FEDERAL EMPLOYEES HEALTH BENEFITS PROGRAM

OPM Should Take Timely Action to Mitigate Persistent Fraud Risks

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Seto J. Bagdoyan at bagdoyans@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-106885, a report to congressional requesters

FEDERAL EMPLOYEES HEALTH BENEFITS PROGRAM

OPM Should Take Timely Action to Mitigate Persistent Fraud Risks

Why GAO Did This Study

FEHB is the largest employer-sponsored health insurance program in the country. It provides benefits to more than 8.2 million federal employees, family members, and other eligible individuals. FEHB’s total cost to the government and enrollees was about $70 billion in fiscal year 2024. OPM is responsible for administering the FEHB program and managing the risk of fraud.

GAO was asked to review OPM’s fraud risk management efforts in the FEHB program. This report assesses the extent to which OPM has (1) designated an entity to lead fraud risk management activities, (2) assessed the full range of fraud risks in the FEHB program, and (3) involved key stakeholders in its fraud risk assessments.

GAO reviewed OPM documentation and policies, and interviewed OPM and OPM OIG officials regarding fraud risk management activities in the FEHB program. GAO compared this information with selected leading practices of GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework, as well as federal standards for internal control.

What GAO Recommends

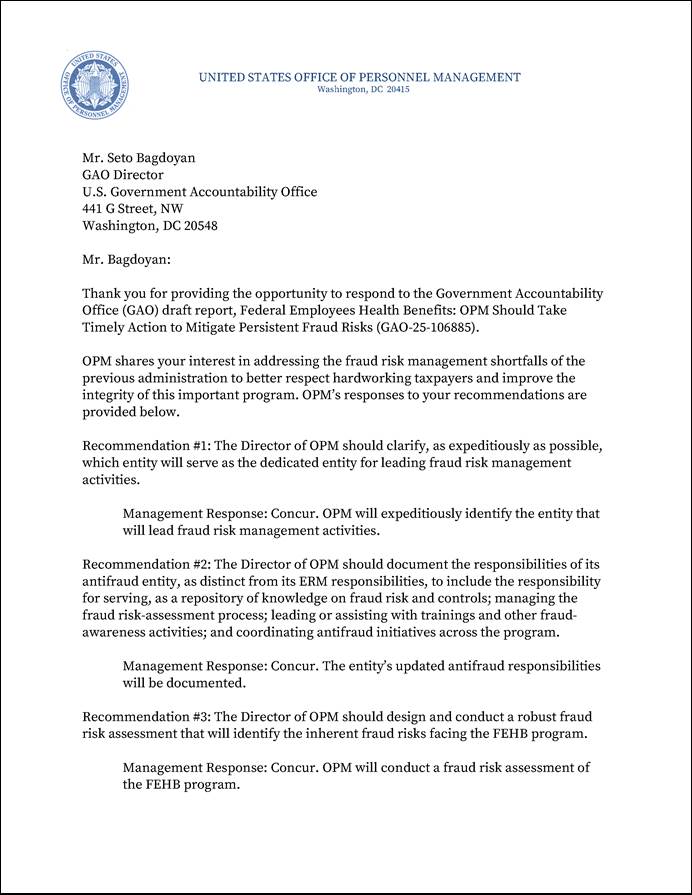

GAO is making six recommendations, including that OPM clarify which entity will lead fraud risk management efforts, design and conduct a robust fraud risk assessment that will identify the inherent fraud risks facing the FEHB program, and involve relevant stakeholders in the fraud risk assessment process. OPM concurred with all six recommendations and indicated that it will take actions to implement them.

What GAO Found

In response to GAO’s December 2022 report on the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) program, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) has taken some steps to manage the program’s fraud risks, such as completing fraud risk assessments. However, two recommendations, including that OPM identify and remove ineligible family members from FEHB, remain open. In this second review of the FEHB program, GAO found that OPM’s ongoing efforts to manage fraud risks do not fully align with selected leading practices.

OPM designated an entity to lead fraud risk management, but its future is uncertain. OPM designated the Risk Management Council (RMC) to lead its fraud risk management efforts. However, in April 2025, OPM officials stated that the agency is in a transition period, and it is uncertain whether the RMC will continue to lead these efforts. With a pause in fraud risk management at the agency level, OPM has the opportunity to address persistent fraud risks and safeguard government investments in FEHB.

