DEFENSE INNOVATION UNIT

Actions Needed to Assess Progress and Further Enhance Collaboration

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-106856. For more information, contact W. William Russell at (202) 512-4841 or russellw@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106856, a report to congressional committees

Actions Needed to Assess Progress and Further Enhance Collaboration

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD established DIU to create new ways for it to acquire commercial technology to solve national security problems. Similar innovation entities also exist in DOD and the military services.

Two congressional reports include provisions for GAO to review DIU’s activities for effectiveness in fielding commercial technologies at scale, among other things. This report addresses (1) how DIU has transitioned commercial technologies for military use and the changes it is considering, (2) the extent to which DIU has established a performance management process to assess progress in meeting current and future goals, and (3) what opportunities exist to enhance DIU’s collaboration with other DOD innovation organizations to adopt commercial technologies.

To perform this review, GAO reviewed DOD and DIU documentation and data. GAO also selected six higher-dollar-value projects for review representing a mix of DIU technology areas and prototyping stages. We also interviewed DOD and DIU officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations to DOD, including that DIU establish performance goals and metrics for DIU 3.0; establish a process to collect, assess, and use performance information for DIU 3.0; and develop and implement a process to assess defense innovation community collaboration. DIU concurred with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense (DOD) aims to keep pace with foreign adversaries by quickly adopting commercial technologies. DOD leaders expressed concern that it is not doing so at the speed and scale needed. DOD created the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in 2015 to take on these long-standing challenges. In 2023 it announced changes (DIU 3.0) to increase its effectiveness.

DIU established a flexible award process to show that commercial technology can quickly deliver capabilities to the warfighter and is now shifting its focus under DIU 3.0 to address DOD’s most critical operational needs. From fiscal years 2016 through 2023, DIU made 450 awards to companies to develop prototypes. DIU reported that 51 percent of completed prototypes transitioned to production. With its new focus, DIU officials said they will use its established process to award prototype agreements that can deliver technologies at scale to meet DOD’s most critical needs. DIU will also increasingly work with military services and combatant commands.

DIU has limited ability to gauge progress toward addressing DOD’s most critical needs because it does not yet have a complete performance management process. Such a process defines goals and collects, assesses, and uses evidence to inform decisions. Specifically, DIU has not set performance goals and metrics to assess its progress toward achieving DIU 3.0’s strategic goal. Further, DIU officials have not identified which performance information to collect to inform their decisions for DIU 3.0. DIU officials plan to set goals in the future but did not specify when. As DIU attempts to address challenges in adopting commercial technologies within DOD for strategic effect, a robust data-based decision-making process can help DIU leadership know if it is making progress.

Opportunities also exist for DIU to enhance collaboration

with other DOD innovation organizations. The Defense Innovation

Community of Entities, a newly formed group of DOD innovation organizations, generally

incorporated six of GAO’s eight leading collaboration practices. But it has not

developed and documented how it will assess its progress in meeting its goal of

coordinating activities related to commercial technology adoption. Without assessing

collaboration, DIU will not know if the group is making progress toward its goal.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CSO |

commercial solutions opening |

|

DICE |

Defense Innovation Community of Entities |

|

DIU |

Defense Innovation Unit |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

NSIC |

National Security Innovation Capital |

|

NSIN |

National Security Innovation Network |

|

RDT&E |

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation |

|

TRL |

technology readiness level |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 27, 2025

Congressional Committees

Strategic competitors of the United States have greater access to commercial state-of-the-art technologies than ever before, and they can use these technologies to disrupt U.S. military primacy and threaten U.S. national security. To address these national security problems, the 2023 National Defense Science & Technology Strategy states that the Department of Defense (DOD) must establish new pathways to apply dual-use technologies—technologies that have both commercial and military applications. To do this, the strategy states that DOD must actively engage commercial companies to identify opportunities to leverage their technologies for military applications. Defense leaders have expressed concern that DOD is not adopting innovative commercial technologies at the speed and scale necessary to meet the needs of the warfighter.[1] According to defense experts, contributing factors to the slow rate of adoption include DOD’s limited understanding of emerging technologies, long timelines in the acquisition process, and difficulties in transitioning a commercial solution to DOD users for production and fielding.[2]

Over the years, DOD and Congress have taken steps to improve the department’s adoption of commercial technologies. In 2015, DOD established the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) to strengthen national security by quickly adopting commercial technology throughout the military. Most recently, in April 2023, DOD announced changes to DIU’s mission to both accelerate the adoption of commercial technology and also to scale it throughout the military to focus on the department’s most strategic problems. Scaling a technology refers to bringing the technology into full-rate production. In December 2023, Congress directed and the President signed into law that DIU is responsible for coordinating the activities of other DOD organizations on matters related to commercial technologies, dual use technologies, and the innovation of these technologies.[3]

The Senate Armed Services Committee Report accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to assess DIU’s effectiveness in meeting its mission to field and scale commercial technology across the military.[4] Also, the Conference Report accompanying the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 includes a provision for us to evaluate the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN)—a component of DIU.[5] This report (1) describes how DIU transitioned commercial technologies for military use and any changes DIU is considering when transitioning technologies; (2) examines the extent to which DIU has established a performance management process to assess its progress in meeting current and future goals; and (3) examines what opportunities exist to enhance DIU’s collaboration with other DOD innovation organizations to adopt commercial technologies for military use.

To describe DIU’s process for transitioning commercial technologies and any forthcoming changes, we reviewed DIU documentation, including guidance pertaining to DIU’s commercial solutions opening (CSO) process. We interviewed senior DIU officials, including DIU technology portfolio directors, regarding DIU’s processes for awarding and executing prototype agreements and how DIU supports the transition from prototype to production. We analyzed DIU-provided data about protype agreements awarded between fiscal years 2016 through 2023 to describe the number of prototype agreements awarded for DIU projects and the associated obligations. We also reviewed DIU-provided information on the number of agreements that transitioned to production for procurement and fielding. Based on these data, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of six projects for further review. We selected projects from each of DIU’s six technology portfolios. We also selected projects at different stages in the prototyping process and that were generally of higher obligation values. We reviewed selected pre-award and agreement documentation for the six projects. We also interviewed selected end users of the projects to understand their experience in working with DIU.

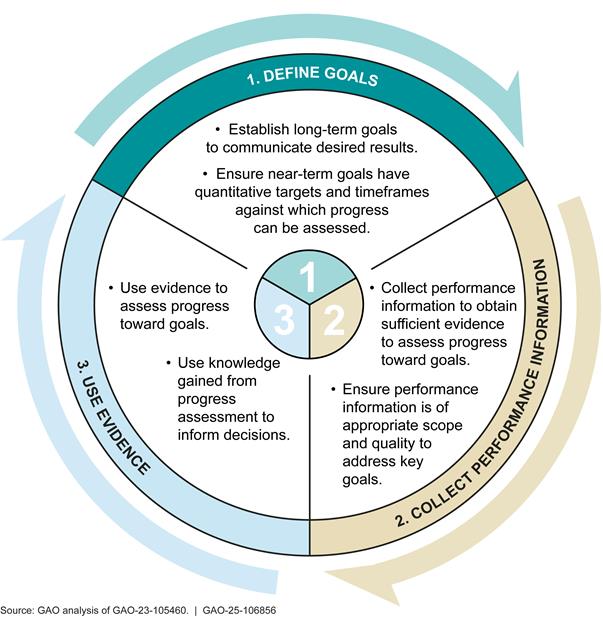

To determine the extent to which DIU has established a performance management process to assess its progress in meeting current and future goals, we reviewed DIU’s August 2023 memorandum outlining its plans to refocus its efforts on the department’s most critical needs along with the accompanying implementation milestones. We requested and reviewed DIU plans and collected information to identify DIU’s current and future goals. We also interviewed senior DIU officials about the extent to which they had developed goals for DIU’s previous focus and for its transition to focus more on meeting DOD’s critical needs. We compared DIU’s efforts to establish goals against GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking, which details the elements of a performance management process.[6] At its core, a performance management process helps organizations (1) define goals to communicate the results an organization wants to achieve, (2) collect related information to assess progress, and (3) use that information to determine how well they are performing and identify opportunities to improve results. Where DIU established performance goals with quantitative targets and timeframes, we analyzed DIU prototype award data to assess the extent to which DIU met these goals.

To examine what opportunities exist to enhance DIU’s collaboration with other DOD innovation organizations, we reviewed DOD documentation about various working groups as well as the Defense Innovation Community of Entities (DICE)—including meeting notes, organizational chart of working groups, and memorandum. We also reviewed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 and the explanatory statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024 about statutory changes and congressional statements related to DIU and DICE.[7] We interviewed DIU officials and officials from selected DOD innovation organizations who are members of DICE—including the Army Applications Laboratory, Navy’s NavalX, Air Force’s AFWERX, Marine Innovation Unit, and Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory—about their collaboration in DICE as well as officials from the service agencies that oversee the selected innovation organizations.

