PUBLIC HEALTH PREPAREDNESS

Reliable Information Needed to Inform Situational Awareness of the Medical Reserve Corps

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑106899. For more information, contact Mary Denigan-Macauley at DeniganmacauleyM@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑106899, a report to congressional committees

Reliable Information Needed to Inform Situational Awareness of the Medical Reserve Corps

Why GAO Did This Study

Public health emergencies, such as those resulting from wildfires, hurricanes, and infectious disease outbreaks can be devastating. The MRC is a national volunteer network of medical and other health professionals, comprised of approximately 700 local units. These volunteer resources are accessible to states, territories, and localities for workforce support in emergencies.

The Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2019 includes a provision for GAO to review states’ use of health care volunteers in public health emergencies. This report is follow-up work to our previous reporting and (1) describes MRC leaders’ experiences using volunteers, (2) identifies the assistance HHS provided during emergency response, and (3) assesses information HHS uses to maintain situational awareness.

GAO reviewed agency documentation and interviewed department officials on assistance provided during emergency response, and submission of quarterly capability information. GAO also interviewed MRC leaders in six states and Puerto Rico.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to improve HHS’s ability to maintain situational awareness by (1) developing mechanism(s) to ensure volunteer data are updated and (2) ensuring technical assistance assessments are completed annually, as required. HHS concurred with both of GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leads the nation’s medical and public health preparedness and response to emergencies. In this role, HHS oversees the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC), which provides medical and nonmedical support during and after disasters at the state and local level.

MRC volunteers were essential in the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergencies, according to MRC leaders from six states and one territory. For example, in 2021, Colorado deployed volunteers to provide medical care at wildfire shelters and distribute tests for COVID-19. Volunteers in Hawaii had multi-day deployments providing medical support to displaced individuals in the 2023 wildfire response.

HHS assisted the MRC by providing funding, technical assistance, training, and guidance. To boost the MRC network after the COVID-19 pandemic response, in 2023, HHS made awards to 33 states and jurisdictions. These awards ranged from $376,000 to $2.5 million.

HHS relies on MRC network unit information—such as volunteer data and technical assistance assessments—to maintain situational awareness of its capabilities. However, GAO found that volunteer data were unreliable. For example, as of July 2024, about 70 percent of all MRC units’ volunteer counts did not indicate when the data were updated. In addition, units are to update data quarterly. However, 41 percent of MRC units’ reported number of volunteers remained unchanged from 2020 to 2023, though MRC leaders from selected states told GAO that the number of volunteers was significantly higher during the height of the pandemic and later declined. In both instances, HHS was unable to confirm whether units were making the required data updates or whether there was no change. Moreover, some of the unit leaders GAO spoke to confirmed they did not update the volunteer counts for their units as required by HHS. GAO also found that HHS staff had not always conducted required annual technical assistance assessments of the capabilities of the MRC units. Without ensuring regular Medical Corps data updates and technical assistance assessments, HHS risks having incomplete situational awareness as the coordinator for public health and medical emergency preparedness and response.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ASPR |

Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

MRC |

Medical Reserve Corps |

April 3, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Public health emergencies, such as those that result from wildfires, floods, hurricanes, and infectious disease outbreaks can be devastating. During the COVID-19 pandemic alone, more than 1.1 million U.S. deaths were reported as of June 2023.

Physicians, nurses, and others can volunteer in their communities to help people affected by public health emergencies through the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC). This national network of approximately 700 health care volunteer units, established by the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, provides medical and nonmedical support during and after disasters.[1] Since 2020, the MRC has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in addition to other emergencies, including mpox outbreaks and natural disasters, which we have reported are on the rise.[2]

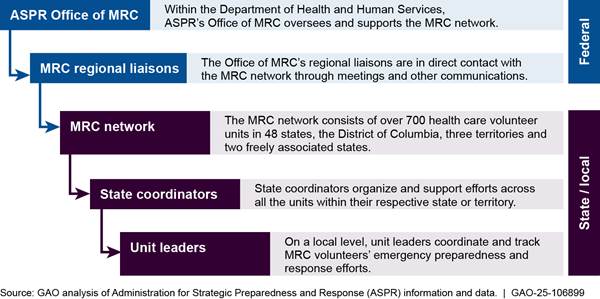

The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), oversees the MRC program and provides guidance and resources to the MRC network, as part of its charge to lead the public health and medical response to national emergencies.[3] Specifically, ASPR leads the public health and medical services support function of the National Response Framework—an all-hazards response structure to coordinate federal, state, territory, and local resources during emergencies and disasters.[4] In this role, ASPR serves as the federal focal point for coordinating public health and medical emergency response support, which includes maintaining situational awareness of the number and capabilities of volunteers in the MRC network.[5]

As we reported in January 2022, for more than a decade, we have found persistent deficiencies in the ability of HHS and its component agency, ASPR, to perform their roles of leading the nation’s public health and medical preparedness for, and response to, emergencies.[6] At that time, we placed HHS’s leadership and coordination of a range of public health emergencies on our High-Risk List, in part due to concerns related to HHS’s lack of situational awareness capability.[7] These deficiencies have hindered the nation’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and to a variety of past emergencies, including hurricanes, wildfires, and other disease outbreaks.

The Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2019 includes a provision for us to review states’ use of health care volunteers in the event of a public health emergency.[8] This report, which we began in 2019 and paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic response, is follow-up work to our previous reporting.[9] This report

1. describes the experiences of leaders of selected states’ Medical Reserve Corps in using volunteers in emergency response;

2. identifies the assistance ASPR provided to the national Medical Reserve Corps network in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergencies; and

3. assesses the information ASPR uses to maintain situational awareness of the Medical Reserve Corps network.

To describe selected states’ MRC leaders’ experiences in using volunteers to respond to emergencies, we reviewed ASPR documentation on the COVID-19 pandemic response and interviewed selected MRC leaders—state coordinators and local unit leaders—in six states and one territory (collectively referred to as “seven selected states”) and 22 units among the selected states. We selected states that had an active MRC program during our review period, used volunteers to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and experienced at least one hurricane, tornado, fire, or flood between 2021 and 2023.[10] We also selected states with large, medium, and small volunteer counts relative to the states’ population size.[11] Based on these criteria, and to incorporate geographic variation, we selected Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Puerto Rico, Texas, and Vermont.

