WILDFIRES

Additional Actions Needed to Address FEMA Assistance Challenges

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106862. For more information, contact Chris Currie at (404) 679-1875 or curriec@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106862, a report to congressional committees

Additional Actions Needed to Address FEMA Assistance Challenges

Why GAO Did This Study

In recent decades, much of the nation has witnessed an increase in the size and severity of wildfires. At the same time, development in and around wildland areas has increased. Demand for federal resources to mitigate against, respond to, and recover from these wildfires has increased.

The FEMA Improvement, Reform, and Efficiency Act of 2022 includes a provision for GAO to examine FEMA wildfire assistance programs. This report examines (1) FEMA assistance to wildfire-affected communities from fiscal years 2019 through 2023, and (2) challenges communities face with this assistance and to what extent FEMA has taken steps to address them.

GAO analyzed data from FEMA assistance programs from fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and reviewed agency policies, guidance, and assessments of FEMA’s wildfire assistance. GAO interviewed officials from FEMA and a non-generalizable sample of seven state, 11 local, and four tribal governments that obtained FEMA assistance for wildfires during this period. GAO conducted site visits to Hawaii, Washington, and the Nez Perce Tribe.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including for FEMA to provide immediate post-wildfire mitigation assistance and to establish a process to collect, assess, and incorporate ongoing feedback from FMAG recipients. DHS concurred with five recommendations and did not concur with one recommendation. GAO continues to believe all six recommendations are warranted.

What GAO Found

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), provided over $3.8 billion in wildfire-related assistance from fiscal years 2019 through 2023. The agency obligated about $3.2 billion in Public Assistance grants for emergency work (such as debris removal and emergency protective measures), and permanent recovery work (repairing or replacing roads, utilities, and buildings).

GAO interviewed officials from 22 state, local, and tribal governments about their experiences obtaining FEMA assistance for wildfires. Examples of challenges officials cited included:

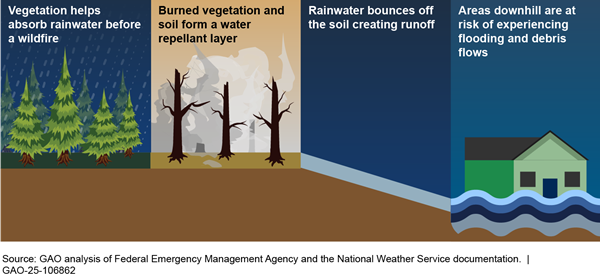

· Post-wildfire Mitigation. Wildfires destroy vegetation and damage soil, creating conditions that can increase immediate risks of flooding, erosion, and debris flows—fast-moving, destructive landslides that often strike without warning. GAO found that communities continue to face challenges addressing post-wildfire risks, in part because FEMA’s assistance programs are too slow to support more timely post-wildfire mitigation. Taking steps to provide immediate post-wildfire mitigation assistance could help foster more resilient communities and reduce future demand on federal resources.

· Fire Management and Assistance Grants (FMAG) management. State, local, and tribal officials GAO interviewed said they faced challenges associated with the FMAG program, including the quantity and complexity of required paperwork, and confusion over eligibility requirements. However, FEMA does not collect ongoing, nationwide feedback from state, local, and tribal FMAG recipients, as it does for other grant programs. Collecting, assessing, and incorporating such feedback into program policy, as appropriate, would help FEMA address challenges.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

FMAG |

Fire Management Assistance Grant |

|

HMGP |

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

|

NEPA |

National Environmental Policy Act |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 18, 2024

Congressional Committees

In August 2023, the U.S. experienced the deadliest wildfire in over a century on the island of Maui in Hawaii. Multiple fast-moving fires spread across Maui, devastating the town of Lahaina, claiming over 100 lives, displacing nearly 10,000 survivors, and damaging or destroying more than 2,000 structures. In recent decades, much of the nation has witnessed an increase in the size and severity of wildfires, as well as longer wildfire seasons. At the same time, development occurring in and around wildland areas has increased, placing more people, businesses, and infrastructure at risk. Further, in some states, insurers have increased premiums or stopped issuing new policies altogether, due in part to increasing wildfire risk and associated costs. Because of these trends, demand for federal resources to mitigate against, respond to, and recover from these wildfires has increased.

Numerous federal departments and agencies have roles in wildfire mitigation, response, and recovery. Among them, within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) leads the nation’s efforts to mitigate against, respond to, and recover from natural disasters, including wildfires. FEMA provides direct assistance and administers grant programs to state, local, territorial, and tribal governments, as well as aid to individual survivors. FEMA also coordinates across federal agencies to help state, local, territorial, and tribal governments following wildfire disasters.

In response to the challenges that wildfires pose for the nation, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act required the establishment of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission in 2021.[1] This Commission—comprised of 56 members, including five FEMA representatives—was tasked with creating policy recommendations to address wildfire mitigation and management, and post-fire rehabilitation and recovery. In its September 2023 report (the Commission report), the Commission issued a set of policy priorities and recommendations calling for greater coordination, interoperability, collaboration, and simplification within the wildfire system.[2]

Our prior work has identified opportunities for the federal government to improve wildfire disaster mitigation, response, and recovery efforts. For example, in 2019, we reported on challenges that communities faced that were specific to and further complicated by the nature of wildfire disasters.[3] Given that land use practices and climate trends would continue to increase the likelihood that severe and intense wildfires would affect people and communities, we recommended that FEMA comprehensively assess how its policies and procedures work for addressing large-scale fires. In response, FEMA conducted such an assessment in July 2021. It has also taken some actions to better align its operations to address wildfires.

The FEMA Improvement, Reform, and Efficiency Act of 2022 includes a provision that we examine FEMA’s policies and procedures and identify ways to improve its ability to assist state, local, and tribal governments in recovering from wildfires, among other things.[4] This report examines:

1. the assistance FEMA provided to wildfire-affected communities from fiscal years 2019 through 2023; and

2. any challenges affected communities face with FEMA wildfire assistance and the extent to which FEMA has taken steps to address them.

Our review examined wildfire declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and assistance FEMA provided to wildfire-affected communities during that time.[5] To answer our research questions, we analyzed data from fiscal years 2019 through 2023 for five major FEMA assistance programs: (1) Public Assistance, (2) Fire Management Assistance Grant (FMAG), (3) Individual Assistance, (4) Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) and HMGP Post-Fire, and (5) Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities. These programs represent the bulk of FEMA’s assistance for wildfires from fiscal years 2019 through 2023.[6] To assess the reliability of these data, we conducted electronic data testing, reviewed database documentation, and interviewed knowledgeable agency officials about the processes for collecting and maintaining these data. Based on these steps, we determined the data to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

We interviewed FEMA officials and officials from a non-generalizable sample of 22 state, local, and tribal governments that obtained FEMA assistance for wildfires during this period. We selected these entities to obtain a variety of perspectives based on factors such as geographic location, number and type of wildfire declarations, and—for local governments—socio-economic status. Information from the interviews is not generalizable, however.

We also conducted site visits to Hawaii, Washington, and the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho to obtain state, local, and tribal perspectives on FEMA assistance for wildfires. In September 2023, we visited five Washington counties and the Nez Perce Tribe, all of which received one or more FMAG and/or wildfire major disaster declarations from fiscal years 2019 through 2022. We also visited Hawaii in September 2023 to observe response and initial recovery efforts after the August 2023 wildfire major disaster. We conducted these visits to obtain state, local, and tribal perspectives on obtaining FEMA assistance; however, information from the visits is not generalizable. Lastly, we reviewed agency guidance, as well as assessments of FEMA’s wildfire assistance and relevant laws. See appendix I for additional details about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FEMA Assistance for Wildfires

FEMA assists state, local, and tribal governments in addressing wildfire threats as the lead federal agency for disaster mitigation, response, and recovery. While state and local entities have the primary responsibility for managing wildfires on non-federal land, these entities can seek FEMA assistance if a wildfire exceeds, or threatens to exceed, their ability to effectively respond. Additionally, FEMA may provide technical assistance and training and technological support to eligible state, local, and tribal governments.