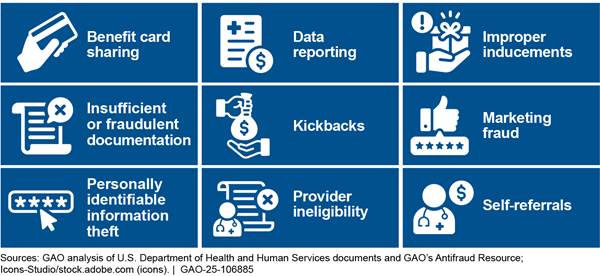

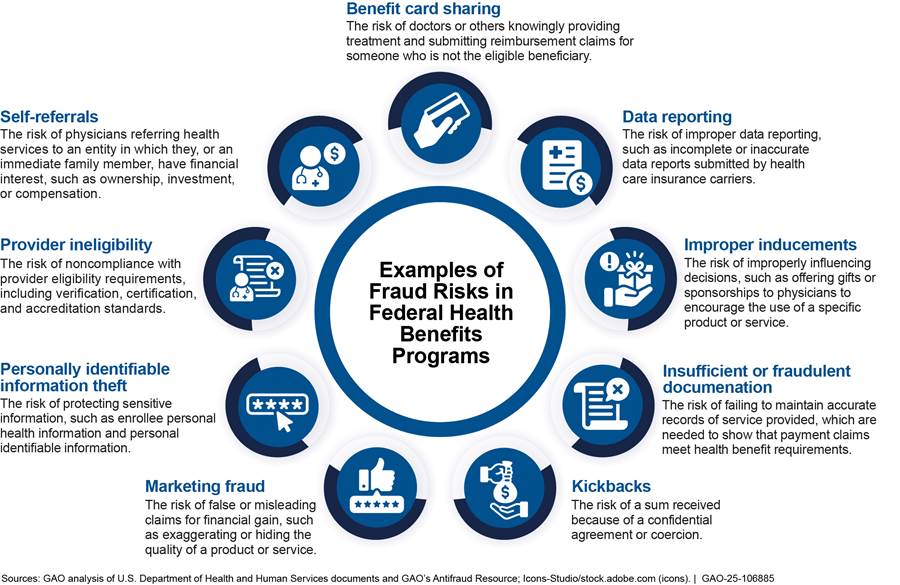

OPM has not assessed the full range of fraud risks facing the FEHB program. OPM’s most recent fraud risk profile identifies two inherent fraud risks—an ineligible family member on an FEHB plan and an FEHB provider submitting false claims to an FEHB carrier—but does not reflect other fraud risks (see fig.). Officials could not explain or provide documentation as to why their fraud risk assessment and profile did not capture these inherent fraud risks.

OPM does not involve key stakeholders directly in its fraud risk assessment process. According to OPM officials, the agency relies on OPM’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) reports and carrier information on fraud, waste, and abuse to inform its fraud risk assessments. However, OPM does not engage directly with these stakeholders to identify FEHB fraud risks and obtain insights. Involving key stakeholders in its fraud risk assessments would help OPM leverage stakeholders’ extensive knowledge to better identify the full range of fraud risks and determine how to address them.

Abbreviations

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

CHIP |

Children’s Health Insurance Program |

|

ERM |

Enterprise Risk Management |

|

FEHB |

Federal Employees Health Benefits |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HMO |

Health Maintenance Organizations |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

PPO |

Preferred Provider Organizations |

|

RMC |

Risk Management Council |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 17, 2025

The Honorable Ron Johnson

Chairman

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Rick Scott

United States Senate

The Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) program is the largest employer-sponsored health insurance program in the country. It provides health insurance benefits to federal employees, retired federal employees, eligible family members, and other eligible individuals. In fiscal year 2024, the FEHB program provided health insurance benefits to 8.2 million individuals at a cost to the government and enrollees of approximately $70 billion. This represents an increase in cost of about 19 percent since we reported on the FEHB program in December 2022.[1] The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) administers the FEHB program and contracts with health insurance carriers that offer plans in which eligible individuals may enroll to receive health care benefits. OPM requires each participating health insurance carrier to establish a program to prevent, detect, and eliminate fraud, waste, and abuse in the provision of health care benefits.[2]

Our December 2022 report examined the risk of fraud and improper payments associated with the enrollment of ineligible family members in FEHB. OPM estimated that such coverage could cost the program up to $1 billion per year.[3] We found that without a monitoring mechanism, ineligible family members may remain covered, and related improper payments may continue to accrue over time. In this regard, any ineligible family members that remain covered by the program due to fraud or error contribute to higher costs for the FEHB program and higher premiums for FEHB enrollees. In our December 2022 report, we made four recommendations, two of which have since been implemented. However, OPM has not implemented our other two recommendations related to establishing monitoring mechanisms to verify eligibility and identify and remove ineligible family members from the FEHB program.[4]

Managers of federal programs—like the FEHB program—are responsible for managing fraud risks and implementing leading practices for combating those risks. Effectively managing fraud risk helps ensure that federal programs’ services fulfill their intended purpose, that funds are spent effectively, and that assets are safeguarded. In July 2015, we issued A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework), which provides a comprehensive set of leading practices that serve as a guide for agency managers to use when developing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based way.[5]

Following our December 2022 report, you asked us to continue to review OPM’s fraud risk management efforts in the FEHB program. This second report identifies the extent to which OPM has (1) designated an entity to lead fraud risk management activities agency-wide; (2) assessed the full range of fraud risks in the FEHB program; and (3) involved key stakeholders in its fraud risk assessments.