During our interviews with the state coordinators, we obtained their input on MRC potential interviewees and outreach to MRC units, and interviewed leaders of two to six MRC units in each state. In total, we interviewed six of the seven state coordinators and 22 local unit leaders on the administration of the MRC and their experiences in using volunteers in emergency response, including successes and challenges.[12] For six of the seven selected states, we also interviewed volunteers deployed to respond to an emergency in their state during our review period on their experiences joining the MRC, as well as the successes and challenges experienced while volunteering.[13] We interviewed 31 total volunteers we identified with the assistance of the MRC unit leaders in the six states. The views and experiences of MRC leaders and volunteers in the selected states and units are not generalizable to the other MRC states, units, and volunteers.

To identify the assistance ASPR provided the national MRC network in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergencies, we reviewed documentation from ASPR that detailed the responsibilities of its Office of the Medical Reserve Corps for the MRC network. This included guidance, strategic plans, and other documents that described ASPR officials’ expectations and activities to assist the MRC network. We also interviewed officials from ASPR’s Office of the Medical Reserve Corps, including eight of the ten regional liaisons, to better understand their roles and responsibilities related to assisting the MRC network.[14] In addition, we interviewed selected states’ MRC leaders—MRC state/territory coordinators and unit leaders—to better understand their experiences with the assistance ASPR provided them during the COVID-19 pandemic and other concurrent emergencies. We assessed ASPR’s identified efforts using the emergency support function #8, within the National Response Framework.[15] This support function calls for coordinating assistance to respond to an actual or potential public health or other disaster or incident that may lead to an emergency.

To assess the information ASPR uses to maintain situational awareness of the MRC network, we reviewed ASPR’s MRC unit data and documentation that described the agency’s data review practices. Specifically, we reviewed ASPR procedure guides and manuals provided to MRC unit leaders and ASPR staff that describe the purpose of the data, and how guidance directs them in inputting or reviewing the data. We also interviewed ASPR staff to learn about how they use the data, as well as their data review training and practices, and to compare the staffs’ practices to ASPR’s data review procedures. Further, during our interviews with the MRC leaders from the selected states we asked about their data reporting training and practices. Among the 22 selected units, we also sent the unit leaders a questionnaire about their frequency in updating their unit’s data in ASPR’s reporting system and any barriers in reporting in the system.[16]

We also reviewed ASPR’s MRC unit data from 2020 to 2023, which contained units’ volunteer counts. This time frame included MRC unit data from before this work’s pandemic-related pause in 2020, and resumed following our September 2020 previously issued work, which reported on data through September 2019. [17] We analyzed the data to find the frequency of volunteer count changes for applicable units from 2020 through 2023. We also obtained volunteer data from MRC units as of July 2024, to analyze and examine against ASPR’s descriptions of their data reliability processes. We determined that the data were not sufficiently reliable for the purpose of affirming their level of accuracy for use in maintaining situational awareness nor for the purpose of us to report MRC volunteer counts and trends for context to our findings. We assessed the information related to situational awareness reported by ASPR and the MRC units against ASPR’s policy documents, its Office of the Medical Reserve Corps’ priority to improve data, as well as internal control standards for the federal government.[18]

We conducted this performance audit from June 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

ASPR, on behalf of the Secretary of HHS, is to lead the public health and medical services response for the National Response Framework during a disaster, emergency, or incident that may lead to a public health emergency.[19] Under this framework, ASPR’s responsibility is to coordinate the assistance and associated capabilities provided in response to an actual or potential public health and medical disaster or incident, including medical surge support.[20] While local, state, tribal, and territorial area officials retain primary responsibility for meeting public health and medical needs, ASPR is responsible for coordinating with these jurisdictions to integrate federal assets with state plans and assets. This can include civilian volunteers deployed from local, state, and other authorities, including those deployed through the MRC. (See fig. 1.)

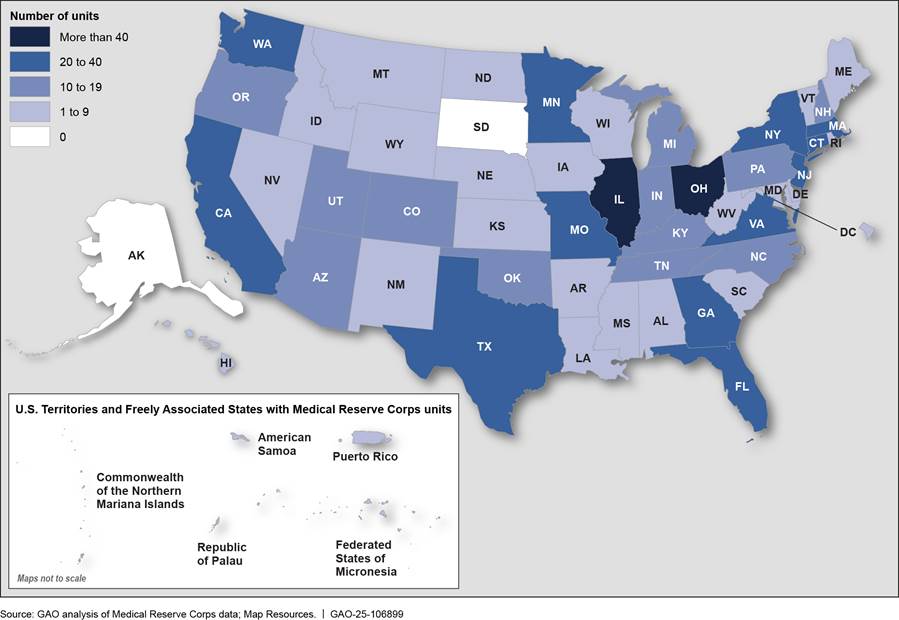

The MRC network consists of medical, public health, and nonmedical professional volunteers in geographic jurisdictional units across the United States, who aim to strengthen public health emergency response capabilities and build community resiliency. These volunteers can prepare for and, upon jurisdictional needs, respond locally, and at the direction of, local or state officials to natural disasters and other emergencies that affect public health, such as infectious disease outbreaks. Units are located across the country and the number of MRC units within each state or territory varies (See fig. 2.)

Note: There were no MRC units registered in Alaska and South Dakota as of July 2024.

ASPR sets requirements for units to be included in the national MRC network, such as reporting unit data and information to ASPR’s Unit Profile and Activity Reporting system (ASPR’s reporting system) and being affiliated with a sponsoring organization such as a health department. MRC leaders may be paid state, local, school or non-governmental organization employees or unpaid volunteers, and they can register new MRC units using an online process. (See fig. 3 for MRC structure).

In the event of a public health emergency, such as an infectious disease outbreak, local MRC units may deploy their units’ volunteers to help augment emergency response efforts. MRC volunteers can also participate in non-emergency activities, including flu vaccine clinics, health fairs, and trainings, such as CPR and “Stop the Bleed.”[21]

Note: The MRC network, which represents the state and local level, can be associated with government entities, as well as universities and non-governmental organizations.

