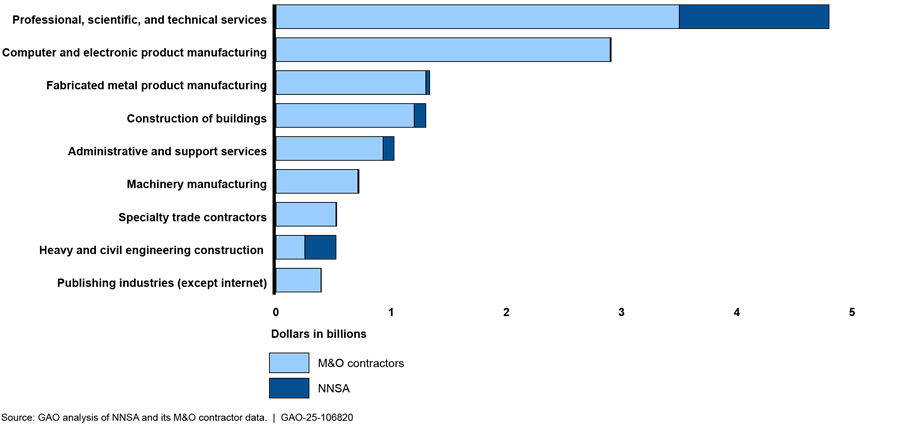

Of the $16.8 billion in small business achievements reported during 2018 through 2022 that we analyzed, almost $8 billion was awarded in two North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) categories. About $5 billion was awarded under the NAICS codes for Professional, scientific, and technical services, which includes legal services, accounting, specialized computer system design, and scientific and technical consulting services. For example, one small business owner told us that the company was contracted to carry out project management and project planning; another small business carried out safety and risk management reviews for a program. Almost $3 billion was awarded under the NAICS codes for Computer and electronic product manufacturing, which includes work like computer manufacturing, communications equipment manufacturing, audio and video equipment manufacturing, and semiconductor manufacturing.

Other areas in which NNSA and M&O contractors awarded contracts for goods and services to small businesses included Fabricated metal product manufacturing, Construction, Administrative services, and Machinery manufacturing (see fig. 4). For example, one small business was awarded a contract under a construction-related NAICS code to carry out the concrete work on a construction site in the nuclear security enterprise.

Figure 4: Top Categories of Goods and Services Purchased from Small Businesses by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and Its Management and Operating (M&O) Contractors, Fiscal Years 2018–2022

Representatives from several M&O contractors told us that they award contracts for a variety of goods and services to small businesses. Representatives from one M&O contractor said they award contracts for everything from paper to laser parts, services like high performance computing, supplemental labor, off-the-shelf commercial products, and consulting services. Representatives from another M&O contractor said that some things are easy to contract to small businesses, like custodial services or purchase of office supplies. But certain things like force protection or construction are more difficult to contract to small businesses, as there are a limited number of small businesses with capacity to do the work.

Comparison of Small Business Contracts and Associated Expenditures

The Senate report accompanying the fiscal year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act includes a provision for us to examine the differences in NNSA and its M&O contractors’ planned obligations to contracts with small businesses and the actual obligation and expenditure amounts under such contracts. We found that the majority of contracts awarded to small businesses by NNSA and its M&O contractors were largely paid out—the amounts obligated to the contract were largely expended (see table 2). We also analyzed the types of goods and services NNSA and its M&O contractors purchased from small business, according to reported small business achievements.

Table 2: Percentage of Small Business Contracts Paid Out by NNSA and M&O Contractors, Fiscal Years 2018–2022

|

NNSA or M&O contractors |

Percentage of total contracts that were more than 75% paid out to small businessesa |

|

NNSA |

54% |

|

M&O contractorsb |

93% |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and its management and operating (M&O) contractors. | GAO‑25‑106820

aOur analysis includes closed contracts that were obligated from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. When fiscal year 2023 expenditure data were available from NNSA and M&O contractors, we included that data to account for contracts that were obligated in fiscal year 2022 but were paid out in fiscal year 2023. We use “paid out” synonymously with “expended.”

bWe define M&Os as the six M&O contractors for which NNSA sets small business goals as defined by this report. This percentage includes the average amount expended across all six M&Os.

There is no requirement for M&O contractors to reconcile obligations against expenditures. Depending on the type of contract used when issuing an award, the amount obligated and expended may not always align. For example, in firm-fixed price contracts, the price is not subject to any adjustment on the basis of the contractor’s cost experience in performing the contract.[51] However, in a time-and-materials contract, the extent or duration of the work and costs cannot be accurately estimated when the contract is issued.[52] It may be beneficial for an agency to use a variety of contract types, depending on the circumstances or types of goods or services procured. Both NNSA and its M&O contractors used a variety of different contract types when awarding contracts to small businesses.

We compared the amount expended (paid out) on contracts against the amount that was obligated to the contract. We found that 54 percent of the contracts NNSA reported awarding to small businesses from 2018 through 2022 were paid out at least 75 percent or more. For example, this means that NNSA would have paid out at least $7,500 on a contract for $10,000 awarded to a small business. Additionally, we found that, on average, 93 percent of subcontracts across the six M&O contractors’ data we reviewed paid out more than 75 percent of the amounts obligated to those contracts. While some variance is expected between the amount obligated and expended, NNSA and its M&O contractors provided us with reasons for those variances. These included multiyear contracts paid out over time and use of different contract types.

To analyze obligations and expenditures on small business contracts, we requested data from NNSA and six M&O contractors on amounts obligated and expended on small business contracts from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. We also requested fiscal year 2023 expenditure data, when possible, from NNSA and M&O contractors, so that we could include it in our analysis of contracts that were obligated in fiscal year 2022 but were paid out in fiscal year 2023. In addition to our data analysis, we reviewed documents and conducted interviews with agency officials and M&O contractor representatives.