To address all three objectives, we reviewed documentation on OPM’s policies, plans, and methodology for fraud risk management activities. These documents include the agency’s fraud risk profile and documents related to its fraud risk assessment. We also interviewed OPM and OPM Office of the Inspector General (OIG) officials regarding any fraud risk management activities they have undertaken in the FEHB program. Further, we reviewed OPM’s policies and documentation related to other risk assessment processes, such as enterprise risk management (ERM) and improper payment risk assessments.

We compared this information with selected leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework.[6] Specifically, we selected leading practices that were most relevant to our objectives and that represent key steps in developing effective fraud risk management activities.[7] We also compared the information we gathered to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[8]

Additionally, for our second objective, we reviewed GAO, OPM’s OIG, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reports from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 to identify examples of fraud risks that exist in similar federal health benefits programs—such as Medicare and Medicaid—and could be present in the FEHB program. We also reviewed fraud risk assessments that HHS’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services conducted in 2021 and 2022 for the Medicaid Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicare Fee-For-Service Program, Medicare Advantage (Part C), and Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit (Part D) Program.[9] We compared information on these fraud risks with OPM’s fraud risk profile to determine whether OPM had assessed the full range of fraud risks, in accordance with leading practices.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FEHB Program and Health Insurance Carriers

Established in 1960, the FEHB program provides health insurance benefits to federal employees, retired federal employees, other eligible individuals, and their eligible family members. OPM administers the FEHB program and contracts with qualified health insurance carriers to provide health care coverage to its members, among other responsibilities. For the 2024 plan year, the FEHB program had 67 contracts with 52 carriers offering a total of 157 plan choices, according to OPM. In plan year 2024, the FEHB program covered approximately 2.3 million federal employees, 1.9 million annuitants, and 4 million family members.

While OPM oversees fraud risk management across the agency, carriers are responsible for the design and implementation of certain program controls for mitigating fraud, specifically for the FEHB program.[10] For example, as part of their contracts with OPM, carriers are required to operate a system designed to detect and eliminate fraud, waste, and abuse internally by carrier employees and subcontractors; by health care providers; and by FEHB enrollees, among other requirements. Carriers are also required to assess their vulnerability to fraud, waste, and abuse by performing postpayment reviews and audits of providers. Further, carriers are required to demonstrate they have submitted written notification to OPM’s OIG within 30 business days of identifying potential fraud, waste, and abuse, regardless of the dollar value of specific instances. In addition, carriers are required to submit annual fraud, waste, and abuse reports, which cover the prior calendar year.

OPM’s Office of the Inspector General

OPM’s OIG audits the activities of health insurance carriers and their plans to ensure that they meet their contractual obligations with OPM. For example, OPM’s OIG examines whether the carrier charged costs to the FEHB program and provided services to FEHB members in accordance with the terms of its contract. OPM’s OIG issues reports that highlight its audit findings and recommendations, including findings and recommendations related to fraud and improper payments.

Additionally, OPM’s OIG is responsible for the design and implementation of the program to suspend or debar health care providers from participating in FEHB—a control for mitigating fraud and improper payments—among other things. OPM’s OIG debars or suspends health care providers from participating in the FEHB program under relevant statutory and regulatory authorities.[11] OPM’s OIG can suspend and debar health care providers who have, among other things,

· lost professional licenses;

· been convicted of a crime related to delivery of or payment for health care services; or

· been debarred or suspended by another federal agency in certain instances.

Improper Payments and Fraud Risk Management

Improper payments are payments that should not have been made or were made in the incorrect amount—that is, an overpayment or underpayment—under a statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirement.[12] Improper payments can be a result of mismanagement, error, or fraud and abuse. Within the FEHB program, improper payments include payments for premiums or claims for ineligible members and providers, according to OPM officials. As in previous years, identifying and reporting improper payments in the FEHB program remains a top management challenge for the agency, according to OPM’s OIG.[13]

While improper payments and fraud are related concepts, they do not mean the same thing.

· Fraud is obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation. Fraud can sometimes involve benefits that do not result in direct financial loss to the government.

· Improper payments are payments that should not have been made or that were made in the incorrect amount; typically, they are overpayments. While all fraudulent payments are considered improper, not all improper payments are due to fraud.

