DIESEL SCHOOL BUS ALTERNATIVES

Opportunities to Better Assess Progress of Federal Programs

Report to the Chairman, Committee on Environment and Public Works, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-106887, a report to the Chairman, Committee on Environment and Public Works, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: J. Alfredo Gómez at gomezj@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

Federal law has provided over $5 billion for programs, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Clean School Bus program, that have helped fund the replacement of diesel school buses with less polluting buses. EPA reports high demand for the programs, which have helped fund nondiesel buses in school districts across the country. However, implementation of multiple federal programs raises questions about overlap and potential related inefficiencies.

GAO Key Takeaways

EPA and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) have helped fund nondiesel school buses through four programs—three in EPA and one in DOE. EPA’s programs provide grants, rebates, or loans to help pay for less polluting school buses, such as those fueled by propane or electricity. DOE’s program has offered grants for energy improvements, including certain school buses. Funding for the four programs is fragmented and programs overlap, but EPA and DOE have coordinated their efforts and taken other steps to address this.

EPA has committed to pay over $3 billion for grants and rebates for new buses from fiscal years 2022 to 2024. Award recipients have encountered some difficulties deploying new buses, such as delays installing electric bus infrastructure.

EPA collects information to track progress toward program goals, such as emission reductions, but has opportunities to better assess progress. For the Clean School Bus rebates program, EPA does not systematically collect complete information to track factors, such as infrastructure delays, that may hinder deployment of new buses. Further, developing a methodology that generates more complete estimates of emissions from funded buses could help EPA assess the extent to which the programs help reduce emissions.

How GAO Did This Study

We analyzed relevant laws, federal documents, and federal grants and rebate data from fiscal years 2019 to 2024. We compared elements of the four programs. We interviewed officials from EPA and DOE as well as stakeholders with expertise in transportation or air policy. We also conducted site visits to eight school districts selected for geographic diversity and types of buses funded.

What GAO Recommends

We are making two recommendations to EPA: (1) to gather information to verify deployment of rebate-funded buses; and (2) to develop a methodology for more complete estimates of emission reductions from its programs. EPA generally agreed with the recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ARP |

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 |

|

DERA |

Diesel Emissions Reduction Act |

|

DOE |

U.S. Department of Energy |

|

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FY |

Fiscal Year |

|

GVWR |

Gross Vehicle Weight Rating |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 |

|

Joint Office |

Joint Office of Energy and Transportation |

|

MOVES |

Motor Vehicle Emission Simulator |

|

NCES |

National Center for Education Statistics |

|

OIG |

EPA’s Office of the Inspector General |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 27, 2025

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chairman

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

Dear Chairman Capito:

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and other statutes have provided billions of dollars in appropriations to incentivize school districts and other entities to replace existing school buses with less polluting buses fueled by, for example, electricity, propane, or compressed natural gas. In particular, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act appropriated a total of $5 billion from fiscal year (FY) 2022 through FY2026 to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the Clean School Bus program. EPA’s Clean School Bus program provides grants and rebates to replace existing school buses with buses fueled by electricity and propane, among other alternative fuels. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act also appropriated a total of $500 million from FY2022 through FY2026 for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to administer grants for energy improvements at public school facilities, including the purchase of alternative fueled buses and other vehicles.

In addition, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 appropriated a total of $1 billion from FY2022 through FY2031 for EPA’s Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program, which offers grants to subsidize the purchase of certain zero-emission heavy-duty vehicles, including eligible school buses.[1] Finally, Congress has appropriated varying funding levels from FY2008 through FY2024 for EPA’s Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) program, which has funded school bus replacements and other actions to reduce diesel emissions. For example, EPA’s annual appropriations from FY2020 through FY2024 included funds for DERA ranging from $87 million (FY2020) to $100 million (FY2023).[2]

According to available data, our nation’s school bus fleet relies primarily on diesel engines that provide durability but also emit pollutants—such as nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter—that can degrade air quality and harm public health.[3] Diesel engines also emit carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. EPA regulates air pollution from newly manufactured vehicles, including school buses, and engines. The regulations do not, however, retroactively apply to school buses and other vehicles already in use, known as legacy vehicles. Legacy diesel vehicles can operate for decades and emit higher levels of nitrogen oxides, fine particulate matter, and other pollutants in exhaust than newer models, according to an EPA report for Congress.[4] Replacing legacy school buses with less polluting school buses may help to protect public health, according to EPA.

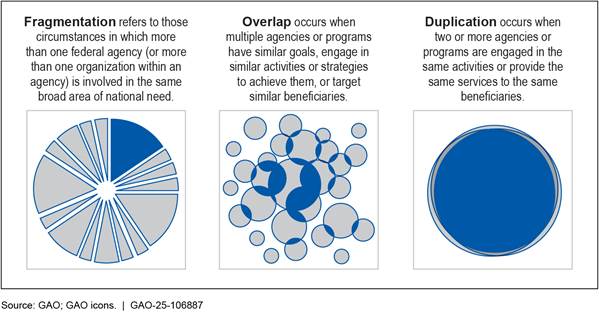

The programs established under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 have garnered support from school districts, state agencies, and other stakeholders, but also raised questions about implementation and potential fragmentation, overlap, and duplication among federal programs. Fragmentation refers to those circumstances in which more than one federal agency is involved in the same broad area of national need. Overlap occurs when multiple agencies or programs have similar goals, engage in similar activities or strategies to achieve them, or target similar beneficiaries.[5] Duplication occurs when two or more agencies or programs are engaged in the same activities or provide the same services to the same beneficiaries.[6]

Additionally, the EPA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has audited the management of Clean School Bus program funds. In July 2024, EPA’s OIG reported that EPA followed six of the seven requirements for selecting Clean School Bus funding recipients but found that the agency did not have sufficient internal controls to ensure recipients were eligible for school buses.[7]

You asked us to review the implementation of federal programs that fund nondiesel school buses—those fueled by alternatives to diesel—and issues related to potential fragmentation, overlap, and duplication.[8] This report examines (1) key federal programs that help fund nondiesel school buses and how agencies implement them; (2) the extent to which fragmentation, overlap, and duplication exist among federal funding and key programs and any steps federal agencies have taken to address fragmentation, overlap, and duplication; and (3) the extent to which agencies track the performance of the key programs.

To examine key federal programs that help fund nondiesel school buses and how agencies implement them, we analyzed relevant laws and federal documents, including Notices of Funding Opportunities, and searched for congressionally directed spending. We defined a key federal program as one that either expressly aims to provide grants, rebates, or loans to help fund nondiesel school buses, or that provided grants, rebates, or loans to help fund nondiesel buses for more than five school districts from FY2019 through FY2023.[9] To ensure that we identified all key federal programs, we interviewed federal officials from EPA, DOE, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office), and nine stakeholders with expertise in transportation or air quality policy.

To identify potential stakeholders, we compiled a list of organizations with expertise in transportation or air quality policy, representing a variety of organization types (e.g., industry/trade associations or research organizations) and experience with federal programs. We selected a nongeneralizable sample of nine stakeholders from this list for interviews based on their experience with nondiesel school buses and federal funding programs. We also conducted site visits to eight school districts in three U.S. Census regions to observe program implementation and obtain perspectives of stakeholders applying for funding. Findings from our sample of school districts selected to receive awards (federal awardees) that we visited are nongeneralizable to all federal awardees.

To examine the extent to which fragmentation, overlap, and duplication exists among federal funding and key programs and any steps federal agencies have taken to address fragmentation, overlap, and duplication, we applied GAO’s evaluation guide.[10] Specifically, we reviewed legal requirements, program documents, Notices of Funding Opportunities, and interviewed EPA and DOE officials to identify program elements. We compared the similarities and differences among the program elements and evaluated how the programs related to each other. We also interviewed officials at EPA and DOE, which are the two agencies implementing key programs discussed in this report, to determine the extent to which agencies coordinate the programs.

