NEW CHEMICALS PROGRAM

EPA Needs a Systematic Process to Better Manage and Assess Performance

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106839. For more information, contact J. Alfredo Gómez at (202) 512-3841 or gomezj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106839, a report to congressional requesters

EPA Needs a Systematic Process to Better Manage and Assess Performance

Why GAO Did This Study

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), as amended, directs EPA to make a formal determination on the risk of injury to health or the environment on each new chemical before it can be manufactured. However, GAO reported in February 2023 (GAO-23-105728) that EPA typically made its determination within the 90-day TSCA review period less than 10 percent of the time.

GAO was asked to review EPA’s implementation of its TSCA New Chemicals Program. This report (1) summarizes the perspectives of selected manufacturers on EPA's review process and (2) evaluates the extent to which EPA follows key practices for managing and assessing the program. GAO identified a random, nongeneralizable sample of notices submitted to EPA from October 2021 to April 2024 and interviewed 19 manufacturers that submitted these notices. GAO also compared EPA’s management and assessment activities to key practices it developed based on federal laws, federal guidance, and prior GAO work.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations, including that EPA’s NCD address, as it finalizes its strategic plan, relevant key management and assessment practices; and implement a systematic performance management process that aligns with the key practices. EPA agreed with both recommendations.

What GAO Found

Representatives from 19 manufacturers GAO interviewed identified a range of challenges, strengths, and potential improvements for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) new chemicals review process. For example, most (16 of 19) representatives told GAO they experienced review delays and described effects of these delays on their businesses. Effects manufacturers cited included harming customer relations, creating a competitive advantage for existing chemical alternatives at the expense of new chemicals, and hindering market participation.

Representatives also identified strengths in how EPA implements the program and potential process improvements. For example, almost all (18 of 19) representatives found EPA’s public information sources somewhat or very helpful. Representatives suggested that EPA improve the new chemicals review process by clarifying review requirements, providing realistic time frames for completing reviews, and improving communication, among other improvements.

EPA’s New Chemicals Division (NCD) has taken some important initial planning steps, but NCD does not follow most key practices for managing and assessing the results of its New Chemicals Program.

For example, in August 2024, NCD drafted a strategic plan that identifies five strategic goals and how to achieve them. However, NCD did not follow some relevant key practices in developing the plan, including involving external stakeholders and identifying resources needed to achieve each draft goal. Moreover, NCD officials told GAO that they had not developed a systematic process to ensure that it consistently follows all key practices. Addressing relevant key practices—including involving stakeholders and identifying resources—as NCD finalizes its strategic plan could position the division to better manage and assess the program. Further, implementing a systematic performance process could better position NCD to ensure that it achieves program goals, such as improving the timeliness of reviews.

Abbreviations

|

CBI |

confidential business information |

|

CDX |

Central Data Exchange |

|

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

GPRA |

Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 |

|

LVE |

low volume exemption |

|

NCD |

New Chemicals Division |

|

OPPT |

Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics |

|

PMN |

pre-manufacture notice |

|

TSCA |

Toxic Substances Control Act |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2025

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chairman

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), as amended, authorizes the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to assess and regulate risks from chemical substances already in commerce (existing chemicals) and chemical substances yet to enter commerce (new chemicals).[1] The 2016 Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act, which amended TSCA, substantially expanded EPA’s responsibility to regulate new chemicals, among other amendments.[2] For example, the law began requiring EPA to make a formal determination on the risk of injury to health or the environment on each new chemical before it can be manufactured.[3] According to EPA officials, this requirement significantly increased its review responsibilities.

As of November 2024, EPA reports that it has received 2,623 new chemical notices—which initiate EPA’s risk review—since TSCA was amended in 2016, including 192 in fiscal year 2024.[4] In addition, EPA reports that it has received 2,573 requests for exemption from certain notice requirements (e.g., low volume exemption [LVE] requests) during the same period, including 242 in fiscal year 2024. However, some external stakeholders have expressed concerns about, for example, the efficiency and transparency of EPA’s process for reviewing new chemicals.[5] Moreover, since 2009, we have included EPA’s processes for assessing and controlling toxic chemicals on our High-Risk List as a government program in need of broad-based transformation. In our 2023 update of our High-Risk List, we reported that, although EPA has taken some steps toward completing new chemical reviews on time, it has missed most statutory deadlines.[6] Specifically, in February 2023, we reported that, among those pre-manufacture reviews that EPA completed from 2017 through 2022, the agency typically made its determination within the initial 90-day review period less than 10 percent of the time.[7]

You asked us to review issues related to EPA’s implementation of its TSCA New Chemicals Program. This report (1) summarizes the perspectives of selected manufacturers on EPA’s implementation of its review process for new chemicals and (2) evaluates the extent to which EPA follows key practices for managing and assessing the results of the program.

To address our first objective, we interviewed a nongeneralizable group of 19 manufacturers about their perspectives on EPA’s implementation of its new chemicals review process. To select the manufacturers, we first analyzed EPA’s New Chemicals Review and Chemical Information System data to identify notices that manufacturers submitted from October 1, 2021, through April 20, 2024 (519 total notices). We selected these dates to reflect EPA’s current review process and align with its fiscal year performance assessment schedule.[8] We then randomly selected a nongeneralizable sample of notices reflecting the distribution of all notices across our selection criteria to serve as illustrative examples. These criteria included

· review duration (90 days or less, more than 90 days, and still under review);

· review type (pre-manufacture notices [PMN], significant new use notices, and microbial commercial activity notices);[9]

· EPA determination for completed reviews (e.g., not likely to present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment);

· participation in EPA improvement efforts (e.g., mixed metal oxides reviews);[10] and

· manufacturer size (small business concern or person other than a small business concern).

To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed EPA documentation (e.g., entity relationship diagrams) related to these system data and discussed the data sources with knowledgeable EPA officials. Based on this information, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for selecting our sample.

After we selected our sample, we conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives of 19 manufacturers that submitted the associated notices and completed a systematic content analysis of our interview records.[11] We used a semi-structured interview approach because it allowed us to elicit rich responses about the range of manufacturers’ experiences. In addition, this approach allowed for a more robust methodology. By using consistently worded questions about manufacturers’ experiences, we were able to quantify and aggregate responses, as well as allow unscripted clarification and in-depth discussion.

Our content analysis approach involved five general steps: identify data sources, develop categories, code data, assess reliability, and analyze results. Identified data sources included records of the semi-structured interviews we conducted with each manufacturer. Since our questions were exploratory, we used an inductive approach to develop preliminary coding categories and subsequently tested them. Once we developed these categories, two analysts independently coded each record, then met to assess intercoder reliability and reconcile any coding differences. Although the results of our analysis are not generalizable, they reflect a range of manufacturers’ perspectives on EPA’s new chemicals review process. Our review did not include independently corroborating all statements shared by manufacturer representatives, such as how EPA’s implementation of the new chemicals review process financially affected their companies.

