INDIAN AFFAIRS

Additional Actions Needed to Address Long-standing Challenges with Workforce Capacity

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-106825

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106825. For more information, contact Anna Maria Ortiz and (202) 512-3841 or OrtizA@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106825, a report to congressional committees.

November 2024

Indian Affairs

Additional Actions Needed to Address Long-standing Challenges with Workforce Capacity

Why GAO Did This Study

Indian Affairs provides services directly to Tribes or funding for tribally administered programs, including support for tribal government operations, law enforcement, natural resource management, and climate preparedness and resilience. GAO has previously reported on lessons learned from Indian Affairs’ implementation of major legislation and long-standing challenges with the agency’s capacity to manage programs that serve Tribes.

The IRA includes a provision for GAO to oversee distribution and use of IRA funds. This report examines how IRA implementation has affected Indian Affairs’ capacity, actions the agency has taken to improve capacity that could help meet IRA workload, and opportunities to improve Indian Affairs’ capacity.

GAO reviewed relevant laws, agency documents, and agency data. GAO interviewed federal officials, federal tribal advisory groups, and tribal organizations selected based on knowledge of Indian Affairs’ work with Tribes.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress, when authorizing funds for Indian Affairs’ administrative costs, consider lessons learned from Indian Affairs’ use of IRA funds to help determine amounts for future program implementation. GAO is also making six recommendations to Indian Affairs, including that it develops the lessons learned, and a proposal for opportunities to improve capacity and the resources needed to pursue them. Indian Affairs agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

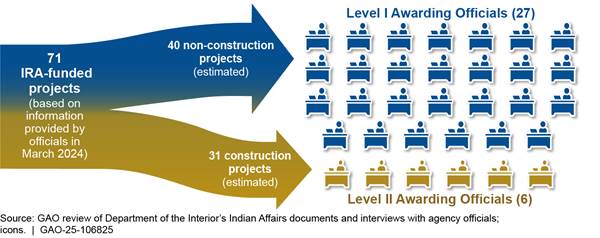

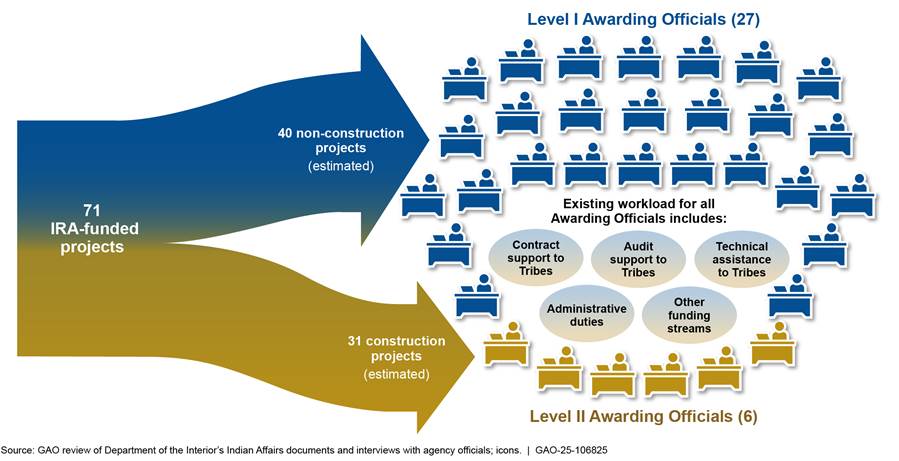

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) provided appropriations of about $385 million for new and existing programs that serve Tribes and their citizens. This additional funding has increased the workload for Indian Affairs components implementing IRA programs. Indian Affairs officials said that the workload and competing priorities strain the agency’s already-limited workforce capacity. For example, new funding streams increased the workload of Awarding Officials, particularly since only six can approve more complex construction projects.

Staff in several components implementing the IRA have regularly worked additional hours per pay period to meet workload demands, based on GAO’s analysis of workforce data, and most of the components GAO interviewed described significant vacancies.

The IRA appropriated $9.5 million for administrative costs to implement IRA programs that serve Tribes and their citizens, usable over the entire time period when these appropriations are available. Thus far, Indian Affairs has used these administrative funds—supplemented with baseline appropriations—to hire additional staff and contractors. However, Indian Affairs has not yet documented lessons learned from its use of these funds to meet the increased workload and the impact this had on other mission needs. Documenting this information could help Indian Affairs prepare for future administrative costs. In addition, Congress could use this information to help inform decisions about future appropriations.

Indian Affairs identified opportunities to improve its capacity through, for example, training and streamlining hiring. However, efficiency challenges—such as lack of written guidance for recruitment and burdensome hiring processes—limit its capacity, and officials said that budget uncertainty impedes sustained investment in capacity-building efforts. Indian Affairs has not identified the resources it needs to pursue capacity-building opportunities. Developing a proposal for Department of the Interior or Congress that identifies these needs could help Indian Affairs improve its capacity and capitalize on legislative opportunities to ensure the agency has the resources it needs to effectively provide essential services to Tribes and their citizens.

No table of contents entries found.

Abbreviations

|

AI/AN |

American Indian and Alaska Native |

|

BIA |

Bureau of Indian Affairs |

|

DRES |

Division of Real Estate Services |

|

FTE |

fulltime equivalency |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 |

|

OBPM |

Office of Budget and Performance Management |

|

OHCM |

Office of Human Capital Management |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

OSG |

Office of Self-Governance |

|

OTS |

Office of Trust Services |

|

TCR |

Branch of Tribal Climate Resilience |

|

TEP |

Tribal Electrification Program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 13, 2024

Congressional Committees

The United States has undertaken a unique trust responsibility to protect and support Tribes and their citizens through treaties, statutes, and historical relations.[1] Various laws require federal agencies to provide a range of services and benefits to Tribes and their citizens because of their unique political status. As several tribal leaders have previously noted, these trust obligations and responsibilities do not exist as a form of federal welfare but as repayment on a nation-to-nation agreement.[2]

The Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs provides a wide variety of services and funding for tribally administered programs to 574 federally recognized Tribes, serving approximately 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN).[3] Indian Affairs carries out a broad range of missions, such as supporting tribal government operations, law enforcement, natural resource management, and climate preparedness and resilience.

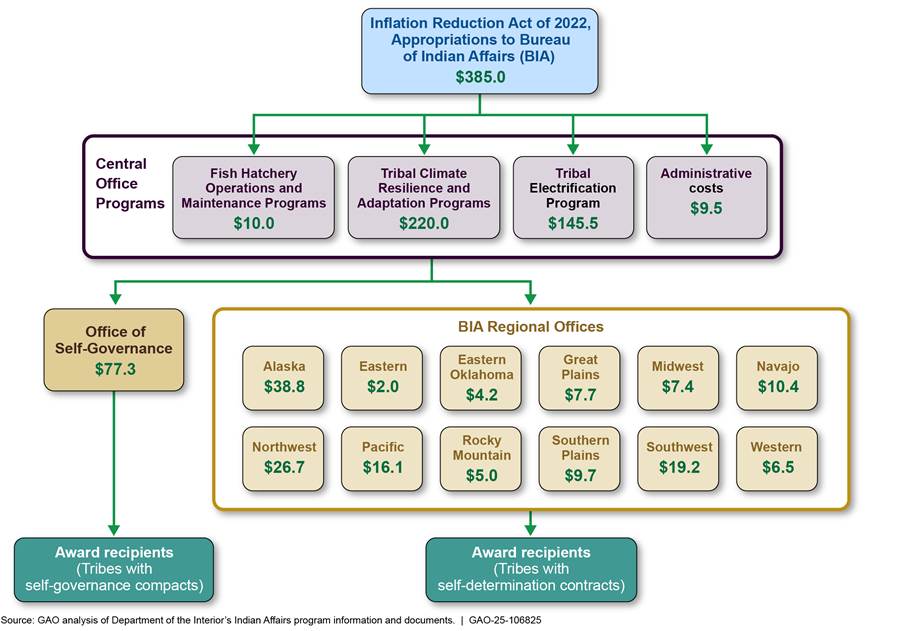

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) appropriated $385 million to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)—located under Indian Affairs—for existing and new programs that help advance climate resilience and adaptation, fish hatchery needs, and a new tribal electrification program.[4] BIA components involved with IRA implementation may use $9.5 million of this appropriation for associated administrative costs, which Interior has interpreted to include hiring additional staff and other workforce planning necessary to implement these programs.[5] Meanwhile, other Indian Affairs components support these programs with existing staff resources.

