IMMIGRATION COURTS

Actions Needed to Track and Report Noncitizens’ Hearing Appearances

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106867. For more information, contact Rebecca Gambler at (202) 512-8777 or GamblerR@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106867, a report to congressional requesters

Actions Needed to Track and Report Noncitizens' Hearing Appearances

Why GAO Did This Study

Each year, EOIR issues hundreds of thousands of decisions for cases involving noncitizens charged as removable under U.S. immigration law. As of July 2024, EOIR reported a backlog of nearly 3.5 million pending cases.

GAO was asked to review EOIR’s data on in absentia removal orders. This report examines (1) the extent to which EOIR tracks respondent hearing appearances, and (2) EOIR data related to in absentia removal orders, among other objectives.

GAO analyzed EOIR documentation and data on immigration court removal cases that were opened or pending at any point from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023. This analysis comprised the in absentia rates for non-detained respondents and various respondent characteristics, including legal representation status. GAO interviewed EOIR officials and made virtual and in-person site visits to five immigration courts selected based on various factors, such as a range of in absentia rates. During these visits, GAO interviewed government officials (e.g., immigration judges) and nongovernmental stakeholders (e.g., private bar attorneys) to obtain their views on respondent hearing appearances, among other things.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to EOIR to collect and publicly report data on respondent hearing appearances. EOIR concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

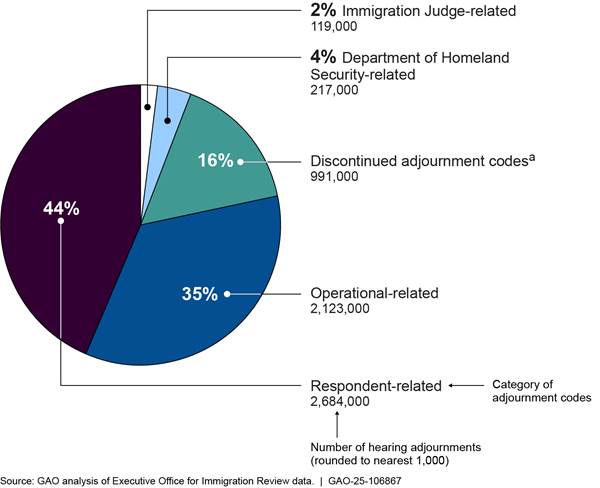

The Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is responsible for conducting immigration court proceedings. If a respondent—a noncitizen who has been charged with violating immigration law—fails to appear for any of their hearings, an immigration judge may order them removed from the country in their absence (“in absentia”). A judge may also waive their appearance and otherwise resolve the case, depending on the facts and circumstances. However, EOIR does not track or report data on whether respondents appear at their hearings or whether their appearance was waived, because EOIR’s case management system does not have a function to systematically record such information. EOIR officials stated that the system has other information that could indicate whether respondents appeared at hearings, such as data on in absentia removal orders and certain hearing adjournment codes. However, these data do not reliably track respondents’ appearance at hearings. Developing and implementing a function in its system and publicly reporting on that data would better position EOIR to provide reliable information to Congress and others about the extent respondents appear for their hearings.

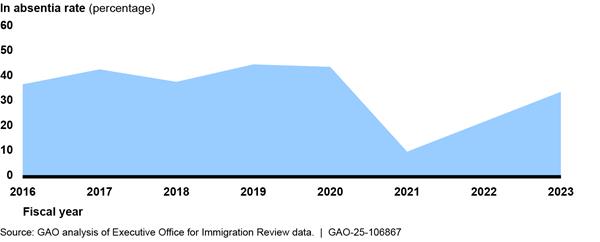

According to EOIR data, from fiscal years 2016 through 2023, the total in absentia rate was 34 percent for removal cases of non-detained respondents. EOIR calculates the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders by the number of immigration judges’ initial decisions resolving cases. The rate varied by certain characteristics, such as court location, legal representation status, and demographic characteristics.

Note: The fiscal year 2021 decrease in the rate may be associated with factors such as fewer hearings because of the COVID-19 pandemic and higher legal representation rates.

Government officials and stakeholders stated that respondents may not appear for their court hearings for a variety of reasons, such as language barriers, not having transportation to court, or respondents choosing not to go to court because they fear that they will be detained upon appearing at their hearing.

Abbreviations

|

CASE |

Case Access System for the Executive Office for Immigration Review |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

EOIR |

Executive Office for Immigration Review |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

INA |

Immigration and Nationality Act |

|

OPLA |

Office of the Principal Legal Advisor |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 19, 2024

The Honorable Ron Johnson

Ranking Member

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Chairman

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

Each year, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) initiates hundreds of thousands of removal cases with the U.S. immigration court system.[1] The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is responsible for conducting immigration court proceedings and other activities to administer and interpret U.S. immigration laws and regulations fairly, expeditiously, and uniformly. As of July 2024, EOIR reported a backlog of nearly 3.5 million pending cases—more than seven times the number of pending cases at the beginning of fiscal year 2015, which we noted in our prior work.[2] We have previously reported that the effects of this backlog are significant and wide-ranging, including some respondents waiting years to have their cases heard and immigration judges having less time to consider cases.[3] We have also made recommendations to improve EOIR’s management practices, including its workforce planning and data quality practices, and EOIR has implemented some of those recommendations.[4]

EOIR’s immigration judges preside over hearings to decide whether noncitizen respondents—foreign nationals charged as removable for violating immigration law—are removable as charged and, if so, may be granted any requested protection or other relief to lawfully remain in the U.S.[5] If a respondent fails to appear for any of their hearings, the immigration judge may order them removed from the country “in absentia” (i.e., in the respondent’s absence), unless the judge has previously waived the respondent’s appearance.

You asked us to review EOIR’s data on in absentia removal orders and case processing times. This report examines (1) the extent to which EOIR tracks respondent hearing appearances, and what perspectives government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders have on factors that affect respondent appearances; (2) EOIR data related to in absentia removal orders; and (3) EOIR data about case processing times.

To address all three objectives, we analyzed EOIR data from its case management system on immigration court removal cases that were opened or pending from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023.[6] We selected this time frame to cover the period since our previous report in which we analyzed EOIR data on cases through the last full fiscal year of data available at the time of our review.[7] We assessed the reliability of these data through electronic tests and discussions with EOIR officials. Based on this analysis, we removed about 65,000 cases from the data (about 1 percent of the entire dataset).[8] We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing (1) hearing adjournments, (2) in absentia removal orders, and (3) case processing times.

To determine the extent to which EOIR tracks respondent hearing appearances, we reviewed EOIR’s process to assess the extent to which relevant fields in EOIR’s case management system—such as judges’ notes, adjournment codes, and in absentia removal orders—track respondent appearances. We also interviewed EOIR officials and judges during our five site visits to immigration courts, as described below, about the steps EOIR takes to collect information related to respondent appearances at court. We compared this information against the principles in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government related to using quality information and communicating externally.[9] We also assessed EOIR’s process against Office of Management and Budget guidance related to information quality assurance.[10]

To examine EOIR data related to in absentia removal orders, we analyzed in absentia removal orders for initial case completions of removal cases from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023.[11] We limited our analysis to data for non-detained respondents because in absentia removal orders for detained respondents were outside the scope of our review.[12] We calculated the rates of in absentia removal orders out of initial case completions by immigration court location and respondent characteristics (legal representation status, family cases placed on special dockets, nationality, and language, among other characteristics).

To examine EOIR data about case processing times, we analyzed case processing times for removal cases EOIR received from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023. We calculated the processing time for several milestones of a case, including the time between the start of a removal case and the initial case completion and the time between selected hearings. We further analyzed how three factors were related to case processing times: (1) the respondent’s custody status (i.e., detained or non-detained), (2) the respondent’s legal representation status, and (3) whether the case was on a special docket for families.[13]

In addition, we conducted a mix of virtual and in-person site visits to five immigration courts selected to reflect a range of characteristics. These characteristics included different rates of in absentia removal orders, number of initial case completions, and geographic locations. Our selection also included locations with a Legal Orientation Program for Custodians of Unaccompanied Children.[14] During these site visits, we conducted interviews with government officials and selected nongovernmental stakeholders to obtain their perspectives on respondent hearing appearances, in absentia removal orders, and case processing times.[15] We also selected six external nongovernmental stakeholders from national organizations that consist of members who are EOIR judges, attorneys participating in EOIR cases, or organizations providing services to respondents. We also selected stakeholders who had published reports or articles using empirical data on in absentia removal order rates or factors affecting respondent appearances at hearings since 2016. Appendix I provides more information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2023 to December 2024, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities within the Immigration Court System

EOIR is responsible for conducting immigration court proceedings, appellate reviews, and administrative hearings. Within EOIR, the Office of Chief Immigration Judge employs over 700 immigration judges. These judges are responsible for conducting immigration court proceedings and acting independently in deciding matters before them in 71 immigration courts and three immigration adjudication centers across the country as of August 2024.[16] As of the end of fiscal year 2023, 52 of those immigration courts have either non-detained dockets (i.e., dockets in which none of the respondents are in custody at the time of their hearings) or hybrid dockets (i.e., dockets with some respondents in custody at the time of their hearing and others are not). Immigration judges are tasked with resolving cases in a manner that is timely, impartial, and consistent with the Immigration and Nationality Act, federal regulations, and precedent decisions of the Board of Immigration Appeals and federal appellate courts. Assistant chief immigration judges serve as liaisons between EOIR’s senior leadership and the immigration courts. They also have supervisory authority over immigration judges.[17] Assistant chief immigration judges also conduct hearings and manage dockets of their own.[18]

Attorneys in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) serve as civil prosecutors representing the U.S. government in all removal proceedings before EOIR.[19] ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations is responsible for overseeing certain potentially removable noncitizens throughout their removal proceedings, including detaining certain noncitizens pending the outcome of their immigration court cases and ensuring noncitizens comply with an immigration judge’s final order of removal from the country, if appropriate.