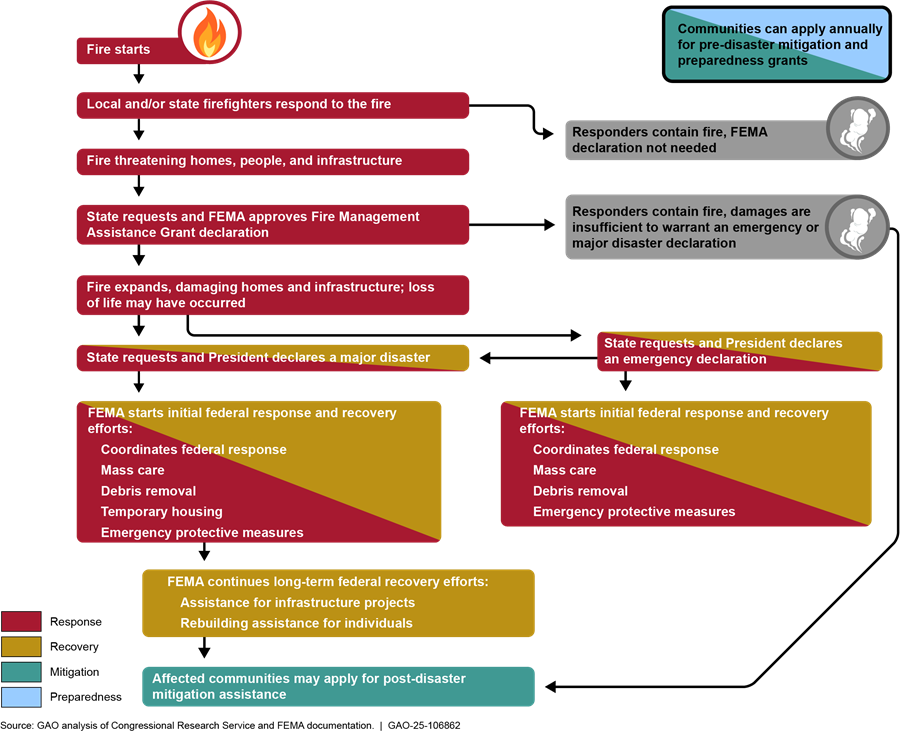

Federal Declarations for Wildfires

As shown in figure 1, FEMA provides most assistance for wildfires through three types of declarations: 1) Fire Management Assistance Grant (FMAG) declarations, 2) major disaster declarations, and 3) emergency declarations.[7]

Notes: FEMA may approve Fire Management Assistance Grant declarations for wildfire events only, whereas emergency and major disaster declarations may be approved for all eligible hazards.

aWhile emergency declarations can authorize some Individual Assistance programs, it is rare. FEMA’s Individual Assistance program consists of multiple component programs, including the Individuals and Households Program, which provides assistance to eligible uninsured or underinsured individuals and households with necessary expenses and serious needs due to the disaster.

FMAG declarations. When a wildfire burns on public or private land and threatens to become a major disaster, a state may request an FMAG declaration.[8] While the fire is burning uncontrolled, a state can submit a verbal request for an FMAG declaration to the designated FEMA regional office, followed within 14 days by a formal written request.[9] The FEMA regional administrator then either approves or denies the request based on FMAG declaration criteria and after consulting with relevant officials from the U.S. Forest Service or bureaus within the U.S. Department of the Interior about technical aspects of the fire.[10]

A state approved for an FMAG declaration may then apply for grant funding to reimburse eligible expenses. The state must demonstrate that the wildfire meets pre-established cost thresholds when submitting the grant application.[11] Eligible FMAG costs include equipment and supplies, labor costs, temporary repairs of damage caused by firefighting activities, mobilization and demobilization of resources, and limited costs of pre-positioning fire prevention or suppression resources.[12] Additionally, FEMA authorizes Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) Post-Fire for affected communities, which funds post-disaster mitigation projects. HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire provide grants to rebuild while mitigating future natural disaster losses.

Major disaster declarations. A state or tribal government can request that the President declare a major disaster when a wildfire is of such severity and magnitude that an effective response is beyond state, local, and/or tribal capabilities and federal assistance is therefore necessary.[13] According to FEMA guidance, the agency will generally not recommend a major disaster declaration for a wildfire unless the fire causes significant impacts and costs that cannot be addressed by the FMAG program.[14] A major disaster declaration may provide a wide range of federal support through three key grant programs—Public Assistance, Individual Assistance, and HMGP. Table 1 describes the types of assistance available under these programs.

Table 1: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Assistance Available under Major Disaster Declarations

|

FEMA Program |

Who may apply directly |

Assistance provided |

|

Public Assistance |

Eligible state, local, territorial, and tribal governments, and certain nonprofit organizations |

· Emergency work, such as debris removal and emergency protective measures. · Permanent work, such as repairing or replacing roads and bridges, water control facilities, buildings and equipment, utilities, and parks or other recreational facilities. |

|

Individual Assistance |

Eligible disaster survivors and households |

· Housing assistance, such as rental assistance and/or home rebuilding assistance. · Other needs assistance, such as funeral expenses or medical costs. · Transitional sheltering assistance for temporary sheltering via hotels. · Disaster legal services, unemployment assistance, case management, and crisis counseling services. |

|

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

State, territorial, and tribal governmentsa |

· Mitigation projects designed to reduce risk and the potential impacts of future disasters. · Examples of possible project types include property acquisition, flood risk reduction, wildfire mitigation, retrofits, secondary power sources (e.g., generators), and warning systems. |

Source: GAO summary of FEMA documentation and federal law. | GAO‑25‑106862

Note: A state, territorial, or tribal government can request that the President declare a major disaster when a wildfire is of such severity and magnitude that an effective response is beyond state, local, and/or tribal capabilities and federal assistance is therefore necessary. Not all major disaster declarations authorize all three of these assistance programs.

aA governor, tribal chief executive, or equivalent, may request that Hazard Mitigation Grant Program assistance be available throughout the state, local, territorial, or tribal area or only in specific jurisdictions. Local governments can apply for Hazard Mitigation Grant Program assistance as sub-applicants. Depending on the declaration, jurisdictions not affected directly by the disaster may qualify for assistance.

FEMA can also provide direct federal assistance under major disaster and emergency declarations. For example, FEMA can mobilize mass care resources, including providing meals and water. In some cases where a declaration authorizes Individual Assistance, FEMA may provide direct temporary housing, such as manufactured housing units. FEMA can also “mission assign” tasks to other federal agencies.[15] These tasks can include debris removal, hazardous waste disposal, mortuary and forensic services, search and rescue, and more.

The President declared 13 major disasters for wildfires from fiscal years 2019 through 2023. California received five such declarations, Colorado two, and Hawaii, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation one each.

Emergency declarations. A state or tribal government may request an emergency declaration, which is issued by the President.[16] According to FEMA, emergency declarations are most often declared for wildfires when multiple fires are burning in a state simultaneously and the state needs direct federal support. Such a declaration makes limited federal financial and direct assistance available, such as for emergency response work under Public Assistance.[17] In some cases, emergency declarations may authorize some Individual Assistance programs for survivors. The President declared three emergency declarations for wildfires during fiscal years 2019 through 2023, with California receiving two and Oregon one. Each of these incidents later received major disaster declarations.

The type of declaration and nature of the wildfire determine the categories of assistance FEMA provides. For example, a state may initially request an FMAG declaration to obtain reimbursement for fire suppression activities for a wildfire threatening significant destruction if not contained. If the wildfire cannot be contained and causes significant damage, a state may request a major disaster declaration to receive additional types of assistance. Figure 2 demonstrates key decision points in FEMA’s provision of assistance for wildfires.

Notes: This figure represents one example of a wildfire and the different declarations and assistance paths that it could take. The timelines are not necessarily linear as several types of assistance could occur simultaneously and each wildfire has unique needs. Initial response efforts start at the local level and involve state and federal assistance when necessary. Eligibility for state, local, territorial, and tribal governments to apply directly for funding varies by program. Additionally, while assistance to individuals may be authorized under an emergency declaration, it is rare.

Competitive Grants and Non-financial Assistance

FEMA also provides financial assistance to wildfire-affected communities through competitive grant programs for mitigation and preparedness.[18] These programs are not activated in response to any type of declaration, but instead operate on an annual fiscal year funding cycle. For example, Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities is an annual hazard mitigation grant program designed to reduce risks from disasters and natural hazards.[19] State, tribal, and territorial applicants can apply for grants for mitigation projects, capability and capacity building activities, and management costs.[20] Mitigation projects are construction projects designed to increase resilience and protect life and property from natural hazards. Capability and capacity building activities are designed to enhance knowledge and skills of the current workforce or improve the administration of mitigation assistance (e.g., establishing partnerships, project scoping, hazard mitigation planning).[21]

In addition to financial assistance, FEMA provides other forms of assistance to wildfire-affected communities, such as technical assistance, and training and technological support. FEMA’s technical assistance includes educating potential applicants about programs they may be eligible for, assisting applicants through the application process, and creating guidance documents for applicants and recipients. Additionally, FEMA’s U.S. Fire Administration provides training and technological support to help communities address structural and wildfire needs. For example, its National Fire Academy provides fire and emergency response training, and its National Fire Data and Research Center conducts research into firefighting methods and technologies.

