EXPORT CONTROLS

Improvements Needed in Licensing and Monitoring of Firearms

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106849. For more information, contact Nagla'a El-Hodiri at (202) 512-4128 or ElHodiriN@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106849, a report to congressional committees

Export Controls

Improvements Needed in Licensing and Monitoring of Firearms

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. government implements an export control system to manage risks associated with exporting sensitive items while facilitating legitimate trade. In 2020, State and Commerce transferred nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms up to .50 caliber from State’s to Commerce’s export control jurisdiction. The changes were part of a multi-year effort to transfer control of less sensitive items to Commerce and limit the items that State controls to those items that provide the U.S. with a critical military or intelligence advantage.

A House report includes a provision for GAO to review the authorization process for firearms exports following the transfer of jurisdiction. GAO examined (1) how U.S. exports of firearms have changed since the transfer, (2) the Commerce–led interagency export licensing process for firearms, and (3) Commerce’s efforts to monitor the end use of firearms exports. GAO reviewed documents and analyzed data related to firearms licensing, exports, and end-use checks, and interviewed agency officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations, including for State to develop agencywide guidance for export license reviews and for Commerce to address personnel gaps and potentially conflicting duties related to its end-use monitoring efforts. State and Commerce concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

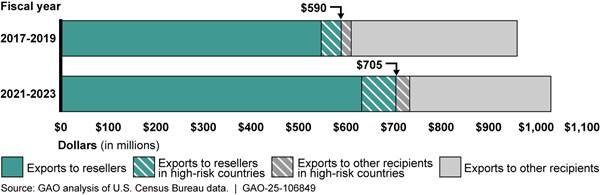

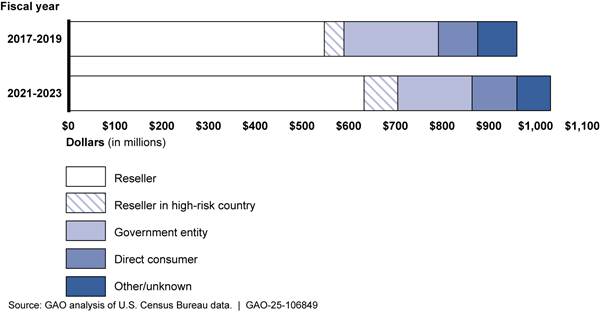

GAO found that the total value of U.S. commercial exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms increased since the export control jurisdiction of these firearms transferred from the Department of State to the Department of Commerce. The value rose by 7 percent, from $960 million to $1.03 billion, when comparing the 3 fiscal years before the transfer (2017–2019) with those after (2021–2023). The increase was driven by substantial increases in the value of exports to resellers, particularly to resellers in countries at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse (see fig.). In 2024, Commerce revised its licensing review processes for firearms exports to help reduce the risk of diversion or misuse.

Note: Values are in 2023 U.S. dollars. “High-risk countries” refers to countries the Departments of State and Commerce identified in April 2024 as high risk for firearms diversion or misuse.

Commerce oversees an interagency licensing process for firearms exports that includes a review by State for U.S. foreign policy and national security concerns. However, GAO found that State’s process for conducting such reviews is fragmented across different bureaus, leading to inconsistent and duplicative efforts. GAO also found that State lacks agencywide guidance for how bureaus should conduct their reviews. Establishing such guidance could help provide greater consistency in State’s reviews and assurance that licensing decisions reflect U.S. foreign policy and national security interests in different countries.

Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) uses end-use checks to ensure that firearms exports are used as intended but lacks dedicated personnel for conducting these checks in regions at high risk for firearms diversion. As a result, BIS may rely on Commerce’s International Trade Administration (ITA) to conduct end-use checks on its behalf. However, conducting end-use checks may conflict with ITA’s primary duties of promoting the commercial interests of U.S. exporters. For example, ITA personnel may connect a U.S. business to a firearms distributor to promote U.S. exports and then later be asked to conduct an end-use check on that distributor, which could restrict those exports. Yet, BIS and ITA do not have guidance on how to segregate potentially conflicting duties. Without guidance, BIS lacks reasonable assurance that ITA personnel have appropriate qualifications and are conducting end-use checks impartially to help mitigate the risk of firearms diversion. Without dedicated personnel to conduct its end-use checks, BIS risks inconsistent end-use monitoring globally.

Abbreviations

|

AECA |

Arms Export Control Act of 1976 |

|

BIS |

Bureau of Industry and Security |

|

CCL |

Commerce Control List |

|

DDTC |

Directorate of Defense Trade Controls |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DRL |

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor |

|

EAR |

Export Administration Regulations |

|

EB |

Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs |

|

ECCN |

Export Control Classification Number |

|

ECO |

Export Control Officer |

|

FAM |

Foreign Affairs Manual |

|

HTSUS |

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the U.S. |

|

IMS-R |

Investigative Management System Redesign |

|

ISN |

Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation |

|

ITA |

International Trade Administration |

|

MOU |

memorandum of understanding |

|

SHOT Show |

Shooting, Hunting, and Outdoor Trade Show |

|

SOP |

standard operating procedure |

|

USML |

U.S. Munitions List |

|

USXPORTS |

U.S. Exports System |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 12, 2025

The Honorable Jerry Moran

Chair

The Honorable Chris Van Hollen

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Hal Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Grace Meng

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The U.S. government implements an export control system to manage risks associated with exporting sensitive items while facilitating legitimate trade. Historically, the Department of State had been responsible for determining whether to allow commercial U.S. exports of most firearms. In March 2020, export control responsibility for most nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms shifted to the Department of Commerce, while State retained responsibility for regulating the export of fully automatic firearms. Commerce later revised its export control requirements in April 2024 after it identified several instances in which firearms legally exported from the U.S. had been diverted or misused, including an instance where a firearm had been diverted and used in a political assassination.

A House report accompanying the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2023, includes a provision for us to review the authorization process for firearms exports following the transfer of jurisdiction.[1] In 2019, prior to the transfer of jurisdiction, we reported on differences in State and Commerce export controls that would have implications for firearms exports if the transfer of jurisdiction were to take effect.[2]

This report examines (1) how U.S. exports of firearms have changed since the transfer of jurisdiction, (2) the Commerce–led interagency export licensing process for firearms, and (3) Commerce’s efforts to monitor the end use of firearms exports. In addition, this report provides information on export license applications and end-use checks before the transfer of jurisdiction (see app. I) and after (see app. II).

To address our first objective, we obtained and analyzed data on U.S. firearms exports from the Automated Export System—the system U.S. exporters use to electronically declare their exports—and interviewed Commerce officials about the data. We assessed the reliability of the data by conducting validity checks and found the data to be sufficiently reliable to describe the value, destinations, and recipients of U.S. exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms during the 3-year periods before and after the transfer of jurisdiction.[3] To focus on commercial firearms exports, we excluded exports involving foreign military sales from our analysis. We used Schedule B and Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the U.S. (HTSUS) codes to identify and analyze U.S. exports of firearms that were most likely under Commerce’s jurisdiction following the transfer of jurisdiction.[4] Schedule B and HTSUS codes do not perfectly separate fully automatic firearms from nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms, so our results could be an underestimate or overestimate of the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports. We chose not to report on the volume of U.S. firearms exports due to inconsistencies in units of the quantity variable in raw Automated Export System data.

To address our second objective, we reviewed documents and interviewed officials from Commerce, State, and the Department of Defense (DOD) to understand the processes in place for reviewing Commerce export license applications. We assessed Commerce’s and State’s licensing review and adjudication processes against (1) federal internal control standards[5] and (2) leading practices for interagency collaboration, which note that written agreements can be used to provide consistency in the long term[6] and are most effective when regularly updated and monitored.[7]

To address our third objective, we reviewed guidance and standard operating procedures for conducting end-use checks from Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS). We interviewed BIS officials, including four current Export Control Officers (ECO) who had conducted end-use checks for firearms or related items during their tours of duty. We also reviewed case notes for end-use checks completed during fiscal years 2021–2023 as context for how BIS guidance and standard operating procedures for conducting end-use checks are implemented. In addition, we interviewed officials from State and Commerce’s International Trade Administration (ITA) to understand their roles in BIS’s end-use monitoring program. We assessed our findings from our reviews and interviews against (1) federal internal control standards;[8] (2) leading practices in interagency collaboration, which call for using written agreements to enhance collaboration;[9] and (3) leading practices in human capital, which call for designing and implementing effective training programs.[10]