To evaluate the extent to which EPA follows key management and assessment practices, we reviewed GAO’s guide to evidence-based policymaking, which identifies 13 key practices for managing and assessing the results of federal programs, such as EPA’s New Chemicals Program.[12] To understand EPA’s current management and assessment activities, we collected and analyzed agency performance planning and monitoring documents. We also interviewed officials from EPA’s Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics’ (OPPT) New Chemicals Division (NCD), which is responsible for implementing the New Chemicals Program. Two analysts then independently compared those management activities to the 13 key practices and associated key actions to determine whether EPA generally follows, partially follows, or does not follow each practice.[13] The analysts then discussed how to reconcile, as appropriate, any differences in their determinations.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

New Chemicals Review Process

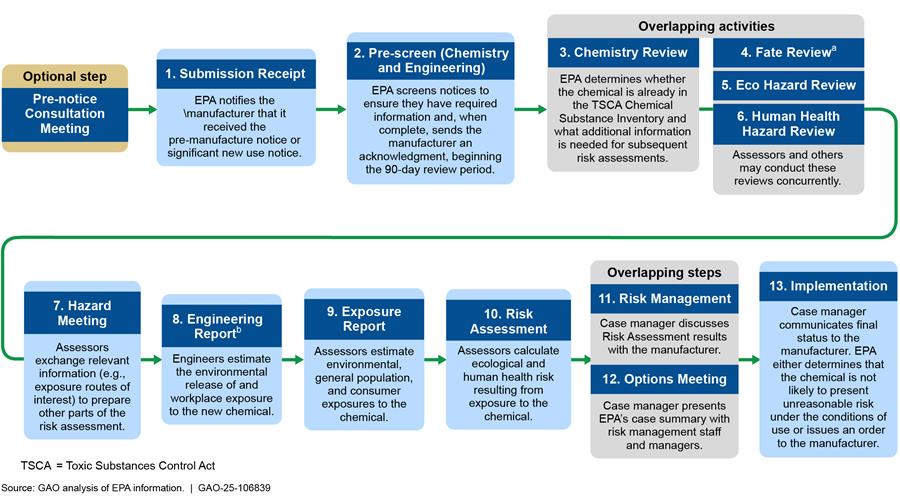

EPA’s process to review new chemical substances involves 13 steps and includes an optional Pre-notice Consultation Meeting on topics related to the preparation and completeness of the manufacturer’s notice as summarized in figure 1.[14]

Note: EPA’s New Chemicals Division eliminated a separate “Scoping Meeting” to streamline where case discussions occur in the workflow. Division officials noted that those same discussions now occur as part of the Hazard Meeting. This review process is not applicable to microbial commercial activity notices.

aDuring the Fate Review step, EPA evaluates how chemicals released into the environment move, transform, or accumulate in various media.

bEngineering assessment begins after Chemistry Review and may overlap with Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review.

We provide additional information in appendix I about key review activities that occur at each step, along with potential EPA interaction with manufacturers during the review. For example, the case manager—who coordinates the review and serves as the official point of contact—may communicate with the manufacturer for clarification about information they provided in their notice or other issues of concern.

EPA posts a range of information sources (e.g., policies and guidance) about the new chemicals review process on its website and conducts webinars to help manufacturers prepare their notices.[15] For example, EPA recommends that submitters review its June 2018 Points to Consider When Preparing TSCA New Chemical Notifications document, which is intended to help submitters prepare notices and meet TSCA requirements, as well as to facilitate EPA’s review of notifications.[16] Manufacturers submit information to EPA using the agency’s Central Data Exchange (CDX) information system.

At the Pre-screen step, EPA reviews all notices to ensure they are complete, such as ensuring that they include information on environmental releases and worker exposure. Once EPA determines that the notice is complete, it notifies the manufacturer, and the 90-day TSCA applicable review period begins.[17] According to EPA, it uses a standardized approach that draws on knowledge and experience across disciplinary and organizational lines to identify and evaluate concerns regarding health and environmental effects, exposure, and release.[18] It has also developed assessment methods to help evaluate what happens to chemicals when laboratory studies or monitoring data are not available or need to be supplemented. These methods assess a particular aspect of a chemical’s possible impact on health or the environment. For example, EPA may use predictive models to assess worker exposure during the manufacturing, processing, and use of a chemical.

Key Practices for Managing and Assessing the Results of Federal Programs

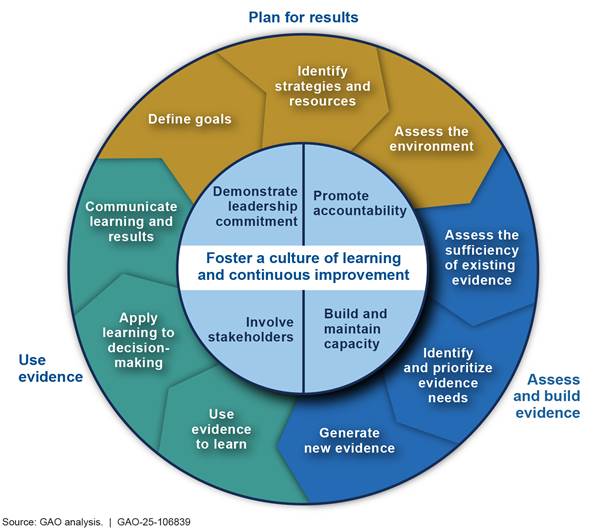

Based on our prior work as well as federal laws and guidance, in July 2023, we developed 13 key practices that can help federal agency leaders develop and use evidence to effectively manage and assess the performance of federal programs.[19]

We organize the practices into the following four topic areas, based on their primary focus, as shown in figure 2:

· Foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement

· Plan for results

· Assess and build evidence

· Use evidence

While we present the topic areas and practices in a certain order, they are interconnected. As the figure illustrates, the latter three are part of an iterative cycle. Within that cycle, the practices in the “plan for results” topic area are foundational. For example, until an agency identifies goals for a program, it is not positioned to identify or prioritize its evidence needs or to use evidence in monitoring progress.

The four practices in the “foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement” topic area are central to carrying out the nine practices that comprise the iterative cycle covered by the other three topic areas.

One key cultural practice is to involve stakeholders. Stakeholders can include entities both internal and external to the agency, such as manufacturers and organizations that address environmental protection, human health, and occupational safety, as well as other interested parties. We have reported that the involvement of a range of stakeholders is often vital to the success of federal efforts. Stakeholder input can help an organization determine priorities, target resources, and align its goals and strategies with those of others involved in achieving the same or similar outcomes.[20] Such input can also facilitate understanding among all relevant parties of both competing demands that an organization faces and constraints on its resources.