We compared information from the documentation review and agency interviews to the GAO’s eight leading practices for interagency collaboration to determine the extent to which DICE incorporated the practices.[8] We did not compare other working groups—the Deputy’s Innovation Steering Group and its supporting entity known as the Defense Innovation Working Group—to the leading practices for interagency collaboration because these groups are beyond the scope of this review.

For additional information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The Secretary of Defense established DIU—then known as the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental, or DIUx—in April 2015, initially to further DOD’s outreach to innovative technology companies in the commercial sector. At that time, defense leaders recognized that DOD needed innovative technologies to maintain an advantage against strategic competitors—and that these innovations increasingly came from commercial markets, particularly the technology start-up culture of Silicon Valley. DIU was headquartered in Mountain View, California, to better coordinate with these companies. This initial phase, which focused on building defense and industry connections, would later be referred to as DIU 1.0.

The following year, in May 2016, the Defense Secretary announced plans to refocus DIU, which was termed as DIU 2.0. This included enhancements through which DIU could more quickly explore and demonstrate the use of advanced commercial technologies to meet DOD needs. To do this, DIU introduced an acquisition mechanism known as the commercial solutions opening (CSO) process, intended to make acquisitions faster and more in line with commercial practices. DIU’s CSO process results in awards that leverage DOD’s authorities to use other transaction agreements to develop prototypes. Other transaction agreements are generally exempt from federal procurement regulations and related oversight mechanisms.[9]

As we reported in July 2017 and September 2022, this flexibility is intended in part to help DOD work with nontraditional contractors, which can include commercial companies, by reducing perceived burdens—such as the time to award or need for government-unique cost accounting systems—that make DOD an unattractive customer for these companies.[10] Furthermore, if the company’s prototyping effort is deemed successful, DOD can opt to award a follow-on contract or agreement for production without using competitive procedures, if competitive procedures were used for the prototype award.[11]

DIU Announces DIU 3.0

In August 2023, DIU announced plans—known as DIU 3.0—to refocus its efforts on transitioning commercial technology to military use at both speed and scale to solve DOD’s most critical operational capability gaps. DIU explained that while its prototyping activities under DIU 2.0 showed that commercial technologies could solve DOD problems, further change was urgently needed to provide the levels of capability called for in the 2022 National Defense Strategy. Specifically, DIU said that the activities it conducted under DIU 2.0 had a limited effect, in part because of systemic challenges that DOD faces in scaling technologies and because DIU was not well positioned to solve these challenges.

Under DIU 3.0, DIU plans to work more closely with DOD—including the DOD’s and the military services’ leadership, combatant commands, and the Joint Staff—to better solve systematic challenges by scaling commercial technologies. For example, officials report that in 2024 DIU assigned staff to work within combatant commands and coordinate with the military services and DOD to quickly relay warfighter needs. Staff are also working to ensure capabilities are integrated into operational plans and supporting policies.

Similarly, DIU is directly involved in supporting DOD’s Replicator Initiative, which was launched in August 2023 to accelerate the delivery of innovative capabilities to the warfighter at speed and scale to solve an operational challenge in 24 months.[12] Replicator is led by the Deputy’s Innovation Steering Group, for which DIU serves as the Executive Secretary and as a member. DIU also chairs the Defense Innovation Working Group, which is charged with implementing the initiative. As part of Replicator, DIU and the Defense Innovation Working Group members intend to create a process that can be repeated—within DOD and the services—to deliver commercial technologies to the warfighter at speed and scale.

To implement DIU 3.0, DIU identified activities across multiple lines of effort needed to achieve its goals. DIU has developed plans to incrementally execute the initiatives associated with each line of effort over a 3-year period starting in August 2023.

Additional Changes to DIU

Related to DIU 3.0, DIU announced additional changes that affect its organizational structures in 2023. Congress and DOD likewise also made changes affecting DIU’s organizational structure, funding levels to support its new mission, and coordination with other DOD organizations.

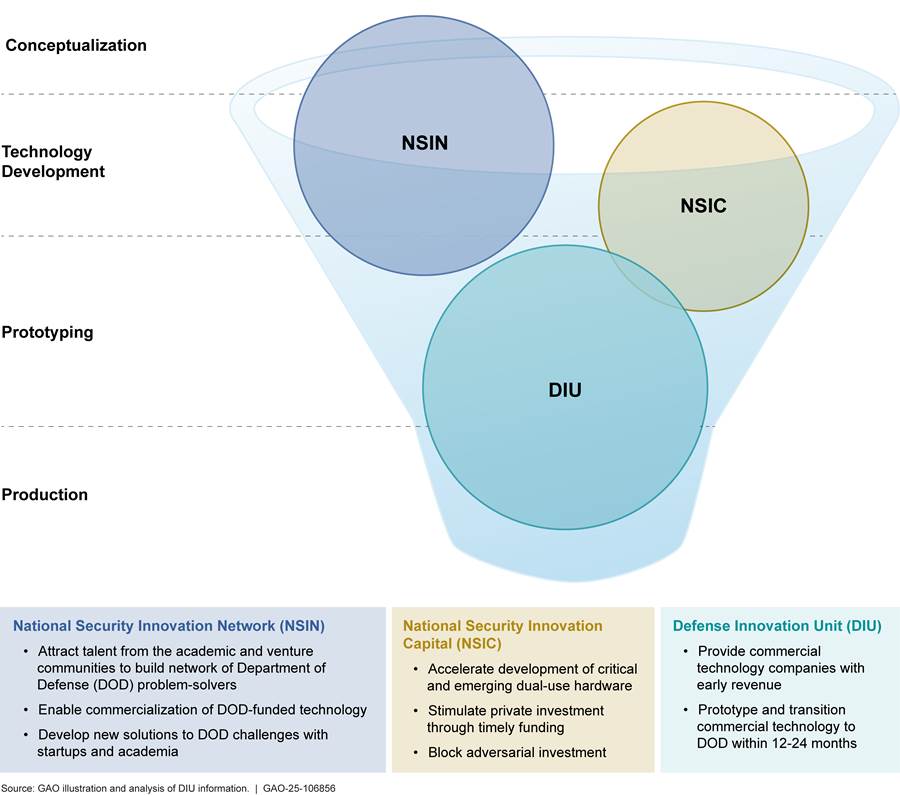

· Integrating NSIN and NSIC. In August 2023, DIU’s 3.0 implementation plan stated that two organizations—the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN) and National Security Innovation Capital (NSIC)—would be integrated into DIU by February 2024. DIU said this reorganization would reduce duplication and maximize support for DIU’s new focus under 3.0. NSIN aims to build connections between academia, technology start-up companies, and defense organizations to provide innovative solutions to national security problems. NSIC provides resources to domestic start-up companies that produce hardware technologies in critical areas that can be used for both military and commercial applications. DIU officials stated that the private sector has not invested in the production of these types of early-stage hardware. The funding provided by NSIC is intended to accelerate companies’ progress in developing minimally viable products that can be tested or fielded to meet military needs. Previously, officials said that DIU oversaw some aspects of both NSIN and NSIC, such as administrative functions, but NSIN operated as a separate entity outside of DIU until July 2023, while NSIC operated as a separate entity within DIU.

· Increasing DIU funding. DIU and its components reported receiving more than $983 million in fiscal year 2024 funding to support its prototyping, fielding, and other activities—a 431 percent increase from the prior year.[13] A large portion of this increase came from approximately $589 million in funding above the requested amount to support DIU fielding efforts. The explanatory statement to the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2024 directed the DIU Director as well as the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the service secretaries to report on efforts to ensure fielding innovation activities are adequately resourced and coordinated across relevant organizations. Table 1 provides additional details about DIU’s research, development, test and evaluation funding from fiscal years 2022 through 2024.