Other Federal Agencies’ Responsibilities for Wildfires

In addition to FEMA, multiple other federal entities have responsibilities for federal wildfire mitigation, response, and recovery efforts. For example, the U.S. Forest Service within the Department of Agriculture and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service within the Department of the Interior, are responsible for managing wildfires on federal lands they oversee. The U.S. Forest Service is the lead agency for wildfire response under the National Response Framework, while the Bureau of Indian Affairs provides wildfire protection for approximately 55 million acres of lands held in trust by the U.S. for Tribes, individuals, and Alaska Natives.[22] This protection includes wildfire prevention, fuels management, response, and post-wildfire recovery activities.

Some of these agencies or departments administer programs that state, local, and/or tribal governments could access to address wildfire hazards.[23] Additionally, state, local and tribal governments can enter into mutual aid agreements with federal agencies to enable coordinated responses. Mutual aid agreements may authorize mutual aid between two or more neighboring communities, among jurisdictions within a state, between states, federal agencies, or internationally. Under these agreements, federal firefighters may respond to wildfires burning on state or private land and vice versa.

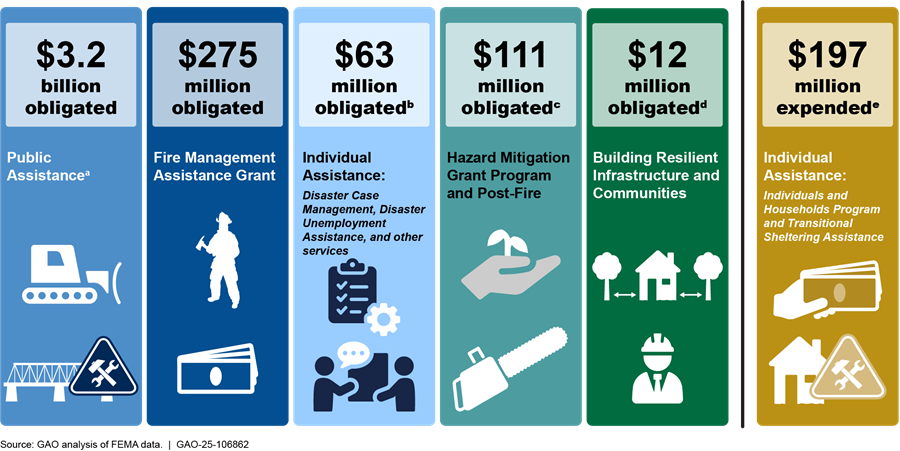

FEMA Provided Over $3.8 Billion in Wildfire Assistance from Fiscal Years 2019 through 2023

FEMA provided billions of dollars in wildfire-related financial assistance through five primary assistance programs from fiscal years 2019 through 2023.[24] Specifically, FEMA obligated $3.6 billion across four programs—(1) Public Assistance, (2) Fire Management Assistance Grant, (3) Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) and HMGP Post-Fire, and (4) Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities—and selected components of its Individual Assistance program, as seen in figure 3.[25] Additionally, FEMA expended about $197 million for the Individuals and Households and Transitional Sheltering Assistance programs—two of its Individual Assistance component programs for which the agency tracks expenditures rather than obligations.[26] Of the total amount FEMA obligated, about 89 percent, or $3.2 billion, was for emergency and permanent recovery work through Public Assistance. For Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, we identified $12 million in wildfire-related obligations during the program’s fiscal year 2020 through 2022 funding cycles. FEMA obligated an additional $386 million in assistance under the Fire Management Assistance Grant program and HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire.

Figure 3: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Financial Assistance for Wildfires, Fiscal Years 2019-2023

Notes: Figures are rounded and include obligations or expenditures for declarations approved in fiscal years 2019-2023, except for Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, which is an annual grant program. The program’s first funding cycle was in 2020 and as of the time of our data request in October 2023, FEMA had not yet closed the application period for the fiscal year 2023 funding cycle. During this period, FEMA was in the process of making obligations and expenditures for declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and FEMA may continue to obligate and expend funds in future years for those declarations. Additionally, FEMA was in the process of making obligations for Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities projects selected in fiscal years 2020 through 2022. FEMA may also de-obligate funds, especially at the end of the process. As a result, obligated and expended amounts for these programs will change over time.

aFEMA’s Public Assistance assists communities through emergency assistance to save lives and protect property and/or assistance to permanently restore community infrastructure.

bFEMA tracks obligations for the following Individual Assistance component programs: Disaster Case Management, Disaster Unemployment Assistance, Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program, and Disaster Legal Services.

cApplicants can use Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and Hazard Mitigation Grant Program Post-Fire to address any type of natural disaster, and many projects are multi-hazard in nature. We considered a project wildfire-related if applicants chose a project type containing the word “wildfire” and/or if they indicated the primary hazard type for the project was fire.

dIn our analysis, wildfire-related projects are those for which the applicant selected “fire” as a primary, secondary, or tertiary hazard. Some of these projects are multi-hazard planning projects, including developing hazard mitigation plans.

eFEMA reported obligating about $212 million for the Individuals and Households Program and about $69 million for Transitional Sheltering Assistance for disasters declared in fiscal years 2019 through 2023. According to FEMA officials, FEMA tracks expenditures, rather than obligations, for these programs and noted the obligations reported for these programs are estimates. When a disaster starts, FEMA obligates a pool of money that the Individuals and Household Program and Transitional Sheltering Assistance programs then draws down by making payments to individuals and to hotels, respectively. FEMA reconciles the obligations and expenditures during the disaster closeout process.

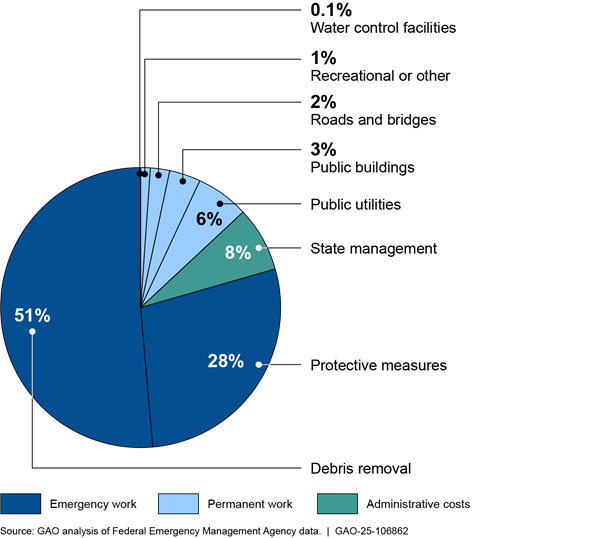

Public Assistance. FEMA obligated about $3.2 billion for Public Assistance projects for 12 wildfire major disaster declarations approved from fiscal years 2019 through 2023 across six states and one Tribe, as of September 2023.[27] FEMA obligated over $2.5 billion for emergency work, such as debris removal and protective measures; about $416 million for permanent work, such as projects to rebuild or repair bridges, roads, and public utilities; and about $237,000 for state administrative costs, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Public Assistance Obligations by Project Category for Wildfire Major Disasters, Fiscal Years 2019-2023

Notes: The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s Public Assistance grant program assists communities through emergency assistance to save lives and protect property and/or assistance to permanently restore community infrastructure. FEMA obligated about $3.2 billion through the Public Assistance program for wildfire major disaster declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023, as of September 2023. A state, territorial, or tribal government can request that the President declare a major disaster when a wildfire is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the state, local, territorial, and/or tribal capabilities and federal assistance is necessary.

Debris removal comprised a higher proportion of Public Assistance obligations for wildfire disasters (51 percent) compared to non-wildfire disasters during the same time period (24 percent). Wildfires create unique debris removal challenges because they typically leave no remaining structures. Additionally, the resulting ash contains contaminants that must be carefully removed and disposed of before survivors can return to their properties. Therefore, the wildfire debris removal process can be costlier and more complicated than for other types of disaster debris, as we have previously reported.[28]

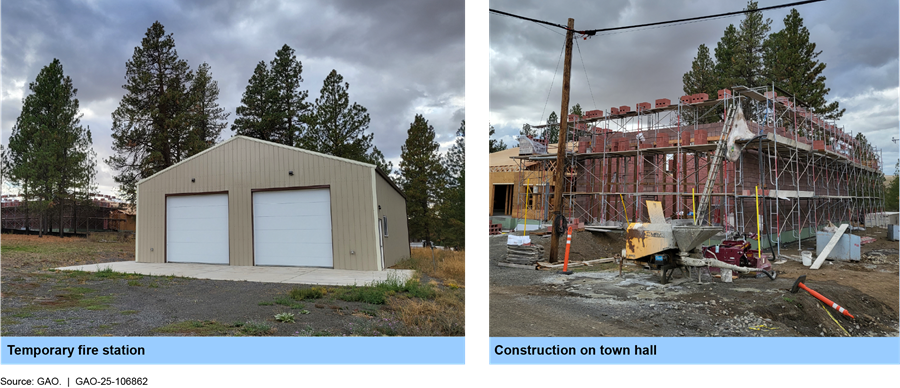

In addition to debris removal, local and tribal officials we interviewed used Public Assistance grants for a variety of purposes, such as replacing guardrails and fencing, personnel costs, repairing electrical poles and lines, and rebuilding public facilities. For example, the town of Malden in Whitman County, Washington, received Public Assistance to rebuild public infrastructure and to provide temporary structures for key government services following a 2020 wildfire major disaster. The town used Public Assistance grants for building a temporary fire station and rebuilding a new multi-purpose town hall building, among other projects, as shown in figure 5.