ASPR is responsible for monitoring the MRC. This includes maintaining situational awareness of the MRC network by overseeing the data MRC unit leaders are required to report to ASPR’s Unit Profile and Activity Reporting system (ASPR’s reporting system). It also includes understanding units’ activities, capabilities, resources, and needs during emergencies and periods when there are no emergencies.

Selected States’ MRC Leaders Described Benefits and Challenges in Volunteer Responses and Most Plan to Focus on Volunteer Retention Going Forward

MRC Leaders Found Volunteers Essential in Emergency Response and Noted Challenges

MRC unit leaders and state coordinators (MRC leaders, hereafter) from all seven selected states in our review said MRC volunteers were essential in the COVID-19 pandemic and other public health emergency responses.[22] The MRC leaders we spoke with described the benefits of using volunteers to respond to the pandemic and other emergencies. MRC leaders we spoke with also described challenges in managing emergency responses with volunteers, including volunteer participation and the volunteer application process.

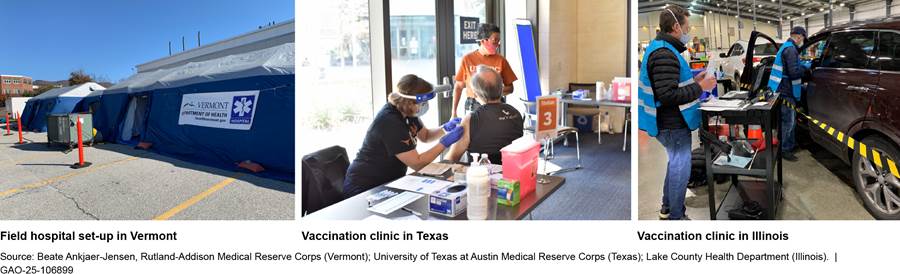

Benefits of MRC Volunteer Use in COVID-19 Response

During the COVID-19 pandemic, MRC leaders in selected states noted that MRC medical and nonmedical volunteers were beneficial in their assistance with call centers and providing education; offering medical screenings and contact tracing; staffing mobile clinics; and implementing large-scale events, such as participating in mass COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites.[23] (See fig. 4.) MRC volunteers with medical professional backgrounds were used for both clinical volunteer activities and non-clinical activities. MRC leaders from three of our seven selected states said MRC volunteers in the COVID-19 response were used to assist in local hospitals or public health departments; these volunteers were involved in food delivery, call center, and contact tracing activities.

MRC unit leaders from four selected states said certain response activities, such as mass vaccination clinics, would have been impossible to conduct without the MRC volunteers, and noted the extended time frame of some of the COVID-19 response activities, many spanning multiple months. MRC leaders from two of the seven selected states also described how there were volunteers who provided immense and long-term support over multiple efforts. For example, one volunteer participated in 70 vaccination clinics over the duration of the pandemic. MRC volunteers we interviewed told us they enjoyed volunteering with their MRC units to respond to the pandemic and other emergency responses, and some noted they felt valued for their contributions to MRC emergency response activities.

Benefits of Use of MRC Volunteers in Other Public Health Emergencies

MRC leaders in four of the seven selected states in our review also noted the benefits of deployment of volunteers to respond to natural disasters between 2020 through 2023. These MRC volunteer deployments to other emergencies included assistance with Hurricane Douglas and wildfires in Hawaii, Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico, Colorado wildfires, and Vermont flooding.

|

Maui Wildfires

In August 2023, the U.S. experienced the deadliest wildfire in over a century on the island of Maui in Hawaii. Multiple fast-moving fires spread across Maui, devastating the town of Lahaina, claiming 100 lives, and displacing nearly 10,000 survivors. Local units of volunteers from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Medical Reserve Corps provided public health and medical support to fire survivors. Sources: GAO‑24‑107382 (information), Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (information), GAO (photo). | GAO‑25‑106899 |

Hawaii hurricane and wildfire help. Hawaii deployed MRC volunteers to respond to Hurricane Douglas in 2020 and the wildfires in Maui in 2023 (see sidebar). Volunteers were deployed to staff shelters during the hurricane and provided additional services such as food preparation and medication delivery to residents quarantined due to the pandemic, according to MRC leaders. Leaders noted a challenge with food delivery, due to the state’s practice of providing two weeks’ worth of food for each household. In particular, many in their community live multi-generationally with many people per household, MRC leaders noted. Ongoing COVID-19 pandemic response activities were prioritized with the concurrent hurricane response; volunteers were deployed to shelters after the pandemic response activities were staffed, according to MRC leaders.

MRC leaders additionally noted that the Maui unit did not have a unit leader at the time of the wildfires, but volunteers served that role. Units from the other islands deployed volunteers to assist Maui in the response and recovery from the wildfires, according to MRC leaders.

These volunteers served multi-day deployments in Maui; one of the unit leaders said volunteer deployments from her unit occurred from August to October, given that Maui had fewer resources than some of the other islands. MRC volunteers from this unit provided medical support to clinics in Maui. The unit leader said these assignments required careful consideration of deployed volunteers’ skills. MRC volunteers were also used to conduct administrative and coordination tasks and staff family assistance centers during the wildfire response.

|

Hurricane Fiona

Hurricane Fiona made landfall on the southwestern coast of Puerto Rico on September 18, 2022, as a Category 1 hurricane, unleashing 85 miles per hour winds and significant flooding. A unit in Puerto Rico of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Medical Reserve Corps served more than 3,000 people on the island, providing behavioral health support, medical screenings, hygiene kits, and larvicide tablets to control mosquito infestation. Sources: Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (information), Congressional Research Service (information), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (photo). | GAO‑25‑106899 |

Puerto Rico hurricane help. MRC volunteers were part of the response to Hurricane Fiona in 2022 (see sidebar). Volunteers provided medical support, and distributed hygiene kits, personal protective equipment, and COVID-19 tests to residents. The Puerto Rico MRC also had an emotional support team of volunteers that they deployed to provide support to the affected communities.