Table 1: Reported Defense Innovation Unit Available Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) Funding for Fiscal Years (FY) 2022 through 2024

|

Dollars in thousands |

|

|

|

|

Budget line item |

FY2022 RDT&E fundinga |

FY2023 RDT&E fundinga |

FY2024 available RDT&E fundinga |

|

Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) |

36,531 |

67,646 |

225,229 |

|

DIU Prototyping (includes NSIC)b |

15,585 |

40,368 |

131,874 |

|

DIU Fieldingc |

N/A |

N/A |

589,400 |

|

National Security Innovation Network (NSIN) |

34,867 |

77,032 |

21,575 |

|

National Security Innovation Capital (NSIC)b |

N/A |

N/A |

15,085 |

|

Total |

86,983 |

185,046 |

983,163 |

N/A = not applicable

Source: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) quarterly financial reports. | GAO‑25‑106856

aThese amounts are net of any adjustments—such as transfers, reprogrammings, and other statutory and non-statutory adjustments—made after the funding was first appropriated by Congress. The FY2022 and FY2023 RDT&E funding refers to the amounts that were available to DIU until September 30, 2023, and September 30, 2024, respectively. These funds are now expired, meaning they are no longer available for new obligations. The FY2024 available RDT&E funding refers to the amounts that are currently available to DIU as of December 31, 2024.

bIn FY2024, project-level activities in the DIU Prototyping budget line item were transferred to the DIU budget line item and newly created NSIC budget line item to better align funding to the mission. Prior to FY2024, the DIU Prototyping budget line item provided project-level funding for NSIC efforts.

cDIU Fielding budget line item was created by Congress in FY2024 to support expenses related to development, test and evaluation, procurement, production modification, and other uses. It also supports combatant commands and the Defense Innovation Community of Entities.

· Making DIU responsible for coordination efforts. In December 2023, Congress directed and the President signed into law that the DIU Director assume a new role as a principal staff assistant, who reports directly to the Secretary of Defense on the development and adoption of commercial technologies to transform military capabilities.[14] Prior to that, since 2018, the DIU director had reported to the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. DIU is now DOD’s focal point for commercial technologies. DIU is responsible for coordinating the activities of other DOD organizations on matters related to commercial technologies, dual use technologies, and the innovation of these technologies. To further these efforts, DIU has also joined other DOD governance bodies focused on management, budget, and requirements, as well as the previously mentioned Defense Innovation Steering Group and Defense Innovation Working Group.

· Creating the Defense Innovation Community of Entities (DICE). In December 2023, DIU formed DICE—a group composed of innovation organizations from across DOD and the military services—in part to carry out its newly established responsibilities for coordinating innovation efforts related to commercial technologies. Additionally, DICE was created to capture best practices and address systemic barriers to innovation.

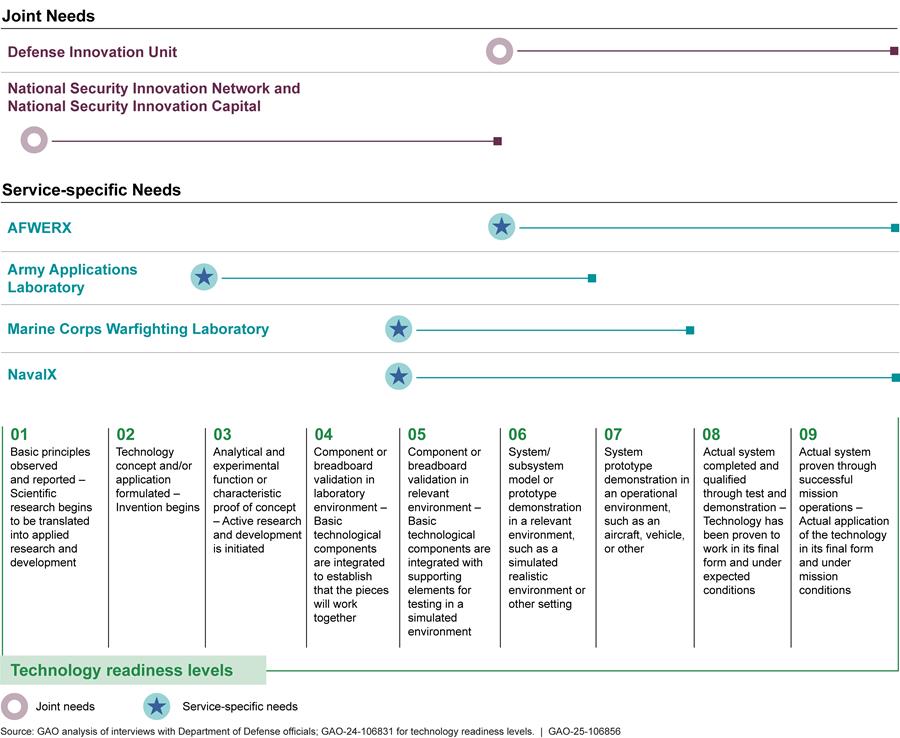

During the course of DIU 2.0, many innovation organizations in DOD were established to support the adoption of commercial technology, particularly within the services. Like DIU, some of these organizations have a similar mission to quickly adopt commercial technologies to address their service’s capability needs. These organizations include the Army Applications Laboratory, AFWERX, and NavalX. However, unlike DIU 3.0, their missions have not focused on scaling the commercial technologies. Some other innovation organizations—such as the Marine Innovation Unit and Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory—do not focus specifically on commercial technology, but instead view it as one of many tools to address their needs. DIU and selected services’ innovation organizations distinguish their commercial technology projects from each other by focusing on different levels of technology maturity as measured by technology readiness levels, and whether they address service-specific or joint needs (see fig. 1).[15] Appendix II further describes DOD’s technology readiness levels.

Figure 1: Selected Department of Defense Organizations Working to Adopt Commercial Technologies Based on Technology Readiness Levels and Type of Need

Note: Some Department of Defense innovation organizations addressing service-specific needs include Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs. We did not include these programs when depicting the service organization’s technology readiness levels in the graphic. See 15 U.S.C. 638 for more information about the small business programs.

DIU Plans to Focus Its Prototype Award Process on Transition Projects That Address DOD’s Most Critical Needs

DIU 2.0 Used a Flexible Prototype Process and Staff Expertise

DIU developed the CSO process to quickly make competitive awards—primarily to nontraditional companies or small businesses—to prototype the use of a commercial technology that responds to a stated need of DOD. For example, one of DIU’s first projects met DOD’s need for a small commercial drone that could operate autonomously to detect threats in tight spaces, including indoors. Specifically, DIU designed the CSO process to streamline the steps needed to solicit, evaluate, and award agreements to companies, making the process more in line with commercial practices familiar to nontraditional vendors. Instead of responding to a government solicitation with a lengthy proposal, a company responds to a CSO solicitation with a short paper or slide deck—typically no more than five pages or 15 slides—that proposes a solution to a stated DOD problem. The three phases of the CSO process are one of the stages in DIU’s broader life-cycle prototype process, as described in table 2.

|

Stage |

Stage description |

Expected time frames |

|

Problem curation and due diligence |

Receive, understand, evaluate Department of Defense (DOD) partner problem Confirm commercial market exists to address problem |

Not specified |

|

Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO) |

Phase 1. Solicit proposals in response to a problem statement Phase 2. Evaluate proposals and invite selected offerors to pitch their solutions Phase 3. Evaluate pitches, request proposals from successful vendors, and conduct negotiations and award agreements |

Phase 1: Approximately 10 days Phases 2 and 3: 60-90 days |

|

Prototype execution |

Execute prototype projects in accordance with agreement |

12-24 months |

|

Transition |

DOD has the option to transition successful prototypes for fielding and production |

Not specified |

Source: GAO analysis of Defense Innovation Unit information. | GAO‑25‑106856

DIU officials, DOD partners, and industry representatives identified several aspects of the CSO process that provided value, many of which rely on DIU staff’s experience and industry knowledge and outreach, as well as and the flexibilities of the CSO. According to DIU officials, its workforce generally combines experience in defense, often through military service, and the industries that produce cutting-edge commercial technologies. DIU refers to this as “dual-fluency” that allows them to communicate effectively with these sectors.

Regular interaction between DIU, DOD, and industry is a key aspect throughout the stages of the CSO process. As part of the process, DIU works to clarify the DOD partner’s core needs and determine the feasibility of meeting those needs through commercial technology during the problem curation stage. DIU then refines how these needs are presented to industry, developing a broadly written statement of the problem to be solved to solicit proposals. For example, in one of the six projects we reviewed—called Harmonious Rook—the U.S. Air Force and other government partners wanted to explore options to use commercial data to identify disruptions in global positioning systems. DIU worked with the partners to explore the problem and the commercial options. DIU officials said that they also worked closely with industry and determined that several commercial geospatial data analytics firms—many of which had not previously worked with the government—could respond to their need. Table 3 includes information on the six projects we reviewed.

|

Prototype project reviewed |

DIU portfolio(s) |

Obligations through fiscal year 2023 |

Project summary |

Status as of November 2024 |

|

Harmonious Rook |

Artificial Intelligence/ Machine Learning and Space |

$8.3 |

A proof of concept to evaluate the feasibility of using commercially derived sources to inform of intentional disruptions to the space-based position, navigation, and timing capabilities |

All four prototype agreements awarded are expected to complete performance by November 2024 According to officials, three of the four prototypes are active and providing data products that support operations in multiple organizations |

|

Hybrid Space Architecture |

Space |

$26.0 |

Demonstrate a flexible and secure architecture to communicate across disparate government and commercial networks by Integrating emerging sensor and communications capabilities |