Selected Manufacturers Identified a Range of Challenges, Strengths, and Potential Improvements for EPA’s New Chemicals Review Process

Selected manufacturers shared their perspectives about challenges and strengths related to the review and submission processes, the usability of EPA’s CDX information system, and potential process improvements. For example, most manufacturer representatives told us they experienced review delays and described a range of impacts these delays had on their businesses. Almost all manufacturer representatives reported using EPA’s publicly available information sources to prepare their submissions, but most told us that additional information would be helpful. While some representatives told us that EPA’s CDX information system was easy to learn or use, others described challenges completing or updating their submissions. Finally, representatives cited a range of potential review process improvements such as improving the transparency of review requirements.

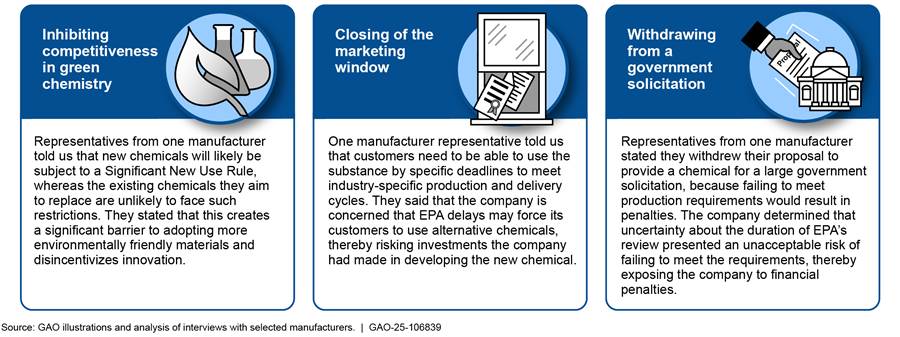

New Chemicals Review Process

Most (16 of 19) manufacturer representatives told us they experienced review delays, which they attributed to inadequate EPA staffing, insufficient EPA reviewer expertise, and other factors. Representatives described a range of effects EPA’s new chemical review process had on their businesses, such as harming client or customer relations (11), affecting the company financially (10), creating a competitive advantage for existing chemical alternatives at the expense of new chemicals (six), hindering market participation (four), or harming innovation (four). Figure 3 shows examples of how representatives from three manufacturers said EPA’s review process affected their companies.

Figure 3: Reported Examples of How the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) New Chemicals Review Process Affected Selected Manufacturers

Note: Examples are based on interviews we conducted with 19 manufacturers that submitted new chemical notices to EPA from October 1, 2021, through April 20, 2024. EPA uses Significant New Use Rules in the new chemicals program in two ways. First, EPA generally promulgates a Significant New Use Rule that requires notice to EPA by any person who wishes to manufacture or process a new chemical in a way other than described in the terms and conditions contained in the consent order that binds the original submitter and requires measures to limit exposures or mitigate the potential unreasonable risk for that substance. Second, if EPA determined that the new chemical substance is “not likely to present an unreasonable risk” under its conditions of use, EPA may still issue a Significant New Use Rule that identifies other circumstances that may present risk concerns should they occur in the future.

Representatives also shared varying perspectives about the transparency of EPA’s review process. Whereas representatives from nine manufacturers expressed frustration about not knowing where their submission stood in the review process, four told us they appreciated receiving updates from EPA staff—particularly case managers—about the status of their submissions. Representatives from four of 19 manufacturers said that EPA should provide additional information about review timelines, such as realistic time estimates for completing reviews.

Additionally, nine manufacturer representatives shared concerns about the transparency of EPA’s review process requirements. For example, one manufacturer said that EPA did not accept the chemical naming in its submission, though the manufacturer said they submitted the chemical naming in accordance with relevant EPA guidance. Another manufacturer told us that EPA would not disclose the chemical identity of analogues it used for risk assessments, which impeded the company’s ability to hold EPA accountable or determine the appropriateness of the agency’s risk assessment approach.

Submission Process

Almost all (18 of 19) manufacturer representatives we interviewed reported using publicly available EPA information sources to prepare their submissions and generally found those sources to be somewhat or very helpful. For example, representatives from one manufacturer told us they consulted EPA sources about how the agency handles confidential business information (CBI).[21] Representatives from 11 manufacturers also told us they attended EPA webinars, such as the Engineering Initiative Webinar Series, which is intended to increase the efficiency and transparency of EPA’s new chemical determinations.

Although pre-notice consultation is an opportunity for submitters to receive EPA assistance in preparing pre-manufacture and other notices, 14 of 19 manufacturer representatives we interviewed told us they did not request such optional meetings with EPA. Eight of 14 of these representatives told us Pre-notice Consultation Meetings were unnecessary because their companies already had experience with the new chemicals review process or had hired consultants who did.

However, representatives identified additional information that EPA could provide to help manufacturers better prepare future submissions. Twelve of 19 representatives told us that EPA should provide additional information that clarifies its new chemicals review process or submission information requirements.

· For example, representatives from one manufacturer told us that the submission process for microbial commercial activity notices is “a mysterious black box.” They said that the company was unsure what information it needed to submit due to decades-old EPA guidance. Specifically, they said that EPA’s June 1997 Points to Consider in the Preparation of TSCA Biotechnology Submissions for Microorganisms guidance is out of date. They also said it lacked sufficient information about, for example, what to include in the microbial commercial activity notice submission, such as characteristics of the microorganism and how to submit a text file of the genetic manipulations done to it. Representatives noted that they appreciated EPA scheduling consultations to prepare the notice, but more comprehensive guidance about what to include in the submission would benefit both the agency and submitters.[22]

· Representatives from another manufacturer stated that EPA should specify how it utilizes chemical distribution, processing, and use information. Representatives told us that making this information available to manufacturers before they submit notices (e.g., by adding it to the June 2018 Points to Consider When Preparing TSCA New Chemical Notifications document) could help them better substantiate their submissions.

Usability of EPA’s CDX Information System

Five of 19 manufacturer representatives we interviewed told us that EPA’s CDX information system was easy to learn or use. However, others described challenges completing or updating their submissions using CDX, such as the following:

· System errors: Eight representatives told us they experienced errors when using CDX. For example, one representative described having to manually edit each submission file that contained non-English characters, since CDX would redact those characters during transmission. The representative told us they spent 6 weeks addressing CDX technical errors before EPA considered their submission complete, starting the 90-day TSCA applicable review period.

· Challenges substantiating CBI claims: Six representatives discussed challenges using CDX to substantiate their CBI claims. Representatives from one manufacturer told us that EPA previously allowed manufacturers to use a standard Word document template to substantiate CBI claims in CDX, but EPA now requires the submitter to answer six CBI questions for every individual claim. They estimated that manual substantiation in CDX took three times longer than it had using a template.

· Navigation and learning challenges: Five representatives stated that CDX was not intuitive or that it took substantial time to learn how to use the system. One manufacturer told us that they would have had difficulty navigating CDX without the assistance of an external consultant, because the system itself did not have instructions for using it.