MRC leaders noted that volunteers also were affected by the hurricane and coping with the disruptions in their own lives. Due to the lack of electricity, MRC leaders said they and volunteers had to rely on previously provided instructions for volunteer meeting places if communications were lost. A Puerto Rico MRC leader said their responses to COVID-19 better prepared them and the volunteers to conduct the hurricane response.

|

Colorado Wildfires

In recent decades, the size and severity of wildfires has increased across much of the United States. For example, the wind-driven Marshall Fire erupted into the most costly wildfire in Colorado history on Dec. 30, 2021. It destroyed over 1,000 homes, resulted in the evacuation of over 37,500 residents and two fatalities as it swept into the Boulder suburbs of Louisville and Superior. The Medical Reserve Corps of Boulder County, a local unit of volunteers, part of the national network of volunteers within the Health and Human Services’ Medical Reserve Corps, deployed volunteers during the Marshall and other recent fires that occurred during the COVID-19 Omicron surge. Sources: GAO‑23‑105517 (information), Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission (information), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (information and photo). | GAO‑25‑106899 |

Colorado wildfire help. MRC units deployed volunteers to respond to wildfires in Colorado during the concurrent COVID-19 Omicron surge in 2021. (See sidebar.) Volunteers distributed COVID-19 tests and provided medical assessments and other support to displaced residents in shelters. MRC leaders said that because MRC units were already working together to respond to the pandemic, they were able to pivot to fire response activities because the unit had an established structure for response activities that volunteers knew.

Volunteers involved in the wildfire response said the activities occurred with short notice and involved a lot of communication between the volunteers and unit leader. MRC leaders said that volunteers were also deployed to cold weather shelters to respond to winter storms during this time period. Deployed MRC volunteer activities included medical assessments, and shelter assistance.

|

Vermont Floods

In July 2023, catastrophic flash flooding and river flooding occurred across much of Vermont. Between three and nine inches of rain fell within 48 hours causing extensive flooding to communities, washouts of numerous roads and bridges, and even the occurrence of land and mudslides, which resulted in significant property losses. A Vermont unit of the Health and Human Services’ Medical Reserve Corps deployed volunteers to various resource centers, alongside health professionals, to help distribute information and water testing kits as well as connect community members to resources, according to a Vermont state official Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (information), Vermont Medical Reserve Corps State Coordinator (information); Beate Ankjaer-Jensen, Rutland-Addison Medical Reserve Corps (photo). | GAO‑25‑106899 |

Vermont flooding help. MRC units deployed volunteers to respond during flooding in the state in 2023. (See sidebar.) Volunteers were deployed to shelters and multi-agency resource centers to hand out water testing kits, water, and information on mold. Volunteers helped partners with the response activities, such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the American Red Cross, according to MRC leaders. Unit leaders and volunteers said some of affected towns were in mountainous areas that were inaccessible, but volunteers assisted if they could travel to the affected areas. Leaders said the pandemic had highlighted how volunteers could be shared among MRC units for response.

MRC Leaders from Selected States Reported Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

Although MRC leaders in our seven selected states reported the use of MRC volunteers as essential for the response to emergencies, they also described challenges they experienced managing their units, as well as mitigation strategies to address those challenges. (See Table 1.)

Table 1: Examples of Challenges Managing Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) Units and Mitigation Strategies, as Reported by MRC Leaders from Selected States

|

Type of Challenge |

Examples of Challenges Managing MRC Units |

Examples of Local Unit and State Mitigation Strategies to Address Challenges |

|

Volunteer participation |

Fulfillment for certain volunteer requests to respond to Hurricane Douglas in 2020 when volunteers were already deployed to COVID-19 pandemic response activities. Limited volunteer participation due to fears and safety concerns about COVID-19 and high-risk populations, including when older adults were a large portion of volunteers. |

COVID-19 education for volunteers and other residents. Adjustment of volunteer assignments based on risk of COVID-19 exposure. |

|

Application process |

Cumbersome process of volunteer applications, using the available state-based volunteer registration system—the Emergency System for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals (ESAR-VHP). Burdensome process of verifying volunteer applications in states that did not have professional licensure verification capability integrated in their ESAR-VHP. |

Assistance from MRC state coordinator or other health department staff with processing of volunteer applications. |

|

Communication |

Electricity loss created by emergency limited methods of communication. |

Use of planning different communication methods, such as communicating in person at designated volunteer meeting locations, rather than relying on phones and electronic communication. |

|

Volunteer emotional support |

High levels of stress among volunteers assisting citizens experiencing trauma. Concurrent pandemic and natural disaster added to volunteer burnout. |

Safety assessments of MRC unit or development of supports for volunteers that experience trauma. |

Sources: GAO interviews with Medical Reserve Corps leaders. | GAO‑25‑106899

Note: In response to the application processing challenges, ASPR officials said the MRC network requested assistance with the influx of volunteers they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and ASPR provided staff assistance with processing volunteer applications on an ad hoc basis.

Most Selected States Focused on Volunteer Retention after Reduction in Volunteers, following the COVID-19 Pandemic Response

MRC leaders from the seven selected states attributed their capacity to respond to public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, to the increase in volunteers they experienced during those crises. MRC leaders from all seven selected states said they experienced a substantial increase in MRC volunteers since the onset of the pandemic; in some cases, MRC units doubled the number of volunteers or more. Two MRC leaders said the pandemic response activities served as recruitment activities.

Among the 31 MRC volunteers we interviewed from six of the seven selected states, most said they joined between 2020 and 2021. A few noted the pandemic motivated them to join and a couple volunteers said their MRC response activities also served as promotion of their unit to the community.

MRC leaders from all but one of the seven selected states said their MRC units had a reduction in MRC volunteers once pandemic response activities slowed down or stopped between 2022 and 2023. For example,

· an MRC leader in Vermont said the unit increased from 35 to about 85 volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic but then reduced to 45 volunteers.

· a Colorado leader said 900 volunteers joined their unit when the pandemic began and then reduced to about 280 volunteers.

· a unit leader in Illinois said the number of volunteers increased from 200 to about 2,000 during the pandemic but had about 220 volunteers when we spoke to them.

MRC leaders and volunteers reported various reasons for the decreases, including the following:

· reinstatement of volunteer requirements, such as certain trainings that had been waived during the pandemic. MRC leaders from one of the selected states said certain training was required for a volunteer to fully register with an MRC unit and start participating in MRC activities. Specifically, MRC leaders said volunteers were required to complete Federal Emergency Management Agency training, Incident Command System training levels 100 and 700. During the pandemic, the requirement was waived and later reinstated once the units were not consumed with COVID-19 response activities.

· volunteer burnout from participating in MRC activities for long hours, sometimes for weeks or months at a time.

· conflicting work responsibilities with deployment requests. Among the MRC units we spoke with, volunteers that worked full time may have less availability—particularly for deployments during the day—than they did during the pandemic response.

· lack of interest in volunteering unless there was another emergency similar to the pandemic.