All nine prototype agreements awarded as of September 2023 were expected to complete performance by September 2024 |

|

Small Class Unmanned Undersea Vehicle |

Autonomy |

$16.9 |

Prototype a replacement to Navy’s existing small class unmanned undersea vehicle to detect, classify, localize, and identify objects on the ocean floor. Prototype to include flexible platform configuration and encryption |

Both prototypes completed performance in 2019 One prototype transitioned to a Navy production contract in 2023 |

|

Cyber Threat Telemetry |

Cyber |

$3.4 |

Use commercial data, including non-traditional sources, to improve situational awareness of threat activity and understand the attributes of malicious cyber activities |

All prototype agreements completed performance by early 2023 Three of the four prototypes transitioned to U.S. Cyber Command production awards by September 2024 |

|

Real-Time Information and Effects |

Human Systems |

$51.3 |

Integrated software and hardware tools to use existing open-source data to support the tactical warfighter, particularly for targeting activities in real time |

The prototype agreement completed performance in 2023 In November 2024, DIU reported that a production agreement was awarded |

|

Blended Wing Body |

Energy |

$52.2 |

Conceptual design of advanced aircraft configuration with up to 30 percent improved efficiency to improve operational capabilities |

Both prototype agreements completed performance by 2024 One prototype effort transitioned to an Air Force contract for further prototyping |

Source: GAO analysis of DIU information. | GAO‑25‑106856

Among the six projects, the DIU staff’s experience and outreach to industry also helped to bring more companies into the CSO process. For example, for the Hybrid Space Architecture project, which DIU officials described as a resilient internet-in-space, officials said they worked with industry for years to explore the options for using commercial technology to solve this complex problem. DIU ultimately received 132 proposals offering solutions in the first phase of the CSO process, which resulted in nine agreements as of the end of fiscal year 2023. Further, in Harmonious Rook, which involves artificial intelligence and machine learning technology, the DOD partner said there have been so many changes in that particular industry that it would have been difficult for them to assess the market and select the right vendor without DIU’s industry expertise. Industry representatives we spoke to also said that DIU’s regular interactions with industry were appreciated and bolster DIU’s reputation with both the companies and their investors.

DIU officials and DOD partners also cited the benefits of flexibilities in the CSO process when awarding agreements and executing the prototypes. In particular, officials said the CSO process is not as driven by defined requirements as traditional acquisitions. Instead, DIU and the DOD partner can select an approach based on the options in the proposed solutions they receive. This may result in awarding multiple agreements to explore different approaches or meet differing needs through the prototyping phase. For example, three of the agreements DIU awarded for the Harmonious Rook project are for different prototypes intended to meet the varying focus areas of separate customers. Similarly, for the Hybrid Space Architecture project, DIU officials said that because they did not have pre-determined requirements, they could learn from the technology options offered by the vendors, particularly as the commercial technology is further ahead than where it is within DOD. DIU can also adjust the number of awards it makes. Officials explained that they were initially able to fund only eight awards for Hybrid Space Architecture, but the CSO flexibilities allowed them to make additional awards as the prototyping phase went on, to best meet newly identified needs.

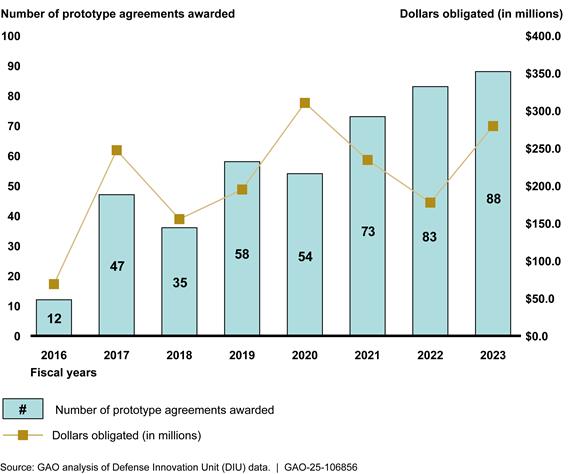

DIU Transitioned 62 Prototype Agreements to Production Awards under DIU 2.0

From fiscal years 2016 through 2023, the period covered almost entirely by DIU 2.0, DIU awarded 450 prototype agreements for projects that respond to identified problems or needs. DIU reports that it has successfully transitioned 62 prototype agreements to production awards or contracts, or about half of those projects (51 percent) with at least one completed prototype agreement. According to DIU’s data, the prototype awards had combined obligations of approximately $1.7 billion, as shown in figure 2. DIU also reported that the combined ceiling value of the transition projects is more than $5.5 billion.

Note: The total dollars obligated for each fiscal year are the combined DIU and partner obligations reported for all agreements awarded during that fiscal year.

The vast majority of obligations for DIU’s prototype agreements—more than 90 percent—were made by the entities that partner with DIU. DIU obligated the remaining funds. However, the extent of DIU’s obligations varied by agreement, even for agreements within the same project. For example, the Air Force provided all $52.2 million obligated for the two agreements awarded for the Blended Wing Body project. In contrast, for the Harmonious Rook project, DIU obligated $2.1 million on one agreement—or almost 65 percent the obligations—but only $0.6 million—or almost 15 percent—of another agreement. DIU officials explained that they considered multiple factors in determining where best to apply DIU’s limited funds under DIU 2.0. In this case, timing was a factor as the award was for a critical need. However, one of the partners did not have funding immediately available, so DIU used its funds to bridge the gap.

DIU officials explained that a roughly 50 percent transition rate represented a reasonable amount of risk for the CSO process under DIU 2.0, as there are multiple reasons why a project may not transition. For example, officials noted that a prototype may work but the program office may experience difficulties securing long-term funding. In addition, the timing for when successful prototypes transition to production may vary. For one project we reviewed, the Navy’s Small Class Unmanned Undersea Vehicle, two prototype awards were successfully completed in 2019. By the end of fiscal year 2023, one prototype had transitioned to a production contract with the Navy, while the other remains available to transition in the future.

In moving to DIU 3.0, DIU officials said that they will build off lessons learned during the course of DIU 2.0, including focusing on the potential transition partner earlier in the CSO process. In the six projects we reviewed, which were started under DIU 2.0, five projects included pre-award documents that identify a potential transition path for the effort. These documents generally refer to the role of the potential transition partner, including the extent to which they are positioned to support production efforts, as well as the possibility of future funds being available for such efforts. For example, documents for the Cyber Threat Telemetry project awarded in 2021 noted that the partner—U.S. Cyber Command—was prepared to fund the prototype and the project transition, and that the expected solution would align with previous transition efforts. Similarly, in the Real-Time Information and Effects project, DIU considered the project’s transition potential prior to taking on the project and decided to move forward because the DOD partner had programmed future budget dollars for a transition award.

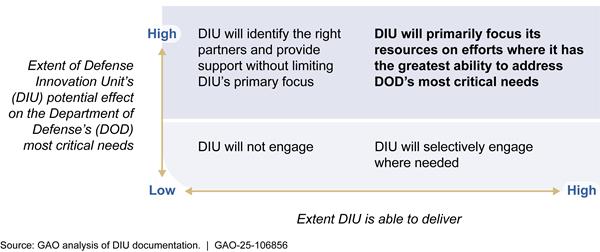

DIU 3.0 Plans Changes to Meet DOD’s Most Critical Needs

In announcing the need for DIU 3.0, DIU stated that it intends to apply and extend its existing capabilities to focus on transitioning technology solutions that have the greatest effect on DOD’s most strategic challenges. To do this, DIU officials said they will continue using the CSO process but focus on undertaking prototype projects capable of scaling to meet the most critical DOD and national security needs. As part of this focus, DIU plans for DOD’s innovation organizations, including those within the services, to have a larger role in carrying out projects that DIU does not deem to be strategic. Figure 3 illustrates DIU 3.0’s planned changes.

DIU officials said that these efforts were already underway to some extent during the later stages of DIU 2.0, as DIU increasingly considered projects’ potential for strategic effect when deciding whether or not to support them. As one DIU portfolio director explained, DIU did not take on projects that it might have previously accepted to focus on issues considered to be the most pressing and of larger scope, such as operational problems affecting multiple services. For example, in documenting the reasons to take on the Blended Wing Body project, DIU noted the effort would potentially advance the development of an aeronautic design with potential to significantly increase energy efficiency and improve operations in areas with contested fuel logistics. Further, while the project is funded by the Air Force, the issue is of interest to DOD and NASA.