We have previously reported on lessons learned from Interior’s implementation of landmark legislation, such as COVID-19 relief, and provided information to Congress about how to streamline delivery of such funds to Tribes when the capacity of federal agencies and recipients is under strain.[6] Additionally, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has highlighted the long-standing shortfall in federal funding for programs and services for AI/AN populations and subsequent impacts on the federal government’s capacity to implement certain programs and its ability to meet its trust obligations.[7] To address capacity challenges in the midst of resource constraints, some components within Indian Affairs, such as the Bureau of Indian Education, have previously developed strategic workforce plans.[8] In 2020, BIA signed an interagency agreement with the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to support workforce planning for its Office of Trust Services (OTS).

The IRA includes a provision for us to support oversight of the distribution and use of funds appropriated in the IRA, including ensuring the impacts of funding decisions are equitable.[9] This report examines (1) effects of IRA implementation on Indian Affairs’ existing capacity, (2) actions Indian Affairs has taken to improve capacity that could help meet workload demands under the IRA, and (3) opportunities to improve Indian Affairs’ capacity and barriers the agency faces pursuing them.

To address all three objectives, we reviewed agency documents and information about the distribution of IRA funds, as well as our prior work on Indian Affairs’ capacity and workforce planning. In addition, we interviewed agency officials from Indian Affairs components implementing IRA programs—either directly or in a supporting role—regarding changes to workload and capacity, actions taken to address these changes, and opportunities for improving Indian Affairs’ capacity.

We also identified and interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable sample of national and regional intertribal organizations.[10] We selected these organizations using criteria such as membership located in different BIA regions, familiarity with Tribes’ experiences working with Indian Affairs, and availability to meet. Additionally, we interviewed members of the Tribal-Interior Budget Council and Interior’s Self-Governance Advisory Council about their experiences with Indian Affairs’ workforce capacity. We selected these two federal tribal advisory groups based on their knowledge of Interior’s budget and resource management and their familiarity with Tribes’ experiences working with Indian Affairs.

To examine the effects of IRA implementation on Indian Affairs’ existing capacity, we reviewed relevant laws, agency documents, and reports from OPM and other entities that have examined Indian Affairs’ workforce. We also analyzed data from the Federal Personnel Payroll System for fiscal years 2022 to 2024 to identify workforce trends, such as rates of retention, for components involved in IRA implementation.[11] To assess data reliability, we conducted error checks, reviewed relevant documents, and interviewed agency officials knowledgeable about the data. Based on our assessment, we determined these data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing summary information about Indian Affairs’ workforce.

To identify actions Indian Affairs may have taken to improve capacity that could help meet IRA workload demands, we reviewed Indian Affairs’ budget justifications from fiscal years 2023 and 2024, workforce plans, and agency documents. We applied relevant criteria from our prior work and applicable federal standards for internal control to our findings from these reviews.[12]

To identify additional opportunities to improve Indian Affairs’ capacity and address barriers the agency faces pursuing them, we reviewed relevant laws, Indian Affairs policies, workforce planning and human capital management best practices, and applicable federal standards for internal control. We then applied these criteria to our findings about workforce capacity challenges and actions taken to address them.[13]

We conducted this performance audit from May 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Landmark Legislation

Since March 2020, Congress has enacted several key laws—including the IRA—that provided Tribes and programs that serve Tribes significant funding outside of baseline appropriations to address issues of national importance, such as COVID-19 relief, infrastructure improvements, and climate change.[14] Such landmark legislation created and funded several new programs and provided substantial supplemental appropriations for existing programs—including programs serving Tribes and their citizens. Federal agencies, including Indian Affairs, were tasked with implementing these landmark laws and priorities in addition to their usual responsibilities and ongoing programs.

Indian Affairs Organizational Structure and IRA Implementation

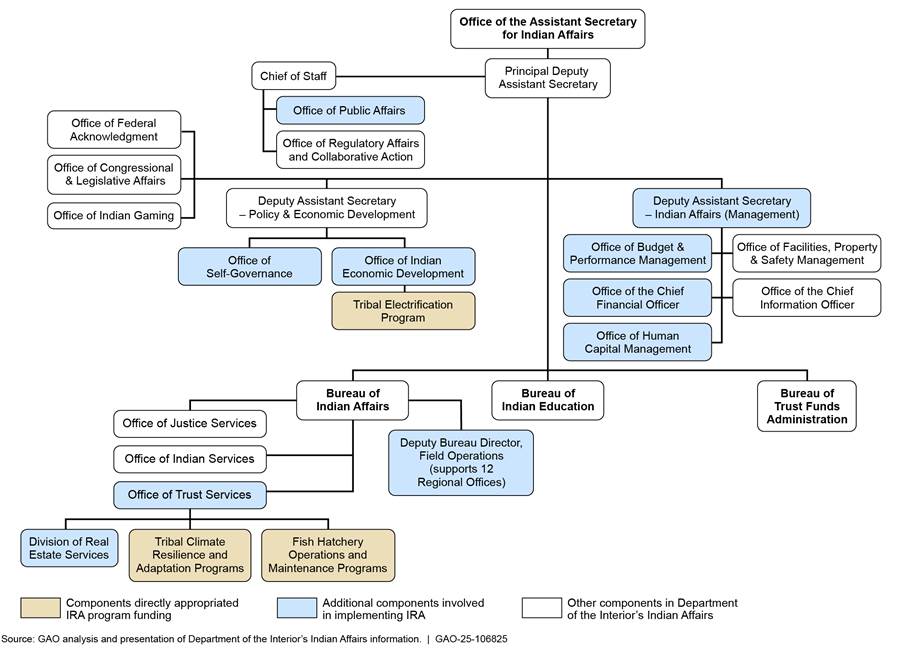

Indian Affairs consists of four components within the Department of the Interior which provide services directly to Tribes or funding for tribally administered programs. The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs assists the Secretary of the Interior in fulfilling Interior’s trust responsibilities to Tribes and individuals. Within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, three Bureaus support this mission—including BIA–and 13 components support IRA implementation, as shown in Figure 1.

Of the 13 Indian Affairs components supporting IRA implementation, three received $385 million in direct appropriations[15] to implement IRA programs:

· Branch of Tribal Climate Resilience (TCR). The Branch of Tribal Climate Resilience (TCR) received $220 million in IRA funds. TCR supports climate preparedness and resilience through technical and financial assistance, access to scientific resources, and educational opportunities. With funding from the IRA, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and annual TCR appropriations, TCR announced the largest combined award total in program history in fiscal year 2023, with over $120 million awarded to Tribal climate adaptation and resilience projects.

· Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance Programs. Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance programs received $10 million in IRA funds. These programs support hatching, rearing, and stocking programs and facility maintenance for fish-producing Tribes. For the first time, IRA enabled these programs to fund new construction in addition to maintenance.

· Tribal Electrification Program (TEP). The IRA created a new Tribal Electrification Program (TEP) to support clean energy household electrification in tribal communities. TEP received $145.5 million from the IRA that includes funding for pre-award and project technical assistance, award management, and procurement.

Ten other components also support IRA implementation in a variety of ways, including processing awards, budget operations, and hiring.

Indian Affairs’ Process for Providing Funds to Tribes

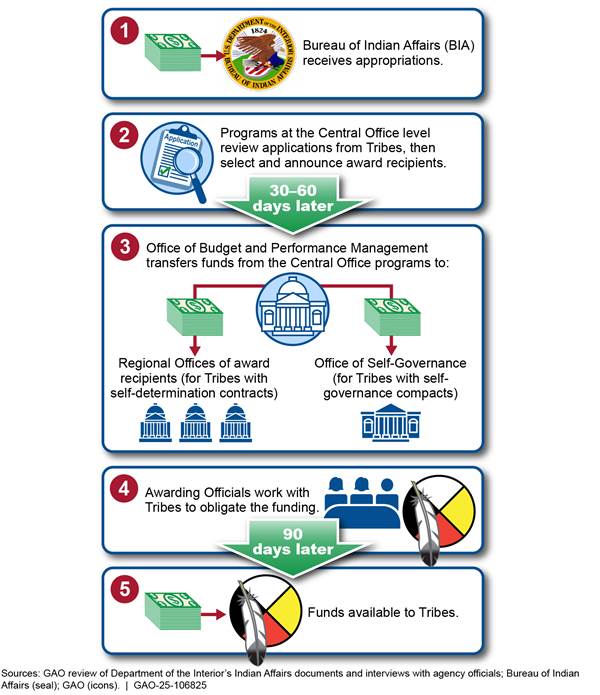

Central offices are responsible for developing policies, guidance, and training for 12 regional offices and 83 agency offices located across the country that help implement programs and deliver services or funding to Tribes. Some Tribes may choose to receive services directly from Indian Affairs. Alternatively, Tribes may choose to administer certain federal programs under a self-determination contract or self-governance compact.[16] See Figure 2 for an overview of how IRA funds flowed through this process to Tribes.