MRC unit leaders used volunteer trainings to both fill in the training gaps that occurred due to the pandemic, as well as to keep their volunteers engaged. Nevertheless, both MRC leaders and volunteers said it was a challenge to keep volunteers engaged when there were no emergencies. ASPR officials said they heard about the challenges in volunteer engagement and provided opportunities for the MRC network leaders to discuss these challenges. For example, an MRC network wide webinar ASPR held in July 2023 covered volunteer engagement. A volunteer said that there was often more interest in participating than there were opportunities for training and other activities. Unit leaders from five of the selected states also told us they were conducting recruitment activities and/or held non-emergency activities to engage with volunteers. (See fig. 5.)

While MRC units reported focusing on volunteer retention or recruitment, they also noted that their capacity for retention activities varied. For state coordinators and unit leaders we interviewed, some noted that the MRC was only a portion of their emergency preparedness and response responsibilities. We spoke with two unit leaders that led their MRC units full time and they described having the capacity to communicate and hold volunteer activities frequently, but one noted that they were uncommon among other units in their state. Two leaders said they were limited in the time they could devote to MRC activities but managed the units the best they could.

ASPR Provided Funding and Technical Assistance to the MRC Network

ASPR Provided Increased Funding Opportunities for Use by MRC Network in 2020 through 2023

ASPR’s Office of the MRC provided two types of competitive funding opportunities for the MRC network in the period of our review: 1) awards it made directly to the MRC network and 2) awards it provided for indirectly as subawards under cooperative agreements. These funding opportunities were provided to help build community capabilities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, consistent with ASPR’s responsibilities in the National Response Framework. Specifically, the opportunities aimed to support the growth of the network, including creating or expanding MRC units, and serving at-risk communities and areas.

1. Direct ASPR competitive funding: In 2023 ASPR directly provided a competitive funding opportunity for the MRC network: its MRC-State, Territory and Tribal Nations, Representative Organizations for Next Generations awards, which supported jurisdictional MRC programs. Thirty-three states and jurisdictions received these awards that ranged from $376,000 to $2.5 million, supported by $50 million of the $100 million in funding ASPR received from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.[24] ASPR made these awards available for competitive application for all MRC entities, such as jurisdictional government agencies. All seven of our selected states received one of these awards.

2. Sub-awards through cooperative agreements between ASPR and the National Association of County and City Health Officials. Under a cooperative agreement with the National Association of County and City Health Officials, ASPR provides annual funding opportunities—known as the Operational Readiness Awards—which awards MRC units $5,000 or $10,000, based on unit application.

Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, ASPR provided for the National Association of County and City Health Officials to make significantly larger awards to MRC units and state coordinators: the Response, Innovate, Sustain, and Equip Awards. This funding opportunity awarded $25,000, $50,000, or $75,000, depending on the tier the unit applied for. These awards were made also from the $100 million the agency received from American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, according to ASPR officials.

MRC leaders from most selected states said these awards allowed units to hire staff, provide needed training opportunities to volunteers, or provide supplies for local response efforts. For example, one MRC leader said these awards were essential in providing CPR training that their unit would not have been able to provide otherwise. MRC leaders from three selected states said these awards allowed them to fund MRC positions.

While funds were beneficial, MRC leaders from our selected states noted some challenges with ASPR’s funding mechanisms. For example:

· Leaders from two of the seven selected states noted that the large one-time COVID-19 pandemic-related funding awards received since 2020 may not support new hires going forward once the funding is used. A leader from one state said they were exploring other funding options.[25]

· Applying for MRC-specific grants did not always align with MRC leaders’ capabilities. For example, leaders from three states said their jurisdiction’s grant application process did not align with the deadlines for the MRC grants, preventing them from applying for them.

· MRC leaders from a few selected states said they were administratively burdened managing award deliverables or prevented from applying for the MRC-directed funding and one noted that the MRC was only a portion of their responsibilities.

· MRC leaders from a few selected states said they were challenged using the funds only for certain needs. For example, leaders said they were limited in their ability to use the funds to provide food and refreshments at volunteer events; a couple leaders described paying out-of-pocket. ASPR funding opportunities allowed recipients to purchase food for events held for 8 hours or longer that are related to the award project activity, according to ASPR officials.

ASPR Provided Technical Assistance to the MRC Network

ASPR provided various types of technical assistance to the MRC network during our review period. The assistance varied according to the MRC network’s and individual units’ needs at the time, according to officials. Specifically, through ASPR’s Office of the MRC and that office’s regional liaisons, ASPR provided technical assistance to individual units and to the MRC network as a whole, consistent with the National Response Framework.

Unit-specific aid through MRC regional liaisons. ASPR’s Office of the MRC appointed regional liaisons to each MRC unit in its network, charged to address unit needs and challenges through regional meetings and ad hoc communications. MRC regional liaisons had discretion on the frequency and type of communications they conducted with the MRC unit leaders and state coordinators, according to ASPR officials. For example:

· ASPR MRC leadership encouraged liaisons to hold meetings with MRC state coordinators and unit leaders, according to liaisons; among the eight liaisons we spoke to, there was variation in the frequency and type of communications held.

· Most of the liaisons said they hold ‘office hours’ with their MRC unit leaders, and three of them did so weekly or biweekly; two liaisons said they held meetings individually as needed, one of them noting due to the time difference among her units she could not hold this type of meeting.

· Three liaisons said they hold individual orientations with them in addition to the network wide orientations held by ASPR, and one liaison noted due to many of the unit leaders in their region being new to their role. Two other liaisons said they held additional meetings or support with their unit leaders when states had a vacancy in the state coordinator position.

Network-wide information reporting system. ASPR provided units in its MRC network with access to the ASPR’s reporting system to share information on volunteer participation (e.g., hours served by volunteer category, such as nurse or clinical social worker). Once submitted, the reporting system calculated an economic value of volunteer use in MRC activities, which could be used by state officials when applying for disaster reimbursement from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, according to ASPR officials.

Training. ASPR provided MRC members with a web-based training platform, MRC Train. This platform provided courses and other resources on emergency preparedness, response, and public health for MRC leaders and volunteers.[26]

Network-wide guidance. The Office of the MRC and MRC regional liaisons provided the network with MRC-wide guidance. This included resources such as listservs and guidance, as well as webinars, town halls, and structured orientations, according to ASPR officials. For example, from January 2020 to August 2022, ASPR held 22 ‘well check webinars’ that covered various topics including disaster behavioral health, COVID-19 vaccination planning, and introduction to the ASPR MRC website and reporting system.[27] ASPR also provides orientations for new leaders quarterly, according to officials. Additionally, during the pandemic, ASPR officials used other methods to assist the MRC network, such as sharing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention resources and other COVID-19 information through emails and ASPR’s listserv, according to officials.