Individuals appearing before the immigration court—respondents—may represent themselves or be represented by an attorney of their choosing, at no cost to the government.[20] The government generally does not provide legal counsel in immigration court proceedings.[21] In cases where a respondent has legal representation, the attorney may speak for the respondent, receives court documents such as hearing notices, and submits motions and evidence to the court. These private bar attorneys must be registered with the immigration court.[22]

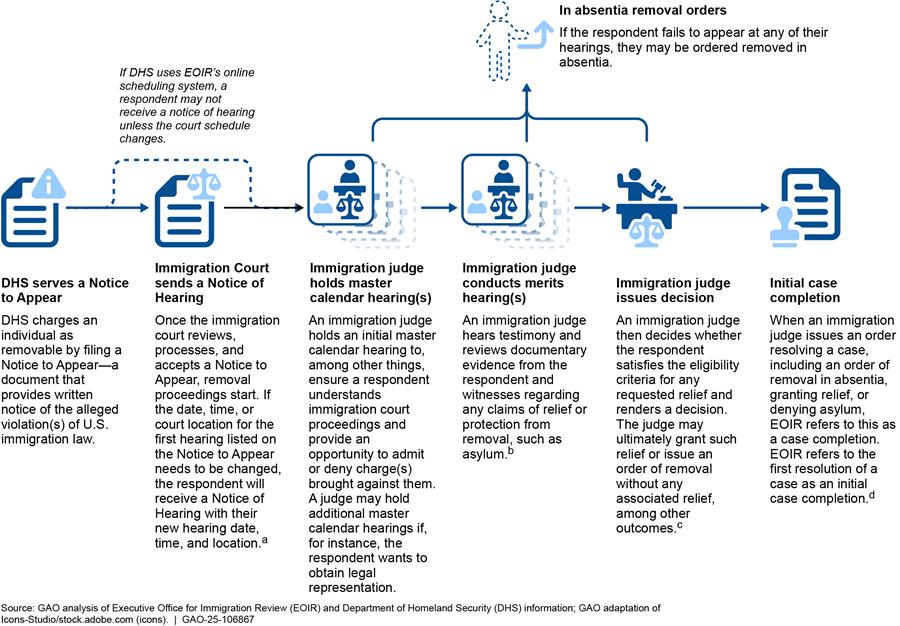

Overview of Removal Proceedings

Immigration court proceedings begin when DHS charges an individual as removable and files the “Notice to Appear,” the charging document that orders the respondent to appear before an immigration judge to respond to the charges on a date DHS selects from EOIR’s scheduling system.[23] On the Notice to Appear, DHS notes the date, time, and location the respondent must appear, records the respondent’s residential address, if any, and selects the immigration court that has geographic jurisdiction over that address. DHS transmits the notice to the appropriate immigration court, and the court enters the respondent’s mailing address and other information, such as primary language spoken and country of origin, into EOIR’s electronic case management system.[24]

Immigration court removal proceedings generally follow several steps, as shown in figure 1.[25]

aIf the date, time, or location listed on the original Notice to Appear does not change, the immigration court will not issue a hearing notice.

bU.S. immigration law provides that foreign nationals arriving or present in the country may be granted humanitarian protection in the form of asylum if they are unable or unwilling to return to their home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. See 8 U.S.C. 1158.

cUnder U.S. immigration law, a foreign national is removable if: (1) not admitted to the U.S. and found inadmissible under section 212 of the INA; or (2) admitted to the U.S. and deemed deportable under INA 237. See 8 U.S.C. 1182(a), 1227, 1229a(c), (e)(2). Those determined to be removable and not eligible for any requested relief or protection from removal would be subject to removal pursuant to the judge’s order once it is administratively final. 8 C.F.R. 1241.1

dA removal proceeding may have more than one completion. For instance, a respondent can submit a motion to reopen a case after an initial case completion, and the immigration judge may agree to reopen the case. In this example, while a judge has made an initial case completion, the case would require a second resolution to be completed. EOIR refers to any completion after the initial case completion as a subsequent case completion.

As shown in figure 1, immigration courts mail respondents a hearing notice, which includes the mode of the hearing—either video teleconference, telephone, or in person.[26] If the immigration court plans to conduct the hearing remotely, the hearing notice includes a web address for the judge’s video teleconferencing site.[27]

Respondents’ Responsibilities During Proceedings

During immigration court removal proceedings, respondents have several responsibilities:

1. Respondents must notify the court of changes to their address within 5 days.[28]

2. Respondents must also separately notify DHS of changes to their address or telephone number.[29]

3. According to the hearing notice, respondents are encouraged to confirm the time and date of hearings in case there are changes. The hearing notice lists a 1-800 number that communicates hearing and court closure information in both English and Spanish. The notice also contains a QR code that respondents may use to read the notice in 10 additional languages online.[30] Additionally, respondents may monitor changes to their hearing information through EOIR’s online respondent portal.[31]

In addition, respondents whose appearance has not been waived and fail to appear for any of their immigration court hearings may be subject to legal consequences. For instance, they may be subject to an in absentia removal order, and any applications or potential applications for relief or protection from removal may be deemed abandoned by the immigration court. Further, those who without reasonable cause fail or refuse to attend or remain in attendance at a removal proceeding and who seek admission to the U.S. within 5 years of their subsequent departure or removal, are inadmissible.[32] Those against whom a final order of removal is entered in absentia, and who receive requisite notice of consequences, are ineligible for certain forms of relief, such as adjustment to lawful permanent residence, within 10 years from the date of the final order of removal.[33]

Respondents’ Custody Status

While removal proceedings are pending, respondents may be detained in ICE custody or, if eligible for release, released on bond, conditional parole, terms of supervision, or other alternatives to detention.[34] We refer to cases where respondents are in ICE custody as detained cases. Detained respondents may request a bond redetermination hearing in which an immigration judge reviews ICE’s custody and bond decision.[35] For this report, we refer to cases involving respondents who either have never been in ICE custody or have been released from ICE custody as “non-detained cases.”[36]

EOIR Does Not Track Respondent Hearing Appearances, and Reasons Vary for Respondents Not Appearing

EOIR Does Not Systematically Track or Report on Respondents’ Appearance at Hearings

As previously noted, respondents are expected to appear for their immigration court hearings unless their appearance has been waived by an immigration judge.[37] EOIR officials stated that respondents appearing for hearings is important because it allows them to actively participate in their own claims.

However, EOIR does not track or report data on whether respondents appear at their hearings or whether their appearances were waived because EOIR’s case management system does not have a function to systematically record such information.[38] In the absence of such a function, EOIR officials stated that the agency’s case management system has other data fields that could be used to indicate whether respondents appeared at hearings, including a narrative field, an adjournment code, and in absentia removal orders. However, according to these officials, these data are not a reliable source for tracking respondent appearances. Specifically:

|

Circumstances When Immigration Judges May Waive Respondent’s Court Appearance Immigration judges and assistant chief immigration judges we interviewed identified several types of respondents for whom they may choose to waive appearances including but not limited to · Juvenile respondents after their initial master calendar hearing, so that the respondents may attend school; · Respondents who have legal representation do not need to appear at pre-hearing conferences or certain master calendar hearings; and · Respondents who face extenuating circumstances, such as illnesses or emergencies. Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑25‑106867 |

· Narrative field. EOIR’s case management system has a narrative field, which immigration judges may use to record notes about the case, including whether the respondent appeared at a hearing and whether the respondent’s appearance was waived. Judges can use these notes to determine which respondents appeared at a hearing or had their appearance waived on a case-by-case basis.[39] However, because these notes are entered in a narrative field on a case-by-case basis, EOIR cannot use them to systematically track or report on appearances across cases or to determine a rate of respondent attendance.

· Adjournment code indicating a respondent’s or legal representative’s absence. According to EOIR officials, immigration judges enter various adjournment codes in EOIR’s case management system to record reasons they adjourn hearings, but these codes do not specify if respondents appeared at the hearings.[40] In particular, EOIR’s case management system includes one adjournment code that judges can select when the hearing adjourned because either the respondent or their legal representative was absent. However, this adjournment code does not provide reliable information on whether respondents appeared for their hearing because the code can be used in either situation. Moreover, because judges can only select one adjournment code for each hearing, they may select an adjournment code unrelated to the presence or absence of respondents or their legal representative if the judges determine that another reason was the primary reason for the adjournment.

Further, in our interviews with assistant chief immigration judges and immigration judges, judges provided differing perspectives on how they used this code most often. In six of 10 interviews, judges stated that they most often used this adjournment code because the respondent was present but the respondent’s legal representative was absent. In two of 10 interviews, judges stated they most often used the code because the respondent was absent, but the respondent’s legal representative was present. In the final two of 10 interviews, judges indicated they used the code equally for both situations.