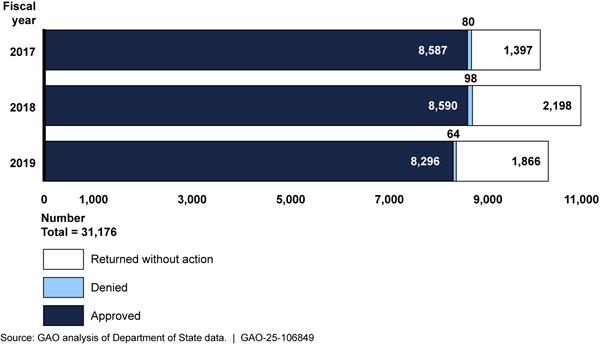

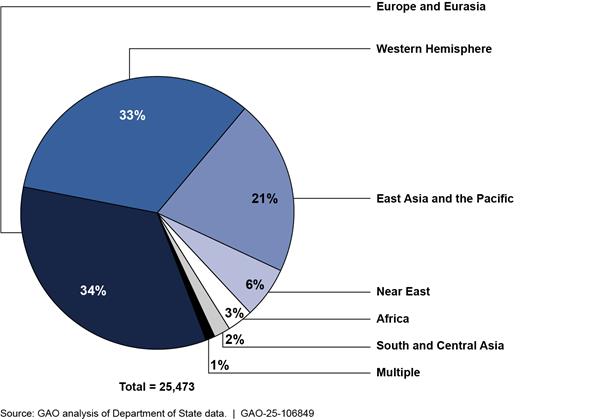

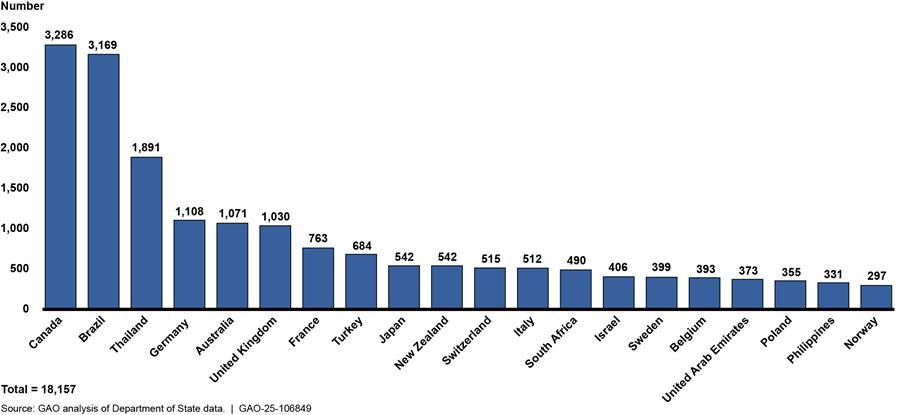

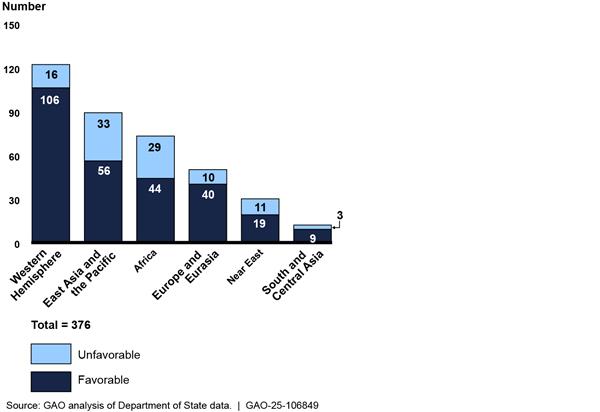

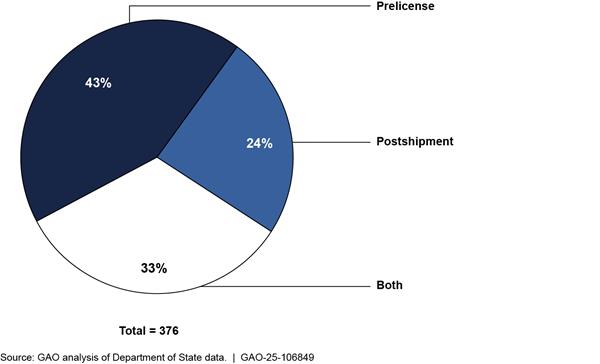

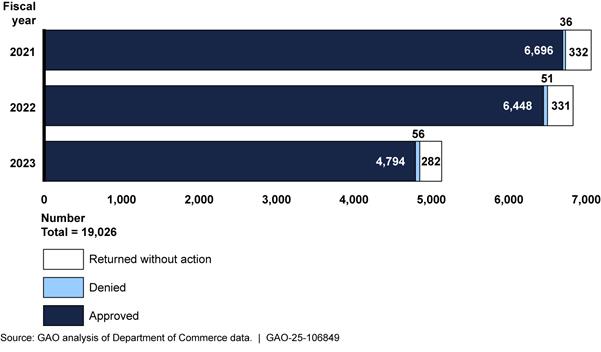

To provide information on export license applications and end-use checks before and after the transfer of jurisdiction, we completed two separate analyses. First, we examined export license applications and end-use checks for firearms and related items under State’s jurisdiction in the 3-year period before the transfer. Second, we examined export license applications and end-use checks for firearms and related items under Commerce’s jurisdiction in the 3-year period after the transfer. For more information about our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix III.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

State and Commerce Export Controls

The U.S. government implements an export control system to manage risks associated with exporting sensitive items and ensure that legitimate trade can still occur. Historically, State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) has controlled the export of those items with inherently military applications—including many firearms and ammunition—on the U.S. Munitions List (USML). At the same time, Commerce’s BIS has controlled the export of less sensitive items with both military and commercial applications—known as dual-use items—on the Commerce Control List (CCL).[11]

State and Commerce both control the export of items within their jurisdictions by implementing licensing requirements, screening license applications against internal watch lists, conducting end-use checks, and supporting investigations by law enforcement agencies of possible violations of export control laws and regulations. Generally, to receive export approval, exporters submit a license application to State if their items are controlled on the USML or to Commerce if they are controlled on the CCL.[12]

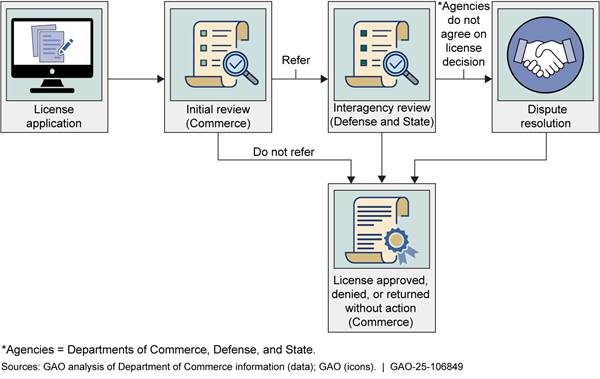

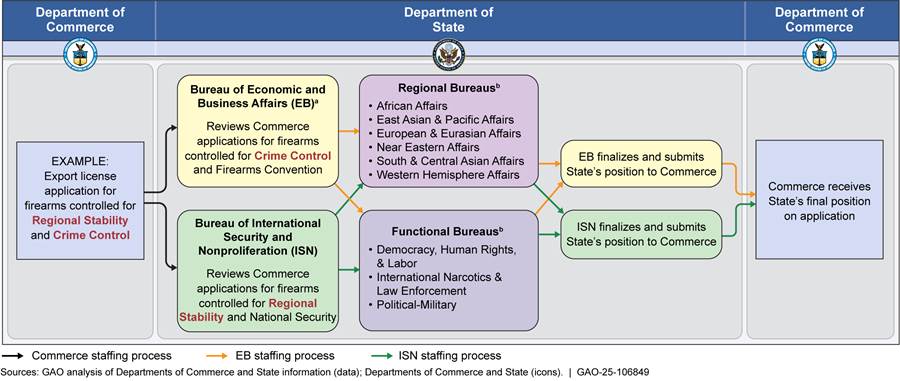

State’s DDTC has primary responsibility for reviewing export license applications for firearms on the USML and may refer applications to other bureaus within State, as well as to DOD, for review. Commerce’s BIS has primary responsibility for reviewing export license applications for firearms on the CCL. Commerce’s process for reviewing export license applications for CCL-controlled firearms also involves opportunities for other departments to review applications, including State and DOD (see fig. 1).[13] Specifically, DOD’s Defense Technology Security Administration and State’s regional and functional bureaus review Commerce export license applications for firearms.[14] State’s review is designed to provide assurance that licensing decisions reflect U.S. foreign policy and national security interests in different countries. Each agency makes a recommendation as to the disposition of the license. If the agencies disagree, the application is escalated through an interagency process outlined in Executive Order 12981.[15] Though these agencies have the authority to review any export license application submitted to Commerce, they may determine that they do not need to review certain types of applications.

Figure 1: Key Steps in Interagency Review Process for Commerce License Applications for Firearms Exports

Note: Commerce’s interagency license review process, including dispute resolution, is outlined in Executive Order 12981: Administration of Export Controls, 60 Fed. Reg. 62,981 (Dec. 8, 1995), as amended. According to Commerce officials, the Department of Energy is not involved in reviewing Commerce license applications for firearms exports but would be part of the dispute resolution process.

State and Commerce can take various actions on the export license applications they receive, including approving the license, approving with conditions, returning without action, or denying the license. State and Commerce can approve an application but place conditions on the export license, such as limiting the validity period or prohibiting certain types of intermediaries in the export transaction. The agencies can return export license applications without action if they are missing information or contain errors. They also can deny, revoke, or suspend a license for foreign policy or national security reasons or if deficient or misleading information was submitted in support of the license’s issuance.