According to officials, DIU will continue to use its CSO process to award prototype agreements under DIU 3.0. For example, DIU used the CSO to support an initial effort of DOD’s Replicator Initiative by issuing a request for companies to offer potential solutions to scale small uncrewed surface vessels in January 2024. Through the CSO, DIU awarded an unspecified number of agreements by August 2024. DIU also plans to increasingly connect its staff with potential DOD partners and end users to understand their requirements. For example, DIU is embedding more staff in selected combatant commands and the services to enable a more direct connection as they define requirements, to consider where commercial technology can be leveraged. According to DIU officials, increasing coordination with senior service leaders also helps DIU better understand and respond to their priority needs. Senior DOD leaders acknowledge the benefit of having DIU staff working in close proximity on such efforts.

DIU Has Limited Ability to Assess Progress in Solving DOD’s Most Critical Operational Gaps

DIU does not yet have clear insight into whether it is making progress to achieve its 3.0 strategic goal of helping DOD solve its most critical operational gaps. This is because DIU does not have a complete performance management process to assess its results. In addition, DIU has not yet aligned the goals of NSIN and NSIC—DIU’s two new components—with the strategic goal for DIU 3.0.

DIU’s Incomplete Performance Management Process Hinders Its Ability to Assess Progress

DIU does not know if it is making progress toward achieving the strategic goal of DIU 3.0 because it has not yet established a performance management process for DIU 3.0. Our prior work has found that it is important for federal organizations to assess their performance by implementing a performance management process.[16] At its core, a performance management process helps organizations (1) define goals to communicate the results an organization wants to achieve, (2) collect evidence related to those efforts, and (3) use evidence to learn and inform decision-making as shown in figure 4.

· Defining measurable performance goals. Establishing goals early is important because they identify the results that organizations want to achieve. Goals also anchor the performance management process by determining what types of information officials should collect to assess results and how they will use that information to make decisions about the future direction of their organizations. Typically, organizations start by developing strategic goals—or the long-term outcomes—for their activities. To ensure progress can be assessed, each strategic goal is broken into performance goals—or near-term goals that have quantitative targets and timeframes against which performance can be measured.

Prior to August 2023, DIU focused on achieving DIU 2.0’s strategic goal of rapidly prototyping commercial technologies to solve defense innovation problems but established incomplete performance goals. For example, it established five such goals under DIU 2.0, but three lacked quantitative targets and time frames that allow for performance assessment as shown in table 4 below.

Table 4: GAO Analysis of Whether Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) 2.0 Strategic and Performance Goals Included Targets and Time Frames

|

DIU 2.0 strategic goal |

DIU 2.0 performance goals |

Measurable targets and time frames? |

Analysis |

|

Prove that defense innovation problems can be solved with commercial technology and be prototyped quickly. |

Award a prototype other transaction agreement within 60-90 days of receiving a company proposal for a warfighter solution |

Yes |

60-90 days is a quantitative target that DIU can measure to determine whether it is meeting this goal. |

|

Complete a prototype project within 12-24 months |

Yes |

12-24 months is a quantitative target that DIU can measure to determine whether it is meeting this goal. |

|

|

Total funds obligated by Department of Defense (DOD) partner and the number of DOD partners on a project |

No |

DIU can calculate the total funds obligated by DOD partners and count the number of DOD partners on a project, but without a specified target for both, DIU cannot determine whether it is meeting this goal. |

|

|

Open solicitation and submission process measured by the number of submissions and agreements with nontraditional, small-businesses, and first-time DOD vendors |

No |

DIU counts the number of agreements with nontraditional, small businesses, and first-time DOD vendors but without a target for how many should receive awards over a specific time frame, DIU cannot determine whether it is meeting this goal. |

|

|

Transition capabilities to the warfighter |

No |

DIU counts the number of capabilities transitioned to the warfighter and set target percentages in some years, but not in others. Without consistently specifying a target percentage or the number of capabilities that should be transferred, DIU cannot determine whether it is meeting this goal. |

Source: GAO analysis of DIU data. | GAO‑25‑106856

The lack of quantitative targets and time frames for some of DIU’s previous performance goals indicates that those goals did not sufficiently break down DIU 2.0’s strategic goal into measurable near-term results. For example, under DIU 2.0, DIU could not determine whether the number of capabilities transitioned to the warfighter was sufficient because it did not consistently establish a quantitative target for this goal. As a result of having incomplete performance goals, DIU had limited ability to assess progress in meeting the strategic goal for DIU 2.0.

In August 2023, DIU initiated DIU 3.0, which revised its strategic goal to leveraging commercial technology and innovation to meet DOD’s most critical operational gaps. As part of its plan to implement DIU 3.0, DIU recognized the need to develop new goals with associated performance measures to assess its strategic results. DIU aimed to do this by February 2024. However, in September 2024, DIU officials told us that they had not yet established measurable performance goals for DIU 3.0. Officials said that they planned to convert milestones detailed in the DIU 3.0 implementation plan into performance measures. Officials also said that future performance measures would likely include quantitative measures, such as the number of capabilities that transitioned into fielding plans. But DIU officials did not specify when they plan to complete this effort, stating that their current focus is on executing the DIU 3.0 strategy and budget. Establishing measurable performance goals for DIU 3.0 would provide DIU with an effective method to fully assess its progress toward achieving its strategic goal.

· Collecting performance information. Because DIU officials told us they have not identified measurable performance goals for DIU 3.0, DIU has not determined which performance information to collect. Our past work describes performance information as a form of evidence that officials gather to assess, understand, and identify opportunities to improve results as part of an effective performance management process.[17] To that end, organizations ensure that they collect information that covers relevant goals and is of sufficient quality. According to the DIU 3.0 implementation plan, DIU planned to establish a means of tracking the newly established performance measures by August 2024, so that DIU could use this information to assess progress made under DIU 3.0. In doing so, DIU recognized potential data limitations and acknowledged the need for additional quantitative and qualitative assessments of DIU 3.0’s results.

While DIU officials told us they plan to establish new performance measures, they also anticipate continuing to use some DIU 2.0 measures, such as the number of technologies that transition to the warfighter. According to DIU officials, this is an important measure for industry because it shows opportunities available for working with DOD. Collecting performance information linked to performance measures, like the number of commercial capabilities transitioned to the warfighter, is important to ensure that DIU decision-makers and stakeholders, including Congress, have sufficient evidence to assess progress toward achieving DIU 3.0’s goals.

· Using performance information. Assessing DIU’s performance is important to inform decisions about whether its goals need to be modified and where additional actions may be needed to make further progress such as redirecting resources, including staff. DIU officials said that under DIU 2.0, they assessed DIU’s performance in cases where the performance goals included targets and time frames, and considered whether those metrics were still applicable. Specifically, DIU assessed data on the number of days it takes to award prototype agreements, with the goal of making an award in 60 to 90 days. Our analysis of DIU prototype agreements awarded from fiscal years 2016 through 2023 indicates that 85 percent of DIU’s awards exceeded the 90-day goal, averaging about 172 days. DIU officials said they used performance data to analyze the root causes for missing this goal in fiscal year 2023 and considered actions they could take, including changing DIU’s performance measures. Ultimately, DIU officials said they reaffirmed their commitment to the 60- to 90-day award target but recognized it as an ideal target rather than an achievable goal in the near term. Although DIU officials used performance information to understand the causes behind missing one of their performance goals, they did not use that information to make that goal more achievable.

Our prior work has found that using performance information is the final step of a complete performance management process.[18] Using this information allows for learning which occurs when officials assess whether DIU’s goals were met or not, and why. That assessment then can inform a range of decisions such as changes to existing strategies to achieve better results. While DIU took some steps to assess the performance information it collected under DIU 2.0, DIU has not identified which performance information to collect, assess, and use for DIU 3.0, because officials stated that it has not established performance goals with performance measures for DIU 3.0. By collecting, assessing, and leveraging performance information associated with key performance measures, DIU will be better positioned to assess progress toward achieving DIU 3.0’s strategic goal and make informed decisions to ensure DIU meets it.

DIU Has Not Aligned Two Components’ Goals with DIU’s Strategic Goal

The DIU 3.0 plan called for DIU to integrate NSIN and NSIC into DIU by February 2024, but DIU officials have not yet confirmed that these components’ goals align with DIU 3.0’s strategic goal as of September 2024. NSIN and NSIC are components of DIU, and their leaders report to the Director of DIU, but each component has its own goals. Specifically, NSIN builds networks of innovators that generate new solutions to national security problems, and NSIC accelerates the development of dual-use hardware technology. DIU officials told us that these components have a complementary relationship with DIU in which NSIN expands participation in the national security innovation base; NSIC supports evolving technology; and DIU scales and transitions mature technology, as shown in figure 5.

DIU has not demonstrated that the goals of these components align with the strategic goal of DIU 3.0, but we found some of NSIN’s and NSIC’s activities support DIU 3.0’s strategic goal. For example, the 2023 NSIN Implementation Plan states that one of NSIN’s missions is to support venture companies that develop dual-use technologies to address DOD capability gaps and that NSIN’s integration into DIU will help maximize the strategic impact of DIU. Similarly, NSIC provides funding to early-stage companies developing hardware technologies in the autonomy and space fields, two of the portfolios from which DIU is adopting and prototyping mature commercial technologies. This funding allows these companies not only to sustain their businesses, but also to mature their technologies to a level where they can attract greater levels of private sector funding. Additionally, NSIC funding prevents U.S. adversaries from investing in these companies and obtaining their technologies.