Fraud and fraud risk are distinct concepts. Fraud involves obtaining a thing of value through willful misrepresentation characterized by making materially false statements of fact based on actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance, or reckless disregard of falsity. A fraud risk exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity. The existence of fraud risks does not necessarily indicate that fraud exists or will occur. However, fraud risks are often present when fraud does occur.

The objective of fraud risk management is to ensure program integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating both the likelihood and effects of fraud. Effectively managing fraud risks helps to ensure that federal programs’ services fulfill their intended purpose, that funds are spent effectively, and that assets are safeguarded. Federal agency managers are responsible for managing fraud risks and implementing practices for combating those risks.

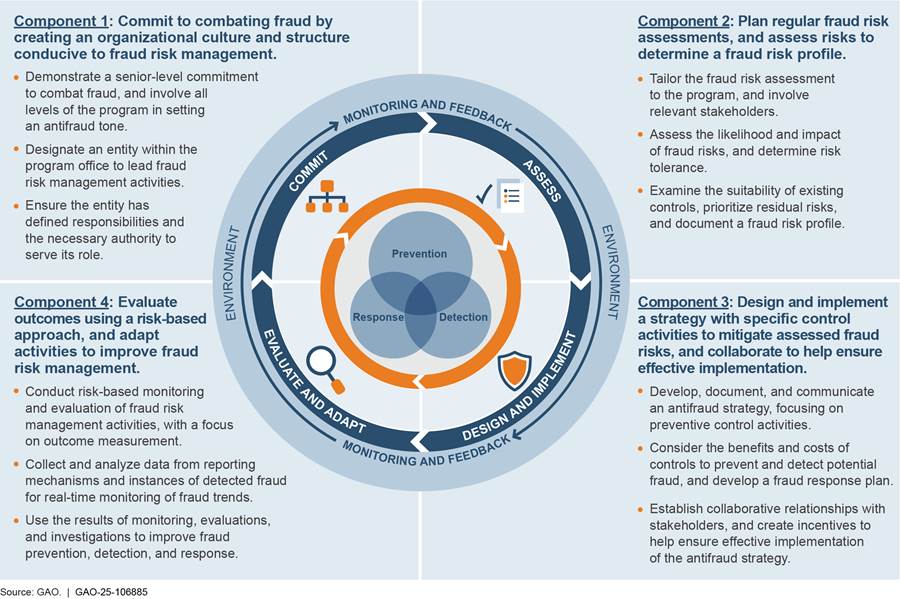

GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework provides a comprehensive set of key components, overarching concepts, and leading practices that guide agency managers when developing activities to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[14] As depicted in figure 1, the Fraud Risk Framework describes leading practices within four components: (1) Commit, (2) Assess, (3) Design and Implement, and (4) Evaluate and Adapt.

As required under the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 and its successor provisions in the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, the leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework are incorporated into the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) guidelines for agency controls.[15] Specifically, OMB’s Circular No. A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, directs executive agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks.[16]

ERM and Fraud Risk Management

ERM enables an agency to address the full spectrum of risks and challenges related to achieving its mission.[17] The Fraud Risk Framework acknowledges that agencies may incorporate fraud risk management activities into initiatives like ERM to manage fraud risks. That, however, does not eliminate the need for separate and independent fraud risk management efforts, in a complementary manner. Additionally, in October 2022, OMB issued a Controller Alert reminding agencies that they must establish financial and administrative controls to identify and assess fraud risks.[18] The alert specifically reminded agencies that they should adhere to the leading practices in the Fraud Risk Framework to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks, including those that do not rise to the level of enterprise-wide risks.

OPM Designated an Entity to Lead Fraud Risk Management, but Its Future Is Uncertain

In 2023, OPM designated the Risk Management Council (RMC) as the dedicated entity to lead fraud risk management activities, including overseeing FEHB risk management. According to OPM’s 2024 Agency Financial Report, the RMC develops, implements, and leads OPM’s ERM program, including efforts to identify and manage the major risks facing the agency.[19]

However, in April 2025, OPM officials told us that while the RMC remains a governing body that oversees FEHB risk management, they are uncertain whether the RMC will continue in this role. Further, these officials told us that as of April 2025, the agency is in the process of workforce optimization in accordance with applicable presidential executive orders and that fraud risk management and ERM processes at the agency level are on hold. OPM officials could not provide an estimate as to when fraud risk management efforts would resume. With a pause in fraud risk management at the agency level, OPM has the opportunity to address persistent fraud risks and safeguard government investments in FEHB.

The RMC’s current operating status notwithstanding, we reviewed the existing key policy and planning documents related to a dedicated fraud risk management entity that OPM and OPM’s OIG provided in response to our inquiries.[20] For example, we reviewed OPM’s RMC Charter, which describes its responsibilities for ERM, including providing oversight of fraud risk management activities.