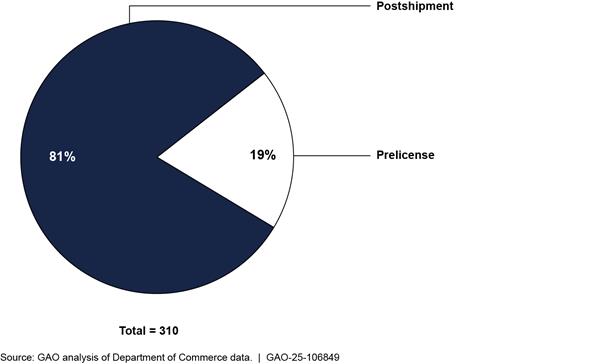

State and Commerce may also conduct end-use checks to verify the reliability of foreign end users and legitimacy of proposed transactions and to provide reasonable assurance of compliance with the terms of the license and proper use of the licensed items.[16] End-use checks include prelicense checks in support of the license application review and postshipment verifications after the license has been approved and items have shipped.[17] Any party to the transaction—including the intermediate consignee, ultimate consignee, end user, and purchaser—may be the subject of an end-use check.[18] If the party subject to the end-use check is not the end user, the check will verify that party’s compliance with their requirements in the transaction. For example, an end-use check of a freight forwarder might verify that the freight forwarder is properly transferring the item but not necessarily verify the item’s final disposition.

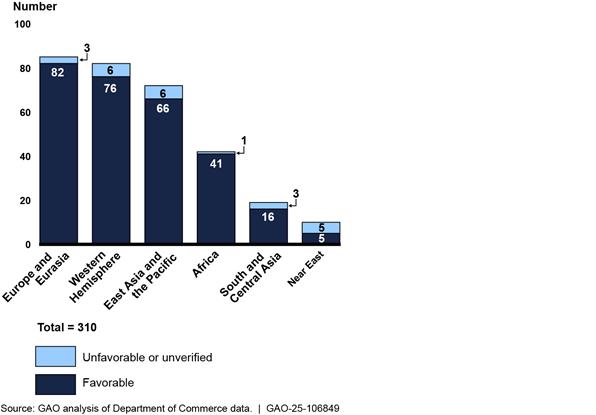

State and Commerce end-use checks may result in “favorable,” “unfavorable,” or “unverified” findings:

· Favorable. The party subject to the end-use check is considered a reliable recipient of U.S. goods.

· Unfavorable. The end-use check reveals facts that are inconsistent with the license or regulations.

· Unverified. The end-use check cannot verify the bona fides (i.e., legitimacy and reliability) of a foreign party.

For either State or Commerce, an “unfavorable” end-use check can lead to denying applications, revoking licenses, removing parties from licenses, updating internal watch lists, or making referrals to U.S. law enforcement agencies for investigation, according to State and Commerce officials. State relies primarily on U.S. embassy staff to conduct end-use checks. Commerce relies primarily on ECOs positioned overseas.

March 2020 Transfer of Certain Firearms from State to Commerce Jurisdiction

State and Commerce published final rules in the Federal Register transferring control over certain firearms exports from State’s to Commerce’s jurisdiction, effective March 9, 2020.[19] The rules were part of a multi-year effort by both agencies to transfer control of less sensitive dual-use items to Commerce and limit the items that State controls to those items that provide the U.S. with a critical military or intelligence advantage or are inherently for military use. The rules further noted that the transfer was expected to reduce the regulatory burden on the U.S. commercial firearms industry. For example, because Commerce does not have a registration requirement or registration and licensing fees, the procedural burden and costs for export license applicants should be reduced.[20] In addition, State requires licenses to be limited to only one end user, while Commerce may allow multiple end users on a single license, reducing the total number of licenses for which an applicant must apply.

Specifically, the rules removed items from the USML under State’s export control jurisdiction and moved them to the CCL under Commerce’s export control jurisdiction.[21] Nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms up to .50 caliber—as well as parts, components, accessories, attachments, and ammunition for these firearms—were among the items transferred from State’s to Commerce’s jurisdiction (see fig. 2). Fully automatic firearms and related items remained on the USML under State’s jurisdiction. Commerce controlled long barrel shotguns prior to the rules going into effect; short barrel shotguns transferred to Commerce with the new rules. See appendixes I and II for more information on export license applications and end-use checks before and after the transfer of jurisdiction.

Figure 2: Examples of Firearms and Ammunition Transferred from Department of State to Department of Commerce Export Control Jurisdiction

October 2023 Commerce Licensing Pause

In October 2023, Commerce paused the issuance of new export licenses involving certain firearms, ammunition, and related items under its jurisdiction. According to Commerce, the pause followed its identification of several instances in which lawfully exported firearms and related items had been diverted or misused in a manner contrary to U.S. national security and foreign policy interests. For example, in one case, a U.S. firearm licensed for export to one country was subsequently diverted to a bordering country and used in a political assassination.[22] Because these instances of diversion largely involved commercial exports to nongovernment end users, Commerce tailored the pause to apply only to exports involving nongovernment end users.[23]

During the pause, Commerce assessed its license review policies for firearms exports to determine whether any changes were warranted to advance U.S. national security and foreign policy interests. As part of its assessment, Commerce requested that State examine whether there are specific destinations in which there is substantial risk of firearms diversion or misuse. In response, State, in consultation with U.S. government stakeholders, developed a methodology for identifying such destinations.

May 2024 Commerce Rule Changes

In May 2024, Commerce amended its licensing requirements and license review policies for firearms exports. According to Commerce, the changes were designed to help reduce the risk of legally exported firearms and related items being diverted or misused.[24] Among the changes, Commerce, in consultation with U.S. government stakeholders, took the following actions:

· Adopted State’s methodology for identifying high-risk destinations. State identified a set of factors that correlate with an increased risk of a firearm exported to a certain destination being diverted or misused in a manner adverse to U.S. national security and foreign policy. Commerce export license applications for firearms will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis against these factors to determine the risk of diversion or misuse. The factors that will be considered include, but are not limited to, destination-specific national security and foreign policy risk factors, including firearms trafficking, terrorism, human rights concerns and political violence, state fragility, corruption, organized crime or gang activity, and drug trafficking.

· Adopted a “presumption of denial review policy” for firearms export license applications involving nongovernment end users in 36 high-risk countries. On the basis of State’s methodology for identifying high-risk destinations, State developed and Commerce adopted a list of 36 countries where firearms exports to nongovernment end users entail a substantial risk of being diverted or misused in a manner adverse to U.S. national security and foreign policy.[25] Commerce will apply a “presumption of denial review policy” for firearms export license applications involving nongovernment end users in these countries. Commerce will deny such applications unless exporters demonstrate that a specific transaction does not present a substantial risk of diversion or misuse. Commerce also revoked existing licenses to nongovernment end users in these countries, effective July 1, 2024.[26] Commerce determined that a presumption of denial, as opposed to an absolute prohibition, would provide it with the flexibility to tailor the licensing review process to the individual facts and related policy interests.

· Reduced the general validity period for firearms export licenses from 4 years to 1 year. Commerce amended its regulations to reduce the general validity period from 4 years to 1 year for all future export licenses involving firearms and related items. Commerce determined that national security and foreign policy considerations abroad can change rapidly and shortening the general validity period for firearms export licenses would enable the licensing review process to account for such developments.

· Established import certificate requirement for firearms export license applications. Prior to the 2024 rule changes, exporters were not required to submit an import certificate with Commerce firearms export license applications, unless specifically requested by Commerce or the applications involved Organization of American States member countries.[27] Following the rule changes, all Commerce firearms export license applications must include an import certificate or permit when required by the importing country. According to Commerce, this requirement will help ensure that the importing country’s government is aware of the shipment and has confirmed that the import is lawful.

· Established purchase order requirement for certain firearms export license applications. Prior to the 2024 rule changes, exporters were not required to submit a purchase order with Commerce firearms export license applications, unless specifically requested by Commerce. Following the rule changes, purchase orders must be submitted with Commerce firearms export license applications involving certain countries.[28] Commerce generally limits the quantity licensed for export to the quantity specified on a purchase order.

Table 1 summarizes certain similarities and differences in licensing and end-use monitoring requirements for most nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports during three periods:

· under State’s USML (before the 2020 rule changes),

· under Commerce’s CCL (after the 2020 rule changes), and

· under Commerce’s CCL (after the 2024 rule changes).

Commerce’s licensing and end-use monitoring requirements for firearms exports following the 2024 rule changes share some similarities with and differences from those during previous periods. Key differences relate to registration, general license validity period, and number of end users on a license.