To assess the extent to which the agencies track the performance of key programs, we analyzed program documentation and interviews with officials from both agencies. We examined how agencies track progress toward the program goals identified through our analysis of fragmented funding and overlapping programs. We also identified performance measures of progress toward program goals through documentation, such as Notices of Funding Opportunity and reporting templates that the agencies use to monitor recipient use of federal funds. To identify opportunities to enhance agencies’ assessment of program performance, we reviewed GAO’s guide to evidence-based policymaking, which identifies 13 key practices for managing and assessing the results of federal programs and applied selected key practices to our analysis.[11] Specifically, we compared selected key practices to our assessment of how agencies track progress toward program goals. See appendix I for a more detailed discussion of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Types of Buses in the Nation’s School Bus Fleet

Roughly 500,000 school buses transport students in the United States and rely primarily on diesel fuel, according to available data.[12] EPA reported that many of the diesel school buses in use predate EPA’s recent federal emission standards for heavy duty vehicles.[13]

Fossil fuels other than diesel, such as propane, gasoline, and compressed natural gas, are also used to power school buses. According to a 2019 report, about 6 percent of school buses sold in 2017 ran on propane and 1 percent used compressed natural gas.[14]

Electric school buses account for about 1 percent of the U.S. bus fleet, according to available data.[15] The rate of electric school bus deployment has increased in recent years. According to the World Resources Institute, the number of electric school buses in use rose from 87 buses in 2017 to 911 in 2021, a 10-fold increase.[16] In 2022, the number of new electric buses in use increased to 2,693, more than doubling the number of electric buses in use from the prior year.[17]

Bus pricing depends on various factors, including fuel type and bus capacity.[18] For example, a 2025 study on school bus pricing reported manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) for a new diesel school bus that ranged from $98,000 to $154,000, depending on the bus capacity.[19] The MSRP for new electric school buses ranged from $300,000 to $440,000, depending on bus size.[20] A 2019 market study reported that a new propane school bus may cost about $110,000 to $115,000, and a new compressed natural gas bus about $125,000 to $130,000.[21]

Air Pollution from Diesel School Buses

Diesel-powered school buses emit pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides, that can degrade air quality and harm public health. Nitrogen oxides also react with other chemicals in the air to form both particulate matter and ozone.[22] A large body of scientific evidence has linked exposure to particulate matter to serious health problems, including asthma, chronic bronchitis, heart attack, and premature death. Ozone can also cause respiratory illnesses, decreased lung function, and increase risk of premature death from heart or lung disease. Additionally, diesel engines emit carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change.

According to a 2022 EPA report for Congress, children are particularly vulnerable to air pollution from diesel school buses because their lungs have not fully developed and they have faster breathing rates than adults.[23] More specifically, EPA has reported that exposure to these pollutants increases children’s risk of asthma and other respiratory illness, which have been linked to students missing school.[24]

Starting in the mid-1970s, EPA established progressively more stringent emissions standards to limit the emissions of certain pollutants from newly manufactured vehicles and engines, including school buses. The most stringent standards generally apply to diesel engines and vehicles built after 2007. For example, starting with vehicle model year 2007, federal standards represented a 90 percent reduction in particulate matter from most newly manufactured heavy-duty diesel engines, including school buses, compared to the levels permitted under the prior standard.[25] EPA phased in additional standards limiting nitrogen oxides and other diesel emissions from vehicle model years 2007 through 2010. The latest federal emissions standards for newly manufactured heavy-duty vehicles, including school buses, will start with vehicle model year 2027.[26]

Resources for Deployment of Nondiesel School Buses

A variety of financial and technical assistance programs offer incentives and support for school districts to deploy nondiesel vehicles, including electric school buses. Federal funding accounts for the largest fraction of funding incentives. In addition to the federal grant and rebate programs discussed later in this report, state programs, and private sector sources, such as a utility program that helps schools set up the infrastructure for charging electric vehicles, provide support for the deployment of nondiesel school buses.

Federal tax credits for electric vehicles and charging infrastructure are also available to school districts and other tax-exempt entities through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and implemented by the Internal Revenue Service. For example, school districts could be eligible for the Qualified Commercial Clean Vehicle (Section 45W) and Alternative Fuel Refueling Property (Section 30C) tax credits.[27] The Section 45W tax credit provides up to $40,000 for qualified commercial clean vehicles, such as electric school buses. The Section 30C tax credit provides up to $100,000 for qualified charging and refueling infrastructure, for example, in low-income and nonurban areas.

Finally, two of the settlement agreements between Volkswagen corporations and the U.S. government are other sources of funds that have supported the deployment of nondiesel school buses.[28] The settlement agreements required Volkswagen to provide nearly $3 billion for an environmental mitigation trust to fund projects that reduce nitrogen oxides from heavy-duty sources, among other eligible mitigation actions.[29] The trust has funded the replacement of diesel school buses with less polluting buses, among other things.

Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication Among Federal Programs

In February 2010, GAO was statutorily mandated to identify and report annually to Congress on federal programs, agencies, offices, and initiatives—either within departments or government-wide—that have duplicative goals or activities.[30] In related work, GAO reported that executive branch agencies and Congress can improve the efficiency of such federal programs by maximizing the level of services provided for a given level of resources and improving programs’ effectiveness.[31] In addition, opportunities to take action exist in areas where federal programs are inefficient or ineffective because they are fragmented, overlapping, or duplicative. However, having multiple agencies or entities involved in the same programmatic or policy area can, in some cases, be appropriate or beneficial due to the complex nature or magnitude of the federal effort.

Figure 1 provides definitions for the terms fragmentation, overlap, and duplication as used in this report.

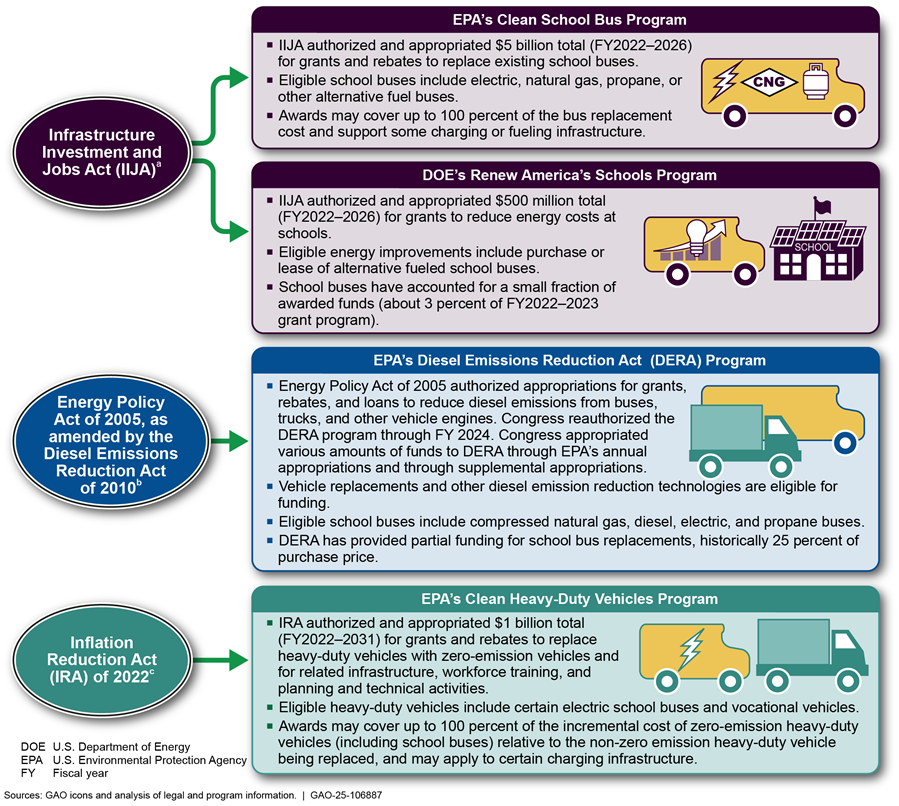

Four Key Federal Programs Help Fund Nondiesel School Buses

Four key federal programs—three at EPA and one at DOE—provide grants, rebates, and loans for nondiesel school buses, as shown in figure 2. EPA’s Clean School Bus program is the only federal program dedicated to replacing existing school buses. EPA’s Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) program helps fund grants and rebates for activities to reduce diesel emissions, with school bus replacements and retrofits constituting the largest segment of funded projects from FY2008 through FY2018. A third EPA program, the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program, provides grants to fund replacements of school buses and vocational vehicles. Finally, DOE’s Renew America’s Schools Program provides grants for energy improvements at public schools, such as improvements to heating and cooling systems or the purchase of nondiesel school buses.