DIU officials told us NSIN and NSIC’s financial management, human resources, and other contracting activities have all been centralized within DIU. Additionally, DIU, NSIN, and NSIC are sharing more information and making more connections. To that end, the three components have meetings to discuss who is responsible for pursuing a specific technology to ensure they are not duplicating their efforts to support the same technology. In September 2024, DIU officials told us that they were rolling out a new strategy for how DIU, NSIN, and NSIC should work together. Subsequently, DIU officials said that they established an integrated commercial operations team in October 2024 that incorporates both NSIN and NSIC and supports the strategic goal of DIU 3.0. However, DIU has not provided further detail on how NSIN’s and NSIC’s goals will align with DIU’s 3.0’s strategic goal. Without aligning NSIN’s and NSIC’s strategic goals with DIU’s, officials cannot ensure that these components work in concert with DIU to achieve DIU 3.0’s strategic goal.

Our prior work has found that related goals can exist at multiple organizational levels. Showing how related goals align with each other can help illustrate and assess the contributions of individual activities to broader outcomes.[19] Ensuring that NSIN’s and NSIC’s strategic goals align with DIU’s 3.0 strategic goal can help demonstrate how these components organizations are working toward a common purpose with DIU.

DIU Has Opportunities to Enhance Collaboration by Assessing DOD Innovation Community’s Progress

DIU created DICE—a group of selected DOD innovation organizations—in 2023 as part of DIU 3.0. Prior to that, DOD’s innovation organizations did not coordinate sufficiently to optimize best practices transfer, talent management, or project prioritization and execution. Also, Army officials noted that prior to the formation of DICE, several DOD innovation organizations attempted to create a working group to enhance collaboration. However, the group disbanded in part because it lacked clear leadership and roles and responsibilities, and scheduling conflicts among the working group members made meeting difficult. The various innovation organizations continued collaborating on a project-level basis rather than working to solve common issues among DOD innovation organizations.

Under DIU 3.0, DICE’s role includes addressing common problems shared by DOD innovation organizations and building on existing collaborative practices to enhance future collaboration among DOD innovation organizations. According to DIU officials, DIU leads DICE by identifying and prioritizing opportunities to achieve synergies through the leadership of its four established working groups. DICE established the working groups in early 2024 to address four problem sets, as described in table 5.

|

Working group |

Purpose |

Leadership |

|

Connecting to Department of Defense (DOD) Demand |

Seeks to better communicate the demand signals for innovation across the DOD, reducing the siloes that limit insight into organizations’ priority capability needs. This will foster the ability to offer solutions or make longer-range planning assumptions to support these priorities. |

Joint Force Development Staff Army Applications Laboratory |

|

Improving Private Sector Engagement |

Seeks to improve DOD engagement with the private sector, including commercial technology companies and capital providers, so they can better access information on DOD’s capability needs and pathways to engage with DOD. |

Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) AFWERX |

|

Creating Shared Digital Tools |

Seeks to develop common digital tools and software to enable information sharing and collaboration among innovation organizations. This includes shared customer relationship management tools and cataloguing existing projects, contracts, and awards. |

DIU U.S. Special Operations Command AFWERX |

|

Managing Talent |

Seeks to find solutions to acquiring, promoting, and retaining defense innovation talent. |

DIU Marine Innovation Unit |

Source: GAO analysis of DIU information. | GAO‑25‑106856

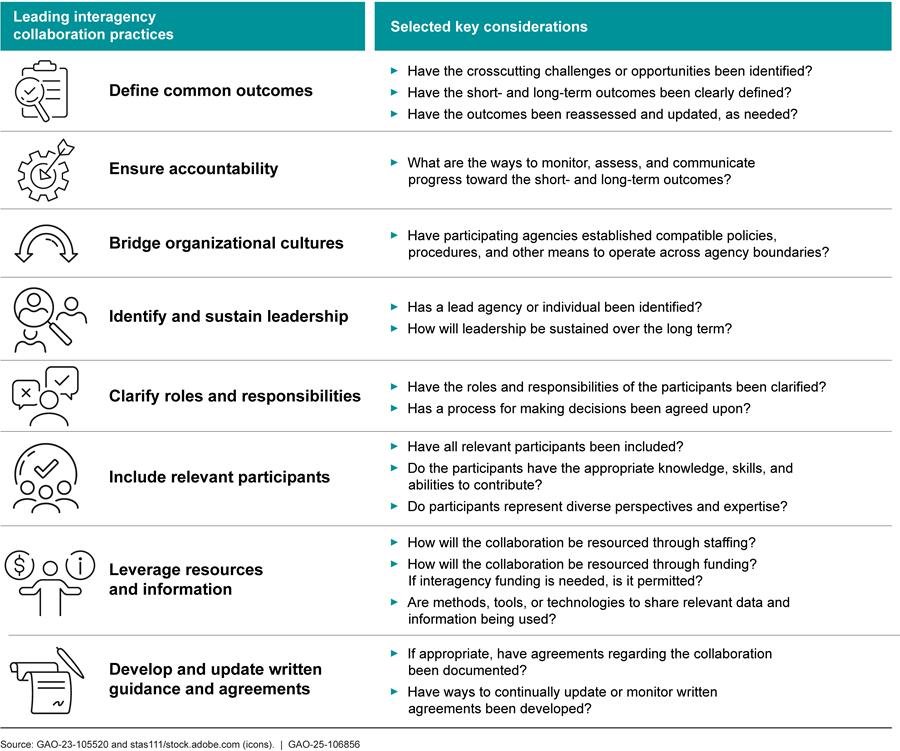

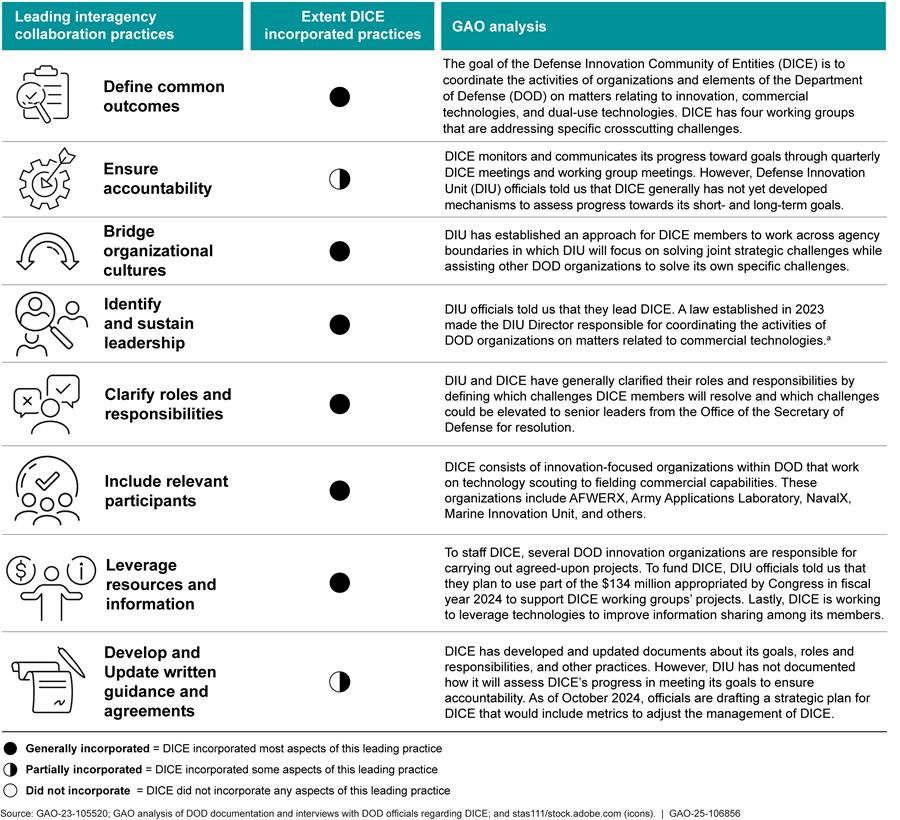

We have previously identified eight leading practices for implementing interagency collaboration from which collaborative mechanisms can benefit.[20] Our prior work has shown that these practices help agencies enhance and sustain collaboration to address complex issues. For this report, we used these eight leading practices to assess the effectiveness of DICE (see fig. 6).