· In absentia removal orders. Through its case management system, EOIR tracks and publicly reports information on instances in which immigration judges ordered respondents who did not appear at a hearing to be removed from the country. In our previous work on EOIR’s public reporting of data, we found the agency reports immigration data to the public and external users in several ways, including by (1) reporting immigration case statistics on its public website and (2) responding to Freedom of Information Act requests.[41] Some entities have used EOIR’s publicly reported data to calculate in absentia removal order rates as a proxy for rates of respondent appearance, including as part of information provided at Congressional hearings.[42] However, in absentia removal orders cannot be used to reliably calculate rates of respondent appearance. Specifically, in absentia removal order rates only reflect closed cases; therefore, they do not include respondents who may have appeared at previous hearings but whose cases were still pending. Also, in absentia rates do not include respondents who did not appear in court because an immigration judge waived their appearance, or respondents who did not appear in court but did not receive an in absentia removal order.[43]

Further, in absentia rates do not differentiate between respondents who never appeared for court and respondents who appeared for one or more hearings but were ordered removed in absentia at a subsequent hearing.[44] Thus, recording and reporting the rate of in absentia removal orders does not provide quality information on how often respondents were present at their immigration court hearings.

Assistant chief immigration judges and EOIR senior leadership we interviewed reported benefits and drawbacks to recording and reporting respondent appearance data.

· Judges: Four of five assistant chief immigration judges we interviewed identified benefits of recording respondent appearances.[45] For example, one judge stated that EOIR could use these data to better understand the effects of nonappearances on judges’ caseloads. Further, three of the five stated they could not identify any drawbacks to EOIR recording this information. However, two judges identified drawbacks, specifically questioning whether recording this information would be resource intensive for the immigration judges.

· EOIR senior leadership: EOIR senior officials we interviewed also identified benefits of recording respondent appearances and tracking this information at an organizational level. For instance, the officials stated that EOIR would be able to conduct more precise analyses to determine if there are national trends in respondent nonappearance or differences in nonappearance at specific court locations. Such analysis could inform EOIR planning and operations. Further, tracking this type of information at an organizational level would allow EOIR to better track efficiencies or inefficiencies in immigration court operations. Tracking and reporting this information would also allow EOIR to answer questions posed by external stakeholders about respondent appearances. EOIR officials also noted potential drawbacks of collecting this information, stating that collecting appearance and waiver information would increase the amount of manual data entry required for each case and therefore increase the potential for data entry errors.

Federal internal control standards call for an agency’s management to design a process that identifies the information requirements for achieving the agency’s objectives and addresses any risks.[46] EOIR’s Strategic Plan includes an objective to manage its caseload efficiently and effectively, including by analyzing the case lifecycle to identify points of inefficiency.[47] Further, the internal control standards call for the agency’s information requirements to consider the expectations of both internal and external users. The standards call for the agency to obtain relevant data from reliable internal and external sources in a timely manner based on the identified information requirement.

Federal internal control standards also call for agencies to select appropriate methods to communicate externally—including to the President, Congress, and the general public—based on a variety of factors such as the audience, nature of information, and availability, among others.[48] In addition, Office of Management and Budget guidelines on maximizing the quality of reported data call for agencies to incorporate aspects of quality into their information management practices. These aspects of quality include utility, whether the information is useful for its intended users and purpose.[49]

EOIR senior officials stated that the agency is considering whether to add a method for noting respondents’ appearance as part of future information technology system updates, but does not have plans or time frames for making this decision. EOIR stated that they could do this by updating their current case management system. They also stated that if individual immigration judges need to know this information, they can record it on a case-by-case basis in their notes in the agency’s case management system. However, as previously discussed, senior officials also noted benefits of systematically recording this information, such as an enhanced ability to track efficiencies in court operations and improvements in information provided to customers and stakeholders. It could also provide more systematic information on respondents’ appearance beyond the information judges may record in their notes on a case-by-case basis.

By developing and implementing a function in its case management system for recording respondents’ appearances and whether appearances were waived, EOIR would be better positioned to track and report data on respondent hearing appearance and waivers. This in turn could help EOIR systematically identify and assess trends in respondents appearing or not appearing at hearings, and provide insights into the court’s caseload. Moreover, implementing such a function could help ease the burden on judges by reducing the need for judges to enter narrative information about respondents’ attendance in their case notes. For example, the system might include check boxes to indicate whether respondents appeared or had their appearance waived, rather than judges entering such information manually in the system’s narrative field. Moreover, by publicly reporting the data periodically, consistent with EOIR’s other public reporting on its caseload, the data would have greater use for external users. Congress and other external users thus would have reliable information about the extent to which respondents appear for immigration court hearings. This, in turn, may help inform Congressional oversight of immigration court activities.

Government Officials and Nongovernmental Stakeholders Identified Reasons Why Respondents May Not Appear at Court

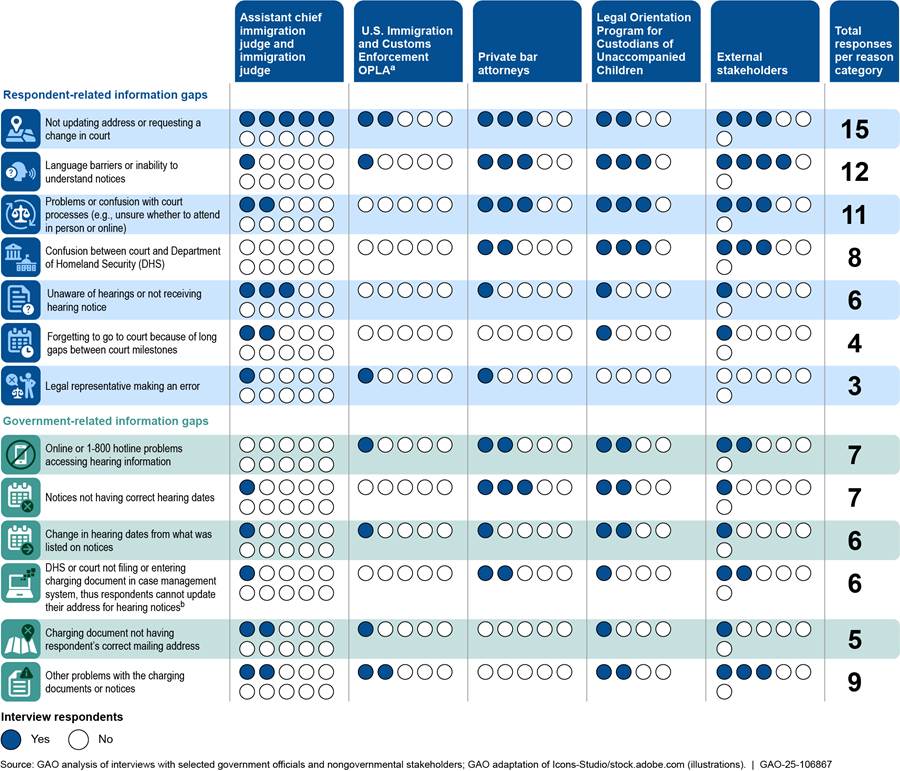

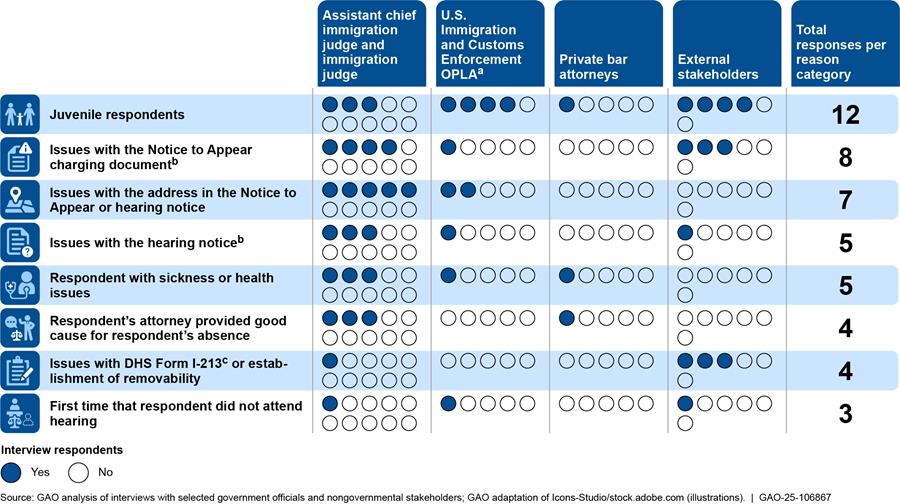

We conducted 30 interviews with government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders to obtain their perspectives on reasons for respondents not appearing at their hearings.[50] Based on their responses, we identified three general categories of reasons why respondents may not appear for hearings: (1) respondents may be limited by information gaps, (2) respondents may face logistical challenges, and (3) respondents may choose not to appear at their hearings.

Respondents may not appear at court hearings because of information gaps. As shown in figure 2, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders identified seven respondent-related and six government-related information gaps that may affect respondents’ appearances at immigration courts.

Figure 2: Information Gaps That May Affect Respondent Appearance at Immigration Court, as Identified by Selected Government Officials and Nongovernmental Stakeholders

Note: We conducted interviews of government officials and nongovernment stakeholders at five selected courts. Specifically, we interviewed assistant chief immigration judges, immigration judges, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) attorneys representing the U.S. government in immigration court, private bar attorneys representing noncitizens with cases in immigration court, and service providers of the Legal Orientation Program for Custodians of Unaccompanied Children. We also interviewed six external stakeholders such as associations representing practitioners and immigration law researchers.

aU.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement OPLA attorneys serve as civil prosecutors representing the U.S. government in all removal proceedings before the Executive Office for Immigration Review.

bAccording to Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) officials, respondents may send EOIR a change of address form before the immigration court has reviewed and accepted the Notice to Appear charging document. They stated that as soon as EOIR accepts the Notice to Appear into its case management system, the system automatically links the change of address form to the respondent’s case and updates the respondent’s address.