Note: Amounts for BIA Regional Offices and the Office of Self Governance are estimates for the initial round of IRA awards according to agency officials and do not add up to the total IRA appropriation.

Self-determination contracts and self-governance compacts create flexibilities for Tribes to administer federally funded programs and remove obstacles that hinder tribal autonomy.

· Self-determination contracts allow Tribes to assume responsibility for managing the program’s day-to-day operations, with federal agencies providing technical oversight to ensure that the Tribe meets contract terms and reporting requirements.

· Self-governance compacts transfer administration of the program to Tribes and provide the Tribes with some flexibility in program administration. To be eligible for participation in self-governance compacting, a Tribe must demonstrate financial stability and management capability, among other things.[17]

Federal agencies with contracting and compacting authority are responsible for negotiating and approving each contract and compact and their associated annual funding agreement and for making disbursements to the Tribes. In Indian Affairs, the Bureau of Indian Affairs is responsible for self-determination contracts and the Office of Self-Governance is responsible for administrating self-governance compacts. See figure 3 for an overview of Indian Affairs’ process for providing federal funds to Tribes through contracts and compacts.

Each Tribe decides whether, and to what extent, to pursue self-determination contracts or self-governance compacts. As of March 2020, 569 of the 574 federally recognized Tribes had a self-determination contract or self-governance compact to take over the administration of one or more federal programs from Interior, according to Interior officials. Examples include programs to manage natural resources and economic development, manage land records, and provide law enforcement services.

Awarding Officials

Awarding Officials serve a unique role in distributing federal funds to Tribes and tribal recipients. Self-determination specialists who obtain the necessary certifications can act as contracting officers and be designated as Awarding Officials.[18] Awarding Officials have signature authority to award and administer self-determination contracts and grants to Tribes and tribal organizations. Level I Awarding Official authority covers all self-determination non-construction contracts and grants, while Level II authority includes construction contracts and grants.

All Awarding Officials must demonstrate 2 years of satisfactory performance of self-determination contract experiences, complete six required courses, and have a minimum General Schedule grade of 11, among other requirements.[19] In addition to those requirements, Level II Awarding Officials must complete two additional courses, have a minimum grade level of 12, and demonstrate one additional year of experience in a self-determination contract subject area. Once certified, Awarding Officials are required to complete 80 hours of relevant self-determination and acquisition training, provided by a BIA-approved training source, every 4 years, to maintain their certification.

Impact of Long-standing Funding and Capacity Challenges on Federal Programs Serving Tribes

In July 2003 and December 2018, the independent, bipartisan U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that federal programs designed to help fulfill the federal government’s unique trust and treaty obligations to Tribes and tribal citizens have been chronically underfunded and sometimes inefficiently structured.[20] As a result, many tribal communities do not have access to the same federally funded infrastructure—such as electricity and drinking water systems—as other communities, which contributes to disparities between AI/AN individuals and other Americans.[21]

In 2018, the Commission identified underfunded programs in Indian Affairs and recommended that the federal government provide steady, equitable, and non-discretionary funding directly to Tribes to support public safety, health care, education, housing, and economic development to help address existing disparities. According to the Commission, these commitments should include increased funding for Indian Affairs programs such as real estate trust services, forestry and wildlife programs, tribal resilience, and road maintenance programs. We previously reported that improving federal capacity for working with Tribes could help agencies better design programs to meet the unique needs of Tribes, improve federal agencies’ ability to conduct meaningful consultations, and improve the quality of technical assistance for tribal recipients.[22]

We have also reported on the impact of long-standing capacity challenges on Indian Affairs’ ability to provide services to Tribes and their citizens.[23] Since 2017, our High-Risk List updates have specifically identified challenges with workforce capacity within Indian Affairs bureaus. In October 2023, we identified workforce capacity issues impeding Indian Affairs’ ability to provide services in a timely manner to support Tribes’ and individuals’ use of their land for residential and economic development purposes.[24] In March 2024, we found that a lack of workforce planning and insufficient staff capacity hinders the Bureau of Indian Education’s ability to conduct monitoring activities in schools that received COVID-19 relief funds.[25]

Human Capital Management Strategies to Address Capacity Challenges

Since 2001, we have identified human capital management as a government-wide high-risk area because of the significant challenges that federal agencies face in areas such as leadership continuity, succession planning, and acquiring and developing staff with skills that meet agency needs.[26] Current and emerging skills gaps undermine agencies’ abilities to meet their missions.[27]

We previously reported that an essential element to acquiring, developing, and retaining high-quality federal employees is agencies’ effective use of human capital flexibilities.[28] Human capital flexibilities represent the policies and practices that an agency has the authority to implement in managing its workforce to accomplish its mission and achieve its goals.[29] These flexibilities can include actions related to recruitment, retention, and training and development.[30]

Our recruitment and retention leading practices call for establishing and maintaining a strategic workforce planning process that includes developing strategies and implementing activities to address all competency and staffing needs.[31] Leading organizations engage in management efforts and broad integrated succession planning that focus on strengthening both current and future capacity.[32]

Workload Increase Due to IRA Implementation Further Strains Indian Affairs’ Existing Capacity

IRA Implementation Increased Workload for Several Indian Affairs Components

Indian Affairs components that received IRA funds directly and components supporting IRA implementation have experienced increased workload, according to documents we reviewed and agency officials we interviewed. Specifically, IRA increased the amount of funding and number of awards Indian Affairs would distribute to Tribes—and created a new program, TEP—which in turn increased components’ administrative tasks such as reporting and offering technical assistance. We previously found that the need to develop new funding distribution and reporting mechanisms for new programs could involve greater administrative burden for agency officials and Tribes.[33]

Indian Affairs components directly allocated IRA program funding. According to agency officials, Indian Affairs experienced different workload increases across each of the components that received direct funding from the IRA.[34] For example:

· TCR. As of March 2024, TCR announced 39 awards for its first round of funding ($71.6 million of its $220 million). IRA implementation increased the workload for TCR’s Regional Climate Resilience Coordinators who coordinate with BIA Regional Offices on administrative work for awards and provide technical assistance to Tribes, according to TCR officials. For example, Regional Climate Coordinators traveled to multiple conferences to share information about TCR’s IRA funding opportunities and answer questions.

· Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance Programs. As of January 2024, Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance Programs announced that it expects to award its $10 million IRA authorization to 11 projects. Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance Programs had to adapt existing processes to support new construction—as previous funding sources only supported maintenance projects—although this additional work did not increase the component’s workload significantly at the Central Office level, according to a senior program official.

· TEP. As a new program created under the IRA, TEP received appropriations in fiscal year 2022 and needed to build its staff capacity prior to making awards. As of March 2024, TEP announced 21 awards for its first round of funding ($72 million of its $145.5 million). A senior program official also said TEP created at least one new management position to oversee the progress of projects and hired contractors to provide technical assistance for applicants.

Additional Indian Affairs components implementing IRA. Officials we interviewed in the 10 other components implementing IRA said their workload also increased. These components support Indian Affairs’ awards process in some capacity. For example:

· The Office of Self-Governance (OSG). A senior OSG official said that the office has experienced an increase in its workload of preparing funding agreements and coordinating with the budget office, due in part to IRA implementation. OSG expects to distribute at least $77 million in IRA funding to Tribes with self-governance compacts for projects selected as of July 2024, according to a senior program official and information we reviewed.

· BIA’s Office of Field Operations. IRA implementation increased BIA’s Office of Field Operations’ coordination work between Central Office and the self-determination workforce in the regions. According to officials, this increase was in response to self-determination staff’s increase in work to update agreements and obligation of funding to Tribes.