aFor EPA’s Clean School Bus program, see Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 71101, 135 Stat. 429, 1321-1325 (2022) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 16091); 135 Stat. at 1405 (appropriation for the program). For DOE’s Renew America’s Schools program, see Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 40541, 135 Stat. 429, 1071-1074 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 18831); 135 Stat. at 1367 (appropriation for the program).

bEnergy Policy Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-58, §§ 791-797, 119 Stat. 838-844 (referring to these provisions as “Diesel Emissions Reduction”; codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 16131-16137). See also Diesel Emissions Reduction Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-364, 124 Stat. 4056 (2011) (amending the diesel emission reduction provisions of the Energy Policy Act of 2005).

cPub. L. No. 117-169, § 60101, 36 Stat. 1818, 2063 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 7432).

EPA’s Clean School Bus Program

Established under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, EPA’s Clean School Bus program is the only federal program dedicated to replacing existing school buses and accounts for the largest share of federal funding available for school bus replacement. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act appropriated a total of $5 billion over 5 fiscal years for grants and rebates to replace existing school buses, with $1 billion available until expended for each fiscal year from FY2022 through FY2026.[32]

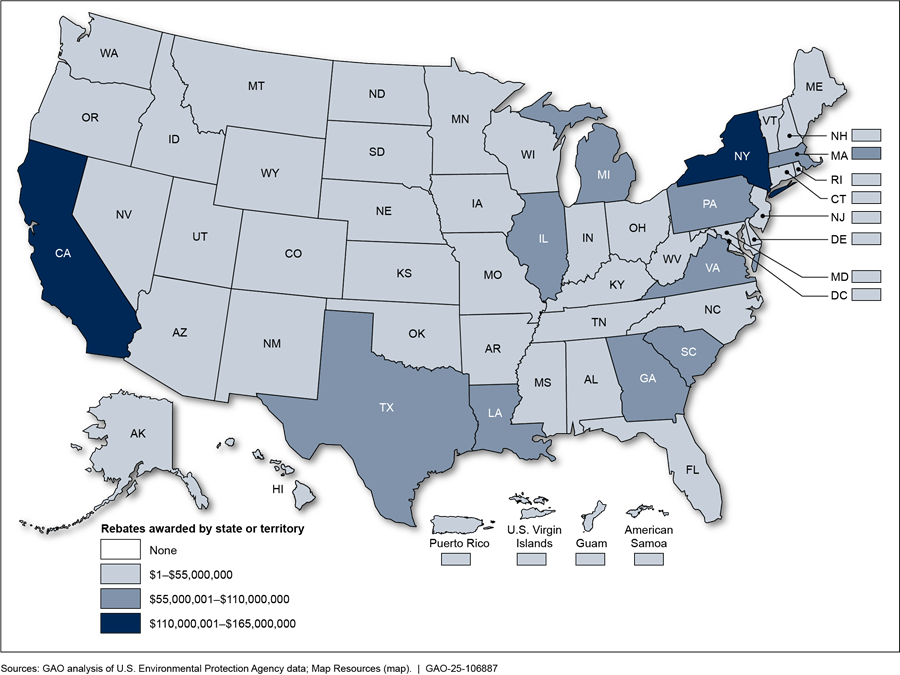

As of January 2025, EPA helped fund school bus replacements through two Clean School Bus rebate programs and one Clean School Bus grant program.[33] Specifically, EPA reported that it obligated approximately $2.8 billion under these three programs to replace about 8,900 school buses as of January 2025.[34] According to EPA officials, the Clean School Bus program has resulted in funding for replacement buses in every state. Figure 3 shows the distribution of rebates under the FY2022 and FY2023 Clean School Bus Rebate programs, according to EPA’s program documentation.[35]

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act directed EPA to award half of the

authorized appropriations for zero-emission school buses (e.g., electric school

buses) and half of the funds for clean school buses (i.e., buses fueled by

compressed natural gas, electricity, propane, or other alternative fuels).[36] Most of the bus replacement awards

were for electric buses, according to EPA’s January 2025 Report to Congress

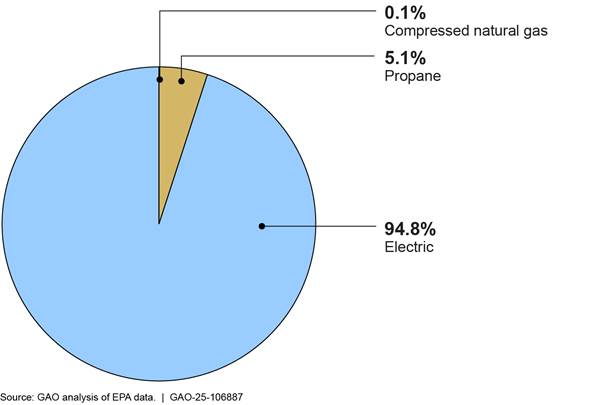

(see fig. 4).

Figure 4: School Buses Funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean School Bus Program, by Fuel Typea

aBased on EPA’s report to Congress, which reported the number of school buses funded by the Clean School Bus program. Specifically, EPA reported the breakdown of buses from the fiscal year (FY) 2022 and FY2023 Clean School Bus Rebate programs, as of September 2024, and the breakdown of buses requested under the FY2023 Clean School Bus Grant, as of December 2023. See EPA, EPA Clean School Bus Program, Fourth Report to Congress, Fiscal Year 2024, EPA-420-R-24-004 (January 2025).

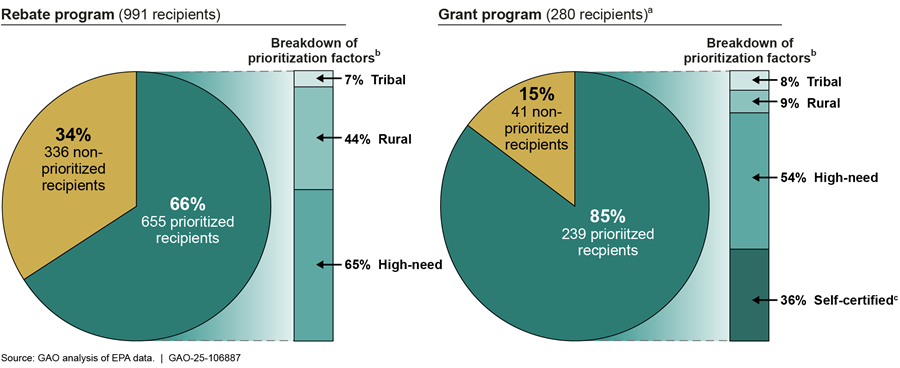

In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allowed EPA to prioritize applicants that serve rural or low-income areas, high-need local education agencies (e.g., qualifying public board of education), and children residing on tribal lands, among other factors.[37] Most grant and rebate award recipients met at least one prioritization criterion (see fig. 5). For example, figure 5 shows that over half of the prioritized rebate recipients met the high-need criterion (65 percent) and just under half of the prioritized rebate recipients met the rural criterion (44 percent). Over half of the prioritized grant recipients also met the high-need criterion (54 percent) though a smaller fraction of prioritized grant recipients met the rural criterion (9 percent). Appendix II provides additional information about key elements of the Clean School Bus program.