In general, nongovernmental stakeholders reported information gaps more often than government officials as a reason respondents may not appear for their hearings. The most-cited information gap among nongovernmental stakeholders (mentioned in 10 of 15 interviews) was language barriers or the inability to understand notices. The most often cited information gap that government officials identified (mentioned in seven out of 15 interviews) was respondents not updating their address with the courts, to ensure they receive updated information about their upcoming hearings.[51]

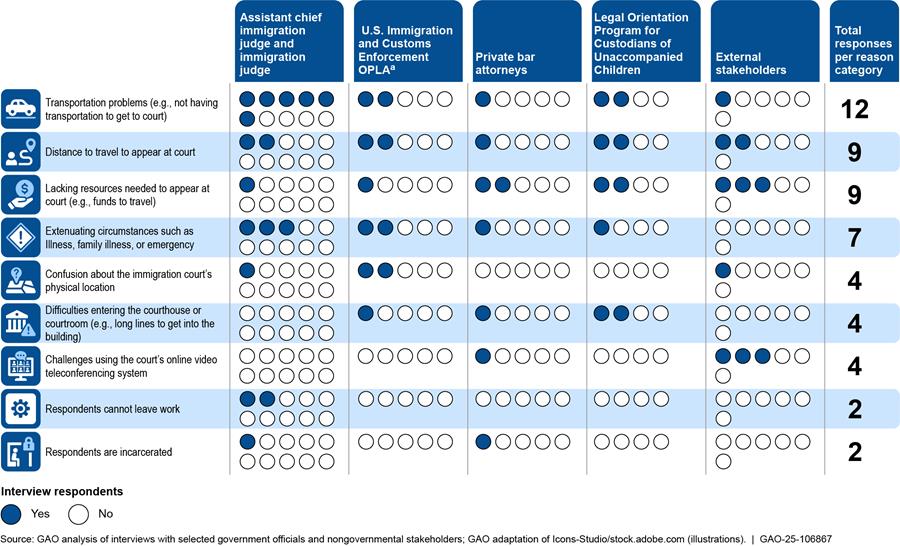

Respondents may face logistical challenges that limit appearances. Government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders identified nine different logistical challenges that may affect respondents’ appearance at court hearings, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Logistical Challenges That May Affect Respondent Appearances at Immigration Court, as Identified by Selected Government Officials and Nongovernmental Stakeholders

Note: We conducted interviews of government officials and nongovernment stakeholders at five selected courts. Specifically, we interviewed assistant chief immigration judges, immigration judges, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) attorneys representing the U.S. government in immigration court, private bar attorneys representing noncitizens with cases in immigration court, and service providers of the Legal Orientation Program for Custodians of Unaccompanied Children. We also interviewed six external stakeholders such as associations representing practitioners and immigration law researchers.

aU.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement OPLA attorneys serve as civil prosecutors representing the U.S. government in all removal proceedings before the Executive Office for Immigration Review.

While there was variation in the responses between government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders, both government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders identified logistical issues as possibly affecting respondent appearance about the same number of times. As shown in figure 3, government officials most often cited respondents having transportation problems that may make it difficult to appear for their hearings, mentioning it in eight of 15 interviews. In contrast, nongovernmental stakeholders identified respondents not having necessary resources to get to court most often as a logistical challenge, mentioning it in seven of 15 interviews.

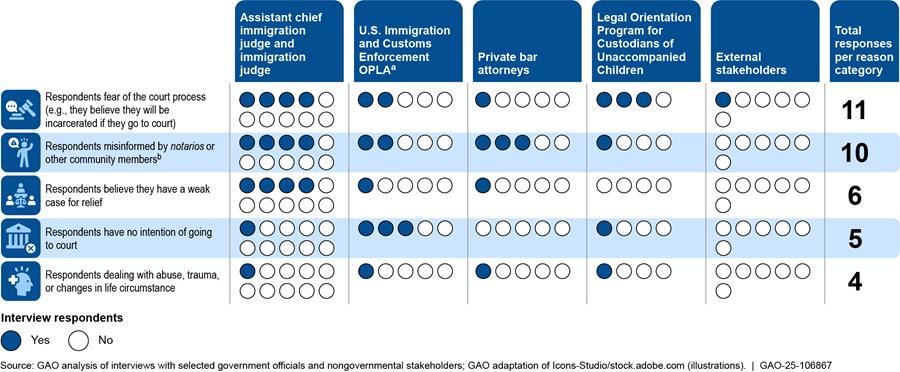

Respondents may choose not to appear at court hearings. Government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders identified five reasons respondents may choose not to appear at court hearings, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Reasons Selected Government Officials and Nongovernmental Stakeholders Attributed to Respondents Choosing Not to Appear at Immigration Court

Note: We conducted interviews of government officials and nongovernment stakeholders at five selected courts. Specifically, we interviewed assistant chief immigration judges, immigration judges, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) attorneys representing the U.S. government in immigration court, private bar attorneys representing noncitizens with cases in immigration court, and service providers of the Legal Orientation Program for Custodians of Unaccompanied Children. We also interviewed six external stakeholders such as associations representing practitioners and immigration law researchers.

aU.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement OPLA attorneys serve as civil prosecutors representing the U.S. government in all removal proceedings before the Executive Office for Immigration Review.

bIn many Spanish-speaking nations, “notarios” are attorneys with special legal credentials. In the U.S., however, notary publics are people authorized by state governments to witness the signing of important documents and to administer oaths but are not necessarily authorized to provide legal services. A notario is not authorized to provide any legal services related to immigration in the U.S.

Overall, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders cited respondents choosing not to appear at court fewer times than the other two categories previously discussed. Government officials cited respondents fear of the court process and respondents being misinformed by notarios or other community members equally as reasons why respondents may choose not to appear at court, being identified during interviews six times each in 15 interviews.[52] Nongovernmental stakeholders also identified respondents’ fear of the court process most often among the reasons, mentioning it in five of 15 interviews.

About a Third of Non-detained Respondent Initial Case Completions Resulted in In Absentia Removal Orders, and Such Orders Varied Based on Certain Factors

From fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, our analysis of EOIR data shows that the total in absentia rate for initial case completions of non-detained respondent cases was 34 percent.[53] The in absentia rate also varied by court location, legal representation status, and demographic characteristics.

About a Third of Non-detained Respondents’ Cases Completed from Fiscal Year 2016 through Fiscal Year 2023 Resulted in an In Absentia Removal Order

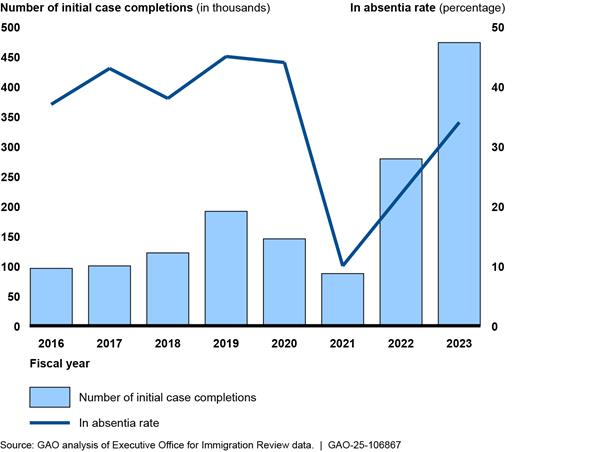

From fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, the average annual number of initial case completions for non-detained respondents was about 187,000. The number of initial case completions ranged from about 87,000 in fiscal year 2021 to about 473,000 in fiscal year 2023, as shown in figure 5. According to EOIR officials, there were fewer initial case completions in fiscal year 2021 due to court closures and hearing postponements during the COVID-19 pandemic. In fiscal year 2022 and fiscal year 2023, EOIR added new courts and increased the number of immigration judges, which increased the agency’s capacity to process cases.

Among initial case completions for non-detained respondents, the total in absentia rate from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023 was 34 percent.[54] Over this period, the in absentia rate ranged from 10 percent in fiscal year 2021 to 45 percent in fiscal year 2019, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Initial Case Completions and In Absentia Rates for Cases of Non-detained Respondents, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year.

The respondent in absentia rate decreased from 44 percent, nearly its highest rate in fiscal year 2020, to 10 percent, its lowest rate in fiscal year 2021. According to our analysis, this decrease was associated with factors such as fewer hearings because of the COVID-19 pandemic and higher legal representation rates.

· Fewer hearings in fiscal year 2021: EOIR officials told us that in absentia rates were lower in fiscal year 2021 because there were comparably fewer hearings held (about 251,000 hearings compared to a total annual average of about 770,000 hearings from fiscal years 2016 through fiscal year 2023) and fewer cases completed. EOIR officials also told us that since courts could not hold hearings during fiscal year 2021 in particular, the courts focused on cases that they determined were ready to move forward for adjudication.

· Higher legal representation rates: There were higher legal representation rates in fiscal years 2021 and 2022, 85 percent and 73 percent respectively, than in earlier fiscal years, which correlated with lower in absentia rates. The legal representation rate across initial case completions from fiscal years 2016 through 2020 was 59 percent. We discuss the link between representation rates and in absentia removal orders later in this report.