Fire Management Assistance Grants. As of September 30, 2023, FEMA obligated about $275 million through 89 of the 209 FMAG declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023, as shown in table 2.[29] For FMAG declarations with associated grants, the median amount obligated by declaration was about $417,000. We also found about 41 percent of FMAG declarations and more than half of the fire mitigation assistance grant funding, were for wildfires approved in fiscal year 2020.

Table 2: Number of Fire Management Assistance Grant (FMAG) Declarations and Amounts Obligated by Declaration Fiscal Year

|

Declaration Fiscal Year |

Number of FMAG Declarations |

Number of FMAG Declarations with Obligations |

Total Amount Obligateda |

|

2019 |

15 |

11 |

$32,600,000 |

|

2020 |

85 |

44 |

$149,900,000 |

|

2021 |

40 |

18 |

$80,800,000 |

|

2022 |

38 |

16 |

$11,900,000 |

|

2023 |

31 |

0 |

$0 |

|

Total |

209 |

89 |

$275,200,000 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑106862

Note: A state or territory may request an FMAG declaration when a wildfire burns on public or private land and threatens to become a major disaster. The FMAG program assists in reimbursement for equipment, supplies, and personnel.

aAmounts obligated are rounded to the nearest hundred thousand, by the fiscal year the FMAG declaration was approved, and are as of the end of fiscal year 2023. FEMA was in the process of making obligations for declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and may continue to make obligations in future years for those declarations. Additionally, FEMA may de-obligate funds, especially at the end of the process. As a result, obligated amounts will change over time. FEMA officials provided several reasons FMAG declarations may not have obligations, such as applications being in process, declarations being rolled up into major disaster declarations, or applicants not meeting cost thresholds to receive FMAG grants under an approved declaration.

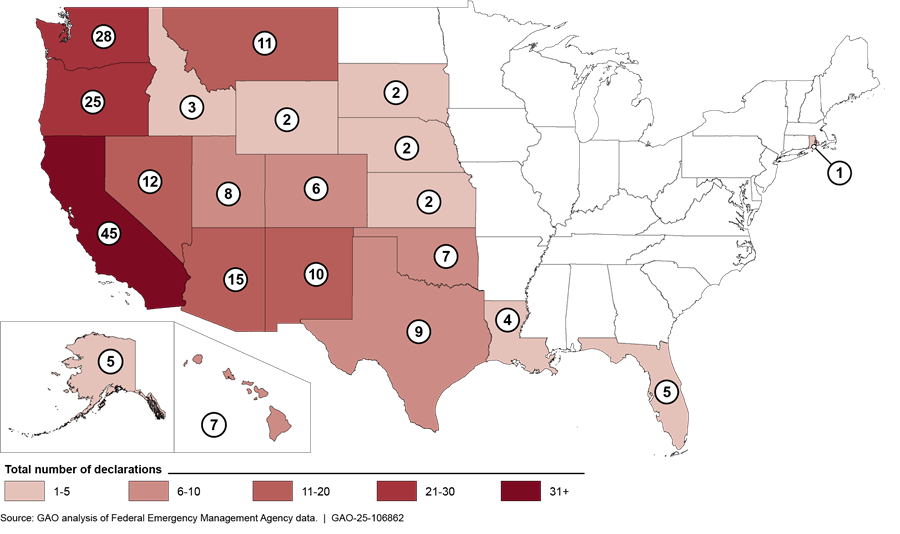

The majority of FMAG declarations were in western states, as shown in figure 6. Four states—California, Oregon, Alaska, and Arizona—represented about 43 percent of the FMAG declarations (90 of 209) and received about 94 percent of grant obligations (about $258 million). Counties we spoke with reported using FMAG funding for purposes such as overtime pay, roadblocks, temporary firefighter pay, or replacing or purchasing equipment such as firetrucks.

Note: A state or territory may request a Fire Management Assistance Grant declaration when a wildfire burns on public or private land and threatens to become a major disaster.

Individual Assistance. FEMA authorized Individual Assistance for eight of the 13 wildfire major disasters declared in fiscal years 2019 through 2023. FEMA tracks expenditures for two of its Individual Assistance component programs—Individuals and Households Program and Transitional Sheltering Assistance—and obligations for the other programs. As shown in table 3, the Individuals and Households Program accounted for 97 percent ($191 million) of FEMA’s expenditures for these two programs for wildfire disasters during this time.[30] FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program provides financial assistance and direct services to eligible individuals and households who have uninsured or underinsured necessary expenses and serious needs due to the disaster.

Table 3: FEMA Individual Assistance Component Program Expenditures for Wildfire Disasters Declared Fiscal Years 2019-2023

|

Individual Assistance Component Program Name |

Number of disasters with expenditures |

Expenditures |

|

Individuals and Households Program- Housing Assistance |

8 |

$138 million |

|

Individuals and Households Program- Other Needs Assistance |

8 |

$53 million |

|

Transitional Sheltering Assistance |

3 |

$6 million |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑106862

Notes: FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program provides financial assistance and direct services to eligible individuals and households who have uninsured or underinsured necessary expenses and serious needs due to the disaster. The Transitional Sheltering Assistance program provides temporary sheltering in hotels for survivors. Expenditure data for the Individuals and Households Program are as of October 2023. Transitional sheltering assistance expenditures are as of November 2023. FEMA was in the process of making expenditures for declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and may continue to make expenditures in future years for those declarations. As a result, expended amounts will change over time.

FEMA also obligated about $63 million through its other Individual Assistance programs, which provide assistance for services such as counseling, legal advice, and case management, as shown in table 4.[31]

Table 4: FEMA Individual Assistance Component Program Obligations for Wildfire Disasters Declared Fiscal Years 2019-2023

|

Individual Assistance Component Program Name |

Number of disasters with obligations |

Obligations |

|

Disaster Case Management Provides financial assistance to state, local, territorial, and tribal government agencies, or qualified private organizations to provide case management services to survivors. |

7 |

$33 million |

|

Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program Provides financial assistance to eligible state, local, territorial, and tribal governments and non-governmental organizations to provide survivors with supportive crisis counseling, development of coping skills, and connections to appropriate resources, among other things. |

8 |

$23 million |

|

Disaster Unemployment Assistance Provides unemployment benefits and re-employment assistance to survivors who are not eligible for regular state unemployment insurance. |

8 |

$7 million |

|

Disaster Legal Services Provides legal aid to low-income survivors through an agreement with the Young Lawyers Division of the American Bar Association. |

8 |

$0.03 million |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑106862

Notes: Obligations for these Individual Assistance component programs are as of November 2023. FEMA was in the process of making obligations for declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and may continue to make obligations in future years for those declarations. Additionally, FEMA may de-obligate funds, especially at the end of the process. As a result, obligated amounts will change over time.

For FEMA’s largest Individual Assistance component program—the Individuals and Households Program—we previously reported that from 2010 through 2019, the median amount provided to individual survivors for all hazards was relatively small compared to the maximum allowable amount.[32] According to FEMA analysis of program data from 2013 through 2023, the median award was $1,000 for non-wildfire disasters and $3,150 for wildfire disasters, which tend to completely destroy homes. FEMA officials explained that most individuals received relatively small awards compared to the maximum amounts because most individuals have homeowner’s insurance. Until recent regulatory changes, FEMA did not award any housing assistance to individuals who received at least the maximum FEMA award for housing repairs from their insurance company, even if there was a gap between their insurance coverage and their losses. For disasters with Individual Assistance declared on or after March 22, 2024, FEMA will now award housing assistance to those who receive insurance payouts that exceed the FEMA maximum award for their losses, up to the statutory maximums, if they have eligible unmet needs or uncovered losses.[33] FEMA officials said they expect the amounts of Individual Assistance the agency awards to increase due to this change.

HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire. Relatively few of the HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire projects (about 6 percent, or 393 of 6,798) submitted under declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 were wildfire-related.[34] For wildfire-specific declarations, this increased to 35 percent (311 of 893) of HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire projects that were wildfire-related. FEMA obligated about $111 million for these wildfire mitigation projects as of October 2023, as shown in table 5.[35] Applicants may submit HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire projects relating to any type of eligible hazard, not only the type of hazard that led to the declaration. For example, if a state receives a major disaster or FMAG declaration for a wildfire, communities can apply for HMGP or HMGP Post-Fire funding to mitigate against other specific hazards, such as earthquakes, or for multi-hazard projects, such as updating hazard mitigation plans.

Table 5: Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) and HMGP Post-Fire Wildfire-related Projects and Obligations, by Declaration Fiscal Year

|

Declaration Fiscal Year |

Number of Wildfire-related Projectsa |

Total Amount Obligatedb |

|

2019 |

88 |

$41,200,000 |

|

2020 |

159 |

$54,900,000 |

|

2021 |

106 |

$14,200,000 |

|

2022 |

39 |

$300,000 |

|

2023 |

1 |

$0 |

|

Total |

393 |

$110,600,000 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑106862

Note: HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire provide grants to rebuild in a way that mitigates future natural disaster losses.

aWe considered a project wildfire-related if applicants chose a project type containing the word “wildfire” and/or if they indicated the primary hazard type for the project was fire.

bAmounts obligated are rounded to the nearest hundred thousandth, by the fiscal year the FMAG or major disaster declaration was approved, and as of the end of October 2023. FEMA was in the process of making obligations for declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and may continue to make obligations in future years for those declarations. Additionally, FEMA may de-obligate funds, especially at the end of the process. As a result, obligated amounts will change over time.

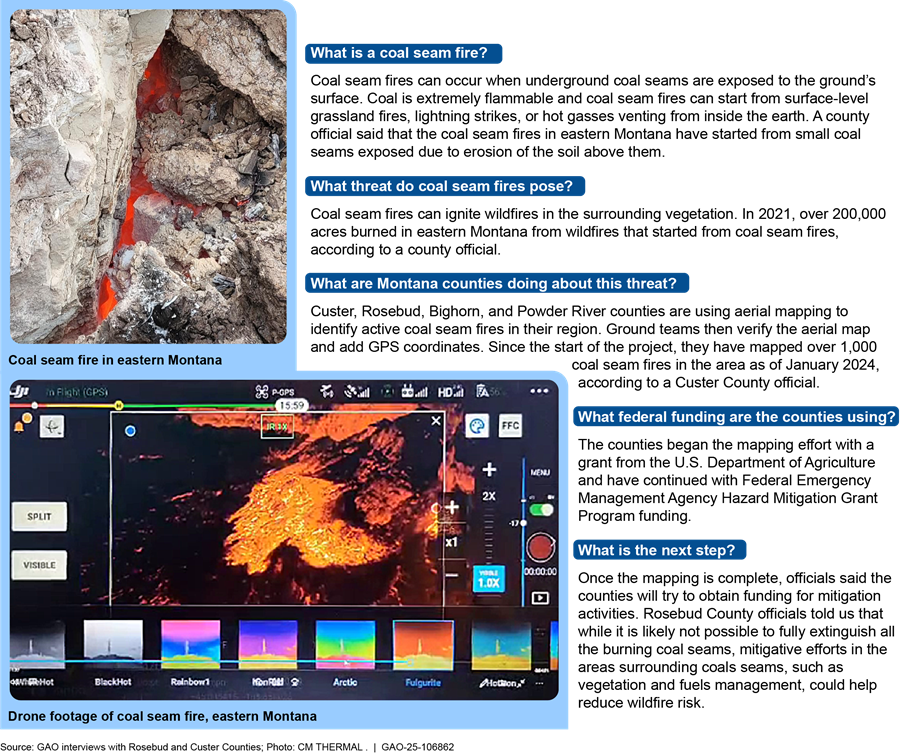

According to our data analysis and interviews with county and tribal officials, applicants used HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire for wildfire mitigation projects such as: purchasing generators, updating multi-hazard mitigation plans, conducting vegetation management, protecting public utilities, establishing warning systems, and replacing or repairing culverts and cisterns. One county we interviewed in Montana joined a multi-county effort to map coal seam fires—a growing wildfire threat—using their state’s HMGP award under the state’s COVID-19 major disaster declaration, as described in figure 7.

Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities. FEMA obligated over $12 million for wildfire-related projects through the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program’s fiscal year 2020 through 2022 funding cycles.[36] FEMA obligated more than half of these funds (about $6.4 million) for 50 wildfire-related capability and capacity building projects, such as updating hazard mitigation plans and developing building codes and standards to improve community resilience. As of the end of fiscal year 2023, FEMA had obligated about $5.8 million for two wildfire mitigations projects selected during the fiscal year 2020 application cycle, as shown in table 6.

Table 6: Number of Projects and Amounts Obligated to Wildfire-related Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities Projects, by Funding Cycle Fiscal Year

|

Funding cycle fiscal year |

Capability and capacity building projects |

Mitigation projects |

||

|

Number of projects with obligated funds |

Amount obligated |

Number of projects |

Amount obligated |

|

|

2020 |

32 |

$2,920,000 |

2 |

$5,790,000 |

|

2021 |

16 |

$2,800,000 |

0 |

$0 |

|

2022 |

2 |

$630,000 |

0 |

$0 |

|

Total |

50 |

$6,350,000 |

2 |

$5,790,000 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑106862

Notes: Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities is an annual hazard mitigation grant program designed to reduce risks from disasters and natural hazards. Obligations data are as of the end of fiscal year 2023 and are rounded to the nearest ten thousand. FEMA was in the process of making obligations for projects approved in the fiscal year 2020 through 2022 funding cycles and may continue to make obligations in future years for those projects. Additionally, FEMA may de-obligate funds, especially at the end of the process. As a result, obligated amounts will change over time. In our analysis, wildfire-related projects are those for which the applicant selected “fire” as a primary, secondary, or tertiary hazard type.

|

Selected Wildfire Mitigation Techniques · Ignition-resistant construction: using non-combustible or ignition-resistant materials, technologies, and techniques on new and existing buildings and structures. This is also called home hardening when used for residential structures. · Defensible space: creating a perimeter around a building or structure by removing or reducing the amount of flammable vegetation. · Fuels reduction: removing or modifying vegetative fuels near structures, such as by thinning vegetation or replacing flammable vegetation with fire-resistant vegetation. · Post-wildfire flooding prevention: measures to protect property from flooding, debris flows, and mudslides due to soil damage from wildfires. Examples include soil stabilization, reforestation, seeding, erosion control, and debris traps and drainage systems. Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency and California Department of Forestry and Fire Prevention documentation. | GAO‑25‑106862 |

The two wildfire mitigation projects focus on altering the built environment, such as protective measures for homes and other infrastructure:

· FEMA obligated over $5.7 million to a wildfire mitigation project in Sonoma County, California. According to the project description, the project is intended to increase community resilience to wildfires through implementing home hardening with ignition-resistant construction, defensible space, and hazardous fuels reduction techniques. See sidebar for descriptions of selected wildfire mitigation techniques.

· FEMA obligated about $65,000 for a project that will apply fire retardant mesh to over 1,000 electric poles in Butte and South Custer counties, Idaho, to mitigate wildfire threats to the electrical distribution system.

FEMA Has Not Fully Addressed the Challenges Communities Face in Obtaining Wildfire Assistance

FEMA has begun some efforts to address long-standing wildfire assistance challenges, but it is too soon to assess their impact. Additionally, the agency does not have an assistance program that enables communities to conduct immediate post-wildfire mitigation and has not fully pursued opportunities to facilitate more timely environmental reviews for post-wildfire mitigation. FEMA could also do more to identify and address FMAG program-related challenges. For example, state, county, and tribal officials we interviewed described challenges associated with the FMAG program, but FEMA headquarters does not collect ongoing, nationwide feedback from all FMAG recipients.[37] FEMA also has not clarified FMAG guidance on (1) requesting FMAG declarations for fires burning on federal land but threatening nearby communities or (2) receiving reimbursement for costs associated with pre-positioning of in-state resources. Lastly, officials that we spoke to said Tribes’ access to FMAG assistance is limited because tribal governments can only request FMAG declarations through a state.

FEMA Has Taken Some Steps to Address Long-Standing Challenges Providing Wildfire Assistance

Timeliness and Administrative Burdens

State, county, and tribal officials that we interviewed described challenges with timeliness—including in FEMA’s application decisions and reimbursements—and administrative burdens when obtaining FEMA assistance. Officials from nine out of 11 counties, all four Tribes, and all seven states we spoke to described timeliness as a challenge in one or more of FEMA’s assistance programs. These challenges related to the timeliness of FEMA application decisions and reimbursements.