Nine of 19 representatives told us they appreciated the support they received from the CDX help desk, which helped them manage system errors. For example, representatives from one manufacturer told us the help desk provided them with methods to work around technical errors, such as saving submission forms in a certain way to ensure that authorized users appeared as signatories on the forms.

Potential New Chemicals Review Process Improvements

Among the 19 manufacturers we interviewed, the most-cited potential improvements to the new chemicals review process were primarily related to reducing review times or improving the transparency of process requirements, as summarized below:[23]

· Clarify new chemicals review process requirements (12): For example, one manufacturer representative suggested that EPA establish updated, transparent protocols that clearly specify minimum likely testing requirements or guidelines that could be publicly accessed by manufacturers prior to submitting the PMN.[24] Another representative said that EPA guidance does not sufficiently specify what information manufacturers should provide with their submission. They contrasted EPA’s practice with that of Canada, which they said provides a more complete list of requirements to submitters.[25]

· Increase number of reviewers (9): Some manufacturers said that additional reviewers may reduce review delays. For example, representatives from one manufacturer told us that staff attrition and retirement, as well as a shortage of human health assessors, contribute to review delays. In February 2023, we reported that EPA’s significant workforce planning gaps—including difficulty retaining and recruiting staff—have contributed to missed deadlines for new chemical reviews.[26]

· Clarify the status of incomplete reviews or time frames for completing them (9): One manufacturer suggested that EPA provide realistic time frames for completing reviews, particularly when the agency does not meet the applicable 90-day TSCA review period. Representatives from another manufacturer told us that reporting more granular information on EPA’s statistics web page, including where specific PMNs stand in the review process, would help the company plan.[27]

· Reduce review times (8): Representatives from one manufacturer noted that EPA will likely continue to operate in a resource-constrained environment and must identify innovative ways to complete reviews in a timely manner. Another manufacturer suggested that EPA reduce review times for certain chemicals by creating a “triage program,” where the agency groups chemicals by risk profiles and expedites its review of lower-risk chemicals.

· Improve communication throughout the review process (8): One manufacturer told us that improved communication may clarify and help address the underlying causes of delays more quickly, such as when EPA needs more information from manufacturers. The manufacturer noted that more timely communication can help “dislodge” cases that are stuck in review.

In June 2024, EPA announced new initiatives intended to increase the transparency of new chemical reviews, among other things. For example, EPA began implementing an internal engineering checklist to systematically review new chemical submissions and identify potential data gaps at the beginning of the review process. Additionally, EPA launched the NCD Reference Library that includes guidance documents, compliance advisories, templates, manuals, and other materials for stakeholders.[28] We discuss NCD’s involvement of stakeholders in planning and assessing the program later in this report.

EPA Follows Some but Not All Key Management and Assessment Practices

EPA’s NCD Generally or Partially Follows Some Key Practices, Including Defining Draft Program Goals

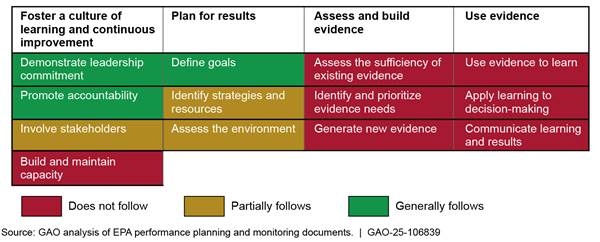

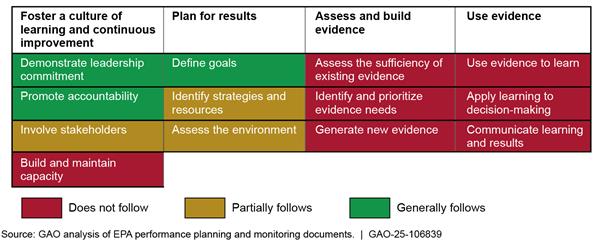

EPA’s NCD generally or partially follows six of the 13 key practices for managing and assessing its New Chemicals Program, all of which fall within the first two topic areas (see fig. 4).[29] Appendix II includes additional information about the extent to which EPA follows these practices.

Figure 4: Extent to Which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Follows Key Management and Assessment Practices for Its New Chemicals Program

· Foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement: NCD demonstrates leadership commitment by involving senior leaders in performance management and evidence-building activities and those leaders meet regularly to coordinate those activities. Additionally, NCD promotes accountability by assigning responsibility for these activities in performance plans for senior leaders and supervisory scientists. Moreover, division officials told us they consulted with some (i.e., internal) stakeholders such as senior leaders, case managers, and other employees in its strategic planning efforts.

· Plan for results: In August 2024, NCD drafted a strategic plan that defines five goals related to the program (see table 1).[30] The draft plan also identifies metrics and strategies for achieving each strategic goal, but does not consistently identify needed resources.[31] In their written responses to us, NCD officials indicated they had addressed the “assess the environment” practice by identifying factors that could affect goal achievement, but the plan does not consistently define strategies to mitigate those factors. For example, officials stated that EPA’s “unstable” and “antiquated” information technology systems, including CDX, could affect NCD’s ability to improve the timeliness of new chemical risk assessments. Officials also stated that high management and staff workload could affect the division’s ability to achieve its goal to “support healthy organizational culture.” Although NCD is still finalizing how the division will ultimately assess progress in achieving this goal, senior managers told us they currently consider, for example, Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey scores to monitor performance in this area.[32]

Table 1: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) New Chemicals Division Draft Strategic Goals, Fiscal Years (FY) 2024–2025

|

Deliver scientifically sound risk-based assessments for new chemical substances with improved timeliness |

|

Ensure policies and risk management actions are protective and aligned with statutory goals and requirements and stakeholders are aware of requirements |

|

Manage, update, and publish the Toxic Substances Control Act inventory |

|

Reinforce commitment to transparency by providing the public with meaningful information on a consistent and timely basis |

|

Strive for program excellence; support healthy organizational culture |

Source: EPA New Chemicals Division’s August 2024 draft FY 2024–-2025 strategic plan. | GAO‑25‑106839

EPA’s NCD Does Not Follow Most Key Practices and Has Not Developed a Systematic Performance Management Process

While NCD has taken some important initial steps described above, we determined that the division does not follow seven of 13 key management and assessment practices. For example, NCD has not formally assessed the sufficiency of its existing evidence-building capacity or identified actions to maintain or enhance that capacity. Relatedly, the division does not follow any practices for effectively assessing, building, or using evidence because it has not completed foundational planning actions. Such foundational actions include involving stakeholders and identifying resources needed to achieve goals.[33] Finalizing its strategic plan in a manner that is consistent with such practices could better position NCD to identify and prioritize the evidence it needs and use that evidence to monitor progress toward achieving the plan’s strategic goals, such as to “deliver scientifically sound risk-based assessments for new chemical substances with improved timeliness.”