In Absentia Rates Varied by Court Location and Legal Representation Status

In Absentia Rates by Court Location

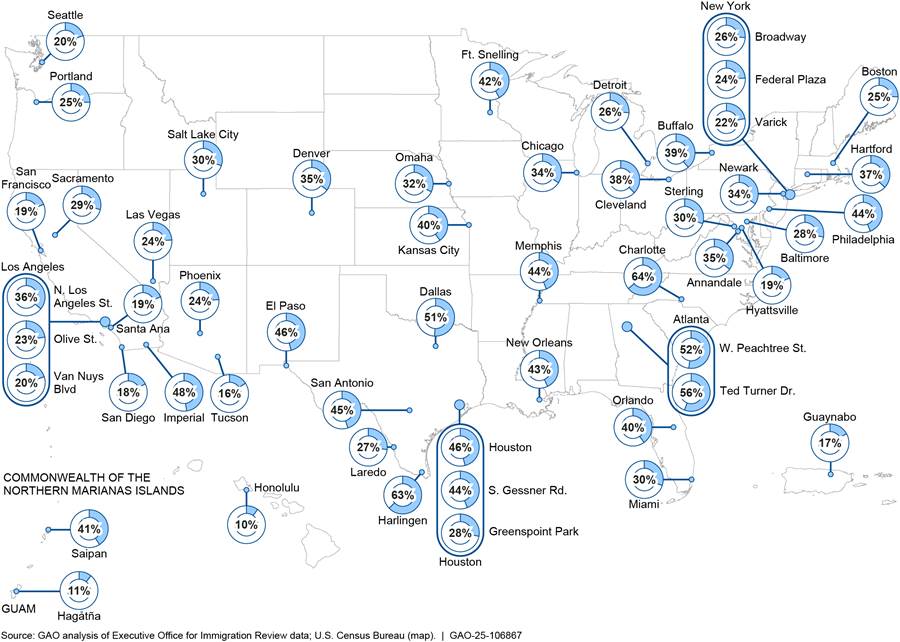

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates for non-detained cases varied by court location, ranging from 10 percent (Honolulu, Hawaii) to 64 percent (Charlotte, North Carolina) from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, as shown in figure 6.

Figure 6: Total In Absentia Rates for Non-detained Respondents by Immigration Court Location, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year. Only immigration court locations with non-detained or hybrid (both non-detained and detained) dockets are displayed in the figure. In fiscal year 2024, the Los Angeles Olive Street immigration court closed and the West Los Angeles court opened.

Based on our interviews with government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders, a court’s accessibility by public transportation and the size of the court’s geographic jurisdiction may be factors that contribute to variation of in absentia rates by court location. For example, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders from the Charlotte immigration court told us in three interviews that the court has jurisdiction for both North Carolina and South Carolina—a large geographic area. Further, one nongovernmental stakeholder told us it could be difficult for respondents who are traveling from one state to another to use public transportation to appear at court, particularly for hearings scheduled to start in the early morning.

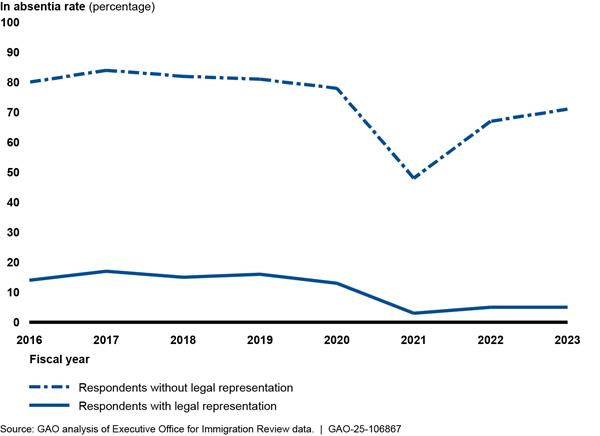

In Absentia Rates by Legal Representation

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates for non-detained cases varied by whether the respondent had legal representation.[55] The total in absentia rate was 9 percent for non-detained respondents’ cases with legal representation and 75 percent for those without legal representation from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: In Absentia Rates for Non-detained Respondents Based on Legal Representation, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year. We considered a respondent to have legal representation if they had legal representation at any point in their case.

Government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders told us in 12 of 30 interviews we conducted that legal representation increases the likelihood that respondents will appear for their immigration court hearings. Private bar attorneys we interviewed shared several practices when representing respondents in immigration court that may help their clients appear for their hearings. For example, in three out of five interviews with private bar attorneys, they told us that they remind their clients about upcoming hearings and inform them of the consequences of not appearing. Further, private bar attorneys told us in four interviews that their clients never or rarely missed court hearings.

Our statistical analysis showed that respondents with legal representation had 97 percent lower odds of receiving an in absentia removal order for their initial case completion.[56] We found similar association even when we accounted for four factors described later in this report —court location, placement on a special family docket, respondent’s nationality, and language.

However, these data do not necessarily indicate a causal relationship between legal representation and in absentia orders. There may be other factors that independently affect both legal representation and in absentia orders. For example, five government officials, including two assistant chief immigration judges and two immigration judges, told us that respondents who have strong cases for asylum may be more likely to appear for their hearings. Similarly, respondents who have strong cases for asylum may also be more likely to obtain legal representation. One private bar attorney told us that she only chooses to represent respondents who have a strong case for asylum.

In Absentia Rates Varied by Respondent Demographic Characteristics

In Absentia Rates of Families on Special Dockets

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates varied for non-detained cases placed on special dockets for families. As shown in table 1, DHS had three different initiatives to prioritize, expedite, and track family unit cases from fiscal year 2014 to fiscal year 2021. From fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2017, DHS tracked family cases for two different dockets: adults with children released on alternatives to detention and adults with children who were detained. From fiscal year 2019 through March 2020, DHS tracked family unit cases. On May 28, 2021, DHS and DOJ announced the current family docket initiative. This docket, known as the dedicated docket, processes recently arrived families that meet certain criteria.[57] EOIR scheduled master calendar and merits hearings for these cases on an expedited timeline compared to cases not on any special docket.

Table 1: In Absentia Rates for Non-detained Respondents Placed in Special Dockets for Family Unit Cases, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

|

Special docket |

Respondents who were prioritized in the docket |

Expected completion or scheduled hearing time |

Fiscal years active |

Number of initial case completions |

In absentia rate (percent)a |

|

Dedicated docket |

Family units who were apprehended between ports of entry, placed in removal proceedings, enrolled in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Alternatives to Detention Program, and reside in one of 11 designated citiesb,c |

Completion within 300 days of the initial master calendar hearing |

2021 – Present |

54,465 |

31 |

|

Family unit cases |

Family units placed in removal proceedings and whose cases were filed by the Department of Homeland Security in one of 10 designated immigration court locationsb |

Completion within one year of EOIR’s receipt of the case |

2019 – 2020 |

73,228 |

67 |

|

Adults with children -alternatives to detention |

Adults and their children placed in ICE’s Alternatives to Detention Programc |

Scheduling of the initial master calendar hearing within 28 days of EOIR’s receipt of the case |

2014 – 2017 |

23,503d |

65d |

|

Adults with children-detainede |

Adults and their children who were formerly detained but later released |

Scheduling of a master calendar hearing within 28 days of respondent’s release from custody |

2014 – 2017 |

2,116d |

62d |

|

No special docketf |

N/A |

N/A |

2016 – 2023 |

1,224,521 |

32 |

N/A = Not applicable

Source: GAO analysis of Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) documentation and data. | GAO‑25‑106867

aWe calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year.

bDHS defines a family unit as a non-U.S. citizen child or children under the age of eighteen accompanied by their non-U.S. citizen parent(s) or legal guardian(s).

cICE oversees the Alternatives to Detention Program to ensure compliance with release conditions and provides case management services for non-detained noncitizens.

dFor the adults with children-alternatives to detention and adults with children-detained dockets, the number of initial case completions and the in absentia rate may not include all cases that were active during the entire duration of the dockets. It only includes cases that were completed from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023.

eWe included cases in which the respondent was originally detained and then later released among the non-detained cases.

fThe “No Special Docket” category includes all

respondents who were not placed in any special docket for family units. This

could include single adults and unaccompanied juveniles.

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that cases placed on special family dockets from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2020 had about double the in absentia rates as cases not placed on any special docket. However, from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2023, in absentia rates were about the same for cases on the dedicated docket and those not placed on any special docket.

Nongovernmental stakeholders told us in two interviews that families placed on the dedicated docket face various challenges because of the docket’s expedited time frames. One stakeholder noted that families on the dedicated docket may receive less advance notice for their hearings due to the expedited nature of the dedicated docket. Government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders told us in four interviews that families on the dedicated docket may have challenges obtaining and working with an attorney due to the expedited time frames.