However, the RMC Charter and other documents we reviewed do not state how the RMC would carry out its role in accordance with leading practices for fraud risk management (see textbox for more information on creating a structure to lead fraud risk management).

|

Leading Practices for Creating a Structure to Lead Fraud Risk Management Leading practices in GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs include creating a structure with a dedicated entity to lead fraud risk management activities. In carrying out this role, the antifraud entity, among other things, · serves as the repository of knowledge on fraud risks and controls, · manages the fraud risk assessment process, · leads or assists with trainings and other fraud awareness activities, and · coordinates antifraud initiatives across the program. |

Source: GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 28, 2015). | GAO‑25‑106885

Further, we have previously reported that while the Fraud Risk Framework acknowledges that agencies may use ERM to assess and manage their fraud risks in a complementary fashion, it does not eliminate separate and independent fraud risk management requirements.[21] Therefore, it is uncertain whether the RMC or a successor would perform its duties and functions in accordance with leading practices, distinct from ERM.

As noted above, leading practices for fraud risk management indicate that the agency should designate an antifraud entity with defined responsibilities for leading and overseeing fraud risk management activities. Further, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that managers should document in policies the internal control responsibilities of the organization.[22]

With a pause in fraud risk management activities during the agency’s transition period, OPM has an opportunity to clarify the RMC’s current and future status as the dedicated entity to lead fraud risk management activities and document its roles and responsibilities in this regard. Without a designated antifraud entity and clearly defined and documented roles and responsibilities for that entity—including serving as a repository of knowledge on fraud risk and controls, managing the fraud risk-assessment process, leading or assisting with trainings and other fraud-awareness activities, and coordinating antifraud initiatives across the program—OPM does not have the structure to strategically manage fraud risks in FEHB and prioritize the ones that are most significant in accordance with leading practices.

OPM Has Not Assessed the Full Range of Fraud Risks in the FEHB Program

While OPM has taken some steps to assess some inherent fraud risks in accordance with leading practices, it has not assessed the full range of fraud risks in the FEHB program.[23] According to agency officials, OPM conducted fraud risk assessments of the FEHB program in 2020, 2023, and in March 2024.

In June 2024, OPM provided us a fraud risk profile identifying two inherent fraud risks facing the FEHB program: (1) an ineligible family member on an FEHB plan and (2) an FEHB provider submitting false claims to an FEHB carrier.[24] Consistent with leading practices, OPM’s fraud risk profile shows that the agency assessed the likelihood and impact of these fraud risks and determined its fraud risk tolerance for these fraud risks (see textbox for more information on leading practices for fraud risk assessments).[25]

|

Leading Practices for Identifying and Assessing Risks to Determine the Program’s Fraud Risk Profile Leading practices in GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs include identifying and assessing risks to determine the program’s fraud risk profile. Specifically, the leading practices call for · assessing the likelihood and impact of inherent fraud risks, · determining fraud risk tolerance, · examining the suitability of existing fraud controls and prioritizing residual fraud risks, and · documenting the program’s fraud risk profile. |

Source: GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 28, 2015). | GAO‑25‑106885

While OPM identified two fraud risks, our review identified nine additional fraud risks facing the FEHB program that do not appear on OPM’s fraud risk profile (see fig. 2 below). Specifically, we identified several fraud risks in other federal health benefits programs—such as Medicare and Medicaid—that OPM and OPM OIG’s officials acknowledged are also inherent in FEHB but do not appear on OPM’s fraud risk profile.

Figure 2: Examples of Fraud Risks in Federal Health Benefits Programs Not on the Office of Personnel Management’s Fraud Risk Profile for the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program

Note: The fraud risk descriptions in this figure are not legal definitions. These descriptions are sourced from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services documents and GAO’s Anti-Fraud Resource. These examples are presented for illustrative purposes and are not intended to be a comprehensive list of fraud risks in federal health benefits programs.

We asked OPM if it had considered the nine additional fraud risks we identified when it conducted its fraud risk assessments of FEHB. In April 2025, OPM officials told us they could not explain or provide documentation as to whether these inherent risks were considered as part of the assessment process and why the resulting fraud risk profile does not address these risks. This was, in part, because officials responsible for conducting fraud risk assessments have since left the agency, and no explanatory documentation could be identified.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system. Effective documentation assists in management’s design of internal control by establishing and communicating the who, what, when, where, and why of internal control execution to personnel. Documentation also provides a means to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel, as well to communicate that knowledge, as needed, to external parties, such as external auditors. Developing and maintaining documentation of its fraud risk assessments would help OPM ensure it does not lose organizational knowledge about its fraud risk assessments and ensure that its fraud risk assessments are designed to capture inherent fraud risks facing the program in accordance with leading practices.