Figure 5: Prioritization Status of Recipients of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean School Bus Rebates and Grants

Rebate data are for awards offered under the fiscal year (FY) 2022 and FY2023 Rebate programs. Grant data are for the grants offered under the FY2023 Grant program.

a”Recipients” refer to the school districts receiving grant funds. In some cases, one grant award provided funds to more than one school district.

bSum does not equal 100 percent because some recipients met more than one prioritization factor.

c”Self-certified” refers to applicants that self-certified as low-income, an option that EPA offered to applicants to the FY2023 Clean School Bus Grant program if they met certain conditions. See EPA, 2023 Clean School Bus (CSB) Grant Program: Notice of Funding Opportunity, EPA-OAR-OTAQ-23-06 (April 2023).

The maximum amount of funding that EPA made available for each replacement bus depended on the recipient’s prioritization status, type of replacement bus, and the size of the replacement bus, according to program documents (see table 1). For example, prioritized applicants were eligible for higher amounts of funding per bus than nonprioritized recipients and the maximum per bus funding made available for electric school buses has exceeded the maximum per bus funding available for compressed natural gas and propane buses.

Table 1: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Clean School Bus Fiscal Year 2023 Grant and Fiscal Year 2023 Rebate Programs’ Maximum Funding Available Per Bus

|

|

Type of Replacement School Bus |

||

|

Funding Source |

Compressed Natural Gas |

Propane |

Zero-Emissions |

|

Grant |

|

|

|

|

Prioritized recipients |

$30,000–$45,000 |

$30,000–$35,000 |

$315,000–$395,000 |

|

Nonprioritized recipients |

$20,000–$30,000 |

$20,000–$25,000 |

$195,000–$250,000 |

|

Rebate |

|

|

|

|

Prioritized recipients |

$30,000–$45,000 |

$30,000–$35,000 |

$265,000–$345,000 |

|

Nonprioritized recipients |

$20,000–$30,000 |

$20,000–$25,000 |

$155,000–$200,000 |

Source: GAO analysis of EPA documentation. | GAO‑25‑106887

Note: The maximum funding available per bus for each fuel

type depends on the recipient’s prioritization status and the classification

category of the bus, which is based on a gross vehicle weight rating. EPA’s

classification groups for heavy-duty vehicles range from Class 2b to Class 8,

and the gross vehicle weight as determined by the vehicle manufacturer

increases from Class 2b to Class 8. 40 C.F.R. § 1037.801. The lower number of

each range in this table is the maximum per bus funding level for Class 3–6

buses. The higher number of each range in this table is the maximum per bus

funding level for Class 7+ buses.

EPA officials we interviewed told us that the agency set maximum per bus awards at a level high enough that, in the agency’s judgment, would incentivize entities to apply for funding without inflating market prices for alternatively fueled school buses. Clean School Bus awards may cover up to 100 percent of the cost of a new electric bus but maximum per bus funding levels for electric buses have decreased in each rebate funding opportunity.[38] EPA lowered the maximum per bus award for electric school buses with the goal to encourage lower market prices such that communities could better afford electric school buses after the Clean School Bus program ends, according to agency officials we interviewed.

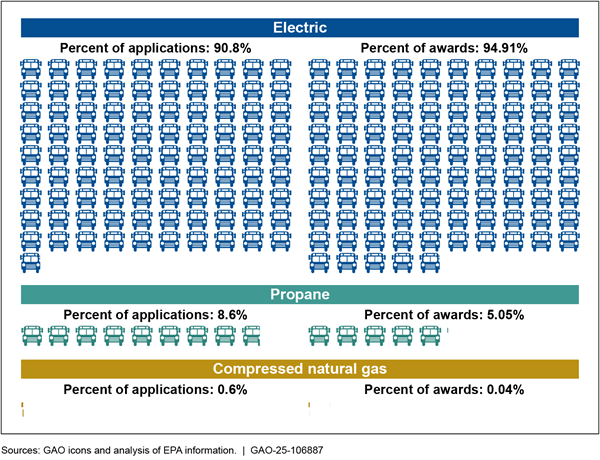

EPA officials we interviewed told us that the vast majority of the applicants requested funding for electric buses and that the percentage of funding awarded by fuel type roughly paralleled the breakdown of the type of buses requested in applications. As an example, figure 6 compares the types of buses requested with the types of buses funded under the FY2022 rebate.

Figure 6: Percent of School Buses Requested and Funded Under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean School Bus Fiscal Year 2022 Rebate Program, by Fuel Type

EPA’s Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) Program

Established in 2005, the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) program provides grants, rebates, and loans for activities, including school bus replacements, to reduce diesel emissions.[39] Numerous types of vehicles and engines, such as school buses, garbage trucks, construction vehicles, and agriculture equipment, are eligible for DERA program funding. EPA has prioritized DERA program funding for projects expected to maximize public health benefits and cost-effectiveness, to serve areas with poor air quality and high population density, and to conserve diesel fuel, among other things. See appendix II for more information about key elements of the DERA program.

The DERA program resulted in the replacement or retrofitting of approximately 73,700 engines or vehicles from FY2008 through FY2018, according to the agency’s most recent DERA report to Congress.[40] Congress has continued to reauthorize the DERA program, most recently through FY2024, and has continued to appropriate funds to the program through FY2024. According to EPA officials, the agency obligated about $470 million for the DERA program from FY2019 through March 2025.

The DERA program has historically helped fund vehicle replacements and other vehicle technologies, including retrofits, engine rebuilds, and fuel switching, to reduce diesel emissions from various sources in the transportation sector. The replacement of school buses and other vehicles has accounted for an increasing percentage of DERA program-funded projects over time, according to EPA officials.[41] According to EPA’s Fifth Report to Congress, school buses constituted the largest segment (43%) of projects funded by the DERA program from FY2008 through FY2018. DERA program funds have also supported projects aimed at reducing diesel emissions from sources in other sectors including agriculture, construction, freight, and ports.

According to EPA’s website, the agency has helped fund school bus replacements through both DERA grants and rebates programs.[42] EPA has selected grant recipients based on an evaluation of application materials and scoring criteria, which reflect statutory and programmatic priorities. By contrast, EPA has used a lottery process to select recipients for the DERA program school bus rebates, according to EPA officials.

As implemented by EPA, the DERA school bus grants and rebates programs generally do not fully cover the purchase price of a replacement bus.[43] Agency officials told us that under the DERA program, EPA set per bus award values based on considerations such as school bus prices, providing eligible applicants an incentive to apply, and maximizing the number of vehicles funded. EPA first offered a DERA School Bus Rebate program in 2012 and awarded recipients rebates from $25,000 to $35,000 per bus, which was about 25 percent of the purchase price for a replacement school bus, according to EPA officials.

Since then, EPA has revised the amount of per bus funding for DERA program projects to better accommodate zero-emission and other nondiesel buses that have higher up-front costs, according to the agency’s DERA Fifth Report to Congress.[44] More specifically, EPA revised the amount of per bus rebate awards based on the fuel type of the replacement bus, with electric vehicles receiving the highest possible rebate amount. For example, EPA’s FY2021 DERA School Bus Rebate program offered $20,000 for diesel or gasoline replacement buses, $25,000 for propane replacement buses, $30,000 for natural gas replacement buses, and $65,000 for electric replacement buses.[45] A second and distinct FY2021 School Bus Rebate program, which used supplemental appropriations from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, offered up to $300,000 per electric bus for up to four electric school buses.[46]

The DERA program has helped fund various types of replacement school buses, including compressed natural gas, diesel, electric, gasoline, and propane buses.[47] The school bus replacements funded under DERA programs (FY2019–FY2021) were primarily new diesel buses, according to EPA documentation (see table 2).[48]

Table 2: Number of Replacement School Buses Funded by Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) Program Fiscal Years 2019 through 2021 (National, State, and Tribal Grants; School Bus Rebates; and American Rescue Plan Rebates, as of March 2025)

|

|

Fuel Type |

||||

|

Program Fiscal Year |

Diesel |

Propane |

Gasoline |

Natural Gas |

Electric |

|

2019 |

934 |

350 |

148 |

13 |

22 |

|

2020 |

975 |

441 |

151 |

16 |

55 |

|

2021 |

768 |

273 |

68 |

1 |

64 |

|

Total |

2,677 |

1,064 |

367 |

30 |

141 |

Source: EPA documentation. | GAO‑25‑106887

Note: Estimated numbers of replacement buses funded by DERA program awards as of March 2025. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers the numbers “proposed” until it receives final vehicle data and closes the DERA program awards.