· Office of Budget and Performance Management (OBPM). OBPM officials said IRA implementation increased their workload due to increased reporting requirements for IRA program budgets and performance. OBPM must also provide additional budget support to Indian Affairs components with multiple funding sources across multiple accounts, with certain accounts having their own unique restrictions, according to officials.

· Office of Public Affairs. IRA implementation increased the time and resources the Office of Public Affairs spent on communications and outreach activities, including creating social media content to promote IRA programs, according to officials from this component.

· Division of Real Estate Services (DRES). DRES officials said they anticipate significant workload increases once IRA-funded construction projects begin. For example, according to officials, construction projects will require additional rights of way, leases, and permits, thus increasing the administrative and regulatory workload for BIA and Tribes. Moreover, TCR and Fish Hatchery projects often involve environmental assessments and compliance with different regulatory requirements that can further increase the component’s workload, according to officials.

Long-standing Capacity Issues Exacerbated by Competing Priorities

Components implementing the IRA have been operating with long-standing capacity challenges, including limited mission critical staff and issues with retention, making it difficult to meet mission needs across competing priorities, according to our analysis of Indian Affairs’ data, documents, and interviews. For example:

· Limited self-governance workforce. According to a senior program official and information we reviewed, OSG has a workforce of 15 staff members, with one Awarding Official authorized to obligate funding to 286 Tribes through 140 funding agreements.[35] Officials stated that OSG will need to distribute approximately $82.1 million for 66 TCR and TEP projects funded by IRA in the initial round of awards and other funding sources. Currently, OSG prioritizes responsibilities that have a statutory deadline, which limits OSG’s ability to assist with other tasks related to IRA implementation or technical assistance for Tribes, according to a senior official. For example, this official told us that OSG has not been able to offer sufficient audit support to Tribes due to competing priorities. This official also said that OSG currently does not have sufficient staff to enforce many of the statutory deadlines for different regulations. Moreover, OSG lacks the resources and staff capacity to implement ideas from self-governance Tribes on how best to support them, according to this official.[36] Representatives from a federal tribal advisory group we spoke with also told us that limited self-governance staff hinders communication between OSG and BIA’s budget offices.

· Limited capacity of Awarding Officials. According to officials from the Office of Indian Services, current Awarding Officials have absorbed the additional workload from implementing the IRA and other major funding streams implemented since 2020, leading to high overall workload and strain on these staff. Awarding Officials balance their responsibility to process awards with other duties to serve self-determination Tribes, such as technical assistance, contract support, audit support, and administrative duties, according to officials.

Additionally, as of March 2024, Indian Affairs estimates that 31 of the 71 projects funded by the initial round of IRA awards will include construction.[37] However, only six of the 33 Awarding Officials across BIA are certified as Level II Awarding Officials and have the authority to approve awards for construction projects.[38] Officials from most components we spoke with told us that the limited capacity of Awarding Officials is a challenge given the increasing amount of funding to distribute to Tribes (see fig. 4).[39]

Note: The number of IRA-funded projects is based on information Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs officials provided in March 2024 and includes projects from the first round of IRA awards. The number of construction and non-construction projects is an estimate as the construction status of Fish Hatchery Operations and Maintenance projects (11) is unknown, and officials said the list of projects is preliminary.

According to Indian Affairs budget officials, BIA Awarding Officials have had to process an increasing amount of funding since 2019, but the number of actions taken to process awards has not kept up with the increased funding amount during this time period. Officials said these trends indicate Awarding Officials are experiencing challenges processing the awards. One senior program official told us that, when measuring workload by the number of actions needed to manage contract awards or modifications, BIA’s Office of Field Operations found that its self-determination workforce across regions managed an average of 145 actions per person per year. According to this official, this indicates a greater workload than staff performing similar work at another agency and could limit the ability of BIA staff to manage workload.[40] This official told us the component’s goal is to increase the self-determination workforce to 153 fulltime equivalencies (FTEs) in fiscal year 2025 to better meet current workload demands.[41] However, the official said that an optimal workforce size would be approximately 200 FTEs to manage the current workload and improve functions such as technical assistance to Tribes, contract closeouts, and workforce development.

|

Importance of Timely Disbursement of Funds to Tribes Representatives from a national tribal organization we spoke with described examples of when Indian Affairs’ limited capacity led to delays in funding for Tribes, potentially hindering infrastructure development. As reported by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, delayed funding can have a significant impact on program planning and operations, including budgeting, recruitment, retention, service delivery, facility maintenance, and construction. Construction projects in some locations are particularly time-sensitive, making the need for timely disbursement of funds more acute. Delays in funding from Indian Affairs—due to issues such as limited self-governance workforce or Awarding Officials’ capacity—could lead to Tribes missing a seasonal window for large-scale projects and effectively extend project timelines. For example, in parts of Alaska, construction for energy projects can take place only during certain seasons, since heavy equipment and supplies must be transported on the tundra when the ground is frozen and brought to the site via sled. Pictured below is a wind generation project that one village had to put on hold due to lack of available equipment.

Sources: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Broken Promises; GAO interviews with tribal officials; and GAO (photo). | GAO‑25‑106825 |

Moreover, there is a backlog in training for Awarding Officials to maintain their certifications. For example, in January 2023, Indian Affairs directed Regional Directors to waive certain training requirements for Awarding Officials because the Office of Indian Services did not have the resources to provide or develop required training.[42] Representatives from a federal tribal advisory group and a national tribal organization told us they are aware of the limited capacity of Awarding Officials across the agency. In light of this, the advisory group requested that the agency prioritize efforts to address skills gaps, such as for Awarding Officials, that hinder Indian Affairs’ ability to fulfill its obligations to Tribes.

· Vacancies. A significant number of vacancies exist throughout the agency, according to officials we interviewed in most of the components in our scope.[43] For example, as of July 2024, BIA’s Office of Field Operations officials told us 56 of 125 self-determination workforce positions were vacant.[44] According to a senior OSG official and representatives we spoke with from a national tribal organization, understaffing—particularly in BIA regional offices—has affected Indian Affairs’ ability to provide funds to Tribes in a timely manner.[45] In addition, representatives from a national tribal organization told us that understaffing also led to delays in responding to requests from Tribes. According to officials we interviewed in several components, Indian Affairs has used details, or temporary reassignments, to provide temporary assistance managing workload.

· Work hours. According to our analysis of Indian Affairs’ data, from fiscal years 2022 through 2023, employees in components involved in IRA implementation have worked longer hours over time.[46] For example, there were 50 instances of OSG employees working more than 80 hours in a pay period in fiscal year 2023, resulting in an additional 674 hours worked. In fiscal year 2023, there were 1,272 instances of OTS employees working more hours than the standard pay period hours, resulting in almost 23,000 additional hours worked. Indian Affairs employees generally demonstrate a deep commitment to the agency’s different missions, according to agency officials and representatives from federal tribal advisory groups. Officials told us that increasing workload demands and understaffing may be associated with working longer hours, which can in turn contribute to burnout and separations. DRES and OSG officials said their staff regularly use overtime and compensatory time to help meet workload demands. Programs have needed to work with existing staff resources that are already at capacity.