Table 1: Examples of Licensing and End-Use Monitoring Requirements for Most Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms Before and After Recent Rule Changes

|

Requirement |

State’s USML (before 2020 rulea) |

Commerce’s CCL (after 2020 rulea) |

Commerce’s CCL (after 2024 ruleb) |

|

Registration. Applicant must register and pay fees. |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

General validity period. Length of time that an export license is valid. |

4 years |

4 years |

1 year |

|

Purchase order. Applicant must submit a purchase order. |

Yes |

No |

For certain applications |

|

Multiple end users. A single license can include multiple end users. |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Screening. Applicants are screened against watch/proscribe lists. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Interagency review. Applications involve an interagency review. |

Noc |

Yes, State and DODd |

Yes, State and DODd |

|

End-use monitoring. Parties to the transaction can be targeted for a prelicense or postshipment check. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

USML = U.S. Munitions List; CCL = Commerce Control List

Source: GAO analysis of Departments of State and Commerce information. | GAO‑25‑106849

aDepartment of State, International Traffic in Arms Regulations: U.S. Munitions List Categories I, II, and III, 85 Fed. Reg. 3,819 (Jan. 23, 2020). Department of Commerce, Control of Firearms, Guns, Ammunition and Related Articles the President Determines No Longer Warrant Control under the United States Munitions List (USML), 85 Fed. Reg. 4,136 (Jan. 23, 2020).

bDepartment of Commerce, Revisions of Firearms License Requirements, 89 Fed. Reg. 34,680 (Apr. 30, 2024).

cThe Department of Defense (DOD) declined to review export license applications for nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms before the 2020 rule but not after the 2020 rule when those firearms transferred from State’s to Commerce’s jurisdiction, according to DOD officials.

dAccording to Commerce officials, the Department of Energy is not involved in reviewing Commerce’s export license applications for firearms but would be part of Commerce’s dispute resolution process when the agencies involved in the initial application reviews disagree on the final disposition of the application.

Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms Increased After 2020 Transfer of Jurisdiction, Particularly to Resellers and High-Risk Countries

Total Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms Increased After 2020 Transfer of Jurisdiction

The total value of U.S. commercial exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms increased by 7 percent when comparing the 3-year periods before and after the transfer of jurisdiction from State to Commerce.[29] The U.S. exported about $960 million of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms in fiscal years 2017–2019, and about $1.03 billion of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms in fiscal years 2021–2023 (see tab. 2).[30] This increase was driven by increases in the value of U.S. exports of these firearms to resellers and to direct consumers. There was also a substantial increase in the value of such exports to countries on State’s and Commerce’s high-risk list for firearms diversion or misuse.

Table 2: Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms, Fiscal Years 2017–2019 and 2021–2023

|

Fiscal years 2017–2019 (millions)a |

Fiscal years 2021–2023 (millions)b |

Change (percentage) |

|

|

All exports |

$960 |

$1,032 |

7% |

|

By recipient type |

|||

|

Reseller |

$590 |

$705 |

20% |

|

Government entity |

$202 |

$159 |

-21% |

|

Direct consumer |

$84 |

$96 |

14% |

|

Other/unknownc |

$84 |

$72 |

-15% |

|

By high-risk listd |

|||

|

High-risk countries |

$63 |

$101 |

60% |

|

Other countries |

$897 |

$931 |

4% |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. I GAO‑25‑106849

Note: Values are in 2023 U.S. dollars and represent the sum of dollar values of U.S. commercial exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms, including the cost of domestic freight and insurance, as reported by exporters. Data for fiscal year 2020 were not included in this analysis because the transition of jurisdiction for these firearms occurred during that fiscal year. According to Census officials, the data we obtained do not perfectly separate fully automatic firearms from nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms. For this reason, our results could be an underestimate or overestimate of the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports.

aDuring this period, 11 percent of the total value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports was shipped with a Department of Commerce license or license exception. Some items, such as long barrel shotguns, were under Commerce’s jurisdiction during this time.

bDuring this period, 98 percent of the total value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports was shipped with a Commerce license or license exception. Department of State licenses for firearms exports generally expire after 4 years, so some State export licenses for firearms that transferred to Commerce’s jurisdiction in fiscal year 2020 could still be valid in fiscal year 2023.

cCensus defines “other/unknown” as any recipient that is not a reseller, government entity, or direct consumer, or whose recipient type is not known at the time of export. There was a higher value of U.S. firearms exports to “other/unknown” recipients in fiscal year 2017 than during the rest of our study period. This could partly explain the increase we see in the value of U.S. firearms exports to resellers and to direct consumers. As a robustness check, we excluded fiscal year 2017 from our results and found even larger increases in the value of U.S. firearms exports to resellers and to direct consumers after the transfer of jurisdiction.

dIn April 2024, State developed and Commerce adopted a list of 36 countries at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse.

Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms Increased to Countries at High Risk for Diversion or Misuse

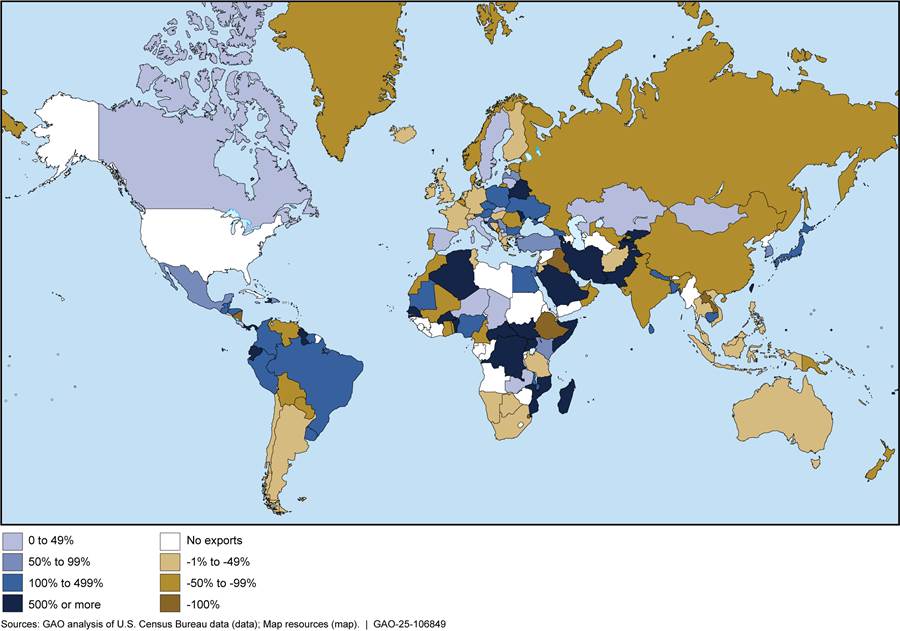

Since 2020, Commerce has identified South America, Africa, and Central Asia as regions at risk for firearms diversion. As shown in figure 3, the value of U.S. exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms increased to a number of countries in these regions, when comparing the 3-year periods before and after the transfer of jurisdiction.[31]

Figure 3: Change in Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms by Destination, from Fiscal Years 2017–2019 to 2021–2023

Note: The percentages in this figure represent the change in the inflation-adjusted total dollar value of U.S. commercial exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms in fiscal years 2021–2023, as compared to fiscal years 2017–2019. Data for fiscal year 2020 were not included in this analysis because the transition of jurisdiction for these firearms occurred during that fiscal year. According to Census officials, the data we obtained do not perfectly separate fully automatic firearms from nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms. For this reason, these results could be an underestimate or overestimate of changes in value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports.

In 2024, State developed and Commerce adopted a list of 36 countries—mostly located in the Western Hemisphere and Africa—at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse. The overall value of U.S. exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms to these countries increased by 60 percent, or $38 million, when comparing the 3-year periods before and after the transfer of jurisdiction. Although the value of such exports declined to some of these countries, 25 (or 69 percent) of the 36 high-risk countries received an increase in the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports during this period. The largest increases by value of U.S. exports were to: Pakistan (1,400 percent, or $16 million); Guatemala (116 percent, or $12 million); and Panama (20,676 percent, or $8 million). See table 3.

Table 3: Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms to High-Risk Countries, Fiscal Years 2017–2019 and 2021–2023

|

High-risk countrya |

Fiscal years 2017–2019 (thousands)b |

Fiscal years 2021–2023 (thousands)c |

Change (percentage)d |

|

Uganda |

$1 |

$191 |

22,594% |

|

Panama |

$37 |

$7,653 |

20,676% |

|

Pakistan |

$1,108 |

$16,618 |

1,400% |

|

Guyana |

$32 |

$352 |

986% |

|

Ecuador |

$77 |

$578 |

655% |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

$487 |

$3,309 |

580% |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

$1,314 |

$8,036 |

512% |

|

Suriname |

$335 |

$1,852 |

452% |

|

Belize |

$328 |

$1,737 |

429% |

|

Bangladesh |

$810 |

$3,964 |

389% |

|

Nigeria |

$62 |

$229 |

270% |

|

Colombia |

$1,080 |

$3,498 |

224% |

|

Honduras |

$1,000 |

$3,005 |

200% |

|

Peru |

$1,765 |

$4,631 |

162% |

|

Nepal |

$2 |

$5 |

133% |

|

Guatemala |

$10,610 |

$22,896 |

116% |

|

Dominican Republic |

$551 |

$953 |

73% |

|

Bahamas |

$504 |

$749 |

49% |

|

Kazakhstan |

$1,430 |

$2,075 |

45% |

|

Chad |

$25 |

$34 |

35% |

|

Niger |

$226 |

$293 |

30% |

|

Jamaica |

$2,953 |

$3,015 |

2% |

|

Tajikistan |

$0 |

$157 |

N/Ae |

|

Burkina Faso |

$0 |

$5 |

N/Ae |

|

Mozambique |

$0 |

$1 |

N/Ae |

|

Burundi |

$0 |

$0 |

N/Ae |

|

Yemen |

$0 |

$0 |

N/Ae |

|

Malaysia |

$1,883 |

$1,400 |

-26% |

|

Vietnam |

$484 |

$344 |

-29% |

|

El Salvador |

$8,194 |

$5,500 |

-33% |

|

Indonesia |

$13,369 |

$7,398 |

-45% |

|

Bolivia |

$3,376 |

$660 |

-80% |

|

Papua New Guinea |

$283 |

$32 |

-89% |

|

Mali |

$677 |

$58 |

-91% |

|

Paraguay |

$9,959 |

$6 |

-100% |

|

Laos |

$143 |

$0 |

-100% |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. I GAO‑25‑106849

Note: Values are in 2023 U.S. dollars and represent the sum of dollar values of U.S. commercial exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms, including the cost of domestic freight and insurance, as reported by exporters. Data for fiscal year 2020 were not included in this analysis because the transition of jurisdiction for these firearms occurred during that fiscal year. According to Census officials, the data we obtained do not perfectly separate fully automatic firearms from nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms. For this reason, our results could be an underestimate or overestimate of the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports.