Leading practices for fraud risk management also state that agencies should identify inherent risks facing the program and document the program’s fraud risk profile. Further, leading practices state that agencies should tailor the fraud risk assessment to the program and identify specific tools, methods, and sources for gathering information about fraud risks. Designing and conducting a robust fraud risk assessment that will identify the inherent fraud risks would better position OPM to manage the full range of fraud risks facing the FEHB program. Further, ensuring that the agency documents its assessment of those risks on its fraud risk profile would enable OPM to retain institutional knowledge to combat fraud risks.

OPM Has Not Involved Key Stakeholders Directly in Its Fraud Risk Assessments

When it conducted fraud risk assessments of the FEHB program, OPM considered information reported by OPM’s OIG and FEHB health insurance carriers, but OPM did not involve these stakeholders directly in its fraud risk assessment process.

· OPM’s OIG. According to OPM officials, the agency gathered information from OPM OIG’s audits and investigations of carriers to inform its fraud risk assessments. OPM officials also told us that the agency incorporated into its fraud risk assessments fraud-related findings from OPM OIG’s semiannual reports to Congress. However, OPM did not directly engage with OPM’s OIG for the purposes of identifying FEHB fraud risks as part of its fraud risk assessments. OPM OIG officials confirmed with us that they did not participate in OPM’s fraud risk assessments and, to their knowledge, have never been invited to participate in OPM’s fraud risk assessments.

· FEHB health insurance carriers. OPM officials also told us that their fraud risk assessments consider information from FEHB carriers related to fraud, waste, and abuse. This includes information on fraudulent schemes; the number of allegations received; and cases referred to local, state, or federal law enforcement and agencies. However, OPM officials we spoke to noted that carriers were not directly involved in, and have not informed, the fraud risk assessment process.

Leading practices in fraud risk management call for program managers to engage with and involve relevant stakeholders in the fraud risk assessment process, including individuals responsible for the design and implementation of a program’s controls for mitigating fraud.[26]

As mentioned, OPM’s OIG and the carriers are responsible for the design and implementation of certain program controls for mitigating fraud specifically for the FEHB program, while OPM oversees fraud risk management across the agency. When we asked OPM officials why they did not directly involve OPM’s OIG and the carriers in their fraud risk assessments, they told us they felt they could rely on OPM’s OIG and carrier information rather than involve them directly. However, the OPM’s OIG and the carriers are responsible for the design and implementation of program controls including controls for mitigating fraud. This underscores the importance of direct and regular communication with OPM’s OIG and carriers about fraud risks during the fraud risk assessment process. By not directly involving OPM’s OIG and the carriers, OPM is missing opportunities to leverage stakeholders’ extensive knowledge to more comprehensively understand the full range of fraud risks facing the FEHB program and determine ways to more effectively manage those fraud risks.

Conclusions

As the country’s largest employer-sponsored health insurance program, effective fraud risk management is critical to help safeguard the FEHB program’s billions in federal funding and to help ensure the program fulfills its intended purpose.

To its credit, OPM has taken some steps to manage fraud risks facing the FEHB program. For example, OPM has conducted regular fraud risk assessments of its FEHB program, and its March 2024 fraud risk profile shows that the agency assessed some fraud risks. However, OPM is undergoing an institutional transition that has resulted, among other things, in a pause in its fraud risk management activities. This pause provides OPM the opportunity to improve its fraud risk management in a manner that is consistent with leading practices.

For example, OPM has yet to fully and expeditiously implement the remaining two recommendations from our December 2022 report. This includes implementing a mechanism to identify and remove ineligible family members from the FEHB program, which may cost up to $1 billion annually, according to OPM’s estimate. Further, as this report shows, OPM has not implemented relevant leading practices for fraud risk management. Specifically, designating a dedicated antifraud entity—such as the RMC or a possible successor—and documenting its responsibilities, as distinct from ERM responsibilities, would better position OPM to strategically manage fraud risks in the FEHB program.

With regard to its fraud risk assessments, designing and conducting a robust fraud risk assessment that identifies inherent fraud risks would better position OPM to manage the full range of fraud risks facing the FEHB program. Further, developing and maintaining documentation of the assessments can help OPM retain institutional knowledge of its efforts to combat fraud risks. Finally, involving relevant stakeholders responsible for program controls in FEHB—such as the OPM’s OIG and health insurance carriers—can help ensure that OPM leverages the extensive knowledge of those stakeholders and enhance OPM’s ability to more comprehensively understand the fraud risks, including emerging risks, and address them accordingly.