In our interviews with representatives from the same 18 businesses selected from reported data as having been awarded small business contracts noted in appendix II, we included questions about the effect of obligations that were not fully paid out on their small business operations.[53] Three small businesses mentioned that the obligated amount reflected the highest amount the M&O contractor was willing to pay for the work, and the businesses were fully paid for the actual work that was completed, which in some cases required less time to execute. While the type of contract may affect the amount obligated against the amount expended, two contractors also noted that their contracts included different methods to execute the work; however, the contracts did not require executing all options on the contract. Multiple small businesses reported positive experiences working with different M&O contractors in our scope, and they said that variances between the amounts obligated and expended did not affect business operations.

While many business representatives reported positive experiences working with M&O contractors when executing contracts, two businesses noted effects of lower-than-expected expenditures on small business operations. One business owner stated that there was a difference in opinion on how to execute the work which resulted in the contract ending early. Consequently, the owner was financially affected by not being able to complete the billable work outlined on the contract and had forgone opportunities to continue to market his business and solicit new work. Additionally, the business owner had several employees whom he hired to assist him in executing the scope of work on the contract that were also affected by the income loss from the contract ending early without being able to complete the work.

Another business representative we spoke with also noted extenuating circumstances which prevented the business from conducting work outlined on the contract. When executing the project, the project was put on hold when one of the materials needed to complete the work became unavailable in the quantities required by the M&O contractor. During the hold, the representative noted that several staff that had been background checked and cleared were unable to make progress on the work. The prolonged hold exposed the business to market concerns, as staff compensation changed from the initial amount budgeted when the contract was first awarded. However, the business representative noted positive communication by the M&O contractor despite effects on their small business operations.

Senate Report 117-130, accompanying the fiscal year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, includes a provision for us to review the National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) approach to contracting with small businesses and achieving its small business contracting goals.[54] In our report, we examine the extent to which (1) NNSA and its management and operating (M&O) contractors accurately reported fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022 small businesses contracts; and (2) NNSA has conducted oversight of its M&O contractors’ small business contract reporting, including assessing fraud risks.

We requested data on awards made to small businesses from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022 from NNSA and six of its M&O contractors for this period:

· Consolidated Nuclear Security, LLC, the M&O contractor for both the Y-12 National Security Complex and Pantex Plant;[55]

· Honeywell Federal Manufacturing and Technologies, LLC, the M&O contractor for the Kansas City National Security Campus;

· Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, the M&O contractor for Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory;

· Mission Support and Test Services, LLC, the M&O contractor for the Nevada National Security Site;

· National Technology & Engineering Solutions Of Sandia, LLC, the M&O contractor for Sandia National Laboratories; and

· Triad National Security, LLC, the M&O contractor for Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Our scope included the six M&O contractors for whom NNSA set small business goals from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. Our scope did not include M&O contractors at NNSA sites that were administered, in whole or in part, by other organizations. Specifically, our scope did not include Fluor Marine Propulsion, LLC, which managed and operated the Naval Nuclear Laboratories (jointly managed by NNSA and the U.S. Navy) from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2022, or Bechtel Marine Propulsion Corporation, which managed and operated the Naval Nuclear Laboratories in fiscal year 2018. Fluor Marine Propulsion and Bechtel Marine Propulsion did both report small business achievements to NNSA, but NNSA did not negotiate goals with those two M&O contractors. Additionally, our scope did not include Savannah River Nuclear Solutions LLC, the M&O contractor for the Savannah River Site (managed during the period of our review by the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Environmental Management).

To determine the extent to which NNSA and its M&O contractors accurately reported on small business contracts, we obtained data on all reported small business contracts awarded by NNSA and the six M&O contractors in our scope for fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2022. We carried out multiple analyses on this data. However, first, we cleaned the data to create a dataset of unique businesses found in the M&O contractors’ data and NNSA’s data.

· We used a crosswalk created with datasets from August 2021 that contained Data Universal Numbering System (DUNS) identification numbers and April 2022 that contained Unique Entity Identifier (UEI) numbers to crosswalk the list of vendors with DUNS numbers against list of vendors with UEIs to ensure as many vendors as possible had both DUNS and UEIs associated with them.

· We identified and combined any duplicate vendors in NNSA and M&O contractor data (e.g., Acme, LLC; Acme LLC; and ACME Corp.) This involved matching DUNS numbers, UEIs, or searching vendors by their System for Award Management (SAM.gov) profile. We compared business data across M&O contractors to ensure we consolidated business information correctly.

After cleaning the data, we created a consolidated dataset of business instances: each instance was one row of data per business and contained the business DUNS number, UEI, name, North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code, entity who made the award(s) (either an M&O contractor or NNSA), and total commitments. When a business received multiple contracts under a single NAICS code from an individual M&O contractor or from NNSA, these amounts were aggregated to show a total amount of contracts awarded by that M&O contractor or NNSA to the business from 2018 through 2022. Hence, an instance of a business is not a contract award but is the aggregate of all contracts awarded by a specific M&O contractor or NNSA to a business for a contract under the same NAICS code.

For some businesses, the instance may only be made up of a single contract award, if that business was only awarded a single contract. Other instances of businesses are made up of dozens or hundreds of contract awards from a single or multiple M&O contractors and NNSA. Businesses may be in our dataset multiple times if they worked under multiple NAICS codes or for multiple M&O contractors or NNSA. Our total business instance dataset contained about 34,000 instances of businesses.