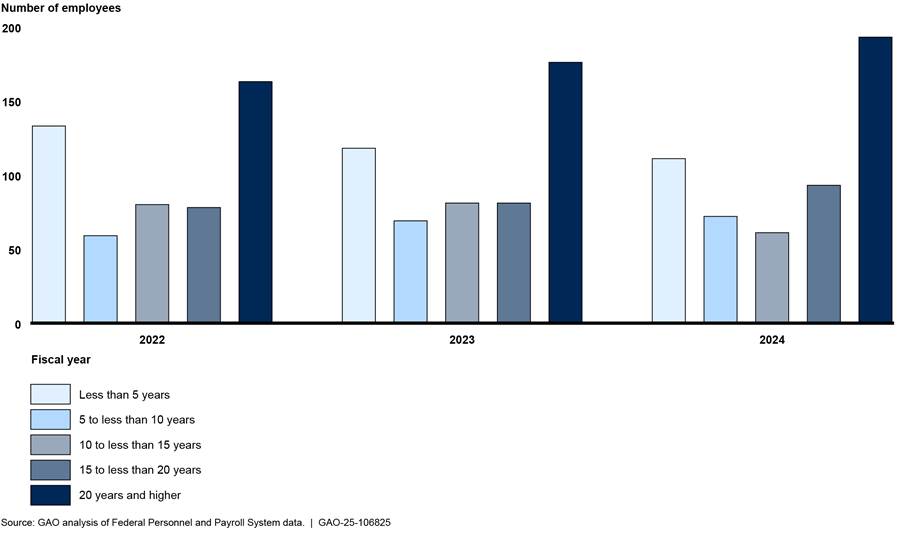

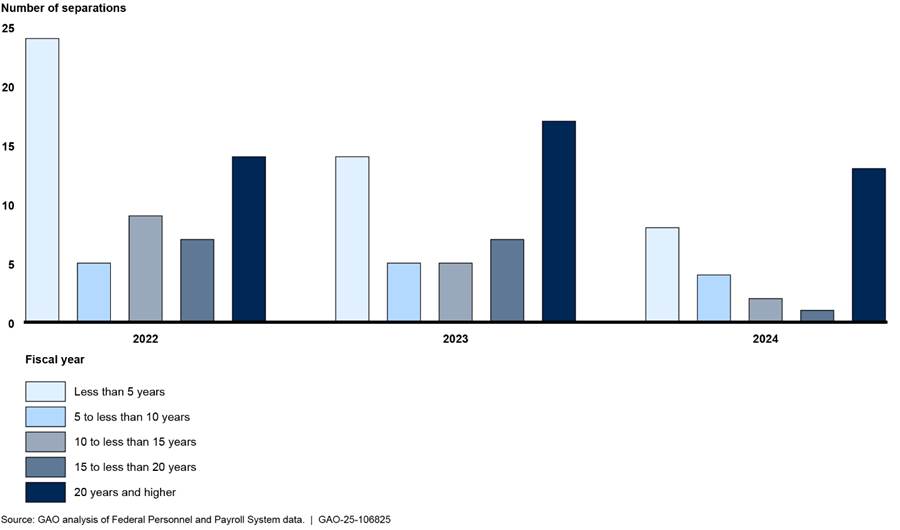

· Retention. According to our analysis of Indian Affairs personnel data, components involved in IRA implementation have experienced overall increasing rates of retention since fiscal year 2022, from 88.5 percent in fiscal year 2022 to 90.9 percent in fiscal year 2023.[47] However, separations for these components were highest among staff with less than 5 years of service and staff with over 20 years of service, who also make up the two largest groups of staff (see figs. 5 and 6). Moreover, retention rates vary by component.[48] Some agency officials also said their component lost staff during the pandemic. In addition, representatives from federal tribal advisory groups have stated there is constant leadership turnover at Indian Affairs.

Note: Data represent headcount as of the first pay period of each fiscal year. Data include the following Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs components involved in implementing the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Office of Field Operations, Office of Budget and Performance Management, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Office of Human Capital Management, Office of Indian Economic Development, Office of Public Affairs, Office of Self-Governance, and Office of Trust Services.

Note: Data represent voluntary and involuntary separations in each fiscal year, through March 23, 2024. Data include the following Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs components involved in implementing the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Office of Field Operations, Office of Budget and Performance Management, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Office of Human Capital Management, Office of Indian Economic Development, Office of Public Affairs, Office of Self-Governance, and Office of Trust Services.

Indian Affairs Has Leveraged Resources and Taken Actions to Improve Capacity to Help Meet IRA Workload Demands, but Needs to Identify Lessons Learned

Indian Affairs Has Leveraged Various Resources Strategically to Help Meet IRA Workload Demands

According to documents we reviewed and officials we interviewed, Indian Affairs has strategically used funds from the $9.5 million appropriated for IRA administrative costs and supplemented this funding with baseline appropriations to hire staff and contractors to help meet IRA workload demands.[49] However, Indian Affairs has not yet documented lessons learned from its use of these resources and their sufficiency in meeting IRA workload demands.

Indian Affairs officials said components have used IRA administrative funds to hire fulltime staff and leverage contracting tools.[50] For example, these officials said that TEP used these funds to hire a program manager to oversee funded project progress. In addition, TEP is hiring eight contractors to provide administrative support to Indian Affairs staff and technical assistance to Tribes applying for and receiving TEP funds, according to a senior program official.[51] TCR is also hiring contractors to assist with administrative actions related to awards, according to officials. Indian Affairs components supporting IRA implementation are also using IRA funds to increase their capacity. For example, according to documents we reviewed, the Office of Budget and Performance Management plans to hire four contractors to provide analytical assistance with managing the projects and funding received under the IRA.

Indian Affairs officials told us that they routinely review IRA program implementation with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs and Interior’s Program Management Office to determine the most effective use of IRA administrative funds based on needs and identify any immediate resource gaps.[52] According to officials, having flexibility in the use of administrative funding is generally helpful, as every Indian Affairs component and IRA-funded program has unique needs. For example, according to officials, TEP is funded entirely by the IRA and does not have baseline appropriations. As a result, TEP will use the largest share of funds for IRA administrative costs. Appropriations for IRA provisions implemented by BIA are available from August 16, 2022, through September 30, 2031, and officials stated that they balance using funds based on current needs with reserving funds to meet future needs over this period of implementation. As of May 2024, Indian Affairs has obligated approximately $1.9 million of its multi-year IRA funds for administrative costs and estimates it will obligate an additional $2 million by the end of the fiscal year, according to officials.

Indian Affairs components have also used baseline appropriations to help meet IRA workload demands. For example, TCR officials also told us they used baseline appropriations to hire contractors to provide technical assistance to Tribes during the construction phases of projects. TCR also doubled the amount it allocates to Regional Offices to support new positions, staff training, and climate resilience work, according to officials. Some components supporting IRA implementation requested more FTEs during the budget cycle, in part to help manage increased workload due to IRA and other responsibilities. For example, OPA added two new FTEs and DRES requested 12 new FTEs for fiscal year 2024, according to officials and agency documents we reviewed. Other components, such as OSG, absorbed the increased workload with existing staff resources, which limited OSG’s ability to perform other tasks, according to a senior program official.

Indian Affairs continues to implement IRA programs and so has not yet documented successes and lessons learned from its use of funds for IRA administrative costs. In particular, the agency has not documented the extent to which it needed to use baseline appropriations to meet increased workload demands and the impact doing so had on other mission needs. For example, TEP officials stated that the availability of IRA funds authorized for administrative costs enabled them to avoid using program funds to cover administrative costs for IRA implementation, which could have reduced funding available for Tribes. In addition, officials said that time-limited legislation like the IRA limits the ability to hire FTEs because future funding for those positions is uncertain, so Indian Affairs often leverages contracting tools to support implementation.

We previously found that organizations that identify and apply lessons learned can ensure they factor beneficial information into planning for future efforts and limit the chance of the recurrence of challenges that can be anticipated in advance.[53] Moreover, federal internal control standards state that management should use quality information to achieve objectives. Collecting and sharing successes and lessons learned from the first half of when appropriations are available for the IRA provisions implemented by BIA—by March 2027—could help Indian Affairs use quality information to more effectively plan for future use of funds for administrative costs.

Additionally, when Congress has decided to authorize funds for Indian Affairs’ administrative costs outside of baseline appropriations, Indian Affairs’ lessons learned could help Congress determine amounts for future program implementation. Based on our analysis of sample agency-administered federal financial and technical assistance provisions in the IRA that expressly address program administrative costs, the 2.5 percent authorized for Indian Affairs’ associated administrative costs—$9.5 million out of the total $385 million appropriation—was a lower proportion of administrative expenses than for some other such provisions.[54] In particular, agency administrative cost appropriations for the bulk of Environmental Protection Agency federal financial and technical assistance provisions in the IRA ranged from 2 to 7 percent of total program appropriations.[55] For Department of Energy assistance provisions in the IRA, a majority specify a limit of 3 percent of total program appropriations for administrative expenses—or administrative costs and technical assistance—with two provisions at 5 percent or higher.[56] Interior, other than Indian Affairs, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture also have largely similar administrative cost proportions for such provisions.[57]

As discussed previously, Indian Affairs provides a range of services and funding that play a key role in carrying out the federal government’s trust responsibilities to Tribes and their citizens. This includes administering programs in some of the most remote areas of the country and managing funding agreements with 574 federally recognized Tribes, each with different needs and levels of resources. Given this unique role, sharing findings from its review of lessons learned with Congress could help Indian Affairs inform future appropriations and legislation deliberations to ensure it has the resources needed to implement future programs.