aIn April 2024, the Department of State developed and the Department of Commerce adopted a list of 36 countries at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse. This list does not capture U.S. arms–embargoed countries, which are reviewed under a policy of denial. Those countries are Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma, Cambodia, Central African Republic, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cuba, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Lebanon, Libya, Nicaragua, Russia, Somalia, Republic of South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe. See 22 C.F.R. 126.1 and 15 C.F.R. Part 740 Supplement No. 1 for specific regulatory requirements for U.S. arms–embargoed countries.

bDuring this period, 8 percent of the total value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports to high-risk countries was shipped with a Commerce license or license exception. Some items, such as long barrel shotguns, were under Commerce’s jurisdiction during this time.

cDuring this period, 99 percent of the total value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports to high-risk countries was shipped with a Commerce license or license exception. State licenses for firearms exports generally expire after 4 years, so some State export licenses for firearms that transferred to Commerce’s jurisdiction in fiscal year 2020 could still be valid in fiscal year 2023.

dPercentage changes are based on actual values prior to rounding.

eThere were $0 in U.S. exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms to Tajikistan, Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Burundi, and Yemen in fiscal years 2017–2019, therefore the percentage changes in exports to these countries are mathematically undefined or indeterminant.

U.S. firearms exports to nongovernment end users in countries on State’s and Commerce’s high-risk list entail a substantial risk of being diverted or misused in a manner adverse to U.S. national security and foreign policy. In May 2024, Commerce adopted a “presumption of denial review policy” for firearms export license applications involving nongovernment end users in the 36 high-risk countries shown in table 3. Commerce will deny such applications unless exporters demonstrate that a specific transaction does not present a substantial risk of diversion or misuse. Further, in July 2024, Commerce revoked existing licenses to nongovernment end users in these 36 countries.[32]

Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms Increased to Resellers and Direct Consumers

Both before and after the transfer of jurisdiction, resellers received the majority of the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports.[33] However, as shown in figure 4, when comparing the 3-year periods before and after the transfer of jurisdiction, the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports to resellers increased by 20 percent, or $115 million. The value of U.S. exports of these firearms to direct consumers also increased in this period, by 14 percent, or $12 million.[34] The value of such exports to government entities declined by 21 percent, or $43 million.

A number of these exports to resellers were in countries where firearms are at high risk for diversion or misuse. As shown in figure 4, the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports to resellers in high-risk countries increased by 72 percent, or $30 million, when comparing the 3-year periods before and after the transfer of jurisdiction.

Figure 4: Value of U.S. Exports of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms by Recipient Type, Fiscal Years 2017–2019 and 2021–2023

Note: Values are in 2023 U.S. dollars and represent the sum of dollar values of U.S. commercial exports of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms, including the cost of freight and insurance, as reported by exporters. Data for fiscal year 2020 were not included in this analysis because the transition of jurisdiction for these firearms occurred during that fiscal year. According to Census officials, the data we obtained do not perfectly separate fully automatic firearms from nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms. For this reason, our results could be an underestimate or overestimate of the value of U.S. nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms exports.

Commerce determined that the risk of firearms diversion is significantly higher for exports to nongovernment entities, such as resellers and direct consumers, than for exports to government end users. For example, Commerce found instances of firearms exports being diverted to Russia via commercial resellers in third countries. Such firearms may be used to support Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, according to Commerce. As previously noted, in May 2024, Commerce adopted a “presumption of denial review policy” for firearms export license applications involving nongovernment end users, such as resellers and direct consumers, in countries at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse.

Processes and Guidance Related to the Interagency Review of Nonautomatic and Semiautomatic Firearms Export Licenses Could Be Improved

Commerce leads an interagency review process to adjudicate nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms export license applications under its jurisdiction. This process includes a review by State bureaus for foreign policy concerns. However, we found that State’s current process for reviewing Commerce export license applications for firearms is fragmented and duplicative. We also found that State does not have agencywide guidance for how bureaus should conduct reviews, including collecting input from those bureaus on which applications State should review. We found that State’s primary bureau for reviewing Commerce export license applications for firearms does not have access to State’s internal watch list used to screen end users on export license applications. Lastly, State and Commerce also let an interagency agreement expire because they do not have procedures in place to review agreements to ensure they are still in effect.

State’s Fragmented and Duplicative License Review Process May Lead to Inconsistent Reviews and Duplication of Effort

State reviews export license applications for Commerce-controlled firearms to provide assurance that licensing decisions reflect U.S. foreign policy and national security interests in different countries. However, State’s process for conducting such reviews is fragmented across different bureaus, which creates inconsistency and unnecessary duplication.[35]

State’s Foreign Affairs Manual delegates authority to the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation (ISN) to coordinate the agency’s position on Commerce export license applications and does not delegate any such authority to the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs (EB).[36] However, State’s reviews of export license applications for Commerce-controlled firearms are coordinated by both bureaus—ISN and EB—depending on the reasons for the export controls, according to State officials. There are four controls that Commerce applies to firearms: (1) National Security, (2) Regional Stability, (3) Crime Control, and (4) Firearms Convention.[37] Commerce staffs applications to State via the interagency licensing platform, the U.S. Exports System (USXPORTS).[38] The platform routes applications that are controlled for National Security and Regional Stability to ISN. The platform routes applications that are controlled for Crime Control and Firearms Convention to EB. However, State officials noted that firearms are generally controlled for multiple reasons and can involve controls that overlap the bureaus, such as an application involving both Regional Stability and Crime Control. When there is overlap, the platform routes applications to both bureaus. According to State officials, it is common to have an application routed to both ISN and EB.[39]

State officials told us that ISN and EB then review applications and staff them to regional or functional bureaus, as appropriate, to review the applications for issues relevant to their subject matter expertise. For example, an application with a human rights concern in the Western Hemisphere might be staffed to both State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor and Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. Those bureaus return the application to either ISN or EB with their recommendation on the application. The coordinating bureau—either ISN or EB—then finalizes State’s position in consideration of the reviewing bureaus’ recommendations and returns the application with that position to Commerce.

Officials in EB told us they felt their role in the process was duplicative because ISN was already reviewing most of the applications routed to them. The officials also explained that EB is not set up like ISN to substantively review firearms export license applications. In particular, EB officials said they do not have the same expertise and do not have access to the information ISN uses to screen end users against ISN’s firearms distributors database, view their application history, or identify trends. As a result, EB officials told us that the bureau’s practice is to defer to ISN and copy ISN on all firearms-related reviews. However, the officials told us that even the process of deferring to ISN takes a substantial amount of time because of how the licensing platform is set up. For example, even if deferring to ISN, EB officials must still process the applications routed to them by Commerce via the platform, which, as one EB official told us, might include aggregating other bureaus’ reviews while not necessarily conducting one of their own. Figure 5 illustrates an example of how the review process could flow if a license application were routed to both EB and ISN.

Figure 5: Example of Department of State Process for Reviewing Commerce License Applications for Firearms Exports

aWhile coordination is generally shared, EB officials told us that they often defer to ISN when Commerce routes an export license application to both ISN and EB.

bRegional and Functional Bureau reviews are at the discretion of EB and ISN and may depend on the specifics of the transaction.

ISN officials told us this duplicative review process predated their tenure at the agency and that, due to turnover in both bureaus, they could not explain the rationale for the review process. Officials in ISN and EB told us that, prior to the 2020 transfer, EB had historically reviewed export license applications for Commerce-controlled firearms, such as shotguns, because they were controlled under Crime Control. However, the officials were not sure why that was the case and were confused why EB remains a coordinator for certain applications. ISN officials told us that, at some point, ISN and EB would determine whether and how to adjust internal roles and responsibilities.

Federal internal control standards state that management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[40] For example, when designing control activities, management should (1) divide key duties and responsibilities, including those for authorizing and reviewing transactions; (2) ensure transactions are authorized and executed only by persons acting within the scope of their authority; and (3) clearly communicate those authorizations to personnel.