Overall, taking the actions discussed above would improve OPM’s fraud risk management; help mitigate persistent fraud risks facing the FEHB program in a strategic, targeted manner; and help safeguard the government’s significant investment in the FEHB program.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following six recommendations to OPM:

The Director of OPM should clarify, as expeditiously as possible, which entity will serve as the dedicated entity for leading fraud risk management activities. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of OPM should document the responsibilities

of its antifraud entity, as distinct from its ERM responsibilities, to include

the responsibility for serving as a repository of knowledge on fraud risk and

controls; managing the fraud risk-assessment process; leading or assisting with

trainings and other fraud-awareness activities; and coordinating antifraud

initiatives across the program.

(Recommendation 2)

The Director of OPM should design and conduct a robust fraud risk assessment that will identify the inherent fraud risks facing the FEHB program. (Recommendation 3)

The Director of OPM should develop and maintain documentation of its fraud risk assessments. (Recommendation 4)

The Director of OPM should ensure that it documents the results of its assessment of inherent fraud risks facing the FEHB program on its fraud risk profile. (Recommendation 5)

The Director of OPM should involve relevant stakeholders—including OPM’s OIG and health insurance carriers—by including their participation in its fraud risk assessment process. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to OPM for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix I, OPM concurred with all recommendations and indicated that it will take actions to implement them. In addition, OPM provided technical comments, which we incorporated in the report, as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Director of OPM, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at BagdoyanS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Seto J. Bagdoyan

Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

GAO Contact

Seto J. Bagdoyan, bagdoyans@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Jonathon Oldmixon (Assistant Director), Tina Paek (Analyst in Charge), Garrick Donnelly, Mark MacPherson, Brenda Mittelbuscher, Haley Klosky, Emmanuel Sanchez, Hiba Sassi, and Erin McLaughlin Villas, made key contributions to this report. Other contributors include James Ashley, Colin Fallon, James Healy, Barbara Lewis, James Murphy, Maria McMullen, and Andrew Stavisky.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Federal Employees Health Benefits Program: Additional Monitoring Mechanisms and Fraud Risk Assessment Needed to Better Ensure Member Eligibility, GAO‑23‑105222 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 9, 2022). In fiscal year 2021, FEHB costs totaled about $59 billion.

[2]Fraud involves obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation. Willful misrepresentation can be characterized by making materially false statements of fact based on actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance, or reckless disregard of falsity. Whether an act is, in fact, fraud is a determination to be made through the judicial or other adjudicative system and is beyond management’s professional responsibility for assessing risk. Waste, abuse, and mismanagement are related but distinct concepts from fraud and improper payments. Waste is when individuals or organizations spend government resources carelessly, extravagantly, or without purpose. Abuse of federal resources occurs when someone behaves improperly or unreasonably, or misuses a position or authority.

[3]Improper payments are payments that should not have been made or were made in the incorrect amount—that is, an overpayment or underpayment—under a statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirement. Also included is any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible good or service, any duplicate payment, any payment for a good or service not received (except for such payments where authorized by law), and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts. While all fraudulent payments are considered improper, not all improper payments are due to fraud. 31 U.S.C. § 3351(4).

[4]We made four recommendations to OPM in our December 2022 report, two of which have since been implemented. We recommended that OPM assess the likelihood and impact of ineligible FEHB members and document that risk in its fraud risk profile (Recommendation 3 and 4). OPM implemented both recommendations in March 2024 by updating its fraud risk profile to include its assessment of family member eligibility for the FEHB program. By assessing the likelihood and impact and documenting this assessment into its fraud risk profile, OPM would be better positioned to manage this fraud risk moving forward. However, as of July 2025, OPM has not fully implemented the following recommendations: (1) OPM should implement a monitoring mechanism to ensure employing offices and carriers are verifying family member eligibility, as required by OPM’s 2021 guidance; and (2) OPM should implement a monitoring mechanism to identify and remove ineligible family members from the FEHB program. OPM partially concurred and concurred with the two recommendations, respectively. On July 4, 2025, legislation was enacted that directed OPM to implement the second of these recommendations. See Pub. L. No. 119-21, § 90101 (2025).

[5]Fraud and fraud risk are distinct concepts. A fraud risk exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity. The existence of fraud risks does not necessarily indicate that fraud exists or will occur. However, fraud risks are often present when fraud does occur. GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 28, 2015).

[7]The Fraud Risk Framework contains four components: (1) Commit, (2) Assess, (3) Design and Implement, and (4) Evaluate and Adapt. Within the four components, there are overarching concepts and leading practices. We selected leading practices from the Commit and Assess components from GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework including: designating an entity to design and oversee fraud risk management, identifying inherent fraud risks affecting the program, assessing the likelihood and impact of inherent fraud risks, determining fraud risk tolerance, documenting the program’s fraud risk profile, and involving relevant stakeholders in the assessment process.