Indian Affairs Has Taken Actions in Certain Areas of Human Capital Management to Improve Capacity to Help Meet Overall Workload Demands

According to agency documents and officials, Indian Affairs has taken actions related to different areas of human capital management—recruitment and hiring, training and development, and workforce planning—to improve its capacity to help meet overall workload demands, including IRA implementation.

Recruitment and Hiring

Indian Affairs has taken several recruitment and hiring actions to improve capacity, according to agency documents and officials. These actions include increasing recruiting efforts, standardizing position descriptions and continuously listing mission critical positions, using internal experts and building an applicant pool to identify candidates, and updating human resources technology. For example:

· Expanding outreach to recruit new talent. Indian Affairs has taken steps to improve outreach to Tribes and provide application assistance to candidates. For example, in response to an October 2022 OPM audit report, the Office of Human Capital Management (OHCM) established a Strategic Talent Acquisition and Retention process and a standard operating procedure to track past recruitment activities to identify strategies and address recruitment inefficiencies. Steps taken under this process include attending recruiting events in tribal communities and universities, offering new pathways to hire recent college graduates, and enhancing social media presence. In March 2023, OHCM also began developing standard operating procedures for recruiting for high priority vacancies that include increased collaboration across OHCM, OPA, and hiring managers to ensure effective external communications. However, officials also told us that there is one staff member leading recruitment outreach efforts, and they do not have enough staff and resources to support current needs.

· Standardizing position classification. Since 2022, Indian Affairs has taken steps to standardize position classification and reduce job posting delays by developing a position description library for hiring managers. Officials have targeted mission critical occupations, such as realty officers and certain specialists and assistants, to identify pending position classifications and put standard position descriptions in place.

· Continuously listing open critical positions. According to officials, continuously listing open positions nationwide for realty specialists has helped Indian Affairs hire for this critical position without needing to relist it periodically if the agency does not fill it within the listed period, which OHCM must do for other positions. Officials are expanding the use of this approach to other positions OHCM has identified as critical, such as probate and social work positions. For example, in July 2024, officials told us they began continuously listing an open position in BIA’s social services department.

· Leveraging internal expertise. According to officials, OHCM uses subject matter experts in different components whose expertise could help OHCM identify relevant prior work experience with Tribes when setting salary and General Schedule levels.[58] For example, OHCM officials said that, to help fill critical realty vacancies, DRES employees help identify applicants with backgrounds in real estate services. These applicants reflect the specialized knowledge DRES needs but might otherwise not get through the hiring process because their prior work experience is not properly evaluated.

· Building an applicant-ready pool. In March 2023, Indian Affairs began implementing an approach to accelerate the hiring process, according to officials. Under this approach, applicants who are eligible for AI/AN preference hiring complete the background investigation process and join a pool of candidates that can be onboarded quickly when the agency determines they meet qualifications for a listed position.[59]

· Modernizing human resources technology. According to officials, in January 2024, Indian Affairs began implementing USA Staffing as the system of record for position classification and recruitment actions.[60] Indian Affairs also developed a dashboard that uses data from USA Staffing to give hiring managers visibility into certain hiring process metrics, such as time to hire. Doing so would enable them to track key milestones throughout the hiring and onboarding process for their component, according to agency documents and officials. The dashboard would provide a central location for human resources to collaborate with hiring managers throughout the hiring process. Officials told us they expect to implement the dashboard for all BIA hiring managers, including those in regional offices. However, officials stated that they could use additional staff with expertise in human resources information systems to implement the dashboard and manage overall workload.[61] Officials told us they are developing a Standard Operating Procedure to ensure that all staff follow the same processes for entering information into USA Staffing.

Training and Development

Indian Affairs is taking steps to improve training and development for its existing workforce. For example, according to information we reviewed, BIA’s Office of Field Operations scheduled training sessions for regional office staff to address the backlog in training for Awarding Officials and self-determination specialists more broadly. In addition, OHCM officials told us they are educating hiring managers on different hiring authorities and recruitment strategies, as well as how to maximize their use of USA Staffing capabilities. In early 2024, they also began training internal subject matter experts to support hiring actions, particularly for hard-to-fill positions that require specialized knowledge, according to officials. OHCM also stated they partnered with the White House Council on Native American Affairs to offer new training opportunities on self-determination and Native Nation rebuilding.

Workforce Planning

Indian Affairs has taken several actions related to workforce planning to improve capacity, according to agency documents and officials. For example, Indian Affairs is working with OPM to support workforce planning. In addition, OHCM has established new divisions and has worked with other components to enhance human capital management and identify workforce trends and barriers. OHCM has also created a reserve of employees available for details. Specifically:

· Collaborating with OPM. In July 2020, BIA signed an interagency agreement for OPM to support OTS with strategic organization analysis, workforce planning, succession planning, competency modeling, and related human resources consulting and training. Under this agreement, for example, OPM surveyed supervisors and conducted competency modeling and gap analyses for positions such as realty specialists and irrigation systems operators.[62] The period of performance for this work will end in July 2025. In April 2022, the agencies signed a separate agreement for OPM to provide ongoing classification and position management support to OTS. As of April 2024, the period of performance for this work will end in April 2025.[63]

· Enhancing human capital management capabilities. As of April 2023, OHCM established three divisions to enhance human capital processes, performance, and accountability across Indian Affairs: Human Resources Policy and Programs, Workforce Development, and Human Resources Strategic Planning & Evaluations. The new divisions are responsible for developing human resources strategies and short– and long-term solutions to modernize policy, data, and human capital oversight.

· Analyzing workforce trends. In fiscal year 2023, OHCM conducted additional analyses with the Office of Justice Services and OTS to support workforce planning, according to documents and officials. For example, OHCM analyzed trends in hiring, time to hire, and attrition for OJS and developed hiring goals based on this analysis. For both OJS and OTS, starting in February 2023, OHCM identified barriers that can reduce the number of applicants successfully completing the application process, according to officials. OHCM officials said they want to expand these types of analyses to other Indian Affairs components. OHCM officials also stated that they have biweekly meetings with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs’ management to address workforce planning efforts across components, funding for these efforts, and positions that need to be filled.

· Using details to meet immediate workforce needs. OHCM officials told us that, since 2022, they have issued an annual call for applications from mid-level managers interested in serving in a detail capacity as a Regional Director or Deputy Regional Director when there is a need. This option provides managers an opportunity to perform at an SES level and maintains some leadership continuity in BIA regional offices, according to officials. Although temporary, details help support a workforce that could otherwise burn out meeting workload demands while the agency tries to fill vacancies, according to OHCM officials.[64]

Indian Affairs Identified Opportunities to Improve Its Capacity but Needs Greater Efficiencies and Sustained Investment to Overcome Implementation Barriers

Opportunities Exist to Improve Indian Affairs’ Capacity through Human Capital Management

There are additional opportunities for Indian Affairs to improve its capacity by pursuing several human capital management strategies, based on our review of prior Indian Affairs’ workforce planning documents, OPM standards, key talent management strategies, and interviews.[65] Currently, Indian Affairs does not effectively track vacancy data needed for succession planning and has not completed a full workforce analysis of skills and competencies needed for workforce planning. Officials identified other opportunities they are interested in pursuing to improve capacity in recruitment and hiring, as well as training and development.

Actions to Improve Succession Planning and Workforce Planning

We and OHCM officials identified certain actions Indian Affairs could take to help improve succession planning and workforce planning at the agency. If taken, these actions could help improve long-term capacity at Indian Affairs. Specifically,

· Track vacancy data to help improve succession planning. OHCM officials said tracking vacancies centrally across Indian Affairs would enhance their ability to conduct succession planning because they need this information to know what regions to prioritize, set agencywide hiring goals, and track these goals. We previously hosted a forum of federal human capital officers, during which participants said that workforce planning challenges often arise because, in part, their agencies may lack

o data needed to anticipate when employees will leave their positions and will need to be replaced, and

o consideration of whether a vacant position needed to be filled or what skills would be needed in the future to do that job effectively when making hiring decisions.[66]

Currently, each component and region tracks vacancies separately and Indian Affairs does not track this information across the agency, according to officials.[67] OHCM officials told us that the only way to know the number of vacancies across components would be through a manual data call, such as sending out spreadsheets to regions and components to complete. Federal standards for internal control also state that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[68] Tracking vacancies across Indian Affairs would allow OHCM to use this information to conduct effective succession planning. Officials and representatives from a federal tribal advisory group and a tribal organization told us that, without addressing existing succession planning challenges, Indian Affairs will continue to face retention challenges and vacancy rates that will ultimately be detrimental to Tribes.