Additionally, NCD officials told us that they had not developed a systematic process that ensures the division consistently follows all key practices in implementing the program. Doing so could help the division manage the New Chemicals Program’s performance more effectively by, for example, building stakeholder involvement into its strategic management process, as appropriate. We have previously reported that involving of a range of stakeholders early and often is vital to the success of federal efforts.[34] Such stakeholders could include manufacturers and organizations that address environmental protection, human health, and occupational safety, as well as other interested parties. NCD officials routinely engage with external stakeholders through topic-specific workshops, conferences, and other means. However, they did not involve these stakeholders in developing the draft strategic plan. One option is to release an exposure draft to solicit stakeholder comment before finalizing the plan.[35] By involving stakeholders as it finalizes and implements the plan, NCD could better capture a range of perspectives to inform its efforts.

Moreover, involving a range of stakeholders in NCD’s performance management process could also help the division better understand how to achieve its stated strategic goals. As discussed earlier in this report, representatives from most manufacturers we interviewed told us that EPA should provide additional information that clarifies its new chemicals review process or submission information requirements. Representatives also raised concerns about EPA guidance being out of date or inconsistent with feedback the company received on its submission. Involving external stakeholders could help NCD understand stakeholders’ information needs and priorities, as the division determines how to achieve its draft goals of “ensuring stakeholders are aware of requirements” and “providing the public with meaningful information on a consistent and timely basis.”

Conclusions

Under TSCA, EPA is required to make a formal determination on the risk of injury to health or the environment on each new chemical before it can be manufactured and, if appropriate, take subsequent required actions to mitigate the risk. However, EPA continues to face challenges carrying out its responsibility to make such determinations within the applicable 90-day TSCA review period. In this context, manufacturers’ representatives whom we interviewed discussed a range of strengths, challenges, and potential improvements to the new chemicals review process.

NCD has taken important initial steps to better manage and assess its New Chemicals Program, such as developing a draft strategic plan that identifies five strategic goals. However, NCD does not follow most key management and assessment practices. For example, the division does not follow any key practices related to assessing, building, or using evidence because it has not completed foundational planning actions. As NCD finalizes the strategic plan, addressing relevant key practices—including involving a range of internal and external stakeholders and identifying resources—will better position NCD to identify and prioritize its evidence needs. This will also enable NCD to use that evidence to monitor progress toward achieving the plan’s strategic goals, such as to “deliver scientifically sound risk-based assessments for new chemical substances with improved timeliness.”

Additionally, NCD has not developed a systematic process that ensures the division consistently follows all key practices, which could help the division manage the program’s performance more effectively. For example, involving a range of external stakeholders early and often in such a process could help NCD understand stakeholders’ information needs and priorities. This understanding is important, as the division finalizes its strategic plan and determines how to achieve its draft goals of “ensuring stakeholders are aware of requirements” and “providing the public with meaningful information on a consistent and timely basis.”

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to EPA:

The Administrator of EPA should ensure that NCD, as it finalizes its strategic plan, addresses relevant key practices for managing and assessing the New Chemicals Program, including involving stakeholders and identifying resources. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of EPA should ensure NCD implements a systematic process that aligns the division’s performance management approach with key management and assessment practices. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to EPA for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix III, EPA agreed with both of our recommendations. Regarding recommendation 1, EPA indicated that NCD aims to finalize the division’s draft strategic plan in Spring 2025. EPA stated that the agency is committed to improving the efficiency and transparency of the New Chemicals Program but noted that, without significantly increased resources for the program, its progress toward those ends may be limited. Given this concern, EPA said that NCD is considering different options for engagement with key stakeholders without detracting from completing casework. Regarding recommendation 2, EPA said that, resources permitting, NCD intends to develop a systematic process that aligns the division’s performance management approach with key management and assessment practices, such as building and maintaining capacity. EPA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. After we received EPA’s written comments, the agency provided supplemental information to highlight recent progress in completing new chemical reviews. Specifically, according to EPA, NCD (a) completed 32 risk assessments in November 2024 and 56 such assessments in December 2024 and (b) reduced the number of cases from fiscal year 2023 that were still under review at the beginning of fiscal year 2024.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Administrator of EPA. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or gomezj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

J. Alfredo Gómez

Director

Natural Resources and Environment

|

Step |

What key review activities occur at this step? |

Does this step overlap with other steps? |

How do EPA and manufacturers interact, if at all, during this step? |

|

1. Submission Receipt |

The Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT) confirms receipt of the pre-manufacture notice (PMN), significant new use notice, or microbial commercial activity notice.a |

No. |

Manufacturers receive an auto-generated email from the Central Data Exchange (CDX) information system when the PMN, significant new use notice, or microbial commercial activity notice submission is successfully received. The manufacturer can download a copy of the record of the submission. |

|

2. Pre-screen (Chemistry and Engineering) |

OPPT screens all notices within 1–3 days of receipt to ensure the notices have the required information, such as unambiguous chemical identity and complete site identification information, manufacturing process descriptions, and information on environmental releases and worker exposure for each site.b |

No. |

If OPPT finds that a submitted notice does not have all required information, the office notifies the manufacturer and provides next steps for resubmitting the notice. Additionally, when a manufacturer successfully completes the Pre-screen step, OPPT sends an Acknowledgment Letter to the manufacturer. |

|

3. Chemistry Review |

The case manager and review chemists conduct inventory checks to determine if the chemical is already in the TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory, generate initial chemistry reports, and conduct a chemistry meeting to discuss what additional information is needed for subsequent risk assessments.c |

Some Chemistry Review, Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review activities may overlap. |

Review chemists may contact manufacturers with questions related to the notice. |

|

4. Fate Review |

Fate assessors (consisting of biologists, physical scientists, and environmental engineers) evaluate environmental fate and transport of the new chemical and assign “fate ratings” that score the chemical’s persistence, bioaccumulation, migration to groundwater, etc.d |

Some Chemistry Review, Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review activities may overlap. |

If questions related to the notice arise, assessors may contact manufacturers via the case manager. |

|

5. Eco Hazard Review |

Ecological risk assessors (consisting of biologists and toxicologists) evaluate the potential environmental hazard to aquatic organisms. For example, assessors will consider the fate properties of a chemical (e.g., how fast the chemical degrades in a stream) when evaluating the potential harm to fish populations. |

Some Chemistry Review, Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review activities may overlap. |

If questions arise related to the notice, assessors may contact manufacturers via the case manager. |

|

6. Human Health Hazard Review |

Health assessors (consisting of biologists and toxicologists) evaluate the health hazards to people, including consumers, workers, and the general population. For example, EPA considers if a chemical is a possible human carcinogen. |

Some Chemistry Review, Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review activities may overlap. |

If questions arise related to the notice, assessors may contact manufacturers via the case manager. |

|

7. Hazard Meeting |

Fate assessors, ecological risk assessors, human health assessors, and the case manager exchange information relevant to the scope of the chemical’s assessment (e.g., exposure routes of interest) to prepare for the next step of Risk Assessment.e Chemical-specific information will be shared across disciplines related to topics such as water solubility (chemistry), degradation rates (fate), fish toxicity (eco hazard), and general population hazards (human health hazard). |