MRC leaders from three selected states said they considered it helpful to have a MRC regional liaison to communicate questions and receive guidance. MRC leaders from four states considered ASPR’s information sharing and tools to be useful, such as using the ASPR MRC reporting system.

ASPR Relies on MRC Volunteer Information to Maintain Situational Awareness of Network Capabilities, but Data Are Unreliable

ASPR Relies on MRC Network’s Volunteer Counts, Assessments, and Informal Communication to Maintain Situational Awareness of Its Capabilities

There are three key sources ASPR uses to maintain situational awareness of the MRC network’s capabilities: (1) data on volunteer counts and activities reported by MRC units to ASPR; (2) technical assistance assessments conducted by MRC regional liaisons for MRC units, and (3) other informal and ad-hoc communication between MRC regional liaisons and state coordinators and unit leaders.

Data on volunteer counts and activities. ASPR relies on the volunteer counts and unit activity data reported by unit leaders via its reporting system to maintain situational awareness of the breadth and scope of the MRC network’s capabilities to respond to emergencies. By knowing the number of volunteers and volunteer types (e.g. physician, nurse, nonmedical), as well as the types of preparedness and emergency response activities the volunteers have participated in (e.g., mass immunization campaigns), ASPR could maintain situational awareness and would be able to inform other federal and state partners about the MRC network’s capabilities to augment a response to public health and other emergencies, according to ASPR documentation.

MRC unit leaders are required to submit their units’ volunteer counts and activity data using the reporting system at least every 90 days, to remain active units within the MRC network, according to ASPR documentation.[28] ASPR relies on the MRC regional liaisons to generate and review reports from these data submissions that ASPR’s Office of the MRC can use to know the real-time breadth and scope of the network. According to ASPR documentation.

Information from technical assistance assessments. ASPR also relies on its MRC regional liaisons to conduct annual technical assistance assessments of MRC units’ development and technical assistance needs to maintain situational awareness for emergency preparedness and response capabilities.[29] Specifically, ASPR requires MRC regional liaisons, in collaboration with units, to annually assess all MRC units in their regions to review their key strengths. This includes assessing the units’ use of volunteers in emergency response activities, as well as their resource needs, such as volunteer recruitment development or emergency response training.

During these assessments, the MRC regional liaisons also have an opportunity to confirm the units’ volunteer counts to help improve the data they have from ASPR’s reporting system mentioned above.

|

ASPR Town Halls to Collect Information ASPR held town halls with the MRC network in 2023 and 2024, to help further disseminate information and obtain feedback, according to officials. ASPR officials said they plan to hold these twice a year going forward. ASPR conducts outreach to the MRC network in advance of these meetings to solicit questions and feedback from MRC leaders that cannot attend, according ASPR documentation and officials. ASPR can leverage these town halls and other informal communications to respond to certain challenges and feedback, according to officials. For example, ASPR received feedback from the MRC network that ASPR should support a national media campaign to raise awareness of the MRC, according to officials. ASPR did not have funding for such a campaign, so instead it utilized existing social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, X, and LinkedIn, to promote MRC efforts. Sources: Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (information) | GAO‑25‑106899 |

Ad-hoc informal communications. ASPR supplements the information on unit activity and technical assessments with ad-hoc information from the MRC network. For example, through meetings that MRC regional liaisons have held with MRC leaders, and network-wide meetings like town halls, it has learned about challenges experienced by MRC units, as mentioned above, such as the MRC reporting system some units found burdensome, and training opportunities and resources some units reported as inadequate, according to officials. (See sidebar.)

Collectively, this information could help ASPR maintain the situational awareness of the MRC support capabilities. In the broader picture, the information gathered from data on volunteer counts and activities, and other informal information could help ASPR fulfill its responsibilities to lead the federal public health and medical response to emergencies as charged in the National Response Framework.[30]

Unreliable Data Limits ASPR’s Ability to Maintain Situational Awareness of the MRC Network

We found that unreliable data limited ASPR’s ability to maintain situational awareness of the efficacy and availability of its MRC network. ASPR lacks information on whether or to what extent the MRC unit data are updated every 90 days as required and does not utilize an effective mechanism to ensure the technical assistance assessments are being completed annually as required.

ASPR MRC Unit Data Are Unreliable

We found that ASPR does not have reliable data to ensure that MRC data (volunteer counts and activities) are being updated every 90 days in the ASPR reporting system as required. Specifically, we found:

· blank time stamp data for volunteer counts. As of July 2024, more than 70 percent (540 of 748) of all MRC units’ volunteer counts nationwide lacked a system time stamp pertaining to when their volunteer counts were last updated. ASPR officials could not determine whether the blank time stamp data meant the units’ volunteer counts had not changed during the reporting period, or that they had not made the required updates.

· volunteer counts unchanged across multiple years. In our review of ASPR’s MRC unit data from 2020 through 2023, we found that 41 percent (281 of 678) of all MRC units with at least one volunteer each year from 2020 to 2023 had not changed their volunteer counts in these 4 years. ASPR officials could not say this indicated that units were not updating their volunteer counts in the reporting system, or whether the counts did not change, and thus did not have full situational awareness.

Moreover, some of the MRC unit leaders we spoke to confirmed they do not update the volunteer counts for their units as required by ASPR. Specifically, in response to a follow-up questionnaire,

· eleven out of 21 MRC unit leaders we spoke with responded that the volunteer counts listed for their units in the reporting system for 2020 through 2023 were not accurate.[31]

· sixteen of the 21 unit leaders also responded they have not reported their volunteer counts at least quarterly, as required, within the last year.

· leaders from 7 of the 21 units responded they had not been updating their volunteer counts when asked how often their unit was currently updating its total volunteer counts in the system.

While ASPR has communicated on its website and in guidance the requirement that unit leaders update these data every 90 days, MRC unit leaders we interviewed reported not updating their volunteer counts on a quarterly basis for a variety of reasons, including the following:

· being unaware of the expectation to report quarterly (12 out of 21),

· having competing priorities (11 out of 21),

· experiencing turnover among MRC unit leaders (11 out of 21),

· being unaware of the guidance documents, videos, and other materials related to updating total volunteer counts in the reporting system (15 of the 21), and

· having not received training regarding updating total volunteer counts in the reporting system (12 out of 21),

More than half (11 out of 21) of the selected MRC unit leaders that replied to our follow-up questionnaire responded that barriers to updating data in the reporting system include that the system does not have automated processes, such as e-mail reminders or automated prompts to update their volunteer counts as required. MRC unit leaders that we spoke to recommended adding reporting system enhancements, such as automated reminders, to help ensure units update MRC unit data on a regular basis.