Application Decisions. The time it takes for FEMA to review and either approve or deny projects may discourage some communities from applying for FEMA assistance. Per regulation, applicants are not allowed to begin HMGP or HMGP Post-Fire projects until FEMA approves them.[38] One county official said he had applied for seven HMGP Post-Fire grants since 2019 totaling about $4.6 million. The proposed projects involved reducing hazardous fuels, thinning vegetation, and creating defensible spaces. The official said that as of January 2024, FEMA had not made a determination for any of these projects, preventing the county from starting them. The official added that the county is reluctant to apply for additional projects because it could not implement all the projects if they are approved at the same time. Officials from another county said that they were awaiting FEMA approval to replace generators under the HMGP Post-Fire program more than 3 years after a 2020 wildfire. Our data analysis found that about 44 percent (108 of 247) of wildfire-related HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire project applications from declarations approved in fiscal years 2019 or 2020 were in a pending status—meaning the projects were in various stages of review—as of October 2023.

Reimbursements. Officials also brought up concerns about timeliness of reimbursements with multiple FEMA assistance programs, such as Public Assistance. For example, officials in one county stated that as of September 2023, they had not received reimbursements for a project they applied for after a 2020 wildfire. Additionally, we found that FEMA had made obligations for two of the 27 wildfire mitigation projects initially selected in the fiscal year 2020 through 2022 Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities funding cycles as of the end of fiscal year 2023.[39] Both projects were selected in the fiscal year 2020 funding cycle. As of the end of fiscal year 2023, FEMA had not made obligations for any mitigation projects selected in the fiscal year 2021 or 2022 funding cycles. The Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission’s 2023 report (Commission report) also noted that delays in reimbursements can deter local entities and Tribes from deploying resources to assist in response, as doing so risks straining their budgets and going into deficit for months or years until receiving reimbursement.[40]

Some officials noted the connection between timeliness and administrative burdens, stating that issues with FEMA’s timeliness in providing assistance resulted in further administrative burdens and costs. Officials from eight out of 11 counties, three out of four Tribes, and all seven states we spoke to described one or more of the previously described FEMA assistance programs as administratively burdensome.[41] In particular, they noted repeated requests for information and having to redo required assessments. For example, a county official said FEMA submitted requests for information multiple times over a 2-year period for the county’s HMGP Post-Fire project, creating additional and duplicative work. Officials from one FEMA region said that continuous requests for information can be challenging for applicants and that it is important to reach understanding on the project needs at the start of the process.

Additionally, officials from three counties we spoke with said the length of FEMA’s review for proposed HMGP project applications required them to redo and resubmit all or parts of their application as circumstances or requirements changed.[42] The Commission report also stated that the time-intensive and burdensome processes involved with FEMA disaster relief and hazard mitigation can contribute to protracted timelines in deploying important recovery funding to communities in need.[43]

We have previously reported on challenges communities faced using FEMA programs for hazard mitigation, including for wildfires.[44] For example, in February 2021, we reported on challenges state and local officials faced when applying for FEMA hazard mitigation grants, including complexity and length of the applications.[45] We recommended that FEMA take steps to reduce the complexity of its hazard mitigation grant programs. In response to this recommendation, FEMA reported taking actions to allow applicants to apply for funding more easily and reduce award time frames. As a result of these actions, this recommendation was closed as implemented.

FEMA officials described recent actions and ongoing initiatives to provide assistance more quickly and reduce administrative burdens for some of its assistance programs.

· FEMA made more projects eligible to follow a streamlined process and began providing additional technical assistance to reduce administrative burdens and time frames for its Public Assistance program. In August 2022, FEMA increased the threshold of small projects—which have fewer requirements than large projects—from about $140,000 to $1 million.[46] FEMA also aimed to reduce the administrative burden for small projects by streamlining requirements. For example, FEMA now accepts the applicant’s certifications for estimates of damages and work, instead of requiring full or detailed documentation. Additionally, FEMA hired a research firm to study opportunities for streamlining Public Assistance. In response to this study, in March 2024 FEMA officials stated they initiated a pilot program to provide additional technical assistance for projects that FEMA identifies as more complicated or that impact underserved communities.

· FEMA officials stated that they conducted analyses of HMGP and the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities programs to identify and address timeliness concerns. As of July 2024, the agency was in the process of reviewing those analyses and developing plans to address their findings, according to officials. Officials said FEMA also has working groups focused on improving its delivery of assistance for wildfires, including one tasked with evaluating recommendations from recent assessments of FEMA’s wildfire assistance, such as the Commission report. As of November 2024, officials stated they are using these recommendations to inform ongoing policy updates across FEMA’s hazard mitigation assistance programs.

· FEMA has solicited and incorporated feedback from applicants and recipients of Public Assistance and Individual Assistance to improve program delivery. For example, under FEMA’s strategic plan, the agency tracks the percentage of applicants satisfied with the simplicity of Public Assistance and the Individuals and Households Program, a major component of Individual Assistance.[47] Officials said these surveys inform FEMA’s policies and strategies. For example, a FEMA press release stated that it made the March 2024 Individual Assistance program changes in response to decades of survivor feedback, and requests from state partners and members of Congress for simpler programs for disaster survivors. Among these changes, FEMA removed a requirement that survivors apply for a U.S. Small Business Administration disaster loan before being considered for certain types of financial assistance from FEMA.[48] Previously, FEMA required that survivors apply for these loans and either be denied or continue to have unmet needs before receiving assistance for personal property and other non-housing losses. We have reported that survivors experienced significant confusion over this prior requirement.[49]

These recent and ongoing efforts demonstrate that FEMA is aware of timeliness issues and administrative burdens in these assistance programs and is working to address them. While these recent efforts are positive steps, it is too early to assess their impact on reducing administrative burdens and increasing timeliness of reimbursements for wildfire-affected communities.

Debris Removal

As we have previously reported, wildfires create significant debris removal challenges for state and local jurisdictions, and the process is often more costly and complicated than for other types of disasters.[50] As our data analysis indicates, FEMA obligated a higher proportion of Public Assistance funds for debris removal for wildfires than non-wildfires during fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Wildfire debris, including hazardous waste removal and private property debris, continues to pose challenges for federal, state, and local officials. For example, figure 8 describes the complicated nature of debris removal state and federal officials reported after the August 2023 Lahaina wildfire on the island of Maui, Hawaii, due to the volume of debris and presence of hazardous materials.

aPer FEMA policy, private property debris removal may be eligible for Public Assistance if the debris on private property is of such magnitude that it poses a threat to public health and safety. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is the lead agency for the emergency support function for public works and engineering, which includes debris removal.

bSee GAO, Household Hazardous Waste Removal: EPA Should Develop a Formal Lessons Learned Process for Its Disaster Response, GAO‑22‑104276 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 17, 2022).

FEMA issued two guidance memos in 2022 to address debris removal issues, which may help wildfire-affected communities recover more quickly. In September 2022, FEMA issued a memo simplifying Public Assistance policies on debris removal and utility restoration.[51] The changes were aimed at providing additional flexibility in how localities can carry out that work. Additionally, in October 2022, FEMA issued the Public Assistance Wildfire Policy Guidance Memorandum, which addressed issues related to debris and hazardous tree removal, among other things.[52] One provision of this memo established that entities do not need permission from FEMA to start private property debris removal; however, FEMA must determine the work is eligible for Public Assistance. While FEMA made these changes in response to wildfire debris challenges, the provisions are applicable to all hazards.

FEMA officials told us in November 2024 that they plan to continue working on debris removal issues over the next year. For example, officials said they plan to devise formulas that applicants can use to estimate debris removal volume, which may enable applicants to provide required information to FEMA more easily. While FEMA’s ongoing efforts are positive steps, it is too soon to assess how effective these changes will be at addressing existing wildfire debris removal challenges.

Post-Wildfire Housing

Providing effective and affordable temporary and interim housing for disaster survivors is a long-standing challenge, particularly following wildfires. Wildfires tend to totally destroy structures and leave behind contaminated ground, limiting short-term and interim housing options and requiring a longer rebuilding period. Until the land is safe for habitation, FEMA, state, and local officials must find space for temporary housing units outside the burn zone, where there is access to non-contaminated utilities.