EPA’s Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles Program

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 appropriated a total of $1 billion from FY2022 through FY2031 for the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program, EPA’s newest program to offer funding for the replacement of heavy-duty diesel vehicles, including certain school buses, with zero-emission vehicles.[49] The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 directed EPA to implement a program for grants and rebates to eligible recipients to help pay for electric and other zero-emission vehicles, fueling and charging infrastructure, and workforce development, among other activities.[50] The statute also directed EPA to award at least $400 million of the total Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles appropriation for projects serving one or more communities in areas that do not meet federal air quality standards. Appendix II provides additional information about key elements of the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program.

EPA’s FY2024 Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles Grant program offered two subprograms—one grant subprogram for school bus replacements and one grant subprogram for vocational vehicle replacements. Vocational vehicles eligible for grants include garbage trucks, street sweepers, transit buses, and other box trucks. According to EPA documentation, the agency plans to allocate 70 percent of Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles grant funds for school bus awards and 30 percent for vocational vehicle awards. In April 2024, EPA announced that it may award up to $932 million under the FY2024 Grant program. According to EPA officials we interviewed, the agency has not determined whether or when it will offer a second Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles funding opportunity.

According to agency officials, EPA selected Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles FY2024 Grant program recipients through an evaluation of application materials and scoring criteria using a point system reflecting statutory requirements and other agency-determined criteria. Specifically, agency officials told us that EPA evaluated applications based on statutorily defined criteria, such as projects being located in areas that do not meet federal air quality standards, and other criteria, such as community engagement efforts, project sustainability, and workforce development activities.[51]

According to EPA documents, under the 2024 Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles school bus grant subprogram, EPA plans to award 75 percent of the purchase price of a new electric school bus, generally up to a cap of $280,000, that applicants may also use to help cover infrastructure costs.[52] In December 2024, EPA announced that it tentatively selected applications to receive a total of approximately $735 million under the FY2024 Grant program, including $490 million to fund about 1,600 new zero-emission school buses and associated eligible infrastructure. According to EPA officials, the agency obligated $634.1 million under the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program for 63 grants, as of February 2025.

DOE’s Renew America’s Schools Program

DOE established the Renew America’s Schools program under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which authorized and appropriated a total of $500 million from FY2022 through FY2026 for the department to fund energy improvements at public schools.[53] Energy improvements, as defined in the statute, include any improvement, repair, or renovation to a school that directly reduces the school’s energy costs, such as improvements to heating and cooling systems, improved lighting, and the installation of renewable energy technologies.[54] In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act identifies the lease or purchase of alternative fueled school buses as an energy improvement eligible for funding.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act directs DOE to prioritize grant applications for schools with renovation, repair, and improvement funding needs; schools with high percentages of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch; schools in a rural area; or schools that leverage private sector funding through energy-related performance contracting. Appendix II provides more information about key elements of DOE’s Renew America’s Schools program.

As of February 2025, DOE implemented two rounds of Renew America’s Schools funding—the FY2022–2023 Grant program and the FY2024–2025 Award program, a multiphase funding process that first awards a cash prize to teams and then awards grants to a subset of the cash prize recipients.[55] While the design of the funding mechanism of the two Renew America’s Schools programs differed, the types of activities eligible for funding were generally the same. Specifically, the FY2022–2023 Grant program and the FY2024–2025 Award program invited applications for energy improvement projects, including alternative fuel school buses, from consortiums of schools and their partners.

As of February 2025, DOE obligated $289 million under the Renew America’s Schools program, including $178 million to 24 recipients for the FY2022–2023 Renew America’s Schools Grant program, according to DOE officials. Two of the 24 recipients planned to use a total of $4.6 million for electric school buses. DOE officials also stated that as of February 2025, the department obligated approximately $111 million under the FY2024–2025 Award program.[56] The FY2024–2025 funding applied to planning and analysis completed by the Award program recipients and did not fund school buses or other energy improvements, according to DOE officials we interviewed.[57]

Fragmentation and Overlap Exist Among Federal Programs for Nondiesel School Buses, and Agencies Have Taken Steps to Address Them

Federal funding for nondiesel school buses is fragmented across two agencies and four programs with overlapping goals, supported activities, and eligible applicants. The fragmentation and overlap among the programs have varying effects. EPA and DOE have taken steps to address these effects. For example, EPA officials considered consolidating the agency’s three school bus funding programs, but ultimately decided against doing so because of the programs’ different statutory requirements and prioritization criteria.

Federal Funding for Nondiesel School Buses Is Fragmented and the Associated Programs Have Overlapping Goals, Supported Activities, and Eligible Applicants

Funding for the four key federal programs for nondiesel school buses is fragmented, according to our analysis of program documentation. As previously discussed, the term “fragmentation” refers to circumstances in which more than one federal agency—or more than one entity within an agency—is involved in the same broad area of national need.[58] Funding for nondiesel school buses is fragmented because two federal agencies—EPA and DOE—manage four programs that address the same broad area of national need to protect children’s health by reducing emissions from school buses.

These four programs were established under different legislation that authorized funding for the deployment of nondiesel vehicles. Specifically, the Energy Policy Act of 2005, as amended, directed the EPA Administrator to implement the DERA program.[59] The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 directed the EPA Administrator to implement a program to replace certain heavy-duty vehicles with zero-emission vehicles.[60] In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act directed the EPA Administrator to implement a program for replacing existing school buses with clean school buses.[61] The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act also directed the DOE Secretary to award grants for energy improvements at public schools, which included the lease or purchase of alternative fueled school buses as an energy improvement eligible for funding.[62] Subsequently, DOE established the Renew America’s Schools program.

The four federal programs that provide grants and rebates for nondiesel school buses also have overlapping goals, supported activities, and eligible applicants. Of the four programs, three share a documented goal of reducing emissions from school buses.[63] All four share the general goal of improving air quality, as shown in table 3. In addition, all four programs can fund similar projects (e.g., the purchase of nondiesel school buses) and include school districts among the eligible applicants. See table 3 for additional examples of overlapping goals, activities, and eligible applicants for the programs.

Table 3: Overlapping Goals, Activities, and Eligible Applicants for Federal Programs that Help Fund Nondiesel School Buses, by Agency and Program

|

|

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

U.S. Department of Energy |

||

|

|

Clean School Bus |

Diesel Emissions Reduction Act |

Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles |

Renew America’s Schools |

|

Program Goalsa |

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce emissions |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Improve air quality |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Deploy low-emissions school buses |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Enhance environmental justice |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Support domestic economy and workforce |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Improve energy performance |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Support strategies to address climate change |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Eligible Activitiesb |

|

|

|

|

|

Purchase alternative fuel vehicles |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Support infrastructure costs |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Fund mechanic or driver training |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Lease alternative fuel vehicles |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Fund other technologies to reduce diesel emissions from vehicles and engines |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

|

Fund other energy improvements (nonvehicular) |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Eligible Applicants |

|

|

|

|

|

State or local agencies (including public schools) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Tribes and territories |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Nonprofit organizations |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Community partnersc |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Contractors providing bus service |

✓ |

✓ |

✗d |

✗ |

✓ = Yes; ✗ = No

Source: GAO analysis of agency information. I GAO‑25‑106887

aSelected program goals were based on the agencies’ program documentation.

bSelected eligible activities and applicants were based on statutory requirements and program documentation.

cCommunity partners refer to entities that have the knowledge and capacity to partner and assist with energy improvements, such as entities eligible for funding under the U.S. Department of Energy’s Renew America’s Schools Program. See 42 U.S.C. § 18831(a)(3)(B)(iv).

dThe Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 directs the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to establish a program to make awards of grants and rebates to eligible recipients, and to make awards of contracts to eligible contractors for providing rebates covering up to 100 percent of the incremental costs of replacing heavy-duty vehicles with zero-emission vehicles and for related infrastructure, workforce training, and planning and technical activities. See 42 U.S.C. § 7432(b). EPA documentation indicates that private contractors were not eligible to apply directly for the fiscal year 2024 Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles (CHDV) grant program. As of November 2024, EPA officials said that they had not offered an opportunity under the CHDV to make awards to eligible contractors for providing rebates.