[8]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). For the first objective, we determined that the control activities component of internal control was significant to the objective, along with the underlying principle that management should implement control activities through policies. This includes the minimum documentation requirement that management documents in policies the internal control responsibilities of the organization. We compared OPM’s documentation of the roles and responsibilities of its dedicated antifraud entity with this standard for documentation. For the second objective, we determined that the control environment component of internal control was significant to the objective, along with the underlying principle that management should establish structure, responsibility, and authority. This includes the minimum documentation requirement that management develops and maintains documentation of its internal control system. We compared OPM’s documentation of its fraud risk assessment and fraud risk profile with this standard for documentation.

[9]CHIP provides low-cost health coverage to children in families that earn too much money to qualify for Medicaid. The Medicare Fee-For-Service Program pays physicians, hospitals, and other health care facilities based on statutorily established payment systems, most of which are updated annually through regulations. The Medicare Advantage (Part C) program offers Medicare advantage plans, which may be a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) or Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) that is another Medicare health plan choice available as part of Medicare and offered by private companies approved by Medicare. The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit (Part D) provides access to prescription drug coverage.

[10]We did not evaluate the controls of FEHB carriers or the OPM’s OIG because this was outside the scope of this review which focuses on OPM and its fraud risk management efforts.

[11]5 U.S.C. § 8902a and 5 C.F.R. § 890.1001 – 890.1072. OPM’s OIG operates these authorities under delegation from the OPM Director.

[12]31 U.S.C. § 3351(4).

[13]According to OPM’s OIG, OPM faces improper payments in FEHB as a persistent management challenge because of its long-standing reticence to engage in necessary large-scale program integrity actions. Office of Personnel Management, Office of the Inspector General, Final Report: The U.S. Office of Personnel Management’s Top Management Challenges for Fiscal Year 2025 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 27, 2024).

[15]The Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015, enacted in June 2016, required OMB to establish guidelines for federal agencies to create controls to identify and assess fraud risks and to design and implement antifraud control activities. Pub. L. No. 114-186, 130 Stat. 546 (2016). The Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 was replaced in March 2020 by the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, which required these guidelines to remain in effect, subject to modification by OMB, as necessary, and in consultation with GAO. Pub. L. No. 116-117, § 2(a), 134 Stat. 113, 131-132 (2020), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3357.

[16]Office of Management and Budget, OMB Circular A-123.

[17]According to OMB, ERM is an effective agency-wide approach to address the full spectrum of an organization’s risks by understanding the combined effect of risks as an interrelated portfolio, rather than addressing risks only within silos. ERM provides an enterprise-wide, strategically aligned portfolio view of organizational challenges that, when brought together, provides better insight about how to most effectively prioritize and manage risks to mission delivery. See Office of Management and Budget Circular A-123.

[18]Office of Management and Budget, Establishing Financial and Administrative Controls to Identify and Assess Fraud Risk, [Controller Alert] CA-23-03 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 17, 2022).

[19]The RMC is chaired by the Chief Management Officer and includes senior representatives from all major OPM components. Office of Personnel Management, U.S. Office of Personnel Management Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2024 (November 2024).

[20]The policy and planning documents OPM and OPM’s OIG provided us in response to our inquiries include OPM’s ERM policy document, OPM’s ERM implementation plan, and chapter 24 of its Financial Management Manual. Office of Personnel Management, U.S. Office of Personnel Management Enterprise Risk Management Policy (March 2024); U.S. Office of Personnel Management Enterprise Risk Management Implementation Plan (March 2024); and U.S. Office of Personnel Management Financial Management Manual Ch. 24 “Fraud Risk Management and Reporting Fraud, Waste, and Abuse” (August 2024).

[21]See GAO, DOD Fraud Risk Management: Actions Needed to Enhance Department-Wide Approach, Focusing on Procurement Fraud Risks, GAO‑21‑309 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 19, 2021); and DOD Fraud Risk Management: Enhanced Data Analytics Can Help Manage Fraud Risks, GAO‑24‑105358 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 27, 2024).

[23]According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, inherent risk is the risk to an entity prior to considering management’s response to the risk. GAO‑14‑704G.

[24]As part of its 2024 profile, OPM included the fraud risk related to ineligible family members, which OPM officials stated was in response to a recommendation from our prior report. GAO‑23‑105222. As examples of false claims, OPM’s fraud risk profile lists “billing for services not rendered or up-coding, which is billing for a higher level of service than was actually provided.”

[25]The specific leading practices for managing fraud risks that we refer to here are to identify inherent fraud risks affecting the program; assess the likelihood and impact of inherent fraud risks; determine fraud risk tolerance; and document the program’s fraud risk profile. GAO‑15‑593SP.

[26]Under the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices, involving stakeholders extends to (1) formulating and implementing an antifraud strategy; and (2) monitoring, evaluating, and adapting activities to improve fraud risk management.