Some Chemistry Review, Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review activities may overlap with the Hazard Meeting. |

The case manager may speak with the manufacturer about hazards identified. For example, if the assessors estimate high eco hazard, the case manager may inform the manufacturer about the hazard assessment and discuss whether the manufacturer can limit release of the substance to water. |

|

8. Engineering Report |

Engineers (typically chemical engineers) estimate the environmental release of and workplace exposure to the new chemical. For example, EPA may use manufacturer estimates, models, generic scenarios, or emission scenario documents to estimate environmental release and workplace exposure. |

Engineering assessment begins after Chemistry Review and may overlap with Fate Review, Eco Hazard Review, and Human Health Hazard Review. |

Chemical engineers contact manufacturers if there are questions. |

|

9. Exposure Report |

Exposure assessors (consisting of biologists, physical scientists, toxicologists, chemical engineers, and environmental engineers) estimate environmental, general population, and consumer exposures to the chemical.f |

Compiling data for the Risk Assessment may begin before completion of the Exposure Report but estimates of the chemical’s health and ecological risks occur only after the Exposure Report is complete. |

Not applicable. |

|

10. Risk Assessment |

Ecological assessors and human health assessors calculate ecological and human health risk resulting from exposure to the chemical. For example, human health assessors calculate if risks for developmental effects will exceed the margin of safety due to the estimated releases to drinking water. Ecological assessors will calculate whether the estimated chemical concentration in a stream exceeds the concentration of concern in the environment. |

Compiling data for the Risk Assessment may begin before completion of the Exposure Report, but estimates of the chemical’s health and ecological risks occur only after the Exposure Report is complete. |

Assessors may contact manufacturers via the case manager if questions arise related to the notice. |

|

11. Risk Management |

The case manager reviews the Risk Assessment and discusses results with the manufacturer. The case manager develops risk mitigation options, as necessary. |

The Risk Management and Options Meeting steps may overlap. |

The case manager discusses Risk Assessment results and risk mitigation options with the manufacturer, as needed. |

|

12. Options Meeting |

The case manager presents EPA’s summary of the case to risk management staff and managers. The case summary includes discussion of conditions of use, outcomes of the Risk Assessment step, proposed determination, and proposed risk mitigation terms.g |

The Risk Management and Options Meeting steps may overlap. |

The case manager discusses the outcome(s) of the Options Meeting, including recommended consent order terms, as needed, with the manufacturer. |

|

13. Implementation |

If EPA determines the chemical is not likely to present unreasonable risk under the conditions of use, the agency will notify the manufacturer, which may commence manufacture of the chemical or manufacture or processing for a significant new use. If EPA makes any of the four other determinations, it must issue an order to the manufacturer, typically a consent order.g A consent order may include requirements such as testing; use of worker personal protective equipment; hazard labeling; restrictions on manufacturing, processing, distribution, use, or disposal; recordkeeping requirements; and water release restrictions. |

No. |

The case manager communicates the status of final document reviews with manufacturers and sends final, signed documents to manufacturers. |

Source: GAO analysis of EPA information. | GAO‑25‑106839

aCertain categories of new chemical substances are exempt from PMN requirements under TSCA section 5 (e.g., low volume exemption [LVE], low releases and low exposures exemption, research and development exemption, test marketing exemption) and have a different notification, review period, and requirements than PMNs. See 40 C.F.R. 723.50, 720.36, 720.38. For example, LVEs follow the same general risk assessment steps within a shorter time frame and have a different risk management process where they are either granted or denied. Microbial commercial activity notices do not go through each specific step but follow the same general process as PMNs.

bAfter the Pre-screen step, EPA must notify the submitter within 30 days of receipt that the submission is incomplete and that the notice review period will not begin until EPA receives a complete notice. 40 C.F.R. 720.65(c)(2).

cU.S. Environmental Protection Agency, TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 22, 2014), accessed December 17, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/tsca-inventory.

d“Environmental fate” refers to what happens to a chemical or a microorganism once it is released into the environment, including any changes due to physical, chemical, and biological processes. “Transport” refers to how chemicals move in the environment.

eEPA’s “Risk Assessment” includes a “human health risk assessment” and an “ecological risk assessment.” A “human health risk assessment” is the process to determine whether a potential hazard exists for a chemical (or its degradants) and to estimate the potential for, and magnitude of, risk to an exposed individual or population. An “ecological risk assessment” evaluates the potential adverse effects of each new chemical substance and compares the effects with predicted environmental exposures to determine risk.

fAn exposure assessment is the process of identifying the likely duration, intensity, frequency, and number of exposures to a chemical, including the nature and types of individuals or populations that are exposed to the chemical.

g“Conditions of use” refers to the intended, known, or reasonably foreseen circumstances, of the manufacture, processing, distribution in commerce, and use and disposal of chemicals. 15 U.S.C. 2602(4). EPA may make one of five determinations. EPA’s determinations include (1) the chemical or significant new use presents an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment; (2) available information is insufficient to allow the agency to make a reasoned evaluation of the health and environmental effects associated with the chemical or significant new use; (3) in the absence of sufficient information, the chemical or significant new use may present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment; (4) the chemical is or will be produced in substantial quantities and may either enter the environment in substantial quantities or result in significant or substantial human exposure to the chemical; and (5) the chemical or significant new use is not likely to present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment. 15 U.S.C. 2604(a)(3).

Appendix II: Extent to Which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Follows Key Management and Assessment Practices for Its New Chemicals Program

Table 3: Extent to Which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Follows Key Management and Assessment Practices for Its New Chemicals Program

|

Topic area |

Key management and assessment practice |

Description of EPA activities |

GAO determination |

|

Plan for results |

Define goals |

EPA’s New Chemicals Division (NCD) draft strategic plan defines five goals that generally align with EPA’s agency-wide strategic plan. The draft plan also includes metrics for each goal. |

Generally follows |

|

|

Identify strategies and resources |

NCD’s draft strategic plan identifies strategies for each goal and includes interdependencies where coordination with other organizations, programs, and activities may be needed; however, the plan does not identify the resources needed to achieve each goal. |

Partially follows |

|

|

Assess the environment |

NCD’s draft strategic plan identifies internal and external factors that could affect goal achievement but does not consistently define strategies to address or mitigate those factors. |

Partially follows |

|

Assess and build evidence |

Assess the sufficiency of existing evidence |

—a |

Does not follow |

|

|

Identify and prioritize evidence needs |

—a |

Does not follow |

|

|

Generate new evidence |

—a |

Does not follow |

|

Use evidence |

Use evidence to learn |

—a |

Does not follow |

|

|

Apply learning to decision-making |

—a |

Does not follow |

|

|

Communicate learning and results |

—a |

Does not follow |

|

Foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement |

Demonstrate leadership commitment |

NCD involves senior leaders in performance management and evidence-building activities, and those leaders meet regularly to coordinate those activities. |