The Effects of Fragmentation and Overlap Among the Programs Vary

Based on our review of EPA documents and interviews with stakeholders, the effects of fragmentation and overlap among these programs vary. On one hand, the fragmentation in program funding helps to support a greater variety of applicants’ needs. Specifically, our analysis found that the programs’ different prioritization criteria provide a wider range of opportunities for potential applicants than would be available if all the programs used a uniform set of prioritization criteria. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allowed EPA to prioritize certain applicants for the Clean School Bus program (e.g., applicants that serve rural areas, low-income areas, or children living on tribal lands), while the DERA program prioritizes certain projects (e.g., projects that maximize public health benefits and cost effectiveness).

In addition, school districts face less competition for available funding and have more access to funding to replace diesel school buses when multiple funding opportunities are available, according to stakeholders. Meanwhile, demand for funding to replace school buses has been high. For example, EPA reported that it received about 2,000 applications for nearly $4 billion in funding for 2022 Clean School Bus program rebates. Even after EPA increased the rebates available for the FY2022 Rebate program, from $500 million to $965 million, more than 1,500 applicants were placed on a waitlist to receive rebates.[64] Additionally, in 2021, 160 applicants were waitlisted for rebates to replace school buses under DERA.[65]

On the other hand, fragmentation and overlap across the four programs can increase the administrative burden on applicants that wish to apply for funding opportunities from more than one program. For example, portions of the application packages for Clean School Bus, Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles, and DERA program funding require applicants to provide duplicative information. Specifically, the grant funding opportunities under all three programs require applicants to submit certain standardized forms.[66] Consequently, applicants that wish to be considered for funding opportunities under more than one of these programs must submit these forms more than once. Five of the nine school districts we interviewed reported having applied for more than one funding opportunity under EPA’s programs. EPA officials we interviewed said that some applicants asked if they could resubmit past applications during future funding cycles to reduce the work associated with applying. However, these officials told us that resubmitting past applications is not an option because program requirements and applicant information can change from one funding cycle to the next.

Several stakeholders we interviewed, including officials from five school districts and one state agency, told us that grant applications for even one of the four federal programs can be complex, difficult to understand, and time consuming to complete. For example, one school transportation director we interviewed reported that his rural school district had a steep learning curve when applying for funding under DOE’s Renew America’s Schools program. The director said that coordinating with district employees from other departments (e.g., the maintenance department) that were unaccustomed to applying for federal grants was time-consuming. Another stakeholder we interviewed added that school districts often lack dedicated grant writers and school transportation directors often “wear multiple hats,” which may interfere with the time they have to apply for grants.

EPA and DOE Have Taken Steps to Address the Effects of Fragmentation and Overlap

EPA and DOE have taken various steps to address the effects of fragmentation and overlap associated with the programs. For example, EPA officials said that they considered consolidating the agency’s three school bus funding programs. However, the same officials explained that they decided against doing so for the following reasons:

· The programs have different statutory requirements. For example, the statutory requirements for the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program define the vehicles eligible for program funding based on their weight.[67] In contrast, the DERA program allows eligible entities to use program funds for buses, locomotives, marine engines, and other vehicle types.[68] EPA officials told us that addressing the different requirements in one application could create more work for applicants.

· The programs have different prioritization criteria. For example, the Clean School Bus program statutory provisions allow EPA to prioritize applicants from rural or low-income areas.[69] In contrast, DERA requires EPA to prioritize projects that—among other things—maximize public health benefits.[70] EPA officials concluded that even if EPA explained these differences clearly, consolidating programs with differing prioritization factors could prove confusing to applicants.

· Accounting could prove challenging. EPA officials expressed concerns that it could be challenging to account for different program expenditures. These officials explained that the agency is required to keep Clean School Bus funds separate from DERA program funds to ensure that the funds are spent in accordance with the programs’ different statutory requirements.

To address the effects of fragmentation and overlap, EPA also paused the DERA School Bus Rebate program when it began implementing the Clean School Bus program. EPA officials explained that they did so because the Clean School Bus program also provides rebates for school buses. However, EPA continued to award DERA grants and, according to EPA officials, may make DERA school bus rebates available at a future date. In addition, EPA designated one team in the agency’s Office of Air and Radiation to manage the programs. This centralized approach helps program staff collaborate, better ensure EPA and applicants’ compliance with statutory requirements, and strategically pace funding opportunities to avoid overwhelming potential applicants, according to agency officials we interviewed.

Additional steps the agencies have taken to address fragmentation and overlap include interagency coordination. Specifically, program staff from EPA and DOE told us that they met at the outset of the Clean School Bus and Renew America’s Schools programs to discuss their respective plans for designing the programs, implementing the programs, and rolling out funding.[71] Since then, EPA and DOE officials have continued to meet both formally and informally to discuss topics such as the status of program implementation, whether either agency has implemented programmatic changes, and expectations for next steps, according to DOE officials we interviewed.

Finally, EPA officials told us that they have taken several steps to reduce the time and resources needed to apply to more than one of these programs. For example, EPA has disseminated fact sheets and other relevant information on the website for each program. EPA also has coordinated with DOE and the Joint Office, which provides technical assistance and resources for program applicants.[72]

EPA and DOE Collect Information to Track Programs’ Performance but Opportunities Exist for EPA to Better Assess Progress Toward Program Goals

EPA and DOE collect certain information to track progress toward achieving the goals of key programs that help fund nondiesel school buses. Specifically, EPA collects and uses information to track progress toward the program goals of the Clean School Bus and DERA programs.[73] DOE collects information on the performance of the Renew America’s Schools program and has provided training to grant recipients to support reporting accurate and complete information about funded activities and results to DOE. However, EPA has opportunities to better assess progress toward achieving Clean School Bus and DERA program goals.

EPA and DOE Collect Performance Information to Track Progress toward Program Goals

EPA Collects and Analyzes Performance Information

EPA collects performance information from Clean School Bus and DERA funding recipients to track progress toward achieving program goals.[74] Performance information, a type of evidence, refers to quantitative or qualitative data used to assess the performance of a program.[75] Clean School Bus and DERA program funding recipients provide performance information to EPA in reports about funded activities and results, as required by the Clean School Bus and DERA programs. Examples of performance information collected by EPA include the number of buses replaced using funds from the two programs and the purchase price of replacement buses. Table 4 provides additional examples of performance information that EPA requests from funding recipients, along with examples of related program goals.

Table 4: Examples of Performance Information and Related Program Goals for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Programs

|

Program |

Examples of performance information requested by EPA |

Examples of program goals relevant to the performance information |

|

EPA’s Clean School Bus Program |

|

|

|

Grant |

Number of buses delivered, types of chargers, expectations for use of new bus (e.g., mileage, location), duration of battery or powertrain warranty, proof of scrappage. |

Deploy low-emissions school buses, reduce emissions, improve air quality |

|

Rebate |

Closeout form documents delivery of new bus, purchase of charging infrastructure, proof of scrappage. |

Deploy low-emissions school buses |

|

EPA’s Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) Program |

|

|

|

National Grant |

Document scrappage, gallons of fuel saved, tons of emissions reduced. |

Deploy low-emissions school buses, reduce emissions, improve air quality |

|

School Bus Rebate |

Document delivery of new bus and scrappage of replaced bus. |

Deploy low-emissions school buses |

|

EPA’s Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles Program |

|

|

|

Grant |

Number of buses replaced, types of chargers, expectations for use of new bus (e.g., mileage, location), duration of battery or powertrain warranty, proof of scrappage. |

Deploy low-emissions school buses, reduce emissions, improve air quality |

Source: GAO analysis of program guides and interviews with

EPA officials. I GAO‑25‑106887

Grant recipients from all three programs must submit interim progress reports and a final report that describe the recipient’s vehicle fleet and discuss any problems, successes, and lessons learned. EPA has developed fillable spreadsheet templates for recipients of the three grant programs that may help standardize the information reported, such as specifications of the replacement bus, along with open-ended questions about problems, success, and lessons learned.