Figure 6: Leading Interagency Collaboration Practices and Selected Key Considerations Identified in Our Work

Note: GAO’s eight leading practices for interagency collaboration each contain at least two key considerations against which GAO may evaluate collaboration efforts within and across government agencies. Not all key considerations apply in all situations. For this report, we assessed DICE against selected key considerations that we identified as relevant to improving how it collaborates on activities related to commercial technology adoption, and we excluded the other considerations when they were not applicable.

Through our assessment of DIU’s DICE efforts, we found that DICE has generally incorporated most of GAO’s leading collaboration practices as of October 2024. We found, however, that DICE did not fully meet two practices about assessing and documenting its progress toward meeting its goals to ensure accountability (see fig. 7).

Figure 7: GAO Analysis of the Extent to Which Defense Innovation Community of Entities (DICE) Incorporated Leading Interagency Collaboration Practices as of October 2024

aNational Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31, 913 (2023).

Of the eight leading practices, DICE has generally addressed six of them as of October 2024:

Define common outcomes. DIU has identified DICE’s overall goal to coordinate the activities of organizations and elements of DOD on matters relating to innovation, commercial technologies, and dual-use technologies. Also, according to DIU documentation, DICE could reduce duplication, inefficiencies, and missed opportunities for increasing strategic impact by addressing the lack of coordination between innovation organizations in DOD when adopting commercial technologies.

DICE identified crosscutting challenges that its four working groups are focused on addressing over the next 3 years or by 2026:

(1) connect DICE organizations’ work to address combatant commands’, services’, and other DOD components’ priority capability needs;

(2) coordinate DICE organizations’ engagement with the private sector to improve the private sector’s access to information about DOD’s capability needs and establish clear next steps when working with DOD;

(3) build shared digital tools across multiple organizations to exchange information such as a shared customer relationship management system; and

(4) attract and retain talent within DOD’s innovation organizations.

Each working group has updated its desired outcomes as needed and established short- and long-term goals to reach them. For example, initially, the working group focused on improving DOD’s engagement with the private sector identified a goal of developing a coordinated approach among DICE organizations when scouting for technology. By April 2024, this working group updated its technology scouting goals by defining short-term goals, such as mapping how DICE members conduct technology scouting to identify gaps in the process, and long-term goals, including creating draft policy to improve how an organization conducts technology scouting.

Bridge organizational cultures. DIU has established a strategic approach for DICE members to operate across agency boundaries. In the August 2023 memorandum regarding DIU 3.0, DIU noted that it needed to create a coordinated community of innovation to support DOD priorities. More specifically, DIU will focus to solve the strategic challenges such as adopting commercial technologies to address combatant command or joint challenges. DIU will also help other DOD organizations to solve its specific challenges. DIU officials told us they have shared this approach in working across agency boundaries with DICE members.

Identify and sustain leadership. Generally, DIU has identified leadership for DICE. For example, DIU officials told us they lead DICE, playing a central coordination role by facilitating a common understanding across DICE members. Army Applications Laboratory, AFWERX, Marine Innovation Unit, and NavalX officials—who are DICE members—stated that DIU is leading DOD’s innovation community in adopting commercial technology for military use. Several of these officials also said they have their own internal leadership who directs how they adopt commercial technology.

Furthermore, DIU has sustained leadership of DICE and commercial technologies activities unless there are further legislative changes. Specifically, in December 2023, Congress directed and the President signed into law that the DIU Director is responsible for coordinating the activities of DOD organizations on matters related to commercial technologies, dual use technologies, and the innovation of such technologies. DIU is also responsible for reporting on these activities directly to the Secretary of Defense.[21]

Clarify roles and responsibilities. DIU and DICE members have generally clarified their roles and responsibilities. For example, DIU identified two paths to address challenges in facilitating the adoption of commercial technology by either (1) resolving issues within DICE members’ senior leadership or (2) elevating issues to the Deputy’s Innovation Steering Group and Defense Innovation Working Group for resolution.[22] DICE members are responsible for addressing challenges—such as coordinating outreach to industry and developing a shared customer relationship management platform—through its four working groups. In contrast, Deputy’s Innovation Steering Group and Defense Innovation Working Group—groups with senior leaders from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, services, and combatant commands—could focus on resolving challenges such as the need for flexible requirements and obtaining funding to focus on long term technological needs.

Include relevant participants. DIU has generally included relevant participants into DICE. For example, as of October 2024, 32 innovation-focused organizations within DOD that work on technology scouting to fielding commercial capabilities have participated in DICE. These organizations include the services’ innovation organizations such as AFWERX, Army Applications Laboratory, NavalX, Marine Innovation Unit, and Office of the Secretary of Defense organizations such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and others. Marine Innovation Unit and AFWERX officials told us they thought DIU included the most relevant participants from the innovation community into DICE. Also, AFWERX officials said including too many other DOD innovation organizations at this early stage could prevent DICE from making decisions and implementing projects. DIU officials said they are considering whether to invite other DOD organizations—from the over 100 organizations in DOD’s innovation ecosystem—as DICE members while also ensuring that DICE remains effective.

Leverage resources and information. DICE generally leveraged staffing, funding, and technological resources to support the collaboration in addressing its shared challenges. For example, to staff DICE, several organizations are members of a working group and are responsible for carrying out projects that the group agrees upon. DIU officials told us they do not have adequate staffing to support DICE and are working to authorize additional staff. Furthermore, in December 2023, Congress directed and the President signed into law that the Secretary of Defense evaluate the staffing level of DIU to determine if it is sufficiently staffed to carry out its expanded responsibilities.[23] The law also required the Secretary to submit a report that would include the results of the DIU staffing evaluation and a plan to address DIU’s staffing shortfalls using funding or other means.

To fund DICE, DIU officials told us that they plan to use the $134 million appropriated by Congress in fiscal year 2024 to accelerate or expand existing commercial technology projects between DIU and DICE members and to support the DICE working groups’ projects such as shared digital tools and talent management initiatives. Lastly, DICE is working to leverage technologies to improve information sharing among its members, a long-standing coordination problem. For example, DICE plans to evaluate current members’ existing tools, available commercial tools, and custom-built solutions to recommend digital tools that will enable greater information sharing and collaboration across DICE organizations. According to DIU officials, DOD innovation organizations currently have different customer relationship management platforms that are not standardized and do not easily share information with one another. Army Applications Laboratory officials told us that shared tools would allow organizations to collaborate when they’re not co-located in a shared space.

We found that DICE partially addressed the two remaining leading interagency collaboration practices: (1) ensure accountability and (2) develop and update written guidance and agreements.

Ensure accountability. We found that DICE did not generally incorporate the leading practice of ensuring accountability, which involves monitoring, assessing, and communicating progress toward meeting its short- and long-term goals. Specifically, DICE monitors and communicates its progress through quarterly DICE meetings, more frequent working group meetings, and related meeting documentation. But DICE generally has not yet developed a process to assess progress toward its short- and long-term goals, according to DIU officials.[24] For example, the working group responsible for recruiting talent into innovation organizations identified a long-term goal to establish an integrated certification and badging program to ensure system access across organizations and encourage collaboration in 6 to 18 months. Subsequent meeting notes show that, nearly 3 months later, the group was unclear about key aspects of this goal such as a lack of clarity about what “certification” and “badging” meant, indicating that the working group did not have measures to assess progress toward its goal. We have reported that, if agencies do not use performance information and other types of evidence to assess progress toward goals, they may be at risk of failing to achieve their goals.[25]

In addition to not developing a process to assess progress, it is not clear how DIU will document how it intends to assess DICE’s progress in meeting its goals. DIU officials stated that they are drafting a strategic plan for DICE and will complete the plan by March 2025. Furthermore, they stated that the strategic plan will include metrics and information collected for these metrics will be used to adjust the management of DICE. However, as of October 2024, we do not have details about these metrics and whether they will measure DICE’s progress toward short- and long-term goals. DIU officials told us that completing the plan has been delayed to March 2025 in part because DIU is waiting for the services to identify innovation fielding organizations. DIU would need to integrate these organizations into DICE and the strategic plan.[26] We have previously reported that articulating agreements in formal documents can enhance accountability for results.[27] Agreements could include a document about how to track a group’s progress.

By not having a process to assess DICE’s progress toward meeting its goals, DIU lacks information to provide insight into the effectiveness of DICE’s collaboration. This puts DICE at risk of ineffective duplication and overlap, a problem that DIU has previously flagged about its past coordination efforts. For example, one DICE working group aimed to improve DOD innovation organizations’ engagement with companies by working collaboratively rather than in silos. The group planned to improve engagement in part by sharing research about a company’s security risks within DOD. This effort can reduce the administrative burden on companies. Without assessing the working group’s progress in improving engagement efforts, organizations might continue to work with companies in silos and miss opportunities to leverage each other’s work. This, in turn, could perpetuate the risk of duplication and overlap among organizations when engaging with companies. Our prior work has also shown that agencies that create a means to assess the results of collaborative efforts can better identify areas for improvement.[28]

Develop and update written guidance and agreements. DICE has developed and updated written documents about its goals, and roles and responsibilities among other leading practices for collaboration through shared documents and meeting notes. However, as previously discussed, DIU has not documented how it will assess DICE’s progress toward meeting its goals. As of October 2024, DIU is drafting a strategic plan for DICE that will include metrics to assess DICE. However, DIU has not finalized these metrics. By fully addressing the two practices of ensuring accountability and developing written guidance related to assessing progress, DICE could enhance how it achieves its goal of coordinating activities related to commercial technology adoption.