Generally follows |

|

Promote accountability |

NCD assigns responsibility for performance management and evidence-building activities in performance plans for senior leaders and supervisory scientists. |

Generally follows |

|

|

|

Involve stakeholders |

NCD involved internal stakeholders in developing its draft strategic plan. Although NCD routinely engages with external stakeholders through topic-specific workshops, conferences, and other means, the division did not involve these stakeholders in developing the draft strategic plan specifically. |

Partially follows |

|

|

Build and maintain capacity |

NCD has not formally assessed the sufficiency of its existing evidence-building capacity or identified actions to maintain or enhance that capacity. NCD senior managers told us the division lacks sufficient expertise and resources to do so.b |

Does not follow |

— = No activities

Source: GAO analysis of EPA performance planning and monitoring documents. | GAO‑25‑106839

aWhile we present the topic areas and practices in a certain order, they are interconnected, and two of them—”assess and build evidence” and “use evidence”—are part of an iterative cycle that builds on key actions established in the foundational “plan for results” topic area. Because EPA has not finalized the division’s strategic plan or completed these key actions, we determined that the agency is not positioned to, and thus does not, follow the six practices included in the “assess and build evidence” and “use evidence” topic areas.

bAgency performance improvement officers advise and assist agency leaders to ensure that the mission and goals of the agency are achieved. These officers are responsible for leading efforts to set goals; reviewing progress on those goals and identifying course corrections; and promoting a culture of using data and evidence, managing risks, and communicating performance information. This includes advising organizational components, such as NCD, in strategic planning. NCD officials told us that they had not consulted with the performance improvement officer when drafting the division’s strategic plan.

GAO Contact

J. Alfredo Gómez, (202) 512-3841 or gomezj@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff members made key contributions to this report: Diane Raynes (Assistant Director), William Colwell (Analyst in Charge), Mark Braza, Steven Flint, Frank Garro, Cory Gerlach, Michael Hoffman, Erik Kjeldgaard, Barbara Lancaster, Benjamin Licht, Matt McLaughlin, Amanda Miller, Abinash Mohanty, Dan Royer, Robbie Skinner, and Linda Tsang.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Toxic Substances Control Act, Pub. L. No. 94-469, 90 Stat. 2003 (1976) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 2601 et seq.). TSCA defines “chemical substance” as any organic or inorganic substance of a particular molecular identity, including any combination of such substances resulting from a chemical reaction or occurring in nature, and any element or uncombined radical. 15 U.S.C. § 2602(2).

[2]Pub. L. No. 114-182, 130 Stat. 448 (2016).

[3]TSCA provides that a person may only manufacture a new chemical or manufacture or process for a significant new use of an existing chemical if, in addition to submitting a pre-manufacture notice (PMN), EPA makes an affirmative determination on the risk of injury to health or the environment of the new chemical and takes any subsequent required actions to mitigate the risk after such a determination. 15 U.S.C. § 2604(a); 40 C.F.R. pts. 720, 721, 725. The applicable review period for EPA’s determination and any subsequent required actions is 90 days with certain exceptions. See 15 U.S.C. § 2604(i)(3).

[4]For additional information, see U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Statistics for the New Chemicals Program under TSCA (Washington D.C.: Nov. 5, 2024), accessed November 13, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/reviewing-new-chemicals-under-toxic-substances-control-act-tsca/statistics-new-chemicals-program. Counts are as of November 1, 2024, and include valid PMNs, significant new use notices, and microbial commercial activity notices. TSCA requires any person who plans to manufacture or process a new chemical, a significant new use of an existing chemical, or microorganisms for commercial purposes to submit a PMN at least 90 days prior to the manufacture of the chemical. See 15 U.S.C. § 2604(a); 40 C.F.R. pts. 720, 721, 725.

[5]For some of the 53 comments that EPA received on its 2024 amendments to the new chemical procedural regulations to improve the efficiency of its new chemicals review processes, among other things, see U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Updates to New Chemicals Regulations Under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), 89 Fed. Reg. 102773 (Dec. 18, 2024).

[6]GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[7]GAO, EPA Chemical Reviews: Workforce Planning Gaps Contributed to Missed Deadlines, GAO‑23‑105728 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 17, 2023).

[8]Specifically, we analyzed (1) a weekly New Chemicals Review data report that included information on review duration, review type, EPA’s determination for completed reviews, and participation in EPA improvement efforts; and (2) a Chemical Information System data extract that included information on manufacturer size and contact information. For purposes of this report, we use the term “manufacturer” to also include other submitters, such as importers or processors.

[9]Microbial commercial activity refers to the manufacturing, importing, or processing of microorganisms, such as yeast or bacteria, for commercial purposes, such as biofuel. EPA requires that a person who manufactures, imports, or processes new or significant new uses of microorganisms for commercial purposes submit a microbial commercial activity notice to EPA. See 15 U.S.C. § 2604(a); 40 C.F.R. pt. 725 subpt. D.

[10]We previously reported that EPA was exploring ways to streamline the new chemicals review process. See GAO‑23‑105728, 19. For example, in January 2022, EPA announced its biofuels initiative intended to standardize reviews of new chemicals that could be used instead of other transportation fuels with higher emissions. Similarly, in October 2022, it announced a new approach for reviewing mixed metal oxides, including cathode active materials, a key component of electric vehicle batteries.

[11]Our initial sample included 21 notices. In cases of non-response, we selected replacement notices (10) that still allowed the sample to reflect the distribution of all 519 notices across our selection criteria. We completed interviews with representatives of 19 manufacturers.

[12]GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

[13]When we determined that EPA has implemented all key actions associated with the practice, we report that EPA “generally follows” the practice. When we determined that EPA has implemented at least one but not all key actions, we report that the agency “partially follows” the practice. When we determined that EPA has implemented none of the key actions, we report that EPA “does not follow” the practice.

[14]Our review focuses on PMNs, significant new use notices, and microbial commercial activity notices. It does not address exemption notices (e.g., LVEs, low releases and low exposures exemptions, or test marketing exemptions), because such notices have a different review period and regulatory considerations than PMNs.

[15]See, for example, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA’s Review Process for New Chemicals (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 15, 2024), accessed November 14, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/reviewing-new-chemicals-under-toxic-substances-control-act-tsca/epas-review-process-new-chemicals#policies. EPA also reports information on its new chemicals workload, tracks the status of active cases currently under review, and illustrates general statistics for all new chemical submissions. See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Statistics for the New Chemicals Program under TSCA. According to that page, EPA started reporting the number of rework assessments completed monthly in June 2024, beginning with January 2024. “Rework” is EPA’s term for work that supplements completed initial risk assessments, such as evaluation of new information from the submitter and development of new assessment reports or memoranda in response to new information or questions.