In contrast, the Clean School Bus and DERA School Bus Rebate program recipients submit simpler forms to document bus purchase and do not report information about problems, successes, or lessons learned. For example, the Clean School Bus Rebate recipients are required to submit two basic forms. One form documents that they ordered their replacement school buses and requests the rebate payment. The second form documents proof of purchase, delivery of the replacement school bus, and provides evidence that the replaced bus was destroyed. DERA School Bus Rebate program recipients are also responsible for submitting a payment request form and supporting documents, including proof of scrappage of the replaced vehicle and proof of the new vehicle delivery or technology installation. In addition, EPA has provided resources to support submission of forms under both rebate programs. For example, EPA hosted a webinar to review the requirements of the closeout process, including the closeout form, for the FY2022 Clean School Bus Rebate program.

EPA uses the performance information to track progress toward the goals of the Clean School Bus and DERA programs. For example, EPA has begun collecting information under the Clean School Bus program, such as the number and type of replacement buses purchased with program funds, to track progress toward the program’s goal of deploying low emissions school buses. EPA has also used information about DERA program-funded replacement school buses, such as vehicle specifications, to estimate emission changes and track progress towards the DERA program’s goal to reduce emissions.[76] Additionally, under the DERA program, EPA uses information about the volume of fuel saved to track progress toward the program’s fuel conservation goal.

EPA reports its assessments of progress toward Clean School Bus and DERA program goals to Congress. Specifically, EPA has published four annual reports for Congress that provide information about the design and implementation of the Clean School Bus program.[77] EPA’s Clean School Bus reports have described program goals and provided information about the awards issued—such as number of selectees, the geographic distribution and prioritization status of selectees, and the number of buses and level of funding awarded. EPA has also published five reports for Congress that summarize the results of DERA program projects, such as reductions in fuel use and in diesel emissions. The fifth and most recent DERA report to Congress summarizes results from the FY2008 through FY2018 DERA programs and provides additional details about FY2017 and FY2018 DERA program projects.[78]

DOE Collects Performance Information and Plans to Report Progress toward Program Goals

DOE has begun collecting performance information from reporting forms submitted by recipients of grants under the Renew America’s Schools program. Examples of the performance information DOE collects include the type of energy efficiency technology installed and any associated changes in energy consumption, which may help the department track progress toward the program’s goal to improve energy performance.

DOE officials told us in November 2024 that the department has supported reporting of accurate, complete, and consistent information across the program’s projects by providing standardized forms and offering training regarding use of the forms. For example, in the fall of 2024, DOE provided training for using seven reporting forms designed to collect information about the results of funded activities and progress toward program goals, including improvements in energy performance, workforce development, and enhancement of environmental justice.

DOE has published limited information about progress toward program goals partly because the program is new. DOE has reported program funding, and the number of students and teachers expected to benefit from the energy improvement projects on the program website. In addition, DOE has not yet quantified progress toward program goals, such as energy cost savings and the development of healthier learning spaces.

According to DOE officials we interviewed, recipients of FY2022–2023 Grant program funding submitted the required reports, which document progress toward goals, to the department by the end of 2024.[79] DOE officials stated that the department will use the reports to track program-wide progress toward achieving program goals. In particular, the officials said that, as of November 2024, they expected to aggregate project-specific information to the program-level and report program outcomes but had not yet determined how or when it would do so.

EPA Has Opportunities to Use Key Practices to Better Assess Progress Toward Achieving Program Goals

EPA has opportunities to better assess progress in achieving the goals of its Clean School Bus and DERA programs. These opportunities are based on key practices we have identified for assessing performance information to measure the results of federal efforts. We identified two opportunities, based on our analysis of agency documentation and interviews with agency officials, for EPA to assess the sufficiency of existing evidence and build on it to improve how the agency tracks progress toward certain goals of the Clean School Bus and DERA programs.[80] These two opportunities involve systematically tracking performance information and building comprehensive information about emission reductions.

Key Practices for Assessing Results of Federal Efforts

Our past work has identified key practices for assessing the results of federal efforts and highlighted the importance of assessing the sufficiency of performance information and building evidence that federal agencies use to assess progress towards achieving program goals.[81] Assessing the sufficiency of performance information and other forms of evidence includes (1) considering the quality of gathered evidence, such as completeness and timeliness of information, and (2) determining whether the gathered evidence is sufficient to understand progress toward goals. Building evidence involves ensuring that the new evidence would support the agency’s assessment of progress toward program goals.[82]

Opportunity to Systematically Gather Performance Information Related to Bus Deployment

EPA has an opportunity to build more complete and timely performance information to improve how the agency tracks progress toward the goal of the Clean School Bus program to deploy low-emissions school buses. In particular, EPA has an opportunity to more systematically gather information to verify that buses have been deployed and track factors that may hinder progress toward deployment of buses.

According to EPA’s 2025 Clean School Bus report to Congress, one of the largest hurdles to reaching closeout and deploying replacement buses has been planning for, financing, and installing electric bus charging infrastructure.[83] The school officials we interviewed echoed this view. For example, one school official described challenges with charging infrastructure that delayed the deployment of one new bus, which sat unused for about 9 months. Officials from a different school told us that infrastructure-related delays have consequences for the bus warranty period because the warranty clock starts once the bus is delivered, regardless of whether the infrastructure is ready. EPA officials told us that the agency has sought to address the infrastructure challenges by working with interagency partners and stakeholders to develop technical assistance and educational resources that are responsive to stakeholder needs.

EPA does not systematically collect complete performance information from rebate recipients to verify that buses have been successfully deployed or to track factors—such as infrastructure delays—that may hinder progress toward bus deployment. Rather, EPA gathers limited information at the end of the project through the rebate closeout form, which provides documentation that the rebate recipient received the replacement buses and scrapped the replaced buses. However, EPA may not be able to determine from this information whether replacement buses have been deployed or if their deployment was delayed.

A December 2024 report by EPA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) also determined that EPA should have developed controls to help ensure that the agency was aware of deployment status to determine whether schools would have new buses in operation by the October 2024 deadline.[84] Accordingly, the OIG recommended that the assistant administrator of EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation develop and implement guidance for Clean School Bus program personnel reviewing rebate recipients’ use and management of rebate funds.[85]

In addition, EPA does not have timely information about potential deployment delays because many of the Clean School Bus rebate recipients had not completed the rebate forms by the October 31, 2024, deadline.[86] EPA’s awards website reports that, as of April 2025, recipients submitted closeout forms for about 72 percent of the FY2022 rebate awards.[87] EPA’s awards website does not specify when the remaining 28 percent will close out. According to EPA officials, the agency granted extensions beyond the October 2024 deadline to some recipients upon request. Specifically, recipients that anticipated not being able to meet the October 2024 deadline had the option to submit requests for extensions to EPA beginning in July 2024 (i.e., the last 4 months of the 24-month project period). EPA officials told us that when requesting an extension, recipients must describe areas where progress is being hindered, such as delays related to bus delivery or charging infrastructure. According to EPA’s documentation, the agency may grant extensions if recipients provide “sufficient justification.”[88]

EPA officials we interviewed stated that they learned about some delays through recipients’ requests for extensions to the deadline for closeout forms. Agency officials further noted that EPA encourages rebate recipients to contact the agency as well as the Joint Office for support resolving problems they encounter deploying new buses. Beyond the FY2022 Rebate program, EPA officials also told us that the agency has partnered with the Joint Office to ensure the Joint Office proactively reaches out to recipients of the FY2023 Rebate program to offer support with deploying new buses.