Without a consolidated coordination of State’s position, State creates a fragmented review process, which makes it difficult to ensure that all export license applications for Commerce-controlled firearms receive the same level of review. For example, applications routed only to EB might not be vetted to the same degree as ISN because EB does not have the same firearms experts or internal resources, such as ISN’s database of firearms distributors. Additionally, ISN and EB may not be including the same bureaus and offices in State’s reviews. As a result, some of State’s reviews of export license applications for Commerce-controlled firearms might not be considering all the relevant information or consulting the appropriate expertise, which could increase the risk of firearms being exported to unauthorized end users.

The fragmented review process also creates unnecessary duplication, as most applications are routed to both coordinating bureaus for concurrent review, which results in pulling EB’s resources from other areas of focus where it has relevant subject matter expertise. An EB official said that, because of the 2024 rule change, the volume of applications Commerce routes to EB increased substantially. As a result, in July 2024, the official told us EB had to assign an additional staff member to work on Commerce export license applications and that time spent on reviewing them had gone up by about half.

State Lacks Written Agencywide Guidance for Conducting Commerce Export License Reviews and Determining Which Licenses It Should Review

State lacks agencywide guidance for its bureaus involved in reviewing export license applications for Commerce-controlled firearms. While some reviewing bureaus at State had bureau-level guidance, we found there was no agencywide guidance for reviewing those applications, making recommendations to Commerce, or recording the factors or reasons the reviewing bureaus took into consideration in their recommendations. Additionally, we found that State did not have written guidance for determining which applications the agency would review.

No agencywide guidance and inconsistent bureau-level guidance for reviewing Commerce export license applications. State lacks agencywide guidance to inform bureau-level reviews of Commerce export license applications. While ISN has guidance for its internal reviews, there is no agencywide guidance for the other bureaus to which ISN and EB refer applications for further review. In the absence of agencywide guidance, the reviewing bureaus have developed a patchwork of standard operating procedures (SOP) and guidance documents. For example, some of the bureaus had step-by-step guidance for processing applications in the case management system, including time frames. Other bureaus had guidance documents that outlined considerations for the reviewers, such as which sources to consult when conducting reviews (e.g., publicly available published reports). Some bureaus did not have guidance documents.

Without written agencywide guidance, bureau officials told us they were not always clear on how the review process worked. For example, in one bureau, officials were unaware of key aspects of Commerce’s review process, such as whether applications had to be reviewed within a certain time frame. In another bureau, an official told us there had been a couple of cases where the bureau would have recommended a denial, but it was not familiar with Commerce’s review time frames and did not respond in time to those review requests. As a result, State moved forward with its final recommendations on those applications and Commerce ultimately approved them.[41]

In another example, officials from one bureau told us they were unsure whether Commerce licenses allowed for end-use checks and, as a result, did not think they could request such checks as part of their reviews.

Officials from the reviewing bureaus told us an agencywide guidance document would be helpful for them to better understand State’s review process for Commerce export license applications.

Officials from the reviewing bureaus told us they were not part of the export license application review process around the time of the 2020 transfer, either because they worked in another role or did not yet work for the agency. Thus, they were unable to provide information regarding why State did not have agencywide guidance for such reviews. In July 2024, an ISN official told us the reviewing bureaus could reach out to them for verbal guidance about the export license application review process.

Federal internal control standards state that management should establish an organizational structure, assign responsibility, and delegate authority to achieve the entity’s objectives.[42] For example, management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system to establish and communicate the who, what, when, where, and why of internal control execution—such as license adjudication processes—to personnel. Federal internal control standards further state that management should implement control activities through policies.[43] This principle is further supported by State’s Foreign Affairs Manual, which also states that program managers implement control activities through policies.[44]

Without written agencywide guidance for conducting reviews, bureaus may develop partial or inconsistent guidance for their staff, if they develop any at all. Agencywide guidance could help State better ensure its reviews of Commerce export license applications are consistent and thoroughly satisfy State’s obligations in the review process.

No agencywide guidance for determining which Commerce export license applications to review. State also lacks agencywide guidance for determining which types of Commerce export license applications to review. State and other reviewing agencies can decline to review certain types of Commerce applications by submitting “do-not-staff memos” to Commerce for those applications.[45] For example, State may choose not to review applications for firearms to specific countries and that are under a certain dollar value. Once Commerce receives those memos, it programs its licensing platform to no longer route those types of applications to the reviewing agency until notified otherwise, according to State officials. As a result, Commerce does not receive input from agencies that decline to review these applications under do-not-staff status.

We found that in 2020, ISN—as State’s lead coordinator for Commerce export license applications—had declined for State to review certain types of applications for firearms exports to 47 countries. Of those countries, seven were on the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor’s (DRL) 2023 list of “Countries for Review in Leahy and Munitions Vetting,” which identifies countries requiring additional review by DRL for human rights considerations.[46] For example, one do-not-staff memo said State did not wish to review applications under a certain value for government end users in Mexico. However, Mexico was on the 2023 DRL list as a country for which government end users should be reviewed.

Officials from all the reviewing bureaus with which we spoke told us they were unaware that the do-not-staff memos existed and were, thus, unaware that ISN had declined State’s authority to review those types of applications. As previously noted, these officials told us they either did not work at State or were not assigned to review export license applications around the time of the 2020 transfer. Therefore, they were unable to confirm whether ISN had consulted with their bureaus when developing the do-not-staff memos in 2020. In October 2024, ISN officials provided us with evidence that at least one bureau had reviewed and approved the 2020 do-not-staff memo for their region but were unable to show us whether the other bureaus had been consulted for their do-not-staff memos.

Officials in State’s reviewing bureaus told us they were concerned that applications from certain countries would have been included in the memos without their consultation and, as a result, they were not seeing applications that might merit review. The officials also told us that blanket declinations should be reviewed periodically because circumstances in a country or region can change quickly. For example, an official in DRL told us the agency reviews its country lists annually to help ensure they reflect current conditions.

In July 2024, ISN officials told us the do-not-staff-memos had been under internal review following Commerce’s 2023 licensing pause, and any future memos would be reviewed at least annually with the reviewing bureaus’ input during that process. However, ISN’s licensing SOP does not address consulting with other bureaus to develop or periodically review do-not-staff memos. In October 2024, ISN officials reiterated that the bureau would annually review the memos and seek the other bureaus’ input but did not yet have a process in place to do so.

Federal internal control standards state that management should establish an organizational structure, assign responsibility, and delegate authority to achieve the entity’s objectives.[47] For example, management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system to establish and communicate the who, what, when, where, and why of internal control execution to personnel. Federal internal control standards further state that management should implement control activities through policies.[48] This principle is further supported by State’s Foreign Affairs Manual, which also states that program managers implement control activities through policies.[49]

ISN officials told us that several positions in State’s bureaus are often staffed with Foreign Service Officers who rotate every few years. As a result, the officials said institutional knowledge can be lost and continuity of processes can be disjointed when practices, such as consulting with regional bureaus to develop and review do-not-staff memos, are not written down in guidance.

State’s involvement in Commerce’s licensing process is designed to provide assurance that licensing decisions reflect U.S. foreign policy and national security interests in different countries. Without written guidance for consulting reviewing bureaus when developing do-not-staff memos, ISN may inadvertently prevent those bureaus from opining on applications that fall within their scopes of expertise.

State’s Bureau Primarily Responsible for Reviewing Commerce Firearms Licenses Lacks Access to Watch List to Screen License Applicants

In 2019, State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) began sharing its internal watch list with BIS in anticipation of Commerce taking over responsibility for export licensing of nonautomatic and semiautomatic firearms.[50] However, State officials told us ISN does not have access to that watchlist as it coordinates and conducts State’s reviews of Commerce export license applications.

DDTC and BIS each maintain an internal watch list to screen all parties identified on export license applications. A watch list match would trigger further review of the license and ultimately could result in the denial of a license. DDTC and BIS also use watch lists as a means of targeting transactions for possible end-use checks to verify the legitimacy of end users of controlled exports. Both agencies’ watch lists include any derogatory information they collect internally from their past screening and end-use monitoring of licenses. For example, if information is identified raising questions about the legitimacy of a party to a license during the license application review, that information would be used to update the watch list to inform future license application reviews.

In 2019, DDTC and BIS entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to share their watch lists with each other.[51] However, ISN does not have access to DDTC’s internal watch list to facilitate its reviews of Commerce export license applications.[52] ISN officials told us that they received relevant information from the watch list in the year immediately following the transfer, but have not received continued access to that list. DDTC officials responsible for the watch list confirmed that ISN does not have access to the watch list and had not requested such access.

ISN officials told us they used the information provided after the transfer to compile their own tracking and management database but said full access to DDTC’s internal watch list would facilitate their reviews of Commerce export license applications. For example, ISN officials told us that an applicant may apply for licenses for both a CCL-controlled and a USML-controlled commodity. Because DDTC is still responsible for adjudicating export licenses for USML-controlled firearms, DDTC officials told us their internal watch list may contain derogatory information about that applicant that would be useful to ISN’s review.