FEMA officials also said they face limitations to their authorities regarding housing. Under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act), FEMA may provide temporary housing for up to 18 months, unless an extension would be in the public interest due

|

Post-Wildfire Housing in Maui, Hawaii Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) officials said finding housing for Maui wildfire survivors would be a top priority and a major challenge during recovery. The August 2023 wildfires damaged or destroyed nearly 2,000 housing structures in the town of Lahaina. The state of Hawaii had declared a housing emergency in July 2023 to help address the housing crisis across the state. Additionally, Hawaii had the highest cost of living of any state in 2022, according to data from the Council for Community and Economic Research. Maui also has a large short-term vacation rental market, which has limited available housing options for survivors. Further, FEMA Region 9 officials told us that Maui County prohibits housing units with wheels. This prevented FEMA from using mobile homes or trailers, its usual temporary housing units. In May 2024, FEMA Region 9 officials said they considered factors such as speed of housing availability, cost, and the effect on longer-term housing when identifying interim housing options. FEMA has primarily used Direct Leasing to house eligible survivors in Maui, according to these officials. Officials said Direct Lease is faster than other options and can help keep eligible survivors closer to their communities. Officials said it was initially difficult to obtain enough Direct Lease properties to meet demand, so Hawaii offered tax breaks to incentivize landlords to convert their vacation rentals into longer-term rentals for eligible survivors. Additionally, FEMA coordinated with other federal, state, and local authorities to evaluate potential sites for constructing Alternative Temporary Transportable Housing Units, or modular units. Officials stated that these alternative units do not have much precedence, as FEMA usually relies on trailers and manufactured homes. As of July 1, 2024, FEMA had obligated $301.3 million and expended $125.6 million in Individual Assistance for this disaster, according to FEMA officials. Source: GAO interviews with FEMA and Maui County documentation. | GAO‑25‑106862 |

to extraordinary circumstances.[53] FEMA officials said 18 months is not feasible for acute wildfires because of the total destruction and levels of trauma caused. Additionally, disasters exacerbate pre-disaster shortages of affordable housing, which is particularly challenging for communities lacking ample rental properties outside the footprint of the wildfire.[54] The 2023 wildfires in Maui exemplify these challenges; see sidebar.

FEMA has taken some initial steps to improve its assistance to survivors and address post-disaster housing challenges for all hazards, including wildfires.

· Direct Housing Implementation Teams. In October 2023, FEMA officials told us they were developing full-time Direct Housing Implementation Teams that will be dedicated to planning, permitting, and mobilizing temporary housing units for disaster declarations. Prior to establishing permanent teams focused on housing, FEMA generally deployed FEMA reservists, or on-call staff members, to perform these tasks for a given disaster. As of November 2024, FEMA was in the process of hiring staff to fill two national-level teams and teams in Regions 4 and 9. Some staff had onboarded and started training or pre-planning activities. According to FEMA, staff already hired for this effort for the national-level teams and Region 4 team were supporting disaster housing efforts in response to Hurricanes Helene and Milton. Additionally, FEMA was working to finalize updates to its Direct Housing Guide and develop standard operating procedures for the Direct Housing Implementation Teams.

· Pre-Disaster Housing Initiative. In November 2023, FEMA and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development completed a Pre-Disaster Housing Initiative pilot with four states that emphasized advanced planning for post-disaster sheltering and housing needs. Over the 6-month pilot, FEMA, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and state partners met regularly, according to a FEMA bulletin. The bulletin stated that the pilot improved coordination and collaboration across interstate organizations on the critical issues facing emergency management and housing. FEMA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development publicly released a joint report and additional guidance based on this pilot in July 2024.[55] FEMA stated that a second cohort of states will engage with FEMA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development to boost their housing recovery capabilities. FEMA officials said that state capacity may limit the number of states able to participate in the initiative because states face competing priorities and may not have enough resources to participate.

· Updates to Individual Assistance. FEMA updated its Individual Assistance program for disasters declared on or after March 22, 2024. These updates aim to provide quicker access to needed funds, expanded eligibility for property and home repairs, and an easier application process for survivors.[56]

While FEMA’s ongoing efforts are positive steps, it is too early to assess to what extent they will improve FEMA’s delivery of post-wildfire housing. FEMA officials also emphasized that state and local governments have a responsibility to better plan how they will house wildfire survivors before a disaster. Further, FEMA officials recognized that state capacity varies, with some having limited ability to participate in pre-disaster planning initiatives, such as the pre-disaster housing pilot program. The Commission report also made recommendations and, over the last few years, members of Congress have introduced legislation to address post-wildfire housing issues.

Some of FEMA’s Current Processes Hinder Post-Wildfire Mitigation Efforts

FEMA Does Not Have a Program for Immediate Post-Wildfire Mitigation

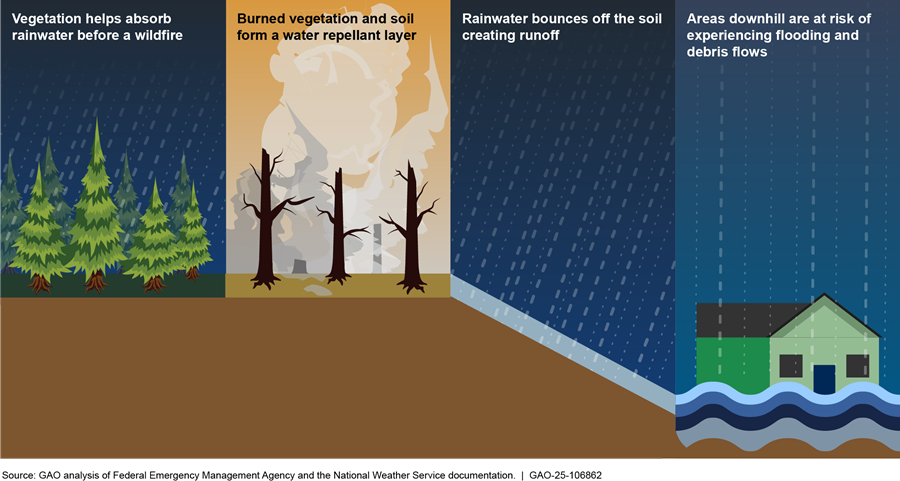

FEMA does not have an assistance program that enables communities to conduct more timely post-wildfire mitigation, which could help prevent future disasters by addressing wildfire impacts on vegetation and soil conditions.[57] Wildfires destroy vegetation and damage soil, and fires that burn at high severity can also produce water repellant soils. If not addressed quickly, this can make landscapes susceptible to flooding, erosion, and debris flows—fast-moving landslides that destroy objects in their paths and often strike without warning, as shown in figure 9. These issues can negatively affect life and property on land downstream by reducing water quality, damaging roads, and threatening homes and other structures. Proactively engaging in mitigation activities such as soil stabilization and erosion control measures, including reseeding and planting, can help communities reduce downstream risks that could lead to another disaster.

|

FEMA Hazard Mitigation Assistance Eligible Soil Stabilization and Erosion Control Activities Post-wildfire flooding prevention and sediment reduction measures: · Reforestation, restoration, and/or soil stabilization · Ground cover vegetation re-reestablishment (e.g., seeding and mulching) · Erosion prevention measures on slopes · Prevention measures for flash flooding resulting from runoff (e.g., drainage dips and debris traps) These activities are eligible for Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), HMGP Post-Fire, and Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities assistance, subject to meeting other grant requirements. Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) documentation. | GAO‑25‑106862 |

FEMA officials said that its existing mitigation programs as currently designed; including HMGP, HMGP Post-Fire, and the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program; are not the right tools for immediate post-fire mitigation. These programs allow for post-fire mitigation activities (see sidebar), but they have established lifecycles and time frames associated with pre-award, award, and post-award requirements. These timelines are not conducive to supporting mitigation efforts after wildfires, which are uniquely time-sensitive and have a high annual probability of recurrence in certain places, according to FEMA officials. As discussed previously, our data analysis for the HMGP and Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities programs indicated that it can take years for projects to move from application to reimbursement.

Additionally, 35 percent of HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire projects associated with wildfire declarations were for wildfire-related mitigation activities. Officials from two states and National Emergency Management Association members that we spoke to stated that it is difficult to use HMGP and HMGP Post-Fire assistance for post-wildfire mitigation, such as reseeding, because the program does not provide assistance in time. Officials from one of these states said that jurisdictions within their state therefore frequently use HMGP Post-Fire funds for projects unrelated to wildfires. An official from the other state said funding for wildfire mitigation is needed but participation in HMGP for wildfire-related projects will continue to be low unless FEMA provides assistance more quickly.

To address this gap, FEMA could evaluate various options, such as changing one of its existing mitigation assistance programs or establishing a new program. For example, the Commission report and FEMA’s National Advisory Council recommended expanding the support available through the FMAG program to allow for post-wildfire mitigation. According to FEMA officials, doing so would require statutory and regulatory changes to reimburse most soil stabilization activities.