Aside from the recipients that request extensions, however, the agency does not systematically gather timely information that may provide assurance about whether rebate recipients resolved challenges or successfully deployed the new school buses. For example, the rebate reporting form does not ask recipients to verify the deployment of buses or otherwise discuss progress using the rebate funds. In addition, EPA did not proactively monitor whether recipients of the FY2022 Rebate program were on track to meet the closeout deadline. Instead, EPA relied on the rebate recipients’ assessment of whether they would miss the closeout deadline and the submission of extension requests in the final months of the project period to gauge progress toward closeout.

By systematically gathering more complete and timely performance information about bus deployment EPA could more effectively assess progress toward closeout and achievement of program goals. In particular, EPA could better manage the extent to which difficulties encountered by funding recipients, such as delays installing charging infrastructure, put federal investments in nondiesel school buses at risk.

In February 2025, EPA proposed to collect additional information from recipients of Clean School Bus rebates in response to a recommendation from EPA’s Office of the Inspector General.[89] Specifically, the agency stated that it planned to “introduce semi-annual progress reports” in future Clean School Bus rebate funding opportunities. Such reports, if used to systematically collect information from recipients about factors affecting bus deployment, could help provide EPA with more complete and timely information to assess progress toward achievement of program goals.

Opportunity to Build Comprehensive Information About Emission Reductions

EPA has an opportunity to develop more comprehensive information to track progress toward Clean School Bus and DERA program goals to reduce emissions and improve air quality. For example, more comprehensive performance information would include complete and timely information to estimate emission reductions resulting from each of the agency’s key programs funding nondiesel school buses.

EPA used performance information and emission models to project the reductions of nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and other pollutants from school buses funded under the FY2022 Clean School Bus Rebate program.[90] However, the estimates do not provide comprehensive information about progress toward the program’s goal to reduce emissions because the agency’s methodology does not include emissions related to electricity used to charge buses.[91] While electric buses produce no tailpipe emissions, the generation of electricity to charge the buses can produce air pollution, such as emissions of nitrogen oxides. Given the significant fraction of electric buses funded by the Clean School Bus program (about 95 percent), estimates that do not include emissions associated with charging electric vehicles may result in misleading assessments of progress toward the program’s goal to reduce emissions.[92]

EPA expects to refine the estimated emission reductions as additional information becomes available, according to the Fourth Report to Congress.[93] EPA officials we interviewed told us that while they do not yet have a methodology to characterize emissions associated with charging electric school buses, the agency is evaluating data sources and considering ways to characterize such emissions.

In addition, EPA has not estimated emission reductions for DERA school bus replacements since the agency made such estimates for the DERA FY2018 Grant and School Bus Rebate programs. Agency officials described the calculation and reporting of emission reductions as a time-intensive process and clarified that the agency does not report the reductions until final vehicle data are submitted to agency and the grant or rebate has been closed out. Also, the agency has not updated the methodology or estimated emission reductions from the electric school buses funded by the FY2021 DERA-American Rescue Plan Rebates program, according to EPA officials.

Agency officials stated that they would like to build on the methodology developed for the Clean School Bus program and apply it to the DERA and Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles programs. EPA officials clarified that the methodology for each program will need to account for varying statutory requirements, such as the types of vehicles funded by each program. It is unclear whether the agency’s estimates will be consistent or comparable across programs.

Our prior work has found that federal decision-makers need information about the extent to which federal programs are achieving their intended results.[94] Developing a methodology to characterize emissions related to charging electric school buses and estimating emissions reductions from the agency’s key programs would help EPA better understand the extent to which the billions of dollars invested in school bus replacements contribute to the goals of the Clean School Bus and DERA programs to reduce emissions. As EPA administers the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles Grant program, this type of methodology would also help EPA better assess the extent to which the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicle program’s investment in school bus replacements contributes to the program’s goal to reduce emissions.

Conclusions

The federal government has invested billions of dollars to replace existing school buses with less polluting buses fueled by alternatives to diesel, such as electricity or propane. These investments have primarily come through four key programs. Three are EPA programs—the Clean School Bus program, DERA, and the Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles program—and the fourth is DOE’s Renew America’s Schools program. The Clean School Bus program, the largest of these programs, has obligated about $2.8 billion, mostly for electric buses, since the program’s establishment in 2022.

This level of investment brings a particular importance to ensuring that the programs are achieving their goals, which include deploying low-emissions buses and reducing emissions. EPA and DOE have collected some information to track their programs’ performance, but EPA has opportunities to better assess progress toward certain program goals—particularly for the Clean School Bus and DERA programs—by building more complete and timely information related to the programs’ performance. Specifically, EPA has opportunities to:

· More systematically gather information to (1) verify deployment of low-emissions buses funded under Clean School Bus program rebates and (2) to track factors—such as delays in installing charging infrastructure—that have hindered bus deployment, and

· Build more comprehensive information to assess emissions reductions by developing a methodology that includes emissions related to charging electric buses. Such emissions are not currently included in EPA’s estimates.

By acting on these opportunities, EPA could better manage the extent to which factors like delays in installing electric bus charging infrastructure put federal investments at risk. EPA could also better understand the extent to which the billions of dollars invested in school bus replacements reduce emissions.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to EPA.

The Assistant Administrator of EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation should gather complete and timely performance information—through rebate closeout forms or other mechanism—to verify the successful deployment of nondiesel school buses funded by Clean School Bus program rebates and track factors that may hinder progress toward bus deployment. (Recommendation 1)

The Assistant Administrator of EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation should develop a methodology to characterize emissions related to charging electric school buses and estimate emission reductions from each of the agency’s key programs funding nondiesel school buses. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOE and EPA for review and comment. DOE provided written technical comments that we incorporated as appropriate. EPA provided written comments that are reproduced in appendix III and summarized below. In their comments, EPA generally agreed with our recommendations to the agency. EPA also provided technical comments that we incorporated as appropriate.

In written comments, EPA agreed with our recommendation that the agency gather complete and timely information to verify the successful deployment of buses funded by its rebate program. EPA also described actions it is taking and characterized them as consistent with our recommendation. For example, EPA stated that it requires rebate recipients to submit a closeout form to verify that new buses were deployed, and older buses were appropriately dispositioned. However, we found that the closeout forms document the receipt of new buses and disposition of the replaced bus, but not deployment of the new buses. As a result, EPA may be unable to use closeout forms to verify whether bus deployment occurred, whether deployment was delayed, or what factors contributed to any delays. Our report also showed that EPA did not proactively monitor whether recipients of the FY2022 Rebate program were on track to meet the closeout deadline. Updating the closeout form to explicitly require recipients to provide such information could help provide a mechanism for EPA to verify the successful deployment of nondiesel school buses and track factors that may hinder progress toward bus deployment.

EPA also stated that it began conducting in-person site visits in Fall 2024 to verify the successful deployment of nondiesel school buses and expects to continue site visits at an increased pace through Fall 2025. However, to meet the intent of our recommendation, EPA would need to design site visits to ensure they would systematically provide timely information about bus deployment and factors affecting delays for all rebate recipients. By systematically gathering more complete and timely performance information about bus deployment, EPA could more effectively assess progress toward rebate closeout and achievement of program goals.

In written comments, EPA stated that it generally agreed with our recommendation concerning estimates of emission reductions from each of the agency’s nondiesel school bus programs. EPA also stated that data availability may affect the agency’s ability to develop a methodology to characterize emissions related to charging electric school buses. EPA added that it will continue to actively explore available data and tools to inform a methodology that can appropriately characterize emissions from charging electric school buses.

We recognize the importance of assessing whether tools, data, and resources allow quantification of emissions from vehicle charging and note that some existing tools may serve as a starting point for this assessment. For example, EPA’s Power Profiler interactive web page allow users to determine the energy mix by region, and DOE and EPA’s Beyond Tailpipe Emissions Calculator can help users estimate emissions associated with charging and driving an electric vehicle in a given zip code.[95] Our report discussed the importance of building more comprehensive information to assess emission reductions, which would allow EPA to better understand the extent to which the billions of dollars invested in school bus replacements reduce emissions.

As agreed with your office, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Administrator of EPA, and the Secretary of Energy. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at gomezj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Sincerely,

J. Alfredo Gómez

Director, Natural Resources and Environment