· Assess skill and competency gaps across Indian Affairs to enhance workforce planning. We previously found that some Indian Affairs components had not identified key skills needed to fulfill mission needs and associated skill gaps.[69] As part of its interagency agreement with BIA, OPM has conducted but not completed strategic organization analysis and competency modeling for OTS.[70] OHCM also developed hiring goals for two components but has not conducted workforce analyses across more Indian Affairs components.

Our key talent management strategies state that agencies need to assess whether they have gaps in existing and future skills and competencies.[71] OHCM created new divisions focused on policy and strategic planning in part so OHCM could better support workforce planning efforts across the agency, according to officials. Identifying skills and competency gaps in mission-critical occupations across Indian Affairs could help OHCM develop agencywide strategies to close these gaps and help meet OPM’s talent management system standard.[72] Doing so could also help Indian Affairs identify how it could leverage skills, knowledge, and resources across the agency to improve its overall capacity, rather than consider each component separately.

Additional Opportunities to Improve Capacity

Officials we interviewed identified several other opportunities for improving capacity. They described ways that they could leverage flexibilities, authorities, and waivers to address challenges in recruitment and hiring. They also acknowledged that additional training and workforce development is needed but said that their ability to implement new efforts is limited by current capacity issues. OHCM officials said they devote most of their limited staff capacity to responding to issues and then do not have much capacity to implement many new efforts, such as the ones described below. Specifically,

· Leverage remote work flexibilities to expand applicant pool and improve retention. Officials we interviewed said that remote work options help make Indian Affairs more competitive with other agencies for the same candidate pool, especially for hard-to-fill positions.[73] Officials also said remote work options can reduce the need for relocation incentives and allow components to offer additional incentives, such as student loan repayment. These officials also said that, for over 15 years, one component faced difficulties recruiting AI/AN preference candidates for a position but filled the position once the component offered a remote option. In July 2023, Interior amended its telework and remote work posture generally to require that requests to work remotely be approved at the Assistant Secretary level and that certain managers resume in-office work requirements. Officials said they did not know if the new requirements will lead to increased voluntary separation or impact hiring.

· Leverage existing authority to use AI/AN preference in recruitment to expand applicant pool. OHCM officials said they would like to maximize use of AI/AN preference in recruitment by, for example, identifying AI/AN preference candidates whom the agency did not select for a position but meet qualifications for another position. According to officials, this flexibility can be especially beneficial for vacancies with the same occupational title, series, and grades, and would reduce the time it takes the agency to hire since hiring managers and OHCM would not need to relist the position. OHCM officials told us Interior’s Chief Human Capital Officer is considering extending job announcement periods from 90 to 120 days so they have more time to contact eligible preference candidates about other positions.

· Leverage waiver processes to streamline Interior’s hiring process. OHCM officials said Indian Affairs could use the personnel investigation waiver process when feasible and maximize the reciprocal acceptance of background investigations and national security adjudications from other federal agencies. They said this could speed up the hiring process and limit the loss of applicants who do not want to wait for a long federal process.

· Train a more adaptable workforce. OHCM officials said a workforce trained in a range of less-specialized, more general skills could use these skills across roles and help Indian Affairs adapt more easily to changing workloads, potentially creating opportunities that are not as time-limited. Certain Indian Affairs positions, such as many realty positions, are not permanent or full-year, and landmark legislation like the IRA provided time-limited supplemental appropriations outside of the baseline appropriations. OHCM officials said this creates challenges with finding and retaining interested candidates who might be interested in permanent positions.

· Address known training gaps. Indian Affairs officials indicated that they planned to implement new training related to human resources policies or hiring authorities, such as the application of AI/AN preference in position announcements, employee engagement strategies, and performance management activities.[74] Moreover, OHCM officials told us that additional training in classification and position management could help streamline the process for filling positions to avoid bottlenecks. However, OHCM officials stated that they still face significant unmet training needs because of limited staff and resources.

Efficiency Improvements and Sustained Investment Needed to Overcome Barriers That Impede Indian Affairs’ Capacity

Efficiency challenges with certain internal communication and agency processes pose barriers that limit Indian Affairs’ capacity, based on our review of agency documents and statements from agency officials. Moreover, agency officials told us that budget uncertainty and current authorities impede sustained investment in capacity-building that would help Indian Affairs better absorb and manage its increased workload.

Communication and Process Efficiencies

Indian Affairs faces certain internal communication challenges that limit its capacity, based on our review of agency documents and statements from agency officials.

· Internal communication. Indian Affairs and its components do not have written guidance that describes how hiring managers could use authorities and incentives as recruitment tools. Without written guidance, inconsistent use of existing hiring authorities, recruitment incentives, and workforce flexibilities for recruitment purposes limits the applicant pool, according to OHCM officials. For example, officials from different Indian Affairs components have varying perspectives on which positions qualify for AI/AN preference, so they may not be leveraging this preference whenever possible to encourage qualified AI/AN candidates to seek employment with the agency.[75] In addition, OHCM officials said not all hiring managers know that they are responsible for defining incentives as part of their recruitment strategy and that they have the authority to do so. We found that agencies’ human capital offices need to ensure that they have effective campaigns not only to inform managers of their personnel authorities, but also to explain the situations where the use of those authorities is appropriate.[76] In addition, in August 2024, OPM and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued guidance identifying efforts agencies should prioritize for recruiting, retaining, and advancing talent needed for agency missions. These efforts include ensuring that hiring managers are aware of and empowered to use the full range of hiring authorities and assessment strategies available to them, particularly those that relate to critical, specialized, or hard-to-recruit skills, and that they are aware of allowable recruitment activity.[77] Consolidated written guidance, consistent with our key practices for effective use of human capital flexibilities, could help Indian Affairs meet these standards and more consistently leverage hiring authorities, recruitment incentives, and workforce flexibilities to increase its applicant pool.[78]

· Processes. OHCM officials said that burdensome application and hiring processes could dissuade applicants from pursuing positions with Indian Affairs. OHCM and other components have taken actions and identified opportunities to streamline the process, as we discussed, but certain barriers remain outside of Indian Affairs’ jurisdiction. For example, OHCM officials said the process for verifying eligibility for AI/AN preference includes duplicative steps for applicants and outdated OMB forms.[79] Officials said they have discussed updating these forms with OMB.

Sustained Investment in Indian Affairs Funding, Capacity-Building, and Human Resources

Budget uncertainty—due to continuing resolutions and short-term funding streams—impedes sustained investment in capacity-building efforts that would help Indian Affairs better absorb and manage its increased workload, based on our review of prior work and statements from agency officials we interviewed. In addition, officials told us that Indian Affairs could benefit from more investments in human resources than its current authorities allow.

· Indian Affairs Funding. In 2018, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that, since 2003, federal funding for AI/AN programs mostly remained flat, barely kept up with inflation, or actually resulted in decreased spending power.[80] Moreover, chronic underfunding exacerbates challenges faced by AI/AN populations and can lead to more costly problems over time, according to the Commission. For example, the Commission found that chronic underfunding leads to deferred maintenance in AI/AN schools, contributing to accelerated deterioration of buildings and systems and higher long-run upkeep and repair costs, which in turn impacts student safety and learning.[81] We previously found that constraints in federal funding and budget uncertainty limit effective delivery of some federal programs and activities serving Tribes.[82]

In addition to historic constraints in federal funding, continuing resolutions and short-term funding streams—with priorities changing across administrations—limit Indian Affairs’ ability to hire permanent staff due to budget uncertainty, according to officials we interviewed. For example, continuing resolutions keep Indian Affairs at status quo in terms of its budget, and the agency cannot undertake new initiatives—including efforts to improve capacity—until Indian Affairs receives regular appropriations, according to senior officials.[83] We found previously that budget uncertainty effects include challenges with recruitment and retention of staff and additional administrative burden and costs for both Tribes and agencies.[84]

· Capacity-building efforts. Our prior work on strategic human capital management notes that high-performing organizations leverage modern technology to automate and streamline personnel processes to meet customer needs.[85] In addition, efforts for prioritizing recruiting, retaining, and advancing talent needed for agency missions from OPM and OMB’s August 2024 guidance include agencies investing in modern, standardized human capital systems and automated tools. Such investments would allow agencies to complete routine tasks more efficiently and to expedite administrative elements of the hiring process.[86] As discussed, officials hope the USA Staffing dashboard helps improve capacity to meet mission needs but said the agency would need more resources to implement additional dashboard capabilities, such as tracking vacancies, to help Indian Affairs with certain aspects of human capital management. We found previously that having IT tools alone did not resolve BIA’s management challenges, and that BIA needs oversight measures and quality control processes for managing data in place to ensure its IT tools are used effectively.[87] If OHCM officials have sustained resources in place to support IT tools that track information critical to human capital management, such as vacancies, they could more effectively implement workforce planning strategies to address long-standing capacity challenges.