Conclusions

Leveraging innovative technologies plays a key role in sustaining the military superiority the U.S. relies on to deter major conflicts. Defense leaders recognize that private investment is the main driver of technology innovation and have built bridges with the commercial technology sector to adopt their technologies for military use through agencies like DIU. Since 2015, DIU’s outreach and prototyping processes have enabled DOD to adopt innovative technologies, but DIU has acknowledged that it must now focus on adopting and scaling those technologies that fill critical defense capability gaps. DIU initiated DIU 3.0 to address this challenge but has not established key performance elements such as goals and metrics to assess progress toward achieving this goal. To that end, DIU has not developed a process to collect, assess, and use metrics-based data to inform decisions about DIU 3.0’s future. While the integration of NSIN and NSIC into DIU consolidates efforts to leverage talent and technology from academia, federal research laboratories, and the private sector, DIU has not confirmed their goals align with DIU 3.0 to ensure these organizations work toward a common purpose to address critical defense capability gaps.

As DIU refocuses under DIU 3.0, it is increasingly collaborating with other defense innovation organizations to use commercial technology to address critical operational challenges across DOD. Through DICE, DIU has collaborated with other DOD innovation organizations to address shared challenges such as improving engagement with commercial companies. However, DIU lacks a plan documenting how it will assess the progress DICE is making toward meeting its goals to ensure accountability for results and assess DICE’s collaboration efforts based on that information. Ultimately, taking these actions will better position DICE to achieve its intended goals and support better collaboration.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following six recommendations to DOD:

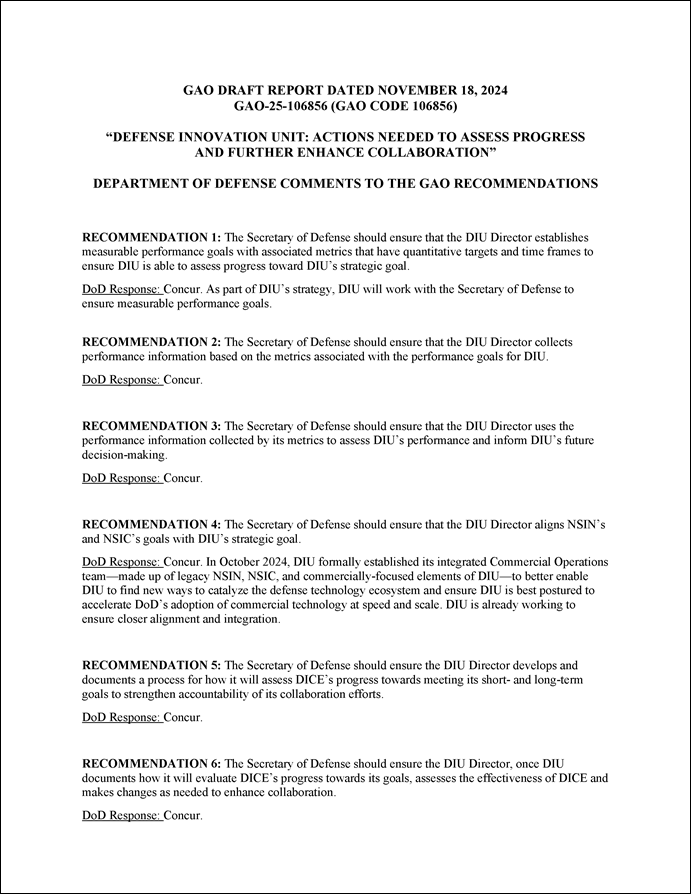

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the DIU Director establishes measurable performance goals with associated metrics that have quantitative targets and time frames to ensure DIU is able to assess progress toward DIU’s strategic goal. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the DIU Director collects performance information based on the metrics associated with the performance goals for DIU. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the DIU Director uses the performance information collected by its metrics to assess DIU’s performance and inform DIU’s future decision-making. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the DIU Director aligns NSIN’s and NSIC’s goals with DIU’s strategic goal. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure the DIU Director develops and documents a process for how it will assess DICE’s progress toward meeting its short- and long-term goals to strengthen accountability of its collaboration efforts. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure the DIU Director, once DIU documents how it will evaluate DICE’s progress toward its goals, assesses the effectiveness of DICE and makes changes as needed to enhance collaboration. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a copy of this report to DOD and DIU for review and comment. In its response, which is reprinted in appendix III, DIU agreed with all six of our recommendations. DIU also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Specifically, with regard to recommendation 1, DIU said that they will work with the Secretary of Defense to ensure measurable performance goals as part of its strategy. With regard to recommendation 4, DIU noted that they formally established an integrated commercial operations team that incorporates NSIN and NSIC and DIU will continue working to ensure the entities are more closely aligned and integrated. This is a positive first step, and it will also be important to establish specific and measurable goals that will demonstrate how NSIN’s and NSIC’s goals are aligned with DIU’s 3.0 strategic goal.

We are sending copies of this report to the Department of Defense. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-4841 or russellw@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

W. William Russell

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mitch McConnell

Chairman

The Honorable Chris Coons

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Senate Armed Services Committee Report accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to assess the effectiveness of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in meeting its mission to field and scale commercial technology across the military.[29] Also, the Conference Report accompanying the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 includes a provision for us to evaluate the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN)—a component of DIU.[30] This report (1) describes how DIU transitioned commercial technologies for military use and any changes DIU is considering when transitioning technologies; (2) examines the extent to which DIU has established a performance management process to assess its progress in meeting current and future goals; and (3) examines what opportunities exist to enhance DIU’s collaboration with other Department of Defense (DOD) innovation organizations to adopt commercial technologies for military use.

To describe DIU’s process for transitioning commercial technologies and any forthcoming changes, we reviewed DIU documentation, including guidance pertaining to DIU’s commercial solutions opening (CSO) process. We interviewed senior DIU officials, including DIU technology portfolio directors, regarding DIU’s processes for awarding and executing prototype awards and how DIU supports the transition from prototype to production contracts. We analyzed DIU-provided data about the prototype agreements awarded between fiscal years 2016 to 2023, which included information for prototype agreement awarded, including the projects there were associated, the applicable DIU technology portfolio, the dollars obligated by DIU and the DOD and civilian partners, and the agreement award and end dates, among other fields. We used this information to describe the number of prototype agreements awarded for DIU projects and the associated obligations. We also reviewed DIU-provided information on the number of agreements that transitioned to production for procurement and fielding.

To determine the reliability of these data, we requested and received information from DIU regarding the data system, access, and usage, among other factors. We also compared our analysis using this information to information published in DIU’s annual reports and explained any differences. We determined DIU’s data to be reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives. Using these data, we also selected a nongeneralizable sample of six DIU projects for further review. To obtain a mix of technologies, we selected projects from each of DIU’s six technology portfolios. We also selected projects to reflect different stages of the prototyping process, including projects that had prototypes in progress, projects that had successfully completed prototypes that were transitioned to production, and projects that were completed but did not transition to production. We also selected projects with higher obligation values. For each project, we reviewed selected pre-award and agreement documentation and either interviewed or asked questions of the associated DIU project staff. We also interviewed the end users of three of the selected projects to better understand their experience in working with DIU.

To determine the extent to which DIU has established a performance management process to assess its progress in meeting current and future goals, we compared DIU’s efforts against GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking.[31] These practices describe a three-step performance management process in which organizations (1) define goals to communicate the results an organization wants to achieve, (2) collect related information to assess progress, and (3) use that information to determine how well they are performing and identify opportunities to improve results. Specifically, our past work describes two types of goals—strategic and performance. Strategic goals are long-term outcomes an organization wants to achieve to advance its mission, while performance goals are near-term quantitative targets of performance and timeframes against which performance can be measured.

To determine the extent to which DIU defined strategic goals and performance measures under DIU 2.0 and DIU 3.0, we reviewed the DIU 3.0 plan and implementation milestones for each of DIU 3.0’s eight lines of effort. We also requested and reviewed DIU plans and collected information to identify DIU’s current and future goals. Moreover, we interviewed DIU officials to learn about efforts to develop performance goals and metrics for DIU 2.0 and DIU 3.0.