In May 2024, ASPR officials said the Office of the MRC had been working on developing a MRC “data hub” prototype to help improve their MRC unit data and information collection, including to help ensure volunteer count and activity reporting, among other things. However, in November 2024, ASPR officials said they had relied on supplemental funds for the hub project and were unsure if they would have the needed resources to finalize the project rollout. More recently in late November 2024, ASPR officials said the Office of the MRC created a workgroup of MRC unit leaders and other state officials to help identify needed technical improvements for the hub.

Developing and implementing a mechanism or mechanisms for ASPR to ensure MRC units are regularly updating volunteer counts and activity data would help ASPR maintain situational awareness of the MRC network’s capabilities to prepare for and respond to emergencies. Moreover, doing so would be consistent with ASPR’s priority to use data to inform decision making, improve operations, and enhance collaboration across ASPR. It would also be consistent with federal standards for internal control that call for management to use quality information to achieve their objectives and operate monitoring activities and evaluate any issues.[32]

Without developing and implementing a mechanism or mechanisms to ensure MRC units are regularly updating MRC unit volunteer and activity data, ASPR risks not having current, complete, or accurate information about state and local activities that they support. As the lead agency, ASPR is responsible for ensuring appropriate planning activities are undertaken and this includes understanding the response capabilities of its partners. Such mechanisms could include additional training and guidance for the MRC regional liaisons and unit leaders, automated reminders to the MRC units to help ensure updates are made to the reporting system, and incentives.

Technical Assistance Assessments Have Resumed, but ASPR Does Not Ensure Their Completion

ASPR requires technical assistance assessments to be conducted annually by its regional liaisons to help inform situational awareness of its MRC network. However, these assessments have not always been completed. According to ASPR officials, these assessments were not always done because of staff turnover and capacity constraints associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, among other challenges. In June 2024, ASPR officials said regional liaisons had resumed their assessments in 2023, but in November 2024, they told us they did not expect all assessments to be completed by the end of the year as they had originally expected.

More recently in December 2024, ASPR officials told us they are using a tracking tool to help ensure assessments are completed for that year. However, the tracking tool we reviewed was often blank, making it unclear as to whether or not the assessments were completed or if they were just not documented. For example, almost half—four of the ten MRC regions—did not have assessment completion dates for 2024. Of these four regions without completion dates, one MRC regional liaison told us he had conducted the assessments in his region though no assessment completion dates were logged for that region in ASPR’s tool. Among the regional liaisons we interviewed, timing for resuming technical assistance assessments once the pandemic subsided, varied. For example, five MRC regional liaisons in our selected states said they resumed conducting the assessments in 2023 and two had not conducted any as of July 2024.

ASPR is responsible for ensuring that appropriate planning and preparedness activities are undertaken ahead of an emergency, including by ensuring it is situationally aware of pending threats and response capabilities, including from MRC volunteers. MRC unit data and information rendered from technical assistance assessments could be used to help determine what additional technical assistance MRC units need to properly respond to an emergency.

These sources also may be used to coordinate across states to locate available volunteers to help respond to a local emergency or disaster in real time. For example, knowing about significant drops in numbers of volunteers due to burnout or COVID-19 response activities dissipating became crucial for state and local planning for volunteer engagement as other emergencies developed. Without accurate and reliable counts, ASPR’s support for the MRC network could become less effective.

ASPR knowing when MRC units have a drop in volunteers, or what technical assistance is needed in real time, is important to be able to better assist and coordinate MRC units to respond in an emergency; such needed information is less accessible when outdated volunteer data and assessments of needs render it unreliable. Without ensuring the completion of regional liaisons’ technical assessments of MRC units, ASPR will lack valuable information—such as what additional assistance and resources units need to effectively respond to an emergency or disaster, or what response capabilities units need to improve—that allows the Office of the MRC to maintain situational awareness of the MRC network.

We have previously found that ASPR has lacked situational awareness in its emergency response role. We have reported that ASPR’s resource needs for an emergency response have not always been aligned with the resources its support agencies could provide, impeding responses.[33] ASPR has a similar responsibility to understand the response capacity of MRC units ahead of emergencies so it can coordinate the deployment of federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial resources—including the availability of volunteers and preparedness and response capacities of the units within the MRC network.

Conclusions

Recent major and concurrent natural disasters—such as wildfires in Maui and Colorado and hurricanes in Puerto Rico—as well as the COVID-19 pandemic and other infectious diseases have highlighted the importance of ensuring states have the capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from public health and other emergencies. This includes having a sufficient number of trained volunteers with the right expertise.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the entire country and required support from all of the nation’s existing systems and structures that help manage public health emergencies, including the MRC network. Volunteers played a key role during the COVID-19 pandemic and other concurrent public health emergencies.

Until ASPR develops and implements a mechanism or mechanisms to ensure MRC units regularly update their volunteer and activity data, it risks having incomplete situational awareness as the coordinator for public health and medical emergency preparedness and response. Such mechanisms could include additional training and guidance for the MRC regional liaisons and unit leaders, automated reminders to help ensure updates are made to the reporting system, and incentives.

Similarly, until ASPR ensures the completion of its regional liaisons’ assessments of MRC units, it will lack valuable information on unit resource needs to effectively respond to an emergency or disaster and what response capabilities units need to improve.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to ASPR:

The Assistant Secretary for Strategic Preparedness and Response should develop and implement a mechanism or mechanisms to ensure MRC units regularly update volunteer counts and activity data as required. This could include additional training and guidance for the MRC regional liaisons and unit leaders, automated reminders to help ensure updates are made to the reporting system, and incentives. (Recommendation 1)

The Assistant Secretary for Strategic Preparedness and Response should ensure that its MRC regional liaisons complete technical assistance assessments of the MRC network as required. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In written comments (reproduced in full in Appendix I) ASPR, within HHS, concurred with both of our recommendations. It also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Regarding our first recommendation to develop and implement a mechanism or mechanisms to ensure MRC units regularly update volunteer counts and activity data as required, HHS noted that the MRC program has a new reporting option, supported by training, to communicate and confirm volunteer data, as of February 2025. HHS has also suggested that we close this recommendation. While this new reporting option is a positive step, we would need documentation to evaluate their efforts in order to close the recommendation.