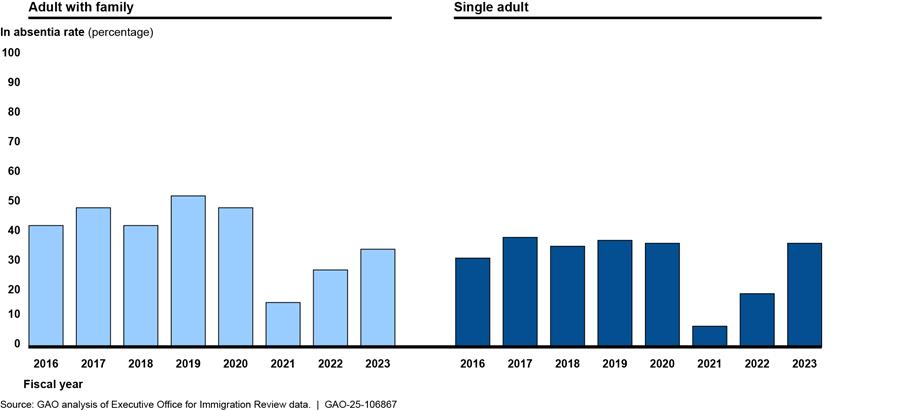

In Absentia Rates for Adults with Family Relationships and Juvenile Status

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates varied based on whether non-detained adults also had other family members in immigration proceedings.[58] Figure 8 shows that adults with family relationships generally had higher in absentia rates than single adults. Stakeholders we interviewed cited several potential reasons for these higher rates. Nongovernmental stakeholders told us in three interviews that families with children may face challenges, such as finding childcare in order to appear for their court hearing.[59] In addition, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders told us in two interviews that the expedited nature of the dedicated docket provides families with less time to save money to afford an attorney.

Figure 8: In Absentia Rates for Non-detained Adult Respondents with and without Family Relationships, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year. We used Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) data to identify cases of adults, which, according to EOIR officials, are tracked in EOIR’s case management system as individuals aged 21 and over who are also not designated as unaccompanied juveniles. According to EOIR officials, there could be respondents who are age 21 and over who remain designated as unaccompanied juveniles because they were eligible for benefits such as the Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, through U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. We then used EOIR’s data on “leads and riders” to identify adults with family relationships and compared them to single adults without family relationships. According to EOIR officials, immigration judges may link or join individual respondents’ cases together based on familial relationships if they have separate but overlapping circumstances or claims for relief, and move to consolidate their cases. These individuals may have a variety of familial relationships such as two spouses, a parent and a child, or an uncle and a nephew. Our analysis also shows that the in absentia rates for both (1) adults with family and (2) single adults without family relationships generally reflect the trends of the overall in absentia rate, with the notable decrease in fiscal year 2021.

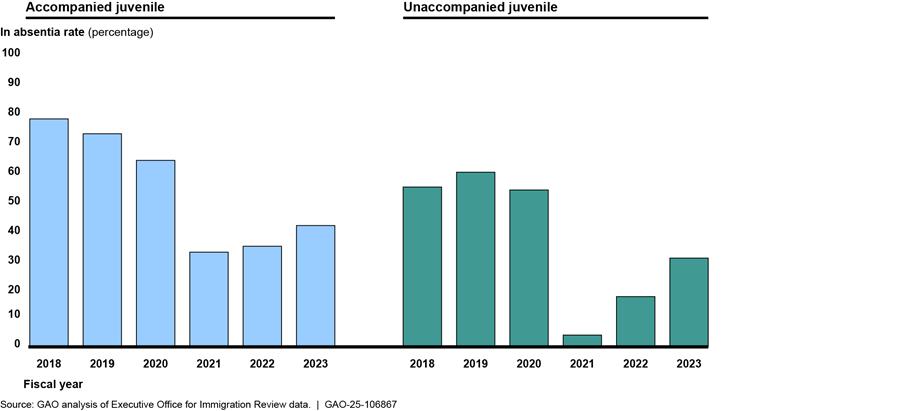

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates also varied between accompanied juveniles and unaccompanied juveniles.[60] The in absentia rates for accompanied juveniles from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2023 were higher than the in absentia rates for unaccompanied juveniles, as shown in figure 9. Four government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders we interviewed told us that immigration judges are more likely to grant continuances at the first master calendar hearing than issue in absentia orders for unaccompanied juveniles, which may partly explain the higher in absentia rates for accompanied juveniles. Accompanied juveniles’ cases are often heard at the same time as their family members’ cases. However, their appearance is often waived in order for them to attend school and immigration judges require the appearance of an adult family member or a legal representative in their place, according to our interviews. One nongovernmental stakeholder said this may result in an in absentia removal order for the accompanied juvenile if the adult family member does not appear for their hearing.

Figure 9: In Absentia Rates for Accompanied Juveniles and Unaccompanied Juveniles, Fiscal Years 2018 through 2023

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year. We analyzed data from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2023 because EOIR did not start tracking both accompanied juveniles and unaccompanied juveniles until fiscal year 2018.

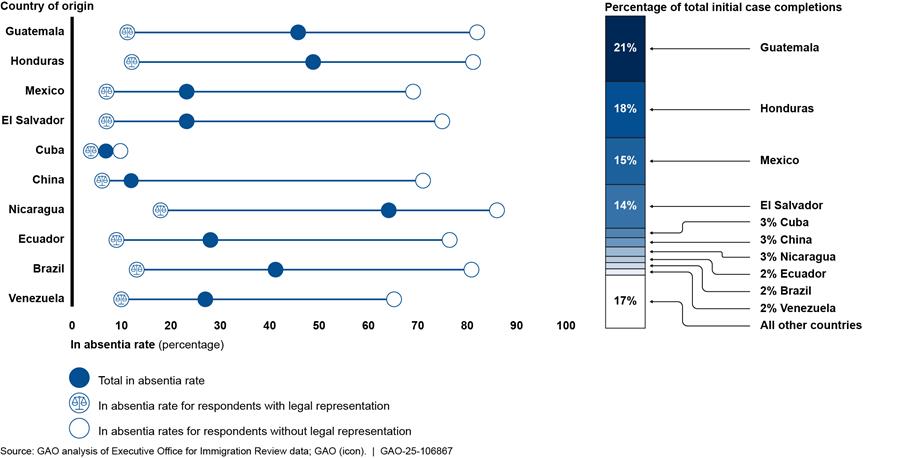

In Absentia Rates by Nationality

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates varied by the respondents’ nationality. Across the 10 countries with the highest volume of initial case completions across fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, the in absentia rates ranged from 7 percent for respondents from Cuba to 64 percent for respondents from Nicaragua. Within the top 10 countries with the most initial case completions, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and El Salvador collectively made up about two-thirds of non-detained initial case completions.[61] Respondents from Guatemala and Honduras had in absentia rates of 46 percent and 49 percent, respectively, while respondents from Mexico and El Salvador both had in absentia rates of 23 percent.

Respondents from Cuba and China had notably lower total in absentia rates, 7 percent and 12 percent respectively, as shown in figure 10. For Chinese respondents, the lower in absentia rate could be related to a high rate of legal representation, as 92 percent of respondents from China were represented during this time period. In absentia rates for all nationalities were lower for respondents with legal representation and higher for respondents without legal representation. As described earlier in the report, stakeholders told us that legal representation helps to increase respondent appearances at their immigration court hearings. For respondents from Cuba, one government official told us that Cuban respondents are more likely to appear for their hearings to establish eligibility to apply to become lawful permanent residents under the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966.[62]

Figure 10: In Absentia Rates for Non-detained Respondents by Top 10 Countries of Origin with the Highest Number of Initial Case Completions, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023a

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year.

aThe name for the data field we used for this

analysis in EOIR’s case management system is nationality. However, the data

presented in the data field are country names, indicating the country of

origin.

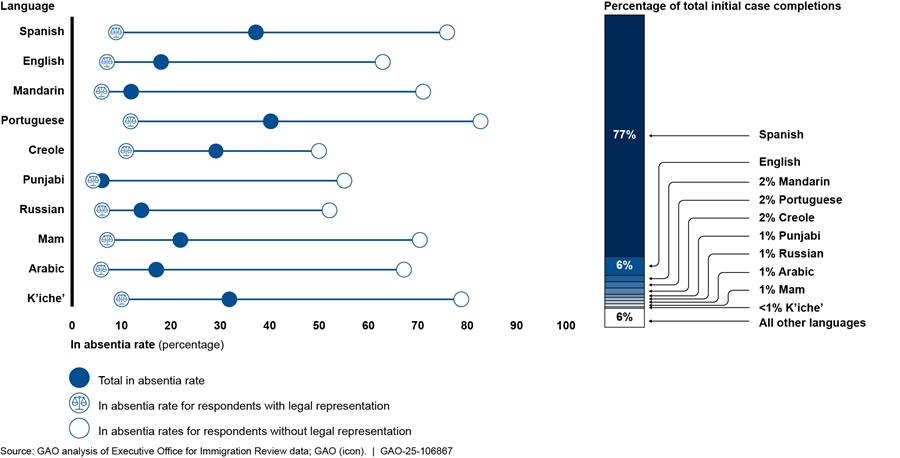

In Absentia Rates by Language

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that in absentia rates varied by the language that respondents best spoke and understood.[63] The in absentia rates for the top 10 languages with the highest number of initial case completions across fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023 ranged from 6 percent for Punjabi speakers to 40 percent for Portuguese speakers, as shown in figure 11. Our analysis showed that Spanish was most frequently cited as the language best spoken and understood by respondents, representing 77 percent of all initial case completions. The total in absentia rate for respondents who best spoke and understood Spanish was among the highest, about 37 percent. In 12 interviews we conducted with government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders, they told us that language barriers or the respondents’ inability to understand immigration court notices or charging documents may be reasons why respondents miss their hearings, which could result in them receiving an in absentia removal order.

Figure 11: In Absentia Rates for Non-detained Respondents by Top 10 Languages with the Highest Number of Initial Case Completions, Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

Note: We calculated the in absentia rate by dividing the number of in absentia removal orders issued by the total number of initial case completions in a fiscal year.

aMam and K’iche’ are indigenous languages that belong to the Mayan linguistic family. Mam is the Spanish name of the language and is known as Qyool among native speakers.