While BIS has access to information from DDTC’s watch list, ISN officials noted that they could more effectively leverage their expertise to support Commerce’s review by using the watch list information coupled with licensing data to identify and research concerning trends in firearms exports. For example, ISN officials used licensing data to identify several concerning, high-risk trends in 2023. ISN officials told us that bringing these trends to Commerce’s attention contributed to the May 2024 changes to Commerce’s licensing policies. One of those trends was an increase in license applications for high-value firearms exports to poorer countries in Central and South America, which ISN officials found concerning. For example, in Guatemala, where the World Bank estimates that, in 2023, more than half of the population lived in poverty, ISN told us they identified 43 different resellers or distributors for high-value firearms. ISN officials told us that access to DDTC’s watch list would allow them to do more research about the end users identified in such trends, which they said would ultimately provide greater fidelity to the interagency licensing process.

Information sharing is supported by a policy statement included in the Export Control Reform Act of 2018. The statement says that among other factors, the “export control system must ensure that it is transparent, predictable, and timely, has the flexibility to be adapted to address new threats in the future, and allows seamless access to and sharing of export control information among all relevant U.S. national security and foreign policy agencies.”[53] Additionally, federal internal control standards state that management should internally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[54] Management should communicate quality information down and across reporting lines to enable personnel to perform key roles in achieving objectives and addressing risks. Without access to DDTC’s internal watch list, ISN may lack critical information needed to effectively screen license applicants for firearms exports and target possible cases for end-use monitoring to ensure that these exports are used as intended and by legitimate end users.

Commerce and State Do Not Have Processes for Periodically Reviewing Their Interagency MOU on Sharing Watch List Information

As previously discussed, in 2019, State and Commerce developed a process for sharing internal watch list information to aid in the oversight of firearms exports and formalized it in an MOU. However, we found that State and Commerce do not have a process in place to periodically review interagency agreements to ensure they still are in effect. As a result, their MOU expired in November 2022, which officials at State and Commerce did not realize until about 2 weeks after it had lapsed.

In November 2022, after the MOU expired, officials at both agencies informally agreed to continue sharing watch list information in the spirit of the original agreement while they worked to update and implement a new MOU. State officials told us State and Commerce were sharing data weekly from their respective watch lists. Commerce officials told us a new MOU was a priority for both agencies. However, as of January 2025, the agencies had not signed a new or revised MOU, more than 2 years after it expired. Neither State nor Commerce officials could explain why the MOU lapsed. As of January 2025, State and Commerce officials told us they were finalizing an extension to the original MOU.

We have previously reported that written agreements are most effective when they are regularly monitored and updated.[55] Additionally, leading practices for interagency collaboration note that written agreements can be used to provide consistency in the long term, especially when there are changes in leadership.[56] With staff turnover, as well as changes in administrations, the need to maintain institutional knowledge becomes even more important. Without an MOU in place, State and Commerce risk losing crucial information about processes and procedures related to their mutual sharing of watch lists, which could disrupt the flow of information from one agency to the other. As we noted in our 2019 report, the agencies’ watch lists provide critical information to one another to effectively screen applicants and target licenses for end-use monitoring.[57] Without each other’s watch list information, State and Commerce may lack critical information needed to ensure that exported firearms are used as intended and by legitimate end users.

Commerce’s End-Use Monitoring of Firearms Hampered by Staffing Gaps, Limited Training, Potentially Conflicting Duties, and Insufficient Timeliness Data

End-use monitoring is a key component of Commerce’s export control system for firearms. End-use checks help to verify the legitimacy of exports of firearms under Commerce’s jurisdiction and determine the reliability of the parties to the transaction. However, we found that Commerce’s end-use monitoring efforts are hampered by several factors, such as personnel gaps, limited training, potentially conflicting duties, and insufficient data.

BIS Lacks Dedicated Personnel to Conduct End-Use Monitoring in Regions at Highest Risk for Firearms Diversion

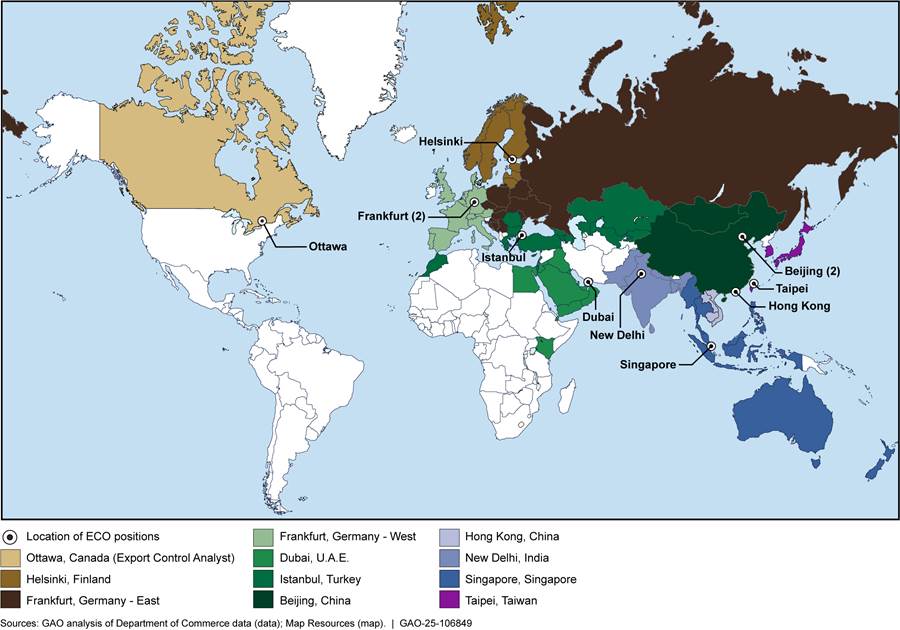

BIS relies primarily on overseas law enforcement personnel known as Export Control Officers (ECO) to conduct end-use monitoring. However, BIS lacks ECOs covering the Western Hemisphere and Africa, two regions at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse. As a result, when BIS wants to conduct an end-use check in a country in one of these two regions, BIS must rely on non-ECO personnel who may lack the appropriate qualifications to conduct end-use checks on BIS’s behalf.

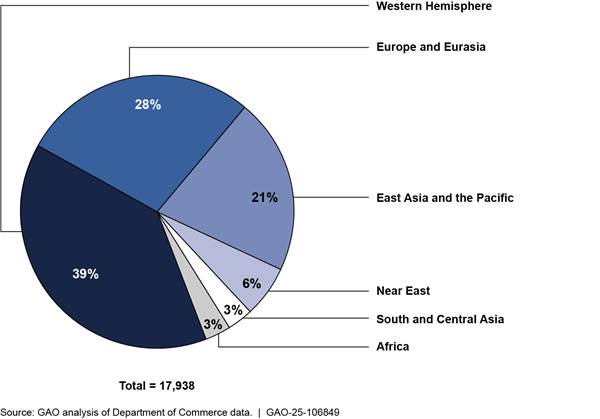

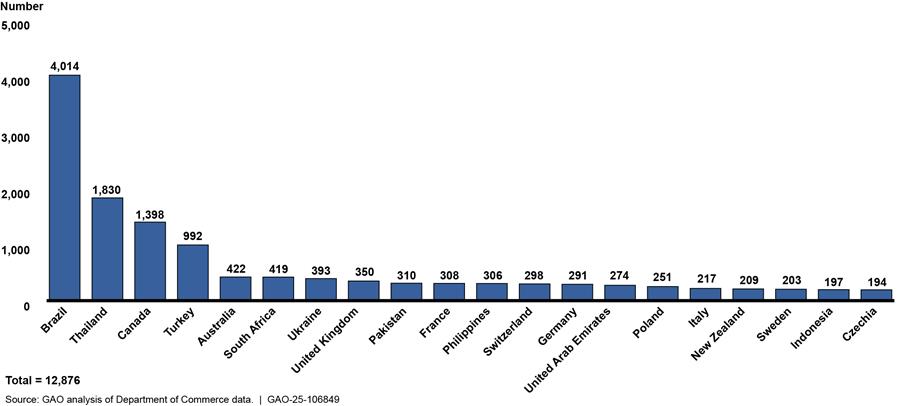

As of October 1, 2024, BIS has 11 ECO positions overseas, according to BIS officials (see fig. 6).[58] Each ECO has an assigned geographic area of responsibility in which they conduct end-use checks. In 2019, we reported that the Western Hemisphere and Africa were not covered by BIS’s ECO areas of responsibility.[59] As shown in figure 6, as of October 2024, most of the countries in the Western Hemisphere and Africa were still not covered.[60] Between fiscal years 2021–2023, countries in the Western Hemisphere and Africa collectively represented 42 percent of all export license applications approved for firearms (see app. II for more information). In addition, countries from these two regions included two of the top 10 destination countries for approved firearms export license applications during the same period.[61]

Figure 6: Locations of Department of Commerce Export Control Officer Positions and Areas of Responsibility, as of October 1, 2024