FMAG authorities for providing post-wildfire mitigation are limited under statute and regulation, according to FEMA officials. The Stafford Act authorizes FEMA to provide assistance for the “mitigation, management, and control” of wildfires that may become major disasters.[58] FEMA regulations define “mitigation, management, and control” to mean activities undertaken, generally during the incident period of a declared fire, to minimize immediate adverse effects and to manage and control the fire.[59] Further, FEMA regulations state that costs related to recovery activities—such as seeding, planting operations, and erosion control—are ineligible for reimbursement.[60] However, soil stabilization and erosion control measures to prevent flooding, erosion, and debris flows are often needed after a fire no longer poses a threat.

The Commission report suggested that expanding FMAG authorities beyond the current focus on fire management and control would help address the significant need for post-fire mitigation and recovery funding. Proactively conducting post-wildfire mitigation activities can help communities reduce downstream risks that could lead to another disaster.

The National Disaster Recovery Framework states that successful recovery upholds the values of timeliness and flexibility in coordinating and efficiently conducting recovery activities and delivering assistance.[61] It also minimizes delays and lost opportunities. Further, it ensures recovery plans, programs, policies, and practices are adaptable to meet unforeseen, unmet, and evolving recovery needs. Additionally, the National Mitigation Framework calls for reducing long-term vulnerability.[62] This consists of building and sustaining resilient systems, communities, and critical infrastructure and key resource lifelines to reduce their vulnerability to threats and hazards by lessening the likelihood, severity, and duration of the adverse consequences. It also includes initiatives and investments that reduce response and recovery resource requirements in the wake of a disaster or incident.

FEMA officials stated that they have considered some options for how current programs could be used for this purpose, but regulatory and/or statutory barriers have prevented the agency from taking further action. As the lead federal agency for disaster recovery, FEMA is best positioned to identify ways to address this gap, which may include modifying an existing program or establishing a new program. Such changes may necessitate amending FEMA regulations and/or developing a legislative proposal for any necessary statutory changes, depending on which option FEMA pursues. Taking steps to provide immediate post-wildfire mitigation assistance could better position FEMA to help foster more resilient communities and reduce the future demand on federal resources by mitigating post-wildfire flooding, erosion, and debris flows.

Opportunities Exist to Facilitate More Timely Environmental Reviews for Post-Wildfire Mitigation

FEMA has pursued some, but not all, opportunities to facilitate more timely environmental reviews—required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—for mitigation projects that could reduce post-wildfire risks.[63] Officials from two counties and two states, and our prior work identified delays associated with the NEPA environmental review process.[64] The 2022 FEMA National Advisory Council Annual Report stated that environmental reviews have become lengthy for hazard mitigation assistance projects, especially for pre- and post- wildfire mitigation.[65] Improving the efficiency of the environmental review process for post-wildfire mitigation projects is also important in facilitating more timely post-wildfire mitigation assistance.

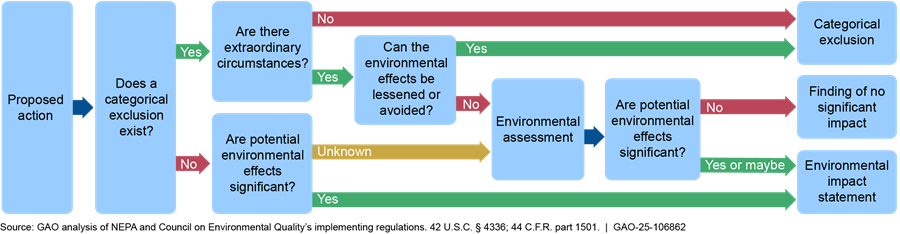

Assistance provided via FEMA’s hazard mitigation assistance programs is subject to NEPA, which requires federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of proposed major federal actions prior to making decisions.[66] Those effects include impacts on social, cultural, economic, and natural resources.[67] Agencies must determine whether an environmental assessment or environmental impact statement is required to assess the project’s effects on the quality of the human environment.[68] Agencies are also to establish categorical exclusions in their NEPA implementing procedures.[69] These are categories of actions that normally do not have significant effect on the human environment, individually or in the aggregate. If a proposed action is covered by an agency’s categorical exclusion, it generally does not require preparing an environmental assessment or environmental impact statement. Agencies are still required to assess whether there are extraordinary circumstances that may cause a proposed action to have a significant effect and warrant further environmental review, as shown in figure 10.[70]

Notes: Categorical exclusions are categories of actions that normally do not have significant effect on the human environment and are incorporated into agencies’ NEPA implementing regulations and procedures. Agencies are still required to assess whether there are extraordinary circumstances that may cause a proposed action to have a significant effect and warrant further environmental review. 40 C.F.R. 1501.4. For example, extraordinary circumstances could be related to the presence of threatened or endangered species. Environmental assessments are prepared for actions not likely to have a significant effect or for which the significance of the effects is unknown and are used to support an agency’s determination of whether to prepare an environmental impact statement or a finding of no significant impact. Environmental impact statements are prepared for actions likely to have significant effects and contain detailed analyses and evaluations of the impacts of a proposed project and reasonable alternatives to the proposed action. 44 C.F.R. part 1501.

To establish categorical exclusions, agencies submit substantiation packages with proposed or revised categorical exclusions to the Council on Environmental Quality, which oversees agencies’ NEPA implementation.[71] In their proposal, agencies must demonstrate that the set of actions under consideration do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment. For example, agencies may assess the environmental effects of previously implemented or ongoing actions, such as through prior environmental assessments that consistently found no significant impacts. Agencies may also substantiate a categorical exclusion based on another agency’s experience with a comparable categorical exclusion and the record developed by the other agency when establishing the categorical exclusion.[72] In consultation with the Council on Environmental Quality, agencies publish their proposed categorical exclusions for public comment and then incorporate them into their NEPA procedures.

Other assessments of FEMA’s programs and processes have identified categorical exclusions as a potential method to increase the timeliness and efficiency of environmental reviews for wildfire mitigation actions. For example, the 2022 National Advisory Council report attributed lengthy time frames for environmental reviews, particularly for wildfire mitigation, as often due to the lack of applicable categorical exclusions, requiring environmental assessments that can take years to complete.[73] Additionally, the Commission report recommended that FEMA expand an existing categorical exclusion or establish a new one that would cover post-wildfire mitigation activities such as soil stabilization and erosion control.[74] Lastly, three of the seven states we interviewed told us it would be helpful for FEMA to have a categorical exclusion for more wildfire mitigation projects.

DHS establishes categorical exclusions that apply to FEMA and other DHS components. There are several paths DHS could take to pursue a categorical exclusion for post-wildfire soil stabilization activities, including following the process to establish a new categorical exclusion, expand an existing one, or adopt one from another agency:

Establishing a new categorical exclusion. DHS could pursue establishing a new categorical exclusion to cover post-wildfire mitigation activities based on the findings of past environmental assessments. For example, since late 2019, FEMA has developed at least four programmatic environmental assessments that found no significant environmental impacts for a range of post-wildfire soil stabilization mitigation actions eligible for FEMA assistance.[75] The findings in these assessments, as well as project specific assessments for past soil stabilization and erosion control projects, may help support a new categorical exclusion.

Expanding an existing categorical exclusion. DHS could pursue expanding an existing categorical exclusion to include these post-wildfire mitigation activities. For example, the Commission report recommended that DHS could expand its categorical exclusion for “federal assistance for planting of indigenous vegetation” to include post-wildfire soil stabilization and erosion control activities.

Adopting another agency’s categorical exclusion. Other federal agencies, such as the U.S. Forest Service, the Department of the Interior, and the Bureau of Land Management, have categorical exclusions that cover certain soil stabilization activities after a wildfire. The Council on Environmental Quality’s NEPA regulations, amended in May 2024, provide the option for agencies to adopt and apply another agency’s categorical exclusion to a proposed action or a category of actions.[76] Therefore, DHS could pursue adopting the categorical exclusion of one of these other agencies.

FEMA officials agree that a categorical exclusion for post-wildfire soil stabilization and erosion control activities would be beneficial, and the agency has begun to assess its options for adopting a categorical exclusion from another agency to cover such activities. FEMA officials said they have identified several categorical exclusions related to post-wildfire soil stabilization at other agencies, and the agency is currently evaluating the feasibility of adopting them. To do so, as stated in regulation, DHS will need to work with the agency that established the categorical exclusion and follow the process to adopt and apply the categorical exclusion to a proposed action or category of actions.[77] DHS officials said that the department is pursuing the option to adopt another federal agency’s categorical exclusion because the process is the most streamlined method for expanding the department’s available categorical exclusions.

The Council on Environmental Quality recommends that agencies anticipating long-term use of an adopted categorical exclusion establish the categorical exclusion in their own NEPA procedures. As such, adopting and applying another agency’s categorical exclusion to a category of actions could be a good interim solution until an agency establishes a new categorical exclusion or modifies an existing one.[78]