In absentia rates for all languages we analyzed were lower for respondents with legal representation and higher for respondents without legal representation. For example, respondents who spoke Mandarin, Punjabi, and Russian had the three lowest overall in absentia rates. This could partly be explained by high legal representation rates for the three groups: Mandarin (92 percent), Punjabi (97 percent), and Russian (83 percent).

Respondents May File Motions to Reopen Cases with In Absentia Removal Orders, and Immigration Judges Grant the Majority of Such Motions

After receiving an in absentia removal order, respondents can submit a motion to reopen their case by providing the reason they did not appear at their hearing, which immigration judges may grant or deny.[64] From fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, 11 percent of about 504,000 non-detained cases initially resolved by an in absentia removal order had a motion to reopen. Among cases that had motions to reopen, immigration judges granted the motion for 81 percent of cases. In total, from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, about 47,000 out of about 504,000 initial case completions that had an in absentia removal order were reopened, or 9 percent.

Case Processing Times Varied by Custody and Legal Representation Status

Detained Respondents’ Cases Were Completed Faster Than Non-detained Respondents’ Cases

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that EOIR received about 3.9 million new cases from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, and the processing time for these cases varied by the custody status (i.e., detained or non-detained). Cases with detained respondents, which historically have been an EOIR priority, had faster initial case completion times than cases with non-detained respondents. In addition, detained respondents’ cases also reached the milestones within a case, such as the master calendar and merits hearing, faster than non-detained respondents’ cases.

Initial Case Completion

A greater proportion of detained cases had an initial case completion within the time frame of our analysis than non-detained cases.[65] Our analysis shows that about one-third of the 3.9 million cases EOIR received from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023 also had an initial case completion during that time. Specifically, EOIR received about 347,000 detained respondents’ cases and about 343,000 detained respondents’ cases had an initial case completion. EOIR also received about 3.5 million non-detained respondents’ cases, and about 1.1 million non-detained respondents’ cases had an initial case completion from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023.

The median case processing time—the median length of time from the start of a case to an initial case completion—varied by the custody status of the respondent.[66] Across the completed cases that EOIR received from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, the median case processing time was 394 days, according to our analysis.[67] However, the median case processing time for detained respondents’ cases was 52 days, and for non-detained respondents’ cases, it was 625 days. Processing times for detained respondents’ cases varied less than processing times for non-detained respondents’ cases across fiscal years.[68]

As shown in table 2, the median case processing time also varied by the fiscal year of completion. For detained respondents, the median case processing time varied from 39 days in fiscal year 2018 to 92 days in fiscal year 2020.[69] For non-detained respondents, it varied from 239 days in fiscal year 2017 to 1,051 days in fiscal year 2021.

Table 2: Median Number of Days from Start of Case to Initial Case Completion, by Custody Status and Fiscal Year of Completion, Cases Received from Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

|

|

|

Median number of days from case start to initial completion |

||||||

|

Custody status |

Number of initial case completionsa |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023b |

|

Detained |

342,977 |

40 |

39 |

52 |

92 |

50 |

50 |

47 |

|

Non-detainedc |

1,123,002 |

239 |

420 |

355 |

332 |

1,051 |

1,036 |

846 |

Source: GAO analysis of EOIR data. | GAO‑25‑106867

aTotal cases include removal cases that the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) received from fiscal years 2016 through 2023 and had an initial case completion during that time. About 11,000 detained cases and 2.4 million non-detained cases did not have an initial case completion by the end of fiscal year 2023. The number of detained cases with and without an initial case completion do not equal the total number of cases received because the custody status of a case receipt and an initial case completion may differ. Data for cases received in fiscal year 2016 reflected only cases EOIR received and completed in one fiscal year, resulting in artificially lower case processing times, compared to other fiscal years in our analysis. Therefore, we did not include the median number of days from case start to initial case completion for completions that occurred in fiscal year 2016.

bThe median number of days from the start of a case to initial case completion in fiscal year 2023 may be lower than prior years, particularly for non-detained cases, because cases starting in later fiscal years had less time to finish, and only those cases completing within the shorter time contributed to the median.

cWe included cases in which the respondent was originally detained and then later released among the non-detained cases.

EOIR officials told us that the median case processing time can vary each fiscal year depending on the custody status of the respondent and the composition of completed cases, among other factors. In addition, EOIR makes decisions about how to prioritize its pending caseload, which can affect the composition—that is, the number of old and new cases—completed each year, and therefore also affect case processing times. For example, EOIR officials told us that many of the cases with an initial completion in fiscal year 2022 were older cases that had a longer case completion time. Further, they told us that the median case processing time decreased in fiscal year 2023 due, in part, to EOIR prioritizing newer cases.

Our analysis of EOIR data found that the length of time to initial case completion varied across fiscal years. Specifically, we calculated the percent of cases that initially completed within 1 to 7 years, separately for cases starting in fiscal years 2016 through 2022, as shown in table 3. We found that the less than 1-year initial completion rates decreased from the first 4 fiscal years to the last 3 fiscal years in our analysis, suggesting that processing times have slowed in recent years. For example, cases starting in fiscal year 2019 had a 24 percent chance of initially completing within 1 year, compared to a 5 to 12 percent chance among cases starting in fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2022.

Table 3: Cumulative Percent of Non-detained Cases Completed within up to 7 Years from Case Start to Initial Case Completion, by Fiscal Year of Case Start, 2016 through 2022

|

|

|

Cumulative percent of cases with an initial case completionb |

||||||

|

Fiscal year of case starta |

Total cases started in fiscal year |

< 1 year |

< 2 years |

< 3 years |

< 4 years |

< 5 years |

< 6 years |

< 7 years |

|

2016 |

181,893 |

18% |

31% |

43% |

52% |

56% |

64% |

74% |

|

2017 |

233,851 |

14% |

27% |

39% |

43% |

52% |

65% |

— |

|

2018 |

253,193 |

15% |

29% |

32% |

41% |

56% |

— |

— |

|

2019 |

462,958 |

24% |

27% |

35% |

50% |

— |

— |

— |

|

2020c |

313,294 |

5% |

10% |

26% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2021c |

248,803 |

9% |

28% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2022 |

731,653 |

12% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Legend:

< = Less than

— = Not available because cases that started in the fiscal year did not have a full year of data available for the calculation.

Source: GAO analysis of Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) data. | GAO‑25‑106867

aWe consider the case start to be either the date EOIR accepts the charging document (i.e., the Notice to Appear) from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) or the date DHS uses EOIR’s electronic case system to schedule the initial master calendar hearing for the purposes of issuing a Notice to Appear to a respondent.

bThe cumulative percent of cases is the percent of cases that started in a fiscal year and had an initial case completion within the applicable length of time. We did not calculate all lengths of time for cases that started in each fiscal year because we did not have a full year of data available for the calculation. For example, cases that started in April 2021 would require data through April 2024 for the calculation up to 3 years. As a result, each successive row has one fewer year of data available. We analyzed data for removal cases that started from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2022. We did not include cases that started in fiscal year 2023 because one full year of data was not available for the calculation.

cEOIR officials told us that immigration courts held fewer hearings during fiscal years 2020 and 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Master Calendar and Merits Hearings

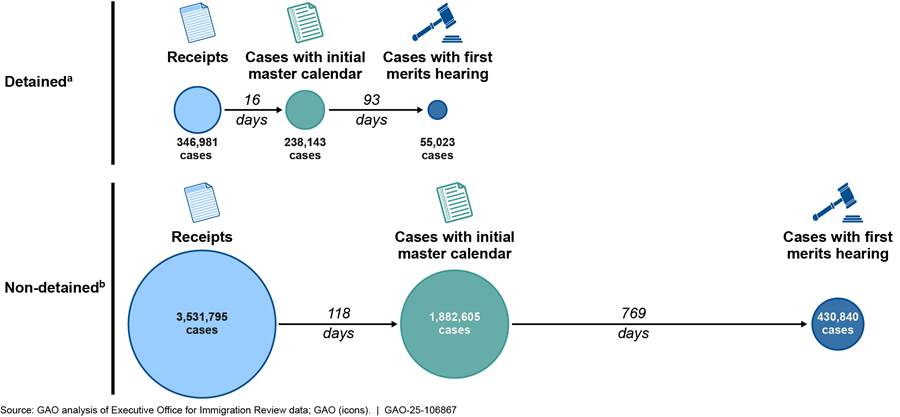

Similar to the initial case completion times, detained respondents’ cases took a shorter amount of time to reach the milestones within a case than non-detained respondents’ cases, according to our analysis of data on cases EOIR received from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023. Across these fiscal years, the median number of days from the start of a case to the initial master calendar hearing and the first merits hearing was shorter for detained respondents’ cases than non-detained respondents’ cases. These data include both cases with an initial case completion and cases that are pending (i.e., cases for which an immigration judge has not yet rendered a decision) as of the end of fiscal year 2023. As shown in figure 12, the median number of days it took detained respondents’ cases to reach the initial master calendar hearing was 16 days and the median number of days from the initial master calendar hearing to the first merits hearing was 93 days.[70] In contrast, the median number of days non-detained respondents’ cases took to reach the initial master calendar hearing was 118 days, about 4 months, and from that hearing to the first merits hearing was 769 days, about 2 years.[71]

Figure 12: Median Case Processing Times from the Initial Master Calendar Hearing to the First Merits Hearing, by Custody Status, Cases Received from Fiscal Years 2016 Through 2023

aWe analyzed removal cases that the Executive Office for Immigration Review received from fiscal years 2016 through 2023. Of the detained cases, 342,977 had an initial case completion. The cases that do not have an initial case completion (i.e., pending cases) may have a master calendar hearing or merits hearing scheduled to take place in fiscal year 2024 or later.

bOf the non-detained cases, 1,123,002 had an initial case completion. A case, including those with an initial case completion, may not have an initial master calendar hearing or a merits hearing. For example, if an immigration judge issues an in absentia removal order at the master calendar hearing, that case would be completed without a merits hearing.