Regarding our second recommendation to ensure that its MRC regional liaisons complete technical assistance assessments of the MRC network as required, ASPR said it is exploring ways to implement this recommendation.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, as well as other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at DeniganmacauleyM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Mary Denigan-Macauley

Director, Health Care

GAO Contact

Mary Denigan-Macauley, DeniganMacauleyM@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the contact named above, Kelly DeMots (Assistant Director), Jessica L. Preston (Analyst-in-Charge), Ivy Benjenk, Kaitlyn Brown, Patricia Palao-DaCosta, Sarah Prokop, and Marie Suding made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Jennie Apter, David Jones, Diona Martin, Laurie Pachter, Amber Sinclair, and Jennifer Whitworth.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Pub. L. No. 109-417, § 303, 120 Stat. 2831, 2856 (2006) (codified, as amended, at 42 U.S.C. § 300hh-15).

[2]See GAO, Public Health Preparedness: Critical Need to Address Deficiencies in HHS’s Leadership and Coordination of Emergencies, GAO‑23‑106829 (Washington, D.C.: May 11, 2023); and Public Health Preparedness: Mpox Response Highlights Need for HHS to Address Recurring Challenges, GAO‑24‑106276 (Washington, D.C.: April 18, 2024).

[3]In 2020, we found that ASPR provided resources and guidance to the programs in the national MRC network. See GAO, Public Health Preparedness: Information on the Use of Medical Reserve Corps Volunteers during Emergencies, GAO‑20‑630, (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 14, 2020).

[4]The National Response Framework establishes an all-hazards response structure to coordinate federal resources during emergencies and disasters. The framework divides the federal response into 15 emergency support functional areas that are most frequently needed during a national response. See Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework, Fourth Edition (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 28, 2019).

[5]See GAO, COVID-19: Pandemic Lessons Highlight Need for Public Health Situational Awareness Network, GAO‑22‑104600, (Washington, D.C.: June 23, 2022).

For this engagement, we use the term “emergencies” to refer to (1) a national emergency declared by the President under the National Emergencies Act; (2) an emergency or major disaster declared by the President under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act; and (3) a public health emergency declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services under section 319 of the Public Health Service Act.

[6]See GAO, COVID-19: Significant Improvements Are Needed for Overseeing Relief Funds and Leading Responses to Public Health Emergencies, GAO‑22‑105291, (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 27, 2022).

[7]GAO‑22‑105291. We designate federal programs and operations as “high risk” due to their vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or because they need transformation. We consider qualitative factors, such as whether the risk involves public health or safety.

[8]Pub. L. No. 116-22, § 208(b), 133 Stat. 905, 929.

[9]See GAO‑20‑630.

[10]For our work, we considered an MRC unit to be active that reported volunteer counts during our review period.

[11]With MRC unit data and U.S. Census data, we calculated and defined the categories to be that states with fewer than 1,400 citizens per one MRC volunteer are considered to have a large MRC presence; states with between 1,400 and 4,000 citizens per one volunteer were considered medium; states with more than 4,000 citizens per one volunteer were considered small.

[12]The Maryland state coordinator provided written responses to our questions in lieu of an interview.

Puerto Rico has one MRC unit that covers the entire island. We spoke with two of the Puerto Rico MRC regional coordinators.

[13]We were not able to interview Puerto Rico MRC volunteers.

[14]We spoke to the seven liaisons that represented the seven selected states. In addition, we spoke with an additional liaison who had been in the role before the onset of the pandemic since only one of the seven had that experience.

[15]Within the National Response Framework, Emergency Support Function #8—Public Health and Medical Services—provides the mechanism for federal assistance to supplement local, state, tribal, territorial, and insular area resources in response to a disaster, emergency, or incident that may lead to a public health, medical, behavioral, or human service emergency, including those that have international implications. See Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework, and Emergency Support Function #8 – Public Health and Medical Services Annex (Washington, D.C.: June 2016).

[16]Of 22 MRC units of the seven selected states in our review, 21 units responded to our follow-up questionnaire to confirm their volunteer counts from 2020 to 2023 and to respond to questions about challenges the units experienced related to updating their volunteer counts.

[17]As noted previously, this work is a continuation of GAO‑20‑630, issued in September 2020, which analyzed data from September, 2019. This current work related to the Medical Reserve Corps had been paused in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic response.

[18]See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G, (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2024).

[19]Within the National Response Framework, emergency support function #8 directs HHS to support the national or regional teams to continually acquire and assess public health and medical information and needs. See Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework, and Emergency Support Function #8.

[20]Medical surge involves volunteers who could provide both clinical and non-clinical support to hospitals and clinics after a public health emergency.

[21]“Stop the Bleed” is a Department of Defense campaign that encourages the general public to become trained and empowered to help reduce deaths from bleeding in emergencies before professional help arrives.

[22]In four of the selected states, MRC units operated independently from the state, according to MRC leaders. For these states, units made volunteer deployment decisions to respond to emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic; in some cases the state may also send out a request for volunteers. Two of the selected states in our review are centralized, meaning the state health department directs MRC units’ emergency response volunteer deployments, according to leaders.

[23]In GAO‑20‑630, we reported that over 80 percent of MRC units deployed volunteers in response to COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

[24]Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 2502, 135 Stat. 4, 43.

[25]As we have found in past work, jurisdictions use various funding to support their preparation and responses to threats such as public health emergencies. See GAO-105891.

[26]ASPR provides registered MRC units with access to the web-based training platform, MRC TRAIN, which is administered by the Public Health Foundation. MRC TRAIN provides units with emergency preparedness, response, and public health courses.

[27]These webinars are housed on the ASPR MRC training website. As of October 2024, ASPR held three webinars since 2022.

[28]The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, Medical Reserve Corps Unit Profile and Activity Reporting System User Guide, (Washington, D.C.: May 9, 2021).

[29]The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, Medical Reserve Corps Technical Assistance Assessment Process Standard Operating Procedure, (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 1, 2020).

[30]Specifically, within the National Response Framework, Emergency Support Function #8—Public Health and Medical Services—provides the mechanism for federal assistance to supplement local, state, tribal, territorial, and insular area resources in response to a disaster, emergency, or incident that may lead to a public health, medical, behavioral, or human service emergency, including those that have international implications. See Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework, and Emergency Support Function #8.

[31]Of 22 MRC units of the seven selected states in our review, 21 units responded to our follow-up questionnaire to confirm their volunteer counts from 2020 to 2023 and to respond to questions about challenges the units experienced related to updating their volunteer counts.

[32]See GAO‑14‑704G.

[33]See GAO, Public Health Preparedness: Critical Need to Address Deficiencies in HHS’s Leadership and Coordination of Emergencies, GAO‑23‑106829 (Washington, D.C.: May 11, 2023) and Disaster Response: HHS Should Address Deficiencies Highlighted by Recent Hurricanes in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, GAO‑19‑592 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 20, 2019).