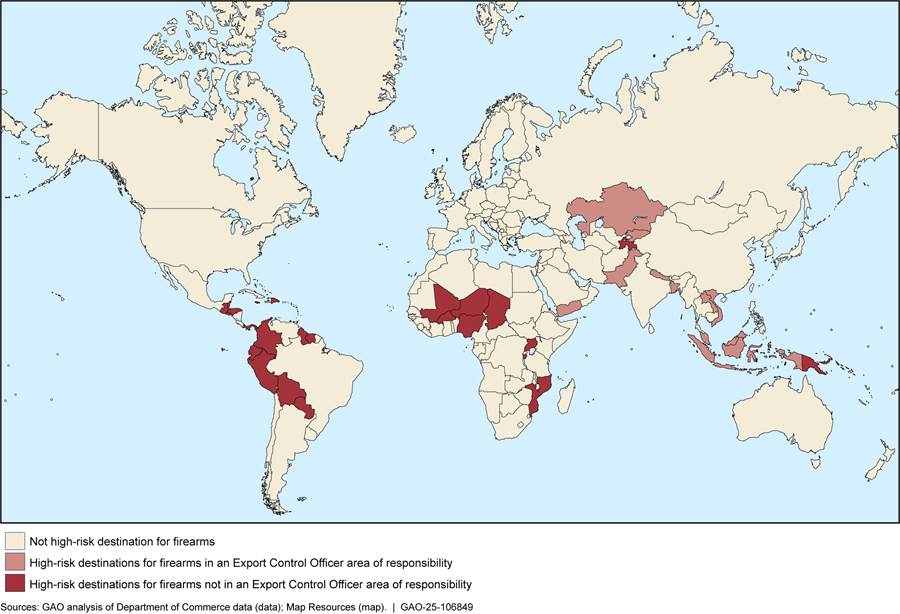

Of the 36 countries at high risk for firearms diversion or misuse, 24 (67 percent) are in the Western Hemisphere or Africa. Twenty-six of those 36 countries (72 percent) are not located in an ECO area of responsibility (see fig. 7). U.S. firearms exports to nongovernment end users in countries on State’s and BIS’s high-risk list present a substantial risk of being diverted or misused in a manner contrary to U.S. national security and foreign policy interests. Firearms diversion presents several risks, such as use in crimes and to foment regional instability. These risks were evidenced in 2023 when a U.S.-origin firearm, legally exported to Peru under a Commerce license, was used in the assassination of an Ecuadorian presidential candidate.

Figure 7: High-Risk Destinations for Firearms and Location within Export Control Officer Area of Responsibility

Note: Export license applications for firearms involving nongovernment end users in countries on the Department of Commerce’s “High-Risk Destinations for Firearms and Related Items” list are reviewed under a policy of presumption of denial. Additionally, applications involving U.S. arms–embargoed countries are reviewed under a policy of denial. Those countries are Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma, Cambodia, Central African Republic, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cuba, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Lebanon, Libya, Nicaragua, Russia, Somalia, Republic of South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe. See 22 C.F.R. 126.1 and 15 C.F.R. Part 740 Supplement No. 1 for specific regulatory requirements for U.S. arms–embargoed countries.

BIS officials told us the agency prefers for ECOs to conduct end-use checks because they are knowledgeable of export control laws and regulations and are more familiar with the countries in their respective areas of responsibility. For example, one ECO told us they were able to identify red flags on export transactions because they were familiar with the business practices and trade flows in the countries they cover. Additionally, BIS officials told us ECOs are the most familiar with the country-specific rules for conducting end-use checks in their respective areas of responsibilities, which can be complex in some regions.

When BIS wants to conduct an end-use check in a country not covered by an ECO, it uses BIS Special Agents and U.S. diplomatic personnel to conduct the check. From fiscal years 2021–2023, ECOs conducted about 55 percent of BIS end-use checks for firearms and related items; Special Agents conducted about 38 percent of checks, traveling under BIS’s Sentinel Program, discussed below;[62] and diplomatic personnel from ITA and State conducted the remaining 7 percent of checks. However, using non-ECO personnel has limitations:

· Sentinel Program. Under this program, trained BIS Special Agents are deployed as a team from the U.S. to countries to conduct end-use checks. The trips last for about 2 weeks at a time. These agents have criminal investigative experience and are knowledgeable of export laws and regulations, however, they are likely not familiar with the country or region where they are conducting the checks, according to BIS officials.

These agents also must coordinate travel and schedule end-use checks weeks in advance. As a result, BIS officials told us Sentinel teams typically do not perform prelicense checks, which need to be conducted within 14 days of being requested, generally limiting them to conducting postshipment verifications.[63] Moreover, BIS officials told us that Sentinel trips generally only occur between May and September, if and after BIS has received an annual appropriation and allocated enough money for the trips.[64]

· Diplomatic personnel. BIS officials told us that, if Sentinel teams or ECOs are not available, they request Foreign Commercial Service Officers from Commerce’s International Trade Administration or Foreign Service Officers from State to conduct the checks on BIS’s behalf. These officials are stationed in the region or country of the check and tend to be familiar with local practices. However, they generally do not have criminal investigative experience as is required for ECOs and Sentinel teams, according to BIS officials. BIS officials told us they try not to request end-use checks from diplomatic personnel because it is not a part of their normal responsibilities, and they may not have had experience with conducting end-use monitoring.

See table 4 for a summary of personnel that conduct end-use checks for BIS and potential limitations associated with each.

Table 4: Specialized Experience, General Duties, and Potential Limitations of Government Personnel That Conduct Firearms End-Use Checks for Bureau of Industry and Security

|

Agency |

Personnel title |

Specialized experience |

General dutiesa |

Potential limitationsa |

|

Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) |

Export Control Officer |

Law enforcement; often prior experience with BIS |

Conduct end-use checks; coordinate with foreign governments and businesses |

Coverage limited to certain geographic areas |

|

BIS |

Sentinel Team Special Agent |

Law enforcement within BIS |

Conduct end-use checks |

Limited regional expertise |

|

International Trade Administration |

Foreign Commercial Service Officer |

Trade analysis and promotion |

Promote U.S. commercial interests abroad |

No law enforcement experience |

|

Department of State |

Foreign Service Officer |

Variesb |

Promote U.S. interests abroad through diplomacy |

No law enforcement experience |

Source: GAO analysis of Departments of Commerce and State information. | GAO‑25‑106849

aGeneral duties and potential limitations are not exhaustive lists.

bForeign Service Officers are generalists who choose a career track, or functional specialization, that determines the type of work they do for the majority of their career. There are five career tracks: consular, economic, management, political, and public diplomacy. State does not require specific professional experience for acceptance to the Foreign Service.

Federal internal control standards state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to significant changes that could impact the internal control system.[65] They further state that changes in conditions affecting the entity and its environment—such as the 2020 transfer of jurisdiction from State to Commerce—often require changes to the entity’s internal control system, as existing controls may not be effective for meeting objectives or addressing risks under changed conditions. Management should analyze and respond to identified changes and related risks in order to maintain an effective internal control system.

In 2018, BIS officials told us that they both were anticipating a higher workload after the 2020 transfer and were very much aware of the risks for firearms and ammunitions trafficking and proliferation in Latin America. Despite that, BIS officials told us that Commerce did not request additional funding for ECO positions until its fiscal year 2025 budget request when it requested funding for two ECO positions in Central and South America. Further, Commerce did not request an ECO position for Africa. BIS has not assessed the number of ECO positions needed for global coverage or reallocated its current ECOs to provide such coverage.[66] In both 2018 and 2023, BIS officials told us BIS would continue to use Sentinel teams and diplomatic personnel in regions where it does not have ECO coverage.

BIS risks inconsistent end-use monitoring globally when it relies on personnel who either are not familiar with the regions where they are conducting end-use checks or do not have investigative backgrounds. That risk is heightened for end-use checks on firearms in regions at highest risk for diversion and misuse. For example, Sentinel Program Special Agents may appropriately apply investigative techniques when conducting a check but might miss important nuances that individuals familiar with the regional markets might understand. Conversely, diplomatic personnel may appropriately apply cultural competencies to the end-use check but might not be aware of how to apply useful investigative techniques. Without consistent and effective end-use monitoring in the Western Hemisphere and Africa, BIS does not have reasonable assurance that it is sufficiently mitigating the risks for diversion and misuse of firearms in those regions.

BIS Does Not Provide New-Hire Training Specific to Export Control Officers

ECOs are a small group of law enforcement officers that play a unique and critical role in monitoring compliance of transactions subject to Commerce’s regulations—the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). However, BIS officials told us BIS does not provide ECOs with formal training specific to their role before they start on the job.

According to BIS, ECOs serve as the agency’s overseas representatives, leveraging their law enforcement, commercial, and diplomatic skills to expand the U.S. government’s export compliance capabilities. For example, each year ECOs conduct hundreds of end-use checks on a wide range of controlled commodities, from semiconductors to firearms. ECOs also support other BIS activities, such as planning events to educate foreign companies on U.S. export controls and coordinating controls with host country governments.

ECOs can be hired from inside or outside of BIS, according to BIS officials.[67] ECOs must have criminal investigative experience or knowledge of the EAR. BIS ECOs told us these skills were critical to success in the role because ECOs are expected to perform from day one, such as by investigating transactions of commodities controlled by Commerce. As a result, BIS officials told us that ECOs are generally hired from a pool of internal applicants with law enforcement experience, such as BIS Special Agents. Applicants hired from this internal pool have also typically performed end-use monitoring during Sentinel Program trips, which BIS officials said provides them with the training necessary to conduct end-use checks.