An initial case completion may occur without having a master calendar hearing or a merits hearing, such as when judges complete cases by issuing an in absentia removal order.[72] For example, if an immigration judge issues an in absentia removal order at the master calendar hearing, that case would be completed without a merits hearing. Our analysis of EOIR data shows that about 40 percent of in absentia removal orders in fiscal year 2021 occurred at the master calendar hearing. In fiscal year 2022, the percentage remained the same, about 40 percent. In fiscal year 2023, about 48 percent of in absentia removal orders in that fiscal year occurred at the master calendar hearing.

In addition, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders told us in 18 of 24 interviews we conducted (including nine of 10 interviews with judges) that respondents miss the initial master calendar hearing more often than they miss other hearings.[73] For example, one assistant chief immigration judge told us that respondents may not attend their initial master calendar hearing for several reasons, such as the respondent not knowing they had a hearing.[74] Further, another assistant chief immigration judge told us that respondents who appear at their initial master calendar hearing typically continue to appear for additional hearings until the final merits hearing. In four of the 24 interviews, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders told us that they could not identify a pattern regarding at which type of hearing respondents most often do not appear.

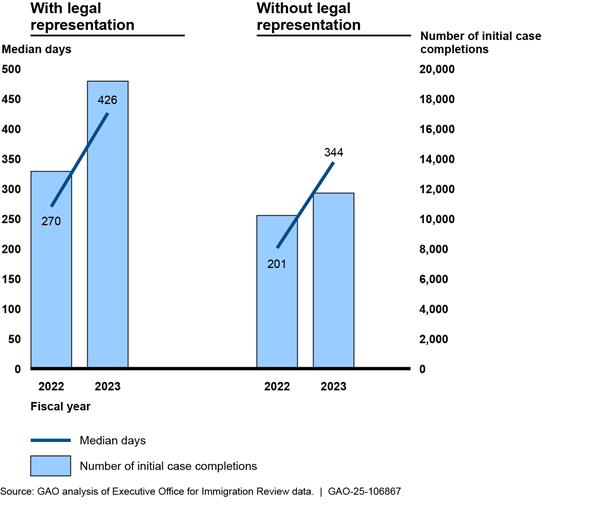

Cases with Legal Representation Had Longer Processing Times Than Cases Without Legal Representation

Cases with legal representation at any point in the case had longer initial case completion times than those without legal representation, according to our analysis of EOIR data.[75] Cases with legal representation generally reached the initial master calendar hearing faster than cases without legal representation and took longer to reach the first merits hearing than cases without legal representation.[76]

Initial Case Completion

Our analysis of EOIR data shows that the median case processing time was longer for respondents with legal representation and shorter for respondents without legal representation. For example, across cases that had an initial case completion from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, non-detained respondents with representation took 976 median days, about 2.7 years, from the start of the case to the initial case completion.[77] In contrast, non-detained respondents without representation took 353 median days, about 1 year.[78] Table 4 shows that cases with representation took longer to reach the initial case completion than cases without representation for each fiscal year from 2018 through 2023.

Table 4: Median Number of Days from Start of Case to Initial Case Completion, by Custody and Legal Representation Status and Fiscal Year of Completion, Cases Received from Fiscal Years 2016 through 2023

|

|

|

Median number of days from case start to initial completion |

|||||

|

Custody and legal representation statusa |

Number of initial case completionsb |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023d |

|

Detained respondents with legal representation |

106,437 |

88 |

94 |

118 |

101 |

96 |

105 |

|

Detained respondents without legal representation |

236,540 |

25 |

36 |

86 |

26 |

37 |

27 |

|

Non-detained respondents with legal representationc |

621,681 |

547 |

663 |

566 |

1,209 |

1,226 |

1,261 |

|

Non-detained respondents without legal representationc |

501,321 |

319 |

203 |

218 |

681 |

659 |

503 |

Source: GAO analysis of Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) data. | GAO‑25‑106867

aWe considered a respondent to have legal representation if they had legal representation at any point in their case.

bTotal cases include removal cases that EOIR received from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023 and had an initial case completion during that time. About 11,000 detained cases and 2.4 million non-detained cases did not have an initial case completion by the end of fiscal year 2023. The number of detained cases with and without an initial case completion do not equal the total number of cases received because the custody status of a case receipt and an initial case completion may differ. We did not include the median number of days from case start to initial case completion for completions that occurred in fiscal year 2016 or fiscal year 2017 since they consist of cases EOIR received and completed in two fiscal years, resulting in artificially lower case processing times, compared to other fiscal years in our analysis.

cWe included cases in which the respondent was originally detained and then later released among the non-detained cases.

dThe median number of days from the start of a case to initial case completion in fiscal year 2023 may be lower than prior years, particularly for non-detained cases without legal representation, because cases starting in later fiscal years had less time to finish, and only those cases completing within the shorter time contributed to the median.

Master Calendar and Merits Hearings

The time to reach the initial master calendar and first merits hearings, for both detained and non-detained cases, varied by whether a respondent had legal representation at any point in their case, according to our analysis. For cases EOIR received from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2023, respondents with legal representation reached the master calendar hearing faster than those without legal representation. For example, the median number of days in which non-detained respondents with legal representation reached the initial master calendar hearing was 100 days, while the median number for respondents without legal representation was 149 days. Respondents with legal representation moved from the initial master calendar hearing to the first merits hearing more slowly than those without legal representation. For example, the median number of days non-detained respondents with legal representation took from the initial master calendar hearing to the first merits hearing was 795 days, about 2.2 years, while the median for non-detained respondents without legal representation was 489 days, about 1.3 years.

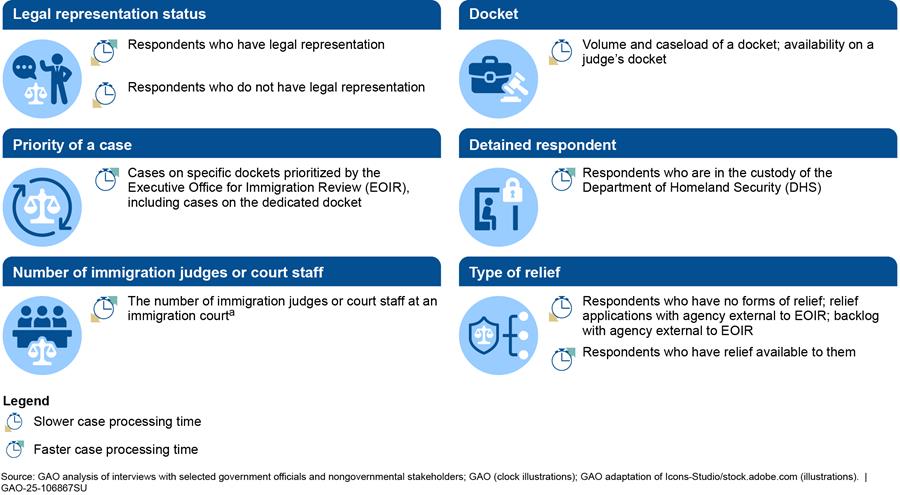

Government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders we interviewed provided their perspectives on the key drivers of case processing times, including the time to reach the hearings within a case or an initial case completion.[79] Some of the key drivers they identified as associated with faster case processing times—such as detained respondents—and others they identified as associated with slower case processing times—such as the volume and caseload of a docket, as shown in figure 13. For three of the identified drivers—legal representation status, number of immigration judges or court staff, and type of relief—some government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders stated that the driver was associated with faster case processing times, while others stated that the driver was associated with slower case processing times.

Figure 13: Key Drivers of Case Processing Times Identified by Selected Government Officials and Nongovernmental Stakeholders

Note: We conducted interviews of government officials and nongovernment stakeholders at five selected courts. Specifically, we interviewed assistant chief immigration judges, immigration judges, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of the Principal Legal Advisor attorneys representing the U.S. government in immigration court, and private bar attorneys representing noncitizens with cases in immigration court. We also interviewed six external stakeholders such as associations representing practitioners and immigration law researchers.

aAmong the six interviews that identified the number of immigration judges or court staff at an immigration court as a key driver, four noted that limited immigration judges or court staff were associated with slower case processing times. Government officials from one interview noted that a new immigration court, and the associated increase in available judges, were associated with faster case processing times. Government officials from one additional interview did not specify whether a limited number of judges or increase in available judges were associated with slower case processing times.

During these interviews, government officials and nongovernmental stakeholders identified respondents’ legal representation status as a key driver of case processing times.[80] For instance, in five of these interviews, two OPLA attorneys, two nongovernmental stakeholders, and one immigration judge indicated that legal representation was associated with faster case processing times. Conversely, in six interviews, including two interviews mentioned above, four OPLA attorneys, one assistant chief immigration judge, and one private bar attorney indicated that legal representation was associated with slower case processing times.

Dedicated Docket Cases Took About One Year from Start to Initial Case Completion from Fiscal Year 2021 through Fiscal Year 2023