Officials also told us that additional training, including for Awarding Officials, could help improve capacity for Indian Affairs to implement IRA programs. As discussed, there is a backlog in training for Awarding Officials to maintain their certifications, and Office of Indian Services officials said Indian Affairs had to waive certain training requirements due to lack of resources to provide or develop required training. Officials told us this lack of access to training prevents officials from earning and maintaining Awarding Official certifications, which continues to limit the capacity of Awarding Officials.[88] The cost of additional training for Awarding Officials would not be eligible for IRA administrative funds because the training would enhance general skills and knowledge not specific to the IRA, according to officials. In addition, while OHCM officials told us about new training they are implementing or hope to implement, they also said they have limited capacity to prepare and tailor new training.

· Human resources. Officials told us that Indian Affairs’ current authorities limit its ability to make sustained investments in human resources. For example, OHCM officials said the recruitment incentive for positions in hard-to-fill locations should be increased above the current authorized maximum of 25 percent of base salary because this is generally not sufficient for Indian Affairs to remain competitive for applicants.[89] In addition, applicant fallout and hiring delays can occur in part due to discomfort when Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency officials conduct background investigations on reservation land, according to OHCM officials. OHCM officials said that Indian Affairs does not have the authority to conduct background investigations or transfer this authority to Tribal law enforcement for these positions.

OHCM officials also told us that they do not have the human resources staff to meet workload needs, because right now they have just enough staff to address crisis situations rather than focus on longer-term workforce efforts, such as strategic planning and recruitment. As discussed previously, OHCM officials stated they have one official to conduct outreach activities for recruiting applicants. As of June 2024, OHCM had two senior level vacancies and two senior officials serving in acting roles out of 17 senior level positions, according to officials. In addition, OHCM officials told us they had eight staff vacancies, including three unfunded vacancies. As of March 2024, 25 percent of separations across Indian Affairs components involved in IRA implementation in fiscal year 2024 have been for staff in human resources roles.[90] We found previously from a forum of federal human capital officers that workforce planning challenges often arise because, in part, their agencies may lack human resources personnel with necessary skills and experience to conduct workforce planning and consistently monitor and evaluate associated outcomes.[91] In April 2024, a senior official told us that Indian Affairs has sufficient staff to set up and begin using the new USA Staffing dashboard to monitor hiring data, and the agency would assess staff needs as more hiring managers use the dashboard.

Indian Affairs’ budget uncertainty and current authorities have affected its capacity and ability to plan and manage its workforce, including decisions to hire, retain, train, and contract. We have previously found that careful attention to strategic workforce planning and other approaches to managing and engaging personnel is necessary to mitigate detrimental effects of fiscal constraints on an agency’s capacity to meet its mission.[92] Sustained investment in capacity-building efforts, such as data-driven succession planning, competitive recruitment incentives, and process improvements, could help ensure Indian Affairs has the human capital needed to effectively provide services to Tribes and their citizens and meet the federal government’s trust responsibilities.

Indian Affairs has begun exploring legislative opportunities that could help improve its capacity, but it has not developed a proposal to request legislative authority or specific resources to support a sustained investment in pursuing these opportunities. In previous reports and testimonies, we have emphasized that, in addressing their human capital challenges, federal agencies should first identify and use the flexibilities already available under existing laws and regulations and then seek additional flexibilities only when necessary and based on sound business cases.[93] By developing a proposal that identifies opportunities to improve its capacity with flexibilities already available under existing laws and regulations and the resources necessary to pursue them, and then sharing that proposal with Interior, Indian Affairs would better understand and communicate its needs. Further, sharing the proposal’s identification of legislative opportunities with Congress for its consideration could lead to additional changes to improve Indian Affairs’ workforce capacity and ability to manage its programs.

Conclusions

Consecutive federal assessments have found that federal programs designed to help fulfill the federal government’s unique trust responsibility to Tribes have been chronically underfunded and sometimes structured inefficiently. As a result, many tribal communities do not have access to the same federally funded infrastructure as other communities to meet their basic needs. We have previously found that many of these programs have faced long-standing capacity challenges, including limited staff and issues with retention. Such circumstances make it difficult for components to meet mission needs across competing priorities, such as new programs and policy goals established by landmark legislation that provides Tribes funds outside of baseline appropriations. The IRA appropriated approximately $385 million to BIA for programs that support Tribes. While three BIA components received direct funds to implement and administer IRA programs, 10 other Indian Affairs components also support IRA implementation. Officials from these components told us that implementing IRA programs increased their components’ workload and exacerbated existing capacity challenges.

Indian Affairs has strategically used IRA administrative funds to hire staff and contractors to help meet the additional workload demands. Indian Affairs has not yet documented lessons learned from its use of IRA administrative funds but collecting and sharing such lessons from the first 5 years of IRA implementation could help Indian Affairs use quality information to plan for future IRA administrative costs. Indian Affairs could then share these lessons learned with Congress. If Congress authorizes administrative funds in future legislation that supports tribal recipients outside of baseline appropriations, Congress could consider these lessons learned to ensure it has quality information to help determine the amount needed for effective program implementation.

Opportunities exist for Indian Affairs to improve its capacity through different human capital management strategies that could help components implementing the IRA more effectively meet their overall workload demands. However, in some cases, Indian Affairs lacks the information necessary to effectively apply these strategies. For example, consolidated written guidance for recruitment tools could help Indian Affairs leverage hiring authorities, recruitment incentives, and workforce flexibilities to increase its applicant pool and fill vacancies. In addition, Indian Affairs has acquired a new staffing dashboard to improve capacity for hiring, but the agency does not have a centralized way to track vacancy data across components, which could support more effective agency-wide succession planning.

Finally, Indian Affairs’ budget uncertainty and other constraints have affected its ability to plan and manage its workforce. By developing a proposal that identifies opportunities to build capacity and the resources necessary to pursue them, Indian Affairs could help Interior determine how the agency could pursue these opportunities with existing resources and authorities. Furthermore, by also developing a proposal that identifies legislative opportunities to build capacity and the resources necessary to pursue them, and sharing it with Congress for consideration, Indian Affairs could help communicate the sustained resources it needs to effectively administer funds to Tribes and help the federal government better fulfill its unique obligations to Tribes.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider, when appropriating funds for Indian Affairs’ administrative costs outside of baseline appropriations, the lessons learned from Indian Affairs on the agency’s prior use of IRA funds and additional use of baseline appropriations for IRA administrative expenses, to help determine the amount needed for program implementation. (Matter for Consideration 1)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following six recommendations to Indian Affairs:

The Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs should, by March 2027, collect lessons learned regarding the use and sufficiency of funds for administrative costs associated with legislation that provides funds for Tribes outside of baseline appropriations and share these lessons with Interior and Congress. (Recommendation 1)

The Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs should track vacancy data across Indian Affairs in a systematic and centralized manner. (Recommendation 2)

The Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs should identify skills, knowledge, and competency gaps in mission-critical occupations across Indian Affairs. (Recommendation 3)

The Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs should develop consolidated written guidance that clarifies what hiring authorities, recruitment incentives, and workforce flexibilities can be leveraged for recruitment and retention purposes. (Recommendation 4)

The Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs should develop a proposal that identifies capacity-building opportunities and the resources necessary to pursue them and share the proposal with Interior for consideration. (Recommendation 5)