[16]U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Points to Consider When Preparing TSCA New Chemical Notifications (Washington D.C.: June 2018), accessed September 11, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-06/documents/points_to_consider_document_2018-06-19_resp_to_omb.pdf.

[17]EPA regulations provide that a person who submits a PMN may voluntarily suspend the running of the 90-day review period for a specified period of time. See 40 C.F.R. § 720.75(b). As we reported in February 2023, according to EPA officials, the agency obtained voluntary suspensions in almost all cases that exceeded the 90-day review period. See GAO‑23‑105728. While EPA’s review period is suspended, the new chemical may not be manufactured until EPA makes a formal determination on the risk of injury to health or the environment on the new chemical. See 15 U.S.C. § 2604(a).

[18]See “EPA’s Review Process for New Chemicals,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accessed November 14, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/reviewing-new-chemicals-under-toxic-substances-control-act-tsca/epas-review-process-new-chemicals#policies.

[19]GAO‑23‑105460. Relevant laws and guidance include the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (GPRA), as amended (Pub. L. No. 103-62, 107 Stat. 285); the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010, as amended (Pub. L. No. 111-352, 124 Stat. 3866 (2011)); the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 (Evidence Act) (Pub. L. No. 115-435, 132 Stat. 5529 (2019)); and the Executive Office of the President Office of Management and Budget’s guidance (e.g., Circular No. A-11).

[21]Under TSCA section 14, manufacturers submitting CBI to EPA under TSCA may assert a claim for protection from public disclosure of that information. 15 U.S.C. § 2613. EPA’s regulations specify the requirements for submitting and supporting CBI claims under TSCA. See 40 C.F.R. pt. 703. For example, the submitter must certify that information provided to substantiate a CBI claim is true and correct.

[22]EPA provides guidance documents for filing microbial commercial activity notices under TSCA. See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Guidance Documents for Filing a Biotechnology Submission under TSCA (Washington D.C.: Sept. 16, 2024), accessed November 12, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/regulation-biotechnology-under-tsca-and-fifra/guidance-documents-filing-biotechnology-submission. NCD officials told us the division does not currently plan to update the June 1997 Points to Consider document, because it regularly conducts Pre-notice Consultation Meetings with these submitters and microbial commercial activity notices represent a small proportion of the submissions that NCD receives. According to information from EPA, as of November 1, 2024, EPA has received 199 valid microbial commercial activity notices out of the 2,623 new chemical notices that EPA has received since TSCA was amended in 2016. See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Statistics for the New Chemicals Program under TSCA.

[23]Other potential improvements included streamlining the review process for new chemicals with similar characteristics; improving the consistency of risk assessments; duly considering the relative benefits of new chemicals in comparison to existing chemicals; improving transparency about EPA’s use of models and analogues when producing risk assessments; using manufacturer test data; and duly considering manufacturer practical experience. Another potential improvement raised in our interviews was to increase consistency between EPA’s new chemicals review process and other regulatory approaches. The same chemical substance can be regulated in different ways depending on its use. For example, a manufacturer representative noted that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration may review the chemical substance when used as a produce bag; however, EPA may also review the substance under its new chemicals review process for a different commercial use (e.g., consumer product packaging). We recognize that EPA’s ability to increase consistency between its new chemicals review process and other regulatory approaches may depend on changes to existing statutory authorities and requirements, such as TSCA.

[24]According to NCD officials, TSCA, as amended, requires submitters to provide what is “known or reasonably ascertainable,” and, consequently, does not establish specific testing “requirements” prior to submitting a PMN. They noted that EPA may include testing requirements in a section 5(e) order if needed to address risk.

[25]In October 2015, we reported on how Canada manages the human health risks of existing chemicals identified as toxic under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999. Our report did not include a comparison between the Canadian and U.S. new chemical review processes. See GAO, Chemicals Management: Observations on Human Health Risk Assessment and Management by Selected Foreign Programs, GAO‑16‑111R (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 9, 2015).

[26]GAO‑23‑105728. During our review for the 2023 report, EPA officials told us the primary reason the agency missed new chemical review deadlines was because they did not have sufficient resources and expertise. They also identified other factors that contributed to missed deadlines such as guidance gaps, IT challenges, and risk assessment revisions. We recommended EPA develop a process and timeline to fully align its workforce planning efforts for implementing its TSCA chemical review responsibilities with workforce planning principles and incorporate the results, as appropriate, into its annual plan for chemical risk evaluations under TSCA. The agency has partially addressed this recommendation by, for example, developing a Workforce Action Plan with related follow-on goals to address hiring delays and retention challenges.

[27]According to NCD officials, EPA’s Statistics for the New Chemicals Program under TSCA includes links to all active new chemical cases and exemptions. However, the status information that the web page provides for active new chemical cases may not provide granular information that some manufacturers prefer. For example, when we exported data on all active cases from the website in September 2024, we found that EPA provided the following four status categories: (1) awaiting submitter information/action, (2) awaiting submitter signature on order, (3) risk assessment, and (4) risk management.

[28]U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA Announces Initiatives to Improve Efficiency, Worker Protections and Transparency in New Chemical Reviews (Washington, D.C.: June 26, 2024), accessed November 12, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/chemicals-under-tsca/epa-announces-initiatives-improve-efficiency-worker-protections-and.

[29]Specifically, we determined that NCD generally follows three practices, partially follows three practices, and does not follow the remaining seven practices.

[30]Additionally, EPA’s agency-wide strategic plan includes one goal related to new chemical reviews: by September 30, 2026, review 90 percent of past risk mitigation requirements for TSCA new chemical substances decisions compared to the fiscal year 2021 baseline of none. See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, FY 2022–2026 EPA Strategic Plan (Washington D.C.: March 2022), 85.

[31]NCD’s draft strategic plan is subject to change upon further deliberations. NCD officials told us that we could include the draft strategic goals in this report.

[32]The Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey is an organizational climate survey that assesses how employees jointly experience the policies, practices, and procedures characteristic of their agency and its leadership. According to EPA survey results, NCD employees’ positive responses on three key questions related to scientific integrity and trust have improved from 2020 to 2023. For example, positive responses to the survey’s “my supervisor treats me with respect” question increased from 76 percent in 2020 to 100 percent in 2023. Positive responses to the survey’s “I can disclose a suspected violation of any law, rule, or regulation without fear of reprisal” question increased from 33 percent in 2020 to 63 percent in 2023.

[33]As we noted earlier in this report, while we present the topic areas and practices in a certain order, they are interconnected, and two of them—“assess and build evidence” and “use evidence”—are part of an iterative cycle that builds on key actions established in the foundational “plan for results” topic area.

[35]An exposure draft can solicit public comment on a proposed policy or action. Interested parties are invited to read and discuss a preliminary version of a document and express their opinions on its contents to minimize any unintended consequences.